Abstract

In conjunction with the Permian–Triassic ecologic crisis ≈250 million years ago, massive dieback of coniferous vegetation resulted in a degradation of terrestrial ecosystems in Europe. A 4- to 5-million-year period of lycopsid dominance followed, and renewed proliferation of conifers did not occur before the transition between Early and Middle Triassic. We document this delayed re-establishment of equatorial forests on the basis of palynological data. The reconstructed pattern of vegetational change suggests that habitat restoration, migration, and evolutionary processes acted synergistically, setting the stage for successional replacement of lycopsid dominants by conifers within a period of ≈0.5 million years.

Understanding of patterns and processes of past ecologic crises is no longer a matter of purely academic interest. Studies of biotic and biogeochemical change related to mass extinction events may substantially contribute to a prediction of the long-term consequences of current man-induced environmental deterioration and its associated biodiversity decline (1, 2). In making such a contribution, we should focus on the potential of high-resolution analysis of distinctive survival and recovery phases after episodes of global ecosystem collapse (3). At present, conceptual models of survival and recovery are notably constrained by a variety of marine paleoecologic records (3–6). However, because of its role in global biomass storage and its sensitivity to environmental change, land vegetation is one of the most obvious biota to be investigated for patterns of survival and recovery. Notably, the aftermath of the unrivaled Permian–Triassic (P–Tr) crisis (7, 8) should serve as a valuable field of botanical inquiry.

At the very end of the Permian, dieback of woody vegetation dramatically affected terrestrial ecosystems (9–12). In the northern and southern humid climatic zones of Pangaea, it resulted in the widespread disappearance of peat forests (13, 14). In the semi-arid equatorial region, the dominant conifer taxa of the Late Permian Euramerican floral realm became extinct at, or close to, the P–Tr junction (15). Among the surviving plants, lycopsids played a central role in repopulating the initial ecological desert. Subsequent radiation and expansion among Isoetales (16) resulted in dense populations of the succulent quillwort Pleuromeia sternbergii (17).

Throughout Europe, plant megafossil information indicates that ecosystem recovery to precrisis levels of structure and function did not occur before the transition between the Early and Middle Triassic. A replacement of the Pleuromeia vegetation by coniferous forests is evidenced by the Voltzia-dominant communities that characterize the early part of the Middle Triassic (17–19). In contrast to the discontinuous and qualitative plant megafossil record, successive pollen and spore assemblages can provide the sample size and stratigraphic spacing needed to resolve the temporal pathway of plant succession during this recovery phase. Here, we document and discuss the delayed return of woody plants in Europe on the basis of quantitative palynological data from an Early–Middle Triassic transition sequence in Hungary.

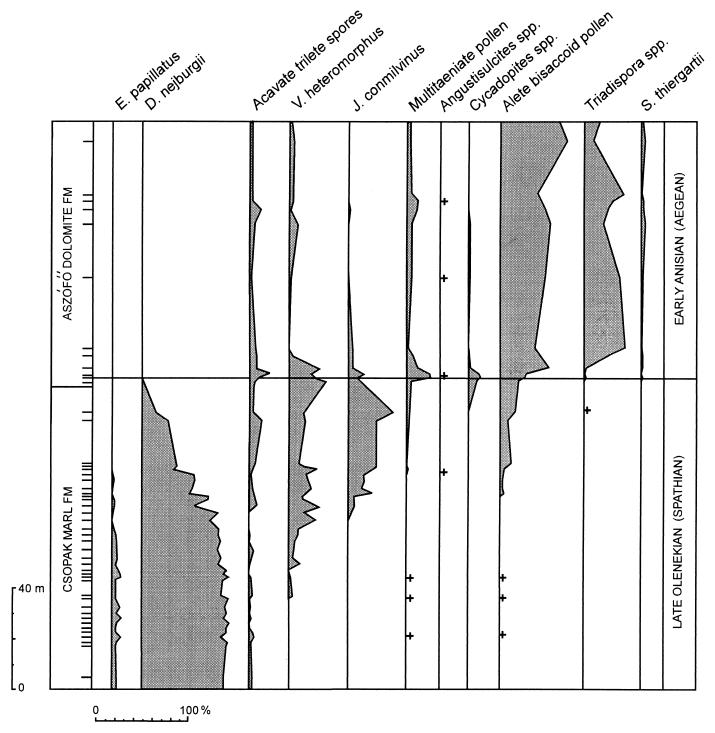

In current chronostratigraphic classification, the Early–Middle Triassic junction corresponds to the boundary between the Olenekian and Anisian Stages. In Europe, a continuous shallow marine Olenekian–Anisian transition sequence is particularly well developed in the Transdanubian Central Range in Hungary (20, 21). The boundary approximates the transition between the marls and limestones of the Csopak Marl Formation and the lagoonal dolomites and marls of the Asófő Dolomite Formation. In outcrops, the Csopak Marl Formation yields the Tirolites ammonoid fauna, indicative of the Spathian Substage of the Olenekian. Continuously cored exploration wells have enabled detailed biostratigraphic analysis of marine and land-derived palynomorphs (20–23). Quantitative distribution patterns of spore and pollen types (Fig. 1) are obtained from samples of borehole Bakonyszűcs-3. Information on the botanical affinity of the types is summarized in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Quantitative distribution patterns of selected spore and pollen types from the Early to Middle Triassic (Olenekian–Anisian) transition sequence in the Transdanubian Central Range, Hungary (borehole Bakonyszűcs-3, 6 km east of the town of Pápa; for location, see ref. 21). The diagram reflects the successional replacement of lycopsid-dominant by conifer-dominant vegetation. Horizontal lines represent samples. Relative abundances are expressed as percentages of total spore and pollen assemblage, and plus signs indicate rare, isolated occurrences.

Table 1.

Botanical affinity of principal Late Permian and Early/Middle Triassic spore/pollen categories from Europe

| Palynological category | Botanical affinity | Remarks |

|---|---|---|

| Scythiana spp. | Bryophytes (probably Pottiaceae) | Originally regarded as marine phytoplankton (acritarchs) (20, 21). Because of striking similarity to moss spores from the Cretaceous-Tertiary transition that resemble spores of extant Pottiaceae (50), the forms are likely to represent bryophytes. |

| Endosporites papillatus | Lycopsids (Selaginallales) | Cavate trilete microspores with papillate inner bodies and a fragile outer wall have been found in association with the Early Triassic strobilus Selaginellites polaris (51). |

| Cavate tetrads | Lycopsids (Selaginellales, Isoetales) | Permian and Triassic cavate microspores represent both Selaginellales and Isoetales (52). A variety of forms may sometimes retain a tetrad condition. In literature, tetrads also known as species of the form-genus Lapposisporites. |

| Densoisporites nejburgii | Lycopsids (Isoetales; Pleuromeiaceae; Pleuromeia, Lycomeia) | Known from Lycomeia rossica, and found in association with species of Pleuromeia (16, 53). |

| Acavate trilete spores | Ferns (Anomopteris and unknown genera) Horsetails (Schizoneura, Equisetites) | Most abundant are smooth forms that correspond to Punctatisporites, known from Anomopteris mougeotii. Rare smooth forms correspond to Calamospora, known from equisetalean fructifications (Equisetostachys) assigned to Schizoneura and Equisetites (18). Ornamented forms are mainly represented by Verrucosisporites and Convolutispora, form-genera characteristic of a variety of Late Paleozoic ferns (52). |

| Nuskoisporites dulhuntyi | Conifers (Walchiaceae; Ortiseia) | Prepollen of the Late Permian conifer species Ortiseia leonardii, O. visscheri, and O. jonkeri (15, 34). |

| Lueckisporites virkkiae | Conifers (Majonicaceae; Majonica) | Known from the Late Permian conifer Majonica alpina (35). |

| Jugasporites delasaucei | Conifers (Ullmanniaceae; Ullmannia) | Known from the Late Permian conifer Ullmannia frumentaria (54). |

| Voltziaceaesporites heteromorphus | Conifers (family unknown; Yuccites) | Known from coniferous cones (Willsiostrobus), assignable to Yuccites vogesiacus (18); forms have also been described as Alisporites landianus (41). |

| Jugasporites conmilvinus | Conifers (probably Ullmanniaceae; genus unknown) | Forms are morphologically similar, but not identical to Jugasporites delasaucei (55); in literature, they are also known as Neojugasporites. |

| Multitaeniate pollen | Pteridosperms (Peltaspermales; family and genus unknown) | Identified form-genera include Lunatisporites, Protohaploxypinus and Striatoabieites. Apart from the Gondwanaland glossopterids, these forms are generally associated with Late Permian peltasperms (56, 57). |

| Cycadopites spp. | Cycads (family and genus unknown) | Monosulcate pollen is known from a variety of Paleozoic and Mesozoic gymnosperms (52). Considering the megafossil record, Late Permian and Early/Middle Triassic forms from Europe are likely to represent cycads. |

| Angustisulcites spp. | Conifers (Aethophyllaceae; Aethophyllum) | Known from the herbaceous conifer Aethophyllum stipulare (18, 58); in literature, forms are also described as species of the form-genus Illinites. |

| Alete bisaccoid pollen | Conifers Pteridosperms (families and genera unknown) | In general, alete bisaccoid pollen is known from conifers and pteridosperms. Apart from serving as a dump for unidentifyable bisaccoid pollen, the category includes forms of Alisporites known from Willsiostrobus coniferous cones (18). It is likely that a considerable amount of the unidentified material is only seemingly alete, comprising badly preserved specimens of Jugasporites and Triadispora. |

| Triadispora spp. | Conifers (Voltziaceae; Voltzia) | Known from coniferous cones (Darneya, Sertostrobus) assigned to Voltzia (18). |

| Stellapollenites thiergartii | Conifers (family and genus unknown) | Known from the coniferous cone Willsiostrobus hexasacciphorus (59). In Europe, first and last occurrences of this distinctive pollen delimit the Anisian Stage (60). |

Immediately apparent is the overwhelming abundance of Densoisporites nejburgii in the lower part of the Csopak Marl Formation, indicative of the Pleuromeia monocultures known from Olenekian megafossil records in Europe. Selaginellales and other pteridophytes are subordinate elements. In the upper part of the Csopak Marl Formation, gradual shifts in relative abundances give a straightforward picture of the sequence of the gymnosperm invasions. Initial invasion was by the conifer Yuccites, as reflected by the coming and proliferation of Voltziaceaesporites heteromorphus. Additional elements followed, including the possibly ullmanniaceous conifer that produced Jugasporites conmilvinus. The lycopsid component declines drastically and disappears from the record in the basal part of the Asófő Dolomite Formation. The decrease in Voltziaceaesporites and Jugasporites, and a simultaneous increase in Triadispora and other coniferous pollen, mark the onset of the Voltzia-dominant climax vegetation of the Anisian.

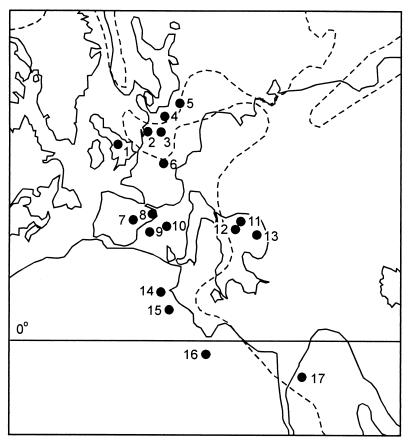

The general trend observed in compositional change between Densoisporites-dominant and Triadispora-dominant assemblages is consistent with coeval (semi) quantitative palynological records from outcrops and boreholes in many parts of Europe, northern Africa, and Israel (Fig. 2). The pollen and spore assemblages originate from both terrestrial (lacustrine, fluviatile) and shallow marine sequences. They are invariably dominated by allochthonous elements, thus reflecting changes in regional vegetation. Because of long-distance (wind, river) dispersal, the assemblages include a regionally derived mixture of pollen and spore types originating from both lowland and upland communities (24). The most complete comparative records are from boreholes in Poland (25, 26).

Figure 2.

Geographic distribution of Early to Middle Triassic palynological records from Europe and adjacent parts of Africa and Asia, reflecting part of a successional change from a Pleuromeia vegetation to a Voltzia-dominant climax vegetation. 1, Britain (61, 62); 2, The Netherlands (63); 3, western Germany (64–67); 4, eastern Germany (68–71); 5, northern and central Poland (25, 26); 6, northeastern France (72); 7, central–eastern Spain (73, 74); 8, northeastern Spain (75, 76); 9, Baleares (77); 10, Sardinia (78); 11, Hungary, Transdanubian Central Range (present paper; refs. 20–23); 12, Hungary, Mecsek Mountains (79); 13, Rumania (80); 14, Tunisia (81); 15, northwestern Libya (82); 16, northeastern Libya (83); 17, Israel, Negev (84, 85). Dashed line indicates approximate position of Early Triassic shorelines.

Despite the difference in temporal scale, the unidirectional Early to Middle Triassic vegetation change in Europe mimics patterns of plant succession that occurred in response to the climate amelioration at the beginning of the Holocene approximately 11,000 years ago. In both cases, palynological data indicate that the re-establishment of climax forests proceeds through phases, in which herbs and shrubs are important functional members of the community. However, although rapid Holocene plant succession is notably regulated by habitat restoration and migration (27), it is conceivable that the long-term pattern of Early to Middle Triassic succession is also influenced by evolutionary processes. Significant influences of climate change are unlikely. Throughout the Late Permian, Early Triassic and Middle Triassic, terrestrial sedimentation in Europe is consistently dominated by the “Buntsandstein” redbed facies, indicative of warm, semi-arid conditions.

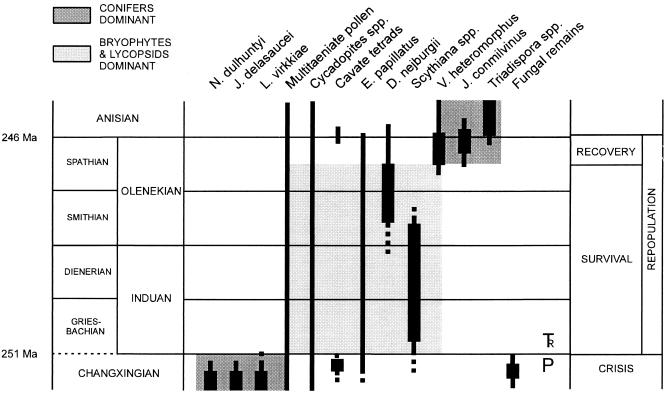

Under the prevailing semi-arid conditions, massive dieback of woody vegetation in Europe is likely to have resulted in extensive soil erosion. Early Triassic palynological data (Fig. 3) confirm the pioneering role for surviving lycopsids. Evidenced by the often frequent occurrence of Scythiana, bryophytes also appear to have been successful elements in the colonization of depopulated terrain (28). By analogy with many of their recent representatives, both lycopsids and bryophytes could have been preadapted to oligotrophic conditions. Earliest lycopsid pioneers may have included both Selaginellales and Isoetales. Because of their successful radiation and expansion after P–Tr extinctions, the Isoetales may be classified as crisis progenitors (3–6), specifically adapted to stressed environments of the Early Triassic survival phase. At least in Europe and other semi-arid regions, such as northern China (29), the resulting widespread vegetation, characterized by the relatively large succulent Pleuromeia sternbergii, remained stable for a longer period of time. This prolonged ecologic success of heterosporous lycopsids is remarkable and needs further investigation. Because of the unisexual gametophytes, free-sporing heterospory cannot be regarded as an effective long-distance dispersal strategy in the water-limited environments of Europe (30, 31).

Figure 3.

Generalized stratigraphic distribution of selected latest Permian and Early/Middle Triassic spore and pollen types in Europe. For information on the botanical affinity of the spores and pollen, see Table 1. The ecologic crisis and associated conifer extinction is marked by a proliferation of fungal remains (9, 11, 86). It should be noted that first appearance of the conodont Hindeodus parvus is presently recommended to mark the onset of the Triassic (87). One of the implications of this definition is that the crisis occurred before the P–Tr boundary, rather than at the boundary. Preceding the successional recovery of conifer-dominant vegetation, postcrisis repopulation is characterized by a prolonged bryophyte/lycopsid-dominant survival phase (terminology after refs. 3–6). For absolute age estimates, see text.

In addition to lycopsid pioneers, the parent taxa of some of the accessory Early Triassic spore and pollen types could be survivors of the P–Tr crisis. Notably, multitaeniate pollen and Cycadopites may sometimes show more or less continuous Late Permian to Middle Triassic occurrences, but relative abundances vary considerably. These pollen types may represent lineages of small, stress-tolerant pteridosperms and cycads that survived as severely fragmented populations in locally favorable sites. There are no conclusive palynological data supporting a concomitant survival of conifers in Europe.

Temporal analysis of Early Triassic paleosol development (17) suggests a reduced rate of soil formation up to Late Olenekian times. By developing soil resources, the Pleuromeia-dominant vegetation probably contributed to the restoration of habitats necessary for the documented successional replacement by conifer-dominant vegetation (Fig. 1). There is no evidence, from either fossil wood or root horizons, that early successional conifers, such as Yuccites, could classify as trees. They probably formed densely populated shrubland. Part of the accessory gymnosperms may even represent herbaceous plants, as exemplified by Aetophyllum. This conifer genus, very rarely reflected in the Hungarian pollen record but common elsewhere in Europe, lacks secondary xylem tissue and had a ruderal life strategy (18, 19, 32). In contrast, the size of recovered fossil wood supports the idea that the late successional species of Voltzia include genuine trees (33). Root structures (17) indicate that the Voltzia-dominant climax vegetation had the character of a relatively open forest.

The successional dominants represent conifers that are unknown from the extensive Late Permian megafloral and palynological records. They are immigrants that invaded European habitats after their Early Triassic origination elsewhere. Dominant Late Permian conifers in Europe comprise mainly the families Walchiaceae, Ullmanniaceae, and Majonicaceae (34–36). The long-ranging Carboniferous–Permian Walchiaceae became extinct close to the P–Tr boundary (15). This family is characterized by the presence of prepollen, i.e., pollen of zoidogamous gymnosperms that had not yet developed the capacity to produce nonflagellated sperm delivered by a pollen tube (15, 37). In effect, after the P–Tr crisis, the prepollen condition never re-appeared in gymnosperm evolution. On the other hand, the temporary re-appearance of Jugasporites could indicate that the Ullmanniaceae survived outside Europe. The ancestry of Yuccites is unknown, but Voltzia has a close phylogenetic relationship with the widespread Late Permian Majonicaceae (35, 36). It should be noted that Voltzia is only distantly related to Voltziopsis (36), a dominant conifer in Early Triassic vegetation of Gondwana (10, 12).

It may be hypothesized that the source areas of the Early Triassic immigrants in Europe had a refugial character. After the P–Tr crisis, extreme fragmentation and range contraction of ancestral populations could have resulted in small, vicariant populations segregated into isolated refugia, where suitable habitats continued to exist for extensive periods. It is thought that such refugia are bounded by ecotonal regions where, despite loss of original genetic variation, selection pressure is active for the fixation of genotypic and phenotypic novelties and enhanced adaptive radiation (38). There is no direct evidence where refugional source areas for the immigrants could have been located. At least for the Late Permian, accumulating information from Africa and Arabia supports the existence of a wide area with mixed Gondwana and Euramerican floras (39, 40) that may have served as a consistent source for northward migrating gymnosperm species. Co-occurrence of Densoisporites and Voltziaceaesporites starts earlier in the P–Tr section of the Salt Range in Pakistan than in Europe (41), suggesting a southern refugium for the ancestral lineage of Yuccites. However, because of the surprising discovery of a variety of Mesozoic-type gymnosperms in the Lower Permian of Texas (42), North America also must be taken into consideration as a potential source area for European Triassic conifers.

Radiometric age determinations for rocks associated with the Olenekian-Anisian transition are still lacking, so that constraints on the duration of survival and recovery remain highly speculative. Analysis of 40Ar/39Ar data from a late Anisian tuff in New Zealand yielded a date of 242.8 ± 0.6 million years (Ma) before the present (43), whereas a mean single-grain zircon U/Pb date of 241.0 ± 0.5 Ma was obtained from the basal Ladinian of northern Italy (44, 45). Considering the U/Pb age of 251.4 ± 0.3 Ma for the P–Tr boundary in South China (46), and assuming similar duration of the Early Triassic (Induan through Olenekian) and the Anisian, an interpolated age of about 246 Ma might be a realistic estimate for the Olenekian–Anisian boundary. A duration of 4 to 5 Ma for the process of Early Triassic repopulation can thus be inferred. Assuming approximately equal extent for the four Early Triassic substages, the documented late Spathian change from a Pleuromeia-dominant vegetation to the Voltzia-dominant climax vegetation could have taken place within ≈0.5 Ma.

The recovery of equatorial, semi-arid conifer forest in Europe is approximately coeval with the delayed recovery of humid peat forest in higher latitudes, as evidenced by the Early Triassic “coal gap” (13, 14). In general, the progress of terrestrial ecosystem recovery after the P–Tr crisis appears to be in harmony with the situation in the marine biosphere. Diversity analysis and paleoecologic study of benthic invertebrate faunas has for some time indicated, most notably by the interruption of reef building (48), that shallow marine ecosystems too did not fully recover before the Middle Triassic (7, 47). Records of radiolarians suggest a similar delay in the return to precrisis levels of zooplankton productivity (49). Curiously, in comparison to all other major ecologic crises in Earth history, repopulation after the P–Tr crisis proceeded exceptionally slowly (6). A coherent scenario explaining the strongly delayed pathways leading to terrestrial and marine ecosystem recovery still needs to be established. Yet, the reported pattern of forest recovery in Europe exemplifies that an evaluation of vegetation change may contribute significantly to an understanding of the synergistic action of postcrisis habitat restoration, and migration and evolutionary processes.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Geological Institute of Hungary for making available sample material. We are grateful to Doug Erwin and other participants in the International Geological Correlation Program Project (no. 335), Biotic Recoveries from Mass Extinctions, for inspiration, helpful discussion, and comments on the topic. We thank Bill DiMichele, Robert Gastaldo, and Greg Retallack for offering constructive critiques. This work was supported by the Council for Earth and Life Sciences with financial aid from The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research. This paper is Netherlands Research School of Sedimentary Geology publication no. 990705, and University of Florida Contribution to Paleobiology publication no. 514).

Abbreviations

- P–Tr

Permian–Triassic

- Ma

million years

Footnotes

See commentary on page 13597.

References

- 1.Buffetaut E. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1990;82:169–174. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers N. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1990;82:175–185. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kauffman E G, Erwin D H. Geotimes. 1995;14(3):14–17. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kauffman E G, Harries P J. Geol Soc Sp Pap. 1996;102:15–39. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Harries P J, Kauffman E G, Hansen T A. Geol Soc Sp Pap. 1996;102:41–60. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Erwin D H. Trends Ecol Evol. 1998;13:344–349. doi: 10.1016/s0169-5347(98)01436-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Erwin D H. The Great Paleozoic Crisis. New York: Columbia Univ. Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hallam A, Wignall P B. Mass Extinctions and Their Aftermath. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eshet Y, Rampino M R, Visscher H. Geology. 1995;23:967–970. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Retallack G J. Science. 1995;267:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.267.5194.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Visscher H, Brinkhuis H, Dilcher D L, Elsik W C, Eshet Y, Looy C V, Rampino M R, Traverse A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:2155–2158. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.5.2155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Retallack G J. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1999;111:52–70. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Veevers J J, Conagham P J, Shaw S E. Geol Soc Am Sp Pap. 1994;288:187–196. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Retallack G J, Veevers J J, Morante R. Geol Soc Am Bull. 1996;108:195–207. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Poort R, Clement-Westerhof J A, Looy C V, Visscher H. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1997;97:9–39. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Retallack G J. J Paleontol. 1997;71:500–521. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mader D. Palaeoecology of the Flora in Buntsandstein and Keuper in the Triassic of Middle Europe. Vol. 1. Stuttgart: Fischer; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Grauvogel-Stamm L. Univ Louis Pasteur Strasbourg Inst Géol, Sci Géol Mém. 1978;50:1–225. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gall J C, Grauvogel-Stamm L, Nel A, Papier F. C R Acad Sci Paris, Earth Planet Sci. 1998;326:1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haas J, Tóth Makk Á, Oravecz Scheffer A, Góczán F, Oravecz J, Szabó I. Ann Inst Geol Publ Hung. 1988;65:1–356. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Broglio Loriga C, Góczán F, Haas J, Lenner K, Neri C, Oravecz Scheffer A, Posenato R, Szabó I, Tóth Makk Á. Mem Sci Geol. 1990;42:41–103. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brugman W A. Ph.D. thesis. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Utrecht Univ.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Góczán F, Oravecz-Scheffer A, Szabó I. Acta Geol Hung. 1986;29:233–259. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Traverse A. Paleopalynology. Boston: Unwin Hyman; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orłowska-Zwolińska T. Acta Palaeontol Pol. 1984;29:161–194. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Orłowska Zwolińska T. Bull Pol Acad Sci Earth Sci. 1985;33:107–117. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Delcourt H L, Delcourt P A. Quaternary Ecology - A Paleoecological Perspective. London: Chapman & Hall; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brinkhuis H, Visscher H. Lunar Planet Inst Contr. 1994;825:17. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang Z. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1996;91:121–142. [Google Scholar]

- 30.DiMichele W A, Davis J I, Olmstead R G. Taxon. 1989;38:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bateman R M, DiMichele W A. Biol Rev. 1994;69:345–417. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mapes G, Rothwell G W, Grauvogel-Stamm L. Am J Bot. 1997;84:137. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mägdefrau K. Paläobiologie der Pflanzen. 4th Ed. Jena, Germany: Fischer; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clement-Westerhof J A. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1984;41:51–166. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Clement-Westerhof J A. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1987;52:375–402. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clement-Westerhof J A. In: Origin and Evolution of Gymnosperms. Beck C B, editor. New York: Columbia Univ.; 1988. pp. 298–337. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Poort R J, Visscher H, Dilcher D L. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11713–11717. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levin D A, Wilson J B. In: Structure and Functioning of Plant Populations. Freysen A H J, Woldendorp J W, editors. Amsterdam: North-Holland; 1978. pp. 25–100. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Broutin J, Doubinger J, El Hamet M O, Lang J. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1990;66:243–261. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broutin J, Roger J, Platel J P, Anglioni L, Baud A, Bucher H, Marcoux J, Hasmi A H. C R Acad Sci Paris, Sér IIa. 1990;321:1069–1086. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Balme B E. In: Univ. Kansas Dept. Geol. Spec. Publ. 4, Stratigraphic Boundary Problems: Permian and Triassic of West Pakistan. Kummel B, Teichert C, editors. Lawrence, KS: Univ. Kansas Press; 1970. pp. 305–453. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chaney D S, Mamay S H, DiMichele W A. Geol. Soc. Am. Abstr. Prog. 1998. , A-312. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Retallack G J, Renne P R, Kimbrough D L. New Mex Mus Nat Hist Sci Bull. 1993;3:415–418. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Brack P, Rieber H, Mundil R. Albertiana. 1995;15:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mundil R, Brack P, Meier M, Rieber H, Oberli F. Earth Planet Sci Lett. 1996;141:137–151. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bowring S A, Erwin D H, Jin Y G, Martin M W, Davidek K, Wang W. Science. 1998;280:1039–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5366.1039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Schubert J K, Bottjer D J. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1995;116:1–39. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flügel E. Geol Soc Am Sp Pap. 1994;288:247–266. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kukawa Y. Palaeogeogr Palaeoclimatol Palaeoecol. 1996;121:35–51. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Brinkhuis H, Schiøler P. Geol Mijnbouw. 1996;75:193–213. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lundblad B. Medd Dansk Geol Foren. 1948;11:351–363. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Balme B E. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1995;87:81–323. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yaroshenko O P. Paleontol Zh. 1985;19:110–117. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Potonié R, Schweitzer H J. Paläontol Z. 1960;34:27–39. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Klaus W. Erdöl Z. 1964;80:119–132. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gomankov A V, Meyen S V. Trans Inst Akad Nauk SSSR. 1986;401:1–173. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Meyen S V. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1997;96:351–447. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Grauvogel-Stamm L. Palaeontographica B. 1972;140:1–26. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Grauvogel-Stamm L, Álvarez Ramis C. Cuad Geol Ibérica. 1996;20:229–243. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Visscher H, Brugman W A. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1981;34:115–128. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Warrington G. Q J Geol Soc London. 1970;126:183–223. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Warrington G. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1974;17:133–147. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Visscher H. Acta Bot Neerl. 1966;15:316–375. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Doubinger J, Bühmann D. Z Deut Geol Ges. 1981;132:421–449. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ecke H H. Ph.D. thesis. Göttingen, Germany: Georg August Univ.; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Reitz E. Geol Abh Hessen. 1985;86:1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 67.Reitz E. Geol Abh Hessen. 1988;116:105–112. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Reinhardt P, Schön M. Monatsber Deut Akad Wiss Berlin. 1967;9:747–758. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Reinhardt P, Schmitz W. Freiberger Forschungsh C. 1965;182:19–26. [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schulz E. Abh Zentr Geol Inst. 1965;1:257–287. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schulz E. Abh Zentr Geol Inst. 1966;8:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 72.Adloff M C, Doubinger J. Bull Serv Carte Géol Alsace Lorraine. 1969;22:131–148. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Doubinger J, López-Gómez J, Arche A. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1990;66:25–45. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Diez J B, Grauvogel-Stamm L, Broutin J, Ferrer J, Gisbert J, Linan E. C R Acad Sci Paris, Sér IIa. 1996;323:341–347. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Solé de Porta N, Calvet F, Torrentó L. Cuad Geol Ibérica. 1987;11:237–254. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Broutin J, Doubinger J, Gisbert J, Satta-Pasini S. C R Acad Sci Paris, Sér IIa. 1988;306:159–163. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ramos A, Doubinger J. C R Acad Sci Paris, Sér IIa. 1989;309:1089–1094. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Pittau Demelia P, Flaviani A. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1982;37:329–343. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Barabás-Stuhl Á. Acta Geol Acad Sci Hung. 1981;24:49–97. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Antonescu E, Patrulius D, Popescu I. Inst Geol Geof Dări de Seamă. 1976;62:3–30. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kilani-Mazraoui F, Razgallah-Gargouri S, Mannai-Tayech B. Rev Palaeobot Palynol. 1990;66:273–291. [Google Scholar]

- 82.Adloff M C, Doubinger J, Massa D, Vachard D. Rev Inst Franç Pétr. 1986;41:27–72. [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brugman W A, Visscher H. In: Subsurface Palynostratigraphy of Northeast Libya. El-Arnauti A, Owens B, Thusu B, editors. Benghazi, Libya: Garyounis Univ. Press; 1988. pp. 157–169. [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eshet Y. Geol Surv Isr Bull. 1990;81:1–57. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Eshet Y. Isr J Earth Sci. 1990;39:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Visscher H, Brugman W A. Mem Soc Geol It. 1988;34:121–128. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yin H, Zhang K, Wu S, Peng Y. In: The Palaeozoic-Mesozoic Boundary. Yin H, editor. Wuhan: China Univ. Geosci. Press; 1996. pp. 3–28. [Google Scholar]