Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the efficacy and safety of an oral fluoropyrimidine derivative, S-1, in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Patients with pathologically confirmed advanced biliary tract cancer, a measurable lesion, and no history of radiotherapy or chemotherapy were enrolled. S-1 was administered orally (40 mg m−2 b.i.d.) for 28 days, followed by a 14-day rest period. A pharmacokinetic study was performed on day 1 in the initial eight patients. In all, 19 consecutive eligible patients were enrolled in the study between July 2000 and January 2002. The site of the primary tumour was the gallbladder (n=16), the extrahepatic bile ducts (n=2), and the ampulla of Vater (n=1). A median of two courses of treatment (range, 1–12) was administered. Four patients achieved a partial response, giving an overall response rate of 21.1%. The median time-to-progression and median overall survival period were 3.7 and 8.3 months, respectively. Although grade 3 anorexia and fatigue occurred in two patients each (10.5%), no grade 4 toxicities were observed. The pharmacokinetic parameters after a single oral administration of S-1 were similar to those of patients with other cancers. S-1 exhibits definite antitumour activity and is well tolerated in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer.

Keywords: S-1, phase II study, biliary tract cancer, chemotherapy, pharmacokinetics

The incidence of biliary tract cancer has been steadily increasing in Japan over the past several decades (Okusaka, 2002). Currently, biliary tract cancer is the sixth leading cause of death from cancer in Japan, with statistics from 2002 indicating a total of about 16 000 deaths from this disease. As a result of the lack of characteristic early symptoms, biliary tract cancers are often diagnosed at an advanced stage, and the prognosis of patients with advanced biliary tract cancer is dismal. Although systemic treatment is used for advanced disease, the impact of existing chemotherapy is virtually negligible. A large number of agents, including 5-fluorouracil (5-FU), mitomycin-C, and cisplatin, have been tested as single agents or in combination therapies without appreciable efficacy (Hejna et al, 1998; van Riel et al, 1999; Yee et al, 2002). Although recent clinical studies have suggested the potential activity of gemcitabine for the treatment of biliary tract cancer, producing response rates of 8 to 36% (Mezger et al, 1998; Raderer et al, 1999; Gallardo et al, 2001; Gebbia et al, 2001; Kubicka et al, 2001; Penz et al, 2001; Tsavaris et al, 2004), studies on a larger scale are needed to confirm its efficacy. In any case, to improve the prognosis of patients with biliary tract cancer, a clear need exists for new, effective chemotherapeutic agents.

S-1 is a novel orally administered drug that is a combination of tegafur (FT), 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine (CDHP), and oteracil potassium (Oxo) in a 1 : 0.4 : 1 molar concentration ratio (Shirasaka et al, 1996a). 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine is a competitive inhibitor of dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase, which is involved in the degradation of 5-FU, and acts to maintain efficacious concentrations of 5-FU in plasma and tumour tissues (Tatsumi et al, 1987). Oteracil potassium, a competitive inhibitor of orotate phosphoribosyltransferase, inhibits the phosphorylation of 5-FU in the gastrointestinal tract, reducing the serious gastrointestinal toxicity associated with 5-FU (Shirasaka et al, 1993). S-1 therapy in athymic nude rats was associated with the retention of a higher and more prolonged concentration of 5-FU in plasma and tumour tissues, when compared with UFT (Shirasaka et al, 1996b). The antitumour effect of S-1 has been already demonstrated in a variety of solid tumours: the response rates for advanced gastric cancer (Sakata et al, 1998; Koizumi et al, 2000), colorectal cancer (Ohtsu et al, 2000), non-small-cell lung cancer (Kawahara et al, 2001), and head and neck cancer (Inuyama et al, 2001) in the late phase II studies conducted in Japan were 44–49, 35, 22, and 29%, respectively. In addition, a recent early phase II study for advanced pancreatic cancer demonstrated a response rate of 21% in 19 patients (Okada et al, 2002). The efficacy of S-1 for the treatment of gastrointestinal cancer has also been reported in European patients: the response rates for advanced gastric cancer (Chollet et al, 2003) and colorectal cancer (Van den Brande et al, 2003) were 32 and 24%, respectively. However, no previous reports have described the efficacy and safety of S-1 for the treatment of biliary tract cancer. Consequently, the present early phase II study was conducted to evaluate the efficacy and safety of S-1 in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Patients

Patients were required to meet the following eligibility criteria: histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced biliary tract cancer; at least one measurable lesion; no history of prior antitumour treatment except resection; a Karnofsky performance status (KPS) of 80–100 points; age of 20–74 years; an estimated life expectancy of at least 2 months; adequate organ function, defined as a white blood cell count of 4000–12 000 mm−3, a platelet count ⩾100 000 mm−3, a haemoglobin level ⩾10.0 g/dl, a normal serum creatinine level, a serum total bilirubin level ⩽3 times the upper limit of normal, an aspartate aminotransferase and alanine aminotransferase level ⩽2.5 times the upper limits of normal; and written informed consent. Patients who had obstructive jaundice were considered eligible if their bilirubin level could be reduced to within 3 times the upper limit of normal after biliary drainage. The exclusion criteria were as follows: a history of drug hypersensitivity; severe complications, such as infection, heart disease, and renal disease; symptomatic metastasis of the central nervous system; active concomitant malignancy; marked pleural effusion or ascites; watery diarrhoea; and pregnancy or lactation. This study was approved by the institutional review board at the National Cancer Center and conducted in accordance with the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of Japan.

Treatments

S-1 was administered orally at a dose of 40 mg m−2 twice daily after breakfast and dinner. Three initial doses were established according to the body surface area (BSA) as follows: BSA <1.25 m2, 80 mg day−1; 1.25 m2⩽BSA<1.50 m2, 100 mg day−1; and 1.50 m2⩽BSA, 120 mg day−1. S-1 was administered at the respective dose for 28 days, followed by a 14-day rest period; this treatment course was repeated until the occurrence of disease progression, unacceptable toxicities, or the patient's refusal to continue. When a grade 3 or greater haematologic or grade 2 or greater nonhaeamatologic toxicity occurred, the temporary interruption of the S-1 administrations was allowed until the toxicity subsided to grade 1 or less. If the daily dose of S-1 was considered to be intolerable, the retreatment dose was reduced by 20 mg day−1 (minimum dose, 80 mg day−1). If no toxicity occurred, the rest period shortened to 7 days was allowed. If a rest period of more than 28 days was required because of toxicity, the patient was withdrawn from the study. Patients were not allowed to receive concomitant radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or hormonal therapy during the study. Patients maintained a daily journal to record their intake of S-1 and any signs or symptoms that they experienced. S-1 was provided by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd (Tokyo, Japan).

Response and toxicity evaluation

The response after each course was assessed according to the Japan Society for Cancer Therapy Criteria (Japan Society for Cancer Therapy, 1993), which is similar to the World Health Organization Criteria. Briefly, a complete response (CR) was defined as the disappearance of all clinical evidence of the tumour for a minimum of 4 weeks. A partial response (PR) was defined as a 50% or greater reduction in the sum of the products of two perpendicular diameters of all measurable lesions for a minimum of 4 weeks. No change (NC) was defined as a reduction of less than 50% or a less than 25% increase in the sum of the products of two perpendicular diameters of all lesions for a minimum of 4 weeks. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as an increase of 25% or more in the sum of the products of two perpendicular diameters of all lesions, the appearance of any new lesion, or a deterioration in the clinical status that was consistent with disease progression. Primary bile duct lesions were not considered to be measurable lesions because the dimensions of such lesions are difficult to measure accurately.

The response duration was calculated from the day of the first sign of a response until disease progression; time-to-progression (TTP) was calculated from the date of study entry until documented disease progression; and overall survival time was calculated from the date of study entry to the date of death or the last follow-up. The median probability of the survival period and the median TTP were estimated using the Kaplan–Meier method. Compliance was calculated for all treatment courses using the ratio of the total dose actually administered to the scheduled dose.

Physical examinations, complete blood cell counts, biochemistry tests, and urinalyses were performed at least biweekly. Adverse events were evaluated according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0. Objective responses and adverse events were confirmed by an external review committee.

Analysis was to be performed when 19 patients were enrolled. In this study, the threshold rate was defined as 5% and the expected rate was set as 15%. If the lower limit of the 90% confidence interval exceeded the 5% threshold (objective response in four or more of the 19 patients), S-1 was judged to be effective and we would proceed to the next large-scale study. If the upper limit of the 90% confidence interval did not exceed the expected rate of 15% (no objective response in the 19 patients), S-1 was judged to be ineffective and the study was to be ended. If response was confirmed in 1–3 of the 19 patients, whether to proceed to the next study or not was judged based on the safety and survival data from the present study.

Pharmacokinetics

A pharmacokinetic study was performed in the first eight patients enrolled in the study. Blood (5 ml) was collected before and 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, and 12 h after the administration of S-1 on day 1 of the first course. The plasma was then separated by centrifugation and stored at −20°C until analysis. Plasma concentrations of FT were quantified using high-performance liquid chromatography with UV detection, and the concentrations of 5-FU, CDHP, and Oxo were quantified using gas chromatography-negative ion chemical ionisation mass spectrometry, as reported previously (Matsushima et al, 1997).

Pharmacokinetic parameters, including the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax, ng ml−1), time to reach Cmax (Tmax, h), area under the concentration vs time curve for zero to infinity (AUC0–∞, ng h ml−1), and the elimination half-life (T1/2, h) were calculated using a noncompartment model and Win-Nonlin software, Version 3.1 (Pharsight, Apex, NC, USA).

RESULTS

Patients

Nineteen consecutive eligible patients with advanced biliary tract cancer were enrolled in the study between July 2000 and January 2002 at the National Cancer Center Hospital, Tokyo, Japan. The patient characteristics are summarised in Table 1 . Before the start of the study, six patients had received surgical resection and seven patients had undergone percutaneous or endoscopic biliary drainage for obstructive jaundice. Of the 19 patients, 17 had metastatic disease at the time of their enrollment in the study, while two patients were diagnosed as having locally advanced disease. The liver was the most common site of metastases (14 patients), followed by the distant lymph nodes (11 patients) and the lungs (three patients).

Table 1. Patient characteristics (n=19).

| Characteristics | No. of patients (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 12 (63.2) | |

| Female | 7 (36.8) | |

| Median age (years) (range) | 59 (44–71) | |

| Karnofsky performance status, points | ||

| 100 | 8 (42.1) | |

| 90 | 10 (52.6) | |

| 80 | 1 (5.3) | |

| Median body surface area (m2) (range) | 1.56 (1.37–1.83) | |

| Median first dose (mg m−2 day−1) (range) | 72.9 (65.8–78.6) | |

| History of surgical resection | 6 (31.6) | |

| Primary tumour site | ||

| Gallbladder | 16 (84.2) | |

| Extrahepatic bile ducts | 2 (10.5) | |

| Ampulla of Vater | 1 (5.3) | |

| Median CEA (ng ml−1) (range) | 6.8 (1–737) | |

| Median CA 19-9 (U ml−1) (range) | 103 (1–48,160) |

Treatments

In all, 19 patients were given a total of 63 courses of chemotherapy, with a median of two courses each (range, 1–12). The initial administered dose of S-1 was 100 mg day−1 in seven patients and 120 mg day−1 in 12 patients. Dose reduction was required in one patient because of grade 2 diarrhoea after the third course of treatment. The reasons for treatment discontinuation were as follows: disease progression (16 patients), grade 3 diarrhoea and grade 3 stomatitis (one patient), prolonged grade 2 nausea (one patient), and patient's request for transference to another hospital (one patient). Except for two patients, in whom treatment was abandoned because of toxicities, all the patients were treated as outpatients. The overall compliance rate was 94.3%.

Response and survival

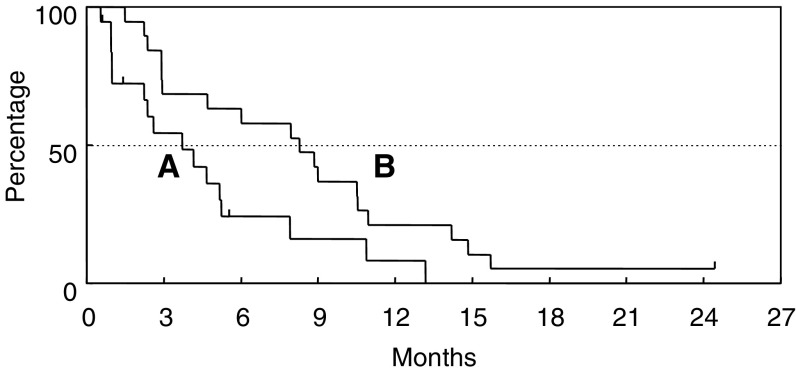

Of the 19 patients, none of the patients showed a CR but four patients achieved a PR, giving an overall response rate of 21.1% (95% confidence interval, 6.1–45.6%) (Table 2 ). The median response duration was 6.7 months (range, 2.8–10.0 months). Nine patients showed NC and five patients had PD. The tumour response could not be evaluated in one patient because the patient was transferred to another hospital, for personal reasons, prior to the response evaluation. At the time of analysis, 18 of the 19 patients had died because of disease progression. The median TTP was 3.7 months, and the overall median survival time was 8.3 months, with a 1-year survival rate of 21.1% (Figure 1).

Table 2. Response results (n=19).

| Total | CR | PR | NC | PD | NE | Response rate (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 19 | 0 | 4 | 9 | 5 | 1 | 21.1 |

| Primary tumour site | |||||||

| Gallbladder | 16 | 0 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 1 | 18.8 |

| Extrahepatic bile ducts | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ampulla of Vater | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 100.0 |

CR=Complete response; PR=partial response; NC=no change; PD=progressive disease; NE=not evaluable.

Figure 1.

Time to progression (A) and overall survival time (B).

Toxicity

All 19 patients were assessed for toxicities that are listed in Table 3 . Treatment was generally well tolerated throughout the study. Although haematologic and gastrointestinal toxicities were common, most of the toxicities were mild and transient. Grade 3 anorexia and fatigue occurred in two patients each (10.5%), and grade 3 anaemia, neutropenia, stomatitis, nausea, diarrhoea, and fever occurred in one patient each (5.3%). No signs of cumulative toxicity were noted. Of the 17 patients who were treated as outpatients, one patient required hospitalisation because of grade 3 nausea, anorexia, and fatigue during the middle of the first course of treatment. Although one patient died within 8 weeks of study enrollment because of rapid disease progression, no treatment-related deaths were observed.

Table 3. Treatment-related adverse events (n=19): worst grade reported during treatment period.

|

Gradea |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Toxicity | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | Grade 1–4 (%) | Grade 3–4 (%) |

| Haematologic | ||||||

| Leukopenia | 5 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 42.1 | 0 |

| Neutropenia | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 36.8 | 5.3 |

| Anaemia | 3 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 42.1 | 5.3 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 10.5 | 0 |

| Nonhaematologic | ||||||

| Nausea | 4 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 36.8 | 5.3 |

| Vomiting | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 21.1 | 0 |

| Anorexia | 3 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 26.3 | 10.5 |

| Stomatitis | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 21.1 | 5.3 |

| Diarrhoea | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 26.3 | 5.3 |

| Total bilirubin | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 10.5 | 0 |

| ALT | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 31.6 | 0 |

| AST | 4 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 31.6 | 0 |

| Fatigue | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 10.5 | 10.5 |

| Fever | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 5.3 | 5.3 |

| Rash | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5.3 | 0 |

| Pigmentation changes | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15.8 | 0 |

AST=aspartate aminotransferase; ALT=alanine aminotransferase.

NCI Common Toxicity Criteria, version 2.0.

Pharmacokinetics

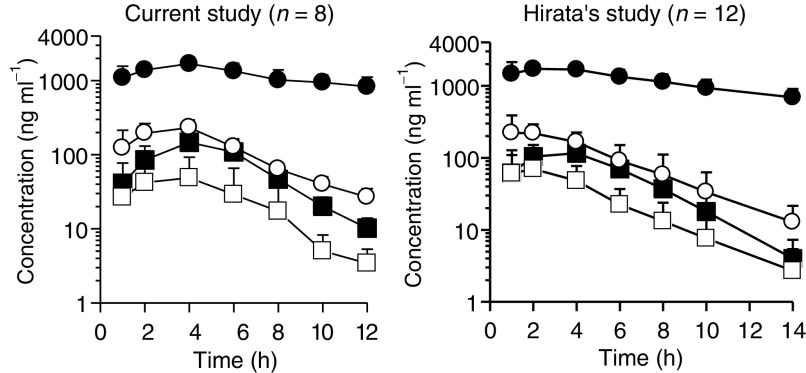

Table 4 and Figure 2 show the results of the pharmacokinetic study for S-1 in the current study. The pharmacokinetic parameters for S-1 in other cancers, as reported by Hirata et al (1999) are also shown in Table 4 and Figure 2 for reference. Hirata et al investigated the pharmacokinetic parameters after the single administration of S-1 at a dose of 40 mg m−2 in 12 Japanese patients with gastric, colorectal, and breast cancer. The parameters of 5-FU in both studies were similar, and no large differences in the parameters of other compounds, including CDHP, were seen.

Table 4. Pharmacokinetic parameters after single administration of S-1 at a dose of 40 mg m−2.

| Compound | Parameter | Current study (n=8) | Hirata's study (n=12) |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT | Cmax (ng ml−1) | 1721.6±400.4 | 1971.0±269.0 |

| Tmax (h) | 3.6±1.1 | 2.4±1.2 | |

| AUC (ng h ml−1) | 24643.0±7915.0a | 28216.9±7771.4b | |

| T1/2 (h) | 8.2±2.0 | 13.1±3.1 | |

| 5-FU | Cmax (ng ml−1) | 146.9±62.1 | 128.5±41.5 |

| Tmax (h) | 4.0±0.0 | 3.5±1.7 | |

| AUC (ng h ml−1) | 799.8±285.3a | 723.9±272.7c | |

| T1/2 (h) | 1.9±0.3 | 1.9±0.4 | |

| CDHP | Cmax (ng ml−1) | 245.3±64.9 | 284.6±116.6 |

| Tmax (h) | 3.3±1.0 | 2.1±1.2 | |

| AUC (ng h ml−1) | 1472.6±381.6a | 1372.2±573.7b | |

| T1/2 (h) | 3.2±0.7 | 3.0±0.5 | |

| Oxo | Cmax (ng ml−1) | 55.3±48.4 | 78.0±58.2 |

| Tmax (h) | 3.3±1.0 | 2.3±1.1 | |

| AUC (ng h ml−1) | 230.6±140.2a | 365.7±248.6d | |

| T1/2 (h) | 2.8±0.6 | 3.0±1.4 |

Parameters are represented as mean±s.d.

AUC0–∞.

AUC0–48.

AUC0–14.

AUC0–24.

FT=tegafur; 5-FU=5-fluorouracil; CDHP=5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine; Oxo=oteracil potassium.

Figure 2.

Plasma concentration–time profiles of FT (•), 5-FU (▪), CDHP (○), and Oxo (□) after administration of S-1. The values are expressed as the mean±s.d.

DISCUSSION

Although most patients with biliary tract cancer have an unresectable disease at the time of diagnosis, no standard chemotherapies have been established for this disease (Hejna et al, 1998; van Riel et al, 1999; Okusaka, 2002; Yee et al, 2002). Since biliary tract cancer is an uncommon disease, studies of chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer are relatively few, and the number of included patients is generally small. In addition, the response rates and survival times described in published studies are difficult to compare because most studies contain patients with heterogeneous tumour groups, such as intrahepatic or extrahepatic bile duct cancer and gallbladder cancer. 5-fluorouracil has been the most commonly studied drug for this disease, although the antitumour effect of single-agent 5-FU is limited, with a response rate of less than 20%. Although the combined use of 5-FU with other agents, such as leucovorin, mitomycin C, or cisplatin, often produces a response rate of over 20% (Polyzos et al, 1996; Ducreux et al, 1998; Taïeb et al, 2002), the toxicities also become greater; whether combination therapies contribute to prolonged survival remains uncertain. In recent small-scale studies, gemcitabine has shown relatively good response rates, ranging from 8 to 36%, for biliary tract cancer (Mezger et al, 1998; Raderer et al, 1999; Gallardo et al, 2001; Gebbia et al, 2001; Kubicka et al, 2001; Penz et al, 2001; Tsavaris et al, 2004), but large-scale studies are needed to confirm its efficacy. Therefore, the development of new effective chemotherapeutic agents is urgently needed to improve survival in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers.

A novel orally administered drug, S-1, has been developed based on the biochemical modulations by CDHP, a dihydropyrimidine dehydrogenase inhibitor, and Oxo, a protector against 5-FU-induced gastrointestinal toxicity; S-1 has exhibited significant antitumour effects on various solid cancers (Sakata et al, 1998; Koizumi et al, 2000; Ohtsu et al, 2000; Inuyama et al, 2001; Kawahara et al, 2001; Chollet et al, 2003; Van den Brande et al, 2003). Since the drug is available in oral form, S-1 has a potential advantage, as far as patient convenience is concerned, especially in terms of quality-of-life. This consideration is very important for biliary tract cancer patients because their remaining lifespan is generally short. Consequently, the efficacy of S-1 for the treatment of biliary tract cancer was examined.

In the current study, S-1 produced a good response rate of 21.1%, which is superior to those obtained with other single agents, including 5-FU, mitomycin C, and cisplatin (Table 5 ), suggesting an antitumour effect of S-1 on biliary tract cancer. In this study, patients with gallbladder cancer accounted for three of the four responders; however, the efficacy of S-1 for each primary tumour site cannot be accurately assessed because of the small number of subjects analysed.

Table 5. Recent studies of single-agent chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer.

|

No. of patients |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Author | Regimen | Total | Gallbladder Ca. | Response rate (%) | MST (months) |

| Takada et al (1994) | 5-FU | 18 | 10 | 0 | NA |

| Taal et al (1993) | Mitomycin C | 30 | 13 | 10 | 4.5 |

| Okada et al (1994) | Cisplatin | 13 | 6 | 8 | 5.5 |

| Jones et al (1996) | Paclitaxel | 15 | 4 | 0 | NA |

| Pazdur et al (1999) | Docetaxel | 17 | 0 | 0 | NA |

| Papakostas et al (2001) | Docetaxel | 25 | 16 | 20 | 8 |

| Sanz-Altamira et al (2001) | Irinotecan | 25 | 10 | 8 | 10 |

| Mezger et al (1998) | Gemcitabine | 13 | 4 | 8 | NA |

| Raderer et al (1999) | Gemcitabine | 19 | 5 | 16 | 6.5 |

| Penz et al (2001) | Gemcitabinea | 32 | 10 | 22 | 11.5 |

| Kubicka et al (2001) | Gemcitabine | 23 | 0 | 30 | 9.3 |

| Gallardo et al (2001) | Gemcitabine | 26 | 26 | 36 | 7 |

| Gebbia et al (2001) | Gemcitabine | 18 | 12 | 22 | 8 |

| Tsavaris et al (2004) | Gemcitabine | 30 | 14 | 30 | 14 |

| Current study | S-1 | 19 | 16 | 21 | 8.3 |

5-FU: 5-fluorouracil; MST: median survival time; NA: not available.

Biweekly.

Since patients with biliary tract cancer tend to suffer various tumour-related complications, such as cholangitis and impaired liver function, enhanced chemotherapy-related toxicities, including neutropenic sepsis, are a concern. However, S-1 was well tolerated in the present study, and no grade 4 toxicities occurred. Haematological toxicities were acceptable and similar to the results of clinical studies examining S-1 for the treatment of other cancers in Japan. Gastrointestinal toxicities were also well tolerated, as in the other Japanese studies, although strong gastrointestinal toxicities, particularly severe diarrhoea, have been reported in Western countries (van Groeningen et al, 2000; Cohen et al, 2002; Chollet et al, 2003; Van den Brande et al, 2003). The difference in toxicities between the Japanese and Western studies remains unexplained, although the conversion of FT to 5-FU seems to occur more slowly in Japanese patients than in patients from other ethnic groups (Comets et al, 2003). A pharmacokinetic study suggested that the pharmacokinetic parameters of S-1 were similar in patients with biliary tract cancer and in patients with other cancers in Japan.

Since no serious adverse events occurred in this study, most of the patients were treated as outpatients, enabling a relatively good quality-of-life. The S-1 compliance rate of the patients was very good (94.3%), with only one patient requiring a dose reduction and only two patients discontinuing S-1 because of toxicity. In view of the favourable toxicity profile, its evaluation in combination with other agents might be of particular interest to improve therapeutic results. Combination therapy with S-1 and cisplatin has already been conducted for gastric cancer, and an excellent response rate of 76% was reported in a phase II study (Ohtsu et al, 2001).

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that S-1 is a safe and active agent for the treatment of patients with biliary tract cancer. Further investigations of this agent are warranted in this population of patients with a poor prognosis.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs S Okada, M Kurihara, S Matsuno, O Ishikawa, and T Taguchi for their kind advice; Drs H Saisho, N Moriyama, and W Koizumi for performing the extramural review; and Misses T Tomizawa and Y Kawaguchi for their support. We also thank Messrs T Tahara, T Tsuruda, A Fukushima, M Noguchi, and Dr R Azuma for their assistance with the data management and Mr K Kuwata for performing the pharmacokinetic analysis. This work was supported by Taiho Pharmaceutical Co. Ltd, Tokyo, Japan.

References

- Chollet P, Schoffski P, Weigang-Kohler K, Schellens JH, Cure H, Pavlidis N, Grunwald V, De Boer R, Wanders J, Fumoleau P (2003) Phase II trial with S-1 in chemotherapy-naive patients with gastric cancer. A trial performed by the EORTC Early Clinical Studies Group (ECSG). Eur J Cancer 39: 1264–1270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SJ, Leichman CG, Yeslow G, Beard M, Proefrock A, Roedig B, Damle B, Letrent SP, DeCillis AP, Meropol NJ (2002) Phase I and pharmacokinetic study of once daily oral administration of S-1 in patients with advanced cancer. Clin Cancer Res 8: 2116–2122 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comets E, Ikeda K, Hoff P, Fumoleau P, Wanders J, Tanigawara Y (2003) Comparison of the pharmacokinetics of S-1, an oral anticancer agent, in Western and Japanese patients. J Pharmacokinet Pharmacodyn 30: 257–283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ducreux M, Rougier P, Fandi A, Clavero-Fabri MC, Villing AL, Fassone F, Fandi L, Zarba J, Armand JP (1998) Effective treatment of advanced biliary tract carcinoma using 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion with cisplatin. Ann Oncol 9: 653–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo JO, Rubio B, Fodor M, Orlandi L, Yanez M, Gamargo C, Ahumada M (2001) A phase II study of gemcitabine in gallbladder carcinoma. Ann Oncol 12: 1403–1406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebbia V, Giuliani F, Maiello E, Colucci G, Verderame F, Borsellino N, Mauceri G, Caruso M, Tirrito ML, Valdesi M (2001) Treatment of inoperable and/or metastatic biliary tree carcinomas with single-agent gemcitabine or in combination with levofolinic acid and infusional fluorouracil: results of a multicenter phase II study. J Clin Oncol 19: 4089–4091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hejna M, Pruckmayer M, Raderer M (1998) The role of chemotherapy and radiation in the management of biliary cancer: a review of the literature. Eur J Cancer 34: 977–986 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata K, Horikoshi N, Aiba K, Okazaki M, Denno R, Sasaki K, Nakano Y, Ishizuka H, Yamada Y, Uno S, Taguchi T, Shirasaka T (1999) Pharmacokinetic study of S-1, a novel oral fluorouracil antitumor drug. Clin Cancer Res 5: 2000–2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inuyama Y, Kida A, Tsukuda M, Kohno N, Satake B (2001) Late phase II study of S-1 in patients with advanced head and neck cancer. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho 28: 1381–1390 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japan Society for Cancer Therapy (1993) Criteria for the evaluation of the clinical effects of solid cancer chemotherapy. J Jpn Soc Cancer Ther 28: 101–130 [Google Scholar]

- Jones Jr DV, Lozano R, Hoque A, Markowitz A, Patt YZ (1996) Phase II study of paclitaxel therapy for unresectable biliary tree carcinomas. J Clin Oncol 14: 2306–2310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawahara M, Furuse K, Segawa Y, Yoshimori K, Matsui K, Kudoh S, Hasegawa K, Niitani H (2001) Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral fluorouracil, in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 85: 939–943 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koizumi W, Kurihara M, Nakano S, Hasegawa K (2000) Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral derivative of 5-fluorouracil, in advanced gastric cancer. For the S-1 Cooperative Gastric Cancer Study Group. Oncology 58: 191–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicka S, Rudolph KL, Tietze MK, Lorenz M, Manns M (2001) Phase II study of systemic gemcitabine chemotherapy for advanced unresectable hepatobiliary carcinomas. Hepatogastroenterology 48: 783–789 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsushima E, Yoshida K, Kitamura R (1997) Determination of S-1 (combined drug of tegafur, 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine and potassium oxonate) and 5-fluorouracil in human plasma and urine using high-performance liquid chromatography and gas chromatography-negative ion chemical ionization mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl 691: 95–104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mezger J, Sauerbruch T, Ko Y, Wolter H, Funk C, Glasmacher A (1998) Phase II study of gemcitabine in gallbladder and biliary tract carcinomas. Onkologie 21: 232–234 [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu A, Baba H, Sakata Y, Mitachi Y, Horikoshi N, Sugimachi K, Taguchi T (2000) Phase II study of S-1, a novel oral fluorophyrimidine derivative, in patients with metastatic colorectal carcinoma. S-1 Cooperative Colorectal Carcinoma Study Group. Br J Cancer 83: 141–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu A, Boku N, Nagashima F, Koizumi W, Tanabe S, Saigenji K, Muro K, Matsumura Y, Shirao K (2001) A phase I/II study of S-1 plus cisplatin (CDDP) in patients (pts) with advanced gastric cancer (AGC). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 20: 656 [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Ishii H, Nose H, Yoshimori M, Okusaka T, Aoki K, Iwasaki M, Furuse J, Yoshino M (1994) A phase II study of cisplatin in patients with biliary tract carcinoma. Oncology 51: 515–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada S, Okusaka T, Ueno H, Ikeda M, Kuriyama H, Saisho T, Morizane C (2002) A phase II and pharmacokinetic trial of S-1 in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer (APC). Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 22: 171a [Google Scholar]

- Okusaka T (2002) Chemotherapy for biliary tract cancer in Japan. Semin Oncol 29: 51–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papakostas P, Kouroussis C, Androulakis N, Samelis G, Aravantinos G, Kalbakis K, Sarra E, Souglakos J, Kakolyris S, Georgoulias V (2001) First-line chemotherapy with docetaxel for unresectable or metastatic carcinoma of the biliary tract. A multicentre phase II study. Eur J Cancer 37: 1833–1838 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pazdur R, Royce ME, Rodriguez GI, Rinaldi DA, Patt YZ, Hoff PM, Burris HA (1999) Phase II trial of docetaxel for cholangiocarcinoma. Am J Clin Oncol 22: 78–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penz M, Kornek GV, Raderer M, Ulrich-Pur H, Fiebiger W, Lenauer A, Depisch D, Krauss G, Schneeweiss B, Scheithauer W (2001) Phase II trial of two-weekly gemcitabine in patients with advanced biliary tract cancer. Ann Oncol 12: 183–186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polyzos A, Nikou G, Giannopoulos A, Toskas A, Kalahanis N, Papargyriou J, Michail P, Papachristodoulou A (1996) Chemotherapy of biliary tract cancer with mitomycin-C and 5-fluorouracil biologically modulated by folinic acid. A phase II study. Ann Oncol 7: 644–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raderer M, Hejna MH, Valencak J B, Kornek GV, Weinlander GS, Bareck E, Lenauer J, Brodowicz T, Lang F, Scheithauer W (1999) Two consecutive phase II studies of 5-fluorouracil/leucovorin/mitomycin C and of gemcitabine in patients with advanced biliary cancer. Oncology 56: 177–180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakata Y, Ohtsu A, Horikoshi N, Sugimachi K, Mitachi Y, Taguchi T (1998) Late phase II study of novel oral fluoropyrimidine anticancer drug S-1 (1 M tegafur–0.4 M gimestat–1 M otastat potassium) in advanced gastric cancer patients. Eur J Cancer 34: 1715–1720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Altamira PM, O'Reilly E, Stuart KE, Raeburn L, Steger C, Kemeny NE, Saltz LB (2001) A phase II trial of irinotecan (CPT-11) for unresectable biliary tree carcinoma. Ann Oncol 12: 501–504 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka T, Nakano K, Takechi T, Satake H, Uchida J, Fujioka A, Saito H, Okabe H, Oyama K, Takeda S, Unemi N, Fukushima M (1996b) Antitumor activity of 1 M tegafur–0.4 M 5-chloro-2,4-dihydroxypyridine–1 M potassium oxonate (S-1) against human colon carcinoma orthotopically implanted into nude rats. Cancer Res 56: 2602–2606 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka T, Shimamoto Y, Fukushima M (1993) Inhibition by oxonic acid of gastrointestinal toxicity of 5-fluorouracil without loss of its antitumor activity in rats. Cancer Res 53: 4004–4009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirasaka T, Shimamato Y, Ohshimo H, Yamaguchi M, Kato T, Yonekura K, Fukushima M (1996a) Development of a novel form of an oral 5-fluorouracil derivative (S-1) directed to the potentiation of the tumor selective cytotoxicity of 5-fluorouracil by two biochemical modulators. Anticancer Drugs 7: 548–557 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taal BG, Audisio RA, Bleiberg H, Blijham GH, Neijt JP, Veenhof CH, Duez N, Sahmoud T (1993) Phase II trial of mitomycin C (MMC) in advanced gallbladder and biliary tree carcinoma. An EORTC Gastrointestinal Tract Cancer Cooperative Group Study. Ann Oncol 4: 607–609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taïeb J, Mitry E, Boige V, Artru P, Ezenfis J, Lecomte T, Clavero-Fabri MC, Vaillant JN, Rougier P, Ducreux M (2002) Optimization of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU)/cisplatin combination chemotherapy with a new schedule of leucovorin, 5-FU and cisplatin (LV5FU2-P regimen) in patients with biliary tract carcinoma. Ann Oncol 13: 1192–1196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takada T, Kato H, Matsushiro T, Nimura Y, Nagakawa T, Nakayama T (1994) Comparison of 5-fluorouracil, doxorubicin and mitomycin C with 5-fluorouracil alone in the treatment of pancreatic-biliary carcinomas. Oncology 51: 396–400 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tatsumi K, Fukushima M, Shirasaka T, Fujii S (1987) Inhibitory effects of pyrimidine, barbituric acid and pyridine derivatives on 5-fluorouracil degradation in rat liver extracts. Jpn J Cancer Res 78: 748–755 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsavaris N, Kosmas C, Gouveris P, Gennatas K, Polyzos A, Mouratidou D, Tsipras H, Margaris H, Papastratis G, Tzima E, Papadoniou N, Karatzas G, Papalambros E (2004) Weekly gemcitabine for the treatment of biliary tract and gallbladder cancer. Invest New Drugs 22: 193–198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van den Brande J, Schoffski P, Schellens JH, Roth AD, Duffaud F, Weigang-Kohler K, Reinke F, Wanders J, de Boer RF, Vermorken JB, Fumoleau P (2003) EORTC Early Clinical Studies Group early phase II trial of S-1 in patients with advanced or metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer 88: 648–653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Groeningen CJ, Peters GJ, Schornagel JH, Gall H, Noordhuis P, de Vries MJ, Turner SL, Swart MS, Pinedo HM, Hanauske AR, Giaccone G (2000) Phase I clinical and pharmacokinetic study of oral S-1 in patients with advanced solid tumors. J Clin Oncol 18: 2772–2779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Riel JM, van Groeningen CJ, Pinedo HM, Giaccone G (1999) Current chemotherapeutic possibilities in pancreaticobiliary cancer. Ann Oncol 10: 157–161 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yee K, Sheppard BC, Domreis J, Blanke CD (2002) Cancers of the gallbladder and biliary ducts. Oncology (Huntingt) 16: 939–957 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]