Abstract

Hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (H6PD) is the initial component of a pentose phosphate pathway inside the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) that generates NADPH for ER enzymes. In liver H6PD is required for the 11-oxoreductase activity of 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1, which converts inactive 11-oxo-glucocorticoids to their active 11-hydroxyl counterparts; consequently, H6PD null mice are relatively insensitive to glucocorticoids, exhibiting fasting hypoglycemia, increased insulin sensitivity despite elevated circulating levels of corticosterone, and increased basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in muscles normally enriched in type II (fast) fibers, which have increased glycogen content. Here, we show that H6PD null mice develop a severe skeletal myopathy characterized by switching of type II to type I (slow) fibers. Running wheel activity and electrically stimulated force generation in isolated skeletal muscle are both markedly reduced. Affected muscles have normal sarcomeric structure at the electron microscopy level but contain large intrafibrillar membranous vacuoles and abnormal triads indicative of defects in structure and function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR). SR proteins involved in calcium metabolism, including the sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA), calreticulin, and calsequestrin, show dysregulated expression. Microarray analysis and real-time PCR demonstrate overexpression of genes encoding proteins in the unfolded protein response pathway. We propose that the absence of H6PD induces a progressive myopathy by altering the SR redox state, thereby impairing protein folding and activating the unfolded protein response pathway. These studies thus define a novel metabolic pathway that links ER stress to skeletal muscle integrity and function.

H6PD3 is a bifunctional enzyme that catalyzes the first two steps of the pentose phosphate pathway (1). It is distinct from its cytosolic homolog, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase, in being localized exclusively to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER). H6PD converts glucose 6-phosphate to 6-phosphogluconolactonate with the concomitant production of NADPH, thereby maintaining adequate levels of reductive cofactors in the oxidizing environment of the ER (2, 3).

One critical role for H6PD is providing NADPH to 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1 (11β-HSD1), a bi-directional enzyme highly expressed in liver and adipose tissue. 11β-HSD1 catalyzes both dehydrogenation and oxo-reduction of glucocorticoids, but in vivo it acts predominantly as a NADPH-dependent oxoreductase that converts hormonally inactive cortisone to active cortisol (in rodents, 11-dehydrocorticosterone to corticosterone) (4). To investigate the functional interactions of H6PD and 11β-HSD1 in vivo, we produced mice with a targeted inactivation of H6PD and showed that 11β-HSD1 predominantly acts as a dehydrogenase in these mice (6). The resulting cellular resistance to corticosterone leads to activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and elevated circulating corticosterone levels (7, 8).

H6PD null mice display fasting hypoglycemia and increased insulin sensitivity. Metabolic abnormalities include decreased glucagon-stimulated hepatocyte glucose output and increased basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake in explants from extensor digitorum longus (EDL) muscles, which are normally enriched in relatively insulin-insensitive, glycolytic type IIb fibers. Whereas in vitro experiments implicate impaired glucocorticoid action in the functional abnormalities seen in hepatocytes, it is not known whether the increased glucose uptake in muscle results from glucocorticoid insensitivity or directly from the loss of other actions of H6PD.

Here we show that H6PD null mice suffer a progressive skeletal myopathy. Concurrent changes in metabolism and induction of the unfolded protein response (UPR) pathway are evident by 4 weeks of age, before the most severe histological manifestation of myopathy. These findings highlight a novel role of H6PD in maintaining proper function of the sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) in skeletal muscle.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

All animal experiments and procedures were approved by the respective Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees. H6PD null and wild-type mice were housed in standard conditions on a 12-h/12-h light-dark cycle with access to standard rodent chow and water ad libitum.

Microsome Preparations and H6PD Activity—Liver microsomes were prepared as described (9). SR vesicles were isolated from EDL muscles by Dounce homogenization in 0.3 m sucrose, 0.5 mm EGTA, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.0, and centrifuged at 8000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was saved, and the pellet was resuspended in the same buffer and recentrifuged. The supernatants were pooled, KCl was added to 0.55 m, and the samples were incubated for 1 h at 4 °C. Samples were then centrifuged at 149,000 × g for 1 h at 4 °C, and the pellets were resuspended in 0.3 m sucrose, 0.5 mm EGTA, 0.1 m KCl, 10 mm MOPS, pH 7.4 and frozen at -80 °C until use.

H6PD activity was determined as described (6) with some modifications; microsomes and sarcoplasmic reticulum (200 μg) were permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 30 min at 4 °C. Permeabilized membranes were incubated with 6.6 mm 2-deoxyglucose 6-phosphate (Sigma) in 100 mm KCl, 20 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 20 mm MOPS, pH 8, for 20 min at 37 C with shaking. Reactions were started by adding 0.4 mm NADP+ (Sigma). Absorbance at 340 nm was recorded at 1-min intervals.

Western Blot Analysis—Crude homogenates of muscles from mice 23-week-old (n = 3 for each genotype) were prepared by Dounce homogenization as described above. Protein concentrations were determined by standard Bradford assays. Aliquots containing 33 μg of protein were reduced and denatured, then fractionated on 4–15% gradient SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond P membranes (Amersham Biosciences). Membranes were probed with primary antibodies in TBS-T (137 mm NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20, 20 mm Tris, pH 7.6), and binding was detected with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies and subsequent chemiluminescence (ECL+, Amersham Biosciences). The anti-modulatory calcineurin-interacting protein-1 (MCIP) antibody was previously described (11). Commercial antibodies recognizing calsequestrin, calreticulin, and sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase (SERCA; Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. Santa Cruz, CA), BiP (BD Transductions Laboratories), and proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1α (PGC-1α; Calbiochem) were used.

RNA Isolation and Real-time PCR—Real-time PCR was carried out as described (12) using total muscle RNA extracted with TRI Reagent (Sigma) and treated with DNase I (Invitrogen). Pre-made TaqMan Gene Expression Assays (Applied Biosystems, Cheshire, UK) were used (DDIT3-Mm00492097_m1, HSPA5-Mm00517691_m1, HSP90B1-Mm00441926_m1, CALR-Mm004829936_m1 and H6PD-Mm00557617_m1). Gene expression levels were normalized for RNA loading using 18 S (Taq Man assay reagent, Applied Biosystems) as an internal control. Arbitrary units for expression were calculated using 1000 × 2-ΔCt, where ΔCt = (Ct value of the gene of interest) - (Ct value of 18 S rRNA).

Total RNA for reverse transcription-PCR of XBP1 was extracted from wild-type and null quadriceps with RNA-Stat60 (TEL-TEST Inc., Friendswood, TX). cDNA was prepared with an Advantage RT-for-PCR kit (Clontech Laboratories, Mountainview, CA). Oligonucleotide primers for XBP1 amplification were chosen to anneal to separate exons to avoid amplifying contaminating genomic DNA, with sequences of 5′-CTTGTGGTTGAGAACCAGGAG-3′ (sense) and 5′-ACAGGGTCCAACTTGTCCAG-3′ (antisense).

Histological Analysis—Tissues for routine histology were harvested from anesthetized mice after fixation via transcardial perfusion with 4% paraformaldehyde. Subsequent paraffin processing, embedding, sectioning, and histological stains were performed by standard procedures (13, 14). Tissues were analyzed by hematoxylin and eosin staining in both null and wild-type mice (n = 3 for each genotype). Soleus, gastrocnemius, and tibialis anterior (TA) muscles were analyzed at 8 and 23 weeks and 14 months of age. Frozen sections were stained with oil red O (with hematoxylin counterstaining) to detect lipid content. Alcoholic formalin fixed tissues were stained with periodic acid-Schiff to detect glycogen (Sigma Aldrich). Frozen sections prepared from unfixed, flash-frozen, hindlimb musculature were stained by metachromatic ATPase (15) to determine fiber type.

Running Wheel Activity—Mice (n = 5 for each genotype) were housed individually in a cage equipped with a 25-cm diameter running wheel. Wheel revolutions were recorded for 5 days using a magnetic switch attached to a counter.

Ex Vivo Muscle Contraction—Isolated EDL and soleus muscles from wild-type or H6PD null mice were mounted to an isometric force transducer using 4/0 silk sutures. Muscles were immersed in physiological salt solution gassed continuously (95% O2, 5% CO2) and maintained at 33 °C. Optimal length was determined using a series of 200-ms tetany induced by electrical stimulation (25 V, 150 Hz, 0.2-ms pulse duration). Muscles remained quiescent for 30 min after determination of optimal length. Thereafter, muscles were stimulated for 500 ms at 1, 15, 25, 50, 75, 100, 125, 150, and 300 Hz with a 30-min recovery period between measurements. Force development was digitally recorded using a Powerlab 8/S data acquisition unit (AD Instruments). Optimal muscle length and tendon-free mass were used to calculate muscle cross-sectional area. Force generation was expressed as newtons/cm2 of cross-sectional area.

Electron Microscopy—Samples of skeletal muscle were fixed by immersion in ice-cold glutaraldehyde phosphate-buffered saline (2.5%w/v) supplemented with 0.1 mm KCN. Sections were stained in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and vacuum-embedded in resin (16). Ultra-thin (80 nm) sections were cut from outer parts of tissue blocks on a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome, post-stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and viewed and photographed on a JEOL JEM-1200EX II electron microscope operating at 120 kV.

Affymetrix Microarray Experiments—All experiments were performed using the Affymetrix human mouse genome 430 2.0 oligonucleotide array set and complied with the Minimum Information about a Microarray Experiment (MIAME) standard. Total RNA was used to prepare biotinylated-target RNA according to the manufacturer's recommendations.

We analyzed three sets of RNA samples from tibialis anterior and soleus muscles of wild-type and null mice and carried out local-pooled-error analysis to identify significant differentially expressed genes (17). Data were normalized using GEPAS-Express and local-pooled-error variance calculated using the base-line error distribution for the wild-type and null samples, thus determining a z-statistic for each gene. A Benjamini-Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied to control the type I error rate (18). The list of genes that were differentially expressed (FDR < 0.05) in either TA or soleus are included as supplemental Tables S1 and S2, respectively.

RESULTS

Abnormalities of Activity and Muscle Mass in H6PD Null Mice—Whereas null mice ambulated normally, they were decidedly weaker and more docile than wild-type littermates during routine handling. Null mice had generalized muscle atrophy, with post-mortem muscle tissue weights reduced by 20–40%. Additionally, null mice displayed a prominent kyphosis that intensified with age; however, the kyphotic vertebra showed no obvious skeletal abnormalities (data not shown).

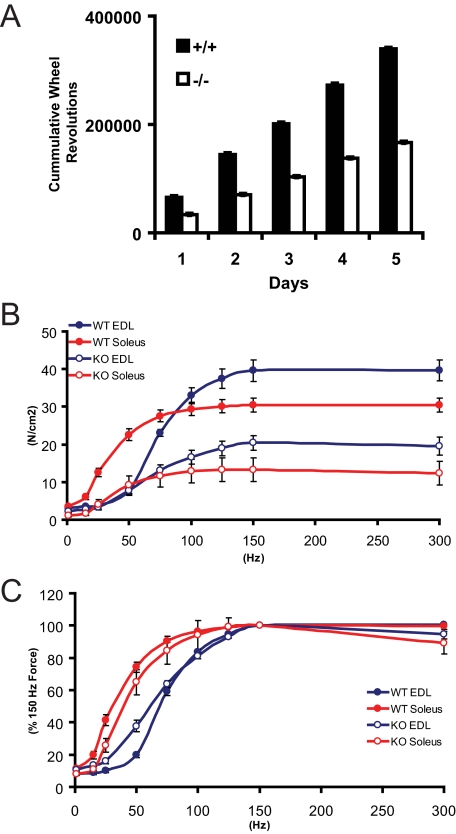

Null and wild-type mice (n = 5) were assessed for spontaneous activity in a running wheel cage. After 5 days null mice had significantly less (p < 0.00002) cumulative activity (166,611 ± 383 revolutions) than wild-type (339472 ± 750 revolutions, Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 1.

Quantitative functional assessment of the myopathy. A, activity assessment of wild-type and H6PD null mice by voluntary running wheel usage. B, electrically stimulated force generation capacity of isolated soleus and EDL muscles from wild-type (WT) and H6PD null mice (KO), corrected for cross-sectional area. C, peak force generation at a range of stimulation frequencies, plotted as percent of maximal force (at 150 Hz stimulation).

Isolated Mutant Skeletal Muscle Contractions Are Weaker than Normal—Submaximal and maximal isometric force responses were obtained with isolated muscles in response to electrical stimulation. Developed forces were markedly reduced in both fast-twitch EDL and slow-twitch soleus muscles from H6PD null mice (Fig. 1B). In EDL muscles isometric forces were significantly reduced at electrical stimulation frequencies from 75-to 300 Hz, with maximal tetanic force (150 Hz electrical stimulation) reduced by 48% (Fig. 1B). At lower frequencies contractile forces of EDL muscles were similar between wild-type and H6PD null mice. When force values were normalized for maximal responses, a partial leftward shift in the force-frequency curve for mutant EDL muscles was observed at frequencies between 1 and 50 Hz (Fig. 1C). Force generation in slow-twitch soleus muscle from H6PD null mice was also reduced at all electrical stimulation frequencies with twitch force (stimulation at 1 Hz) and maximal tetanic force reduced by 68 and 56%, respectively.

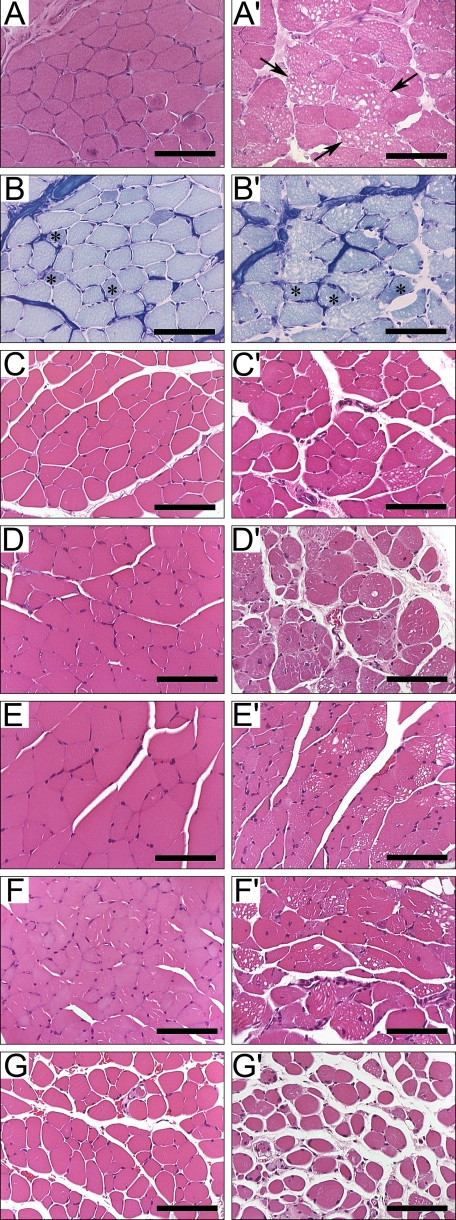

Muscles from Null Mice Are Atrophic and Vacuolated and Display Fiber Type Switching—Skeletal muscle atrophy was apparent from 8 to 10 weeks onward in all muscles studied. Muscles enriched in type IIb fibers, including TA and gastrocnemius, were markedly vacuolated (Fig. 2). Serial sections from TA of 8-week-old mice stained with either hematoxylin-eosin or with metachromatic ATPase staining to determine fiber type analysis clearly show vacuoles in highly glycolytic, fast twitch type IIb fibers, whereas slow twitch type I fibers are spared (Fig. 2, A, A′, B, and B′). Vacuoles were not found in soleus muscle, which contains predominantly types I and IIa fibers. EDL was affected only at later time points (Fig. 2, G and G′).

FIGURE 2.

Progressive histological defects in H6PD null skeletal muscle. Transverse muscle sections from wild-type (A–G) and null (A′–G′) mice. Comparing serial TA sections at 8 weeks, stained with hematoxylin and eosin (A and A′) and metachromatic ATPase (B and B′) show vacuoles (arrows) present predominately in type IIb fibers. Asterisks indicate type IIa fibers. Additional TA sections at 23 weeks (C and C′) and 14 months (D and D′) show increased vacuolation, centralized nuclei, and fibrosis. Similar increases are seen in gastrocnemius at 23 weeks (E and E′) and 14 months (F and F′). By 14 months, damage is seen in EDL (G and G′). The 8-week and 14-month samples were cryo-embedded, and the 23 week samples were paraffin-embedded. The reference bar is 80 μm.

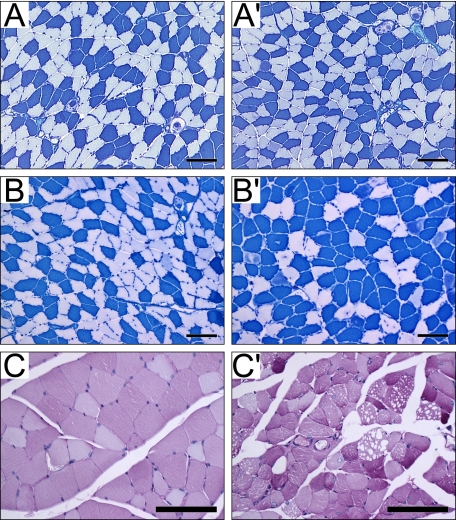

When soleus muscles from null and wild-type mice were analyzed for fiber type composition using metachromatic ATPase staining (Fig. 3, A, A′, B, and B′), no changes were seen in either the number or fiber content at 8 weeks. At 23 weeks, although there was no change in the total number of fibers present, null mice showed a decrease in type II fibers (null 37.6 ± 1.3% versus wild-type 56.3 ± 1.1%; n = 3, p < 0.0001) and a concomitant increase in type I fibers (null 62.4 ± 1.3% versus wild-type 43.7 ± 1.1%, p < 0.0001). A large number of type II muscle fibers contained centralized nuclei, which are typically seen in regenerating fibers resulting from injury (Fig. 3B′).

FIGURE 3.

Fiber type switching and glycogen accumulation in skeletal muscle. Fiber type analysis of (A) wild-type and (A′) null transverse sections of soleus muscle showing a normal distribution of type I fibers (blue) and type IIa fibers (off white) in both null and wild-type sections at 8 weeks of age. By 23 weeks of age, no difference is seen in wild-type muscles (B), but null muscles (B′) show a loss of type IIa fibers with a concomitant increase in type I fibers. Periodic acid-Schiff-stained gastrocnemius sections comparing wild-type (C) with null (C′) muscles show an increase in glycogen content in some null fibers. Note that the vacuoles do not contain glycogen. The reference bar is 80 μm.

Periodic acid-Schiff staining was used as a qualitative indicator of glycogen accumulation in muscle sections. Null muscles showed increased heterogeneity in periodic acid-Schiff staining as compared with wild-type, indicating higher glycogen content in some fibers (Fig. 3, C and C′). Increased glycogen concentration did not correlate with vacuolation, as intensely stained fibers did not contain vacuoles (Fig. 3C′). Additionally, as assessed by oil red O staining, the muscle vacuoles did not contain lipid (data not shown).

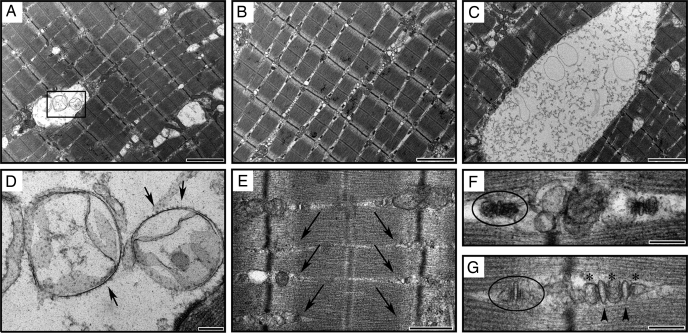

Vacuoles in Mutant Muscles Consist of Abnormal Sarcoplasmic Reticula—Muscles from null mice had grossly normal sarcomeric structure as assessed by electron microscopy but had prominent vacuoles of variable size containing membranous inclusions (Fig. 4, A and C). The location of the vacuoles and the presence of ryanodine receptors (19) with their cytoplasmic domains prominently displayed on the surface of many of the inclusions indicate that they are derived from sarcoplasmic reticula (Fig. 4D). Triad junctions, a structural complex of two terminal SR cisternae flanking a T-tubule, are normally present near the boundary between the A and I bands of skeletal muscle. In H6PD null muscles, triads were frequently missing in areas adjacent to the vacuoles (see the arrows in Fig. 4E). In addition, structurally abnormal triads also contained multiple T-tubules and terminal SR extensions (Fig. 4G), further indicating a disruption of the normal SR structure. Because multimers of some SR proteins are large enough to be visualized by electron microscopy, the loss of electron density in triads of null muscle compared with those of wild-type (Fig. 4F) suggests a change in either expression or localization of SR resident proteins.

FIGURE 4.

Ultrastructural abnormalities in skeletal muscles from null mice. Two representative fields of null (A and C) gastrocnemius sections compared with wild type (B) show a range of vacuole sizes and types present at low magnification. The boxed region in A depicts the high magnification view seen in D. Arrows in the high magnification view (D) denote the ryanodine receptor complexes on the surface of vesicles within the vacuoles. The absence of triads (E) normally seen at the boundary of the A and I bands is indicated by the arrows. Isolated triads are outlined with an oval in wild-type (F) and null (G) muscle at high magnification. Note the decrease in electron-dense regions in the terminal SR in the null compared with the wild-type triad. Also note the abnormal triad or “pentad” consisting of two T-tubules (arrowheads) and three terminal SR (asterisks) in the null. The sizes of the reference bars are as follows: A–C, 2000 nm; D–G, 200 nm; E, 500 nm.

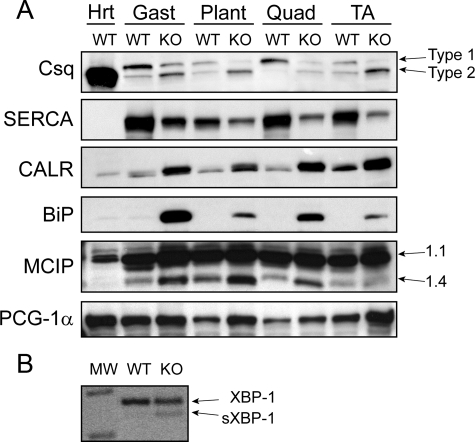

The apparent myodegeneration and obvious disturbance of SR structure coupled with the loss of electron density in the triads led us to examine the expression of SR proteins. When Western blots containing crude muscle extracts from wild-type and null muscles were compared, changes in expression of calsequestrin, SERCA, BiP (immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein or HSPA5 or GRP78), and calreticulin were detected (Fig. 5A). There was a shift in expression of calsequestrin isoforms, with an increase in the type II (cardiac) and a decrease in the type I (skeletal) isoform. In particular muscles, e.g. plantaris and TA, expression of the skeletal isoform was almost absent. SERCA, although expressed at variable levels in wild-type muscles, showed large decreases in all null muscles tested. Conversely, the levels of calreticulin (a calcium binding stress protein) and BiP (an important stress protein responsive to levels of unfolded proteins in the ER) were increased in all null muscles relative to wild type.

FIGURE 5.

Activation of the UPR pathway affects expression of proteins involved in calcium metabolism and fiber type switching. Western blots of crude muscle lysates from 23-week-old mice (A) were probed with the indicated antibodies. Hrt, heart; Gast, gastrocnemius; Plant, plantaris; Quad, quadriceps. PCR amplification (B) of total RNA from wild-type (WT) and null (KO) muscle shows increased IRE1 splicing and activation of XBP1. The unspliced XBP1 band = 274 bp, and the sXBP1 band = 246 bp. The photograph of the ethidium bromide-stained gel has been converted to a negative image for increased clarity. Csq, calsequestrin; CALR, calreticulin.

Calcineurin Activation Is Involved in Fiber Type Switch in Null Muscles—Calcineurin, a calcium-activated protein phosphatase, is involved in regulating muscle fiber type-specific proteins and myofiber remodeling through its actions on the nuclear factor of activated T-cells (NFAT) (20). To determine whether calcineurin activation was involved in the fiber type switch in null muscles, we monitored the expression of the products of two calcineurin-regulated genes, an isoform of the MCIP1.4, and peroxisome PGC-1α.

Western blots of crude muscle extracts were probed with an anti-MCIP antibody that recognizes all isoforms (Fig. 5A); constitutive expression of the 1.1 isoform at 37 kDa served as an internal control. The 1.4 isoform, at 24 kDa, was expressed at low levels in wild-type muscle but was up-regulated in all null muscles with the exception of TA. Basal levels of PGC-1α expression varied between wild-type muscles, but relative expression was up-regulated in all corresponding null muscles (Fig. 5A).

The UPR Is Activated in Mutant Muscles—Increased BiP expression in null muscles is indicative of ER stress; in particular, the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER subsequently activates the UPR pathway. A subset of the UPR pathway is initiated by signal transduction cascades originating through the inositol-requiring protein 1 (IRE1, ERN1). Activation of the IRE1 pathway triggers an inducible post-transcriptional splicing event that produces the functional transcription factor, spliced XBP1 (sXBP1). We used reverse transcription-PCR to confirm splicing and the subsequent presence of the activated transcription factor sXBP1 (Fig. 5B). The expression of unspliced and, therefore, inactive XBP1 is revealed by the presence of a 274-bp amplicon. A very low level of spliced and activated XBP1 (sXBP1), indicated by a 248-bp amplicon, is seen in wild-type muscle, but a clear induction is detected in null muscle.

Microarray Analysis Confirms Abnormal Expression of Genes Responding to Stress in the Endoplasmic Reticulum—We carried out microarray analysis on TA and soleus muscles from 4-week-old mice (these data sets have been deposited in the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus with the accession number GSE10347). Using a threshold FDR of 0.05, 323 probe sets representing 266 independent genes differed in expression between wild-type and mutant TA muscles. Only 64 probe sets representing 56 genes differed in soleus muscles, and only 23 probe sets differed in both types of muscle (supplemental Table S1).

To identify functional relationships among differentially expressed genes, we queried a knowledge base (Ingenuity Systems, Redwood City, CA) (21) that had listings for 4142 genes expressed in TA muscle. When an FDR of 0.05 was used as a threshold criterion, 11 minimally overlapping subnetworks of interrelated genes were enriched for these differentially expressed genes. The highest-scoring subnetwork (38 genes meeting the threshold FDR of 0.05; probability score <10-63) was enriched (p = 1.3 × 10-6 by Fisher's Exact Test) for genes with known functions in the endoplasmic reticulum stress response (Fig. 6A). This network could be merged with several other subnetworks to yield a network containing 65 of the 269 genes dysregulated in TA muscles (supplemental Fig. 1). In contrast, no high scoring network could be identified among genes dysregulated in soleus muscles.

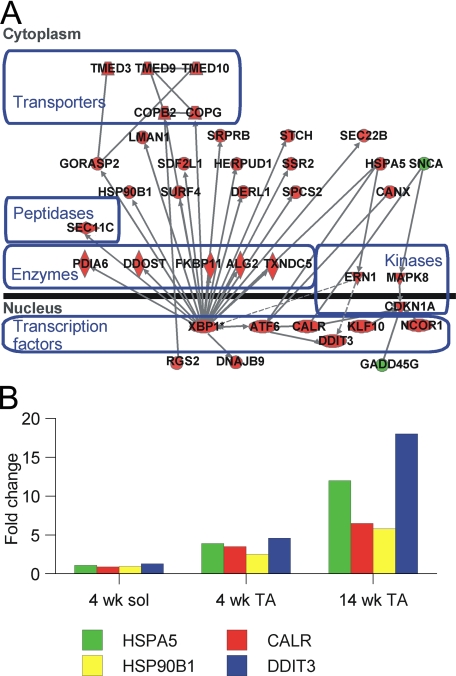

FIGURE 6.

Altered gene expression consistent with endoplasmic reticulum stress and UPR activation in null muscle. A, diagram of a network of functionally related genes that are dysregulated in mutant TA muscle. Shapes represent protein products of various types as noted and are positioned according to their predominant site of expression in the nucleus or cytoplasm. Red and green denote genes that are overexpressed or under-expressed in mutant muscle, respectively. Lines connecting genes represent functional relationships such as physical interactions or influences on gene expression. A more extensive network is displayed in supplemental Fig. 1. B, expression of selected UPR pathway genes in muscles from mice at 4 weeks of age shows induction of 2.5–5-fold in TA but not soleus (sol) muscle. Further increases in expression detected at 14 weeks in TA muscle indicate progressive ER stress.

With the use of real-time PCR, we confirmed expression levels of four genes involved in ER stress responses: HSPA5 (BiP), HSP90B1 (glucose-regulated protein 94), calreticulin, and DDIT3 (CHOP10-C/EBP-homologous protein). All 4 genes were overexpressed by 2–5-fold in TA muscles from 4-week-old null mice, whereas expression in the soleus was comparable with that in wild-type samples (Fig. 6B). These changes persisted in 14-week-old mice; the same genes were overexpressed 5–18-fold in TA muscles from null compared with wild-type mice.

H6PD Is Expressed and Generates NADPH in Skeletal Muscle—H6PD mRNA was not detected in mutant muscle; however, in wild-type mice H6PD mRNA levels were ∼25% that in liver. As measured by NADPH production, H6PD activity was present in isolated microsomes from liver and muscle of wild-type but not mutant mice. Normalized H6PD activity in muscle was ∼45% that in liver (not shown).

DISCUSSION

Deletion of H6PD Affects Skeletal Muscle—Deletion of H6PD resulted in both decreased spontaneous locomotor activity in the whole animal and reduced force generation in isolated muscles. In addition, null mice displayed a prominent kyphosis that intensified with age, a relatively common phenotype in mouse models of neuromuscular diseases such as the mdx mouse (22) and the kyphoscoliosis (ky) mouse (23). Because normal extension by the animal or gentle manipulation by a handler corrected the curvature, it is likely that the inherent skeletal muscle weakness also underlies this phenotype.

Metabolic Implications of Fiber Type Switching—A significant fiber type switch from type II (fast) to type I (slow) was apparent in soleus muscles of null mice. Although not yet fully characterized, the switch apparently occurs in a relatively narrow time window from 8 to 23 weeks. Skeletal muscle fiber type switching due to specific regulation of slow fiber-specific genes is controlled by the calcineurin pathway (24). Calcineurin, a calmodulin-dependent protein phosphatase that senses intracellular calcium levels, dephosphorylates the NFAT, which translocates to the nucleus and regulates a cascade of muscle remodeling genes (25). The expression of downstream calcineurin/NFAT-regulated genes provides a reliable measure of calcineurin activation. We chose to monitor MCIP1.4, an isoform of the MCIP1, also known as DSCR1 (26) and RCAN1 (27), transcribed from an alternative calcineurin-regulated promoter (28), and peroxisome PGC-1a (29, 30), both known to be involved in fiber type formation as markers of calcineurin/NFAT pathway activation.

With the notable exception of TA, MCIP1.4 expression is up-regulated in all muscles examined from H6PD null mice. Although some transcripts of MCIP1 reportedly are directly UPR-inducible (31), this is unlikely to pertain here, as both BiP and calreticulin are induced in null TA muscles (reflecting UPR activation), and PGC-1α expression is similarly up-regulated in all muscles examined. In addition to calcineurin, PGC-1α expression is induced by a variety of stimuli including glucagon and certain external stimuli, e.g. exercise and fasting (for review, see Ref. 32). Although additional stimuli may play a role in induction of PGC-1α in muscle cells, the improved insulin sensitivity in H6PD null mice argues against a role for glucagon. Taken together, these results indicate that calcineurin activation, presumably a consequence of increased intracellular calcium concentration, is likely responsible for the fiber type switch.

Skeletal muscle glycogen content is abnormal in null mice. Activation of calcineurin is one plausible mechanism to explain this, because transgenic mice overexpressing constitutively active mutant calcineurin also have increased glycogen deposition in muscle and increased basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake (33). The link between the calcineurin pathway and glycogen metabolism is supported by the fact that both abnormal calcineurin activation and higher glycogen content are particularly found in muscles composed mainly of type II fibers (e.g. gastrocnemius). However, it is not known whether other effects of H6PD deficiency influence glycogen deposition or whether the effects of calcineurin activation on glycogen deposition are solely a consequence of increased basal and insulin-stimulated glucose uptake or also reflect other dysregulated cellular processes.

H6PD Deficiency Causes a Novel Myopathy Associated with the UPR Pathway—The UPR pathway is a well defined, multiarmed homeostatic response that is initiated by a variety of cellular insults affecting the transit of secretory proteins through the ER. Ultimately, such insults result in the accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, i.e. a state of ER stress (for review, see Refs. 34–37). Recently, ER stress and the UPR pathway have been implicated in a variety of pathophysiological conditions, including Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and some forms of diabetes and hepatic diseases (for review, see Ref. 37). In addition, up-regulation of UPR proteins has been detected in some skeletal myopathies including some forms of inclusion body myositis (IBM) (39, 40) and inclusion body myopathy associated with Paget disease of bone and frontotemporal dementia (IBMPFD) (41).

Deletion of H6PD induces a robust ER stress response as evidenced by increased expression of components of the UPR pathway to compensate for ER protein overload. The decrease in SERCA protein expression is consistent with translational attenuation of non-internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-containing transcripts resulting from activation of the PKR-like ER kinase pathway, whereas the downstream target of activating transcription factor 4 (which contains an IRES), the C/EBP-homologous protein (CHOP10 or DDIT3), is induced.

The activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6) pathway is chiefly responsible for the induced expression of protein chaperones. Consistent with ATF6 pathway activation, we saw induction of ATF6 and protein chaperones including BiP (immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein or HSPA5 or GRP78), HSP90B1 (or glucose-regulated protein 94), and HSP40 (or Dnajb9). Calreticulin, induced at both the protein and gene expression levels in null muscles, is likely a component of the ATF6 pathway.

XBP1, a component of the IRE1 pathway, regulates expression of many genes (42), including several involved in ER-associated protein degradation (43, 44). Indeed, we detected increased expression of genes involved in protein degradation, including the members of the Der1p-like protein (Derlin1 and Derlin 3) family.

The structural aspects of the myopathy (the occurrence of large membranous vacuoles visible on hematoxylin-eosin-stained sections and the triad junction abnormalities seen by electron microscopy) can be readily explained by activation of the ER stress response. sXBP1 is involved in the synthesis of phosphatidylcholine, the predominant phospholipid in the ER membrane. Overexpression of sXBP1 in NIH-3T3 cells results in a significant increase in ER surface area (45). Our results showing ryanodine receptor-containing membranes in the vacuoles, and expression of sXBP1 in null muscles are consistent with the role of XBP1 in membrane biogenesis. Perturbation of the normal SR structure by the markedly increased membrane volume likely is responsible for both the loss of triads in areas adjacent to the vacuoles and the observed abnormal triad structures.

The vacuoles appear to be restricted to predominantly fast-twitch muscles as they are found early in TA and gastrocnemius/plantaris but not in soleus. Likewise, gene expression analysis indicates that the ER stress response is much more severe in TA than in soleus and progressively worsens with age. Intrinsic differences in metabolism between fiber types may underlie these observations. In particular, the SR is the site of calcium uptake, storage, and release for muscle contraction, all of which are processes sensitive to redox state. Thus, it is plausible that changes in metabolism and redox status act in concert to influence the phenotype. The electron density of the triads of null mice is decreased compared with that of wild-type triads. Given that calsequestrin, a low affinity, high capacity calcium-binding protein localized in the terminal SR assembles into calcium-dependent polymers large enough to be seen by electron microscopy (46), an obvious prediction is that there is an accompanying decrease in calsequestrin expression. Rather than a decrease, however, there is a shift in isoform expression. Null muscles showed decreased expression of the type 1 (skeletal) isoform with accompanying overexpression of the Type 2 (cardiac) isoform, which is encoded by a separate gene. The significance of the change is unclear. The triad junctions constitute the calcium release units in skeletal muscle (47). The combination of decreased SERCA expression, altered calsequestrin expression, and perturbations in triad structure may play a role in the putative calcium signaling and subsequent calcineurin activation involved in fiber type switch.

Why Does H6PD Deficiency Cause Myopathy?—The increased deposition of glycogen in skeletal muscle may contribute to the observed pathology as humans with glycogen storage disease II (Pompe disease) develop weakness of skeletal muscles in addition to involvement of the heart and diaphragm. However, neither affected humans nor mouse models of glycogen storage disease II develop vacuoles in muscle fibers. Similarly, mice transgenic for the glycogen synthase gene display neither muscle weakness nor obvious muscle pathology other than glycogen deposition (48). Thus, although a role for glycogen deposition in the myopathy of H6PD null mice cannot be excluded, it is unlikely to be the primary cause.

At present, we cannot rule out the possibility that the observed phenotype is affected by local glucocorticoid inactivation in muscle due to the gain in 11β-HSD1 dehydrogenase function. However, 11β-HSD1 is expressed in muscle at only ∼5% that of the levels in liver, suggesting that it does not significantly modulate glucocorticoid availability in muscle. Moreover, deletion of H6PD does not phenocopy other genetic models lacking glucocorticoids in development and during adulthood, arguing against a pathogenetic role for glucocorticoids (10, 38).

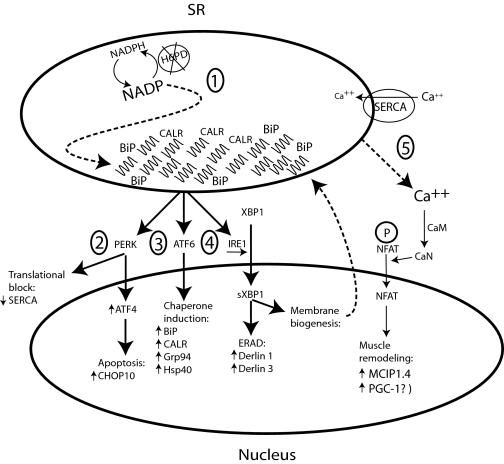

Alternatively, we propose that the loss of H6PD and the consequent change in NADPH/NADP+ ratio is a specific stressor that affects the redox balance and ultimately disrupts the normal protein-folding environment of the SR (Fig. 7). The subsequent accumulation of unfolded proteins activates the UPR pathway in an effort to relieve the stress and restore homeostasis. Activation of the UPR pathway slows general protein translation and induces the expression of specific chaperones, degradative proteins, and enzymatic pathways that increase SR volume. Insufficient relief of the stress results in myofiber loss and associated remodeling from the endogenous satellite cell population. Because the activation of the UPR and appearance of the intrafibular vacuoles precedes the fiber type switch, it is likely the calcium-mediated activation of calcineurin is secondary to dysregulated expression of SR proteins involved in calcium metabolism.

FIGURE 7.

A model for the activation of the UPR in the absence of H6PD. 1, H6PD deletion disrupts the redox balance of the ER, resulting in unfolded protein accumulation and activation of the PERK, ATF6, and IRE1 pathways. 2, a PERK-induced translational block of transcripts without an internal ribosome entry site decreases secretory protein flow through the ER, and if rescue mechanisms are unsuccessful, induces the expression of pro-apoptotic genes. 3, ATF6 induced expression of ER resident chaperones speeds up protein folding. 4, IRE1 induced splicing and activation of XBP1 up-regulates both ER-associated protein degradation (ERAD) and phospholipid metabolism involved in ER membrane biogenesis. 5, the dysregulation of proteins involved in calcium metabolism increases intracellular calcium which activates the calcineurin pathway. Dashed lines indicate presumed interactions. Small arrows denote up- or down-regulation of gene expression. GRP94, glucose-regulated protein 94 (HSP90B1); BiP, immunoglobulin heavy chain-binding protein (GRP78, HSPA5) CHOP10-C/EBP-homologous protein (DDIT3); CALR, calreticulin; Derlin, Der1p-like protein; Hsp40, heat shock protein 40; IRE1, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; IRES, internal ribosome entry site; PERK, PKR-like ER kinase; PGC-1α, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator-1 α; XBP1, X-box-binding protein 1; sXBP1, spliced XBP1.

Other metabolic pathways may also be dysregulated. For example, the gene most dysregulated in mutant TA muscle, adenosine monophosphate deaminase 1 (under-expressed 13.4-fold), catalyzes the deamination of adenosine monophosphate to inosine monophosphate in skeletal muscle, an important step in the purine nucleotide cycle. Mutations in this isozyme are probably the most common cause of metabolic myopathy in humans (5), suggesting that disordered purine metabolism from decreased adenosine monophosphate deaminase 1 expression could potentially play a role in the development of myopathy in H6PD mutant mice.

Although this model accounts for most of the observed features of this novel genetic myopathy, the SR components most directly affected by the altered redox balance and the full molecular basis for the phenotype remain to be elucidated. We anticipate that the H6PD knock-out mouse will provide a novel genetic model in which to explore further the interplay between ER redox state and the cellular stress responses.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Beverly Rothermel for kindly sharing reagents and for invaluable discussions and Kelli Black, Emily Harris, Amanda Keith, and Heather Powell for excellent technical support.

This study was supported in part by Wellcome Trust Grants 066357 (to P. M. S.) and 074088/Z/04/Z (to E. A. W. and P. M. S.), National Institutes of Health Grant DK54480 and the Wilson Center for Biomedical Research (to K. L. P.), and National Institutes of Health Grant DK068101 and the Audre Newman Rapoport Chair in Pediatric Endocrinology (to P. C. W.). The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains a supplemental figure and Tables S1 and S2.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: H6PD, hexose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; ER, endoplasmic reticulum; EDL, extensor digitorum longus; MOPS, 4-morpholinepropanesulfonic acid; SR, sarcoplasmic reticulum; 11β-HSD1, 11β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase type 1; UPR, unfolded protein response; PGC-1α, proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator-1; SERCA, sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum calcium ATPase; TA, tibialis anterior; FDR, false discovery rate; NFAT, nuclear factor of activated T-cells; IRE1, inositol-requiring protein 1; sXBP, spliced XBP1; MCIP1, modulatory calcineurin-interacting protein 1; ATF, activating transcription factor; PKR, double-stranded RNA-dependent protein kinase.

References

- 1.Mason, P. J., Stevens, D., Diez, A., Knight, S. W., Scopes, D. A., and Vulliamy, T. J. (1999) Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 25 30-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Banhegyi, G., Marcolongo, P., Fulceri, R., Hinds, C., Burchell, A., and Benedetti, A. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272 13584-13590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Piccirella, S., Czegle, I., Lizak, B., Margittai, E., Senesi, S., Papp, E., Csala, M., Fulceri, R., Csermely, P., Mandl, J., Benedetti, A., and Banhegyi, G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 4671-4677 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tomlinson, J. W., Walker, E. A., Bujalska, I. J., Draper, N., Lavery, G. G., Cooper, M. S., Hewison, M., and Stewart, P. M. (2004) Endocr. Rev. 25 831-866 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morisaki, T., Gross, M., Morisaki, H., Pongratz, D., Zollner, N., and Holmes, E. W. (1992) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 89 6457-6461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavery, G. G., Walker, E. A., Draper, N., Jeyasuria, P., Marcos, J., Shackleton, C. H., Parker, K. L., White, P. C., and Stewart, P. M. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281 6546-6551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogoff, D., Ryder, J. W., Black, K., Yan, Z., Burgess, S. C., McMillan, D. R., and White, P. C. (2007) Endocrinology 148 5072-5080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavery, G. G., Hauton, D., Hewitt, K. N., Brice, S. M., Sherlock, M., Walker, E. A., and Stewart, P. M. (2007) Endocrinology 148 6100-6106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hori, H., Nembai, T., Miyata, Y., Hayashi, T., Ueno, K., and Koide, T. (1999) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 126 722-730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kotelevtsev, Y., Holmes, M. C., Burchell, A., Houston, P. M., Schmoll, D., Jamieson, P., Best, R., Brown, R., Edwards, C. R., Seckl, J. R., and Mullins, J. J. (1997) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 94 14924-14929 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bush, E., Fielitz, J., Melvin, L., Martinez-Arnold, M., McKinsey, T. A., Plichta, R., and Olson, E. N. (2004) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 101 2870-2875 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bujalska, I. J., Draper, N., Michailidou, Z., Tomlinson, J. W., White, P. C., Chapman, K. E., Walker, E. A., and Stewart, P. M. (2005) J. Mol. Endocrinol. 34 675-684 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shehan, D. C., and Hrapchak, B. B. (1980) Theory and Practice of Histotechnology, 2nd Ed., Battelle Press, Columbus, OH

- 14.Woods, A. E., and Ellis, R. C. (1996) Laboratory Histopathology, A Complete Reference, Churchill Livingstone, Edinburgh, UK

- 15.Ogilvie, R. W., and Feeback, D. L. (1990) Stain Technol. 65 231-241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.O'Brien, K. M., Skilbeck, C., Sidell, B. D., and Egginton, S. (2003) J. Exp. Biol. 206 411-421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jain, N., Thatte, J., Braciale, T., Ley, K., O'Connell, M., and Lee, J. K. (2003) Bioinformatics 19 1945-1951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reiner, A., Yekutieli, D., and Benjamini, Y. (2003) Bioinformatics 19 368-375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Saito, A., Seiler, S., Chu, A., and Fleischer, S. (1984) J. Cell Biol. 99 875-885 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bassel-Duby, R., and Olson, E. N. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75 19-37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calvano, S. E., Xiao, W., Richards, D. R., Felciano, R. M., Baker, H. V., Cho, R. J., Chen, R. O., Brownstein, B. H., Cobb, J. P., Tschoeke, S. K., Miller-Graziano, C., Moldawer, L. L., Mindrinos, M. N., Davis, R. W., Tompkins, R. G., and Lowry, S. F. (2005) Nature 437 1032-1037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lefaucheur, J. P., Pastoret, C., and Sebille, A. (1995) Anat. Rec. 242 70-76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mason, R. M., and Palfrey, A. J. (1984) J. Orthop. Res. 2 333-338 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chin, E. R., Olson, E. N., Richardson, J. A., Yang, Q., Humphries, C., Shelton, J. M., Wu, H., Zhu, W., Bassel-Duby, R., and Williams, R. S. (1998) Genes Dev. 12 2499-2509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olson, E. N., and Williams, R. S. (2000) BioEssays 22 510-51910842305 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuentes, J. J., Pritchard, M. A., Planas, A. M., Bosch, A., Ferrer, I., and Estivill, X. (1995) Hum. Mol. Genet. 4 1935-1944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harris, C. D., Ermak, G., and Davies, K. J. (2005) Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 62 2477-2486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rothermel, B. A., Vega, R. B., and Williams, R. S. (2003) Trends Cardiovasc. Med. 13 15-21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lin, J., Wu, H., Tarr, P. T., Zhang, C. Y., Wu, Z., Boss, O., Michael, L. F., Puigserver, P., Isotani, E., Olson, E. N., Lowell, B. B., Bassel-Duby, R., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2002) Nature 418 797-801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Puigserver, P., and Spiegelman, B. M. (2003) Endocr. Rev. 24 78-90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leahy, K. P., Davies, K. J., Dull, M., Kort, J. J., Lawrence, K. W., and Crawford, D. R. (1999) Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 368 67-74 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Corton, J. C., and Brown-Borg, H. M. (2005) J. Gerontol. A Biol. Sci. Med. Sci. 60 1494-1509 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ryder, J. W., Bassel-Duby, R., Olson, E. N., and Zierath, J. R. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278 44298-44304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wu, J., and Kaufman, R. J. (2006) Cell Death Differ. 13 374-384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bernales, S., Papa, F. R., and Walter, P. (2006) Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 22 487-508 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schroder, M. (2006) Mol. Biotechnol. 34 279-290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yoshida, H. (2007) FEBS J. 274 630-658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Coll, A. P., Challis, B. G., Lopez, M., Piper, S., Yeo, G. S., and O'Rahilly, S. (2005) Diabetes 54 2269-2276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Vattemi, G., Engel, W. K., McFerrin, J., and Askanas, V. (2004) Am. J. Pathol. 164 1-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liewluck, T., Hayashi, Y. K., Ohsawa, M., Kurokawa, R., Fujita, M., Noguchi, S., Nonaka, I., and Nishino, I. (2007) Muscle Nerve 35 322-326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Watts, G. D., Wymer, J., Kovach, M. J., Mehta, S. G., Mumm, S., Darvish, D., Pestronk, A., Whyte, M. P., and Kimonis, V. E. (2004) Nat. Genet. 36 377-381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Acosta-Alvear, D., Zhou, Y., Blais, A., Tsikitis, M., Lents, N. H., Arias, C., Lennon, C. J., Kluger, Y., and Dynlacht, B. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 27 53-66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Travers, K. J., Patil, C. K., Wodicka, L., Lockhart, D. J., Weissman, J. S., and Walter, P. (2000) Cell 101 249-258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Oda, Y., Okada, T., Yoshida, H., Kaufman, R. J., Nagata, K., and Mori, K. (2006) J. Cell Biol. 172 383-393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sriburi, R., Jackowski, S., Mori, K., and Brewer, J. W. (2004) J. Cell Biol. 167 35-41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Franzini-Armstrong, C., Kenney, L. J., and Varriano-Marston, E. (1987) J. Cell Biol. 105 49-56 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dulhunty, A. F. (2006) Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 33 763-772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Manchester, J., Skurat, A. V., Roach, P., Hauschka, S. D., and Lawrence, J. C., Jr. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 93 10707-10711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.