Abstract

Up to 12 000 patients with gynaecological, urological and rectal cancer undergo radical pelvic radiotherapy annually in the UK. More than 70% develop acute inflammatory changes causing gastrointestinal symptoms during treatment because healthy bowel tissue is encompassed in the radiation field. In total, 50% go on to develop chronic bowel symptoms, which affect quality of life due to permanent changes in the small and large intestine. Nutritional intervention may influence acute and chronic bowel symptoms but the validity of the advice given to patients is not clear. To assess the incidence and significance of malnutrition and to examine the efficacy of therapeutic nutritional interventions used to manage gastrointestinal side effects in patients undergoing pelvic radiotherapy and those with chronic bowel side effects after treatment, a critical review of relevant original studies on human subjects was carried out using a specific set of mesh terms in MEDLINE and EMBASE databases and the Cochrane Library in September 2003. Full texts of all relevant articles were collected and reference lists were checked. Sources of grey literature including conference abstracts and web-based information were also reviewed. A total of 36 papers published in peer-reviewed journals between 1966 and 2003 were identified. In all, 14 randomised controlled trials, 12 prospective cohorts, four retrospective, two qualitative, one validation, one pilot study and two case reports were obtained. These included 2646 patients. Eight articles including three conference abstracts and web-based information were found. None of the studies was definitive because of weakness in methodology. No studies could be combined because the interventions and the end points were different. There is no evidence base for the use of nutritional interventions to prevent or manage bowel symptoms attributable to radiotherapy. Low-fat diets, probiotic supplementation and elemental diet merit further investigation.

Keywords: pelvic radiotherapy, pelvic malignancy, diet, radiation-induced gastrointestinal toxicity, diarrhoea, nutritional status, enteral/parenteral nutrition

A total of 11–12 000 patients with gynaecological, urological and rectal cancer undergo radical pelvic radiotherapy annually in the UK. This reflects about 20% of patients diagnosed with pelvic malignancy (Moller et al, 2003). More than 70% develop acute inflammatory small intestinal changes (Resbeut et al, 1997), leading to gastrointestinal symptoms during treatment partly because healthy bowel tissue is encompassed in the radiation field.

Acute symptoms include diarrhoea, abdominal pain, tenesmus or nausea that usually start during the second or third week of a course of radical radiotherapy and resolve within a fortnight of completion of radiotherapy (Ajlouni, 1999). The incidence of chronic bowel damage is difficult to assess, as patients may be lost to follow-up, may not report any changes to their clinician or may not be identified by scoring systems historically used in clinical trials. In 5–10% of patients, serious gastrointestinal problems may occur (Ooi et al, 1999; Denton et al, 2000; Nostrant, 2002). These include bowel obstruction, fistulation, intractable bleeding or secondary cancers. A further 6–78% of patients develop less severe symptoms, which nevertheless detrimentally affect quality of life (Kollmorgen et al, 1994; Potosky et al, 2000; Gami et al, 2003). These may include urgency, frequency, faecal incontinence, diarrhoea, steatorrhoea, tenesmus, pain, constipation and weight loss (Andreyev et al, 2003). The severity of acute bowel toxicity may predetermine the degree of chronic bowel changes (Donaldson et al, 1975). Therefore, early intervention to prevent or reduce acute toxicity may be worthwhile in the long term.

A number of radiotherapy techniques are used to treat cancers within the pelvis. These may influence the dose that is delivered to the tumour and surrounding structures. Radiotherapy damages tissue because energy dissipated from ionising radiation generates a series of biochemical events inside the cell. Free radicals are formed and disrupt DNA, preventing replication, transcription and protein synthesis. When given in combination with chemotherapy, the risk to normal tissues may be enhanced. The small intestine is particularly susceptible to damage because its cells are usually rapidly proliferating, and bile acid and pancreatic enzymes may potentiate damage to the mucosal glycocalyx (Sullivan, 1962; Mulholland et al, 1984).

Consideration of nutrition before, during and after radiotherapy to the pelvis may be important for several reasons. Nutritional risk describes patients who are likely to develop malnutrition as a result of their illness, but the prognostic significance of nutritional risk is not clear. Malnutrition per se is an independent adverse prognostic factor in many cancers (Bozzetti, 2001). It may occur due to physiological, metabolic, psychological or iatrogenic processes, which exist as a result of malignancy and may affect morbidity, mortality and response to treatment (Argiles and Lopez-Soriano, 1999).

Specific therapeutic nutritional intervention before and during radiotherapy may induce a radio-protective effect for healthy tissues, for example, elemental diet by various mechanisms including attenuation of biliary and pancreatic secretions (McArdle et al, 1974, 1985; Pageau and Bounous, 1977; Mester et al, 1990) or nutritional intervention may be used for its radio-enhancing effect on malignant tissues, for example, polyunsaturated fatty acids (Conklin, 2002).

Manipulation of habitual diet after radiotherapy may help to reduce or eliminate chronic, undesirable changes in bowel habit once they have occurred. A number of dietetic interventions such as lactose restriction, fat restriction, reduced intake of motility stimulants such as caffeine and a decrease in fibre-containing foods (Classen et al, 1998) have been suggested.

This review has two aims. First, to assess the incidence and significance of malnutrition in patients undergoing pelvic radiotherapy and those with chronic bowel side effects resulting from pelvic radiotherapy and second, to examine the efficacy of therapeutic nutritional interventions used to manage gastrointestinal side effects of pelvic radiotherapy.

METHODS

A search of original literature was carried out using MEDLINE and EMBASE databases from 1966 to May 2003 and the Cochrane Library. Animal data were excluded. Search terms included pelvic radiotherapy, gynaecological cancer, elemental diet, probiotics, lactose, reduced fat, enteral nutrition, parenteral nutrition, radiation-induced bowel damage, radiation enteritis, bowel symptoms and diarrhoea. These terms were used to generate reference listings, which were then examined against inclusion and exclusion criteria, and full texts of relevant papers were retrieved. Reference lists in individual papers were checked to identify other relevant publications. Grey literature including abstracts of radiotherapy and nutrition conferences and UK doctoral theses were searched in order to obtain unpublished work in the area. Finally, searches using recognised search engines such as ‘Google’, ‘Microsoft Network’ and ‘Ask Jeeves’ were carried out on the Internet to identify information disseminated to the general public and health professionals via new media, especially regarding nonconventional or complementary nutrition support.

Trials were included if they had recruited patients with gynaecological, rectal or urological malignancy and measured acute or chronic gastrointestinal toxicity to pelvic radiotherapy, while intervening with nutrition to alleviate side effects and/or assessed nutritional status of patients before the start of or during a course of pelvic radiotherapy.

The primary outcome sought was bowel toxicity as assessed by the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group scoring tool (Cox et al, 1995) (Table 1) or other surrogate indicators such as stool frequency and consistency, record of use of antidiarrhoeal medications or patient-reported gastrointestinal symptoms. Secondary outcome measures included nutritional status assessed by change in weight, other anthropometric indicators and changes in dietary intake.

Table 1. RTOG (Radiation Therapy Oncology Group) toxicity criteria.

| Toxicity | Grade 0 | Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower GI including pelvis | No change | Increased frequency or change in quality of bowel habits not requiring medication/rectal discomfort not requiring analgesics | Diarrhoea requiring parasympatholytic drugs (e.g. Lomotil)/mucous discharge not necessitating sanitary pads/rectal or abdominal pain requiring analgesics | Diarrhoea requiring parenteral support/severe mucous or blood discharge necessitating sanitary pads, abdominal distension (flat plate radiograph demonstrated distended bowel loops) | Acute or subacute obstruction, fistula or perforation; GI bleeding requiring transfusion; abdominal pain or tenesmus requiring tube decompression or bowel diversion |

Randomised controlled trials were assessed for methodological quality according to the method of randomisation and group allocation. Studies were graded ‘A’ adequate methodology, ‘B’ inadequate methodology and ‘C’ not stated (The Cochrane Library, 2003). Nonrandomised studies were assessed on methodology and sampling strategy but could not be assessed for quality using any validated grading systems.

RESULTS

A total of 2646 patients in 36 papers and eight sources of grey literature including three conference abstracts and data in non-peer-reviewed journals or the internet, published between 1966 and 2003, were identified. No systematic reviews, 14 randomised controlled trials, 12 prospective cohorts, four retrospective, one validation study, two qualitative, one pilot study and two case reports were retrieved. No papers have been excluded. The papers are summarised in Tables 2, 3, 4 and 5.

Table 2. Prevalence and changes in nutritional status in patients having pelvic radiotherapy.

|

Weight change |

Nutritional status |

Dietary intake |

Bowel toxicity |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Before RT |

After RT |

During RT |

During RT |

After RT |

|||||||

| Author | Study type | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control | Intervention | Control |

| Bye (1992) | Randomised controlled trial | 15% with >5% loss | 12% with >5% loss | 2.6 kg loss | 1.7 kg loss | 9% depleted | 6% depleted | 18 % had a decreased appetite | 20% had a decreased appetite | 23% diarrhoea | 48% diarrhoea |

| Ferguson (1999) | Validation study | — | — | 89% well nourished 11% moderate malnutrition | — | — | |||||

| Hulshof (1987) | Prospective cohort | 4.1 kg decrease from habitual weight (P<0.05) | No change | — | Decreases (P<0.05) in fat, fibre and iron | 29% using constipating diet | |||||

| Pia de la Maza (2001) | Prospective cohort | — | 0.9±1.4 kg decrease (P<0.05) | Decrease of 1.0±1.4% body fat (P<0.05) | — | 87% diarrhoea 80% pain | |||||

| Stryker (1980) | Retrospective cohort | — | 2.91±2.28% weight loss (P<0.05) in 10MV APPA patients | 83% lost weight 13% gained weight | — | 72% >4 stools/day | |||||

Table 3. Dietary modifications during pelvic radiotherapy.

| Study | Study type | n | Intervention |

Bowel toxicity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Brown (1980) | RCT | 68 | Elemental diet | — | — |

| Bye (1992) | RCT | 143 | Low fat; low lactose | 1.1 loose stools/week (P<0.01) | 1.7 loose stools/week |

| Capirci (2000) | RCT | 680 | Elemental diet | 16% Grade 1 | 25% Grade 1 |

| 12% Grade 2 | 27% Grade 2 | ||||

| Chowdury (2002) | RCT | 20 | Micronutrient supplement | — | |

| Craighead (1998) | Phase II feasibility pilot | 17 | Elemental diet | 5.9 (3.4–8.3) days of diarrhoea (P<0.05) | 12.2 (10.2–14.2) days of diarrhoea |

| Delia (2002) | RCT | 190 | VSL #3 probiotic | 0% Grade 4 | 21.4% Grade 4 |

| 65.3% Grade 2 | 23.8% Grade 2 | ||||

| Foster (1980) | RCT | 32 | Elemental diet | — | |

| Karlson (1989) | RCT (conference abstract) | 21 | Low-fat diet | 1.6±0.9 bowel movements/day | 2.0±1.0 bowel movements/day |

| Kinsella (1981) | RCT | 32 | PN | — | |

| Liu (1997) | Retrospective study | 156 | Low residue | Majority Grade 1 | |

| Macia (1991) | RCT | 93 | Protein/calorie supplementation | — | — |

| Martin (2002) | Double-blind RCT | 56 | Enzyme capsule | 57% moderate bowel symptoms | 36% moderate bowel symptoms (P=0.01) |

| Mcardle (1986) | Prospective cohort | 56 | Elemental diet | — | |

| Mccarthy (1999) | Prospective cohort | 40 | Protein/calorie supplementation | — | |

| Moriarty (1981) | RCT | 51 | Protein/calorie supplementation | — | |

| Salminen (1988) | RCT | 24 | L. acidophilus probiotic | 18–27% incidence of diarrhoea (P<0.01) | 80–90% incidence of diarrhoea |

| Stryker (1986) | RCT | 64 | Low lactose | — | — |

| Valerio (1978) | RCT | 20 | PN | — | — |

Table 4. Internet-based information.

| Source | Recommendation | Evidence | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|

| National Cancer Institute www.cancer.gov | Diet low in lactose, fat and residue | ||

| Avoid | It explains that the evidence is not clear but that such a diet can be effective in managing symptoms | No conclusive evidence | |

| Milk and milk products | |||

| Whole bran/cereal, nuts and seeds | |||

| Fried/fatty foods | |||

| Fresh fruit, raw veg | |||

| Strong spices/herbs | |||

| Choc, tea, coffee, caffeinated soft drinks, alcohol | |||

| Ingest foods at room temp | |||

| Drink 3 l fluid, let carbonated drinks lose their fizz | |||

| Add nutmeg to decrease gut motility | |||

| Start low-residue diet on day 1 RT | |||

| Radiation Oncology Online Journal, USA www.rooj.com | Low residue diet | ||

| Increased fluid intake | No references | It is clear why some but not all of the recommendations are made | |

| Small, frequent meals | |||

| Reduce alcohol | |||

| Avoid | |||

| High roughage foods and raw veg | |||

| Tobacco (stimulates gut) | |||

| Food of extreme temps | |||

| Carbonated drinks → cause gas | |||

| Include high potassium foods | |||

| Add nutmeg | |||

| HealthCall-UK www.internethealthlibrary.com | Reduced fat diet | Website refers to papers discussed above | No evidence to make these recommendations |

| Live yogurt and fermented milk products | |||

| Bio Concepts-Cancer Update www.orthoplex.com.au | Vitamin supplementation before commencing treatment to prevent toxicity, including C,E, glutamine, β-carotene, adenosine, cysteine and quercetin | No references included on this web page | Some of the suggestions have been investigated in clinical studies |

| Anti-inflammatory agents during treatment, that is, DHA/EPA, quercetin, adenosine, bromelain, Vitamins E and C | No recommended doses or methods of administration given | However, no conclusive evidence is available | |

| Diet supplementation with glutamine, essential fatty acids and probiotics to prevent radiotherapy-induced diarrhoea | |||

| Supplementing with Coenzyme Q10, acetyl-L-carnitine, lipoic acid and α-ketoglutarate to improve mitochondrial function and thus energy |

Table 5. Dietary modifications after pelvic radiotherapy.

| Study | Study type | n | Intervention |

Bowel toxicity |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intervention | Control | ||||

| Beer (1985) | Prospective cohort | 8 | Elemental diet | Steatorrhoea in seven out of eight patients before intervention | |

| Bosaeus (1979) | Prospective cohort | 9 | Low-fat diet | — | |

| Cohen (1985) | Prospective cohort | 20 | Magnesium | 3 days to stop diarrhoea | 2–6 weeks to stop diarrhoea |

| Danielsson (1991) | Prospective cohort | 7 | Low-fat diet and bile acid sequestrant | Moderate improvement in symptoms in all patients | |

| Donaldson (1975) | Retrospective | 5 | Gluten, cow's milk protein free. Low lactose, fat and residue | All cases asymptomatic at 1 year | |

| El Younis (2003) | Prospective cohort (conference abstract) | 9 | Vitamin C and E | All symptoms subsided at 6–12 weeks | |

| Gami (2003) | Qualitative | 107 | — | — | |

| Haddad (1974) | Case report | 1 | Elemental diet | Symptoms resolved on ED | |

| Henriksson (1995) | Double-blind RCT | 40 | L. Lactis probiotic | — | |

| Kennedy (2001) | Prospective cohort | 20 | Vitamin C and E | Diarrhoea, bleeding and urgency resolved after 4 weeks | |

| Lavery (1980) | Prospective cohort | 5 | PN | — | |

| Levitsky (2003) | Case report | 1 | Vitamin A | Complete regression of pain and symptoms | |

| Miller (1979) | Prospective cohort | 10 | PN | — | |

| Scolapio (2002) | Retrospective | 54 | PN | — | |

| Sekhon (2000) | Qualitative | 48 | — | — | |

| Silvain (1992) | Prospective cohort | 31 | PN | — | |

| Urbancsek (2001) | Double-blind RCT | 206 | L. rhamnosus probiotic | Reduction (P<0.05) in symptoms in both groups. P>0.05 between groups | |

Methodological quality of trials

Approximately half of the papers reviewed were of randomised controlled study design. However, methodology was often weak, with reporting of method of randomisation, concealment of allocation and blinding lacking from many papers (Brown et al, 1980; Foster et al, 1980; Kinsella et al, 1981; Moriarty et al, 1981; Stryker and Bartholomew, 1986; Salminen et al, 1988; Karlson et al, 1989; Bye et al, 1992; Chowdhury et al, 2002; Delia et al, 2002). The choice of randomisation in papers that reported their methodology was adequate in two studies (Urbancsek et al, 2001; Martin et al, 2002). Intention-to-treat analyses were described in two papers (Urbancsek et al, 2001; Martin et al, 2002). It was unclear as to whether such methods were used in other studies. In view of these problems, it is difficult to draw clear conclusions regarding efficacy or effect of the interventions used.

Malnutrition and pelvic radiotherapy

Five papers (one randomised controlled trial (Bye et al, 1992), two prospective cohort (Hulshof et al, 1987; Pia de la Maza et al, 2001), one retrospective (Stryker and Velkley, 1980) and one validation study (Ferguson et al, 1999)) were identified, which assessed the incidence of nutritional risk in patients undergoing pelvic radiotherapy (Table 2). No papers were found that examined whether nutritional status at the start of radiotherapy had any impact on toxicity or outcomes after radiotherapy or the importance of its presence or absence specifically in patients exposed to irradiation to the pelvis. None of the papers assessed the impact of acute diarrhoea on nutritional status, although four of the five identified diarrhoea as an important side effect of treatment, with incidence ranging from 6 to 87%.

Two of the studies (including 121 patients) assessed nutritional risk before starting radiotherapy (Ferguson et al, 1999; Pia de la Maza et al, 2001). The reported incidence ranged from 11 to 33%. Data were based on patient reports of decreased appetite and weight. In total, 5% weight loss before starting treatment was reported to have occurred in 32% of patients (mean percentage, intervention and control groups) by the randomised controlled trial (Bye et al, 1992). The remaining papers (Stryker and Velkley, 1980; Hulshof et al, 1987; Bye et al, 1992) (380 patients) assessed change in nutritional status during pelvic irradiation. The incidence of weight loss during treatment varied from 0 to 83% in these studies.

Nutritional interventions

Dietary modifications during pelvic radiotherapy

In total, 18 studies were identified that examined dietary interventions in adults and children receiving pelvic radiotherapy (Table 3). The search identified studies comparing a range of nutritional interventions:

Low-fat diets with or without additional medium-chain triglyceride supplementation compared with unrestricted fat intake or low-fat diets (Karlson et al, 1989; Bye et al, 1992).

Lactose restriction or modification either uncontrolled (Stryker and Bartholomew, 1986; Bye et al, 1992) or compared to normal diet.

Low residue diet (Liu et al, 1997).

Probiotic supplementation in sachet or fermented yogurt presentation and modified food intake compared with modified food intake alone (Salminen et al, 1988; Delia et al, 2002).

Elemental diet as a supplement to modified food intake or as a sole source of nutritional intake compared to modified diet or total parenteral nutrition (Brown et al, 1980; Foster et al, 1980; McArdle et al, 1986; Craighead and Young, 1998; Capirci and Polico, 2000).

Enteral and parenteral protein-calorie nutrition support (Valerio et al, 1978; Kinsella et al, 1981; Moriarty et al, 1981; Macia et al, 1991; McCarthy and Weihofen, 1999; Chowdhury et al, 2002).

Enzyme preparation supplement (Martin et al, 2002).

Low-fat dietary regimens, using 20–40 g fat per day (Karlson et al, 1989; Bye et al, 1992), induced a significant reduction in diarrhoea, the use of diarrhoea rescue medication and frequency of bowel motions in the 164 patients studied. However, the two studies introduced additional dietary manipulations and did not control for these, which included the use of a medium-chain triglyceride supplement providing 1000 kcal (Karlson et al, 1989) and lactose restriction (Bye et al, 1992), rendering it unclear as to which intervention had the beneficial effect. Another study focused on lactose, using a randomised controlled design that only modified lactose intake (Stryker and Bartholomew, 1986; Bye et al, 1992). No change in bowel symptoms assessed by the RTOG tool were measured in this study (Stryker and Bartholomew, 1986).

A retrospective study assessed the efficacy of introducing a reduced residue regimen in men with prostate cancer undergoing pelvic radiotherapy. It did not identify statistically significant changes in radiotherapy-induced toxicity, particularly gastrointestinal symptoms (Liu et al, 1997). In total, 17% of the patients did not comply with the recommended diet.

Two randomised studies, including 214 patients (Salminen et al, 1988; Delia et al, 2002), used probiotics during pelvic radiotherapy and demonstrated a decrease in the mean number of bowel movements (P<0.05) and a decrease in the incidence of diarrhoea (P<0.01), using VSL #3 sachets three times daily and 2 × 109 daily dose of a L. acidophilus in a fermented yogurt product, respectively. In addition, one of the studies (Salminen et al, 1988) also restricted fibre, fat and obvious sources of lactose in all patients.

Five studies (including 847 patients), of which four were randomised controlled trials (Brown et al, 1980; Foster et al, 1980; McArdle et al, 1986; Capirci and Polico, 2000) and one was a phase II pilot study (Craighead and Young, 1998), investigated the use of elemental diet during pelvic radiotherapy. The type of elemental diet implemented varied between studies in terms of the specific product and the relative caloric contribution it provided.

Three studies including a total of 749 patients found a statistically significant decrease in the incidence and severity of acute diarrhoeal symptoms (McArdle et al, 1986; Craighead and Young, 1998; Capirci and Polico, 2000). However, the largest study, a multicentre 674 patient trial, has been published only as a conference abstract and a non-peer-reviewed summary booklet. Two of the studies (Craighead and Young, 1998; Capirci and Polico, 2000) used elemental diet as a supplement to normal diet, providing approximately 900 kcal per day. The feasibility study carried out in 17 patients indicated that compliance (deemed as achieving the target volume of elemental diet for more than 80% of the time) to the regimen was achieved in 76.5% of the participating patients. One study (McArdle et al, 1986) used elemental diet as the sole source of nutrition in tube-fed patients. The authors revised their methodology and halted randomisation to the parenteral nutrition arm partway through the study. Instead, retrospective controls were used for comparison. They reported a significant perceived benefit in the elementally fed intervention arm. No objective measures were described. Finally, one study (Brown et al, 1980) used an elemental-supplemented regimen, but failed to show any significant differences in bowel symptoms. Controls were asked to follow a low roughage diet, while the treatment group followed the same low roughage diet supplemented with three sachets of ‘Vivonex HN elemental feed’ providing 900 kcal. More than 50% of patients could not manage to consume the Vivonex HN for the whole duration of their radiotherapy.

A study comparing a low-fibre diet (specific content unknown) in controls, with the same diet alongside elemental supplementation (Foster et al, 1980), did not assess the effect of this intervention on gastrointestinal symptoms. Instead, haematological parameters and weight were compared. There were no significant differences in weight loss between groups.

Four randomised controlled trials (including 204 patients) investigated enteral nutrition support during pelvic radiotherapy (Moriarty et al, 1981; Macia et al, 1991; McCarthy and Weihofen, 1999; Chowdhury et al, 2002). There is little detailed information about the clinical effect that this approach had in terms of treatment toxicity. A range of isocaloric, high protein/calorie enteral supplements were used in two studies (Moriarty et al, 1981; McCarthy and Weihofen, 1999) and concluded that the energy and protein intakes of supplemented groups were improved compared to controls. No outcome measures such as toxicity from radiotherapy, tumour control or survival were reported and no significant changes in biochemical or haematological parameters were found.

A study using specific dietary advice to remove gluten and lactose and providing high calorie advice for patients with low appetites (Macia et al, 1991) showed a significant decrease in Body Mass Index and Mid-Arm Muscle Circumference in control group patients, but both groups had similar gastrointestinal toxicity.

Two studies, both randomised (Valerio et al, 1978; Kinsella et al, 1981), evaluated the use of parenteral nutrition vs oral nutrition in patients undergoing pelvic radiotherapy. Both indicated that the side effects of treatment and nutritional status were improved in the parenteral fed arms. A reduction in bulk of tumour by 50% was reported in 45% of the parenteral nutrition group (Valerio et al, 1978). However, in both studies, group allocation methods meant that there was a strong bias towards severely malnourished patients entering the parenteral nutrition arm.

Weight changes

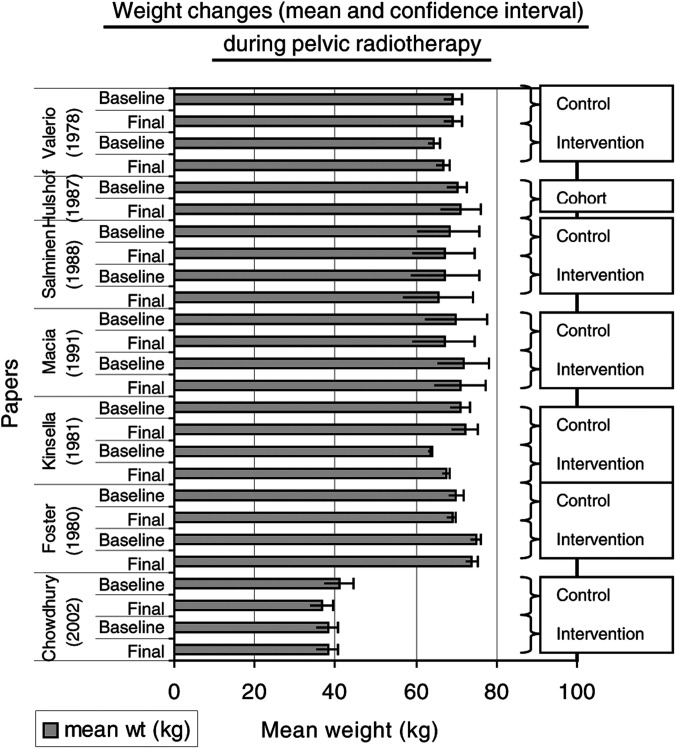

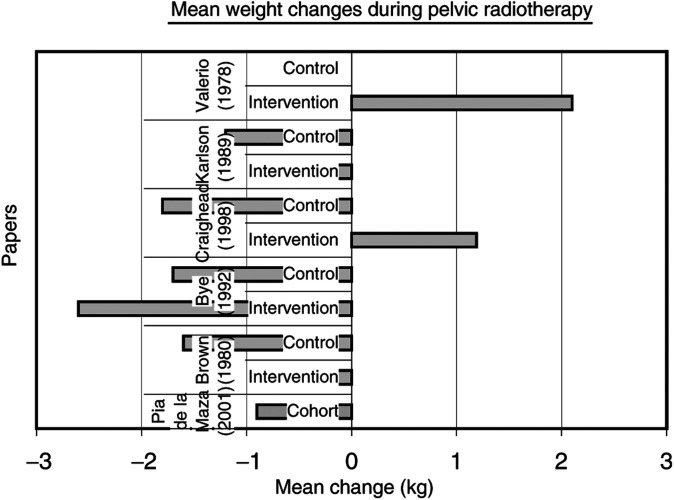

Six papers (Valerio et al, 1978; Foster et al, 1980; Kinsella et al, 1981; Salminen et al, 1988; Macia et al, 1991; Chowdhury et al, 2002) recorded changes in actual body weight during pelvic radiotherapy and these data have been combined and displayed as mean weight in kilograms at baseline and completion of radiotherapy for intervention and control arms. Confidence intervals have been calculated (Figure 1). The mean weight change in kilograms between the start and end of pelvic radiotherapy was recorded in seven papers (Valerio et al, 1978; Brown et al, 1980; Karlson et al, 1989; Bye et al, 1992; Craighead and Young, 1998; Capirci and Polico, 2000; Pia de la Maza et al, 2001) (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Weight changes and pelvic radiotherapy. (A chart depicting changes in actual weight from start to end of pelvic radiotherapy. A comparison between control and intervention groups is shown.)

Figure 2.

Mean change in weight during pelvic radiotherapy.

Anecdotal dietary recommendations

Advice regarding diet during pelvic radiotherapy was commonly related to restriction of fibre, fat and lactose (National Cancer Institute, Radiation Oncology Online Journal, and Healthcall-UK). Less common suggestions included supplementation with a wide range of micronutrients, coenzymes or amino acids (Bio Concepts-Cancer Update website). Other recommendations included avoiding spicy foods, carbonated drinks and food or drink consumed at extremes of temperature. None of these recommendations were referenced (Table 4).

Complementary nutrition

One double-blind randomised controlled trial was identified (Martin et al, 2002). It assessed the efficacy of introducing an enzyme supplement (WOBE-MUGOS – 100 mg papain, 40 mg chymotrypsin and 40 mg trypsin) available in Germany. Three capsules were taken four times each day. On a diarrhoea scale of 0–3 (0 to >6 bowel movements per day), 43% of the intervention and 64% of the control group experienced only mild symptoms during pelvic radiotherapy. In all, 57% of the intervention and 36% of the control group were rated as having moderate or severe bowel symptoms (P=0.11). The Bristol Cancer Help Centre website provided some information regarding diet during radiotherapy. In addition to their controversial restrictive dietary advice aimed at all patients with cancer, there was specific advice to reduce fibre while having radiotherapy to the pelvis.

Dietary modifications after pelvic radiotherapy

In total, 17 studies examined the use of dietary modification after pelvic radiotherapy to help to reduce or resolve existing postirradiation gastrointestinal symptoms (Table 5). The nutritional interventions included:

Probiotic supplementation in fermented milk or sachet presentation compared to placebo (Henriksson et al, 1995; Urbancsek et al, 2001).

Elemental diet (uncontrolled) (Beer et al, 1985).

Low-fat diet (uncontrolled) or low fat with bile acid sequestrant (Bosaeus et al, 1979; Danielsson et al, 1991).

Gluten and cow's milk protein free with additional lactose and reduced fat/residue (Donaldson et al, 1975).

Parenteral nutrition support (Haddad et al, 1974; Miller et al, 1979; Lavery et al, 1980; Silvain et al, 1992; Scolapio et al, 2002).

Reduction of high-fibre foods (Sekhon, 2000; Gami et al, 2003).

Vitamin A, vitamins C and E and magnesium micronutrient therapy (Cohen and Kitzes, 1985; Kennedy et al, 2001; El Younis and Abulafia, 2003; Levitsky et al, 2003).

Probiotics were used in two double-blinded randomised studies (Henriksson et al, 1995; Urbancsek et al, 2001), which included 246 patients. These were supplemented into diet as 300 ml twice daily of a fermented yogurt product containing active L1A Lactobacillus lactis and one Lactobacillus rhamnosus sachet three times daily, respectively. Neither study identified significant improvements in chronic bowel symptoms in patients randomised to the intervention. In one trial (Henriksson et al, 1995), gastrointestinal symptoms improved in both groups. However, the control group was taking a placebo probiotic supplement containing strains thought not to be relevant for gastrointestinal symptoms.

Elemental diet as a complete source of nutrition was investigated in a crossover study to manage chronic diarrhoea after pelvic radiotherapy in a group of five malnourished patients from a cohort with chronic pelvic radiation complications (Beer et al, 1985). A decrease in faecal weight and the absence of abnormal hydrogen breath tests were reported. Diarrhoeal symptom scores were not measured. A case report (Haddad et al, 1974) using exclusive long-term oral elemental diet (27 kcal kg−1 day−1 with 8% medium chain triglyceride) to treat a patient with abdominal distension, malabsorption and pain showed complete resolution of symptoms while the patient consumed this diet.

Low-fat dietary regimens were used in two studies (Bosaeus et al, 1979; Danielsson et al, 1991), which included 187 patients. A significant reduction in bile salt malabsorption using a 40 g fat−1 day−1 diet in nine patients was reported (Bosaeus et al, 1979). The other study (Danielsson et al, 1991) observed only a moderate improvement in symptoms with the use of a bile acid sequestrant in addition to a low-fat diet.

A gluten-free, cow's milk protein-free, low-residue and low-fat diet was implemented in children with severe radiation enteritis following pelvic irradiation (Donaldson et al, 1975). The five case reports suggested that malabsorption and overall nutritional status could be improved with this dietary intervention.

Four cohort studies in patients with chronic, intractable bowel damage after radiotherapy (Miller et al, 1979; Lavery et al, 1980; Silvain et al, 1992; Scolapio et al, 2002) assessed parenteral nutrition support in a total of 100 patients. Cyclical nocturnal parenteral nutrition was unsuccessful in controlling severe radiation enteritis symptoms in 48% of the patients (Silvain et al, 1992). Nutritional status improved in a small cohort (Lavery et al, 1980). Parenteral nutrition was administered for 6–30 months and once weight had stabilised, a mean increase of 12.9 kg was reported. This is in agreement with a similar cohort study (Miller et al, 1979), which reported a 60% survival rate at 1 year with a mean weight gain of 8.7 kg (−2.1 to 15). A retrospective study indicated that cumulative survival in patients supported by home parenteral nutrition was 76% at 1 year. There were no comments regarding whether any of the symptoms attributed to radiation bowel damage changed over that period.

Relevant qualitative research was also identified (Sekhon, 2000; Gami et al, 2003). Two studies assessed self-imposed changes to dietary intake made by patients with bowel discomfort after radiotherapy. More than 50% of women with chronic bowel change reported increased stool frequency with consumption of bran, pulses and nuts. In 107 patients (Gami et al, 2003), no dietary manipulation gave consistent benefit, except for 14 out of 15 patients who eliminated or reduced intake of uncooked vegetables from their diet and reported that bowel symptoms had improved.

The use of micronutrient supplementation in patients with proctitis and other large bowel damage resulting from pelvic radiotherapy has been reported in three studies (Cohen and Kitzes, 1985; Kennedy et al, 2001; Levitsky et al, 2003) and one conference abstract (El Younis and Abulafia, 2003) with a combined total of 50 patients. An oral dose of 8000 IU vitamin A twice daily administered over 7 weeks is described in a case report (Levitsky et al, 2003). All pain and clinical signs of anal ulceration resolved after this intervention. Therapeutic doses of vitamin C (500 mg three times daily) and vitamin E (400 IU three times daily) in combination have been used in two studies to treat radiation proctitis (Kennedy et al, 2001; El Younis and Abulafia, 2003). Statistically significant improvements in patient-reported symptoms of bleeding, diarrhoea and urgency, but not pain, were noted and of those patients followed to 1 year, symptom regression was sustained (Kennedy et al, 2001). The other study reported all symptoms subsiding by 6–12 weeks of treatment (El Younis and Abulafia, 2003). Finally, a small cohort study described rapid resolution of diarrhoeal symptoms in patients with hypomagnesaemia and radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis with intravenous infusion of magnesium sulphate over 3 days, compared to delayed response on a low-residue diet and use of antidiarrhoeal medication (Cohen and Kitzes, 1985).

DISCUSSION

This review suggests that the incidence of malnutrition in patients about to start pelvic radiotherapy is 11–33%. Up to 83% of patients lost weight during treatment. Low-fat diets, probiotic supplementation and elemental diet may be beneficial in preventing acute gastrointestinal symptoms. The evidence for the use of nutritional intervention to manage chronic gastrointestinal symptoms is limited. The use of low-fat diets, therapeutic doses of antioxidant vitamins and probiotic supplementation may be helpful. A reduced intake of raw vegetables and fibrous foods may also be effective.

While these conclusions are based on rather weak evidence, they are supported by findings in other disease states. The use of elemental diets to induce remission in Crohn's disease is well established (O'Morain et al, 1984; Saverymuttu et al, 1985; Gorard et al, 1993). Acute radiation bowel damage is also characterised by an inflammatory response. The fat composition of an enteral feed may be important in achieving remission in Crohn's disease (Griffiths et al, 1995; Bamba et al, 2003). Enteral feeds containing higher proportions of medium-chain triglycerides and n-3 long-chain fatty acids have been reported in studies to infer favourable outcomes when compared with n-6 long-chain fatty acids. This is probably due to their role in the production of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), abundant in fish oils, which have anti-inflammatory effects as opposed to n-6 fatty acids, precursors of arachidonic acid, the substrate for inflammatory eicosanoids (Gorard, 2003). Either this mechanism or its role in reducing the metabolic workload of the gut, or its effects on bile acid or pancreatic enzyme secretion, may explain why elemental diet could be helpful during radiotherapy. Further detailed study is required.

There is also a rationale for the beneficial effect of probiotics in radiation-induced damage. Pathogenic bacterial colonisation can increase the severity of radiation-induced diarrhoea (Urbancsek et al, 2001). Re-colonisation with an optimal species could attenuate such an effect (Urbancsek et al, 2001). Probiotic bacteria can also signal with the gastrointestinal epithelium via mucosal regulatory T-cells to modulate intestinal inflammation (Caradonna et al, 2000). Lactose intolerance secondary to an inflamed mucosa can be resolved using probiotic bacteria, which can potentially ferment luminal lactose to prevent osmotic diarrhoea from occurring.

Finally, ionising radiation is a pro-oxidant process and creates free radicals. Antioxidant vitamins A, C and E may have a synergistic effect in scavenging reactive oxygen species and play a beneficial role in the molecular mechanism of ischaemic injury in the gut (Empey et al, 1992). For these reasons, supplementation with therapeutic doses to patients with chronic radiation bowel damage, which is a vascular, non inflammatory process, may improve clinical symptoms (Thomson et al, 1998).

There is a scientific basis for studies of nutritional intervention in humans. A large number of animal experiments have identified potential physiological mechanisms occurring in the small and large intestine during and after pelvic radiotherapy. Interventional studies using elemental diet, micronutrient supplementation and probiotics suggest that some of these physiological mechanisms can be blocked, leading to significant reduction in radiation damage (Hugon and Bounous, 1972, 1973; Bounous et al, 1973; Pageau et al, 1975; Pageau and Bounous, 1977; McArdle et al, 1985, 1986; McArdle, 1994; Wiseman et al, 1996; Mutlu-Turkoglu et al, 2000).

The primary aim of nutritional intervention should be to show benefit in relevant outcomes using adequate tools to measure gastrointestinal toxicity. Most published studies have failed to do this either because of inadequacies in their methodology or because they fail to report important end points.

There are many key questions that remain to be answered. What physiological changes occur in the human gastrointestinal tract when the pelvis is irradiated? How significant are such changes? Can a specific nutritional intervention given during pelvic radiotherapy modulate individual physiological changes? Does this prevent the onset or reduce the severity of clinically occurring gastrointestinal symptoms? When should nutritional intervention be given? How should it be given? Which formulations would enable compliance? Which patients would benefit from intervention?

To begin to answer these questions, well-designed randomised studies are needed. Health professionals working with these patients who may not be trained in nutrition will need to adopt a multidisciplinary approach to research. Patients need to consent to participate in randomised studies in which they may not receive the perceived ‘beneficial’ intervention. This is difficult at a time of high anxiety and uncertainty as a result of their diagnosis. Finally, appropriate end points using established, comprehensive, validated assessment techniques must be incorporated in studies that are large enough to answer the questions asked, to ensure that the results obtained are meaningful in relation to clinical practice.

Gastrointestinal symptoms induced by pelvic radiotherapy can cause morbidity and distress in the acute phase during treatment and can also develop into a chronic, intractable form months or years after the cessation of treatment (Denton et al, 2002). Increasingly, patients are being treated successfully and curatively (UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party, 1996). However, if life expectancy is increased then it is even more crucial to ensure that an individual patient's quality of life remains high and is not detrimentally affected by the very treatment that has saved their life. To conclude, it is imperative that well-designed randomised controlled studies are carried out to evaluate the nutritional interventions that have been identified by current literature as having potential benefit in patients treated with pelvic radiotherapy.

Acknowledgments

HJN Andreyev has received an unrestricted educational grant from SHS International.

References

- Ajlouni M (1999) Radiation-induced proctitis. Curr Treat Opt Gastroenterol 2: 20–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreyev H, Amin Z, Blake P, Dearnaley D, Tait D, Vlavianos P (2003) GI symptoms developing after pelvic radiotherapy require gastroenterological review. Gut 52: A90 [Google Scholar]

- Argiles J, Lopez-Soriano F (1999) The role of cytokines in cancer cachexia. Med Res Rev 19: 223–248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bamba T, Shimoyama T, Sasaki M, Tsujikawa T, Fukuda Y, Koganei K, Hibi T, Iwao Y, Munakata A, Fukuda S, Matsumoto T, Oshitani N, Hiwatashi N, Oriuchi T, Kitahora T, Utsunomiya T, Saitoh Y, Suzuki Y, Nakajima M (2003) Dietary fat attenuates the benefits of an elemental diet in active Crohn's disease: a randomized, controlled trial. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beer W, Fan A, Halsted C (1985) Clinical and nutritional implications of radiation enteritis. Am J Clin Nutr 41: 85–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosaeus I, Andersson H, Nystrom C (1979) Effect of a low-fat diet on bile salt excretion and diarrhoea in the gastrointestinal radiation syndrome. Acta Radiol Oncol Radiat Phys Biol 18: 460–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bounous G, Devroede G, Hugon JS, Charuel C (1973) Effects of an elemental diet on the pancreatic proteases in the intestine of the mouse. Gastroenterology 64: 577–582 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozzetti F (2001) Nutrition Support in Patients with Cancer. London: Greenwich Medical Media Ltd [Google Scholar]

- Brown MS, Buchanan RB, Karran SJ (1980) Clinical observations on the effects of elemental diet supplementation during irradiation. Clin Radiol 31: 19–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bye A, Kaasa S, Ose T, Sundfor K, Trope C (1992) The influence of low fat, low lactose diet on diarrhoea during pelvic radiotherapy. Clin Nutr 11: 147–153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capirci C, Polico C, Amichetti M, Bonetta A, Gava A, Maranzano E, Turcato G, Valentini V (2000) Diet prevention of radiation acute enteric toxicity: multicentric randomised study. Radiother Oncol 56(Suppl 1): S44 [Google Scholar]

- Caradonna L, Amati L, Magrone T, Pellegrino N, Jirillo E, Caccavo D (2000) Enteric bacteria, lipopolysaccharides and related cytokines in inflammatory bowel disease: biological and clinical significance. J Endotoxin Res 6: 205–214 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury Q, Elahi F, Olson K, Khaled M (2002) Adjuvant nutritional therapy in the management of malnourished cancer patients. Pakistan J Nutr 1: 119–120 [Google Scholar]

- Classen J, Belka C, Paulsen F, Budach W, Hoffman W, Bamberg M (1998) Radiation-induced gastrointestinal toxicity. Pathophysiology, approaches to treatment and prophylaxis. Strahlenther Onkol 174: 82–84 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen L, Kitzes R (1985) Early radiation-induced proctosigmoiditis responds to magnesium therapy. Magnesium 4: 16–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conklin K (2002) Dietary polyunsaturated fatty acids: impact on cancer chemotherapy and radiation. Altern Med Rev 7: 4–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox JD, Stetz J, Pajak TF (1995) Toxicity criteria of the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group (RTOG) and the European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer (EORTC). Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 31: 1341–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craighead PS, Young S (1998) Phase II study assessing the feasibility of using elemental supplements to reduce acute enteritis in patients receiving radical pelvic radiotherapy. Am J Clin Oncol 21: 573–578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielsson A, Nyhlin H, Persson H, Stendahl U, Stenling R, Suhr O (1991) Chronic diarrhoea after radiotherapy for gynaecological cancer: occurrence and aetiology. Gut 32: 1180–1187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delia P, Sansotta G, Donato V, Messina G, Frosina P, Pergolizzi S, De Renzis C (2002) Prophylaxis of diarrhoea in patients submitted to radiotherapeutic treatment on pelvic district: personal experience. Digest Liver Dis 34: S84–S86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton A, Bond S, Matthews S, Bentzen S, Maher E (2000) National audit of the management and outcome of carcinoma of the cervix treated with radiotherapy in 1993. Clin Oncol (Roy Coll Radiol) 12: 347–353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denton A, Forbes A, Andreyev J, Maher EJ (2002) Non surgical interventions for late radiation proctitis in patients who have received radical radiotherapy to the pelvis. Cochrane Database System Review, CD003455 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Donaldson S, Jundt S, Ricour C, Sarrazin D, Lemerie J, Schweisguth O (1975) Radiation enteritis in children. A retrospective review, clinicopathologic correlation and dietary management. Cancer 35: 1167–1178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Younis C, Abulafia O (2003) The therapeutic role of antioxidant vitamins: C and E in radiation-induced rectal injury. Gastroenterology 124(4, Suppl 1): S1771 [Google Scholar]

- Empey LR, Papp JD, Jewell LD, Fedorak RN (1992) Mucosal protective effects of vitamin E and misoprostol during acute radiation-induced enteritis in rats. Dig Dis Sci 37: 205–214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson M, Bauer J, Gallagher B, Capra S, Christie D, Mason B (1999) Validation of a malnutrition screening tool for patients receiving radiotherapy. Australas Radiol 43: 325–327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster KJ, Brown MS, Alberti KG, Buchanan RB, Dewar P, Karran SJ, Price CP, Wood PJ (1980) The metabolic effects of abdominal irradiation in man with and without dietary therapy with an elemental diet. Clin Radiol 31: 13–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gami B, Harrington K, Blake P, Dearnaley D, Tait D, Davies J, Norman AR, Andreyev HJ (2003) How patients manage gastrointestinal symptoms after pelvic radiotherapy. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 18: 987–994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorard DA (2003) Enteral nutrition in Crohn's disease: fat in the formula. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 15: 115–118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorard DA, Hunt JB, Payne-James JJ, Palmer KR, Rees RG, Clark ML, Farthing MJ, Misiewicz JJ, Silk DB (1993) Initial response and subsequent course of Crohn's disease treated with elemental diet or prednisolone. Gut 34: 1198–1202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths AM, Ohlsson A, Sherman PM, Sutherland LR (1995) Meta-analysis of enteral nutrition as a primary treatment of active Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology 108: 1056–1067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haddad H, Bounous G, Tahan WT, Devroede G, Beaudry R, Lafond R (1974) Long-term nutrition with an elemental diet following intensive abdominal irradiation:report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 17: 373–375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson R, Franzen L, Sandstrom K, Nordin A, Arevarn M, Grahn E (1995) Effects of active addition of bacterial cultures in fermented milk to patients with chronic bowel discomfort following irradiation. Support Care Cancer 3: 81–83 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugon JS, Bounous G (1972) Elemental diet in the management of the intestinal lesions produced by radiation in the mouse. Can J Surg 15: 18–26 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hugon JS, Bounous G (1973) Protective effect of an elemental diet on radiation enteropathy in the mouse. Strahlentherapie 146: 701–712 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulshof K, Gooskens A, Wedel M, Bruning P (1987) Food intake in three groups of cancer patients. A prospective study during cancer treatment. Hum Nutr: Appl Nutr 41A: 23–37 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlson S, Kahn JM, Portman W, Simonsen E, Onk Klin G (1989) A randomised trial with low fat diets to improve food intake and tolerance in women receiving abdominal radiotherapy for cancer. Clin Nutr 8(Special Suppl): 39 [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy M, Bruninga K, Mutlu EA, Losurdo J, Choudhary S, Keshavarzian A (2001) Successful and sustained treatment of chronic radiation proctitis with antioxidant vitamins E and C. Am J Gastroenterol 96: 1080–1084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella T, Malcolm A, Bothe A, Valerio D, Blackburn G (1981) Prospective study of nutritional support during pelvic irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 7: 543–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kollmorgen C, Meagher A, Wolff B, Pemberton J, Martenson J, Ilstrup D (1994) The long-term effect of adjuvant post-operateive chemoradiotherapy for rectal carcinoma on bowel function. Ann Surg 220: 676–682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavery IC, Steiger E, Fazio VW (1980) Home parenteral nutrition in management of patients with severe radiation enteritis. Dis Colon Rectum 23: 91–93 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitsky J, Hong JJ, Jani AB, Ehrenpreis ED (2003) Oral vitamin a therapy for a patient with a severely symptomatic postradiation anal ulceration: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum 46: 679–682 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Glicksman A, Coachman N, Kuten A (1997) Low acute gastrointestinal and genitourinary toxicities in whole pelvic irradiation of prostate cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 38: 65–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macia E, Moran J, Santos J, Blanco M, Mahedero G, Salas J (1991) Nutritional evaluation and dietetic care in cancer patients treated with radiotherapy: prospective study. Nutrition 7: 205–209 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin T, Uhder K, Kurek R, Roeddiger S, Schneider L, Vogt HG, Heyd R, Zamboglou N (2002) Does prophylactic treatment with proteolytic enzymes reduce acute toxicity of adjuvant pelvic irradiation? Results of a double-blind randomized trial. Radiother Oncol 65: 17–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle AH (1994) Protection from radiation injury by elemental diet: does added glutamine change the effect? Gut 35: S60–S64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle AH, Echave W, Brown RA, Thompson AG (1974) Effect of elemental diet on pancreatic secretion. Am J Surg 128: 690–692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle AH, Reid EC, Laplante MP, Freeman CR (1986) Prophylaxis against radiation injury. The use of elemental diet prior to and during radiotherapy for invasive bladder cancer and in early postoperative feeding following radical cystectomy and ileal conduit. Arch Surg 121: 879–885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle AH, Wittnich C, Freeman CR, Duguid WP (1985) Elemental diet as prophylaxis against radiation injury. Histological and ultrastructural studies. Arch Surg 120: 1026–1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy D, Weihofen D (1999) The effect of nutritional supplements on food intake in patients undergoing radiotherapy. Oncol Nursing Forum 26: 897–900 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mester M, Hoover HC, Compton C, Willett CG (1990) Experimental aspects of elemental diets as radioprotectors. ABCD Arq Bras Circ Dig 5: 17–26 [Google Scholar]

- Miller DG, Ivey M, Young J (1979) Home parenteral nutrition in treatment of severe radiation enteritis. Ann Intern Med 91: 858–860 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moller H, Anderson O, Dolbear C, Linklater K, Mak V, Massey T, Oskooei B (2003) Cancer in South East England 2000, pp 12–45. London: Thames Cancer Registry [Google Scholar]

- Moriarty M, Moloney M, Mulgrew S, Daly L (1981) A randomised study of dietary intake in patients undergoing radiation therapy. Irish Med J 74: 39–42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulholland MW, Levitt SH, Song CW, Potish RA, Delaney JP (1984) The role of luminal contents in radiation enteritis. Cancer 54: 2396–2402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu-Turkoglu U, Erbil Y, Oztezcan S, Olgac V, Toker G, Uysal M (2000) The effect of selenium and/or vitamin E treatments on radiation-induced intestinal injury in rats. Life Sci 66: 1905–1913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nostrant TT (2002) Radiation injury. In Textbook of Gastroenterology, Yamada T, Alpers DH, Owyans C, Powell DW, Silverstein FE (eds). pp 2605–2616. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippencott [Google Scholar]

- O'Morain C, Segal AW, Levi AJ (1984) Elemental diet as primary treatment of acute Crohn's disease: a controlled trial. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 288: 1859–1862 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ooi B, Tjandra J, Green M (1999) Morbidities of adjuvant chemotherapy and radiotherapy for resectable rectal cancer. Dis Colon Rectum 42: 403–418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pageau R, Bounous G (1977) Systemic protection against radiation. III. Increased intestinal radioresistance in rats fed a formula-defined diet. Radiat Res 71: 622–627 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pageau R, Lallier R, Bounous G (1975) Systemic protection against radiation. I. Effect of an elemental diet on hematopoietic and immunologic systems in the rat. Radiat Res 62: 357–363 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pia de la Maza M, Gotteland M, Ramirez C, Araya M, Yudin T, Bunout D, Hirsch S (2001) Acute nutritional and intestinal changes after pelvic radiation. J Am Coll Nutr 20: 637–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potosky A, Legler J, Albertsen P, Stanford J, Gilliland F, Hamilton A (2000) Health outcomes after prostatectomy or radiotherapy for prostate cancer: results from the prostate cancer outcomes study. J Natl Cancer Inst 92: 1582–1592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Resbeut M, Marteau P, Cowen D, Richaud P, Bourdin S, Dubois JB, Mere P, N'Guyen TD (1997) A randomized double blind placebo controlled multicenter study of mesalazine for the prevention of acute radiation enteritis. Radiother Oncol 44: 59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salminen E, Elomaa I, Minkkinen J, Vapaatalo H, Salminen S (1988) Preservation of intestinal integrity during radiotherapy using live Lactobacillus acidophilus cultures. Clin Radiol 39: 435–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saverymuttu S, Hodgson HJ, Chadwick VS (1985) Controlled trial comparing prednisolone with an elemental diet plus non-absorbable antibiotics in active Crohn's disease. Gut 26: 994–998 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scolapio J, Ukleja A, Burnes J, Kelly D (2002) Outcome of patients with radiation enteritis treated with home parenteral nutrition. Am J Gastroenterol 97: 662–666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekhon S (2000) Chronic radiation enteritis: women's food tolerances after radiation treatment for gynaecologic cancer. J Am Diet Assoc 100: 941–943 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silvain C, Besson I, Ingrand P, Beau P, Fort E, Matuchansky C, Carretier M, Morichau-Beauchant M (1992) Long-term outcome of severe radiation enteritis treated by total parenteral nutrition. Dig Dis Sci 37: 1065–1071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker J, Bartholomew M (1986) Failure of lactose-restricted diets to prevent radiation-induced diarrhoea in patients undergoing whole pelvis irradiation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 12: 789–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stryker J, Velkley D (1980) Weight loss during pelvic irradiation: cobalt-60 vs 10 MV. Strahlentherapie 156: 754–758 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sullivan MF (1962) Dependence of radiation diarrhoea on the presence of bile in the intestine. Nature 195: 1217–1218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Cochrane Library (2003) The Reviewer's Handbook (Issue 2). Oxford: The Cochrane Library [Google Scholar]

- Thomson A, Hemphill D, Jeejeebhoy KN (1998) Oxidative stress and antioxidants in intestinal disease. Dig Dis 16: 152–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- UKCCCR Anal Cancer Trial Working Party (1996) Epidermoid anal cancer: results from the UKCCCR randomised trial of radiotherapy alone versus radiotherapy, 5-flourouracil and mitomycin. Lancet 19: 1049–1054 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbancsek H, Kazar T, Mezes I, Neumann K (2001) Results of a double-blind, randomised study to evaluate the efficacy and safety of Antibiophilus in patients with radiation-induced diarrhoea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 13: 391–396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio D, Overett L, Malcolm A, Blackburn GL (1978) Nutritional support for cancer patients receiving abdominal and pelvic radiotherapy: a randomised prospective clinical experiment of intravenous versus oral feeding. Surg Forum 29: 145–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman JS, Senagore AJ, Chaudry IH (1996) Relationship of pelvic radiation to intestinal blood flow. J Surg Res 60: 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]