Abstract

The prevalence of woody species in oceanic islands has attracted the attention of evolutionary biologists for more than a century. We used a phylogeny based on sequences of the internal-transcribed spacer region of nuclear ribosomal DNA to trace the evolution of woodiness in Pericallis (Asteraceae: Senecioneae), a genus endemic to the Macaronesian archipelagos of the Azores, Madeira, and Canaries. Our results show that woodiness in Pericallis originated independently at least twice in these islands, further weakening some previous hypotheses concerning the value of this character for tracing the continental ancestry of island endemics. The same data suggest that the origin of woodiness is correlated with ecological shifts from open to species-rich habitats and that the ancestor of Pericallis was an herbaceous species adapted to marginal habitats of the laurel forest. Our results also support Pericallis as closely related to New World genera of the tribe Senecioneae.

Floras of oceanic islands have a high proportion of woody species, a feature that has long attracted the attention of evolutionary biologists (1). It is estimated that at least 65% of the endemics of the archipelagos of Hawaii, Canaries, Juan Fernández, and St. Helena are woody (2–5), whereas their continental relatives are predominantly herbaceous. Striking examples of the development of woodiness in oceanic islands are characterized by Plantago (Plantaginaceae) in Hawaii, Juan Fernández, St. Helena, and the Canary Islands (2, 6), Dendroseris (Asteraceae) from the Juan Fernández islands (7); Echium (Boraginaceae) and the woody Sonchus alliance (Asteraceae) in the Macaronesian islands (8, 9), and the “tree Compositae” of St. Helena (2). Woodiness is also prevalent in families from the high mountain islands of the South American Andes [e.g., Espeletia (Asteraceae)] and of East Africa [e.g., Dendrosenecio (Asteraceae)] (10, 11).

The origin and evolution of plant woodiness in oceanic islands has generated considerable controversy. Carlquist (1) considered woodiness in islands to be derived secondarily, whereas others have proposed that it represents a plesiomorphic feature of continental floras that found refuge in oceanic islands after major climatic and/or geological changes in the mainland (12). The first hypothesis assumes that woodiness in islands is developed secondarily as a continuation of the primary xylem (13).

The Macaronesian islands are composed of the archipelagos of Azores, Madeira, Selvagens, Canaries, and Cape Verde, located between 15o and 40o N latitude in the Atlantic Ocean. These islands have a unique biota that traditionally has been linked to the subtropical forest that existed in the Mediterranean region during the Tertiary (12). This link is supported primarily by fossil evidence. The genera Apollonias (Lauraceae), Clethra (Clethraceae), Dracaena (Dracaenaceae), Ocotea (Lauraceae), Persea (Lauraceae), and Picconia (Oleaceae) have species in Macaronesia but not in the Mediterranean basin and have been recorded in sites dating from the Tertiary of southern Europe (14, 15). Most species of these genera occur in the laurel forest, one of the most distinctive ecological zones of Macaronesia. This forest is situated on northern slopes of the islands and is under the direct influence of the northeastern trade winds. Four of the other major ecological zones (i.e., coastal desert–lowland xerophytic belt, lowland scrub, pine forest, and high-altitude desert) are more arid because they are not affected directly by these trade winds.

Pericallis is the only genus in the tribe Senecioneae (Asteraceae) endemic to Macaronesia. The tribe is considered to comprise three distinct subtribes [Blennospermatinae, Senecioninae, and Tussilaginae (16)]. Pericallis is placed in the subtribe Senecioninae. The genus has 15 species confined to the Canaries, Azores, and Madeira (Table 1). Three of the species (P. appendiculata, P. aurita, and P. malviflora) occur on several islands, but none of the species occurs in more than one archipelago. Most species are restricted to the laurel forest, but three occur in the pine forest or the lowland scrub (Table 1). The genus exhibits considerable variation in flower color (white, bluish, pink, or purple), although none of the species has the yellow ray florets that are predominant in the Senecioneae.

Table 1.

Distribution, ecology, and habit of the 15 species of Pericallis in the Macaronesian Islands

| Taxon | Archipelago | Island | Ecology | Habit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. appendiculata | Canaries | C G P T | Laurel forest | Woody |

| P. aurita | Madeira | M S | Laurel forest | Woody |

| P. cruenta | Canaries | T | Pine forest | Herbaceous |

| P. echinata | Canaries | T | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. hadrosoma | Canaries | C | Laurel forest | Woody |

| P. hansenii | Canaries | G | Laurel forest | Woody |

| P. lanata | Canaries | T | Pine forest | Woody |

| P. malviflora | Azores | A F J I O R | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. multiflora | Canaries | T | Laurel forest | Woody |

| P. murrayi | Canaries | H | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. papyracea | Canarie | P | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. species nova | Canaries | T | Pine forest | Herbaceous |

| P. steetzii | Canaries | G | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. tussilaginis | Canaries | C T | Laurel forest | Herbaceous |

| P. webbii | Canaries | C | Laurel forest, pine forest, and lowland scrub | Herbaceous |

A, Santa Maria; C, Gran Canaria, F, Faial; G, La Gomera; H, El Hierro; I, São Miguel; J, São Jorge; M, Madeira, O, Pico; P, La Palma, R, Terceira; S, Porto Santo; T, Tenerife.

Pericallis is unusual among Macaronesian endemics because of the presence of both woody (six) and herbaceous (nine) species (Table 1) (17). Two of the woody species are small phanerophytes with an almost decumbent habit (P. appendiculata and P. hansenii), whereas the remaining four are chamaephytes (P. aurita, P. hadrosoma, P. lanata, and P. multiflora), which shed their leaves during summer. The herbaceous species are perennial hemicryptophytes.

Because of the differences in life histories, the genus is ideally suited to examine the evolution of insular woodiness. Multiple origins of woodiness in oceanic islands would support the hypothesis that shifts between herbaceous and woody forms can take place easily, thereby reducing the utility of this character for tracing continental ancestors of insular endemics.

We present a molecular phylogeny of Pericallis based on sequences of the internal transcribed spacers (ITS) of nuclear ribosomal DNA to elucidate phylogenetic relationships among species of the genus and to assess the origin and evolution of woodiness under insular conditions. We also test previous suggestions that Pericallis is a biogeographical link between the biotas of Macaronesia and the New World (18).

Materials and Methods

All 15 species of Pericallis were examined, including an unpublished new taxon from the pine forest of southeastern Tenerife (Table 1). Twenty-two accessions of Pericallis were studied with multiple samples for P. appendiculata, P. aurita, and P. tussilaginis. Cineraria, Dorobaea, Packera, and Pseudogynoxys were sampled because results from previous morphological (17), palynological (18), and chloroplast DNA (cpDNA) studies (19) suggested these genera as putative relatives of Pericallis. We included five additional genera of Senecioneae from Africa and the New World. Gynura was selected as the outgroup based on a previous cpDNA restriction site study (20).

Total genomic DNA was isolated by the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide method (21) from fresh or silica-dried leaf material and herbarium specimens. DNA sequences were obtained at the Sequencing Center of the University of Texas by following the methods described previously (22). Both ITS strands were sequenced and aligned by using the program clustalx (23) with the default options for opening and extension of gaps, followed by minor manual corrections. Some sequences from direct PCR products were difficult to read mainly in the regions flanking the ITS and 18S and 26S genes. For these samples, PCR products were cloned by using the TOPO TA Cloning kit (Invitrogen) (see Fig. 1 legend). Aligned sequences are available on request from the corresponding author and they also are deposited in Fairchild Tropical Garden (FTG) and the University of Texas (TEX).

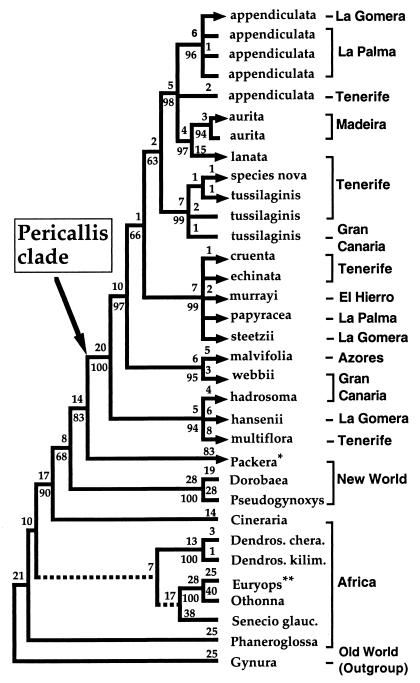

Figure 1.

One of the 214 equally parsimonious ITS trees from unweighted Fitch parsimony analysis (593 steps; consistency index = 0.607, without autapomorphies; retention index = 0.775). The two branches that collapse in the strict consensus tree are indicated by dashed lines. Numbers above and below branches represent number of steps and bootstrap values (>50%), respectively. This tree is identical to the strict consensus trees obtained after transversions are weighted over transitions by factors of 1.3:1, 1.4:1, 1.5:1, and 1.6:1 and also after gaps of the sequence alignment are incorporated as binary characters. Geographic distribution on continental or island areas also is shown. Taxa included in the maximum- likelihood search are identified by arrows. Sequences obtained after cloning of PCR products are marked below with ¶. All voucher specimens are deposited at ORT, except where indicated below. ¶Cineraria alchemilloides: South Africa, Watson and Panero 94-30 (TEX); ¶Dendrosenecio cheranganiensis: Kenya, Knox 3 (MICH); Dendrosenecio kilimanjari subsp. cottonii: Tanzania, Knox 50 (MICH); ¶Dorobaea pimpinellifolia: Nordenstam and Lundin 158 (S); ¶Euryops pectinatus: ex hort., The University of Texas, Panero 98-DNA-1 (TEX); ¶Gynura formosana: Taiwan, Panero, and Hsiao 6457 (TEX); Othonna parviflora: South Africa, Watson and Panero 94–14 (TEX); Packera obovata: Travis Co., Texas: Panero-7386 (TEX); Phaneroglossa bolusii: South Africa, Watson and Panero 94–62 (TEX); Pericallis appendiculata: ¶La Gomera, JFO 98–150 (FTG); La Palma, ASG 97–4, ASG 97–5; ¶Tenerife, JFO 98–3 (FTG); P. aurita: Madeira, ex hort., Botanical Garden of La Orotava material from seed collection of O (1997–530); ¶P. cruenta: Tenerife, JFO 98–60 (FTG); P. echinata: Tenerife, ASG 97–6; P. hadrosoma: Gran Canaria ex hort., Jardín Botánico Viera y Clavijo; ¶P. hansenii: La Gomera, ASG 97–7; ¶P. lanata: Tenerife, ASG 97–8; species nova: JFO 98–152 (FTG); P. malvifolia: Azores, ex hort., Botanical Garden of La Orotava, material from seed collection of Botanical Garden of Faial (1998–10); P. multiflora: Tenerife, ASG 97–9; P. murrayi: El Hierro, ASG 97–10; P. papyracea: La Palma, ASG 97–11; P. steetzii, La Gomera, ASG 97–15; P. tussilaginis, Tenerife, ASG 97–12, ASG 97–13; Gran Canaria, ASG 97–14; P. webbii: Gran Canaria, Panero et al. 7130; ¶Pseudogynoxys chenopodioides, ex hort., from local nursery at Austin, Panero 98-DNA-2 (TEX); Senecio glaucescens, ex hort. from seeds provided by Kirstenbosch Botanical Garden, South Africa. *, Distribution extends into northern Siberia; **, Distribution extends into Arabia and Socotra island.

Fitch parsimony analysis was performed by using version 4.0d64 of paup* (24) with acctran, mulpars, and tbr options. Heuristic searches were conducted by using 100 random addition sequences. Gaps in aligned sequences were coded either as missing or treated as separate binary characters (present or absent). Four weighted parsimony analyses were undertaken after transversions were weighted over transitions by ratios of 1.3:1, 1.4:1, 1.5:1, and 1.6:1 by means of the usertype stepmatrix command. Weights were calculated on the most parsimonious trees with the highest log likelihood value (see below). The chart option of macclade (25) was used to compute these ratios by using two options: (i) counting maximum and minimum number of changes and (ii) counting changes for unambiguous events only. The transition/transversion ratio also was estimated under the describe tree option of paup* by using maximum likelihood with the Hasegawa et al. (26) model of sequence evolution and among-site variation approximating a gamma distribution.

Bootstrap values (27) were calculated by using 100 replicates with the acctran, mulpars, and tbr options and a heuristic search with one random entry of data. The constraint option was used to determine the number of additional steps required to force the monophyly of the six woody species of Pericallis. Evaluation of statistical differences between the constrained and unconstrained trees was conducted with Kishino–Hasegawa test (28) by using the tree score subroutine. The likelihoods of each tree from the constrained and unconstrained analyses were estimated by maximum likelihood by using the same assumptions for computation of transition/transversion ratio. A Kishino–Hasegawa test also was performed for two of the trees with the highest log likelihood (least negative) from the constrained and unconstrained analyses.

Maximum-likelihood trees were estimated for the 15 species of Pericallis and Packera (see arrows in Fig. 1). This analysis was limited to these taxa because of computer memory limitations. Packera was included because parsimony analyses strongly supported it as sister to Pericallis. Likelihood settings were those used for computation of transition/transversion ratio and likelihood of each particular tree (see above). A single heuristic search with one random entry was used for tree searching.

Results and Discussion

Sequence Variation.

Aligned ITS sequences are 507 bp long (267 bp for ITS1 and 240 for ITS2), 203 sites are constant, and 117 of the variable characters are phylogenetically informative. The number of gaps relative to the outgroup Gynura after alignment is 50, and most are 1 or 2 bp long. The largest gap is a 23-bp deletion in Othonna ITS1. This genus has three additional large deletions of 5, 8, and 11 bp in ITS1. Other genera with large deletions in ITS1 include Euryops (19 bp) and Packera (7 bp). Three of the woody species of Pericallis (i.e., P. appendiculata, P. aurita, and P. lanata) have a unique 2-bp insertion in ITS2. The three remaining woody species of Pericallis (i.e., P. hadrosoma, P. hansenii, and P. multiflora) have a 3-bp deletion in ITS2.

Phylogenetic Analyses.

Fitch parsimony yields 214 equally parsimonious trees with 593 steps, a consistency index of 0.607 (excluding autapomorphies), and a retention index of 0.775. The strict consensus tree (Fig. 1) strongly supports Pericallis as a monophyletic group (100% bootstrap) sister to the New World genus Packera (83% bootstrap). The neotropical genera Dorobaea and Pseudogynoxys form a clade sister to the Pericallis–Packera clade (68% bootstrap). Strict consensus trees from weighted parsimony and coding of gaps as binary states have identical topologies and are virtually identical to trees from unweighted parsimony (Fig. 1). The only difference concerns the relationships among the African genera included in the analysis. Most of these genera collapse in a basal polytomy in the strict consensus tree of unweighted parsimony (Fig. 1), whereas they are weakly resolved in the weighted parsimony trees.

Maximum-likelihood analysis of Pericallis and Packera yields 315 trees. These trees have a log likelihood value of −1,688.11. The strict consensus tree has a topology identical to the one from parsimony analysis (trees not shown).

We are using the ITS tree to address the biogeography and evolution of woodiness in Pericallis. It is widely recognized that individual gene trees may not necessarily reflect the species phylogeny (29, 30). We are confident that our ITS tree of Pericallis is an accurate estimate of species relationships because it is largely congruent with an independent phylogeny based on cpDNA restriction site data (S.-J. Park, J.F.-O., A.S.-G., J.L.P., and R.K.J., unpublished data).

A Biogeographical Link Between Macaronesia and the New World.

The origin of Pericallis is controversial primarily because of the paucity of morphological features for identifying continental relatives (16, 17). In addition, Senecioneae are a large tribe (ca. 120 genera and 3,000 species) (16), making it difficult to conduct sufficient sampling of putatively related genera. Previous morphological studies suggested that the African genus Cineraria was the closest continental relative of Pericallis, because both have corolla lobes with a median resin duct, truncate style branches, compressed cypselae, and palmately veined leaves (17). In addition, a cpDNA restriction site study (20) suggested that Roldana, a genus in the subtribe Tussilagininae, restricted to Mexico and Guatemala, was sister to Pericallis. However, DNA from the latter genus used in that study came from cultivated plants (E. Knox, personal communication), and it seems likely that the putative Pericallis was mislabeled Pericalia, a genus that is considered congeneric with Roldana.

The ITS phylogeny indicates a strong sister group relationship (83% bootstrap value) between Pericallis and the New World herbaceous genus Packera (Fig. 1), which has yellow or orange-red flowers. The clade formed by these two genera is also sister to a group of two New World genera (i.e., Dorobaea and Pseudogynoxys), which also have orange-red or yellow flowers; however, this relationship is not as strongly supported (68% bootstrap). These data indicate that Pericallis in the Macaronesian islands underwent two major morphological shifts from its North American relatives. The first involved a shift from yellow orange-red to purplish-white corollas, and the second involved a change in habit from herbaceous to woody.

Palynological studies provide further support for a close relationship between Pericallis and Packera. Both genera share the unusual Helianthoid pollen type, which is known only from three other genera of the Senecioneae: Doronicum, Robinsonecio, and Thelanthophora (18). These three genera are part of the subtribe Tussilagininae, and results from both ITS and cpDNA data suggest that they are distantly related to Pericallis (ref. 19; J. Bain, personal communication). A recent phylogenetic study of the Senecioneae based on cpDNA restriction site data (19) placed Pericallis in an unresolved clade with the New World genera Pseudogynoxys and Dorobaea. This study also showed that Roldana is distantly related to Pericallis, which provides further confirmation that plant material reported as “Pericallis” in Knox and Palmer’s (20) cpDNA study is not from this genus. It is noteworthy that, despite the limited sampling of the Senecioneae, both our ITS and Kadereit and Jeffrey’s (19) cpDNA data support a close phylogenetic relationship between the New World genera Pseudogynoxys and Dorobea and the Macaronesian Pericallis. Unfortunately, Kadereit and Jeffrey (19) did not include Packera in their cpDNA phylogeny, although it was studied by Knox and Palmer (20). The cpDNA tree indicated that Pericallis was distantly related to Cineraria, a genus that is closely associated with Packera in our ITS tree.

There are several examples of biogeographical links between the floras of Macaronesia and the New World. A cpDNA restriction site phylogeny of the Crassulaceae places the Madeiran endemic species of Sedum within a clade of Mexican taxa (31). Pelletiera (Primulaceae) is restricted to Macaronesia and the New World, and the family Cneoraceae is confined to the Canaries, Cuba, and the Western Mediterranean. The Macaronesian endemic genus Bystropogon (Lamiaceae) is considered to be related to the South American genus Minthostachys (32).

A likely explanation for a biogeographical connection between the New World and Macaronesia is long-distance dispersal. It is also possible that the ITS phylogeny may reflect a connection that existed between North America, Eurasia, and Africa during the Tertiary (33). The Bering land bridge (between eastern Asia and western North America) and the North Atlantic land bridge (between northern Europe and northern North America) were present until the early Oligocene (33) and facilitated migration between Eurasia and North America (34). Such connections promoted formation of a “boreotropical flora” that extended into the northern hemisphere. This flora was comprised primarily of broad-leaved evergreen taxa, including many members of the Lauraceae (35). Evergreen rain and laurel forests are considered the most important vegetation types of the Tertiary boreotropical flora of Europe (36). This boreotropical flora was replaced slowly by broad-leaved deciduous taxa as the climate cooled during the Oligocene and Miocene. Eventually, the first Northern Hemisphere glaciation in the Pliocene led to the extinction of numerous taxa in many parts of North America and Eurasia. Several genera survived as relicts in the laurel forests of Macaronesia and in the Mediterranean “Laurocerasus belt” (36). Clethra, Ocotea, and Persea are examples of groups that currently occur in the laurel forest of Macaronesia and mainly in the neotropics but are not present in Europe. They are considered remnants of this boreotropical flora (12). Three of the woody, laurel forest species of Pericallis form one of the two basally divergent clades in the ITS phylogeny (Fig. 2). Conceivably, the continental relatives of Pericallis may have occupied a nearly continuous belt associated with the laurel forest of the Tertiary boreotropical flora.

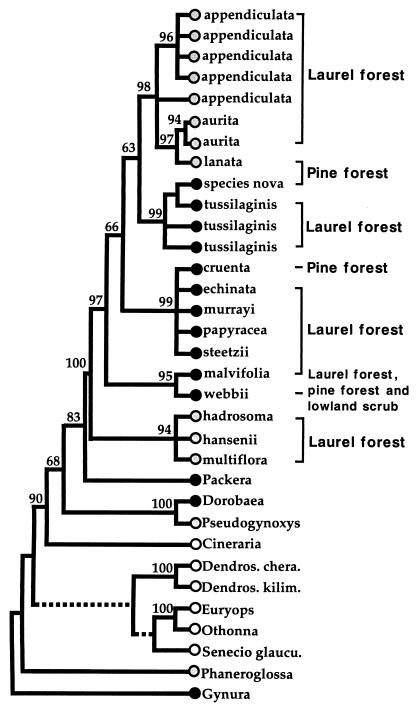

Figure 2.

One of the 214 equally parsimonious ITS trees from unweighted Fitch parsimony analysis (further details on tree topology are shown in Fig. 1). This is the same tree shown in Fig. 1 but indicating the ecological zones and habit of Pericallis and continental species. Solid circles, herbaceous species; shaded circles, woody species; open circles, genera with both woody and herbaceous species. Bootstrap values (>50%) are indicated along each branch.

We believe that Pericallis was not associated with the continental laurel forest of this boreotropical flora for two reasons. First, the oldest fossils of the Asteraceae are from the mid-Oligocene of South America (37). The first pollen evidence of the Senecioneae is from the early Miocene from the South Pacific (38), and both morphological (39) and molecular phylogenies (40) support a recent origin for this tribe. A post-Oligocene origin for the Senecioneae would make it unlikely that the ancestor of Pericallis was part of the Tertiary laurel forest of the boreotropical flora because a temperate, deciduous forest replaced most of the evergreen boreotropical flora by the Miocene (33). Furthermore, biotic migrations between North America and Northern Europe were highly reduced by widening of the North Atlantic (33).

The derived position of Pericallis in the ITS phylogeny also suggests a relatively recent origin for the genus and, therefore, that it evolved in the Macaronesian islands after long-distance dispersal from the New World. Lack of fossil evidence for Pericallis and its continental sister genera and high discrepancies concerning rates of evolution of the ITS sequences (41) do not allow us to establish definitive conclusions concerning times of divergence.

Two Independent Origins of Woodiness in Pericallis.

Trees from all analyses are concordant in showing two clades containing only woody taxa of Pericallis (Fig. 2). The first clade (94% bootstrap support) is basally divergent and includes the three laurel forest species P. hadrosoma, P. hansenii, and P. multiflora. The second woody clade (98% bootstrap support) is in a derived position within Pericallis and includes two species from the laurel forest (i.e., P. appendiculata and P. aurita) and one from the pine forest (i.e., P. lanata). This second lineage is nested within a clade that includes all nine herbaceous species.

Constraining the monophyly of the six woody species yields 72 equally parsimonious trees 12 steps longer than the most parsimonious unconstrained trees. Eleven of these trees have the highest log likelihood value of −3,611.38. Unconstrained analyses yield 35 trees with the highest log likelihood value of −3,569.31. A Kishino–Hasegawa test between two of the most likely trees from the constrained and unconstrained analyses indicates that they are significantly different at the 5% level.

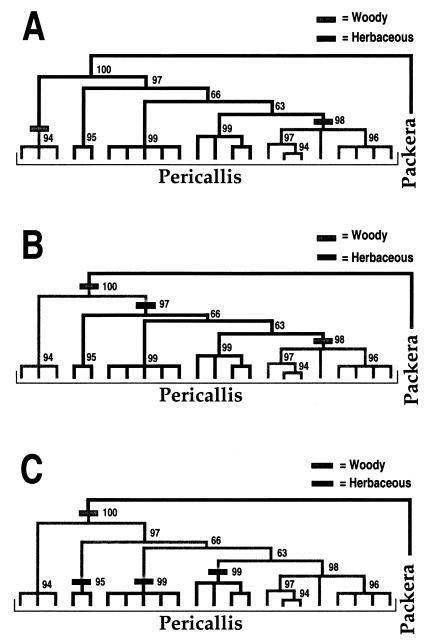

The most parsimonious explanation for the evolution of growth habit in Pericallis is that woodiness arose twice in the islands from an herbaceous ancestor (Fig. 3A). This hypothesis assumes that Pericallis was never present in the continent and that the putative herbaceous ancestor arrived in the islands before diversification of the genus.

Figure 3.

Evolution of woodiness in Pericallis (Fig. 1) assuming that the ancestor of Pericallis was herbaceous (A) or woody (B and C). Numbers of steps of each tree and number of changes to woodiness also indicated. Solid branches indicate a herbaceous condition, and shaded branches indicate the woody habit. Bootstrap values are indicated along each branch.

Two alternative but less parsimonious hypotheses for the evolution of woodiness are illustrated in Fig. 3 B and C. The first requires three steps and involves a shift from herbaceous to woody between the sister group (Packera) and Pericallis, followed by an initial change from woody to herbaceous and then a reversal to woodiness (Fig. 3B). The third hypothesis requires four steps, including a change from herbaceous to woody between the continental ancestor and Pericallis. This hypothesis requires three independent origins of the herbaceous condition (Fig. 3C). We favor the most parsimonious explanation (Fig. 3A).

Previous evolutionary hypotheses suggested that the ancestral habit of Pericallis was a shrub that evolved toward herbaceous forms (17, 42). These hypotheses were not based on a phylogenetic analysis and did not suggest the possibility of multiple origins for woodiness.

What environmental conditions could have led to these major shifts in the life history of Pericallis? All woody species, with the exception of P. lanata, have very restricted ecological preferences and are never found outside of the laurel forest. Three of these species are extremely rare. P. hadrosoma has one population with fewer than 10 plants, and P. multiflora and P. hansenii are known only from scattered populations of a few individuals. Furthermore, the woody laurel forest species are found mainly in the understory and do not occur in open and sunny areas. Thus, it appears that most of the woody species of Pericallis have limited capacity for population growth, reduced competitive ability, and small population size. The only exceptions are the sister species, P. lanata and P. aurita, which are relatively common in southern Tenerife and Madeira, respectively. In contrast, the herbaceous species do not have such narrow ecological preferences. Although they do have an optimal ecological zone, the herbaceous taxa are also commonly found outside these boundaries and have been able to exploit marginal habitats in which the original forest has been cleared for agriculture and urban development. The most extreme case is P. webbii, a very common species from Gran Canaria, which thrives in the lowland scrub and both the laurel and pine forests. All herbaceous species seem to have high colonizing ability, capacity for rapid population growth, large population sizes, and the ability to exploit disturbed habitats.

Taxon cycling and island colonization theories (43, 44) also could provide an ecological explanation for the evolution of woodiness in Pericallis. These theories assume that successful island colonizers are usually weedy species that establish themselves easily on “marginal” and newly opened habitats. The pioneer species can grow fast in habitats that usually are not very crowded. Herbaceous species of Pericallis exhibit some of these features. Therefore, the continental ancestor of Pericallis was likely a herbaceous generalist that could have colonized many of the open or marginal habitats of the islands. Increased specialization and selection in competitive environments with scarce resources may have precipitated a shift toward persistence through woodiness. Such a correlation between evolution of insular arborescence and ecological shifts from open to species-rich habitats has been suggested recently by Givnish (45).

There are at least three other monophyletic groups of Macaronesian endemics with both woody and herbaceous species [i.e., the Aeonium alliance (Crassulaceae), the woody Sonchus alliance, and Echium]. ITS phylogenies of these groups showed that they originated from herbaceous continental species (8, 9, 46). Recent molecular phylogenetic studies (M. E. Mort, personal communication) also suggested multiple origins of woodiness for Macaronesian endemics of the Aeonium alliance. Evolution of habit in Echium and the woody Sonchus alliance is not resolved because of low resolution and support for most clades including Macaronesian taxa (8, 9).

Our demonstration of multiple origins of insular woodiness questions the validity of the assumption that continental ancestors of island endemics were woody. Shifts between the woody and herbaceous habit could take place easily depending on selection patterns, supporting many of the conclusions of Carlquist (1, 13) and recent suggestions by Givnish (45) concerning the evolution of woodiness in island endemics.

Acknowledgments

We thank E. B. Knox and J. W. Kadereit for DNA samples of Dendrosenecio and Dorobaea, respectively. We are grateful to the curators of the seed banks of the Botanic Gardens of Faial (Azores), Oslo, and Tafira Alta (Gran Canaria) for providing germplasm. Our gratitude is also extended to J. Barber, D. Crawford, L. Goertzen, C. Kernan, D. Levin, M. Mort, T. Rawlins, B. Simpson, and two anonymous reviewers for critically reading an earlier version of the manuscript. We also thank D. Swofford for permission to use paup*, S. Simnons for technical assistance, and the Sequencing Facility of the Institute of Cell and Molecular Biology at the University of Texas, Austin. This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation (970614 to R.K.J. and J.F.O.) and the National Geographic Society (6131-98 to R.K.J. and A.S.G.) and start-up funds from the University of Texas to J.L.P.

Abbreviations

- cpDNA

chloroplast DNA

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer of 18S-26S nuclear ribosomal DNA

- FTG

Fairchild Tropical Garden

- TEX

the University of Texas

Footnotes

References

- 1.Carlquist S. Island Biology. New York: Columbia Univ. Press; 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemsley W B. In: Report of the Voyage of H. M. S. Challenger. Botany. Wyville-Thompson C, Murray J, editors. Vol. 1. London: Her Majesty Stationery Office; 1885. pp. 1–299. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldridge A E. In: Plants and Islands. Bramwell D, editor. London: Academic; 1979. pp. 279–291. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wagner W L, Herbst D R, Sohmer S H. Manual of the Flowering Plants of Hawaii. Vol. 1. New York: Columbia Univ. Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stuessy T D, Marticorena C, Rodríguez R-R, Crawford D J, Silva O M. Aliso. 1992;13:297–307. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carlquist S. Bull Torrey Bot Club. 1970;97:353–361. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders R W, Stuessy T F, Marticorena C, Silva O M. Opera Bot. 1987;92:195–215. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Böhle U-R, Hilger H, Martin W F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11740–11745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim S-C, Crawford D J, Francisco-Ortega J, Santos-Guerra A. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7743–7748. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mabberley D J. New Phytol. 1975;74:365–374. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cuatrecasas J. Phytologia. 1976;35:43–61. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bramwell D. In: Taxonomy, Phytogeography and Evolution. Valentine D H, editor. London: Academic; 1972. pp. 141–159. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carlquist S. Phytomorphology. 1962;12:30–45. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saporta G. Ann Sci Nat Ser. 1865;54:5–264. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Depape G. Ann Sci Nat Ser. 1922;104:73–265. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bremer K. Asteraceae: Cladistics and Classification. Portland, OR: Timber; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nordenstam B. Opera Bot. 1978;44:1–84. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bain J F, Tyson B S, Bray D F. Can J Bot. 1996;75:730–735. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kadereit J W, Jeffrey C. In: Compositae: Systematics. Proceedings of the International Compositae Conference. Hind D J N, Beentje H J, editors. Vol. 1. Kew, U.K.: Royal Botanic Gardens; 1996. pp. 349–360. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Knox E B, Palmer J D. Am J Bot. 1995;82:1567–1573. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Doyle J J, Doyle J L. Phytochem Bull. 1987;19:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Francisco-Ortega J, Goertzen L R, Santos-Guerra A, Benabid A, Jansen R K. Syst Bot. 1999;24:249–266. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson J D, Higgins D G, Gibson T J. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swofford D L. paup*: Phylogenetic Analysis Using Parsimony (*and Other Methods) Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1998. , Version 4.0d64. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maddison W P, Maddison D R. macclade, Analysis of Phylogenetic and Character Evolution. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer; 1995. , Version 3.05. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasegawa M, Kishino H, Yano T. J Mol Evol. 1985;21:160–174. doi: 10.1007/BF02101694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Felsenstein J. Evolution. 1985;39:783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kishino H, Hasegawa M. J Mol Evol. 1989;29:170–179. doi: 10.1007/BF02100115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pamilo P, Nei M. Mol Biol Evol. 1988;5:568–583. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Doyle J J. Syst Bot. 1992;17:144–163. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vam Ham R C H J, ’T Hart H. Am J Bot. 1998;85:123–134. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Briquet J. In: Die Natürlichen Pflanzenfamilien. Engler A, Prantl K, editors. Vol. 4. Leipzig, Germany: Verlag von Wilhelm Engelmann; 1897. , Part 3a, pp. 183–380. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tiffney B H. J Arnold Arbor. 1985;66:73–94. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lavin M, Luckow M. Am J Bot. 1993;80:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herendeen P S, Crepet W L, Nixon K C. Plant Syst Evol. 1994;189:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mai D H. Plant Syst Evol. 1989;162:79–91. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Graham A. In: Compositae: Systematics, Proceedings of the International Compositae Conference. Hind D J N, Beentje H J, editors. Vol. 1. Kew, U.K.: Royal Botanic Gardens; 1996. pp. 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bremer K. Cladistics. 1987;3:210–253. doi: 10.1111/j.1096-0031.1987.tb00509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Couper R A. New Zealand Geol Surv Paleontol Bull. 1960;32:1–87. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kim K-J, Jansen R K. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:10379–10383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Baldwin B G, Sanderson M J. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:9402–9406. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.16.9402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Serrada J, Pascual L, Díaz G, Marrero A, Suárez C. Canarias: Enciclopedia de la Naturaleza de España. Vol. 9. Barcelona: Debate & Circulo de Lectores; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacArthur R H, Wilson E O. The Theory of Island Biogeography. New York: Princeton Univ. Press; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vogler A P, Goldstein P Z. In: Molecular Evolution and Adaptive Radiation. Givnish T J, Sytsma K J, editors. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1997. pp. 353–373. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Givnish T J. In: Evolution on Islands. Grant P R, editor. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press; 1998. pp. 281–304. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mort, M. E., Soltis, D. E., Soltis, P. S., Francisco-Ortega, J. & Santos-Guerra, A. (1999) Am. J. Bot., in press. [PubMed]