Abstract

The group III metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (mGluR7) has been implicated in many neurological and psychiatric diseases, including drug addiction. However, it is unclear whether and how mGluR7 modulates nucleus accumbens (NAc) dopamine (DA), l-glutamate or γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), important neurotransmitters believed to be involved in such neuropsychiatric diseases. In the present study, we found that systemic or intra-NAc administration of the mGluR7 allosteric agonist N,N’-dibenzyhydryl-ethane-1,2-diamine dihydrochloride (AMN082) dose-dependently lowered NAc extracellular GABA and increased extracellular glutamate, but had no effect on extracellular DA levels. Such effects were blocked by (R,S)-α-methylserine-O-phosphate (MSOP), a group III mGluR antagonist. Intra-NAc perfusion of tetrodotoxin (TTX) blocked the AMN082-induced increases in glutamate, but failed to block the AMN082-induced reduction in GABA, suggesting vesicular glutamate and non-vesicular GABA origins for these effects. In addition, blockade of NAc GABAB receptors by 2-hydroxy-saclofen itself elevated NAc extracellular glutamate. Intra-NAc perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen not only abolished the enhanced extracellular glutamate normally produced by AMN082, but also decreased extracellular glutamate in a TTX-resistant manner. We interpret these findings to suggest that the increase in glutamate is secondary to the decrease in GABA, which overcomes mGluR7 activation-induced inhibition of non-vesicular glutamate release. In contrast to its modulatory effect on GABA and glutamate, the mGluR7 receptor does not appear to modulate NAc DA release.

Keywords: mGluR7, AMN082, dopamine, GABA, glutamate, nucleus accumbens

L-glutamate is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system (CNS), and its functions are mediated by both ionotropic and metabotropic glutamate receptors. Metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) are divided into three groups: group I (mGluR1 and mGluR5), group II (mGluR2 and mGluR3) and group III (mGluR4, mGluR6, mGluR7 and mGluR8), based upon sequence homology, intracellular signal transduction mechanisms and pharmacological properties (Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000; for review).

The mGluRs, especially the group I and group II mGluRs, have recently become attractive therapeutic targets for drug development for the treatment of CNS diseases, including drug abuse (Spooren et al., 2003; Marek, 2004; Alexander and Godwin, 2006; Witkin et al., 2007), while group III mGluRs are the least studied because of lack of selective pharmacological tools. The recent development of N,N’-dibenzyhydryl-ethane-1,2-diamine dihydrochloride (AMN082), a selective systemically active mGluR7 allosteric agonist (Mitsukawa et al., 2005), has made neuropharmacological and neurochemical studies of mGluR7 functions in the CNS feasible. In vitro cAMP and GTPγS binding assays in recombinant cells expressing mGluR7 demonstrate that AMN082 is a potent (EC50 64-290 nM) and selective (at least 30-150-fold) allosteric agonist of mGluR7 over other mGluR subtypes and some iGluRs (EC50 >10 μM) (Mitsukawa et al., 2005). It was recently reported that systemic administration of AMN082 inhibits acquisition of Pavlovian fear conditioning (Fendt et al., 2007), susceptibility to seizures (Sansig et al., 2001), animal analogs of anxiety and depression (Callaerts-Vegh et al., 2006; Palucha et al., 2007), and both cocaine self-administration and reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior (Li et al., 2006). However, the cellular mechanisms underlying such actions are poorly understood.

Given the important role of brain DA, l-glutamate and GABA transmission in many neuropsychiatric diseases (Spooren et al., 2003; Marek, 2004; Wise, 2005; Alexander and Godwin, 2006; Witkin et al., 2007), studies of the possible modulation of such neurotransmission by mGluR7 seem called for. Previous studies have shown that local perfusion of l-2-amino-4-phospho-nobutyrate (L-AP4), a non-selective group III mGluR (mGluR4, mGluR6, mGluR7 and mGluR8) agonist, lowered extracellular DA, glutamate, and GABA levels in many brain regions, including the NAc (Anwyl 1999; Hu et al., 1999; Panatier et al., 2004; Xi et al., 2003; Kogo et al., 2004; Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000 for review). In contrast, other reports indicated that activation of group III mGluRs by L-AP4 increased glutamatergic transmission in entorhinal cortex (Evans et al., 2000) and periaqueductal grey (Marabese et al., 2005). These data suggest that glutamate transmission in different brain loci may be modulated differently by group III mGluRs.

Anatomic evidence demonstrates that mGluR7 has the highest CNS density of all group III mGluR subtypes (Shigemoto et al., 1997; Bradley et al., 1998; Corti et al., 1998; Kinoshita et al., 1998). The most intense expression is seen in the olfactory bulb, hippocampus, dorsal striatum and NAc (Ferraguti and Shigemoto, 2006). Further, immunohistochemical and electromicroscopic studies demonstrate that mGluR7 is located predominantly on presynaptic terminals of glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons (Shigemoto et al., 1996; Bradley et al., 1996; Dalezios, 2002; Somogyi, 2003; Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000 for review). These data suggest that mGluR7 may play an important role in modulating glutamate and GABA release in those brain regions. However, research on this topic has been hampered by lack of selective mGluR7 agonists or antagonists. Given the important role of the NAc in emotion, motivation, brain reward, and drug addiction (Wise, 2005), we investigated the effects of AMN082, a selective mGluR7 allosteric agonist (Mitsukawa et al., 2005), on extracellular DA, l-glutamate and GABA in the NAc by in vivo brain microdialysis. The research was undertaken in the hope that information on the role of AMN082 on NAc DA, l-glutamate and GABA may shed light on the potential utility of AMN082 in the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases and/or drug addiction.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Long-Evans rats (Charles River Laboratories, Raleigh, NC) weighing 250 to 300 g were used. They were housed individually in a climate-controlled animal room on a reversed light-dark cycle with free access to food and water. The animals were maintained in a facility fully accredited by the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International. All experimental procedures were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the U.S. National Academy of Sciences (National Research Council, Commission on Life Sciences, Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources) and were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the U.S. National Institutes of Health.

Surgery

All rats were bilaterally implanted with intracranial guide cannulae (20 gauge, 14 mm; Plastics One, Roanoke, VA) into the NAc for in vivo microdialysis. The sugery was performed under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia (65 mg/kg i.p.) with standard aseptic surgical and stereotaxic technique. The stereotaxic coordinates for the NAc were +1.7 mm anterior to Bregma, ±2.0 mm mediolateral, -4.0 mm ventral to the skull surface according to the atlas of Paxinos and Watson (1986) using an approach angle of 6° from vertical. The guide cannulae were fixed to the skull with 4 stainless steel skull screws (Small Parts Inc., Miami Lakes, FL) and dental acrylic.

In vivo Microdialysis

In vivo microdialysis was performed in freely moving animals 5-7 days after intracranial surgery. Dialysis probes were constructed as described before (Xi et al., 2003). The active region of the dialysis membrane was 1.0 mm in length, approximately 100 μm in diameter. Probes were inserted into the NAc at least 12 hours before the experiments to minimize damage-induced DA, glutamate or GABA release during the experiment. On the day of the experiment, dialysis buffer (5 mM glucose, 2.5 mM KCl, 140 mM NaCl, 1.4 mM CaCl2, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 0.15% phosphate buffered saline, pH 7.4) was perfused through the probe (2.0 μl/min) via syringe pump (Bioanalytical Systems, Inc. West Lafayette, IN) beginning at least 2 hr prior to sample collection. Dialysis samples were collected every 20 min into 10 μl 0.5 M perchloric acid to prevent degradation of neurotransmitters. After 1 hr of baseline collection, various drugs were administered systemically or locally infused into the NAc by reverse microdialysis. After collection, all samples were frozen at -80°C until analyzed.

Quantification of DA

Dialysate DA was measured with the ESA electrochemical detection system (ESA Inc., Chelmsford, MA). The DA mobile phase contained 4.76 mM citric acid, 150 mM Na2HPO4, 3 mM sodium dodecyl sulfate, 50 mM EDTA, 10% methanol, and 15% acetylnitrile, pH5.6. DA was separated using an ESA MD-150 × 3.2 mm reverse phase column and oxidized/reduced using an ESA Coulochem III detector. Three electrodes were used: a pre-injection port guard cell (+0.25 V) to oxidize the mobile phase, an oxidation analytical electrode (E1, -0.1V), and a reduction analytical electrode (E2, 0.2 V). The area under curve (AUC) of the DA peak was measured using an “EZChrom Elite” ESA chromatography data system. DA values were quantified with an external standard curve (1-1000 fM).

Quantification of Glutamate and GABA

Concentrations of glutamate and GABA in the dialysis samples were determined using high pressure liquid chromatography with flourometric detection. The mobile phase consisted of 18% acetylnitrile (v/v), 100 mM Na2HPO4, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 6.04. A reverse-phase column (RP-18, 10 cm × 3 μm ODS, Bioanalytical systems Inc., West Lafayette, IN) was used to separate the amino acids, and precolumn derivatization of amino acids with o-phthalaldehyde was performed using an ESA Model 542 autosampler (ESA Inc. Chelmsford, MA). Glutamate and GABA were detected by a fluorescence spectrophotometer (LC 530, from ESA Inc.). Two sets of different excitation wavelengths (Exλ) and emission wavelengths (Emλ) were used to simultaneously measure glutamate (Exλ, 314 nm; Emλ, 394 nm) and GABA (Exλ, 336 nm; Emλ, 420 nm) levels from the same samples. The AUCs of the glutamate and GABA peaks were measured using an “EZChrom Elite” ESA chromatography data system. Glutamate and GABA values were quantified with external standard curves (glutamate: 0.1-5 μM; GABA: 0.01-1 μM). The limits of detection for glutamate and GABA were 1-2 pM and 0.1-1 pM, respectively.

Drugs

AMN082 [N,N’-dibenzyhydryl-ethane-1,2-diamine dihydrochloride], MSOP [(R,S)-α-methylserine-o-phosphate], tetrodotoxin (TTX) and 2-hydroxy-saclofen were purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). For intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection, AMN082 was dissolved in 0.5% Tween-80 (Sigma-RBI, St. Louis, MO). The i.p. injection volumes of AMN082 solution were between 0.5-1.0 ml. For local NAc perfusion, all drugs were dissolved in the dialysis buffer described above.

Histology

Following microdialysis, rats were euthanized by pentobarbital overdose (>100mg/kg i.p.) and perfused transcardially with 0.9% saline followed by 10% formalin. Brains were removed and placed in 10% formalin for 1 week. The tissue was blocked around the NAc and coronal sections (100 μm thick) made by vibratome. The sections were stained with cresyl violet and examined by light microscopy. Animals with cannula locations outside the NAc were excluded from data analysis.

Data analyses

Drug-induced changes in extracellular DA, glutamate or GABA levels are calculated and expressed as % changes of the mean values of 3 baselines immediately before drug administration. All data are presented as means ± S.E.M.. Two-way (treatment vs. time) analysis of variance (ANOVA) with repeated measures over time was used to analyze data reflecting time courses of neurochemical changes after drug administration (Figures 1, 2, 3, 4, 5). Post-ANOVA pre-planned individual group comparisons were carried out using the Bonferroni statistical procedure.

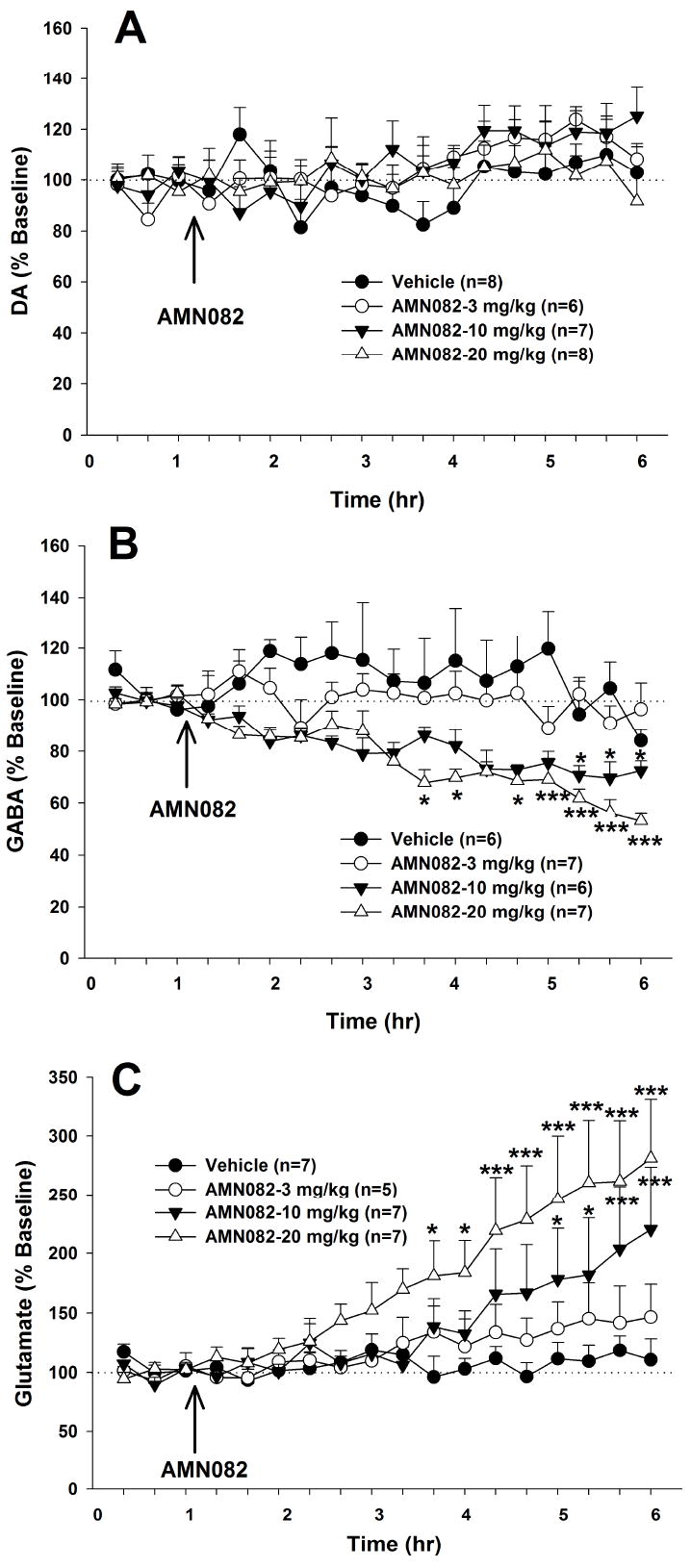

Figure 1.

Effects of systemic administration of AMN082 on extracellular DA, GABA and glutamate levels in the NAc. AMN082 (3-20 mg/kg, i.p.) had no effect on extracellular DA (Panel A), but dose-dependently decreased extracellular GABA (Panel B) and increased extracellular glutamate (Panel C) in the NAc. *p<0.05, ***p<0.001, compared with the baseline of each treatment group.

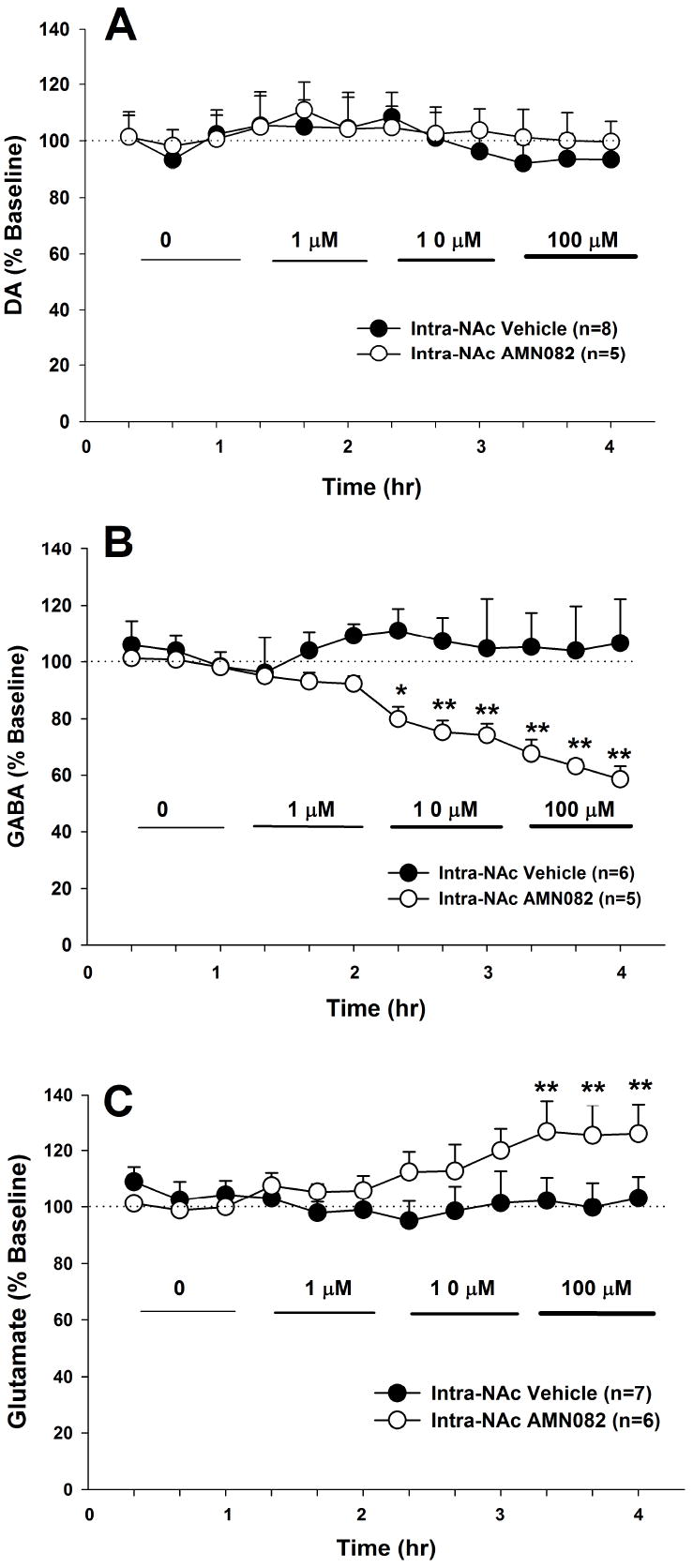

Figure 2.

Effects of local administration of AMN082 on extracellular DA, GABA and glutamate levels in the NAc. Local perfusion of AMN082 (1-100 μM) into the NAc failed to alter extracellular DA levels (Panel A), but dose-dependently lowered extracellular GABA (Panel B) and increased extracellular glutamate (Panel C) in the NAc. * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, compared with the baseline of each treatment group.

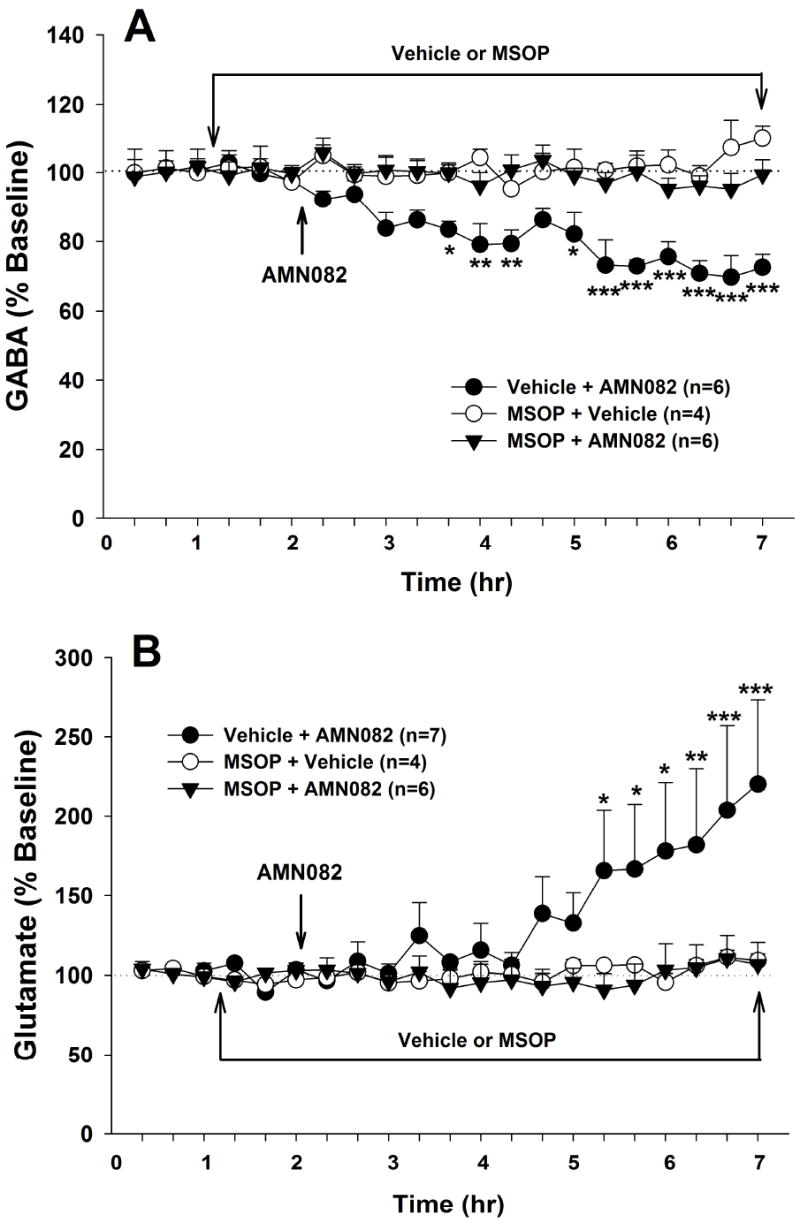

Figure 3.

Effects of the group III mGluR antagonist MSOP on AMN082-induced changes in NAc GABA and glutamate. Local perfusion of MSOP (100 μM) into the NAc completely blocked AMN082 (10 mg/kg)-induced decreases in GABA (Panel A) and increases in glutamate (Panel B), while MSOP alone had no effect on NAc GABA and glutamate. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared with the baseline of each treatment group.

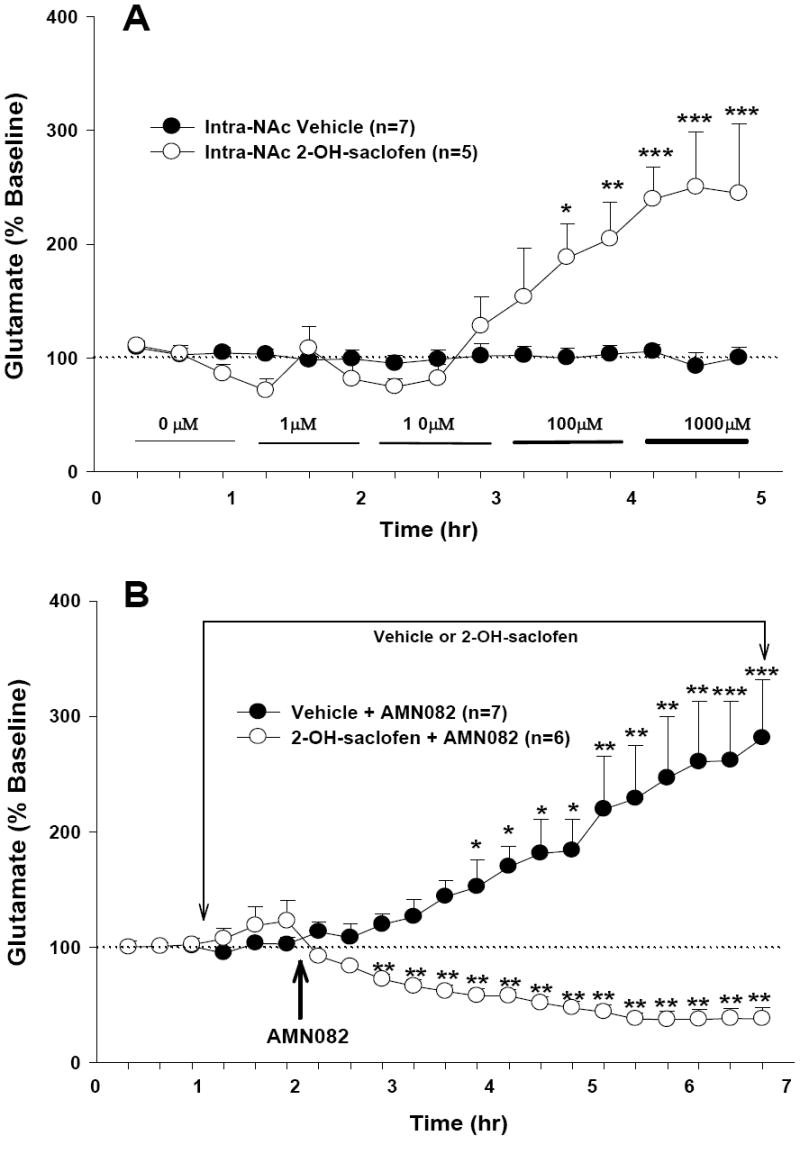

Figure 4.

Effects of the GABAB receptor antagonist 2-hydroxy-saclofen (2-OH-saclofen) on AMN082-induced increases in extracellular NAc glutamate. Local perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen (1-1000 μM) by itself into the NAc significantly increased basal levels of extracellular NAc glutamate (Panel A). However, in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen, AMN082 produced a decrease in extracellular glutamate (Panel B). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, compared with the baseline in each treatment group.

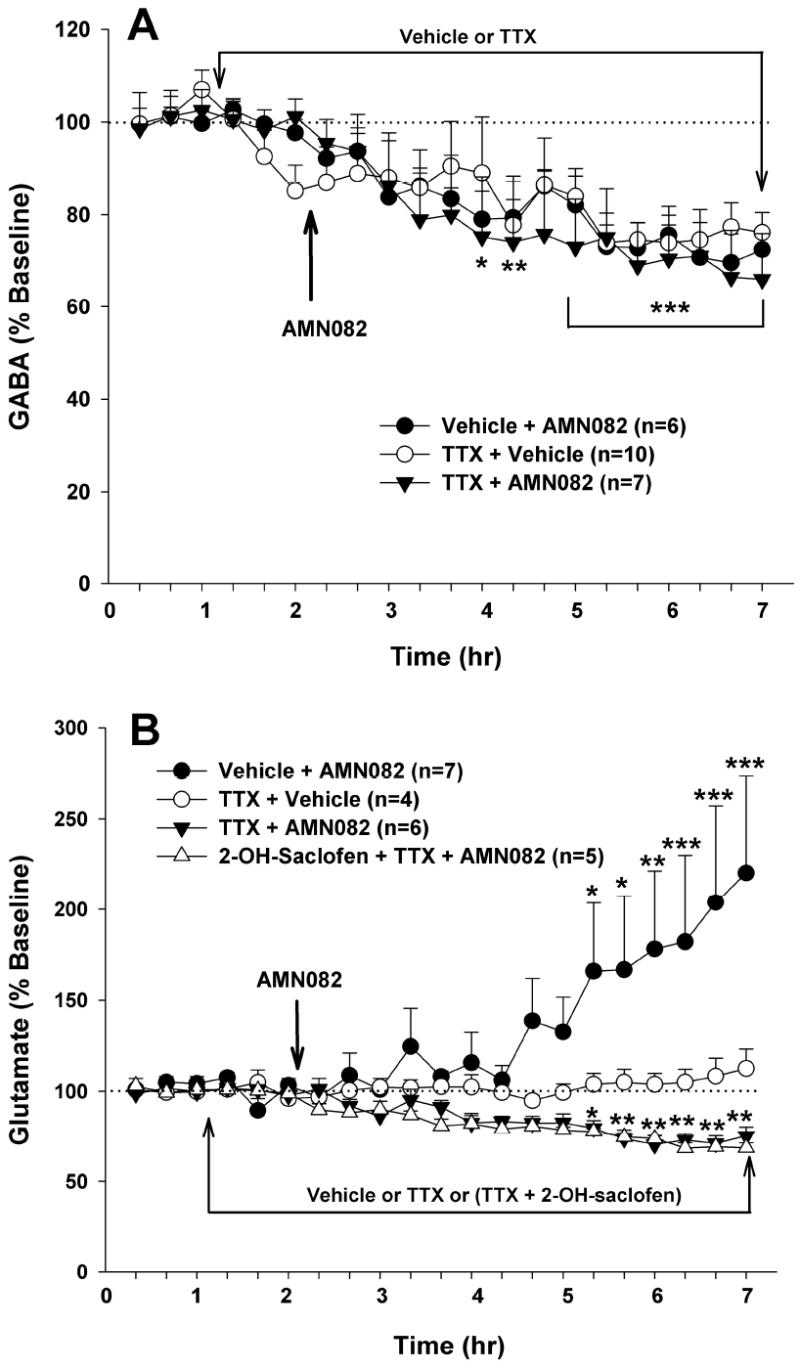

Figure 5.

Effects of the voltage-dependent Na+ channel blocker tetrodotoxin (TTX) on AMN082-induced changers in NAc GABA and glutamate. Intra-NAc TTX (1 μM) alone significantly lowered extracellular GABA levels (Panel A), but failed to alter extracellular glutamate levels (Panel B). Intra-NAc TTX (1 μM) failed to alter AMN082 (10 mg/kg)-induced decreases in NAc GABA (Panel A) or glutamate in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen (100 μM, Panel B), but blocked AMN082-induced increases in NAc glutamate seen in the absence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen. *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001, when compared with the baseline in each treatment group.

RESULTS

Effects of systemic administration of AMN082 on extracellular DA, GABA and glutamate in the NAc

Basal levels of NAc extracellular DA (0.37 ± 0.05 nM), l-glutamate (0.77 ± 0.11 μM) and GABA (138.92 ± 15.75 nM) did not differ significantly among the different groups of rats. Systemic administration of AMN082 (3, 10, 20 mg/kg i.p.) failed to alter extracellular DA levels in the NAc (Figure 1A). Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time revealed statistically a significant difference only in the time main effect (F17,425=2.39, p<0.01), but not in the treatment main effect (F3,25=0.89, p>0.05), or in the treatment × time interaction (F51,425=1.28, p>0.05). In contrast, the same doses of AMN082 dose-dependently decreased extracellular GABA (Figure 1B) and increased extracellular glutamate levels in the NAc (Figure 1C). At the highest concentration (20 mg/kg, i.p.), AMN082 produced an approximate 50% reduction in extracellular GABA and an approximate 250% increase in extracellular glutamate in the NAc at 5 hr after AMN082 administration. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the data shown in Figure 1B revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F3,22=7.72, p<0.001), time main effect (F17,374=6.65, p<0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F51, 374=1.75, p<0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed statistically significant decreases in GABA after administration of AMN082 at 10 mg/kg or 20 mg/kg, but not after 3 mg/kg (see significance levels for specific individual inter-group comparisons indicated on Figure 1B). Similarly, two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the glutamate data shown in Figure 1C revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F3,22=3.29, p<0.05), time main effect (F17,374=12.67, p<0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F51, 374=2.69, p<0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed statistically significant increases in glutamate after 10 mg/kg, 20 mg/kg, but not 3 mg/kg AMN082 administration (see significance levels for specific individual inter-group comparisons indicated on Figure 1C).

Effects of local perfusion of AMN082 into the NAc on extracellular DA, GABA and glutamate

To determine whether the effects observed above were mediated by action on mGluR7 receptors located in the NAc, different concentrations of AMN082 (1-100 μM) were locally infused into the NAc. Consistent with the effects after systemic administration, local perfusion of AMN082 failed to alter NAc DA (Figure 2A), but significantly decreased extracellular GABA (Figure 2B) and increased extracellular glutamate (Figure 2C) in a concentration-dependent manner. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over increasing concentrations of locally infused AMN082 for the DA data (Figure 2A) revealed no statistically significant treatment main effect (F1,11=0.76, p>0.05). On the other hand, two-way ANOVA for the GABA data, shown in Figure 2B, revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F1,9=7.48, p<0.05), time main effect (F11,99=2.4, p<0.05), and treatment × time interaction (F11,99=2.54, p<0.01). Post-ANOVA individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed statistically significant decreases in GABA after 10 μM or 100 μM (but not 1 μM) AMN082, when compared with baseline before AMN082 administration. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the glutamate data, shown in Figure 2C, revealed a statistically significant main effect (F1,11=2.86, p<0.05), time main effect (F11,121=1.88, p<0.05), and treatment × time interaction (F11, 121=2.34, p<0.05). Individual group comparisons revealed statistically significant increases in extracellular glutamate after 100 μM (but not 1 or 10 μM) AMN082, when compared with baseline before AMN082 administration.

Effects of the group III mGluR antagonist MSOP on AMN082-induced changes in extracellular GABA and glutamate

To determine whether the AMN082-induced changes in NAc GABA and glutamate are truly mediated by group III mGluR7 action, we observed the effects of group III mGluR antagonism on AMN082-induced changes in GABA and glutamate. Local perfusion of MSOP (100 μM) alone did not significantly alter extracellular NAc GABA or glutamate (Figure 3), suggesting the existence of low glutamate tone on NAc group III mGluRs. However, under continuous local perfusion conditions, MSOP completely blocked the 10 mg/kg AMN082-induced decrease in GABA (Figure 3A) and the AMN082-induced increase in glutamate (Figure 3B). Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the data shown in Figure 3A revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F2,13=44.49, p<0.001), time main effect (F17,221=2.79, p<0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F34,221=2.70, p<0.001). Two-way ANOVA for the glutamate data shown in Figure 3B revealed a statistically significant time main effect (F17,238=3.04, p<0.001) and treatment × time interaction (F34,238=2.25, p<0.001), but not treatment main effect (F2,14=2.71, p>0.05). Individual treatment group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed that AMN082-induced changes in GABA and glutamate were significantly blocked by MSOP (see significance levels indicated directly on Figures 3A and 3B).

Effects of the GABAB receptor antagonist 2-hydroxy-saclofen on AMN082-induced increases in glutamate

It is well documented that mGluR7 is a Gi protein-coupled receptor and that its main effect is inhibition of neuronal activity or neurotransmitter release (Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000). We hypothesized that AMN082-induced increases in glutamate may be secondary to a reduction in extracellular GABA levels, which leads to a disinhibition of glutamate release via presynaptic GABAB receptors. To test this hypothesis, the GABAB receptor antagonist 2-hydroxy-saclofen was locally perfused into the NAc to block NAc GABAB receptors. We found that local perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen (1-1000 μM) alone significantly increased extracellular glutamate levels in a concentration-dependent manner (Figure 4A), suggesting the existence of inhibitory GABA tone on NAc glutamate release. Two-way ANOVA for the data shown in Figure 4A revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F1,10=11.32, p<0.01), time main effect (F14,140=11.02, p<0.001), and treatment × time interaction (F14,140=11.28, p<0.001). However, in the presence of continuous local perfusion of 2-OH-saclofen, AMN082 (20 mg/kg i.p.) produced a significant reduction in extracellular glutamate, opposite to the increase observed in the absence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen (Figure 4B). Two-way ANOVA for the data shown in Figure 4B revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F1,11=12.61, p<0.01) and treatment × time interaction (F17,186=8.08, p<0.001), but not time main effect (F17,186=1.35, p>0.05). Post-ANOVA individual group comparisons indicated that AMN082-induced increases or decreases in the absence or presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen, respectively, were statistically significant when compared with the baseline before AMN082 administration (see significance levels indicated directly on Figures 4A and 4B).

Effects of the voltage-dependent Na+-channel blocker TTX on AMN082-induced changes in NAc GABA and glutamate

Finally, to determine vesicular and/or non-vesicular origins, we observed the effects of local perfusion of TTX on AMN082-induced changes in GABA and glutamate. TTX (1 μM) alone did not significantly alter extracellular glutamate (Figure 5B), but decreased extracellular GABA (~ 30%, Figure 5A). However, local perfusion of TTX (1 μM) failed to block AMN082 (10 mg/kg)-induced decreases in NAc GABA (Figure 5A), suggesting non-vesicular origins of the extracellular GABA. Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the GABA data shown in Figure 5A revealed a statistically significant time main effect (F17,340=9.21, p<0.001), but no significant treatment main effect (F2,20=0.16, p>0.05) and no significant treatment × time interaction (F34,340=0.50, p>0.05). In contrast to the effects on NAc GABA, intra-NAc TTX blocked AMN082-induced increases in glutamate observed in the absence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen, but failed to block the AMN082-induced decreases in glutamate observed in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen (Figure 5B). Two-way ANOVA with repeated measurements over time for the glutamate data shown in Figure 5B revealed a statistically significant treatment main effect (F3,18=4.45, p<0.05) and a significant treatment × time interaction (F51,306=3.88, p<0.001). Individual group comparisons using the Bonferroni test revealed that both the AMN082-induced increase or decrease in NAc glutamate in the absence or presence of TTX or TTX plus 2-hydroxy-saclofen, respectively, were statistically significant, when compared with the baselines before AMN082 administration.

Histological examinations

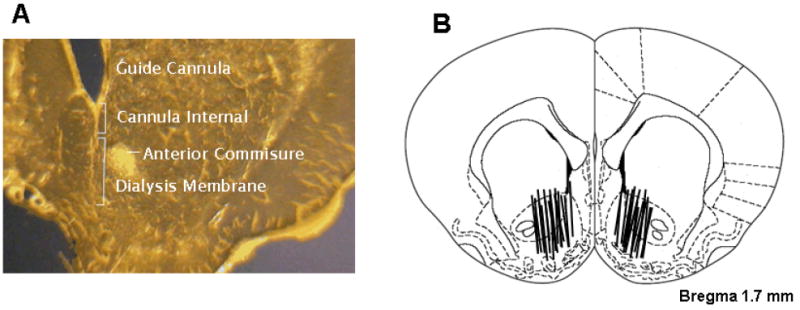

Figure 6A shows a representative microdialysis probe position in rat brain, demonstrating that the active membrane portion of the probe, below the non-membrane (stainless steel) portion, was located in the NAc. Figure 6B shows a depiction of all microdialysis probe locations (active dialysis membranes) in the NAc. The active membranes of the dialysis probes were located within both the core and shell. There were no obvious differences in placements of the dialysis probes across the different experimental groups of rats.

Figure 6.

Panel A: Photomicrograph of a stained coronal brain section demonstrating the position and extent of a representative guide cannula and representative microdialysis probe, including the non-membrane portion (~1 mm beyond the tip of the guide cannula) and the active membrane portion. Panel B: Schematic reconstructions of positions of active microdialysis membranes within the NAc. Dialysis membranes tended to span the length of the core and shell compartments of the NAc.

DISCUSSION

The present study, for the first time, demonstrates that systemic or local administration of the selective mGluR7 agonist AMN082 into the NAc dose-dependently decreases extracellular GABA, increases extracellular glutamate, but has no effect on extracellular DA in the NAc. The group III mGluR antagonist MSOP (Thomas et al., 1996), when locally perfused into the NAc, blocked AMN082-induced changes in NAc GABA and glutamate, suggesting effects mediated by activation of NAc group III mGluR7 receptors. Further, the increase in NAc glutamate appears to be secondary to a reduction in NAc GABA levels. This is supported by the finding that local perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen, a selective GABAB receptor antagonist (Kerr et al., 1988), increased extracellular glutamate, while intra-NAc perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen blocked AMN082-induced increases in NAc glutamate. Further, intra-NAc 2-hydroxy-saclofen reversed the action of AMN082, i.e., AMN082 lowered NAc glutamate in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen. The voltage-dependent Na+ channel blocker TTX selectively blocked the AMN082-induced increase in glutamate, but not the decrease in GABA or glutamate. These data suggest that the AMN082-enhanced glutamate was derived from action potential-dependent vesicular sources, while the decreased GABA and glutamate (in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen) were derived from action potential-independent non-vesicular sources. Together, these data suggest that mGluR7 plays an important role in the modulation of NAc GABA and glutamate, but not of DA.

Strikingly, AMN082-induced changes in extracellular GABA and glutamate display a slow-onset and long-acting (at least 5 hr) profile. The underlying mechanisms remain unclear. It might be related to AMN082’s binding and action on an allosteric mGluR7 site and/or AMN082’s pharmacokinetic properties. This slow-onset and long-acting property may also explain why AMN082-induced increases (~20%) in NAc glutamate observed during local perfusion (1 hr at each concentration) were much lower than those observed 5 hr after systemic administration (100-250%) (see Figures 1-2). Overall, these findings are consistent with the cellular distributions of mGluR7 on presynaptic GABA and glutamate, but not DA, terminals in many brain regions (Bradley et al., 1996; Shigemoto et al., 1997; Wada et al., 1998; Kinoshita et al., 1998; Kosinski et al., 1999; Kogo et al., 2004). Moreover, mGluR7 receptors have been shown to be located exclusively within active presynaptic zones of axon terminals (Shigemoto et al., 1996; Dalezios et al., 2002; Somogyi et al., 2003), suggesting that mGluR7 may functionally act as an autoreceptor regulating glutamate release, or as a heteroreceptor regulating the release of GABA.

Previous in vitro electrophysiological studies have shown that activation of group III mGluRs by L-AP4 produces an inhibitory effect on GABA release in such brain regions as hippocampus (Desai et al., 1994; Gereau and Conn, 1995; Kogo et al., 2004), striatum (Lafon-Cazal et al., 1999), substantia nigra (Wittmann et al., 2001) and cerebral cortex (Schaffhauser et al., 1998). However, the receptor subtype mechanism has remained unclear because L-AP4 is a non-selective group III mGluR agonist. The present study demonstrates that activation of mGluR7 by the selective agonist AMN082 produces a similar inhibitory effect on NAc GABA release, suggesting that mGluR7 may be involved in L-AP4’s action on striatal GABA release. Further, local perfusion of the group III mGluR antagonist MSOP completely blocked AMN082-induced reduction in NAc GABA levels, supporting an effect mediated by group III mGluR7s. This is consistent with a recent finding that intra-periaqueductal gray perfusion of MSOP blocked AMN082-induced inhibition of neuronal and behavioral responses to nociceptive stimuli, as well as GABA and glutamate release in the ventromedial medulla (Marabese et al., 2007). We note the reports that MSOP does not block the actions of AMN082 in in vitro cell lines that express fragments of mGluR7 (Mitsukawa et al., 2005; Pelkey et al., 2007). It seems not unlikely that such mGluR7 fragments may have low sensitivity to MSOP due to loss of receptor integrity or altered receptor configuration.

Two mechanisms are believed to underlie extracellular GABA origins. One is Ca++-dependent vesicular release evoked by depolarization-induced neuronal activation (Haugstad et al., 1992), and another is Ca++-independent non-vesicular GABA release from neuronal and/or glial sources mediated by reversal of GABA transporters (Attwell et al., 1993; Levi and Raiteri, 1993). Further, it has been reported that glutamate may stimulate non-vesicular GABA release by activation of both N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) and non-NMDA receptors (Belhage et al., 1993; Liu et al., 2006). To further explore the origins of the mGluR7-modulated GABA, we perfused TTX, a voltage-dependent Na+ channel blocker, locally into the NAc to block action potential propagation and subsequent activation of voltage-dependent Ca++ channels. We found that TTX failed to block the AMN082-induced decrease in extracellular GABA levels. These data suggest that mGluR7-induced reduction in NAc GABA is derived predominantly from non-vesicular origins.

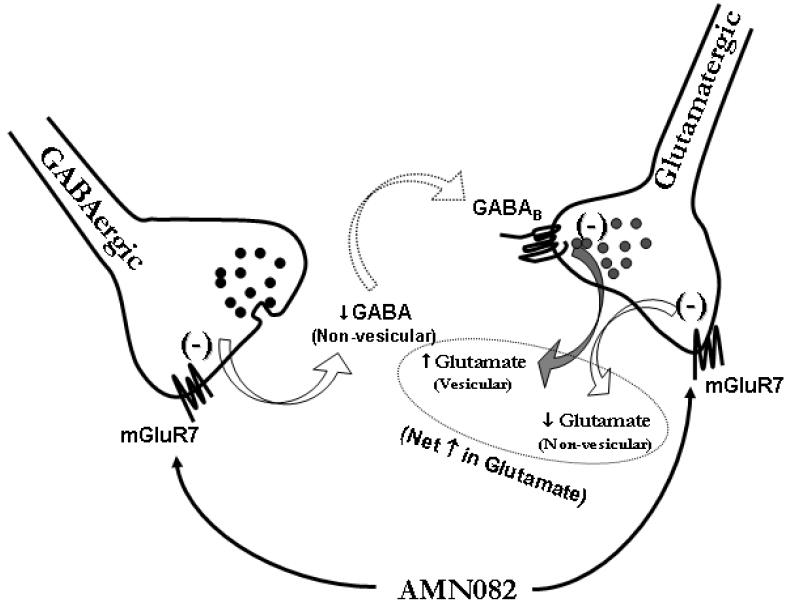

In contrast to the reduction in NAc GABA levels, systemic or local administration of AMN082 increased NAc extracellular glutamate. This is consistent with the finding that L-AP4 increases glutamate release in entorhinal cortex (Evans et al., 2000) and periaqueductal grey (Marabese et al., 2005), but conflicts with other findings that L-AP4 inhibits glutamate release in the NAc (Manzoni et al., 1997; Martin et al., 1997; Xi et al., 2003) and other brain regions (see review by Cartmell and Schoepp, 2000). Given that GABA exerts inhibitory control over NAc glutamate release via presynaptic GABAB receptors (Takahashi et al., 1998; Lei et al., 2003; Xi et al., 2003; Porter et al., 2004; Sun et al., 2006), we hypothesized that AMN082-induced reduction in extracellular GABA levels may lower GABA tone on GABAB receptors located on glutamatergic terminals, leading to an increase (i.e., disinhibition) in NAc extracellular glutamate. To test this hypothesis, 2-hydroxy-saclofen, a selective GABAB receptor antagonist (Kerr et al., 1988), was locally infused into the NAc. We found that such local perfusion significantly increased NAc extracellular glutamate levels in a concentration-dependent manner, suggesting significant GABA tone on glutamate release mediated via presynaptic GABAB receptors. Moreover, local perfusion of 2-hydroxy-saclofen not only completely blocked AMN082-induced glutamate enhancement, but also reversed AMN082’s action, i.e., changed the glutamate enhancement to glutamate inhibition. These findings suggest that, first, AMN082-induced increases in NAc glutamate are mediated by AMN082-induced reduction in NAc GABA levels; and second, AMN082 actually produces two opposite actions on NAc extracellular glutamate, i.e., direct inhibition (observed in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen) and an indirect disinhibition (observed in the absence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen). Thus, the observed increases in glutamate appear to be a final net effect of these two opposite actions resulting from mGluR7 activation (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Hypothetical mechanisms of mGluR7 actions on NAc GABA and glutamate release. mGluR7 has been shown to be located on glutamatergic and GABAergic terminals in many brain regions, including dorsal striatum and NAc. Activation of mGluR7 located on GABAergic terminals inhibits non-vesicular GABA release via Gi-protein coupled mechanisms. Such a reduction in extracellular GABA levels lowers GABA tone on GABAB receptors located on glutamatergic terminals, which leads to disinhibition of (i.e., an increase in) vesicular glutamate release. Similarly, activation of mGluR7 located on glutamatergic terminals also inhibits non-vesicular glutamate release by a Gi-coupled intracellular mechanism. Thus, the increase in extracellular glutamate observed in the present study appears to be the final net effect of both direct inhibition and indirect disinhibition after mGluR7 activation by AMN082 administration.

Another important finding is that the voltage-dependent Na+ channel inhibitor TTX selectively blocked AMN082-induced increases in glutamate, but failed to block AMN082-induced reductions in NAc glutamate observed in the presence of 2-hydroxy-saclofen. The first finding suggests that the increased NAc glutamate, mediated by GABAB receptor disinhibition, is derived from action potential-dependent vesicular glutamate sources. This is congruent with previous reports that GABAB receptors inhibit vesicular glutamate release predominantly by inhibiting presynaptic calcium influx (Isaacson, 1998; Takahashi et al., 1998). The second finding suggests that mGluR7 also inhibits action potential-independent, non-vesicular glutamate release. This is consistent with our finding that mGluR7 activation inhibits non-vesicular GABA release (present study) and a previous finding that activation of group III mGluRs by L-AP4 inhibits non-vesicular glutamate release in the NAc (Xi et al., 2003). In addition, electrophysiological evidence shows that Ca++ channel blockers fail to block L-AP4-induced inhibition of excitatory synaptic transmission in the NAc (Manzoni et al., 1997).

Finally, we found that the mGluR7 agonist AMN082 failed to alter NAc extracellular DA, which appears to conflict with previous reports that activation of group III mGluRs by L-AP4 inhibited DA release in the NAc (Hu et al., 1999) and dorsal striatum (Mao et al., 2000). Given that L-AP4 is a non-selective group III mGluR agonist and has highest binding affinity for mGluR8 and lowest affinity for mGluR7, it is likely that such a reduction in DA was mediated by activation of mGluR8, rather than mGluR7. However, as we have reported previously, NAc GABA also exerts inhibitory control on presynaptic DA release (Xi et al., 2003). Based on this, AMN082-induced reduction in GABA release should produce an increase in NAc DA, via GABAB receptor-mediated disinhibition. However, in the present experiments we did not see a significant alteration in NAc DA after AMN082 administration. This is consistent with our recent finding that γ-vinyl GABA, a GABA degradation enzyme inhibitor, significantly elevated NAc extracellular GABA levels, but failed to alter extracellular NAc DA levels (Peng et al., 2007). Clearly, more studies are required to resolve these apparent inconsistencies and to further study whether and how non-vesicular GABA modulates DA release in the NAc.

In conclusion, the present in vivo microdialysis study demonstrates that mGluR7 activation produces an inhibitory effect on non-vesicular GABA and glutamate release in the NAc and an indirect increase in vesicular glutamate release in the NAc via a GABAergic disinhibitory mechanism. Given that mGluR7-knockout mice display increased seizure susceptibility (Sansig et al., 2001), impaired working memory and reduced anxiety-like behavior (Callaerts-Vegh et al., 2006), better understanding of mGluR7 involvement in GABA or glutamate synaptic transmission may provide insight into the role of mGluR7 receptors in neuropsychiatric diseases. Further, NAc GABA and glutamate transmission have been thought to play an important role both in drug reward and relapse to drug-seeking behavior (Kalivas, 2004; Everitt and Robbins, 2005; Xi et al., 2003). Thus, the present findings suggest that novel compounds that target the mGluR7 may have pharmacotherapeutic potential in the treatment of both neuropsychiatric diseases and drug addiction.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute on Drug Abuse, National Institutes of Health.

References

- Alexander GM, Godwin DW. Metabotropic glutamate receptors as a strategic target for the treatment of epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2006;71:1–22. doi: 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anwyl R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors: electrophysiological properties and role in plasticity. Brain Res Rev. 1999;29:83–120. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(98)00050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attwell D, Barbour B, Szatkowski M. Nonvesicular release of neurotransmitter. Neuron. 1993;11:401–407. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(93)90145-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belhage B, Hansen GH, Schousboe A. Depolarization by K+ and glutamate activates different neurotransmitter release mechanisms in GABAergic neurons: vesicular versus non-vesicular release of GABA. Neuroscience. 1993;54:1019–1034. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(93)90592-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Levey AI, Hersch SM, Conn PJ. Immunocytochemical localization of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the hippocampus with subtype-specific antibodies. J Neurosci. 1996;16:2044–2056. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-06-02044.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley SR, Rees HD, Yi H, Levey AI, Conn PJ. Distribution and developmental regulation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7a in rat brain. J Neurochem. 1998;71:636–645. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71020636.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callaerts-Vegh Z, Beckers T, Ball SM, Baeyens F, Callaerts PF, Cryan JF, Molnar E, D’Hooge R. Concomitant deficits in working memory and fear extinction are functionally dissociated from reduced anxiety in metabotropic glutamate receptor 7-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6573–6582. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1497-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cartmell J, Schoepp DD. Regulation of neurotransmitter release by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Neurochem. 2000;75:889–907. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0750889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corti C, Restituito S, Rimland JM, Brabet I, Corsi M, Pin JP, Ferraguti F. Cloning and characterization of alternative mRNA forms for the rat metabotropic glutamate receptors mGluR7 and mGluR8. Eur J Neurosci. 1998;10:3629–3641. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1998.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalezios Y, Luján R, Shigemoto R, Roberts JDB, Somogyi P. Enrichment of mGluR7a in the presynaptic active zones of GABAergic and non-GABAergic terminals on interneurons in the rat somatosensory cortex. Cereb Cortex. 2002;12:961–974. doi: 10.1093/cercor/12.9.961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai MA, McBain CJ, Kauer JA, Conn PJ. Metabotropic glutamate receptor-induced disinhibition is mediated by reduced transmission at excitatory synapses onto interneurons and inhibitory synapses onto pyramidal cells. Neurosci Lett. 1994;181:78–82. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(94)90564-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans DI, Jones RSG, Woodhall G. Activation of presynaptic group III metabotropic receptors enhances glutamate release in rat entorhinal cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2000;83:2519–2525. doi: 10.1152/jn.2000.83.5.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fendt M, Schmid S, Thakker DR, Jacobson LH, Yamamoto R, Mitsukawa K, Maier R, Natt F, Hüsken D, Kelly PH, McAllister KH, Hoyer D, van der Putten H, Cryan JF, Flor PJ. mGluR7 facilitates extinction of aversive memories and controls amygdala plasticity. Mol Psychiatry. 2007 doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4002073. 21 Aug 07, Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferraguti F, Shigemoto R. Metabotropic glutamate receptors. Cell Tissue Res. 2006;326:483–504. doi: 10.1007/s00441-006-0266-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gereau RW, IV, Conn PJ. Roles of specific metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in regulation of hippocampal CA1 pyramidal cell excitability. J Neurophysiol. 1995;74:122–129. doi: 10.1152/jn.1995.74.1.122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haugstad TS, Hegstad E, Langmoen IA. Calcium dependent release of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) from human cerebral cortex. Neurosci Lett. 1992;141:61–64. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(92)90334-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu G, Duffy P, Swanson C, Ghasemzadeh MB, Kalivas PW. The regulation of dopamine transmission by metabotropic glutamate receptors. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:412–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isaacson JS. GABAB receptor-mediated modulation of presynaptic currents and excitatory transmission at a fast central synapse. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:1571–1576. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.3.1571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalivas PW. Glutamate systems in cocaine addiction. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:23–29. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerr DIB, Ong J, Johnston GAR, Abbenante J, Prager RH. 2-Hydroxy-saclofen: an improved antagonist at central and peripheral GABAB receptors. Neurosci Lett. 1988;92:92–96. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(88)90748-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita A, Shigemoto R, Ohishi H, van der Putten H, Mizuno N. Immunohistochemical localization of metabotropic glutamate receptors, mGluR7a and mGluR7b, in the central nervous system of the adult rat and mouse: a light and electron microscopic study. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:332–352. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogo N, Dalezios Y, Capogna M, Ferraguti F, Shigemoto R, Somogyi P. Depression of GABAergic input to identified hippocampal neurons by group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat. Eur J Neurosci. 2004;19:2727–2740. doi: 10.1111/j.0953-816X.2004.03394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosinski CM, Risso Bradley S, Conn PJ, Levey AI, Landwehrmeyer GB, Penney JB, Jr, Young AB, Standaert DG. Localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 mRNA and mGluR7a protein in the rat basal ganglia. J Comp Neurol. 1999;415:266–284. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafon-Cazal M, Viennois G, Kuhn R, Malitschek B, Pin J-P, Shigemoto R, Bockaert J. mGluR7-like receptor and GABAB receptor activation enhance neurotoxic effects of N-methyl-D-aspartate in cultured mouse striatal GABAergic neurones. Neuropharmacology. 1999;38:1631–1640. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(99)00124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei S, McBain CJ. GABAB receptor modulation of excitatory and inhibitory synaptic transmission onto rat CA3 hippocampal interneurons. J Physiol. 2003;546:439–453. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2002.034017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, Raiteri M. Carrier-mediated release of neurotransmitters. Trends Neurosci. 1993;16:415–419. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(93)90010-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Peng X-Q, Gilbert J, Pak AC, Xi Z-X, Gardner EL. Activation of metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 (mGluR7) by AMN082 attenuates the rewarding effects of cocaine by a DA-independent mechanism in rats. The 36th Annual Meeting of the Society for Neuroscience; Atlanta, Georgia. October 2006; 2006. Abstract # 21.7. [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Tai C, de Groat WC, Peng X-M, Mata M, Fink DJ. Release of GABA from sensory neurons transduced with a GAD67-expressing vector occurs by non-vesicular mechanisms. Brain Res. 2006:1073–1074. 297–304. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.12.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manzoni O, Michel J-M, Bockaert J. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the rat nucleus accumbens. Eur J Neurosci. 1997;9:1514–1523. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1997.tb01506.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao L, Lau Y-S, Wang JQ. Activation of group III metabotropic glutamate receptors inhibits basal and amphetamine-stimulated dopamine release in rat dorsal striatum: an in vivo microdialysis study. Eur J Pharmacol. 2000;404:289–297. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(00)00633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marabese I, de Novellis V, Palazzo E, Mariani L, Siniscalco D, Rodella L, Rossi F, Maione S. Differential roles of mGlu8 receptors in the regulation of glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid release at periaqueductal grey level. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49(Suppl 1):157–166. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marabese I, Rossi F, Palazzo E, de Novellis V, Starowicz K, Cristino L, Vita D, Gatta L, Guida F, Di Marzo V, Rossi F, Maione S. Periaqueductal gray metabotropic glutamate receptor subtype 7 and 8 mediate opposite effects on amino acid release, rostral ventromedial medulla cell activities, and thermal nociception. J Neurophysiol. 2007;98:43–53. doi: 10.1152/jn.00356.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek GJ. Metabotropic glutamate 2/3 receptors as drug targets. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:18–22. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin G, Nie Z, Siggins GR. Metabotropic glutamate receptors regulate N-methyl-D-aspartate-mediated synaptic transmission in nucleus accumbens. J Neurophysiol. 1997;78:3028–3038. doi: 10.1152/jn.1997.78.6.3028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsukawa K, Yamamoto R, Ofner S, Nozulak J, Pescott O, Lukic S, Stoehr N, Mombereau C, Kuhn R, McAllister KH, van der Putten H, Cryan JF, Flor PJ. A selective metabotropic glutamate receptor 7 agonist: activation of receptor signaling via an allosteric site modulates stress parameters in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:18712–18717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508063102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palucha A, Klak K, Branski P, van der Putten H, Flor PJ, Pilc A. Activation of the mGlu7 receptor elicits antidepressant-like effects in mice. Psychopharmacology. 2007;194:555–562. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panatier A, Poulain DA, Oliet SHR. Regulation of transmitter release by high-affinity group III mGluRs in the supraoptic nucleus of the rat hypothalamus. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47:333–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelkey KA, Yuan X, Lavezzari G, Roche KW, McBain CJ. mGluR7 undergoes rapid internalization in response to activation by the allosteric agonist AMN082. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng X-Q, Li X, Gilbert JG, Pak AC, Ashby CR, Brodie JD, Dewey SL, Gardner EL, Xi Z-X. Gamma-vinyl GABA inhibits cocaine-triggered reinstatement of drug-seeking behavior in rats by a dopamine-independent mechanism. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2007.10.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porter JT, Nieves D. Presynaptic GABAB receptors modulate thalamic excitation of inhibitory and excitatory neurons in the mouse barrel cortex. J Neurophysiol. 2004;92:2762–2770. doi: 10.1152/jn.00196.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sansig G, Bushell TJ, Clarke VRJ, Rozov A, Burnashev N, Portet C, Gasparini F, Schmutz M, Klebs K, Shigemoto R, Flor PJ, Kuhn R, Knoepfel T, Schroeder M, Hampson DR, Collett VJ, Zhang C, Duvoisin RM, Collingridge GL, van Der Putten H. Increased seizure susceptibility in mice lacking metabotropic glutamate receptor 7. J Neurosci. 2001;21:8734–8745. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-22-08734.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffhauser H, Knoflach F, Pink JR, Bleuel Z, Cartmell J, Goepfert F, Kemp JA, Richards JG, Adam G, Mutel V. Multiple pathways for regulation of the KCl-induced [3H]-GABA release by metabotropic glutamate receptors, in primary rat cortical cultures. Brain Res. 1998;782:91–104. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01271-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Wada E, Nomura S, Ohishi H, Takada M, Flor PJ, Neki A, Abe T, Nakanishi S, Mizuno N. Differential presynaptic localization of metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in the rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 1997;17:7503–7522. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-19-07503.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shigemoto R, Kulik A, Roberts JDB, Ohishi H, Nusser Z, Kaneko T, Somogyi P. Target-cell-specific concentration of a metabotropic glutamate receptor in the presynaptic active zone. Nature. 1996;381:523–525. doi: 10.1038/381523a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somogyi P, Dalezios Y, Luján R, Roberts JDB, Watanabe M, Shigemoto R. High level of mGluR7 in the presynaptic active zones of select populations of GABAergic terminals innervating interneurons in the rat hippocampus. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2503–2520. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02697.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spooren W, Ballard T, Gasparini F, Amalric M, Mutel V, Schreiber R. Insight into the function of Group I and Group II metabotropic glutamate (mGlu) receptors: behavioural characterization and implications for the treatment of CNS disorders. Behav Pharmacol. 2003;14:257–77. doi: 10.1097/01.fbp.0000081783.35927.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun H, Ma CL, Kelly JB, Wu SH. GABAB receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition of glutamatergic transmission in the inferior colliculus. Neurosci Lett. 2006;399:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.01.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Kajikawa Y, Tsujimoto T. G-Protein-coupled modulation of presynaptic calcium currents and transmitter release by a GABAB receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3138–3146. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-09-03138.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas NK, Jane DE, Tse HW, Watkins JC. alpha-Methyl derivatives of serine-O-phosphate as novel, selective competitive metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonists. Neuropharmacology. 1996;35:637–642. doi: 10.1016/0028-3908(96)84635-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wada E, Shigemoto R, Kinoshita A, Ohishi H, Mizuno N. Metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes in axon terminals of projection fibers from the main and accessory olfactory bulbs: a light and electron microscopic immunohistochemical study in the rat. J Comp Neurol. 1998;393:493–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA. Forebrain substrates of reward and motivation. J Comp Neurol. 2005;493:115–121. doi: 10.1002/cne.20689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witkin JM, Marek GJ, Johnson BG, Schoepp DD. Metabotropic glutamate receptors in the control of mood disorders. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2007;6:87–100. doi: 10.2174/187152707780363302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wittmann M, Marino MJ, Bradley SR, Conn PJ. Activation of group III mGluRs inhibits GABAergic and glutamatergic transmission in the substantia nigra pars reticulata. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1960–1968. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.5.1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xi Z-X, Shen H, Baker DA, Kalivas PW. Inhibition of non-vesicular glutamate release by group III metabotropic glutamate receptors in the nucleus accumbens. J Neurochem. 2003;87:1204–1212. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2003.02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]