Abstract

Post-translational modification of the p53 family members is key to their regulation. Here we report the phosphorylation of TAp63γ, but not ΔNp63γ, by IκB kinase β (IKKβ). Activation of IKKβ by γ radiation or tumor necrosis factor-α led to increased TAp63γ protein levels in cells. IKKβ, but not its kinase-defective mutant IKKβ-K44A, led to this observed stabilization of TAp63γ. This stabilization of TAp63γ in response to γ radiation was significantly decreased in the absence of IKKβ. Phosphorylation of TAp63γ blocks ubiquitylation and possible degradation of this protein. We postulate that phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ stabilizes the TAp63γ protein by blocking ubiquitylation-dependent degradation of this protein.

p63 is a member of the p53 gene family, which also includes p73 (2, 3). p63 is expressed as multiple isoforms (3). The TAp63 isoforms contain an N-terminal transactivation (TA)2 domain, and the N-terminal truncated isoforms, ΔNp63, lack this TA domain. In addition to expression from these alternative promoters, alternative splicing results in three different isoforms, α, β, and γ, which have different C termini. The TA isoforms of p63 possess transactivation activity on many p53-responsive genes (4). TAp63γ is the most transcriptionally active form of p63 (3). However, for the TAp63α isoform, this activity is repressed through a domain in its own C terminus (5). The ΔNp63 isoforms can function as dominant-negative regulators of the transcriptional activity of the TAp63 isoforms (3, 6–8). p63, unlike p53, is rarely mutated in cancer (9). However, p63 has been shown to be overexpressed in several epithelial cancers (10). The major role for p63 appears to be in the regulation of epithelial development (11, 12). p63 knock-out mice die within days post-birth because of severe defects in limb formation and epithelial stratification. This observation demonstrates a requirement for p63 for the formation of the epidermis and other stratified epithelia. These knock-out mice lack epithelial appendages such as hair follicles and teeth. They also have abnormal craniofacial development. In humans, mutations in p63 are also associated with ectodermal dysplastic syndromes (13–16). A similar abnormal skin phenotype is seen in mice lacking IKKα (17, 18). IKKα along with IKKβ form the catalytic component of the IκB kinase (IKK) complex along with the regulatory IKKγ subunit. Upon activation through various stimuli such as the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα, this complex phosphorylates IκBα (a negative regulator of NFκB) leading to its degradation in a ubiquitin-dependent pathway. This results in the release of NFκB from the cytoplasm into the nucleus where it activates various target genes (19–21). Clearly, both p63 and IKKα play an important role in epidermal formation. More recently it has been shown that TAp63 directly trans-activates IKKα through binding of a p53 consensus sequence on the promoter of IKKα (22). Because of the similarity of phenotypes, it was decided to investigate whether IKK kinases could phosphorylate p63.

Post-translational modification of p53 family members is key to their regulation (23–29). Regulation of p63 through post-translational modification has only more recently been studied (30–33). From these phosphorylation studies it has been suggested that p63 protein levels can change rapidly as a result of post-translational modification. In particular, limited studies of the phosphorylation status of p63 have been reported (2, 32). A recent report demonstrates phosphorylation of TA-p63α in response to DNA damage through treatment with γ radiation (34). In an effort to establish when and how TAp63γ is phosphorylated in cells, we have conducted a series of biochemical and cellular studies. These studies demonstrate that the IKKβ is the major IKK catalytic subunit for TAp63γ phosphorylation but does not phosphorylate ΔNp63γ. In addition, upon activation of IKKβ kinase activity by exposure of cells to γ radiation or tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα), TAp63γ but not ΔNp63γ levels increase rapidly. In addition, upon co-expression of IKKβ, a significant increase in TAp63γ half-life was observed. We postulate that this is because of our observed phosphorylation-dependent inhibition of the ubiquitylation of TAp63γ.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids and Antibodies—The pEGFP-C1-ΔNp63γ plasmid was constructed using ΔNp63γ cDNA (4, 31). The reverse transcription-PCR product of p63γ was isolated with the primers 5′TCCCCCGGGGATGTCCCAGAGCACACAG3′ and 5′CGGGATCCTGGGTACACTGATCGGTT3′ and used to construct pEGFP-C1-TAp63γ. The p63γ sequence was confirmed by sequencing. pEGFP-C1 plasmid was purchased from Invitrogen. IKK constructs were a kind gift from Paul J. Chiao (University of Texas M.D. Anderson Cancer Center). The monoclonal anti-p63 antibody (4A4), which recognizes p63γ and ΔNp63γ, and polyclonal anti-GFP were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology. Monoclonal anti-FLAG and anti-tubulin antibodies were purchased from Sigma.

Buffers—Lysis buffer consisted of 20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.7, 3 mm EDTA, 3 mm EGTA, 250 mm NaCl, 0.5% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 10 mm β-glycerophosphate, 100 μm Na3VO4, 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 mm dithiothreitol.

Immunoprecipitation (IP) Kinase Assay—IP kinase assays were carried out according to the published method (21). Kinase activity was assayed in 20 mm HEPES, 20 mm β-glycerophosphate, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm p-nitrophenyl phosphate, 100 μm Na3VO4, 2 mm dithiothreitol, 10 μm ATP, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, 50 mm NaCl, pH 7.5, and (1–10 μCi) [γ-32P]ATP at 30 °C for 30 min. IP kinase assay substrate proteins were expressed and purified from Escherichia coli (7). FLAG-IKKα and IKKβ immune complexes were isolated as described using anti-FLAG antibody bound to protein G-Sepharose, washed once in kinase buffer containing 3 m urea, and three times with kinase buffer without urea before determining kinase activity. Immunoblotting was done as described previously (7).

Cell Culture—Human embryonic kidney 293 and lung small cell carcinoma H1299 cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 5 units/ml penicillin, and 0.1 mg/ml streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. Human epidermal keratinocytes (HEK) cells were cultured in keratinocyte/SFM medium supplemented with l-glutamine, epidermal growth factor, and bovine pituitary extract (Invitrogen). γ-Irradiated cells were treated with γ radiation (20 Gy) just prior to harvest (48 h post-transfection) at the time points shown, and cell lysates were analyzed on an SDS-8% gel. TNFα-treated cells were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml) prior to harvest (48 h post-transfection) at the time points shown, and cell lysates were also analyzed on an SDS-8% gel. Cells treated with MG132 were treated with 10 μm of the proteasome inhibitor overnight before being harvested.

Purification of His-p63γ and GST-IκBα—His-p63γ wild type and deletion fragments were PCR-cloned into the pET-30a vector and expressed and purified from bacteria using Ni-NTA-agarose beads as described previously (4). The GST-IκBα construct was a kind gift from Dr. M. Hu (GST-IκBα was purified using immunoaffinity columns as described) (7).

Transfection—H1299 cells (60% confluence on a 60-mm plate) or HEK293 (70% confluence on a 60-mm plate) were transfected with 0.5 μg of the parental pEGFP-C1 or pEGFP-C1-p63γ expressing plasmids and 0.5 μg of FLAG-IKKβ by means of TransFectin lipid reagent (Bio-Rad). Cells were harvested 36–48 h post-transfection. Cell lysates were prepared as described (7).

Analysis of p63γ Half-life in Cells—For determination of the exogenous p63γ half-life, H1299 cells were transfected with the pEGFP-C1-TAp63γ plasmid alone or together with the FLAG-IKKβ expression plasmid as described above. 48 h after transfection, transiently transfected cells in 100-mm plates were treated with 50 μg/ml cycloheximide and harvested at different time points as indicated for the preparation of cell lysates. Equal amounts of proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE followed by immunoblot using the monoclonal anti-p63 antibody. These experiments were repeated twice.

p63γ in Vivo Ubiquitylation Assay—An in vivo ubiquitylation assay was conducted as described previously (35). H1299 cells in 100-mm plates were transfected with His6-ubiquitin (2 μg), FLAG-tagged IKK (2 μg), or pEGFP-C1-TAp63γ (2 μg). Transfected cells were treated with 10 μm of the proteasome inhibitor overnight before being harvested. 48 h after transfection, cells from each plate were harvested and split into 2 aliquots, one for straight immunoblot analysis and the other for detection of ubiquitylated proteins using Ni-NTA-agarose beads (Qiagen). Cell pellets were lysed in buffer A (6 m guanidinium chloride, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 5 mm imidazole, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol) and incubated with Ni-NTA beads at room temperature for 4 h. Beads were washed once with buffer A, buffer B (8 m urea, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol), and buffer C (8 m urea, 0.1 m Na2HPO4/NaH2PO4, 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.3, 10 mm β-mercaptoethanol). Proteins were eluted from beads with buffer D (200 mm imidazole, 0.15 m Tris-HCl, pH 6.7, 30% glycerol, 0.72 m β-mercaptoethanol, and 5% SDS). The eluted proteins were analyzed by immunoblot for the polyubiquitylation of p63γ with monoclonal p63 antibodies.

RESULTS

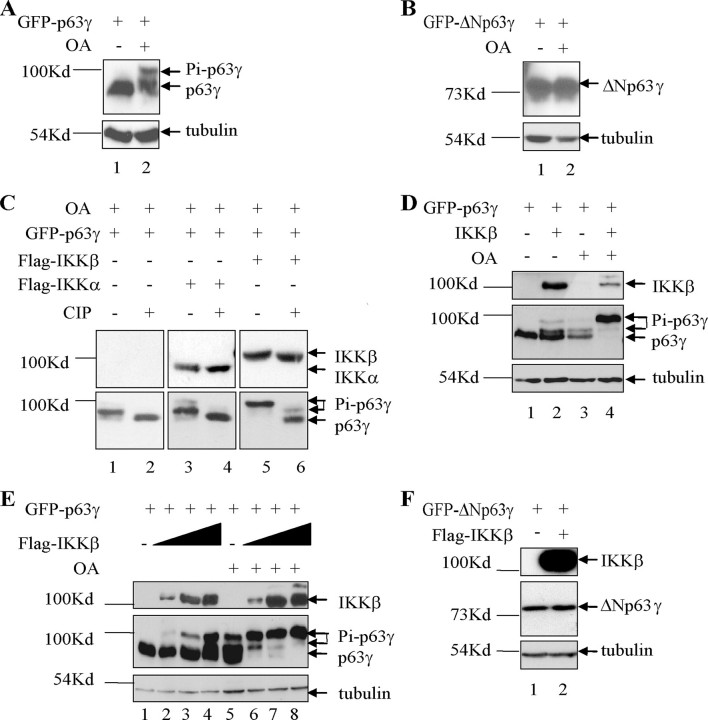

p63γ Is Phosphorylated by IKKα and IKKβ in Cells—Activation of p53 and p73 is known to occur through phosphorylation (23–26, 36–38). We have previously shown that TAp63γ, like p53 and p73, is regulated through acetylation (7). In this study we have examined whether TAp63γ also shares another post-translational modification common to p53 and p73, phosphorylation. It has been suggested previously that TAp63γ is phosphorylated in cells. Upon treatment of cells expressing TAp63γ with the Ser/Thr phosphatase inhibitor, okadaic acid (OA), a clear shift in mobility of TAp63γ was observed by Western blot (39). To elucidate whether the shift observed was in fact because of phosphorylation, we conducted further experiments to identify whether TAp63γ and ΔNp63γ isoforms of p63 are indeed phosphorylated. Human p53 null lung carcinoma H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-tagged TAp63γ and ΔNp63γ. Four hours prior to harvesting, the cells were treated with OA. p63 proteins from the cell lysates were detected by Western blot using an antibody that recognizes all isoforms of p63. Treatment of the transfected cells with okadaic acid led to a clear mobility shift for the TA form of p63γ (Fig. 1A). As reported previously, this result suggests that TAp63γ is phosphorylated in cells (39). No mobility shift for ΔNp63γ was observed upon treatment of cells with OA (Fig. 1B).

FIGURE 1.

p63γ is phosphorylated by IKKα and IKKβ in cells. A, TAp63γ undergoes a mobility shift in cells treated with OA. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ (0.5 μg). The cells were treated with OA for 4 h prior to harvest (48 h post-transfection), and the lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE using monoclonal antibodies against p63 and tubulin. B, ΔNp63γ does not undergo a mobility shift in cells treated with OA. The experiment was carried out as for A. C, TAp63γ mobility shift is lost upon treatment of the cell lysate with CIP but enhanced upon co-transfection of IKKα and IKKβ. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ and IKKα or IKKβ (0.5 μg). The cells were treated with OA for 4 h prior to harvest, and the lysates were treated or not with CIP for 1 h. The proteins were analyzed as above. D, H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ and IKKβ. The cells were treated with OA where shown for 4 h prior to harvest, and the proteins were analyzed as above. E, TAp63γ mobility shift/phosphorylation increases upon transfection of an increased amount of IKKβ. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ (0.5 μg) alone and with a titration of IKKβ (0.5, 1, and 2 μg). The cells were treated with OA or not for 4 h prior to harvest, and the lysates were analyzed as above. F, ΔNp63γ does not undergo a mobility shift in cells co-transfected with IKKβ. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-ΔNp63γ and IKKβ and the protein analyzed as above.

Like p63, the protein kinase IKKα is known to play an important role in skin development (40). Therefore, we decided to examine whether IKK kinases could phosphorylate p63γ. The IKK complex consists of three subunits, IKKα, IKKβ, and IKKγ (41, 42). As described earlier, these proteins play an important role in the NFκB regulatory pathway (20, 43–45). Upon co-expression of TAp63γ or ΔNp63γ together with FLAG-IKKα or FLAG-IKKβ, TAp63γ, but not ΔNp63γ, underwent a mobility shift (data not shown). In our studies this mobility shift was more strongly visible upon co-expression of the IKKβ protein, suggesting IKKβ overexpression leads to a higher level of phosphorylated TAp63γ than IKKα overexpression, similar to that seen for IκBα (41, 46). The experiment was repeated in the presence of OA. Upon co-transfection of IKKα or IKKβ with TAp63γ, the shifted migration of TAp63γ was stronger than observed with OA alone (Fig. 1C, lanes 1, 3, and 5). To confirm that this mobility shift is because of phosphorylation of TAp63γ, each cell lysate (using EDTA-free lysis buffer) was split in half and incubated in the presence or absence of calf intestinal phosphatase (CIP) for 1 h at 37°C. Upon CIP treatment, a distinct reduction or obliteration of the mobility shift was observed (Fig. 1C, lanes 2, 4, and 6). This suggests that the change in TAp63γ mobility upon both treatment of the cells with OA and co-expression of the IKK proteins is phosphorylation-dependent. Upon co-expression of IKKβ and p63γ in the presence of OA, only the higher mobility p63γ band was observed (Fig. 1C, lane 5). This suggests that IKKβ may act as the predominant IKK catalytic subunit for TAp63γ. IKKα and IKKβ are known to have largely nonoverlapping functions and to have different substrate specificities (47). The observed phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ is further confirmed in Fig. 1D. A side by side comparison of H1299 cells expressing TAp63γ in the presence of either IKKβ expression or treatment with OA demonstrates a comparable shift in mobility of TAp63γ. Combination of the two leads to a single slower mobility phosphorylated form of TAp63γ.

A titration of IKKβ co-expressed with TAp63γ led to a clear increase in the level of the slower migrating form of TAp63γ (Fig. 1E, lanes 1–4). In fact, this higher form was the only one visible upon treatment with OA, and it increased with an increasing amount of IKKβ expression (Fig. 1E, lanes 6–8). In addition, a co-expression of a kinase-dead form of IKKβ, IKKβ-K44A (defective in binding to ATP), did not induce a mobility shift for TAp63γ (Fig. 3B). Co-expression of FLAG-IKKβ with GFP-ΔNp63γ did not lead to a visible mobility shift (Fig. 1F).

FIGURE 3.

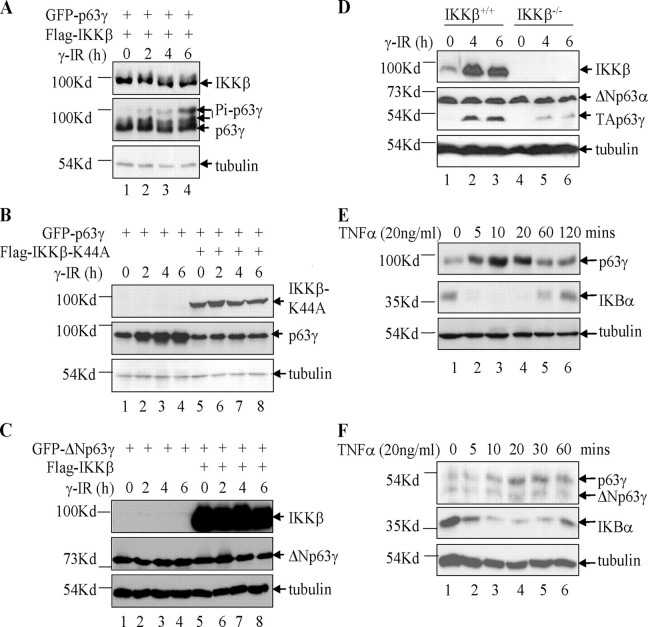

Activation of IKKβ induces stabilization of p63γ. A, γ radiation induces phosphorylation of p63γ by IKKβ. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ (0.5 μg) and IKKβ (0.5 μg). The cells were treated 48 h post-transfection with γ radiation (20 Gy) prior to harvest at the time points shown, and cell lysates were analyzed. B, IKKβ-K44A blocks the γ radiation-induced stabilization of p63γ by IKKβ. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ and IKKβ-K44A plasmids as indicated. Cell lysates were treated and analyzed as for A. C, ΔNp63γ was not stabilized upon exposure to γ radiation or phosphorylated upon co-expression of IKKβ. HEK293 cells were transfected with GFP-ΔNp63γ and IKKβ plasmids as indicated. Cell lysates were treated and analyzed as for A. D, IKKβ is required for the stabilization of TAp63γ in response to γ radiation. IKKβ+/+ and IKKβ–/– MEF cells were treated with γ radiation and analyzed as for A. E, TNFα induction of IKKβ activity leads to the stabilization of TAp63γ protein levels. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ. The cells were treated 48 h post-transfection with TNFα prior to harvest at the time points shown. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE. F, TNFα induces stabilization of endogenous p63γ in HEK cells. HEK cells were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml), and cell lysates were analyzed as in A.

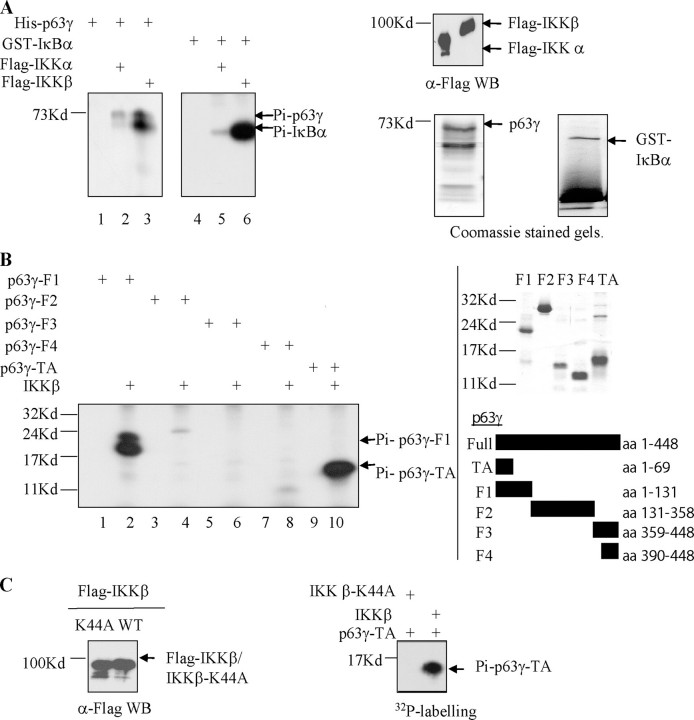

p63γ Is Differentially Phosphorylated by IKKα and IKKβ in Vitro—To confirm that TAp63γ is a substrate for IKKα and IKKβ, IP kinase assays were utilized. FLAG-tagged IKK proteins were expressed in HEK293 cells, and the proteins were recovered by immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG antibody (Fig. 2A, top right panel). After an extensive wash, this immune complex was used in an in vitro kinase assay. His-tagged TAp63γ was purified from E. coli and used as a substrate in the IP kinase assay as described under “Experimental Procedures” (Fig. 2A, bottom right panel). Phosphorylated products were resolved by SDS-PAGE and visualized by autoradiography. IKKβ was again observed to be the major IKK catalytic subunit for TAp63γ phosphorylation (Fig. 2A, lanes 2 and 3). GST-IκBα, a known substrate for IKK kinase activity, was also purified and used as a substrate in the IP kinase assay. GST-IκBα was used as a positive control for the assay (Fig. 2A, lanes 4–6), and as reported previously, IKKβ is also the major catalytic IKK activity for IκBα (1, 48).

FIGURE 2.

IKKα and IKKβ phosphorylate p63γ. A, IKKα and IKKβ phosphorylate p63γ in vitro. IP kinase assays were performed using FLAG immunoprecipitates of FLAG-IKKα and FLAG-IKKβ (top right panel) expressed in HEK293 cells and 100 ng of His-p63γ or GST-IκBα protein (bottom right panels). Radiolabeled His-p63γ and GST-IκBα were fractionated by SDS-PAGE and exposed for autoradiography. B, IKKβ phosphorylates the N terminus of p63γ. IP kinase assays were performed as in A, this time using deletion mutants of p63γ as shown. Phosphorylated proteins were resolved as above. C, IKKβ-K44A, a kinase-dead form of IKKβ, does not phosphorylate p63γ. IP kinase assays were performed as in A (right panel), this time with immunoprecipitates from HEK293 cells expressing either IKKβ-K44A or IKKβ (left panel). WB, Western blot; WT, wild type; aa, amino acids.

The observation that co-expression of IKKβ proteins and TAp63γ in cells results in a mobility shift in TAp63γ but not in ΔNp63γ suggests that phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ occurs at the N terminus of this protein. To further investigate the region of TAp63γ phosphorylated by IKKβ, we used purified His-tagged deletion mutants of TAp63γ (F1, amino acids 1–131; F2, amino acids 131–358; F3, amino acids 359–448; F4, amino acids 390–448, and TA, amino acids 1–69) as substrates in an IP kinase assay with IKKβ (Fig. 2B, right panel). A strong phosphorylation signal was seen using either p63γTA or p63γ-F1 but not when using the other fragments, supporting the idea that phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ occurs at the N-terminal domain, within the first 69 amino acids (Fig. 2B, lanes 2 and 10). These phosphoproteins were absent, as shown for p63γTA, when IKKβ was replaced by IKKβ-K44A, a kinase-dead form of IKKβ (Fig. 2C) (20, 49, 50).

Activation of IKKβ Activity in Cells Leads to Increased Phosphorylation and Protein Levels of TAp63γ—Exposure of cells to different forms of genotoxic stress, such as ionizing (γ) radiation, stimulates signaling pathways that are known to activate transcription factors such as NF-κB and p53. IKKβ has been demonstrated to be activated in response to γ radiation (maximal at 20 Gy), which leads to induction of NF-κB activity (51). p53 has also been shown to be activated and phosphorylated in response to γ radiation (52–54). More recently, TAp63α in mouse oocytes has been shown to undergo a mobility shift in response to exposure to γ radiation (34). To test whether activation of IKKβ by γ radiation had any effect on TAp63γ, we initially co-transfected HEK293 (p53 inactive) with expression plasmids for FLAG-IKKβ and GFP-tagged TAp63γ. After 48 h of incubation, the cells were irradiated (20 Gy) and harvested at 0, 2, 4, and 6 h post-irradiation. Upon exposure to γ radiation of cells expressing IKKβ and TAp63γ, there was a clear increase in the protein levels of TAp63γ and also an increased amount of the phosphorylated form of the protein (Fig. 3A, lanes 1–4). The experiment was repeated with cells expressing TAp63γ alone or with co-expression of IKKβ-K44A. In cells expressing TAp63γ alone, there was a clear increase in the protein levels of TAp63γ over time (Fig. 3B, lanes 1–4). However, upon co-transfection with IKKβ-K44A, this increase in the level of TAp63γ protein was no longer observed (Fig. 3B, lanes 5–8). As IKKβ-K44A is a kinase-dead mutant and is known to act as a dominant-negative regulator of IKKβ, these data suggest that the increased level of TAp63γ upon exposure of the cells to γ radiation is dependent on endogenous IKKβ kinase activity (49, 55, 56). IKKβ-K44A has been demonstrated not to act in a dominant-negative manner against IKKα (1, 57). These experiments were repeated several times, and the results were highly consistent.

In addition, we tested whether activation of IKKβ by γ radiation had any effect on ΔNp63γ protein levels. We cotransfected HEK293 cells with expression plasmids for FLAG-IKKβ and GFP-tagged ΔNp63γ. After 48 h of incubation, cells were irradiated (20 Gy) and harvested at 0, 2, 4, and 6 h post-irradiation. Neither irradiation nor co-expression of IKKβ had any effect on ΔNp63γ protein levels (Fig. 3C). These observations contribute further evidence that the N terminus of TAp63γ is essential for the IKKβ-dependent stabilization of TAp63γ.

Next, we exposed IKKβ+/+ and IKKβ–/– MEF cells to γ radiation (20 Gy) and harvested at 0, 4, and 6 h post-irradiation. A clear increase in TAp63γ protein levels was observed upon irradiation in the IKKβ+/+ MEF cells (Fig. 3D, lanes 1–3). This increase in TAp63γ protein levels was significantly reduced in the IKKβ–/– MEF cells (Fig. 3D, lanes 4–6). This observation, along with those in Fig. 3, A and B, further supports the conclusion that IKKβ activation through irradiation leads to phosphorylation and stabilization of TAp63γ. ΔNp63γ was not detected in these cell lines; however, ΔNp63α levels did not change upon irradiation. This further supports the necessity for the N terminus of TAp63γ for this stabilization effect.

The activation of IKKβ by γ radiation is known to be slower and weaker than that seen in response to the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα (51). TNFα is a classic activator of the NFκB pathway that utilizes IKKβ as its major IKK catalytic subunit (19, 47). Therefore, it was of interest to test whether we could see similar effects on TAp63γ levels through activation of IKKβ by TNFα. H1299 cells were transfected with TAp63γ and after 48 h were treated with TNFα (20 ng/ml). Similar to γ radiation, exposure to TNFα led to increased TAp63γ protein levels (Fig. 3E, lanes 2–4). This increase was reduced back to normal levels after 60 min of exposure to TNFα (Fig. 3E, lane 5). This pattern of expression was coincident with an initial severe drop in IκBα protein levels and subsequent restoration of normal levels. The known phosphorylation and the subsequent degradation of the NFκB-negative regulator IκBα by IKKβ, in response to treatment of the cells with TNFα, acts as a useful control for the specific effects of IKKβ activation on TAp63γ protein level. HEK cells were also treated with TNFα, and a clear increase in endogenous TAp63γ protein level was observed concomitant with a decrease in IκBα protein level. This further supports the specific effects on TAp63γ protein level through the activation of IKKβ (Fig. 3F). No such increase in level was seen for ΔNp63γ, supporting earlier observations that the N terminus of TAp63γ is essential for the IKKβ-dependent stabilization of TAp63γ.

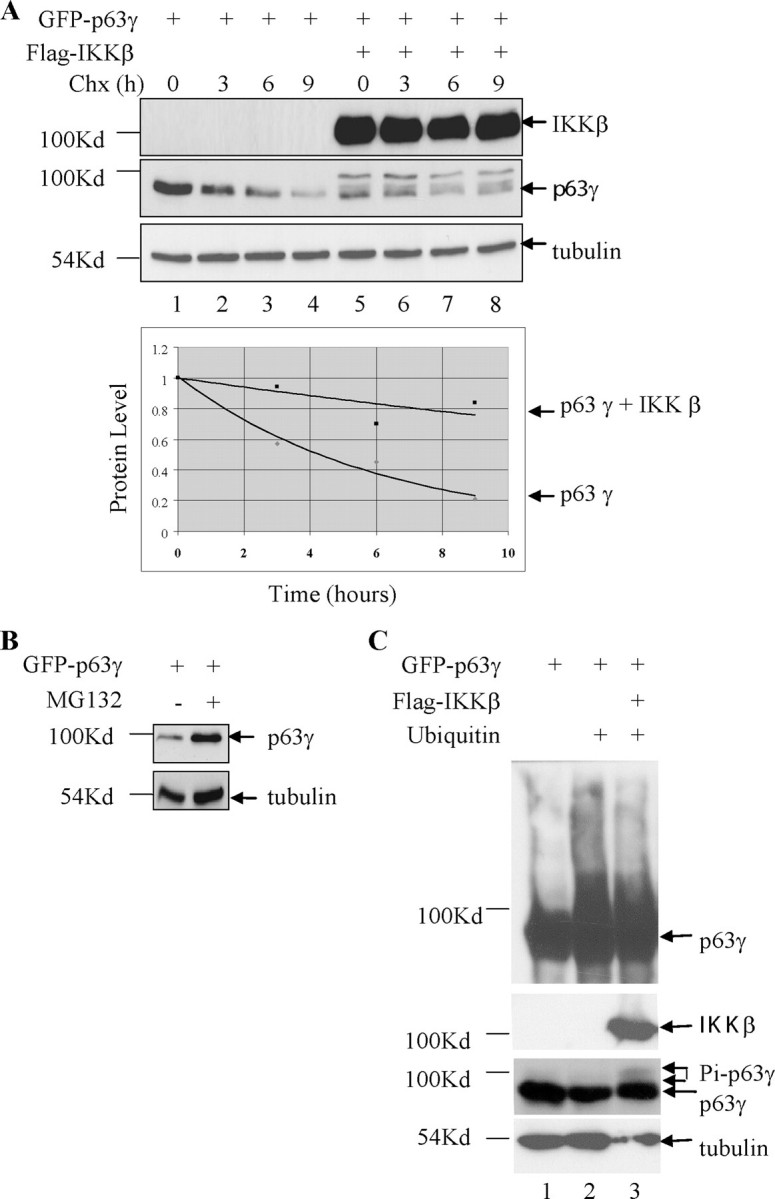

IKKβ Inhibition of Degradation of TAp63γ Protein—We have shown that TAp63γ is phosphorylated by IKKβ. In addition, upon activation of IKKβ by γ radiation or TNFα, TAp63γ protein level clearly increases in an IKKβ-dependent manner. This suggests that activation of IKKβ could stabilize TAp63γ in cells. To test whether IKKβ has any effect on TAp63γ half-life, H1299 cells were co-transfected with both FLAG-IKKβ and GFP-TAp63γ. Forty eight hours post-transfection, these cells were treated with the translation inhibitor cycloheximide for 0, 3, 6, and 9 h. TAp63γ protein level was monitored by Western blot. Co-expression of IKKβ clearly stabilizes TAp63γ protein levels leading to a significant increase in protein half-life (Fig. 4A, lanes 5–8).

FIGURE 4.

TAp63γ protein levels are stabilized by IKKβ. A, increased half-life of TAp63γ in the presence of IKKβ. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ alone or together with IKKβ. 48 h post-transfection the cells were treated with cycloheximide (50 μg/ml) and harvested at the time points shown. Cell lysates were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (upper panel). Densitometric analysis of all the TAp63γ protein bands relative to tubulin were measured and plotted on a graph (lower panel). B, TAp63γ levels stabilize in response to treatment of cells with MG132. H1299 cells were transfected with GFP-TAp63γ and 36 h later were treated or not with MG132 (10μm) overnight prior to harvest. C, TAp63γ is ubiquitylated in cells and phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ blocks ubiquitylation. H1299 cells were transfected with His-ubiquitin, GFP-TAp63γ, or IKKβ. 36 h post-transfection cells were treated with 10 μm MG132 overnight before being harvested. The in vivo ubiquitylation assay was carried out as described under the “Experimental Procedures.” Portions of the lysates were directly analyzed by SDS-PAGE (bottom panels), and the remainder was used for the ubiquitylation assay (top panel).

To understand how this stabilization occurs, we investigated the possibility that IKKβ blocks ubiquitylation and degradation of TAp63γ. TAp63γ protein levels expressed in H1299 cells increase 2.1-fold as measured by densitometry normalized to tubulin levels, upon treatment with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 4B), suggesting that TAp63γ is degraded by the proteasome. ΔNp63α and TAp63α have previously been demonstrated to be ubiquitylated and degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner (32). In vivo ubiquitylation assays were performed using H1299 cells co-transfected with a combination of plasmids expressing His-tagged ubiquitin, TAp63γ, and IKKβ. Immunoblots demonstrated the expression of TAp63γ and IKKβ. The ubiquitylation assays were performed using the remainder of the cells with Ni-NTA-agarose bead-facilitated pulldown of ubiquitylated proteins and the detection of the ubiquitylated TAp63γ using anti-p63 antibody (Fig. 4C, top panel). Although TAp63γ bound nonspecifically to the Ni-NTA-agarose beads, the protein was clearly ubiquitylated in the presence of ubiquitin (Fig. 4C, lane 2). Upon co-expression of IKKβ, the ubiquitylation of TAp63γ was clearly reduced (Fig. 4C, lane 3). These observations suggest the phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ stabilizes this protein through blocking ubiquitylation and subsequent proteasomal degradation of the protein.

DISCUSSION

Our experiments indicate that TAp63γ is phosphorylated by the IκBα kinase, IKKβ. However, ΔNp63γ is not. Previous studies have studied p63 phosphorylation, but no specific kinase for p63 has been identified thus far (32, 34, 39, 58). Our initial studies demonstrate phosphorylation of TAp63γ by IKKβ and to a lesser extent by IKKα in cells (Fig. 1C). These observations were confirmed using in vitro kinase assays (Fig. 2, A and B). As is the case for IκBα, IKKβ is the major IKK catalytic activity for TAp63γ (Fig. 2A). TAp63γ phosphorylation by IKKβ localized to the N terminus of TAp63γ (Fig. 1, F and B).

IKKβ is activated through a number of pathways, including exposure of cells to γ radiation, and also through addition of the pro-inflammatory cytokine TNFα. Following the physiological activation of IKKβ by either of these methods, TAp63γ protein phosphorylation, protein level, and half-life increased significantly. Upon exposure of cells expressing TAp63γ alone, this increase in protein level was also observed (Fig. 3, B and E). From co-expression of the dominant-negative kinase-dead mutant IKKβ-K44A with TAp63γ, it is clear that this increase in protein level in response to irradiation is dependent on IKKβ kinase activity. This stabilization does not occur when ΔNp63γ is used instead of TAp63γ, supporting the apparent requirement for phosphorylation of TAp63γ on its N terminus by IKKβ (Fig. 3, C and F). To more directly test the dependence on IKKβ for the stabilization of TAp63γ in response to γ radiation, we used IKKβ–/– MEF cells. A significant reduction in the stabilization of TAp63γ was observed in IKKβ–/– MEF cells compared with IKKβ+/+ MEF cells (Fig. 3D). This supports a direct role for IKKβ-dependent stabilization of TAp63γ in response to irradiation.

We hypothesize that stabilization of the TAp63γ protein could be a result of blocking ubiquitylation and subsequent degradation of this protein. TAp63α has been shown to be ubiquitylated and degraded in a proteasome-dependent manner (33). A recent study demonstrated that ΔNp63α was phosphorylated and ubiquitylated in response to DNA damage mediating its degradation in a proteasome-dependent manner (32). Unlike ΔNp63α, in the presence of increased phosphorylation of TAp63γ, there was a distinct decrease in ubiquitylation of TAp63γ (Fig. 4C). TAp63γ protein levels expressed in H1299 cells increase upon treatment of the cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (Fig. 4B). This supports previous observations that TAp63γ can be degraded through a proteasome-dependent mechanism (59). our laboratory has recently reported that SCFβTrCP1 is an E3 ligase for TAp63γ and activates this protein through ubiquitylation (60). This activation of TAp63γ leads to up-regulation of p21. However, phosphorylation and stabilization of TAp63γ by IKKβ did not lead to up-regulation of p21 (data not shown), suggesting that phosphorylation at the N terminus of p63 might regulate the expression of different, yet unidentified, target genes. Because both SCFβTrCP1 (55) and IKKβ (this study) stabilize TAp63γ, this p63 form is an atypical substrate for either of the enzymes.

Our observations suggest phosphorylation/ubiquitylation systems for TAp63γ similar to that of other members of the p53 family. In response to γ radiation, p53 is stabilized through phosphorylation by Chk2 (24, 61, 62). Interestingly, p73 has recently been demonstrated to be stabilized through IKKα-dependent phosphorylation (63). This stabilization was not observed with IKKβ. Our results suggest that different members of the p53 family are targeted by different members of the IKK family.

Like Dok1, TAp63γ represents a “nonclassical” IKKβ substrate (64). The consensus motif for IKK phosphorylation of IκB proteins is DSGψXS (65). ψ represents a hydrophobic amino acid and X any amino acid. We have analyzed the TAp63γ amino acid sequence for a putative phosphorylation site targeted by IKKβ but did not observe any motifs to match this consensus sequence. However, the recently reported phosphorylation of p73 by IKKα occurred in the same region of this protein as we have reported for TAp63γ. We are currently using mutagenesis experiments to identify the residues of TAp63γ phosphorylated by IKKβ and test their effects on TAp63γ activity.

The observed phosphorylation and stabilization of TAp63γ by IKKβ are intriguing given the recently observed common regulatory pathways between p53 family members and IKK proteins (22, 63). The major role for p63 appears to be in the regulation of epithelial development (11, 12). p63 is required for the formation of the epidermis and other stratified epithelia. Interestingly, epidermis-specific deletion of IKKβ has been demonstrated to result in a severe inflammatory skin disease (66). This suggests a role for IKKβ in the maintenance of immune homeostasis of the skin. NF-κB deregulation has also been suggested to play an important role in skin pathology, including proliferative disorders such as psoriasis and dermatitis (67). Abnormal keratinocyte proliferation and differentiation have been associated with such diseases (68). Up-regulation of cytokines such as TNF has also been associated with the pathogenesis of psoriasis (67). TNF is known to act through the classical or “canonical” pathway for activation of NF-κB, which depends on IKKβ activity. Potentially, deregulation of IKKβ could lead to both a pro-inflammatory gene expression response and phosphorylation and stabilization of TAp63 protein levels. This effect on Tap63 protein levels could potentially contribute to the pathology of these skin diseases. Together the effects could be devastating on the regulation of keratinocyte activation and proliferation. Our group is currently investigating the regulation, by TAp63 and IKKβ, of gene expression of several genes key to the development of such diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Paul J. Chiao and Dr. M. Hu for reagents (University of Texas M. D. Anderson Cancer Center). We thank Jayme Gallegos and Igor Landais for critical reading of the manuscript. Sincere thanks to all the members of the Lu laboratory for stimulating discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants CA127724, CA 93614, CA 095441, and CA 079721 (to H. L.) from NCI. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: TA, transactivation; ΔN, deletion of N terminus; GFP, green fluorescence protein; GST, glutathione S-transferase; IKK, IκB kinase; TNF, tumor necrosis factor; OA, okadaic acid; CIP, calf intestinal phosphatase; MEF, mouse embryonic fibroblast; Ni-NTA, nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid; HEK, human epidermal keratinocytes; Gy, gray.

References

- 1.Li, J., Peet, G. W., Pullen, S. S., Schembri-King, J., Warren, T. C., Marcu, K. B., Kehry, M. R., Barton, R., and Jakes, S. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 27330736 –30741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osada, M., Ohba, M., Kawahara, C., Ishioka, C., Kanamaru, R., Katoh, I., Ikawa, Y., Nimura, Y., Nakagawara, A., Obinata, M., and Ikawa, S. (1998) Nat. Med. 4839 –843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang, A., Kaghad, M., Wang, Y., Gillett, E., Fleming, M. D., Dotsch, V., Andrews, N. C., Caput, D., and McKeon, F. (1998) Mol. Cell 2305 –316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zeng, S. X., Dai, M. S., Keller, D. M., and Lu, H. (2002) EMBO J. 215487 –5497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Serber, Z., Lai, H. C., Yang, A., Ou, H. D., Sigal, M. S., Kelly, A. E., Darimont, B. D., Duijf, P. H., Van Bokhoven, H., McKeon, F., and Dotsch, V. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 228601 –8611 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koster, M. I., Kim, S., Huang, J., Williams, T., and Roop, D. R. (2006) Dev. Biol. 289253 –261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.MacPartlin, M., Zeng, S., Lee, H., Stauffer, D., Jin, Y., Thayer, M., and Lu, H. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 28030604 –30610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koster, M. I., Kim, S., Mills, A. A., DeMayo, F. J., and Roop, D. R. (2004) Genes Dev. 18126 –131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michael, D., and Oren, M. (2002) Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 1253 –59 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Flores, E. R. (2007) Cell Cycle 6300 –304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mills, A. A., Zheng, B., Wang, X. J., Vogel, H., Roop, D. R., and Bradley, A. (1999) Nature 398708 –713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang, A., Schweitzer, R., Sun, D., Kaghad, M., Walker, N., Bronson, R. T., Tabin, C., Sharpe, A., Caput, D., Crum, C., and McKeon, F. (1999) Nature 398714 –718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Celli, J., Duijf, P., Hamel, B. C., Bamshad, M., Kramer, B., Smits, A. P., Newbury-Ecob, R., Hennekam, R. C., Van Buggenhout, G., van Haeringen, A., Woods, C. G., van Essen, A. J., de Waal, R., Vriend, G., Haber, D. A., Yang, A., McKeon, F., Brunner, H. G., and van Bokhoven, H. (1999) Cell 99143 –153 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ianakiev, P., Kilpatrick, M. W., Toudjarska, I., Basel, D., Beighton, P., and Tsipouras, P. (2000) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 6759 –66 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McGrath, J. A., Duijf, P. H., Doetsch, V., Irvine, A. D., de Waal, R., Vanmolkot, K. R., Wessagowit, V., Kelly, A., Atherton, D. J., Griffiths, W. A., Orlow, S. J., van Haeringen, A., Ausems, M. G., Yang, A., McKeon, F., Bamshad, M. A., Brunner, H. G., Hamel, B. C., and van Bokhoven, H. (2001) Hum. Mol. Genet. 10221 –229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Bokhoven, H., Hamel, B. C., Bamshad, M., Sangiorgi, E., Gurrieri, F., Duijf, P. H., Vanmolkot, K. R., van Beusekom, E., van Beersum, S. E., Celli, J., Merkx, G. F., Tenconi, R., Fryns, J. P., Verloes, A., Newbury-Ecob, R. A., Raas-Rotschild, A., Majewski, F., Beemer, F. A., Janecke, A., Chitayat, D., Crisponi, G., Kayserili, H., Yates, J. R., Neri, G., and Brunner, H. G. (2001) Am. J. Hum. Genet. 69481 –492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu, Y., Baud, V., Delhase, M., Zhang, P., Deerinck, T., Ellisman, M., Johnson, R., and Karin, M. (1999) Science 284316 –320 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Takeda, K., Takeuchi, O., Tsujimura, T., Itami, S., Adachi, O., Kawai, T., Sanjo, H., Yoshikawa, K., Terada, N., and Akira, S. (1999) Science 284313 –316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Israel, A., Le Bail, O., Hatat, D., Piette, J., Kieran, M., Logeat, F., Wallach, D., Fellous, M., and Kourilsky, P. (1989) EMBO J. 83793 –3800 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mercurio, F., Zhu, H., Murray, B. W., Shevchenko, A., Bennett, B. L., Li, J., Young, D. B., Barbosa, M., Mann, M., Manning, A., and Rao, A. (1997) Science 278860 –866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DiDonato, J. A., Hayakawa, M., Rothwarf, D. M., Zandi, E., and Karin, M. (1997) Nature 388548 –554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Candi, E., Terrinoni, A., Rufini, A., Chikh, A., Lena, A. M., Suzuki, Y., Sayan, B. S., Knight, R. A., and Melino, G. (2006) J. Cell Sci. 1194617 –4622 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agami, R., Blandino, G., Oren, M., and Shaul, Y. (1999) Nature 399809 –813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakin, N. D., and Jackson, S. P. (1999) Oncogene 187644 –7655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sakaguchi, K., Herrera, J. E., Saito, S., Miki, T., Bustin, M., Vassilev, A., Anderson, C. W., and Appella, E. (1998) Genes Dev. 122831 –2841 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shieh, S. Y., Ikeda, M., Taya, Y., and Prives, C. (1997) Cell 91325 –334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Avantaggiati, M. L., Ogryzko, V., Gardner, K., Giordano, A., Levine, A. S., and Kelly, K. (1997) Cell 891175 –1184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gu, W., and Roeder, R. G. (1997) Cell 90595 –606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lill, N. L., Tevethia, M. J., Eckner, R., Livingston, D. M., and Modjtahedi, N. (1997) J. Virol. 71129 –137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ghioni, P., D'Alessandra, Y., Mansueto, G., Jaffray, E., Hay, R. T., La Mantia, G., and Guerrini, L. (2005) Cell Cycle 4183 –190 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Huang, Y. P., Wu, G., Guo, Z., Osada, M., Fomenkov, T., Park, H. L., Trink, B., Sidransky, D., Fomenkov, A., and Ratovitski, E. A. (2004) Cell Cycle 31587 –1596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Westfall, M. D., Joyner, A. S., Barbieri, C. E., Livingstone, M., and Pietenpol, J. A. (2005) Cell Cycle 4710 –716 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rossi, M., Aqeilan, R. I., Neale, M., Candi, E., Salomoni, P., Knight, R. A., Croce, C. M., and Melino, G. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 10312753 –12758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suh, E. K., Yang, A., Kettenbach, A., Bamberger, C., Michaelis, A. H., Zhu, Z., Elvin, J. A., Bronson, R. T., Crum, C. P., and McKeon, F. (2006) Nature 444624 –628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xirodimas, D., Saville, M. K., Edling, C., Lane, D. P., and Lain, S. (2001) Oncogene 204972 –4983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanchez-Prieto, R., Sanchez-Arevalo, V. J., Servitja, J. M., and Gutkind, J. S. (2002) Oncogene 21974 –979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Unger, T., Sionov, R. V., Moallem, E., Yee, C. L., Howley, P. M., Oren, M., and Haupt, Y. (1999) Oncogene 183205 –3212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yuan, Z. M., Shioya, H., Ishiko, T., Sun, X., Gu, J., Huang, Y. Y., Lu, H., Kharbanda, S., Weichselbaum, R., and Kufe, D. (1999) Nature 399814 –817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okada, Y., Osada, M., Kurata, S., Sato, S., Aisaki, K., Kageyama, Y., Kihara, K., Ikawa, Y., and Katoh, I. (2002) Exp. Cell Res. 276194 –200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sil, A. K., Maeda, S., Sano, Y., Roop, D. R., and Karin, M. (2004) Nature 428660 –664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zandi, E., Rothwarf, D. M., Delhase, M., Hayakawa, M., and Karin, M. (1997) Cell 91243 –252 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamaoka, S., Courtois, G., Bessia, C., Whiteside, S. T., Weil, R., Agou, F., Kirk, H. E., Kay, R. J., and Israel, A. (1998) Cell 931231 –1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zandi, E., Chen, Y., and Karin, M. (1998) Science 2811360 –1363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen, Z., Hagler, J., Palombella, V. J., Melandri, F., Scherer, D., Ballard, D., and Maniatis, T. (1995) Genes Dev. 91586 –1597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alkalay, I., Yaron, A., Hatzubai, A., Orian, A., Ciechanover, A., and Ben-Neriah, Y. (1995) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9210599 –10603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wu, C., and Ghosh, S. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 27831980 –31987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hacker, H., and Karin, M. (2006) Sci. STKE 2006 (357)RE13. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Lee, F. S., Peters, R. T., Dang, L. C., and Maniatis, T. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 959319 –9324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Delhase, M., Hayakawa, M., Chen, Y., and Karin, M. (1999) Science 284309 –313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mercurio, F., Murray, B. W., Shevchenko, A., Bennett, B. L., Young, D. B., Li, J. W., Pascual, G., Motiwala, A., Zhu, H., Mann, M., and Manning, A. M. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 191526 –1538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li, N., and Karin, M. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9513012 –13017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kuerbitz, S. J., Plunkett, B. S., Walsh, W. V., and Kastan, M. B. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 897491 –7495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Giaccia, A. J., and Kastan, M. B. (1998) Genes Dev. 122973 –2983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Higashimoto, Y., Saito, S., Tong, X. H., Hong, A., Sakaguchi, K., Appella, E., and Anderson, C. W. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 27523199 –23203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Regnier, C. H., Song, H. Y., Gao, X., Goeddel, D. V., Cao, Z., and Rothe, M. (1997) Cell 90373 –383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woronicz, J. D., Gao, X., Cao, Z., Rothe, M., and Goeddel, D. V. (1997) Science 278866 –869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.O'Mahony, A., Lin, X., Geleziunas, R., and Greene, W. C. (2000) Mol. Cell. Biol. 201170 –1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Westfall, M. D., Mays, D. J., Sniezek, J. C., and Pietenpol, J. A. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 232264 –2276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ying, H., Chang, D. L., Zheng, H., McKeon, F., and Xiao, Z. X. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 256154 –6164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gallegos, J. R., Litersky, J., Lee, H., Sun, Y., Nakayama, K., Nakayama, K., and Lu, H. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 28366 –75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Fallis, L. H., Richards, E., O'Connor, D. J., Zhong, S., Hsieh, J. K., Packham, G., and Lu, X. (1999) Apoptosis 499 –107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirao, A., Kong, Y. Y., Matsuoka, S., Wakeham, A., Ruland, J., Yoshida, H., Liu, D., Elledge, S. J., and Mak, T. W. (2000) Science 2871824 –1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Furuya, K., Ozaki, T., Hanamoto, T., Hosoda, M., Hayashi, S., Barker, P. A., Takano, K., Matsumoto, M., and Nakagawara, A. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28218365 –18378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Lee, S., Andrieu, C., Saltel, F., Destaing, O., Auclair, J., Pouchkine, V., Michelon, J., Salaun, B., Kobayashi, R., Jurdic, P., Kieff, E. D., and Sylla, B. S. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 10117416 –17421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Karin, M. (1999) Oncogene 186867 –6874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Pasparakis, M., Courtois, G., Hafner, M., Schmidt-Supprian, M., Nenci, A., Toksoy, A., Krampert, M., Goebeler, M., Gillitzer, R., Israel, A., Krieg, T., Rajewsky, K., and Haase, I. (2002) Nature 417861 –866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bell, S., Degitz, K., Quirling, M., Jilg, N., Page, S., and Brand, K. (2003) Cell. Signal. 151 –7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Prens, E., Hegmans, J., Lien, R. C., Debets, R., Troost, R., van Joost, T., and Benner, R. (1996) Am. J. Pathol. 1481493 –1502 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]