Abstract

Objective To evaluate the effectiveness of a voluntary sector based befriending scheme in improving psychological wellbeing and quality of life for family carers of people with dementia.

Design Single blind randomised controlled trial.

Setting Community settings in East Anglia and London.

Participants 236 family carers of people with primary progressive dementia.

Intervention Contact with a befriender facilitator and offer of match with a trained lay volunteer befriender compared with no befriender facilitator contact; all participants continued to receive “usual care.”

Main outcome measures Carers’ mood (hospital anxiety and depression scale—depression) and health related quality of life (EuroQoL) at 15 months post-randomisation.

Results The intention to treat analysis showed no benefit for the intervention “access to a befriender facilitator” on the primary outcome measure or on any of the secondary outcome measures.

Conclusions In common with many carers’ services, befriending schemes are not taken up by all carers, and providing access to a befriending scheme is not effective in improving wellbeing.

Trial registration Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN08130075.

Introduction

Providing care for a person with dementia is stressful and demanding, and carers of people with dementia have poorer physical and mental health than do carers of people with other conditions.1 Carers who find caring a stressful experience are at higher risk of mortality than are non-carers.2 Social aspects of burden include loss of relationship with the recipient of care and reduced social network owing to stigma or lack of opportunities to socialise. In addition, chronic illness can result in family conflicts that reduce the available emotional support, and family and friends may “distance” themselves physically or psychologically from carers. Carers can feel lonely, and loneliness has been associated with increased mortality and physical and psychiatric morbidity.

In the United Kingdom, one to one social support is commonly provided through voluntary sector based befriending services. Britain has a long tradition of voluntary action, and the emphasis on partnership in recent government policies has given voluntary, community, and users’ organisations a more central role in the delivery of services.3 4

We could identify only one published trial of befriending for family carers of people with dementia; it evaluated the provision of a short term (eight week) peer support intervention that showed no significant impact.5 We may anticipate that friendships take time to evolve, and therefore befriending should be evaluated over the long term. In this paper, we describe the clinical outcomes of the befriending and costs of caring (BECCA) multi-site randomised controlled trial of a long term voluntary sector based befriending intervention.6

Methods

Design

We used a randomised controlled trial to compare usual care plus a social support intervention (access to a befriender facilitator) with control (usual care) for carers of people with dementia. We collected data at baseline and at 6, 15, and 24 months after randomisation; we identified the 15 month data as the main outcome data at the start of the trial, as this time point balanced the aims of maximising the likelihood that intervention carers would have experienced the target duration of at least six months’ befriending and minimising the proportion of withdrawals from the research interviews.

Participants

Participants were family carers of a community dwelling recipient of care with a primary progressive dementia. We recruited carers between April 2002 and July 2004 in community settings in the East Anglian counties of Norfolk and Suffolk and in the London Borough of Havering. Carers were eligible to participate if they were spending 20 hours or more a week on care tasks. We excluded carers with pronounced congenital or acquired cognitive impairment, as well as those with terminal illness and carers of people in permanent residential, nursing, or long stay hospital accommodation. We obtained informed consent from carers but not from the people with dementia, as the data collection and intervention were carer focused.

Baseline assessments and randomisation procedures

Researchers did baseline assessments before randomisation. Interviews generally took place in carers’ own homes. Baseline measures included demographics; service use; carers’ wellbeing and health related quality of life; and carers’ burden, relational deprivation, loneliness, and perceived social support. The trial statistician (LS) drew up randomisation lists before the start of recruitment, and the research administrator (blind to information on participants’ characteristics) held these. We block randomised participants by using a concealed block length of six and two stratifications—kinship of the carer to the person with dementia (vertical: daughter, son v horizontal: spouse, sibling) and density of population (urban: >10 000 people/km2 v rural: <10 000 people/km2). Team members involved in carers’ consent and interviews were not involved in the randomisation process. We could not blind trial participants to group allocation because of the nature of the intervention. However, interviewers were independent of the befriending services, and we used well validated self report inventories for measuring outcomes.

Intervention and control conditions

All participants and recipients of care received usual care as provided in their area by health, social, or voluntary services. Typical services included community psychiatric services, day hospitals, day centres, home care or personal care, respite care, and carers’ information or support groups. We sent all participants information on local services for carers.

We offered carers in the intervention group contact with a local befriending scheme set up specifically for the research trial.6 BECCA befriending schemes were based in voluntary organisations with experience of supporting befriending volunteers and were organised and administered separately from the research interviews. Each scheme was coordinated by a befriender facilitator, who had responsibility for the recruitment, screening, training, matching, and ongoing support of befriending volunteers. Befriending volunteers had the role of providing emotional support for their matched carers through companionship and conversation and being a “listening ear.” We also permitted informational support or “signposting” in limited, appropriate circumstances. We explicitly excluded advice giving and practical caring tasks that would otherwise be carried out by a paid worker. The volunteers followed good practice guidelines for volunteer support, including guidelines for those working with potentially vulnerable people.7 8 Volunteers participated in 12 hours of training, including boundaries of the role, listening skills, carers’ problems, health and safety risk assessment, and confidentiality. The befriender facilitators coordinated befriender-carer matches, supported introductions, and carried out periodic checks. We expected that befriending contact would be weekly home visits for at least six months.

End points

The primary end point was carers’ wellbeing, as measured by the seven item hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS) depression scale.9 Secondary end points were health related quality of life (quality adjusted life years and the EuroQol visual analogue scale),10 wellbeing as measured by the HADS anxiety scale,9 positive affectivity (positive and negative affectivity scale, PANAS),11 loneliness,12 and perceived social support (multidimensional scale of perceived social support, MSPSS).13 14 We also recorded institutionalisation and death of the person with dementia.

Sample size calculation

We based sample size calculations on the HADS and the effect size seen in befriending interventions with different client groups (that is, 0.42 to 0.45), as no directly comparable trials were available at the time of planning.15 16 Using Nquery,17 and assuming a normal distribution, we calculated that we needed 150 carers in each group to achieve 90% power at the 5% significance level (two tailed), assuming a post-randomisation dropout rate of 20%. As the dropout rate at six months was lower than anticipated, we were able to reduce our randomisation target to 235 carers while maintaining adequate precision and power.

Statistical methods

We assumed that the HADS, PANAS, MSPSS, and loneliness scores followed a normal distribution, on the basis of summary statistics and plots. We initially used a two sample t test with pooled variance to test for a difference in means between groups. We used a general linear model to compare groups while adjusting for baseline scores and by stratification variables (that is, kinship and population density). We constructed confidence intervals for unadjusted and adjusted (least squares) mean differences. We used the log-rank test to test for a difference in median time to institutionalisation between the two groups.

We did accuracy checks and missing data analyses. Psychometric data were generally complete (missing data less than 5%); more data were missing for baseline interviews than for follow-up interviews (excluding withdrawals). Where individual data points were missing within a scale, we imputed data by using scale/subscale means.

We did primary and secondary analyses on a modified intention to treat basis, analysing carers according to the group to which they were randomised. We did two pre-planned subgroup analyses on the primary endpoint. We did a per protocol analysis including those carers who received their group intervention as described in the protocol—that is, at least six months of befriending contact in the intervention group and no befriending contact in the control group. We also did a subgroup analysis including only carers who were spouses of the people with dementia. We used SPSS version 12.0.2 and SAS version 8.2 to analyse data.

Results

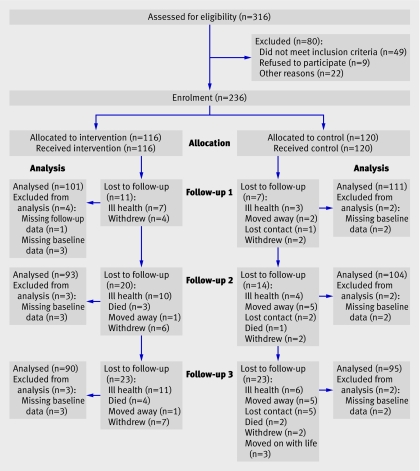

The figure shows the flow of participants through the study. We received expressions of interest from 316 potential participants, of whom 49 did not meet the eligibility criteria. The most common reasons for exclusion were that the person with dementia lived in permanent care or had already died. Other reasons were ill health of the carer and the care recipient having an illness other than a primary progressive dementia. Overall, 236 carers met the study entry criteria and were randomised into the trial, 116 to the intervention group and 120 to the control group. Administrative error led to three control carers being put in contact with a befriender facilitator. They were offered the intervention but under the intention to treat strategy were analysed as control.

Flow of participants through study

Table 1 presents baseline data on demographic, psychometric, and service use variables. Most participants were white, female, above retirement age, and living with and usually married to the person with dementia. Almost all were providing daily assistance. The mean age of carers was 68 (range 36-91) years, and the mean duration of caring was just under four years. The mean age of the people with dementia was older, at 78 years. One in five (17%) carers reached case levels of depression (HADS depression score ≥11). As can be seen from table 1, baseline comparability between the groups was good.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 236 carers randomised to intervention and control. Values are numbers (percentages) unless stated otherwise

| Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=120) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Value | No | Value | |||

| Carers’ characteristics | ||||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 116 | 68.4 (11.3) | 120 | 67.6 (11.6) | ||

| Female | 116 | 76 (66) | 120 | 76 (63) | ||

| Ethnicity: white | 116 | 116 (100) | 118 | 116 (98) | ||

| Kinship: spouse | 116 | 76 (66) | 120 | 83 (69) | ||

| Urban location | 116 | 71 (61) | 120 | 75 (63) | ||

| Cohabiting | 116 | 99 (85) | 120 | 105 (88) | ||

| Daily assistance | 114 | 110 (97) | 120 | 116 (97) | ||

| 24 hours/day “on duty” | 105 | 67 (64) | 111 | 72 (65) | ||

| Retired | 115 | 78 (68) | 120 | 80 (67) | ||

| Mean (SD) years caring | 114 | 3.9 (7.7) | 118 | 3.7 (3.5) | ||

| Mean (SD) HADS depression score* | 113 | 6.7 (3.6) | 118 | 6.9 (3.9) | ||

| Mean (SD) EuroQoL VAS score* | 112 | 74.0 (16.8) | 114 | 73.1 (18.1) | ||

| Mean SD HADS anxiety score* | 113 | 7.5 (4.5) | 118 | 7.9 (4.6) | ||

| Mean (SD) positive affect (PANAS) score* | 108 | 31.03 (7.5) | 111 | 31.7 (7.7) | ||

| Mean (SD) loneliness score* | 112 | 2.00 (2.2) | 115 | 2.2 (2.2) | ||

| Mean (SD) perceived social support (MSPSS) score* | 113 | 44.0 (9.9) | 116 | 44.4 (9.1) | ||

| Support | ||||||

| Regular family/friend support | 109 | 44 (40) | 117 | 54 (46) | ||

| No family/friend support | 109 | 39 (36) | 117 | 30 (26) | ||

| Carers’ services | 113 | 71 (63) | 118 | 67 (57) | ||

| People with dementia’s characteristics and service use | ||||||

| Mean (SD) age (years) | 116 | 78.6 (8.9) | 120 | 77.8 (8.5) | ||

| Day care | 114 | 58 (51) | 120 | 59 (49) | ||

| Home care | 115 | 29 (25) | 120 | 32 (27) | ||

| Respite stays | 115 | 27 (23) | 117 | 29 (25) | ||

HADS=hospital anxiety and depression scale; MSPSS=multidimensional scale of perceived social support; PANAS=positive and negative affectivity scale; VAS=visual analogue scale.

*Higher scores indicate greater depression, perceived good health, anxiety, positive affect, loneliness, and perceived social support.

Overall retention was good. At 24 months, 190 (81%) of the original 236 carers were still participating in the study. The withdrawal rate was almost identical in the two groups. The main reason for loss was carers’ health, and six carers died. All carers who were followed up were included in the analysis, with the exception of three intervention carers and two control carers who had missing HADS data at baseline.

Table 2 shows the analysis of the primary end point. We found no evidence for a benefit of intervention over control at any time point, either for the unadjusted analysis or when we repeated analyses by using a general linear model with baseline scores and the stratification variables as covariates. Table 3 shows the analyses of the secondary end points. Again, we found no evidence of any significant differences between groups for any of the variables considered at any time point.

Table 2.

Primary endpoints at 6, 15, and 24 months post-randomisation (HADS depression scale)

| Time point | Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=120) | Unadjusted analysis* | Adjusted analysis† | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Mean (SD) | No | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95%CI) | P value | Least squares mean difference (95%CI) | P value | ||||

| 6 months | 104 | 6.03 (3.63) | 113 | 5.84 (3.96) | −0.193 (−1.21 to 0.83) | 0.709 | −0.485 (−1.23 to 0.26) | 0.201 | |||

| 15 months | 96 | 6.03 (4.00) | 106 | 6.71 (4.18) | 0.676 (−0.46 to 1.81) | 0.241 | 0.468 (−0.50 to 1.44) | 0.342 | |||

| 24 months | 93 | 6.25 (4.12) | 97 | 6.35 (4.59) | 0.103 (−1.15 to 1.35) | 0.871 | −0.207 (−1.32 to 0.90) | 0.713 | |||

HADS=hospital anxiety and depression scale.

*Based on two sample t test.

†Based on general linear model adjusting for baseline difference, kinship, and area (that is, stratification variables).

Table 3.

Secondary endpoints at 6, 15 and 24 months post-randomisation

| Intervention (n=116) | Control (n=120) | Unadjusted analysis* | Adjusted analysis† | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Mean (SD) | No | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95% CI) | P value | Least squares mean difference (95% CI) | P value | |||||||

| EQ5D—visual analogue scale | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 101 | 75.7 (17.0) | 112 | 72.9 (17.7) | −2.81 (−7.51 to 1.89) | 0.240 | −2.06 (−5.51 to 1.38) | 0.239 | ||||||

| 15 months | 95 | 73.8 (18.3) | 106 | 69.9 (18.1) | −3.87 (−8.94 to 1.19) | 0.133 | −2.33 (−6.88 to 2.23) | 0.315 | ||||||

| 24 months | 92 | 72.5 (19.7) | 96 | 68.1 (18.2) | −4.35 (−9.82 to 1.11) | 0.119 | −3.03 (−8.42 to 2.35) | 0.268 | ||||||

| Carers’ quality adjusted life years (QALYs) gained (cumulative) | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 98 | 0.45 (0.14) | 109 | 0.46 (0.15) | 0.00 (−0.035 to 0.043) | 0.83 | 0.00 (−0.01 to 0.01) | 0.69 | ||||||

| 15 months | 88 | 1.00 (0.29) | 99 | 0.99 (0.28) | −0.02 (−0.10 to 0.06) | 0.68 | −0.01 (−0.06 to 0.04) | 0.74 | ||||||

| 24 months | 84 | 1.55 (0.45) | 90 | 1.52 (0.45) | −0.03 (−0.17 to 0.11) | 0.64 | −0.015 (−0.13 to 0.10) | 0.79 | ||||||

| HADS anxiety scale | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 104 | 6.35 (4.46) | 113 | 6.96 (4.37) | 0.610 (−0.57 to 1.79) | 0.311 | 0.218 (−0.43 to 0.97) | 0.568 | ||||||

| 15 months | 96 | 6.55 (4.54) | 106 | 7.55 (4.47) | 1.005 (−0.25 to 2.26) | 0.115 | 0.610 (−0.33 to 1.55) | 0.200 | ||||||

| 24 months | 93 | 6.55 (4.49) | 97 | 6.97 (4.50) | 0.419 (−0.87 to 1.71) | 0.521 | −0.037 (−1.10 to 1.03) | 0.946 | ||||||

| PANAS—positive affect | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 103 | 30.1 (8.13) | 111 | 31.5 (8.31) | 1.40 (−0.82 to 3.62) | 0.214 | 0.922 (−0.98 to 2.83) | 0.341 | ||||||

| 15 months | 96 | 30.5 (8.22) | 106 | 30.5 (8.02) | 0.03 (−2.22 to 2.29) | 0.976 | −0.079 (−2.13 to 1.97) | 0.940 | ||||||

| 24 months | 92 | 30.1 (8.73) | 95 | 31.2 (8.34) | 1.10 (−1.36 to 3.57) | 0.378 | 1.17 (−1.26 to 3.59) | 0.344 | ||||||

| Loneliness | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 104 | 2.06 (2.04) | 112 | 2.21 (2.21) | 0.148 (−0.42 to 0.72) | 0.611 | 0.016 (−0.41 to 0.45) | 0.945 | ||||||

| 15 months | 96 | 2.21 (2.27) | 106 | 2.57 (2.23) | 0.358 (−0.27 to 0.98) | 0.260 | 0.320 (−0.20 to 0.84) | 0.230 | ||||||

| 24 months | 93 | 2.24 (2.39) | 97 | 2.63 (2.30) | 0.392 (−0.28 to 1.06) | 0.251 | 0.173 (−0.37 to 0.72) | 0.529 | ||||||

| Perceived support (MSPSS) | ||||||||||||||

| 6 months | 102 | 45.0 (9.02) | 113 | 45.3 (9.16) | 0.351 (−2.10 to 2.80) | 0.778 | 0.044 (−1.93 to 2.02) | 0.965 | ||||||

| 15 months | 95 | 44.0 (10.19) | 106 | 44.6 (9.88) | 0.606 (−2.19 to 3.40) | 0.669 | −0.756 (−2.89 to 1.38) | 0.486 | ||||||

| 24 months | 92 | 44.5 (10.29) | 97 | 45.4 (9.17) | 0.894 (−1.9 to 3.69) | 0.529 | −0.460 (−2.76 to 1.84) | 0.693 | ||||||

HADS=hospital anxiety and depression scale; MSPSS=multidimensional scale of perceived social support; PANAS=positive and negative affectivity scale.

*Based on two sample t test.

†Based on general linear model adjusting for baseline difference, kinship, and area (that is, stratification variables); in addition, QALYs adjusted for follow-up length.

Table 4 shows the pre-planned subgroup analyses. The per protocol analysis (intervention group carers receiving at least six months’ befriending compared with controls with no contact with a befriender facilitator) indicated a between group difference of borderline significance at the 15 month time point. The spouses-only subgroup analysis resulted in no statistically significant difference between intervention and control.

Table 4.

Subgroup analyses of primary endpoint (HADS depression scale) at 6, 15, and 24 months post-randomisation

| Intervention (n=37) | Control (n=117) | Unadjusted analysis* | Adjusted analysis† | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Mean (SD) | No | Mean (SD) | Mean difference (95%CI) | P value | Least squares mean difference (95%CI) | P value | |||||

| Per protocol analysis | ||||||||||||

| 6 months | 34 | 5.47 (3.37) | 111 | 5.86 (3.97) | 0.383 (−1.11 to 1.87) | 0.612 | 0.107 (−1.00 to 1.21) | 0.848 | ||||

| 15 months | 31 | 5.06 (3.45) | 104 | 6.75 (4.21) | 1.684 (0.04 to 3.32) | 0.044 | 1.377 (−0.09 to 2.84) | 0.066 | ||||

| 24 months | 30 | 4.97 (4.11) | 95 | 6.37 (4.63) | 1.402 (−0.47 to 3.27) | 0.140 | 1.038 (−0.63 to 2.71) | 0.220 | ||||

| Spouse carers only | ||||||||||||

| 6 months | 68 | 6.36 (4.46) | 78 | 6.50 (4.38) | 0.143 (−1.31 to 1.59) | 0.846 | −0.332 (−1.24 to 0.57) | 0.469 | ||||

| 15 months | 60 | 6.78 (4.48) | 73 | 7.01 (4.39) | 0.233 (−1.29 to 1.76) | 0.764 | −0.110 (−1.24 to 1.02) | 0.848 | ||||

| 24 months | 57 | 6.56 (4.46) | 69 | 7.09 (4.72) | 0.523 (−1.11 to 2.15) | 0.527 | 0.146 (−1.15 to 1.47) | 0.824 | ||||

HADS=hospital anxiety and depression scale.

*Based on two sample t test.

†Based on general linear model adjusting for baseline difference, kinship, and area (that is, stratification variables).

When we looked at time to institutionalisation with death or end of study as a censor when these occurred before institutionalisation, we found no difference between groups (intervention median 728 days, control median 707 days; P=0.673, log rank test).

Discussion

The BECCA trial evaluated the impact of access to a voluntary sector based befriender facilitator for family carers of people with dementia. We found no evidence for a benefit of “access to a befriender facilitator” on primary or secondary outcome measures. This negative finding may be due to the limited uptake of the befriending intervention and to the higher than anticipated levels of family support and contact with carers’ support services. Where carers of spouses have local family, interventions to mobilise family resources are known both to reduce the carer’s depression and to delay institutionalisation of the person with dementia.18 In the BECCA trial, befriending was more likely to be used by carers with no local family and little contact with family, friends, or neighbours.19

Generalisability of results

The external validity of this pragmatic trial is high, and the level of psychological morbidity in carers is in keeping with other studies of carers of people with dementia.20 21 Two aspects limit its generalisability: lack of ethnic mix and wide geographical spread. Participants were almost exclusively white British, and we can therefore draw no conclusions on the applicability or effectiveness of the befriending intervention for other ethnic or cultural groups. The befriending schemes were set up specifically for the trial and, although local, covered a wider geographical area than would be typical for the host organisations. The challenge of travel in rural areas led to decisions to alternate face to face meetings with telephone befriending or to meet fortnightly rather than weekly.

Limitations of the study

At 48%, the proportion of carers requesting a match with a befriender is similar to the level of participation in other trials of psychosocial interventions involving carers. However, only 37 (32%) intervention carers received the intended minimum duration of match (six months) before the 15 month follow-up, of whom five withdrew from the follow-up and one died. Furthermore, the intended “dose” of befriending (one hour a week) was rarely achieved, as many carers were too busy to set aside that amount of time on such a regular and long term basis. The difference between intervention and control conditions was narrow, given that the research interviewers were frequently experienced as “a good person to talk to” and befriending support was at a low level.

Conclusion

Access to a befriender facilitator is not effective in improving carers’ wellbeing or health related quality of life. Future studies may benefit from selection criteria that maximise the likelihood of uptake of the intervention, although this would reduce the external validity.

What is already known on this topic

Social support is related to mental and physical health

Caring for people with dementia adversely affects social support

Short term peer support for carers of people with dementia is not effective

What this study adds

Long term befriending was taken up by a minority of carers

Access to a befriending service did not improve carers’ wellbeing

We thank Norwich and Norfolk Voluntary Services, Age Concern Suffolk, and Age Concern Havering for hosting the befriending schemes and all the participating carers for their time and support. We also thank Tom Arie for the initial suggestion of evaluating voluntary sector support for carers.

Contributors: GC, IH, MM, FP, DP, SR, and LS were grantholders on the BECCA project, and all contributed to this outcome report. GC had overall responsibility for all aspects of the trial including collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing reports; and the decision to submit articles for publication. MM had overall responsibility for economic evaluation and its reporting. LS did the efficacy analysis. FP held overall responsibility for the befriending intervention. ECFW calculated the QALY outcomes. All authors were involved in reviewing and editing drafts. GC is the guarantor.

Funding: The BECCA trial was commissioned by the NHS R&D Health Technology Assessment (HTA) Programme (project no 99/34/07) after a call for primary research into “support for carers” and the associated peer review process. Volunteers’ out of pocket expenses were provided by Norfolk and Suffolk Social Services and the King’s Lynn and West Norfolk Branch of the Alzheimer’s Society. GC’s time was funded through a Department of Health ad hoc grant to North East London Mental Health Trust. The authors’ work is independent of the funders. Views and opinions expressed in this paper are not necessarily those of the Department of Health.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Eastern Multi Regional Ethics Committee (01/5/48), the five local ethical research committees in Norfolk and Suffolk, and Barking and Havering local ethical research committee.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Ory MG, Hoffman RR, Yee JL, Tennstedt S, Schulz R. Prevalence and impact of caregiving: a detailed comparison between dementia and non-dementia caregivers. Gerontologist 1999;39:177-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schulz R, Beach SR. Caregiving as a risk factor for mortality—the caregiver health effects study. JAMA 1999;282:2215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.HM Treasury. The role of the voluntary and community sector in service delivery: a cross cutting review. London: Stationary Office, 2002 (available at www.hm-treasury.gov.uk/media/8/4/CCRVolSec02.pdf).

- 4.Hawkins S, Restall M. Volunteers across the NHS: improving the patient experience and creating a patient-led service London: Volunteering England, 2006. (available from www.volunteering.org.uk).

- 5.Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Peer support for Alzheimer’s caregivers: is it enough to make a difference? Res Aging 2002;24:171-92. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Charlesworth G, Shepstone L, Wilson E, Thalanany M, Mugford M, Poland F. Does befriending by trained lay workers improve psychological well-being and quality of life for carers of people with dementia (PwD), and at what cost? A randomised controlled trial. Health Technol Assess 2008;12(4):1-78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Centre for Volunteering. Safe and alert: good practice advice on volunteers working with vulnerable clients London: National Centre for Volunteering, 2000

- 8.Scottish Befriending Development Forum. Code of practice: working together to promote good practice in befriending Falkirk: Scottish Befriending Development Forum, 1997

- 9.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1983;67:361-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brooks R. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy 1996;37:53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol 1988;54:1063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stroebe W, Stroebe M, Abakoumkin G, Schut H. The role of loneliness and social support in adjustment to loss: a test of attachment versus stress theory. J Pers Soc Psychol 1996;70:1241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The multidimensional scale of perceived social support. J Pers Assess 1988;52:30-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stanley MA, Beck JG, Zebb BJ. Psychometric properties of the MSPSS in older adults. Aging Ment Health 1998;2:186-93. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lipsey MW, Wilson DB. The efficacy of psychological, educational, and behavioral treatment: confirmation from meta-analysis. Am Psychol 1993;48:1181-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harris T, Brown GW, Robinson R. Befriending as an intervention for chronic depression among women in an inner city. I: randomised controlled trial. Br J Psychiatry 1999;174:219-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Elashoff JD. nQuery advisor version 5.0 user’s guide Cork, Ireland: Statistical Solutions, 2002

- 18.Drentea P, Clay OJ, Roth DL, Mittelman MS. Predictors of improvement in social support: five-year effects of a structured intervention for caregivers of spouses with Alzheimer’s disease. Soc Sci Med 2006;63:957-67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charlesworth G, Tzimoula X, Higgs P, Poland F. Social networks, befriending and support for family carers of people with dementia. Quality Ageing 2007;8:37-44. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cuijpers P. Depressive disorders in caregivers of dementia patients: a systematic review. Aging Ment Health 2005;9:325-30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richards K, Moniz-Cook E, Duggan P, Carr I, Wang M. Defining ‘early dementia’ and monitoring intervention: what measures are useful in family caregiving? Aging Ment Health 2003;7:7-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]