Abstract

The type 3 deiodinase (D3) inactivates thyroid hormone action by catalyzing tissue-specific inner ring deiodination, predominantly during embryonic development. D3 has gained much attention as a player in the euthyroid sick syndrome, given its robust reactivation during injury and/or illness. Whereas much of the structure biology of the deiodinases is derived from studies with D2, a dimeric endoplasmic reticulum obligatory activating deiodinase, little is known about the holostructure of the plasma membrane resident D3, the deiodinase capable of thyroid hormone inactivation. Here we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer in live cells to demonstrate that D3 exists as homodimer. While D3 homodimerized in its native state, minor heterodimerization was also observed between D3:D1 and D3:D2 in intact cells, the significance of which remains elusive. Incubation with 0.5–1.2 m urea resulted in loss of D3 homodimerization as assessed by bioluminescence resonance energy transfer and a proportional loss of enzyme activity, to a maximum of approximately 50%. Protein modeling using a D2-based scaffold identified potential dimerization surfaces in the transmembrane and globular domains. Truncation of the transmembrane domain (ΔD3) abrogated dimerization and deiodinase activity except when coexpressed with full-length catalytically inactive deiodinase, thus assembled as ΔD3:D3 dimer; thus the D3 globular domain also exhibits dimerization surfaces. In conclusion, the inactivating deiodinase D3 exists as homo- or heterodimer in living intact cells, a feature that is critical for their catalytic activities.

T4 IS A MINIMALLY ACTIVE hormone secreted by the thyroid gland that must be monodeiodinated to T3 to gain full biological activity. T3 binds to thyroid hormone receptors, which are well-characterized ligand-mediated transcription factors that control the expression of genes involved in development, growth, and energy homeostasis in vertebrates (1,2). T4 activation is catalyzed by the types 1 (D1) or 2 (D2) iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. At the same time, thyroid hormone action can be terminated by inner-ring monodeiodination of T3 or T4, a pathway that is catalyzed by the type 3 deiodinase (D3) with some D1 contribution as well. Both the activating and inactivating pathways are homeostatic mechanisms, adjusting T3 production and catalysis in response to stressors such as iodine deficiency, starvation, or cold exposure (3,4), as well as a high-fat diet (5).

The deiodinases are the products of three different genes, and each enzyme has distinct substrate affinities and physiological roles (6). Whereas all three deiodinases are known to be integral membrane proteins with a single transmembrane domain within the first 30–40 amino-terminal residues (7,8,9), there are clear differences with respect to their molecular and catalytic properties (3,10,11,12). Unique among the deiodinases, D3 has no introns and has recently been found to be paternally imprinted (13). D3 (molecular mass, 32 kDa) recycles between the plasma membrane and the early endosomes, with a less clear orientation. Whereas immunofluorescence and biotinylation studies indicate a catalytic globular domain located in the extracellular space (14), functional data indicate that D3-mediated catalysis takes place inside the cell (15). At the same time, it is clear that D1 also resides in the plasma membrane (catalytic globular domain in the cytosol) (7,8) and D2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-resident protein (catalytic globular domain in the cytosol) (8).

Early attempts to purify the deiodinases identified activity in higher molecular weight forms than predicted from their respective deduced amino acid sequences (16,17). Subsequent studies using three different approaches confirmed that D1, D2, and D3 form homodimers (18). The evidence includes identification of monomeric bands for each deiodinase by Western blot analysis along with additional higher molecular weight bands of appropriate size for a putative dimeric enzyme, coimmunoprecipitation of 75Se- and FLAG-tagged deiodinases using anti-FLAG antibodies, and immunodepletion of D1 and D2 activities from lysates of cells coexpressing inactive FLAG-tagged deiodinase and the respective unflagged wild-type enzymes (D1 or D2). D1 and D2 dimerization was confirmed by other groups in subsequent studies (19,20,21).

Recently, we used fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) and bioluminescence fluorescence energy transfer (BRET) to study D2 dimerization in live human embryonic kidney (HEK)-293 cells (22). Upon binding of T4, its natural substrate, D2 is ubiquitinated, which inactivates the enzyme by interfering with D2’s globular interacting surfaces that are critical for dimerization and catalytic activity (22).

Discovering this mechanism of D2 inactivation led us to consider the possibility that homodimerization of D3, the deiodinase capable of thyroid hormone inactivation, might also modulate its enzymatic activity. In the present investigation, we show that D3 and D1, the other deiodinases capable of thyroid hormone inactivation, also exist as homodimers maintained by transmembrane and globular interacting surfaces, and that there is a small degree of heterodimerization between D3 and the other two deiodinases. Dimerization is thus a shared regulatory mechanism for the activating and inactivating deiodinases.

RESULTS

FRET and BRET Reveal Deiodinase Homo- and Heterodimerization

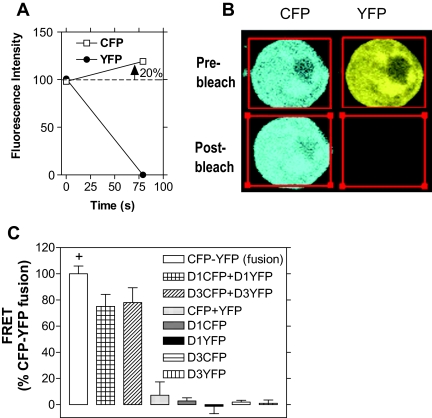

Transient expression of the fused cyan fluorescent protein (CFP)-yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) resulted in about 20% increase in CFP emission following YFP photobleach (Fig. 1, A and B), a value well above the limit of detection for this technique, estimated at 3–4% (23). For the purpose of standardizing the results, in each experiment the FRET signal obtained with the fused CFP-YFP was assigned a value of 100%, and signal values below 20% were considered background. Although the focus of the present studies was on D3, as much as possible we also included D1 and D2 in the experiments to compare and contrast the deiodinase properties. The signal obtained in cells expressing only CFP and YFP, or either chromophore-fused D3 or -D1 alone, common negative controls used in these kinds of studies, remained well below 20% (Fig. 1C). At the same time, coexpression of CFP- and YFP-fused deiodinases resulted in a strong whole-cell FRET signal, reaching approximately 75% of the positive control (Fig. 1C). Whereas in these experiments both deiodinases were found in the plasma membrane (14), some expression was also noted intracellularly (Fig. 2, A and B). However, FRET remained strong regardless of whether the cell area analyzed contained only plasma membrane or the whole cell (data not shown), the latter being performed throughout the study.

Figure 1.

FRET in Live Deiodinase-Expressing HEK-293 Cells

A, CFP and YFP emission intensity during YFP photobleach in cells transiently expressing a CFP-YFP fusion protein. As the YFP signal decreases, there is an about 20% increase in absolute CFP emission. Representative photomicrographs of such cells are shown in panel B. C, Whole-cell FRET signal in HEK-293 cells transiently expressing D1 or D3 tagged with the appropriate chromophores fused to the C terminus. For reference, the approximately 20% increase in absolute CFP emission of the positive control (+) after photobleach is plotted as 100%. CFP- and YFP-fused deiodinases resulted in a strong FRET signal, reaching approximately 75% of the positive control. All appropriate negative controls exhibit negligible FRET signal. s, Seconds.

Figure 2.

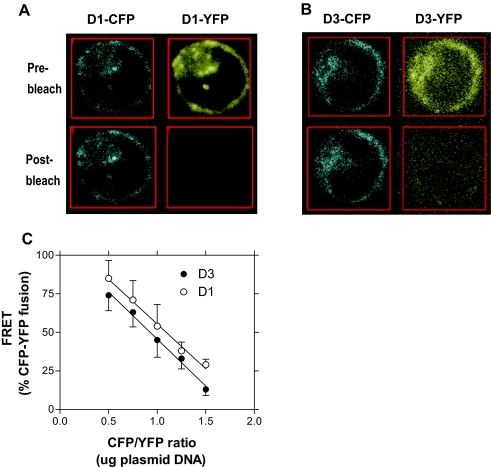

Representative Photomicrographs of Live HEK-293 Cells Coexpressing D1-CFP and D1-YFP (A) or D3-CFP and D3-YFP (B)

C, Dependence of FRET signal on the ratio of donor/acceptor transfected plasmid.

To validate the specificity of the FRET data, we studied energy transfer between the D3 dimer while varying the amount of plasmid DNA transfected. FRET signal for both D3 and D1 is maximal when the donor/acceptor (deiodinase-CFP/deiodinase-YFP) ratio is about 0.5 (1 μg/2 μg plasmid DNA), and decrease thereafter with the increase in this ratio (Fig. 2C). In addition, replotting of the data indicate that FRET signal for both deiodinases was independent of acceptor (YFP) expression levels (data not shown). Both findings indicate that FRET resulted from deiodinase dimerization and not from overexpression of randomly distributed molecules, densely packed in the proximity of one another as a result of overexpression (23). Thus, these amounts of plasmid DNA were used in all subsequent FRET studies if not indicated otherwise.

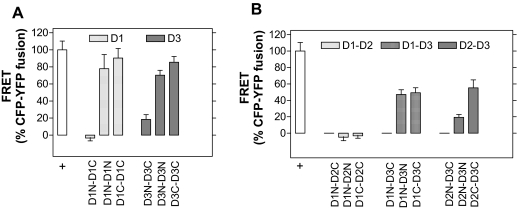

FRET signal was readily detected if the cells expressing D3 (or D1) fused to the appropriate chromophores (CFP or YFP) in the same orientation, either amino (N) or carboxyl (C) (Fig. 3A). However, if the cells expressed deiodinases fused to chromophores in the opposite termini, energy transfer decreased dramatically. For D3, coexpression of D3N and D3C consistently resulted in much low, but higher than background, energy transfer, at about 20% of the positive control (Fig. 3A). For D1, coexpression of CFP-D1 fused to the N terminus (D1N) and YFP-D1 fused to the C terminus (D1C) resulted in background FRET levels (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Homo- and Heterodimerization of Deiodinases

A, FRET studies as in Fig. 1, in which different combinations of chromophore-fused deiodinases were used. CFP or YFP was fused to either the N or C termini of D1 and D3 and transfected as indicated. B, Same as in panel A, except that D1-D2, D1-D3, or D2-D3 proteins were coexpressed; values are the mean ± sd of five to 91 cells.

We coexpressed different pairs of appropriately chromophore-fused deiodinases to test for deiodinase heterodimerization. Whereas coexpression of D1 and D2 did not result in a measurable FRET signal, D3 exhibited a strong tendency of heterodimerization with either D1 or D2, generating energy transfer at about 40% of the positive control (Fig. 3B). Notably, the FRET signal for the D2:D3 heterodimer was stronger when the chromophores were fused to the C terminus of both deiodinases (Fig. 3B).

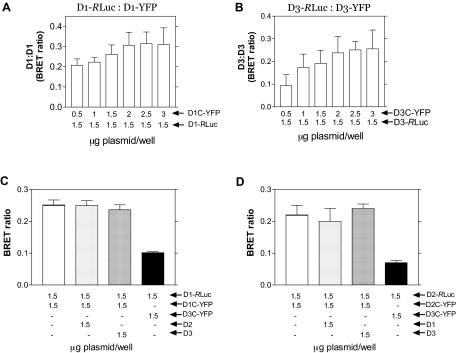

Next, BRET was used to study cells transiently expressing deiodinases fused to Renilla luciferase (RLuc) or YFP. Homodimerization was evident for D3 and D1, as the BRET ratio reached values between 0.2–0.3 (Fig. 4, A and B). Transfection with increasing amounts of YFP-deiodinase (D3 or D1) plasmid DNA progressively increased energy transfer, up to a maximum when 2.0 μg of plasmid DNA was used (Fig. 4, A and B). As with the FRET studies, measurable D3:D1 and D3:D2 heterodimerization was detected, but the D1:D1 and D2:D2 dimers were not affected by overexpression of other deiodinases, indicating a preference for homodimerization (Fig. 4, C and D).

Figure 4.

BRET in Deiodinase-Expressing HEK-293 Cells

A, BRET ratios in cells coexpressing D1-RLuc − D1C-YFP cells were transfected with the indicated amounts of plasmid DNA and studied 36–48 h later. B, Same as in A, except that D3-RLuc − D3C-YFP constructs were used. C and D, Same as in A, and the combinations and amounts of plasmids used are indicated; values are the mean ± sd of five to seven samples.

Transmembrane Surfaces Are Involved in D3 Homodimerization

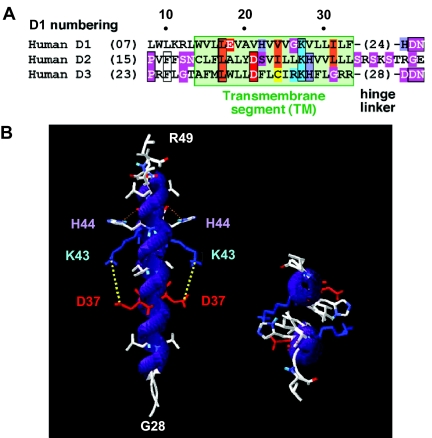

In D3, the predicted transmembrane segments correspond to typical transmembrane helices and are likely to start at amino acid 30 and end at amino acid 49 (residues 14 and 30 for D1) (Fig. 5A). Notably, these single transmembrane segments possess potentially charged residues (D, E, K, R, and H), a feature that is not found in other nondimeric membrane-anchored members of the thioredoxin-fold superfamily [GPX family (9)]. In the deiodinases, these residues interact most likely through electrostatic bridges to neutralize their polarity within the highly hydrophobic membranous environment. In D3, the amino acids of a conserved couple (D37/K43) are separated by six amino acids, which in an α-helix conformation would have a nearly opposite direction with respect to the helix core. In D1, a similar role is played by indirect contacts between E18 and K27. Notably, these transmembrane segments lack proline residues, and only a few G residues are present, suggesting that deiodinases possess regular, unbent (or poorly bent) transmembrane helices. Intermolecular contacts between the histidine side chains of H44 in D3 with main chain atoms may also occur, compatible with a α-α dimeric architecture. Moreover, for D3, R42 is, as K43, directed toward D′37, supporting the predicted K/D bridge. In D1, E18 and K′27 are further apart (∼10 Å), favoring the existence of an ionic pocket filled with a water molecule, which may be readily stabilized by the proximal H22 and not constrained by the relatively small V23, which occupies the D position in D3.

Figure 5.

Deiodinase Dimerization via Transmembrane Segments

A, Sequence alignment of transmembrane segments of the three deiodinases. B, Three-dimensional model of the D3 transmembrane segment homodimer, which can be used for D1 and D2 as well given the sequence homology among these enzymes.

This model of deiodinase homodimer (D3 is shown in Fig. 5B) supports the hypothesis of direct contacts between inversely charged residues, indicating that the deiodinase models of transmembrane segments are particularly stable and energetically favored entities, fully compatible with homo- or heterodimerization, supporting the active participation of these regions in the dimerization process.

Globular Surfaces Mediate D3 Homodimerization

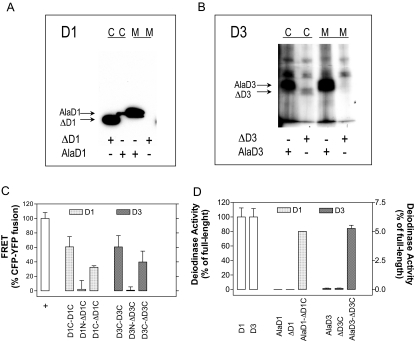

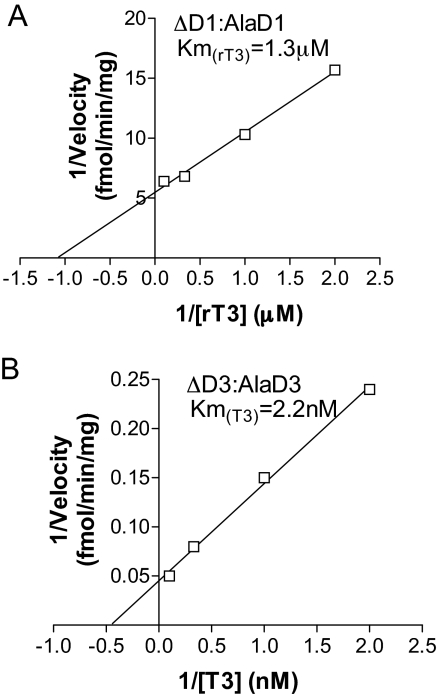

To test experimentally the role of the D3 transmembrane domain in deiodinase dimerization, we truncated D3 at the predicted amino acid (residue 55) that emerges from the membrane generating ΔD3; truncating residue 50 in D1 generates ΔD1. The two proteins were transiently expressed in HEK-293 cells and found predominantly in the cytosolic fraction (Fig. 6, A and B). When expressed alone, ΔD3 or ΔD1 did not homodimerize, as assessed by FRET (Fig. 6C) and BRET (data not shown) and displayed no catalytic activity (Fig. 6D). These findings are compatible with the idea that the transmembrane domains are critical for the deiodinase dimerization. However, we sought to determine whether dimerization between truncated deiodinases and their respective full-length counterparts could occur. This was tested by transiently coexpressing each individual truncated deiodinase molecule fused to YFP at the C terminus with a full-length inactive deiodinase, i.e. ΔD3-YFP with D3-CFP or ΔD1-YFP with D1-CFP. Inactivation of the full-length D3 (and D1) was achieved by replacing the Sec residue at the respective active centers with Ala. Notably, such combination of expressed proteins resulted not only in significant dimerization, i.e. ΔD3:D3 and ΔD1:D1 (Fig. 6C), but also in D3 and D1 catalytic activities, respectively (Fig. 6D). Although maximum velocities were substantially low, the affinities [Michaelis-Menten constant (Km)] for their preferred substrates, respectively T3 and rT3, were indistinguishable from those of the corresponding full-length enzymes (Fig. 7, A and B).

Figure 6.

Studies on Truncated Deiodinases

Subcellular fractionation of FLAG-tagged D1 and D3 proteins transiently expressed in HEK-293 cells by Western blot with anti-FLAG antibody. D1 is studied in panel A and D3 is studied in panel B. Microsomal and cytosolic fractions are indicated as well as samples from culture media of cells transiently expressing ΔD1, ΔD3, or the respective full-length inactive molecules, AlaD1 or AlaD3. C, FRET analyses (as in Figs. 1 and 2) of cells transiently expressing ΔD1 or ΔD3 tagged with the appropriate chromophores, coexpressed with their corresponding full-length molecules; values are the mean ± sd of five to 11 cells. D, Deiodinase activity in cells transiently expressing the combinations of deiodinases shown in panel C. Note that the two far left bars representing D1 and D3 are to be read in the left y-axis. AlaD1 and AlaD3 indicate that the full-length D1 and D3 proteins were inactivated by replacing the Sec residue with Ala. C, Cytosolic; M, microsomal.

Figure 7.

Lineweaver-Burk plot of ΔD1-AlaD1 (E) and ΔD3-AlaD3 (F) proteins transiently expressed in HEK-293 cells

Values are the mean ± sd of four to seven samples. AlaD1 and AlaD3 indicate that the full-length D1 and D3 proteins were inactivated by replacing the Sec residue with Ala.

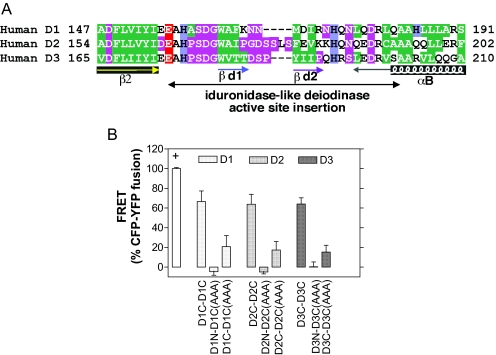

These data support the concept that D3 (and D1) can form homodimers based on interacting surfaces in their globular domain, which is in agreement with the canonical template of the crystal structure of the human thioredoxin dimer [pdb 1eru; (24)] and for D2 (22). A likely candidate structure to constitute this dimerization interface is the specific iduronidase-like active site insertion that, in the deiodinase structure, is situated near the active site holding the essential Sec residue (9,20). Although well conserved at the sequence level among deiodinases (Fig. 8A), there is currently no obvious three-dimensional (3D) template that may directly suggest an overall architecture for this rather long segment, which is likely to possess an intrinsic flexibility favoring mutual fitting of the two moieties of the deiodinase dimer. In this regard, the recent model of α-l-iduronidase (25) does not shed light on this problem because the iduronidase ADPLVGWSLPQP segment, which matches the deiodinase sequence, constitutes only the first half of the active site insertion (9). Moreover, the 3D context of this segment is likely to be different between deiodinases and iduronidase and, given its predicted flexibility, this segment may indeed fold upon contact with other local structures.

Figure 8.

Deiodinase Dimerization via Globular Segments

A, Alignment of the deiodinase-specific iduronidase-like active site insertion. B, CFP-fused D1, D2, or D3 at the C or N termini was coexpressed in HEK-293 cells with the corresponding YFP-fused deiodinase containing the AAA substitutions at the positions 152–154 (IYI) in rD1, 159–161 (VYI) in hD2, and 170–172 (IYI) in hD3. FRET analysis is as in Fig. 1; values are the mean ± sd of five to 15 cells.

We have tentatively modeled this iduronidase segment as an helix followed by a long return to the D2 core, taking into account a relatively high content of alanine in its first half (9). However, recent studies, as well as our present findings, confirming the dimeric behavior of deiodinases prompted us to revisit this modeling, taking into account a likely cooperative interaction between the two halves of this segment. This new approach considered that within the thioredoxin-fold model of deiodinases, this idurodinase-like insertion lies between strand β2 and helix αB, the disposition of which matches those of the strand β7 and α7 helix of the clan GH-A-fold of glycoside hydrolases (9). Immediately after the core β2 (deiodinase) or β7 (iduronidase) strands, a conserved E residue is found in both enzyme families (E156, E163, and E174 in D1, D2, and D3, respectively), the mutation of which inactivates the enzymes. In the D2 model, E163 is about 10 Å from the essential Sec133 within the catalytic site. In the thioredoxin templates, there is also often an acidic E or D residue in this position. Next, in the deiodinases, there are six amino acids, small (A), neutral (H), or belonging to the strong loop-forming amino acid class PGDNS (9). This high concentration of P, S, D, or G strongly suggests a loop linking β2 to a short hydrophobic cluster (WAF, WAI, and WVTT for D1, D2, and D3, respectively), which is typically associated with β-strands (26). Downstream, a second loop is likely to occur (KNN, PGDSSLS, DSP sequences, respectively), leading to another short hydrophobic cluster (MDI, FEV, YII, respectively), which is, like the first cluster, typical of a β-strand. Next, a loop (RNHQN, KKHQN, PQHRS sequences, respectively) is likely to precede the core αB-helix. We refer to the two above putative short β-strands as βd1 and βd2, respectively, as they may participate in a small β-sheet within the dimeric interface of deiodinases (22).

Next, the role of specific amino acid residues within the proposed globular dimerization surfaces (20,21), was tested by creating D1, D2, and D3 mutants fused to YFP at the respective C termini in which the corresponding positions 152–154 (IYI) in D1, 159–161 (VYI) in D2, and 170–172 (IYI) in D3 were mutated to Ala (AAA). Indeed, FRET studies indicated that the energy transfer between these mutant dimer counterparts was only about one third of that observed in the wild-type proteins, confirming a role for these globular sequences in dimerization (Fig. 8B). However, despite this residual FRET signal, we found all these mutants to be catalytically inactive, indicating that these residues are also critical to maintain catalytic activity.

Loss of Energy Transfer between D3:D3 Results in Loss of Deiodinase Activity

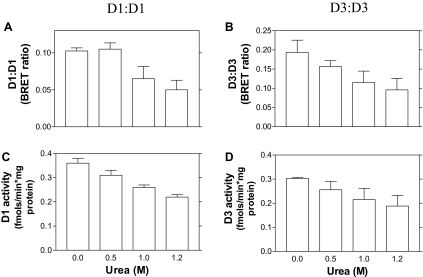

In D2, homodimerization is critical for catalytic activity (22). To test whether this is the case also for D3, we sought to interfere with the D3:D3 dimers by exposing sonicates of cells transiently expressing the appropriately chromophore-fused D3 (or D1) proteins to increasing concentrations of urea, a known caotropic agent, while monitoring BRET and enzymatic activity. Exposure to urea resulted in progressive loss of energy transfer emanating from D3:D3 and D1:D1 dimers (Fig. 9, A and B), which was followed by proportional loss of deiodinase activity (Fig. 9, C and D). Notably, exposure to urea did not interfere with D3-RLuc or D1-RLuc activities or with direct D3-YFP or D1-YFP fluorescence (data not shown). This suggests that a proper fit between the two counterparts in D3:D3 (and D1:D1) is critical for catalytic activity.

Figure 9.

Perturbation of Deiodinase Dimerization and Activity by Urea

BRET studies were as in Fig. 3. D1-RLuc and D1-YFP (A) and D3-RLuc and D3-YFP (B) encoding plasmids were transfected into HEK-293 cells. BRET studies were performed 48 h later. Approximately 20 μg of cell sonicate protein was incubated with increasing concentrations of urea as indicated for 30 min at room temperature, followed by BRET assay (A and B). Deiodinase activity was measured in the same samples (C and D); values are the mean ± sd of four to five samples.

DISCUSSION

Recent studies indicate that D3, previously considered an oncofetal protein, is strongly expressed in tissues of the mature animal during injury (27) and that this D3 activity can lower T3 concentrations both systemically (28) and locally (29) during illness. Whereas these data reveal a fascinating role of D3 in human disease, the factors that regulate its activity are largely unknown. The current study indicates that homodimerization is an important regulatory mechanism for D3. Notably, D3 is the only deiodinase exhibiting a clear tendency of heterodimerization with D1 and D2 (Fig. 3B), the significance of which begs further investigation.

Although the FRET and BRET studies were performed in cells transiently expressing the different chromophore-fused deiodinases, the intrinsic properties of these enzymes, such as subcellular localization and affinity for their preferred substrates, are indistinguishable from endogenously expressed D3 or D1. Protein modeling identified potential dimerization surfaces in the transmembrane and globular domains, the latter capable of supporting ΔD3:D3 or ΔD1:D1 dimers. Lastly, exposure to a high concentration of urea impaired dimerization and deiodinase activity, indicating that homodimerization is critical for catalysis.

Given our previous findings with D2 (22), the present study indicates that all deiodinases have two dimerization surfaces: one in their transmembrane domain and the other in their globular catalytic domain modeled to the iduronidase-like active site insertion situated near the selenocysteine-containing active site. Interestingly, it is clear that for both inner- and outer-ring deiodinases the globular dimerization is sufficient for catalytic activity. As the truncated deiodinases are inactive and do not homodimerize (i.e. ΔD3-ΔD3 or ΔD1-ΔD1) (Fig. 6), the interaction between these two truncated molecules containing only the globular domain does not mediate stable dimerization. However, ΔD3 and ΔD1 still dimerize with their full-length counterparts, which results in catalytic activity (Fig. 6). Whereas it is unclear why there is no interaction between two ΔD3 or ΔD1 globular domains in the cytosol, the finding of dimerization between the globular domains of ΔD3-D3 and ΔD1-D1 indicates that membrane insertion of at least one of the dimer counterparts is required to accommodate globular dimerization.

Notably, the fit between the globular domains in ΔD3-D3 and ΔD1-D1 support catalytic activity with an affinity for their respective preferred substrates that is indistinguishable from native enzymes (Fig. 7), strongly suggesting that dimerization is critical for catalytic activity. In fact, exposure of D3 (or D1) to increasing concentrations of urea, a caotropic agent, resulted in progressive loss of dimerization and proportional decrease of catalytic activity (Fig. 9). Even considering the lack of specificity of the conformational changes induced by urea, these data support a relationship between deiodinase dimerization and catalysis.

Because in ΔD3-D3 and ΔD1-D1, the respective D3 and D1 counterparts are inactive, it is likely that both Sec-containing active centers in each dimer function independently. In fact, we found no evidence of a cross talk between the active centers in both dimer counterparts of any deiodinase, suggesting that dimerization is critical for the conformation of the active center rather than cross talk between them. Given that transiently disrupting D2 dimerization via conjugation to ubiquitin is a switch that controls enzyme activity (22), it remains to be determined whether similar posttranslational mechanisms can interfere with dimerization and regulate the D3 enzyme activity.

Simpson et al. (21) claim to have identified and characterized essential residues critical for dimerization in the globular domain of the deiodinases. By overexpressing sequential alanine-substituted mutants of this domain fused to a green fluorescent protein, they showed that the sequence 152IYI154 was required for D1 assembly and that a catalytically active monomer was generated by a single I152A substitution. For D2, a similar strategy identified five residues (153FLIVY157) at the beginning and three residues (164SDG166) at the end of this region, which were required for dimerization. Although we find no evidence that either deiodinase monomer is active, we mutated such key residues [152–154 (IYI) in D1, 159–161 (VYI) in D2, and those in the corresponding position in D3 (170–172; IYI)] to alanines (AAA) and monitored the ability to homodimerize by FRET exhibited by each deiodinase. Our findings indicate that such mutants retain only about one third of their capacity to dimerize (Fig. 8), but most importantly, they were found to be catalytically inactive. These data would confirm our hypothesis that dimerization is critical for catalytic activity. However, given that these mutants are inactive, it is also conceivable that the amino acid substitutions resulted in deiodinase misfolding, which would minimize the physiological significance of these findings.

In conclusion, the present findings indicate that the thyroid hormone-inactivating deiodinases (D3 and D1) are assembled as homodimers stabilized by interacting surfaces at the transmembrane and globular domains. Whereas only D3 exhibits a limited tendency for heterodimerization with D1 and D2, homodimerization of all three deiodinases seems critical for catalytic activity. Regulation of dimerization could underlie a posttranslational mechanism to control D3- and/or D1-mediated catalysis.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents

T4 was obtained from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) and dissolved in 40 mm NaOH. Outer ring-labeled [125I] rT3 or T3 (specific activity: 4400 Ci/mmol) was from PerkinElmer (Boston, MA). All restriction enzymes and Vent DNA polymerase were from New England Biolabs, Inc. (Beverly, MA). Lipofectamine 2000 was from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA), and cycloheximide was from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

DNA Constructs

All DNA fragments were generated with Vent PCR on templates containing the coding region of rat D1 (rD1) or human D3 (hD3) with a Cys-mutated active center. To fuse the deiodinase fragments to the carboxy portion of YFP or CFP, the generated D1 fragment was inserted between EcoRI and SalI, whereas D3 was cloned between EcoRI and BamHI of pEYFP-C1 or pECFP-C1 (CLONTECH Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, CA), respectively. To fuse rD1 and hD3 to the amino portion of YFP or CFP, the PCR fragments were inserted between EcoRI and BamHI of pEYFP-N1 or pECFP-N1. C or N indicates the terminus of deiodinase used to fuse CFP or YFP.

Vent PCR-based strategy was used to fuse the transmembrane-less (Δ) versions of D1 and D3 to the N portion of YFP. Briefly, the first 50 and 55 residues were deleted from rD1 and hD3, respectively. All fragments were inserted between EcoRI and BamHI of pEYFP-N1. The human D2 (hD2) CFP/YFP fusions have been previously described (22). Overlap-extension PCR was performed to replace the following residues with A: amino acids 152–154 IYI in rD1, amino acids 159–161 VYI in hD2, and amino acids 170–172 IYI in hD3. All of these deiodinase fragments contained Cys instead of selenocysteine and were inserted between EcoRI and BamHI of pEYFP-N1.

Cell Culture and Transfections

HEK-293 epithelial cells were plated in 60-mm plates and grown until midconfluence in DMEM (without phenol red) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum. HEK-293 cells were transfected using Lipofectamine 2000, as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Human GH (thymidine kinase promoter-driven GH) was used as a control for monitoring the transfection efficiency, as described previously (30). The cotransfection ratios of the experimental constructs, truncated N termini, and alanine and cysteine mutants varied depending on the experiment. Usually, 2 μg of each plasmid was transfected, unless otherwise mentioned in the figure legend. Cells were gently washed twice in PBS, 48 h after transfection, and live-cell FRET imaging was performed as described in subsequent sections.

FRET Data and Image Acquisition

We used confocal-based FRET detection by acceptor photobleaching (22). This technique is based on the increase in the donor fluorescence (CFP) immediately after acceptor (YFP) photobleaching (31). Numerical data and image acquisition were obtained using Zeiss LSM 510 confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss, Inc., Thornwood, NY), as described elsewhere (22). In brief, live HEK-293 cells in PBS were examined. Typically, a 2-μm optical slice was used to visualize a cell expressing the constructs of interest tagged with CFP and YFP. Dual excitation of CFP and YFP was achieved by using an argon laser with a 458-nm/514-nm dual dichroic filter (31). Optimized images were collected at 12-bit resolution over 512 × 512 pixels with a pixel dwell time of 1.6 sec (23). A cell was selected as the region of interest, which was then irradiated with the 514-nm laser line (100% intensity); the number of iterations varied, although the goal was to photobleach YFP as quickly as possible. Only cells that exhibited about 85% photobleaching were considered in the FRET studies (32). To appreciate the occurrence of FRET, caution was taken not to saturate the region of interest and to optimize the image carefully and reasonably. A minimum of at least five cells to a maximum of 14 cells per experiment was studied. To analyze a single parameter, typically 10–91 cells were studied in multiple experiments.

Postbleach images were acquired immediately after YFP photobleaching, a process known as “donor dequenching” (23). FRET efficiency was calculated by using the following equation: 100 × (CFP postbleach fluorescence intensity − CFP prebleach fluorescence intensity)/CFP postbleach fluorescence intensity. FRET efficiencies were calculated for all the constructs discussed in Results. Numerical data are normalized and presented as a percent of the positive control, a CFP-YFP fused tandem, because of experiment-to-experiment variability in the FRET efficiencies. D1N-CFP and D1C-YFP (fluorophores tagged in the opposite orientation of the protein are unlikely to yield FRET), and thus such a combination is used as negative control for each respective deiodinase.

BRET Assay

BRET was preformed, as described elsewhere (22). Briefly, HEK-293 cells were transfected with combinations of D1-humanized Renilla (RLuc) and D1-YFP or D3-RLuc and D3-YFP constructs, 1.5 μg each per plate. Cells were washed twice with PBS 48 h post transfection, detached in PBS/2 mm EDTA, centrifuged, and resuspended in PBS/0.1% glucose. Cells (100,000) were dispensed into each well of a 96-well plate with clear bottoms, which had dark surroundings to minimize interference caused by autofluorescence. Studies in cell sonicates were done by resuspending the cell pellet in 250 μl of PBS/0.1% glucose and by sonicating cells for 6 min. Protein was determined according to Bio-Rad protein assay, and equal amounts of protein were added to each well. Renilla was activated by DeepBlueC coelenterazine and read by a Fluostar Optima Fluorimeter (BMG Lab Technologies, Offenburg, Germany) equipped with filters with band pass for emission: 475–30 nm for RLuc luciferase and 535–30 nm for YFP at a set gain. BRET ratio is defined as the [(YFP Emission at 535–30 nm)/RLuc (475–30 nm) of the sample] − RLuc (475–300 nm) in a sample where RLuc construct is expressed alone.

Enzyme Assays of D1 and D3

Deiodinase activities were assayed as described earlier, in the presence of 20 mm dithiothreitol (18). D1 was assayed in the presence of 1 μm [125I]rT3 and D3 in the presence of 2 nm [125I]T3.

Sequence Analysis and Structure Modeling

Further sequence analysis has been conducted using hydrophobic cluster analysis as previously reported for the construction of the thioredoxin fold model of deiodinases (33,34). 3D models were built and handled using the Swiss PDB viewer tool (35).

Acknowledgments

We thank the Optical Imaging facility at the Harvard Center for Neurodegeneration and Repair, Harvard Medical School. The technical suggestions of Ms. Michelle Ocana and Mr. Mark Chafel and the technical help of Ms. Vivien Hársfalvi have been helpful during this investigation.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants DK58538 and TW006467 (to A.C.B.) and by Hungarian Scientific Research Fund Grant Országos Tudományos Kutatási Alapprogram T49081 (to B.G.).

Disclosure Statement: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online March 20, 2008

Abbreviations: BRET, Bioluminescence fluorescence energy transfer; CFP, cyan fluorescent protein; D1, D2, and D3, type 1, type 2, and type 3 deiodinase, respectively; 3D, three dimensional; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; HEK, human embryonic kidney; RLuc, Renilla luciferase; YFP, yellow fluorescent protein.

References

- Oetting A, Yen PM 2007 New insights into thyroid hormone action. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab 21:193–208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Lazar MA 2000 The mechanism of action of thyroid hormones. Annu Rev Physiol 62:439–466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco AC, Salvatore D, Gereben B, Berry MJ, Larsen PR 2002 Biochemistry, cellular and molecular biology and physiological roles of the iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocr Rev 23:38–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Germain DL, Hernandez A, Schneider MJ, Galton VA 2005 Insights into the role of deiodinases from studies of genetically modified animals. Thyroid 15:905–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe M, Houten SM, Mataki C, Christoffolete MA, Kim BW, Sato H, Messaddeq N, Harney JW, Ezaki O, Kodama T, Schoonjans K, Bianco AC, Auwerx J 2006 Bile acids induce energy expenditure by promoting intracellular thyroid hormone activation. Nature 439:484–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianco AC, Kim BW 2006 Deiodinases: implications of the local control of thyroid hormone action. J Clin Invest 116:2571–2579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda N, Berry MJ, Harney JW, Larsen PR 1995 Topological analysis of the integral membrane protein, type 1 iodothyronine deiodinase (D1). J Biol Chem 270:12310–12318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqui MM, Gereben B, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC 2000 Distinct subcellular localization of transiently expressed types 1 and 2 iodothyronine deiodinases as determined by immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Endocrinology 141:4309–4312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I, Curcio-Morelli C, Mornon JP, Gereben B, Buettner C, Huang S, Castro B, Fonseca TL, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC 2003 The iodothyronine selenodeiodinases are thioredoxin-fold family proteins containing a glycoside hydrolase clan GH-A-like structure. J Biol Chem 278:36887–36896 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berry MJ, Banu L, Larsen PR 1991 Type I iodothyronine deiodinase is a selenocysteine-containing enzyme. Nature 349:438–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davey JC, Becker KB, Schneider MJ, St Germain DL, Galton VA 1995 Cloning of a cDNA for the type II iodothyronine deiodinase. J Biol Chem 270:26786–26789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St Germain DL, Schwartzman RA, Croteau W, Kanamori A, Wang Z, Brown DD, Galton VA 1994 A thyroid hormone-regulated gene in Xenopus laevis encodes a type III iodothyronine 5-deiodinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91:7767–7771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez A, Fiering S, Martinez E, Galton VA, St Germain D 2002 The gene locus encoding iodothyronine deiodinase type 3 (Dio3) is imprinted in the fetus and expresses antisense transcripts. Endocrinology 143:4483–4486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baqui M, Botero D, Gereben B, Curcio C, Harney JW, Salvatore D, Sorimachi K, Larsen PR, Bianco AC 2003 Human type 3 iodothyronine selenodeiodinase is located in the plasma membrane and undergoes rapid internalization to endosomes. J Biol Chem 278:1206–1211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friesema EC, Kuiper GG, Jansen J, Visser TJ, Kester MH 2006 Thyroid hormone transport by the human monocarboxylate transporter 8 and its rate-limiting role in intracellular metabolism. Mol Endocrinol 20:2761–2772 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JL, Rosenberg IN 1981 Solubilization of a phospholipid-requiring enzyme, iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase, from rat kidney membranes. Biochim Biophys Acta 659:205–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safran M, Leonard JL 1991 Comparison of the physicochemical properties of type I and type II iodothyronine 5′-deiodinase. J Biol Chem 266:3233–3238 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curcio-Morelli C, Gereben B, Zavacki AM, Kim BW, Huang S, Harney JW, Larsen PR, Bianco AC 2003 In vivo dimerization of types 1, 2, and 3 iodothyronine selenodeiodinases. Endocrinology 144:937–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JL, Visser TJ, Leonard DM 2001 Characterization of the subunit structure of the catalytically active type I iodothyronine deiodinase. J Biol Chem 276:2600–2607 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard JL, Simpson G, Leonard DM 2005 Characterization of the protein dimerization domain responsible for assembly of functional selenodeiodinases. J Biol Chem 280:11093–11100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson GI, Leonard DM, Leonard JL 2006 Identification of the key residues responsible for the assembly of selenodeiodinases. J Biol Chem 281:14615–14621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vivek Sagar GD, Gereben B, Callebaut I, Mornon JP, Zeold A, da Silva WS, Luongo C, Dentice M, Tente SM, Freitas BC, Harney JW, Zavacki AM, Bianco AC 2007 Ubiquitination-induced conformational change within the deiodinase dimer is a switch regulating enzyme activity. Mol Cell Biol 27:4774–4783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick-Davis K, Grinde E, Mazurkiewicz JE 2004 Biochemical and biophysical characterization of serotonin 5-HT2C receptor homodimers on the plasma membrane of living cells. Biochemistry 43:13963–13971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weichsel A, Gasdaska JR, Powis G, Montfort WR 1996 Crystal structures of reduced, oxidized, and mutated human thioredoxins: evidence for a regulatory homodimer. Structure 4:735–751 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rempel BP, Clarke LA, Withers SG 2005 A homology model for human α-l-iduronidase: insights into human disease. Mol Genet Metab 85:28–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eudes R, Le Tuan K, Delettre J, Mornon JP, Callebaut I 2007 A generalized analysis of hydrophobic and loop clusters within globular protein sequences. BMC Struct Biol 7:2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang SA, Bianco AC 2008 Reawakened interest in type III iodothyronine deiodinase in critical illness and injury. Nat Clin Pract Endocrinol Metab 4:148–155 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peeters RP, Wouters PJ, Kaptein E, van Toor H, Visser TJ, Van den Berghe G 2003 Reduced activation and increased inactivation of thyroid hormone in tissues of critically ill patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 88:3202–3211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonides WS, Mulcahey MA, Redout EM, Muller A, Zuidwijk MJ, Visser TJ, Wassen FW, Crescenzi A, da-Silva WS, Harney J, Engel FB, Obregon MJ, Larsen PR, Bianco AC, Huang SA 2008 Hypoxia-inducible factor induces local thyroid hormone inactivation during hypoxic-ischemic disease in rats. J Clin Invest 118:975–983 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyoda N, Zavacki AM, Maia AL, Harney JW, Larsen PR 1995 A novel retinoid X receptor-independent thyroid hormone response element is present in the human type 1 deiodinase gene. Mol Cell Biol 15:5100–5112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpova TS, Baumann CT, He L, Wu X, Grammer A, Lipsky P, Hager GL, McNally JG 2003 Fluorescence resonance energy transfer from cyan to yellow fluorescent protein detected by acceptor photobleaching using confocal microscopy and a single laser. J Microsc 209:56–70 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centonze VE, Firulli BA, Firulli AB 2004 Fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) as a method to calculate the dimerization strength of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) proteins. Biol Proced Online 6:78–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callebaut I, Labesse G, Durand P, Poupon A, Canard L, Chomilier J, Henrissat B, Mornon JP 1997 Deciphering protein sequence information through hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA): current status and perspectives. Cell Mol Life Sci 53:621–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaboriaud C, Bissery V, Benchetrit T, Mornon JP 1987 Hydrophobic cluster analysis: an efficient new way to compare and analyse amino acid sequences. FEBS Lett 224:149–155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guex N, Peitsch MC 1997 SWISS-MODEL and the Swiss-PdbViewer: an environment for comparative protein modeling. Electrophoresis 18:2714–2723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]