Abstract

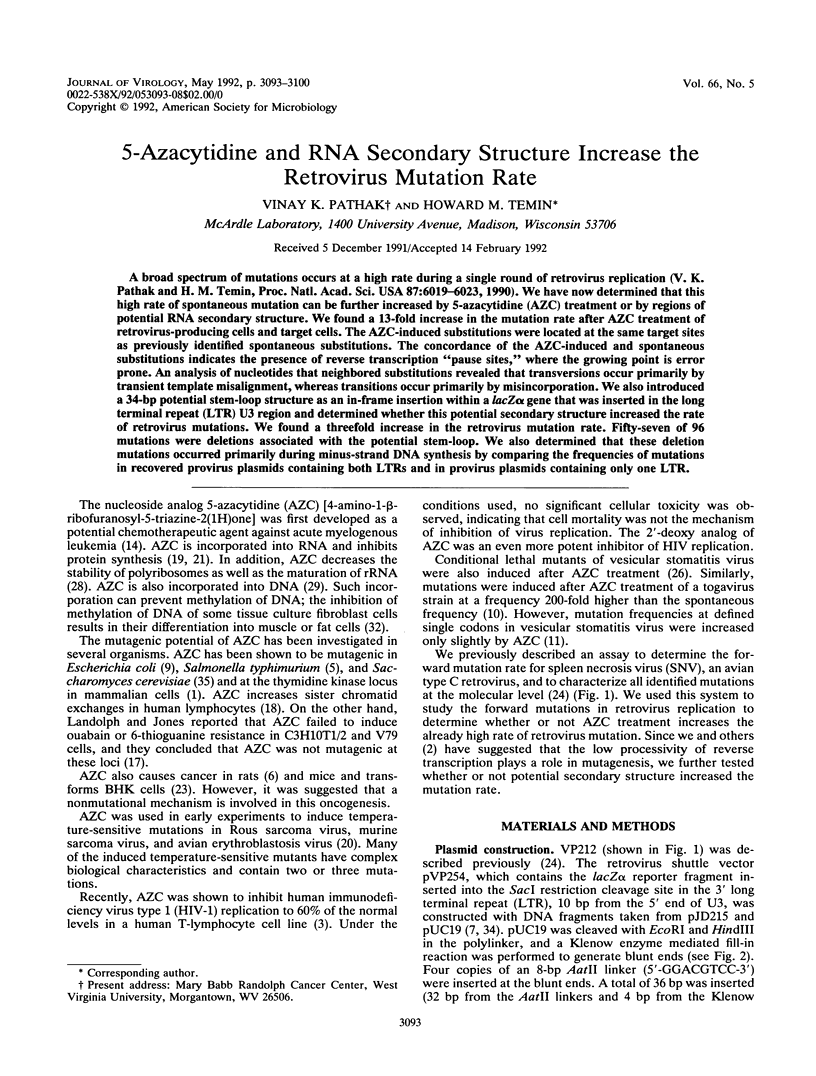

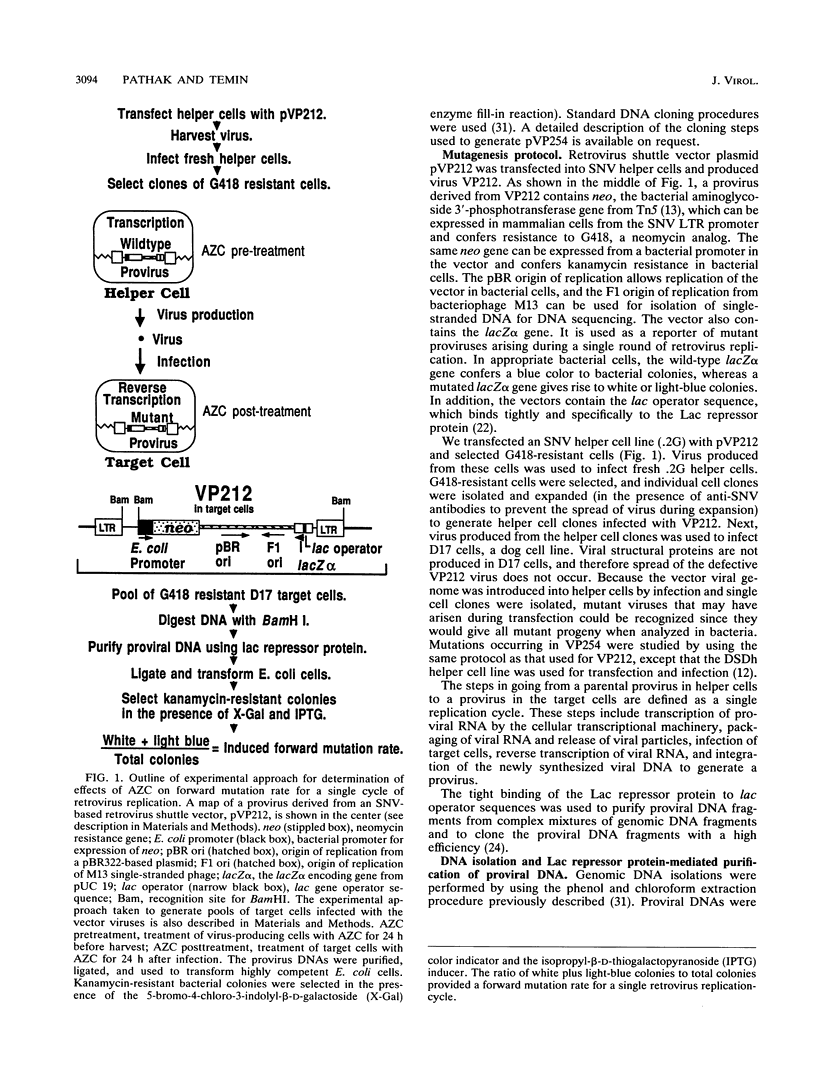

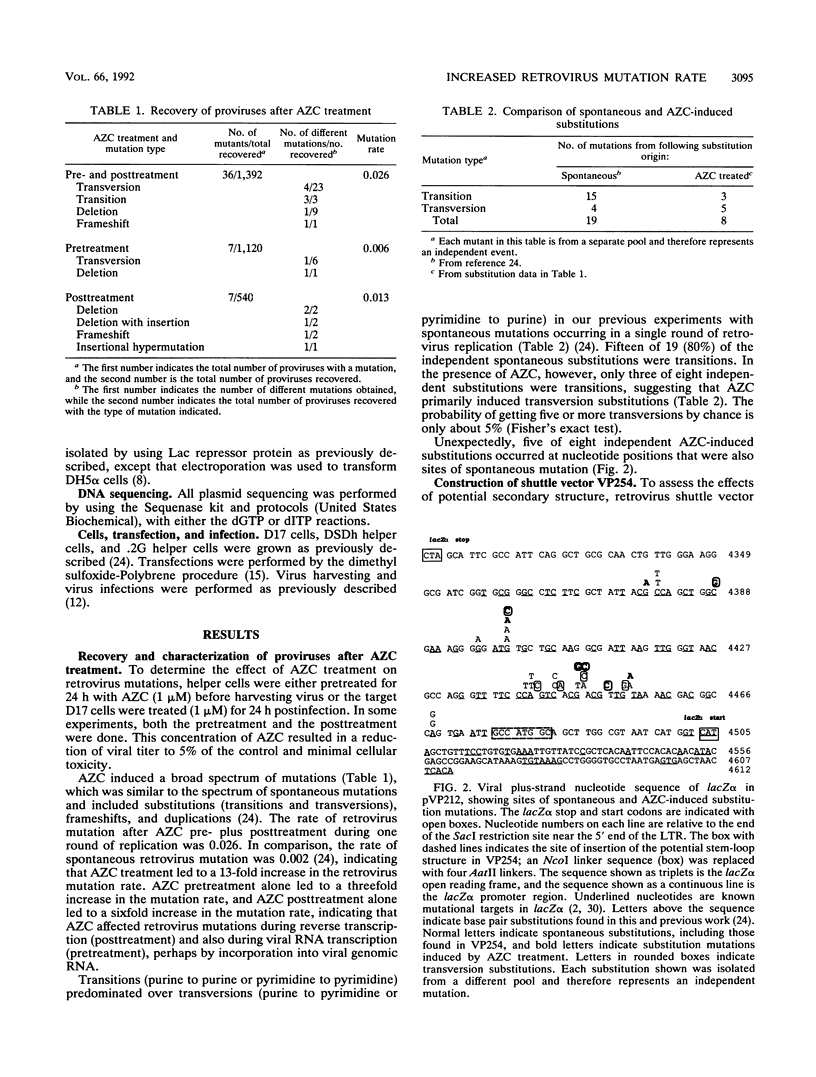

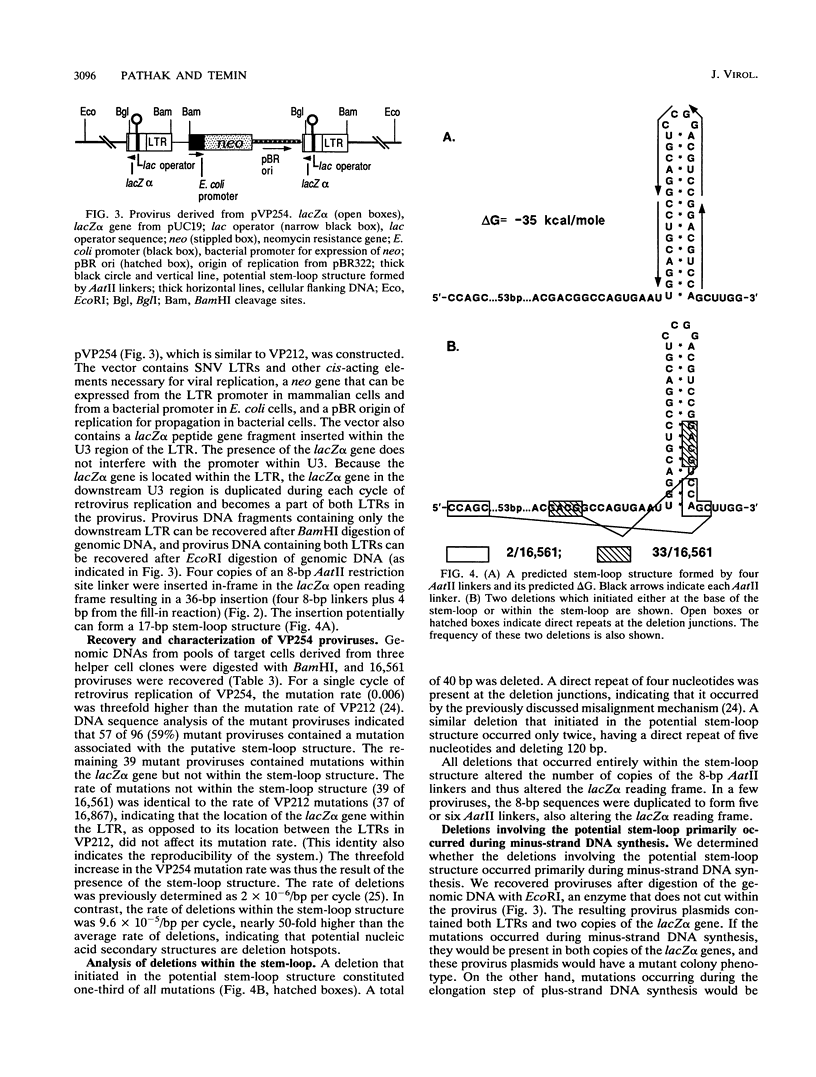

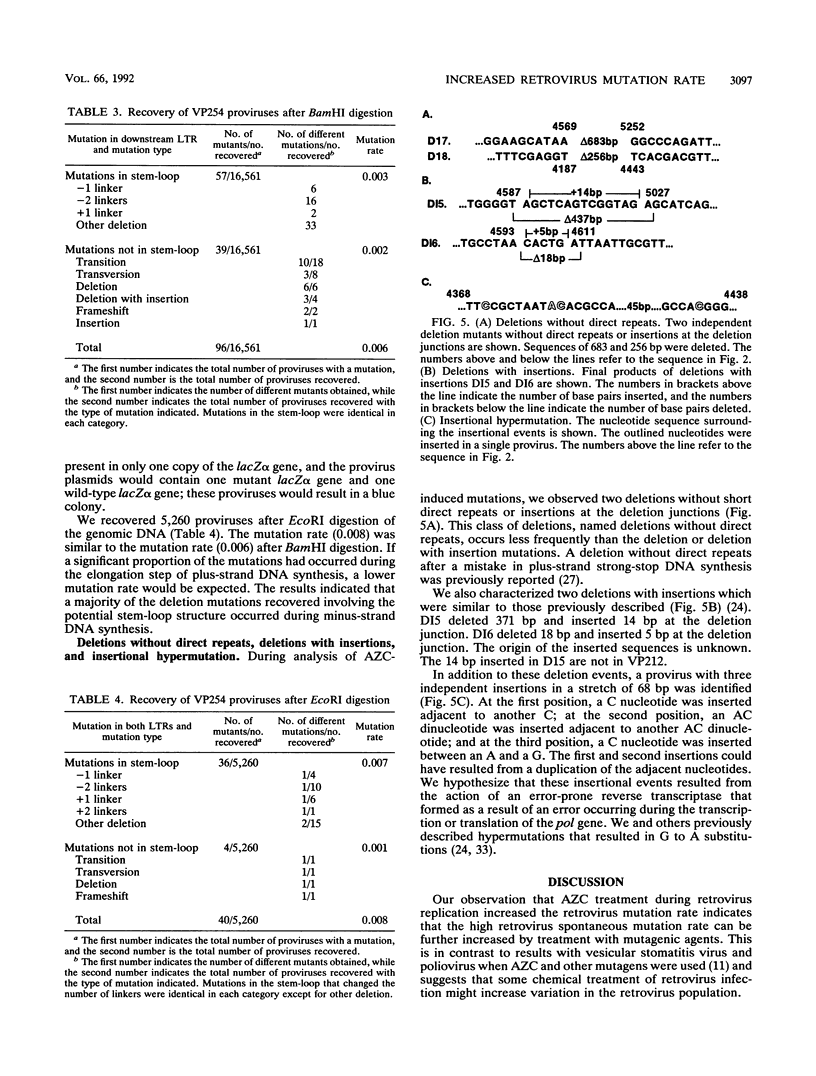

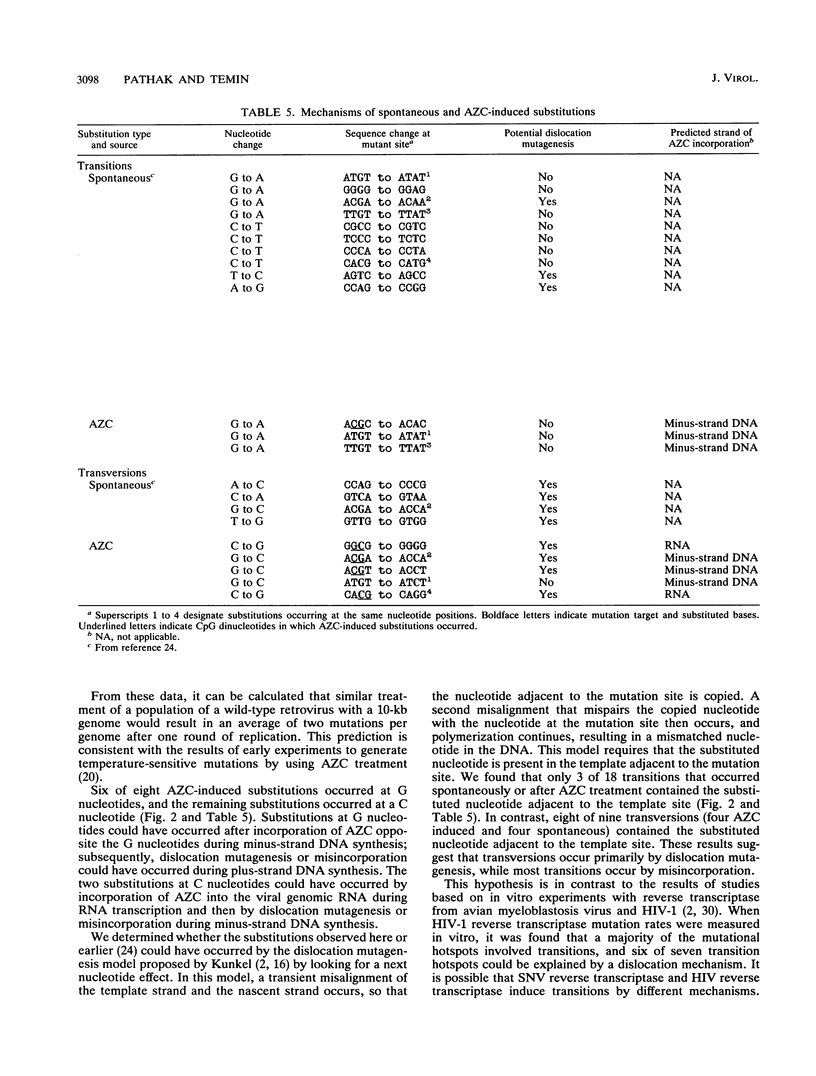

A broad spectrum of mutations occurs at a high rate during a single round of retrovirus replication (V.K. Pathak and H. M. Temin, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 87:6019-6023, 1990). We have now determined that this high rate of spontaneous mutation can be further increased by 5-azacytidine (AZC) treatment or by regions of potential RNA secondary structure. We found a 13-fold increase in the mutation rate after AZC treatment of retrovirus-producing cells and target cells. The AZC-induced substitutions were located at the same target sites as previously identified spontaneous substitutions. The concordance of the AZC-induced and spontaneous substitutions indicates the presence of reverse transcription "pause sites," where the growing point is error prone. An analysis of nucleotides that neighbored substitutions revealed that transversions occur primarily by transient template misalignment, whereas transitions occur primarily by misincorporation. We also introduced a 34-bp potential stem-loop structure as an in-frame insertion within a lacZ alpha gene that was inserted in the long terminal repeat (LTR) U3 region and determined whether this potential secondary structure increased the rate of retrovirus mutations. We found a threefold increase in the retrovirus mutation rate. Fifty-seven of 96 mutations were deletions associated with the potential stem-loop. We also determined that these deletion mutations occurred primarily during minus-strand DNA synthesis by comparing the frequencies of mutations in recovered provirus plasmids containing both LTRs and in provirus plasmids containing only one LTR.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Amacher D. E., Turner G. N. The mutagenicity of 5-azacytidine and other inhibitors of replicative DNA synthesis in the L5178Y mouse lymphoma cell. Mutat Res. 1987 Jan;176(1):123–131. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(87)90259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebenek K., Abbotts J., Roberts J. D., Wilson S. H., Kunkel T. A. Specificity and mechanism of error-prone replication by human immunodeficiency virus-1 reverse transcriptase. J Biol Chem. 1989 Oct 5;264(28):16948–16956. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouchard J., Walker M. C., Leclerc J. M., Lapointe N., Beaulieu R., Thibodeau L. 5-azacytidine and 5-azadeoxycytidine inhibit human immunodeficiency virus type 1 replication in vitro. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1990 Feb;34(2):206–209. doi: 10.1128/aac.34.2.206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouck N., Kokkinakis D., Ostrowsky J. Induction of a step in carcinogenesis that is normally associated with mutagenesis by nonmutagenic concentrations of 5-azacytidine. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Jul;4(7):1231–1237. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.7.1231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Call K. M., Jensen J. C., Liber H. L., Thilly W. G. Studies of mutagenicity and clastogenicity of 5-azacytidine in human lymphoblasts and Salmonella typhimurium. Mutat Res. 1986 May;160(3):249–257. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(86)90135-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr B. I., Reilly J. G., Smith S. S., Winberg C., Riggs A. The tumorigenicity of 5-azacytidine in the male Fischer rat. Carcinogenesis. 1984 Dec;5(12):1583–1590. doi: 10.1093/carcin/5.12.1583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty J. P., Temin H. M. High mutation rate of a spleen necrosis virus-based retrovirus vector. Mol Cell Biol. 1986 Dec;6(12):4387–4395. doi: 10.1128/mcb.6.12.4387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dower W. J., Miller J. F., Ragsdale C. W. High efficiency transformation of E. coli by high voltage electroporation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988 Jul 11;16(13):6127–6145. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.13.6127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halle S. 5-Azacytidine as a mutagen for arboviruses. J Virol. 1968 Oct;2(10):1228–1229. doi: 10.1128/jvi.2.10.1228-1229.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J. J., Domingo E., de la Torre J. C., Steinhauer D. A. Mutation frequencies at defined single codon sites in vesicular stomatitis virus and poliovirus can be increased only slightly by chemical mutagenesis. J Virol. 1990 Aug;64(8):3960–3962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.8.3960-3962.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu W. S., Temin H. M. Genetic consequences of packaging two RNA genomes in one retroviral particle: pseudodiploidy and high rate of genetic recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Feb;87(4):1556–1560. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.4.1556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorgensen R. A., Rothstein S. J., Reznikoff W. S. A restriction enzyme cleavage map of Tn5 and location of a region encoding neomycin resistance. Mol Gen Genet. 1979;177(1):65–72. doi: 10.1007/BF00267254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karon M., Sieger L., Leimbrock S., Finklestein J. Z., Nesbit M. E., Swaney J. J. 5-Azacytidine: a new active agent for the treatment of acute leukemia. Blood. 1973 Sep;42(3):359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawai S., Nishizawa M. New procedure for DNA transfection with polycation and dimethyl sulfoxide. Mol Cell Biol. 1984 Jun;4(6):1172–1174. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.6.1172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kunkel T. A., Alexander P. S. The base substitution fidelity of eucaryotic DNA polymerases. Mispairing frequencies, site preferences, insertion preferences, and base substitution by dislocation. J Biol Chem. 1986 Jan 5;261(1):160–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landolph J. R., Jones P. A. Mutagenicity of 5-azacytidine and related nucleosides in C3H/10T 1/2 clone 8 and V79 cells. Cancer Res. 1982 Mar;42(3):817–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavia P., Ferraro M., Micheli A., Olivieri G. Effect of 5-azacytidine (5-azaC) on the induction of chromatid aberrations (CA) and sister-chromatid exchanges (SCE). Mutat Res. 1985 May;149(3):463–467. doi: 10.1016/0027-5107(85)90164-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L. H., Olin E. J., Buskirk H. H., Reineke L. M. Cytotoxicity and mode of action of 5-azacytidine on L1210 leukemia. Cancer Res. 1970 Nov;30(11):2760–2769. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu L. J., Randerath K. Effects of 5-azacytidine on transfer RNA methyltransferases. Cancer Res. 1979 Mar;39(3):940–949. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mossing M. C., Record M. T., Jr Thermodynamic origins of specificity in the lac repressor-operator interaction. Adaptability in the recognition of mutant operator sites. J Mol Biol. 1985 Nov 20;186(2):295–305. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(85)90106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson L., Forchhammer J. Induction of the metastatic phenotype in a mouse tumor model by 5-azacytidine, and characterization of an antigen associated with metastatic activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Jun;81(11):3389–3393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.11.3389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pathak V. K., Temin H. M. Broad spectrum of in vivo forward mutations, hypermutations, and mutational hotspots in a retroviral shuttle vector after a single replication cycle: deletions and deletions with insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1990 Aug;87(16):6024–6028. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.16.6024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pringle C. R. Genetic characteristics of conditional lethal mutants of vesicular stomatitis virus induced by 5-fluorouracil, 5-azacytidine, and ethyl methane sulfonate. J Virol. 1970 May;5(5):559–567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.5.5.559-567.1970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulsinelli G. A., Temin H. M. Characterization of large deletions occurring during a single round of retrovirus vector replication: novel deletion mechanism involving errors in strand transfer. J Virol. 1991 Sep;65(9):4786–4797. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.9.4786-4797.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reichman M., Karlan D., Penman S. Destructive processing of the 45-S ribosomal precursor in the presence of 5-azacytidine. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1973 Feb 23;299(1):173–175. doi: 10.1016/0005-2787(73)90409-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riggs A. D., Jones P. A. 5-methylcytosine, gene regulation, and cancer. Adv Cancer Res. 1983;40:1–30. doi: 10.1016/s0065-230x(08)60678-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts J. D., Preston B. D., Johnston L. A., Soni A., Loeb L. A., Kunkel T. A. Fidelity of two retroviral reverse transcriptases during DNA-dependent DNA synthesis in vitro. Mol Cell Biol. 1989 Feb;9(2):469–476. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.2.469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor S. M., Jones P. A. Multiple new phenotypes induced in 10T1/2 and 3T3 cells treated with 5-azacytidine. Cell. 1979 Aug;17(4):771–779. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(79)90317-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vartanian J. P., Meyerhans A., Asjö B., Wain-Hobson S. Selection, recombination, and G----A hypermutation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 genomes. J Virol. 1991 Apr;65(4):1779–1788. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.4.1779-1788.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yanisch-Perron C., Vieira J., Messing J. Improved M13 phage cloning vectors and host strains: nucleotide sequences of the M13mp18 and pUC19 vectors. Gene. 1985;33(1):103–119. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(85)90120-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann F. K., Scheel I. Genetic effects of 5-azacytidine in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mutat Res. 1984 Jan;139(1):21–24. doi: 10.1016/0165-7992(84)90116-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]