Abstract

The endangered mountain pygmy possum is the only Australian marsupial that hibernates under snow cover. Most of its alpine habitat was burnt by a rare fire in 2003, and habitat loss and disturbance have also occurred owing to ski resort development. Here we show that there has been a rapid loss of genetic variation following habitat loss associated with resort development, but no detectable loss of alleles or decrease in heterozygosity following the fire.

Keywords: genetic variation, Burramys, endangered, inbreeding

1. Introduction

Endangered animals are threatened by the destruction of habitat, leading to a decrease in food and shelter, fragmented populations, and an increase in foreign predators and competitors. In addition, endangered animals are threatened by ecological catastrophes that result in local extinction and/or by environmental changes that make environments unsuitable (Reed 2004). Both catastrophes and fragmentation can cause local extinction directly or indirectly by making populations more susceptible to genetic, demographic and environmental stochasticity (Shaffer 1981). Loss of genetic variation is expected to occur well before extinction (Spielman et al. 2004), but has rarely been documented or linked to specific causes (Frankham 2005).

The mountain pygmy possum (Burramys parvus) is an endangered marsupial restricted to the alpine region of Australia. It inhabits periglacial block streams and block fields, collectively known as boulderfields, and exploits seasonally abundant food in summer. The limited availability of boulderfields, predators and other factors restrict B. parvus numbers; less than 1800 adults remain and their populations are in decline (Heinze et al. 2004). Genetic studies on 2003 samples indicate that populations of B. parvus are genetically fragmented, but within populations levels of gene diversity and mean allele number are high except in a southern population at Mt Buller (Mitrovski et al. 2007).

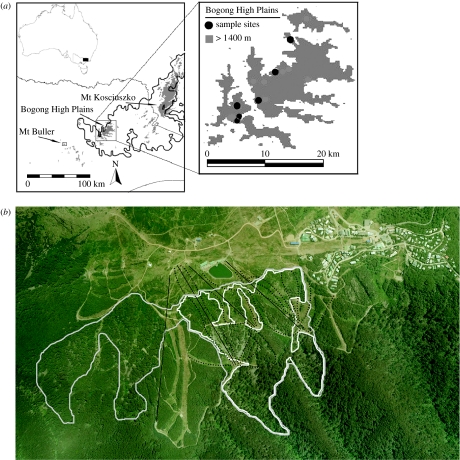

The main threats to B. parvus populations are thought to be human developments and natural catastrophes (D. A. Heinze & I. Mansergh 2004, personal communication). Boulderfields above the snowline represent ideal areas for the development of ski fields. Between 1980 and 2002, resort activities at Mt Buller have disturbed or eliminated an estimated 80% of this habitat at the main site where B. parvus are found (Federation; table 1; figure 1). This loss is apparent from aerial photographs taken over the last 25 years and has occurred owing to the development of ski runs and supporting infrastructure. Only one other area inhabited by B. parvus at Mt Buller (Fanny's Finish) is known to support a persistent population; this site has so far escaped damage from development, but has poor quality habitat (see electronic supplementary material) that only supports a small population. Ski resort developments have also been made in two other B. parvus sites (East and West Higginbotham) in the Bogong High Plains of Victoria.

Table 1.

Habitat area (ha), fire damage (%) and anthropogenic related habitat loss (%) in populations of B. parvus

| habitat area (ha) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| population | 1980 | 2002 | 2004 | % loss/modification from human activities | % loss from fire |

| Bogong High Plains | |||||

| West Higginbotham | 34.3 | 30.87 | 30.87 | 10 | 62 |

| Mt Loch | 27.7 | 27.44 | 27 | 2 | 44 |

| Mt McKay | 21 | 20.58 | 20.58 | 0 | 87 |

| Timms Spur | 15.6 | 14.82 | 14.82 | 5 | 35 |

| Bundara | 15 | 15 | 15 | 0 | 0 |

| East Higginbotham | 30 | 24 | 24 | 20 | 0 |

| Mt Buller populations | |||||

| Federation | 90.48 | 18.09 | 18.09 | 80 | 0 |

| Fanny's Finish | 77.32 | 76.55 | 76.55 | 1 | 0 |

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of Burramys parvus and area burnt in the 2003 fires (inset; location of populations sampled from the Bogong High Plains). (b) Aerial photograph of Federation and Fanny's Finish areas at Mt Buller ski resort in 2006 showing the distribution of B. parvus pre-1980 (grey line) when suitable habitat between the populations in this area was continuous, and the current distribution of B. parvus at Federation (white line) when habitat is intersected with ski runs (black dotted lines) and lifts (black lines).

In early 2003, a massive fire in the Victorian alpine area destroyed more than 1 Mha of vegetation including vegetation within B. parvus habitats. At the Mt McKay site, more than 80% of the B. parvus habitat was affected, while there was less damage at three other sites (figure 1; table 1).

These events provide an opportunity to compare the impact of a natural catastrophe with the ongoing impact of human developments on genetic variation in B. parvus populations. Therefore, we have examined changes in levels of genetic variation in populations at Mt Buller with changes in areas affected by the fires and other areas.

2. Material and methods

(a) Sampling, markers and analysis

Hair samples from individual B. parvus for DNA extraction were collected from eight populations across two regions (electronic supplementary material, table S1) between November 1993 and December 2006. Extraction of DNA from hair samples was performed with Chelex (Bio-Rad) and genetic variation was scored at eight microsatellite loci as in Mitrovski et al. (2005).

FSTAT (Goudet 1995) was used to calculate the average number of alleles per locus, allelic richness averaged over loci and FIS. Observed and expected heterozygosities were estimated and deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium determined by exact tests and permutation in GDA v. 1.1 (Lewis & Zaykin 2001). Genetic diversity between samples was compared using paired t-tests after angular transformation. To investigate population differentiation, pairwise measures of FST between populations were calculated and significance determined using FSTAT.

Effective population size (Ne) was estimated with several approaches. Short-term Ne estimates were calculated directly from sex ratio (Caballero 1994) and indirectly from the temporal-based method (Waples 1989; see electronic supplementary material). Two further indirect methods were used to calculate long-term Ne estimates based on infinite allele (IAM; Kimura & Crow 1963) and stepwise mutation models (SMM; Ohta & Kimura 1973). To test for recent reductions in Ne for each population, we ran the program Bottleneck (Cornuet & Luikart 1996) under a two-phased model (TPM) and reported the results of a Wilcoxon signed-rank test.

(b) Habitat loss estimation

The distribution and area of preferred habitat was mapped using aerial photographs incorporated into a GIS system (ArcGIS v. 9.0), coupled with habitat verification in the field (ground-truthing) most recently in 2006 at Mt Buller and in 2003 on the Bogong High Plains (see electronic supplementary material).

3. Results

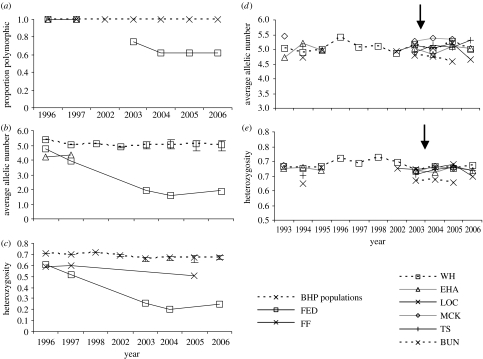

To test whether genetic variation in populations was influenced by habitat changes at Mt Buller, we scored variation at eight microsatellite loci on more than 1500 individuals over 9–12 years (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Levels of genetic variation at Federation in 1996 were similar to those in other B. parvus populations around this time (figure 2), although evidence consistent with inbreeding was found; deviations from Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium due to a deficiency of heterozygotes were detected in five out of the eight loci (electronic supplementary material, table S1). After 1996, there was a rapid decline in expected heterozygosity at Federation to approximately 0.2 by 2004. Changes in expected heterozygosity between samples from 1996 to 1997 and from 1997 to 2004 were significant by paired t-tests (1996–1997, t=2.76, d.f.=7, p=0.014; 1997–2004, t=4.04, d.f.=7, p=0.002). This rapid decline in genetic variation was also evident from the loss of alleles (1996–1997, t=2.49, d.f.=7, p=0.024; 1997–2004, t=5.01, d.f.=7, p<0.001) and from changes in the proportion of polymorphic loci (figure 2). Levels of genetic variation fell to approximately one-third of 1996 levels. This decline corresponded to a marked drop in census population size at Federation, particularly in male numbers (table 2). By contrast, only a small and non-significant decrease in heterozygosity and allelic richness was evident at Fanny's Finish only 1 km from Federation (figure 2), although there was evidence of an excess of homozygotes at this site (electronic supplementary material, table S1). Genetic differentiation was detected between all populations as indicated by significant pairwise FST estimates (range 0.013–0.430), except between Federation and Fanny's Finish (range 0–0.012). However, capture-mark-recapture data from 1996 to 2007 indicate that these populations are likely to be isolated with no dispersal events detected between populations (D. A. Heinze 2006, unpublished data). Genetic differentiation was not detected between samples from the same site.

Figure 2.

(a–c) Temporal changes in proportion of polymorphic loci, mean allelic richness and mean expected heterozygosity from populations of B. parvus in the central region (dotted lines with the range of values indicated by error bars) and populations from Mt Buller (solid lines). Crosses indicate populations from the central region, open squares represent the Federation site and open triangles represent the Fanny's Finish population. (d,e) Temporal changes in mean allelic richness and expected heterozygosity from populations of B. parvus in the central region. Dotted lines indicate populations that were not affected by fire, whereas solid lines indicate populations potentially affected by fire. Arrows indicate when the alpine fire occurred.

Table 2.

Effective population size estimates of B. parvus populations. (n, number of individuals sampled; Nc, adult census estimates; Ne (dir), direct estimates based on sex ratio; Ne (temporal), temporal-based estimates; Ne (IAM) and Ne (SMM) effective population size calculated under the assumptions of an infinite allele model (IAM) and stepwise mutation model (SMM), using mutation rates of 10−3; Ne/Nc, effective population size to census size ratio.)

| population | year | n | sex ratio (male : female) | Nc | Ne(dir) | Ne(temporal) | Ne(IAM) | Ne(SMM) | Ne /Nc | bottleneckTPM (p value) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| West Higginbotham | 1993 | 54 | 1 : 4 | 108 | 70 | 542 | 1255 | 0.64 | 0.191 | |

| 2004 | 24 | 1 : 3 | 48 | 36 | 62.2 | 534 | 1230 | 0.75 | 0.527 | |

| East Higginbotham | 1993 | 26 | 1 : 4 | 52 | 32 | 519 | 1181 | 0.64 | 0.156 | |

| 2004 | 31 | 1 : 3 | 62 | 48 | 30.1 | 489 | 1091 | 0.75 | 0.527 | |

| Mt Loch | 1995 | 15 | 1 : 3 | ∼120 | 90 | 531 | 1218 | 0.75 | 0.320 | |

| 2004 | 140 | 1 : 8 | 280 | 110 | 53.7 | 532 | 1224 | 0.4 | 0.321 | |

| Bundara | 1994 | 42 | 1 : 4 | 84 | 54 | 414 | 881 | 0.64 | 0.578 | |

| 2004 | 93 | 1 : 5 | 102 | 57 | ∞ | 446 | 970 | 0.75 | 0.578 | |

| Mt McKay | 1993 | 28 | 1 : 5 | 56 | 30 | 550 | 1280 | 0.56 | 0.191 | |

| 2004 | 18 | 1 : 4 | 36 | 23 | 23.3 | 536 | 1235 | 0.64 | 0.421 | |

| Timms Spur | 1994 | 68 | 1 : 4 | 136 | 87 | 471 | 1040 | 0.75 | 0.769 | |

| 2004 | 52 | 1 : 3 | 104 | 78 | 75.3 | 510 | 1155 | 0.89 | 0.527 | |

| Federation | 1996 | 25 | 1 : 12 | 170 | 48 | 392 | 824 | 0.28 | 0.990 | |

| 2004 | 15 | 1 : 5 | 38 | 20 | 9.4 | 65 | 198 | 0.56 | 0.109 | |

| Fanny's Finish | 1996 | 11 | 1 : 12 | 36 | 11 | 359 | 743 | 0.28 | 0.312 | |

| 2004 | 6 | 1 : 4 | 12 | 7 | 303.2 | 258 | 515 | 0.64 | 0.843 |

In populations of B. parvus from the Bogong High Plains that included burnt sites, there was no evidence that levels of genetic variation changed across years, with expected heterozygosities all greater than 0.62 (figure 2). Furthermore, trapping rates and animal captures were consistent with those obtained during 1984 to 2003. There was no consistent reduction in population size between the pre-fire and post-fire samples 2005 (table 2). Changes in population size estimated from genetic data ranged from an increase or a decrease in size of less than 10%.

Effective population size estimates for Buller populations were small and similar in most cases (table 2). Both direct and indirect short-term estimates were low but varied among methods and temporally. Changes in effective population size for all populations of B. parvus were best described from long-term estimates using the IAM and SMM methods (Kimura & Crow 1963; Ohta & Kimura 1973). These indicated a decrease of 77% in Federation under the IAM or 67% under the SMM, compared with 30% under both models at the Fanny's Finish site (table 2). Loss of genetic variability in the Mt Buller site is likely to reflect a sharp drop in population size compared with other populations. No recent bottleneck signature was detected in any population under the TPM (table 2).

4. Discussion

This is the most rapid loss of genetic diversity in a mammal ever documented. By comparison, in a longitudinal study of a Scandinavian wolf population (Flagstad et al. 2003), 30% of gene diversity was lost in just over a century. The rapid loss of genetic diversity in B. parvus is likely to reduce evolutionary potential and reproductive fitness, as well as elevate extinction risk (Spielman et al. 2004). Burramys populations are particularly susceptible to extinction from loss of genetic variation due to their polygynous mating system. Owing to matriarchal defence of optimal habitats (normally the higher altitudes of boulderfields), males are forced to lower suboptimal habitats that contain fewer hibernacula and food resources, and have greater levels of temperature variability. Habitat fragmentation is likely to decrease food availability and increase predator risk in these areas, skewing the sex ratio. During the 2005/2006 season, the sex ratio at Federation was estimated from captured animals as 1 male : 22 females; no males were captured, but some females contained pouch young suggesting a minimum of one breeding male. This skewed sex ratio will decrease the effective population size well below census size. Moreover, asynchronous breeding behaviour was observed for the first time in this species. Second litters were detected in several females late in the season which are likely to be lethal for both the mother and young during hibernation because possums have insufficient time to accumulate adequate fat reserves (D. A. Heinze 2006, unpublished data). This phenomenon, the first time detected at Federation, may reflect deleterious genes influencing viability of the first litter. By contrast, the large drop in census estimates at Fanny's Finish is likely to be a recent occurrence because genetic diversity is maintained. This may reflect recent unfavourable environmental conditions and poor quality habitat and is supported by a lack of dispersal events between Federation and Fanny's Finish in the last 10 years (D. A. Heinze 2006, unpublished data).

In comparison, populations burnt by the unusual fire event were relatively unaffected and census estimates were at pre-fire levels within a season. No loss of rare alleles was detected, so that genetic variation was maintained (figure 2). The genetic data suggest that rare natural catastrophes like the alpine fires do not represent the main threat to B. parvus and perhaps other endangered mammals.

Encroachment of development on Burramys habitat represents an important long-term threat. Ski field developments continue in the alpine area and B. parvus habitat is threatened at several resorts. The data presented here suggest that such developments should proceed in a sensitive manner that preserves all Burramys habitat intact. Recovery of the Federation population will take some time even if the boulderfield habitat is restored. Because inbreeding and loss of adaptive potential threaten long-term persistence of populations (Saccheri et al. 1998; Frankham 2005), an immediate goal at Mt Buller should be to increase levels of genetic variation in populations. A target for long-term viability of Burramys populations is a heterozygosity of 0.65 or higher. Individuals from other populations will need to be introduced to achieve this target.

Acknowledgments

This work was carried out with ethics approval (AEC04/4(BG)).

We thank Warwick Papst, DSE Victoria and Alex Olejniczak for assistance with sampling, Glen Johnson for project support and Ian Mansergh for advice and comments. This work was funded by the Holsworth Wildlife Research Fund, Royal Society of Victoria, DSE Victoria, David Hay Memorial Award, National Heritage Trust and the Australian Research Council (ARC) through their Special Research Centre programme. This work was carried out while A.A.H. held an ARC Federation Fellowship.

Supplementary Material

Sampling, habitat loss estimation, microsatellite genotyping and analysis

Population statistics for B. parvus screened with eight microsatellite loci

References

- Caballero A. Developments in the prediction of effective population size. Heredity. 1994;73:657–679. doi: 10.1038/hdy.1994.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornuet J.M, Luikart G. Description and power analysis of two tests for detecting recent population bottlenecks from allele frequency data. Genetics. 1996;144:2001–2014. doi: 10.1093/genetics/144.4.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flagstad O, Walker C.W, Vila C, Sundqvist A.-K, Fernholm B, Hufthammer A.K, Wiig Ø, Koyola I, Ellegren H. Two centuries of the Scandinavian wolf population: patterns of genetic variability and migration during an era of dramatic decline. Mol. Ecol. 2003;12:869–880. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-294x.2003.01784.x. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294X.2003.01784.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frankham R. Genetics and extinction. Biol. Conserv. 2005;126:131–140. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2005.05.002 [Google Scholar]

- Goudet J. FSTAT (version 1.2): a computer program to calculate F-statistics. J. Hered. 1995;86:485–486. [Google Scholar]

- Heinze D.A, Broome L, Mansergh I. A review of the ecology and conservation of the mountain pygmy-possum Burramys parvus. In: Goldingay R, Jackson S, editors. The biology of the Australian possums and gliding possums. Surrey Beatty & Sons; Chipping Norton, UK: 2004. pp. 254–267. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M, Crow J.F. Measurement of effective population number. Evolution. 1963;17:279–288. doi:10.2307/2406157 [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, O. P. & Zaykin, D. 2001 Genetic Data Analysis: a computer program for the analysis of allelic data. See http://hydrodictyon.eeb.uconn.edu/people/plewis/software.php

- Mitrovski P, Heinze D.A, Guthridge K, Weeks A.R. Isolation and characterization of microsatellite loci from the Australian endemic mountain pygmy-possum, Burramys parvus broom. Mol. Ecol. Notes. 2005;5:395–397. doi:10.1111/j.1471-8286.2005.00939.x [Google Scholar]

- Mitrovski P, Heinze D.A, Broome L, Hoffmann A.A, Weeks A.R. High levels of variation despite genetic fragmentation in populations of the endangered mountain pygmy-possum, Burramys parvus, in alpine Australia. Mol. Ecol. 2007;16:75–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03125.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03125.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohta T, Kimura M. Model of mutation appropriate to estimate number of electrophoretically detectable alleles in a finite population. Genet. Res. 1973;22:201–204. doi: 10.1017/s0016672300012994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D.H. Extinction risk in fragmented habitats. Anim. Conserv. 2004;7:181–191. doi:10.1017/S1367943004001313 [Google Scholar]

- Saccheri I, Kuussaari M, Kankare M, Vikman P, Fortelius W, Hanski I. Inbreeding and extinction in a butterfly metapopulation. Nature. 1998;392:491–494. doi:10.1038/33136 [Google Scholar]

- Shaffer M.L. Minimum population sizes for species conservation. Bioscience. 1981;31:131–134. doi:10.2307/1308256 [Google Scholar]

- Spielman D, Brook B.W, Frankham R. Most species are not driven to extinction before genetic factors impact them. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:15 261–15 264. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403809101. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403809101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waples R.S. A generalized-approach for estimating effective population-size from temporal changes in allele frequency. Genetics. 1989;121:379–391. doi: 10.1093/genetics/121.2.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Sampling, habitat loss estimation, microsatellite genotyping and analysis

Population statistics for B. parvus screened with eight microsatellite loci