Abstract

Regulators of G protein signaling (RGS) proteins limit the lifetime of activated (GTP-bound) heterotrimeric G protein α subunits by acting as GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs). Mutation of two residues in RGS4, which, based on the crystal structure of RGS4 complexed with Giα1-GDP-AlF4−, directly contact Giα1 (N88 and L159), essentially abolished RGS4 binding and GAP activity. Mutation of another contact residue (S164) partially inhibited both binding and GAP activity. Two other mutations, one of a contact residue (R167M/A) and the other an adjacent residue (F168A), also significantly reduced RGS4 binding to Giα1-GDP-AlF4−, but in addition redirected RGS4 binding toward the GTPγS-bound form. These two mutant proteins had severely impaired GAP activity, but in contrast to the others behaved as RGS antagonists in GAP and in vivo signaling assays. Overall, these results are consistent with the hypothesis that the predominant role of RGS proteins is to stabilize the transition state for GTP hydrolysis. In addition, mutant RGS proteins can be created with an altered binding preference for the Giα-GTP conformation, suggesting that efficient RGS antagonists can be developed.

Many of the physiologic effects of heterotrimeric G proteins are determined by their activated (GTP bound) α subunits, which interact with effectors such as adenylyl cyclase and phospholipase Cβ. Conversely, termination of these responses is critically dependent on the rate of deactivation of Gα, which occurs by the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, leading to rebinding to βγ subunits and reformation of inactive heterotrimers (1–3). Isolated Gα subunits are relatively poor catalysts, yet their in vivo rates of GTP hydrolysis may be 100-fold faster, suggesting that GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) accelerate the rate of hydrolysis of GTP (4–5). A newly discovered family of regulators of G protein signaling (RGS proteins) are GAPs for the Gi and Gq subfamilies of Gα subunits (4, 6–10). RGS1, RGS4, and Gα interacting protein (GAIP), three of the best characterized family members, bind with high affinity to the GDP-AlF4− activated forms of Giα1–3, Goα, and Gqα, a conformation thought to mimic the pentavalent transition state complex of the GTPase reaction (11, 12), and accelerate the intrinsic rate of GTP hydrolysis at least 40-fold.

Recent crystallization of RGS4 complexed with Giα1-GDP-AlF4− has shown that the highly conserved 120-aa RGS box (also referred to as RGS domain) forms a four-helix bundle that directly contacts the Giα surface at the three so-called “switch regions,” which undergo the greatest conformational change during the GTPase cycle and contain residues critical for GTP hydrolysis (13). Specific amino acids in RGS4 appear to stabilize these switch residues in the transition state through noncovalent interactions.

Consistent with these studies, we show here that the degree to which RGS4 binds to Giα1-GDP-AlF4− is directly proportional to its GAP activity. Mutation of two residues (R167 and F168) results in minimal residual binding to GDP-AlF4−-Giα1, but the mutant proteins bind preferentially to the GTPγS-bound form and have markedly impaired GAP activity. Most importantly, these two mutant proteins display a dominant negative phenotype, inhibiting both wild-type RGS4 and GAIP in both in vitro and in vivo assays.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Generation of RGS4 Mutants.

PCR primers were designed to generate overlapping products encompassing the designated mutation. These fragments were separated by electrophoresis on a 1% low melting point agarose gel and then purified from the gel by phenol extraction. The PCR products then were used as the template for a second PCR with primers designed to generate the entire coding region of the published RGS4 cDNA flanked by BamHI/XhoI sites. The fragments then were subcloned into the corresponding sites of pCDNA3, modified to include three successive hemagglutinin epitopes of influenza virus (HA) (YPYDVPDYA) in-frame with the C terminus of the insert (pcDNA3-HA3). Constructs were verified at the cloning junction and through the mutated regions by automated nucleotide sequencing.

Protein Preparation.

The mammalian expression plasmids were used to generate PCR fragments flanked by NdeI/XhoI sites that were subcloned into the corresponding sites of the bacterial expression vector pET15b (Novagen) in-frame with an N-terminal hexahistidine tag. These plasmids were transformed into the bacterial strain BL21(DE3) and induced with 1 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactoside. His-tagged proteins were purified by chromatography on Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Qiagen), dialyzed vs. 50 mM Tris, pH 8/380 mM NaCl/1 mM DTT/10% glycerol, and stored at −70°C. Recombinant His6MKK used as a negative control protein was provided by Heidrun Ellinger-Ziegelbauer, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health.

G Protein Binding Assays.

Binding of purified G-protein α subunits to RGS4 mutants was performed as described with minor modifications (4). Briefly, 2 μg of purified recombinant, myristoylated Giα1 (Calbiochem) was activated in buffer A (50 mM Tris, pH 8/100 mM NaCl/1 mM MgSO4/20 mM imidazole/0.025% C12E10/10% glycerol) containing 30 μM GDP or 30 μM AlCl3 plus 10 mM NaF and 30 μM GDP or 30 μM GTPγS at 30°C for 30 min. RGS4 or one of the mutant RGS4 proteins (5 μg) was added to the reaction for 30 min on ice. Fifty microliters of Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads previously equilibrated in buffer A was added for an additional 20 min at room temperature. The beads were washed once with buffer A and then bound proteins were eluted in SDS sample buffer and boiled for 5 min. The entire recovered amount in each eluted fraction was separated on a 10% SDS gel and immunoblotted for Giα with an affinity-purified antiserum against Giα1–2 (AS/7, the kind gift of Allen Spiegel and Paul Goldsmith, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health) and an affinity-purified antiserum against a C-terminal human RGS4 peptide (CASLVPQCA).

Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK) Assays.

Measurements of MAPK activity in 6E cells [293 cells stably transfected with the human interleukin (IL)-8 receptor A stimulated by IL-8] were performed as described (14). Cells were transfected with an HA-ERK1 plasmid (2 μg) and 5 μg of empty vector or RGS4 plasmid by the calcium phosphate method and harvested after 48 hr. The cells were stimulated with IL-8 (Endogen, 25–50 ng/ml) for 3 min and processed as described. MAPK activity was measured by the incorporation of [γ32]ATP into myelin basic protein by fractionation on 10% SDS gels and autoradiography. The upper portion of the gels was immunoblotted with an HA antibody (12CA5, Babco, Richmond, CA) to control for ERK1 levels.

Measurement of GAP Activity.

Measurements of kcat for GTP hydrolysis were performed essentially as described (4). Recombinant, myristoylated Giα1 (Calbiochem, 50 nM) was loaded with [γ32P]GTP (20,000 cpm/pmol) in 800 μl of buffer C (50 mM Hepes, pH 8/5 mM EDTA/1 mM DTT/0.1% C12E10) for 30 min at 30°C. MgSO4 (10 mM) in the presence or absence of RGS protein was added at 4°C to initiate GTP hydrolysis. Fifty-microliter aliquots were removed at the indicated times, added to 750 μl of 5% Norit A/50 mM NaH2PO4, processed, and counted by liquid scintillation spectrometry.

RESULTS

Amino Acids In The Region Between Residues 88 And 168 Are Critical For Inhibition Of G-Protein-Mediated MAPK Activation In Vivo.

The approximately 120-aa region of RGS proteins designated the RGS box has been shown to directly contact the Gα interface and to be sufficient for GAP activity (15, 16). We hypothesized that mutation of one or more of the most highly conserved residues in the RGS box would alter RGS4 Gα binding and/or GAP activity. By using a PCR-based, site-directed mutagenesis method, we generated 13 point mutants, all of which were located within residues 80–168 of RGS4 (Fig. 1). Each of the mutant RGS4 proteins was epitope-tagged to allow the verification of protein expression levels. We screened the mutant RGS4 proteins initially for their ability to inhibit MAPK activation by IL-8 in 293 cells transfected with the IL-8 receptor (6E cells). IL-8 is a prototypical chemokine that signals through a heptahelical receptor linked to Giα2 (17, 18). We previously have shown that transient overexpression of RGS proteins in these cells inhibits IL-8-induced MAPK activation (14). Of the 13 RGS4 mutant proteins, seven of them (L80G, E87K, K99E, K100E, F149A, Q153S, and M160L) impaired IL-8-induced MAPK activation in a manner similar to wild-type RGS4, indicating that these residues are not critical for RGS4 function in this assay system (data not shown). The other six mutant RGS4 proteins (N88S, L159F, S164Q, R167M, R167A, and F168A) had little or no activity compared with wild-type RGS4 (Fig. 2A and data not shown), suggesting that these residues are important for RGS4 function. To eliminate the possibility that malfunction of the mutant proteins was not simply caused by gross misfolding and subsequent aggregation, we compared protein levels of the mutants to wild type in cytosolic fractions after high-speed centrifugation. 293T cells were transfected with wild-type or mutant plasmids; the cells were lysed hypotonically without detergent and then centrifuged at 100,000 × g to pellet insoluble proteins. The supernatant and pellet fractions were separated by SDS/PAGE and then immunoblotted with an anti-HA antibody, and no substantive difference in solubility was noted among the various mutant proteins (data not shown).

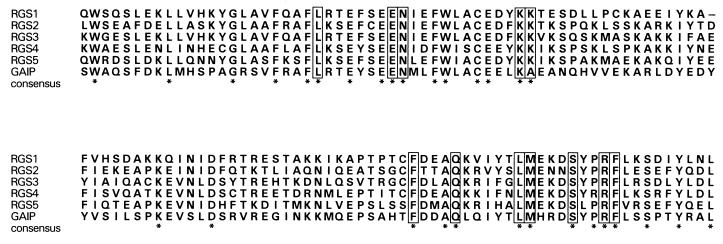

Figure 1.

Alignment of the RGS domains and the conserved residues selected for mutation. Twelve of the most conserved residues (across mammalian RGS proteins and invertebrate homologs) were mutated by site-directed mutagenesis (boxes). ∗ indicate other conserved amino acids among mammalian RGS proteins.

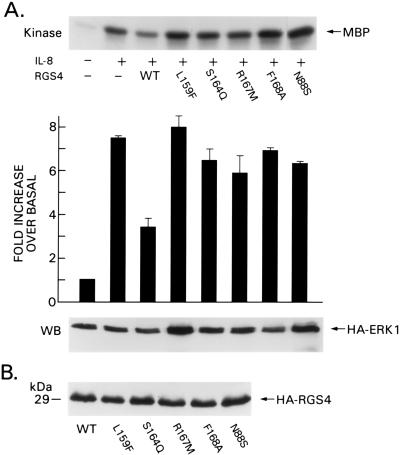

Figure 2.

Five RGS4 mutant proteins do not inhibit G-protein-mediated MAPK activation. (A) Mammalian expression plasmids containing RGS4 or RGS4 mutant proteins L159F, S164Q, R167M, F168A, and N88S were transfected into 6E cells. (Upper) MAPK activity is represented by the amount of [γ32P]ATP incorporated into myelin basic protein incubated with HA immunoprecipitates (MBP, above, labeled “kinase”). The average increase in activity over that of unstimulated cells as determined from three independent experiments is shown in the bar graph + SEM. (Lower) The levels of cotransfected HA-ERK1 as determined by immunoblotting the immunoprecipitates used to determine kinase activity with anti-HA (labeled “WB,” below). (B) Levels of indicated mutants were determined by immunoblotting equivalent amounts of cell lysates transfected with HA-tagged RGS4 expression plasmids with the anti-HA antibody.

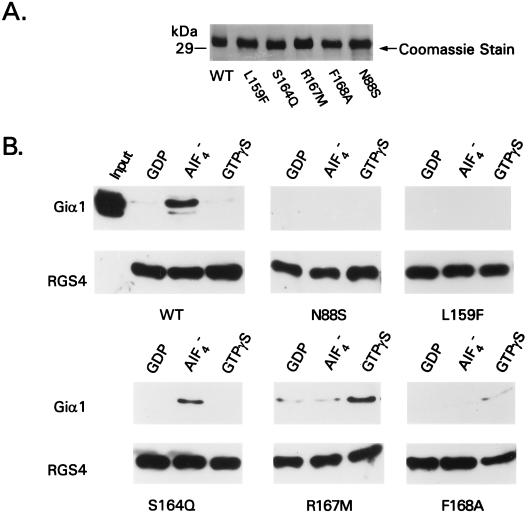

Mutation of Contact Residues at the Active Site of Gα Results in Binding Defects.

Because we suspected that the six nonfunctional mutant proteins in the MAPK assay would be defective in their ability to bind Gα subunits and/or to accelerate Gα GTPase activity, we produced the mutant RGS4 proteins as recombinant, hexahistidine-tagged proteins in bacteria and purified them by chromatography with Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid beads (Fig. 3A). We incubated the immobilized mutant RGS4 proteins with recombinant Giα1 in the presence of GDP alone or activated with either AlF4− or GTPγS, washed away unbound proteins, and analyzed the relative amounts of bound Giα1 by immunoblotting (Fig. 3B). Whereas wild-type RGS4 bound efficiently to Giα1-GDP-AlF4−, both the N88S and L159F mutant RGS4 proteins failed to bind appreciably. The S164Q protein partially retained its ability to bind the AlF4− activated form. As compared with the wild-type protein, the R167M and F168A proteins bound Giα1-GDP-AlF4− with dramatically reduced affinity, but appeared to bind preferentially to the GTPγS bound form (equivalent results were seen with R167A, data not shown).

Figure 3.

Gα binding by RGS4 mutants. (A) Coomassie stain of 5 μg of bacterially expressed RGS4 proteins purified by Ni2+-nitrilotriacetic acid chromatography. (B) Binding of RGS4 mutant proteins to GDP, GDP-AlF4−, or GTPγS-activated Giα1. The input amount of Giα1 and the entire amount of protein eluted from each binding reaction were detected by immunoblotting.

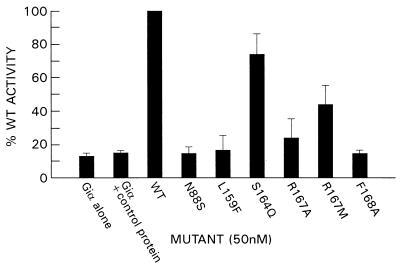

All Six Mutations Result In GAP Defects.

Next, we measured the catalytic activity of the six mutant RGS4 proteins on the hydrolysis of GTP by Giα1 during a single cycle by loading the G protein with labeled GTP in the absence of Mg2+ and then adding Mg2+ simultaneously with RGS protein. GTP hydrolysis was measured for Giα1 alone, in the presence of a control protein, wild-type RGS4, or the six mutant proteins, and is represented by the relative percentage of GTP hydrolyzed per minute by the G protein in the presence of wild-type RGS4 protein (100%; Fig. 4). GTP hydrolysis per minute by Giα1 alone or in the presence of a control protein (His6MKK) was on average 15% of the amount hydrolyzed in the presence of wild-type RGS4. Mutant proteins with the most severe GAP defects also demonstrated the most severe defects in binding to AlF4− activated Giα1. N88S, L159F, and F168A, which showed minimal ability to bind Giα1-GDP-AlF4−, had relative GAP activities of 15%, 17%, and 16% of the wild-type protein, respectively. In contrast, S164Q, which retained some binding ability, demonstrated relatively preserved GAP activity (75% of wild type). Last, R167M and R167A, which bind weakly to both Giα1-GDP-AlF4− and (preferentially) to GTPγS-Giα1, showed an intermediate GAP defect, on average 45% and 25% of the wild type, respectively.

Figure 4.

RGS4 mutants show diminished GAP activity. The amount of GTP hydrolyzed per minute by Giα1 in the presence of wild-type RGS4 was determined as outlined in Materials and Methods. The GAP activity of each mutant protein is represented as a percentage of the amount of GTP hydrolyzed by Giα1 in the presence of wild-type RGS4 (100%). Data represent the average of 2–3 independent experiments.

R167A, R167M, and F168A Act as Antagonists of Wild-Type RGS Proteins In Vitro and In Vivo.

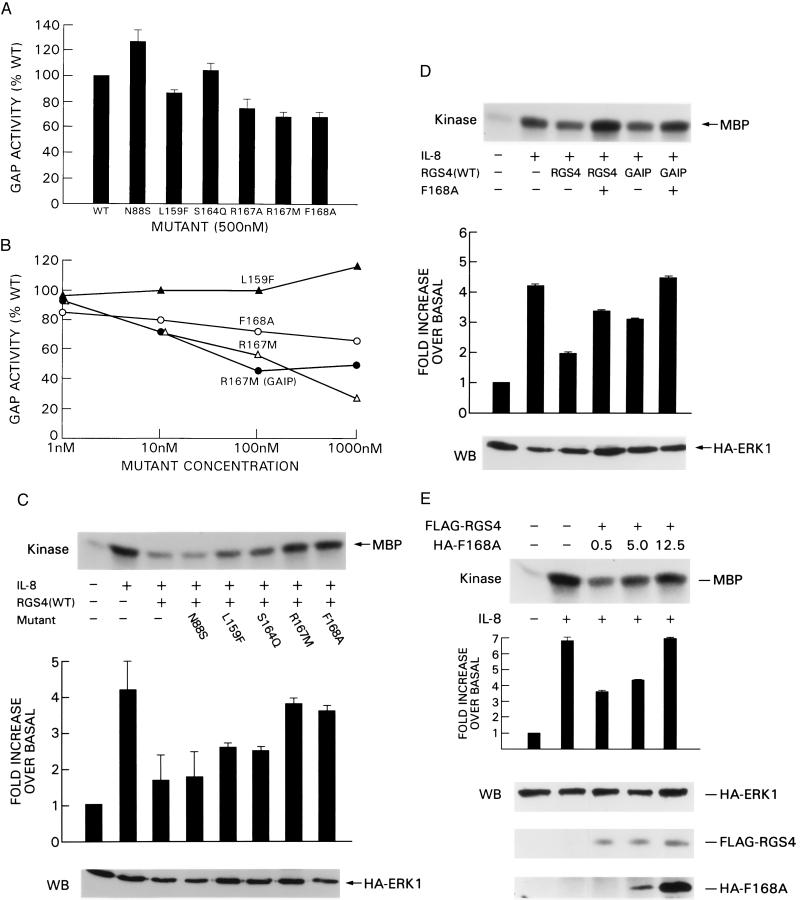

Next, we tested to see if any of the mutant proteins could antagonize wild-type RGS4 by measuring the GAP activity of wild-type RGS4 in the presence of a 10-fold molar excess of mutant protein. As shown in Fig. 5A, GAP activity of 50 nM RGS4 was not significantly inhibited by 500 nM N88S (128% of wild type), L159F (87%), or S164Q (105%). In contrast, the GAP activity of RGS4 was decreased 25% by 500 nM R167A and 32% by either R167M or F168A.

Figure 5.

Two mutants antagonize the activity of wild-type RGS4 and GAIP. (A) A 10-fold excess of mutant protein (500 nM) was added simultaneously with wild-type RGS4, and GTP hydrolysis by Giα1 was measured as previously. GTP hydrolyzed per minute by the G protein is represented in the bar graph as a percentage of the amount of GTP hydrolyzed in the presence of wild-type RGS4 alone (100%). Each experiment was repeated twice. (B) The GAP activity of wild-type RGS4 (or GAIP, as indicated) was determined in the presence of the indicated concentration of each mutant. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) F168A antagonizes the inhibition of IL-8-induced MAPK activation by RGS4 in vivo. A 5-fold excess of mutant plasmid over wild-type RGS4 was cotransfected into 6E cells, and MAPK activity was determined as previously described. Bar graph data represent the average value from 2–3 independent experiments. (D) F168A antagonizes the activity of both RGS4 and GAIP. In vitro kinase activity of HA immunoprecipitates from cells cotransfected with HA-ERK1, wild-type RGS4 or GAIP, and a 5-fold excess of F168A were determined as described in previous figures. Similar results were obtained with R167M or R167A. (E) Dose–response effect of increasing amounts of F168A. A constant amount of FLAG-RGS4 plasmid and increasing amounts of HA-F168A plasmid were coexpressed in 6E cells, and the in vitro kinase activity of MAPK after ligand stimulation was measured as described. Bar graph data represent two independent experiments. (Lower) Blots of cell lysates probed for ERK 1 (HA blot, Top), wild-type RGS4 (FLAG blot, Middle), and F168A (HA blot, Bottom).

To confirm this observation, we tested the GAP activity of RGS4 and GAIP in the presence of a range of concentrations of the mutants (Fig. 5B). L159F had little effect on the GAP activity of RGS4 over a 1 nM to 1 μM concentration range. In contrast, 1 μM R167M and 1 μM F168A significantly inhibited the GAP activity of RGS4 (decreased by 72% and 34%, respectively). This in vitro effect was confirmed further by measuring the inhibition of IL-8-induced MAPK activation in IL-8R-expressing 293 cells by wild-type RGS4 in the presence of the mutants. Whereas cotransfection of a 5-fold excess of either N88S, L159F, or S164Q plasmids with RGS4 did not significantly inhibit the activity of RGS4 in this assay, the presence of either R167M, R167A, or F168A resulted in MAPK activation nearly to the level of stimulated cells that did not contain RGS4 (Fig. 5C and data not shown), indicating that the mutant proteins partially counteracted the effect of wild-type RGS4. A similar inhibition of wild-type GAIP by R167M, R167A, and F168A was observed (Fig. 5D and data not shown). Finally, we cotransfected equivalent amounts of wild-type FLAG-RGS4 and increasing amounts of HA-F168A in the IL-8R-bearing cells, stimulated with ligand, and measured MAPK activation. As shown in Fig. 5E, wild-type RGS4 was progressively inhibited by increasing amounts of F168A protein as demonstrated by increased MAPK activation.

DISCUSSION

In this study we have shown that five highly conserved residues in the RGS domain are essential for the normal function of RGS4 protein as assessed by binding to heterotrimeric G protein α subunits, catalytic activity in GAP assays, and inhibition of G-protein-linked MAPK activation in vivo. In particular, mutation of R167 or F168 in RGS4 resulted in decreased affinity for AlF4−-activated Giα1 but increased binding to the GTPγS bound form compared with the wild type, diminished GAP activity, and the ability to antagonize wild-type RGS proteins in GTPase and MAPK assays. These data suggest that stabilization of the transition state complex (Giα1-GDP-AlF4−) of the GTPase reaction is the primary mechanism of action of RGS proteins because disruption of contact residues that results in poor binding to this form of Giα1 also leads to partial or complete ablation of GAP activity. We hypothesize that mutants that bind preferentially to GTP-bound Gα inhibit the GAP activity of the wild-type protein most likely by slowing formation of the transition state complex and inhibiting reduction of the activation energy barrier for GTP hydrolysis.

Examination of the crystal structure of RGS4 complexed with Giα1-GDP-AlF4− reveals that four of five loss-of-function mutants presented in this study involve residues that make direct contact with the active site of Giα1, and the fifth, F168, is immediately adjacent to a contact residue. The RGS box containing these conserved residues is essential and sufficient for GAP activity in vitro (16). This domain consists of a series of nine α-helices that cluster into two subdomains, one containing the N- and C-termini of the RGS box and the other an antiparallel four-helix bundle. The base of the bundle is situated to create a pocket for substrate binding; three distinct loci along the bottom of the bundle form a discontinuous interaction surface along the three “switch” regions of Giα1. The switch regions of the ras-like domain of Giα, which undergo a relatively large conformational change during the GTPase cycle, are thought to play a critical role in GTP hydrolysis (11, 12).

The highly conserved Thr-182 of Giα1 undergoes the largest change in accessible surface area on RGS binding as seven highly conserved amino acids in RGS4 (S85, E87, N88, L159, D163, S164, and R167) encircle this residue. Our data suggest that N88, L159, and R167 are critical for formation of the Thr-182 binding pocket whereas E87 and S164 are less important. Although F168 does not make direct contact with the Giα1 surface, its mutation may result in disruption of interactions between proximate residues that do contact the interface and thus destabilize the hydrophobic core of the RGS box. Although these specific stereochemical interpretations may be speculative, our data demonstrating diminution or loss of binding to AlF4− activated Giα1 argue for the importance of these five residues in maintaining the transition state conformation.

Examination of the crystal structure of Ras-RasGAP-AlF3 now has demonstrated that the GAP sits on the switch regions of the GTPase domain of Ras, resulting in direct catalysis not only by reorientation of residues that stabilize the transition state but also by stabilization of developing charges in the complex (19, 20). In contrast, none of the contact residues in RGS4 appears poised to contribute catalytically to the GTPase reaction, with the exception of N128, which projects into the active site of Giα1 through interactions with the side chains of Q204, S206, and G207 and forms a putative hydrogen bond with the attacking water molecule (13). None of the residues outlined in this study interacts directly with Giα1 residues in this active site, or with GDP, AlF4−, or H2O, implying that their primary role is to stabilize the transition complex. Analysis of Giα1-GDP-AlF4− with and without RGS4 suggests that the switch regions are more rigid in the presence of RGS4 (13). This lack of flexibility of the switch residues in the presence of RGS4 implies that the function of the RGS proteins is to trap the Gα subunit in a distinct conformation—that is, a transition state that facilitates nucleophilic attack of a water molecule on the γ phosphate of GTP. Thus, it is not surprising that mutation of residues in RGS4 such as R167 and F168, which disrupts the preference of RGS4 for the transition state but results in retention and/or enhancement of binding to the GTP-bound form of the α subunit, might impede lowering the energy barrier for GTP hydrolysis by a wild-type RGS protein. However, because the amount of binding of R167A/M and F168A does not strictly correlate with the strength of reduction of RGS4’s ability to down-regulate signaling in vivo, we cannot rule out the possibility of another operative mechanism by which these mutants exert a dominant negative effect. Because R167M and F168A also bind weakly to the AlF4− form and have some GAP activity, this binding may partially offset their inhibitory effects in in vitro GAP assays, an effect that may be less apparent in intact cells. Nevertheless, binding of the mutant proteins to the GTP-bound form in the presence of the wild-type protein is apparently sufficient to significantly inhibit wild-type GAP activity. In theory, mutation of other residues in RGS4 or synthesis of compounds that bind exclusively to the GTP-Giα1 might significantly slow or abolish the hydrolysis of GTP by Giα. Such compounds would be predicted to prevent α subunit effector activation and impair sequestration of βγ subunits.

Besides antagonizing RGS4 and GAIP GAP activity, the R167A/M and F168A mutant RGS4 proteins inhibited the activity of several RGS proteins (RGS1, RGS4, and GAIP) in vivo. There is also the suggestion that these mutant proteins may inhibit other endogenous RGS proteins present in the transfected cells, as we often noted an enhanced response to the G protein-mediated signal in vivo. If so, these mutants may be potentially used to silence the effect of numerous RGS proteins in a given cell to various physiological stimuli.

Acknowledgments

We thank Gaye Lynn Wilson and Kathy Harrison for technical assistance, Mary Rust for editorial assistance, Allen Spiegel for a critical discussion of the manuscript, and A. S. Fauci for his support.

Footnotes

This paper was submitted directly (Track II) to the Proceedings Office.

Abbreviations: RGS, regulator of G protein signaling; GAP, GTPase activating protein; GAIP, Gα interacting protein; MAPK, mitogen-activated protein kinase; HA, hemagglutinin epitope of influenza virus; IL, interleukin.

References

- 1.Neer E J. Cell. 1995;80:249–257. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90407-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kleuss C, Raw A S, Lee E, Sprang S R, Gilman A G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9828–9831. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.21.9828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bourne H R, Sanders D A, McCormick F. Nature (London) 1991;349:117–126. doi: 10.1038/349117a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watson N, Linder M E, Druey K M, Kehrl J H, Blumer K J. Nature (London) 1996;383:172–175. doi: 10.1038/383172a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berstein G, Blank J L, Jhon D-Y, Exton J H, Rhee S G, Ross E M. Cell. 1992;70:411–418. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90165-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Berman D M, Wilkie T M, Gilman A G. Cell. 1996;86:445–452. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80117-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hepler J R, Berman D M, Gilman A G, Kozasa T. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:428–432. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berman D M, Kozasa T, Gilman A G. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27209–27212. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dohlman H G, Thorner J. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:3871–3874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.7.3871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hunt T W, Fields T A, Casey P J, Peralta E G. Nature (London) 1996;12:175–177. doi: 10.1038/383175a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sondek J, Lambright D G, Noel J P, Hamm H E, Sigler P B. Nature (London) 1994;372:276–279. doi: 10.1038/372276a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coleman D E, Berghuis A M, Lee E, Linder M E, Gilman A G, Sprang S R. Science. 1994;265:1405–1411. doi: 10.1126/science.8073283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tesmer J J G, Berman D M, Gilman A G, Sprang S R. Cell. 1997;89:251–261. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80204-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Druey K M, Blumer K J, Kang V H, Kehrl J H. Nature (London) 1996;379:742–746. doi: 10.1038/379742a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeVries L, Mousli M, Wurmser A, Farquhar M G. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:11916–11920. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.25.11916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Popov S, Yu K, Kozasa T, Wilkie T M. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:7216–7220. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murphy P M, Tiffany H L. Science. 1991;253:1280–1283. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.VanLint J. Mol Cell Biochem. 1993;127:171–177. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sprang S R. Science. 1997;277:329–330. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheffzek K, Ahmadian M R, Kabsch W, Wiesmueller L, Lautwein A, Schmitz F, Wittinghofer A. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]