Abstract

The photosystem II subunit PsbS is essential for excess energy dissipation (qE); however, both lutein and zeaxanthin are needed for its full activation. Based on previous work, two models can be proposed in which PsbS is either 1) the gene product where the quenching activity is located or 2) a proton-sensing trigger that activates the quencher molecules. The first hypothesis requires xanthophyll binding to two PsbS-binding sites, each activated by the protonation of a dicyclohexylcarbodiimide-binding lumen-exposed glutamic acid residue. To assess the existence and properties of these xanthophyll-binding sites, PsbS point mutants on each of the two Glu residues PsbS E122Q and PsbS E226Q were crossed with the npq1/npq4 and lut2/npq4 mutants lacking zeaxanthin and lutein, respectively. Double mutants E122Q/npq1 and E226Q/npq1 had no qE, whereas E122Q/lut2 and E226Q/lut2 showed a strong qE reduction with respect to both lut2 and single glutamate mutants. These findings exclude a specific interaction between lutein or zeaxanthin and a dicyclohexylcarbodiimide-binding site and suggest that the dependence of nonphotochemical quenching on xanthophyll composition is not due to pigment binding to PsbS. To verify, in vitro, the capacity of xanthophylls to bind PsbS, we have produced recombinant PsbS refolded with purified pigments and shown that Raman signals, previously attributed to PsbS-zeaxanthin interactions, are in fact due to xanthophyll aggregation. We conclude that the xanthophyll dependence of qE is not due to PsbS but to other pigment-binding proteins, probably of the Lhcb type.

Nonphotochemical quenching (NPQ)2 is a protective mechanism against overexcitation of photosystem II, consisting of heat dissipation of excess energy. This process, although present in all photosynthetic organisms, has been particularly studied in higher plants and green algae. Early work identified thylakoid lumen acidification as an essential factor for NPQ (1). Excess light increases proton pumping into the thylakoid lumen, which elicits chlorophyll fluorescence quenching dependent on protein protonation events. This is shown by the inhibitory effects of DCCD, a protein-modifying agent that covalently binds to protonatable residues in hydrophobic environments (2). It has been found that the photosystem II subunit PsbS, a DCCD-binding protein (3), is required for NPQ and, in particular, for its rapid and reversible component qE (4). In fact, the capacity for qE depends on the stoichiometric presence of PsbS polypeptide (5). Some insight into the importance of xanthophylls for the NPQ mechanism can be gained from the xanthophyll biosynthesis mutants found in NPQ-depleted plants. In the npq1 mutant, which is unable to convert violaxanthin into zeaxanthin upon lumen acidification, qE is reduced, whereas npq2, which constitutively accumulates zeaxanthin, has faster NPQ induction and slower relaxation kinetics (6). In the lut2 mutant, lacking lutein (7), and in the lut2/npq2 double mutant, which has zeaxanthin as the only xanthophyll (8, 9), qE is also significantly reduced, whereas the npq1/lut2 double mutant totally lacks qE (10). Because xanthophyll mutants have normal PsbS levels and the npq4 mutation is epistatic over xanthophyll biosynthesis mutations (4), these data suggest that both lutein and zeaxanthin are involved in the mechanism of quenching downstream PsbS activation by lumen acidification.

A more detailed analysis of PsbS activation has been obtained by studying the DCCD-binding properties of two lumen-exposed glutamate residues in PsbS, Glu-122 and Glu-226. Inactivation of each site in Arabidopsis thaliana by construction of the point mutants E122Q and E226Q decreases by 50% both qE and DCCD binding capacity, as glutamine is not protonatable in the physiological pH range, whereas the double mutant is analogous to the PsbS deletion mutant npq4 (11). Thus PsbS has two independent functional domains, the first activated by protonation of Glu-122 and the second by protonation of Glu-226. These residues are localized symmetrically with respect to the 2-fold mirror axis within the four-helix structure of PsbS. The need for two xanthophyll species and two activated DCCD binding domains, for full expression of qE, has been rationalized in the “two xanthophyll-binding sites” model (12, 13), which proposes that protonation of each glutamate residue (Glu-122 and Glu-226) activates a corresponding binding site for de-epoxidized xanthophylls. This model was supported by the following: (i) the finding that a 535 nm spectral feature appearing during establishment of qE was PsbS-dependent and exhibited the Raman spectrum of zeaxanthin (14), and (ii) the report that in vitro binding of zeaxanthin by PsbS (15) reproduced the zeaxanthin absorption spectral feature at ∼530 nm. The two xanthophyll-binding sites model, however, does not explain the low NPQ phenotype of the npq5 mutant of Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, which lacks the Lhcbm1 subunit of the major antenna complex (16), and of the ch1 mutant of A. thaliana, depleted in antenna proteins while retaining a normal level of PsbS, lutein, and zeaxanthin (3, 17). Additional emphasis on Lhcb proteins as quenching sites was recently provided by the report that A. thaliana lacking Lhcb6 has reduced qE (18). An alternative model that reconciles these observations can be proposed in which the phenotypes related to lumen acidification are due to PsbS activation, whereas the phenotypes of xanthophyll biosynthesis mutations are mediated by xanthophyll binding to Lhc proteins (19-22). In such a model PsbS would act as a pH-sensitive trigger, and quenching would be performed by chlorophyll-carotenoid-binding proteins activated though a conformational change of PsbS and propagated to neighboring antenna proteins. A distinctive critical characteristic between the two models is whether PsbS binds lutein and/or zeaxanthin or not. It is worth noting that xanthophyll binding is well established for Lhc proteins but controversial for PsbS (3, 15, 23). Pigment binding to PsbS would support the Two xanthophyll-binding site model, although PsbS without pigments would support the second model, which will be denoted as the “PsbS trigger” model.

In this work we have studied in vivo the dependence of NPQ on xanthophyll composition by combining xanthophyll biosynthesis mutations npq1 (6) and lut2 (7, 24) with mutations on each of the DCCD-binding sites of PsbS (13). Moreover, we have studied in vitro the xanthophyll and chlorophyll binding capacity of recombinant PsbS. The results are discussed in terms of their consistency with the above models.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plant Material and Construction of Double Mutants—Pollen from A. thaliana PsbS point mutants E122Q and E226Q (11) was used to fertilize pistils of previously emasculated double mutant plants npq1/npq4 (26) and lut2/npq4.3

We obtained four double mutants, E122Q/npq1, E122Q/lut2, E226Q/npq1, and E226Q/lut2, and we checked for homozygosis before use. Other control genotypes used in this work are npq4 complemented with WT PsbS (11), npq4 (4), npq1, lut2, and npq1/lut2 (24). All mutants are in the Col-O ecotype background.

NPQ Measurements—NPQ measurements were performed using a PAM-101 (Waltz, Effeltrich, Germany), actinic light 1260 μEm-2s-1, and saturating light 3380 μEm-2s-1. Minimum fluorescence (F0) was measured with a 0.15 μmol m-2 s-1 beam; Fm was determined with a 0.8-s light pulse, and continuous light was supplied by a KL1500 halogen lamp (Schott, Mainz, Germany). NPQ is expressed as (Fm - Fm′)/Fm′.

Pigment Analysis—Pigments were extracted from leaf disks; samples were frozen in liquid nitrogen and ground in 85% acetone buffered with Na2CO3, and then the supernatant of each sample was recovered after centrifugation (15 min at 15,000 × g, 4 °C); separation and quantification of pigments were performed by HPLC (27).

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot—SDS-PAGE of thylakoid membranes samples (28) was performed with the Tris-Tricine buffer system as described previously (29), and proteins were transferred to a nitrocellulose filter and developed using a polyclonal rabbit antiserum.

Recombinant PsbS Overexpression and Purification—The coding region for the mature protein was amplified by PCR on a full-length cDNA encoding Hordeum vulgare (cultivar Nure) PsbS (forward primer, CCAGGATCCGCGCCGGCCAAGAAGGTCG; reverse primer, GGGAAGCTTGTCGTCGTCCTCGCCGCTG) and cloned in pQE50/His vector (Invitrogen) under pLac promoter control in fusion with a 6-histidine tail at the C terminus. The recombinant protein was overexpressed in Escherichia coli, BL21 strain (Invitrogen), purified from bacterial lysate using 0.5% Triton X-100 and 0.5% SDS, then loaded on a nickel immobilized methyl affinity chromatography (chelating Sepharose Fast Flow, Amersham Biosciences), and eluted in the Reconstitution Buffer (40 mm Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.8, 12.5% sucrose, 2% LDS, 5 mm 6-aminocaproic acid, 1 mm benzamidine).

In Vitro Reconstitution of PsbS Protein with Pigments—In vitro refolding was performed with purified pigments as described previously (30). The refolding experiments were also performed at different pH values, changing Hepes-NaOH buffer, pH 7.8, with Mes-NaOH buffer, pH 5.5. In vitro refolding by sonication of recombinant PsbS with zeaxanthin and/or lutein was performed as described previously (15).

In Vitro Refolding without Pigments—Starting from the recombinant protein in denaturing buffer (40 mm Hepes-NaOH, pH 7.8, 12.5% sucrose, 2% LDS, 5 mm 6-aminocaproic acid, 1 mm benzamidine), LDS was precipitated by adding 150 mm KCl and exchanged with 1% n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside. The sample, now in milder detergent conditions, was ultracentrifuged for 15 h in an SW 60 Beckman rotor at 60,000 rpm. In addition to 0.1-1 m sucrose, the gradient solution contained 0.1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside and 5 mm phosphate, pH 7.5.

Circular Dichroism and Absorption Measurements—CD spectra were obtained with a Jasco J-600 spectropolarimeter, scan rate 200 nm/min. Absorption spectra were obtained with an AMINCO DW2000 spectrophotometer, scan rate 2 nm/s, bandwidth 1 nm, optical path length 1 cm.

Resonance Raman Spectra—The resonance Raman spectra were obtained with excitation at 441.6 nm using a He-Cd laser (Kimmon, IK4121R-G), 514.5 nm using an Ar+ laser (Coherent, Innova 90/5) and 530.9 nm using a Kr+ laser (Coherent, Innova 302). The backscattered light from a slowly rotating NMR tube was collected and focused into a triple spectrometer (consisting of two Acton Research SpectroPro 2300i and a SpectroPro 2500i in the final stage with 1800 grooves/nm grating) working in the subtractive mode, equipped with a liquid nitrogen-cooled CCD detector (Roper Scientific Princeton Instruments). The RR spectra were calibrated with indene as standard to an accuracy of 1 cm-1 for isolated bands. The peak intensities and positions of the C-H wagging vibrations in the 900-1000-cm-1 region were determined by a curve-fitting program (LabCalc, Galactic) using Lorentzian line shapes and 8.5-cm-1 bandwidth.

RESULTS

In Vivo Analysis of Xanthophyll Binding to PsbS and Interaction between DCCD-binding Sites and Xanthophyll-binding Sites—We approached the problem of assessing whether PsbS binds xanthophylls by crossing A. thaliana carrying single Glu → Gln mutations at either of the two DCCD-binding residues Glu-122 and Glu-226 of PsbS (13) with npq1/npq4 and lut2/npq4 genotypes, lacking PsbS and zeaxanthin or lutein, respectively.

The rationale of this experiment was to verify whether the observed effect of xanthophyll composition on NPQ (7), namely a reduced NPQ amplitude whenever either lutein or zeaxanthin is absent, can be explained by the properties of the two putative xanthophyll-binding sites of PsbS as proposed by the two xanthophyll sites model. This was achieved by inactivation of each DCCD-binding site and changing the xanthophyll composition of the plant. Screening of the F2 progeny for xanthophyll composition, in dark conditions and after high light exposure, and for the PsbS protein enabled four double mutants, E122Q/npq1, E122Q/lut2, E226Q/npq1, and E226Q/lut2, to be obtained. Four-week-old plants of control genotypes npq1, lut2, npq1/lut2, PsbS E122Q, PsbS E226Q, the double mutant PsbS E122Q/E226Q, npq4, and the four newly obtained double mutants were assayed for NPQ (Figs. 1, 2, 3).

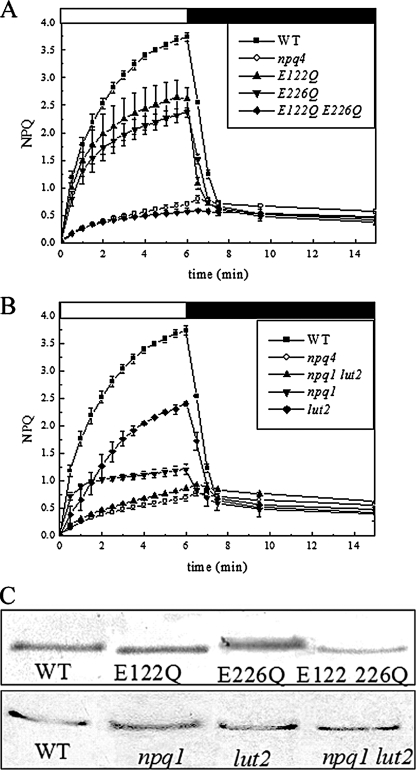

FIGURE 1.

Single mutants phenotypes. NPQ activity of the single mutant genotypes used in this work. A, single Glu → Gln mutants have approximately 50% qE amplitude with respect to WT, whereas the double Glu → Gln mutant shows no qE. B, lut2 and npq1 mutants have reduced qE with respect to WT, and the npq1/lut2 double mutant has no qE. C, immunoblotting of thylakoid membranes with an anti-PsbS antibody showing that all genotypes have comparable amounts of PsbS on a chlorophyll content basis with respect to WT with the exception of the E122Q/E226Q double mutant, which has a 40% reduction.

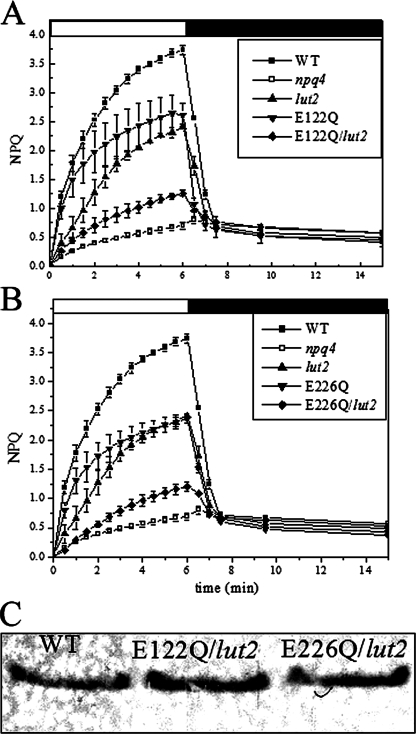

FIGURE 2.

Double mutants (lut2 background) phenotypes. NPQ activity of the double mutants E122Q/lut2 and E226Q/lut2. A, E122Q/lut2 has reduced qE with respect to both lut2 and E122Q. B, E226Q/lut2 has reduced qE with respect to both lut2 and E226Q. C, immunoblotting of thylakoid membranes with anti-PsbS antibodies showing that lut2 double mutants have comparable amounts of PsbS with respect to WT.

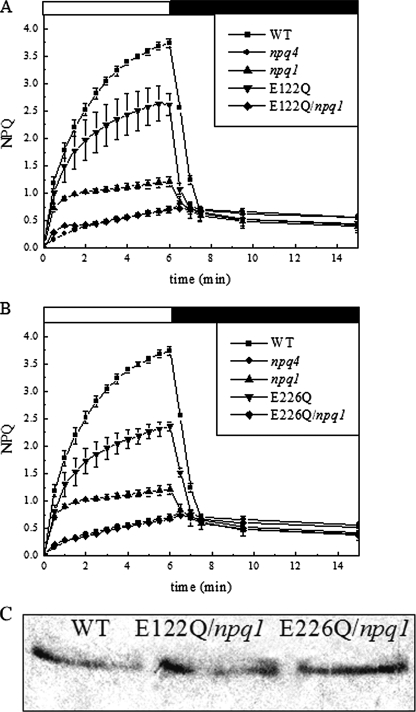

FIGURE 3.

Double mutant (npq1 background) phenotypes. NPQ activity of the double mutant npq1 E122Q and genotypes. A, E122Q/npq1 has virtually no activity compared with npq1 and E122Q single mutants. B, E226Q/npq1 has the same NPQ behavior as npq4 (no activity). C, immunoblotting of thylakoid membranes with anti-PsbS antibodies showing that npq1 double mutants have comparable amounts of PsbS with respect to WT.

In Fig. 1A the NPQ analysis of E122Q and E226Q single mutants is shown with respect to the control genotype npq4 complemented with WT PsbS (WT) and with the double E122Q/E226Q mutant. According to previous reports (11, 13), the amplitude of the major fast reversible (100 s) component of NPQ is approximately half that of WT (3.1 ± 0.1) in the single Glu → Gln mutants (1.9 ± 0.1 and 1.7 ± 0.1 for E122Q and E226Q, respectively) and is completely abolished in the double E122Q/E226Q mutant. Fig. 1B shows the NPQ kinetics of the npq1 and lut2 mutants and the double npq1/lut2 mutant. The lut2 mutant has reduced qE (1.7 ± 0.1) with respect to WT (3.1 ± 0.1), npq1 has an even lower qE (0.6 ± 0.03) and a different kinetic behavior, displaying a more rapid rise and a slower second phase. Immunoblotting with an anti-PsbS antibody shows that all genotypes have comparable amounts of PsbS on a chlorophyll basis with the exception of the E122Q/E226Q double mutant, which has a 40% reduction (Fig. 1C). The double npq1/lut2 mutant shows an extremely reduced level of quenching upon illumination. Moreover, this quenching was not reversible during dark recovery, suggesting that it was due to photoinhibition, in agreement with previous reports of a high photosensitivity in this genotype (10, 24). A lower level of irreversible quenching was observed in npq4, suggesting that the capacity for zeaxanthin synthesis in this genotype partially compensates for lack of qE with respect to npq1/lut2, which lacks both zeaxanthin and qE.

NPQ of lut2 double mutants is compared with that of the single mutants lut2 and E122Q and E226Q in Fig. 2. The amplitude of NPQ is very similar in lut2 and the E122Q and E226Q mutants (Fig. 2, A and B). However, for both the Glu single mutants the initial kinetic behavior was faster than in lut2. The E122Q/lut2 mutant shows a 3-fold reduced activity (0.5 ± 0.03) with respect to both lut2 (1.7 ± 0.1) and E122Q (1.9 ± 0.1), whereas the initial rate was intermediate. Nevertheless, a rapid dark reversible phase was present in this sample, implying that some level of qE activity is compatible with the double mutation. The residual activity in the E226Q/lut2 mutant was 0.5 ± 0.1. Fast recovery from quenching was observed upon transition to the dark, contrasting with the behavior of the npq4, npq1/lut2, and E122Q/E226Q genotypes.

Both of the double mutants E122Q/npq1 and E226Q/npq1 show almost null levels of qE, the NPQ kinetics being hardly distinguishable from that of npq4 (Fig. 3, A and B). It should be noted that the trace levels of NPQ in E122Q/npq1 differ with respect to that of npq4 during the first 2 min of illumination, in which a very small and transitory quenching effect is visible. Long term recovery of fluorescence was incomplete in both genotypes suggesting a similar degree of photoinhibition. The above results show that the npq1 mutation has a stronger inhibitory effect on qE than the lut2 mutation and that the effect of both lutein and zeaxanthin in promoting qE is not dependent on the activity of a specific DCCD-binding site in PsbS.

We further analyzed the effect of zeaxanthin by measuring NPQ on leaves pre-illuminated to induce zeaxanthin accumulation (31). The leaves were illuminated with white light (1260 μEm-2 s-1) for 8 min, followed by a 15-min dark period before NPQ analysis (Fig. 4).

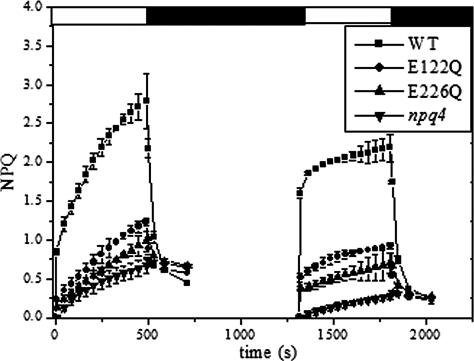

FIGURE 4.

Zeaxanthin pre-loading experiment. Effect of light pretreatment, inducing zeaxanthin synthesis, on the NPQ behavior of plants carrying single DCCD-binding residues on PsbS. Leaves were treated with 1260 μEm-2 s-1 white light for 8 min to induce zeaxanthin synthesis while NPQ was being measured, and the leaves were then dark-adapted for 15 min before a second measurement. NPQ was induced by 1260 μEm-2 s-1 actinic white light.

Pre-illuminated leaves showed a faster initial rate of NPQ with respect to dark-adapted leaves, the half-rise time (t½) being 110 ± 16 s versus 18 ± 3 s, 169 ± 27 s versus 36 ± 11 s, and 191 ± 18 s versus 43 ± 9 s for WT, E122Q, and E226Q, respectively. Therefore, in the presence of zeaxanthin, t½ is 6.1-, 4.7-, and 4.4-fold faster for WT, E122Q, and E226Q, respectively, compared with dark-adapted leaves. The maximum level of NPQ was slightly lower in pre-illuminated leaves, because of residual background quenching from zeaxanthin accumulated during the previous light treatment (26). A similar effect was observed in both E122Q and E226Q mutants and in E122Q/lut2 and E226Q/lut2 mutants (data not shown). All genotypes carrying npq1 or npq4 mutations, and the E122Q/E226Q double mutant did not show the increased rate of qE. Moreover, the second illumination yielded a slower residual quenching rate (data not shown). HPLC analysis showed that light treatment leads to the production of similar amounts of zeaxanthin in all genotypes, part of which was still present at the onset of the NPQ measurement (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Zeaxanthin content measured by HPLC analysis of WT and mutant plants upon 8 min of illumination followed by 15 min of dark adaptation

Data are normalized to 100 chlorophyll a + b molecules.

| WT | E122Q | E226Q | npq4 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumination (8 min) | 0.34 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.02 | 0.41 ± 0.02 | 0.26 ± 0.01 |

| Dark re-adaptation (15 min) | 0.10 ± 0.02 | 0.19 ± 0.01 | 0.12 ± 0.03 | 0.15 ± 0.02 |

Analysis of Direct Binding of Lutein and Zeaxanthin to PsbS in Vitro—An alternative strategy for studying pigment binding to proteins belonging to the Lhc family is to express the apoproteins in E. coli followed by reconstitution of the pigment-protein complex in vitro (32). This procedure, in which Lhc proteins are completely denatured, mixed with purified pigments, followed by step removal of the denaturing agent, has been successfully applied to all Lhca and Lhcb proteins from higher plants (30, 33-35), green algae (36), and red algae (37). An alternative method for reconstitution of PsbS with xanthophylls (15) requires only mild detergent conditions and sonication.

We have attempted reconstitution of WT PsbS by the first approach (30) using barley PsbS apoprotein purified from E. coli and a total pigment extract from thylakoids (Chl a, Chl b, lutein, violaxanthin, neoxanthin, β-carotene, and zeaxanthin). This combination that has been shown to be effective with all Lhc proteins tested so far. Alternatively, pigment mixtures with different xanthophylls with or without chlorophyll a and b were also employed. Because xanthophyll binding to PsbS has been proposed to be promoted by low pH (13), acidic conditions were used, pH 5.5, in addition to the usual basic conditions, pH 7.8. Table 2 lists the various conditions tested.

TABLE 2.

Protocols and conditions tested in refolding experiments with recombinant PsbS

| Procedure | rPsbS presence | Pigment mixture | pH |

|---|---|---|---|

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Total pigments + zeaxanthin | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Chlorophyll a + b + zeaxanthin | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Chlorophyll a + b + zeaxanthin | 5.5 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Chlorophyll a + zeaxanthin | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | – | Chlorophyll a + zeaxanthin | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Zeaxanthin | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Lutein | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Zeaxanthin + lutein | 7.8 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Zeaxanthin | 5.5 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | – | Zeaxanthin | 5.5 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Lutein | 5.5 |

| Giuffra et al. (30) | + | Zeaxanthin + lutein | 5.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | + | Zeaxanthin | 7.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | – | Zeaxanthin | 7.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | + | Lutein | 7.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | – | Lutein | 7.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | + | Zeaxanthin + lutein | 7.5 |

| Aspinall-O'Dea et al. (15) | – | Violaxanthin | 7.5 |

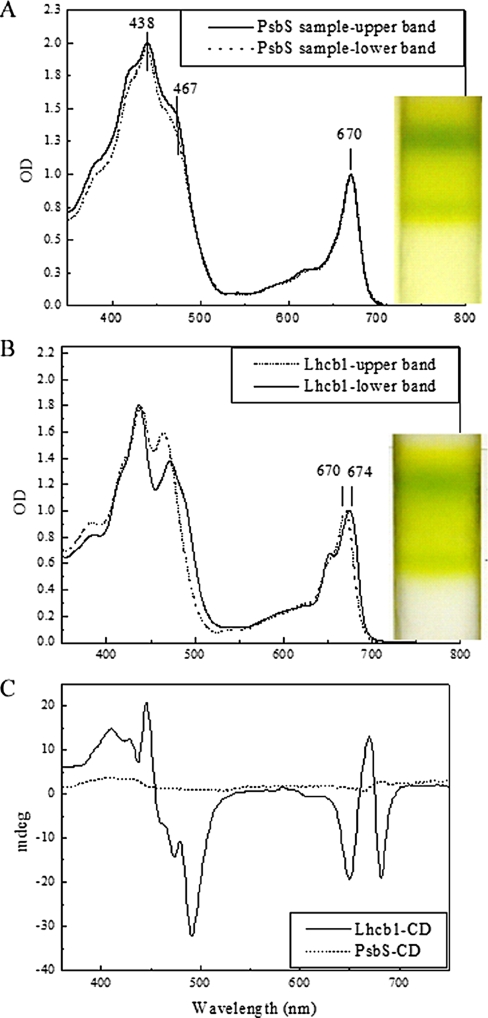

Following in vitro refolding, the protein/pigment mixture was fractionated by sucrose gradient ultracentrifugation. Positive controls of this experiment used Lhcb1 apoprotein instead of PsbS, whereas in negative controls pigments were loaded without addition of either PsbS or Lhcb1. In all cases, two green/yellow bands were obtained in the upper part of the sucrose gradient, the color depending on the initial pigment composition. Analysis by SDS-PAGE showed that PsbS protein was present in both bands and also in the colorless fraction at higher density (about 8% of the total protein). In the case of Lhcb1, protein was present in the two colored bands but not in the lower part of the gradient. Bands were harvested and examined by absorption and CD spectroscopy. The absorption spectra of the two gradient bands in samples loaded with PsbS and reconstituted with total pigments were essentially identical, with main peaks at 670 and 438 nm for Chl a and at 467 nm for Chl b (Fig. 5A), as clearly shown by second derivative analysis (not shown). No optical activity was revealed by CD spectroscopy (Fig. 5C). Similar results were obtained for the bands from the negative control without protein as well as in the upper band of the Lhcb1 sample. The lowest band from the gradient loaded with reconstituted Lhcb1 instead showed an absorption peak at 674 nm and a high amplitude CD spectrum (Fig. 5, B and C). We conclude that the procedure of in vitro renaturation of recombinant proteins, although effective with Lhcb1 (this work) and many other Lhc proteins (30, 33-35), is unable to produce pigment-protein complexes when applied to PsbS.

FIGURE 5.

Spectroscopic characterization of in vitro refolded samples. Spectral properties of fractions obtained from in vitro reconstitution of PsbS protein following the protocol for Lhc proteins (30). A, absorption spectra of the two gradient bands from samples reconstituted with total pigments and zeaxanthin at pH 7.8. B, absorption spectra of Lhcb1 samples reconstituted with total pigments. C, CD spectra of lower bands from gradients shown in A and B.

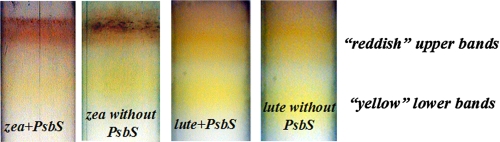

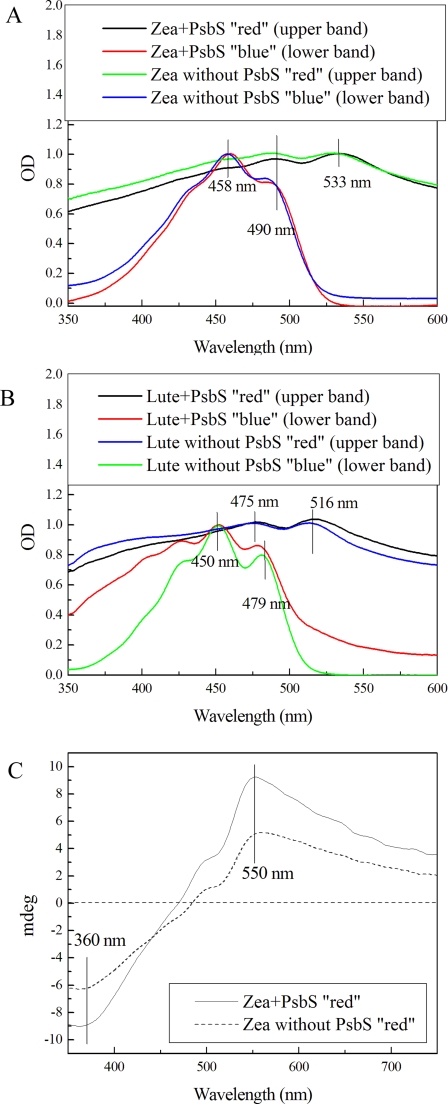

We then attempted reconstitution of PsbS using the alternative procedure described by Ref. 15 using either zeaxanthin and/or lutein or violaxanthin as xanthophyll ligand. Again, a xanthophyll-only sample without apoprotein was used as a negative control, although a positive control was not available because Lhcb1 and other Lhc proteins did not form pigment-protein complexes without chlorophyll a and b. After reconstitution, the PsbS-containing mixture was separated on a sucrose gradient yielding two bands in the case of reconstitution with zeaxanthin and with lutein, both containing PsbS when assayed by SDS-PAGE. The lower band was yellow-orange and the upper band was reddish (Fig. 6). Spectroscopic analysis showed that the two fractions had different properties; the lower band from the reconstitution assay with zeaxanthin was characterized by absorption bands at 458 and 490 nm and no optical activity, whereas the upper band displayed a very broad absorption spectrum with maxima at 490 and 533 nm and a strong CD signal, with a positive term at 550 nm and a negative component at 360 nm (Fig. 7, A and C). The absorption spectra of lutein were similar to those of the corresponding zeaxanthin samples except for some variation in the wavelengths of the absorption maxima. The lower sucrose band displayed peaks at 450 and 479 nm, whereas the upper sucrose band showed absorption maxima at 475 and 516 nm (Fig. 7B). It should be noted that the gradient loaded with the negative control experiment (i.e. with xanthophylls but without PsbS recombinant protein) exhibited very similar spectroscopic characteristics (Fig. 7), implying that PsbS was not involved in the formation of this xanthophyll form with modified spectral properties. Hence, for both zeaxanthin and lutein, the absorption maxima of the upper sucrose band are observed at higher wavelengths compared with those of the lower sucrose band.

FIGURE 6.

Pictures of sucrose gradient bands. Fractions are obtained upon ultracentrifugation of samples reconstituted with zeaxanthin (zea) or lutein (lute), following the protocol described in Ref. 15.

FIGURE 7.

Spectral properties of sucrose gradient fractions from Fig. 6. A, absorption spectra of bands from zeaxanthin(Zea)-containing samples. B, absorption spectra of lutein (Lute)-containing samples. C, CD spectra of zeaxanthin samples (upper bands) with or without PsbS shown in Fig. 6. The two samples had the same optical activity upon normalization to absorption at 533 nm.

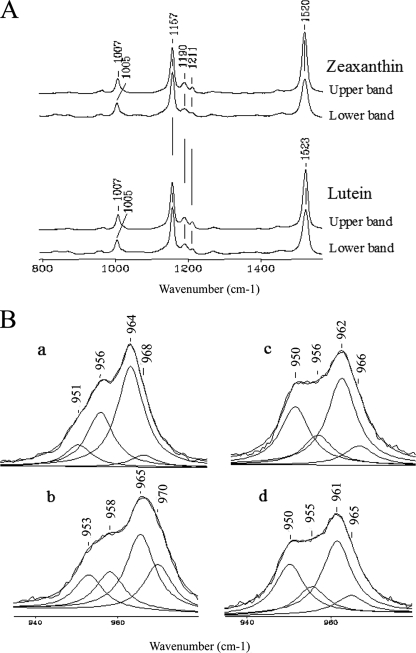

Characterization of Upper Sucrose Gradient Bands Containing the Spectrally Shifted Xanthophyll Fractions—As noted above, two bands were observed on sucrose gradients for reconstitution experiments with zeaxanthin and lutein (Fig. 6) distinguished by different spectral characteristics. To elucidate the basis for this variation in the xanthophyll optical properties, sucrose gradient bands from samples without PsbS were harvested and studied by resonance Raman spectroscopy. The RR spectra (Fig. 8) are very similar to those reported previously (14, 38). However, as the C-H out-of-plane wagging vibrations have been considered to be an important reporter of zeaxanthin binding to PsbS (14, 15), a curve-fitting analysis of the 930-990 cm-1 frequency region has been carried out (Fig. 8B). The spectra of the lower sucrose gradient bands of zeaxanthin and lutein are very similar with bands at 950, 956, 962, and 966 cm-1. The RR frequencies of the C-H wagging vibrations of the upper sucrose gradient band of zeaxanthin are 951, 956, 964, and 968 cm-1. The relative intensity and frequencies of these bands are very similar to those of a previous report in which they were attributed to an interaction between zeaxanthin and PsbS (15). The corresponding RR lutein spectrum is similar to that of zeaxanthin, although the frequencies are slightly higher (953, 958, 965, and 970 cm-1). It is noted that although an excitation of 514.5 nm was used for the spectra reported in Fig. 8, which is in resonance with the absorption spectra of both the upper and lower gradient fractions, the RR spectra for excitation at 441.6 and 530.9 nm were identical to those of Fig. 8.

FIGURE 8.

Resonance Raman spectra. Resonance Raman spectra of the upper and lower gradient bands of zeaxanthin and lutein without PsbS for excitation at 514.5 nm (A). B shows a curve-fitting analysis of the C-H out-of-plane wagging vibrations of the spectra in the 900-1000 cm-1 region: panel a, zeaxanthin, upper band; panel b, lutein, upper band; panel c, zeaxanthin, lower band; panel d, lutein, lower band. Experimental conditions: 2.2 cm-1 spectral resolution and 30 milliwatts laser power at the sample; zeaxanthin, upper band, 600 s integration time; zeaxanthin, lower band, 3600 s integration time; lutein, upper band, 1200 s integration time; lutein, lower band, 2400-s integration time.

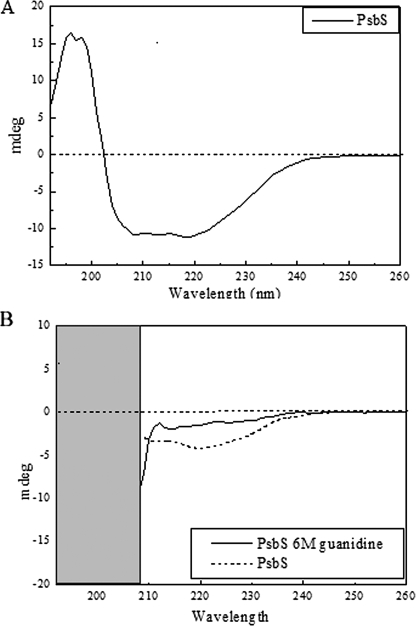

In Vitro Refolding of Recombinant PsbS without Pigments—The above experiments indicate the possibility that PsbS behaves differently with respect to the other members of the Lhc protein family and with respect to pigment binding. This is understandable on the basis of the primary sequence analysis showing that the specific residues involved in chlorophyll binding are not conserved except in the case of Chl A1 and A4 (3). Consequently, this raises the possibility that PsbS is able to refold in vitro in the absence of pigments. To this end, the denatured PsbS protein (in 2% LDS) was submitted to step renaturation by precipitation of LDS with KCl and addition of 1% n-octyl β-d-glucopyranoside followed by ultracentrifugation on a sucrose gradient containing 0.1% n-dodecyl β-d-maltoside and phosphate buffer. Migration of the protein was monitored by UV absorption and SDS-PAGE of gradient fractions. The conformation of the PsbS protein was studied by CD spectroscopy in the UV region (39). This is reported in Fig. 9, where CD spectra of PsbS without pigments are shown before and after addition of the denaturing agent guanidine HCl. Information on the secondary structure of the protein was obtained by analyzing the spectra using the K2d software yielding 38% α-helix, 19% β-sheet, and 43% random coil. These values closely follow those expected from models based on primary sequence analysis (4) and are consistent with the LHCII structure (40, 41). Upon denaturation, the CD spectrum was typical of a full random-coil state, implying the recombinant protein refolded without pigments has an ordered secondary structure (Fig. 9).

FIGURE 9.

Conformational analysis of recombinant PsbS refolded in vitro. A, CD spectrum of recombinant PsbS refolded without pigments. B, spectra of the same protein sample after and before addition of denaturing agent guanidine HCl; guanidine absorption below 210 nm disturbs optical measurements.

DISCUSSION

In Vivo Analysis of Xanthophyll Binding to PsbS and Interaction between DCCD-binding Sites and Xanthophyll-binding Sites—Although NPQ and, in particular, its rapidly reversible component qE has been extensively studied for many years, its mechanism is still unclear. The kinetics of qE formation have been found to fit a hyperbolic second-order reaction model in which the interaction between two fluorescent molecules yields the quencher product (42). Earlier work suggested that quenching is produced by Chl-Chl pairs formed within LHCII through conformational changes induced by protonation events on the luminal side of the thylakoid membrane (19, 43, 44). More recently, chlorophyll quenching was proposed to be the result of the formation of a Chl-/zeaxanthin + radical pair (45). Furthermore, the identity of the gene product(s) that bind chromophores involved in quenching is also still ill-defined. Chlorophyll quenching requires that Chl a and the quencher molecule are located closely to each other, so that activation by a protonation event can establish a functional interaction through induction of a conformational change (20). This hypothesis is supported by the observation that a quenching event can be obtained in isolated monomeric Lhc proteins (46). Obvious candidates for chromophores required for the quenching event(s) are Lhcb proteins that can be easily isolated with bound Chl a, lutein, and zeaxanthin (47) and can exchange violaxanthin with zeaxanthin upon light exposure (48). PsbS is a special case because it binds DCCD (3) and is essential for qE (4). In this protein a clear relation exists between the activity of two DCCD-binding glutamate residues and quenching activity in vivo; inactivation of both glutamic acid residues abolishes qE, whereas each single mutation leads to reduction of qE by approximately 50% (13). The inhibition of lutein and zeaxanthin synthesis by the mutations closely follows the effect of mutations on DCCD-binding residues; the npq1/lut2 double mutant has no qE (10), although lack of either lutein (lut2) or zeaxanthin (npq1) reduces its amplitude (6, 7), as is the case with plants with zeaxanthin alone (7, 9). Because PsbS is a 2-fold symmetrical protein with two central crossing transmembrane helices, it is tempting to suggest that xanthophylls might bind to putative sites structurally homologous to L1 and L2 in LHCII (40, 41), whereas the reduced qE amplitude in plants lacking zeaxanthin or lutein (7, 9) is consistent with a strong selectivity of the binding sites for zeaxanthin or lutein, respectively. This model implies that the qE phenotypes of lut2, npq1, and npq1/lut2 depend on the selectivity of the two putative L1- and L2-binding sites in PsbS. If one assumes that L1 (Glu-226) is specific for lutein and L2 (Glu-122) for zeaxanthin, analogous to the case of LHCII (49), the combination of the npq1 mutation with PsbS E226Q, inactivating the putative L1 (lutein)-binding site, is expected to yield a null qE phenotype. The same phenotype is expected for the combination of the lut2 and PsbS E122Q mutations, whereas E122Q/npq1 and E226Q/lut2 are expected to yield about 50% qE with respect to WT, because these would have both an active DCCD-binding site and the appropriate xanthophyll bound to it. Table 3 compares the observed results with those expected.

TABLE 3.

Relative amplitude of qE in genotypes obtained by crossing lut2/npq4 and npq1/npq4 xanthophyll mutants, lacking lutein and zeaxanthin, respectively, with PsbS E122Q and PsbS E226Q mutations, inactivating DCCD-binding sites essential for qE activity

Expected values (exp) are proposed on the assumption of two xanthophyll-binding sites in PsbS as follows: one selective for zeaxanthin (Glu-122 or L2) and one for lutein (Glu-226 or L1). Obs values represent observed qE activity (NPQ relaxed within 100 s from light-dark transition) expressed in % with respect to WT. It is arbitrarily assumed that putative binding site L1 (Glu-226) is selective for lutein and L2 (Glu-122) for zeaxanthin, according to the observed affinity in LHCII (25, 49, 70).

| Crossed with | E122Q exp | E122Q obs | E226Q exp | E226Q obs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT (single Glu mutants) | 50 | 64 ± 2.6 | 50 | 56 ± 2.5 |

| npq1 | 20 | 1 ± 0.6 | 0 | 0.4 ± 0.1 |

| lut2 | 0 | 16 ± 1.2 | 50 | 17 ± 4.6 |

Because single Glu mutants have about 50% qE activity, if protonation of DCCD-binding sites activates xanthophyll binding to PsbS, then each double mutant is expected to show about 50% activity in the presence of either zeaxanthin or lutein. This is not what happens; all double mutants have qE activity well below 50% of WT. We conclude that a single PsbS protonation event is efficient in eliciting quenching when both lutein and zeaxanthin are available but is insufficient without zeaxanthin or, to a lesser extent, without lutein. Clearly, the experimental results are not consistent with the hypothesis that the phenotype of xanthophyll biosynthesis mutants depends on xanthophyll binding to two sites of PsbS, selective for either lutein or zeaxanthin.

Cooperativity between Zeaxanthin and Activation of Each DCCD-binding Site—Early models of NPQ induction had proposed a cooperative interaction between pH activation and zeaxanthin (19), subsequently confirmed by several experiments, leading to the proposal that zeaxanthin is an allosteric activator of qE in leaves and isolated chloroplasts (20). Cooperativity is demonstrated by the higher initial rate of quenching in the presence of zeaxanthin. Pre-illumination of leaves leads to accumulation of zeaxanthin (Table 1) and increase of the initial NPQ rate during subsequent illumination (Fig. 4). The increased initial rate for both mutants implies that cooperativity can be provided by either Glu-122 or Glu-226. This result implies that if zeaxanthin acts by binding to PsbS, its binding is not selective for the Glu-122 and Glu-226 sites; this is in clear contrast with the phenotype of the lut2/npq2 mutant, where qE is significantly reduced despite that zeaxanthin is constitutively available. We conclude that the cooperative effect is not due to zeaxanthin binding to PsbS.

Analysis of Direct Binding of Lutein and Zeaxanthin to PsbS in Vitro—PsbS belongs to the Lhc protein family (50), which includes many members from higher plants, green algae, red algae, and chromophyta (36, 51). These proteins, with antenna function, cooperatively bind chlorophyll and xanthophyll chromophores, which are both needed for the assembly of pigment-protein complexes in vivo and in vitro (32). Chlorophylls are bound by specific residues (34, 40), whereas xanthophylls interact with chlorophyll ligands as shown by their loss upon mutation at Chl-binding sites (35, 52, 53). In this respect PsbS is peculiar among Lhc proteins in that out of eight amino acid-binding residues conserved among all Lhc proteins, only two are conserved. Furthermore, the two conserved Chl-binding residues, namely the ligands of Chl A1 and Chl A4, stabilize interactions between trans-membrane helices by formation of ion pairs, thus raising the possibility that structural stabilization is their only conserved function in PsbS.

Pigment-protein assembly in Lhc proteins can be obtained in vitro by step renaturation of Lhc apoproteins in the presence of pigments (32), a procedure that was proven to be efficient for as many as 20 Lhc gene products from different organisms (21, 35, 53-55). In this work we have attempted reconstitution of PsbS using a large variety of conditions, including different chlorophyll and xanthophyll composition and pH values without obtaining stable pigment proteins. In some cases we obtained pigmented bands in the sucrose gradients. However, the absorption spectra of the pigments co-migrating with PsbS were not consistent with spectra previously reported to be characteristic of pigment-protein interaction, namely red-shifted maxima were not observed and no optical activity was detected by CD spectroscopy. In fact, a red shift in the absorption spectrum of Chl and the appearance of a strong CD signal in the visible region are typical characteristics of all Lhc proteins when pigments are coordinated to the protein moiety, whereas free chlorophyll or carotenoid solution have very weak optical activity. This has been confirmed in this work when Lhcb1 was used instead of PsbS in the reconstitution experiments (Fig. 5).

A previous study of zeaxanthin mixed with PsbS in mild detergent conditions reported observation of an absorption maximum at ∼530 nm (15), reminiscent of the 535 nm spectral signal detected in leaves upon induction of NPQ in the presence of PsbS (4) and synthesis of zeaxanthin (56, 57). When applying this procedure, we obtained sucrose gradient bands characterized by absorption maxima at ∼530 nm and strong optical activity in experiments with zeaxanthin and PsbS. However, the following three observations cast doubts on the hypothesis that these xanthophyll forms depend on the formation of a PsbS-zeaxanthin complex: (i) lutein, a xanthophyll that is not accumulated during the induction of NPQ, was as effective as zeaxanthin in producing a red-shifted xanthophyll form with absorption maxima at ∼16 nm; (ii) the distribution of PsbS protein and of xanthophyll characterized by 530 nm absorption maxima among sucrose gradient fractions is not the same; and (iii) negative control experiments, performed without PsbS, did not prevent the formation of the xanthophyll forms displaying absorption maxima at ∼530 nm.

Origin of the Different Absorption Spectral Characteristics of Lutein and Zeaxanthin—The observation in this work of zeaxanthin and lutein forms displaying an absorption maximum at ∼530 and 516 nm for conditions that preclude formation of a xanthophyll protein complex clearly undermines the assignment of such forms to xanthophyll-bound PsbS (15). In this regard, it is noteworthy that an absorption spectrum exhibiting a maximum at ∼530 nm has been reported for zeaxanthin upon the formation of J-type aggregates induced by addition of water to zeaxanthin solution in organic solvents (58). We have obtained such a xanthophyll form for both zeaxanthin and lutein but not for violaxanthin. This suggests that both fractions we obtained from sucrose gradients upon sonication represent different states of aggregation of these hydrophobic molecules in a water-detergent environment. It is important to note that the relative intensity and frequency of the C-H wagging vibrations of the upper gradient bands, characterized by the 530 nm absorption maximum (Fig. 8B), which were considered to be a signature of zeaxanthin binding to PsbS, are almost identical to those described in a previous work (15). This suggests that the putative PsbS-zeaxanthin complex was, instead, the result of co-migrating apo-PsbS and J-type aggregated zeaxanthin.

PsbS Refolds in the Absence of Pigments—Pigment binding to PsbS is controversial (3, 15, 23) and has not been verified by our experiments. An alternative possibility is that PsbS is stable in the membranes without pigment. We found that the in vitro reconstitution procedure, performed without pigments, always yielded recombinant PsbS displaying secondary structure that was disrupted by denaturing agents. This suggests that PsbS may well assume its conformation in the absence of bound pigments. Lhc proteins are stabilized by the interaction with their chlorophyll and xanthophyll chromophores. For example, LHCII is de-stabilized in mutants lacking Chl b and upon accumulation of zeaxanthin; CP26 is also strongly decreased in the absence of neoxanthin (26). This is not the case of PsbS that is accumulated in etiolated leaves (59), in plants lacking Chl b (3, 4), and in plants mutated in xanthophyll composition (Ref. 60 and this work) suggesting it does not need xanthophyll for stabilization.

Conclusions—In this work we have investigated the hypothesis that the xanthophylls lutein and zeaxanthin, which are indispensable for the full expression of qE, bind to PsbS. If xanthophyll binding to PsbS is an integral part of the NPQ mechanism, which exhibits specific requirements for xanthophylls, the xanthophyll binding capacity of PsbS should clearly reflect such characteristics. This is not the case as experimental results are not consistent with the model of lutein/zeaxanthin binding to PsbS. In the presence of both protonatable glutamate residues in PsbS, the level of quenching obtained is reduced if only lutein or zeaxanthin are available (6-9). An additional characteristic of NPQ is the positive allosteric effect induced by zeaxanthin synthesis. We show that this effect is not provided by a specific binding site on PsbS because it is present in each of the two single Glu → Gln mutants (Fig. 4). If one considers the “selective” or “nonselective” version of the two binding sites model in terms of the body of experimental evidence currently available, both presented here and published previously, various data are in contrast with the selective version. In this context, selective refers to the capacity of each of the two putative xanthophyll-binding sites in PsbS to bind only lutein or zeaxanthin. Such selectivity is suggested by the following two observations: (i) the similarity between the effect of npq1 and lut2 mutations compared with E122Q and E226Q mutations; (ii) the reduced amplitude of qE in the presence of zeaxanthin only (lut2/npq2 and aba1/lut2 mutants) with respect to the case in which both lutein and zeaxanthin are available (npq2). Nevertheless, the selective model cannot explain some of the phenotypes described above and as follows. (a) The E122Q/lut2 and E226Q/lut2 mutants are expected to show qE = 0 or qE = lut2 =∼50% (depending on which site is binding lutein), whereas they have a similar level of qE = 16-17% with respect to WT. (b) The E122Q/npq1 and E226Q/npq1 mutants are expected to show qE = 0 or qE = npq1 =∼20% (depending on which site is binding zeaxanthin), although they have a similar level of qE = 0. (c) Either E122Q or E226Q mutant is expected to have qE levels equal to npq1 =∼20% (and a rapidly saturating kinetic behavior), although they have both approximately 50% and two-phase kinetics similar to WT. Hence, we conclude that the updated selective version of the two binding sites model can be ruled out.

Now we consider the nonselective version of the two binding sites model; in this case lutein is expected to bind to both binding sites in the dark and be substituted by zeaxanthin during light exposure. The nonselectivity of the putative xanthophyll-binding sites in PsbS is suggested by (i) the slow initial phase of NPQ in lut2 and (ii) the fast initial rise, but low maximal qE, in the npq1 mutant. However, also in this case there are evident contradictions between the observed and expected phenotypes as indicated in the following. (a) The E122Q/npq1 and E226Q/npq1 mutants are expected to exhibit qE = (npq1)/2 =∼10%, while they have qE = 0. (b) The npq2 and npq2/lut2 (and aba1/lut2) mutants are expected to bind zeaxanthin to both sites and therefore should exhibit fast and maximal rate of qE. However, the npq2/lut2 and aba1/lut2 mutants have been reported to show about 50% qE with respect to WT (8, 9).

The experimental results of plants carrying PsbS with a single DCCD binding glutamate are not consistent with the model of lutein/zeaxanthin binding to PsbS. We have confirmed that both xanthophylls are essential to the full expression of qE by the inability of partially inactivated PsbS to trigger the expected 50% activity when a DCCD-binding site and the appropriate xanthophyll are present. In the light of the above conclusions, one must consider alternatives to PsbS that may be able to bind xanthophylls and constitute the quenching site during NPQ. Lhcb proteins are suitable candidates in that they bind many Chl a, Chl b, and xanthophyll molecules in close proximity to each other (40, 41), which might well establish strong interactions upon conformational changes and induce a concentration type quenching (19) or energy transfer to a quenching species (45). An example of Chl-Chl interaction affecting the fluorescence properties of Lhc-type proteins has been described recently (61); displacement of Chl A5 by 2 Å triggers a switch from red-shifted to non-red-shifted forms of Lhca3 and Lhca4. Moreover, it has been shown that Lhcb proteins, mainly Lhcb6 and Lhcb5, undergo exchange of the xanthophylls bound to site L2 from violaxanthin to zeaxanthin (48). Zeaxanthin binding to site L2 induces a conformational change from long to short fluorescence lifetime state (49, 62, 63), implying a fluorescence quenching that is amplified by protein-protein interactions within the lipid phase (62). If xanthophylls bind to Lhcb proteins, then the role of PsbS appears to be that of a pH-sensitive molecular switch detecting luminal pH and controlling the transition of Lhc proteins between unquenched and quenched conformations. Two principal observations support the “PsbS trigger model” model as follows.

PsbS has the ability to assume a folded conformation in vitro without pigments. This is shown in vivo by the stability of PsbS in etiolated leaves (59), in genotypes lacking Chl b (3) and in carotenoid biosynthesis mutants (60). Pigment-binding Lhc proteins are de-stabilized in the absence of their chromophores, either Chl b (64, 65), neoxanthin (66), or violaxanthin plus lutein (9), whereas the PsbS level is essentially unaffected, suggesting it does not require chromophores for its stabilization.

The initial rate of quenching in leaves depends on the presence of zeaxanthin. A number of findings reported in this study indicate that xanthophyll does not bind to PsbS, and yet the initial rate of quenching is faster in the presence of zeaxanthin in all genotypes. Nevertheless, the increase in the half-rise time of NPQ is higher in WT than in PsbS single Glu plants. These results can be explained on the basis of the presence of distinct conformations of Lhc proteins with different fluorescence lifetimes (62, 67), whereas the activation energy for the transition from the unquenched to the quenched form of Lhc proteins is decreased by the binding of zeaxanthin to one or more Lhc proteins (42, 62). We propose that ΔG, which results from the protonation of two DCCD-binding glutamates in WT PsbS, is sufficient to induce a conformational change in a neighboring Lhc protein. However, a single protonation event, still possible in each of the Glu → Gln mutants, can induce a conformational change more slowly in the presence of both lutein and zeaxanthin (Figs. 1A and 4), although this process is further slowed down or blocked when either lutein or zeaxanthin is missing (Figs. 2 and 3). Conformational changes are known to be induced in Lhc proteins by violaxanthin > zeaxanthin exchange in site L2 (48, 49), thus shifting the equilibrium between long (Unquenched) fluorescence lifetimes to short (Quenched) fluorescence lifetimes (62, 63, 67), implying that the activation energy for the U > Q transition is decreased.

We conclude that the two xanthophyll-binding sites model, either in its selective or its original nonselective version (13), cannot explain the NPQ phenotypes of the double mutants that carry a single Glu → Gln mutation and lack either lutein or zeaxanthin. However, this conclusion supports the alternative PsbS trigger model (20, 21).

The presence of distinct conformations of Lhc proteins with long and short fluorescence lifetimes and the lower activation energy for the U > Q transition upon zeaxanthin binding make this model the simplest explanation for NPQ. It does not need to invoke new pigment-binding units besides the Lhcb proteins, which are well characterized with respect to their chromophore complement and capacity to bind zeaxanthin. One may ask which Lhcb subunit, among the Lhcb1-6 described in higher plants (50), is the primary quenching unit triggered by PsbS protonation. Reverse genetic has been applied to Lhcb proteins (31, 68) without finding a deletion capable of drastically affecting NPQ except Lhcb6, which nevertheless showed a partial phenotype. Thus, it cannot be excluded that quenching is a general property of Lhcb proteins or of a subset of them. This latter hypothesis is consistent with the recent finding that the three monomeric Lhcb proteins CP29, CP26, and CP24, but not the trimeric LHCII, exhibit the formation of charge transfer state (69) proposed as the quenching species responsible for qE in intact chloroplasts (45).

Acknowledgments

We thank K. K. Niyogi (University of California) for helpful discussions and for kindly providing the A. thaliana npq4 plants complemented with WT and mutant psbS.

The work was supported by the Italian Ministry of Research and University Special Fund for Research FISR 2002 IDROBIO. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: NPQ, nonphotochemical quenching; Chl, chlorophyll; DCCD, dicyclohexylcarbodiimide; Lhcb, light-harvesting complex of photosystem II; LHCII, major light-harvesting complex of photosystem II; LDS, lithium dodecyl sulfate; Lute, lutein; qE, energy-dependent quenching; WT, wild type; HPLC, high pressure liquid chromatography; Tricine, N-[2-hydroxy-1,1-bis(hydroxymethyl)ethyl]glycine; Mes, 4-morpholineethanesulfonic acid; μE, microeinstein; RR, resonance Raman.

L. Dall'Osto, unpublished results.

References

- 1.Briantais, J. M. (1966) C.R. Acad. Sci. Hebd. Seances Acad. Sci. D. 263 1899-1902 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ruban, A. V., Walters, R. G., and Horton, P. (1992) FEBS Lett. 309 175-179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dominici, P., Caffarri, S., Armenante, F., Ceoldo, S., Crimi, M., and Bassi, R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 22750-22758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li, X. P., Bjorkman, O., Shih, C., Grossman, A. R., Rosenquist, M., Jansson, S., and Niyogi, K. K. (2000) Nature 403 391-395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, X. P., Gilmore, A. M., and Niyogi, K. K. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 33590-33597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Niyogi, K. K., Grossman, A. R., and Björkman, O. (1998) Plant Cell 10 1121-1134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pogson, B. J., Niyogi, K. K., Björkman, O., and DellaPenna, D. (1998) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 95 13324-13329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lokstein, H., Tian, L., Polle, J. E., and DellaPenna, D. (2002) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1553 309-319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Havaux, M., Dall'Osto, L., Cuine, S., Giuliano, G., and Bassi, R. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 13878-13888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Niyogi, K. K., Shih, C., Soon, C. W., Pogson, B. J., DellaPenna, D., and Bjorkman, O. (2001) Photosynth. Res. 67 139-145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li, X. P., Phippard, A., Pasari, J., and Niyogi, K. K. (2002) Funct. Plant Biol. 29 1131-1139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Holt, N. E., Fleming, G. R., and Niyogi, K. K. (2004) Biochemistry 43 8281-8289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li, X. P., Gilmore, A. M., Caffarri, S., Bassi, R., Golan, T., Kramer, D., and Niyogi, K. K. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279 22866-22874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ruban, A. V., Pascal, A. A., Robert, B., and Horton, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 7785-7789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aspinall-O'Dea, M., Wentworth, M., Pascal, A., Robert, B., Ruban, A., and Horton, P. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 99 16331-16335 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Elrad, D., Niyogi, K. K., and Grossman, A. R. (2002) Plant Cell 14 1801-1816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Briantais, J.-M., Dacosta, J., Goulas, Y., Ducruet, J.-M., and Moya, I. (1996) Photosynth. Res. 48 189-196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kovacs, L., Damkjaer, J., Kereiche, S., Ilioaia, C., Ruban, A. V., Boekema, E. J., Jansson, S., and Horton, P. (2006) Plant Cell 18 3106-3120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Horton, P., Ruban, A. V., Rees, D., Pascal, A. A., Noctor, G., and Young, A. J. (1991) FEBS Lett. 292 1-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Horton, P., Ruban, A. V., and Wentworth, M. (2000) Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 355 1361-1370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bassi, R., and Caffarri, S. (2000) Photosynth. Res. 64 243-256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morosinotto, T., Caffarri, S., Dall'Osto, L., and Bassi, R. (2003) Physiol. Plant. 119 347-354 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Funk, C., Schröder, W. P., Napiwotzki, A., Tjus, S. E., Renger, G., and Andersson, B. (1995) Biochemistry 34 11133-11141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dall'Osto, L., Lico, C., Alric, J., Giuliano, G., Havaux, M., and Bassi, R. (2006) BMC Plant Biol. 6 32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hobe, S., Niemeier, H., Bender, A., and Paulsen, H. (2000) Eur. J. Biochem. 267 616-624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dall'Osto, L., Caffarri, S., and Bassi, R. (2005) Plant Cell 17 1217-1232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casazza, A. P., Tarantino, D., and Soave, C. (2001) Photosynth. Res. 68 175-180 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bassi, R., Rigoni, F., Barbato, R., and Giacometti, G. M. (1988) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 936 29-38 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schagger, H., and von Jagow, G. (1987) Anal. Biochem. 166 368-379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Giuffra, E., Cugini, D., Croce, R., and Bassi, R. (1996) Eur. J. Biochem. 238 112-120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Andersson, J., Walters, R. G., Horton, P., and Jansson, S. (2001) Plant Cell 13 1193-1204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Plumley, F. G., and Schmidt, G. W. (1987) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 84 146-150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paulsen, H., and Hobe, S. (1992) Eur. J. Biochem. 205 71-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bassi, R., Croce, R., Cugini, D., and Sandona, D. (1999) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 96 10056-10061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morosinotto, T., Castelletti, S., Breton, J., Bassi, R., and Croce, R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 36253-36261 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cammarata, K. V., Plumley, F. G., and Schmidt, G. W. (1992) Photosynth. Res. 33 235-250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Grabowski, B., Cunningham, F. X., Jr., and Gantt, E. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 98 2911-2916 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schulz, H., Baranska, M., and Baranski, R. (2005) Biopolymers 77 212-221 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Johnson, W. C., Jr. (1990) Proteins 7 205-214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuhlbrandt, W., Wang, D. N., and Fujiyoshi, Y. (1994) Nature 367 614-621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Liu, Z., Yan, H., Wang, K., Kuang, T., Zhang, J., Gui, L., An, X., and Chang, W. (2004) Nature 428 287-292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ruban, A. V., and Horton, P. (1999) Plant Physiol. 119 531-542 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Crofts, A. R., and Yerkes, C. T. (1994) FEBS Lett. 352 265-270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pesaresi, P., Sandona, D., Giuffra, E., and Bassi, R. (1997) FEBS Lett. 402 151-156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Holt, N. E., Zigmantas, D., Valkunas, L., Li, X. P., Niyogi, K. K., and Fleming, G. R. (2005) Science 307 433-436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruban, A. V., Young, A., and Horton, P. (1994) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1186 123-127 [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bassi, R., Pineau, B., Dainese, P., and Marquardt, J. (1993) Eur. J. Biochem. 212 297-303 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Morosinotto, T., Baronio, R., and Bassi, R. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277 36913-36920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Formaggio, E., Cinque, G., and Bassi, R. (2001) J. Mol. Biol. 314 1157-1166 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jansson, S. (1999) Trends Plant Sci. 4 236-240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meyer, M., and Wilhelm, C. (1993) Z. Naturforsch. Sect. C Biosci. 48 461-473 [Google Scholar]

- 52.Croce, R., Remelli, R., Varotto, C., Breton, J., and Bassi, R. (1999) FEBS Lett. 456 1-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gastaldelli, M., Canino, G., Croce, R., and Bassi, R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 19190-19198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Croce, R., Muller, M. G., Caffarri, S., Bassi, R., and Holzwarth, A. R. (2003) Biophys. J. 84 2517-2532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Castelletti, S., Morosinotto, T., Robert, B., Caffarri, S., Bassi, R., and Croce, R. (2003) Biochemistry 42 4226-4234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruban, A. V., Young, A. J., and Horton, P. (1993) Plant Physiol. 102 741-750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bilger, W., and Björkman, O. (1994) Planta 193 238-246 [Google Scholar]

- 58.Billsten, H. H., Sundstrom, V., and Polivka, T. (2005) J. Phys. Chem. A 109 1521-1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Funk, C., Adamska, I., Green, B. R., Andersson, B., and Renger, G. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270 30141-30147 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Dall'Osto, L., Fiore, A., Cazzaniga, S., Giuliano, G., and Bassi, R. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Morosinotto, T., Mozzo, M., Bassi, R., and Croce, R. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280 20612-20619 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Moya, I., Silvestri, M., Vallon, O., Cinque, G., and Bassi, R. (2001) Biochemistry 40 12552-12561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Polivka, T., Zigmantas, D., Sundstrom, V., Formaggio, E., Cinque, G., and Bassi, R. (2002) Biochemistry 41 439-450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Bassi, R., Hoyer-Hansen, G., Barbato, R., Giacometti, G. M., and Simpson, D. J. (1987) J. Biol. Chem. 262 13333-13341 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Preiss, S., and Thornber, J. P. (1995) Plant Physiol. 107 709-717 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dall'Osto, L., Cazzaniga, S., North, H., Marion-Poll, A., and Bassi, R. (2007) Plant Cell 19 1048-1064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Crimi, M., Dorra, D., Bosinger, C. S., Giuffra, E., Holzwarth, A. R., and Bassi, R. (2001) Eur. J. Biochem. 268 260-267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ganeteg, U., Kulheim, C., Andersson, J., and Jansson, S. (2004) Plant Physiol. 134 502-509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Avenson, T. J., Ahn, T. K., Zigmantas, D., Niyogi, K. K., Li, Z., Ballottari, M., Bassi, R., and Fleming, G. R. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283 3550-3558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Croce, R., Weiss, S., and Bassi, R. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274 29613-29623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]