Abstract

Sequence analysis based on multiple isolates representing essentially all genera and species of the classic family Volvocaeae has clarified their phylogenetic relationships. Cloned internal transcribed spacer sequences (ITS-1 and ITS-2, flanking the 5.8S gene of the nuclear ribosomal gene cistrons) were aligned, guided by ITS transcript secondary structural features, and subjected to parsimony and neighbor joining distance analysis. Results confirm the notion of a single common ancestor, and Chlamydomonas reinharditii alone among all sequenced green unicells is most similar. Interbreeding isolates were nearest neighbors on the evolutionary tree in all cases. Some taxa, at whatever level, prove to be clades by sequence comparisons, but others provide striking exceptions. The morphological species Pandorina morum, known to be widespread and diverse in mating pairs, was found to encompass all of the isolates of the four species of Volvulina. Platydorina appears to have originated early and not to fall within the genus Eudorina, with which it can sometimes be confused by morphology. The four species of Pleodorina appear variously associated with Eudorina examples. Although the species of Volvox are each clades, the genus Volvox is not. The conclusions confirm and extend prior, more limited, studies on nuclear SSU and LSU rDNA genes and plastid-encoded rbcL and atpB. The phylogenetic tree suggests which classical taxonomic characters are most misleading and provides a framework for molecular studies of the cell cycle-related and other alterations that have engendered diversity in both vegetative and sexual colony patterns in this classical family.

The Volvocaceae (classically including Astrephomene and all species of Gonium) are a coherent family of 40 species of colonial green algae common in freshwater habitats the world over. The genus Volvox, discovered by van Leeuwenhoek 300 years ago, has particularly intrigued biologists because of its peculiar manner of colony formation, involving an inversion superficially similar to the gastrulation of typical animal embryos. Volvox and the other members of the Volvocaceae also represent a novel origin of multicellularity, complete with specialized cell types in an organized, determinate body plan. The family provides an ideal grouping to test molecular methods of phylogenetic assessment. My purpose here is threefold: (i) to derive the evolutionary history of the family from DNA sequence comparisons, using representatives of all of the taxa available, including multiple isolates; (ii) to compare these results with those of previous DNA sequence studies; and (iii) to assess the position of the major facets of development on the phylogenetic tree derived from sequence comparisons to predict evolutionary parallisms that can now be tested utilizing molecular techniques.

I sequenced the internal transcribed spacer (ITS) sequence ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions of the nuclear rRNA cistron because previous results with Volvocales have demonstrated that they are >10-fold more variable than rRNA genes yet are homogenized by unknown mechanisms with very high frequency, such that they behave essentially as a single locus despite the presence of >100 tandem copies in a genome (1). Furthermore, knowledge of the ITS RNA transcript secondary structure (2, 3) is valuable in guiding alignment among more distantly related taxa. The results of phylogenetic inference methods using ITS support most of those obtained previously with data for other DNA regions in identifying major clades and their relationships. However, the expanded taxonomic coverage revealed additional and unexpected relationships.

Materials and Methods

The algal isolates that form the basis of this study are listed below and Volvocacean taxonomy is summarized in Table 1. The taxon names are those found in the culture collection listings. Included is the Culture Collection designation [University of Texas, National Institute for Environmental Studies (Japan), A.W.C. or R. C. Starr collection], an abbreviated name, and the GenBank accession number. Where the mating affinity of an isolate is known, its group is included as a Roman numeral in the abbreviated name. Asterisks designate sequences used here only in the Volvox tree. Altogether, >300 isolates representing 40 species of the 9 genera of Volvocaceae, including multiple representatives of geographically widespread taxa, have been sequenced, ignoring duplicate isolates and multiple clonings. Sequences of >50 taxonomically related unicellular organisms are available for comparison (4).

Table 1.

Taxonomy of Volvocaceae

| p | Taxon | Spp. | sp. | n | Σ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.096 | Astrephomene | 2 | − | 64 | 10 |

| 0.079 | Gonium | ||||

| 0.009 | 4-celled Gonium (Tetrabaeniaceae) | 2 | − | 4 | 7 |

| 0.035 | >4-cell Gonium | 5 | − | 16–32 | 37 |

| 0.222 | Pandorina + Volvulina clade | ||||

| 0.219 | Pandorina morum/smithii | 2 | − | 16 | 66 |

| 0.131 | Volvulina | 4 | − | 16–32 | 9 |

| 0.070 | Yamagishiella = P. or E. charkowiensis = P. unicocca | 1 | − | 32 | 13 |

| 0.158 | Eudorina + E. illinoisensis = 4 Pleodorina illinoisensis | 4 | + | 32–64 | 39 |

| 0.086 | Platydorina clade | 2 | + | 32 | 4 |

| 0.129 | Pleodorina californica/japonica | 2 | + | 128 | 4 |

| 0.025 | Pleodorina indica | 2 | + | 64 | 2 |

| 0.354 | Volvox | ||||

| 0.087 | Volvox Printz | 4 | + | >400 | 4 |

| 0.295 | Merrilosphaera Shaw | 9 | + | >400 | 17 |

| 0.001 | Janetosphaera Shaw | 2 | + | >400 | 5 |

| 0.025 | Copelandosphaera Shaw | 1 | + | >400 | 3 |

p, maximum level of pairwise distance encompassed by the taxonomic category; Spp., number of species utilized; sp., make sperm packets; n, maximum number cells per vegetative colony; Σ, number of sequences utilized (see text).

Chlamydomonas reinhardtii CCC621 (Crein) U66954; Paulschultzia pseudovolvox UTEX 167 (Psps) AF182428; Astrephomene gubernaculifera UTEX1393 (Agub) AF054422; Astrephomene perforata UTEX2475 (Aper) U66939; Gonium sacculiferum UTEX822 (Gsac) U66972; Gonium sociale UTEX14 (Gsoc) U66976; Gonium multicoccum UTEX783 (Gmul) U66967; Gonium octonarium UTEX842(Goct) U66968; Gonium pectorale UTEX2570 (GpBC) AF054425; G. pectorale AWC-Af2–3 (GpAf) AF054431l; G. pectorale AWC-Laos(GpL) AF182429; Gonium quadratum AWC-Cal3–3 (Gq3) AF182430; G. quadratum AWC-Cat (GqCAT) AF182431; Gonium viridastellatum UTEX2520 (Gvir) AF182432; Pandorina smithii ASW05154 (Psmit) AF098192; Pandorina morum UTEX853 (PmI) U23530; P. morum UTEX1734 (PmII) U66988; P.morum UTEX865 (PmIII) U23533; P. morum UTEX864 (PmIV) AF098185; P. morum AWC-P57 (PmV) AF098190; P. morum UTEX857 (PmVII) AF098193; P. morum UTEX867 (PmVIII) AF182434; P. morum UTEX871 (Pmhom) U67020; P. morum UTEX881 (PmXIV) AF098197; P. morum UTEX882 (PmXV) U66992l; P. morum UTEX1732 (PmXVIII) U66987; P. morum AWC-Poona (PmPXX) AF182433; P. morum UTEX2331 (PmXX) U66989; Volvulina boldii UTEX1761 (Vbol) U67030; Volvulina compacta NIES582 (Vcom) U67031; Volvulina pringsheimii UTEX1020 (Vpri) U67032; Volvulina steinii UTEX1525 (Vstein) U67033; Volvulina sp. AWC-Kris (Vsp) U67036; Pandorina charkowiensis AWC-Butler (YB) U66984; Eudorina/Pandorina sp. ASW05149 (Yasw) AF098179; Eudorina? ASW05156 (E?) AF098175; Eudorina sp. AWC-China#5 (Esp) AF182435; Eudorina elegans UTEX240 (Ee40) AF098169; E. elegans UTEX1201 (Ee1II) U66958; E. elegans UTEX1209 (EeII9) AF182436; E. elegans UTEX1194 (EeIII) AF182437; E. elegans UTEX1192 (EeIV) AF098173; Eudorina cylindrica UTEX1197 (EcyIV) U66957; Eudorina unicocca f. peripheralis UTEX1221 (EuniV) U66965; Eudorina illinoisensis ASW05144 (Eil4) AF098174; E. illinoisensis UTEX2182 (Eil2) AF182438; Platydorina caudata UTEX1658 (Platy) U67000; Eudorina cylindrica? ASW05157 (Ecy7) AF182439; Pleodorina californica UTEX198 (Plcal8) U67001; P. californica* UTEX809 (Plcal9) U67003; Pleodorina japonica UTEX2523 (Pljap) U67005; Pleodorina indica ASW05153 (Plind3) AF098176; P. indica UTEX1991 (Plind1) U67004; VolvoxVolvox barberi* UTEX804 (Vxbarb) U67013; Volvox capensis* UTEX2712 (Vxcape) U67014; Volvox globator UTEX955 (Vxglob) U67022; Volvox rousselettii* UTEX1862 (Vxrous) U67025; Merrilosphaera Volvox gigas UTEX1895 (Vxgig) U67021; Volvox powersii UTEX1864 (Vxpow) U67024; Volvox africanus* (UTEX1889) (Vxaf9) U67008; V. africanus UTEX1890 (Vxaf0) U67009; V. africanus* UTEX1891 (Vxaf1) U67010; V. africanus* UTEX1892 (Vxaf2) U67011; V. africanus* UTEX1893 (Vxaf3) AF182440; Volvox carteri f.nagariensis UTEX1885 (Vxcn5-I) U67017; V.carteri f. nagariensis* Starr-Poona (VxcnP-I) U67019; V. carteri f. kawasakiensis* NIES580 (Vxck-I) U67018; V. carteri f.weismannia* UTEX1874 (Vxcw4) U67015; V. carteri f. weismannia* UTEX1876 (Vxcw6) U67016; Volvox obversus UTEX1865 (Vxobv) U67023; Volvox spermatosphaera UTEX2273 (Vxsp3) U67026; V. spermatosphaera* STARR-62 (Vxsp2) U67027; Volvox tertius* UTEX132 (Vxtert) U67029; Janetosphaera Volvox aureus UTEX1899 (Vxaur) U67012; Volvox pocockiae UTEX1872 (Vxpoc) AF182441; Copelandosphaera Volvox dissipatrix UTEX1871 (Vxdis1) U67020; V. dissipatrix* UTEX2184 (Vxdis4) AF182442.

The region sequenced is in the nuclear ribosomal repeats, encompassing the two internal transcribed spacers (ITS-1 and ITS-2) flanking the 5.8S gene. Details of the methodology have been described previously (5). In brief, the entire ITS-1–5.8S-ITS-2 region was amplified, cloned, and sequenced manually in both directions. macvector (Kodak) and assemblylign software (International Biotechnologies) were used to organize and align sequences, guided by the known ITS transcript secondary structure (2, 3).

To facilitate analysis, phylogenetically related subgroups of the total sequences available were first analyzed by both parsimony and distance methods using paup* 4.0 versions (Sinauer Associates, Sunderland, MA). Subsequently, 52 sequences were selected to use in the “CAGPEV” alignment, which covers the entire family plus two unicellular organisms. The taxa were selected on three grounds: to represent the extent of variation found within any broad genus or species clade (e.g.,13 Pandorina morum sequences), to include sequences of essentially all rare organisms (e.g., Pleodorina japonica UTEX2523 plus Pleodorina californica UTEX198, one of three essentially identical P. californica isolates), and to utilize both a closer and a more distant unicellular relative as out groups (C. reinhardtii, the most similar known unicell, and Paulschulzia pseudovolvox, a green unicell bearing pseudocilia, with cells aggregated by extracellular matrix layers similar to those of Volvocaceae). Either the CAGPEV alignment or one of the subgroup alignments included all available UTEX cultures that were previously utilized for sequence analysis of other DNA regions.

Sequence alignments were analyzed by both maximum parsimony (heuristic, TBR) and distance matrix (Kimura two-parameter with neighbor joining) methods, using all nucleotide positions of ITS-1 (282 parsimony informative positions) and ITS-2 (227 parsimony informative positions), or each separately. All positions were weighted equally, and gaps were treated as missing data. Repeatability of tree conformation was assessed by running 100 bootstrap replications several times. For a few smaller alignments, use was made of the Maximum Likelihood algorithm of paup* in a heuristic search. In addition, most parsimonious trees were sought by first determining an appropriate upper boundary of step number and then setting the heuristic program to save 200 trees below this bound.

Results

Characteristics of the ITS Regions.

The right column of Table 1 indicates the total number (220) of algal clones providing sequences utilized in one or more alignments in this study. For example, in the “Platydorina clade,” ASW05157 and UTEX1658 appear here, but UTEX851 and UTEX1660 (identical in sequence to UTEX1658) were used in additional alignments. Overall, the results of sequencing ITS regions are very similar to earlier, more limited studies in having a GC content near 50%. All sequences are fundamentally similar in structure also, with a few exceptions (see below). ITS-1 averages ≈260 nucleotide pairs in length, with a maximum of 523 bp found in V. africanus UTEX1889. ITS-2 averages ≈235 nucleotide pairs with a maximum of 511 found in P. californica UTEX198. The longer examples reflect primarily insertions at the ends of hairpin loops. The 5.8S region was nearly identical in all sequences, and the few variant sites yielded no phylogenetically useful information.

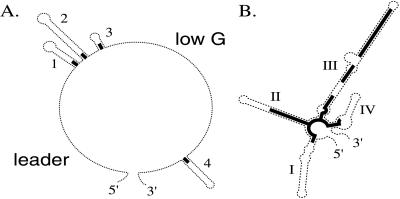

The putative secondary structures of the ITS-1 and ITS-2 transcripts, described in refs. 2 and 3, have a number of standard features (Fig. 1 A and B). For ITS-2, these are present in all of the taxa. For ITS-1, there are some exceptions to the standard 5′ leader, three hairpins, low-G single-stranded region, and a fourth hairpin near the 3′ end. The first exceptional form appears twice in the family, in two isolates of P. morum that clade together (7), and in the Volvox subfamily of Volvox. These lack the first three hairpins (1, 2, and 3), having only a 6- to 8-base transition from the leader to the typical beginning of the low-G single-stranded region. A variant on this is found in P. californica and P. japonica and also in all isolates of V. dissipatrix, where almost the entire 5′ region of ITS-1, proximal to the low-G single-stranded region, is involved in a single long hairpin loop, and even the leader region is unusual.

Figure 1.

Diagram of the common elements of ITS-1 (A) and ITS-2 (B) transcript secondary structure. Heavy lines indicate regions of relative evolutionary conservation.

The remaining exceptions also involve ITS 1 and Volvox species. The V. spermatosphaera and V. tertius isolates and all of the V. africanus sequences lack the recognizable 5′ leader and have instead an additional loop, resulting in four loops before the low-G single-stranded region. The sequence and conformation of these unusual forms is extremely consistent within each clade but unrecognizably different between clades. Finally, the 5′ half of the V. pocockiae ITS-1 sequence is unique. Secondary structure models of its ITS-1 suggest four hairpin loops before the low G single stranded region, but there is only one isolate available so that the secondary structure remains tentative. As a consequence of this variation, alignments including such taxa were appropriately trimmed of their nonhomologous regions in the 5′ portion of their ITS-1 regions (which appeared to make no difference to the outcome versus untrimmed) and/or analysis was confined to ITS-2 sites in which all examples displayed the standard conformation.

Sequence Comparisons.

The first column of Table 1 provides a rapid assessment of the level of diversity within various groups by showing the results of pairwise distance comparisons found for the ITS-2 positions known to be relatively conserved for secondary structure, positions that are present in all of the sequences. The genus Volvox shows the greatest sequence diversity, most of which lies in the subgenus Merrillosphaeraceae. The two most different sequences found in the entire family are V. africanus versus V. dissipatrix (0.354). None of the examples of high similarity result from sequencing isolates of a confined geographic area. The value of 0.025 for the Copelandosphaera represents three isolates of V. dissipatrix from India and Australia; the value of 0.001 for the Janetosphaera represents V. aureus from four sites in North and South America but omits V. pocockiae (see below).

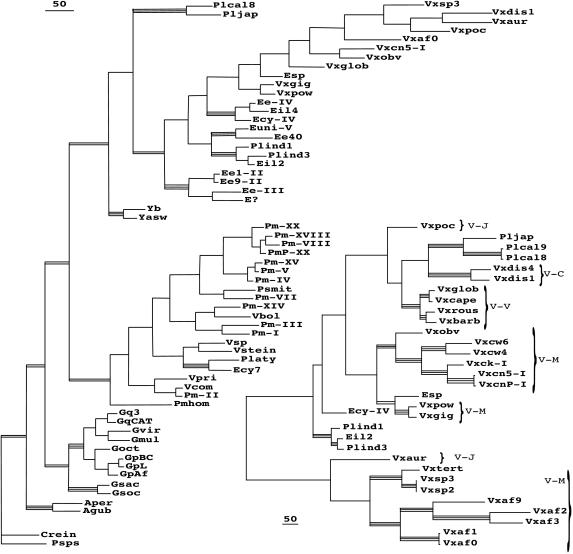

Fig. 2 Left illustrates one of four most parsimonious trees found using the CAGPEV alignment and all positions in the ITS-1 and ITS-2, overlain by indication of the relative bootstrap support levels (>50% or >75%) for the clades. None of the double- or triple-bar clades ever showed significant bootstrap for affinity to any other group, with one exception discussed below, the placement of Platydorina. I have ignored here the more terminal subclades of Astrephomene, Gonium, Pandorina-Volvulina, and the Eudorina subgroups, that are treated elsewhere (refs. 1, 3, 6, and 7; A.W.C., unpublished work).

Figure 2.

Cladograms, with bootstrap support from additional analyses indicated. Those (triple bars) supported above the 75% level in at least three of the standard four types of analyses, parsimony of all positions and of ITS-2 only, and distance analyses of all positions or ITS-2 only; and those (double bars) supported above the 50% level in the same analyses. (Bar = 50 changes.) (Left) One of the four most parsimonious trees found by heuristic search using ITS-1 and 2 of the CAGPEV alignment. (Right) Maximum likelihood tree found by heuristic search using ITS-2 positions of the supplemented all-Volvox alignment. Brackets indicate subgeneric groups of Volvox.

Alignments limited to the Yamagishiella-Eudorina- Platydorina-Pleodorina-Volvox isolates, but including more representatives from the sequence collection, were examined to clarify clade association (data not shown). Analyses revealed the same clades as seen in Fig. 2A. The independence of the P. californica clade and the Yamagishiella clade, branching basally, was maintained. Two Volvox isolates (1895 and 1864) were consistently associated with the Eudorina sp. isolate, although with <75% bootstrap values. The positioning of the subgenus Volvox representatives separate from the remaining Volvox representatives, and their monophyly, was consistently supported.

The clade of Platydorina/Eudorina cylindrica 05157 was unique among all of the data set, a classic “long-branch” problem, because its placement varied with the selection of taxa included in the alignment. In Fig. 2, this small clade appears within the P. morum/Volvulina clade, but this happens only with parsimony analyses and only when all of the CAGPEV taxa are included. Even then, the position within the P. morum/Volvulina clade differs if ITS-1+ ITS-2, ITS-2 alone, or even conserved postions alone are used. When P. morum/Volvulina sequences are omitted from an alignment, all analyses place the Platydorina clade as a separate clade branching basally to Yamagishiella-Eudorina-Pleodorina-Volvox or in a basal position on a branch bearing the Yamagishiella clade. Platydorina sperm packets are unique in completing the inversion process (15); sperm packets of 05157 have not been observed.

Finally, to assess clades in the Volvox region of the tree, a further taxonomically limited alignment was made and analyzed (Fig. 2). Included are all of the Volvox isolates available plus representatives of the four species of Pleodorina and the three Eudorina sequences showing affinity. In addition to the clades found in Fig. 2A, new clades encompassing the added Volvox sequences appear, well supported by parsimony and distance bootstrap values. V. pocockiae displays no affinity to any other Volvox with >50% bootstrap value; nor does V. aureus. Individual shortest trees found by parsimony utilizing this alignment fail to agree on any one branching order.

Fig. 2 Right is actually a Maximum Likelihood tree obtained by heuristic search using ITS-2. It was chosen to present for two reasons: it shows much more detailed structure than bootstrap trees obtained from parsimony or distance methods that collapse branches to show only the well supported clades, but, more importantly, ML analysis of either the ITS-2 alone or the ITS-2 plus ITS-1 gives the same clades and branching order with only two minor differences; with the additional ITS-1 positions, the V. aureus clade switches positions with the V. spermatosphaera clade, and Ecy-IV switches places with the Pleodorina indica/japonica clade. The association of Ecy-IV with the Pleodorina indica/japonica clade is supported at the 51% bootstrap level by distance assessments. Interestingly, the tree of Fig. 2B associates the taxa with similar disruptions of the 5′ regions of ITS-1, Pleodorina californica/japonica with V. dissipatrix, and V. africanus with V. spermatosphaera/tertius. Perhaps some major genomic disruption event occurred in a common ancestor.

Discussion

The ITS regions share certain advantages with rDNA genes for phylogenetic comparisons, among which are their universal presence in eukaryotes and the availability of suitable primers. Volvocacean ITS regions have already been found useful down to the subspecies level, where their resolution agrees totally with the pattern of sexual compatibilities of the groups studied (1). Furthermore, there is remarkable agreement between ITS-1 and ITS-2 regions in their support of clades and branching patterns. Altogether, the ITS provides more phylogenetically useful positions than any of the rSSU-rLSU, single genes, or introns used so far to assess the family.

Significance of ITS Sequence Comparisons.

There has been a series of previous efforts to resolve the phylogeny of the Volvocaceae. These include a cladistic analysis of morphological data by Nozaki (8) and sequence comparisons of variable regions of nuclear ribosomal genes (rSSU and rLSU) (9, 10), of gene introns (1, 11), and of the plastid-encoded rbcL and atpB genes (summarized in ref. 12). The results are bewildering and inconsistent, probably for several reasons. One is the use of UTEX-12 as Eudorina in rSSU-rLSU analysis; this organism is clearly a Yamagishiella from ITS sequences (6, 7). Another may be the paucity of taxa, particularly in earlier studies. As an example, the envelopment of Volvulina species into the P. morum clade shown in Fig. 2A becomes obvious only when the appropriate P. morum representatives are included.

The collapse of all but the branches showing >50% bootstrap support in trees of Fig. 2 plus inclusion of the Platydorina clade at the same level as the Yamagishiella clade, would result in a family tree almost identical to the consensus tree presented by Nozaki et al. for rbcL + atpB sequence data (12). All of the clades present in the Nozaki consensus tree are also found in Fig. 2 although the branching order of clades differs in three particulars. In the Nozaki et al. consensus tree, the subgenus Volvox clade branches before all Eudorina-Pleodorina-other Volvox taxa; and in this latter group, the Pleodorina californica/japonica clade is only one of the eight clades radiating together subsequent to the Eudorina mating group I/II/III clade. The third difference is that the Gonium species remain divided into two separate clades, the four-cell Goniums and those species with more than four cells. None of these differences in branching structure finds any significant contradiction in the ITS analysis. The Nozaki consensus tree has only V. carteri representing Merillosphaera.

Several new aspects of the family tree appear from ITS analyses of multiple sequences. Prominent among these is that the isolates of all four Volvulina species included here display affinities within the single large Pandorina morum clade, albeit in different subsections. All previous sequence data associated Volvulina isolates with Pandorina as nearest neighbor, but none of these studies included more than two Pandorina sequences, so the interrelationship found here was not revealed.

A second new finding is the number and position of subclades encompassed by the genus Volvox, each well supported. The Volvox subgenus forms a distinctive clade branching among the Eudorina subclades, just as reported from rbcL and atpB studies using one or several representatives of this group (12). Organisms of the subgenera Copelandosphaera and Janetosphaera each form unique clades, in agreement with prior analyses, although Volvox pocockiae remains the taxonomic problem recognized by Starr (13). He assigned it to Janetosphaera because of its vegetative colony cell appearance, but he thought it most like V. spermatosphaera (Merrilosphaera) in its forming dwarf male colonies at sexual reproduction. By sequence it shows no strong affinity to any other Volvox clade in either parsimony or distance analyses, perhaps behaving like an intermediate. V. pocockiae has an anomalous ITS-1 sequence, and, like all of the other nonsubgenus Volvox species, it has a chromosome number >12 (14). No sequence data from other loci are available for V. pocockiae. The Merrilosphaera form four subclades, the V. carteri/obversus group, the V. africanus group, the V. spermatosphaera/tertius group, and the V. powersii/gigas subclade associated with Eudorina sp. Ribosomal gene sequences (10) also detected an association of V. powersii with a major subgrouping of Eudorina and Pleodorina. The data strongly reinforce the idea that the genus Volvox is paraphyletic, a grouping based on similar morphology rather than a single unique common ancestor.

Four general lessons emerge. The first is that where there is any significant sequence or morphology diversity in a clade, sequencing of additional isolates is useful. Here it has revealed the apparent synonomy of Pandorina morum and the Volvulina species, and the dispersion of Volvox species. The second is that, at least with ITS, there appears to be no preferred phylogenetic inference method. All agree on well supported clades, and all fail to support strongly any further resolution. Third, ITS provides information at both the basal and more terminal levels comparable with that from other loci. The final lesson concerns morphological attributes long used for taxonomy.

Parallels with Classical Taxonomy.

Among the traditional characters of morphology used in taxonomy, it is clear that the extent, placement, and degree of organization of the extracellular matrix can be taxonomically misleading. This single characteristic, of which the molecular and developmental aspects are very poorly understood, explains the taxonomic subdivision of Volvulina species from Pandorina morum and the mismatch of Eudorina species with their clades determined by sequencing and mating affinity. Another example is the newly discovered association of taxa with Eudorina-like morphology but sequence affinity to Platydorina in one case and to Pleodorina indica in another. Even more misleading have been some isolates of Yamagishiella (6, 7) initially labeled Eudorina elegans or Pandorina morum. Clearly, the earlier or more delayed production of extracellular matrix is a relatively labile character evolutionarily.

From the morphological point of view, Platydorina would be expected to join the Eudorina clade because it appears to differ only in forming a secondarily flattened colony rather than the sphere typical of Eudorina. Furthermore, Harris (15) reported isolating a “poor intercalation” mutant consistently producing spherical colonies, a character segregating as a single Mendelian locus. Note that ASW05157, identified as a Eudorina cylindrica, consistently clades with the Platydorina isolates. No variant alignment or analysis method gave any hint of placing Platydorina, or even ASW05157, within the greater Eudorina-Pleodorina group. Sequence data from rRNA gene sequences leave Platydorina on a branch with Volvulina and Pandorina (10); however, rbcL and atpB consensus trees branch Platydorina from the same node as Yamagishiella (12). The unique sperm packets of Platydorina may be significant.

Parallels with Mating Groups.

In general, nutritional characteristics and chromosome numbers (14) show little overall correlation with family structure. The Volvox subgenus of Volvox is the exception, with their uniform chromosome number of five and anomalous ITS-1. Interbreeding potential, however, is perfectly correlated with the detailed branching pattern. Organisms capable of interbreeding are always nearest neighbors on the phylogenetic tree in already published sequence comparisons for Gonium (1), Pandorina (7), and Eudorina (6), and illustrated for Volvox carteri in Fig. 2B. The two most similar representatives, by ITS sequence, of V. carteri f. nagariensis are 1885 and Poona, and these can interbreed and yield at least some viable zygote products (16). The female culture of V. carteri f. kawasaki can be manipulated to form zygotes with the mate of 1885, but the rare zygote products die (17). Comparison of intron sequences of the same V. carteri isolates (11) gave results identical to those in Fig. 2B. This clarification of relationships should prove useful in choosing appropriate organisms to use for reconstructing the evolution of genes controlling development.

Developmental Changes in the Family Evolution.

Construction of a phylogenetic tree by sequence analysis should permit one to make testable predictions concerning the major developmental switches occurring in the family, where in development they operate, and whether they have evolved more than once. Some of these suggestions arise from comparative biology of the natural forms, and others from the extensive developmental studies initiated with the V. carteri f. nagariensis HK9 and HK10 (Japan) isolates by Starr (18). Many traits that appear to be linked in wild types can be genetically uncoupled in mutants, and vice versa; for example, a gene affecting vegetative colony cell arrangement, when mutated, affects cell arrangement in the sexual colony. For a more thorough discussion of V. carteri mutants and their properties, see Kirk (10).

The basic features of the Chlamydomonas cell appear to be largely unchanged in the typical cell of a colony, but all members of the colonial Volvocaceae share two exceptions. The first is necessary for colony formation and appears to be fundamentally a delay in the completion of cytokinesis during colony ontogeny until the precise cell positioning is stabilized by deposition of extracellular investments. Several mutants of V. carteri are known, behaving as single locus Mendelian mutations, where colonies fall apart into single cells during development (10).

The second cellular change is essential to effective colony motion and involves a coordinated rotation of the two basal bodies of a cell during colony development that leads to flagellar motion in parallel rather than performing the breast stroke characteristic of unicells (19). This makes the effective flagellar stroke from anterior to posterior, with respect to the colony axis, a change necessary to propel the colony, rather than the individual cell, forward. Although this alteration occurs in cells of a colony shortly after cell division, it is suppressed in the central cells of the Gonium plate-like colony (19). Also, it probably does not occur in formation of unicellular stages of the life cycle (e.g., zygote products), and must be easily reversible, for Pandorina gametes once released from their colony are fully phototactic.

The next major alteration in the family developmental plan concerns the peculiar inversion process in embryonic development and may have arisen only once, subsequent to the appearance of Astrephomene. Alternatively, because the trait is not diagnosable from Chlamydomonas, Astrephomene may represent a reversion from an ancestral state. Pocock (20) created the family Astrephomeniaceae in recognition of the fact that Astrephomene colonies do not undergo inversion in during development. Starr suggested this may be the consequence of a facet of the second mitotic division in which the four products appear fully separated by cell membranes in Astrephomene whereas the second cytokinesis is clearly incomplete in all of the remaining members of the Volvocaceae, leaving a major cytoplasmic bridge between the newly formed daughter cells [see Starr (21), Fig. 51]. This binds them in such a way that their apices, and those of subsequently engendered cells, initially lie toward the interior of the colony, where flagella would be ineffective. The subsequent inversion process results in flagellated apices on the external surface of the colony. The inversion process is only partial in Gonium and also in sperm packet formation; in both situations, the young colony opens into a slightly inverted plate. A sizeable number of V. carteri inversion mutants have been described, probably representing alteration at a number of different loci involved in this complex process (10).

A striking number of changes evident in the family tree involve altered interactions with cell cycle checkpoints. (i) A family theme is the increasing cell number per colony up to the >10,000 cells in some Volvox species. Just as in Chlamydomonas, the multiple daughter cells are produced in Volvocaceae by “cleavage,” a rapid succession of mitoses subdividing an enlarged mother cell into 2n daughter cells. Exceptions among Volvocaceae are found only in three of the four Volvox subgenera [Volvox, Copelandosphaera, and Janetosphaera (V. aureus but not V. pocockiae)]; in the formation of vegetative colonies, these Volvox species merely alternate cell growth and division into two until the final cell number is reached (14), but, interestingly, they utilize cleavage to form sperm packets. The available phylogenetic analyses suggest, but not strongly, that this alteration in mitotic pattern has happened more than once, perhaps several times. Interestingly, no mutants are known, either in V. carteri or other members of the Volvocaceae. (ii) How cells count is a universally perplexing basic problem of eukaryote biology, particularly apparent in the Volvocaceae. Major clades typically show an invariant upper limit to the number of cells in a colony, no matter what the nutritional conditions (e.g., 4-cell Gonium, G. octonarium with a maximum of 8, Pandorina morum with a maximum of 16). A cell cycle control point must be involved here, halting cleavage in response to some internal measure. (iii) Cell number also appears to dictate the hallmark of the family, two different cell types in the colony. It is expressed in species with 32 or more cells per colony. The second cell type, somatic cells that never divide, is found at the anterior end of colonies except, appropriately in view of the lack of inversion, at the posterior in Astrephomene colonies. (iv) The production of sperm packets, a major taxonomic character distinguishing isogamous from anisogamous/oogamous forms, appears fundamentally to be just a precocious onset of cleavage limited to the development of male gametes. Because the basal branching order of Yamagishiella (isogamous) versus all of the sperm packet producing groups is uncertain, sperm packet production may have evolved only once in the family. No mutant for this character is known, but if such were found, for example, in a Eudorina-like form, it would be classified as a Yamagishiella. From this point of view, the sequence uniformity of the Yamagishiella clade (15 isolates from three continents) is particularly interesting—none is Eudorina-like by sequence. The developmental changes necessary to produce, or to lose, production of sperm packets may be more complex developmentally than appear at first sight.

Finally, there is the rich panoply of forms of sexual reproduction found in the family that suggest two intriguing areas for molecular studies. All of these organisms are haplonts, with the zygote as the only diploid cell. Most isolates of volvocacean algae have genetic control of sexuality exactly like Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, where zygotes are formed only when cells of two genetically different clones, representing plus and minus mating types, are mixed. However, all of the major clades have at least one known example of a homothallic isolate, one capable of sexual reproduction within a genetic clone. Is the same genetic control system common to all of these examples? And in homothallic clones, what kind of epigenetic control dictates the various types of sexual colonies found in different isolates, pure female, pure male, or production of both gamete types within one colony? The suppression of gamete production in either or both sexes must have altered repeatedly in various lines of evolution, perhaps utilizing different pathways of control. With the genetic dissection of the mating type locus in C. reinhardtii (22), and the prospect of the sequencing of the C. reinhardtii genome, studies of the volvocacean algae may be able to utilize information from this close unicellular relative. Molecular tools and methods for manipulation are already available (10).

Sequence analyses confirm the monophyly of the family Volvocaceae. Only the CAGPEV ITS-2 parsimony tree failed to separate the entire family from the two unicells above the 50% bootstrap level, but the other analyses give bootstrap values >80%, as do subgroup analyses (data not shown). In fact, comparisons of all volvocacean ITS sequences with available ITS sequences of 40 unicellular green flagellates (refs. 2, 3, and 4; data not shown) continue to support the idea that the family has the unicell C. reinhardtii as the extant relative showing greatest similarity. Although there is no accepted fossil record available for these organisms, it has been suggested (11) from comparisons of rRNA genes and of actin gene sequences of V. carteri and C. reinhardtii that these organisms have diverged from a common ancestor no more than 75 million years ago, and perhaps as recently as 50 million years ago. There may have been a near-simultaneous blossoming of the family into many forms in the early Cenozoic, and today we see the more vigorous or lucky remnants. More recently, Liss et al. (11) have combined intron sequence comparison with their previous estimates, assuming a constant substitution rate, to estimate divergence times in the Volvox clades. They suggest, for example, that V. carteri f. kawasaki diverged from the V. carteri f. nagariensis line ≈1.2 million years ago.

Further resolution of basal branching patterns is unlikely to come from additional sequence comparisons of loci typically used for this purpose. As with the eukaryote “crown,” some other DNA structural characteristic may provide the key, but the only example so far (23) is not helpful. A group 1A intron in rbcL is shared by G. multicoccum and Pleodorina californica but not by 20 other Volvocaceae examined. The simultaneity of divergence in ancient times may preclude reconstruction in detail. On the other hand, discovery and comparison of the genes responsible for the major facets of development in the family may provide the answer.

Acknowledgments

Dedicated to the memory of Dr. Richard C. Starr.

Abbreviation

- ITS

internal transcribed spacer

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the PNAS office.

Data deposition: The sequences reported in this paper have been deposited in the GenBank database (see text for accession nos).

References

- 1.Fabry S, Kohler A, Coleman A W. J Mol Evol. 1999;48:94–101. doi: 10.1007/pl00006449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mai J C, Coleman A W. J Mol Evol. 1997;44:258–271. doi: 10.1007/pl00006143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Coleman A W, Preparata R M, Mehrotra B, Mai J C. Protist. 1998;149:135–146. doi: 10.1016/S1434-4610(98)70018-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coleman A W, Mai J C. J Mol Evol. 1997;45:168–177. doi: 10.1007/pl00006217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman A W, Suarez A, Goff L J. J Phycol. 1994;30:80–90. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Angeler D G, Schagerl M, Coleman A W. J Phycol. 1999;35:815–823. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schagerl M, Angeler D G, Coleman A W. Eur J Phycol. 1999;34:87–93. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nozaki H, Itoh M. J Phycol. 1994;30:353–365. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Buchheim M A, Chapman R L. BioSystems. 1991;25:85–100. doi: 10.1016/0303-2647(91)90015-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kirk D L. Volvox: Molecular-Genetic Origins of Multicellularity and Cellular Differentiation. Cambridge, U.K.: Cambridge Univ. Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liss M, Kirk D L, Beyser K, Fabry S. Curr Genet. 1997;31:214–227. doi: 10.1007/s002940050198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nozaki H, Ohta N, Takano H, Watanabe M M. J Phycol. 1999;35:104–112. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Starr R C. J Phycol. 1970;6:234–239. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coleman A W. In: The Protozoa. Hutner S H, Levandowsky M, editors. Vol. 1. New York: Academic; 1979. pp. 307–340. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harris D O. Ph. D. dissertation. Bloomington: Indiana University; 1967. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kirk D L, Harper J F. Int Rev Cytol. 1984;99:217–293. doi: 10.1016/s0074-7696(08)61428-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nozaki H. Phycologia. 1988;27:209–229. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Starr R C. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1968;59:1082–1088. doi: 10.1073/pnas.59.4.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hoops H J. J Cell Sci. 1993;104:105–117. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pocock M A. Trans R Soc S Africa. 1953;34:103–127. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Starr R C. In: Encyclopedia of Plant Physiology. Linskens H F, Heslop-Harrison J, editors. Vol. 17. Berlin: Springer; 1984. pp. 261–290. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ferris P J, Goodenough U W. Cell. 1994;76:1135–1145. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nozaki H, Ohta N, Yamada T, Takano H. Plant Mol Biol. 1998;37:77–85. doi: 10.1023/a:1005904410345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]