Abstract

Ignicoccus hospitalis is an anaerobic, autotrophic, hyperthermophilic Archaeum that serves as a host for the symbiotic/parasitic Archaeum Nanoarchaeum equitans. It uses a yet unsolved autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway that starts from acetyl-CoA (CoA), which is reductively carboxylated to pyruvate. Pyruvate is converted to phosphoenol-pyruvate (PEP), from which glucogenesis as well as oxaloacetate formation branch off. Here, we present the complete metabolic cycle by which the primary CO2 acceptor molecule acetyl-CoA is regenerated. Oxaloacetate is reduced to succinyl-CoA by an incomplete reductive citric acid cycle lacking 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase or synthase. Succinyl-CoA is reduced to 4-hydroxybutyrate, which is then activated to the CoA thioester. By using the radical enzyme 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA is dehydrated to crotonyl-CoA. Finally, β-oxidation of crotonyl-CoA leads to two molecules of acetyl-CoA. Thus, the cyclic pathway forms an extra molecule of acetyl-CoA, with pyruvate synthase and PEP carboxylase as the carboxylating enzymes. The proposal is based on in vitro transformation of 4-hydroxybutyrate, detection of all enzyme activities, and in vivo-labeling experiments using [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate, [1,4-13C2], [U-13C4]succinate, or [1-13C]pyruvate as tracers. The pathway is termed the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle. It combines anaerobic metabolic modules to a straightforward and efficient CO2 fixation mechanism.

Keywords: 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, CO2 fixation pathway, acetyl-CoA

Ignicoccus hospitalis KIN4/IT (Desulfurococcales, Crenarchaeota) is a strictly anaerobic, hyperthermophilic Archaeum with an optimal growth temperature of 90°C (1). All Ignicoccus species grow obligate chemolithoautotrophically by using the reduction of elemental sulfur with molecular hydrogen as the sole energy source and CO2 as the sole carbon source. They possess a unique ultrastructure of the cell envelope with an outer membrane resembling that of Gram-negative bacteria (2). Despite the great similarities with the other Ignicoccus spp., I. hospitalis exhibits an important unique feature: Together with Nanoarchaeum equitans, the only representative of the archaeal kingdom Nanoarchaeota so far (3), it forms the only known purely archaeal host-symbiont/parasite system.

The genome of I. hospitalis exhibits only 1,434 putative genes [data available from the DOE Joint Genome Institute (http://img.jgi.doe.gov/cgi-bin/pub/main.cgi)], clearly indicating a high metabolic specialization. The shortest generation time of the organism grown at 90°C under autotrophic conditions (H2, CO2, and elemental sulfur) is 1 h (1, 4). This indicates that the specialized metabolism also is highly streamlined. In preliminary experiments, I. pacificus and I. islandicus lacked the activities of the key enzymes of all known autotrophic pathways (5), suggesting the operation of a new autotrophic pathway.

Enzymatic analyses in vitro, combined with retrobiosynthetic analyses of amino acids formed in vivo with [1-13C]acetate as a precursor, gave insights into the autotrophic pathway of I. hospitalis starting from acetyl-CoA (4). On the basis of these data, pyruvate synthase and phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) carboxylase were postulated as CO2 fixing enzymes, with PEP carboxylase serving as the only enzyme used for oxaloacetate synthesis. In addition, the operation of an incomplete “horseshoe-type” citric acid cycle, in which 2-oxoglutarate oxidation does not take place, was demonstrated. Enzyme and labeling data indicated a conventional gluconeogenesis, but with some enzymes unrelated to those of the classical pathway.

Although the framework of central carbon metabolism was established, the question remained how acetyl-CoA, the primary CO2 acceptor, is regenerated. Genome analysis did not yield an immediate answer to this problem. For instance, there was neither an indication for enzymes that form acetyl phosphate or acetyl-CoA from hexose phosphates nor was an enzyme detected that could regenerate acetyl-CoA from intermediates of the incomplete citric acid cycle, such as malate.

However, the genome of I. hospitalis contains a gene for 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase (Igni_0595), a [4Fe-4S] and FAD-containing enzyme, which eliminates water from 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA by a ketyl radical mechanism yielding crotonyl-CoA (6, 7). This unique enzyme plays a role in a few 4-aminobutyrate fermenting bacteria such as Clostridium aminobutyricum (8) and so far was considered to be restricted to the fermentative metabolism of strict anaerobic bacteria. However, this enzyme recently was found to play a role in autotrophic CO2 fixation in Metallosphaera sedula and some other Crenarchaeota (9). The encoded protein of Igni_0595 shows an amino acid sequence identity of 52% to the 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase of M. sedula (Msed_1321).

Another odd experimental finding warranted explanation: Enzyme studies showed very high activities of enzymes converting oxaloacetate to succinate (4). This finding was surprising because succinate or succinyl-CoA do not serve as general precursors in metabolic networks except for succinyl-CoA acting as precursor of tetrapyrrole biosynthesis via the Shemin pathway (10). However, the anaerobe I. hospitalis (i) requires tetrapyrroles only in very small amounts, and (ii) the gene for δ-aminolevulinic acid synthase of the Shemin pathway appears to be absent in the genome, whereas the genes of the C5 pathway were present.

In this article, we show that succinate serves as a central intermediate in a CO2 fixation cycle where acetyl-CoA is regenerated via the dicarboxylic acids of an incomplete reductive citric acid cycle and 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA. This cycle represents the sixth autotrophic carbon fixation pathway in nature (11) and is termed the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle.

Results

Succinate Conversion to 4-Hydroxybutyrate.

We suspected that I. hospitalis activates succinate and reduces succinyl-CoA to 4-hydroxybutyrate. This intermediate may then be converted into two molecules of acetyl-CoA, with 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase as a key enzyme. Indeed, succinate thiokinase activity could easily be demonstrated in a coupled spectrophotometric assay by using succinyl-CoA/malonyl-CoA reductase from Metallosphaera sedula as coupling enzyme (Table 1). Moreover, cell extracts also catalyzed a rapid reduction of succinyl-CoA to succinate semialdehyde by using reduced methyl viologen (MV) as electron donor; NAD(P)H was inactive (Table 1). The reaction was optimal at pH 7, and the enzyme was sensitive to oxygen. Succinate semialdehyde was readily reduced to 4-hydroxybutyrate with NAD(P)H by an oxygen-insensitive alcohol dehydrogenase (Table 1).

Table 1.

Specific activities of the enzymes of the proposed dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle in I. hospitalis

| Reaction catalyzed (see Fig. 2) | Enzyme | Assay temperature, °C | Specific activity, nmol/min per mg protein* | Putative gene in I. hospitalis |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pyruvate synthase: methyl viologen CO2 exchange | 75 | 115† | Two possible candidates: |

| 85 | 145† | Igni_1075–1078 or Igni_1256–1259 | ||

| 2 | Pyruvate:water dikinase | 85 | 210† | Igni_1113 |

| 3 | Phosphoenolpyruvate carboxylase | 85 | 200† | Igni_341 |

| 4 | Malate dehydrogenase (NADH/NADPH) | 75 | 1,190/745† | Igni_1263 |

| 5 | Fumarate hydratase (class 1) | 75 | 895† | Igni_0678 |

| 6 | Fumarate reductase (methyl viologen) | 75 | 840† | Igni_0276/Igni_0445 |

| 7 | Succinate thiokinase | 60 | 195 | Igni_0085/Igni_0086 |

| 80 | 980 | |||

| 8 | Succinyl-CoA reductase (methyl viologen) | 60 | 94 | Unknown |

| 9 | Succinate semialdehyde reductase (NADH)/(NADPH) | 60 | 1,430/440 | Unknown |

| 80 | 3,130/2,000 | |||

| 10 | 4-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA synthetase (AMP-forming) | 60 | 100 | Igni_0475 |

| 11 | 4-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase | 40 | 100 | Igni_0595 |

| 12 | Crotonyl-CoA hydratase ((S)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA forming) | 40 | 460 | Igni_1058 |

| 13 | (S)-3-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (NADH/NADPH) | 60 | 225/0 | Igni_1058 |

| 14 | Acetoacetyl-CoA β-ketothiolase | 60 | 1,100 | 2 possible candidates Igni_1401, Igni_0377 |

For technical reasons (use of mesophilic coupling enzymes and instability of some substrates), the indicated assay temperatures were used; the growth temperature was 90°C. The values are average values of several determinations; the mean deviations are 5–20%, depending mainly on the batch of cells.

*Note the discrepancy in assay temperature and optimal growth temperature. Despite the lower assay temperature, the measured specific activities are already close to the requisite physiological level, although methyl viologen rather than ferredoxin is used as electron carrier of several oxidoreductase assays.

†From ref. 4.

4-Hydroxybutyrate Conversion to Two Molecules of Acetyl-CoA.

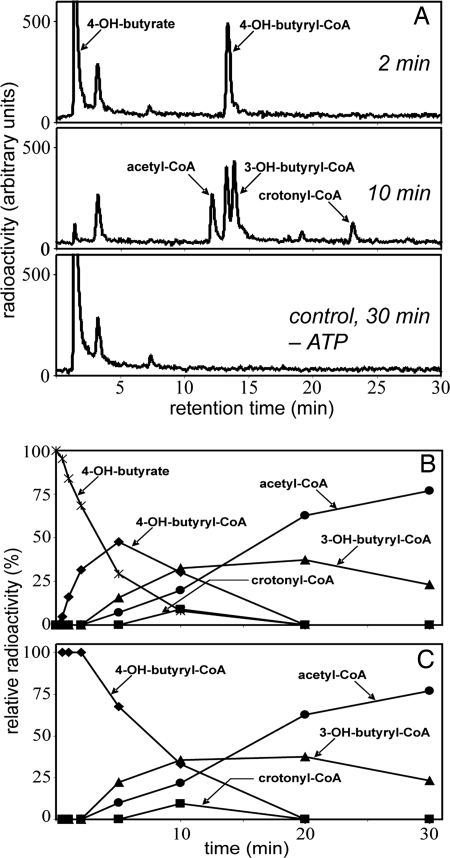

Because 4-hydroxybutyrate was readily formed from succinate but does not play a role as a building block in biosynthesis, enzymes must exist that transform it further. Extracts rapidly converted [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate to [14C]acetyl-CoA, provided that MgATP, CoA, and NAD+ were present (Fig. 1A). HPLC analysis of the reaction course showed that labeled 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA, crotonyl-CoA, and 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA were intermediates (Fig. 1B). A plot of the relative amounts of radioactivity in the individual products versus time showed that the intermediates appeared in the expected chronological order and that acetyl-CoA was the end product (Fig. 1C). The rate of this transformation at 60°C was 115 nmol/min per mg protein. In addition, enzymatic analyses showed activities of 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA synthetase (AMP-forming), 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, crotonyl-CoA hydratase ((S)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA forming), (S)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (NAD+), and acetoacetyl-CoA β-ketothiolase (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Conversion of [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate to [14C]acetyl-CoA at 60°C by cell extracts of I. hospitalis. (A) HPLC separation of labeled substrate and products and 14C detection by flow-through scintillation counting. The figure shows samples taken after 2- and 10-min incubation, as well as a control experiment lacking ATP after 30-min incubation. The radioactive peak at 3.5 min most likely represents γ-butyrolactone, which forms spontaneously from 4-hydroxybutyrate at acidic pH or from 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA at neutral pH. (B) Time course of substrate consumption and product formation. 100% corresponds to the total radioactivity added at the beginning. (C) Percentage of radioactivity present in the individual products, compared with the total radioactivity in all labeled products, versus time. 100% corresponds to the total radioactivity contained in all products at a given time. The strong negative slope for 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA indicates that it is the first intermediate. The strong positive slope for acetyl-CoA indicates that it is the end product. Crotonyl-CoA and 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA behave like intermediates between 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA and acetyl-CoA.

The cells that were studied here grew with a generation time of 2 h, which requires a specific rate of CO2 fixation of 0.4 μmol CO2 fixed per min per mg of protein (4). Because two atoms of carbon are fixed in the proposed pathway (see below), the minimal in vivo-specific activity of enzymes in the cycle is 0.2 μmol/min per mg protein (for cofactor specificity, see Fig. 2). The specific activities of the tested enzymes in vitro, when extrapolated to the growth temperature, met this expectation.

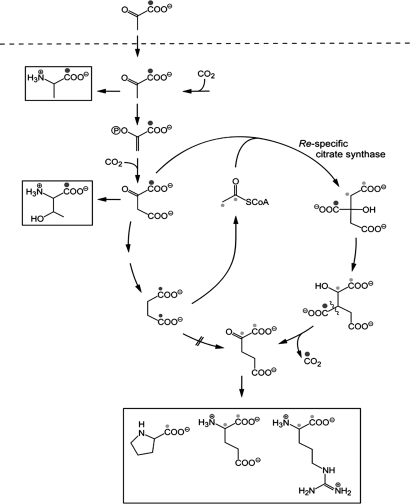

Fig. 2.

Proposed dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle for autotrophic CO2 fixation in I. hospitalis. Enzymes: 1, pyruvate synthase (reduced MV); 2, pyruvate:water dikinase; 3, PEP carboxylase; 4, malate dehydrogenase (NADH); 5, fumarate hydratase; 6, fumarate reductase (reduced MV); 7, succinate thiokinase (ADP forming); 8, succinyl-CoA reductase (reduced MV); 9, succinate semialdehyde reductase (NADPH); 10, 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA synthetase (AMP forming); 11, 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase; 12, crotonyl-CoA hydratase; 13, 3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase (NAD+); 14, acetoacetyl-CoA β-ketothiolase. Label from [1,4-13C2]succinate is indicated by filled circles.

Based on the in vitro enzyme data, we propose a new pathway termed dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle, as shown in Fig. 2. To further elucidate the pathway under in vivo conditions, I. hospitalis was grown in the presence of various isotope-labeled precursors.

In Vivo Incorporation of [1-14C]4-Hydroxybutyrate into Protein-Derived Amino Acids.

4-Hydroxybutyrate is a characteristic molecule that is not encountered in any other biosynthetic pathway, and the transfer of isotope from labeled 4-hydroxybutyrate can therefore be taken as strong evidence for the proposed cycle. Capitalizing on this fact, we grew I. hospitalis under autotrophic conditions for several generations in the presence of trace amounts of [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate (0.5 μM, specific radioactivity 105,000 dpm/nmol) and analyzed the incorporation of 14C into cell material. After 15 h of growth, 30% of the labeled compound was incorporated into cell mass. The total radioactivity in the culture remained virtually constant, indicating that hardly any volatile 14CO2 was formed. The cells were hydrolyzed, the amino acids were separated, and their 14C content was determined [see supporting information (SI) Fig. S1]. Radioactivity coeluted with all amino acid fractions. The specific radioactivity values of the individual amino acids varied by a factor of approximately three, from ≈300 to 1,000 dpm/nmol. This indicates that (i) exogenous 4-hydroxybutyrate did not alter the autotrophic growth mode, (ii) the labeled precursor was incorporated into all amino acids under study, (iii) the estimated specific radioactivity values are consistent with the incorporation of the tracer according to the proposed carbon fixation cycle (see Fig. 2), and (iv) 4-hydroxybutyrate serves as an intermediate in the autotrophic pathway.

In Vivo Incorporation of [1,4-13C2]- and [U-13C4]Succinate into Protein-Derived Amino Acids.

The role of succinate as an intermediate of the proposed pathway was corroborated by similar incorporation experiments by using [1,4-13C2]- or [U-13C4]succinate, respectively. Tert-butyldimethylsilyl (TBDMS) derivatives of amino acids derived from cell protein were analyzed by GC-MS. The 13C enrichments of isotopologues containing one or two 13C atoms (M + 1 or M + 2, respectively) showed that up to 6% of the amino acid carbon skeleton stem from the exogenously supplied 13C-labeled succinate specimens (Table S1). In both experiments, isotopologues with more than two 13C atoms were not observed, and Ile was found to be unlabeled probably because of the presence of unlabeled Ile in the growth medium.

A correlation plot visualizing the ratio between M + 1 and M + 2 isotopologues (mass fragments containing one or two 13C atoms in a given amino acid) (Table S1) shows that the experiments using [1,4-13C2]- or [U-13C4]succinate as precursors cluster into two distinct families with (i) high enrichment values for M + 1 isotopologues in the experiment with the doubly labeled succinate precursor, and (ii) high enrichment values for M + 2 isotopologues in the experiment with totally 13C-labeled succinate (Fig. S2). It can be concluded that typically one 13C atom was transferred from [1,4-13C2]succinate to central intermediates acting as precursors of amino acids. In contrast, a typical number of two 13C atoms was transferred from [U-13C4]succinate. The data support that succinate can be converted into acetyl-CoA with cleavage of the C-2–C-3 bond of a C4 intermediate. In line with our previous results (4), acetyl-CoA then serves as a precursor for the amino acids under study.

In Vivo Incorporation of [1-13C]pyruvate into Protein-Derived Amino Acids.

Cells of I. hospitalis were grown for at least six generations in the presence of 0.5 mM [1-13C]pyruvate. The isotopologue distribution of amino acids obtained from cell hydrolysates was again quantified by GC-MS of the TBDMS derivatives (Table S1). The data show that 25–40% of Ala, Val, Ser, and Asp were derived from the proffered pyruvate, whereas <10% were 13C-labeled in all other amino acids under study. The positional distribution of label in the respective amino acids was determined by quantitative NMR spectroscopy (Table S2). The overall 13C-enrichment values were in good agreement with the values determined by mass spectroscopy. 13C-Label was efficiently transferred from 13C-1 of pyruvate into the biogenetically equivalent C-1 positions of Ala, Ser, Tyr, and Val (25–10% 13C-enrichment) (Table S2). High enrichment values were also found in positions 6/8 and 7 of Tyr, biosynthetically equivalent to positions 3/1 and 2 of the erythrose 4-phosphate precursor. Notably, the corresponding positions in Phe were less 13C-enriched. This apparent discrepancy can be explained by the presence of unlabeled Phe, but not of unlabeled Tyr in the growth medium. Position 1 in Thr was found to be 13C-enriched with ≈7% 13C. This finding is well in line with the known biosynthetic origin of C-1 of Thr from C-1 of Asp, which, in turn, is derived from C-1 of oxaloacetate by carboxylation of [1-13C]PEP (Fig. 3 and Table S2).

Fig. 3.

Scheme illustrating the incorporation of 13C from [1-13C]pyruvate into amino acids of proteins by I. hospitalis cultures growing autotrophically in the presence of 0.4 mM [1-13C]pyruvate. Highly 13C-enriched carbon atoms are marked by large black dots, smaller dots indicate randomization of 13C enrichment caused by the symmetry of succinate (small black dots) and by the subsequent reactions leading to the cleavage into two molecules of acetyl-CoA (small gray dots). Structures with more than one label are mixtures of single labeled isotopologue. As an example, acetyl-CoA marked with two dots is in reality a mixture of the [1-13C1]- and [2-13C1]-isotopologue.

Lower but significant enrichment values (2–3%) were detected in positions 1 and 2 of Glu, Pro, and Arg. After the reaction of the horseshoe-type citrate cycle in I. hospitalis with a re-specific citrate synthase (4), these carbon atoms are biosynthetically equivalent with carbon atoms 1 and 2 of acetyl-CoA, respectively (indicated by small gray dots in Fig. 3). The Ignicoccus genome encodes a homolog of the re-citrate synthase from Clostridium kluyveri (CKL_0973) (12) supporting this notion (Igni_0261). Enrichment values of ≈2% 13C were also found in positions 1–3 of Lys, which stem from acetyl-CoA building blocks (4). In general, label from exogenously supplied [1-13C]pyruvate was transferred into those positions of amino acids, which were biosynthetically equivalent to position 1 of pyruvate or PEP and, at lower efficiency, into those positions equivalent to C-1, as well as C-2 of acetyl-CoA (Fig. 3).

In summary, all data support a biosynthetic scheme where acetyl-CoA is formed from succinate via 4-hydroxybutyrate (Fig. 2). Notably, the specific transfer of label from [1-13C]pyruvate into both carbon positions of the acetyl moiety in acetyl-CoA is perfectly explained. More specifically, label from [1-13C]pyruvate is transferred to either position 1 or 4 of the mentioned C4 intermediates because of the inherent symmetry of the succinate intermediate. Cleavage of [1,4-13C1]acetoacetyl-CoA then results in [1-13C]acetyl-CoA or [2-13C]acetyl-CoA, respectively (Fig. 3).

Discussion

Proposed New Autotrophic CO2 Fixation Cycle.

We propose the following autotrophic pathway termed dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle after its characteristic free intermediates (see Fig. 2). The cycle can be divided into part 1 transforming acetyl-CoA, one CO2 and one bicarbonate to succinyl-CoA via pyruvate, PEP, and oxaloacetate, and part 2 converting succinyl-CoA via 4-hydroxybutyrate into two molecules of acetyl-CoA.

A comparison to the Calvin–Bassham–Benson cycle reveals differences concerning energy consumption, redox carriers, and active CO2 species. The formation of one molecule of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate from three molecules of CO2 follows the equation: 3 CO2 + 6 NAD(P)H + 9 ATP → 1 triose phosphate + 6 NAD(P)+ + 9 ADP + 8 Pi. The formation of acetyl-CoA via the new cycle follows the equation: 1 CO2 + 1 HCO3− + 6 reduced ferredoxin + NAD(P)H + 3 ATP + CoA → 1 acetyl-CoA + 6 oxidized ferredoxin + 1 NAD(P)+ + 2 AMP + 1 ADP + 3 Pi + 1 PPi. This assumes that fumarate reductase, pyruvate synthase, and succinyl-CoA reductase use two reduced ferredoxin each (each transferring one electron). Further assimilation of acetyl-CoA to form triose phosphates follows: Acetyl-CoA + CO2 + 2 reduced ferredoxin + NAD(P)H + 2 ATP → 1 triose phosphate + 2 oxidized ferredoxin + NAD(P)+ + ADP + AMP + 2 Pi + CoA. In total, triose phosphate formation via the proposed new cycle follows the equation: 2 CO2 + 1 HCO3− + 8 reduced ferredoxin + 2 NAD(P)H + 5 ATP → 1 triose phosphate + 8 oxidized ferredoxin + 2 NAD(P)+ + 2 ADP + 3 AMP + 5 Pi + 1 PPi. Assuming that PPi is hydrolyzed, the fixation of three molecules of inorganic carbon costs eight ATP equivalents. Hence, in energetic terms, the new cycle is less energy consuming than the Calvin cycle, notably when one considers the loss of reducing power and ATP by the oxygenase activity of RubisCO.

A comparison to the crenarchaeal 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle (9) also reveals different characteristics. The summary of this cycle is as follows (assuming pyruvate formation from acetyl-CoA via pyruvate synthase): 2 HCO3− + 1 CO2 + 5 NAD(P)H + 2 reduced ferredoxin + 6 ATP → 1 triosephos-phate + 5 NAD(P)+ + 2 oxidized ferredoxin + 3 ADP + 4 Pi + 3 AMP + 2 PPi. The energy requirement is nine ATP equivalents. The Ignicoccus cycle preferentially uses reduced ferredoxin instead of NAD(P)H as electron donor and CO2 rather than bicarbonate as the active inorganic carbon species. The reducing power of reduced ferredoxin is stronger than that of reduced pyridine nucleotides, making a direct energetic comparison questionable. In growing cells, ferredoxin is most likely reduced by a hydrogenase. Under low-hydrogen partial pressure, the reduction of ferredoxin may be forced by energy-driven reverse electron transport from NAD(P)H, allowing an effective reductive carboxylation of acetyl-CoA by pyruvate synthase (13).

The active “CO2” species is CO2 in the Calvin cycle, whereas it is CO2 as a cosubstrate for pyruvate synthase and bicarbonate as a cosubstrate for PEP carboxylase in the proposed cycle. The affinity of the carboxylases for CO2 or bicarbonate may not be as critical as in the case of the Calvin cycle because the organism lives in volcanic areas with high ambient CO2 partial pressure.

Comparison of the Cycle with Other Autotrophic Pathways (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

General scheme representing the strategy used by four different carbon dioxide fixation pathways. These pathways have in common the formation of succinyl-CoA from acetyl-CoA and two inorganic carbons. The vertical arrows point to the carbon dioxide fixation products released from these metabolic cycles. The combination of the metabolic modules 1 and 4 results in the 3-hydroxypropionate/glyoxylate cycle, as studied in Chloroflexus sp. The combination of 1 and 3 yields the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle present in several Crenarchaeota. The combination of 2 and 5 yields the reductive citric acid cycle, which is present in various anaerobes or microaerobes. The combination of 2 and 3 yields the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle.

In four autotrophic CO2 fixation cycles, succinyl-CoA plays a central role. (i) Green nonsulfur bacteria (Chloroflexus aurantiacus and related bacteria) use acetyl-CoA/propionyl-CoA carboxylase(s) as carboxylating enzyme(s) to form succinyl-CoA (route 1), from which acetyl-CoA is regenerated via malyl-CoA cleavage (route 4) and glyoxylate is the carbon fixation product (3-hydroxypropionate/glyoxylate cycle) (Fig. 4) (14–16). (ii) In the Crenarchaeota of the order Sulfolobales and possibly in Cenarchaeum symbiosum and Nitrosopumilus sp., route 1 is used for succinyl-CoA formation, as in Chloroflexus, but acetyl-CoA regeneration proceeds via 4-hydroxybutyrate (route 3) and acetyl-CoA is the product (3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle) (9, 11). (iii) In the strict anaerobic I. hospitalis, as shown here, acetyl-CoA is converted to succinyl-CoA using pyruvate synthase and PEP carboxylase as the carboxylating enzymes (route 2); acetyl-CoA regeneration via 4-hydroxybutyrate is similar to the route in Sulfolobales (route 3) (dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle). The new cycle is composed of elements of anaerobic metabolism, and its first half reminds of the reductive citric acid cycle. (iv) In the reductive citric acid cycle, succinyl-CoA is formed via route 2; however, succinyl-CoA is further reductively carboxylated to 2-oxoglutarate and isocitrate and converted to citrate, which is cleaved into acetyl-CoA and oxaloacetate (17).

In principle, other combinations of the five partial routes indicated in Fig. 4 are conceivable. The individual partial routes differ not only with respect to ATP requirement, but also with respect to oxygen sensitivity of its enzymes, notably of its oxidoreductases, and the use of reduced ferredoxin instead of NAD(P)H. The metal requirement (Fe, Co) also differs. Routes 2 and 5 are typical “anaerobic” pathways that are unlikely to occur in strict aerobes, whereas routes 1, 3, and 4 are (micro)aerobic pathways. Whether combinations others than those discussed exist remains unknown.

Possible Occurrence of the Cycle in Other Archaea.

The set of genes that are characteristic for the 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle are found in the genomes of autotrophic members of the Sulfolobales, “Cenarchaeales,” “Nitrosopumilales,” and Archaeoglobales (9, 11). This set includes the genes for acetyl-CoA carboxylase, methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, and 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase. Autotrophic members of the Desulfurococcales (I. hospitalis) and Thermoproteales (Thermoproteus neutrophilus, Pyrobaculum aerophilum, P. islandicum, and P. caldifontis) contain the gene for 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, but lack those for acetyl-CoA carboxylase and methylmalonyl-CoA mutase. Most of these organisms grow as strict anaerobes by reducing sulfur with hydrogen gas. The gene pattern is in line with the functioning of the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle in these organisms. Also, the previously observed labeling data with T. neutrophilus (18) are consistent with a dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle. Therefore, the autotrophic carbon fixation pathway in the Thermoproteales, for which a reductive citric acid cycle was proposed (18–22), needs to be reinvestigated in view of the proposed cycle.

Evolutionary Aspects.

The new pathway in Ignicoccus uses a set of electron carriers and enzymes that are characteristic for strict anaerobes. It requires various iron-sulfur proteins such as ferredoxin (the putative electron donor of pyruvate synthase and succinyl-CoA reductase), pyruvate synthase, fumarate reductase, and 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, as well as thioesters to facilitate chemical reactions. The use of such oxygen-sensitive enzymes is restricted to an anaerobic lifestyle. The reactions used by the dicarboxylate/4-hydroxybutyrate cycle fit well into a simple primordial carbon fixation scheme in an iron-sulfur world that makes use of energy-rich thioesters, as proposed and advocated by Günter Wächtershäuser (23). So far, this cycle seems to be restricted to a small number of Crenarchaeota. Whether they have developed the cycle from preexisting anaerobic modules needs to be investigated by an extensive phylogenetic analysis of the involved genes. A recent consensual and likely phylogenetic tree of Archaea for which complete genome sequences are available puts the Thermoproteales and Desulforococcales (to which Ignicoccus belongs) near the origin of Archaea (24). In this sense, the new cycle may serve as a model for an ancient autotrophic pathway.

Materials and Methods

Materials.

The materials used are the same as previously published (4, 16).

Bacterial Strains and Culture Conditions.

I. hospitalis strain KIN4/IT was obtained from the culture collection of the Lehrstuhl für Mikrobiologie, University of Regensburg. It was grown in [1/2] SME (synthetic sea water) medium without organic substrates using elemental sulfur as electron acceptor under a gas phase of H2/CO2 (80%/20%, vol/vol) at 90°C and pH 5.5 (1) as described previously (25).

Incorporation of [1-14C]4-Hydroxybutyrate.

The incorporation of 4-hydroxy[1-14C]butyrate into I. hospitalis cells was investigated by cultivating I. hospitalis cells in the presence of 0.5 μM [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate [6 μCi of labeled compound (48 μCi/μmol; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) added to 250 ml medium] in 1-liter serum bottles under a gas phase of H2/CO2 (80%/20%, vol/vol, 160 kPa) at 100 rpm. Samples (2 ml) were retrieved directly after inoculation (≈2 × 105 cells per milliliter) and after 15-h cultivation (≈1 × 107 cells/ml). The cell concentration was determined by cell counting using a Neubauer counting chamber. The samples were passed through a 0.2-μm nitrocellulose filter (Schleicher & Schuell) and washed two times with 5 ml of unlabeled medium. The radioactivity of the filter as well as the filtrate was determined by liquid scintillation counting by using 3 ml of Rotiszint eco plus scintillation mixture (Roth) with external standardization.

Separation of the Labeled Amino Acids.

Briefly, ≈3 mg of I. hospitalis cells (fresh cell mass) grown in the presence of [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate was hydrolyzed under vacuum for 24 h at 110°C in 0.6 ml of 6 M HCl containing 0.2% (vol/vol) phenol. The hydrolysate was centrifuged (13,000 × g), and the supernatant was dried over KOH in a desiccator. The pellet was dissolved in 0.3 ml Na+-citrate buffer (pH 2.2). Samples (0.1 ml) were analyzed by using a Biotronik BT 6000 E amino acid analyzer with Ninhydrin reagent. The column (6 × 250 mm) was packed with resin DC6A (Dionex). The concentrations were calculated by comparison of the peak area with separation of amino acid standards (20 nmol per amino acid). A parallel run was performed, in which Ninhydrin detection was omitted and fractions of 2 ml were collected. Radioactivity in 1 ml of these fractions was determined by liquid scintillation counting.

Syntheses.

Acetoacetyl-CoA was synthesized from diketene by the method of Simon and Shemin (26). Succinyl-CoA, acetyl-CoA, and crotonyl-CoA were synthesized from their anhydrides according to ref. 26. (R)− and (S)-3-hydroxybutyryl-CoA were synthesized by the mixed anhydride method (27).

Cell Extracts and Enzyme Measurements.

Cell extracts were prepared anaerobically according to Jahn et al. (4). The protein concentration in cell extracts was determined by the Bradford method (28) using BSA as a standard.

Enzyme measurements for Succinate thiokinase, Succinyl-CoA reductase, Succinate semialdehyde reductase, 4-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA synthetase, 4-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase, Crotonyl-CoA hydratase, (S)-3-Hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydrogenase, and Acetoacetyl-CoA β-ketothiolase were performed as described previously (9), with slight modifications (see SI Text).

Conversion of [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate by I. hospitalis cell extracts was studied at 60°C in a 1-ml reaction mixture containing 100 mM Mops/KOH (pH 7.2), 3 mM MgCl2, 3 mM ATP, 2 mM CoA, 5 mM DTT, 2 mM NAD+, and 1 mM 4-hydroxybutyrate (2.3 μCi/ml). The reaction was started by the addition of the cell extract (1.45 mg of protein). Control experiments were conducted without ATP. At different time points, the reaction was stopped by transferring 50 μl of the reaction mixture to 5 μl of 1 M HCl in 200 μl of methanol.

HPLC Analysis.

The products of the conversion of [1-14C]4-hydroxybutyrate in cell extracts of I. hospitalis were analyzed by using a RP-C18 column reversed-phase HPLC as described previously (29).

Labeling of Growing Cells with [1-13C]Pyruvate and the Study of Distribution of 13C in Individual Building Blocks.

I. hospitalis was cultivated as described above under autotrophic conditions in a 50-liter enamel protected fermentor (stirring 250 rpm) in the presence of 0.4 mM [1-13C]pyruvate (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories). At a cell concentration of 106 cells/ml, gas stripping was started [N2/H2/CO2 (65%/15%/20%, vol/vol/vol) 6 l/min]. Cells were harvested in the late exponential growth phase (cell concentration ≈8 × 106 cells/ml). Fractionation of the cell material was performed as described in ref. 4, amino acids were isolated by chromatographic procedures as described in ref. 30, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra were recorded as described in ref. 4.

Mass Spectrometry.

TBDMS derivatives of amino acids were prepared as described earlier. GC/MS analysis and calculation of isotopologue patterns were performed as described previously (31).

Database Search.

Query sequences were obtained from the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database. The BLAST searches were performed via the NCBI Blast server (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST) (32, 33).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments.

We thank Michael Thomm for highly valuable discussions and support, Nasser Gad'on and Christa Ebenau-Jehle for growing cells and maintaining the laboratory, and Christine Schwarz and Fritz Wendling for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (Förderkennzeichen Grants HU/701–3 and FU 118/15–3) and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/cgi/content/full/0801043105/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Paper W, et al. Ignicoccus hospitalis sp. nov., the host of “Nanoarchaeum equitans.”. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2007;57:803–808. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64721-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rachel R, Wyschkony I, Riehl S, Huber H. The ultrastructure of Ignicoccus: Evidence for a novel outer membrane and for intracellular vesicle budding in an archaeon. Archaea. 2002;1:9–18. doi: 10.1155/2002/307480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huber H, et al. A new phylum of Archaea represented by a nanosized hyperthermophilic symbiont. Nature. 2002;417:63–67. doi: 10.1038/417063a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jahn U, Huber H, Eisenreich W, Hügler M, Fuchs G. Insights into the autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway of the archaeon Ignicoccus hospitalis: Comprehensive analysis of the central carbon metabolism. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4108–4119. doi: 10.1128/JB.00047-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hügler M, Huber H, Stetter KO, Fuchs G. Autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways in archaea (Crenarchaeota) Arch Microbiol. 2003;179:160–173. doi: 10.1007/s00203-002-0512-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martins BM, Dobbek H, Cinkaya I, Buckel W, Messerschmidt A. Crystal structure of 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA dehydratase: radical catalysis involving a [4Fe-4S] cluster and flavin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15645–15649. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403952101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buckel W, Golding BT. Radical enzymes in anaerobes. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2006;60:27–49. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.60.080805.142216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gerhardt A, Cinkaya I, Linder D, Huisman G, Buckel W. Fermentation of 4-aminobutyrate by Clostridium aminobutyricum: Cloning of two genes involved in the formation and dehydration of 4-hydroxybutyryl-CoA. Arch Microbiol. 2000;174:189–199. doi: 10.1007/s002030000195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berg IA, Kockelkorn D, Buckel W, Fuchs G. A 3-hydroxypropionate/4-hydroxybutyrate autotrophic carbon dioxide assimilation pathway in Archaea. Science. 2007;318:1782–1786. doi: 10.1126/science.1149976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shemin D. An illustration of the use of isotopes: The biosynthesis of porphyrins. BioEssays. 1989;10:30–35. doi: 10.1002/bies.950100108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thauer RK. Microbiology. A fifth pathway of carbon fixation. Science. 2007;318:1732–1733. doi: 10.1126/science.1152209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li F, Hagemeier CH, Seedorf H, Gottschalk G, Thauer RK. Re-citrate synthase from Clostridium kluyveri is phylogenetically related to homocitrate synthase and isopropylmalate synthase rather than to Si-citrate synthase. J Bacteriol. 2007;189:4299–4304. doi: 10.1128/JB.00198-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hedderich R. Energy-converting [NiFe] hydrogenases from archaea and extremophiles: Ancestors of complex I. J Bionenerg Biomembr. 2004;36:65–75. doi: 10.1023/b:jobb.0000019599.43969.33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strauss G, Fuchs G. Enzymes of a novel autotrophic CO2 fixation pathway in the phototrophic bacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus, the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle. Eur J Biochem. 1993;215:633–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Herter S, et al. Autotrophic CO2 fixation by Chloroflexus aurantiacus: study of glyoxylate formation and assimilation via the 3-hydroxypropionate cycle. J Bacteriol. 2001;183:4305–4316. doi: 10.1128/JB.183.14.4305-4316.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Alber B, et al. Malonyl-coenzyme A reductase in the modified 3-hydroxypropionate cycle for autotrophic carbon fixation in archaeal Metallosphaera and Sulfolobus spp. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:8551–8559. doi: 10.1128/JB.00987-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Buchanan BB, Arnon DI. A reverse KREBS cycle in photosynthesis: Consensus at last. Photosynth Res. 1990;24:47–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Strauss G, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Fuchs G. 13C-NMR study of autotrophic CO2 fixation pathways in the sulfur-reducing Archaebacterium Thermoproteus neutrophilus and in the phototrophic Eubacterium Chloroflexus aurantiacus. Eur J Biochem. 1992;205:853–866. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16850.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Beh M, Strauss G, Huber R, Stetter KO, Fuchs G. Enzymes of the reductive citric acid cycle in the autotrophic eubacterium Aquifex pyrophilus and in the archaebacterium Thermoproteus neutrophilus. Arch Microbiol. 1993;160:306–311. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schäfer S, Götz M, Eisenreich W, Bacher A, Fuchs G. 13C-NMR study of autotrophic CO2 fixation in Thermoproteus neutrophilus. Eur J Biochem. 1989;184:151–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schäfer S, Paalme T, Vilu R, Fuchs G. 13C-NMR study of acetate assimilation in Thermoproteus neutrophilus. Eur J Biochem. 1989;186:695–700. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1989.tb15262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hu Y, Holden JF. Citric acid cycle in the hyperthermophilic archaeon Pyrobaculum islandicum grown autotrophically, heterotrophically, and mixotrophically with acetate. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4350–4355. doi: 10.1128/JB.00138-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wächtershäuser G. From volcanic origins of chemoautotrophic life to Bacteria, Archaea and Eukarya. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 2006;361:1787–1808. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brochier C, Forterre P, Gribaldo S. An emerging phylogenetic core of Archaea: Phylogenies of transcription and translation machineries converge following addition of new genome sequences. BMC Evol Biol. 2005;5:36. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-5-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huber H, et al. Ignicoccus gen. nov., a novel genus of hyperthermophilic, chemolithoautotrophic Archaea, represented by two new species, Ignicoccus islandicus sp nov and Ignicoccus pacificus sp nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:2093–2100. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-6-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon EJ, Shemin D. The preparation of S-succinyl-coenzyme A. J Am Chem Soc. 1953;75:2520. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stadtman ER. Preparation and assay of acyl coenzyme A and other thiol esters; use of hydroxylamine. Meth Enzymol. 1957;3:931–941. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bradford MM. A rapid and sensitive method for the quantitation of microgram quantities of protein utilizing the principle of protein-dye binding. Anal Biochem. 1976;72:248–254. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(76)90527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Erb TJ, et al. Synthesis of C5-dicarboxylic acids from C2-units involving crotonyl-CoA carboxylase/reductase: The ethylmalonyl-CoA pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:10631–10636. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702791104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Eisenreich W, Schwarzkopf B, Bacher A. Biosynthesis of nucleotides, flavins, and deazaflavins in Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:9622–9631. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Römisch-Margl W, et al. 13CO2 as a universal metabolic tracer in isotopologue perturbation experiments. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:2273–2289. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2007.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Benson DA, Karsch-Mizrachi I, Lipman DJ, Ostell J, Wheeler DL. GenBank. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:D16–D20. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkj157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Altschul SF, Gish W, Miller W, Myers EW, Lipman DJ. Basic local alignment search tool. J Mol Biol. 1990;215:403–410. doi: 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.