Abstract

The long-term ecological response to recurrent deforestation associated with shifting cultivation remains poorly investigated, especially in the dry tropics. We present a study of phosphorus (P) dynamics in the southern Yucatán, highlighting the possibility of abrupt shifts in biogeochemical cycling resulting from positive feedbacks between vegetation and its limiting resources. After three cultivation–fallow cycles, available soil P declines by 44%, and one-time P inputs from biomass burning decline by 76% from mature forest levels. Interception of dust-borne P (“canopy trapping”) declines with lower plant biomass and leaf area, limiting deposition in secondary forest. Potential leaching losses are greater in secondary than in mature forest, but the difference is very small compared with the difference in P inputs. The decline in new P from atmospheric deposition creates a long-term negative ecosystem balance for phosphorus. The reduction in soil P availability will feed back to further limit biomass recovery and may induce a shift to sparser vegetation. Degradation induced by hydrological and biogeochemical feedbacks on P cycling under shifting cultivation will affect farmers in the near future. Without financial support to encourage the use of fertilizer, farmers could increase the fallow period, clear new land, or abandon agriculture for off-farm employment. Their response will determine the regional balance between forest loss and forest regrowth, as well as the frequency of use and rate of recovery at a local scale, further feeding back on ecological processes at multiple scales.

Keywords: atmospheric deposition, phosphorus, positive feedback, shifting cultivation, soil degradation

At the turn of the century, shifting cultivation was responsible for 35% of deforestation in Latin America, 50% in Asia, and 70% in Africa (1), often in tandem with logging. Understanding the ecological consequences of shifting cultivation will help to explain feedbacks of land use change on human welfare, health, and decision-making in tropical forests. Once cleared, tropical forests tend not to revert to mature forest. Rather, they enter a new disturbance regime of relatively frequent, intense, large-scale clearing. Despite the growing recognition that human activities have a lasting ecological legacy (2), relatively few studies have characterized the ecological impacts of repeated human disturbance such as shifting cultivation.

With an adequate fallow period, shifting cultivation can sustain crop and forest productivity over the first several cycles of biomass burning, cultivation, and fallow (3–5). However, in the only study known to us extending beyond a few cycles (6), productivity in secondary forests declined by 11% after 6–10 cycles. No other studies have examined the consequences of shifting cultivation beyond the first few cycles, yet most tropical frontiers of deforestation are now moving beyond this initial stage. We propose that continued deforestation may fundamentally alter the biogeochemical cycles underpinning the ecosystem, leading to a decline in the availability of limiting nutrients such as phosphorus and thus in plant biomass and carbon storage. What are the long-term consequences of repeated shifting of cultivation for productivity, both to sustain farmers and to maintain healthy forest ecosystems? How will farmers respond?

These questions are especially critical for seasonally dry forests—the dominant forest type in the tropics and the one most affected by humans (7–9). In dry forests, water limitation may compound the effects of altered nutrient cycling to constrain forest recovery beyond the first few cycles of use. Shifting cultivation depends fundamentally on nutrient inputs from biomass burning, especially inputs of phosphorus (P), which tends to be limiting in tropical systems (10), including the dry forests studied here (11, 12). The immediate and long-term fate of nutrients made available through burning determines the success of the crop and the sustainability of the system. Substantial quantities of P may be lost to erosion, runoff, and harvest (13). Nevertheless, during the first cycle of shifting cultivation, the pool of P available for uptake by crops and then for regenerating forest is usually substantially greater than that found in mature forest soil before burning (13–18). Subsequently, however, the pool of most readily available P declines, although organically bound and occluded (less available) P may remain elevated during the first few cycles (17). Changes in the distribution of P induced by shifting cultivation in tropical dry forest have not yet been documented.

It is still unclear what causes a decline in plant-available P, whether it is due to the relatively short duration of the fallow period or to state changes in the coupled dynamics of vegetation and P cycling. A short fallow could truncate the internal transfers necessary to restore the pool of available P (19), whereas a sufficiently long fallow would allow the system to return to its initial (i.e., predisturbance) state. If severely disturbed, these systems may cross a critical threshold and undergo more permanent and irreversible transformations from which they recover with difficulty (20, 21). These more complex dynamics typically emerge in environments exhibiting a positive feedback between the state of the system and its limiting resources (22, 23). Thus, assessing the existence of positive feedbacks between P cycling and vegetation is crucial to understanding the long-term behavior of tropical dry forests under shifting cultivation. Although we focus here on dry forests, similar mechanisms should apply in wet tropical forests where soils tend to be old and P-limited (10, 24). By investigating the relationship between vegetation canopies and P deposition, this article provides a unique perspective on the mechanisms affecting, or preventing, the postdisturbance recovery of dry tropical forests. In fact, the short-term response (several cycles, several decades) can be understood by assessing changes in the P fluxes associated with reduced forest biomass. Land-cover changes resulting from deforestation may also influence the response over the longer term (the next century). Alteration of canopy size and structure may be associated with changes in hydrologically controlled P inputs (dry/wet deposition) and outputs (soil leaching), which in turn may cause a decline in plant-available P.

Here, we present a case study of deforestation in the dry forests of the southern Yucatán, highlighting the possibility of a dramatic shift in biogeochemical cycling. First, we demonstrate that soil P availability is declining under shifting cultivation. Then, to understand this decline, we evaluate changes in P fluxes through multiple cycles of shifting cultivation. We focus on one-time inputs from biomass burning in each cycle and recurrent inputs from litterfall throughout the fallow period. We also examine the shifting balance, following deforestation, between inputs from atmospheric deposition and outputs due to leaching.

Results

Soil Phosphorus Availability.

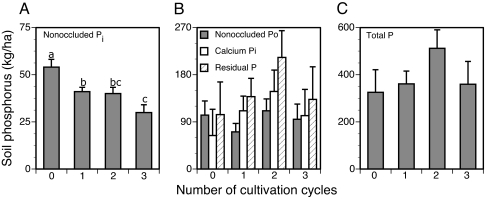

Available, nonoccluded inorganic phosphorus (Pi) in the top 15 cm of soil declined 24% after the first cycle, from (mean ± SE) 54 ± 4 kg/ha in mature forest to 41 ± 2 kg/ha in secondary forest (none ever fertilized; cycle effect, P = 0.01; F = 5.91; Fig. 1A). Nonoccluded Pi declined further, by 27%, from the first to the third cycle (30 ± 4 kg/ha). As a proportion of total P, nonoccluded Pi fell from ≈17% in mature forest to ≈8% in secondary forest after two or three cycles. Total P was 325 ± 96 kg/ha in mature forest and ranged from 360 ± 96 to 512 ± 78 kg/ha in secondary forest (Fig. 1C). Total P tended to increase in the second cycle and to decline again in the third; however, it did not vary significantly among mature and secondary forest, regardless of cultivation history. Organic P (Po), Ca-bound Pi, and occluded P showed similar, nonsignificant trends. Thus, despite substantial P inputs from burning of mature forest (Fig. 2), total P in surface soils remained unchanged, and available P declined by 44% after three cycles of shifting cultivation.

Fig. 1.

Soil phosphorus stocks in the top 15 cm as a function of number of cultivation cycles in secondary forest (n = 17, 5–16 years old) and in mature forest (n = 3; zero cycles). Mean ± SE for the most available fraction, nonoccluded Pi (A); for calcium-bound Pi, residual (occluded) P, and nonoccluded Po (B); and for total P (C). None of the sites had received chemical inputs.

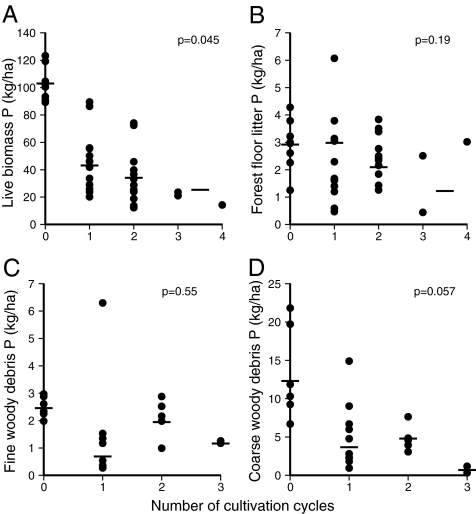

Fig. 2.

Phosphorus stocks in live and dead biomass as a function of number of cultivation cycles. Stocks in live wood, leaves, and roots (A) and in forest floor litter (<1.8 cm in diameter) (B) were determined for 28 secondary forests (2–25 years old) and 8 mature forests. Stocks in fine woody debris (1.8–10 cm in diameter) (C) and in coarse woody debris (>10 cm in diameter) (D) were determined for 17 secondary forests (5–16 years old) and 6 mature forests. Horizontal lines indicate marginal means for secondary forest and geometric mean for mature forest (zero cycles). None of the sites had received chemical inputs.

Biomass-Burning Inputs.

The most substantial shift in all pools of phosphorus occurs in live biomass after the original conversion from mature to secondary forest. The decline of 58% [60 kg/ha), from 103 in mature forest to 43 in 10-year-old secondary forest] swamps the change in all other fractions (Fig. 2). Coarse woody debris P declined by 66% after the transition from mature to secondary forest, but the absolute change in the pool was only 8 kg/ha (Fig. 2D). Neither fine woody debris P nor forest floor P differed significantly after the initial conversion to secondary forest.

Phosphorus stocks in live biomass of secondary forest declined by 41% from the first to the third cycle of shifting cultivation (cycle effect, P = 0.045; full model, P < 0.001; r2 = 0.82), from 43 ± 7 to 25 ± 12 kg/ha (marginal mean ± SE). Coarse woody debris P declined 81%, from 3.7 ± 1.3 to 0.7 ± 1.7 kg/ha, between the first and third cycles (cycle effect, P = 0.057; full model, P = 0.002; r2 = 0.47). P inputs from fine woody debris did not vary significantly with the number of cycles, ranging from 0.7 to 1.9 kg/ha (vs. 2.4 kg/ha in mature forest). Although the mass of forest floor litter declined significantly from the first to the third cycle, the concomitant decline in forest floor P (from 3.0 to 1.2 kg/ha) was not significant (Fig. 2B; cycle effect, P = 0.19).

Litter Phosphorus Inputs.

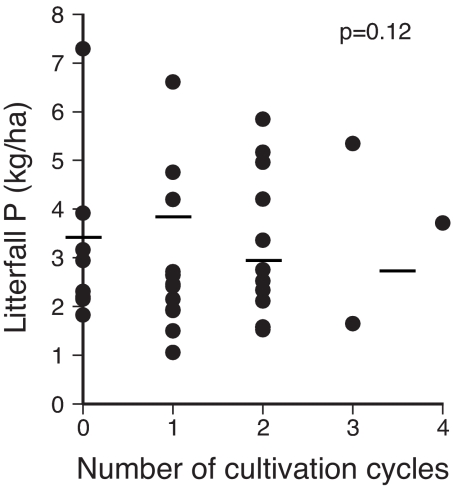

Annual litter P input was 3.9 ± 0.4 kg/ha during the first cycle and ranged from 2.9 ± 0.4 to 3.1 ± 0.7 kg/ha during the second and third cycles (Fig. 3). Despite an apparent decline of 23% beyond the first cycle (cycle effect, P = 0.12; full model, P = 0.0001; r2 = 0.54) and a significant 20% decline in annual litter mass beyond two cycles (data not shown), litter P inputs did not change significantly through multiple cycles of deforestation.

Fig. 3.

Annual phosphorus flux in litterfall as a function of number of cultivation cycles. Litterfall was sampled in live biomass plots (n = 36; see Fig. 2 legend for details). Horizontal lines indicate marginal means for secondary forest and geometric mean for mature forest (zero cycles). None of the sites had received chemical inputs.

Leachate Phosphorus.

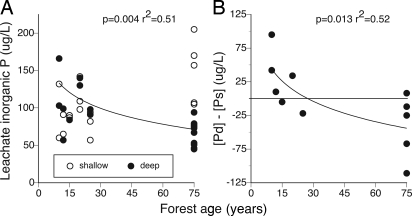

Across depths, secondary forests had marginally higher leachate [P] than mature forests (103 ± 7 vs. 88 ± 7 μg/liter; age class effect, P = 0.13), with a significant interaction between age and depth. Deep leachate [P] declined significantly with age, whereas shallow leachate [P] was not related to age (Fig. 4A). The difference in concentration between deep and shallow leachate ([Pdeep] − [Pshallow]) declined significantly with forest age (Fig. 4B). Young secondary forests had mostly positive values of [Pdeep] − [Pshallow], indicating more P in deep vs. shallow leachate. The reverse was true in older secondary and mature forests, indicating less P in deep vs. shallow leachate. Estimated cumulative P in deep leachate was lower in mature forest (≈0.07 ± 0.11 kg/ha per year) than in secondary forest (0.09 ± 0.08 kg/ha per year) but not significantly so because of high variability in the data. Leachate [P] varied more by location (65 ± 11 to 126 ± 12 μg/liter) than by age class or depth class (block effect, P = 0.014; full model, P = 0.038; r2 = 0.73).

Fig. 4.

Effect of forest age on potential phosphorus losses to leaching. (A) Leachate Pi concentration as a function of forest age and soil depth. (B) The difference between deep and shallow leachate Pi concentrations by location, [Pdeep] − [Pshallow], as a function of forest age. None of the sites had received chemical inputs.

Atmospheric Deposition of Phosphorus.

The mean P concentration of throughfall in the forests was 66–170% greater than that of bulk deposition in an open field (P < 0.001 for all comparisons; Table 1). All forests had significantly greater mean P inputs than the open field on a mass basis as well (P < 0.0001 for all comparisons). Mean P inputs per event were almost twice as great in the mature as in the 4-year-old forest (12.3 ± 1.0 vs. 6.5 ± 0.5 g/ha; Table 1). Mean inputs did not differ significantly between the mature and the 20-year-old forest, which received 11.8 ± 1.3 g/ha per collection. Scaling to the entire wet season, we estimate inputs of 0.43, 0.71, and 0.81 kg/ha for 4-year-old, 20-year-old, and mature forest, respectively, vs. 0.26 kg/ha in the open.

Table 1.

Atmospheric deposition of phosphorus as a function of canopy cover and forest age

| Cover | [P], μg/liter | P input per event, g/ha | Cumulative P input, g/ha per month* | Estimated wet season P inputs, kg/ha† |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open field | 24 ± 5a | 4.2 ± 0.5a | 43 | 0.26 |

| 4-yr-old forest | 40 ± 5b | 6.5 ± 0.5b | 72 | 0.43 |

| 20-yr-old forest | 59 ± 6c | 11.8 ± 1.3c | 119 | 0.71 |

| Mature forest | 65 ± 6c | 12.3 ± 1.0c | 134 | 0.81 |

Mean ± SE. Letters a–c indicate significant differences.

*For the period June 2 to July 1, 2006.

†Cumulative P input × 6 (average no. of rainy months).

Discussion

The availability of phosphorus, a limiting resource, clearly declines after three cycles of shifting cultivation in dry tropical forests. By the third cycle, the pool of available P is not adequate to support the regeneration of mature forest biomass, although it can still support secondary forest. Although there may be a transient increase in organic and occluded P due to P inputs from biomass burning, by the third cycle these pools are not significantly greater than in mature forest (Fig. 1). In any case, the role of these pools in replenishing available P is constrained by the slow rate of transfers from these recalcitrant pools (19, 25). The typical fallow period (5–15 years in this region) would most likely be inadequate. More importantly, non-soil inputs to replenish the available pools are much smaller after several cycles. Total biomass burning contributions of P decline from an estimated 120 kg/ha in mature forest to 50 kg/ha in 10-year-old forest during the first cycle (summed from Fig. 2). By the third cycle, biomass burning contributions are 28 kg/ha. Adding this pool to available P in the soil after three cycles (30 kg/ha) yields only 60% of the amount required to regenerate mature forest (103 kg/ha, as in Fig. 2).

P Losses Following Deforestation.

Thus, as available P declines, the biomass it could potentially support also declines. In addition, in these tropical dry forests, the observed biomass—the stock that should replenish the pool of available P—also declines. The result is a downward spiral for available P and biomass, suggesting that ecosystem processes do not fully recover during the timeframe of a typical fallow (5–15 years). Phosphorus losses can be partly explained as the result of losses in ash transported by wind and water (13) and in harvest. In addition, P losses are exacerbated by changes in the coupled dynamics of vegetation and P cycling, specifically, those mentioned above relating to biomass-derived P inputs, as well as hydrologically mediated P fluxes.

Altered P Deposition.

This study demonstrates that P losses are compounded by the postdisturbance decrease in P input from atmospheric deposition. Our estimates of P deposition in rainfall (0.26–0.81 kg/ha per year) are comparable to those from other tropical systems (26–30) and are consistent with the few existing measurements showing P enrichment in throughfall (27, 30). Our data support a positive feedback between inorganic P deposition and vegetation: the presence of the canopy augments the amount of P deposited by throughfall to the forest floor. Furthermore, changes in the size, leaf area, or complexity of the canopy appear to enhance deposition as a forest ages (Table 1). This effect is presumably due to the ability of the canopy to “catch” airborne particles, which are subsequently transported to the ground by storm water washing plant surfaces. Similar mechanisms have been documented (mostly for nitrogen) in other systems in which the canopy plays an active role in “trapping” nutrients from the air masses moving through it (31–33), both by dry deposition (34–38) and by canopy condensation or fog deposition (22, 39–41). The role of this feedback in the recovery of tropical dry forests from shifting cultivation has never been investigated. In P-limited systems, this mechanism of enhanced P deposition favors vegetation growth and survival. Thus, in tropical dry forest, plants may contribute to the creation and maintenance of the ecosystem through physical mechanisms capable of regulating resource availability (23).

Assuming that mature forest is in a state of dynamic equilibrium, throughfall P inputs are balanced by losses due to occlusion, leaching, and erosion. Lower inputs following deforestation disrupt this balance. When compared with throughfall inputs to mature forest, the estimated deficit in throughfall P inputs is 3.4 kg/ha for 3 years of cultivation followed by a typical 5-year fallow period (using data in Table 1). A longer fallow period is likely to increase the per-cycle deficit somewhat, but not substantially, because throughfall P does not differ significantly between 20-year-old and mature forest (Table 1). Older secondary forests (>12 years) and mature forests have different canopy structure (42) but similar litterfall (43) and, therefore, leaf area. This parity suggests that throughfall inputs would no longer differ after 12 years of fallow, a period at the long end of the observed range. Extrapolating throughfall inputs for forests 5–12 years old (≈0.57 kg/ha per year), we estimate the maximum deficit to be 5 kg/ha over one cycle for fallow periods 12 years or longer. This lost input represents >9% of the available phosphorus pool in mature forest, a fraction that will increase with time (already 16% in the third cycle) as the available pool declines with repeated shifting cultivation. These are not trivial losses. Without other inputs, the system may sustain six or fewer additional cycles (given 30 kg/ha in the available P pool and throughfall inputs 5 kg/ha lower than in mature forest).

P Input from Deep-Root “Pumping.”

Litterfall P inputs may compensate for lost throughfall inputs if secondary dry forests exhibit deep rooting and nutrient pumping, as observed in secondary wet forests (17, 44). The observed range of P inputs (2.9–3.9 kg/ha per year) would result in ≈30–40 kg/ha added during the first 10 years of the fallow period. Whether cumulative litter inputs offset lost throughfall inputs depends on how much P cycles back into biomass production (25–43 kg/ha is needed to regrow a 10-year-old forest; Fig. 2) and how much replenishes pools in the surface soil. Results from this study suggest a possible 20% decline in annual litter P inputs after the first cycle but no change from the second to the third (Fig. 3). Thus, potential pumping inputs are likely to be greatest during the first cycle. The number of years during which nutrient pumping can occur, defined by the fallow period, is critical for determining whether nutrient pumping can maintain the P balance after deforestation. The maintenance of total P over three cycles, despite losses to harvest, erosion, and diminished throughfall, suggests that some P is added from deep soils. Documenting this phenomenon, determining whether pumping capacity is diminished through time, and evaluating the size of deep soil P stocks should be top priorities for research.

Leaching Losses.

Our leachate measurements indicate that more plant-available P is transported to deep soils in young secondary forests than in mature forests. As measured by the increase in leachate P concentration with depth, secondary forests demonstrate the potential for P losses (Fig. 4). In contrast, mature forests show evidence for P conservation (by reducing the concentration of P in deep leachate). However, the difference in annual losses from mature and secondary forests estimated by deep leachate concentration was not significant, and the P flux itself is very small (<0.10 kg/ha per year). Thus, changes in the long-term P balance are likely to result primarily from altering throughfall inputs rather than from leaching losses. Our results suggest that “canopy trapping” is the dominant positive feedback between vegetation and P dynamics in tropical dry forest.

Conclusions

Deforestation disrupts the phosphorus cycle by weakening the rate of P deposition, the major mechanism of P input to the system. This effect, combined with the enhancement of mobile P leaching, leads to a less conservative cycling of P and, over the coming decades in the Yucatán, a decline in plant-available P. Depending on the ability of the system to recover after deforestation without relying on the additional P input from canopy trapping, the existence of this feedback could accelerate the rate of forest regeneration (growth enhancing P deposition, which spurs growth). Alternatively, beginning with stimulus from a decline in the soil component, the feedback may prevent complete recovery as the system moves along a trajectory of decreasing P availability through several cycles of deforestation–reforestation (slowed growth, lowering P deposition and further reducing growth). Systems such as this that exhibit positive feedbacks controlling resource availability have been shown to possess limited resilience, due to the possible existence of alternative (and undesirable) stable states (21). These systems may be prone to discontinuous and abrupt state changes in response to disturbance (20, 22). Thus, in the long run, disturbed tropical dry forests may respond to shifting cultivation with relatively abrupt and irreversible shifts to states with poor vegetation cover and limited P availability, with consequent loss of ecosystem function and service.

Our results suggest that hydrological and biogeochemical feedbacks on the cycling of phosphorus under shifting cultivation are likely to slow forest regeneration, affecting crop yields and farmer livelihoods in the near future. Changes in the ecological system will feed back on human decision-making and future land cover change. As the ecosystem degrades, farmers could respond by increasing the fallow period to ensure adequate biomass inputs of P, or they could instead seek new land for cultivation, increasing the rate of deforestation in previously undisturbed mature forest. Most farming communities in the region still possess large forest reserves, but by law they are not allowed to clear them for agriculture (45). Furthermore, clearing mature forest is unlikely because current policies promote cultivation on extant open land or secondary forest. We have not observed either an increase in fallow length or an increase in deforestation of previously uncut forest (42). Adding fertilizer P is not economically viable at present but could be in the future.

Alternatively, farmers may opt out of agriculture, increasing their reliance on off-farm employment within the region or across the border in the United States. Remittance-driven emigration is already an important part of household livelihoods, and it has increased in the last decade (46). The consequences of this last option are unclear, although preliminary data suggest that off-farm income is used to convert secondary forest to pasture (B. I. Schmook, personal communication). Another possible outcome is abandonment of land, effectively extending the fallow period and ushering in a period of ecosystem recovery. Regardless of how farmers adapt and respond to these ecological changes, the transition is likely to exact a great cost in both human and environmental health and well-being.

Materials and Methods

Study Area.

The study was conducted in the buffer zone of the Calakmul Biosphere Reserve in the areas of El Refugio (ER), Zoh Laguna (ZL), Nicolas Bravo (NB), and Arroyo Negro (AN) (17–18°N, 88–89°W). The tropical dry forest landscape is flat to rolling, with elevations ranging from ≈100 to ≈350 m above sea level. Median annual rainfall ranges, north to south, from 890 to 1,420 mm. Soils are well developed mollisols and vertisols overlying calcium carbonate-rich karst (pH 7.4–7.7 to 15 cm); we focus on the mollisols. We studied mature and secondary forests. Mature forests had never been cut in recent history but are likely to have been logged in the past century. Secondary forests were regenerating from land that had been used exclusively for shifting cultivation of maize, with no mechanization and no inputs of herbicide, pesticide, or fertilizer.

Soil Phosphorus Availability.

In ER in January 2003, one 192-m2 plot was established in each of 17 secondary forests (5–16 years old, 1–3 cycles) and 3 mature forests. Soils were collected at six points along two perpendicular transects. At each point, we took three cores (using a 2.5-cm-diameter auger) of the top 15 cm of soil. Soils were air-dried in the field, then sieved (>2 mm) and composited by site. Using Tiessen and Moir's modification (47) of the Hedley fractionation, we measured pools of P through sequential extraction, omitting the concentrated HCl extraction. The supernatant generated at each stage of the fractionation was analyzed colorimetrically on an Alpkem Flow Solution IV autoanalyzer (OI Analytical), according to standard EPA methods for total P. We grouped the P fractions as follows: nonoccluded Pi = NaHCO3-extractable Pi + NaOH-extractable Pi; Po = NaHCO3-extractable Po + NaOH-extractable Po; Ca-bound P = P extracted with 1 M HCl; and occluded P = residual P (48).

As observed in other parts of the world, high total P tended to coincide with stands that had longer cultivation histories, so we blocked by total P. “Low” sites were associated with mature forest that had 190–288 kg/ha and “high” sites were associated with mature forest that had 488–662 kg/ha. P distribution did not vary systematically with forest age; therefore, we modeled each pool as a function of number of cycles and block using a two-factor ANOVA in SPSS version 10.

Fluxes from Biomass Burning.

Live biomass and fine litter on the forest floor were measured in ER, NB, and AN (28 secondary and 8 mature forests). Fine and coarse woody debris were measured in ER (17 secondary and 6 mature forests).

Live biomass P.

Aboveground biomass (stems >1 cm in diameter) was measured in one 500-m2 circular plot per stand (49). For this study, mean root contribution to total live biomass (to 0.3 m) was estimated as 28% (13, 50) and added to aboveground biomass. Inputs of P were calculated by multiplying the proportion of living biomass in each component (roots, wood, and leaves) by the P concentration of that component derived from the literature. Using mean live biomass per age class, we first estimated P content for secondary forests <10 years old, secondary forests >10 years old, and mature forests. From these data, we derived age class-specific biomass:P ratios (1,203, 1,517, and 1,842, respectively). Using these ratios, we determined the P content of live biomass in each forest sampled.

Forest floor P.

Forest floor litter includes all material <1.8 cm in diameter. It was measured in four 1-m2 areas per stand between October and November 1998. Because forest floor litter P was not directly analyzed, we estimated it as a function of measured forest floor C:N ratio and mass and the N:P ratio in litterfall, as follows:

A mass-based C:N ratio for the forest floor of each stand was determined after combustion in a Fison CHN analyzer. For each location (ER, NB, and AN), mean (mass-based) N:P ratios were generated for the three age classes used above. The N:P ratios ranged from 23 to 27 for secondary forests and from 24 to 39 for mature forests.

Woody debris P.

Fine woody debris (1.8–10 cm in diameter) was measured in 16 1-m2 plots per stand spread equally between two 804-m2 circular plots. Coarse woody debris (>10 cm in diameter) was measured in these larger plots (51). To estimate the P content of both fine and coarse woody debris, we multiplied mass by 0.045%, the P concentration of wood used to determine the contribution of live wood above (13).

Statistical approach.

To determine the change in P inputs derived from burning over many cycles of cultivation, we used a general linear model (GLM) (SPSS version 10). The P contribution from individual components was modeled as a function of study area, forest age, and number of cultivation cycles (the latter two are continuous and are treated as covariates in the model). Sensitivity analysis showed that results were similar given a mature forest age in the range of 50–200 years, so we assigned an age of 75 years. The number of cycles in mature forest was zero. To quantify the per-cycle impact of repeated shifting of cultivation, we also determined the marginal means for each component by cycle, accounting for age and study area. Marginal means assume a forest of 10 years. We had two sites that had experienced three cycles and only one that had experienced four cycles. For analysis of marginal means, we combined data from these three sites. Geometric means were calculated for mature forest because correcting for age was not appropriate. Where necessary, data were log-transformed to satisfy assumptions of normality and equal variance before performing statistical analysis.

Recurrent Phosphorus Fluxes.

Litter P.

Phosphorus inputs in litter were calculated for the same sites as were biomass inputs, above. Litter mass was measured once a month in four 1-m2 litterfall traps per stand from January through December 1999, and litter P concentration was determined from one composite sample per stand per month (11). P inputs for each site were determined by multiplying monthly litter mass by monthly P concentration in litter and summing over the year. Annual litter P inputs were modeled as a function of study area, forest age, and number of cultivation cycles, as described above.

Leachate P.

Zero-tension lysimeters were installed in adjacent secondary (10–25 years old) and mature (assigned as 75 years old) forest pairs around ZL and ER. Two shallow and two deep lysimeters were installed in each pair of stands at six locations (12 stands total). Placement of lysimeters below the root zone is expected to capture soil solution samples that represent a loss to the system, although the presence of deep roots may pose a challenge to this assumption (52). The lysimeters used in this study were modeled after Richter et al. (53): 3-in diameter polyvinyl chloride (PVC) pipe was sliced to create an opening with semiaxes of 10.16 and 5.08 cm. The pipe was lined with mesh, capped, and connected by tubing to a 1-liter high-density polyethylene (HDPE) collection bottle.

Lysimeters were installed in March and May 2005. Two small trenches (10 cm wide and 60 cm long) were dug on either side of a 1-m-deep hole, 180° from each other. The first trench was dug to a depth of ≈5–15 cm, no deeper than the root zone. The second trench was dug to a depth below the root zone (15–55 cm deep, depending on the site). A lysimeter was pressed into the soil profile beneath the undisturbed soil surface at the far end of each trench. The trenches were backfilled, and the site was restored to as natural a state as possible. In all but one stand, a second set of lysimeters was installed within 10–15 m of the first.

Leachate samples were collected at 2- to 3-week intervals from May through July 2005 and at 1-month intervals during the remaining wet season (July–November). A final collection occurred in late May 2006. Samples were refrigerated or frozen in the field before being transported to the University of Virginia for analysis. Samples were analyzed colorimetrically for orthophosphate (PO4−) on an Alpkem Flow Solution IV autoanalyzer (OI Analytical), following standard EPA methods. We did not quantify fine-particulate or organic P.

Mean leachate P concentration was determined for each lysimeter (n = 8–10 observations). We analyzed the effect of location (block), age class, and depth class on mean leachate P with a GLM in SPSS version 10. Because of a significant interaction between age class and depth class, we subsequently analyzed the effect of age by depth class, using logarithmic regression. To quantify the change in leachate P concentration with depth, the mean shallow value was subtracted from the mean deep value for each stand (i.e., [Pdeep] − [Pshallow]). Positive values represent higher [P] in deep leachate, indicating the potential for leaching losses. Negative values represent higher [P] in shallow leachate, indicating potential nutrient conservation. This difference was regressed against forest age. Finally, we multiplied mean deep leachate [P] by cumulative volume and converted to an area-based value to estimate total leachate P losses per stand.

Atmospheric P deposition.

In ER, we measured P concentrations in throughfall collected under adjacent forest canopies of different age (4 years, 20 years, and mature). We also sampled bulk deposition of P at an open field. Previous work in ER has shown that forests such as these would be 5.7, 9.3, and 12.1 m tall, with a density of 70, 550, and 880 trees per hectare >10 cm diameter at breast height, respectively (42). In each stand, fourteen 10-liter plastic buckets were dispersed every 3 m along three 15-m-long transects. These collectors were covered with mesh (1 mm) to prevent sample contamination and installed ≈40 cm above ground. Six collectors were placed in the adjacent open field.

Separating the contributions to throughfall from dry deposition vs. canopy leaching is extremely difficult. The limited data available (54–56) suggest that leaching of P is minimal because leaf P is mostly in organic, immobile forms (58). We also find that mature forest throughfall [P] declines with increasing storm depth, whereas bulk deposition [P] (open-field collection) is not affected by storm size. This pattern is characteristic of dry deposition input, where material is washed out of the canopy relatively quickly and concentrations decrease with time. Conversely, leaching losses would result in a relatively constant throughfall concentration and increasing inputs with increased storm size (57, 58). In this study, we treat throughfall P data as an indication of deposited, rather than leached, P.

Collectors were deployed on June 2, 2006, and samples were collected on June 4, 5, 8, 9, 13, 14, 17, 24, 25, and 26 and July 1 (11 days). Volume was estimated from the graduations on the inside of the bucket. Subsamples were collected in 120-ml polyethylene bottles, preserved with sulfuric acid, and then transported to the University of Virginia and frozen until analysis. Samples were analyzed colorimetrically on an Alpkem Flow Solution IV autoanalyzer (OI Analytical), as for leachate P. For each collector on each date, inorganic P concentration was multiplied by collection volume to determine volume-based throughfall P and then converted to an area-based P input (g/ha). Repeated-measures ANOVA was used to compare by stand and date of collection. The collectors in each stand were treated as 14 replicate observations for that stand. Data were log-transformed to satisfy assumptions of normality and equal variance before performing statistical analysis.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank the farmers of the Southern Yucatán Peninsular Region (SYPR) and Tana Wood, Larissa Read, Fausto Bolom Ton, Jessica Sisco, Heidi Wasson, Kimberly White, Khadija Abdurhaman, Zachary Lucy, and Luke Dupont for assistance. This article is a product of the SYPR Project, sponsored by National Aeronautics and Space Administration Land-Cover and Land-Use Change Program Grants NAG5-6046 and NAG5-11134, Carnegie Mellon University Grant SBR 95-21914, National Science Foundation Grant BCS-0410016, The Mellon Foundation, and the University of Virginia.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

References

- 1.Whitmore TC. Tropical Rain Forests of the Far East. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Foster D, Swanson F, Aber J, Burke I, Brokaw N, Tilman D, Knapp A. Bioscience. 2003;53:77–88. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nye PH, Greenland DJ. The Soil Under Shifting Cultivation. Harpenden, UK: Commonwealth Bureau of Soils; 1960. Technical Communication No 51. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hughes RF, Kauffman JB, Cummings DL. Oecologia. 2000;124:574–588. doi: 10.1007/s004420000416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steininger MK. J Trop Ecol. 2000;16:689–708. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lawrence D. Ecology. 2005;86:26–33. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Murphy PG, Lugo AE. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1986;17:67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Janzen DH. In: Biodiversity. Wilson EO, editor. Washington, DC: Natl Acad Press; 1988. pp. 130–137. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullock SH, Mooney HA, Medina E, editors. Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vitousek PM. Ecology. 1984;65:285–298. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Read L, Lawrence D. Ecosystems. 2003;6:747–761. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Campo J, Vazquez-Yanes M. Ecosystems. 2004;7:311–319. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kauffman JB, Sanford RL, Cummings DL, Salcedo IH, Sampaio EVSB. Ecology. 1993;74:140–151. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ewel J, Berish C, Brown B, Price N, Raich J. Ecology. 1981;62:816–829. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanchez PA, Villachica JH, Bandy DE. Soil Sci Soc Am J. 1983;47:1171–1178. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uhl C. J Ecol. 1987;75:377–407. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawrence D, Schlesinger WH. Ecology. 2001;82:2769–2780. [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGrath DA, Smith CK, Gholz HL, de Assis Oliveira F. Ecosystems. 2001;4:625–645. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markewitz D, Davidson E, Moutinho P, Nepstad D. Ecol Appl. 2004;14(Suppl):177–199. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheffer M, Carpenter S, Foley JA, Folke C, Walker B. Nature. 2001;413:591–595. doi: 10.1038/35098000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker BH, Salt D. Resilience Thinking: Sustaining Ecosystems and People in a Changing World. Washington, DC: Island Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wilson JB, Agnew ADQ. Adv Ecol Res. 1992;23:263–336. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jones CG, Lawton JH, Shachak M. Oikos. 1994;69:373–386. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Richter DD, Babbar LI. Adv Ecol Res. 1991;21:315–389. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cross AF, Schlesinger WH. Geoderma. 1995;64:197–214. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bruijnzeel LA. J Trop Ecol. 1991;7:1–24. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schroth G, Elias MEA, Uguen K, Seixas R, Zech W. Agric Ecosyst Environ. 2001;87:37–49. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tobón C, Sevink J, Verstraten JM. Biogeochemistry. 2004;70:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Veneklaas EJ. J Ecol. 1990;78:974–992. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Campo J, Maass M, Jaramillo VJ, Martínez-Yrízar A, Sarukhán J. Biogeochemistry. 2001;53:161–179. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mcgowan H, Ledgard N. J R Soc N Z. 2005;35:269–277. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Vetaas OR. J Veg Sci. 1992;3:337–344. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kellman M. J Ecol. 1979;64:565–577. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schlesinger WH, Reynolds JF, Cunningham GL, Huenneke LF, Jarrell WM, Virginia RA, Whitford WG. Science. 1990;247:1043–1048. doi: 10.1126/science.247.4946.1043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lovett GM, Lindberg SE. J Appl Ecol. 1984;21:1013–1027. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Potter CS, Ragsdale HL, Swank WT. J Ecol. 1991;79:97–115. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kellman M, Hudson J, Sanmugadas K. Biotropica. 1982;14:1–9. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newman EI. J Ecol. 1995;83:713–726. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fowler D, Cape JN, Unsworth MH. Philos Trans R Soc London Ser B. 1989;324:247–265. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weathers KC, Likens GE. Environ Sci Technol. 1997;31:210–213. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bruijnzeel LA, Veneklaas EL. Ecology. 1998;79:3–9. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vester H, Lawrence D, Eastman JR, Turner BL, II, Calme S, Dickson R, Pozo C, Sangermano F. Ecol Appl. 2007;17:989–1003. doi: 10.1890/05-1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawrence D. Biotropica. 2005;37:561–570. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Szott LT, Palm CA. Plant Soil. 1996;186:293–309. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Turner BL, II, Cortina Villar S, Foster D, Geoghegan J, Keys E, Klepeis P, Lawrence D, Macario Mendoza P, Manson S, Ogneva-Himmelberger Y, et al. Forest Ecol Manage. 2001;154:353–370. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Radel C, Schmook B. Geoforum. 2008 in press. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tiessen H, Moir JO. In: Soil Sampling and Methods of Analysis. Carter MR, editor. Boca Raton, FL: Lewis; 1993. pp. 75–86. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Crews TE, Kitayama K, Fownes JH, Riley RH, Herbert DA, Mueller-Dombois D, Vitousek PM. Ecology. 1995;76:1407–1424. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Read L, Lawrence D. Ecol Appl. 2003;13:85–97. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martinez-Yrizar A. In: Seasonally Dry Tropical Forests. Bullock SH, Mooney H, Medina E, editors. New York: Cambridge Univ Press; 1995. pp. 326–345. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eaton JM, Lawrence D. Forest Ecol Manage. 2006;232:46–55. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Radulovich R, Sollins P. Biotropica. 1991;23:84–87. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Richter DD, Markewitz D, Wells CG, Allen HL, April R, Heine PR, Urrego B. Ecology. 1994;75:1463–1473. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tukey HB. In: Effects of Acid Precipitation on Terrestrial Ecosystems. Hutchinson TC, Havas M, editors. New York: Plenum; 1980. pp. 141–150. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chapin FS, Kedrowski RA. Ecology. 1983;64:376–391. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Haines B, Chapman J, Monk CD. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1985;112:258–264. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parker GG. Adv Ecol Res. 1983;13:58–133. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schaefer DA, Reiners WA. In: Acidic Precipitation. Lindberg SE, Page AL, Norton SA, editors. Vol 3. New York: Springer–Verlag; 1989. pp. 241–284. [Google Scholar]