Abstract

The relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein was evaluated in patients with benign (n=59) and malignant (n=86) prostate disease. The correlation coefficients for patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer were rs=0.632, P<0.001 and rs=0.663, P<0.001, respectively. These results indicate that the relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein is similar in patients with benign and malignant prostate disease.

Keywords: benign prostatic disease, prostate cancer, interleukin-6, C-reactive protein, Gleason score, total PSA

The systemic inflammatory response is an obligatory response of the body to infection, surgery or trauma. There is also increasing evidence that the presence of a systemic inflammatory response, as evidenced by increased circulating concentrations of C-reactive protein, is associated with early recurrence and poor survival in a variety of common hormone-independent tumours (Neilsen et al, 2000; Scott et al, 2002; McMillan et al, 2003). There is also some evidence that a similar relationship exists in hormone-dependent tumours (Lewenhaupt et al, 1990; Albuquerque et al, 1995).

A number of factors appear to mediate the increased production of C-reactive protein. In injury, the pro-inflammatory cytokines, interleukin-1, TNF-alpha and interleukin-6 in particular, have been shown to stimulate the production of C-reactive protein (Gabay and Kushner, 1999). In cancer, the factors which determine circulating concentrations of C-reactive protein are less clear, since studies in cell lines and animal tumour models have demonstrated that a number of factors stimulate C-reactive protein production. For example, it has been shown that leukaemia inhibitory factor and ciliary neurotrophic factor are also capable of inducing an acute-phase protein response from the liver (Baumann et al, 1993; Henderson et al, 1994; Akiyama et al, 1997). There is also evidence that soluble receptor subunits involved in interleukin-6 signal transduction, the soluble interleukin-6 receptor and the soluble gp130 receptor may be important in the regulation of interleukin-6 activity and the acute-phase protein response (Narazaki et al, 1993; Jones and Rose-John, 2002). Therefore, if in cancer patients C-reactive protein was stimulated by factors other than interleukin-6, then it might be expected that the relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein would be less strong than that in patients with benign disease.

The aim of the present study was to examine the relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in patients with benign disease (BPH) and in prostate cancer.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

Consecutive patients undergoing diagnostic transrectal ultrasound-guided (TRUS) biopsy of prostate were included in the study. The indication for TRUS biopsy was either a total PSA concentration greater than 4 ng ml−1 and/or an abnormal digital rectal examination.

Prior to biopsy, a blood sample was obtained and the serum stored at −20°C prior to analysis. No patient had a digital rectal examination within a 2-week period prior to sampling. No patient was receiving treatment at the time of blood sampling.

None of the patients had participated in a formal screening programme. All patients underwent a minimum of systematic sextant biopsy. A Gleason score was allocated for each tumour. The Gleason score reflects tumour heterogeneity by combining primary and secondary patterns into a composite score, which has been shown to be an important predictor of disease recurrence and survival (Epstein et al, 1993). Gleason scores were compressed as recommended previously (Bostwick et al, 2000).

The study was approved by the local Research Ethics Committee. All subjects were informed of the purpose and procedure of the study and all gave written consent.

Total PSA was measured using the Bayer ADVIA Centaur Assay system (Bayer PLC, Bayer House, Newbury, UK). Inter-assay variability was <6% for total PSA.

Interleukin-6 concentrations were measured using a sensitive solid-phase enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (R&D Systems Europe Ltd, Abingdon, UK). The lower level of detection was 0.2 pg l−1 and the intra-assay variability was less than 6% over the sample concentration range.

C-reactive protein concentration was measured using a sensitive double-antibody sandwich ELISA with rabbit anti-human C-reactive protein and peroxidase-conjugated rabbit anti-human C-reactive protein. The assay was linear from 0.1 to 5 mg l−1 and logarithmic thereafter. Inter-assay variation was less than 10% over the sample concentrations range.

Statistics

Data are presented as the median (range), and, where appropriate, differences between control and cancer groups were examined using the Mann–Whitney U test. Correlations between two variables were calculated using Spearman's rank correlation test. As the distribution of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein concentrations was skewed, they were logarithmically transformed to illustrate their relationship in patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer. Analysis was carried out using the statistics package SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

RESULTS

A total of 145 patients (59 with benign prostatic disease and 86 with prostate cancer) were included in the study. The characteristics of the patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer are shown in Table 1 . The majority of patients with prostate cancer had localised or locally advanced disease and had a low Gleason score. Compared to patients with benign prostatic disease, the cancer patients had higher circulating concentrations of total PSA (P<0.001). There were no significant differences in circulating concentrations of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein between patients with benign disease and prostate cancer.

Table 1. Characteristics of patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer.

| Benign prostatic disease (n=59) | Prostate cancer (n=86) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (⩽70/>70 years) | 45/14 | 52/34 | 0.069 |

| Stage (T1–T2/T3–T4/Met) | 37/37/12 | ||

| Gleason score (2–6, 7, 8–10) | 46/24/16 | ||

| Total PSA (ng ml−1)a | 7.0 (0.8–39) | 14.6 (0.5–146) | <0.001 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg ml−1)a | 2.3 (0.7–12.9) | 2.3 (0.8–28.1) | 0.526 |

| C-reactive protein (mg l−1)a | 2.0 (0.1–21) | 1.8 (0.3–50) | 0.891 |

Median (range).

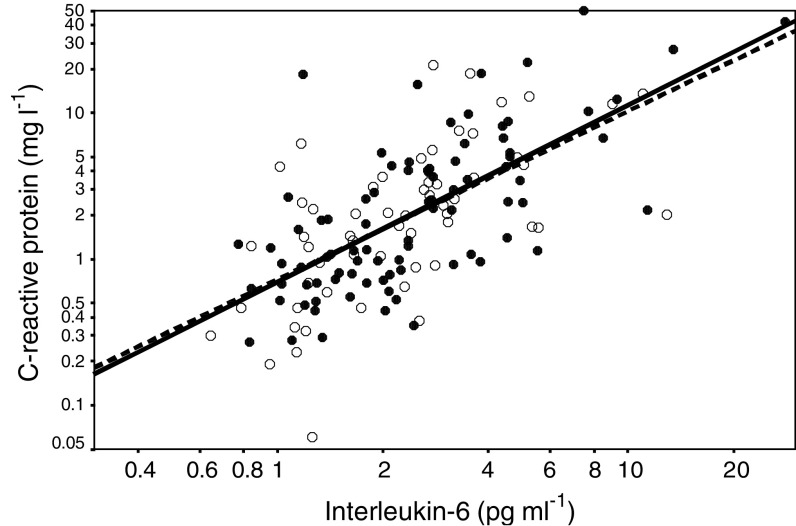

The relationship between circulating concentrations of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer is shown in Figure 1. The correlation coefficients for patients with benign prostatic disease and prostate cancer were rs=0.632, P<0.001 and rs=0.663, P<0.001, respectively.

Figure 1.

Relationship between circulating concentrations of interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in patients with benign prostatic disease (○) and prostate cancer (•).

The relationship between Gleason score, PSA, interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein in the patients with prostate cancer is shown in Table 2 . With increasing Gleason scores, there were significant increases in total PSA (P<0.05), interleukin-6 (P<0.01) and C-reactive protein (P<0.01). There was a significant correlation between Gleason score and total PSA (rs=0.364, P=0.001), interleukin-6 (rs=0.311, P=0.004) and C-reactive protein (rs=0.304, P=0.004). There was no significant association between total PSA and either interleukin-6 or C-reactive protein.

Table 2. Relationship between inflammatory parameters and Gleason score in patients with prostate cancer.

| Gleason score 2–6 (n=46) | Gleason score 7 (n=24) | Gleason score 8–10 (n=16) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (⩽70/>70 years) | 31/15 | 12/12 | 9/7 | 0.343 |

| Stage (T1–T2/T3–T4/Met) | 30/14/2 | 4/17/3 | 3/6/7 | <0.001 |

| Total PSA (ng ml−1)a | 11.0 (0.5–76) | 19.8 (3.7–116) | 18.7 (4.8–146) | 0.025 |

| Interleukin-6 (pg ml−1)a | 1.9 (0.8–11.4) | 3.1 (0.8–28.1) | 3.0 (1.1–9.3) | <0.005 |

| C-reactive protein (mg l−1)a | 1.1 (0.3–18.7) | 2.7 (0.3–50) | 3.3 (0.8–12.5) | <0.005 |

Median (range).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, there were no significant differences in the circulating concentrations of either interleukin-6 or C-reactive protein between patients with benign prostatic disease and those with prostate cancer. Furthermore, the relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein was similar in both patient groups.

In the cancer patients, there was a significant increase in both interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein concentration with increasing tumour grade. These results are also consistent with previous observations that concentrations of interleukin-6 and its receptor are increased in patients with a Gleason score greater than 7 (Shariat et al, 2001). This might suggest that the tumour was responsible for the increased production of interleukin-6. However, the increases in interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein were independent of total PSA.

An alternative explanation would be that the source of interleukin-6 is the host inflammatory cells. It is therefore of interest that recent studies have shown that a pronounced inflammatory infiltrate in the tumour was associated with poor outcome in patients with prostate cancer (Irani et al, 1999; McArdle et al, 2004).

Taken together, these observations confirm that interleukin-6 is predominantly responsible for the elaboration of C-reactive protein. Furthermore, they suggest that interleukin-6 is produced primarily by the host rather than the tumour. Moreover, it may also be that interleukin-6, produced by tumour-infiltrating leucocytes, stimulates tumour cell proliferation and promotes leucocyte recruitment as part of an autocrine growth factor loop (Corcoran and Costello, 2003).

In summary, the results of the present study indicate that the relationship between interleukin-6 and C-reactive protein is similar in patients with benign and malignant prostate disease.

References

- Akiyama Y, Kajimura N, Matsuzaki J, Kikuchi Y, Imai N, Tanigawa M, Yamaguchi K (1997) In vivo effect of recombinant human leukemia inhibitory factor in primates. Jpn J Cancer Res 88: 578–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albuquerque KV, Price MR, Badley RA, Jonrup I, Pearson D, Blamey RW, Robertson JF (1995) Pre-treatment serum levels of tumour markers in metastatic breast cancer: a prospective assessment of their role in predicting response to therapy and survival. Eur J Surg Oncol 21: 504–509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumann H, Ziegler SF, Mosley B, Morella KK, Pajovic S, Gearing DP (1993) Reconstitution of the response to leukemia inhibitory factor, oncostatin M, and ciliary neurotrophic factor in hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem 268: 8414–8417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick DG, Grignon DJ, Hammond ME, Amin MB, Cohen M, Crawford D, Gospadarowicz M, Kaplan RS, Miller DS, Montironi R, Pajak TF, Pollack A, Srigley JR, Yarbro JW (2000) Prognostic factors in prostate cancer. College of American Pathologists Consensus Statement 1999. Arch Pathol Lab Med 124: 995–1000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran NM, Costello AJ (2003) Interleukin-6: minor player or starring role in the development of hormone-refractory prostate cancer? BJU Int 91: 545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein JI, Pizov G, Walsh PC (1993) Correlation of pathologic findings with progression after radical retropubic prostatectomy. Cancer 71: 3582–3593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay C, Kushner I (1999) Acute-phase proteins and other systemic responses to inflammation. N Engl J Med 340: 448–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson JT, Seniuk NA, Richardson PM, Gauldie J, Roder JC (1994) Systemic administration of ciliary neurotrophic factor induces cachexia in rodents. J Clin Invest 93: 2632–2638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irani J, Goujon JM, Ragni E, Peyrat L, Hubert J, Saint F, Mottet N (1999) High-grade inflammation in prostate cancer as a prognostic factor for biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Pathologist Multi Center Study Group. Urology 54: 467–472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones SA, Rose-John S (2002) The role of soluble receptors in cytokine biology: the agonistic properties of the sIL-6R/IL-6 complex. Biochim Biophys Acta 1592: 251–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewenhaupt A, Ekman P, Eneroth P, Nilsson B (1990) Tumour markers as prognostic aids in prostatic carcinoma. Br J Urol 66: 182–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McArdle PA, Canna K, McMillan DC, McNicol A-M, Campbell R, Underwood MA (2004) The relationship between T-lymphocyte subset infiltration and survival in patients with prostate cancer. Br J Cancer 91: 541–543 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMillan DC, Canna K, McArdle CS (2003) Systemic inflammatory response predicts survival following curative resection of colorectal cancer. Br J Surg 90: 215–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narazaki M, Yasukawa K, Saito T, Ohsugi Y, Fukui H, Koishihara Y, Yancopoulos GD, Taga T, Kishimoto T (1993) Soluble forms of the interleukin-6 signal-transducing receptor component gp130 in human serum possessing a potential to inhibit signals through membrane-anchored gp130. Blood 82: 1120–1126 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neilsen HJ, Christensen IJ, Sorensen S, Moesgaard F, Brunner N (2000) Preoperative plasma plasminogen activator inhibitor type-1 and serum C-reactive protein levels in patients with colorectal cancer. The RANXO5 Colorectal Cancer Study Group. Ann Surg Oncol 7: 617–623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott HR, McMillan DC, Forrest LM, Brown DJ, McArdle CS, Milroy R (2002) The systemic inflammatory response, weight loss, performance status and survival in patients with inoperable non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer 87: 264–267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariat SF, Andrews B, Kattan MW, Kim J, Wheeler TM, Slawin KM (2001) Plasma levels of interleukin-6 and its soluble receptor are associated with prostate cancer progression and metastasis. Urology 58: 1008–1015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]