Abstract

The three-dimensional structure of tRNA is organized into two domains—the acceptor-TΨC minihelix with the amino acid attachment site and a second, anticodon-containing, stem–loop domain. Aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases have a structural organization that roughly recapitulates the two-domain organization of tRNAs—an older primary domain that contains the catalytic center and interacts with the minihelix and a secondary, more recent, domain that makes contacts with the anticodon-containing arm. The latter contacts typically are essential for enhancement of the catalytic constant kcat through domain–domain communication. Methanococcus jannaschii tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase is a miniature synthetase with a tiny secondary domain suggestive of an early synthetase evolving from a one-domain to a two-domain structure. Here we demonstrate functional interactions with the anticodon-containing arm of tRNA that involve the miniaturized secondary domain. These interactions appear not to include direct contacts with the anticodon triplet but nonetheless lead to domain–domain communication. Thus, interdomain communication may have been established early in the evolution from one-domain to two-domain structures.

The L-shaped tertiary fold of tRNA consists of two distinct functional domains (1–3). The acceptor–TΨC minihelix domain contains the 3′-terminal amino acid attachment site. This domain in itself is a substrate for specific aminoacylation by many aminoacyl-tRNA synthetases (aaRSs) where sequences and structures in the acceptor stem confer specific recognition by an aaRS (4–14). The anticodon domain contains the anticodon triplet that interacts with the mRNA template in protein synthesis. The structures of the typical aaRSs consist of two major domains that interact, respectively, with the two domains of the tRNA (15–20). The older and highly conserved catalytic domain of the synthetase interacts with the acceptor-TΨC minihelix and is responsible for catalyzing amino acid attachment. The second, idiosyncratic, and more recent domain of the synthetase interacts with the anticodon arm of the tRNA.

Tyrosyl-tRNA synthetases (TyrRSs) are homodimeric enzymes consisting of an N-terminal active site domain and a C-terminal anticodon-binding domain. In bacterial TyrRSs, contacts outside of the TΨC-minihelix are made between the last third of the enzyme’s C-domain and the anticodon-containing domain of the tRNA (21–24). In particular, the central nucleotide of the anticodon (U36) has been shown to be a strong element for tRNA recognition in bacteria and yeast (25–27).

Methanococcus jannaschii TyrRS is a miniature homodimeric synthetase, significantly shorter than its bacterial counterparts (306 versus ca. 420 amino acids). Its small size is due to the absence of a significant portion of the C-domain. In particular, the anticodon-binding region in the C-domain of the bacterial enzymes is completely omitted from the M. jannaschii TyrRS sequence (28). Consistent with the absence of this anticodon-binding region, the central anticodon nucleotide (U36) is not a major recognition element for M. jannaschii TyrRS (29).

In the typical synthetase–tRNA complex, activity of aminoacylation is significantly enhanced by domain–domain communication. These are complexes where the second domain of the synthetase is not miniaturized as it is in the case of the M. jannaschii enzyme. This communication involves the transmission of a signal from an interaction at the anticodon triplet back to the active site that results in an elevation in kcat (30–34). Examples include the complex of Escherichia coli glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase (GlnRS) with tRNAGln (15) and yeast aspartyl-tRNA synthetase (AspRS) with tRNAAsp (35, 36). In these instances, the interaction of the second domain of the synthetase with the anticodon triplet has been resolved by x-ray crystallography and involves a significant conformational change at the anticodon. Another example is E. coli methionyl-tRNA synthetase, where the favorable interaction free energy with the anticodon is directly responsible for raising by several orders of magnitude the kcat for aminoacylation of the full tRNA (37–40). Thus, domain–domain communication is well established in contemporary synthetase-tRNA systems.

We recently demonstrated that an RNA substrate based on the acceptor-TΨC minihelix of M. jannaschii tRNATyr was specifically aminoacylated with tyrosine by M. jannaschii TyrRS (29). Although the minihelix is a substrate for specific aminoacylation by the M. jannaschii enzyme, the tRNA is aminoacylated more efficiently than the minihelix, thus indicating that interactions with the anticodon-containing domain are important for activity. Given that M. jannaschii TyrRS has an especially small C-domain, we were interested in determining whether domain–domain communication could be demonstrated. The strategy was to identify a part of the miniature C-domain that might be needed for elevation of kcat for charging the full tRNA but not for charging the minihelix. In this way, we hoped to gain insight into whether domain–domain communication was established even in synthetases with the smallest of C-domains. If so, then the possibility of domain–domain signaling being an early event in the historical assembly of the synthetase-tRNA complex would have added credence.

Materials and Methods

Mutant Construction and Enzyme and RNA Preparation.

Amino acid replacements in M. jannaschii TyrRS were made by site-directed mutagenesis of the tyrS gene of plasmid pBAS50 (29). Codon changes and an adjacent NcoI restriction site were introduced simultaneously by overlap-extension-PCR-mutagenesis using the Quikchange site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene). The new NcoI restriction site (that did not change the encoded amino acid) facilitated screening for mutant plasmids. The resulting mutant plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing. Wild-type and mutant enzymes were expressed in E. coli and purified as described previously (29). Synthetic M. jannaschii tRNATyr and minihelixTyr (Fig. 1) were prepared as described earlier (29).

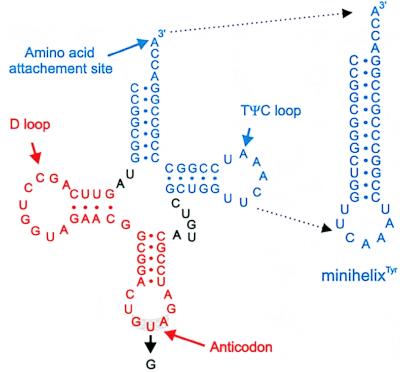

Figure 1.

Sequence and cloverleaf structure of M. jannaschii tRNATyr (46), showing the formation of the L-shaped tertiary fold together with the minihelix. The sequences of the tRNA and minihelix correspond to the synthetic RNAs studied here. The tRNA has two main domains: the TΨC minihelix domain (blue) and the anticodon domain (red). The position of the central anticodon mutation in the tRNA is indicated.

Enzymatic Assays and Kinetic Analysis.

Aminoacylation assays were performed as outlined previously (29) at 45°C in a reaction mixture consisting of 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 1 mM 1,4-dithiothreitol, 10 mM MgCl2, 2.5 mM ATP, 100 μM tyrosine, 0.04 μCi/μl [3H]tyrosine (1 μCi = 37 kBq), and 5–60 μM tRNA or 20–160 μM minihelix. Reactions were initiated with the addition of TyrRS (typically 0.25–2.5 μM for tRNA aminoacylation and 2.5–15 μM enzyme for minihelix aminoacylation. Kinetic parameters (kcat and Km) for aminoacylation were determined two or more times by direct fitting of the Michaelis–Menten equation by nonlinear regression analysis (41) using MicroCal Origin (MicroCal Software, Northampton, MA). The concentration of RNA was varied at least 10-fold for the determination of kinetic parameters. In cases where kcat and Km could not be reliably determined directly (because of concentration limitations of the RNA substrate), kcat/Km was estimated from the slope of a double-reciprocal plot.

Tyrosyl adenylate synthesis was measured by the tyrosine-dependent ATP–pyrophosphate (PPi) exchange assay at 45°C as described earlier (42). The reaction mixture contained 50 mM sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 10 mM KF, 7 mM 2-mercaptoethanol, 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM ATP, 2 mM NaPPi, 1 mM tyrosine, 0.1 mg/ml BSA, and approximately 0.01 μCi/μl Na[32P]PPi. Reactions were initiated with the addition of TyrRS (250 nM final concentration).

Results

Identification of a Conserved C-Terminal Motif.

The class-defining bacterial, eukaryote and archaebacterial N-terminal core of TyrRSs extends for approximately 220 amino acids. The catalytic core is followed by a C-domain that, in bacteria and eukaryotes, is made up of approximately 180−300 residues. Thus, the total length of the bacterial and eukaryotic TyrRSs is about 400−530 amino acids.

The class-defining N-terminal domain of M. jannaschii TyrRS shares 40% sequence identity with human TyrRS, whereas it has a 22% identity with the Bacillus stearothermophilus enzyme. This comparison is consistent with archaebacterial aaRSs in general sharing significantly more sequence similarity with the eukaryotic synthetases than with the bacterial enzymes (43). The C-domain of bacterial TyrRSs extends approximately 180 amino acids beyond the nucleotide-binding fold of the active site domain. In contrast, the C-domain of the archaebacterial M. jannaschii enzyme extends a mere 90 amino acids beyond the active site domain. Thus, a relatively short stretch of amino acids is available for functional contacts with the anticodon-containing domain of the tRNA.

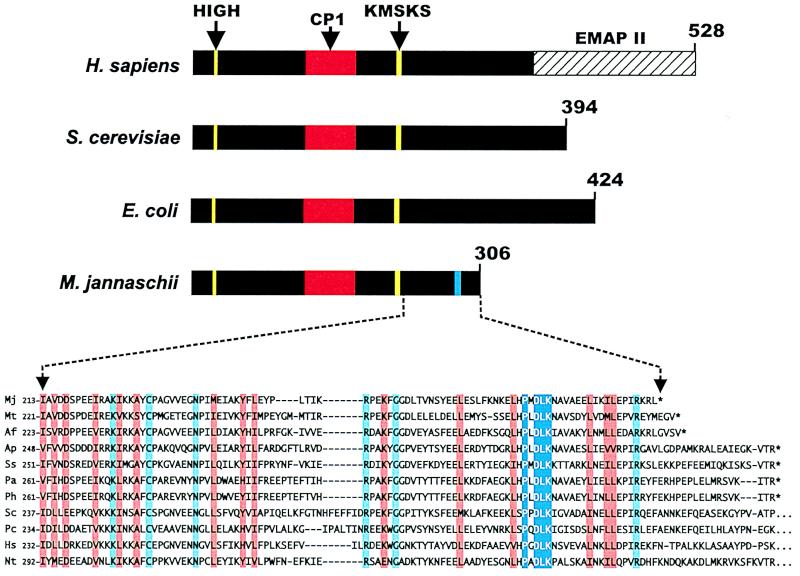

To identify residues that might be important for tRNA recognition, we examined the C-terminal portion of the M. jannaschii TyrRS by multiple sequence alignment (44, 45). Specifically, we aligned all available archaebacterial amino acid sequences of TyrRS with a broad representation of eukaryote sequences from mammalian, plant, protozoan, and yeast organisms. The alignment showed that, while the archaebacterial sequences of the C-domain were foreshortened, they were clearly related to those from mammalian, plant, protozoan, and yeast sources. Within this multiple sequence alignment, a distinct cluster of conserved residues was identified with the sequence PXDLK that, in the M. jannaschii enzyme, is located at the extreme C terminus (Fig. 2). It encompasses the only cluster of contiguous residues in the C-domain. This PXDLK motif is strictly conserved in all reported archaebacterial and eukaryotic TyrRS sequences. It is not found in any bacterial TyrRS sequences (data not shown).

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram illustrating the primary structures of human, E. coli, and M. jannaschii TyrRSs and alignment of the C-domains. CP1, connective polypeptide 1. The hatched bar shows the C-terminal endothelial monocyte-activating protein II (EMAP II) extension of human TyrRS (28, 54). The C-terminal domain of M. jannaschii TyrRS is shown aligned with all other available archaebacterial TyrRS sequences and representative eukaryotic TyrRS sequences. Archaebacterial sequences: Af, Archaeoglobus fulgidus; Ap, Aeropyrum pernix; Mj, Methanococcus jannaschii; Mt, Methanobacterium thermoautotrophicum; Pa, Pyrococcus abyssi; Ph, Pyrococcus horikoshii; Ss, Sulfolobus solfataricus. Eukaryotic sequences: Hs, Homo sapiens; Nt, Nicotiana tabacum; Pc, Pneumocystis carinii; Sc, Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The C-domain alignment shown is the result of multiple sequence alignment of full-length TyrRS sequences by using clustal (44, 45).

Effect on Activity of Amino Acid Substitutions in the C-Domain.

The strict conservation of the PXDLK motif is suggestive of a functional role. Because it occurs outside of the catalytic domain, a role in tRNA recognition and, additionally or alternatively, domain–domain communication is suggested. The location of these residues near the C-domain terminus of M. jannaschii TyrRS allows for the possibility of functional interactions with the anticodon-containing domain of the tRNA. To test the potential role of this sequence, we focused on side chains with functional groups (the D286 carboxylate and the K288 amino group) that might interact with other parts of the protein or with the tRNA substrate through electrostatic, salt-bridge-like, or hydrogen-bond interactions.

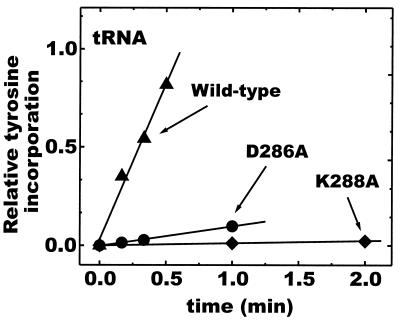

For this purpose we prepared D286A and K288A mutant enzymes and proceeded to test aminoacylation of tRNATyr by the mutant enzymes. [Like the wild-type enzyme (29), the mutant enzymes were stably overexpressed in E. coli, highly thermostable, and readily purified.] Both mutations significantly attenuated the rate of aminoacylation of tRNATyr at 45°C (Fig. 3). [The temperature of 45°C was chosen for technical convenience. The M. jannaschii enzyme is active in vitro up to at least 85°C (29).] Specifically, the rate of aminoacylation was reduced more than 10-fold by the D286A substitution and was diminished by more than 200-fold with the K288A mutation.

Figure 3.

Comparison of aminoacylation of tRNATyr with wild-type and D286A and K288A mutant TyrRS. Activity was assayed at pH 7.5 and 45°C.

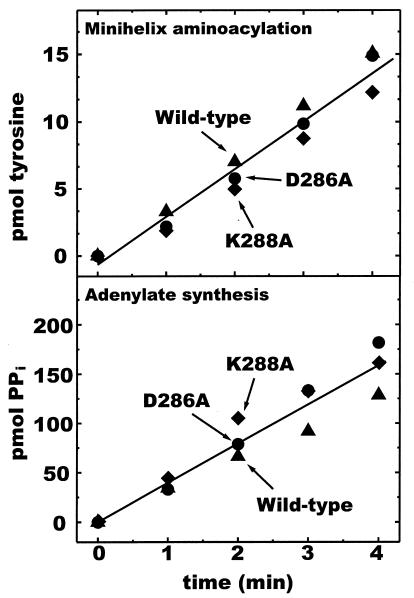

aaRSs catalyze a two-step reaction: amino acid activation followed by transfer of the activated amino acid to the 3′ end of the tRNA. To determine whether the mutations affected amino acid activation or the tRNA-dependent step of aminoacylation, we tested tyrosyl adenylate synthesis by using the tyrosine-dependent ATP–PPi exchange assay. Adenylate synthesis activity of the mutant enzymes was equivalent to wild-type activity (Fig. 4 Upper). Because these mutations do not alter adenylate synthesis, their effect on aminoacylation can be attributed specifically to the tRNA-dependent step.

Figure 4.

Comparison of wild-type and mutant TyrRS amino acid activation activities and aminoacylation of minihelixTyr. Rate of aminoacylation of minihelixTyr (Upper) and of tyrosine-dependent ATP–PPi exchange (Lower) with the wild-type enzyme is the same as that with the mutant enzymes. Activity was assayed at pH 7.5 and 45°C.

Aminoacylation Kinetics of MinihelixTyr and tRNATyr.

Because we imagined that D286 and K288 might be involved in functional contacts with parts of the tRNA outside of the TΨC-minihelix domain, we investigated aminoacylation of minihelixTyr by the mutant enzymes. As expected, the rate of minihelix aminoacylation relative to the wild-type enzyme was unchanged by the D286A and K288A mutations (Fig. 4 Lower). Kinetic analysis confirmed (over an 8-fold range of concentration of minihelixTyr) that the C-terminal mutations in M. jannaschii TyrRS do not affect the TΨC-minihelix functional interaction with TyrRS. Thus, both mutant and wild-type enzymes have comparable apparent kcat/Km values for minihelix aminoacylation (Table 1). Given that the D286A and K288A substitutions have no effect on minihelix aminoacylation, we conclude that the deleterious effect of these mutations on aminoacylation of tRNA is specifically associated with the L-shaped structure of the full tRNA.

Table 1.

Values of kcat/Km for tyrosine aminoacylation of minihelixTyr by wild-type, D286A, and K288A M. jannaschii TyrRSs

| Enzyme |

kcat/Km

|

|

|---|---|---|

| 104 s−1⋅M−1 | Fold change* | |

| Wild type | 9.1 × 10−4 | 1,100 |

| D286A | 9.5 × 10−4 | 1,100 |

| K288A | 8.2 × 10−4 | 1,200 |

kcat/Km was measured at pH 7.5 and 45°C.

*Values are relative to wild-type tRNATyr aminoacylation (see Table 2).

To further investigate the effects of the D286A and K288A mutations on aminoacylation of tRNATyr, we determined the kinetics of aminoacylation with the wild-type and mutant synthetases. Kinetic analysis showed that the reduction in rate of aminoacylation by the D286A mutant enzyme resulted from a roughly 10-fold decrease in kcat, with no significant change in Km. Thus, the change in kcat accounts entirely for the 10-fold change in kcat/Km (Table 2). Although we were not able to directly measure individual kcat and Km parameters for the K288A mutant enzyme (see Materials and Methods) because of the low aminoacylation activity, the ratio kcat/Km was reduced by more than 200-fold.

Table 2.

Kinetic parameters for aminoacylation of wild-type and U36G tRNATry transcripts by wild-type, D286A, and K288A M. jannaschii TyrRSs

| tRNATyr | Enzyme | kcat, 10−2 s−1 | Km, μM |

kcat/Km

|

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104 s−1⋅M−1 | Fold change | ||||

| Wild type | Wild type | 15 ± 1 | 15 ± 3 | 1.0 | 1.0 |

| D286A | 1.6 ± 0.1 | 16 ± 3 | 0.10 | 10 | |

| K288A | ND | ND | 4.3 × 10−3 | 230 | |

| U36G | Wild type | 2.0 ± 0.02 | 12 ± 4 | 0.17 | 6.0 |

| D286A | 0.34 ± 0.03 | 13 ± 4 | 0.026 | 38 | |

| K288A | ND | ND | 9.8 × 10−3 | 110 | |

Values of kcat and Km and kcat/Km were measured two or more times at pH 7.5 and 45°C. The average standard error obtained from nonlinear regression is shown. ND, not determined.

Effect of a U36G Substitution in tRNATyr.

U36 is the central nucleotide of the anticodon of tyrosine tRNAs (46). It plays an important role in determining the efficiency of aminoacylation of bacterial tRNATyr (26). That role includes a significant functional contact, as judged by the detailed molecular model of the complex of the bacterial enzyme with tRNATyr (21–24) and by the significantly elevated Km for aminoacylation that occurs with a U36G substitution (26). In addition, in cases such as E. coli GlnRS and yeast AspRS where the anticodon triplet plays a significant role in tRNA recognition (30–34) and where a cocrystal of a tRNA with its synthetase has been determined, the central base interacts prominently with the enzyme (15, 35, 36). For these reasons, we thought that the sensitivity of the M. jannaschii TyrRS to a substitution of this nucleotide would be a valid test of the role of the anticodon in aminoacylation.

We showed earlier that a U36G anticodon mutation in tRNATyr did not affect the Km for tRNA in the aminoacylation reaction (29). This observation is consistent with no direct contact between U36 and the enzyme, presumably because the segment of protein that contacts U36 is missing from the archaebacterial protein. The U36G mutation caused a relatively small decrease (6-fold) in kcat of M. jannaschii TyrRS, suggesting that the conformation of the anticodon might play a small role in aminoacylation.

To understand more about the relationships, if any, between D286 and K288 in M. jannaschii TyrRS and U36 in tRNATyr, we investigated the kinetics of aminoacylation of the U36G tRNATyr by the two mutant enzymes. Relative to the wild-type enzyme and wild-type tRNA, aminoacylation of the U36G tRNA by the D286A synthetase is reduced by approximately 40-fold as measured by kcat/Km. This change (40-fold) is comparable to the ≈60-fold expected if the effects of the U36G and D286A substitutions on the apparent free energy of transition state stabilization [−RT ln(kcat/Km) (5, 47, 48)] were additive. These results support the conclusion that no direct contact occurs between U36 and D286 of M. jannaschii TyrRS. Indeed, the Km of the wild-type and D286A enzymes for tRNATyr and U36G tRNATyr are the same (Table 2). Thus, the entire effect of both the U36G mutation in tRNATyr and the D286A substitution in TyrRS is on kcat, that is, on communication from the second domain of the synthetase and tRNA back to the catalytic center.

The kcat/Km for aminoacylation of U36G tRNATyr by the K288A enzyme is reduced by only 110-fold compared with the kcat/Km for wild-type protein. If the free energy contributions associated with the respective mutations were additive, then an approximately 1200-fold decrease in charging efficiency would be predicted. Thus, the K288A substitution provides some [∼ −RT ln(1200/110) ≈ −1.4 kcal⋅mol−1] serendipitous compensation for the U36G substitution, probably through an effect on the efficiency of domain–domain communication.

Discussion

In this work we established that the D286A and K288A mutations in the mini-C-domain of M. jannaschii TyrRS have no effect on adenylate synthesis or on the rate of aminoacylation of minihelixTyr. Thus, D286 and K288 have no direct influence on the catalytic center of the enzyme and provide no functional contacts with the minihelix domain. On the other hand, these same mutations severely reduced the rate of charging of the full tRNA. In the case of the D286A mutation, the reduction is entirely due to a lowering of kcat (Table 2). Because the kcat effect of this mutation is seen only with the full tRNA, we conclude that D286 plays a role in communicating information in the second domain of tRNA back to the catalytic center. Most likely, K288 plays a similar role.

It has been shown for B. stearothermophilus TyrRS that binding of tRNA occurs across the dimer interface. The active site of one subunit binds the acceptor stem while the C-domain of the other interacts with the anticodon (21–24). The dimer interface in TyrRSs involves the first half of CP1, a peptide insertion in the conserved active site domain (49–52) that is found in all known sequences of TyrRS. In both eukaryotic and bacterial TyrRSs, the second half of CP1 has been shown to make critical sequence-specific contacts with the 1⋅72 acceptor stem base pair of tRNA (13).

We recently showed that M. jannaschii TyrRS is also a dimeric enzyme and that it has stringent specificity for the 1⋅72 base pair. Therefore, it can be conjectured that the tRNA acceptor stem in the M. jannaschii TyrRS–tRNATyr complex docks onto the catalytic domain in a manner analogous to that of the bacterial and eukaryotic enzymes. As such, we surmise that tRNA binding in M. jannaschii TyrRS also occurs across the dimer interface. Thus, domain–domain signaling of the C-domain back to the catalytic center would be manifested through cross-subunit communication. The C-domain could influence the tRNA acceptor stem conformation in the active site through domain–domain communication that is transmitted through the dimer interface at CP1.

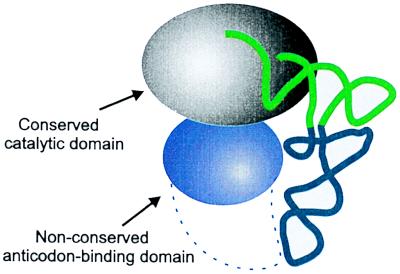

If we view the M. jannaschii TyrRS as an example of a synthetase in transition from a one-domain to a two-domain structure (Fig. 5), then the present experiments suggest that domain–domain communication was established early in the development of the two-domain structures of these enzymes. This sort of communication would provide strong selective pressure to build out the second domain of the synthetase, perhaps contemporaneously with the second domain of the tRNA being established. Because the secondary domain of the synthetase is typically idiosyncratic to the synthetase (unlike the class-defining active site domain that is shared by all synthetases in the same class), it is not surprising that the sequence of the small 90 amino acid C-domain of TyrRS is not found in other synthetases or, for that matter, in other proteins whose sequences have been reported thus far. That this small piece is included as a part of the C-domain of the eukaryote TyrRSs suggests the possibility that the full C-domain was assembled in a piece-wise fashion, perhaps starting with the segment found in the M. jannaschii enzyme.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of the synthetase–tRNA complex. Only the general topology of the complex is implied. The model shows the tRNA interacting with the two domains. The conserved catalytic domain interacts with the acceptor helix. The nonconserved domain contacts the anticodon-containing domain of the tRNA and in many cases it is large enough to contact the anticodon triplet as indicated by the dashed line [examples include GlnRS (15) and AspRS (17)]. The C-domain of M. jannaschii TyrRS is too small to make direct contacts with the anticodon triplet. In bacterial and eukaryotic TyrRSs the C-domain is much larger, enabling contacts with the triplet (dashed line).

Interestingly, the mammalian tyrosine enzymes have an additional C-terminal segment that is not found in prokaryote, other eukaryote, or archaebacterial TyrRSs (Fig. 2) (53). This segment is homologous to the cytokine EMAP II (28). This EMAP II-like addition is released from full-length mammalian TyrRS by proteases such as leukocyte elastase (53). The released C-domain has potent activity for leukocyte and monocyte chemotaxis and stimulates production of tissue factor, myeloperoxidase, and tumor necrosis factor α (53, 54). In contrast, the full-length protein has none of these activities. Similarly, the catalytic body of mammalian TyrRS (mini TyrRS) that is released from the EMAP II-like domain by proteolysis is an IL-8-like cytokine. The IL-8-like activities are blocked in the full-length protein. These experiments showed that, in the full-length protein, a form of domain–domain communication sequesters the cytokine activities of mini TyrRS and the EMAP II-like domain (53, 54). Thus, the principle of domain–domain communication in TyrRS has a long evolutionary history that extends from early to late organisms and that goes beyond the aminoacylation activities of these enzymes.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Carme Fabrega for assistance with chemical RNA synthesis and to Dr. Karin Musier-Forsyth for providing plasmid pLYSF119 for cloning and in vitro transcription of tRNATyr. We thank Drs. Joseph Chihade and Tamara Hendrickson for critically reviewing the manuscript. This work was supported by Grants GM15539 and GM23562 from the National Institutes of Health. B.A.S. was supported by a postdoctoral fellowship from the Medical Research Council of Canada.

Abbreviations

- aaRS

aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase

- AspRS

aspartyl-tRNA synthetase

- CP1

connective polypeptide 1

- EMAP II

endothelial monocyte-activating protein II

- GlnRS

glutaminyl-tRNA synthetase

- TyrRS

tyrosyl-tRNA synthetase

References

- 1.Kim S H, Quigley G J, Suddath F L, McPherson A, Sneden D, Kim J J, Weinzierl J, Rich A. Science. 1973;179:285–288. doi: 10.1126/science.179.4070.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kim S H, Suddath F L, Quigley G J, McPherson A, Sussman J L, Wang A H, Seeman N C, Rich A. Science. 1974;185:435–440. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4149.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ladner J E, Jack A, Robertus J D, Brown R S, Rhodes D, Clark B F, Klug A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1975;72:4414–4418. doi: 10.1073/pnas.72.11.4414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Francklyn C, Schimmel P. Nature (London) 1989;337:478–481. doi: 10.1038/337478a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Francklyn C, Musier-Forsyth K, Schimmel P. Eur J Biochem. 1992;206:315–321. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1992.tb16929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Frugier M, Florentz C, Giegé R. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:3990–3994. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.9.3990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nureki O, Niimi T, Muto Y, Kanno H, Kohno T, Muramatsu T, Kawai G, Miyazawa T, Giegé R, Florentz C, Yokoyama S. In: The Translational Apparatus. Nierhaus K, Franceschi F, Subramanian F, Erdmann A, editors. New York: Plenum; 1993. pp. 59–66. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frugier M, Florentz C, Giegé R. EMBO J. 1994;13:2219–2226. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06499.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamann C S, Hou Y M. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6527–6532. doi: 10.1021/bi00019a034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Martinis S A, Schimmel P. In: tRNA: Structure, Biosynthesis, and Function. Söll D, RajBhandary U L, editors. Washington, DC: Am. Soc. Microbiol. Press; 1995. pp. 349–370. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Quinn C L, Tao N, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12489–12495. doi: 10.1021/bi00039a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saks M E, Sampson J R. EMBO J. 1996;15:2843–2849. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wakasugi K, Quinn C L, Tao N, Schimmel P. EMBO J. 1998;17:297–305. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Musier-Forsyth K, Schimmel P. Acc Chem Res. 1999;32:368–375. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rould M A, Perona J J, Söll D, Steitz T A. Science. 1989;246:1135–1142. doi: 10.1126/science.2479982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cusack S. Biochimie. 1993;75:1077–1081. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(93)90006-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cavarelli J, Eriani G, Rees B, Ruff M, Boeglin M, Mitschler A, Martin F, Gangloff J, Thierry J C, Moras D. EMBO J. 1994;13:327–337. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06265.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schimmel P. J Mol Evol. 1995;40:531–536. doi: 10.1007/BF00166621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schimmel P, Giegé R, Moras D, Yokoyama S. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:8763–8768. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schimmel P, Ribas de Pouplana L. Cell. 1995;81:983–986. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80002-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bedouelle H, Winter G. Nature (London) 1986;320:371–373. doi: 10.1038/320371a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carter P, Bedouelle H, Winter G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:1189–1192. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.5.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ward W H, Fersht A R. Biochemistry. 1988;27:5525–5530. doi: 10.1021/bi00415a021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bedouelle H. Biochimie. 1990;72:589–598. doi: 10.1016/0300-9084(90)90122-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bare L A, Uhlenbeck O C. Biochemistry. 1986;25:5825–5830. doi: 10.1021/bi00367a072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Himeno H, Hasegawa T, Ueda T, Watanabe K, Shimizu M. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6815–6819. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.23.6815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee C P, RajBhandary U L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11378–11382. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kleeman T A, Wei D, Simpson K L, First E A. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:14420–14425. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.22.14420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Steer, B. A. & Schimmel, P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem.274, in press. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Jahn M, Rogers M J, Söll D. Nature (London) 1991;352:258–260. doi: 10.1038/352258a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pütz J, Puglisi J D, Florentz C, Giegé R. Science. 1991;252:1696–1699. doi: 10.1126/science.2047878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pütz J, Puglisi J D, Florentz C, Giegé R. EMBO J. 1993;12:2949–2957. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05957.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rogers M J, Adachi T, Inokuchi H, Söll D. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:291–295. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.1.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eriani G, Gangloff J. J Mol Biol. 1999;291:761–773. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ruff M, Krishnaswamy S, Boeglin M, Poterszman A, Mitschler A, Podjarny A, Rees B, Thierry J C, Moras D. Science. 1991;252:1682–1689. doi: 10.1126/science.2047877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cavarelli J, Rees B, Ruff M, Thierry J C, Moras D. Nature (London) 1993;362:181–184. doi: 10.1038/362181a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schulman L H, Pelka H. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1983;80:6755–6759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.22.6755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ghosh G, Pelka H, Schulman L H. Biochemistry. 1990;29:2220–2225. doi: 10.1021/bi00461a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H Y, Pelka H, Brunie S, Schulman L H. Biochemistry. 1993;32:10506–10511. doi: 10.1021/bi00090a029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gale A J, Shi J P, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1996;35:608–615. doi: 10.1021/bi9520904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dardel F. Comput Appl Biosci. 1994;10:273–275. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/10.3.273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steer B A, Schimmel P. Biochemistry. 1999;38:4965–4971. doi: 10.1021/bi990038s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bult C J, White O, Olsen G J, Zhou L, Fleischmann R D, Sutton G G, Blake J A, FitzGerald L M, Clayton R A, Gocayne J D, et al. Science. 1996;273:1058–1073. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5278.1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thompson J D, Gibson T J, Plewniak F, Jeanmougin F, Higgins D G. Nucleic Acids Res. 1997;25:4876–4882. doi: 10.1093/nar/25.24.4876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sprinzl M, Horn C, Brown M, Ioudovitch A, Steinberg S. Nucleic Acids Res. 1998;26:148–153. doi: 10.1093/nar/26.1.148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fersht A. Enzyme Structure and Mechanism. San Francisco: Freeman; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hammes G. Enzyme Catalysis and Regulation. New York: Academic; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Irwin M J, Nyborg J, Reid B R, Blow D M. J Mol Biol. 1976;105:577–586. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(76)90236-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brick P, Blow D M. J Mol Biol. 1987;194:287–297. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(87)90376-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Starzyk R M, Webster T A, Schimmel P. Science. 1987;237:1614–1618. doi: 10.1126/science.3306924. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Brick P, Bhat T N, Blow D M. J Mol Biol. 1988;208:83–98. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(89)90090-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. Science. 1999;284:147–151. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5411.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wakasugi K, Schimmel P. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:23155–23159. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.33.23155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]