Abstract

Viral entry into susceptible host cells typically results from multivalent interactions between viral surface proteins and host entry receptors. In the case of Sin Nombre virus (SNV), a New World hantavirus that causes hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome, infection involves the interaction between viral membrane surface glycoproteins and the human integrin αvβ3. Currently, there are no therapeutic agents available which specifically target SNV. To address this problem, we used phage display selection of cyclic nonapeptides to identify peptides that bound SNV and specifically prevented SNV infection in vitro. We synthesized cyclic nonapeptides based on peptide sequences of phage demonstrating the strongest inhibition of infection, and in all cases, the isolated peptides were less effective at blocking infection (9.0% to 27.6% inhibition) than were the same peptides presented by phage (74.0% to 82.6% inhibition). Since peptides presented by the phage were pentavalent, we determined whether the identified peptides would show greater inhibition if presented in a multivalent format. We used carboxyl linkages to conjugate selected cyclic peptides to multivalent nanoparticles and tested infection inhibition. Two of the peptides, CLVRNLAWC and CQATTARNC, showed inhibition that was improved over that of the free format when presented on nanoparticles at a 4:1 nanoparticle-to-virus ratio (9.0% to 32.5% and 27.6% to 37.6%, respectively), with CQATTARNC inhibition surpassing 50% when nanoparticles were used at a 20:1 ratio versus virus. These data illustrate that multivalent inhibitors may disrupt polyvalent protein-protein interactions, such as those utilized for viral infection of host cells, and may represent a useful therapeutic approach.

Peptide ligands that bind and recognize a protein surface and block specific protein-protein interactions can have broad applications as therapeutic reagents. For example, a virus particle can enter a host cell by specific binding interaction between a viral surface protein and a host cell surface receptor, thus initiating receptor-mediated endocytosis prior to infection. Viral infection can be prevented by blocking the viral protein-host receptor protein interaction. Specific peptides can be developed to block this protein-protein interface, either by mimicking one of the binding partners or through novel binding interactions.

We have chosen to develop peptide ligands capable of preventing infection by the Sin Nombre hantavirus (SNV). SNV is an NIAID category A pathogen responsible for hantavirus cardiopulmonary syndrome (HCPS), a syndrome for which there is currently no specific therapy and which has a case fatality rate approaching 40% (http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/diseases/hanta/hps/index.htm). Hantaviruses are enveloped, negative-sense RNA viruses. The hantavirus envelope is studded with two transmembrane glycoproteins, Gn and Gc, that result from posttranslational cleavage of a single glycoprotein precursor (20). It has previously been demonstrated that hantavirus entry into human endothelial cells is mediated by the interaction of viral surface glycoproteins with integrin αvβ3 expressed on the host cell surface (10, 41). Both Gn and Gc may be involved in viral entry, with Gn thought to primarily mediate attachment and with Gc further driving membrane fusion (30, 48). The entry of pathogenic hantaviruses such as SNV into human cells in vitro can be prevented by neutralizing antibodies directed against the virus or against the integrin receptor αvβ3. In addition, we previously reported the use of phage display to identify cyclic peptides which bind αvβ3 and block SNV infection of Vero E6 cells (11, 26). Such peptides have therapeutic potential without the potential side effects of monoclonal antibody therapies conventionally used to block this type of interaction (2, 9).

One challenge in developing inhibitors of viral infection through receptor blockade is attempting to use a monovalent ligand to block a multivalent interaction. According to Mammen et al. (31), multi- or polyvalent interactions involve the simultaneous binding of multiple ligands on one biological surface or molecule to multiple receptors on an opposing surface or molecule. In the case of virus-host interactions, multivalent interactions are characterized by multiple copies of protein/glycoprotein on the virion surface interacting with multiple copies of the receptor on the host cell surface. Collectively, these multivalent interactions can be much stronger than predicted by the sum of the corresponding monovalent interactions (31). As a result, very high concentrations of monovalent inhibitors may be required to achieve significant levels of inhibition of viral infection in vitro. However, it may be possible to generate multivalent inhibitors or therapeutic agents effective at much lower doses, particularly in light of the fact that there have been numerous reports in which multivalent ligands have demonstrated enhanced target recognition, with binding increases of up to 108 over their monovalent counterparts (31-33).

One ready approach to the development of multivalent therapeutic agents is the ligation of monovalent inhibitors to nonimmunogenic microspheres or nanoparticles. In addition to acting as carriers of anticancer agents (reviewed previously by Sinha et al. in reference 46), nanoparticles have been used to deliver, among other things, antituberculosis drugs, antibiotics, and at least in the case of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), antiviral agents (1, 3, 19, 29, 37, 50). Here, we sought to identify peptides that could bind directly to the SNV virion and inhibit infection. We began by using phage display to select cyclic nonapeptides capable of binding SNV. These peptides were tested for in vitro infection inhibition in the context of phage, as monovalent synthetic peptides, or in multivalent presentation on nanoparticles. Our results reemphasize the usefulness of phage display in identifying peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions and highlight the importance of inhibitor valency when multivalent biological processes are targeted.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents, virus, and monoclonal antibodies.

A phage display library expressing cysteine-constrained nonapeptides was purchased from New England Biolabs (Cambridge, MA). Cysteine-constrained peptides were synthesized in house as described below or by Biopeptide (San Diego, CA). The purity of the peptides was more than 95% as verified by high-performance liquid chromatography. Peptides were solubilized at a concentration of 10 mM in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4, and stored at −80°C until use. ReoPro, a Fab fragment of the chimeric human-murine monoclonal antibody c7E3, was purchased from Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN) and suspended in 0.01 M sodium phosphate, 0.15 M sodium chloride, and 0.001% polysorbate 80, pH 7.2. SiMAG/1-carboxyl (no. 1411) magnetic silica particles (nanoparticles) were obtained from Chemicell (Berlin, Germany), and peptides were coupled to the particles by using 1-ethyl-3-(3-dimethylaminopropyl) carbodiimide according to the two-step method provided by the manufacturer. Vero E6 cells (ATCC no. CRL 1586) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA), and fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) was purchased from Boehringer Mannheim (Indianapolis, IN). Reagents used for in-house synthesis of cyclic peptides include acetonitrile, diethyl ether, dichloromethane, methanol, dimethyl formamide (DMF), trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), anisole, peperidine, triisopropylsilane, thallium(III) trifluoroacetate [Tl(tfa)3] (obtained from Sigma-Aldrich [St. Louis, MO]), Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-Wang resin, and Fmoc amino acids. N,N′-diisopropylethylamine, 2-(1H-benzotriazole-1-yl)-1,1,3,3-tetramethyluronium hexafluorophosphate, 1-hydroxybenzotriazole hydrate, and N-methylpyrrolidone were obtained from Advanced ChemTech/CreoSalus (Louisville, KY). SNV strain SN77734 was used for all experiments. We previously described the isolation of this virus from a New Mexican deer mouse (5). Hantaan virus (HTNV) (HTN 76/118) and Prospect Hill virus (PHV-1) were provided by Ho Wang Lee and Ric Yanagihara (University of Hawaii), respectively.

Purification of polyclonal antibodies.

We previously obtained sera from a rabbit immunized with the bovine serum albumin (BSA)-conjugated peptide LKIESSCNFDLHVPATTTQKYNQVDWTKKSS, which corresponds to residues 58 to 88 of Gn from SNV strain SN77734. We centrifuged the serum for 30 min at 10,000 × g and filtered the supernatant through sterile glass wool. A 1-ml HiTrap protein A HP column (GE Healthcare) was equilibrated with 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, and sera (diluted 1:10 in the same buffer) were applied to the column at 0.5 ml/min. The column was washed with 10 ml of 20 mM sodium phosphate, pH 7.0, and IgG was eluted with 0.1 M citric acid, pH 4.5. The acid was immediately neutralized with 1 M Tris-HCl, pH 9.0. The protein concentration was determined spectrophotometrically. To reduce nonspecific binding, this polyclonal antibody, referred to as anti-Gn-BSA, was panned against BSA prior to each round of panning against SNV. We obtained anti-SNV antibodies from human convalescent plasma (HCP) in the same manner. To reduce nonspecific binding, this polyclonal antibody, referred to as HCP, was panned against normal human serum prior to each round of panning against SNV.

Preparation and purification of UV-inactivated SNV.

SNV was propagated and the titer was determined in Vero E6 cells under strict standard operating procedures using biosafety level 3 facilities and practices (CDC registration number C20041018-0267). For the preparation of UV-inactivated SNV, we placed 100 μl of virus stock (typically 1.5 × 106 to 2 × 106 FFU/ml) in each well of a 96-well plate and subjected the virus to UV irradiation at 254 nm (∼5 mW/cm2). We established that virus inactivation was complete after 10 to 15 s of exposure by using a focus assay (4, 40).

Density gradient purification of SNV was performed as described previously (39). Briefly, we added 10 ml of UV-SNV to a 2-ml cushion of a 50% solution of OptiPrep (iodixanol, 5,5′-[(2-hydroxy-1-3 propanediyl)-bis(acetylamino)] bis [N,N′-bis (2,3-dihydroxypropyl-2,4,6-triiodo-1,3-benzenecarboxamide]) (Sigma-Aldrich) contained in a 14 by 89 mm polyallomer centrifuge tube (Beckman). This tube was placed in a TH641 swing bucket rotor (Sorvall) and centrifuged at 40,000 rpm for 3 h at 4°C. After centrifugation, we collected 4 ml of solution from the bottom of the tube and mixed it with 1 ml of a 50% OptiPrep solution. We added this to a 5-ml OptiSeal (Beckman) tube and centrifuged the tube at 65,000 rpm for 5 h at 4°C in an NVT90 rotor. We then collected 100-μl fractions from the bottom of the tube and determined the location and concentration of the virus proteins by quantitative Western blot analysis (data not shown). Viral particles appeared intact by electron microscopy (data not shown). Fractions that contained the viral particles were pooled and used in phage selection.

Isolation of SNV binding phage.

Phage display was performed as described previously, with minor modifications, by using a cyclic nonapeptide phage library (26). For the first round of panning, 1 ml of UV-SNV in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.6) buffer was coated onto 60- by 15-mm petri dishes (Nalge Nunc International, Naperville, IL) for a final concentration 0.3 μg of Gn/ml (2.41 × 1012 Gn/ml) and incubated overnight in a humidified chamber at 4°C. The following day, the plates were blocked for 1 h at room temperature with 5 mg/ml BSA in 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.6) buffer. The plates were washed six times with TBST (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% [vol/vol] Tween 20), and then the phage library was added to the plate at a phage concentration of 2 × 1011 in 1 ml TBST. The plate was gently rocked for 1 h at room temperature. Unbound phage were removed by washing 10 times with 1 ml of TBST. Bound phage were then eluted by adding 500 μl of 2.14 mg/ml HCP for 1 h with gentle rocking at room temperature. The eluate containing the bound phage was removed and saved. A second round of elution was performed using 500 μl of 1.5 mg/ml anti-Gn-BSA. Phage were amplified in Escherichia coli ER2738 bacteria and partially purified by polyethylene glycol precipitation. In subsequent rounds of panning, phage resulting from this first-round elution with HCP or anti-Gn-BSA were eluted exclusively with their corresponding antibodies. The binding, elution, and amplification steps were repeated using 2.41 × 1012 Gn/ml of UV-SNV for the second through fourth and second and third rounds of HCP and anti-Gn-BSA elutions, respectively, while 1.77 × 1012 Gn/ml was used for the fifth and sixth and fourth through sixth rounds, respectively.

Nucleotide sequencing and sequence analysis.

After selection and amplification of the phage library on SNV, automated nucleotide sequencing derived the peptide sequence on the surface of the phage (DNA Research Services, Department of Pathology, University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, NM). Double-stranded DNA was prepared according to the manufacturer's specifications using the Qiagen QIAprep spin miniprep kit (Valencia, CA). DNA was amplified according to the manufacturers' specifications using the ABI Prism BigDye terminator 3.1 kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and the −96 gIII sequencing primer (New England Biolabs, Cambridge, MA). The reactions were purified using CentriSep spin columns (Princeton Separations, Adelphia, NJ). The samples were then dried, resuspended in formamide, and denatured. Sequencing was performed on a Hitachi 3100 gene analyzer (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA).

Sequence alignment of each peptide to human αvβ3 integrin was performed in a pairwise fashion. Alignments were performed using the Gap program, which is based on the algorithm of Needleman and Wunsch (36). We employed a Blosum62 scoring matrix, which has previously been shown to be effective for detecting protein sequence similarity based on evolutionary rates and analyzed amino acid pairs in blocks of aligned protein segments rather than individually as in earlier Dayhoff rule-based programs (13). The gap shift limit for αvβ3 was set at 12 and that for the peptide was set at 10. A quality score with a standard deviation was generated. The quality score for the alignment to any point is equal to the sum of the scoring matrix values of the matches in that alignment, less the gap-creation penalty times the number of gaps in that alignment, less the gap-extension penalty times the total length of all gaps in that alignment. We generated P values by performing 100 randomized alignments while preserving the amino acid composition (see the statistics of sequence similarity scores at the website for the National Center for Biotechnology Information, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/tutorial/Altschul-1.html). The unpaired Student's t test was used to generate a P value for each peptide alignment to SNV.

In-house peptide synthesis.

For peptide synthesis, we used a ThuraMed automatic peptide synthesizer model 100 (ThuraMed/CreoSalus, Louisville, KY), along with amino acids at 5 equivalents of Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-Wang resin. Resin was swollen by three 30-min incubations in N-methylpyrrolidone. Fmoc deprotections were performed with 20% piperidine in DMF and washed alternately with DMF and methanol. Linear peptides were synthesized using standard Fmoc chemistry from the Fmoc-Cys(Trt)-Wang resin (0.6 mmol/g), with Cys as the final amino acid. Peptide was cyclized on resin according to the method of D. Limal et al. (28). Briefly, resin was suspended in cold 0.4 M Tl(tfa)3 and 4.5% anisole in DMF and mixed for 4 h at room temperature. The resin was washed three times each with dichloromethane and diethyl ether, then dried under vacuum for 18 h. For cleavage and deprotection of the peptides, we used 3 ml of TFA-triisopropylsilane-H2O (95/2.5/2.5) for 0.1 g of resin. The solution was mixed at room temperature for 4 h and then filtered. The filter was washed with two volumes of TFA, and this wash was added to the original filtrate, all of which was then concentrated to approximately 2 ml by using a rotary evaporator (BUCHI Labortechnik AG, Flawil, Switzerland). Crude peptide was precipitated by dropwise addition to 100 ml cold diethyl ether and precipitated overnight at −20°C. Precipitate solution was centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 5 min at 4°C and washed six times with cold diethyl ether. Crude peptide was dried under vacuum for 18 h.

Crude peptide was purified using a binary gradient high-pressure liquid chromatography system (LabAlliance, State College, PA). Briefly, 20 mg of crude peptide was dissolved in 200 μl of TFA plus 400 μl of acetonitrile and then filtered through a 0.45-μm glass fiber filter. The volume was increased by the addition of 3.5 ml of 30% acetonitrile-0.3% TFA in H2O with the final volume adjusted to 5 ml with H2O. For peptide purification by high-pressure liquid chromatography, we used a 30- by 250-mm Hyperprep HS C18 column (Thermo Electron Corp., Bellefonte, PA) with a flow rate of 25 ml/min and a gradient from 10% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA to 60% acetonitrile, 0.1% TFA over 80 min. The peptide peak was isolated, frozen, and then lyophilized.

Immunofluorescence assay.

Twenty-four hours prior to beginning the immunofluorescence assay, duplicate wells of 104 Vero E6 cells/well were plated onto Lab-Tek 16-well chamber slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) by using minimal essential medium (MEM) (Gibco, Grand Island, NY) with 2.5% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and incubated at 37°C. SNV strain SN77734 (5) (2,000 to 3,000 FFU/ml) in MEM-2.5% FBS was mixed 1:1 with medium, phage at 2 × 109 phage/μl, 1 mM peptide, or 1 × 104 or 5 × 104 peptide-coated nanoparticles, and this virus mixture was incubated for 1 h at 37°C in a biosafety level 3 facility (Centers for Disease Control registration number C20041018-0267). Confluent Vero E6 cells were washed once with PBS, and 100 μl of virus mixture was added directly to the cells and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. When combination treatments were performed with anti-integrin peptides, these peptide or peptide-coated nanoparticles were incubated on the cells for 1 h at 37°C prior to addition of virus or anti-SNV peptide-virus mixture. In both cases, the virus mixture was subsequently removed by aspiration. The cells were washed twice with PBS, and MEM-2.5% FBS medium was added. After 24 to 36 h, the cells were fixed in 300 μl/well ice-cold methanol-acetone (50:50) and the slide was maintained at 4°C until staining. Cells were washed twice with PBS before staining and then overlaid with 100 μl of a 1:10,000 dilution of polyclonal rabbit anti-SNV recombinant N antibody (4) in PBS. After 1 h in a humidified chamber at 37°C, we added 50 μl of 1:500 FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG in PBS and then washed the cells three times in PBS. For counterstaining, we used 200 μl of 1:105 Evans blue (wt/vol) for 3 to 5 min and then rinsed with water. After mounting, foci were counted by fluorescence microscopic examination using a Zeiss Axioskop fluorescence microscope. To determine the number of SNV foci added to each well, we used control wells that lacked any inhibitor. The percent inhibition was calculated as the number of infected cells relative to the untreated controls.

MVE calculations and statistical analysis.

Multivalent enhancement ratio (MVE) calculations were based on the method of Montet et al. (35). Briefly, MVE is traditionally calculated as 50% of its maximum potential inhibitory concentration (IC50) or the 50% effective concentration (EC50) of the monovalent peptide divided by the IC50 or EC50 of the multivalent peptide-coated nanoparticle. In this report, we also used a modification of the MVE calculation, defined as the concentration of monovalent peptide divided by the concentration of the peptide on nanoparticles giving equivalent or higher percent inhibition relative to monovalent presentation. In the case of peptide-coated nanoparticles, MVE can be reported per mole of attached peptide or per mole of nanoparticle and is indicated where applied. Statistical analyses were performed on replicate samples by using an unpaired Student's t test. The mean ± standard error of the mean or ± the standard deviation is represented, and significance (the P value was <0.05 or P <0.0001, as indicated) is reported where appropriate.

RESULTS

Identification of SNV binding peptide-bearing phage that block infection of host cells.

In order to identify peptides capable of preventing SNV infection of host cells, we used repeated selection of a cyclic nonapeptide phage display library panned against purified UV-treated SNV. To enrich for phage with potential virus-neutralizing activity, we specifically eluted phage with either antibody purified from human convalescent plasma (HCP) demonstrated to neutralize viral infection in vitro or polyclonal antibody, developed for previous work, prepared against a short stretch of the Gn surface glycoprotein of SNV (anti-Gn-BSA). This stretch of SNV, previously shown to be an immunodominant linear epitope of SNV Gn in humans with HCPS (15, 18), shares 45.2% amino acid sequence identity with Hantaan virus (HTNV) and 51.6% identity with the nonpathogenic hantavirus PHV. Although the anti-Gn-BSA antibody was not a potent neutralizer of SNV infection (Table 1), we also wished to identify peptides with specific binding activity against SNV, so phage elution with this antibody was continued. After six rounds of panning and amplification of HCP-eluted phage and, in parallel, five rounds of panning and amplification using anti-Gn-BSA, peptide sequences were determined for 55 selected plaques by amplification of the corresponding region of the phage genome (Table 1). These peptide-bearing phage were tested for their abilities to inhibit SNV infection in a focus reduction test in Vero E6 cells. Anti-Gn-BSA and HCP were used as controls along with ReoPro, a commercially available Fab fragment which shows some inhibition of SNV infection in vitro by binding integrin β3. Phage were sorted into four groups based on their ability to block SNV infection. As shown in Table 1, 15 peptide-bearing phage (groups 3 and 4) that showed inhibition at or above 60% compared to the untreated control were identified.

TABLE 1.

Inhibition with peptide-bearing phages

| Peptide sequence or controla | Peptide inhibitionc | P valueb |

|---|---|---|

| HCP eluted | ||

| Group 1 (<30%) | ||

| CTNPESLTC | 9 (9) | 0.0982 |

| CKHHNWWTC | 12 (12) | 0.8981 |

| CSLRTYAAC | 12 (6) | 0.0353 |

| CFSSARLSC | 13 (6) | 0.8836 |

| CQRTTEANC | 16 (6) | 0.0078 |

| CTGYHNNTC | 16 (6) | 0.0001 |

| CSQWLQGS | 22 (5) | 0.0011 |

| CNSMWVRNC | 25 (6) | 0.1999 |

| Group 2 (30 to 59%) | ||

| CHTLPHTKC | 35 (6) | 0.0503 |

| CDLLLPGRC | 35 (6) | |

| CSTTNATWC | 36 (10) | 0.6621 |

| CHGSTKWAC | 39 (5) | 0.0011 |

| CYRTQFTQC | 39 (3) | 0.3021 |

| CTPLSTLQC | 40 (25) | 0.0142 |

| CTPGRSATC | 40 (4) | 0.0077 |

| CNPMHSRTC | 44 (3) | 0.0563 |

| CKPSTSGQC | 45 (3) | 0.0151 |

| CNKQFSAAC | 48 (1) | 0.2084 |

| CSPYAKHNC | 50 (6) | 0.0208 |

| CHSLRNAFC | 56 (5) | 0.0835 |

| CQGSPYRHC | 59 (10) | 0.0717 |

| Group 3 (60 to 79%) | ||

| CSAGAPEFC | 60 (8) | 0.0813 |

| CTQSGLLSC | 61 (20) | 0.0063 |

| CQVLNGNHC | 61 (6) | 0.8863 |

| CKSFTTTRC | 61 (14) | 0.0005 |

| CTYPYPKFC | 64 (12) | 0.0053 |

| CKSTFSPNC | 65 (11) | 0.3406 |

| CTSAAVHMC | 68 (8) | 0.0030 |

| CQPHLPWHC | 68 (6) | 0.3193 |

| CQTTNWNTC* | 74 (4) | 0.4673 |

| CSASTESLC* | 75 (5) | 0.0711 |

| Group 4 (>80%) | ||

| CLVRNLAWC* | 83 (5) | 0.2326 |

| HCP (1:400 dilution) | 100 (0) | |

| ReoPro | 68 (4) | |

| Media control | 0 (6) | |

| Gn-BSA antibody eluted | ||

| Group 1 (<30%) | ||

| CTTHISQTC | 9 (6) | 0.5428 |

| CHPSKALQC | 13 (9) | 0.0095 |

| CERLNLPQC | 14 (4) | 0.1709 |

| CTDNALKAC | 15 (8) | 0.1885 |

| CYKMDNHTC | 19 (6) | 1.0000 |

| CHVLDPHLC | 21 (5) | 0.5428 |

| CSRNHILTC | 25 (7) | 0.0015 |

| Group 2 (30 to 59%) | ||

| CVMSKHQHC | 30 (6) | 0.4882 |

| CLMGSSHSC | 32 (13) | 0.0038 |

| CPSHYTQAC | 34 (8) | 0.2771 |

| CHADQLPMC | 39 (3) | 0.0138 |

| CLPTPHHVC | 41 (2) | 0.0002 |

| CQLSLAPYC | 41 (11) | 0.3990 |

| CTFHSPRFC | 43 (7) | 0.9021 |

| CYATTLGAC | 45 (6) | 0.0483 |

| CGPSLRGVC | 45 (3) | 0.0006 |

| CFNTHTANC | 47 (16) | 0.0347 |

| CPGHHLSHC | 48 (10) | 0.5794 |

| CNSPKGKPC | 53 (3) | 0.6765 |

| Group 3 (60 to 79%) | ||

| CQWPGQSGC | 60 (8) | 0.0982 |

| CNSSSPTAC | 61 (23) | 0.0400 |

| CHQLMQNLC | 65 (16) | 0.0219 |

| CQATTARNC* | 78 (7) | 0.1741 |

| ReoPro | 70 (4) | |

| Gn-BSA antibody (1:40 dilution) | 21 (3) | |

| Media control | 0 (4) |

Peptides with significant homology to human integrin β3 are shown in bold. Numbers after groups indicate percent inhibition of infection in Vero E6 cells. Asterisks indicate the peptides synthesized for subsequent experiments.

P values for this comparison were determined by using an unpaired Student's t test.

Peptide-bearing phages were added at 109 phage/μl in a final volume of 50 μl. ReoPro was used at 40 μg/ml. Four tests were conducted per sample type, and mean percent inhibitions, along with standard deviations (in parentheses) are given.

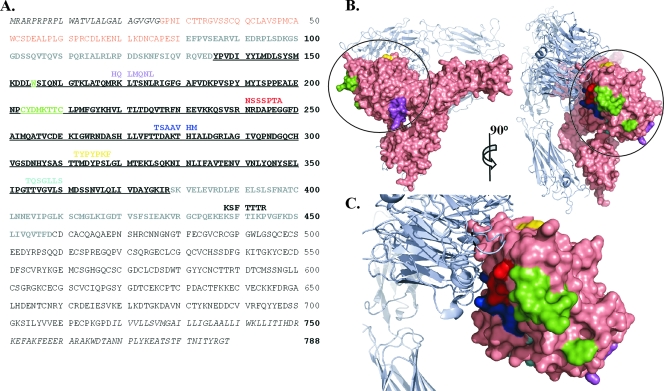

In order to identify any homology to known or potential entry receptors, each peptide sequence was compared to the amino acid sequence of the known host cell entry receptor, human β3 integrin, and also to a current database of human protein sequences (taxid 9606) by using the Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/BLAST/BLAST.cgi), with search parameters automatically adjusted to accommodate short peptide sequences. Six of the group 3 peptides showed some homology to β3 (P values of <0.05). Mapping the regions of peptide alignment onto the three-dimensional crystal structure of integrin β3 (49) revealed that five of the six peptides are homologous to regions within the βA domain, near the binding site for ReoPro (Fig. 1), while the sixth peptide aligns just outside the βA domain. In a BLAST search to identify human proteins with homology to the identified peptides, none of the alignments clearly identified cell surface receptors which would be likely candidates for alternative viral entry receptors.

FIG. 1.

Inhibitory peptides identified by phage display show homology to the βA domain of integrin β3. (A) Pairwise alignment of peptide sequences from phage showing greater than 60% inhibition of SNV infection versus the cellular entry receptor integrin β3. Residues comprising the signal peptide, transmembrane region, and cytoplasmic tail of β3 were not included in the pairwise alignment (shown in italics). The PSI domain of integrin β3 is shown in orange, the hybrid domain is shown in gray, and the βA domain is underlined. β3 residues outlining the ReoPro binding site are shown in green. (B) Side and frontal view of integrin αvβ3 (PDB 1U8C [49]). β3 is shown in surface representation (salmon), and αv is shown as a light blue ribbon diagram. The βA domain of β3 is circled. Regions corresponding to the aligned peptides and the ReoPro binding site are colored as in panel A. (C) Enlargement of βA domain oriented as depicted on the right side of panel B. Graphics for panels B and C were prepared with Pymol (DeLano Scientific LLC, San Carlos, CA).

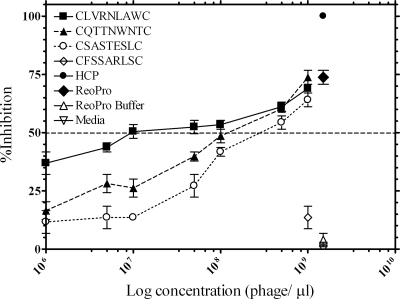

To further characterize the inhibitory peptide-bearing phage, four of the phage, bearing the peptides CLVRNLAWC, CQTTNWNTC, and CSASTESLC (Table 1, groups 3 and 4) as well as a control, bearing the peptide CFSSARLSC (Table 1, group 1), were examined for their ability to inhibit SNV entry in a dose-dependent manner (Fig. 2). The concentration of each peptide-bearing phage that produced 50% of its maximal potential inhibitory effect (IC50) was determined. IC50s ranged from 3.5 × 105 to 7 × 108 phage particles per microliter. HCP inhibited infection at 100%, while the control sequence, CFSSARLSC, did not significantly inhibit viral entry.

FIG. 2.

Dose-response curves showing the activites of peptide-bearing phage in blocking SNV infection. Along with HCP (diluted 1:400), controls included ReoPro at 40 μg/ml and a phage bearing the control peptide (CFSSARLSC) used at 109 phage/μl. Buffer controls include medium and the phosphate buffer used to dilute ReoPro. IC50 values for phage-bearing peptides CLVRNLAWC, CQTTNWNTC, and CSASTESLC were 1.0 × 106, 3.5 × 105, and 7 × 108, respectively, as determined by nonlinear regression analysis. Data points represent the mean of experiments performed in duplicate, and error bars show ± the standard errors of the mean. The dotted line indicates 50% inhibition.

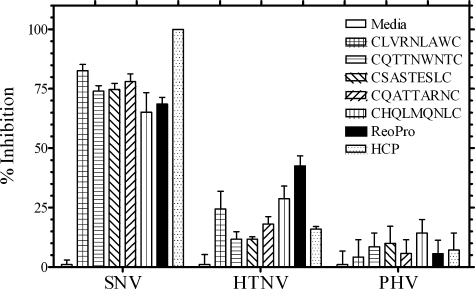

Specificity of identified peptide-bearing phage for blockade of SNV infection of host cells.

The most potent peptide-bearing phage from the HCP and anti-Gn-BSA-selected groups (Table 1) were examined further for their specificities in inhibiting SNV compared to two other hantaviruses, the pathogenic HTNV and the nonpathogenic PHV. As shown in Fig. 3, the selected peptide-bearing phage were highly specific for binding the SNV virion compared to HTNV and PHV as demonstrated by percent inhibition of infection in Vero E6 cells. Selected phage showed much lower levels of inhibition of HTNV infection compared to those of SNV and little to no inhibition of the nonpathogenic PHV. This selectivity could be observed despite the higher overall amino acid sequence identity between the SNV glycoprotein precursor and PHV (67%) compared with that of HTNV (54%). These data confirm that these peptide-bearing phage show specificities similar to those of the antibodies with which they were selected.

FIG. 3.

Focus reduction assay demonstrating specificities of hantavirus inhibition by peptide-bearing phage. The five peptide-bearing phage that were the most potent inhibitors of SNV were tested in a parallel focus assay for their abilities to inhibit infection of Vero E6 cells by SNV, HTNV, and PHV. Virus (2,000 PFU) and 50 μl of 1 × 109 phage were added to each well. Controls include HCP (1:400) and ReoPro (40 μg/ml). The mean percent inhibition of infection is indicated, and the standard errors (error bars) of the means are shown. There were two to four samples tested for each condition.

Potency of synthetic monovalent peptides.

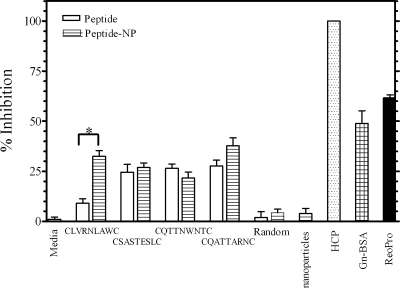

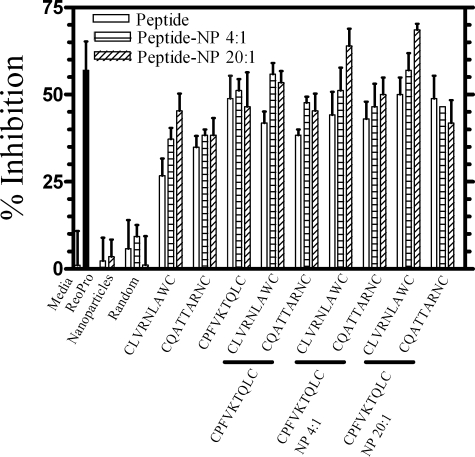

Next, we chemically synthesized a total of four peptides, three from the HCP-eluted phage (CLVRNLAWC, CSASTESLC, and CQTTNWNTC) and one from the anti-Gn-BSA-eluted phage (CQATTARNC). These peptides showed the greatest inhibition in the context of phage presentation, with inhibition values ranging from 74 to 83% compared to those of untreated controls. Each peptide was screened for the ability to inhibit SNV entry in vitro (Fig. 4). Although each of the peptides showed decreased inhibition compared to the same sequence in the phage display format, all but one of the peptides, CLVRNLAWC, averaged around 25% inhibition of SNV entry. Combinations of the peptides did not result in significantly increased inhibition (values ranged from 3.4 to 29.5% [data not shown]).

FIG. 4.

Focus reduction assay comparing the abilities of monovalent peptides versus those of multivalent peptide-coated nanoparticles to block SNV infection of Vero E6 cells. Prior to being added to confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells, SNV was treated with medium, 1 mM peptide, or peptide-coated nanoparticles (NP) at a nanoparticle:virus ratio of 4:1. ReoPro was added directly to Vero cells at a final concentration of 80 μg/ml, and HCP (1:400) and Gn-BSA antibody (1:40) were added directly to virus. The mean degrees of inhibition are indicated, and the standard errors (error bars) of the means are shown. The asterisk indicates statistical significance (P = 0.001). There were four samples for each condition.

Multivalent presentation of anti-SNV peptides on nanoparticles.

Since peptides presented by phage used in the original peptide selection process are naturally pentavalent and the monovalent synthetic peptides showed reduced inhibition, we chose to test whether the synthetic peptides would have greater inhibitory activities if presented in a multivalent format. We used carboxyl linkages to conjugate the cyclic peptides to multivalent nanoparticles (100 nm diameter) and tested these for the ability to inhibit viral infection in vitro. As shown in Fig. 4, in three out of four cases, nanoparticles coated with SNV-specific cyclic peptides showed an increase in inhibition over free peptide. Furthermore, CLVRNLAWC, the strongest inhibitor in the context of phage, showed a significant increase (P = 0.001) from 9.0% inhibition as free peptide to 32.5% inhibition of SNV infection with multivalent presentation on nanoparticles. Of note is the fact that the monovalent peptides were used at a concentration of 1 mM, whereas the peptide-coated nanoparticles, calculated to have a peptide valency of 742 and used at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of 4:1, were equally or more effective inhibitors at approximately 46 pM, when calculated on a molar nanoparticle basis, or 61.6 fM, when based on peptide molar equivalents. This result can be compared to the molar equivalents of peptide delivered by phage at 4.15 nM. However, compared to the sizes of the monovalent peptides, the contribution of steric factors introduced by both phage, with peptide presentation at one end of the approximately 900-nm-long and 7-nm-wide phage, and by bound nanoparticles, at 100-nm diameters, toward the decreased peptide concentration required for inhibition must be considered. In this scenario, although initiated by specific binding at their target sites, both peptide-bearing phage and peptide-coated nanoparticles have sufficient mass to block interactions at other, nonspecific sites, potentially resulting in enhanced inhibition not directly attributable to peptide specificity.

Peptide-coated nanoparticles were further examined for their abilities to inhibit SNV entry in a dose-dependent manner at nanoparticle-to-virus ratios of 4:1, 8:1, and 20:1 (Fig. 5A). Nonlinear regression analysis of the SNV-specific, peptide-coated nanoparticles showed dose-dependent inhibition of SNV entry into Vero E6 cells. In fact, for two of the peptides presented on nanoparticles, CQTTNWNTC and CQATTARNC, increasing the peptide-nanoparticle:virus ratio from 4:1 to 20:1 lead to increases in inhibition from 21.7 to 41.1% and from 37.7 to 51.4%, respectively. In contrast, nanoparticles alone or nanoparticles coated with a random, non-SNV-specific peptide sequence (CLLRMKSAC), failed to significantly inhibit SNV infection even at a nanoparticle:virus ratio of 20:1. In all cases, increasing the nanoparticle:virus ratio beyond 20:1 (40:1 and greater) did not increase inhibition, nor did attempts to increase the amount of peptide coupled to the nanoparticles (data not shown). As the nanoparticles used here are approximately the same size as the SNV virions (approximately 100 nm in diameter), these data are not surprising, as it is reasonable to expect a limit to the number of peptide-coated nanoparticles that can simultaneously access a given virion and going beyond that saturation point would fail to increase potency. Likewise, the effective peptide density on a nanoparticle is likely to be limited by the mass of the glycoproteins on the virion surface, and beyond this critical peptide density, no additional glycoprotein binding sites are expected to be accessible.

FIG. 5.

Activity and specificity of peptide-coated nanoparticles in blocking SNV infection. (A) Dose-response curves showing the peptide-coated nanoparticles (CLVRNLAWC, CSASTESLC, CQTTNWNTC, CQATTARNC, and random) used at various concentrations and incubated with SNV for 1 h prior to being added to confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells. Controls included ReoPro, medium only, and uncoated nanoparticles. ReoPro control was added directly to Vero cells at a final concentration of 80 μg/ml. After 24 to 36 h, monolayers were stained with polyclonal rabbit anti-SNV N (nucleocapsid) antibody, followed by FITC-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG antibody, and foci were counted. Each condition represents an N of 4 to 6. (B) Peptides and peptide-coated nanoparticle inhibitors of SNV were tested in a parallel focus assay for their abilities to inhibit infection of Vero E6 cells by SNV, HTNV, and PHV. Virus (2,000 PFU) and peptide (1 mM) or peptide-coated nanoparticles (at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of 4:1 or 20:1) were added to each well. Controls include medium, uncoated nanoparticles, and ReoPro (40 μg/ml). The mean degrees of inhibition are indicated, and the standard errors (error bars) of the means are shown. There were two samples tested for each condition.

To verify that the specificity of the peptides was not altered by binding to nanoparticles, peptide-coated nanoparticles were examined for their inhibition of SNV compared to HTNV and PHV. As shown in Fig. 5B, the peptide-coated nanoparticles were highly specific for targeting the SNV virion compared to HTNV and PHV as demonstrated by percent inhibition of infection in Vero E6 cells. As was the case for peptides presented by phage (Fig. 3), peptide-coated nanoparticles showed much lower levels of inhibition of HTNV infection compared to SNV and little to no inhibition of PHV.

We next wished to determine whether the peptides identified in this study bind the region of the SNV virion which mediates binding to integrin β3. To this end, we performed infection inhibition assays by using the anti-SNV peptides or peptide-coated nanoparticles in parallel or in combination with a peptide previously reported to block viral entry by binding to integrin β3, CPFVKTQLC, postulating that enhanced inhibition would be seen with combination treatment if the anti-SNV peptides blocked a region unique to that already blocked by the anti-integrin peptide (11, 26). As shown in Fig. 6, there was no significant difference in inhibition with the anti-β3 peptide CPFVKTQLC used as free peptide or as multivalent peptide-coated nanoparticles. There was some increase in inhibition with anti-SNV CLVRNLAWC-coated nanoparticles (at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of 20:1) used in combination with anti-β3 CPFVKTQLC-coated nanoparticles (at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of either 4:1 or 20:1), with specific increases from 56 to 64% and 54 to 69% inhibition, respectively. However, in an unpaired Student's t test, none of the combination treatments showed statistically significant improvements in inhibition above that of CPFVKTQLC treatment alone.

FIG. 6.

Focus reduction assay comparing the abilities of anti-SNV monovalent peptides and multivalent peptide-coated nanoparticles versus those of anti-integrin β3 peptides and coated nanoparticles to block SNV infection either alone or in combination treatments. In the case of the anti-SNV peptides, SNV was treated with medium, 1 mM peptide, or peptide-coated nanoparticles (NP), at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of 4:1 or 20:1, prior to being added to confluent monolayers of Vero E6 cells. In the case of the anti-integrin peptides, medium, 1 mM peptide, or peptide-coated nanoparticles, at a nanoparticle-to-virus ratio of 4:1 or 20:1, were added to the cells prior to addition of virus. ReoPro was added directly to Vero cells at a final concentration of 80 μg/ml. Mean degrees of inhibition are indicated, and the standard errors (error bars) of the means are shown. Each condition represents an N of 2. For the combination treatments shown in the last six groupings of the graph, the indicated anti-integrin treatment (shown below the bars) was paired with an anti-SNV treatment (shown above the bars).

DISCUSSION

Multivalent interactions are often central behind biological processes involving protein-protein interactions. Such is the case for viral entry into host cells, which is mediated by multiple interactions between viral surface proteins and host cell surface receptors (12, 16). Efficient blockade of such multivalent processes may not always be achievable by monovalent inhibitors. Here we have used phage display to identify disulfide-cyclized nonapeptides that specifically bind to SNV and prevent host entry, as demonstrated by in vitro infection inhibition assay. We have also demonstrated that for certain peptides, presentation in a multivalent format on nanoparticles may yield significantly more efficient viral inhibition while using lower concentrations compared to those needed to achieve comparable effects with monovalent inhibitors. Since there are currently no therapeutic agents available that specifically target SNV, the data reported here provide direction for the development and optimization of potent antiviral agents to prevent SNV infection and HCPS.

Here we identified peptide antagonists of SNV infection through the selection of cyclic nonapeptide-bearing phage. Peptide selection by phage display technology allows the identification of active peptides from as many as 1012 different sequences at low cost and in a time-efficient manner. In the development of inhibitors of protein-protein interactions, peptides can be highly potent and specific, and the use of cyclic peptides, such as those reported here, yields additional advantages of increased protease resistance and longer half-lives as well as improved conformational stability over linear peptides (45). Furthermore, peptides can act as lead compounds by providing a structural basis for the identification of nonpeptide mimetics when oral availability and increased potency are required. Peptides have been identified that can inhibit a number of cellular targets, including angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (17), melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis (8), vascular endothelial growth factor (14), and intracellular adhesion molecule 1 (44), to name but a few. Likewise, in addition to a large number of naturally occurring antimicrobial peptides, a number of additional peptides, either novel or based on cellular components, have been identified, including a 36-amino-acid peptide called enfuvirtide (Fuzeon; Roche) currently marketed to prevent HIV-1 infection of T cells (7, 27). The work reported here adds to the growing number of effective peptide inhibitors of agents of infectious diseases and emphasizes the utility of phage display in identifying such inhibitors.

Multivalent ligand presentation is often key to achieving effector or inhibitor activity in a biological system, and microspheres or nanoparticles can be important vehicles for achieving multivalency. For example, Montet et al. used 30-nm-diameter, aminated, cross-linked iron oxide nanoparticles coated with cyclo-RGD (cRGD) peptides to perform uptake and antiadhesion assays with integrin αvβ3-expressing endothelial cells and tumor cells (35) (20 RGD peptides per nanoparticle). Using the multivalent enhancement ratio (MVE) to quantify their results, described as the IC50 of free peptide/IC50 peptide displayed by nanoparticles, this group demonstrated an MVE of 38 for antiadhesion effects of cRGD-cross-linked iron oxide versus those of free cRGD (or an MVE of 760 calculated on a molar nanoparticle basis), along with an extension of the peptide blood half-life from 13 to 180 min (35). Youssef et al. reported a dramatic increase in therapeutic activity of nanoparticle-bound ampicillin over its free state in treating Listeria monocytogenes-infected athymic nude mice (50). This group, using ampicillin bound to polyisohexylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles approximately 187 nm in diameter (an ampicillin-to-polyisohexylcyanoacrylate ratio of 0.2:1), showed that 2.4 mg of nanoparticle-bound ampicillin had a greater therapeutic effect than 48 mg of free ampicillin (the equivalent of an MVE of 20). Bender et al. (3), using 475-nm-diameter polyhexylcyanoacrylate nanoparticles loaded with the HIV protease inhibitor saquinavir, demonstrated an IC50 of 0.39 nM while the value was 4.23 nM for free drug in HIV-infected human monocytes and macrophages in vitro, which is equivalent to an MVE of 10.8. Despite such impressive results, utilization of nanoparticles for surface delivery of antimicrobial agents has been underexploited. Two of the peptides reported here, CLVRNLAWC and CQATTARNC, showed improved inhibition over the free format when presented on nanoparticles at a 4:1 nanoparticle-to-virus ratio (9.0 to 32.5% and 27.6 to 37.6%, respectively), with CQATTARNC-mediated inhibition reaching more than 50% when nanoparticles were used at a 20:1 ratio relative to virus. Although we can only speculate as to why all the peptides did not show significant improvement with nanoparticle presentation, it may be a function of constraints upon the orientation required for binding the virion target. Since a carboxyl-amino linkage was utilized, all of the peptides should have some linkage to their N-terminal Cys residues. This possibility may have allowed the CLVRNLAWC and CQATTARNC peptides to achieve critical orientations required for inhibition, while simultaneously hindering critical orientations for the remaining peptides. Regardless, all the nanoparticle bound peptides showed comparable or enhanced levels of SNV inhibition at lower molar concentrations than the concentrations used for free peptide. Therefore, the results reported here for using nanoparticles as carriers of anti-SNV peptides highlight the importance of valency in antiviral agent presentation to maximize effectiveness and, in addition, demonstrate the broad potential of nanoparticles as carriers of therapeutic agents against SNV and other infectious diseases.

The two most important characteristics of nanoparticles used for the delivery of therapeutic agents are particle size and surface chemistry, both of which determine distribution and biological fate in vivo. The smaller size of nanoparticles over microparticles results in higher intracellular uptake and increased range of biological targets (reviewed previously by Mohanraj and Chen in reference 34). Surface hydrophobicity of nanoparticles also determines their in vivo fate. Upon intravenous administration, nanoparticles are able to pass through all capillaries (25) and can be rapidly removed from circulation. Also, blood proteins act as opsonins and adsorb to the surfaces of nanoparticles, facilitating phagocytic clearance by macrophages. This complication can be minimized by coating the surfaces of the nanoparticles with hydrophilic polymers, surfactants, or polyethylene glycol (34), which helps decrease opsonization and phagocytosis, thus increasing circulation time (21, 51). Therefore, opsonization minimization is important to the success of drug delivery via nanoparticles and to prolonged circulation time. Both of these factors must be optimized for in vivo use of therapeutic nanoparticle systems. Since the nanoparticles used in the work reported here contain a magnetic iron core, we will utilize nonmagnetic particles for in vivo toxicity and efficacy studies to optimize both the particle size and surface to achieve maximum inhibition with the anti-SNV cyclopeptides.

The approach used here to develop multivalent agents, through the ligation of monovalent inhibitors to microspheres or nanoparticles, is but one of myriad strategies for achieving multivalency. For example, a variety of dendrimers have been utilized for multivalent presentation of peptides as vaccines or inhibitors, including N-acetylneuraminic-acid-substituted dendrimers effective against Sendai virus and certain influenza strains (42) as well as lipopeptide dendrimers used to present disulfide-cyclized peptide inhibitors of foot-and-mouth disease (6, 43). Liposomes have been used to incorporate sialic acid gangliosides to prevent hemagglutination by influenza (22, 47) and synthetic multivalent carbohydrate ligands have been used to produce potent neutralizers of Shiga-like toxins (23). Although these are but a few of the many approaches to preparing multivalent ligands, we found the use of nanoparticles as described here to have some distinct advantages for use with peptide ligands. First, nanoparticles with surface chemistries for carboxyl or amino-peptide linkage are readily available commercially and procedures for the ligation of proteins or peptides to these surfaces are rapid and well documented. Furthermore, nanoparticles are available in a variety of sizes and surface coatings, both of which affect cellular uptake and clearance and which in turn allow for the optimization of both the peptide inhibitor as well as the carrier (21, 24, 34). In addition, the previously described clinical use of nanoparticle encapsulated delivery systems for breast cancer and HIV-1 therapeutic agents (29, 38) warrants the development of additional in vivo uses of nanoparticles for the delivery of therapeutic agents, such as those described here for in vitro prevention of hantavirus infection and disease.

In this investigation, we did not exhaustively examine the means of optimizing valency and presentation of the peptide inhibitors we identified for SNV. Additional work will be required to optimize both the inhibitory peptides and nanoparticle delivery system reported here before beginning in vivo efficacy and toxicity studies. However, it is of note that some of the combination treatments shown in Fig. 6 gave higher average inhibition levels than did the control Fab, ReoPro. In addition, although we can only speculate about this in the absence of direct binding experiments, the lack of additive inhibition when combining peptides selected to target the SNV virion with those selected to target integrin β3 suggests that anti-SNV peptides interact with a region of the SNV virion that interacts with integrin β3. As it is reasonable to expect that the panel of HCP-eluted peptides may contain some that interfere with fusion and others that block binding, we are continuing to screen peptides from Table 1 to identify those that may be useful for combination treatments to block binding and fusion. Meanwhile, our results emphasize the usefulness of phage display in identifying novel peptide inhibitors of protein-protein interactions. In addition, the dramatic increase in effectiveness of anti-SNV peptides presented on nanoparticles highlights the importance of inhibitor valency when multivalent biological processes are targeted. We propose that anti-SNV peptide-coated nanoparticles can be further optimized to be potent inhibitors of SNV infection and HCPS.

Acknowledgments

We thank Steve Jett for electron microscopy analysis of the purified UV-killed SNV.

This work was supported by the NCMR grant “Integrated Network of Ligand-Based Autonomous Bioagent Detectors” and by Public Health Service grants U01 AI 56618 (B.H.), U01 AI054779 (B.H.), and R56 AI034448 (R.S.L.). P.R.H. was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant T32 AI07538-06 (to B.H.).

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahmad, Z., S. Sharma, and G. K. Khuller. 2007. Chemotherapeutic evaluation of alginate nanoparticle-encapsulated azole antifungal and antitubercular drugs against murine tuberculosis. Nanomedicine 3:239-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baudouin, V., A. Crusiaux, E. Haddad, L. Schandene, M. Goldman, C. Loirat, and D. Abramowicz. 2003. Anaphylactic shock caused by immunoglobulin E sensitization after retreatment with the chimeric anti-interleukin-2 receptor monoclonal antibody basiliximab. Transplantation 76:459-463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bender, A. R., H. von Briesen, J. Kreuter, I. B. Duncan, and H. Rubsamen-Waigmann. 1996. Efficiency of nanoparticles as a carrier system for antiviral agents in human immunodeficiency virus-infected human monocytes/macrophages in vitro. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40:1467-1471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bharadwaj, M., C. R. Lyons, I. A. Wortman, and B. Hjelle. 1999. Intramuscular inoculation of Sin Nombre hantavirus cDNAs induces cellular and humoral immune responses in BALB/c mice. Vaccine 17:2836-2843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Botten, J., K. Mirowsky, D. Kusewitt, M. Bharadwaj, J. Yee, R. Ricci, R. M. Feddersen, and B. Hjelle. 2000. Experimental infection model for Sin Nombre hantavirus in the deer mouse (Peromyscus maniculatus). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 97:10578-10583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Oliveira, E., J. Villen, E. Giralt, and D. Andreu. 2003. Synthetic approaches to multivalent lipopeptide dendrimers containing cyclic disulfide epitopes of foot-and-mouth disease virus. Bioconjug. Chem. 14:144-152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dwyer, J. J., K. L. Wilson, D. K. Davison, S. A. Freel, J. E. Seedorff, S. A. Wring, N. A. Tvermoes, T. J. Matthews, M. L. Greenberg, and M. K. Delmedico. 2007. Design of helical, oligomeric HIV-1 fusion inhibitor peptides with potent activity against enfuvirtide-resistant virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104:12772-12777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Franklin, M. C., S. Kadkhodayan, H. Ackerly, D. Alexandru, M. D. Distefano, L. O. Elliott, J. A. Flygare, G. Mausisa, D. C. Okawa, D. Ong, D. Vucic, K. Deshayes, and W. J. Fairbrother. 2003. Structure and function analysis of peptide antagonists of melanoma inhibitor of apoptosis (ML-IAP). Biochemistry 42:8223-8231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gauvreau, G. M., A. B. Becker, L. P. Boulet, J. Chakir, R. B. Fick, W. L. Greene, K. J. Killian, P. M. O'byrne, J. K. Reid, and D. W. Cockcroft. 2003. The effects of an anti-CD11a mAb, efalizumab, on allergen-induced airway responses and airway inflammation in subjects with atopic asthma. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 112:331-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gavrilovskaya, I. N., E. J. Brown, M. H. Ginsberg, and E. R. Mackow. 1999. Cellular entry of hantaviruses which cause hemorrhagic fever with renal syndrome is mediated by β3 integrins. J. Virol. 73:3951-3959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hall, P. R., L. Malone, L. O. Sillerud, C. Ye, B. L. Hjelle, and R. S. Larson. 2007. Characterization and NMR solution structure of a novel cyclic pentapeptide inhibitor of pathogenic hantaviruses. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 69:180-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Haywood, A. M. 1994. Virus receptors: binding, adhesion strengthening, and changes in viral structure. J. Virol. 68:1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henikoff, S., and J. G. Henikoff. 1992. Amino acid substitution matrices from protein blocks. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 89:10915-10919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hetian, L., A. Ping, S. Shumei, L. Xiaoying, H. Luowen, W. Jian, M. Lin, L. Meisheng, Y. Junshan, and S. Chengchao. 2002. A novel peptide isolated from a phage display library inhibits tumor growth and metastasis by blocking the binding of vascular endothelial growth factor to its kinase domain receptor. J. Biol. Chem. 277:43137-43142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hjelle, B., F. Chavez-Giles, N. Torrez-Martinez, T. Yamada, J. Sarisky, M. Ascher, and S. Jenison. 1994. Dominant glycoprotein epitope of Four Corners hantavirus is conserved across a wide geographical area. J. Gen. Virol. 75:2881-2888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hlavacek, W. S., R. G. Posner, and A. S. Perelson. 1999. Steric effects on multivalent ligand-receptor binding: exclusion of ligand sites by bound cell surface receptors. Biophys. J. 76:3031-3043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, L., D. J. Sexton, K. Skogerson, M. Devlin, R. Smith, I. Sanyal, T. Parry, R. Kent, J. Enright, Q. L. Wu, G. Conley, D. DeOliveira, L. Morganelli, M. Ducar, C. R. Wescott, and R. C. Ladner. 2003. Novel peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 278:15532-15540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jenison, S., T. Yamada, C. Morris, B. Anderson, N. Torrez-Martinez, N. Keller, and B. Hjelle. 1994. Characterization of human antibody responses to four corners hantavirus infections among patients with hantavirus pulmonary syndrome. J. Virol. 68:3000-3006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Johnson, C. M., R. Pandey, S. Sharma, G. K. Khuller, R. J. Basaraba, I. M. Orme, and A. J. Lenaerts. 2005. Oral therapy using nanoparticle-encapsulated antituberculosis drugs in guinea pigs infected with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 49:4335-4338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jonsson, C. B., and C. S. Schmaljohn. 2001. Replication of hantaviruses. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:15-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kane, R. S., and A. D. Stroock. 2007. Nanobiotechnology: protein-nanomaterial interactions. Biotechnol. Prog. 23:316-319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kingery-Wood, J. E., K. W. Williams, G. B. Sigal, and G. M. Whitesides. 1992. The agglutination of erythrocytes by influenza virus is strongly inhibited by liposomes incorporating an analog of sialyl gangliosides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114:7303-7305. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitov, P. I., J. M. Sadowska, G. Mulvey, G. D. Armstrong, H. Ling, N. S. Pannu, R. J. Read, and D. R. Bundle. 2000. Shiga-like toxins are neutralized by tailored multivalent carbohydrate ligands. Nature 403:669-672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kohane, D. S. 2007. Microparticles and nanoparticles for drug delivery. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 96:203-209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kreuter, J. (ed). 1994. Colloidal drug delivery systems, p. 219-342. Marcel Dekker, New York, NY.

- 26.Larson, R. S., D. C. Brown, C. Ye, and B. Hjelle. 2005. Peptide antagonists that inhibit Sin Nombre virus and Hantaan virus entry through the β3-integrin receptor. J. Virol. 79:7319-7326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lawless, M. K., S. Barney, K. I. Guthrie, T. B. Bucy, S. R. Petteway, Jr., and G. Merutka. 1996. HIV-1 membrane fusion mechanism: structural studies of the interactions between biologically-active peptides from gp41. Biochemistry 35:13697-13708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Limal, D., J. P. Briand, P. Dalbon, and M. Jolivet. 1998. Solid-phase synthesis and on-resin cyclization of a disulfide bond peptide and lactam analogues corresponding to the major antigenic site of HIV gp41 protein. J. Pept. Res. 52:121-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lori, F., S. A. Calarota, and J. Lisziewicz. 2007. Nanochemistry-based immunotherapy for HIV-1. Curr. Med. Chem. 14:1911-1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mackow, E. R., and I. N. Gavrilovskaya. 2001. Cellular receptors and hantavirus pathogenesis. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 256:91-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mammen, M., S. K. Choi, and G. M. Whitesides. 1998. Polyvalent interactions in biological systems: implications for design and use of multivalent ligands and inhibitors. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 37:2755-2794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mammen, M., G. Dahmann, and G. M. Whitesides. 1995. Effective inhibitors of hemagglutination by influenza virus synthesized from polymers having active ester groups. Insight into mechanism of inhibition. J. Med. Chem. 38:4179-4190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mammen, M., K. Helmerson, R. Kishore, S. K. Choi, W. D. Phillips, and G. M. Whitesides. 1996. Optically controlled collisions of biological objects to evaluate potent polyvalent inhibitors of virus-cell adhesion. Chem. Biol. 3:757-763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mohanraj, V. J., and Y. Chen. 2006. Nanoparticles—a review. Trop. J. Pharm. Res. 5:561-573. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Montet, X., M. Funovics, K. Montet-Abou, R. Weissleder, and L. Josephson. 2006. Multivalent effects of RGD peptides obtained by nanoparticle display. J. Med. Chem. 49:6087-6093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Needleman, S. B., and C. D. Wunsch. 1970. A general method applicable to the search for similarities in the amino acid sequence of two proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 48:443-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pandey, R., S. Sharma, and G. K. Khuller. 2006. Chemotherapeutic efficacy of nanoparticle encapsulated antitubercular drugs. Drug Deliv. 13:287-294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Perez, E. 2005. New antitubulin agents. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Miami Breast Cancer Conference, Miami, FL.

- 39.Prescott, J., P. R. Hall, V. S. Bondu-Hawkins, C. Ye, and B. Hjelle. 2007. Early innate immune responses to Sin Nombre hantavirus occur independently of IFN regulatory factor 3, characterized pattern recognition receptors, and viral entry. J. Immunol. 179:1796-1801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Prescott, J., C. Ye, G. Sen, and B. Hjelle. 2005. Induction of innate immune response genes by Sin Nombre hantavirus does not require viral replication. J. Virol. 79:15007-15015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Raymond, T., E. Gorbunova, I. N. Gavrilovskaya, and E. R. Mackow. 2005. Pathogenic hantaviruses bind plexin-semaphorin-integrin domains present at the apex of inactive, bent alphavbeta3 integrin conformers. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 102:1163-1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Reuter, J. D., A. Myc, M. M. Hayes, Z. Gan, R. Roy, D. Qin, R. Yin, L. T. Piehler, R. Esfand, D. A. Tomalia, and J. R. Baker, Jr. 1999. Inhibition of viral adhesion and infection by sialic-acid-conjugated dendritic polymers. Bioconjug. Chem. 10:271-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rosa, B. A., and C. L. Schengrund. 2005. Dendrimers and antivirals: a review. Curr. Drug Targets Infect. Disord. 5:247-254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shannon, J. P., M. V. Silva, D. C. Brown, and R. S. Larson. 2001. Novel cyclic peptide inhibits intercellular adhesion molecule-1-mediated cell aggregation. J. Pept. Res. 58:140-150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sillerud, L. O., and R. S. Larson. 2005. Design and structure of peptide and peptidomimetic antagonists of protein-protein interaction. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 6:151-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sinha, R., G. J. Kim, S. Nie, and D. M. Shin. 2006. Nanotechnology in cancer therapeutics: bioconjugated nanoparticles for drug delivery. Mol. Cancer Ther. 5:1909-1917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Spevak, W., J. O. Nagy, D. H. Charych, M. E. Scaefer, J. H. Gilbert, and M. D. Bednarski. 1993. Polymerized liposomes containing C-glycosides of sialic acid: potent inhibitors of influenza virus in vitro infectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 115:1146-1147. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tischler, N. D., A. Gonzalez, T. Perez-Acle, M. Rosemblatt, and P. D. Valenzuela. 2005. Hantavirus Gc glycoprotein: evidence for a class II fusion protein. J. Gen. Virol. 86:2937-2947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Xiong, J. P., T. Stehle, S. L. Goodman, and M. A. Arnaout. 2004. A novel adaptation of the integrin PSI domain revealed from its crystal structure. J. Biol. Chem. 279:40252-40254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Youssef, M., E. Fattal, M. J. Alonso, L. Roblot-Treupel, J. Sauzieres, C. Tancrede, A. Omnes, P. Couvreur, and A. Andremont. 1988. Effectiveness of nanoparticle-bound ampicillin in the treatment of Listeria monocytogenes infection in athymic nude mice. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 32:1204-1207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zahr, A. S., C. A. Davis, and M. V. Pishko. 2006. Macrophage uptake of core-shell nanoparticles surface modified with poly(ethylene glycol). Langmuir 22:8178-8185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]