Abstract

We aimed to investigate the history of abuse in childhood and adulthood and health-related quality of life (HRQL) in women and men with FGID in the general adult population. A cross-sectional study in a random population sample (n = 1,537, 20–87 years) living in Östhammar municipality, Sweden, in 1995 was performed. Persons with FGID (n = 141) and a group of abdominal symptom-free controls (SSF, n = 97) were selected by means of a validated questionnaire assessing gastrointestinal symptoms (the ASQ). Abuse, anxiety and depression (the HADS) and HRQL (the PGWB) were measured. Women with FGID had a higher risk of having a history of some kind of abuse, as compared with the SSF controls (45% vs.16%, OR = 2.0, 95% CI: 1.01–3.9; SSF = 1), in contrast to men (29% vs. 24% n.s.). Women with a history of abuse and FGID had reduced HRQL 91 (95% CI 85–97) as compared with women without abuse history 100 (95% CI 96–104, P = 0.01, “healthy” = 102–105 on PGWB). Childhood emotional abuse was a predictor for consulting with OR = 4.20 (95% CI: 1.12–15.7.7). Thus, previous abuse is common in women with FGID and must be considered by the physician for diagnosis and treatment of the disorder.

Keywords: Functional gastrointestinal disorders, Irritable bowel syndrome, Abused women, Child abuse

Introduction

Maltreatment, threats or violence from another person, often an intimate partner, is psychosocially traumatic and a growing problem in society. During the last decade, 1997–2006, the number of assaults reported to the police in Sweden increased by 40%, to 1,079/100,000 inhabitants, and the number of sexual offences increased by 57% to 137/100,000, of which rapes increased by 142% to 46/100,000. The latter high percentage is partly attributable to a change in the Swedish legislation that lowered the threshold at which sexual offence is classified as rape. For children (0–15 years) the number of assaults reported to the police has increased by 64% to 97/100,000 and the number of rapes has increased during the last decade by 300% to 12/100,000 [1].

About half of the women in Canada and Sweden have been described as having experienced at least one incident of violence by a man since the age of 16 [2, 3], and in a Japanese study three quarters of the women said they had experienced sexual, physical or emotional intimate partner violence [4]. A population survey in Los Angeles reported a childhood (lifetime for age <16 years) sexual assault prevalence of 6.8% in women and 3.8% in men [5], and 10.5% in adults [6].

Functional gastrointestinal disorders (FGIDs) are a group of digestive diseases with a chronic or recurrent course in the absence of organic illness likely to explain the symptoms [7]. The most frequent FGIDs are irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), with an average estimated prevalence of 12%, and functional dyspepsia with a prevalence of 25% in the general adult population, but with a considerable proportion of persons with overlapping symptoms [8]. Most studies on IBS report more sufferers among women than men [9]. The difference in prevalence of dyspepsia between women and men is inconsistent; some studies report a higher prevalence of symptoms of dyspepsia in women than in men [10, 11], whereas others do not find any sex difference [12, 13]. Although FGID is common, only about 50% of people who have symptoms of dyspepsia ever seek medical attention for it [14, 15], while the consulting figures for IBS are somewhat higher [15]. FGIDs constitute about 5% of all consultations in primary care [16], and only a minority is referred to secondary care [17, 18].

Nevertheless, FGID accounts for up to 50% of all gastroenterology consultations [19].

The pathogenesis of FGID is at present often explained using the biopsychosocial model in which biologic and psychosocial factors participate in the origin of symptoms [20].

An overrepresentation of a history of past abuse has been reported in both patients and non-patients with IBS and among non-patients with functional dyspepsia [21, 22]. However, investigating abuse is difficult among patients with abdominal distress, since sexual and physical abuses are seldom reported to doctors by their patients [23].

Our aims were to investigate the occurrence of a history of sexual, physical or emotional abuse experienced in childhood or later in life among women and men with FGID in the general population and the possible association with consultation rate, as compared with subjects free from FGID, controlling for age, sex, education and psychological distress.

Methods

Setting and sampling

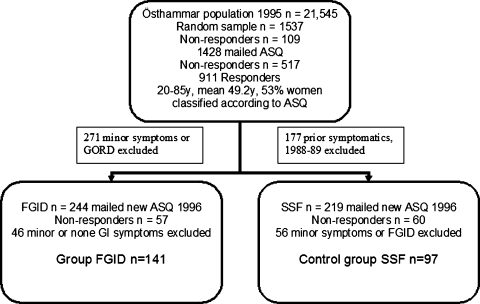

A population sample (n = 1,537) drawn from the National Swedish Population Registry in 1995 involved men and women 20–87 years of age, born on day 3, 12 or 24 of each month living in Östhammar municipality. The sampling method is equivalent to random sampling since there is no reason to believe that date of birth is associated with the variables measured. The subjects were sent a validated postal questionnaire, called “The Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire” (ASQ) [24]. The responders (n = 911) in the population sample were classified according to their responses in the ASQ as having either functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID n = 244), i.e., functional dyspepsia or irritable bowel syndrome, but not predominant symptoms on gastroesophageal reflux, or being strictly symptom free (SSF n = 219), i.e., having reported no gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms and also no GI symptoms reported by subjects who also participated in two previous population studies in 1988–1989 [25].

In 1996, the FGID (n = 244) and SSF (n = 219) sample groups were invited by mail to an appointment at one of their six local health centres. About 187 (77%) with FGID and 156 (71%) SSF accepted the invitation. At the health centre they filled in the ASQ once again together with other questionnaires about health-related quality of life (HRQL) and their abuse history. A nurse assisted only when needed. With the same criteria for FGID applied to this ASQ response, 141 with FGID (IBS and dyspepsia: 99; only dyspepsia: 40; only IBS: 2) and 97 SSF remained, and thus constituted the study groups. Thus the FGID symptomatics were classified as FGID twice, in 1996 and 1995, and the symptom-free SSF group up to four times in 1996, 1995, 1989 and 1988. This sampling procedure assured persistent symptom status in the two study groups, as has been presented earlier [26] and in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Formation and sampling procedure for the study groups from the population of Östhammar

Questionnaires

The Abdominal Symptom Questionnaire (ASQ) has previously been validated and found reliable and reproducible [27–29]. The definition of FGID used in this study is dyspepsia, IBS or both, as taken from the ASQ. Solitary heartburn and/or regurgitations were symptoms not included in our definition of dyspepsia, which is in agreement with the current ROME III definition [30]. In the Abuse Questionnaire, the questions about sexual abuse were those initially developed for the National Population Survey of Canada [2] from survey questionnaires that fulfill reliability criteria [31]. The questions were translated into Swedish and back-translated into English for validation. Questions were written separately for childhood ≤13 years and adulthood (>13), including six categories of abuse: sexual, physical and emotional, each as a child or as an adult [23].

The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) index is a health-related quality of life instrument including 22 items divided into six domains: anxiety, depressed mood, positive well-being, self-control, general health and vitality. Items are scored on a six-grade Likert scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQL. The total score with a high responsiveness and validity for dyspepsia [32] was used in this study. HRQL values varying between 102 and 105 have been observed in a normal healthy population [33]. The total score was dichotomized at the median with a cut-off point 107/108 at the upper 95% CI for functional dyspepsia. Consequently, a good HRQL was considered to be a total score of 108 or more, which was reached by 117 subjects (score 108–132; mean 117.5, SD = 6.3), while a poor HRQL was reached by 120 subjects (score 49–107; mean 90.8, SD = 12.6).

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a validated, reliable instrument with subscales for measuring anxiety and depression [34–36]. The questionnaire has seven items, graded 0–3, with possible ranges of 0–21 for each subscale (total minimum score of 0, total maximum score of 42). A score of 7 or less on each subscale (out of a maximum of 21) denotes a non-case, 8–10 a doubtful case, and 11 or more a definite case of anxiety or depression. The cut-off point 10/11 was set for identifying sufferers in this study.

All participants per definition completed the ASQ, 231 (97.1%) the Abuse Questionnaire, 237 (99.6%) the PGWB questionnaire and 217 (91.1%) the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Questionnaire.

Educational background was registered at five levels and dichotomized, with low including elementary, comprehensive, secondary level and high upper secondary, university level. Data of previous consultations for GI symptoms and educational background were taken from questions added to the 1995 ASQ.

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Medical Faculty, Uppsala University, on 5 June 1996.

Statistical analyses

A Spearman rank correlation test was performed for the variables anxiety, depression and quality of life. A multiple logistic regression analysis was performed with FGID/SSF and consulters/non-consulters as outcome variables, each of the abuse variables as exposure variables and the possible confounding factors: age (−40/40- years), sex (female/male), education level, anxiety (1-HADS subscale >10, 0-HADS subscale <11), depression (1-HADS subscale >10, 0-HADS subscale <11) and HRQL score (1-PGWB >108, 0-PGWB ≤108) as explanatory variables. In order to adjust for the influence of explanatory variables the variables were added one by one with a forward stepwise multiple logistic regression technique [37], and if the variable affected the odds ratios of the outcome variables less than ±10% and with P > 0.10, the variable was eliminated from the model. The Hosmer–Lemeshow goodness-of-fit test was performed for each model, and model improvements were tested with the likelihood-ratio test. Tests for interactions were completed between the abuse variables and age, sex and HRQL. No significant interactions were found. STATA version 9.2 statistical package [38] was used for the analyses.

Results

Demography and sexual, physical and emotional abuse

The distribution of age, sex, education, GI consultation, anxiety, depression, HRQL and sexual, physical and emotional abuse for persons with FGID and SSF is presented in Table 1. Forty-one percent of those with FGID had experienced some kind of abuse, as compared with 20% (P < 0.01) among SSF controls. Impaired anxiety and HRQL were significantly more common among subjects exposed to prior abuse, while depression was not.

Table 1.

Distribution of age, sex, education, previous GI consultation and abuse for women and men with functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) and strictly GI symptom free (SSF) and previous consulters/non-consulters for FGID

| FGID (n = 141) n (%) |

SSF (n = 97) n (%) |

Statistic P | Consulters GI (n = 99) n (%) |

Non-consulters GI (n = 39) n (%) |

Statistic P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age years (SD)b | 45.7 (14.3) | 52.4 (15.4) | 0.0007 | 46.7 (13.4) | 41.4 (14.2) | 0.041 |

| Femalea | 93 (66.0) | 51 (52.6) | 0.038 | 66 (66.7) | 26 (66.7) | 0 1 |

| Completed high schoola | 66 (47.1) | 28 (29.5) | 0.007 | 43 (43.4) | 23 (60.0) | 0.100 |

| Consulted for GI evera | 99 (71.7) | 8 (8.3) | <0.001 | Not relevant | Not relevant | |

| Psychological general well-beingb | 96.8 | 114.6 | <0.0001 | 96.8 | 96.6 | 0.963 |

| Anxietya | 13 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.002 | 5 (7.5) | 8 (13.1) | 0.507 |

| Depressiona | 5 (4.8) | 1 (1.7) | 0.319 | 3 (5.4) | 2 (4.3) | 0.942 |

| Childhood abuse | ||||||

| Childhood sexual abusea | 19 (13.9) | 3 (3.1) | 0.006 | 16 (16.5) | 3 (7.9) | 0.196 |

| Childhood physical abusea | 15 (11.0) | 3 (3.2) | 0.029 | 14 (14.4) | 1 (2.6) | 0.050 |

| Childhood emotional abusea | 37 (27.4) | 15 (16.1) | 0.046 | 32 (33.7) | 5 (13.2) | 0.017 |

| Any childhood abusea | 43 (31.4) | 18 (18.8) | 0.031 | 37 (38.1) | 6 (15.8) | 0.012 |

| Adulthood abuse | ||||||

| Adult sexual abusea | 17 (12.4) | 2 (2.1) | 0.005 | 14 (14.4) | 3 (7.9) | 0.303 |

| Adult physical abusea | 3 (2.2) | 1 (1.1) | 0.513 | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 0.273 |

| Adult emotional abusea | 32 (23.7) | 5 (5.4) | <0.001 | 24 (25.3) | 8 (21.1) | 0.608 |

| Any adulthood abusea | 40 (29.2) | 8 (8.3) | <0.001 | 30 (30.9) | 10 (26.3) | 0.598 |

| Any childhood, not adulthood, abusea | 16 (14.6) | 11 (12.4) | 0.654 | 15 (20.0) | 1 (3.0) | 0.022 |

| Any adulthood, not childhood, abusea | 13 (11.8) | 1 (1.1) | 0.003 | 8 (10.7) | 5 (15.2) | 0.509 |

| Any abuse (child or adult) | ||||||

| Sexual abusea | 30 (21.9) | 4 (4.2) | <0.001 | 25 (25.8) | 5 (13.2) | 0.113 |

| Physical abusea | 17 (12.4) | 3 (3.2) | 0.014 | 16 (16.5) | 1 (2.6) | 0.029 |

| Emotional abusea | 48 (35.6) | 15 (16.1) | 0.001 | 39 (41.1) | 9 (23.7) | 0.060 |

| Any abusea | 56 (40.9) | 19 (19.8) | 0.001 | 45 (46.4) | 11 (29.0) | 0.064 |

aPearson chi2-test, b Student’s t-test

Women

There were 144 women, 93 with FGID and 51 SSF in the study. Almost half of the women, 42 out of 93 (45%) with FGID, had a history of abuse, in contrast to the 8 out of 51 (16%, P < 0.01) SSF controls. Women with FGID had a higher prevalence than SSF women for sexual, physical and emotional abuse in childhood and for sexual and emotional abuse in adulthood, as presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The number of people and the proportion of individuals (%) with a history of sexual, physical and emotional abuse in women and men with a functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) and strictly GI symptom free (SSF). The total number of FGID/SSF for both childhood and adulthood abuse in women was 93/51 and 48/46 in men

| Childhood abuse number FGID/SSF n(%) P | Adulthood abuse number FGID/SSF n(%) P | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sexual | Physical | Emotional | Any | Sexual | Physical | Emotional | Any | |

| Women | 18(19)/3(6) 0.027 | 11(12)/1(2) 0.048 | 26(28)/5(10) 0.021 | 32(34)/7(14) 0.006 | 14(15)/2(4) 0.044 | 2(2)/0(0) 0.403 | 24(26)/2(4) 0.001 | 31(33)/4(8) <0.001 |

| Men | 1(1)/0(0) 1.00 | 4(8)/2(4) 0.876 | 11(23)/10(22) 0.937 | 11(23)/11(24) 1.00 | 3(6)/0(0) 0.331 | 1(2)/1(2) 1.00 | 8(17)/3(7) 0.343 | 9(19)/4(9) 0.382 |

P value computed with Fisher’s exact two-sided test

Out of the 50 women with a history of abuse, 24 (48%, FGID n = 21, SSF n = 3, P < 0.01) had experienced sexual, physical or emotional abuse both in childhood and as adults. In the FGID group, 42 (46%) women reported abuse in childhood and/or adulthood, as compared with 8 (16%, P < 0.01) in the SSF group. Moreover, in the FGID group, 32 (35%) women had a history of childhood abuse as compared with 7 (14%, P < 0.01) in the SSF group.

Men

In contrast to the women, the men had no significant difference for a history of abuse: 14 out of 48 (29%) men with FGID versus 11 out of 46 (24%, P = 0.69) SSF men. Similarly, no statistically significant difference was found for a history of sexual, physical or emotional abuse in the subgroups childhood and adulthood for men; see Table 2.

Anxiety and depression

Women and men with FGID significantly more often reported anxiety (P < 0.01), consultations for GI problems (P = 0.02), childhood abuse (P < 0.01) and adulthood abuse (P < 0.01) than SSF women and men. In contrast, depression had no significant univariate association with FGID, GI consulting, childhood abuse or adulthood abuse. FGID (OR = 2.1, 95% CI: 1.1–4.0) and anxiety (OR = 10.7, 95% CI: 2.3–51) were the only remaining independent predictors for abuse when adjusted for age, sex, education and depression when tested with the multiple logistic regression technique.

Quality of life

Subjects with FGID had a significant reduction in HRQL, as measured by the PGWB, with a mean value of 97 (95% CI: 94–99), as compared with SSF controls, who scored 115 (95% CI: 112–116). There was no significant difference in HRQL between women and men either for the FGID subjects (women 96; 95% CI: 92–99; men 99; 95% CI: 95–102) or for the SSF group (women 114; 95% CI: 110–117; men 115; 95% CI: 112–119). Women with a history of some kind of abuse and FGID had significantly reduced HRQL, with a mean value of 91 (95% CI: 85–97) as compared with a mean value of 100 (95% CI: 96–104) for women without abuse history. Similarly, men with a history of some kind of abuse and FGID had significantly reduced quality of life, with a mean value of 90 (95% CI: 82–99) as compared with a mean value of 102 (95% CI: 98–105) for men without abuse history.

The HRQL for FGID consulters and non-consulters was the same; both groups had a mean value of 97 with 95% CI 93–100 and 92–102, respectively. However, FGID consulters with a history of abuse had significantly lower HRQL, with a mean value of 92 (95% CI: 86–97), than FGID consulters without a history of abuse with a mean value of 100 (95% CI: 97–104, P < 0.05). There was a significant negative correlation between HRQL and anxiety [r = −0.61 (P < 0.01)] and between HRQL and depression [r = −0.54 (P < 0.01)].

Multivariate risk modeling

Persons with FGID had higher odds ratio 2.2 (95% CI: 1.1–4.4) of a history of some kind of abuse (in childhood or adulthood, sexual, physical or emotional) as compared with the SSF controls adjusted for age, sex and HRQL (main model, adding the variable anxiety or education did not improve the model). Some kind of abuse in adulthood had odds ratio 2.8 (95% CI: 1.1–7.1) with the same strategy. Emotional abuse in adulthood had the highest (and only significant) odds ratio 3.1 (95% CI: 1.0–9.4), while sexual abuse did not reach significance. In childhood, physical abuse seems to have the highest odds ratio 2.9 (95% CI: 0.7–12) for future FGID, although significance was not reached in this study (data not shown).

With the main model, women had significantly high odds ratios for FGID: from some kind of abuse 3.13 (95% CI: 1.21–8.10), emotional abuse 3.66 (95% CI: 1.22–11.0), physical abuse 5.07 (95% CI: 0.55–47.1) and sexual abuse 3.03 (95% CI: 0.89–10.3); the latter two types of abuse did not reach significance, as presented in Table 3. There were significant high odds ratios in women with the crude model for FGID from all types of abuse in childhood and adulthood, except adult physical abuse (probably owing to the small number of observations). Similarly, with the main model, there were high odds ratios in women, but they did not reach significance, see Table 3.

Table 3.

Odds ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI) for having a functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) (logistic regression) in different groups of abuse, women and men, in crude model and main model adjusted for age and HRQL

| Variable | Crude model | Main model (adjusted for age and HRQL) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | Women | Men | |

| Childhood abuse | ||||

| No childhood sexual abuse | 1 | 1 | ||

| Childhood sexual abuse | 3.95 (1.10–14.1) | * | 2.44 (0.60–10.0) | * |

| No childhood physical abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Childhood physical abuse | 6.88 (0.86–54.9) | 1.95 (0.34–11.2) | 4.93 (0.53–46.3) | 1.61 (0.21–12.3) |

| No childhood emotional abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Childhood emotional abuse | 3.71 (1.32–10.4) | 1.00 (0.38–2.68) | 2.71 (0.87–8.4) | 1.14 (0.37–3.55) |

| No childhood abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Any childhood abuse | 3.41 (1.38–8.43) | 0.94 (0.36–2.47) | 2.50 (0.91–6.85) | 1.10 (0.36–3.38) |

| Adulthood abuse | ||||

| No adult sexual abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Adult sexual abuse | 4.45 (0.97–20.5) | * | 3.20 (0.60–16.9) | 1.51 (0.53–4.29) |

| No adult physical abuse | 1 | 1 | ||

| Adult physical abuse | * | 0.93 (0.06–15.4) | * | 0.84 (0.03–25.3) |

| No adult emotional abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Adult emotional abuse | 8.86 (2.00–39.3) | 2.74 (0.67–11.1) | 3.42 (0.70–16.9) | 2.78 (0.55–14.0) |

| No adulthood abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Any adulthood abuse | 6.07 (2.00–18.4) | 2.43 (0.69–8.57) | 3.10 (0.92–10.3) | 2.41 (0.55–10.5) |

| Any abuse (child or adult) | ||||

| No sexual abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | |

| Sexual abuse | 3.57 (1.34–9.5) | * | 3.03 (0.89–10.3) | 1.49 (0.52–4.24) |

| No physical abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Physical abuse | 7.59 (0.96–60.2) | 2.5 (0.46–13.6) | 5.07 (0.55–47.1) | 1.84 (0.26–13.0) |

| No emotional abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Emotional abuse | 5.83 (2.11–16.1) | 1.26 (0.48–3.28) | 3.66 (1.22–11.0) | 1.31 (0.43–3.95) |

| No abuse | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Any abuse | 4.61 (1.95–10.9) | 1.31 (0.52–3.32) | 3.13 (1.21–8.10) | 1.32 (0.45–3.90) |

1 = Reference, * too few observations

In contrast, men did not have the same elevation of odds ratio for FGID from any type of abuse as compared to women. The highest odds ratio in men for FGID was for some kind of adulthood abuse and was 2.41 (95% CI: 0.55–10.5), while adult emotional abuse was 2.78 (95% CI: 0.55–14.0), but neither were significant; see Table 3.

Consulters and non-consulters with FGID

Consulters with FGID more often (46% of them) had a history of abuse as compared with non-consulters (29%, P = 0.06), although it did not reach significance as shown in Table 1. Some kind of abuse in childhood was more prevalent: 38% in consulters versus 16% in non-consulters (P = 0.01) and correspondingly for childhood emotional abuse 34% and 13% (P = 0.02) and for childhood physical abuse 14% and 3% (P = 0.05). Moreover, there was a significantly higher prevalence of physical abuse in childhood or adulthood in consulters, 17%, versus non-consulters, 3%, P = 0.03. Female consulters with a history of some kind of abuse had an odds ratio of 2.47 (95% CI: 0.92–6.7), and with a history of childhood emotional abuse this was significant, 4.20 (95% CI: 1.12–15.7.7), in contrast to male consulters, with an odds ratio of 1.66 (95% CI: 0.37–7.50) for some kind of abuse and 2.10 (95% CI: 0.37–12.0) for childhood emotional abuse.

Discussion

Women, but not men, with longstanding FGID often have a history of abuse. Women with FGID reported past sexual, physical or emotional abuse in 45% of the cases, as compared with 16% for women without FGID, 29% in men with FGID and 25% in men without FGID. In this study emotional and sexual abuse are the most common type of threats to women’s health related to FGID. This study also shows that childhood emotional abuse is a predictor for consulting for GI problems. Moreover, longstanding FGID is associated with a significantly reduced HRQL, and a history of abuse further reduces the HRQL in women and men. The findings reveal that a history of abuse is an important psycho-social factor linked to FGID in women. In contrast, the association in men is less clear, although men with a history of some kind of abuse and FGID had significantly reduced HRQL as compared with men with FGID without any history of abuse.

Our study does not support the idea that consulters with FGID generally have a poorer HRQL than non-consulters, but a history of abuse had a negative effect on HRQL for consulters with FGID.

Most studies that investigate FGID use a technique that implies questioning the subjects of the experiment at a single point in time. One of the strengths of this study is the repetitive sampling procedure, which makes it possible to compare individuals with longstanding FGID with persistently symptom-free individuals in the same population. We consider that our findings can be generalized to the general population, as the study groups were sampled from a well-defined and thoroughly investigated population [24, 26]. The individuals answered the abuse questionnaire in a quiet, safe environment, in reality anonymously, with the support of a nurse only when needed, which was an advantage since patients tend to underreport abuse when asked face to face by a doctor [23].

The abuse questionnaire has not been thoroughly validated in a Swedish population, but the questions are straightforward and the questionnaire was translated into Swedish and back-translated into English. The definition of functional dyspepsia and IBS used is not exactly the same as the now recommended Rome III criteria [39]. The definitions of dyspepsia and IBS used in this study were those used in the original study from 1988 [25], before current recommendations were available. We opted to retain our original study definition since our IBS definition was in accordance with the Rome III criteria and our definition of dyspepsia was more restricted in terms of symptoms, but wider in terms of abdominal location. We consider the overall prevalence of FGID in this study and the concordance on an individual level to be applicable within the current definition [39], and thus we consider our results conclusive.

Previous studies in the field have reported that about half the patients referred to a gastroenterology clinic had a history of sexual or physical abuse [23, 40]. Moreover, 71% of women who reported domestic violence to the police had FGID according to Perona et al. [41]. In the literature, a history of childhood or adult abuse characterizes patients who present with a variety of functional symptoms apart from FGID [42]: headaches [43], pelvic pain [44], panic disorders [45], non-epileptic attack disorders [46] and back pain [47]. Psychological factors such as anxiety [48], as well as physiological factors such as enhanced visceral sensitivity, all contributed to a poor health outcome [42]. Only a few studies have focused on abuse and FGID in the general population, where Koloski et al. [22] found abuse to be significantly associated with IBS and/or functional dyspepsia, but less important when psychosocial factors were controlled for, a finding confirmed by others [49, 50].

The same research team [51] found that past sexual, physical and emotional abuse was not a significant predictor for seeking health care, in contrast to our finding that a history of childhood emotional abuse was associated with consulting, and anxiety and FGID were independent predictors for previous abuse. It is clear from our study that many subjects with traumatic memories and uncomfortable symptoms never seek health care and that when they do it is important to take a thorough medical history.

There is a bi-directional communication between the gut and the brain through the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis [51] that can mediate an emotional trauma such as previous abuse. Common links suggested are neuroticism [49], generally diminished pain threshold [52] and current depression [53]. There is a higher incidence of childhood abuse reported for women than for men in this study as in others [5]. This could explain the significant relation of consulting and childhood emotional abuse for women, but not for men found in this study, suggesting that FGID in some patients might be a sequel of previous abuse. The treatments available to date for FGIDs are of limited value. Creed et al. [54] have reported that psychological treatment and antidepressants are effective in patients with IBS and a history of sexual abuse, which stresses the importance of discovering past abuse in patients with FGID. Future studies must focus on how the knowledge of a patient’s previous exposure to different kinds of abuse and the effects of different kind of psychotherapy can improve the treatment for at least a subset of FGID sufferers.

Conclusions

We conclude that women with longstanding FGID in many cases have a history of physical, emotional or sexual abuse in childhood or adulthood, which is associated with a poor HRQL and increased health care seeking. This is important for physicians to consider when diagnosing and treating FGID in women.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank all personnel at the six primary care health centres in Östhammar for collecting the data and Linda Schenck for proofreading.

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Crime statistics. (2007) cited; Available from: http://www.bra.se. Accessed 14 March 2007

- 2.Badgley R, Allard H, McCormick N et al (1984) Occurence in the population. In: Sexual offences against children. Canadian Government Publishing Centre, Ottawa, pp 175–193

- 3.Lundgren E, Heimer G, Westerstrand J, Kalliokoski A (2002) Captured queen; Men’s violence against women in “equal” Sweden—a prevalence study. The Swedish National Council for Crime Prevention (BRÅ), Umeå

- 4.Yoshihama M, Sorenson SB (1994) Physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by male intimates: experiences of women in Japan. Violence Vict 9(1):63–77 [PubMed]

- 5.Siegel JM, Sorenson SB, Golding JM, Burnam MA, Stein JA (1987) The prevalence of childhood sexual assault. The Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Am J Epidemiol 126(6):1141–1153 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Sorenson SB, Stein JA, Siegel JM, Golding JM, Burnam MA (1987) The prevalence of adult sexual assault. The Los Angeles Epidemiologic Catchment Area Project. Am J Epidemiol 126(6):1154–1164 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Drossman DA (1999) The functional gastrointestinal disorders, the Rome II process. Gut 45(Suppl 2):II1–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Agreus L, Talley NJ (1998) Dyspepsia: current understanding and management. Annu Rev Med 49:475–493 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 9.Agréus L (1998) The epidemiology of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Eur J Surg 164(Suppl 583):60–66 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, Tibblin G (1994) The epidemiology of abdominal symptoms: prevalence and demographic characteristics in a Swedish adult population. A report from the Abdominal Symptom Study. Scand J Gastroenterol 29(2):102–109 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Bernersen B, Johnsen R, Straume B, Burhol PG, Jenssen TG, Stakkevold PA (1990) Towards a true prevalence of peptic ulcer: the Sørreisa gastrointestinal disorder study. Gut 31(9):989–992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Drossman DA, Li Z, Andruzzi E, Temple RD, Talley NJ, Thompson WG et al (1993) U.S. householder survey of functional gastrointestinal disorders. Prevalence, sociodemography, and health impact. Dig Dis Sci 38(9):1569–1580 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, Melton LJD (1992) Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 102(4 Pt 1):1259–1268 [PubMed]

- 14.Westbrook JI, McIntosh J, Talley NJ (2000) Factors associated with consulting medical or non-medical practitioners for dyspepsia: an Australian population-based study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 14(12):1581–1588 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Agréus L (1993) Socio-economic factors, health care consumption and rating of abdominal symptom severity. A report from The Abdominal Symptom Study. Fam Pract 10(2):152–163 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.van Bommel MJ, Numans ME, de Wit NJ, Stalman WA (2001) Consultations and referrals for dyspepsia in general practice–a one year database survey. Postgrad Med J 77(910):514–518 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Thompson WG, Heaton KW, Smyth GT, Smyth C (2000) Irritable bowel syndrome in general practice: prevalence, characteristics, and referral [see comments]. Gut 46(1):78–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Hungin AP, Rubin GP (2001) Management of dyspepsia across the primary-secondary healthcare interface. Dig Dis 19(3):219–224 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 19.Jones R, Lydeard SE, Hobbs FD, Kenkre JE, Williams EI, Jones SJ et al (1990) Dyspepsia in England and Scotland. Gut 31(4):401–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Engel GL (1980) The clinical application of the biopsychosocial model. Am J Psychiatry 137(5):535–544 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 21.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd (1994) Gastrointestinal tract symptoms and self-reported abuse: a population-based study. Gastroenterology 107(4):1040–1049 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 22.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM (2005) A history of abuse in community subjects with irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia: the role of other psychosocial variables. Digestion 72(2–3):86–96 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Drossman DA, Leserman J, Nachman G, Li ZM, Gluck H, Toomey TC et al (1990) Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med 113(11):828–833 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Nyren O, Tibblin G (1993) Reproducibility and validity of a postal questionnaire. The abdominal symptom study. Scand J Prim Health Care 11(4):252–262 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Agréus L (1993) The abdominal symptom study. An epidemiological survey of gastrointestinal and other abdominal symptoms in the adult population of Östhammar, Sweden [Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis, Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Medicine 434, ISBN 91-554-3176-3]. Uppsala University, Uppsala

- 26.Alander T, Svardsudd K, Johansson SE, Agreus L (2005) Psychological illness is commonly associated with functional gastrointestinal disorders and is important to consider during patient consultation: a population-based study. BMC Med 3(1):8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 27.Agreus L, Svardsudd K, Talley NJ, Jones MP, Tibblin G (2001) Natural history of gastroesophageal reflux disease and functional abdominal disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol 96(10):2905–2914 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Agréus L, Svärdsudd K, Nyrén O, Tibblin G (1995) Irritable bowel syndrome and dyspepsia in the general population: overlap and lack of stability over time. Gastroenterology 109(3):671–680 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 29.Agreus L, Talley NJ, Svardsudd K, Tibblin G, Jones MP (2000) Identifying dyspepsia and irritable bowel syndrome: the value of pain or discomfort, and bowel habit descriptors. Scand J Gastroenterol 35(2):142–151 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Drossman DA (2006) The functional gastrointestinal disorders and the Rome III process. Gastroenterology 130(5):1377–1390 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Finkelhor D (1986) A sourcebook on child sexual abuse. Sage Publications, Beverly Hills

- 32.Dupuy HJ (1984) The Psychological General Well-Being (PGWB) index. In: Wenger NK, Mattson ME, Furberg CF, Elinson J (eds) Assesment of quality of life in clinical trials of cardiovascular therapies. Le Jacq Publishing Inc, NY, pp 170–183 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Stewart AL, Greenfield S, Hays RD, Wells K, Rogers WH, Berry SD et al (1989) Functional status and well-being of patients with chronic conditions. Results from the Medical Outcomes Study. JAMA 262(7):907–913 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP (1983) The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 67(6):361–370 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 35.Herrmann C (1997) International experiences with the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale–a review of validation data and clinical results. J Psychosom Res 42(1):17–41 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Johnston M, Pollard B, Hennessey P (2000) Construct validation of the hospital anxiety and depression scale with clinical populations. J Psychosom Res 48(6):579–584 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Bagley S, White H, Golomb B (2001) Logistic regression in the medical literature: Standards for use and reporting, with particular attention to one medical domain. J Clin Epidemiol 54:979–985 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 38.Stata Statistical Software (2006) Release 9.2 ed. College Station, Stata Corporation, TX

- 39.Talley N, Stanghellini V, Heading R, Koch K, Malagelada J, Tytgat G (1999) Functional gastroduodenal disorders: A working team report for the ROME II consensus on functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gut 45(Suppl 11):1137–1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 40.Leserman J, Drossman DA, Li Z, Toomey TC, Nachman G, Glogau L (1996) Sexual and physical abuse history in gastroenterology practice: how types of abuse impact health status. Psychosom Med 58(1):4–15 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Perona M, Benasayag R, Perello A, Santos J, Zarate N, Zarate P et al (2005) Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in women who report domestic violence to the police. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 3(5):436–441 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 42.Drossman DA, Talley NJ, Leserman J, Olden KW, Barreiro MA (1995) Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness. Review and recommendations. Ann Intern Med 123(10):782–794 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Felitti VJ (1991) Long-term medical consequences of incest, rape, and molestation. South Med J 84(3):328–331 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Longstreth GF (1994) Irritable bowel syndrome and chronic pelvic pain. Obstet Gynecol Surv 49(7):505–507 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Leserman J (2005) Sexual abuse history: prevalence, health effects, mediators, and psychological treatment. Psychosom Med 67(6):906–915 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Reilly J, Baker GA, Rhodes J, Salmon P (1999) The association of sexual and physical abuse with somatization: characteristics of patients presenting with irritable bowel syndrome and non-epileptic attack disorder. Psychol Med 29(2):399–406 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 47.Linton SJ (1997) A population-based study of the relationship between sexual abuse and back pain: establishing a link. Pain 73(1):47–53 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Talley NJ, Fung LH, Gilligan IJ, McNeil D, Piper DW (1986) Association of anxiety, neuroticism, and depression with dyspepsia of unknown cause. A case-control study. Gastroenterology 90(4):886–892 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M (1998) Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut 42(1):47–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Hobbis IC, Turpin G, Read NW (2002) A re-examination of the relationship between abuse experience and functional bowel disorders. Scand J Gastroenterol 37(4):423–430 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Jones MP, Dilley JB, Drossman D, Crowell MD (2006) Brain-gut connections in functional GI disorders: anatomic and physiologic relationships. Neurogastroenterol Motil 18(2):91–103 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Bouin M, Meunier P, Riberdy-Poitras M, Poitras P (2001) Pain hypersensitivity in patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders: a gastrointestinal-specific defect or a general systemic condition? Dig Dis Sci 46(11):2542–2548 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Newman MG, Clayton L, Zuellig A, Cashman L, Arnow B, Dea R et al (2000) The relationship of childhood sexual abuse and depression with somatic symptoms and medical utilization. Psychol Med 30(5):1063–1077 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Creed F, Guthrie E, Ratcliffe J, Fernandes L, Rigby C, Tomenson B et al (2005) Reported sexual abuse predicts impaired functioning but a good response to psychological treatments in patients with severe irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med 67(3):490–499 [DOI] [PubMed]