Abstract

Arabidopsis thaliana AtMTP1 belongs to the cation diffusion facilitator family and is localized on the vacuolar membrane. We investigated the enzymatic kinetics of AtMTP1 by a heterologous expression system in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which lacked genes for vacuolar membrane zinc transporters ZRC1 and COT1. The yeast mutant expressing AtMTP1 heterologously was tolerant to 10 mm ZnCl2. Active transport of zinc into vacuoles of living yeast cells expressing AtMTP1 was confirmed by the fluorescent zinc indicator FuraZin-1. Zinc transport was quantitatively analyzed by using vacuolar membrane vesicles prepared from AtMTP1-expressing yeast cells and radioisotope 65Zn2+. Active zinc uptake depended on a pH gradient generated by endogenous vacuolar H+-ATPase. The activity was inhibited by bafilomycin A1, an inhibitor of the H+-ATPase. The Km for Zn2+ and Vmax of AtMTP1 were determined to be 0.30 μm and 1.22 nmol/min/mg, respectively. We prepared a mutant AtMTP1 that lacked the major part (32 residues from 185 to 216) of a long histidine-rich hydrophilic loop in the central part of AtMTP1. Yeast cells expressing the mutant became hyperresistant to high concentrations of Zn2+ and resistant to Co2+. The Km and Vmax values were increased 2–11-fold. These results indicate that AtMTP1 functions as a Zn2+/H+ antiporter in vacuoles and that a histidine-rich region is not essential for zinc transport. We propose that a histidine-rich loop functions as a buffering pocket of Zn2+ and a sensor of the zinc level at the cytoplasmic surface. This loop may be involved in the maintenance of the level of cytoplasmic Zn2+.

Zinc is a trace element essential as a cofactor for many enzymes and a structural element for various regulatory proteins (1–3). These proteins and enzymes include zinc-finger proteins, RNA polymerases, superoxide dismutase, and alcohol dehydrogenase. Thus, zinc deficiency causes severe symptoms in all organisms including plants. However, when present in excess, zinc can become extremely toxic, causing symptoms such as chlorosis in plants. The essential but potentially toxic nature of zinc necessitates precise homeostatic control mechanisms to satisfy the requirements of cellular activity and to protect cells from toxic effects.

Plants have many kinds of zinc transporters and zinc channels (4–6). Typical zinc transporters include metal tolerance protein (MTP)3 (7, 8), ZIP (ZRT (zinc-regulated transporter)/IRT (iron-regulated transporter)-like protein) (4), and HMA (heavy metal ATPase) (9) families. The MTP family in Arabidopsis thaliana consists of 12 members, and 4 members, MTP1-MTP4, form a subfamily. Both A. thaliana AtMTP1 (10, 11) and AtMTP3 (12) are localized on the membrane of central vacuoles. A similar transporter in the zinc-hyperaccumulating plant species Arabidopsis halleri, AhMTP1–3, has also been investigated (13). Zinc tolerance of A. halleri has been suggested to be due to an increased copy number of the MTP1 gene and enhanced level of transcription (13, 14). AtMTP1 has high identity with A. halleri AhMTP1–3 (13, 14). AtMTP1, AhMTP1–3, and AtMTP3 belong to a ubiquitous family of transition metal transport proteins called the cation diffusion facilitator protein family, which have been identified in bacteria, Archaea, and eukaryotes and have been demonstrated to transport zinc, cobalt, and cadmium (15).

AtMTP1 has been demonstrated to transport zinc from the cytosol into the vacuole in A. thaliana (10–12) as well as AtMTP3 (12). AtMTP1 has been predicted from the hydropathy to have six transmembrane domains, long N- and C-terminal tails, and a long histidine-rich (His-rich) hydrophilic region between the fourth and fifth transmembrane domains (10, 16). A multiple histidine domain is also present in mammalian orthologues such as mouse ZnT-3 (17). The His-rich domain in these members has been estimated to serve as a zinc binding region (16, 17). However, the transport mechanism and structure-function relationship of these zinc transporters have not been clarified, although zinc transport activity of MTP1 was detected by using reconstituted proteoliposomes of the protein expressed in Escherichia coli (18) and by a yeast complementation assay with a zinc-hypersensitive double mutant of ZRC1 and COT1 (zrc1 cot1) (13, 19).

A. thaliana vacuolar zinc transporter AtMTP1 plays a key role in zinc tolerance and has a His-rich loop. The importance of its physiological function was revealed by the gene disruption mutant of AtMTP1 (10). The His-rich loop consists of 81 residues including 25 histidine residues. Several cation diffusion facilitator family members such as ShMTP1 of hyperaccumulator plant Stylosanthes hamata lack a His-rich region and have different ion selectivity (20). In the present study we expressed AtMTP1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae to determine the kinetic properties; namely, affinity for zinc, ion selectivity, and dependence of the transport activity on a pH gradient. A zinc fluorescent probe enabled us to monitor zinc accumulation into vacuoles in living yeast cells. We also carried out quantitative analysis of zinc transport using radioactive 65Zn2+ and a vacuolar-membrane-enriched fraction from AtMTP1-expressing yeast. Furthermore, expression of a mutant AtMTP1, which lacked a large part of the His-rich loop, revealed the critical role of this motif. We report the experimental results and discuss the biochemical meaning of the His-rich loop of AtMTP1, especially the ion selectivity, affinity to Zn2+, and transport efficiency.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Yeast Strains and Media—The zinc-sensitive mutant zrc1 cot1 (zrc1::LEU2 cot1::TRP1) of yeast (S. cerevisiae) was generated from BJ5458 (ABC710) (MATα, ura3-52, leu2Δ1, lys2-801, his3Δ200, pep4::HIS3, prb1Δ1.6R, can1, trp1, GAL) (21) by the PCR-mediated gene disruption method (22). The ZRC1 locus was replaced with LEU2 gene, and the COT1 locus was replaced with the TRP1 gene. The oligonucleotides used were (5′ ZRC1) 5′-ATGATCACCGGTAAAGAATTGAGAATCATCTCTCTTTTGACAGCTGAAGCTTCGTACGC-3′ and (3′-ZRC1) 5′-TTACAGGCAATTGGAAGTATTGCAGTTTACAGCGTCATCTGCATAGGCCACTAGTGGATC-3′ and (5′ COT1) 5′-ATGAAACTCGGAAGCAAACAGGTCAAAATTATATCCTTGTCGCGCGTTTCGGTGATGAC-3′ and (3′ COT1) 5′-TTAATGATCCTCTAAGCAATCAGCTGTGTTGCAGTTGGCAGGTTGGAATTGTCGACCTCG-3′. Yeast cells were grown in synthetic defined medium with 2% (w/v) glucose. For the metal tolerance assay yeast was grown in liquid HC-U medium that contained 2% glucose, 0.145% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids and ammonium sulfate, 0.5% ammonium sulfate, 0.002% adenine, 0.002% arginine, 0.01% aspartic acid, 0.01% glutamic acid, 0.002% histidine, 0.008% isoleucine, 0.012% lysine, 0.05% leucine, 0.002% methionine, 0.005% phenylalanine, 0.04% serine, 0.02% threonine, 0.006% tyrosine, 0.02% tryptophan, and 0.015% valine. Metal tolerance was determined by the drop assay on HC-U plates containing ZnCl2, NiCl2, CoCl2, or CdCl2 at various concentrations.

Heterologous Expression of AtMTP1 in Yeast—Genomic DNA was extracted from 3-week-old A. thaliana plants by using DNeasy plant mini kit (Qiagen USA, Valencia, CA). The AtMTP1 cDNA was amplified by PCR from genomic DNA using primers 5′-AAGGAATTCATGGAGTCTTCAAGTCCCC-3′ (forward) and 5′-AAGGTCGACGCGCTCGATTTGTATCGTG-3′ (reverse). The DNA fragment was then inserted into the EcoRI-SalI site of URA3-marked, high copy yeast expression vector pKT10 (23). The obtained plasmid was introduced into a zrc1 cot1 strain, which lacks endogenous zinc uptake transporters, by the lithium acetate/single-strand DNA/polyethylene glycol transformation method. Positive Ura+ colonies were selected, and the expression of AtMTP1 was confirmed by immunoblotting with the anti-AtMTP1 antibodies prepared previously (10).

Construction of DNA for AtMTP1 Mutant—The DNA of AtMTP1 mutant that lacks the major part (Gly-185 to His-216) of histidine-rich loop (His-rich loop) (shown in Fig. 6A) was constructed by a PCR and type IIS restriction enzyme-based method (24). A type IIS EsP3I restriction site (underlined) was present in each primer. We used the primer pair 5′-TAGATGCGTCTCTTCATGAACATGGCCATAGTCATGGT-3′ (forward) and 5′-TTGAACCGTCTCGATGATCATGCCCTAGCAGAAC-3′ (reverse). The obtained clone was used as a Δ185–216 mutant AtMTP1. The mutant AtMTP1 DNA was introduced into a zrc1 cot1 strain of yeast by the same method for the wild-type AtMTP1 described above.

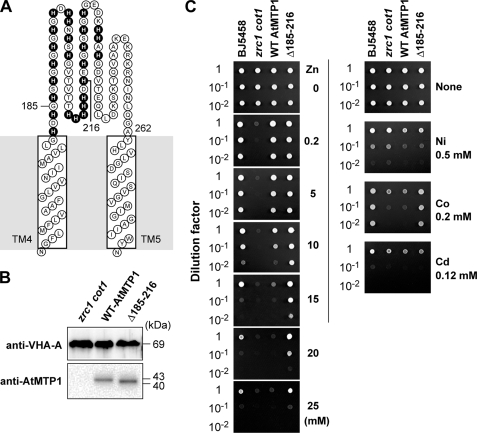

FIGURE 6.

Ion selectivity of AtMTP1 and a His-rich-loop-modified variant. A, schematic model of the His-rich loop between the transmembrane domain 4 and 5. Histidine residues in the loop are highlighted. The His-rich loop mutant lacked the main part of the loop (Δ185–216). B, immunoblots of membranes from yeast cells expressing the wild-type (WT, lane 1) and His-loop mutant (Δ185–216, lane 2) AtMTP1 with anti-AtMTP1 and anti-VHA-A (subunit A of V-ATPase) antibodies. C, yeast mutant strain of zrc1 cot1 was transformed with an empty vector (zrc1 cot1), AtMTP1 (WT AtMTP1), or Δ185–216 mutant (Δ185–216). Original yeast strain BJ5458 expressing empty vector (BJ5458) was also examined. Concentration of cultured cells was adjusted to 1.0 A600, and then 5-μl aliquots of serial dilutions (from top to bottom in each panel) were spotted on HC-U plates supplemented with ZnCl2 at the indicated concentrations (left panel). The plates were supplemented with 0.5 mm NiCl2, 0.20 mm CoCl2, or 0.12 mm CdCl2 (right panel). All plates were incubated for 2 days at 30 °C.

Vacuolar Membrane Vesicle Preparation from Yeast—Yeast cells were grown to the exponential phase in SC-U medium that contained 2% glucose, 0.145% yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, and ammonium sulfate 0.002% adenine, 0.008% inositol, 0.008% p-aminobenzoic acid, and 0.008% amino acids, except for 0.04% leucine and no cysteine. Cells were harvested and treated with zymolyase, and spheroplasts were obtained. The spheroplast suspension was homogenized using a Teflon homogenizer. Vacuolar membranes were isolated from the spheroplast homogenate by a sucrose discontinuous gradient (15 and 35% (w/w) sucrose) centrifugation (25). The obtained membranes were suspended in 5 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.9, 300 mm sorbitol, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 0.5 mm MgCl2, 100 μm p-(amidinophenyl) methanesulfonyl fluoride hydrochloride, and 1 μg/ml leupeptin and stored at -80 °C until used.

Measurements of Zinc Content in Vacuoles with FuraZin-1—Zinc content in yeast vacuoles was measured with a zinc fluorescent probe (26). Yeast cultures (5 ml) were grown to the log phase in Chelex-treated synthetic defined medium supplemented with 10 μm ZnCl2. Chelex-treated synthetic defined medium was prepared by treating the medium, which contained 2% glucose, 0.56% yeast nitrogen base without divalent cations or potassium phosphate (Bio101 Systems, Vista, CA) and 0.002% adenine, 0.008% inositol, 0.008% p-aminobenzoic acid, and 0.008% amino acids except for 0.04% leucine and no cysteine medium (1 liter), with 25 g of Chelex 100 resin (Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 h at 4 °C. The resin was removed, and the medium was supplemented with 7.3 mm KH2PO4, 10 μm FeCl3, 2 μm CuSO4, and 10 μm ZnCl2. The solution was adjusted to pH 4.2 with HCl and then filter-sterilized into polycarbonate flasks. Cells were harvested, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline, and resuspended in the same saline to make a final density of 3 × 108 cells ml-1. A zinc fluorescent probe, FuraZin-1 acetoxymethyl ester (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR; 50 μg) was dissolved in 16.6 μl of 20% pluronic solution (Molecular Probes), and the solution was diluted 4-fold with Me2SO to give a stock solution of 1.25 mm fluorophore and 5% pluronic solution. Fluorophore was added to a 250-μl aliquot of the cell suspension to give a final concentration of 25 μm. The cell suspensions were incubated at 30 °C in the dark for 1 h with agitation. The cells recovered by centrifugation were washed 3 times with 1 ml of chilled solution of 10 mm MES-Tris, pH 6.5, 4 mm MgCl2, 2% glucose (for use as zinc uptake buffer), and 1 mm EDTA and then incubated at 30 °C for 1 h. The cells were then chilled and washed twice with the uptake buffer. Cell pellets were resuspended in 1 ml of uptake buffer and maintained on ice before zinc uptake assays. Fluorometric assay of fluorophore speciation was performed using a RF5300PC fluorospectrophotometer (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). The assay was started by adding an aliquot of yeast cells (10 μl) to 2 ml of MES-Tris uptake buffer containing 100 μm ZnCl2. With the instrument set at maximum scan speed, the excitation wavelength was scanned from 250 to 450 nm, and the intensity of emission at the fixed wavelength of 500 nm was recorded. The corrected traces were scanned to obtain emission intensities at the excitation wavelengths of 325 and 380 nm. The zinc content is referred to as the ratio of excitation fluorescence at 325 nm to that at 380 nm (F325/F380 ratio).

Zn2+ Transport Assay—Zn2+ uptake into vacuolar membrane vesicles was measured using the filtration method (27). Assays were performed at 25 °C in aliquots of medium containing of 300 mm sorbitol, 5 mm MES-Tris, pH 6.9, 25 mm KCl, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 5 mm MgCl2, 200 μm NaN3, 100 μm vanadate, 3 mm ATP-Tris, and 5 μm 65ZnCl2. Radioisotope 65ZnCl2 was purchased from Japan Radioisotope Association (Tokyo, Japan) and RIKEN (Wako, Japan). The specific radioactivity of 65ZnCl2 used for experiments was at a range of 0.3 to 925 TBq/mol. For the assay of the Zn2+/H+ antiporter, membrane vesicles were preincubated with 3 mm ATP-Tris for 5 or 10 min, and then Zn2+ transport was started by adding 65ZnCl2. After the reaction, the mixture was filtered through a presoaked 0.45-μm nitrocellulose filter (13 mm in diameter, Advantech, Tokyo, Japan). The filter was washed twice with 750 μl of cold wash buffer (300 mm sorbitol, 5 mm MES-Tris, pH 6.9, 25 mm KCl, and 100 μm ZnCl2). The radioactivity associated with the filters was measured by a liquid scintillation counter. Background values resulting from incubation with 0.2 μm bafilomycin A1 (Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan), a potent inhibitor of vacuolar H+-ATPase (V-ATPase), were subtracted from corresponding values in the absence of bafilomycin A1 and calculated as V-ATPase-dependent Zn2+/H+ exchanger activity. The proton pumping activity of endogenous V-ATPase in yeast vacuolar membranes was measured as the initial rate of fluorescence quenching of quinacrine at 25 °C with a Shimadzu (Kyoto, Japan) RF5300PC fluorescence spectrophotometer set at 425 nm for excitation and 498 nm for emission as described previously (28).

SDS-PAGE and Immunoblotting—Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to an Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore). After blocking with de-fatted milk, the membrane filter was incubated with the primary antibody and then with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein A (1:2000 dilution) (GE Healthcare). Chemiluminescent reagents of ECL (GE Healthcare) were used for detection of antigens. A specific antibody to the N-terminal region of AtMTP1 (At2g46800, positions 37–50, Cys-GFSDSKNASGDAHE) was prepared by injecting a synthetic peptide into rabbits and used as anti-At-MTP1 antibody (1:2000 dilution) (10). An antibody to the subunit A of V-ATPase was prepared previously (29) and used as anti-VHA-A antibody (1:2000 dilution).

RESULTS

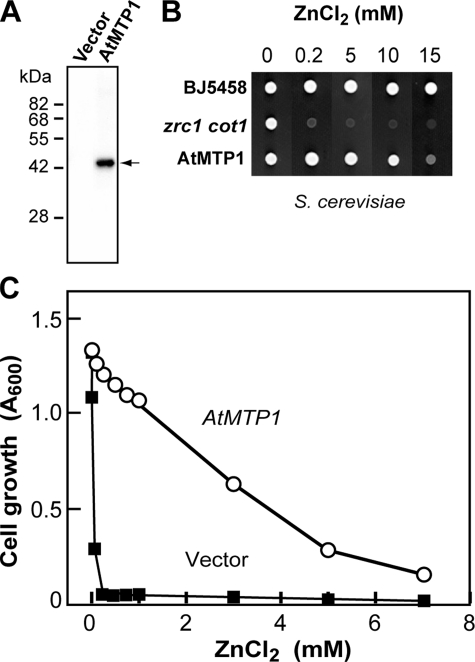

Functional Expression of AtMTP1 in Yeast—To determine the functionality of AtMTP1, we expressed AtMTP1 in S. cerevisiae that contained neither Zrc1 nor Cot1 (zrc1 cot1). AtMTP1 protein was detected at 43 kDa in an immunoblot of the vacuolar membrane fraction from yeast cells expressing AtMTP1 (Fig. 1A). Zinc transport activity was tested by a zinc tolerance assay on an agar plate supplemented with ZnCl2. In this assay, a yeast zrc1 cot1 strain expressing AtMTP1 grew normally and generated colonies, indicating the tolerance to ZnCl2 (Fig. 1B). In contrast, the control yeast strain was transformed with an empty vector. The AtMTP1-expressing yeast strain restored the growth rate in the presence of ZnCl2 up to 10 mm, and it was distinguishable from that of a strain with the empty vector (Fig. 1C).

FIGURE 1.

Functional complementation of AtMTP1 in a zrc1 cot1 mutant strain of yeast. A, AtMTP1 and vector were transformed and expressed in yeast strain that lacked both Zrc1 and Cot1 genes (zrc1 cot1 mutant). Vacuolar membrane fraction (5 μg of protein) was prepared from yeast cells transformed with AtMTP1 and was immunoblotted with the anti-AtMTP1 antibody. The arrow indicates the position of AtMTP1 (43 kDa). B, zinc tolerance assay of original yeast strain cells (BJ5458) expressing empty vector and mutant zrc1 cot1 yeast cells expressing empty vector (zrc1 cot1) or AtMTP1 (AtMTP1). Yeast cultures were adjusted to 1.0 optical density at 600 nm (A600) and 5-μl aliquots were applied to HC-U plates supplemented with the indicated concentrations of ZnCl2. Colony growth was recorded 2 days after incubation at 30 °C. C, zinc tolerance of yeast cells in liquid culture. Yeast strains transformed with AtMTP1 (open circles) or empty vector (closed squares) were incubated in liquid HC-U medium supplemented with indicated concentration of ZnCl2, and A600 of culture was recorded 21 h after incubation at 30 °C. The initial density of cell cultures was 0.01 A600.

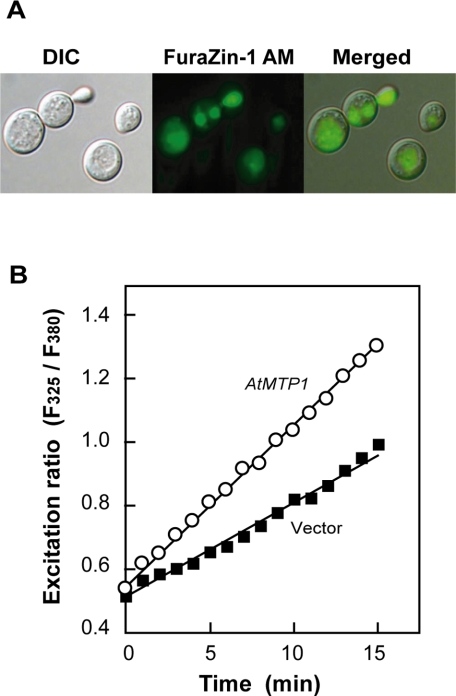

To monitor the active incorporation of zinc into vacuoles in living yeast cells, we used a ratiometric fluorescent zinc indicator FuraZin-1 according to the method reported previously (26). Yeast cells were incubated with the acetoxymethyl ester of FuraZin-1, washed with EDTA, and then treated with glucose to start the zinc uptake. The fluorophore was accumulated predominantly in vacuoles of AtMTP1-expressing cells (Fig. 2A). In assay medium containing 100 μm ZnCl2, vacuoles of AtMTP1-expressing yeast cells showed a rapid increase in the F325/F380 ratio in a time-dependent manner (Fig. 2B). These observations indicate a marked accumulation of Zn2+ into vacuoles of living yeast cells with AtMTP1. Thus, we concluded that the yeast cells are useful for kinetic analysis of AtMTP1.

FIGURE 2.

Measurement of zinc accumulation in living yeast vacuoles. Zinc accumulation in yeast (zrc1 cot1 mutant) cells transformed with AtMTP1 or empty vector was monitored by using the cell-permeable fluorescent probe FuraZin-1 AM. Transformed yeast cells were loaded with FuraZin-1 and photographed. A, yeast cells containing FuraZin-1 probe were incubated with 100 μm ZnCl2 for 10 min and then photographed under a fluorescent microscope. B, cells transformed with AtMTP1 (open circles) or empty vector (closed squares) were added to the zinc uptake buffer containing 100 μm ZnCl2, and then fluorophore speciation in vivo was determined as the change in vacuolar fluorophore signal during the indicated period. DIC, differential interference contrast.

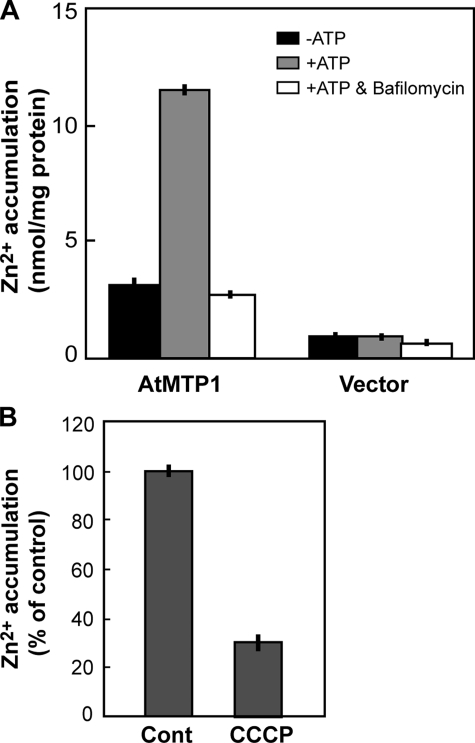

Zn2+/H+ Antiport Activity of AtMTP1—Vacuolar membranes from yeast with AtMTP1, but not from yeast with an empty vector, showed high activity of zinc uptake in an ATP-dependent manner (Fig. 3A). The membrane vesicles were acidified by V-ATPase and then the ΔpH-dependent Zn2+ uptake activity was determined. Preincubation of membrane vesicles with 3 mm ATP for 5 min resulted in maximal activity of the Zn2+/H+ antiport (data not shown). Zinc accumulation into vesicles was inhibited to the control level by 0.2 μm bafilomycin, a specific inhibitor of V-ATPase (30). Next, the Zn2+ accumulation was measured in the presence of a protonophore, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP) (Fig. 3B). Zn2+ accumulation was inhibited by 10 μm CCCP to less than 30%, indicating that the zinc accumulation is tightly associated with a proton gradient generated by V-ATPase.

FIGURE 3.

Zinc uptake by yeast vacuolar membrane vesicles containing AtMTP1. A, vacuolar membranes were prepared from zrc1 cot1 yeast expressing vector alone or AtMTP1. Membrane vesicles (40 μg of protein) were preincubated in uptake medium (200 μl) with (gray boxes) or without (black boxes) 3 mm ATP for 5 min at 25 °C. In some experiments (open boxes) both ATP and bafilomycin A1 (0.2 μm) were added to inhibit V-ATPase. The reaction was started by the addition of 5 μm 65ZnCl2. After 10 min, the membrane vesicles were filtered through a nitrocellulose membrane (pore size, 0.45 μm) and washed with 1.5 ml of cold wash buffer. Filter membranes were dried in air, and then radioactivity was measured. Mean values and S.D. were obtained from three replications. B, vacuolar membrane vesicles (20 μg) isolated from yeast strain AtMTP1/zrc1cot1 were assayed for Zn2+ uptake activity in the presence or absence of 10 μm CCCP. The reaction was started by the addition of 5 μm 65ZnCl2. After reaction at 25 °C for 10 min, radioactivity of 65Zn2+ incorporated into membrane vesicles was determined. V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake was normalized to that without the ionophore (control (Cont)).

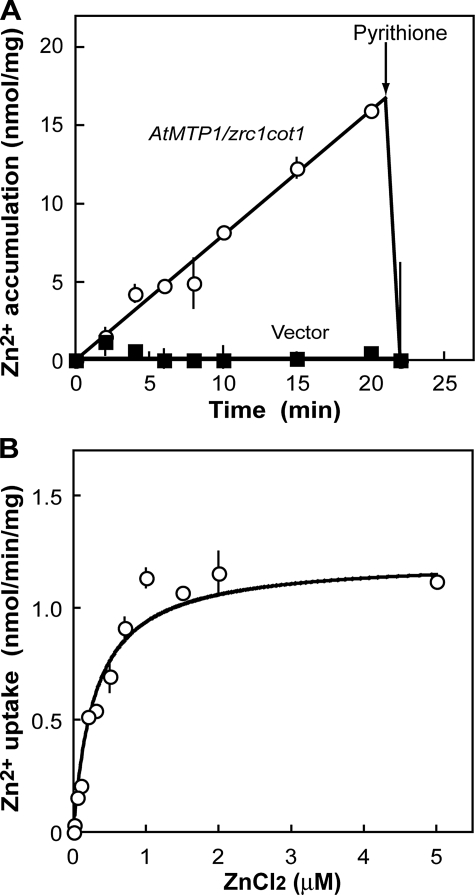

The V-ATPase-dependent (bafilomycin-sensitive) Zn2+ accumulation was measured with the passage of time (Fig. 4A). The amount of Zn2+ in membrane vesicles increased linearly up to 20 min and quickly decreased after the addition of the zinc ionophore pyrithione. Membrane vesicles of the vector control did not accumulate Zn2+. These results indicate that AtMTP1 functions as an active transporter of Zn2+ using a pH gradient. The dependence of the activity on the substrate concentration was determined (Fig. 4B). The zinc uptake activity of AtMTP1 was saturated above 2 μm Zn2+. The curve fitted the Michaelis-Menten equation. The Km value was obtained at a Zn2+ concentration of 0.30 μm, and the Vmax value was 1.22 nmol/min/mg of membrane protein by the Hanes plot analysis (see Fig. 7C).

FIGURE 4.

Zinc uptake kinetics of membrane vesicles containing AtMTP1. A, zinc uptake activity of vacuolar membrane vesicles isolated from yeast zrc1 cot1 mutant transformed with AtMTP1 (open circles) or vector alone (closed squares) with the passage of time. The membrane vesicles (10 μg) were preincubated in uptake medium (1.0 ml) containing 3 mm ATP for 10 min at 25 °C. The same reaction media supplemented with 0.2 μm bafilomycin A1 were also prepared and assayed. The reaction was started by the addition of 5 μm 65ZnCl2 at time 0 and continued for the indicated period. Aliquots (100 μl) of the reaction suspensions were filtered through a nitrocellulose membrane and washed with 1.5 ml of cold wash buffer. Radioactivity of 65Zn2+ in the membrane vesicles was determined. The bafilomycin A1-sensitive zinc uptake activities are plotted as V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake. Mean and S.D. values were obtained from two replications. B, effect of zinc concentration on initial rate of V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake in vacuolar membrane vesicles prepared from yeast cells expressing AtMTP1. The membrane vesicles (2 μg) were preincubated in the uptake medium (200 μl) with or without bafilomycin A1 (0.2 μm) for 2 min at 25 °C. The reaction was started by the addition of 65ZnCl2 solution. After reaction for 2 min, amount of 65Zn2+ in membrane vesicles was determined. The bafilomycin A1-sensitive zinc uptake activities are plotted.

FIGURE 7.

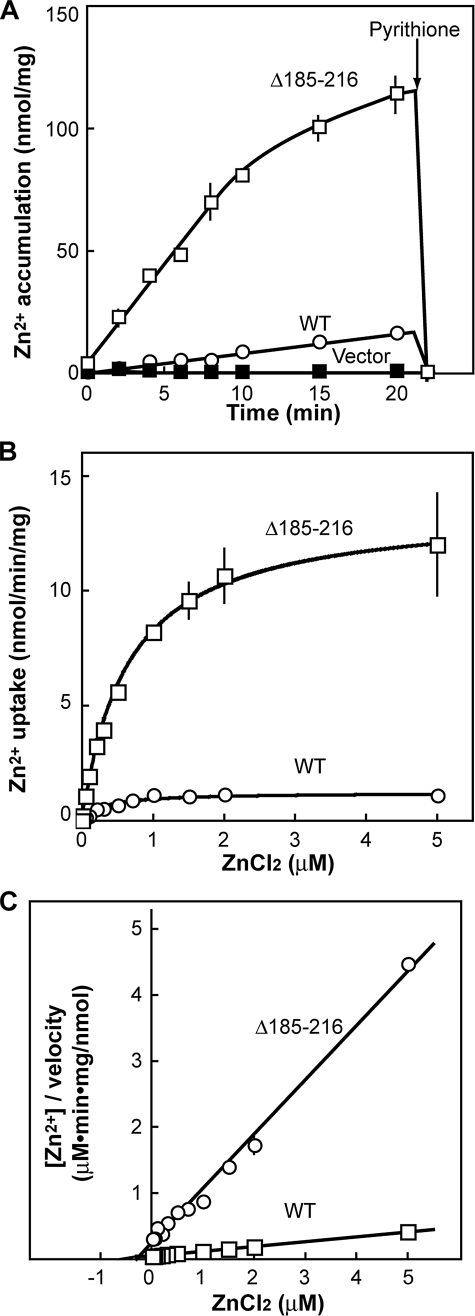

Kinetic properties of a His-loop variant of AtMTP1. A, V-ATPase-dependent 65Zn2+ uptake by AtMTP1 in yeast vacuolar membranes with the passage of time. Yeast vacuolar membranes were isolated from zrc1 cot1 mutant transformed with vector alone, wild-type AtMTP1 (WT), or Δ185–216 mutant. Aliquots of membrane suspension (wild-type and the vector control, 10 μg; Δ185–216 mutant, 1 μg) were preincubated in uptake medium (1.0 ml) containing 3 mm ATP with or without 0.2 μm bafilomycin A1 for 10 min at 25 °C. The assay was carried out as described for Fig. 4, and V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake was plotted. B, effect of zinc concentration on initial rate of V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake in vacuolar membrane vesicles containing AtMTP1 (2 μg) or Δ185–216 mutant (0.2 μg). Mean values and S.D. were obtained from two replications. The membrane vesicles were preincubated in the uptake medium (200 μl) with or without bafilomycin A1 (0.2 μm) for 2 min at 25 °C. The assay was carried out by the same method as described above, and V-ATPase-dependent zinc uptake was plotted. C, Hanes plots for determining kinetic parameters Km and Vmax of wild-type and Δ185–216 AtMTP1. The coefficient of determination (R2) was 0.992 and 0.998 for the wild-type and mutant AtMTP1, respectively.

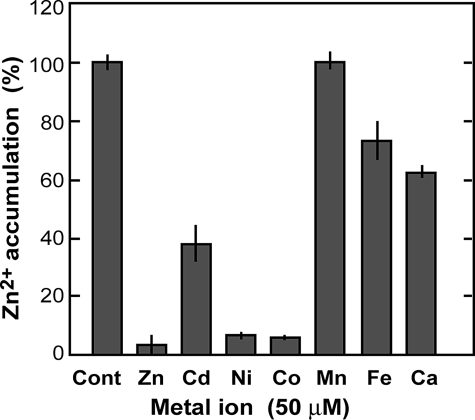

The Zn2+ uptake activity of membrane vesicles from the AtMTP1/zrc1 cot1 strain was measured in the presence of other metal ions in addition to 5 μm 65ZnCl2 (Fig. 5). Mn2+ at 50 μm had no effect on the transport activity. Cd2+ suppressed the activity to 40%, and Fe2+ and Ca2+ suppressed to less than 70% of the control activity. Zinc accumulation was completely inhibited by Ni2+ and Co2+. The activity was thoroughly suppressed in the presence of 50 μm cold Zn2+. We could not test the effect of Mg2+ because the reaction medium contained 5 mm MgCl2 as a cofactor of V-ATPase. Magnesium ion is the most abundant metal in the cytoplasm. However, Mg2+ has no negative effect on AtMTP1 since the activity was detected in the presence of the ion. The negative effect of these ions on the AtMTP1 was either because the metal ions compete with Zn2+ as actual substrates or the metal ions inhibit AtMTP1 through binding to a sensitive site.

FIGURE 5.

Inhibitory effect of divalent metal cations on zinc uptake by AtMTP1. Vacuolar membrane vesicles (40 μg) isolated from yeast cells of AtMTP1/zrc1 cot1 were preincubated in uptake medium (200 μl) with or without 0.2 μm bafilomycin A1 for 10 min at 25 °C. The reaction was started by addition of 5 μm 65ZnCl2 and 50 μm metal ion. After reaction for 10 min, radioactivity of 65Zn2+ in the membrane vesicles was determined. The zinc uptake activity in the presence of bafilomycin A1 is expressed relative to that of the control (Cont) without metals. Mean values and S.D. were obtained from three replications.

Functional Properties of Mutant AtMTP1 Lacking a Histidine-rich Region—AtMTP1 has a log His-rich loop with 81 residues as a characteristic structure (Fig. 6A). We examined its biochemical role by heterologous expression of a mutant AtMTP1, which lacked a major part (32 amino acid residues; positions 185–216) of the loop, in S. cerevisiae zrc1 cot1 mutant strain. Both the wild-type and His-loop mutant (Δ185–216) AtMTP1 proteins in the vacuolar membrane vesicles were detected at similar levels by immunoblotting (Fig. 6B). The mutant AtMTP1 had a slightly smaller molecular size (40 kDa) than the 43-kDa wild type because the mutant lacked 32 residues. The immunostained intensity of the subunit A of V-ATPase (VHA-A), an internal marker protein, was not decreased or increased in yeast cells expressing Δ185–216 AtMTP1.

The zrc1 cot1 mutant did not grow in the presence of Zn2+ at more than 0.2 mm, although the original strain BJ5458 was tolerant to Zn2+ (Fig. 6C, left panel). The yeast cells, into which the wild-type AtMTP1 was introduced, were tolerant to zinc even at 10 mm. The cells expressing a Δ185–216 mutant also were tolerant to zinc and showed a slightly high tolerance to zinc at more than 10 mm compared with the control cells. Thus, the His-rich region is not essential for zinc transport. Sensitivity to other metal ions was examined on an agar plate supplemented with high concentrations of metals. There was no marked difference in tolerance to Ni2+ and Cd2+ between yeast cells with an empty vector, the wild-type AtMTP1, and Δ185–216 AtMTP1 (Fig. 6C, right panel). This suggests that neither the wild-type nor Δ185–216 AtMTP1 preferentially transport Ni2+ or Cd2+ into vacuoles. It should be noted that the yeast cells expressing the mutant became tolerant to 0.2 mm Co2+. This means that the His-rich region is not essential for zinc transport and ion selectivity for Ni2+ and Cd2+ of AtMTP1.

Deletion of the His-rich loop changed the enzymatic properties. Membrane vesicles from yeast cells expressing Δ185–216 AtMTP1 gave extremely high activity of Zn2+ uptake compared with the wild type when assayed at 5 μm 65Zn2+ (Fig. 7A). The wild-type and Δ185–216 AtMTP1 showed a linear increase in the activity for 20 and 10 min, respectively. Thus, we determined the substrate concentration dependence using a reaction time of 2 min (Fig. 7B) and determined kinetic parameters from the Hanes plots (Fig. 7C). Km values for Zn2+ of the wild-type and Δ185–216 AtMTP1 were calculated to be 0.30 and 0.64 μm, respectively. Vmax values of the wild-type and mutant AtMTP1 were 1.22 and 13.6 nmol/min/mg of protein, respectively. The protein amount of wild-type and mutant AtMTP1 on the basis of vacuolar membrane protein was not changed (Fig. 6B). The protein amount of the subunit A of V-ATPase and the activity in yeast cells expressing the mutant were also similar to those of cells expressing wild-type AtMTP1. These results indicate that an enhancement of the transport activity was not due to the increase in the amount of the AtMTP1 protein or proton pump activity. Thus, deletion of a His-rich region from AtMTP1 caused a decrease in affinity for Zn2+ and an 11-fold increase in the maximal velocity of Zn2+ transport.

We prepared another His-loop-deletion mutant, which lacked a part (51 residues; positions 182–232) of the loop. The yeast cells expressing Δ182–232 AtMTP1 were sensitive to Zn2+ at millimolar levels in the growth test, suggesting the dys-function caused by a lack of a large loop.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to clarify the biochemical mechanism of zinc transport by AtMTP1 and the biochemical roles of its His-rich loop. Heterologous expression of A. thaliana vacuolar membrane AtMTP1 in S. cerevisiae cells provided a good experimental system for evaluation of AtMTP1. Plants have two zinc transporters in vacuoles, AtMTP1 (10, 11) and AtMTP3 (12). The vacuolar localization of AtMTP1 and AtMTP3 was demonstrated by expression of their fusion protein with green fluorescent protein in A. thaliana suspension-cultured cells and subcellular fractionation of membranes prepared from plants (10–12). The physiological roles of zinc detoxification under zinc oversupply were demonstrated by phenotypic analysis of AtMTP1 (10) and by overexpression analysis of AtMTP3 (12). AtMTP1 complements the function of yeast vacuolar Zrc1 and Cot1 (Fig. 1). The zrc1 cot1 double mutant strain is highly sensitive to zinc and unable to grow in the presence of low concentrations of ZnCl2. Zrc1 and Cot1 are known to contribute to zinc tolerance by sequestration of excess zinc into vacuoles in yeast (26, 31, 32), and Zrc1 is considered the major transporter for zinc tolerance (26). Thus, we concluded that AtMTP1 was correctly localized in the vacuoles and kept its functionality in yeast cells.

Functionality of AtMTP1 as a Zn2+/H+ Antiporter in the Vacuolar Membrane—The present study revealed that AtMTP1 actively transports Zn2+ into vacuoles by using a pH gradient formed by V-ATPase. The heterologously expressed AtMTP1 in yeast cells has been demonstrated to function on the vacuolar membranes by using a fluorescent probe of Zn2+ (Fig. 2). The transport of Zn2+ was supported by a pH gradient across the membrane. In yeast cells, V-ATPase acidifies vacuoles, and AtMTP1 uses the pH gradient as an energy source. Zn2+ uptake was completely inhibited by a potent V-ATPase inhibitor bafilomycin A1 (30) and was strongly suppressed by CCCP a protonophore (Fig. 3). The membrane vesicles accumulated zinc in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 4). In addition to V-ATPase, H+-translocating pyrophosphatase works as a proton pump in vacuoles of plants (33–35), although the enzyme is absent in yeast. In growing young tissues of plants, the proton pump activity of H+-pyrophosphatase is comparable or higher than that of V-ATPase (36). Thus, AtMTP1 utilizes a pH gradient generated by two vacuolar proton pumps, V-ATPase and H+-pyrophosphatase.

We examined the metal selectivity of AtMTP1 by two methods. From the competition assay, Ni2+ and Co2+ strongly inhibited the Zn2+ uptake activity, and Cd2+, Fe2+, and Ca2+ also partially inhibited the transport activity (Fig. 5). The metals other than Fe2+ did not inhibit V-ATPase in yeast vacuolar membrane at the assay concentrations (data not shown). Fe2+ inhibited V-ATPase to 73% of the control activity. The results suggest that these metals, such as Ni2+ and Cd2+, competitively inhibit AtMTP1 as additional transport substrates. However, the possibility was not confirmed by further experiments. AtMTP1 expressed in yeast cells showed no capacity to transport Ni2+, Co2+, or Cd2+ in the yeast growth test (Fig. 6C). The atmtp1 mutant plants of A. thaliana were hypersensitive to Zn2+ but not to Ni2+, Co2+, Mn2+, and Cd2+ (10). Therefore, AtMTP1 might function via a Zn2+/H+ antiporter mechanism with a relatively high selectivity to zinc both in vitro and in vivo. Metal specificity varied with the transporters. Yeast vacuolar Zrc1 has a high specificity to zinc, and yeast vacuolar Cot1 has the capacity to transport zinc and cobalt (26). Thlaspi goesingense vacuolar membrane TgMTP1 has been estimated to have a broad specificity for zinc, cadmium, nickel, and cobalt (37). A. thaliana vacuolar membrane AtMTP3 that contains a short His-rich loop has also been reported to be specific to zinc (12).

Role of a His-rich Loop in AtMTP1—As mentioned above, the His-rich region of TgMTP1 was tightly related to the metal selectivity (37). In hZIP4, a human plasma membrane zinc importer, a His-rich cluster has been reported to mediate the ubiquitination and degradation of hZIP4 at the upper tier of physiological zinc concentrations more than 20 μm (38). In the presence of excessive zinc, the zinc-saturated hZIP4 becomes a target molecule of ubiquitination. This mechanism is useful for protection against zinc cytotoxicity because the decrease in the hZIP4 suppresses the import of excess zinc into the cells. In contrast to the present study, histidine residues in the His-rich loop have been reported to be essential for zinc transport in PC-3 cells (39). The differences in roles of His-rich regions may be due to their amino acid sequences. His-rich loop of AtMTP1 is richest in histidine residues among zinc transporters.

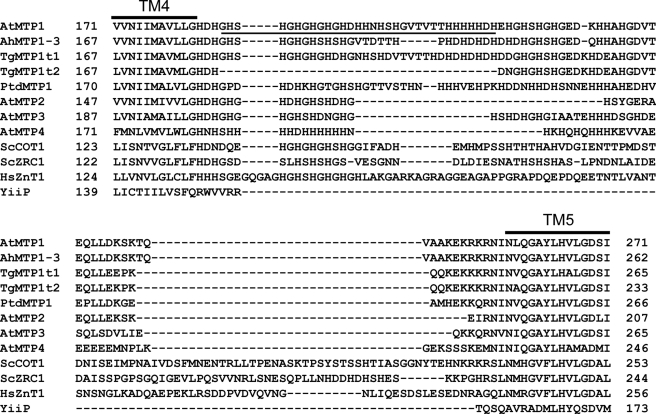

We examined the contribution of the region to the metal selectivity. The His-rich loop is a candidate for the metal selectivity determinant. In T. goesingense, two TgMTP1 mRNA are generated from a single gene; a unspliced (TgMTP1t1) and a spliced (TgMTP1t2) transcript (37). The sequence of TgMTP1 is similar to that of AtMTP1. TgMTP1t2 lacks a His-rich region (Fig. 8). This region contains 13 histidine residues and has an identity of 58% with AtMTP1. TgMTP1t1 has been demonstrated to transport cadmium, cobalt, and zinc, and TgMTP1t2 conferred the high tolerance to nickel (37). Analysis of the T. goesingense transporter suggested that the His-rich loop might be involved in the substrate specificity of TgMTP1. The present results showed that the His-rich region is involved in the substrate specificity because the tolerance to Co2+ was increased in the yeast strain expressing a Δ185–216 mutant (Fig. 6). However, the contribution of the region to ion selectivity was not critical, since the tolerance to Ni2+ and Cd2+ was apparently not changed. Ni2+ and Co2+ may compete with Zn2+ for binding to the His-rich region because the His-rich region of dehydrin from citrus has been reported to have a high affinity for Cu2+, Ni2+, Zn2+, and Co2+ (40). Capacity of the mutant AtMTP1 to transport Co2+ and Ni2+ remains to be examined by the direct assay using radioisotopes of the metals. The yeast strain expressing a Δ185–216 mutant did not become tolerant to Ni2+ like TgMTP1t2. Thus, an ion selectivity filter may exist in the other domains including transmembrane domains. The filter might recognize the ion radius of zinc. Zn2+ and Co2+ have similar ion radii of 75.0 and 74.5 pm, respectively, and are different in size from Ni2+ (69 pm) and Cd2+ (95 pm) (41). We estimate that the deletion of the His-rich region slightly changes the configuration of ion selectivity filter and that the mutant AtMTP1 transports Zn2+ and Co2+ with a similar ion radius.

FIGURE 8.

Amino acid sequence alignment of the histidine-rich region among several cation diffusion facilitator family members. A. thaliana AtMTP1 (DDBJ/GenBank™/EBI accession number AF072858) AtMTP2 (AL138642-11), AtMTP3 (AM231755), AtMTP4 (BT015899), A. halleri AhMTP1–3 (AJ556183), T. goesingense TgMTP1t1 (AY560017), TgMTP1t2 (AY560018), Populus trichocarpa × Populus deltoides PtdMTP1 (AY450453), S. cerevisiae ScCOT1 (Z75224), ScZRC1 (Z48756-5), Homo sapiens HsZnT1 (AF323590), E. coli K12 YiiP (AE014075-4763) are aligned. The predicted transmembrane domains 4 and 5 (TM4 and TM5) of AtMTP1 are marked by lines. The truncated region of the Δ185–216 AtMTP1 is underlined.

The present study revealed that the His-rich region is not essential to zinc transport (Fig. 6). A key question to be addressed is what role the His-rich region plays in the AtMTP1. The kinetic analysis of the Δ185–216 mutant revealed that the removal of the His-rich region markedly increased the apparent maximal velocity of zinc transport and lowered the affinity to Zn2+ (Fig. 7). This multiple histidine region of AtMTP1 is composed of 32 residues and contains 16 histidine residues and only two acidic residues (Fig. 6). This region has a high affinity to Ni2+, Co2+, and Zn2+ because the histidine residue has a high affinity to these metal ions (42). The present results suggest that the His-rich region binds Zn2+ ions in the cytosol and that the ions are transferred from the His-rich region to the pore region consisting of transmembrane domains. A high affinity for Zn2+ means stable binding of ions, and this becomes an energy barrier for transfer of ions. Removal of Zn2+ from histidine residues might require relatively high energy. When AtMTP1 lacked the His-rich region, Zn2+ ion can be transported without being trapped at the His-rich region in the cytoplasmic space. In this case the energy required for ion transport may be low, and consequently, the transport velocity might increase. In other words, the His-rich region functions as a concentration sensor and buffering pocket of cytoplasmic Zn2+ to collect the excess ions in the vacuole. Thus, this structure has a physiological merit to plant cells. This also keeps the cytoplasmic concentration of Zn2+ at a low level and protects the cells from zinc toxicity.

The characteristic of the Δ185–216 AtMTP1 was a slight decrease in the affinity for Zn2+ (Fig. 7). The relatively high affinity of wild-type AtMTP1 may be due to the Zn2+ concentration effect at the His-rich loop. In total, the His-rich loop collects Zn2+ ions in the cytoplasm and may function as a sensor of zinc concentration in the cytosol for zinc deposition into the vacuole. At low Zn2+ concentrations, the ions are trapped by the loop and not transported into vacuoles. This is important to keep Zn2+ in the cytoplasm, where many zinc-proteins and zinc-enzymes utilize the ion. When zinc is oversupplied, the His-rich loop may be saturated with Zn2+, and the ions are easily transferred to the zinc entrance pocket of AtMTP1 and then transported into vacuoles. The Km value of AtMTP1 for Zn2+ was 0.30 μm in yeast membrane vesicles (Fig. 7). This value was comparable to the S. cerevisiae endogenous zinc transporter ZRC1 (0.16 μm) (43), E. coli ZitB (1.4 μm) (44), and human hZIP4 (2.5 μm) (38). The obtained Km of AtMTP1 is of importance physiologically, since most zinc-proteins have high affinity to zinc (3), and the zinc toxicity was observed above 200 μm in the AtMTP1 knock-out mutant atmtp1 plants (10). The Km value is one of the determinant factors of the concentration of free Zn2+ remained in the cytosol.

In conclusion, we propose that the His-rich region of AtMTP1 has unique functions, namely, serving as a buffering pocket to catch and stock zinc in the vacuole and as a sensor of the cytoplasmic free zinc ions. Excess Zn2+ in the cytosol may be trapped by the His-rich region and then actively transported into vacuole through AtMTP1. On the other hand, the trapped Zn2+ may be released to the cytosol when the zinc concentration is decreased. The His-rich loop has been reported to function as a sensor for high periplasmic levels of zinc has been discussed for the Synechocystis zinc transporter that belongs to the ABC transporter family (45). Furthermore, Lu and Fu (46) recently reported the x-ray structure of a E. coli Zn2+/H+ exchanger YiiP in complex with zinc. YiiP, consisting of 298 residues and 6 transmembrane domains, exists as a Y-shaped structure of homodimer. The C-terminal part of YiiP forms a zinc binding portion. At present, it is impossible to adopt this structural model to AtMTP1 because YiiP is a member of the zinc transporter group lacking the His-rich region. Identification of the tertiary structure and kinetic properties of the Hisrich loop, especially the His-rich region from positions 185 to 216, and further investigations of the phenotypic properties of the plants overexpressing the His-rich region and Δ185–216 mutant AtMTP1 should provide insight into how the loop associates with the physiological roles of the transporter.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Yoichi Nakanishi for valuable discussion and Sumiko Kaihara for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported in part by grants-in-aid for scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Sports, Culture, Science, and Technology of Japan, PROBRAIN, RITE, and a grant from Global Research Program of the Ministry of Science and Technology, Korea (to M. M.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: MTP, metal tolerance protein; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone; V-ATPase, vacuolar H+-ATPase; MES, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid.

References

- 1.Christianson, D. W. (1991) Adv. Protein Chem. 42 281-355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marschner, H. (1995) in Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants (Marschner, H., ed) 2nd ed., pp. 347-364, Academic Press, Ltd., London

- 3.Gamsjaeger, R., Liew, C. K., Loughlin, F. E., Crossley, M., and Mackay, J. P. (2007) Trends Biochem. Sci. 32 63-70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guerinot, M. L. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465 190-198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Krämer, U. (2005) Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16 133-141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van der Zaal, B. J., Neuteboom, L. W., Pinas, J. E., Chardonnens, A. N., Schat, H., Verkleij, J. A. C., and Hooykaas, P. J. J. (1999) Plant Physiol. 119 1047-1056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Krämer, U. (2005) Trends Plant Sci. 10 313-315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blaudez, D., Kohler, A., Martin, F., Sanders, D., and Chalot, M. (2003) Plant Cell 15 2911-2928 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams, L. E., and Mills, R. F. (2005) Trends Plant Sci. 10 491-502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kobae, Y., Uemura, T., Sato, M. H., Ohnishi, M., Mimura, T., and Maeshima, M. (2004) Plant Cell Physiol. 45 1749-1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desbrosses-Fonrouge, A.-G., Voigt, K., Schröder, A., Arrivault, S., Thomine, S., and Krämer, U. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579 4165-4174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arrivault, S., Senger, T., and Krämer, U. (2006) Plant J. 46 861-879 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dräger, D. B., Desbrosses-Fonrouge, A. G., Krach, C., Chardonnens, A. N., Meyer, R. C., Saumitou-Laprade, P., and Krämer, U. (2004) Plant J. 39 425-439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Becker, M., Talke, I. N., Krall, L., and Krämer, U. (2004) Plant J. 37 251-268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paulsen, I. T., and Saier, M. H. (1997) J. Membr. Biol. 156 99-103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams, L. E., Pitman, J. K., and Hall, J. L. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1465 104-126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Palmiter, R. D., and Findley, S. D. (1995) EMBO J. 14 639-649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bloβ, T., Clemens, S., and Nies, D. H. (2002) Planta 214 783-791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim, D., Gustin, J. L., Lahner, B., Persans, M. W., Baek, D., Yun, D. J., and Salt, D. E. (2004) Plant J. 39 237-251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Delhaize, E., Kataoka, T., Hebb, D. M., White, R. G., and Ryan, P. R. (2003) Plant Cell 15 1131-1142 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jones, E. W. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 194 428-453 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wach, A. (1996) Yeast 12 259-265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka, K., Nakafuku, M., Tamanoi, F., Kaziro, Y., Matsumoto, K., and Toh-e, A. (1990) Mol. Cell. Biol. 10 4303-4313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shigaki, T., and Hirschi, K. D. (2001) Anal. Biochem. 298 118-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakanishi, Y., Saijo, T., Wada, Y., and Maeshima, M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276 7654-7660 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacDiarmid, C. W., Milanick, M. A., and Eide, D. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 15065-15072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ueoka-Nakanishi, H., Tsuchiya, T., Sasaki, M., Nakanishi, Y., Cunningham, K. W., and Maeshima, M. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267 3090-3098 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matsuura-Endo, C., Maeshima, M., and Yoshida, S. (1992) Plant Physiol. 100 718-722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Matsuura-Endo, C., Maeshima, M., and Yoshida, S. (1990) Eur. J. Biochem. 187 745-751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowman, E. J., Siebers, A., and Altendorf, K. (1988) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 85 7972-7976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kamizono, A., Nishizawa, M., Teranishi, Y., Murata, K., and Kimura, A. (1989) Mol. Gen. Genet. 219 161-167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conklin, D. S., Culbertson, M. R., and Kung, C. (1994) Mol. Gen. Genet. 244 303-311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sze, H., Li, X., and Palmgren, M. G. (1999) Plant Cell 11 677-689 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Maeshima, M. (2000) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1456 37-51 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gaxiola, R. A., Palmgren, M. G., and Schumacher, K. (2007) FEBS Lett. 581 2204-2214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nakanishi, Y., and Maeshima, M. (1998) Plant Physiol. 116 589-597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Persans, M. W., Nieman, K., and Salt, D. E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 9995-10000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mao, X., Kim, B.-E., Wang, F., Eide, D. J., and Petris, M. J. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282 6992-7000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milon, D., Wu, Q., Zou, J., Costello, L. C., and Franklin, R. B. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1758 1696-1701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hara, M., Fujinaga, M., and Kuboi, T. (2005) J. Exp. Bot. 56 2695-2703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shannon, R. D., and Prewitt, C. T. (1970) J. Inorg. Nucl. Chem. 32 1427-1441 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lippard, S. J., and Berg, J. M. (1994) Principles of Bioinorganic Chemistry, University Science Books, Herndon, VA

- 43.MacDiarmid, C. W., Milanick, M. A., and Eide, D. J. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 39187-39194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anton, A., Weltrowski, A., Haney, C. J., Franke, S., Grass, G., Rensing, C., and Nies, D. H. (2004) J. Bacteriol. 186 7499-7507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wei, B., Randich, A. M., Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi, M., Pakrasi, H. B., and Smith, T. J. (2007) Biochemistry 46 8734-8743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lu, M., and Fu, D. (2007) Science 317 1746-1748 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]