Abstract

Preventive care measures remain underutilized despite recommendations to increase their use. The objective of this review was to examine the characteristics, types, and effects of paper- and computer-based interventions for preventive care measures. The study provides an update to a previous systematic review. We included randomized controlled trials that implemented a physician reminder and measured the effects on the frequency of providing preventive care. Of the 1,535 articles identified, 28 met inclusion criteria and were combined with the 33 studies from the previous review. The studies involved 264 preventive care interventions, 4,638 clinicians and 144,605 patients. Implementation strategies included combined paper-based with computer generated reminders in 34 studies (56%), paper-based reminders in 19 studies (31%), and fully computerized reminders in 8 studies (13%). The average increase for the three strategies in delivering preventive care measures ranged between 12% and 14%. Cardiac care and smoking cessation reminders were most effective. Computer-generated prompts were the most commonly implemented reminders. Clinician reminders are a successful approach for increasing the rates of delivering preventive care; however, their effectiveness remains modest. Despite increased implementation of electronic health records, randomized controlled trials evaluating computerized reminder systems are infrequent.

Introduction

The U.S. Preventive Task Force developed guidelines to facilitate the dissemination and implementation of preventive care measures among health care providers. 1,2 Opportunities for offering patients preventive care measures exist during most encounters with the health care system, 3 such as vaccinations during primary care visits, 4 prophylactic aspirin and vaccinations prior to discharge from the hospital, 5 or vaccinations during an emergency department visit. 6 However, preventive care measures remain underutilized 5,7,8 and clinicians struggle with finding time to be compliant with offering the numerous recommended examinations and procedures when a patient's primary visit reason is unrelated to prevention. 9 For example, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services' Healthy People 2010 target for colorectal cancer screening is 50%, but only 35% of eligible people have a screening examination. 1 Similarly, the 70% influenza and 65% pneumococcal vaccination rate for patients aged 65 years and older are considerably below the 90% target. 10 In a US study examining 38 different preventive care quality indicators patients received only 54.9% of recommended preventive care measures. 8

Different implementation approaches to increase preventive care measures have demonstrated various levels of success. Successful approaches include organizational change interventions, financial incentives, or patient and provider reminders. 11–13 With the increased implementation of clinical information systems, broader adoption and application of information technology for patient care, including preventive care applications, can be expected. In the ambulatory setting computer-based reminders increased the implementation of some preventive care measures, but failed in others. 14,15 In an outpatient setting computerized prompts were more effective at increasing influenza vaccination rates when compared to paper-based reminders. 16 Balas et al. examined the effect of various intervention techniques for prompting physicians. 17 The study included reports from 1966 to 1996 and found that the average rate difference for adherence to recommended preventive care strategies using computer-generated reminders did not differ from non-computerized prompting approaches.

Although a recent US national survey 18 suggested that the application of information technology is associated with increased physician reminder use, there is limited information whether the recent focus on implementing clinical information systems has provided the infrastructure to support the development and application of computer-based reminder systems for preventive care. The goal of this systematic literature review was to update the study by Balas et al., 17 which included 16 preventive care measures from the US Preventive Task Force, and to examine whether the amount of computerized reminder systems for preventive care have changed as clinicians increasingly utilize electronic health record systems when providing patient care.

Methods

Literature Search

The study methodology from Balas et al. was adopted to perform a systematic review of the literature regarding 16 preventive medicine reminders to clinicians. 17 Eligible studies included randomized controlled trials that targeted clinicians and applied a reminder system for at least one of 16 preventive medicine procedures: fecal occult blood testing; mammography; Papanicolaou smear; influenza, pneumococcal or tetanus vaccination; diabetes mellitus management; cholesterol screening; hemoglobin or blood pressure management; cardiac care; smoking cessation; glaucoma screening; alcohol abuse counseling; prenatal care; and tuberculin testing.

For the period January 1, 1997 to December 31, 2004, we queried the electronic literature databases PUBMED® (MEDLINE®), 19 OVID CINAHL®, 20 ISI Web of Science™, 21 Health and Psychosocial Instruments, 20 and the Health Reference Center. 22 The search was limited to studies published in English. In each database we searched for the combination of the following three concepts: (1) preventive care measure; (2) reminder system; and (3) randomized clinical trial. In MEDLINE, all search terms were defined as Medical Subject Headings (MeSH®) unless otherwise noted and were searched as they appear below; in the remaining databases, the search terms were defined only as keywords.

1 Preventive care measure: preventive health services, immunization, vaccination, smoking, smoking cessation, mass screening, mammography, prenatal care, hypertension, blood pressure, diabetes mellitus, alcoholism, substance-related disorders, vaginal smears, hypercholesterolemia, glaucoma, or occult blood.

2 Reminder system: checklist (text word), encounter forms (text word), tags (text word), triggers (text word), reminder systems, alert (text word), reminder (text word), leaflets (text word), stickers (text word), messages (text word), or tailored messages (text word).

3 Randomized clinical trial: random$ (truncated text word), group$ (truncated text word), random allocation, randomized controlled trial (publication type), or clinical trial (publication type).

Review of Identified Studies

The title and abstract of all articles identified using the keyword searches were retrieved and reviewed by two of four independent reviewers (JWD, DLS, SR, DA). Disagreements between two reviewers were resolved by consensus among all four participating reviewers. The bibliographies of identified systematic reviews and meta-analyses were reviewed and additional relevant studies were included. The full text of included articles was obtained and two reviewers (JWD, DA) independently scored each article using the quality assessment instrument that was applied during the previous study. 17 Disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion. The assessment instrument included ten criteria evaluating the study characteristics (randomization techniques, testing, withdrawals, effect variables) and assigned a summary score between 0 and 100. 23 Five criteria examine the methodology and characteristics of the study design. Following the previous review methodology articles scoring below 50 were excluded from further consideration. 23 All included studies were examined for redundancy and duplicate results were removed.

Reminder implementations were classified as “paper-based,” “computer-generated,” or “computerized.” Paper-based reminders included the use of memos, stickers, or a slip of paper within the patient's chart. Computer-generated reminders included application of computerized algorithms to identify eligible patients, but the prompt was printed out and placed in the patient chart to remind the clinician. Computerized reminders included prompts that were entirely electronic, i.e., computerized algorithms identified eligible patients, and prompts were provided upon access to the electronic clinical information system.

Analysis

We combined the articles from the previous review (1966 to 1996) 17 with the newly identified articles (1997 to 2004). In studies with more than one preventive care prompt, each intervention was analyzed separately for the effect of the prompt on the given procedure. For example, if a vaccination study compared a paper-based versus a computer-based implementation approach, each approach was counted and examined individually. For each study, the intervention effect was calculated by subtracting the control or baseline data from the largest increase in effect. The unweighted difference in rates of each study was averaged to create the average effect for each implementation strategy, reminder strategy, or intervention. Odds ratios were converted into percentages for data analysis measures. Agreement among reviewers to consider articles based on title and abstract was high (0.96 to 0.99), as determined by Yule's Q. 24

Results

Search Results

The literature search produced 1,535 articles during the time period from 1997 to 2004 (▶). The MEDLINE search contributed 1,308 articles, CINAHL 148, Health and Psychological Instruments three, the Health Reference Center two, and ISI Web of Knowledge 74. After removing 131 duplicate articles, 1,396 were further excluded based on the review of the abstracts. Of the remaining 35 reports, 11 were excluded from further analysis (nine scored less than 50 in the quality assessment, one examined only the system design, and one had no clinician prompt). Reviews of reference lists accounted for an additional 9 articles with 4 meeting inclusion criteria, for a total of 28 included studies. One paper had no numerical results and was not included in the average effect calculations. 25 One paper had redundant results and these were removed for analysis. 26 We combined the 28 trials with the previous 33 studies for a total of 61 studies. 4,5,25-83 ▶ shows the detailed characteristics of the included studies.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of included and excluded studies (1997 to 2004).

Table 1.

Table 1 Study Characteristics, Grouped by Implementation Strategy

| Source |

Reminder |

Clinicians |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Author | Year | Targeted Action a | Paper-based | Computer-generated | Computerized | Institution | Study setting | Patients | Clinicians | Provider type | Specialty | Study Locations |

| 27 | Bankhead | 2001 | CaScr | In Chart | non-acad | o | 1158 | 13 | MDa | GP | Birmingham; North of London; West of London | ||

| 28 | Cheney | 1987 | Immun, CaScr, Chol | Front | acad | o | 200 | 75 | MDr | IM | University of California, San Diego | ||

| 29 | Cohen | 1982 | Immun, CaScr | Front | acad | o | 2138 | 22 | MDr | GP | Case Western | ||

| 30 | Costanza | 2000 | CaScr | MD Letter | acad | o | 1655 | 480 | MDa, MDr | GP, IM | University of Massachusetts Medical School | ||

| 31 | Cowan | 1992 | Immun, CaScr, Chol | Front | acad | o | 107 | 29 | MDa | GP | University of Illinois | ||

| 4 | Frame | 1994 | Immun, CaScr, Chol | Front | non-acad | o | 1666 | 12 | MDa, PA | GP | University of Rochester (NY) | ||

| 32 | Hambidge | 2004 | Immun | In Chart | non-acad | o | 2665 | NS | MDa, MDr | GP | Denver Health Medical Center | ||

| 33 | Myers | 2004 | CaScr | Letter | non-acad | o | 2992 | 470 | MDa | GP | 318 primary care practices Pennsylvania, and NJ | ||

| 34 | MacIntyre | 2003 | Immun | MD Letter | non-acad | i | 131 | NS | MDa | GP | The Royal Melbourne Hospital | ||

| 35 | Manfredi | 1998 | CaScr | Tagged | non-acad | o | 4554 | 87 | MDa | GP | Primary care practices in the Chicago area | ||

| 36 | Pierce | 1989 | CaScr | Tagged | non-acad | o | 276 | 7 | MDa | GP | Guy's and St Thomas's Hospitals | ||

| 37 | Pritchard | 1995 | CaScr | Tagged | non-acad | o | 383 | 12 | MDa | GP | University of Western Australia | ||

| 38 | Robie | 1988 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 356 | 41 | MDr | IM | Wake Forest University | ||

| 39 | Rodewald | 1999 | Immun | Tagged | non-acad | o | 2741 | NS | MDa | PED | Primary care practices in the Rochester area | ||

| 40 | Roetzheim | 2004 | CaScr | Tagged | non-acad | o | 1196 | NS | MDa | GP | Hillsboro County Clinics | ||

| 41 | Shevlin | 2002 | Immun | In Chart | acad | i | 534 | NS | MDr, MDa | Grady Memorial Hospital, Atlanta, Georgia | |||

| 42 | Simon | 2001 | CaScr | In Chart | non-acad | o | 1717 | NS | MDa | GP | Detroit Health Department Primary Care Clinics | ||

| 43 | Somkin | 1997 | CaScr | In Chart | non-acad | o | 7077 | NS | MDa | GP | Kaiser Permanente Medical Care Program of Northern California | ||

| 44 | Thompson | 2000 | CaScr | Patient List | non-acad | o | 1109 | 4 | MDa, MDr, LPN | IM | Veterans Affairs Medical Center Puget Sound, Seattle Washington | ||

| 45 | Barnett | 1983 | BP | Front | non-acad | o | 115 | 48 | MDa, RN | IM | Massachusetts General Hospital | ||

| 46 | Becker | 1989 | Immun, CaScr, GS | Front | acad | o | 563 | 80 | MDr | IM | University of Virginia | ||

| 47 | Burack | 1994 | CaScr | In chart | non-acad | o | 2725 | 25 | MDa | GP, IM, OBG | Wayne State University | ||

| 48 | Burack | 2003 | CaScr | In chart | non-acad | o | 2471 | 20 | MDa | GP, IM, OBG | HMO Practice sites in Detroit, Michigan | ||

| 49 | Burack | 1998 | CaScr | In chart | non-acad | o | 1471 | 20 | MDa | GP, IM, OBG | HMO Practice sites in Detroit, Michigan | ||

| 50 | Burack | 1997 | CaScr | In chart | non-acad | o | 2890 | 25 | MDa | GP, IM, OBG | Wayne State University | ||

| 51 | Buschbaum | 1993 | Alcohol | Front | acad | o | 214 | 83 | MDr | GP | Medical College of Virginia | ||

| 52 | Chambers | 1989 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 1262 | 30 | MDr, MDa | GP | Thomas Jefferson University | ||

| 53 | Chambers | 1991 | Immun | Front | acad | o | 686 | 30 | MDr, MDa | GP | Thomas Jefferson University | ||

| 54 | Cummings | 1989 | NoSmok | Front | non-acad | o | 916 | 44 | MDa | GP, IM | University of California, San Francisco | ||

| 55 | Daley | 2004 | Immun | Front | acad | o | 420 | NS | MDa, MDr | PED | The Children's Hospital, Denver, CO | ||

| 56 | Headrick | 1992 | Chol | Front | acad | o | 240 | 33 | MDr | IM | Case Western | ||

| 57 | Landis | 1992 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 57 | 24 | MDa, MDr | GP | Mt Area Health Education Center | ||

| 58 | Litzelman | 1993 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 5407 | 176 | MDr, MDa | IM | Regenstrief | ||

| 59 | Lobach | 1994 | DiabM | Front | acad | o | 359 | 58 | MDr, MDa, PA, NP | GP | Duke Family Medicine Center | ||

| 25 | McDonald | 1976 | BP, Chol, HgB, DiabM | Front | acad | o | 189 | 9 | MDr | IM | Regenstrief | ||

| 60 | McDonald | 1976 | BP, DiabM, CC | Front | acad | o | 301 | 63 | MDa, MDr, RN | IM | Regenstrief | ||

| 61 | McDonald | 1984 | Immun, CaScr, HgB, TB | Front | acad | o | 775 | 115 | MDr, MDa | IM | Regenstrief | ||

| 62 | McDowell | 1989 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 789 | 32 | MDa, MDr, RN | GP | University of Ottawa | ||

| 63 | McDowell | 1989 | BP | Front | acad | o | 2803 | 32 | MDa, MDr, RN | GP | University of Ottawa | ||

| 64 | McPhee | 1989 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 1936 | 62 | MDr | IM | University of California, San Francisco | ||

| 65 | Morgan | 1978 | Prenatal care | Front | non-acad | o | 279 | 5 | MDa/RN teams | OBG | Massachusetts General Hospital | ||

| 66 | Nilasena | 1995 | DiabM | Front | acad | o | 164 | 35 | MDr | IM | Salt Lake Veterans Affairs Hospital, University of Utah | ||

| 67 | Ornstein | 1991 | Immun, CaScr, Chol | Front | acad | o | 7397 | 49 | MDr, MDa | GP | Medical University of South Carolina | ||

| 68 | Rhew | 1999 | Immun | Front | non-acad | i | 3502 | NS | RN, MDa | GP | West Los Angeles VA General Medicine ambulatory clinic | ||

| 26 | Rosser | 1991 | NoSmok | Front | acad | o | 5883 | 36 | MDa, MDr | GP | University of Toronto/University of Ottawa | ||

| 69 | Rosser | 1992 | Immun | Front | acad | o | 5242 | 32 | MDr, MDa, RN | GP | University of Toronto/University of Ottawa | ||

| 70 | Rossi | 1997 | BP | Front | non-acad | o | 719 | 71 | MDa, NP, MDr | IM | Veterans Affairs Medical Center Puget Sound, Seattle Washington | ||

| 71 | Shaw | 2000 | Immun | Front | acad | o | 595 | 52 | MDr | PED | Children's Hospital, Boston | ||

| 72 | Soljak | 1987 | Immun | Patient List | non-acad | o | 2988 | 40 | MDa | GP | New Zealand | ||

| 73 | Taylor | 1999 | CaScr | Front | acad | o | 314 | 49 | MDr, MDa | University of Washington, Seattle | |||

| 74 | Tierney | 1986 | Immun, CaScr | In chart | acad | o | 6045 | 138 | MDr | GP | Regenstrief | ||

| 75 | Turner | 1990 | Immun, CaScr | Front | acad | o | 423 | 24 | MDr | IM | East Carolina University | ||

| 76 | Williams | 1998 | CaScr | Front | non-acad | o | 5789 | 507 | MDr | GP | Primary Care Practices in the Southeast | ||

| 77 | Ansari | 2003 | CC | Display | non-acad | o | 169 | 301 | MDa, MDr, NP | IM, Card | San Francisco Veterans Affairs Medical Center | ||

| 78 | Demakis | 2000 | BP, DiabM, CC, NoSmok | Display | non-acad | o | 12989 | 275 | MDr | GP | Veterans Affairs Medical Centers (12) | ||

| 5 | Dexter | 2001 | Immun, Heparin, Aspirin | Display | acad | i | 6371 | 202 | MDa, MDr, RN | GP | Wishard Memorial Hospital | ||

| 79 | Dexter | 2004 | Immun | Display | acad | i | 3777 | 212 | MDa, MDr, RN | GP | Wishard Memorial Hospital | ||

| 80 | Eccles | 2002 | Angina | Display | non-acad | o | 4851 | NS | MDa | GP | North East England General Practices | ||

| 81 | Filippi | 2003 | Antiplatlet drugs for Diab | Display | non-acad | o | 15343 | 300 | MDa | GP | Italy | ||

| 82 | Murray | 2004 | BP | Display | acad | o | 712 | NS | MDr, MDa | Indiana University School of Medicine | |||

| 83 | Tape | 1993 | Immun, CaScr | Display | acad | o | 1809 | 49 | MDr, MDa | IM | University of Nebraska | ||

Care Measure: CaScr = Cancer Screening; Chol = Cholesterol Management; Immun = Immunizations; HgB = hemoglobin management; CC = Cardiac Care; NoSmok = Smoking Cessation; BP = Blood Pressure management; GS = Glaucoma Screening; TB = Tuberculosis testing; DiabM = Diabetes Management; Alcohol = Alcohol abuse counseling; NS = Not Specified Institution: acad = Academic, non-acad = Non-Academic Provider Type: MDa = Attending Physician; MDr = Resident Physicians; NP = Nurse Practitioner; PA = Physician Assistant; RN = registered nurse; LPN = Licensed Practical Nurse Specialty: IM = Internal Medicine; Card = Cardiology; OBG = Obstetrics/Gynecology; PED = Pediatrics; GP = General Practitioner Number: NS – not specified Setting: o – outpatient; i – inpatient

Number of Studies

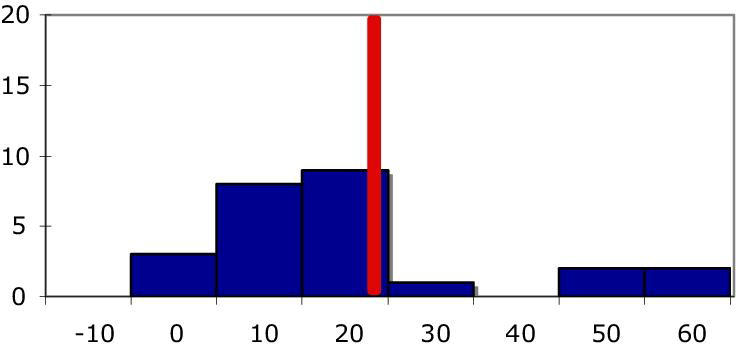

▶ displays the number and type of published studies, grouped by intervention's start year. The total number of computerized studies increased in the 2000–2004 period as compared to previous periods. From 2000–2004, nine studies applied paper-based interventions and seven computerized methods, while the number of computer-generated approaches declined to three reports.

Figure 2.

Preventive care reminder studies by intervention year. If the intervention's start year was not mentioned in the paper, the publication year − 1 was used to estimate an intervention year.

Interventions

The 61 studies examined a total of 264 preventive care interventions (maximum: 16). Nineteen (30%) studies evaluated three or more preventive measures, three (5%) examined two measures, and the remaining 39 (64%) assessed the impact of one measure. With a total of 110 studied interventions cancer screening (fecal occult blood testing, Papanicolaou smears, and mammograms) was the most frequent type of preventive care measure targeted by clinician reminders, followed by 64 interventions targeting vaccination.

Study Setting

The setting of 33 studies was an academic medical center, while the remaining 28 studies were conducted at non-academic hospitals and clinics. Five studies (9.6%) were performed in an inpatient setting, and the remaining 56 studies were in primary care clinics. In the inpatient setting the delivery of vaccinations were the most frequently studied reminders. The number of facilities in each study ranged from one (39 studies) to 1,655 hospitals or practice groups.

Prompting Clinicians

The methods of prompting clinicians are shown in ▶. Paper-based combined with computer-generated prompts were the most frequent clinician reminder approach and accounted for 34 studies (52%), followed by 19 paper-based (34%), and 8 computerized studies (13%). The three examined prompting approaches demonstrated a similar average increase in completing preventive care measures (▶). Paper-based reminders were applied in 80 interventions and resulted in a 14% average increase of preventive care compliance. Computer-generated reminders were implemented 136 times and had an average increase of 12%. Computerized reminders were employed in 48 interventions and resulted in a 13% average increase.

Table 2.

Table 2 Comparison of Primary Implementation Reminder Strategies

| Implementation strategy | Number of interventions (number of studies) | Average difference % (min, max) | Standard deviation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Paper-based | 80 (19) | 14 (−18 to 46) | 15 |

| Computer-generated | 136 (34) | 12 (−24 to 59) | 13 |

| Computerized | 48 (8) | 13 (−8 to 60) | 18 |

min = minimum; max = maximum

Prompting Methods

Of the 61 studies, 35 examined interventions that prompted only the clinician, 17 combined the clinician prompt with a patient reminder, and 9 studies examined the effects of prompting the clinician in one study group compared to reminding both the clinician and patient in the other study group. To remind patients, 15 mailed reminder letters, and eight studies notified patients via telephone. One study put up fliers and posters for the patients, one study visited patients at their homes to encourage vaccinations, and another study chose to educate patients on the importance of preventive care to encourage return visits. ▶ summarizes the effectiveness of clinician reminders only, and the combined approach of clinician and patient reminders. The average increase in preventive care procedure compliance was larger when prompting only the clinician (14%) compared to prompting both the clinician and the patient (10%) All but two of the studies prompted the physician before the patient appointment or at the time of order entry.

Table 3.

Table 3 Comparison of Clinician Only versus Combined Clinician–Patient Reminder Strategy

| Number of Interventions (Number of studies) ∗ | Average difference % (min, max) | Standard deviation | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinician only | 175 (44) | 14 (−18 to 60) | 16 |

| Clinician and patient | 105 (26) | 10 (−24 to 45) | 12 |

∗ The total number of interventions exceeds 264 because nine studies, evaluating various numbers of preventive care measures, compared the effect of a unique prompting technique in a clinician only group versus a combined clinician and patient group.

min = minimum, max = maximum

Average Effect

▶ displays the effect for measures that were examined by three studies or more. The average effects for measures examined by fewer than three studies ranged from 5% for prenatal care to 14% for alcohol abuse counseling. Prompting clinicians was most effective for smoking cessation (average: 23%), cardiac care (average: 20%), blood pressure screening (average: 16%), followed by vaccinations, diabetes management, and cholesterol (averages: 15%). Mammography reminders had the smallest average effect (10%).

Table 4.

Table 4 Effect of Prompting Clinicians for Preventive Care Procedures in Studies with Three or More Interventions

| Preventive care measure | Number of interventions (number of studies) | Average difference % ± sd (min, max) | Distribution | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vaccination | 64 (24) | 15 ± 14 [−15 to 50] |  |

|

| Fecal occult blood testing | 23 (16) | 12 ± 13 [−11 to 37] |  |

|

| Papanicolaou smear | 36 (20) | 12 ± 18 [−24 to 48] |  |

|

| Mammogram | 51 (23) | 10 ± 15 [−18 to 49] |  |

|

| Blood pressure | 22 (9) | 16 ± 19 [−8 to 59] |  |

|

| Cholesterol | 8 (6) | 15 ± 17 [−1 to 54] |  |

|

| Diabetes management | 27 (8) | 15 ± 10 [5 to 51] |  |

|

| Smoking cessation | 6 (3) | 23 ± 16 [3 to 44] |  |

|

| Cardiac care | 25 (4) | 20 ± 11 [−8 to 59] |  |

|

sd – standard deviation; min – minimum; max – maximum

Discussion

This systematic review summarized findings from 61 randomized controlled clinical trials that investigated the use of reminders to increase preventive care. Overall the prompting of clinicians continued to demonstrate a positive effect on the delivery of the 16 preventive care measures. In recent years, however, the clinician reminder strategies shifted from paper- to computer-based approaches.

Approaches that included a paper-based reminder component (paper-based or computer-generated) remained the most frequent implementation strategies (87%) and had a similar average effect as computerized reminders (14% versus 13%). In studies that included a paper-based component, a reminder sheet is attached on the front of the patient chart or tagged the paper chart in some form, indicating that the paper-record remains an important source of information and documentation instrument in many hospitals and clinics. To implement preventive care measures that require multiple steps during a visit, paper-based solutions may be easier integrated with the clinical workflow as compared to designing an information technology solution that depends on the provider's workstation use. Paper-based implementation strategies are effective when the number of targeted preventive care measures is limited. With an increasing number of recommended preventive care measures, a paper-based process may quickly encounter implementation challenges due to the limited scalability. However, clinical workflow processes that rely on paper charts may continue to favor paper-based implementation strategies.

Computer-generated reminders were most common (52%). In recent years, however, studies on the impact of computer-generated prompts tended to decrease, while computerized reminders increased. The recent increase in applying computerized reminder strategies suggests that clinical information systems are increasingly providing the infrastructure to implement preventive care reminders. Computerized reminder systems require an electronic medical record throughout the practice or hospital; however, only 23.9% of physicians in the US are using an electronic medical record system and 5% of hospitals are using computerized provider order entry systems. 84 Implementing preventive care measures using computerized reminders may overcome some of the paper-based implementation challenges. Although clinical information systems may provide an easier to scale and more sustainable infrastructure, they work best when clinicians can complete all steps involved in offering preventive care measures, avoiding the need to switch between paper-based and electronic means. For example, adoption of computerized reminders may be higher if systems apply computerized algorithms for eligibility screening, prompt clinicians at the right time, offer quick ordering processes, and facilitate documentation. Unfortunately the availability of such advanced information system environments remain the exception rather than the rule.

The prompts offered through the reminder systems were heterogeneous. Some preventive care procedures would be easier to perform during the visit, such as vaccinations or blood pressure screening, while others may require a separate appointment, such as mammograms. Cardiac care measures and discussion about smoking cessation were most frequently studied. These preventive measures can be performed during the same visit and are more likely to be completed.

One of the goals of any reminder system is providing the right information at the right time, to the right person, and in the right format. Each study did not report a comprehensive description of the environment and clinical workflow; thus, the effectiveness of a prompt may differ depending on the existing workflow and the effectiveness of a support infrastructure, such as additional personnel or the availability of information technology. Any of the approaches used to implement a reminder system should be examined in combination with the support infrastructure within which the reminder system is implemented.

The review has limitations that may influence the interpretation of the findings. First, it is conceivable that preventive care measures have become an accepted standard of care and further studies examining the effects of reminder strategies are not warranted any more. Many commercial health information systems provide the means of implementing reminders for preventive care measures. By prompting the clinicians, there may be behavioral changes that are not documented as outcomes and may therefore influence the preventive care procedure. Second, the possibility of publication bias exists in the studies we included, there may be less negative studies available. We have not excluded the possibility that publication bias may exist, however, we scored the study design of randomized controlled trials for inclusion in the review. It is possible that only including randomized controlled trials may have excluded some computerized systems which may have used historical controls instead of a concurrent control group. And our choice of using the average difference between baseline and intervention could potentially dilute findings related to specific patient populations. The average differences calculated in each study were not weighted by sample size of patients or clinicians. Lastly, this review only considered studies that involved clinicians in the process of offering patients preventive care measures. It is possible that other implementation strategies exist that do not involve the clinicians. The effectiveness of these approaches may differ in providing preventive care.

The average effect for all of the prompting methods was modest, the act of providing a prompt may modify behaviors that are not measured by the system. The clinicians may have been more aware of the preventive care procedures and may have considered them for more patients. By calculating the average effect by using the historical or concurrent control groups, we sought to make the groups as comparable as possible.

Each encounter with the healthcare system provides an opportunity to offer preventive care measures. However, keeping pace with the many different recommendations and various schedules remains a major challenge for busy clinicians that are expected to focus on a patient's current reason for the visit. Although clinical information systems can keep track of the various recommendations and schedules, they may lead to “prompting fatigue” as an unintended consequence. 85 An additional challenge is the fragmentation of health care information, 86 which requires providers to repeatedly verify the patient's eligibility for a preventive care measure, a time-consuming task even for one measure. As the healthcare sector applies more information technology, the exchange and sharing of electronic health record information among various providers may lessen that burden in the future.

Conclusion

In summary, this review showed an increase in applying computerized reminder systems for prompting clinicians to offer preventive care measures. As information technology reminder solutions may provide a better scalable and more sustainable model for the increasing burden of following different preventive care guidelines, we saw only a moderate increase in the number of randomized controlled trials looking at computerized reminder systems for preventive care.

Footnotes

JWD was supported by training grant from the National Library of Medicine (LM T15 007450-03). STR was supported by a National Library of Medicine grant (LM K22 08576-02).

References

- 1.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Tracking Healthy People 2010Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2000. November.

- 2.U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services2nd ed.. Washington, DC: Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; 1996.

- 3.Iglehart JK. The National Committee for Quality Assurance N Engl J Med 1996;335:995-999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Frame PS, Zimmer JG, Werth PL, Hall WJ, Eberly SW. Computer-based vs manual health maintenance tracking. A controlled trial. Arch Fam Med 1994;3:581-588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dexter PR, Perkins S, Overhage JM, Maharry K, Kohler RB, McDonald CJ. A computerized reminder system to increase the use of preventive care for hospitalized patients N Engl J Med 2001;345:965-970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Slobodkin D, Zielske PG, Kitlas JL, McDermott MF, Miller S, Rydman R. Demonstration of the feasibility of emergency department immunization against influenza and pneumococcus Ann Emerg Med 1998;32:537-543. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pham HH, Schrag D, Hargraves JL, Bach PB. Delivery of preventive services to older adults by primary care physicians JAMA 2005;294:473-481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McGlynn EA, Asch SM, Adams J, Keesey J, Hicks J, DeCristofaro A, et al. The quality of health care delivered to adults in the United States N Engl J Med 2003;348:2635-2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yarnall KS, Pollak KI, Ostbye T, Krause KM, Michener JL. Primary care: is there enough time for prevention? Am J Public Health 2003;93:635-641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination coverage among persons aged > or =65 years and persons aged 18-64 years with diabetes or asthma—United States, 2003 MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2004;53(43):1007-1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stone EG, Morton SC, Hulscher ME, Maglione MA, Roth EA, Grimshaw JM, et al. Interventions that increase use of adult immunization and cancer screening services: a meta-analysis Ann Intern Med 2002;136:641-651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson VJ, Szilagyi P. Patient reminder and patient recall systems to improve immunization rates Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005. CD003941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Hulscher ME, Wensing M, Grol RP, van Der Weijden T, van Weel C. Interventions to improve the delivery of preventive services in primary care Am J Public Health 1999;89:737-746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, Rosas-Arellano MP, Devereaux PJ, Beyene J, Sam J, Haynes RB. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review JAMA 2005;293:1223-1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shea S, DuMouchel W, Bahamonde L. A meta-analysis of 16 randomized controlled trials to evaluate computer-based clinical reminder systems for preventive care in the ambulatory setting J Am Med Inform Assoc 1996;3:399-409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tang PC, LaRosa MP, Newcomb C, Gorden SM. Measuring the effects of reminders for outpatient influenza immunizations at the point of clinical opportunity J Am Med Inform Assoc 1999;6:115-121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Balas EA, Weingarten S, Garb CT, Blumenthal D, Boren SA, Brown GD. Improving preventive care by prompting physicians Arch Intern Med 2000;160:301-308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schmittdiel J, McMenamin SB, Halpin HA, Gillies RR, Bodenheimer T, Shortell SM, et al. The use of patient and physician reminders for preventive services: results from a National Study of Physician Organizations Prev Med 2004;39:1000-1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. PUBMED [database on the Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Library of Medicine (US)http://www.pubmed.gov 2004. Accessed Jan 24, 2008.

- 20. OVID [database on the Internet]. New York (NY): Ovid Technologieshttp://www.ovid.com 2004. Accessed Jan 24, 2008.

- 21. ISI Web of Knowledge [database on the Internet]. Stamford (CT): The Thompson Corporationhttp://www.isiknowledge.com 2004. Accessed Jan 24, 2008.

- 22.Health Reference Center Academic [database on the Internet] Farmington Hills (MI): Gale Cengage Learninghttp://www.galegroup.com 2004. Accessed Jan 24, 2008.

- 23.Balas EA, Austin SM, Ewigman BG, Brown GD, Mitchell JA. Methods of randomized controlled clinical trials in health services research Med Care 1995;33:687-699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zar JH. Biostatistical Analysis3rd ed.. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice Hall; 1996.

- 25.McDonald CJ. Protocol-based computer reminders, the quality of care and the non-perfectability of man N Engl J Med 1976;295:1351-1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rosser WW, McDowell I, Newell C. Use of reminders for preventive procedures in family medicine CMAJ 1991;145:807-814. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bankhead C, Richards SH, Peters TJ, Sharp DJ, Hobbs FD, Brown J, et al. Improving attendance for breast screening among recent non-attenders: a randomised controlled trial of two interventions in primary care J Med Screen 2001;8:99-105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheney C, Ramsdell JW. Effect of medical records' checklists on implementation of periodic health measures Am J Med 1987;83:129-136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen DI, Littenberg B, Wetzel C, Neuhauser D. Improving physician compliance with preventive medicine guidelines Med Care 1982;20:1040-1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Costanza ME, Stoddard AM, Luckmann R, White MJ, Spitz Avrunin J, Clemow L. Promoting mammography: results of a randomized trial of telephone counseling and a medical practice intervention Am J Prev Med 2000;19:39-46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cowan JA, Heckerling PS, Parker JB. Effect of a fact sheet reminder on performance of the periodic health examination: a randomized controlled trial Am J Prev Med 1992;8:104-109. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hambidge SJ, Davidson AJ, Phibbs SL, Chandramouli V, Zerbe G, LeBaron CW, et al. Strategies to improve immunization rates and well-child care in a disadvantaged population: a cluster randomized controlled trial Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2004;158:162-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Myers RE, Turner B, Weinberg D, Hyslop T, Hauck WW, Brigham T, et al. Impact of a physician-oriented intervention on follow-up in colorectal cancer screening Prev Med 2004;38:375-381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacIntyre CR, Kainer MA, Brown GV. A randomised, clinical trial comparing the effectiveness of hospital and community-based reminder systems for increasing uptake of influenza and pneumococcal vaccine in hospitalised patients aged 65 years and over Gerontology 2003;49:33-40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manfredi C, Czaja R, Freels S, Trubitt M, Warnecke R, Lacey L. Prescribe for health. Improving cancer screening in physician practices serving low-income and minority populations. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:329-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pierce M, Lundy S, Palanisamy A, Winning S, King J. Prospective randomised controlled trial of methods of call and recall for cervical cytology screening BMJ 1989;299:160-162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pritchard DA, Straton JA, Hyndman J. Cervical screening in general practice Aust J Public Health 1995;19:167-172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Robie PW. Improving and sustaining outpatient cancer screening by medicine residents South Med J 1988;81:902-905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodewald LE, Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Barth R, Kraus R, Raubertas RF. A randomized study of tracking with outreach and provider prompting to improve immunization coverage and primary care Pediatrics 1999;103:31-38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Roetzheim RG, Christman LK, Jacobsen PB, Cantor AB, Schroeder J, Abdulla R, et al. A randomized controlled trial to increase cancer screening among attendees of community health centers Ann Fam Med 2004;2:294-300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shevlin JD, Summers-Bean C, Thomas D, Whitney CG, Todd D, Ray SM. A systematic approach for increasing pneumococcal vaccination rates at an inner-city public hospital Am J Prev Med 2002;22:92-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Simon MS, Gimotty PA, Moncrease A, Dews P, Burack RC. The effect of patient reminders on the use of screening mammography in an urban health department primary care setting Breast Cancer Res Treat 2001;65:63-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Somkin CP, Hiatt RA, Hurley LB, Gruskin E, Ackerson L, Larson P. The effect of patient and provider reminders on mammography and Papanicolaou smear screening in a large health maintenance organization Arch Intern Med 1997;157:1658-1664. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson NJ, Boyko EJ, Dominitz JA, Belcher DW, Chesebro BB, Stephens LM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a clinic-based support staff intervention to increase the rate of fecal occult blood test ordering Prev Med 2000;30:244-251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barnett GO, Winickoff RN, Morgan MM, Zielstorff RD. A computer-based monitoring system for follow-up of elevated blood pressure Med Care 1983;21:400-409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Becker DM, Gomez EB, Kaiser DL, Yoshihasi A, Hodge Jr RH. Improving preventive care at a medical clinic: how can the patient help? Am J Prev Med 1989;5:353-359. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Burack RC, Gimotty PA, George J, Stengle W, Warbasse L, Moncrease A. Promoting screening mammography in inner-city settings: a randomized controlled trial of computerized reminders as a component of a program to facilitate mammography Med Care 1994;32:609-624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Burack RC, Gimotty PA, Simon M, Moncrease A, Dews P. The effect of adding Pap smear information to a mammography reminder system in an HMO: results of randomized controlled trial Prev Med 2003;36:547-554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burack RC, Gimotty PA, George J, McBride S, Moncrease A, Simon MS, et al. How reminders given to patients and physicians affected pap smear use in a health maintenance organization: results of a randomized controlled trial Cancer 1998;82:2391-2400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burack RC, Gimotty PA. Promoting screening mammography in inner-city settings. The sustained effectiveness of computerized reminders in a randomized controlled trial. Med Care 1997;35:921-931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Buchsbaum DG, Buchanan RG, Lawton MJ, Elswick Jr. RK, Schnoll SH. A program of screening and prompting improves short-term physician counseling of dependent and nondependent harmful drinkers Arch Intern Med 1993;153:1573-1577. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chambers CV, Balaban DJ, Carlson BL, Ungemack JA, Grasberger DM. Microcomputer-generated reminders. Improving the compliance of primary care physicians with mammography screening guidelines. J Fam Pract 1989;29:273-280. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chambers CV, Balaban DJ, Carlson BL, Grasberger DM. The effect of microcomputer-generated reminders on influenza vaccination rates in a university-based family practice center J Am Board Fam Pract 1991;4:19-26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cummings SR, Richard RJ, Duncan CL, Hansen B, Vander Martin R, Gerbert B, et al. Training physicians about smoking cessation: a controlled trial in private practice J Gen Intern Med 1989;4:482-489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Daley MF, Steiner JF, Kempe A, Beaty BL, Pearson KA, Jones JS, et al. Quality improvement in immunization delivery following an unsuccessful immunization recall Ambul Pediatr 2004;4:217-223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Headrick LA, Speroff T, Pelecanos HI, Cebul RD. Efforts to improve compliance with the National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines. Results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med 1992;152:2490-2496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Landis SE, Hulkower SD, Pierson S. Enhancing adherence with mammography through patient letters and physician prompts. A pilot study. N C Med J 1992;53:575-578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Litzelman DK, Dittus RS, Miller ME, Tierney WM. Requiring physicians to respond to computerized reminders improves their compliance with preventive care protocols J Gen Intern Med 1993;8:311-317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lobach DF, Hammond WE. Development and evaluation of a Computer-Assisted Management Protocol (CAMP): improved compliance with care guidelines for diabetes mellitus Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1994:787-791. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Mc Donald CJ. Use of a computer to detect and respond to clinical events: its effect on clinician behavior Ann Intern Med 1976;84:162-167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McDonald CJ, Hui SL, Smith DM, Tierney WM, Cohen SJ, Weinberger M, et al. Reminders to physicians from an introspective computer medical record. A two-year randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 1984;100:130-138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.McDowell I, Newell C, Rosser W. A randomized trial of computerized reminders for blood pressure screening in primary care Med Care 1989;27:297-305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.McDowell I, Newell C, Rosser W. Computerized reminders to encourage cervical screening in family practice J Fam Pract 1989;28:420-424. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.McPhee SJ, Bird JA, Jenkins CN, Fordham D. Promoting cancer screening. A randomized, controlled trial of three interventions. Arch Intern Med 1989;149:1866-1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Morgan M, Studney DR, Barnett GO, Winickoff RN. Computerized concurrent review of prenatal care QRB Qual Rev Bull 1978;4:33-36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Nilasena DS, Lincoln MJ. A computer-generated reminder system improves physician compliance with diabetes preventive care guidelines Proc Annu Symp Comput Appl Med Care 1995:640-645. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 67.Ornstein SM, Garr DR, Jenkins RG, Rust PF, Arnon A. Computer-generated physician and patient reminders. Tools to improve population adherence to selected preventive services. J Fam Pract 1991;32:82-90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rhew DC, Glassman PA, Goetz MB. Improving pneumococcal vaccine rates. Nurse protocols versus clinical reminders. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:351-356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Rosser WW, Hutchison BG, McDowell I, Newell C. Use of reminders to increase compliance with tetanus booster vaccination CMAJ 1992;146:911-917. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rossi RA, Every NR. A computerized intervention to decrease the use of calcium channel blockers in hypertension J Gen Intern Med 1997;12:672-678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shaw JS, Samuels RC, Larusso EM, Bernstein HH. Impact of an encounter-based prompting system on resident vaccine administration performance and immunization knowledge Pediatrics 2000;105:978-983. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Soljak MA, Handford S. Early results from the Northland immunisation register N Z Med J 1987;100:244-246. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Taylor V, Thompson B, Lessler D, Yasui Y, Montano D, Johnson KM, et al. A clinic-based mammography intervention targeting inner-city women J Gen Intern Med 1999;14:104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tierney WM, Hui SL, McDonald CJ. Delayed feedback of physician performance versus immediate reminders to perform preventive care. Effects on physician compliance. Med Care 1986;24:659-666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Turner RC, Waivers LE, O'Brien K. The effect of patient-carried reminder cards on the performance of health maintenance measures Arch Intern Med 1990;150:645-647. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Williams RB, Boles M, Johnson RE. A patient-initiated system for preventive health care. A randomized trial in community-based primary care practices. Arch Fam Med 1998;7:338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ansari M, Shlipak MG, Heidenreich PA, Van Ostaeyen D, Pohl EC, Browner WS, et al. Improving guideline adherence: a randomized trial evaluating strategies to increase beta-blocker use in heart failure Circulation 2003;107:2799-2804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Demakis JG, Beauchamp C, Cull WL, Denwood R, Eisen SA, Lofgren R, et al. Improving residents' compliance with standards of ambulatory care: results from the VA Cooperative Study on Computerized Reminders JAMA 2000;284:1411-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Dexter PR, Perkins SM, Maharry KS, Jones K, McDonald CJ. Inpatient computer-based standing orders vs physician reminders to increase influenza and pneumococcal vaccination rates: a randomized trial JAMA 2004;292:2366-2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Eccles M, McColl E, Steen N, Rousseau N, Grimshaw J, Parkin D, et al. Effect of computerised evidence based guidelines on management of asthma and angina in adults in primary care: cluster randomised controlled trial BMJ 2002;325:941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Filippi A, Sabatini A, Badioli L, Samani F, Mazzaglia G, Catapano A, et al. Effects of an automated electronic reminder in changing the antiplatelet drug-prescribing behavior among Italian general practitioners in diabetic patients: an intervention trial Diabetes Care 2003;26:1497-1500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Murray MD, Harris LE, Overhage JM, Zhou XH, Eckert GJ, Smith FE, et al. Failure of computerized treatment suggestions to improve health outcomes of outpatients with uncomplicated hypertension: results of a randomized controlled trial Pharmacotherapy 2004;24:324-337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Tape TG, Campbell JR. Computerized medical records and preventive health care: success depends on many factors Am J Med 1993;94:619-625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Jha AK, Ferris TG, Donelan K, et al. How common are electronic health records in the United States?. A summary of the evidence. Health Aff (Millwood) 2006;25:w496-w507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Hsieh TC, Kuperman GJ, Jaggi T, et al. Characteristics and consequences of drug allergy alert overrides in a computerized physician order entry system J Am Med Inform Assoc 2004;11:482-491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Halamka J, Overhage JM, Ricciardi L, Rishel W, Shirky C, Diamond C. Exchanging health information: local distribution, national coordination. As more communities develop information-sharing networks, a coordinated approach is essential for linking these networks. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24(5):1170-1179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]