Abstract

PDHK2 is a mitochondrial protein kinase that phosphorylates pyruvate dehydrogenase complex, thereby down-regulating the oxidation of pyruvate. Here, we present the crystal structure of PDHK2 bound to the inner lipoyl-bearing domain of dihydrolipoamide transacetylase (L2) determined with or without bound adenylyl imidodiphosphate. Both structures reveal a PDHK2 dimer complexed with two L2 domains. Comparison with apo-PDHK2 shows that L2 binding causes rearrangements in PDHK2 structure that affect the L2- and E1-binding sites. Significant differences are found between PDHK2 and PDHK3 with respect to the structure of their lipoyllysine-binding cavities, providing the first structural support to a number of studies showing that these isozymes are markedly different with respect to their affinity for the L2 domain. Both structures display a novel type II potassium-binding site located on the PDHK2 interface with the L2 domain. Binding of potassium ion at this site rigidifies the interface and appears to be critical in determining the strength of L2 binding. Evidence is also presented that potassium ions are indispensable for the cross-talk between the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites of PDHK2. The latter is believed to be essential for the movement of PDHK2 along the surface of the transacetylase scaffold.

Fully assembled mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC)3 has a molecular weight of approximately 10 million daltons and consists of multiple copies of three enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1), dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase (E2), and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (E3) (1). It catalyzes an oxidative decarboxylation of pyruvate with concomitant formation of acetyl-CoA and NADH (1).

In mammals, the activity of PDC is regulated by pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDHK). PDHK is an integral part of PDC bound to the E2 component (2). It catalyzes the phosphorylation of E1, causing inactivation of the entire complex (2). In humans and other mammalian species, PDHK is represented by at least four closely related protein kinases, which are remarkably different with respect to their activities, tissue distribution, and regulation (PDHK1, PDHK2, PDHK3, and PDHK4, respectively) (3–5). Cumulatively, four PDHK isozymes account for the short and long term regulation of mammalian PDC (6). The short term regulation of PDC reflects the effects of pyruvate, NAD+, CoA, acetyl-CoA, and NADH on the activities of PDHKs. In general, the products of the pyruvate dehydrogenase reaction (i.e. acetyl-CoA and NADH) activate PDHK, thus facilitating the phosphorylation and inactivation of PDC (6). In contrast, the substrates (pyruvate, NAD+, and CoA) inhibit PDHK activity and thereby promote reactivation of PDC catalyzed by pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (6). Of all metabolites, only pyruvate acts on PDHK directly (7). The effects of other metabolites are mediated by the reductive acetylation of the lipoyl residues of the inner lipoyl-bearing domains of E2 (L2), which serve as the docking sites for the attachment of the PDHK molecule to the complex (8, 9). The long term regulation of PDC occurs as a result of overexpression of PDHK2 and PDHK4 in starvation and diabetes (10), as well as overexpression of PDHK1 in hypoxia and, possibly, in cancer (11).

An important role played by PDHKs in the regulation of general metabolism prompted a number studies aimed at the structural characterization of this family of protein kinases (12–15). These studies revealed that PDHK consists of two domains that are almost equal in size: the amino-terminal domain assembled as a four-helix bundle (R domain) and the carboxyl-terminal domain folded as a mixed α/β sandwich (K domain) (12). The K domain carries the nucleotide-binding site and also provides the dimerization interface (12). The R domain harbors a number of binding sites for the synthetic inhibitors of PDHK activity, such as dichloroacetate (analog of pyruvate), AZ12, Nov3r, Pfz3, and AZD7545 (14). The active site of PDHK is presumably located on the interface between the two domains (16). Structural studies carried out on PDHK3 identified the location of the L2-binding site (13), which is built of the amino acids furnished by the R domain of one PDHK3 subunit and by the carboxyl-terminal tail of the K domain provided by another subunit (so-called cross-arm (14) or the C-tail (13, 15)). Interestingly, some of the PDHK inhibitors (i.e. AZ12, Nov3r, and AZD7545) appear to act by competing with L2 for PDHK binding (14, 15, 17).

Despite the great progress made in determination of the three-dimensional structures of PDHK isozymes, the molecular mechanisms responsible for the regulation of PDHK activity remain poorly understood. At least in part, this stems from the difficulties with crystallizing individual PDHKs, which creates a significant gap in the structural characterization of the conformational states of particular isozymes of PDHK. This study was undertaken in order to better understand the regulation of PDHK2. Here, we report the first three-dimensional structure of PDHK2 in a complex with L2. This structure provides new important insights into the molecular mechanisms responsible for the recognition of L2 and the effects of L2 on PDHK2 structure and kinase activity.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Vector Construction, Protein Expression, and Purification—Construction of the expression vectors for E1, E2-E3BP subcomplex, Escherichia coli lipoyl-protein ligase A, His6-L2 (amino acids Ser127–Ile214), GST-L2 (amino acids Ser127–Ile214), and PDHK2 was described elsewhere (5, 18–21). General conditions for the expression of E1, E2-E3BP subcomplex, PDHK2, His6-L2, and GST-L2 were described previously (18–21). PDHK2 was expressed following the established protocol (5). The plasmid directing the synthesis of molecular chaperonins GroEL and GroES was obtained as a generous gift from Dr. Anthony Gatenby (DuPont Central Research and Development, Wilmington, DE). Purification of E1, E2-E3BP subcomplex, PDHK2, His6-L2, and GST-L2 was described elsewhere (5, 18–21). The protein composition of each protein preparation was evaluated by SDS-PAGE analysis. Gels were stained with Coomassie R250. All preparations used in the present study were more than 90% pure.

Crystallization, Structure Determination, and Refinement— For crystallization experiments, the highly purified PDHK2 and L2 proteins made in buffer D (20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 50 mm KCl, 5 mm dithiothreitol, and 0.1 mm EDTA) were mixed together at a molar ratio of 1:2 and concentrated to a final protein concentration of 10 mg/ml. The crystals of PDHK2-L2 complex were obtained using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method by mixing 2 μl of concentrated PDHK2-L2 solution in buffer D with an equal volume of reservoir solution (0.1 m sodium acetate (pH 5.3) and 0.5 m sodium formate) and kept at 20 °C. The crystals grown under these conditions had a tetragonal shape and final size of 100 × 50 × 10 μm. The crystals of the PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p complex were obtained by soaking freshly made PDHK2-L2 crystals in a well solution containing 0.5 mm App(NH)p and 5 mm MgCl2 for 60 min. All crystals were serially transferred to the well solution containing 25% (v/v) glycerol and flash-frozen in liquid propane. Diffraction data were collected under cryogenic conditions on South East Regional Collaborative Access Team beamline 22-BM, or 22-ID, at SER-CAT at the Advanced Photon Source (Argonne, IL). Raw diffraction images were processed with HKL2000 (22).

The PDHK2-L2 structure was solved by molecular replacement using the program COMO (23). Molecular coordinates from the PDB entry 2btz were used as a search model (14). After rigid body refinement with REFMAC5 (24), in-place model rebuilding was carried out with the Phenix software package (25). This was followed by additional manual model building and real space refinement with COOT software (26). Refinement of the final model, including TLS refinement, was performed with REFMAC5 (24). The structure of the PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p complex was solved by molecular replacement using the PDHK2-L2 model. Density corresponding to App(NH)p was easily observed in difference maps. Placement and real space refinement of App(NH)p was carried out with COOT. The refinement was carried out as described for the PDHK2-L2 complex. Molecular graphics for structural representations were drawn by PyMol (DeLano Scientific LLC, Palo Alto, CA).

PDHK2 Activity Assay—General conditions for the phosphorylation assay based on incorporation of [32P]phosphate from [γ-32P]ATP into the α chain of the E1 component were described previously (18). Briefly, reactions were carried out at 37 °C in a final volume of 50 μl containing buffer A (20 mm potassium phosphate (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, 5 mm DTT, 2.0% (v/v) ethylene glycol), plus 0.54 mg/ml E1, 8 μg/ml kinase, or buffer B (20 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.5), 5 mm MgCl2, 50 mm NaCl, 5 mm DTT, 2.0% (v/v) ethylene glycol), plus 0.54 mg/ml E1, 8 μg/ml kinase. E2-E3BP complex was used at a final concentration of 0.46 mg/ml. After equilibration at 37 °C for 60 s, phosphorylation reactions were initiated by the addition of 200 μm [γ-32P]ATP (specific radioactivity of 100–200 cpm/pmol). After a 60-s incubation, 40-μl aliquots were quenched on Whatman 3MM filters presoaked in a solution of 24% (w/v) trichloroacetic acid, 0.2 m phosphoric acid, 2 mm sodium pyrophosphate, and 1 mm ATP. After extensive washing, the protein-bound radioactivity was determined by liquid scintillation counting. A negative control (minus PDHK2) was used to determine the nonspecific incorporation. All assays were conducted in triplicates. Effects of ADP were characterized using E1 component (0.54 mg/ml) reconstituted with E2-E3BP (0.46 mg/ml) as a substrate for PDHK2.

Pulldown Assay—Pulldown experiments were performed as described elsewhere (21). Briefly, 50 μl of a 50% (v/v) slurry of glutathione-Sepharose beads was placed in a Spin-X microcentrifuge filter device with a pore diameter of 0.22 μm (Corning Glass). Beads were washed three times with buffer A or buffer B. Equilibrated beads were incubated with GST-L2 protein (0.5 mg/ml) in 0.4 ml of buffer A or buffer B for 10 min. GST-L2-decorated glutathione-Sepharose beads were washed and incubated for 10 min with PDHK2 protein (0.2 mg/ml) prepared in 400 μl of buffer A or buffer B. After incubation, unbound PDHK2 was removed by centrifugation for 1 min at 6,000 × g followed by three consecutive washes in appropriate buffer. To elute bound proteins, 0.1 ml of buffer A or buffer B supplemented with 10 mm reduced glutathione was added to beads, and beads were incubated for 5 min at room temperature, followed by centrifugation at 6,000 × g for 1 min. Free and bound PDHK2 were analyzed using SDS-PAGE. Gels were stained with Coomassie R250. ATP and ADP were employed at a final concentration of 0.5 mm. The effects of different monovalent cations were examined using buffer C (40 mm MOPS-imidazole (pH 7.0), 2 mm MgCl2, and 2 mm DTT) supplemented with an appropriate salt at a final concentration of 50 mm.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)—ITC experiments were carried out essentially as described previously (17) using a MicroCal VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal, Northampton, MA). All titrations were performed at 30 °C. Prior to the binding experiment, PDHK2, L2, ATP, or ADP was made in buffer A or buffer B. In a typical experiment, the concentration of PDHK2 in the calorimeter cell was 20 μm. The concentration of L2 or appropriate nucleotide in the injection syringe was 250 μm and 1.0 mm, respectively. Five-μl injections were made with 240-s spacing. The heat change accompanying the addition of the buffer to PDHK2 and the heat of dilution of the ligands were subtracted from the raw results. The equilibrium association constants (Ka) and the molar heats of binding (ΔH) were obtained by nonlinear least-squares fitting of experimental data using a single-site binding model of the Origin software package (version 7.0) provided with the instrument (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). The affinities of PDHK2 for L2, ATP, or ADP are given as the dissociation constants (KD = 1/Ka). Higher protein concentrations were used in case of weak binding to achieve accurate determination of binding parameters.

Intrinsic Fluorescence Quenching—Steady state fluorescence spectra of PDHK2 were recorded at 20 °C in buffer A or buffer B made without DTT, using an ISS PC1 photon-counting spectrofluorometer equipped with an autotitrator (ISS, Inc., Champaign, IL) with a band pass of 1 mm on both the excitation and the emission monochromators. Samples were excited at 290 nm, and their fluorescence intensities were recorded at 352 nm. The titration experiments were conducted in standard (1 × 1-cm) cells containing protein samples of an initial volume of 2.0 ml. Nucleotides were added in 2- or 10-μl increments with constant stirring. PDHK2 was used in a concentration of 1.0 μm. The nonspecific fluorescence quenching was measured in the presence of increasing concentrations of AMP. The concentrations of ATP, ADP, and AMP were determined based on their absorbance coefficient at 259 nm (ε = 1.54 × 104 m-1 × cm-1). Data were transformed and analyzed using approaches described by Hiromasa and colleagues (7).

Statistical Analysis—The reported parameters represent the means ± S.D. obtained for at least three independent determinations. Statistical analysis was performed by an unpaired Student's t test. p < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

Other Assays—SDS-PAGE was carried out according to Laemmli (27). Protein concentrations were determined according to Lowry et al. (28) with bovine serum albumin as a standard. The extent of L2 lipoylation was examined following the procedure described by Quinn et al. (29); the lipoate content of all L2 constructs was greater than 90%.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

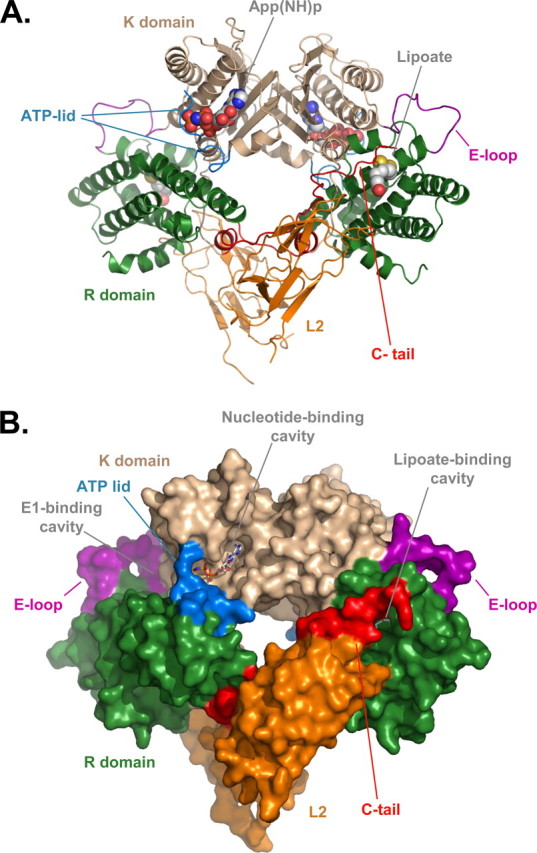

Structure of PDHK2-L2 and PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p Complexes—In this study, we determined the crystal structure of PDHK2 complexed with either L2 or L2 and App(NH)p at 2.3 and 2.6 Å resolution, respectively (Table 1). Both structures show the PDHK2 dimer bound to two L2 domains (Fig. 1). The R domain of L2-bound PDHK2 is composed of residues Ser12–Ala183, and the K domain encompasses residues His184–Tyr404. The fold of each domain is similar to that of apo-PDHK2 (14) with the exception of several regions that become ordered upon L2 and/or App(NH)p binding. The greatest ordering occurs in the residues of the C-tail of the K domain (Val393–Tyr404) that contribute to the L2-binding site of the PDHK2 molecule (Fig. 1). The binding of App(NH)p to the PDHK2-L2 complex causes additional ordering of the distal part of the ATP lid (residues Leu323–Gly327 of the K domain) that contributes to the binding of γ- and β-phosphates of the nucleotide substrate and forms the lid of the channel connecting the nucleotide- and E1-binding sites of PDHK2 (Fig. 1). Another region that undergoes the disorder-to-order transition is a loop that connects helices α7 and α8 (residues Gly178–Pro185, E-loop in Fig. 1). This loop forms the back wall of the E1-binding cavity (12, 13, 16). Its ordering might explain the greater affinity for E1 displayed by the complex-bound PDHK2 (30). Finally, the comparison of apo-PDHK2 and L2-bound PDHK2 structures shows little if any interdomain movement in the structure of L2-bound PDHK2, indicating that L2 binding per se does not cause any gross conformational changes in the PDHK2 molecule.

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement statistics

|

Parameters |

Values |

|

|---|---|---|

| PDHK2-L2 | PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p | |

| Data collectiona | ||

| Space group | P21 | P21 |

| Unit cell a, b, c (Å), β (degrees) | 71.38, 120.67, 71.46, 96.03 | 71.41, 121.63, 71.45, 97.29 |

| Resolution (Å) | 50-2.3 (2.38-2.30) | 50-2.61 (2.90-2.61) |

| Reflections (unique/total observed) | 50,400/167,468 | 32,881/70,711 |

| Completeness | 94.9 (73.3) | 90.6 (64.5) |

| 〈I〉/〈σ(I)〉 | 18.8 (3.2) | 20.3 (2.73) |

|

Rmerge

(%)b |

0.055 (0.269)

|

0.039 (0.290)

|

| Refinementa | ||

| Rwork (%)c | 20.7 | 22.0 |

| Rfree (%)c | 25.0 | 27.4 |

| Root mean square deviations | ||

| Bond length (Å) | 0.007 | 0.007 |

| Bond angle (degrees) | 1.009 | 1.089 |

Values in parentheses refer to data in the highest resolution shell unless otherwise indicated

Rmerge = ΣhklΣj|Ij – 〈I〉|/ = ΣhklΣjIj, where 〈I〉 is the mean intensity of j observations from reflection hkl and its symmetry equivalents

Rwork = Σhkl||Fo| – k|Fc||/Σhkl|Fo|. Rfree = Rwork for 5% of reflections that were omitted from refinement

FIGURE 1.

Three-dimensional structure of PDHK2-L2 complex. A, ribbon representation of PDHK2-L2 dimer with App(NH) bound to the nucleotide-binding pocket. K domains are shown in wheat and R domains are shown in green. The bound L2 domains are colored orange. C-tails are red, whereas ATP lids are cyan. The loop connecting helices α7 and α8 that undergoes the disorder-to-order transition upon L2 binding (E-loop) is colored purple. The lipoyl groups (CPK; C gray) and bound App(NH)p (CPK; C gray) are shown as space-filling models. B, space-filling representation of PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p complex. The color scheme is the same as in A. The lipoyl groups and App(NH)p are shown as stick models.

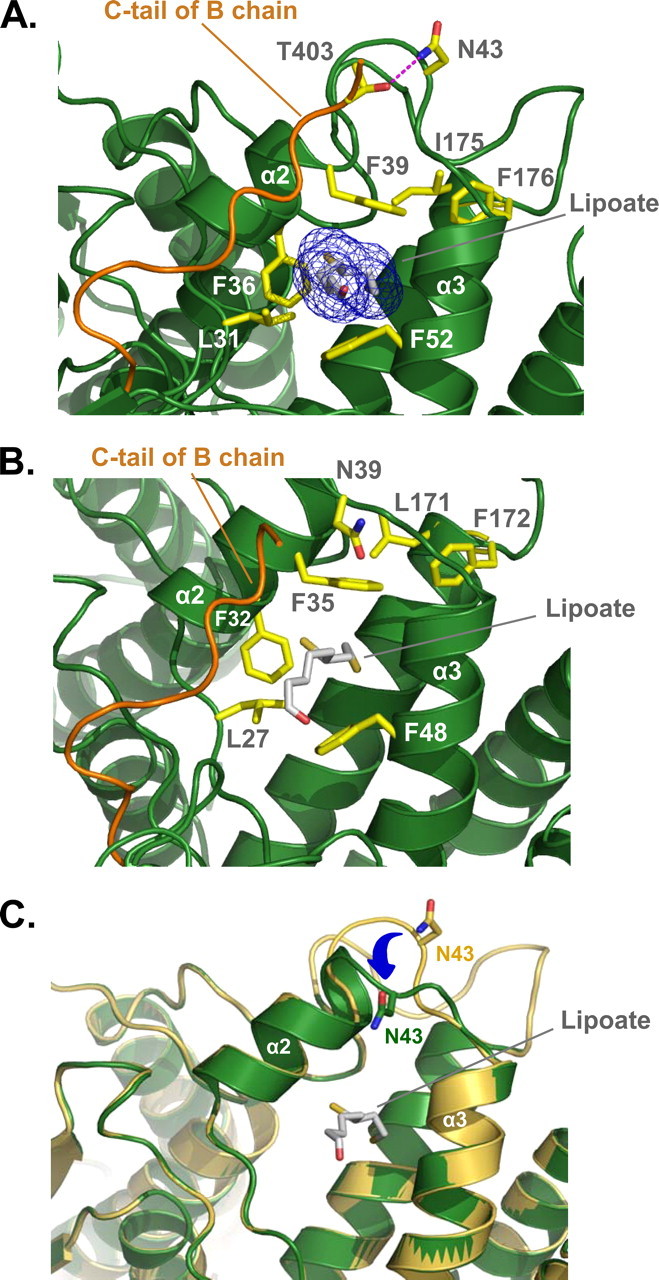

Conformation of the L2-binding Site—The L2-binding site of PDHK2 is built by the amino acids of the R domain and C-tail of one subunit of the PDHK2 dimer and by the amino acids of the far carboxyl end of the C-tail furnished by the neighboring subunit of the dimer (Fig. 1). As a result of this arrangement, each L2 domain interacts with both C-tails of the PDHK2 dimer. The amino acid residues of PDHK2 engaged in interactions with L2 are Phe26–Ser29, Gln55, Asn375–Ser377, Arg380, Ile385–Ala388, Val393–Glu397, and Lys399. The amino acid residues of L2 that form extensive contacts with PDHK2 are Ala139–Pro142, Glu153, Glu162–Leu165, Glu170–Thr175, Glu179, and Arg196. Some of these amino acid residues in PDHK2 and L2 were identified as indispensable for PDHK2-L2 interaction by site-directed mutagenesis (17). Interestingly, the affinity of PDHK2 for the L2 domain is almost 10-fold lower than that of PDHK3 (13, 20, 31). However, with the exception of Gln55, Ile385, Gln386, and Val393, the amino acids interfacing with the L2 domain are conserved between these proteins. This suggests that other factors account for the differences in L2 binding affinities between PDHK2 and PDHK3.

The lipoyllysine-binding cavity of PDHK2 is located on the tip of the R domain (Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 2A, it is shaped by the amino acids of helices α2 and α3, by the loop connecting these helices, and by the far carboxyl end of the C-tail provided by chain B (Lys399–Tyr404) of the neighboring subunit. The surface of the lipoyllysine-binding cavity is lined by the side chains of Leu31, Phe36, Phe39, Phe52, Ile175, and Phe176 that create the hydrophobic environment for the lipoate prosthetic group. Careful examination of the lipoyllysine-binding cavities in PDHK2 and PDHK3 (13) reveals significant differences in their structures (Figs. 2, A and B). The structured part of PDHK2 C-tail is longer than that of PDHK3. Consequently, it is engaged in additional interactions that have not been observed in the PDHK3 structure (13). The C-tail of PDHK2 forms very extensive contacts with the amino acids of the loop and helix α2. These interactions are further stabilized by the hydrogen bond between the side chains of Thr403 and Asn43 (Fig. 2A). This bonding network maintains the lipoyllysine-binding cavity of PDHK2 in a wide open state. In marked contrast, a large part of the C-tail in the PDHK3-L2 structure is disordered (Fig. 2B). The lack of interactions between the C-tail and the rest of the lipoyllysine-binding pocket causes significant rearrangement in helices α2 and α3. This is accompanied by a narrowing of the lipoyllysine-binding cavity and repositioning of the lipoate prosthetic group, which affects its interactions with a number of critical amino acid residues (Fig. 2B). It is likely that these rearrangements account for the differences in the strength of L2 binding displayed by PDHK2 and PDHK3 (13, 20, 31). Interestingly, the subunits in the L2-bound PDHK2 dimer appear to be nonequivalent. A difference is observed in the structure of their lipoyllysine-binding cavities. This difference comes about as a result of an additional winding of helix α2 that occurs at the expense of the loop connecting helices α2 and α3 (Fig. 2C). Similar, albeit less prominent, heterogeneity is also present in the structure of the PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p complex (not shown). The nature of this heterogeneity is currently unknown and requires further investigation. However, it should be pointed out that these observations are consistent with the earlier biochemical studies showing the heterogeneity of L2-binding sites in PDHK2 molecule (32). Thus, it is feasible that the structural nonequivalence of PDHK2 subunits in PDHK2-L2 and PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p complexes accounts for the functional heterogeneity documented in biochemical assays.

FIGURE 2.

Three-dimensional structure of lipoyllysine-binding cavity. A, close-up view showing the structure of lipoyllysine-binding cavity in PDHK2. The major structural elements contributing to the lipoyllysine-binding cavity, such as helices α2 and α3, the loop connecting these helices, and the C-tail of the neighboring subunit (colored orange) are shown as a ribbon representation. The lipoyl prosthetic group (CPK; C gray) is shown as a stick model. The final 2Fo - Fc electron density (blue) is superimposed on lipoyl group. A number of amino acid residues implicated in lipoate binding (13, 17) are shown as stick models colored in yellow. The hydrogen bond between Thr403 and Asn43 (CPK; C yellow) is in magenta. B, the structure of the lipoyllysine-binding cavity in PDHK3 is based on Protein Data Bank code 1y8n (13). The color scheme is the same as in A. C, superimposition of lipoyllysine-binding cavities from the chains A (colored yellow) and B (colored green) of the PDHK2-L2 structure. The lipoyl prosthetic group (CPK; C gray) is shown as a stick model. Asn43 (CPK; C yellow for chain A and C green for chain B) is shown as a stick model. The movement of the loop connecting helices α2 and α3 is indicated by a blue arrow.

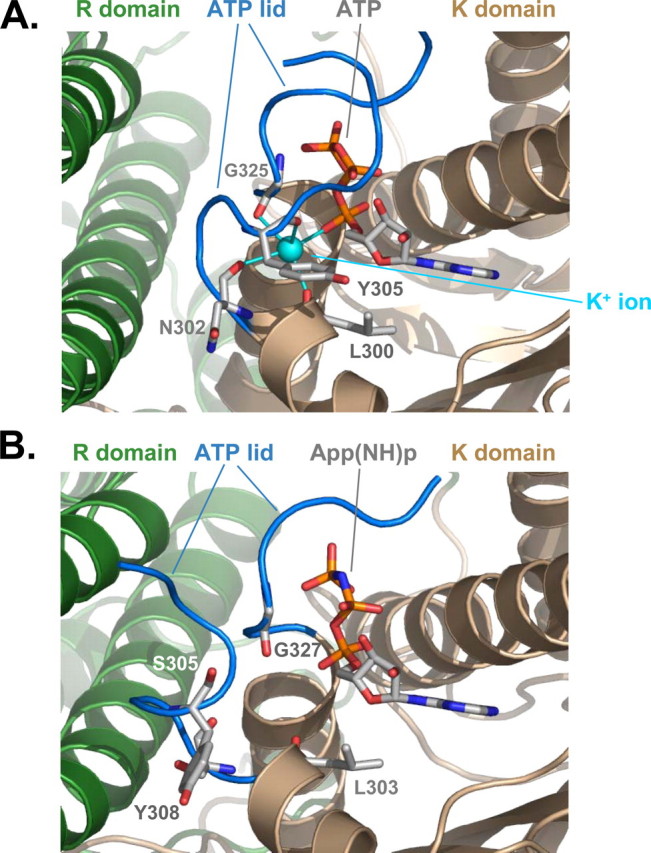

Conformation of the ATP Lid and Type I Potassium-binding Site—The ATP lid is a flexible loop that controls the access of ATP to the nucleotide-binding site of the kinase molecule (12, 13). In the structure of PDHK3-L2-ATP complex reported by Kato et al. (13), the ATP lid adopts a fully “closed” conformation (Fig. 3A). The distal portion of PDHK3 ATP lid makes a tight turn around the polyphosphate moiety of ATP, thereby assisting in positioning of theγ-phosphate in the active site. The proximal part of the lid encloses bound ATP. This closed conformation creates a type I potassium-binding site (Fig. 3A). Main chain oxygen atoms of Leu300, Asn302, Tyr305, and Gly325 serve as protein ligands for bound potassium ion. The fifth ligand of bound K+ comes from the Pα oxygen atom of ATP. This arrangement is thought to facilitate the catalysis of phosphotransfer reaction (13, 33).

FIGURE 3.

Three-dimensional structure of nucleotide-binding site. A, close-up view showing the structure of a nucleotide-binding site in PDHK3 based on the 1y8p coordinates (13). The structural elements of K (wheat) and R(green) domains are shown in a ribbon representation. The ATP lid (amino acids Leu303–Pro312 and Pro320–Gly325) is colored in blue. The bound potassium ion is cyan. B, close-up view showing the structure of the nucleotide-binding site in PDHK2. The color scheme is the same as in A. The ATP lid (amino acids Leu300–Arg310 and Leu323–Gly327) is colored blue. Several amino acid residues (CPK; C gray) that were implicated in binding of the potassium ion (13, 14) along with bound App(NH)p (CPK; C gray) are shown as stick models.

The ATP lid in PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p structure assumes a partially “open” conformation (Fig. 3B). The distal part of the ATP lid in PDHK2 is positioned similarly to that observed in PDHK3 (i.e. it winds around the polyphosphate moiety of App(NH)p, making extensive contacts with γ and β phosphates of bound nucleotide). However, the proximal part of the ATP lid in the PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p structure adopts an “open” conformation, which reflects a hinge movement of the entire segment corresponding to the residues Phe304–Pro312 away from the bound nucleotide (Fig. 3B). This open state is stabilized by multiple contacts between the amino acids of the ATP lid and R domain. The resulting conformation cannot bind potassium ions, because two of four protein ligands for K+ (i.e. Ser305 and Tyr308) are misplaced. A hinge movement of the proximal part of ATP lid toward the bound nucleotide is required in order to create a functional potassium-binding site. It is feasible that this movement is triggered through a cross-talk between K and R domains described by several laboratories (13, 32).

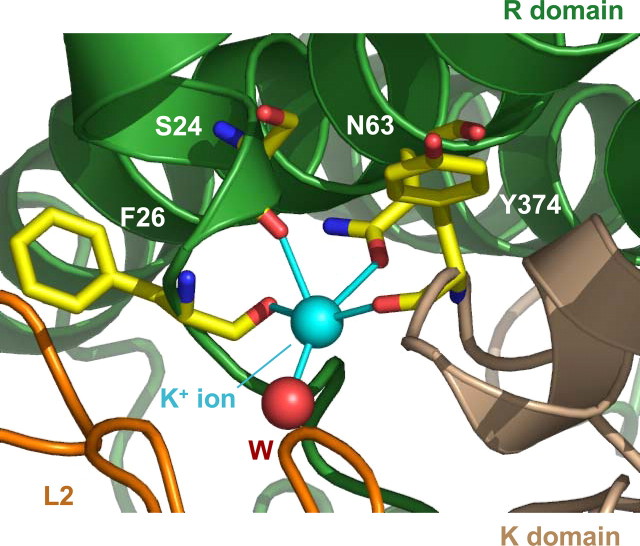

Novel Type II Potassium-binding Site—The electron density maps of PDHK2-L2 and PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p crystals revealed a novel PDHK2 potassium ion-binding site located on the interface with the L2 domain (Fig. 4). When refined as a potassium ion, the B-factors reach reasonable values and are in the same range as those obtained for the surrounding protein atoms. This potassium ion-binding site is shaped by the main chain and side chain oxygen atoms of the amino and carboxyl termini of the kinase molecule. The potassium ion is within 2.8 Å of the three main chain oxygen atoms of Ser24, Phe26, and Tyr374. The other oxygen atoms coordinating the bound potassium come from the hydroxyl group of Asn63 and a water molecule (Fig. 4). Such coordination by five oxygen atoms with an average distance of 2.8 Å is characteristic of certain type II potassium ion-binding sites (33). Additionally, the potassium ion in the PDHK2 molecule is in van der Waals contact with the main chain oxygen atom of Lys25. A comparison with the apo-PDHK2 structure (14) indicates that the binding of potassium ion does not induce any gross conformational changes in the loops shaping its binding site. However, from the B-factor plots, it is evident that the presence of the potassium ion does rigidify the interface between PDHK2 and L2 domain, suggesting that potassium ions might be significant in facilitating the binding of L2 to PDHK2.

FIGURE 4.

Three-dimensional structure of type II potassium-binding site in PDHK2. A ribbon representation shows structural elements of type II potassium binding contributed by R (green) and K (wheat) domains. The L2 domain is colored orange, whereas bound potassium ion is cyan. Amino acid residues (CPK; C in yellow) contributing to the coordination shell of bound potassium ion (Ser24, Phe26, Asn63, and Tyr374, respectively) are shown as stick models. The water molecule coordinating the potassium ion (W) is shown in ruby red.

The Role of Potassium Ions in Recognition of L2 and Adenyl Nucleotides by PDHK2—Although potassium ions are considered to be essential for kinase activity and regulation, their exact role remains controversial. On the one hand, several investigators demonstrated that potassium ions can stimulate kinase activity, presumably by promoting the phosphotransfer reaction (33–35). On the other hand, studies from the laboratory of Tom Roche (30, 36) showed that potassium ions inhibit kinase activity by facilitating the inhibitory effects of ADP and of ADP plus pyruvate. Here, in order to further investigate the mechanism of action of potassium ions, we characterized their effects on L2 and nucleotide binding by PDHK2.

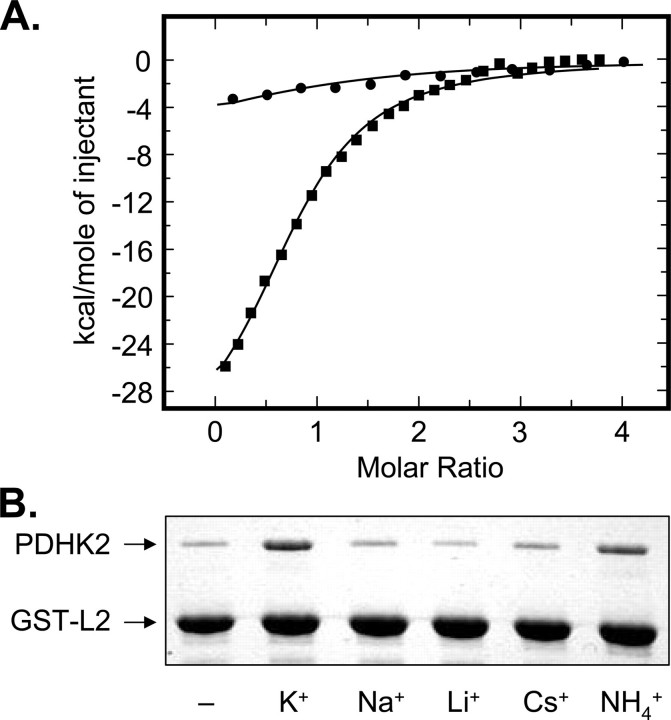

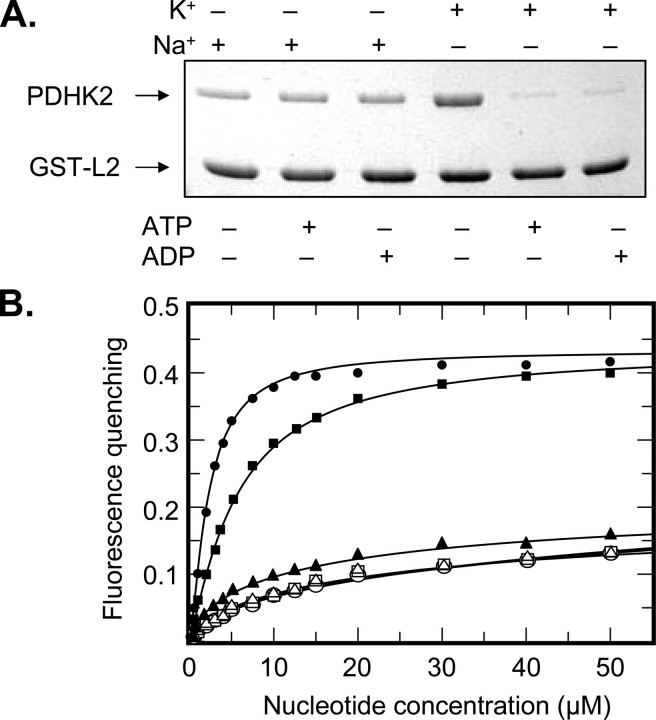

The role of potassium ions in L2 domain binding was studied using a combination of ITC and GST-L2 pulldown assay (Fig. 5). ITC revealed that in the presence of potassium ions, PDHK2 can readily bind the monomeric L2 with the dissociation constant of ∼8 μm (Table 2). Similar experiments conducted in the sodium-based buffer of otherwise identical composition yielded little if any differential heat (Fig. 5A and Table 2). The latter is consistent with the interpretation that binding affinity of PDHK2 for the L2 domain is significantly decreased in the absence of potassium ions. In agreement with this conclusion, GST-L2 pulldown experiments showed that potassium ions greatly increase the amount of PDHK2 recovered in the L2-bound form (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, this effect appeared to be largely specific for the potassium ions. Other monovalent ions, such as sodium, lithium, or cesium had no appreciable effect on L2 binding, whereas NH+4 ions partially substituted for potassium ions (Fig. 5B). Taken together, these data strongly suggest that potassium ions are critical in determining the strength of L2 binding by PDHK2. From our structural studies, it seems reasonable to propose that this effect is mediated through the type II potassium-binding site located in the vicinity of the PDHK2 interface with L2 domain.

FIGURE 5.

Binding of L2 domain to the wild-type PDHK2. A, binding isotherms of L2 and PDHK2 obtained in sodium-based (closed circles) and potassium-based buffer systems (closed squares). ITC measurements were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The molar ratio represents L2 monomer to PDHK2 dimer. The solid lines depict the least-square fitting curves obtained using a single-site L2 binding model. Fittings were made using Origin version 7.0 software. B, effect of monovalent cations on L2 binding by PDHK2. SDS-PAGE analysis of GST-L2 pulldown experiments was carried out as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Gels were stained with Coomassie R250.

TABLE 2.

Thermodynamic properties for the binding of ATP, ADP, and L2 to the wild-type PDHK2 protein Results are expressed as means ± S.D. of three experiments conducted with different preparations of proteins. ITC measurements were performed at 30 °C in a VP-ITC microcalorimeter (MicroCal). Dissociation constants and enthalpy changes were obtained using the Origin 7.0 software package supplied by the manufacturer. NM, not measurable due to insufficient amount of differential heat produced in the binding reaction.

|

Ligand |

Potassium phosphate buffer |

Sodium phosphate buffer |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | KD | ΔH | n | KD | ΔH | |

| μm | kcal/mol | μm | kcal/mol | |||

| ATP | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.2 ± 0.3 | –19.2 ± 0.7 | 2.0 ± 0.2 | 19 ± 1 | –10.3 ± 0.9 |

| ADP | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 11.4 ± 0.7 | –10.3 ± 0.4 | NM | ||

| L2 | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 8.3 ± 0.3 | –36.4 ± 1.2 | NM | ||

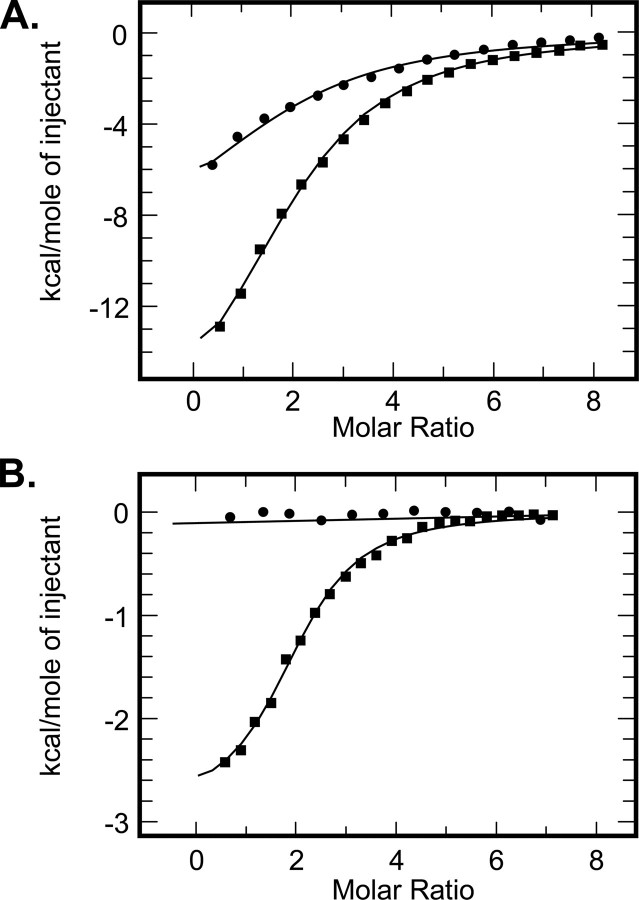

The role of potassium ions in nucleotide binding was characterized by ITC. As illustrated in Fig. 6A, potassium ions had a significant effect on binding of ATP. In potassium-based buffer, PDHK2 bound ATP more than 15 times stronger than in identical sodium-based buffer (Table 2). The facilitating effect of potassium ions appeared to be even greater when ADP was used as a ligand. As shown in Fig. 6B, the titration of PDHK2 with ADP in the sodium-based buffer did not generate sufficient molecular heat, which is indicative of a very weak binding. Estimates based on the assay sensitivity suggest that potassium ions increase the affinity of PDHK2 for ADP by at least 50-fold.

FIGURE 6.

Binding of adenyl nucleotides to wild-type PDHK2. Binding isotherms of ATP (A) or ADP (B) and PDHK2 were obtained in sodium-based (closed circles) and potassium-based buffer systems (closed squares). ITC measurements were performed as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The molar ratio represents nucleotide/PDHK2 dimer. The solid lines depict the least-square fitting curves obtained using a single-site L2 binding model. Fittings were made using Origin version 7.0 software.

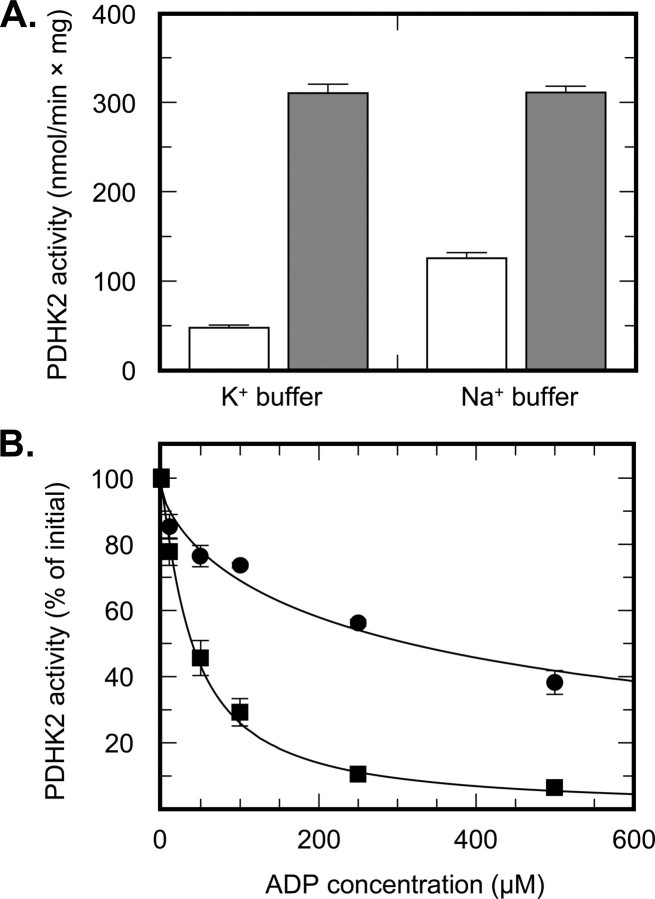

The Role of Potassium Ions in PDHK2 Activity and Regulation—To further investigate the role of potassium ions in PDHK2 catalysis and regulation, we conducted a number of functional assays in potassium- versus sodium-based buffers. Somewhat unexpectedly, we found that the activity of free PDHK2 toward free E1 component is 3-fold greater when measured in the sodium rather than potassium buffer, indicating that potassium ions inhibit the activity of free PDHK2 (Fig. 7A). In contrast, the activity of E2-bound PDHK2 toward the E2-bound E1 showed little if any effect of potassium ions, suggesting that binding to E2 partially alleviates the inhibitory effect of potassium ions on PDHK2 activity. It is generally believed that dissociation of ADP is the rate-limiting step in the catalytic cycle of PDHK2 (30). Considering that ADP binding is greatly enhanced in the presence of potassium ions, it is feasible that the inhibitory effect of potassium ions on PDHK2 activity comes about as a result of an enhanced binding of the product (i.e. ADP). In agreement with this hypothesis, we found that potassium ions cause an almost 10-fold increase in the apparent inhibition constant for ADP (Fig. 7B and Table 3). The complex-bound PDHK2 appeared to be less prone to the potassium-dependent product inhibition due to a marked decrease in PDHK2 affinity for ADP caused by L2 or E2 binding to PDHK2 (32, 37). Taken together, our data strongly suggest that potassium ions are not required for the catalysis of the phosphotransfer reaction, as it was proposed earlier by Kato et al. (13), but rather are necessary for the regulation of kinase activity.

FIGURE 7.

Regulation of PDHK2 activity by potassium ions. A, PDHK2 activity determined in potassium- or sodium-based buffer systems. Activities determined toward the free E1 component are shown by white bars. Activities determined in the presence of the E2-E3BP subcomplex are shown by gray bars. B, inhibition of PDHK2 activity by ADP determined in a sodium-based (closed circles) or potassium-based buffer system (closed squares). Data are expressed as the percentage of activity determined in the absence of ADP. The solid lines depict the least-square fitting curves obtained using a four-parameter logistic IC50 model. Fittings were made using GraFit version 3.09b software (Erithacus Software Ltd., East Grinstead, West Sussex, UK).

TABLE 3.

Kinetic parameters for the effect of ADP on PDHK2 activity Results are expressed as means ± S.D. of three experiments conducted with different preparations of proteins. Kinetic parameters were obtained using the GraFit 3.09b software package (Erithacus Software Ltd., East Grinstead, West Sussex, UK).

| Variable | Potassium phosphate buffer | Sodium phosphate buffer |

|---|---|---|

| Y range (%) | 98 ± 5 | 97 ± 5 |

| IC50 (μm) | 40 ± 7 | 342 ± 76 |

| Slope factor | 1.1 ± 0.2 | 0.8 ± 0.2 |

To further explore this hypothesis, we investigated the effects of potassium and sodium ions on the cross-talk between the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites of PDHK2, which is believed to be important for the movement of the PDHK2 molecule along the surface of the E2 core (32, 37). In agreement with our earlier studies showing a cross-talk in binding of adenyl nucleotides and L2 (32), we found that in the presence of potassium ions both ATP and ADP greatly decreased the binding of PDHK2 to the L2 domain (Fig. 8A). In contrast, there was no cross-talk between the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites in the sodium-based buffer system, suggesting that potassium ions play a critical role in coupling the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites (Fig. 8A). To examine this coupling mechanism further, we investigated quenching of PDHK2 intrinsic fluorescence by adenyl nucleotides. Hiromasa et al. (7) showed that nucleotide binding brings about an intrinsic fluorescence quenching of Trp391. Based on the structural evidence presented by Knoechel et al. (14), this residue is deeply buried inside the R domain of the cognate subunit of PDHK2 dimer. Binding of ADP and DCA or just ADP binding to PDHK2 is thought to induce the release of Trp391 from its binding pocket, accompanied by fluorescence quenching, release of C-tails, and partial disassembling of the L2-binding site (7, 12, 14). This makes PDHK2 fluorescence quenching a useful tool for monitoring the coupling between the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites. As shown in Fig. 8B, both ATP and ADP caused a dose-dependent quenching of PDHK2 fluorescence in potassium-based buffer. Similar experiments carried out in the sodium-based buffer did not show an appreciable quenching in excess of what was due to the inner filter effect measured in the presence of AMP. Importantly, the fluorescence spectra of PDHK2 recorded in sodium- and potassium-based buffer systems were virtually identical, indicating that neither sodium nor potassium ions affect the environment of Trp391 directly (data not shown). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that potassium ions are indispensable for the nucleotide-induced conformational changes leading to the displacement of Trp391 observed in structural studies (12, 14).

FIGURE 8.

Interdomain communication in PDHK2 molecule. A, cross-talk between L2- and nucleotide-binding sites of PDHK2 characterized using a GST-L2 pulldown assay. Pulldown experiments were carried out in potassium- or sodium-based buffer systems as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Adenyl nucleotides were used at a final concentration of 0.5 mm. Gels were stained with Coomassie R250. B, quenching of the intrinsic PDHK2 fluorescence by adenyl nucleotides. Incremental increases in PDHK2 fluorescence quenching with increasing concentration of ATP, ADP, or AMP are shown by circles, squares, or triangles, respectively. Experiments were carried out in potassium-based (closed symbols) or sodium-based buffer systems (open symbols). Fluorescence measurements were made as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Data were transformed and analyzed using approaches described by Hiromasa et al. (7).

Thus, it appears that potassium ions have a 3-fold effect on PDHK2: 1) structural stabilization of the L2-binding site; 2) enhancement of product inhibition; and 3) facilitation of the cross-talk between nucleotide- and L2-binding sites. Some of these effects, such as L2 binding and ADP inhibition, can be clearly attributed to the effects of potassium ions acting through type II or type I potassium-binding site, respectively, whereas the other (i.e. potassium-dependent interdomain communication) probably requires the engagement of both sites.

Conclusions—PDHK2 is a ubiquitous protein kinase that was implicated in diseases such as diabetes (10) and cancer (11). It operates as an integral part of a large multienzyme complex (1). Several lines of evidence strongly suggest that the association with PDC is crucial for PDHK2 activity and regulation (1, 2). In this study, we determined the crystal structure of PDHK2 complexed with L2 domains that serve as docking sites for the PDHK2 molecule on the transacetylase scaffold. It is generally believed that association with L2 domains stimulates kinase activity and provides means for kinase regulation (1, 9). Recently, Kato et al. (13) proposed that allosteric control exerted by L2 domains comes about as a result of L2-induced hinge movement between the K and R domains of the kinase molecule. According to the authors, this movement opens up the E1-binding cavity and thereby promotes the catalysis (13). The results of our study are clearly in contradiction with these conclusions. Comparison of PDHK2-L2/PDHK2-L2-App(NH)p and apo-PDHK2 structures (Protein Data Bank accession code 2btz) shows little if any interdomain movement. Instead, it reveals quite dramatic ordering of the loop connecting helices α7 and α8 (E-loop) that occurs upon binding of L2 and App(NH)p. This loop is located in the vicinity of the L2-binding site and forms the back wall of the E1-binding cavity. Thus, it seems reasonable to propose that binding of L2 and App(NH)p causes an ordering of the E1-binding site and thereby facilitates binding of the protein substrate through the induced fit mechanism. This would explain observations made by Bao et al. (30), who demonstrated that binding to E2 increased the Km value of PDHK2 for E1 by more than 400-fold.

Four mammalian PDHK isozymes have been identified to date (3, 4). Despite significant differences in their activities and regulation, their three-dimensional structures appear to be highly similar (12–15), suggesting that minor differences in their amino acid sequences can account for the gross differences in their activities and regulation. In agreement with this idea, Knoechel et al. (14) have shown that sensitivity of PDHK to dichloroacetate (DCA) is largely determined by a single amino acid residue. Position 161 in PDHK3 is occupied by phenylalanine. In other kinases, the corresponding position has isoleucine (PDHK1 and PDHK2) or threonine (PDHK4) residues. The bulky side chain of Phe161 tends to fill the space usually occupied by DCA, preventing DCA from binding to PDHK3. Consequently, PDHK3 is the only isozyme that is not regulated by either DCA or pyruvate (1, 5). Likewise, significant reshaping of the PDHK2 lipoyllysine-binding cavity caused by the interaction between the unique far carboxyl terminus of PDHK2 and helix α2-loop-helix α3 structure established in this study may account for the 10-fold difference in the affinity of PDHK2 and PDHK3 for the L2 domain (13, 32).

Pioneering studies conducted by Machius et al. (38) identified a tightly bound potassium ion situated in the active site of branched chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase. Structurally, the type I potassium-binding site of branched chain α-ketoacid dehydrogenase kinase appears to be similar to that of pyruvate kinase, chaperonin GroEL, chaperone Hsc70, fructose 1,6-bisphosphatase, and a few other K+-activated enzymes involved in phosphoryl transfer reactions (33). Since then, a similar site has been found in the structure of PDHK3 (13). The majority of type I enzymes have an absolute dependence on potassium ions, which are required for optimal catalytic activity. Therefore, it was assumed that potassium ions play a similar role in PDHK catalysis (13). However, the results of this and other studies (34–36) suggest a different role for potassium ions, because kinase can briskly phosphorylate its protein substrate in the absence of potassium ions. Here, we present evidence indicating that potassium ions facilitate the nucleotide binding to PDHK2. This is primarily important for the regulation of kinase activity, in particular for the product inhibition by ADP and for the cross-talk between the nucleotide- and L2-binding sites. In addition, our results reveal that PDHK2 has another type of potassium-binding site situated on the interface with the L2 domain. This type II potassium-binding site plays a structural role, rigidifying the interface between PDHK2 and L2. This, in turn, dramatically improves the L2 binding, thereby facilitating targeting of PDHK2 toward its protein substrate and providing yet another route to control PDHK2 activity. While this manuscript was under review, Hiromasa et al. (39, 40) published two back-to-back papers showing that potassium ions greatly facilitate the nucleotide binding and aid in L2 binding by human PDHK2, which is in good agreement with our data. The authors suggested the existence of two distinct potassium-binding sites in the PDHK2 molecule (40). The results presented in this paper provide the structural framework for the biological effects of potassium ions and further underscore their important role in PDHK2 activity and regulation.

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff of the South East Regional Collaborative Access Team (SER-CAT) at the Advanced Photon Source, Argonne National Laboratory, for assistance in data collection. Use of the Advanced Photon Source was supported by the United States Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences, under Contract W-31-109-Eng-38.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3crk and 3crl) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant GM051262 (to K. M. P.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; PDHK, pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; PDHK1, PDHK2, PDHK3, and PDHK4, isozymes 1, 2, 3, and 4 of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase; E1, pyruvate dehydrogenase component of PDC; E2, dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase component of PDC; E3, dihydrolipoamide dehydrogenase component of PDC; E3/BP, E3-binding protein; DCA, dichloroacetate; App(NH)p, adenylyl imidodiphosphate; GST, glutathione S-transferase; DTT, dithiothreitol; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; ITC, isothermal titration calorimetry.

References

- 1.Roche, T. E., and Hiromasa, Y. (2007) Cell Mol. Life Sci. 64 830-849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patel, M. S., and Korotchkina, L. G. (2001) Exp. Mol. Med. 33 191-197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gudi, R., Bowker-Kinley, M. M., Kedishvili, N. Y., Zhao, Y., and Popov, K. M. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 28989-28994 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rowles, J., Scherer, S. W., Xi, T., Majer, M., Nickle, D. C., Rommens, J. M., Popov, K. M., Harris, R. A., Riebow, N. L., Xia, J., Tsui, L. C., Bogardus, C., and Prochazka, M. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271 22376-22382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bowker-Kinley, M. M., Davis, W. I., Wu, P., Harris, R. A., and Popov, K. M. (1998) Biochem. J. 329 191-196 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Randle, P. J. (1995) Proc. Nutr. Soc. 54 317-327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hiromasa, Y., Hu, L., and Roche, T. E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 12568-12579 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cate, R. L., and Roche, T. E. (1978) J. Biol. Chem. 253 496-503 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yang, D., Gong, X., Yakhnin, A., and Roche, T. E. (1998) J. Biol. Chem. 273 14130-14137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sugden, M. C., and Holness, M. J. (2002) Curr. Drug Targets Immune Endocr. Metabol. Disord. 2 151-165 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cairns, R. A., Papandreou, I., Sutphin, P. D., and Denko, N. C. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 104 9445-9450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Steussy, C. N., Popov, K. M., Bowker-Kinley, M. M., Sloan, R. B., Jr., Harris, R. A., and Hamilton, J. A. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 37443-37450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato, M., Chuang, J. L., Tso, S.-C., Wynn, R. M., and Chuang, D. T. (2005) EMBO J. 24 1763-1774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knoechel, T. R., Tucker, A. D., Robinson, C. M., Phillips, C., Taylor, W., Bungay, P. J., Kasten, S. A., Roche, T. E., and Brown, D. G. (2006) Biochemistry 45 402-415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kato, M., Li, J., Chuang, J. L., and Chuang, D. T. (2007) Structure 15 992-1004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tuganova, A., Yoder, M. D., and Popov, K. M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 17994-17999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuganova, A., Klyuyeva, A., and Popov, K. M. (2007) Biochemistry 46 8592-8602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kolobova, E., Tuganova, A., Boulatnikov, I., and Popov, K. M. (2001) Biochem. J. 358 69-77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Harris, R. A., Bowker-Kinley, M. M., Wu, P., Jeng, J., and Popov, K. M. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 19746-19751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tuganova, A., Boulatnikov, I., and Popov, K. M. (2002) Biochem. J. 366 129-136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klyuyeva, A., Tuganova, A., and Popov, K. M. (2005) Biochemistry 44 13573-13582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Otwinowski, Z., and Minor, W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 276 307-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jogl, G., Tao, X., Xu, Y., and Tong, L. (2001) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 57 1127-1134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murshudov, G. N., Lebedev, A., Vagin, A. A., Wilson, K. S., and Dodson, E. J. (1999) Acta Crystallogr. Sect. D 55 247-255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams, P. D., Gopal, K., Grosse-Kunstleve, R. W., Hung, L. W., Ioerger, T. R., McCoy, A. J., Moriarty, N. W., Pai, R. K., Read, R. J., Romo, T. D., Sacchettini, J. C., Sauter, N. K., Storoni, L. C., and Terwilliger, T. C. (2004) J. Synchrotron Radiat. 11 53-55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Emsley, P., and Cowtan, K. (2004) Acta Cryst. Sect. D 60 2126-2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laemmli, U. K. (1970) Nature 227 680-685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lowry, O. H., Rosebrough, N. J., Farr, A. L., and Randall, R. J. (1951) J. Biol. Chem. 193 265-275 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Quinn, J., Diamond, A. G., Masters, A. K., Brookfield, D. E., Wallis, N. G., and Yeaman, S. J. (1993) Biochem. J. 289 81-85 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bao, H., Kasten, S. A., Yan, X., and Roche, T. E. (2004) Biochemistry 43 13432-13441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baker, J. C., Yan, X., Peng, T., Kasten, S., and Roche, T. E. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275 15773-15781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tuganova, A., and Popov, K. M. (2005) Biochem. J. 387 147-153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page, M. J., and DiCera, E. (2006) Physiol. Rev. 86 1049-1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Robertson, J. G., Barron, L. L., and Olson, M. S. (1989) J. Biol. Chem. 264 11626-11631 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pawelczyk, T., and Olson, M. S. (1992) Biochem. J. 288 369-373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roche, T. E., and Reed, L. J. (1974) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 59 1341-1348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hiromasa, Y., and Roche, T. E. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 653-662 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Machius, M., Chuang, J. L., Wynn, R. M., Tomchick, D. R., and Chuang, D. T. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 11218-11223 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hiromasa, Y., and Roche, T. E. (2008) Biochemistry 47 2298-2311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hiromasa, Y., Yan, X., and Roche, T. E. (2008) Biochemistry 47 2312-2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]