Abstract

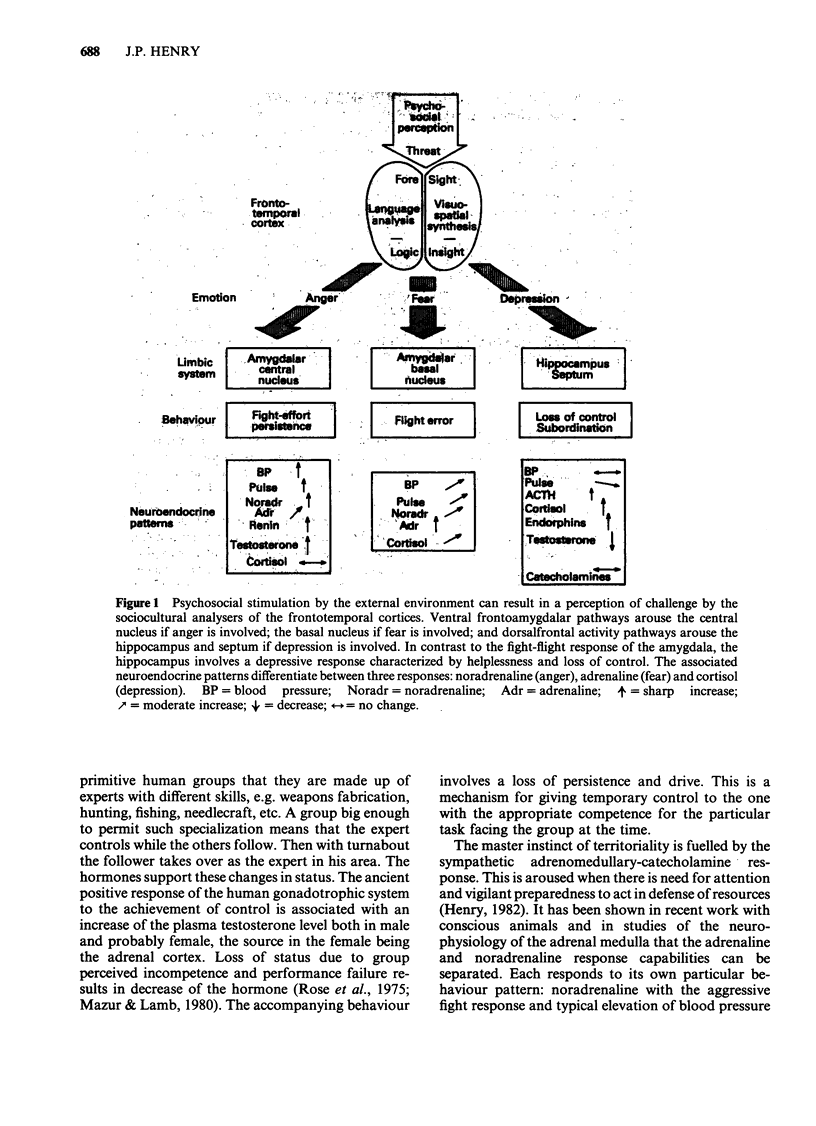

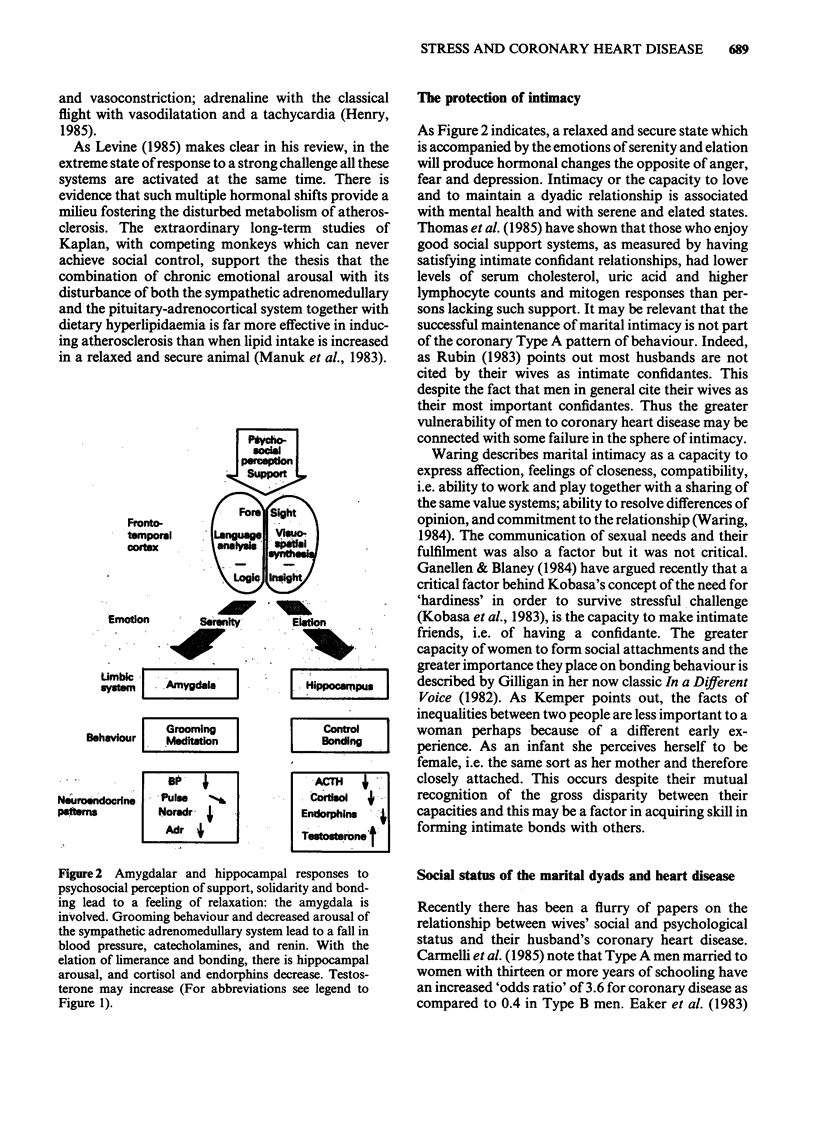

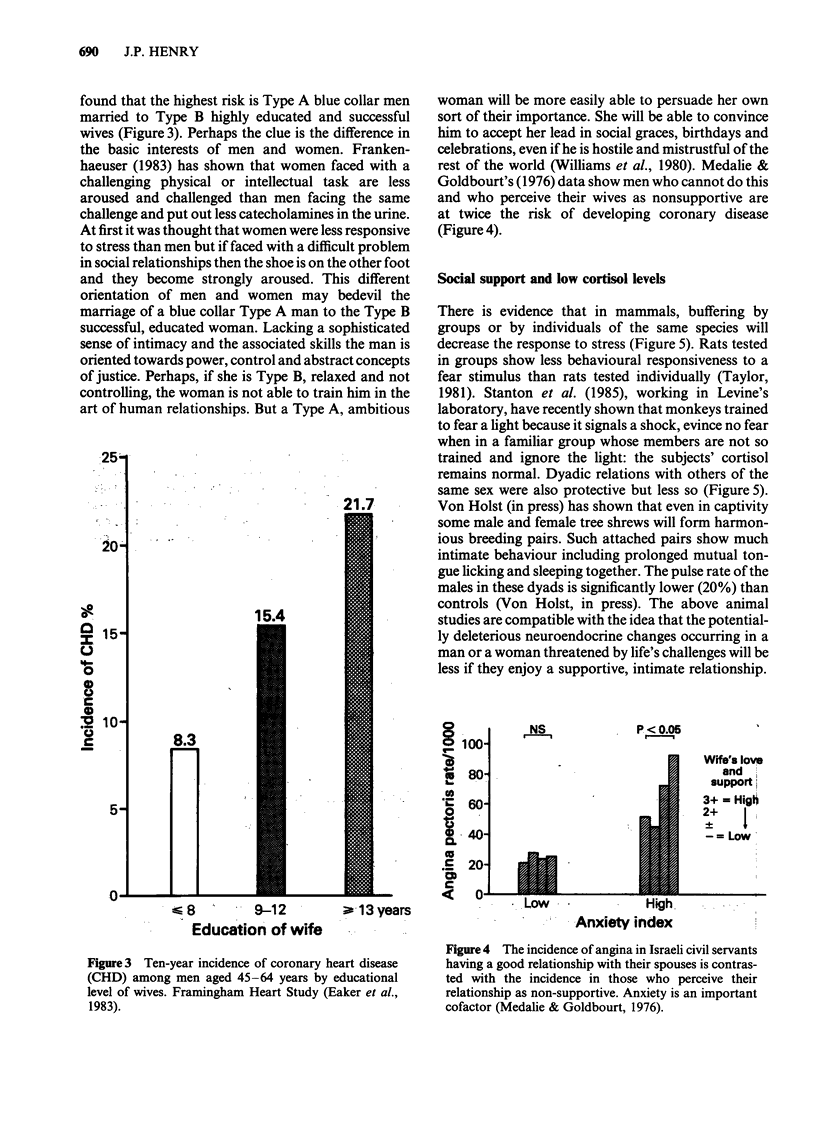

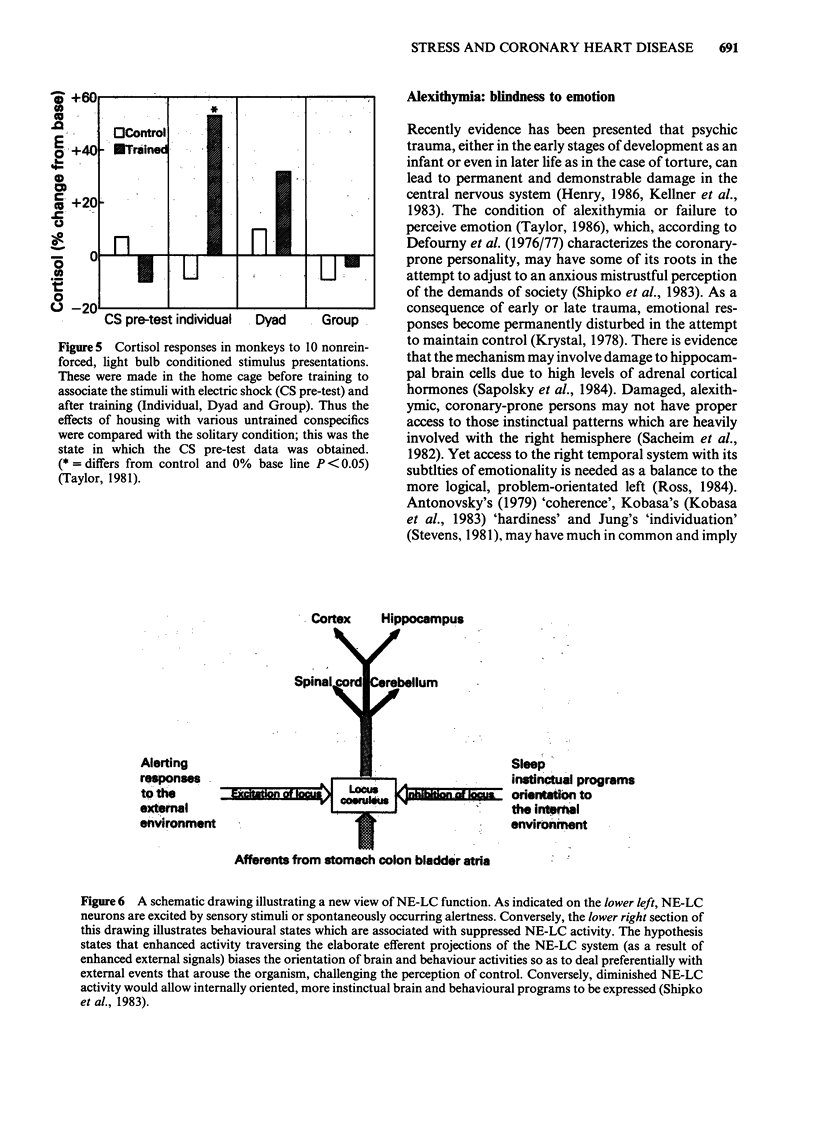

Much stress is of psychological origin and due to emotional arousal. The mechanisms by which anger, helplessness, or a sense of control and serenity exert their various neuroendocrine effects are discussed. Primacy is given to three systems; to the catecholamines, to testosterone and to cortisol. Evidence that they interact to accelerate the arteriosclerotic process is cited. The protective aspects of intimacy are discussed together with evidence that certain personality types promote it in the marital situation while others do not. It is suggested that the post-traumatic stress syndrome may relate to the coronary-prone personality for it involves an alexithymic disturbance of the emotional competence required for successful intimacy.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Carmelli D., Swan G. E., Rosenman R. H. The relationship between wives' social and psychologic status and their husbands' coronary heart disease. A case-control family study from the Western Collaborative Group Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1985 Jul;122(1):90–100. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Defourny M., Hubin P., Luminet D. Alexithymia, 'pensée opéatoire' and predisposition to coronopathy. Pattern 'A' of Friedman and Rosenman. Psychother Psychosom. 1976;27(2):106–114. doi: 10.1159/000287004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eaker E. D., Haynes S. G., Feinleib M. Spouse behavior and coronary heart disease in men: prospective results from the Framingham heart study. II. Modification of risk in type A husbands according to the social and psychological status of their wives. Am J Epidemiol. 1983 Jul;118(1):23–41. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry J. P. The relation of social to biological processes in disease. Soc Sci Med. 1982;16(4):369–380. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(82)90047-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krystal H. Trauma and affects. Psychoanal Study Child. 1978;33:81–116. doi: 10.1080/00797308.1978.11822973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manuck S. B., Kaplan J. R., Clarkson T. B. Social instability and coronary artery atherosclerosis in cynomolgus monkeys. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 1983 Winter;7(4):485–491. doi: 10.1016/0149-7634(83)90028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazur A., Lamb T. A. Testosterone, status, and mood in human males. Horm Behav. 1980 Sep;14(3):236–246. doi: 10.1016/0018-506x(80)90032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Medalie J. H., Goldbourt U. Angina pectoris among 10,000 men. II. Psychosocial and other risk factors as evidenced by a multivariate analysis of a five year incidence study. Am J Med. 1976 May 31;60(6):910–921. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(76)90921-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose R. M., Berstein I. S., Gordon T. P. Consequences of social conflict on plasma testosterone levels in rhesus monkeys. Psychosom Med. 1975 Jan-Feb;37(1):50–61. doi: 10.1097/00006842-197501000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sackeim H. A., Greenberg M. S., Weiman A. L., Gur R. C., Hungerbuhler J. P., Geschwind N. Hemispheric asymmetry in the expression of positive and negative emotions. Neurologic evidence. Arch Neurol. 1982 Apr;39(4):210–218. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1982.00510160016003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sapolsky R. M., Krey L. C., McEwen B. S. Stress down-regulates corticosterone receptors in a site-specific manner in the brain. Endocrinology. 1984 Jan;114(1):287–292. doi: 10.1210/endo-114-1-287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton M. E., Patterson J. M., Levine S. Social influences on conditioned cortisol secretion in the squirrel monkey. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1985;10(2):125–134. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(85)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor G. J. Alexithymia: concept, measurement, and implications for treatment. Am J Psychiatry. 1984 Jun;141(6):725–732. doi: 10.1176/ajp.141.6.725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P. D., Goodwin J. M., Goodwin J. S. Effect of social support on stress-related changes in cholesterol level, uric acid level, and immune function in an elderly sample. Am J Psychiatry. 1985 Jun;142(6):735–737. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.6.735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams R. B., Jr, Haney T. L., Lee K. L., Kong Y. H., Blumenthal J. A., Whalen R. E. Type A behavior, hostility, and coronary atherosclerosis. Psychosom Med. 1980 Nov;42(6):539–549. doi: 10.1097/00006842-198011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]