Abstract

Summary

Endocytosis of activated receptors can control signaling levels by exposing the receptors to novel downstream molecules or by leading to their degradation. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) signaling has critical roles in development and is misregulated in many cancers. We report here that Myopic, the Drosophila homologue of the Bro1-domain tyrosine phosphatase HD-PTP, promotes EGFR signaling in vivo and in cultured cells. myopic is not required in the presence of activated Ras or the absence of the ubiquitin ligase Cbl, indicating that it acts on internalized EGFR, and its overexpression enhances the activity of an activated form of the EGFR. Myopic is localized to intracellular vesicles adjacent to Rab5-containing early endosomes, and its absence results in the enlargement of endosomal compartments. Loss of Myopic prevents cleavage of the EGFR cytoplasmic domain, a process controlled by the endocytic regulators Cbl and Sprouty. We suggest that Myopic promotes EGFR signaling by mediating its progression through the endocytic pathway.

Keywords: ESCRT complex, MAP kinase, HD-PTP, Bro1 domain, photoreceptor

Introduction

The epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) is required for cell differentiation and proliferation in numerous developmental systems (Shilo, 2003), and activation of the human EGFR homologs, ErbB1-4, is implicated in many cancers (Hynes and Lane, 2005). EGFR signaling events are terminated following removal of the receptor from the cell membrane by endocytosis. Ubiquitination of the EGFR by Cbl, an E3 ubiquitin ligase, initiates its internalization into clathrin-coated vesicles (Swaminathan and Tsygankov, 2006) and its transit through early and late endosomes, which differ by the exchange of Rab7 for Rab5 (Rink et al., 2005). The EGFR can either return to the cell surface in Rab11-containing recycling endosomes, or reach the lysosome for degradation (Dikic, 2003; Seto et al., 2002). Delivery of receptors to the lysosome requires sorting from the limiting membrane of late endosomes into the internal vesicles of multivesicular bodies (MVBs)(Gruenberg and Stenmark, 2004), a process mediated by four endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT-0, I, II and III) (Katzmann et al., 2002; Williams and Urbe, 2007). Ubiquitinated receptors are bound by Hepatocyte growth factor regulated substrate (Hrs) in ESCRT-0, Tumor susceptibility gene 101 (Tsg101) in ESCRT-I and Vacuolar protein sorting 36 (Vps36) in ESCRT-II, and their deubiquitination and internalization are coordinated by ESCRT-III (Williams and Urbe, 2007).

Genetic or pharmacological blocks of endocytosis prevent degradation of the EGFR and other receptors. In Drosophila, hrs mutations block MVB invagination, trapping receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) and other receptors on the outer membrane of the MVB, and sometimes leading to enhanced signaling (Jekely and Rorth, 2003; Lloyd et al., 2002; Rives et al., 2006; Seto and Bellen, 2006). Mutations in the ESCRT complex subunits Tsg101 (ESCRT-I) and Vps25 (ESCRT-II) cause overproliferation due to the accumulation of mitogenic receptors such as Notch and Thickveins (Herz et al., 2006; Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005). In mammalian cells, loss of Hrs or Tsg101 results in increased EGFR signaling (Bache et al., 2006; Razi and Futter, 2006). However, other studies have shown a positive role for endocytosis in receptor signaling (Miaczynska et al., 2004; Seto and Bellen, 2006; Teis and Huber, 2003). Mutations affecting the Drosophila trafficking protein Lethal giant discs dramatically increase Notch signaling only in the presence of Hrs, indicating that signaling is maximized at a specific point in the endocytic process (Childress et al., 2006; Gallagher and Knoblich, 2006; Jaekel and Klein, 2006). Wingless (Wg) signaling is enhanced by internalization into endosomes, where it colocalizes with downstream signaling molecules (Seto and Bellen, 2006). In mammalian cells, the EGFR encounters the scaffolding proteins MEK1 partner (MP1) and p14, which are required for maximal phosphorylation of the downstream component mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), only on endosomes (Pullikuth et al., 2005; Teis et al., 2006).

Here we describe the characterization of the novel Drosophila gene myopic (mop). Loss of mop affects EGFR-dependent processes in eye and embryonic development, and reduces MAPK phosphorylation by activated EGFR in cultured cells. Mop acts upstream of Ras activation to promote the function of activated, internalized EGFR. Mop is homologous to human HD-PTP (Toyooka et al., 2000), which contains a Bro1 domain able to bind the ESCRT-III complex component Snf7 (Ichioka et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2005) and a tyrosine phosphatase domain. Mop is present on intracellular vesicles, and cells lacking mop have enlarged endosomes and reduced cleavage of the EGFR cytoplasmic domain. We propose that Mop potentiates EGFR signaling by enhancing its progression through endocytosis. Consistent with this hypothesis, we find that components of the ESCRT-0 and ESCRT-I complexes are also required for EGFR signaling in Drosophila cells.

Materials and Methods

Fly stocks and genetics

Four alleles of mop were isolated in a mosaic screen for genes required for photoreceptor differentiation (Janody et al., 2004). mop was mapped by meiotic recombination with P(w+) elements (Zhai et al., 2003) to a 30 kb region containing 5 predicted genes: CG9384, CG17173, CG9311, CG5295 and CG13472. The coding regions of these genes were amplified by PCR from homozygous mop mutant embryos. Changes were found only in CG9311, which had stop codons at Q351 in mopT612, Q538 in mopT862 and Q1698 in mopT482. Other strains used were UAS-EGFRλtop (Queenan et al., 1997), cblF165 (Pai et al., 2000), hrsD28 (Lloyd et al., 2002), styΔ5, UAS-rasV12, aosΔ7, aos-lacZW11, dpp-lacZ{BS3.0}, Dll-lacZ01092, ap-GAL4, actin>CD2>GAL4, and Df(2L)Exel6277 (Flybase). Stocks used to make clones were: (1) eyFLP1; FRT80, Ubi-GFP, (2) eyFLP1; FRT80, M(3)67C, Ubi-GFP/TM6B, (3) hsFLP122; FRT80, Ubi-GFP, (4) hsFLP122; FRT80, M(3)67C, Ubi-GFP/TM6B, (5) FRT2A, mopT612/TM6B, (6) hsFLP122; FRT2A, P(ovoD)/TM3, and (7) eyFLP1, UAS-GFP; tub-GAL4; FRT80, tub-GAL80. mop mutant clones in hrs mutant eye discs were generated by crossing FRT80, mopT612; hrsD28, eyFLP/SM6-TM6B to FRT80, Ubi-GFP; Df(2L)Exel6277/SM6-TM6B. UAS-mop was made by cloning a BglII fragment from the full-length cDNA SD03094 (Drosophila Genomics Resource Center) into pUAST. UAS-mopCS was made by PCR, using primers that changed C1728 to S and also introduced a KpnI site by changing S1732 to T. UAS-FlagMop was generated by PCR amplification of an N-terminal EcoR1/Xho1 fragment using primers that introduced an N-terminal Flag tag.

Immunohistochemistry and Western blotting

Staining of eye and wing discs with antibodies or X-gal was performed as described (Lee et al., 2001). Antibodies used were rat anti-Elav (1:100), mouse anti-Cyclin B (1:50), mouse anti-Cut (1:1), mouse anti-Wg (1:5) (Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), guinea pig anti-Sens (1:1000)(Nolo et al., 2000), rabbit anti-Ato (1:5000)(Jarman et al., 1995) rabbit anti-CM1 (1:500; BD Pharmingen), rabbit anti-β-galactosidase (1:5000; Cappel), rabbit anti-GFP (1:1000; Molecular Probes), mouse anti-dpERK (1:250; Sigma) rat anti-Ci (1:1)(Motzny and Holmgren, 1995), guinea pig anti-Hrs (1:200) (Lloyd et al., 2002), guinea pig anti-Dor (1:200)(Sevrioukov et al., 1999), guinea pig anti-Spinster (1:250)(Sweeney and Davis, 2002), rabbit anti-Rab11 (1:1000)(Satoh et al., 2005), mouse anti-Flag (1:500; Sigma), mouse anti-Mop (1:100; Abcam) and rabbit anti-EGFR (1:500)(Rodrigues et al., 2005). Embryos were stained with rabbit anti-Slam (1:1000) after heat fixation as described (Stein et al., 2002). TOTO-3 was used at 1:3000 for 15 min, on embryos treated with 100μg/ml RNase for 30 min before the secondary antibody. In situ hybridization was performed as described (Roignant et al., 2006) using sense and antisense probes transcribed from the mop cDNA SD03094 or an antisense probe transcribed from a 1.5 kb PCR product encompassing the hkb coding region. UAS-GFPRab5, UAS-GFPRab7, UAS-GFPRab11, and UAS-lgp120-GFP were a gift from Henry Chang (Chang et al., 2004). S2R+ cells were fixed in PBS containing 4% formaldehyde and stained as described (Miura et al., 2006). Images were captured on a Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope. Western blots were performed as described (Miura et al., 2006). Antibodies used were mouse anti-dpERK (1:2500; Sigma), mouse anti-ERK (1:20000; Sigma), mouse anti-Tubulin (1:1000; Covance), rabbit anti-EGFR (1:10000) (Lesokhin et al., 1999), mouse anti-Mop (1:1000; Abcam) and mouse anti-GFP (1:300; Santa Cruz).

Cell culture and RNAi

S2 and S2R+ cells were maintained in Schneider’s medium supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum; EGFR-expressing S2 (D2F) cells (Schweitzer et al., 1995) were additionally supplemented with 150 μg/ml G418 and sSpiCS-expressing cells (Miura et al., 2006) with 150μg/mL hygromycin. Cells were transfected using Effectene (Qiagen). UAS plasmids were cotransfected with actin-GAL4. UAS-HACblL was cloned by PCR amplification of a cDNA representing the longer Cbl isoform. Double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) were generated using the MEGAscript T7 and T3 kit (Ambion) as described (Roignant et al., 2006) and 15 μg dsRNA were used to treat 106 cells/well. S2R+ cells were transfected with actin-GAL4, UAS-GFP, and UAS-EGFRλtop (Queenan et al., 1997) 1 day after dsRNA incubation. Cells were harvested after 2 days and lysed in ice-cold 50mM Tris-HCl pH 7.5, 150mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-110, protease inhibitors (Roche). D2F cells treated with dsRNA for 4 days were serum-starved overnight in dsRNA. EGFR expression was induced for 3 hr with 60 μM Cu2SO4, and the cells were transferred to sSpiCS conditioned medium prepared by growing cells stably expressing sSpiCS in serum-free medium containing 500 μM CuSO4 for 4 days. Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Schweitzer et al., 1995). Total RNA was extracted from D2F cells using Trizol (Invitrogen). RT-PCR was performed from 1 μg of total RNA using the Invitrogen SuperScript First-Strand kit. Primer sequences are available on request.

Internalization of Alexa-labeled Spi

Cells stably expressing pMT-sSpiCSHis were grown to 5 × 106 cells/ml in serum-free medium and induced for 4 days with 0.5 mM Cu2SO4. Medium was collected and diafiltered against 150 mM NaCl/25 mM HEPES pH 8. sSpiCSHis was purified using the Ni-NTA Fast Start Kit (Qiagen), concentrated using Centricon columns (Millipore), diafiltered again, and labeled using an Alexa Fluor 546 Protein labeling Kit (Molecular Probes). D2F cells were incubated with dsRNA for 4 days, serum-starved overnight with dsRNA, and EGFR expression was induced for 16 hr with 500μM Cu2SO4. Cells were incubated with 100nM Alexa-labeled sSpiCS in PBS/1% BSA on ice for 30 min, washed three times with PBS/1%BSA, incubated in serum-free medium with 75 nM Lysotracker (Molecular Probes) at room temperature and imaged by confocal microscopy. Vesicles containing Spi were scored as negative, weakly or strongly stained with Lysotracker by two independent observers.

Results

mop is required for EGFR signaling during eye development

Photoreceptor differentiation in the Drosophila eye disc is driven by the secreted protein Hedgehog (Hh) (Heberlein and Moses, 1995). Hh induces the transcription factor Atonal (Ato), which promotes the differentiation of R8 photoreceptors posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (Dominguez, 1999; Jarman et al., 1995). R8 then secretes the EGFR ligand Spitz (Spi), which recruits photoreceptors R1-7 into each cluster (Freeman, 1997). In a screen for genes required for photoreceptor differentiation (Janody et al., 2004), we isolated four ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)-induced alleles of a previously undescribed gene that we have called myopic (mop). In mop mutant clones, fewer photoreceptors, visualized by staining with the neuronal nuclear marker Elav, were present (Fig 1A, A′). However, R8 differentiation appeared almost normal as judged by expression of the markers Ato and Senseless (Sens) (Frankfort et al., 2001) (Fig. 1B–B″, C–C″), suggesting that the primary defect is in recruitment of R1-7 through EGFR signaling.

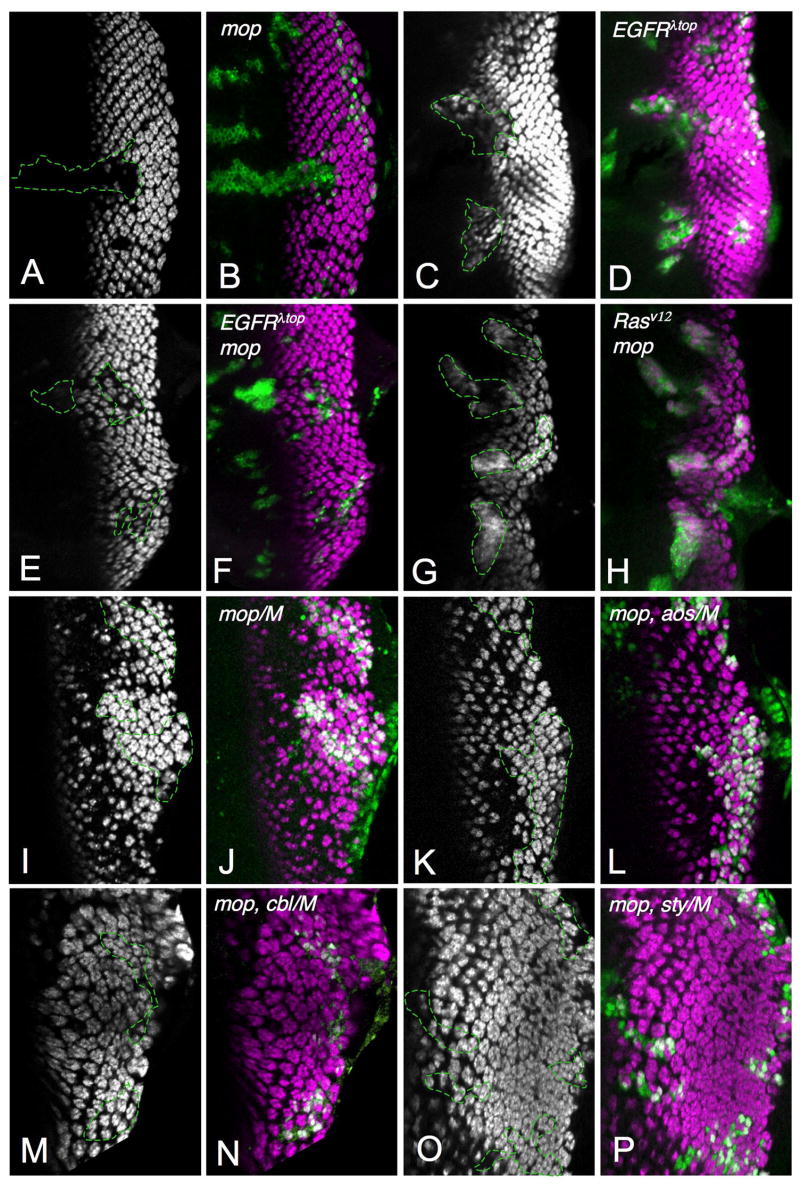

Figure 1. mop is required for EGFR signaling.

(A–F′) show third instar eye discs. (A, A′) mopT612 mutant clones marked by the absence of GFP (green in A′). Photoreceptors are stained with anti-Elav (A, magenta in A′). (B–B″, C–C″) show eye discs with large mopT612 mutant clones generated in a Minute background and marked by the absence of GFP (B′, C′, green in B″, C″). R8 photoreceptors are stained with anti-Ato (B, magenta in B″) or anti-Sens (C, magenta in C″). mop has little effect on R8 differentiation. (D–F′) show mopT612 mutant clones marked by the absence of GFP (green in D′, E′, F′). Activated Caspase 3 staining (D, magenta in D′) marks apoptotic cells and Cyclin B staining (E, magenta in E′) marks cells in G2 or M phase. Posterior mop mutant clones contain reduced numbers of photoreceptors and show increased cell death and cell cycle re-entry. Phospho-MAPK staining (F, magenta in F′) is reduced in mop mutant clones in the morphogenetic furrow (arrow) and posteriorly (arrowhead). (G, H) show embryos stained with anti-β-galactosidase reflecting aos-lacZ expression. (G) wildtype; (H) maternal/zygotic mop mutant. aos expression is strongly reduced in the absence of mop. (I) an adult wing containing mopT612 mutant clones shows loss of wing vein material (arrow). (J) shows a third instar wing disc with mopT612 clones made in a Minute background and marked by the absence of GFP (green), stained with anti-β-galactosidase reflecting aos-lacZ expression (magenta).

EGFR signaling is also required in the eye disc for cell survival and cell cycle arrest. Mutations in EGFR pathway components increase cell death posterior to the morphogenetic furrow (Baonza et al., 2002; Roignant et al., 2006; Yang and Baker, 2003). We observed activated Caspase 3 staining, indicative of apoptotic cells, in posterior mop mutant clones (Fig. 1D, D′). Loss of EGFR signaling also prevents the R2–R5 precursors from arresting in G1 phase (Roignant et al., 2006; Yang and Baker, 2003). Expression of the G2 phase marker Cyclin B was increased in mop mutant clones, indicating that more cells re-entered the cell cycle (Fig. 1E, E′). Finally, we examined EGFR signaling directly by looking at phosphorylation of the downstream component MAPK using a phospho-specific antibody (Gabay et al., 1997b). Phospho-MAPK staining was reduced in mop mutant clones (Fig. 1F, F′), confirming a role for mop in EGFR signaling.

EGFR signaling is also active at the embryonic midline and in the wing vein primordia, where it turns on expression of the target gene argos (aos) (Gabay et al., 1997a; Golembo et al., 1996; Guichard et al., 1999). In embryos lacking maternal and zygotic mop, midline aos expression was strongly reduced (Fig. 1G, H). Adult wings that contained mop mutant clones had missing wing veins (Fig. 1I), although aos was still detectable in mop clones in the wing disc (Fig. 1J). We also examined signaling by another RTK, Torso. Torso specifies the termini of the embryo by inducing target genes that include huckebein (hkb) (Ghiglione et al., 1999). hkb was expressed normally in embryos derived from mop mutant germline clones (Fig. S1A, B); mop is thus not essential for Torso signaling and may be specific to the EGFR pathway.

mop is not required in the absence of Cbl

To determine where Mop functions within the EGFR pathway, we attempted to rescue mop mutant clones by activating other components of the pathway. Although expression of an activated form of the EGFR (Queenan et al., 1997) in wildtype cells caused ectopic photoreceptor differentiation, its expression in mop mutant cells did not rescue the loss of photoreceptors (Fig. 2C–F). However, an activated form of Ras (Karim and Rubin, 1998) could induce excessive photoreceptor differentiation when expressed in mop mutant cells (Fig. 2G–H). These results place Mop function downstream of EGFR activation but upstream of Ras. In agreement with an intracellular action of Mop, removal of Aos, which inhibits pathway activation extracellularly by binding to Spi (Klein et al., 2004), did not significantly restore photoreceptor differentiation in the absence of mop (Fig. 2I–L).

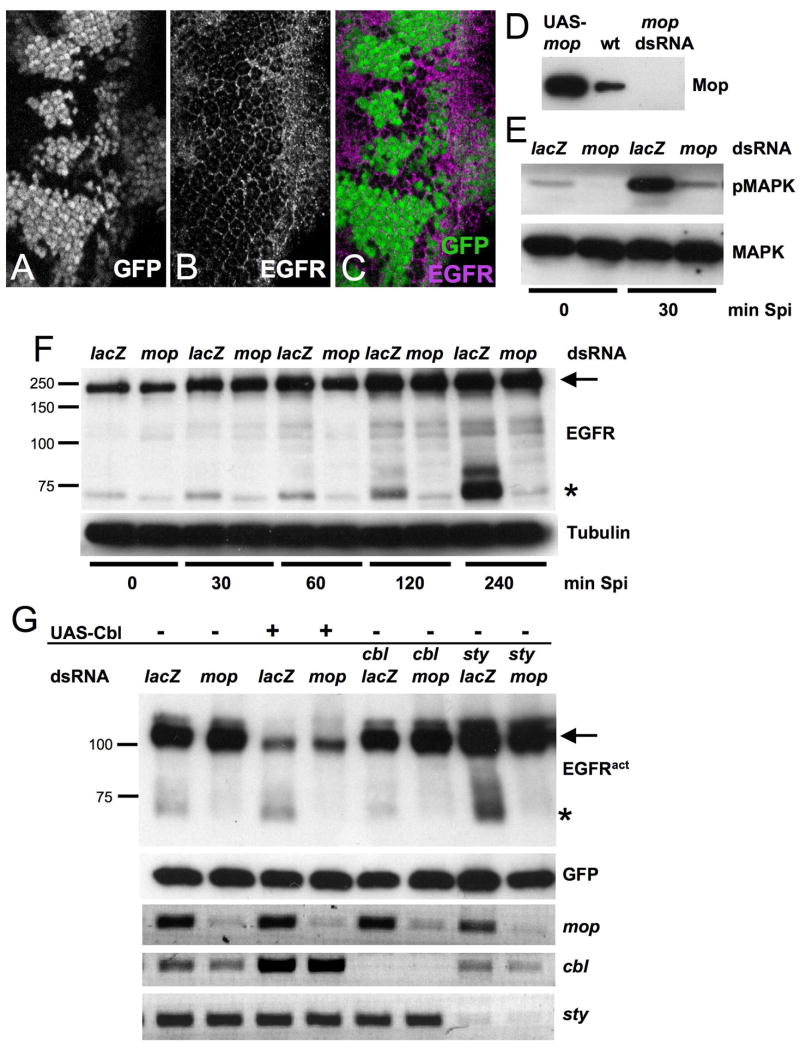

Figure 2. mop acts on internalized EGFR.

All panels show third instar eye discs. Photoreceptors are stained with anti-Elav (A, C, E, G, I, K, M, O; magenta in B, D, F, H, J, L, N, P). (A, B) mopT482 mutant clones are positively marked by GFP expression (green in B, outlined in A). (C, D) Clones expressing EGFRλtop are positively marked by GFP expression (green in D, outlined in C). (E–F) mopT612 mutant clones expressing EGFRλtop are positively marked by GFP expression (green in F, outlined in E). (G, H) mopT612 mutant clones expressing Rasv12 are positively marked by GFP expression (green in H, outlined in G). (I–P) Large clones generated in a Minute background are marked by the absence of GFP (green in J, L, N, P, outlined in I, K, M, O). (I, J) mopT612; (K, L) mopT612 aosΔ7; (M, N) mopT612 cblF165; (O, P) mopT612 styΔ5. Although EGFRλtop induces photoreceptor differentiation in a wildtype background, it does not rescue mop mutant clones; removing aos also fails to rescue. Photoreceptor differentiation can be restored to mop mutant clones by expressing Rasv12 or removing cbl or sty.

To determine the position of Mop more precisely, we used a negative regulator of the pathway that also acts between the EGFR and Ras. Cbl is an E3 ubiquitin ligase required for internalization and degradation of the EGFR (Pai et al., 2000; Swaminathan and Tsygankov, 2006). Although loss of cbl only mildly increases photoreceptor differentiation (Wang et al., 2008), the photoreceptor loss observed in mop mutant clones was restored in clones doubly mutant for mop and cbl (Fig. 2M, N). This result indicates that the absence of photoreceptors in mop mutant clones is specifically due to reduced signaling by the EGFR or other RTKs regulated by Cbl, and that mop is only required for the activity of EGFR molecules that have been internalized through Cbl activity.

mop encodes a novel endosomal protein

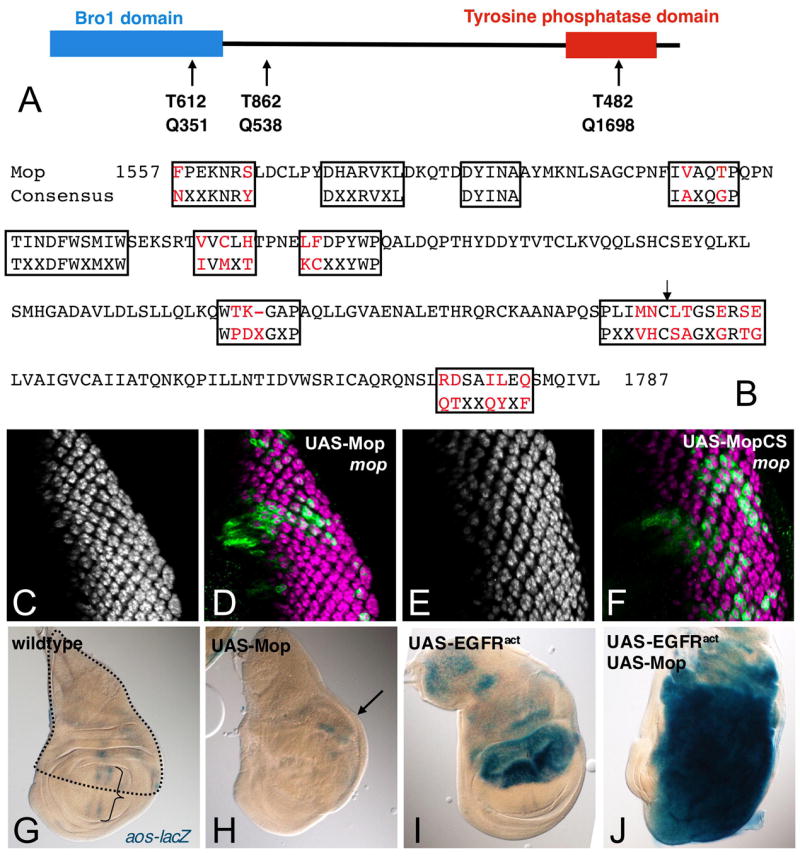

We used recombination with molecularly characterized P(w+) insertions (Zhai et al., 2003) to map mop to a region containing five predicted genes. Genomic DNA isolated from three of our mop alleles contained nonsense mutations in one of these genes, CG9311, that were not present in the isogenic strain used for the screen (Fig. 3A). To confirm that mop corresponded to CG9311, we showed that expression of a CG9311 transgene in mop mutant clones was sufficient to rescue photoreceptor differentiation (Fig. 3C, D). In situ hybridization showed that mop transcripts were present ubiquitously in early embryos and imaginal discs, and at high levels in the nervous system and gut at later embryonic stages (Fig. S2A–F).

Figure 3. Structure and expression of the Mop protein.

(A) Mop contains regions of homology to Bro1 and to receptor tyrosine phosphatases. The positions of stop codons introduced by three mop mutant alleles are indicated. (B) Comparison of the Mop tyrosine phosphatase domain with the consensus sequences for the 10 functional motifs defined for tyrosine phosphatases (boxed). Amino acids that differ from the consensus sequence are colored in red. An arrow indicates the predicted active site cysteine. (C–F) Third instar eye imaginal discs with clones positively marked by GFP expression (green in D, F) stained with anti-Elav (C, E, magenta in D, F). (C, D) mopT482 clones expressing a wildtype UAS-mop transgene; (E, F) mopT482 clones expressing a phosphatase-dead transgene (UAS-mopCS). Both transgenes fully rescue photoreceptor differentiation. (G–J) show third instar wing imaginal discs expressing aos-lacZ and ap-GAL4 and stained overnight with X-gal. ap-GAL4 drives expression in the dorsal compartment (outlined in G). (G) wildtype; aos is weakly expressed in the wing vein primordia (bracket). (H) UAS-FLAGmop; (I) UAS-EGFRλtop; (J) UAS-FLAGmop and UAS-EGFRλtop. Mop overexpression gave very weak ectopic aos expression (arrow, H), but strongly enhanced the effect of activated EGFR.

To determine whether Mop could activate the EGFR pathway, we expressed UAS-mop in the dorsal compartment of the wing disc using apterous (ap)-GAL4 and examined the expression of the EGFR target gene aos. Expression of Mop only very weakly activated aos expression (Fig. 3H), while a constitutively active form of the EGFR induced strong aos expression (Fig. 3I). Coexpression of Mop potentiated the effect of activated EGFR, increasing the level of aos expression and inducing overgrowth of the dorsal compartment of the disc (Fig. 3J). Similarly, coexpression of Mop enhanced the ability of activated EGFR to induce ectopic photoreceptor differentiation in the eye disc (data not shown). We conclude that Mop does not itself activate the EGFR, but the maximal activity of the activated receptor depends on the level of Mop expression.

mop encodes a protein of 1833 amino acids with a Bro1 domain (Kim et al., 2005) at its N-terminus and a region of homology to tyrosine phosphatases at its C-terminus (Figure 3A). However, some amino acids thought to be critical for phosphatase activity (Andersen et al., 2001) are not conserved in the Mop tyrosine phosphatase domain (Fig. 3B). We tested whether phosphatase activity was required for Mop function by mutating the predicted active site cysteine to a serine (Fig. 3B). Expression of this transgene (MopCS) rescued photoreceptor differentiation in mop mutant clones as effectively as the wildtype Mop transgene (Fig. 3E, F), suggesting that tyrosine phosphatase activity may not be essential for Mop function in the eye disc.

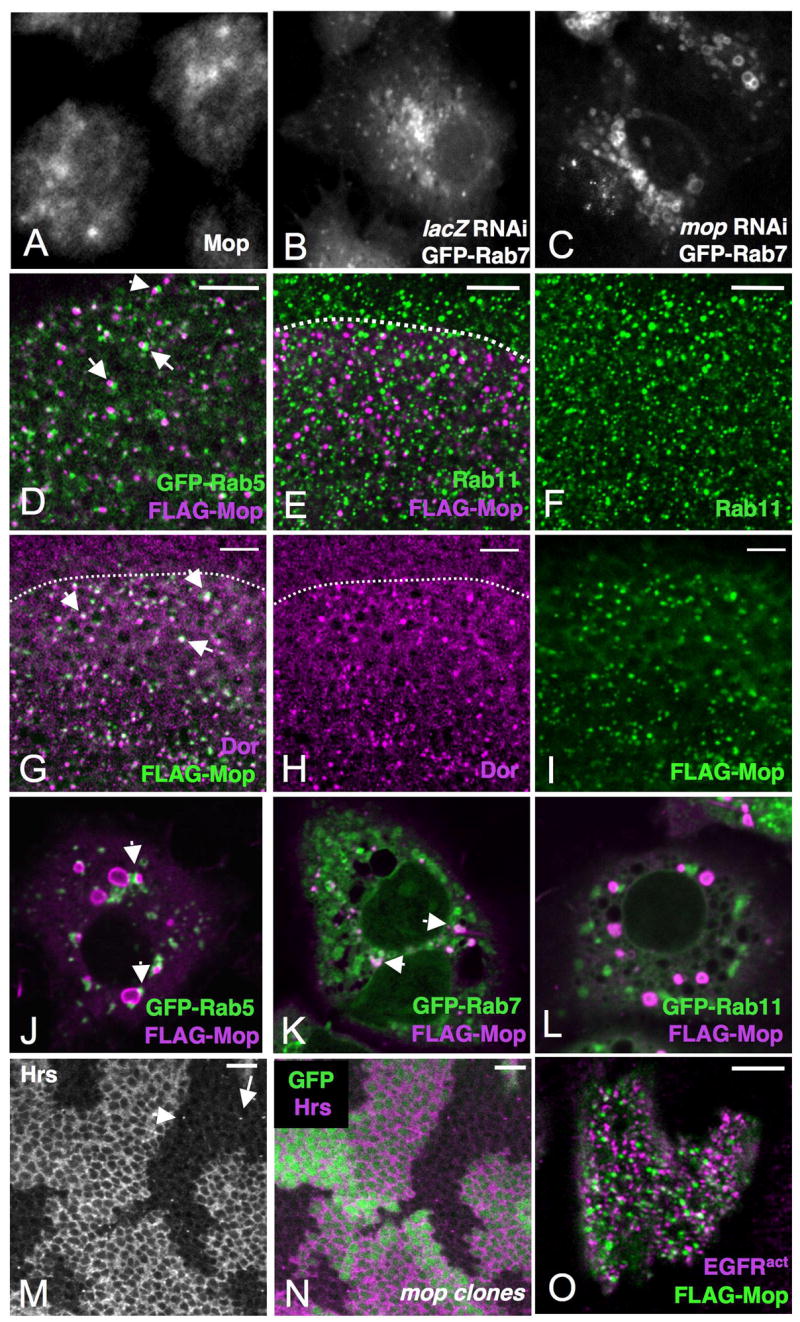

The Bro1 domain of yeast Bro1 is sufficient to mediate endosomal localization (Kim et al., 2005), and Bro1 domain proteins are important for endocytic trafficking (Odorizzi, 2006). We therefore examined the subcellular localization of Mop. Using an antibody generated by the UT Southwestern genomic immunization project, which specifically recognized Mop on Western blots (see Fig. 5D), we observed punctate intracellular localization of the endogenous protein in Drosophila S2R+ cells (Fig. 4A). Since endogenous Mop levels were too low to obtain high-resolution images, we generated a transgene expressing an N-terminally Flag-tagged Mop protein, which could rescue photoreceptor differentiation in mop mutant clones (Fig. S2G, H). FLAG-Mop was located at the membrane of intracellular vesicles in imaginal discs and S2R+ cells (Fig. 4D–L). These vesicles were often adjacent to vesicles expressing the early endosomal marker GFP-Rab5 (Fig. 4D, J). We observed some colocalization of Mop with the late endosomal markers GFP-Rab7, Deep orange (Dor) (Sevrioukov et al., 1999; Sriram et al., 2003) and Hrs, though these markers appeared more punctate in Mop-overexpressing cells (Fig. 4G–I, K and data not shown). However, we saw no colocalization of Mop with the recycling endosome marker Rab11 or the lysosomal markers GFP-lgp120 or Spinster (Chang et al., 2004; Satoh et al., 2005; Sweeney and Davis, 2002) (Fig. 4E, F, L and data not shown).

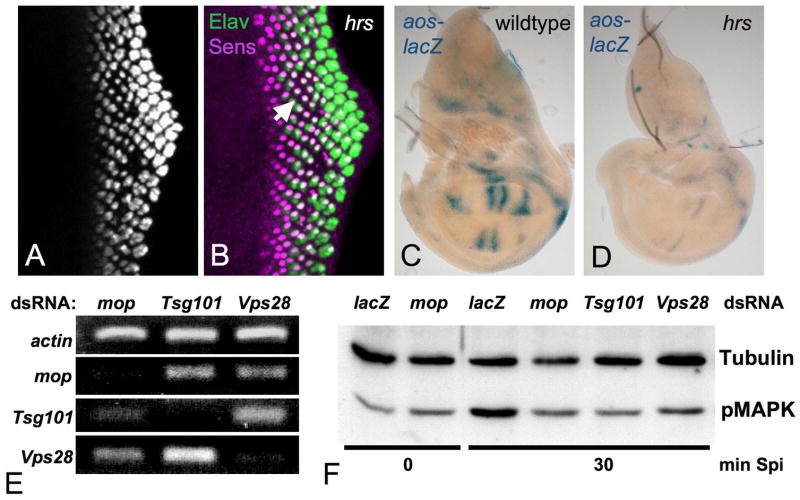

Figure 5. Mop is required for MAPK phosphorylation and EGFR cleavage.

(A–C) show an eye disc with mopT612 mutant clones marked by the absence of GFP (A, green in C) and stained with anti-EGFR (B, magenta in C). EGFR levels are slightly increased in mop mutant clones. (D) Western blot with Mop antibody of extracts from S2 cells transfected with actin-GAL4 and UAS-mop, untreated (wt) or treated with mop dsRNA. mop is expressed in S2 cells and its levels can be significantly reduced by RNAi. (E) D2F cells were treated with lacZ or mop dsRNA and incubated with sSpi conditioned media for 0 or 30 min. Protein lysates were blotted with antibodies to diphospho-MAPK and total MAPK. mop dsRNA treatment resulted in a decrease in MAPK phosphorylation. (F) shows a Western blot with anti-EGFR of lysates from D2F cells treated with lacZ or mop dsRNA and incubated with Spi conditioned media for the indicated times. Cells treated with mop dsRNA failed to accumulate a faster migrating band recognized by the EGFR antibody (asterisk). The position of full-length EGFR is indicated by an arrow. (G) S2R+ cells were treated with lacZ, mop, cbl and/or sty dsRNA as indicated and transfected with actin-GAL4, UAS-GFP and UAS-EGFRλtop, and UAS-cblL in the indicated lanes. Protein lysates were blotted with antibodies to EGFR and GFP (transfection control). A smaller band recognized by the EGFR antibody that is the same size as the smaller band in (F) is indicated by an asterisk; an arrow indicates full-length EGFRλtop. The proportion of the smaller band is increased by Cbl cotransfection or sty RNAi and decreased by mop RNAi. The lower three panels show RT-PCR quantification of mop, cbl and sty mRNA, demonstrating the efficiency of the RNAi treatment.

Figure 4. Mop is an endosomal protein.

(A) shows S2R+ cells stained for endogenous Mop. (B, C) show GFP-Rab7 fluorescence in live S2R+ cells treated with dsRNA targeting lacZ (B) or mop (C). Mop depletion causes enlargement of Rab7-containing endosomes. (D–I) show wing discs expressing UAS-FLAGMop with ap-GAL4 and stained for FLAG (magenta in D, E; green in G, I), coexpressed Rab5-GFP (green in D), Rab11 (green in E, F), or Dor (magenta in G, H). (J–L) show S2R+ cells expressing UAS-FLAGMop and UAS-GFPRab5 (J), UAS-GFPRab7 (K) or UAS-GFPRab11 (L) with actin-GAL4. FLAG staining is shown in magenta and GFP in green. Mop is present on vesicles that are adjacent to Rab5-containing vesicles (arrowheads in D, J), show partial colocalization with Dor and Rab7 (arrowheads in G, K), and do not colocalize with Rab11. (M, N) show wing discs with mopT612 clones marked by the absence of GFP (green in N), stained with anti-Hrs (M, magenta in N). Hrs shows reduced levels and punctate localization (arrows, M) in mop mutant clones. (O) shows an eye disc with a clone of cells expressing UAS-FLAGMop and UAS-EGFRλtop, stained with anti-FLAG (green) and anti-EGFR (magenta). Most activated EGFR is present in vesicles that do not contain Mop. Scale bars are 10μm.

Removal of proteins required for progression through endocytosis often results in the enlargement of specific endocytic compartments (Raymond et al., 1992). We found that S2R+ cells in which mop was depleted by RNA interference (RNAi) showed an enlargement of endosomes labeled by GFP-Rab7 (Fig. 4B, C). Loss of mop also had a striking effect on Hrs distribution in vivo; Hrs levels appeared strongly reduced in mop mutant clones, and the remaining Hrs protein was punctate rather than diffusely localized (Fig. 4M, N; Fig. S3A, B). These observations suggest that Mop has an essential role in the endocytic pathway. While loss of cbl can rescue the EGFR signaling defects in mop mutant cells (Fig. 2M, N), it does not rescue the endocytic defects that result in Hrs mislocalization (Fig. S3A–F), supporting the model that rescue is observed because the EGFR remains on the cell surface.

In the early Drosophila embryo, cells are formed by invagination of membranes between the nuclei; this process requires apical-basal transfer of membrane through endocytosis and recycling (Lecuit, 2004). Injection of embryos with dominant-negative Rab5 or Rab11 causes defective membrane invagination and loss of nuclei from the embryo cortex (Pelissier et al., 2003). Embryos derived from mop mutant germline clones showed similar cellularization defects. Membrane invagination was irregular, and some nuclei lost their association with the cortex (Fig. S1C–F), consistent with a role for Mop in endocytosis.

Mop is required for EGFR processing

The presence of Mop on intracellular vesicles and its effect on endosome size suggested that Mop might enhance EGFR signaling by controlling its endocytic trafficking. However, Mop does not prevent EGFR protein degradation, since mop mutant clones in the eye disc showed a slight increase in EGFR levels (Fig. 5A–C). To look for other effects on the EGFR, we used cultured S2 cells, in which Mop levels could be strongly reduced by RNAi (Fig. 5D, G). We first tested whether mop was required for EGFR signaling in these cells, using MAPK phosphorylation to monitor EGFR activity (Gabay et al., 1997b). Treatment of an S2 cell line that stably expresses the EGFR (D2F; (Schweitzer et al., 1995)) with media conditioned by cells expressing Spi (Miura et al., 2006) induced significant MAPK phosphorylation after 30 minutes. This phosphorylation was strongly reduced in cells treated with mop RNAi (Fig. 5E), confirming a requirement for Mop in EGFR signal transduction. In D2F cells stimulated with fluorescently labeled purified Spi, knocking down mop by RNAi did not prevent Spi uptake into intracellular vesicles (Fig. S4); thus Mop does not affect the cell surface expression of the EGFR or its ability to bind and internalize Spi. However, mop RNAi treatment did alter the colocalization of fluorescent Spi with Lysotracker, a dye that detects lysosomes by their low pH. The proportion of Spi-containing vesicles with strong Lysotracker staining 3–4 hours after Spi treatment was reduced in mop-depleted cells (Fig. S4A–G). mop depletion increased the proportion of Spi-positive vesicles showing weak Lysotracker accumulation (Fig. S4G), suggesting that Spi is retained in endosomes that have begun the process of acidification. These data are consistent with a reduction in EGFR traffic to the lysosome in the absence of Mop.

When we examined the EGFR by Western blotting in D2F cells following Spi treatment, we observed the progressive accumulation of a faster migrating band recognized by an antibody generated against the extreme C-terminus of the EGFR (Lesokhin et al., 1999)(Fig. 5F). This band is the appropriate size (60 kD) to be the cytoplasmic domain of the receptor, suggesting that it is produced by juxtamembrane cleavage. The same size band was observed in S2R+ cells transfected with an activated form of the EGFR (λtop)(Fig. 5G), although this form has a smaller, unrelated extracellular domain derived from the lambda repressor (Queenan et al., 1997). The relative abundance of the smaller band was increased by cotransfection with a Cbl expression construct and reduced by Cbl depletion (Fig. 5G), consistent with cleavage occurring in the endocytic pathway. The appearance of this smaller band was prevented by mop depletion both in D2F cells treated with Spi and in S2R+ cells transfected with EGFRλtop (Fig. 5F, G), suggesting that mop is required for the EGFR to reach the compartment in which it is cleaved.

Progression through endocytosis enhances EGFR signaling

Receptor signaling terminates when invagination of the MVB outer membrane traps the cytoplasmic domains of receptors inside the inner vesicles. Hrs acts at the first step in this process, and hrs mutants have been reported to result in enhanced EGFR signaling in the embryo and ovary (Jekely and Rorth, 2003; Jekely et al., 2005; Lloyd et al., 2002). We therefore examined the role of Hrs in EGFR signaling in imaginal discs. Surprisingly, hrs mutant eye discs showed a loss of photoreceptors other than R8 (Fig. 6A, B), and expression of the EGFR target gene aos was strongly reduced in hrs mutant wing discs (Fig. 6C, D), indicating that Hrs is required for EGFR signaling. Loss of hrs did not rescue either photoreceptor differentiation or cell survival in mop mutant clones (Fig. S3G, H), consistent with a similar function of both proteins in EGFR signaling.

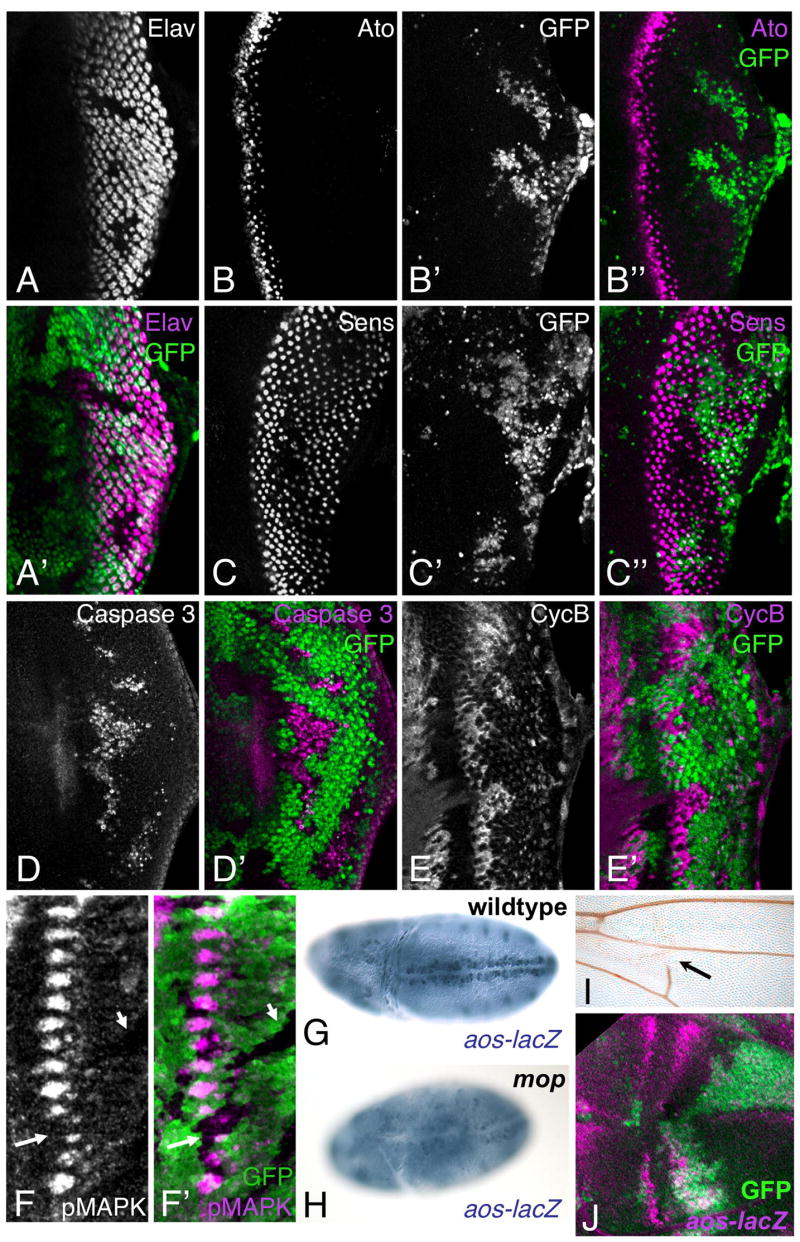

Figure 6. Progression through endocytosis promotes EGFR signaling.

(A, B) show an hrsD28/Df(2L)Exel6277 eye disc stained with anti-Elav (A, green in B) and anti-Sens (magenta in B). The arrow in (B) indicates a group of ommatidia containing only R8 photoreceptors. (C, D) show aos-lacZ expression in wildtype (C) and hrsD28/Df(2L)Exel6277 (D) wing discs stained in parallel with X-gal. R1-7 differentiation and aos expression are reduced in hrs mutants. (E) shows semi-quantitative RT-PCR for actin, mop, Tsg101 and Vps28 mRNA in D2F cells treated with mop, Tsg101 or Vps28 dsRNA, demonstrating efficient knockdown in each case. (F) shows a Western blot with antibodies to Tubulin and diphospho-MAPK of lysates from D2F cells treated with lacZ, mop, Tsg101 or Vps28 dsRNA and incubated with Spi for 0 or 30 min. Depletion of either Mop or the ESCRT-I complex components reduced MAPK phosphorylation.

In mammalian cells, EGFR signaling is terminated subsequent to the activity of the ESCRT-I component Tsg101, but before the activity of the ESCRT-III component Vps24 (Bache et al., 2006). Since loss of ESCRT-I and -II complex components activates Notch signaling in Drosophila, inhibiting photoreceptor differentiation (Herz et al., 2006; Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005), we could not easily evaluate their effects on EGFR signaling in vivo. Instead, we used RNAi to deplete the ESCRT-I complex components Tsg101 and Vps28 from D2F cells treated with Spi. Efficient knockdown was confirmed by RT-PCR and by the enlargement of Hrs-containing endosomes (Fig. 6E; Fig. S3I–L). Surprisingly, we found that MAPK phosphorylation was reduced in both cases (Fig. 6F). MAPK phosphorylation was similarly reduced by Cbl depletion (Fig. S3M). This suggests that efficient EGFR signaling in Drosophila cells requires progression through the endocytic pathway. This model is consistent with the recent finding that human Sprouty2 antagonizes EGFR signaling by preventing its progression from early to late endosomes (Kim et al., 2007). In S2R+ cells, depleting sprouty (sty) by RNAi enhanced the cleavage of EGFRλtop (Fig. 5G), supporting a function for Drosophila Sty in blocking EGFR progression through endocytosis. Removal of sty restored photoreceptor differentiation to mop mutant cells (Fig. 2O, P) and partially rescued MAPK phosphorylation in Mop-depleted cells (Fig. S3M), suggesting that Mop may counteract Sty activity.

Mop might affect EGFR trafficking either through a direct interaction, or through an indirect effect on the endocytic pathway. We were unable to coimmunoprecipitate Mop with either wildtype or activated EGFR from S2 cells (data not shown), and activated EGFR expressed in vivo showed a vesicular distribution distinct from the distribution of coexpressed Mop (Fig. 4O), suggesting an indirect effect. Nevertheless, Mop does not act indiscriminately on all endocytosed receptors. The Hh target gene decapentaplegic (dpp) (Heberlein and Moses, 1995) was expressed normally in mop mutant clones in the eye disc (Fig. S5C), and Ato expression resolved into single R8 cells, indicating normal Notch signaling (Fig. 1B–B″). In the wing disc, mop mutant clones likewise showed normal expression of Notch and Hh target genes (Fig. S5A, B). Some mop mutant clones in the wing disc showed reduced expression of the Wg target gene sens (Parker et al., 2002)(Fig. S5G–H) and a corresponding loss of the adult wing margin bristles specified by Sens (Fig. S5I), although the low-threshold target gene Distal-less (Dll) (Zecca et al., 1996) was not significantly affected (Fig. S5J, K). In these clones, Wg protein accumulated in punctate structures that often colocalized with Hrs (Fig. S5D–F), suggesting that Wg and its Frizzled receptors also require Mop activity for normal endocytic progression.

Discussion

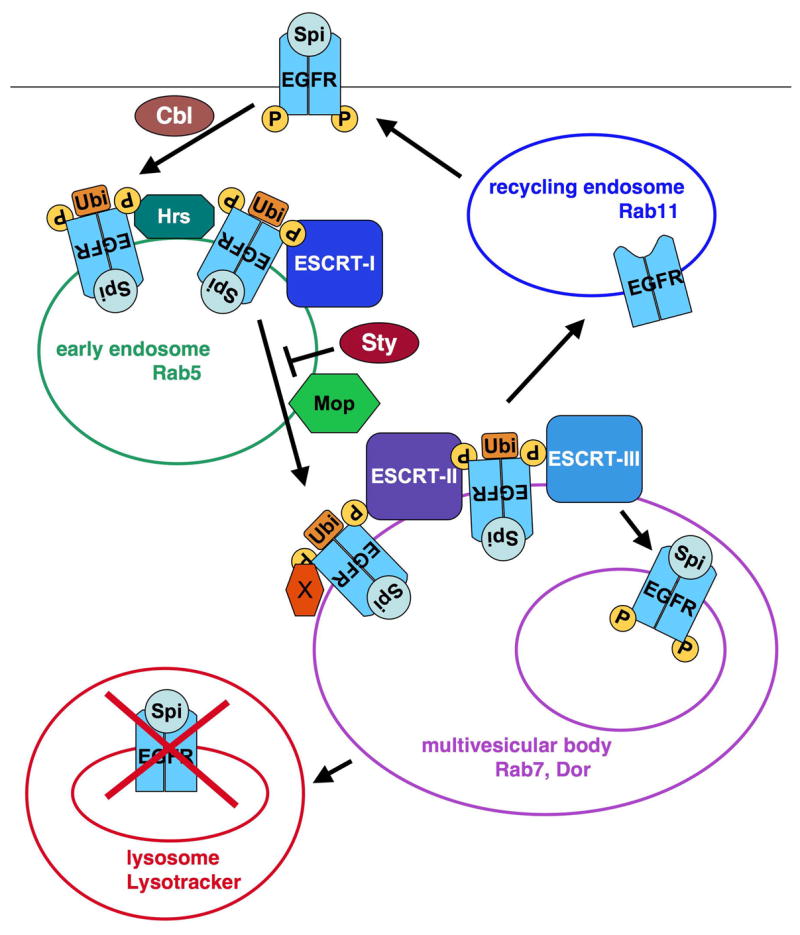

We have shown that the Bro1-domain protein Mop is necessary for EGFR signaling in vivo and in cultured cells. Mop is located on endosomes and affects endosome size, promotes cleavage of the EGFR and lysosomal entry of its ligand, and is not required in the absence of the Cbl or Sty proteins, which regulate endocytic trafficking of the EGFR. These data suggest that Mop enhances EGFR signaling by facilitating its progression through the endocytic pathway (Fig. 7). Consistent with this model, Hrs and ESCRT-I subunits also have a positive effect on EGFR signaling.

Figure 7. Model for the effect of Mop on EGFR endocytosis.

Upon activation of the EGFR, ubiquitination by Cbl induces EGFR internalization through clathrin-coated vesicles. These vesicles fuse with early endosomes and the EGFR is passed from the Hrs complex to the ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II and ESCRT-III complexes as the endosomes are transformed into multivesicular bodies (MVBs). ESCRT-III promotes EGFR deubiquitination and entry into the internal vesicles of MVBs; fusion of MVBs with lysosomes results in EGFR degradation. Sprouty prevents the EGFR from progressing into late endosomes. We propose that Mop is required for EGFR progression through the endocytic pathway, perhaps through its effect on Hrs. This progression may allow the EGFR to encounter critical downstream components located on late endosomes (X), or to be recycled to the plasma membrane to prolong signaling. Cleavage of the receptor must occur at a stage after the requirement for mop.

Mop homologues regulate endocytic sorting

The Bro1 domain of yeast Bro1 is sufficient for localization to late endosomes through its binding to the ESCRT-III subunit Snf7 (Kim et al., 2005), and this domain is present in many proteins involved in endocytosis. Bro1 itself is required for transmembrane proteins to reach the vacuole for degradation; it promotes protein deubiquitination by recruiting and activating Doa4, a ubiquitin thiolesterase (Luhtala and Odorizzi, 2004; Odorizzi et al., 2003; Richter et al., 2007). Since mutations in the E3 ubiquitin ligase gene cbl can rescue mop mutant clones, recruiting deubiquitinating enzymes might be one of the functions of Mop. The vertebrate Bro1-domain protein Alix/AIP1 inhibits EGFR endocytosis by blocking the ubiquitination of EGFR by Cbl and the binding of Ruk, which recruits endophilins, to the EGFR/Cbl complex (Schmidt et al., 2004). However, CG12876, not Mop, is the Drosophila orthologue of Alix (Tsuda et al., 2006).

A closer vertebrate homologue of Mop, which has both Bro1 and tyrosine phosphatase domains, has been named HD-PTP in humans (Toyooka et al., 2000) and PTP-TD14 in rats (Cao et al., 1998). HD-PTP shares with Alix the ability to bind Snf7 and Tsg101, but does not bind to Ruk (Ichioka et al., 2007). PTP-TD14 was found to suppress cell transformation by Ha-Ras, and required phosphatase activity for this function (Cao et al., 1998). The activity of Mop that we describe here appears distinct in that Mop acts upstream of Ras activation, and we could not demonstrate a requirement for the catalytic cysteine in its predicted phosphatase domain. If Mop does act as a phosphatase, Hrs would be a candidate substrate, since tyrosine phosphorylation of Hrs by internalized receptors promotes its degradation (Stern et al., 2007), and Hrs levels appear reduced in mop mutant clones.

Endocytosis and receptor signaling

Endocytosis has been proposed to play several different roles in receptor signaling. Most commonly, endocytosis followed by receptor degradation terminates signaling. However, endocytosis can also prolong the duration of signaling (Jullien and Gurdon, 2005), or influence its subcellular location (de Souza et al., 2007; Howe and Mobley, 2005). Receptors may also signal through different downstream pathways localized to specialized endosomal compartments (Di Guglielmo et al., 2003; Miaczynska et al., 2004; Teis et al., 2006).

Genetic studies in Drosophila have emphasized the importance of endocytic trafficking for receptor silencing. Mutations in hrs, Vps25 or erupted/Tsg101 result in the accumulation of multiple receptors on the perimeter membrane of the MVB, leading to enhanced signaling (Herz et al., 2006; Jekely and Rorth, 2003; Jekely et al., 2005; Lloyd et al., 2002; Moberg et al., 2005; Thompson et al., 2005; Vaccari and Bilder, 2005). Depletion of hrs or Tsg101 in mammalian cells also results in increased EGFR signaling, although the two molecules have distinct effects on MVB morphology (Lu et al., 2003; Razi and Futter, 2006). In contrast, we find that mop and hrs mutants exhibit diminished EGFR signaling in vivo, and depletion of mop, Tsg101 or Vps28 reduces EGFR signaling in S2 cells. Progression through the endocytic pathway may thus be required for maximal EGFR signaling, at least in some contexts.

Several possible mechanisms could explain such a requirement for endocytic progression (Fig. 7). MAPK phosphorylation may be enhanced in the presence of signaling components present on late endosomes (Kim et al., 2007; Teis et al., 2006). Cleavage of the EGFR cytoplasmic domain, which requires Mop activity, might enhance EGFR signaling. The cleaved intracellular domain of ErbB4 has been shown to enter the nucleus and regulate gene expression (Sardi et al., 2006), suggesting the possibility that Mop affects a nuclear function of the EGFR in addition to promoting MAPK phosphorylation. Alternatively, the reduction in EGFR signaling in mop mutants could be due to a failure to recycle the receptor to the cell surface. Mutations in the yeast Vps class C genes, which are required for trafficking to late endosomes, also prevent the recycling of cargo proteins (Bugnicourt et al., 2004). Recycling is essential for EGFR-induced proliferation of mammalian cells (Tran et al., 2003), and may promote the localized RTK signaling that drives directional cell migration (Jekely and Rorth, 2003).

Specificity of mop function

Despite the reduction in EGFR signaling in mop mutants, signaling by other receptors such as Notch, Smoothened and Torso is unaffected. This phenotypic specificity could be due to a dedicated function of Mop in the EGFR pathway, or to high sensitivity of EGFR signaling to a general process that requires Mop. Although the Mop-related protein Alix has been found in a complex with the EGFR (Schmidt et al., 2004), we could not detect any physical interaction of Mop with the EGFR. The function of mop is not limited to promoting EGFR signaling; it also promotes trafficking of Wg and expression of the Wg target gene sens. In addition, mop is required for normal cellularization of the embryo, and its cellularization phenotype is not rescued by removal of cbl (data not shown).

Additional studies will be required to determine whether all endosomes, or only a specific subclass, are affected by mop. Interestingly, EGF treatment of mammalian cells induces EGFR trafficking through a specialized class of MVBs (White et al., 2006). Although we do not see significant colocalization of activated EGFR with Mop, the EGFR may transiently pass through Mop-containing endosomes before accumulating in another compartment. The wing disc appears less sensitive than the eye disc to the effect of mop on EGFR signaling. This might be due to differences in the endogenous levels of Cbl or other mediators of EGFR internalization, or in the strength or duration of signaling necessary to activate target genes, or to use of a different ligand with distinct effects on receptor trafficking.

Taken together, our results identify a positive role for progress through the endocytic pathway and for the novel molecule Mop in EGFR signaling in Drosophila. The importance of upregulation of the trafficking proteins Rab11a, Rab5a and Tsg101 for EGFR signaling in hepatomas and breast cancers (Fukui et al., 2007; Oh et al., 2007; Palmieri et al., 2006) highlights the potential value of specific effectors of EGFR endocytosis as targets for anti-cancer therapies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Diego Alvarado, Nick Baker, Hugo Bellen, Henry Chang, Bob Holmgren, Yuh-Nung Jan, Felix Karim, Helmut Kramer, Justin Kumar, Ruth Lehmann, Don Ready, Ilaria Rebay, Aloma Rodrigues, Trudi Schupbach, the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center, the Drosophila Genomics Resource Center and the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank for fly stocks and reagents. We are grateful to Elizabeth Savage for technical assistance. The manuscript was improved by the critical comments of Inés Carrera, Kerstin Hofmeyer, Kevin Legent and Josie Steinhauer. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (grant EY13777).

References

- Andersen JN, Mortensen OH, Peters GH, Drake PG, Iversen LF, Olsen OH, Jansen PG, Andersen HS, Tonks NK, Moller NP. Structural and evolutionary relationships among protein tyrosine phosphatase domains. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:7117–36. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.21.7117-7136.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache KG, Stuffers S, Malerod L, Slagsvold T, Raiborg C, Lechardeur D, Walchli S, Lukacs GL, Brech A, Stenmark H. The ESCRT-III subunit hVps24 is required for degradation but not silencing of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2513–23. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-10-0915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baonza A, Murawsky CM, Travers AA, Freeman M. Pointed and Tramtrack69 establish an EGFR-dependent transcriptional switch to regulate mitosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:976–80. doi: 10.1038/ncb887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bugnicourt A, Froissard M, Sereti K, Ulrich HD, Haguenauer-Tsapis R, Galan JM. Antagonistic roles of ESCRT and Vps class C/HOPS complexes in the recycling of yeast membrane proteins. Mol Biol Cell. 2004;15:4203–14. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-05-0420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao L, Zhang L, Ruiz-Lozano P, Yang Q, Chien KR, Graham RM, Zhou M. A novel putative protein-tyrosine phosphatase contains a BRO1-like domain and suppresses Ha-ras-mediated transformation. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:21077–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.33.21077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang HC, Hull M, Mellman I. The J-domain protein Rme-8 interacts with Hsc70 to control clathrin-dependent endocytosis in Drosophila. J Cell Biol. 2004;164:1055–64. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200311084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Childress JL, Acar M, Tao C, Halder G. Lethal giant discs, a novel C2-domain protein, restricts Notch activation during endocytosis. Curr Biol. 2006;16:2228–2233. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.09.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza N, Vallier LG, Fares H, Greenwald I. SEL-2, the C. elegans neurobeachin/LRBA homolog, is a negative regulator of lin-12/Notch activity and affects endosomal traffic in polarized epithelial cells. Development. 2007;134:691–702. doi: 10.1242/dev.02767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Guglielmo GM, Le Roy C, Goodfellow AF, Wrana JL. Distinct endocytic pathways regulate TGF-beta receptor signalling and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2003;5:410–21. doi: 10.1038/ncb975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dikic I. Mechanisms controlling EGF receptor endocytosis and degradation. Biochem Soc Trans. 2003;31:1178–81. doi: 10.1042/bst0311178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez M. Dual role for Hedgehog in the regulation of the proneural gene atonal during ommatidia development. Development. 1999;126:2345–53. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.11.2345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankfort BJ, Nolo R, Zhang Z, Bellen H, Mardon G. senseless repression of rough is required for R8 photoreceptor differentiation in the developing Drosophila eye. Neuron. 2001;32:403–14. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00480-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freeman M. Cell determination strategies in the Drosophila eye. Development. 1997;124:261–70. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukui K, Tamura S, Wada A, Kamada Y, Igura T, Kiso S, Hayashi N. Expression of Rab5a in hepatocellular carcinoma: Possible involvement in epidermal growth factor signaling. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:957–965. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00143.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ. In situ activation pattern of Drosophila EGF receptor pathway during development. Science. 1997a;277:1103–6. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5329.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabay L, Seger R, Shilo BZ. MAP kinase in situ activation atlas during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 1997b;124:3535–41. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.18.3535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher CM, Knoblich JA. The conserved c2 domain protein lethal (2) giant discs regulates protein trafficking in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2006;11:641–53. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghiglione C, Perrimon N, Perkins LA. Quantitative variations in the level of MAPK activity control patterning of the embryonic termini in Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1999;205:181–93. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golembo M, Schweitzer R, Freeman M, Shilo BZ. argos transcription is induced by the Drosophila EGF receptor pathway to form an inhibitory feedback loop. Development. 1996;122:223–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.122.1.223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruenberg J, Stenmark H. The biogenesis of multivesicular endosomes. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:317–23. doi: 10.1038/nrm1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guichard A, Biehs B, Sturtevant MA, Wickline L, Chacko J, Howard K, Bier E. rhomboid and Star interact synergistically to promote EGFR/MAPK signaling during Drosophila wing vein development. Development. 1999;126:2663–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.12.2663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heberlein U, Moses K. Mechanisms of Drosophila retinal morphogenesis: the virtues of being progressive. Cell. 1995;81:987–90. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(05)80003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herz HM, Chen Z, Scherr H, Lackey M, Bolduc C, Bergmann A. vps25 mosaics display non-autonomous cell survival and overgrowth, and autonomous apoptosis. Development. 2006;133:1871–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.02356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howe CL, Mobley WC. Long-distance retrograde neurotrophic signaling. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2005;15:40–8. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2005.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynes NE, Lane HA. ERBB receptors and cancer: the complexity of targeted inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:341–54. doi: 10.1038/nrc1609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ichioka F, Takaya E, Suzuki H, Kajigaya S, Buchman VL, Shibata H, Maki M. HD-PTP and Alix share some membrane-traffic related proteins that interact with their Bro1 domains or proline-rich regions. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;457:142–9. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2006.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaekel R, Klein T. The Drosophila Notch inhibitor and tumor suppressor gene lethal (2) giant discs encodes a conserved regulator of endosomal trafficking. Dev Cell. 2006;11:655–69. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janody F, Lee JD, Jahren N, Hazelett DJ, Benlali A, Miura GI, Draskovic I, Treisman JE. A mosaic genetic screen reveals distinct roles for trithorax and Polycomb group genes in Drosophila eye development. Genetics. 2004;166:187–200. doi: 10.1534/genetics.166.1.187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman AP, Sun Y, Jan LY, Jan YN. Role of the proneural gene, atonal, in formation of Drosophila chordotonal organs and photoreceptors. Development. 1995;121:2019–30. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.7.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekely G, Rorth P. Hrs mediates downregulation of multiple signalling receptors in Drosophila. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:1163–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.embor.7400019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekely G, Sung HH, Luque CM, Rorth P. Regulators of endocytosis maintain localized receptor tyrosine kinase signaling in guided migration. Dev Cell. 2005;9:197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jullien J, Gurdon J. Morphogen gradient interpretation by a regulated trafficking step during ligand-receptor transduction. Genes Dev. 2005;19:2682–94. doi: 10.1101/gad.341605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karim FD, Rubin GM. Ectopic expression of activated Ras1 induces hyperplastic growth and increased cell death in Drosophila imaginal tissues. Development. 1998;125:1–9. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzmann DJ, Odorizzi G, Emr SD. Receptor downregulation and multivesicular-body sorting. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:893–905. doi: 10.1038/nrm973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Taylor LJ, Bar-Sagi D. Spatial regulation of EGFR signaling by Sprouty2. Curr Biol. 2007;17:455–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.01.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J, Sitaraman S, Hierro A, Beach BM, Odorizzi G, Hurley JH. Structural basis for endosomal targeting by the Bro1 domain. Dev Cell. 2005;8:937–47. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein DE, Nappi VM, Reeves GT, Shvartsman SY, Lemmon MA. Argos inhibits epidermal growth factor receptor signalling by ligand sequestration. Nature. 2004;430:1040–4. doi: 10.1038/nature02840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lecuit T. Junctions and vesicular trafficking during Drosophila cellularization. J Cell Sci. 2004;117:3427–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JD, Kraus P, Gaiano N, Nery S, Kohtz J, Fishell G, Loomis CA, Treisman JE. An acylatable residue of Hedgehog is differentially required in Drosophila and mouse limb development. Dev Biol. 2001;233:122–36. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesokhin AM, Yu SY, Katz J, Baker NE. Several levels of EGF receptor signaling during photoreceptor specification in wild-type, Ellipse, and null mutant Drosophila. Dev Biol. 1999;205:129–44. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd TE, Atkinson R, Wu MN, Zhou Y, Pennetta G, Bellen HJ. Hrs regulates endosome membrane invagination and tyrosine kinase receptor signaling in Drosophila. Cell. 2002;108:261–9. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00611-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Q, Hope LW, Brasch M, Reinhard C, Cohen SN. TSG101 interaction with HRS mediates endosomal trafficking and receptor down-regulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:7626–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0932599100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhtala N, Odorizzi G. Bro1 coordinates deubiquitination in the multivesicular body pathway by recruiting Doa4 to endosomes. J Cell Biol. 2004;166:717–29. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miaczynska M, Christoforidis S, Giner A, Shevchenko A, Uttenweiler-Joseph S, Habermann B, Wilm M, Parton RG, Zerial M. APPL proteins link Rab5 to nuclear signal transduction via an endosomal compartment. Cell. 2004;116:445–56. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(04)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miura GI, Buglino J, Alvarado D, Lemmon MA, Resh MD, Treisman JE. Palmitoylation of the EGFR ligand Spitz by Rasp increases Spitz activity by restricting its diffusion. Dev Cell. 2006;10:167–76. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg KH, Schelble S, Burdick SK, Hariharan IK. Mutations in erupted, the Drosophila ortholog of mammalian tumor susceptibility gene 101, elicit non-cell-autonomous overgrowth. Dev Cell. 2005;9:699–710. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Motzny CK, Holmgren R. The Drosophila cubitus interruptus protein and its role in the wingless and hedgehog signal transduction pathways. Mech Dev. 1995;52:137–50. doi: 10.1016/0925-4773(95)00397-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nolo R, Abbott LA, Bellen HJ. Senseless, a Zn finger transcription factor, is necessary and sufficient for sensory organ development in Drosophila. Cell. 2000;102:349–62. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00040-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G. The multiple personalities of Alix. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3025–32. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Odorizzi G, Katzmann DJ, Babst M, Audhya A, Emr SD. Bro1 is an endosome-associated protein that functions in the MVB pathway in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Cell Sci. 2003;116:1893–903. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh KB, Stanton MJ, West WW, Todd GL, Wagner KU. Tsg101 is upregulated in a subset of invasive human breast cancers and its targeted overexpression in transgenic mice reveals weak oncogenic properties for mammary cancer initiation. Oncogene. 2007;26:5950–5959. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pai LM, Barcelo G, Schupbach T. D-cbl, a negative regulator of the Egfr pathway, is required for dorsoventral patterning in Drosophila oogenesis. Cell. 2000;103:51–61. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)00104-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palmieri D, Bouadis A, Ronchetti R, Merino MJ, Steeg PS. Rab11a differentially modulates Epidermal growth factor-induced proliferation and motility in immortal breast cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2006;100:127–137. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9244-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker DS, Jemison J, Cadigan KM. Pygopus, a nuclear PHD-finger protein required for Wingless signaling in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:2565–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.11.2565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier A, Chauvin JP, Lecuit T. Trafficking through Rab11 endosomes is required for cellularization during Drosophila embryogenesis. Curr Biol. 2003;13:1848–57. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2003.10.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullikuth A, McKinnon E, Schaeffer HJ, Catling AD. The MEK1 scaffolding protein MP1 regulates cell spreading by integrating PAK1 and Rho signals. Mol Cell Biol. 2005;25:5119–33. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.12.5119-5133.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Queenan AM, Ghabrial A, Schupbach T. Ectopic activation of torpedo/Egfr, a Drosophila receptor tyrosine kinase, dorsalizes both the eggshell and the embryo. Development. 1997;124:3871–80. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.19.3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raymond CK, Howald-Stevenson I, Vater CA, Stevens TH. Morphological classification of the yeast vacuolar protein sorting mutants: evidence for a prevacuolar compartment in class E vps mutants. Mol Biol Cell. 1992;3:1389–402. doi: 10.1091/mbc.3.12.1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razi M, Futter CE. Distinct roles for Tsg101 and Hrs in multivesicular body formation and inward vesiculation. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:3469–83. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-11-1054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richter C, West M, Odorizzi G. Dual mechanisms specify Doa4-mediated deubiquitination at multivesicular bodies. EMBO J. 2007;26:2454–64. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rink J, Ghigo E, Kalaidzidis Y, Zerial M. Rab conversion as a mechanism of progression from early to late endosomes. Cell. 2005;122:735–49. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.06.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rives AF, Rochlin KM, Wehrli M, Schwartz SL, DiNardo S. Endocytic trafficking of Wingless and its receptors, Arrow and DFrizzled-2, in the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2006;293:268–83. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodrigues AB, Werner E, Moses K. Genetic and biochemical analysis of the role of Egfr in the morphogenetic furrow of the developing Drosophila eye. Development. 2005;132:4697–707. doi: 10.1242/dev.02058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roignant JY, Hamel S, Janody F, Treisman JE. The novel SAM domain protein Aveugle is required for Raf activation in the Drosophila EGF receptor signaling pathway. Genes Dev. 2006;20:795–806. doi: 10.1101/gad.1390506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sardi SP, Murtie J, Koirala S, Patten BA, Corfas G. Presenilin-dependent ErbB4 nuclear signaling regulates the timing of astrogenesis in the developing brain. Cell. 2006;127:185–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh AK, O’Tousa JE, Ozaki K, Ready DF. Rab11 mediates post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin to the photosensitive apical membrane of Drosophila photoreceptors. Development. 2005;132:1487–97. doi: 10.1242/dev.01704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt MH, Hoeller D, Yu J, Furnari FB, Cavenee WK, Dikic I, Bogler O. Alix/AIP1 antagonizes epidermal growth factor receptor downregulation by the Cbl-SETA/CIN85 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:8981–93. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.20.8981-8993.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweitzer R, Shaharabany M, Seger R, Shilo BZ. Secreted Spitz triggers the DER signaling pathway and is a limiting component in embryonic ventral ectoderm determination. Genes Dev. 1995;9:1518–29. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.12.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto ES, Bellen HJ. Internalization is required for proper Wingless signaling in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:95–106. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200510123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seto ES, Bellen HJ, Lloyd TE. When cell biology meets development: endocytic regulation of signaling pathways. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1314–36. doi: 10.1101/gad.989602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevrioukov EA, He JP, Moghrabi N, Sunio A, Kramer H. A role for the deep orange and carnation eye color genes in lysosomal delivery in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 1999;4:479–86. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80199-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shilo BZ. Signaling by the Drosophila epidermal growth factor receptor pathway during development. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:140–9. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00094-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sriram V, Krishnan KS, Mayor S. deep-orange and carnation define distinct stages in late endosomal biogenesis in Drosophila melanogaster. J Cell Biol. 2003;161:593–607. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200210166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein JA, Broihier HT, Moore LA, Lehmann R. Slow as molasses is required for polarized membrane growth and germ cell migration in Drosophila. Development. 2002;129:3925–34. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.16.3925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern KA, Visser Smit GD, Place TL, Winistorfer S, Piper RC, Lill NL. Epidermal growth factor receptor fate is controlled by Hrs tyrosine phosphorylation sites that regulate Hrs degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:888–98. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02356-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaminathan G, Tsygankov AY. The Cbl family proteins: ring leaders in regulation of cell signaling. J Cell Physiol. 2006;209:21–43. doi: 10.1002/jcp.20694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney ST, Davis GW. Unrestricted synaptic growth in spinster-a late endosomal protein implicated in TGF-beta-mediated synaptic growth regulation. Neuron. 2002;36:403–16. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)01014-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teis D, Huber LA. The odd couple: signal transduction and endocytosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:2020–33. doi: 10.1007/s00018-003-3010-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teis D, Taub N, Kurzbauer R, Hilber D, de Araujo ME, Erlacher M, Offterdinger M, Villunger A, Geley S, Bohn G, et al. p14-MP1-MEK1 signaling regulates endosomal traffic and cellular proliferation during tissue homeostasis. J Cell Biol. 2006;175:861–8. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200607025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson BJ, Mathieu J, Sung HH, Loeser E, Rorth P, Cohen SM. Tumor suppressor properties of the ESCRT-II complex component Vps25 in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2005;9:711–20. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyooka S, Ouchida M, Jitsumori Y, Tsukuda K, Sakai A, Nakamura A, Shimizu N, Shimizu K. HD-PTP: A novel protein tyrosine phosphatase gene on human chromosome 3p21.3. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;278:671–8. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran DD, Russell HR, Sutor SL, van Deursen J, Bram RJ. CAML is required for efficient EGF receptor recycling. Dev Cell. 2003;5:245–56. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00207-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsuda M, Seong KH, Aigaki T. POSH, a scaffold protein for JNK signaling, binds to ALG-2 and ALIX in Drosophila. FEBS Lett. 2006;580:3296–300. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaccari T, Bilder D. The Drosophila tumor suppressor vps25 prevents nonautonomous overproliferation by regulating Notch trafficking. Dev Cell. 2005;9:687–98. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2005.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Werz C, Xu D, Chen Z, Li Y, Hafen E, Bergmann A. Drosophila cbl Is essential for control of cell death and cell differentiation during eye development. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1447. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White IJ, Bailey LM, Aghakhani MR, Moss SE, Futter CE. EGF stimulates annexin 1-dependent inward vesiculation in a multivesicular endosome subpopulation. EMBOJ. 2006;25:1–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams RL, Urbe S. The emerging shape of the ESCRT machinery. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2007;8:355–68. doi: 10.1038/nrm2162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Baker NE. Cell cycle withdrawal, progression, and cell survival regulation by EGFR and its effectors in the differentiating Drosophila eye. Dev Cell. 2003;4:359–69. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00059-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zecca M, Basler K, Struhl G. Direct and long-range action of a Wingless morphogen gradient. Cell. 1996;87:833–44. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81991-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhai RG, Hiesinger PR, Koh TW, Verstreken P, Schulze KL, Cao Y, Jafar-Nejad H, Norga KK, Pan H, Bayat V, et al. Mapping Drosophila mutations with molecularly defined P element insertions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:10860–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1832753100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.