Abstract

In recent years, it has become increasingly evident that mammalian Toll-like receptors (TLRs) play a critical role in determining the outcome of virus infection. TLRs have evolved to recognize viral nucleic acids, and promote the stimulation of innate and adaptive immune responses. Interestingly, the study of mice harboring deficiencies in various TLR proteins and their adaptors suggests that TLR activation promotes protective anti-viral immunity in some cases, while exacerbating virus-induced disease in others. In this report we describe the interactions of viruses with both the TLR system and the intracellular recognition system and highlight the role of TLRs in shaping the outcome of virus infection in both a positive and negative manner.

Keywords: innate immunity, viral recognition, viral pathogenesis, TLR, pattern recognition receptor, type I interferon

1. Introduction

While viral innate immunity is regulated at multiples levels, evolutionary pressures have selected viral recognition as a key, if not the key, checkpoint in the cellular response to viral infection. It was known as early as the 1950s, through studies performed by Isaacs and Lindenmann, that virus infection leads to the release a soluble factor which “interfered” with the infection and replication in trans1. This factor was subsequently identified as type I interferon (IFN) and the importance of IFN in innate immunity is evidenced by the observation that mice with a genetic deficiency in the IFN receptor (IFNα/βR-/-) are exquisitely susceptible to multiple viral infections2. At that time however, the cellular pathways responsible for the recognition of virus infection and the subsequent stimulation of an IFN response were less clear. Recent years have seen a dramatic increase in our understanding of how viruses are “sensed” by the innate immune system and the functional consequences of such virus-host interactions. The proposal of pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) and the discovery of mammalian Toll-like receptors (TLRs) by Medzhitov and Janeway has opened a new chapter in the course of viral recognition and innate immunity3. Viral recognition by TLRs potently stimulates innate immune responses through the stimulation of IFNα/β-dependent and independent pathways.

The Toll pathway was originally discovered in Drosophila for its role in regulating dorsal-ventral polarity4, 5 and Hoffmann and colleagues subsequently demonstrated that Toll mutants failed to produce anti-fungal peptides and were hypersensitive to fungal infections6. Since then, up to 13 mammalian TLRs have been identified and much effort has recently focused on both identifying the precise structures recognized by each TLR, and the functional effects of those interactions on microbial pathogenesis7, 8. TLRs are members of the PRR family, which recognize conserved microbial moieties termed, pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), as originally proposed by Charles Janeway9, 10. TLR triggering, following virus detection, catalyzes a complex signaling cascade initiated by the toll/interleukin-1 receptor (TIR) domain in the cytoplasmic tail of the TLR, which ultimately leads to expression of variety of genes11-13. TIR domain-containing adaptor molecules, MyD88, which is utilized by all TLRs except for TLR3, as well as TIRAP, TRIF, and TRAM (for TLR4), are recruited to the receptor and activate a complex containing IRAKs and TRAFs which signal through NF-kB14. The molecular details of TLR signaling have been well described in other reviews11, 12, 14-16.

Ultimately, TLR stimulation culminates in the synthesis of antiviral cytokines, such as type I IFNs, IL-1β, and IL-6, which may directly suppress viral replication. These signals efficiently recruit immune cells to sites of virus infection and activate dendritic cells (DCs) - effectively linking innate recognition to the induction of adaptive immunity17-19. Many aspects of how TLR biology impact innate immunity have been described elsewhere. Therefore, here we highlight recent evidence revealing the means by which TLRs affect the outcome of viral infection, and discuss the growing complexity in the control of TLR-dependent immune induction.

2. The Nature of a Viral PAMP

Viral recognition by the innate immune system relies upon a group of germline-encoded receptors to alert the host to the presence of viral pathogens. Such a model has important implications for the molecular structures that are recognized by PRRs. First, the moieties selected for recognition must be absolutely distinct from natural cellular components in order to avoid the deleterious effects of self recognition20. The activation of innate immunity directed against self antigens may directly catalyze autoimmune reactions; therefore, PRRs have evolved to discriminate signatures present in viruses, or virus-infected cells, which are absent from uninfected cells. Simultaneously, the ability to elude recognition by the innate immune system provides a distinct selective advantage on viral fitness. Given the high error rate of viral polymerase enzymes, especially those of viruses containing RNA genomes, PRRs must recognize invariant structures essential to virus survival, and thus not subject to mutagenesis as a viral evasion strategy9, 20, 21. In general, innate PRRs have evolved to deal with this conundrum by targeting distinct features present in viral nucleic acids for recognition9. As these structures are generally sequence-independent, they are presented to the innate immune system by all viruses, even those which have evolved to produce a quasi-species, or swarm of viral genomes as a survival strategy. Ergo, while detection of viral proteins by TLRs clearly impinges upon virus-induced disease (see below), viral nucleic acids (either of the genome or produced during replication) better satisfy the Janeway definition of a viral PAMP.

3. Non-TLR-mediated Viral Recognition

Implicit in the existence of multiple PRRs is the assumption that each receptor recognizes a distinct molecular signature, such that cumulatively, the diversity of moieties recognized provides protection against all the major classes of infectious microbes in the relevant cellular compartments. However, which PRRs are utilized for the recognition of each specific viral pathogen represents an intense area of inquiry. While TLRs clearly play an important role in viral recognition (see below), many viruses induce type I IFN in a TLR-independent manner, suggesting the existence of additional sensing molecules. Indeed, recent work has uncovered new cytoplasmic PRRs which recognize viruses containing both DNA22, 23 and RNA24-26 genomes.

RNA viruses are efficiently recognized by the cytoplasmic RNA helicases, retinoic acid-inducible gene-I (RIG-I)27 and melanoma differentiation-associated gene 5 (MDA5)28. Both of these proteins recognize viral RNA through their helicase domains. Binding to viral RNA catalyzes a conformational rearrangement which exposes a caspase activation and recruitment domain (CARD) to initiate antiviral signaling24-26. Both RIG-I and MDA5 utilize a common adaptor molecule termed MAVS29, IPS-130, Cardif31, or VISA32, which was independently identified by multiple groups and localizes to the mitochondrial membrane29. The third member of the family, lgp2, displays sequence homology to the helicase domains of RIG-I and MDA5, however lacks a CARD, domain and therefore serves as a negative regulator of both sensors33-35. Interestingly, a recent report suggests that lgp2 may play both a positive and negative regulatory role in RIG-I and MDA5-mediated innate immunity36.

Analysis of RIG-I and MDA5 deficient animals has revealed important and distinct roles for these sensing molecules in innate immunity. RIG-I functions as a critical PRR for a number of viruses including Sendai virus (SeV), Vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV), Influenza virus (Flu), Hepatitis C virus (HCV), Japanese encephalitis virus (JEV), as well as small RNAs encoded by the DNA virus, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)37, 38. In contrast, MDA5 serves as a sensor for synthetic dsRNA and picornaviruses37, 39. These molecules cumulatively provide the host with the ability to recognize a large group of viral pathogens in infected cells and mediate a critical aspect of innate antiviral defense. RIG-I/MDA5 are the critical sensors of viral infection in most cell types including fibroblasts and conventional dendritic cells (DCs), while plasmacytoid DCs rely upon the TLR pathway for RNA virus recognition40 (see below).

An intracellular PRR responsible for sensing viruses with DNA genomes has also recently been identified. The existence of a TLR-independent cytoplasmic DNA sensing molecule was suggested from a number of studies utilizing DNA viruses and bacteria41, 42. Recently, Takaoka et al. identified the DAI protein (also known as DLM-1/ZBP1) as a candidate intracellular DNA sensing molecule43. DAI physically interacts with the B form of DNA in the cytosol and recruits an anti-viral signaling complex that results in the activation of NF-kB and the production of type I IFNs. IFN induction following B-DNA treatment was abrogated by a specific interfering RNA directed against DAI, suggesting that DAI is a critical cytoplasmic DNA sensor43. Examination of DAI deficient animals should provide important insights into the role of this protein in antiviral defense in vivo.

4. TLRs as Sensors of Virus infection

As mentioned above, PRRs in general, and the TLRs specifically have evolved to recognize unique signatures overrepresented in viral nucleic acids. The first TLR implicated in viral nucleic acid recognition was TLR344. TLRs 3, 7, 8, and 9 typically reside in the endosome as opposed to at the plasma membrane, where they can gain access to viral nucleic acids. This appears to be a well-suited strategy as most viruses, or viral signatures, localize to the endosome either during entry and uncoating, or during assembly and budding45, 46. Double stranded RNA intermediates are produced during the replication cycle of most viruses, including viruses with DNA genomes47, and these RNA secondary structures are thought to be recognized by TLR3. It is clear that TLR3 responds to the artificial dsRNA mimic, polyiosinic-polycytidylic acid (polyIC), when it is provided extracellularly37, 39. However, evidence supporting TLR3-mediated recognition of authentic viral replication intermediates remains elusive. Indeed, much speculation exists regarding the role of TLR3 in viral infections in vivo48, 49. It has been reported that TLR3 is involved in recognizing virus-produced dsRNA in the context of phagocytized apoptotic cells50. In fact, it has been suggested that TLR3 has evolved specifically to detect the presence of virus-infected dead, or dying cells51. Further studies will be required to clearly elucidate the role of TLR3 in viral recognition and pathogenesis in vivo.

TLR7 was originally shown to be responsible for mediating the antiviral effects induced following delivery of imidazoquinoline compounds52. It is now clear that TLR7 and TLR8 recognize single stranded RNA (ssRNA) and induce innate immune responses to ssRNA-viruses53. Infection of TLR7-/- mice in vivo, or of immune cells, especially plasmacytoid DCs (pDCs) in vitro, with Flu, SeV, and VSV resulted in abrogated IFN and cytokine responses54, 55. TLR7-dependent signaling was also induced following delivery single stranded RNA oligonucleotides derived from human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) RNA56. Furthermore, Diebold et al. demonstrated that uridine and ribose, the defining signatures of RNA, are both necessary and sufficient for TLR7 stimulation57. Furthermore, viral fusion and/or uncoating58 and endosomal acidification54, 59 are required for TLR7-dependent immunity. TLR7 recognition of viral RNA, synthetic polyU RNA, and even non-viral, cellular RNA in the endosome is sufficient to stimulate TLR7-dependent cytokine production55-57. Together these results suggest a key regulatory role for endosomal nucleic acid localization in TLR7-dependent antiviral immune induction; however, the precise structural requirements that govern TLR7-mediated RNA recognition remain elusive. A more detailed analysis of the contribution of endosomal targeting in TLR-mediated immune induction is described below.

TLR9 is also located in the endosome and likewise mediates recognition of viral nucleic acids. In this case, it is the recognition of viral DNA that stimulates TLR9. Bacterial DNA sequences containing hypomethylated CpG motifs were first shown to activate TLR960. It is now clear that TLR9 is the principal means by which HSV-1 and HSV-2 stimulate type I IFNs in pDCs in vivo61, 62. As predicted, this response was dependent upon acidification of the endosome, as treatment of with chloroquine or bafilomycin61 abrogated recognition. Furthermore, Honda et al. demonstrated that the ability of pDCs to retain the TLR9 ligand, CpG DNA, in the endosomal vesicle for long periods of time is critical to recruit a signaling complex containing MyD88 and the transcription factor IRF-763. In particular, CpG localization to the early endosomes (transferrin receptor positive compartment) correlated with the ability of a cell to signal through TLR963. Interestingly, a TLR9 molecule “retargeted” to the plasma membrane was unable to respond to viral nucleic acids, however now responded to self DNA which did not stimulate wild type TLR964. These results suggest that not only is endosomal localization important to trigger TLR-viral nucleic acid interactions, but that endosomal TLRs may limit access to non-viral nucleic acids via an active “sequestering” mechanism64, 65 in the endosome. Such a mechanism may provide protection from the deleterious effects of “inappropriate” nucleic acid recognition51, 64, 65.

5. Endosomal Targeting and Autophagy in TLR-mediated Viral Immunity

As described above, endosomal targeting of TLRs is an important regulatory control mechanism; however the precise role of endosomal localization of TLRs in the generation of anti-viral immunity is not completely understood. Recent studies performed by Lee et al. shed new light in this regard by identifying autophagy as a critical mediator of endosomal TLR-mediated virus recognition66 (reviewed in67, 68). Recognition of dsDNA viruses and ssRNA viruses in pDCs is mediated by endosomal TLR9 and TLR7, respectively40. It has been proposed that viral nucleic acid recognition by TLR7 requires only the presence of viral RNA in the endosomal/lysosomal compartment53, suggesting that RNA replication is not required. However, this interpretation is blurred by the observation that UV-inactivated VSV66, SeV66, and RSV69 failed to induce IFN production in pDCs. This, combined with the fact that VSV and SeV recognition in pDCs is TLR7-dependent66, and that both viruses replicate in the cytoplasm, suggest that cytoplasmic replication intermediates are required for viral recognition by TLR7.

The study by Lee et al. demonstrated that this cytoplasmic sampling by endosomal TLRs occurs via autophagy. Autophagy represents an ancient, conserved pathway responsible for the recycling of long lived proteins and organelles70. Viral recognition by endosomal TLRs was dependent upon autophagy, as pDCs derived from animals lacking a critical autophagy protein (atg-5) failed to induce a type I IFN response following VSV infection66. Indeed recent studies suggest that autophagy is utilized by the immune systems for the generation of both innate and adaptive immune responses to viral and non-viral pathogens71-74. Interestingly, while IFNα responses were abrogated in atg-5-deficient mice in response to a TRL9 ligand, the IL-12 response was unaffected66. This observation suggests that cytoplasmic sampling via autophagy, instead of simply delivering cytoplasmic contents to the endosomal TLR, may instead play a role in regulating the trafficking of TLRs in intracellular compartments, or the recruitment of a TLR signaling complex to the correct intracellular location66-68. These findings further underscore the role of the endosome in TLR biology and predict the existence of a family of adaptor proteins that direct TLR to the appropriate intracellular compartments.

In this regard, the endoplasmic reticulum membrane protein, UNC-93B75-78, has been shown to be required for signaling through intracellular TLRs. This protein was originally identified by Tabeta et al. as a single N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mutation in the Unc93b1 gene, which markedly reduced both endosomal TLR signaling and MHC class I and class II presentation76, 78. Mice harboring this mutated UNC-93B allele failed to respond to endosomal TLR ligands and were dramatically more susceptible to murine CMV infection. UNC-93B was reported to exert its effects independent of endosomal acidification or TLR intracellular localization76. Recently, Brinkmann et al. demonstrated a physical interaction between wild type, but not mutated, UNC-93B and all three endosomal TLRs (TLR3, 7, and 9)75. Moreover, the interaction of UNC-93B and TLRs occurred via the TLR transmembrane domain75, which has previously been demonstrated to harbor the sorting signal required for TLR779 and TLR964, 80 intracellular localization. Genetic evidence further implicates UNC-93B as a critical regulator of endosomal TLR function as Casrouge et al. identified deleterious mutations in the Unc93b1 gene in two patients with severe HSV encephalitis77. The mechanism by which an ER-resident protein UNC-93B orchestrates endosomal TLR trafficking and signaling awaits further investigation.

6. Identification of Authentic Viral PAMPs

Both the TLR and intracellular pathways play a pivotal role in sensing virus infection, and these pathways are differentially utilized for the recognition of distinct viruses in a cell type-dependent manner. However, little evidence exists regarding the precise viral structures that serve as the authentic PAMP in vivo in either system. For example, the induction of IFNα by VSV, SeV, and Flu in pDCs is completely dependent upon TLR7. However, neither the particular viral ligand, which binds to TLR7, nor the stage in the viral life cycle in which such interactions occur, are understood. Presumably TLR7 senses a specific invariant feature present in the genomic RNA or viral replication intermediates of all these viruses. The genomes of RNA viruses do not exist as naked RNA, but instead are efficiently sequestered as a ribonucleoprotein complex. How and where the genomic RNA is accessed by TLR7 remains unclear.

In the case of RIG-I, Hornung et al. showed that the 5’ triphosphate structure of single stranded RNA is necessary and sufficient to serve as the viral PAMP81. This observation is likewise supported by the studies performed by Pichlmair et al. who also concluded that uncapped, 5’ triphosphate structures serve as the ligand for RIG-I82. Moreover, a recent report from Gale and colleagues demonstrated that RIG-I is activated by both the 5’ and 3’ untranslated regions of HCV, suggesting an authentic PAMP is present in the conserved secondary structure of the non-translated regions of the genome83. In addition, Silverman and colleagues have recently unveiled a novel regulatory element in the production of viral PAMPs84. The authors demonstrated that cellular RNAs cleaved by the antiviral endoribonuclease, RNaseL, which contain 3’ monophosphoryl group, efficiently serve as a ligand for both RIG-I and MDA584. These results suggest that following initiation of an antiviral cascade, even RNAs of cellular origin can serve as a viral PAMP to amplify the RNA helicase-induced pathways, and highlight the complexities involved in the identification of viral PAMPs.

7. TLRs Shape the Outcome of Viral Infection

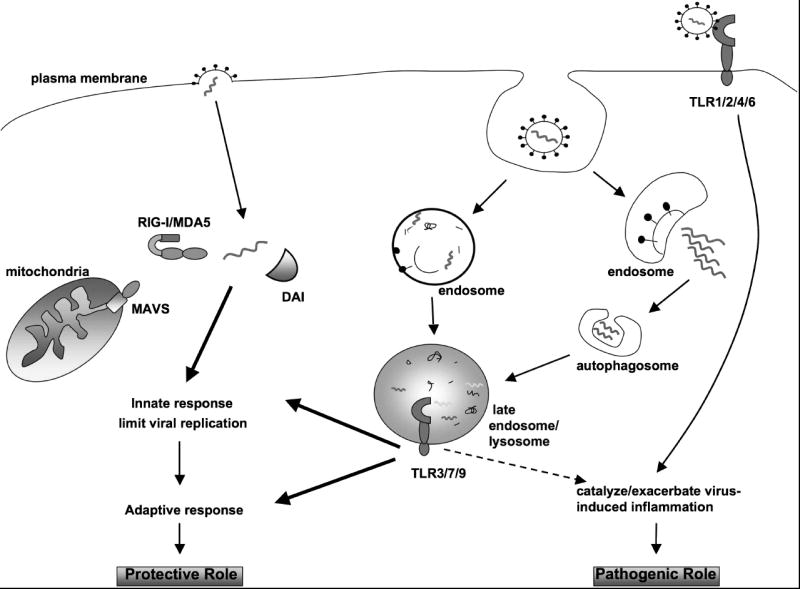

Up to this point we have limited our analysis to what is known regarding TLR-mediated recognition of viral signatures without consideration to how such recognition impinges upon viral pathogenesis. In general terms, virus-induced disease can be characterized as direct, owing to cellular destruction as a result of viral replication; or indirect, in which the cellular response to the virus itself is the etiological cause of clinical disease. Consequent to TLR ligation, a plethora of cellular pathways are simultaneously launched, which may affect virus-induced disease in an unexpected manner. Studies in TLR knockout (KO) animals have demonstrated that TLRs either: 1) play no role, or a limited role; 2) play a dominant role in protection; or 3) exacerbate clinical manifestations, depending upon the specific viral system (Fig. 1). These studies suggest that TLRs affect virus outcome by a variety of mechanisms85 including: directly modulating the magnitude and/or duration of viral replication, catalyzing or dampening the virus-triggered inflammatory response, and/or the activation of virus-specific adaptive immunity. In this section we highlight reports that demonstrate instances in which virus-induced TLR stimulation positively or negatively regulate clinical disease in mice.

Figure 1. Positive and negative consequences of TLR-virus interaction.

Viral sensing, following either direct fusion with the plasma membrane, or receptor-mediated endocytosis, initiates innate immunity and regulates virus-induced disease. Depending upon the viral genome content and entry mechanism, viral nucleic acids, or replicative intermediates, are recognized by one of the cellular sensing molecules such as DAI, RIG-I/MDA5, or one of the endosomal TLRs (3, 7, 9), and an innate anti-viral program is activated. Recognition of RNA viruses (RIG-I/MDA5) and DNA viruses (DAI) by the intracellular sensors stimulates innate immunity that limits replication and promotes protection. In the case of the TLR pathway, viral sensing by endosomal TLRs may lead to a protective innate and adaptive immune response. For certain ssRNA viruses, the delivery of viral PAMP to the late endosome/lysosome compartment is mediated by autophagy. Conversely, these interactions may exacerbate virus-induced disease, leading to a poor outcome for the host. Likewise, plasma membrane TLRs may also promote virus-induced inflammation. Together, these examples highlight how viral-TLR interactions affect virus-induced disease both in a positive and negative fashion.

The ability of TLRs to confer innate protection against virus infection and disease has been well documented. Hardarson et al. recently reported a direct role for TLR3 in protection from virus-induced disease86. Encephalomycoarditis virus (EMCV)-induced mortality was significantly higher in TLR3 KOs. This was directly proportional to the increase in viral titers both in the heart and the liver in TLR3KO mice, suggesting that the ability of TLR3 to limit viral replication is responsible for alleviating the downstream disease manifestations in the EMCV model86. A protective role for TLR3 in viral pathogenesis is also suggested by the observation that abrogating mutations in the TLR3 protein are associated with severe influenza87 and HSV-188 disease in human patients. Further, TLR9 plays a protective role in response to murine CMV, evidenced by the observation that animals deficient in either TLR9 or MyD88 are hypersensitive to murine CMV-induced mortality89. Additionally, in the murine CMV model, both TLR290 and TLR991 appear to regulate the activation of a protective NK cell response. Additionally, Lund et al. demonstrated that TLR9 confers protection against mucosal HSV-2 infection in a pDC-dependent manner92. However, TLR9 deficiency did not affect HSV-1 titers in a cutaneous infection model62, suggesting the potential for route-specific, TLR-mediated protective effects.

In other viral models, not only do TLRs fail to limit viral replication, but dramatically promote aberrant inflammatory responses, leading to increased mortality48, 93-95. RSV-infected TLR3 KO mice display increased pulmonary inflammation and eosinophil recruitment to the lung even though viral titers are unaffected93. Likewise, TLR3 KO mice are largely resistant to Punta Toro virus (PTV) infection, whereas approximately 90% of wild type mice succumb to a lethal liver inflammatory disease. Again, viral titers were largely unaffected in TLR3 KOs. Further support for TLR3-mediated inflammation stems from studies of West Nile virus (WNV) and influenza (Flu) virus infections of TLR3 KO animals96, 97. In the case of WNV, TLR3 KO animals exhibited decreased susceptibility to peripheral infection, decreased systemic IL-6 and TNFα responses, and increased permeability of the blood brain barrier (BBB)96. The authors went on to show that increased BBB permeability was dependent upon TLR3-induced TNFα production, suggesting that, during natural infections, TLR3-dependent systemic inflammation promotes virus entry into the brain by modulating the integrity of the BBB98. Moreover, while viral titers of Flu virus are significantly higher in the lungs of TLR3 KO mice as compared to wild type mice, the production of proinflammatory cytokines and subsequent Flu-induced mortality is dramatically reduced in the absence of TLR397. Taken together, these results suggest the dual role of TLR3 in viral pathogenesis, leading to diminished disease by directly inhibiting viral replication in one model, and promoting virus-induced inflammation in others.

Analysis of the TLR system in the pathogenesis of HSV infection further supports the notion that TLR interactions catalyze virus-induced inflammation. Kurt-Jones and colleagues demonstrated that both adult, and especially neonatal, TLR2 KO mice produce a diminished proinflammatory cytokine response and are significantly more resistant to mortality caused by HSV-199, 100. Interestingly, this effect was not due to a viral replication defect, as brain titers in both wild type and TLR2-/- animals were essentially equivalent100. Of note, an additional report demonstrated that TLR2 induces apoptosis of HSV-infected microgial cells, potentially implicating microglial cells in the regulation of the inflammatory response following HSV infection101. The regulation of HSV-induced disease by TLR2 is not limited to models of HSV encephalitis, as TLR2 KO mice were also considerably resistant to ocular lesions associated with stromal keratitis caused by HSV-1102. Interestingly, a recent report identified an association between naturally occurring polymorphisms in TLR2 and the severity and recurrence of HSV-2 infections in humans103, suggesting a role for TLR2 in the regulation of HSV-induced disease in the human population.

While viral nucleic acids serve as the true viral PAMP, interactions with TLRs and viral proteins can also provide a protective role in viral pathogenesis. For example, Kurt-Jones et al. demonstrated that RSV peak titers and the longevity of persistence were significantly increased in mice harboring a natural deletion in TLR4 (C57BL10/ScCr mice) compared to wild type mice104 . Speculation exists as to the physiological role of TLR4 in RSV pathogenesis, as CF7BL10/ScCr mice are known also to harbor a defect in the gene encoding IL-12Rβ2105, and an additional study suggested that the cytokine secretion defect in CF7BL10/ScCr mice is not due to the TLR mutation, but instead explained by theIL-12 deficiency106. However, Tal et al. demonstrated that abrogating mutations in TLR4 are significantly overrepresented in children who experience severe RSV disease compared to children with mild RSV symptoms, suggesting a potential role for TLR4 in mediating the clinical outcome of RSV disease in its natural population106. These results exemplify the importance of evaluating TLRs in natural models of virus infection.

Viral TLR systems provide a unique opportunity to study host pathogen interactions. In addition to playing both protective and pathogenic roles in viral pathogenesis, two studies suggested that viruses rely upon TLR signaling as a survival mechanism107, 108. As mentioned above, the HA protein of Measles virus induces cytokine secretion in a TLR2-dependent manner107. Interestingly, this interaction also results in upregulated expression of the MV receptor, CD150, suggesting that HA-TLR2 interactions in fact benefit the virus at the expense of the host107, unless increased infection can be viewed as an effective antiviral strategy. Likewise, the interaction of the MMTV env protein with TLR4 provides a selective advantage to the virus by promoting infection of target cells, transcription of the viral genome, and release of the immunoregulatory cytokine, IL-10108. It has been suggested that IL-10 may serve as a master regulator of chronic vs. acute viral infections109, and thus it warrants analyzing whether TLR-dependent IL-10 production plays an important role in the pathogenesis of other chronic viral systems, such as HIV and HCV.

Taken together, the examples described here provide strong evidence that TLRs dramatically affect the outcome of viral infection. This complex regulation may protect the host from virus-induced disease either by limiting viral replication, or by tempering virus-induced immune pathology (Figure 1). Conversely, TLRs may predispose the host to the deleterious manifestations associated with virus infection. Future studies will be required to define the precise mechanisms by which TLRs modulate viral pathogenesis in each specific system and what factors delineate the balance between protective and pathogenic immunity.

8. Perspectives and Concluding Remarks

Defining the pathways that regulate viral pathogenesis is an important endeavor, with serious ramifications. Viral-induced disease represents a significant threat to human health and the world economy. Our understanding of the role of TLRs in viral pathogenesis has expanded significantly over the last few years and it is clear that TLRs provide protective anti-viral immunity in some cases, while clearly exacerbating virus-induced disease in others. To date, a systematic understanding of the factors that regulate this balance is lacking. This, in turn, provides us with an opportunity to establish if such a hierarchy does in fact exist, and if so, the potential to lessen the burden of virus-induced disease.

Our knowledge of the TLR system in viral disease stems mostly from studies of TLR KO mice. However, additional support comes from the observation that viruses have evolved molecular mechanisms to interfere with the TLR pathway, which would not have occurred if such strategies did not provide a selective advantage. For example, VV encodes two proteins, A46110 and A52111, which antagonize the TLR system independently. Deletion of either gene from the viral genome resulted in an attenuated phenotype, suggesting that the virus has evolved TLR inhibition as a survival strategy110, 111. Likewise, inhibition of TLR-dependent signaling by several HCV proteins has also been documented112, 113, further validating the importance of TLR evasion. As more TLR regulatory pathways are discovered, no doubt this list will likewise expand, and may provide insights into virus maintenance and evolution.

Challenge 1

In this review, the role of a single TLR in mediating viral outcome was considered for simplicity; however, this is not the full picture. In the real world, such interactions are complex, often encompassing multiple TLRs that interact with distinct signatures in a single virus. This is particularly true in the case of the Herpes viruses where HSV interacts with TLRs 2, 3, and 988, 114, 115, and CMV interacts with TLRs 2, 3, and 9116. Defining the exact contribution of each TLR alone and in combination with the other activated TLRs is crucial to assess the extent to which TLRs modulate viral pathogenesis. This analysis is confounded by that fact that specific TLR signaling occurs in distinct immune compartments117, and is dependent upon viral genetics107, 115, inoculation route118, and virus dose118. The issue of virus dose is interesting as most in vivo infection models rely upon delivery of relatively large doses of virus, which may mask subtle effects caused by virus TLR interactions under more physiological conditions, as suggested by Gowen et al94. Likewise, it will be important to clarify whether the phenotype observed by Bieback et al., that TLR interaction is limited to wild type MV, and not attenuated strains, also holds true for other viral systems107. Accordingly, analysis of clinical viral isolates with both mouse and natural human TLR proteins may identify novel roles for the TLR family in viral pathogenesis. It is possible that a reevaluation of these issues may uncover a previously unappreciated role of TLRs in shaping the outcome of viral disease.

Challenge 2

In analyzing the response to virus infection in genetically diverse hosts, such as in the human population, heterogeneity is the rule. Undoubtedly, this response is governed by the actions of numerous gene products to facilitate anti-viral immunity. As new TLR regulatory pathways continue to be discovered, it will be interesting to determine if polymorphisms in either TLRs, or TLR regulatory proteins correlate positively or negatively with disease severity in humans. In fact, polymorphisms in TLR387, TLR4106, and the ER protein, UNC-93B77 have all been shown to correlate with poor outcome following viral infection. Based upon the idea that TLRs negatively impact viral pathogenesis, it is also possible that a correlation exists between TLR polymorphisms and decreased susceptibility to viral infection. However, whether such mutations would be selected for if they abrogate TLR activity directed against other pathogens is unclear. It is possible that a molecular genetic analysis of TLR alleles in natural populations may provided a means to predict how an individual may respond to a TLR-containing virus or vaccine, and provide an opportunity for alternative intervention85.

Challenge 3

Finally, it will be important to clarify the cellular mechanisms by which TLRs regulate the balance between protective and pathogenic immunity. In the case of WNV, TLR signaling promotes viral entry into the CNS by modulating the integrity of the blood brain barrier96, however whether BBB effects are responsible for exacerbated disease in other models, such as for TLR2 and HSV infections100, remains to be determined. Likewise, it has been suggested that TLR signaling in pDCs can function to downregulate aberrant virus-induced inflammation, at least in part, in a type I IFN-independent manner119. Identification of the regulatory programs initiated by TLR signaling will provide important new insights into the role of TLRs in viral pathogenesis.

In summary, the work outlined here provides clear evidence that TLRs play a pivotal role in viral pathogenesis on several levels. Furthermore, despite the identification of how TLR biology impacts virus-induced disease, many unanswered questions remain. Investigations over the next few years should begin to unravel the specific mechanics of TLR-mediated immune regulation and may provide novel antiviral intervention strategies.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge all of our colleagues for their contributions and apologize to those whose work we could not cite. Also, we thank Takeshi Ichinohe for assistance in figure preparation and the members of the laboratory for helpful discussions. This work was supported by Public Health Service grants from the NIH/NIAID; R01 AI 054359, R01 AI 062428, R01 AI 064705 (to A.I.), and a Postdoctoral Training grant T32 AI 07019 (to J.M.T.). Additionally, A.I. is an Investigator of the Pathogenesis of Infectious Diseases through the Burroughs Wellcome Fund.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Isaacs A, Lindenmann J. Virus interference. I. The interferon. Proc R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 1957;147:258–67. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Muller U, et al. Functional role of type I and type II interferons in antiviral defense. Science. 1994;264:1918–21. doi: 10.1126/science.8009221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson KV, Bokla L, Nusslein-Volhard C. Establishment of dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo: the induction of polarity by the Toll gene product. Cell. 1985;42:791–8. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90275-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson KV, Jurgens G, Nusslein-Volhard C. Establishment of dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo: genetic studies on the role of the Toll gene product. Cell. 1985;42:779–89. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–83. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uematsu S, Akira S. Toll-like receptors and innate immunity. Journal of Molecular Medicine. 2006;84:712–725. doi: 10.1007/s00109-006-0084-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Akira S, Uematsu S, Takeuchi O. Pathogen Recognition and Innate Immunity. Cell. 2006;124:783–801. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Medzhitov R, Janeway CA. Innate Immunity: The Virtues of a Nonclonal System of Recognition. Cell. 1997;91:295–298. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80412-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janeway CAJ. Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt 1):1–13. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1989.054.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Seminars in Immunology. 2007;19:24–32. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2006.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akira S. TLR signaling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2006;311:1–16. doi: 10.1007/3-540-32636-7_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kawai T, Akira S. TLR signaling. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:816–25. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akira S, Takeda K. Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4:499–511. doi: 10.1038/nri1391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Neill LAJ, Bowie AG. The family of five: TIR-domain-containing adaptors in Toll-like receptor signalling. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:353–364. doi: 10.1038/nri2079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marco C. TLR pathways and IFN-regulatory factors: To each its own. European Journal of Immunology. 2007;37:306–309. doi: 10.1002/eji.200637009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iwasaki A, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptor control of the adaptive immune responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:987–95. doi: 10.1038/ni1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors and acquired immunity. Seminars in Immunology. 2004;16:23–26. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2003.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pasare C, Medzhitov R. Toll-like receptors: linking innate and adaptive immunity. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2005;560:11–8. doi: 10.1007/0-387-24180-9_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Janeway CA., Jr The immune system evolved to discriminate infectious nonself from noninfectious self. Immunol Today. 1992;13:11–6. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90198-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Janeway CA., Jr Approaching the asymptote? Evolution and revolution in immunology. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1989;54(Pt):1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. Cytoplasmic double-stranded DNA sensor. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:907–908. doi: 10.1038/ni0907-907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chi H, Flavell RA. Immunology: Sensing the enemy within. Nature. 2007;448:423–424. doi: 10.1038/448423a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saito T, Gale JM. Principles of intracellular viral recognition. Current Opinion in Immunology. 2007;19:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoneyama M, Fujita T. RIG-I family RNA helicases: Cytoplasmic sensor for antiviral innate immunity. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews. 2007;18:545–551. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2007.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fujita T, Onoguchi K, Onomoto K, Hirai R, Yoneyama M. Triggering antiviral response by RIG-I-related RNA helicases. Biochimie. 2007;89:754–760. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yoneyama M, et al. The RNA helicase RIG-I has an essential function in double-stranded RNA-induced innate antiviral responses. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:730–737. doi: 10.1038/ni1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Andrejeva J, et al. The V proteins of paramyxoviruses bind the IFN-inducible RNA helicase, mda-5, and inhibit its activation of the IFN-{beta} promoter. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:17264–17269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0407639101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Seth RB, Sun L, Ea C-K, Chen ZJ. Identification and Characterization of MAVS, a Mitochondrial Antiviral Signaling Protein that Activates NF-[kappa]B and IRF3. Cell. 2005;122:669–682. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kawai T, et al. IPS-1, an adaptor triggering RIG-I- and Mda5-mediated type I interferon induction. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:981–988. doi: 10.1038/ni1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Meylan E, et al. Cardif is an adaptor protein in the RIG-I antiviral pathway and is targeted by hepatitis C virus. Nature. 2005;437:1167–1172. doi: 10.1038/nature04193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xu L-G, et al. VISA Is an Adapter Protein Required for Virus-Triggered IFN-[beta] Signaling. Molecular Cell. 2005;19:727–740. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yoneyama M, et al. Shared and Unique Functions of the DExD/H-Box Helicases RIG-I, MDA5, and LGP2 in Antiviral Innate Immunity. J Immunol. 2005;175:2851–2858. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.5.2851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Komuro A, Horvath CM. RNA- and Virus-Independent Inhibition of Antiviral Signaling by RNA Helicase LGP2. J Virol. 2006;80:12332–12342. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01325-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rothenfusser S, et al. The RNA Helicase Lgp2 Inhibits TLR-Independent Sensing of Viral Replication by Retinoic Acid-Inducible Gene-I. J Immunol. 2005;175:5260–5268. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.8.5260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venkataraman T, et al. Loss of DExD/H Box RNA Helicase LGP2 Manifests Disparate Antiviral Responses. J Immunol. 2007;178:6444–6455. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.10.6444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kato H, et al. Differential roles of MDA5 and RIG-I helicases in the recognition of RNA viruses. Nature. 2006;441:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature04734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Samanta M, Iwakiri D, Kanda T, Imaizumi T, Takada K. EB virus-encoded RNAs are recognized by RIG-I and activate signaling to induce type I IFN. Embo J. 2006;25:4207–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gitlin L, et al. Essential role of mda-5 in type I IFN responses to polyriboinosinic:polyribocytidylic acid and encephalomyocarditis picornavirus. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:8459–8464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0603082103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kato H, et al. Cell Type-Specific Involvement of RIG-I in Antiviral Response. Immunity. 2005;23:19–28. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stetson DB, Medzhitov R. Recognition of Cytosolic DNA Activates an IRF3-Dependent Innate Immune Response. Immunity. 2006;24:93–103. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ishii KJ, et al. A Toll-like receptor-independent antiviral response induced by double-stranded B-form DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:40–48. doi: 10.1038/ni1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Takaoka A, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007;448:501–505. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Alexopoulou L, Holt AC, Medzhitov R, Flavell RA. Recognition of double-stranded RNA and activation of NF-[kappa]B by Toll-like receptor 3. Nature. 2001;413:732–738. doi: 10.1038/35099560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brandenburg B, Zhuang X. Virus trafficking - learning from single-virus tracking. Nat Rev Micro. 2007;5:197–208. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marsh M, Pelchen-Matthews A. Endocytosis in Viral Replication. Traffic. 2000;1:525–532. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2000.010701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Weber F, Wagner V, Rasmussen SB, Hartmann R, Paludan SR. Double-Stranded RNA Is Produced by Positive-Strand RNA Viruses and DNA Viruses but Not in Detectable Amounts by Negative-Strand RNA Viruses. J Virol. 2006;80:5059–5064. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.10.5059-5064.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schroder M, Bowie AG. TLR3 in antiviral immunity: key player or bystander? Trends in Immunology. 2005;26:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2005.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Edelmann KH, et al. Does Toll-like receptor 3 play a biological role in virus infections? Virology. 2004;322:231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.01.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schulz O, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 promotes cross-priming to virus-infected cells. Nature. 2005;433:887–892. doi: 10.1038/nature03326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Barton GM. Viral recognition by Toll-like receptors. Seminars in Immunology. 2007;19:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2007.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Hemmi H, et al. Small anti-viral compounds activate immune cells via the TLR7 MyD88-dependent signaling pathway. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:196–200. doi: 10.1038/ni758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Crozat K, Beutler B. TLR7: A new sensor of viral infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:6835–6836. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401347101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lund JM, et al. Recognition of single-stranded RNA viruses by Toll-like receptor 7. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:5598–5603. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400937101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Diebold SS, Kaisho T, Hemmi H, Akira S, Reis e Sousa C. Innate Antiviral Responses by Means of TLR7-Mediated Recognition of Single-Stranded RNA. Science. 2004;303:1529–1531. doi: 10.1126/science.1093616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heil F, et al. Species-Specific Recognition of Single-Stranded RNA via Toll-like Receptor 7 and 8. Science. 2004;303:1526–1529. doi: 10.1126/science.1093620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Diebold Sandra S, M C, A S, P C, M Y, Reis e S C. Nucleic acid agonists for Toll-like receptor 7 are defined by the presence of uridine ribonucleotides. European Journal of Immunology. 2006;36:3256–3267. doi: 10.1002/eji.200636617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang JP, et al. Flavivirus Activation of Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Delineates Key Elements of TLR7 Signaling beyond Endosomal Recognition. J Immunol. 2006;177:7114–7121. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.10.7114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Lee J, et al. Molecular basis for the immunostimulatory activity of guanine nucleoside analogs: Activation of Toll-like receptor 7. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2003;100:6646–6651. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0631696100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hemmi H, et al. A Toll-like receptor recognizes bacterial DNA. Nature. 2000;408:740–745. doi: 10.1038/35047123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lund J, Sato A, Akira S, Medzhitov R, Iwasaki A. Toll-like Receptor 9-mediated Recognition of Herpes Simplex Virus-2 by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. J Exp Med. 2003;198:513–520. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Krug A, et al. Herpes simplex virus type 1 activates murine natural interferon-producing cells through toll-like receptor 9. Blood. 2004;103:1433–1437. doi: 10.1182/blood-2003-08-2674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Honda K, et al. Spatiotemporal regulation of MyD88-IRF-7 signalling for robust type-I interferon induction. Nature. 2005;434:1035–1040. doi: 10.1038/nature03547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Barton GM, Kagan JC, Medzhitov R. Intracellular localization of Toll-like receptor 9 prevents recognition of self DNA but facilitates access to viral DNA. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:49–56. doi: 10.1038/ni1280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pichlmair A, Reis e Sousa C. Innate Recognition of Viruses. Immunity. 2007;27:370–383. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lee HK, Lund JM, Ramanathan B, Mizushima N, Iwasaki A. Autophagy-Dependent Viral Recognition by Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells. Science. 2007;315:1398–1401. doi: 10.1126/science.1136880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reis e Sousa C. IMMUNOLOGY: Eating In to Avoid Infection. Science. 2007;315:1376–1377. doi: 10.1126/science.1140002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Iwasaki A. Role of autophagy in innate viral recognition. Autophagy. 2007;3:354–6. doi: 10.4161/auto.4114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hornung V, et al. Replication-Dependent Potent IFN-{alpha} Induction in Human Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells by a Single-Stranded RNA Virus. J Immunol. 2004;173:5935–5943. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.10.5935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yorimitsu T, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy: molecular machinery for self-eating. Cell Death Differ. 12:1542–1552. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schmid D, Munz C. Innate and Adaptive Immunity through Autophagy. Immunity. 2007;27:11–21. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Xu Y, et al. Toll-like Receptor 4 Is a Sensor for Autophagy Associated with Innate Immunity. Immunity. 2007;27:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Levine B, Deretic V. Unveiling the roles of autophagy in innate and adaptive immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2007;7:767–77. doi: 10.1038/nri2161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Schmid D, Munz C. Immune surveillance of intracellular pathogens via autophagy. Cell Death Differ. 12:1519–1527. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Brinkmann MM, et al. The interaction between the ER membrane protein UNC93B and TLR3, 7, and 9 is crucial for TLR signaling. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:265–275. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200612056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tabeta K, et al. The Unc93b1 mutation 3d disrupts exogenous antigen presentation and signaling via Toll-like receptors 3, 7 and 9. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:156–164. doi: 10.1038/ni1297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Casrouge A, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis in Human UNC-93B Deficiency. Science. 2006;314:308–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1128346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Carter RW, Tough DF. ‘3d’ effects on global immunity. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:127–128. doi: 10.1038/ni0206-127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Nishiya T, Kajita E, Miwa S, DeFranco AL. TLR3 and TLR7 Are Targeted to the Same Intracellular Compartments by Distinct Regulatory Elements. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:37107–37117. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504951200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kajita E, Nishiya T, Miwa S. The transmembrane domain directs TLR9 to intracellular compartments that contain TLR3. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 2006;343:578–584. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hornung V, et al. 5’-Triphosphate RNA Is the Ligand for RIG-I. Science. 2006;314:994–997. doi: 10.1126/science.1132505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pichlmair A, et al. RIG-I-Mediated Antiviral Responses to Single-Stranded RNA Bearing 5’-Phosphates. Science. 2006;314:997–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1132998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Saito T, et al. Regulation of innate antiviral defenses through a shared repressor domain in RIG-I and LGP2. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2007;104:582–587. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606699104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Malathi K, Dong B, Gale M, Silverman RH. Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature. 2007;448:816–819. doi: 10.1038/nature06042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Finberg RW, Kurt-Jones EA. Tolls: You Pay Them on the Way In and on the Way Out! J Infect Dis. 2007;196:497–498. doi: 10.1086/519694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hardarson HS, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 is an essential component of the innate stress response in virus-induced cardiac injury. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2007;292:H251–258. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00398.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hidaka F, et al. A missense mutation of the Toll-like receptor 3 gene in a patient with influenza-associated encephalopathy. Clinical Immunology. 2006;119:188–194. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Zhang S-Y, et al. TLR3 Deficiency in Patients with Herpes Simplex Encephalitis. Science. 2007;317:1522–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.1139522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Delale T, et al. MyD88-Dependent and -Independent Murine Cytomegalovirus Sensing for IFN-{alpha} Release and Initiation of Immune Responses In Vivo. J Immunol. 2005;175:6723–6732. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.10.6723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Szomolanyi-Tsuda E, Liang X, Welsh RM, Kurt-Jones EA, Finberg RW. Role for TLR2 in NK Cell-Mediated Control of Murine Cytomegalovirus In Vivo. J Virol. 2006;80:4286–4291. doi: 10.1128/JVI.80.9.4286-4291.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Krug A, et al. TLR9-Dependent Recognition of MCMV by IPC and DC Generates Coordinated Cytokine Responses that Activate Antiviral NK Cell Function. Immunity. 2004;21:107–119. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Lund JM, Linehan MM, Iijima N, Iwasaki A. Cutting Edge: Plasmacytoid Dendritic Cells Provide Innate Immune Protection against Mucosal Viral Infection In Situ. J Immunol. 2006;177:7510–7514. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.11.7510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rudd BD, et al. Deletion of TLR3 Alters the Pulmonary Immune Environment and Mucus Production during Respiratory Syncytial Virus Infection. J Immunol. 2006;176:1937–1942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.3.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Gowen BB, et al. TLR3 Deletion Limits Mortality and Disease Severity due to Phlebovirus Infection. J Immunol. 2006;177:6301–6307. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.9.6301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Bowie AG. Translational Mini-Review Series on Toll-like Receptors:Recent advances in understanding the role of Toll-like receptors in anti-viral immunity. Clinical & Experimental Immunology. 2007;147:217–226. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2006.03301.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wang T, et al. Toll-like receptor 3 mediates West Nile virus entry into the brain causing lethal encephalitis. Nat Med. 2004;10:1366–1373. doi: 10.1038/nm1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Le Goffic R, et al. Detrimental contribution of the Toll-like receptor (TLR)3 to influenza A virus-induced acute pneumonia. PLoS Pathog. 2006;2:e53. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Diamond MS, Klein RS. West Nile virus: crossing the blood-brain barrier. Nat Med. 2004;10:1294–1295. doi: 10.1038/nm1204-1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Kurt-Jones EA, et al. The role of toll-like receptors in herpes simplex infection in neonates. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:746–8. doi: 10.1086/427339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Kurt-Jones EA, et al. Herpes simplex virus 1 interaction with Toll-like receptor 2 contributes to lethal encephalitis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:1315–1320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308057100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Aravalli RN, Hu S, Rowen TN, Palmquist JM, Lokensgard JR. Cutting Edge: TLR2-Mediated Proinflammatory Cytokine and Chemokine Production by Microglial Cells in Response to Herpes Simplex Virus. J Immunol. 2005;175:4189–4193. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.7.4189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Sarangi PP, Kim B, Kurt-Jones E, Rouse BT. Innate Recognition Network Driving Herpes Simplex Virus-Induced Corneal Immunopathology: Role of the Toll Pathway in Early Inflammatory Events in Stromal Keratitis. J Virol. 2007;81:11128–11138. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01008-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Bochud P-Y, Magaret AS, Koelle DM, Aderem A, Wald A. Polymorphisms in TLR2 Are Associated with Increased Viral Shedding and Lesional Rate in Patients with Genital Herpes Simplex Virus Type 2 Infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;196:505–509. doi: 10.1086/519693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Kurt-Jones EA, et al. Pattern recognition receptors TLR4 and CD14 mediate response to respiratory syncytial virus. Nat Immunol. 2000;1:398–401. doi: 10.1038/80833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Poltorak A, et al. A point mutation in the IL-12R beta 2 gene underlies the IL-12 unresponsiveness of Lps-defective C57BL/10ScCr mice. J Immunol. 2001;167:2106–11. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.4.2106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Ehl Stephan, B R, O T, V S, S-M J, P A, F M. The role of Toll-like receptor 4 versus interleukin-12 in immunity to respiratory syncytial virus. European Journal of Immunology. 2004;34:1146–1153. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bieback K, et al. Hemagglutinin Protein of Wild-Type Measles Virus Activates Toll-Like Receptor 2 Signaling. J Virol. 2002;76:8729–8736. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.17.8729-8736.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Jude BA, et al. Subversion of the innate immune system by a retrovirus. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:573–578. doi: 10.1038/ni926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Blackburn SD, Wherry EJ. IL-10, T cell exhaustion and viral persistence. Trends in Microbiology. 2007;15:143–146. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Stack J, et al. Vaccinia virus protein A46R targets multiple Toll-like-interleukin-1 receptor adaptors and contributes to virulence. J Exp Med. 2005;201:1007–1018. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Harte MT, et al. The Poxvirus Protein A52R Targets Toll-like Receptor Signaling Complexes to Suppress Host Defense. J Exp Med. 2003;197:343–351. doi: 10.1084/jem.20021652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Abe T, et al. Hepatitis C Virus Nonstructural Protein 5A Modulates the Toll-Like Receptor-MyD88-Dependent Signaling Pathway in Macrophage Cell Lines. J Virol. 2007;81:8953–8966. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00649-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Li K, et al. Immune evasion by hepatitis C virus NS3/4A protease-mediated cleavage of the Toll-like receptor 3 adaptor protein TRIF. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2005;102:2992–2997. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0408824102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Finberg RW, Knipe DM, Kurt-Jones EA. Herpes Simplex Virus and Toll-Like Receptors. Viral Immunology. 2005;18:457–465. doi: 10.1089/vim.2005.18.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sato A, Linehan MM, Iwasaki A. Dual recognition of herpes simplex viruses by TLR2 and TLR9 in dendritic cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2006;103:17343–17348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0605102103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Tabeta K, et al. Toll-like receptors 9 and 3 as essential components of innate immune defense against mouse cytomegalovirus infection. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:3516–3521. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400525101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Sato A, Iwasaki A. From The Cover: Induction of antiviral immunity requires Toll-like receptor signaling in both stromal and dendritic cell compartments. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2004;101:16274–16279. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406268101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou Shenghua, K-J Evelyn A, M L, C A, C M, G Douglas T, F Robert W. MyD88 is critical for the development of innate and adaptive immunity during acute lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus infection. European Journal of Immunology. 2005;35:822–830. doi: 10.1002/eji.200425730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Smit JJ, Rudd BD, Lukacs NW. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells inhibit pulmonary immunopathology and promote clearance of respiratory syncytial virus. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1153–1159. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Landmark Papers

- 1.Medzhitov R, Preston-Hurlburt P, Janeway CA. A human homologue of the Drosophila Toll protein signals activation of adaptive immunity. Nature. 1997;388:394–397. doi: 10.1038/41131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Malathi K, Dong B, Gale M, Silverman RH. Small self-RNA generated by RNase L amplifies antiviral innate immunity. Nature. 2007;448:816–819. doi: 10.1038/nature06042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jude BA, et al. Subversion of the innate immune system by a retrovirus. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:573–578. doi: 10.1038/ni926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang S-Y, et al. TLR3 Deficiency in Patients with Herpes Simplex Encephalitis. Science. 2007;317:1522–1527. doi: 10.1126/science.1139522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casrouge A, et al. Herpes Simplex Virus Encephalitis in Human UNC-93B Deficiency. Science. 2006;314:308–312. doi: 10.1126/science.1128346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]