Abstract

The BLAP75 protein combines with the BLM helicase and topoisomerase (Topo) IIIα to form an evolutionarily conserved complex, termed the BTB complex, that functions to regulate homologous recombination. BLAP75 binds DNA, associates with both BLM and Topo IIIα, and enhances the ability of the BLM-Topo IIIα pair to branch migrate the Holliday junction (HJ) or dissolve the double Holliday junction (dHJ) structure to yield non-crossover recombinants. Here we seek to understand the relevance of the biochemical attributes of BLAP75 in HJ processing. With the use of a series of BLAP75 protein fragments, we show that the evolutionarily conserved N-terminal third of BLAP75 mediates complex formation with BLM and Topo IIIα and that the DNA binding activity resides in the C-terminal third of this novel protein. Interestingly, the N-terminal third of BLAP75 is just as adept as the full-length protein in the promotion of dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding by BLM-Topo IIIα. Thus, the BLAP75 DNA binding activity is dispensable for the ability of the BTB complex to process the HJ in vitro. Lastly, we show that a BLAP75 point mutant (K166A), defective in Topo IIIα interaction, is unable to promote dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding by BLM-Topo IIIα. This result provides proof that the functional integrity of the BTB complex is contingent upon the interaction of BLAP75 with Topo IIIα.

Bloom syndrome is a rare, hereditary disorder characterized by proportional dwarfism, light sensitivity, immunodeficiency, male infertility, and high incidence of various types of cancer (1). Cells derived from patients with Bloom syndrome display a high degree of chromosomal instability, marked by a dramatic increase in the frequency of sister chromatid exchanges that arise from the crossing over of chromatid arms during resolution of homologous recombination (HR)3 intermediates (2, 3). These results indicate an important function of BLM, the protein mutated in Bloom syndrome, in the suppression of HR-mediated crossover events.

BLM is one of the five RecQ-like DNA helicases in humans (4, 5). Consistent with its HR regulatory role, BLM is able to dissociate various DNA structures that resemble HR intermediates, such as the D-loop and Holliday junction (HJ) (6–8). Importantly, BLM cooperates with Topo IIIα, a Type 1A topoisomerase, to catalyze the resolution of the double Holliday junction (dHJ) intermediate to generate exclusively non-crossover recombinants, in a process termed “dHJ dissolution” (9). Remarkably, BLM also acts to disrupt the Rad51 presynaptic filament and can stimulate DNA repair synthesis by DNA polymerase η (10). All these noted HR-related functions of BLM are strictly dependent on its ATPase activity (9–11). The ability of BLM to unwind HR intermediates, to mediate the dismantling of the Rad51 presynaptic filament, and to catalyze Topo IIIα-dependent dHJ dissolution is likely important for the regulation of HR to limit the formation of crossovers and prevent genome rearrangements induced by crossover HR events (10, 12, 13), whereas the DNA repair synthesis activity of BLM may promote the use of the non-crossover-producing synthesis-dependent strand annealing mechanism of HR (10, 14).

The BLM-Topo IIIα complex is stably bound to a third protein called BLAP75 (BLM-associated protein of 75 kDa) (15). Importantly, cells depleted of BLAP75 exhibit defects in cell proliferation, impaired DNA damage-induced BLM focus formation, and an increased level of sister chromatid exchanges just like BLM-deficient cells (16). Biochemical analyses have revealed that BLAP75 interacts with both BLM and Topo IIIα (17, 18). Importantly, BLAP75 strongly enhances the BLM-Topo IIIα-mediated dHJ dissolution reaction (17, 18) and acts in conjunction with Topo IIIα to up-regulate the helicase activity of BLM (11). It is not known whether the ability of BLM to disrupt the Rad51 presynaptic filament or to stimulate DNA repair synthesis is similarly enhanced by BLAP75.

The BTB (BLM-Topo IIIα-BLAP75) complex and its role in the maintenance of genome stability appear to be evolutionarily conserved among eukaryotes. In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the BLAP75 orthologue, Rmi1, interacts with and is required for the stability of Sgs1 and Top3 (the BLM and Topo IIIα equivalents, respectively) (19, 20). The rmi1Δ and top3Δ mutants show similar phenotypes of slow growth, chromosomal instability, and hyper-recombination that can be suppressed by inactivating either Sgs1 or components of the HR pathway (19, 20). Together, these data indicate that Top3 and Rmi1 act in the Sgs1-dependent pathway of HR regulation to specifically minimize the formation of crossovers.

BLAP75 harbors 625 amino acid residues and possesses a DNA binding activity (16, 18). The N-terminal region harbors a putative OB-fold (see Fig. 1A) (16), which is known to confer DNA binding capability to a variety of proteins, including RPA and BRCA2 (21). Although Rmi1 (241 amino acid residues) is considerably smaller than its human counterpart, it also possesses a DNA binding activity, and the greatest amino acid sequence similarity to BLAP75 occurs in the region of the putative OB-fold (19, 20, 22). A second conserved domain located in the C-terminal region of BLAP75 orthologues does not contain any recognizable motif and is absent in yeast Rmi1 (16).

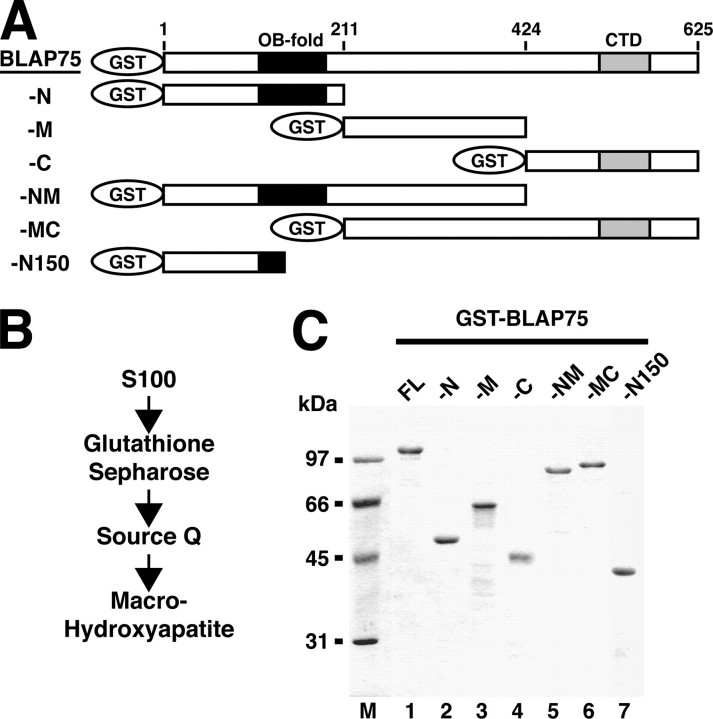

FIGURE 1.

Expression and purification of GST-tagged BLAP75 fragments. A, a schematic representation of BLAP75 fragments expressed as GST fusion proteins is shown. Black boxes represent the predicted OB-fold domain, whereas gray boxes represent the conserved C-terminal domain (CTD). Numbers refer to amino acid residue numbers/positions in BLAP75. B, a purification scheme is shown. C, the purified GST-tagged BLAP75 fragments (1 μg each) were resolved by SDS-PAGE and stained with Coomassie Blue. FL, full-length.

In this study, we delineate the domains of BLAP75 involved in protein-protein interactions and DNA binding. We show that both BLM and Topo IIIα interact with the OB-fold-containing N-terminal region of BLAP75, whereas the DNA binding activity resides within the C-terminal region. Interestingly, a polypeptide comprising the N terminus (residues 1–211) of BLAP75 is as proficient as full-length BLAP75 in the promotion of dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding by BLM-Topo IIIα. We have also constructed a BLAP75 point mutant (K166A) that attenuates binding of BLAP75 to Topo IIIα so as to assess the functional significance of protein-protein interactions in the BTB complex. The results and material reported herein should be valuable for the continuing dissection of the BLM-dependent means of HR regulation, genome maintenance, and tumor suppression.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmids—The bacterial expression plasmid pGEX-BLAP75-His6, harboring the BLAP75 cDNA with an N-terminal GST tag and a C-terminal His6 tag, has been described (17). GST fusion fragments of BLAP75 were constructed as follows. BLAP75-N (residues 1–211), BLAP75-N150 (residues 1–150), and BLAP75-NM (residues 1–424) were generated using QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene) to insert stop codons into the BLAP75 coding region of pGEX-BLAP75-His6. DNA fragments encoding BLAP75-MC (residues 212–625) and BLAP75-C (residues 425–625) were amplified from pGEX-BLAP75-His6 by PCR and cloned into the EcoRI and XhoI sites of the pGEX-6P1 vector (GE Healthcare) to add a GST tag to the N-terminal end of these BLAP75 fragments. BLAP75-M (residues 212–424) was generated using QuikChange mutagenesis to insert a stop codon into the BLAP75-MC coding frame in the expression vector. BLAP75 point mutants K166A, R176A, and K188A were generated from pGEX-BLAP75-His6 by QuikChange mutagenesis. The oligonucleotides used for the study were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies and are listed in supplemental Table 1.

DNA Substrates—The φX174 viral (+-strand and replicative form I DNA (∼90% supercoiled) were purchased from Invitrogen. All the oligonucleotides were purified from 12% denaturing polyacrylamide gels containing 8 m urea prior to use. The HJ (four-way X junction) substrate was prepared by annealing oligonucleotides as described (11, 23, 24). The dHJ substrate was prepared by hybridizing and ligating two partially complementary oligonucleotides as described (9, 17, 25).

Expression and Purification of BLAP75 and Its Variants—Escherichia coli Rosetta cells (Novagen) harboring plasmids that express GST-tagged fragments of BLAP75 were treated with 0.2 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-d-galactopyranoside for 18 h at 16 °C to induce protein expression as described (17). Cells were harvested by centrifugation and stored at –80 °C. All the subsequent steps were carried out at 4 °C. Extract from 10 g of cell paste (from 3 liters of culture) was prepared by sonication in 50 ml of cell breakage buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5; 600 mm KCl; 20% sucrose; 0.5 mm EDTA; 0.01% Igepal; 1 mm DTT; protease inhibitors aprotinin, chymostatin, leupeptin, and pepstatin A at 3 μg/ml each; and 1 mm phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride). The crude lysate was clarified by ultracentrifugation (90 min at 100,000 × g) and then mixed with 1 ml of glutathione-Sepharose (GE Healthcare) for 2 h. After washing the matrix with 10 ml each of K buffer (20 mm KH2PO4, pH 7.4, 10% glycerol, 0.5 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 0.01% Igepal, and protease inhibitors) containing 800 mm and 150 mm KCl, the bound proteins were eluted with 20 mm glutathione in K buffer containing 150 mm KCl. Peak fractions were pooled and applied directly onto a 1-ml Source Q column (GE Healthcare), which was washed with 10 ml of K buffer containing 150 mm KCl and then eluted with a 12-ml gradient of 150–850 mm KCl in K buffer. The peak fractions were pooled and loaded onto a 1-ml macro-hydroxyapatite column, which was eluted with a 10-ml gradient of 0–400 mm KH2PO4 in K buffer. Peak fractions were pooled and concentrated to 0.1 ml in a YM-30 Centricon device (Millipore), diluted to 2 ml with K buffer containing 500 mm KCl, and reconcentrated to 0.1 ml. Between 200 and 500 μgof nearly homogeneous protein was obtained for each GST-tagged BLAP75 variant. The concentrated proteins were divided into small aliquots and stored at –80 °C. Protein concentration was determined by densitometric comparison of multiple loadings of the purified proteins against known amounts of bovine serum albumin and β-galactosidase in a Coomassie Blue-stained polyacrylamide gel.

The wild-type and K166A, R176A, and K188A mutant forms of GST-tagged BLAP75 were expressed and purified using our published procedure (17). The concentration of these proteins was determined as above.

Purification of Other Proteins—Recombinant His6-tagged BLM and His6-tagged Topo IIIα were expressed in yeast and E. coli, respectively, and purified following our published procedures (11). The concentration of these proteins was determined as above.

GST Pulldown Assay—For GST pulldown experiments, GST-tagged BLAP75 or BLAP75 variant (3.5 μg each) was incubated with BLM or Topo IIIα (3.5 μg each) in 20 μl of K buffer containing 150 mm KCl at 4 °C for 10 min. The protein solutions were gently mixed with 5 μl of glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare) for 30 min at 4 °C. After washing the beads twice with 30 μl of K buffer containing 150 mm KCl, the bound proteins were eluted with 20 μl of SDS-PAGE sample loading buffer. The supernatant, wash, and SDS eluate (10 μl each) were resolved by 10% SDS-PAGE, and proteins were stained with Coomassie Blue. In Fig. 5D, Topo IIIα was detected by immunoblotting using anti-Topo IIIα antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

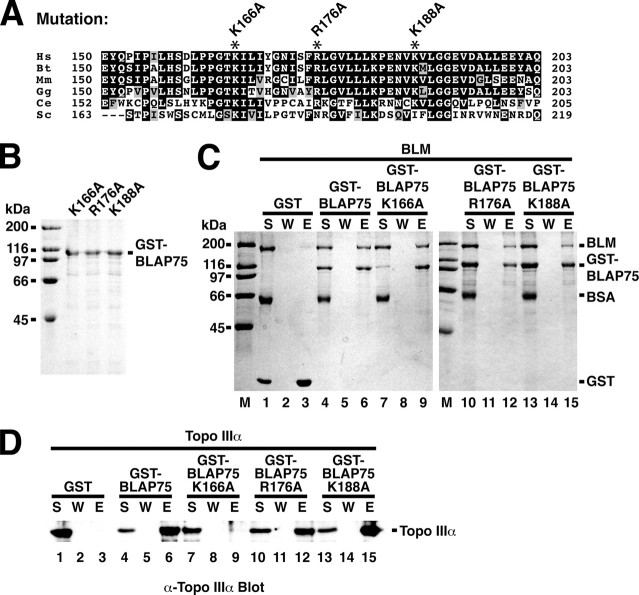

FIGURE 5.

BLAP75 K166A is defective in Topo IIIα interaction. A, shown is a sequence alignment of the N-terminal region of the BLAP75 family of proteins from multiple eukaryotic species. The abbreviations and accession numbers are as follows: Homo sapiens (Hs; NP_079221), Bos taurus (Bt; XP_590443), Mus musculus (Mm; NP_083180), Gallus gallus (Gg; NP_001026783), Caenorhabditis elegans (Ce; NP_741607), and S. cerevisiae (Sc; NP_015301). B, purified GST-BLAP75 K166A, GST-BLAP75 R176A, and GST-BLAP75 K188A proteins (1 μg each) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and staining with Coomassie Blue. C and D, GST-BLAP75, GST-BLAP75 K166A, GST-BLAP75 R176A, GST-BLAP75 K188A, or GST was incubated with BLM (C) or Topo IIIα (D), and protein complexes were captured on glutathione-Sepharose beads. The reaction supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining (C) or immunoblotting with anti-Topo IIIα antibodies (D). BSA, bovine serum albumin.

DNA Binding Assay—BLAP75 and the BLAP75 fragments (amount as indicated) were incubated at 37 °C with either the φX174 viral (+-strand or φX174 replicative form DNA linearized with ApaLI in 12.5 μl of reaction buffer (25 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 2 mm MgCl2, 60 mm KCl, 1 mm DTT, and 100 μg/ml bovine serum albumin). After 20 min, the reaction mixtures were resolved in 0.7% agarose gels, and the DNA species was visualized by staining with ethidium bromide. Where indicated, reactions were deproteinized by treatment with SDS and proteinase K (0.2% and 0.5 mg/ml, respectively) at 37 °C for 3 min prior to gel analysis.

dHJ Dissolution Assay—BLM (10 nm) was incubated with Topo IIIα (120 nm) and BLAP75 or BLAP75 variant (amount as indicated) for 10 min on ice in 11.5 μl of reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.8, 1 mm DTT, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 200 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, 2 mm ATP, 80 mm KCl, and an ATP-regenerating system consisting of 10 mm creatine phosphate and 50 μg/ml creatine kinase), followed by the incorporation of the dHJ substrate (1.2 nm) in 1 μl of water. After a 5-min incubation at 37 °C, 2 μl of 1% SDS and 0.5 μl of proteinase K (10 μg/μl stock) were added to the reaction mixtures, followed by a 3-min incubation at 37 °C. The deproteinized reactions were mixed with an equal volume of sample loading buffer (20 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 50% glycerol, and 0.08% orange G) containing 50% urea, incubated at 95 °C for 3 min, and resolved in an 8% polyacrylamide gel containing 20% formamide and 8 m urea in Tris acetate/EDTA buffer at 55 °C.

HJ Unwinding Assay—Combinations of BLM (10 nm), Topo IIIα (120 nm), and BLAP75 or BLAP75 variant (amount as indicated) were incubated on ice for 10 min in 9.5 μl of reaction buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 1 mm DTT, 2 mm ATP, 0.8 mm MgCl2, 100 mm KCl, 200 μg/ml bovine serum albumin, and the ATP-regenerating system described above). Following the addition of the radiolabeled HJ substrate (0.5 nm) in 0.5 μl of water, the reactions were incubated for an additional 10 min at 37 °C. After treatment with SDS and proteinase K as above, the deproteinized reaction mixtures were resolved in 10% native polyacrylamide gels in Tris acetate/EDTA buffer.

RESULTS

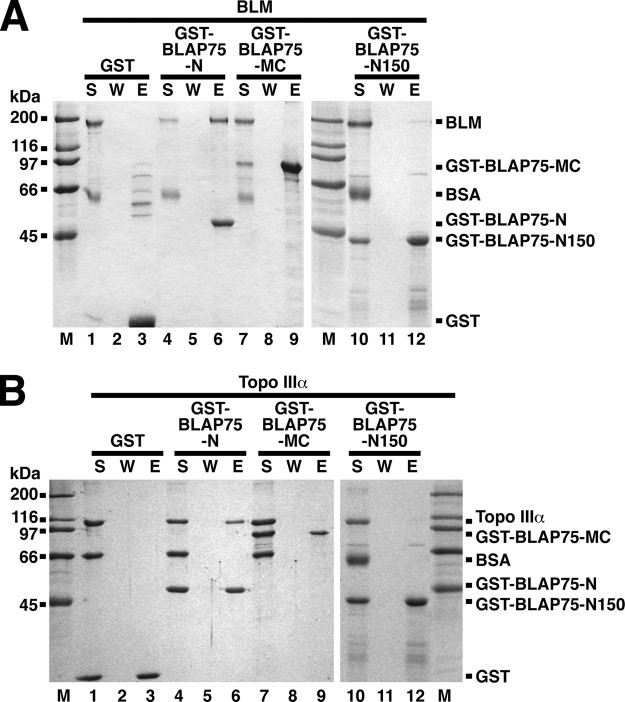

Isolation of the BLM and Topo IIIα Interaction Domains—Sequence analysis of BLAP75 has identified conserved domains in the N- and C-terminal regions, with the N-terminal portion harboring the first 200 or so residues being most similar to the 241-amino acid yeast Rmi1 protein (16, 20). Using this information, we divided BLAP75 into three fragments: BLAP75-N (residues 1–211), BLAP75-M (residues 212–424), and BLAP75-C (residues 425–625). To facilitate the purification of these BLAP75 fragments and subsequent analyses, they were each fused to GST, as depicted in Fig. 1A. The three GST-BLAP75 fusion proteins were expressed in E. coli and purified to near homogeneity by a multi-step purification scheme that incorporates the use of glutathione-Sepharose (which binds the GST portion of the fusion proteins) as an affinity step (Fig. 1, B and C). Following the same strategy, we also expressed and purified GST fusion proteins harboring combinations of the N and M fragments (residues 1–424 of BLAP75, termed BLAP75-NM) and the M and C fragments (residues 212–625 of BLAP75, termed BLAP75-MC) (Fig. 1). To determine which of the BLAP75 fragments possess the BLM- and Topo IIIα-binding domains, we incubated each of the GST-BLAP75 fusion proteins with BLM or Topo IIIα and then used glutathione-Sepharose beads to capture any protein complex that might have formed. After washing with buffer, the BLAP75 polypeptides and associated proteins were eluted from the glutathione-Sepharose beads by treatment with SDS and then analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Coomassie Blue staining. The results show that both BLM and Topo IIIα bound BLAP75-N (Fig. 2, A and B) and BLAP75-NM (data not shown), but not BLAP75-MC (Fig. 2, A and B), BLAP75-M, or BLAP75-C (data not shown).

FIGURE 2.

The N-terminal region of BLAP75 mediates interaction with BLM and Topo IIIα. GST-BLAP75-N, GST-BLAP75-MC, GST-BLAP75-N150, or GST was incubated with BLM (A) or Topo IIIα (B), and protein complexes were captured on glutathione-Sepharose beads. The reaction supernatant (S), wash (W), and SDS eluate (E) were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with Coomassie Blue staining. BSA, bovine serum albumin.

To further delineate the BLM and Topo IIIα interaction domains, the BLAP75-N fragment was subdivided into a GST-tagged BLAP75-N150 fragment (residues 1–150) (Fig. 1A). The purified GST fusion polypeptide was incubated separately with BLM and with Topo IIIα and then with glutathione-Sepharose beads. After washing with buffer, the beads were treated with SDS and analyzed as above. The results revealed no significant binding of BLAP75-N150 to either BLM (Fig. 2A, lane 12) or Topo IIIα (Fig. 2B, lane 12). Taken together, these data provide strong evidence that the region between amino acid residues 150 and 211 of the BLAP75 protein is involved in BLM and Topo IIIα binding. Consistent with this premise, changing a highly conserved residue (Lys166) in BLAP75 ablates its ability to interact with Topo IIIα (see below).

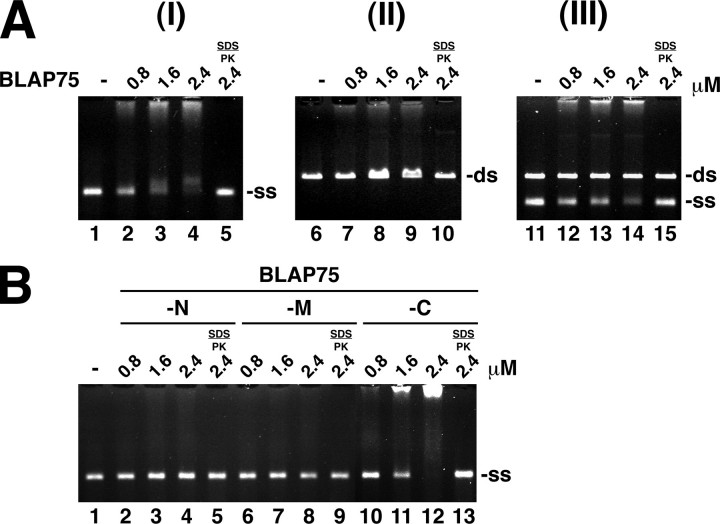

DNA Binding Activity Resides in the C-terminal Region of BLAP75—Both BLAP75 and its yeast orthologue Rmi1 possess a DNA binding activity (18, 20, 22). In our work, a DNA mobility shift assay that employs the φX174 viral (+-strand and the linear replicative form dsDNA as substrates was used to test DNA binding capability of BLAP75. After incubating increasing amounts of purified BLAP75 with the DNA substrates, the reaction mixtures were resolved in agarose gels, followed by staining with ethidium bromide to visualize DNA. As shown in Fig. 3A, BLAP75 bound ssDNA in a protein concentration-dependent manner (panel I) but has little affinity for dsDNA (panel II). As expected, when we incubated BLAP75 with the mixture of ssDNA and dsDNA, it bound the ssDNA preferentially (Fig. 3A, panel III). The treatment of BLAP75-ssDNA nucleoprotein complexes with SDS and proteinase K released intact DNA, indicating the absence of a nuclease activity.

FIGURE 3.

DNA binding is mediated through the C-terminal region of BLAP75. A, GST-BLAP75 (amount in μm as indicated) was incubated with φX174 ssDNA (12 μm nucleotides) (ss; panel I), linear φX174 dsDNA (12 μm base pair) (ds; panel II), or both the ssDNA and dsDNA (panel III) for 15 min at 37 °C and then analyzed in a 0.7% agarose gel with ethidium bromide staining. PK, proteinase K. B, GST-BLAP75-N, GST-BLAP75-M, and GST-BLAP75-C (amount in μm as indicated) were incubated with φX174 ssDNA (12 μm nucleotides) for 15 min at 37 °C and analyzed as above. Where indicated, the nucleoprotein complex was treated with 0.2% SDS and 0.5 mg/ml proteinase K at 37 °C for 5 min before analysis.

To determine which portion of BLAP75 is involved in DNA binding, we evaluated the capacity of the various purified BLAP75 fragments to interact with φX174 ssDNA. The results show that BLAP75-C was just as adept as the full-length BLAP75 protein in shifting the DNA substrate (Fig. 3, compare A (panel I) and B). Importantly, no significant DNA binding by BLAP75-N, BLAP75-M (Fig. 3B), or BLAP75-NM (data not shown) was observed. As expected, BLAP75-MC was as proficient as the full-length protein and the BLAP75-C fragment in DNA binding (data not shown). Taken together, the results establish that the DNA-binding domain resides within the C-terminal third of BLAP75.

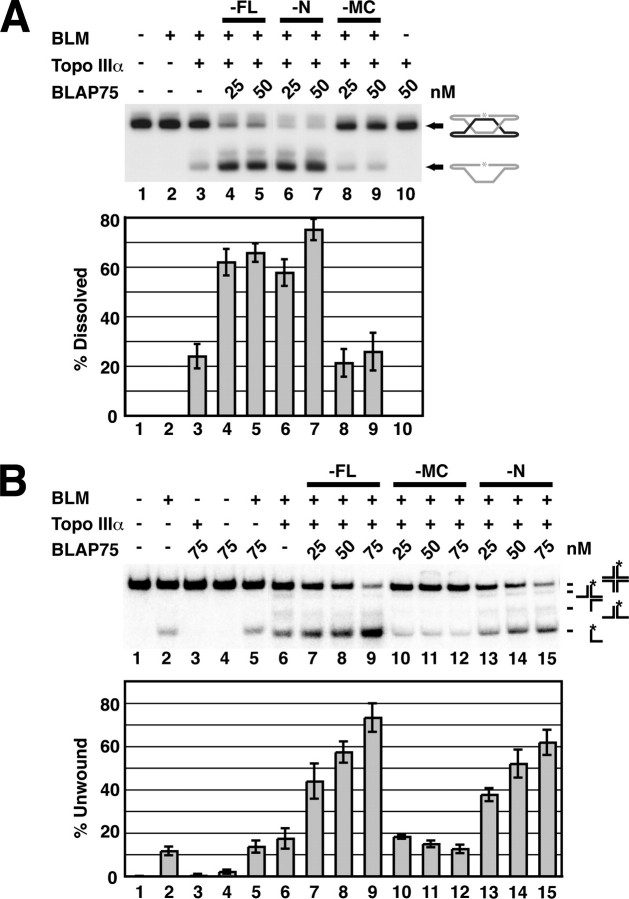

Enhancement of dHJ Dissolution by BLAP75-N—Results published by our group (17) and Hickson and co-workers (18) have shown that BLAP75 greatly enhances the dHJ dissolution reaction mediated by the BLM-Topo IIIα pair. We asked whether any of the BLAP75 fragments (N, M, C, NM, or MC) can support efficient dHJ dissolution. For this, a radiolabeled dHJ substrate, constructed as described (9, 17, 25), was incubated with the various purified BLAP75 fragments, and the dissolution products were resolved in a polyacrylamide gel under denaturing conditions and then visualized by phosphorimaging analysis (9, 17). As reported before, dHJ dissolution catalyzed by BLM-Topo IIIα was strongly enhanced by BLAP75 (Fig. 4A). Interestingly, the same level of dHJ dissolution was achieved upon substituting the full-length BLAP75 protein with either BLAP75-N (Fig. 4A, lanes 6 and 7) or BLAP75-NM (data not shown). In sharp contrast, BLM-Topo IIIα-mediated dHJ dissolution was completely refractory to BLAP75-MC (Fig. 4A, lane 8 and 9), BLAP75-M, and BLAP75-C (data not shown). Taken together, the results indicate that the BLAP75-N fragment is as proficient in promoting dHJ dissolution by BLM-Topo IIIα as is full-length BLAP75. That a specific interaction of BLAP75 with the BLM-Topo IIIα complex is critical for functional synergy to occur is bolstered by the isolation and characterization of a Topo IIIα interaction-defective BLAP75 mutant (see below).

FIGURE 4.

Enhancement of dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding by BLAP75-N. Combinations of BLM, Topo IIIα, full-length (FL) BLAP75, BLAP75-N, and BLAP75-MC were examined for dHJ dissolution (A) and for HJ unwinding activity (B). The means ± S.E. from three or more independent experiments are presented in the histograms.

Enhancement of HJ Dissociation by the BLAP75-N Fragment—Aside from up-regulating the dHJ dissolution function of the BLM-Topo IIIα complex, BLAP75 also works in conjunction with Topo IIIα to strongly stimulate the ability of BLM to dissociate a DNA substrate that harbors a HJ (11). We asked whether enhancement of BLM-mediated HJ unwinding occurs with any of the BLAP75 fragments, with the prediction that the N and NM fragments, but not the M, C, or MC fragment, possess such an attribute. The results show that HJ unwinding by variants of the BTB complex harboring the BLAP75-N fragment (Fig. 4B, lanes 13–15) or BLAP75-NM fragment (data not shown) was as efficient as with the wild-type BTB complex, whereas BLAP75-MC (lanes 10–12), BLAP75-M, or BLAP75-C (data not shown) was inactive in this regard.

Isolation of a BLAP75 Point Mutant Defective in Topo IIIα Interaction—The results presented above indicate that the BLM- and Topo IIIα-binding motifs likely reside between BLAP75 amino acid residues 150 and 211. We wished to further delimit the BLAP75 sequences responsible for mediating the interactions with BLM and Topo IIIα and to ascertain the significance of these protein-protein interactions with regard to the functional attributes of the BTB complex. We therefore used site-directed mutagenesis to change three of the conserved residues in the BLAP75 region that we know is indispensable for BLM and Topo IIIα interactions, with the premise that these mutations might compromise the interaction of BLAP75 with either BLM or Topo IIIα. Specifically, we made alanine substitutions of the highly conserved lysine 166, arginine 176, and lysine 188 residues (Fig. 5A). The three GST-tagged BLAP75 variants (K166A, R176A, and K188A) were purified to near homogeneity using the procedure that we had originally devised for the wild-type protein (Fig. 5B). During purification, all three BLAP75 variants behaved like the wild-type protein chromatographically, and a yield of these variants similar to that of the wild-type counterpart was obtained (data not shown).

We tested the BLAP75 variants for the ability to associate with BLM and Topo IIIα by GST pulldown. As shown in Fig. 5C, all three BLAP75 variants were proficient in interaction with BLM. Interestingly, Topo IIIα interaction was abolished by the BLAP75 K166A mutation (Fig. 5D, lane 9), with the BLAP75 R176A and BLAP75 K188A variants being as capable of Topo IIIα binding as the wild-type protein (lanes 12 and 15).

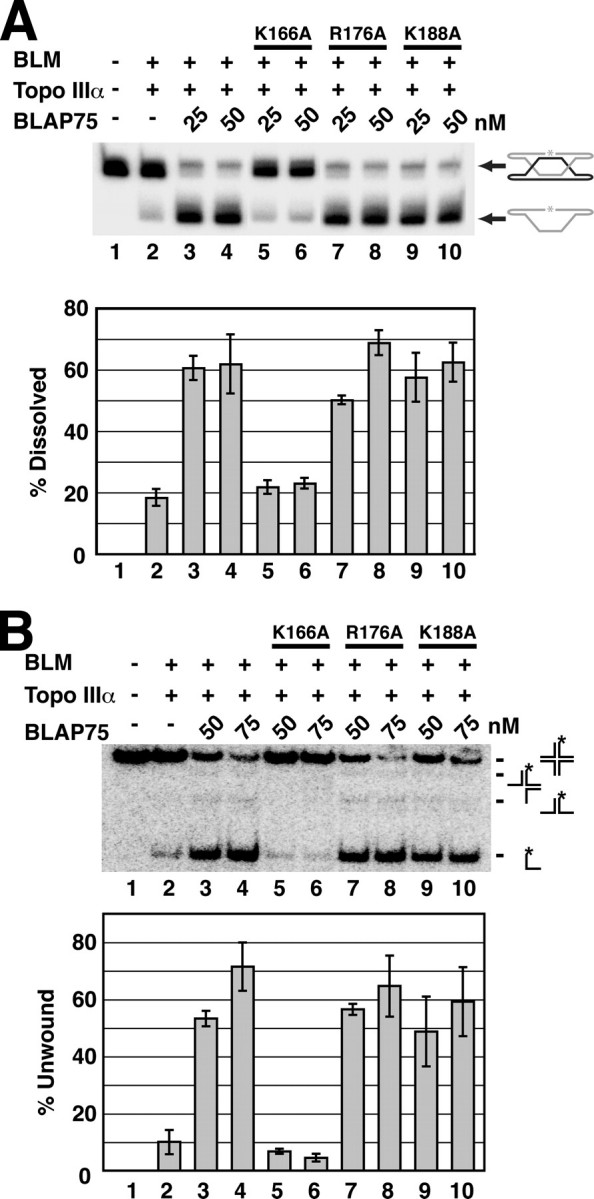

Functional Integrity of the BTB Complex Relies on BLAP75-Topo IIIα Interaction—We asked whether the BLAP75 K166A mutant, defective in Topo IIIα interaction, is impaired in the ability to functionally synergize with BLM-Topo IIIα in the processing of HJ intermediates. We first performed dHJ dissolution experiments using the combination of BLM-Topo IIIα and BLAP75 K166A, BLAP75 R176A, or BLAP75 K188A. The results show that dHJ dissolution by BLM-Topo IIIα was refractory to BLAP75 K166A (Fig. 6A, lanes 5 and 6), whereas BLAP75 R176A and BLAP75 K188A were as proficient as wild-type BLAP75 in promoting the dissolution reaction (lanes 7–10). Likewise, although the BLAP75 R176A and BLAP75 K188A variants were as adept as wild-type BLAP75 in enhancing the dissociation of the HJ substrate by BLM-Topo IIIα (Fig. 6B, lanes 7–10), the K166A variant was inactive (lanes 5 and 6). Taken together, the results indicate that the BLAP75-Topo IIIα interaction is indispensable for BTB complex functions.

FIGURE 6.

BLAP75 K166A is defective in dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding. Combinations of BLM, Topo IIIα, BLAP75, BLAP75 K166A, BLAP75 R176A, and BLAP75 K188A were examined for dHJ dissolution (A) and HJ unwinding activity (B). The means ± S.E. from three or more independent experiments are presented in the histograms.

DISCUSSION

Biochemical studies with highly purified BLAP75 have shown that it possesses a DNA binding activity (18), physically associates with both BLM and Topo IIIα (17, 18), and enhances the HJ unwinding and dHJ dissolution functions of the BLM-Topo IIIα pair (11, 17, 18). In the present study, we have conducted biochemical mapping to delineate the domains in BLAP75 that contribute to its known interactions with protein partners and with DNA. Specifically, with the use of a series of polypeptides spanning different portions of BLAP75, we have shown that 1) the N-terminal third of the protein, which exhibits the highest degree of conservation among BLAP75 orthologues, including the S. cerevisiae Rmi1 protein (Fig. 5A) (16, 20), is as capable as the full-length protein in BLM and Topo IIIα association but is devoid of DNA binding activity; 2) the middle portion of the protein lacks the ability to bind BLM, Topo IIIα, or DNA; and 3) the C-terminal third of the protein is as adept as the full-length protein in DNA binding but does not interact with BLM or Topo IIIα (Fig. 7). Thus, even though it has been postulated that the DNA binding attribute of BLAP75 may derive from its putative N-terminal OB-fold (16, 18), our new results show that this motif plays little or no role in DNA binding. Rather, our results provide evidence to implicate the OB-fold in the mediation of complex formation of BLAP75 with BLM and Topo IIIα. This premise is bolstered by our discovery that mutation of the highly conserved lysine 166 residue (equivalent to lysine 176 in S. cerevisiae Rmi1 protein) within the putative OB-fold ablates Topo IIIα interaction. It will be particularly relevant to ask whether lysine 176 in S. cerevisiae Rmi1 is similarly critical for Top3 interaction (19, 22).

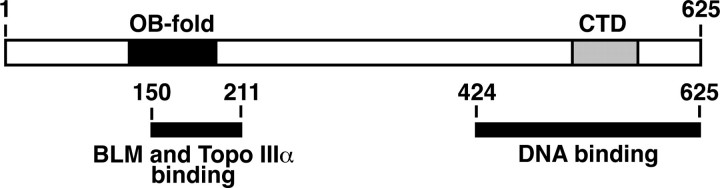

FIGURE 7.

Schematic representation of the domain structure of the BLAP75 protein. The black box represents the predicted OB-fold domain, whereas the gray box represents the conserved C-terminal domain (CTD). Numbers refer to amino acid residue numbers/positions in BLAP75.

We have shown that within the context of the BTB complex, the BLAP75-N fragment is as proficient as the full-length protein in promoting dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding, despite being devoid of DNA binding activity. Thus, the DNA binding activity of BLAP75 is apparently not needed for the functional integrity of the BTB complex with regard to the in vitro processing of the HJ and dHJ structures by unwinding and dissolution, respectively. Wu et al. (18) showed previously that BLAP75 enhances the binding of Topo IIIα to the dHJ, and they suggested that the DNA binding activity of BLAP75 is germane for Topo IIIα recruitment to this HR intermediate. Likewise, Rmi1 stimulates the binding of Top3 to ssDNA (22). Because BLAP75-N is sufficient for the promotion of dHJ dissolution and HJ unwinding, the ability of BLAP75/Rmi1 to target Topo IIIα/Top3 to DNA substrates does not seem to be dependent on the DNA binding activity of the former. It remains possible that, in vivo, DNA binding by BLAP75 helps ensure the timely recruitment of the BTB complex and its S. cerevisiae equivalent (Rmi1) to various DNA substrates or the retention of these protein complexes on the bound substrates.

Our study has not uncovered any notable functional attribute of the middle portion of BLAP75. However, as both the middle and C-terminal portions of BLAP75 are absent in S. cerevisiae Rmi1 protein, it seems reasonable to suggest that this region has evolved to perform specific cellular functions in higher eukaryotes, perhaps serving to mediate interactions with other DNA damage repair and response proteins critical for accomplishing the biological reactions that are reliant on the BTB complex. For example, the BTB complex co-immunoprecipitates with components of the Fanconi anemia protein complex from HeLa cell extracts (15). Moreover, genetic studies in chicken DT40 cells have uncovered a functional relationship between BLM and FANCC in the suppression of sister chromatid exchanges (26). It is possible that BLAP75 acts to link the BTB-mediated HR regulatory function to the elimination of DNA cross-links via the Fanconi anemia pathway.

The process of dHJ dissolution is thought to involve BLM-mediated convergent branch migration of the pair of HJs in this DNA structure to create a hemicatenane intermediate that is then resolved by the strand passage activity of Topo IIIα. Although E. coli Top3 protein can cooperate with BLM in the dHJ dissolution reaction, unlike the BLM-Topo IIIα pair, the mixture of BLM and E. coli Top3 is refractory to the stimulatory effect of BLAP75 (9, 11). Likewise, the BLAP75-Topo IIIα complex, but not the mixture of BLAP75 and E. coli Top3, is able to enhance the HJ unwinding activity of BLM (11). Affinity pull-down assays indicated that Top3 does not interact with either BLM or BLAP75 (11). Taken together, the available data strongly suggest that specific protein-protein interactions involving the three constituents of the BTB complex (viz. BLM, Topo IIIα, and BLAP75) are indispensable for the functional integrity of the complex. The fact that the BLAP75 K166A mutant, specifically deficient in Topo IIIα binding, is unable to promote dHJ dissolution or HJ unwinding is fully congruent with this premise.

Recent results from the Mazin laboratory (10) have shown an ability of BLM to dismantle the Rad51 presynaptic filament. Interestingly, another member of the RecQ family, RECQ5, can also displace Rad51 from ssDNA (27). This activity of BLM and RECQ5 is thought to be important for suppressing spurious HR events and limiting the formation of crossovers that can compromise genome integrity. It remains to be determined whether the association with Topo IIIα and BLAP75 also modulates the Rad51 presynaptic filament disruptive activity of BLM. The results and research material described in this work should facilitate future efforts aimed at answering this question.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Elaine Lee and Felicia Barriga for help in constructing the BLAP75 mutants.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Research Grants ES015252 and ES015632 (to P. S.) and R01 HL084082 (to A. R. M.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table 1.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: HR, homologous recombination; Topo, topoisomerase; HJ, Holliday junction; dHJ, double Holliday junction; OB, oligonucleotide binding; GST, glutathione S-transferase; DTT, dithiothreitol; ssDNA, single-stranded DNA; dsDNA, double-stranded DNA.

References

- 1.German, J. (1993) Medicine (Baltimore) 72393 –406 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chaganti, R. S., Schonberg, S., and German, J. (1974) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 714508 –4512 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kuhn, E. M., and Therman, E. (1986) Cancer Genet. Cytogenet. 221 –18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellis, N. A., Groden, J., Ye, T. Z., Straughen, J., Lennon, D. J., Ciocci, S., Proytcheva, M., and German, J. (1995) Cell 83655 –666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheok, C. F., Bachrati, C. Z., Chan, K. L., Ralf, C., Wu, L., and Hickson, I. D. (2005) Biochem. Soc. Trans. 331456 –1459 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bachrati, C. Z., Borts, R. H., and Hickson, I. D. (2006) Nucleic Acids Res. 342269 –2279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Karow, J. K., Constantinou, A., Li, J. L., West, S. C., and Hickson, I. D. (2000) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 976504 –6508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.van Brabant, A. J., Ye, T., Sanz, M., German, J. L., III, Ellis, N. A., and Holloman, W. K. (2000) Biochemistry 3914617 –14625 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu, L., and Hickson, I. D. (2003) Nature 426870 –874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bugreev, D. V., Yu, X., Egelman, E. H., and Mazin, A. V. (2007) Genes Dev. 213085 –3094 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bussen, W., Raynard, S., Busygina, V., Singh, A. K., and Sung, P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28231484 –31492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hickson, I. D. (2003) Nat. Rev. Cancer 3169 –178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sung, P., and Klein, H. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7739 –750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adams, M. D., McVey, M., and Sekelsky, J. J. (2003) Science 299265 –267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meetei, A. R., Sechi, S., Wallisch, M., Yang, D., Young, M. K., Joenje, H., Hoatlin, M. E., and Wang, W. (2003) Mol. Cell. Biol. 233417 –3426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin, J., Sobeck, A., Xu, C., Meetei, A. R., Hoatlin, M., Li, L., and Wang, W. (2005) EMBO J. 241465 –1476 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Raynard, S., Bussen, W., and Sung, P. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 28113861 –13864 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu, L., Bachrati, C. Z., Ou, J., Xu, C., Yin, J., Chang, M., Wang, W., Li, L., Brown, G. W., and Hickson, I. D. (2006) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1034068 –4073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang, M., Bellaoui, M., Zhang, C., Desai, R., Morozov, P., Delgado-Cruzata, L., Rothstein, R., Freyer, G. A., Boone, C., and Brown, G. W. (2005) EMBO J. 242024 –2033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mullen, J. R., Nallaseth, F. S., Lan, Y. Q., Slagle, C. E., and Brill, S. J. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 254476 –4487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Theobald, D. L., Mitton-Fry, R. M., and Wuttke, D. S. (2003) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 32115 –133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen, C. F., and Brill, S. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28228971 –28979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Osman, F., Dixon, J., Barr, A. R., and Whitby, M. C. (2005) Mol. Cell. Biol. 258084 –8096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Macris, M. A., Krejci, L., Bussen, W., Shimamoto, A., and Sung, P. (2006) DNA Repair 5172 –180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fu, T. J., Tse-Dinh, Y. C., and Seeman, N. C. (1994) J. Mol. Biol. 23691 –105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hirano, S., Yamamoto, K., Ishiai, M., Yamazoe, M., Seki, M., Matsushita, N., Ohzeki, M., Yamashita, Y. M., Arakawa, H., Buerstedde, J. M., Enomoto, T., Takeda, S., Thompson, L. H., and Takata, M. (2005) EMBO J. 24418 –427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu, Y., Raynard, S., Sehorn, M. G., Lu, X., Bussen, W., Zheng, L., Stark, J. M., Barnes, E. L., Chi, P., Janscak, P., Jasin, M., Vogel, H., Sung, P., and Luo, G. (2007) Genes Dev. 213073 –3084 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.