Abstract

Resiliency was investigated among well children 6 - 11 years of age (N = 111) whose mothers are living with AIDS or are HIV symptomatic to determine if mother’s HIV status was a risk factor that could effect child resiliency, as well as investigate other factors associated with resiliency. Assessments were conducted with mother and child dyads over 4 time points (baseline, 6-, 12-, and 18-month follow-ups). Maternal illness was a risk factor for resiliency: as maternal viral load increased, resiliency was found to decrease. Longitudinally, resilient children had lower levels of depressive symptoms (by both mother and child report). Resilient children also reported higher levels of satisfaction with coping self-efficacy. A majority of the children were classified as non-resilient; implications for improving resiliency among children of HIV-positive mothers are discussed.

Keywords: HIV, Resiliency, Child, Maternal Illness

Resiliency refers to the capacity for successful adaptation despite challenging circumstances (Garmezy, 1993; Masten, Best, & Garmezy, 1990)--usually assessed as good outcomes among children living in high risk situations over time, or sustained competence under stress. In such definitions, resilient children would not just avoid negative outcomes associated with risk, but also demonstrate adequate adaptation in the presence of adversity (Cowan, Cowan, & Schulz, 1996). Resiliency is impacted by protective factors--individual or environmental characteristics that buffer negative effects of stressors--resulting in more positive behavioral and psychological outcomes than would have been possible in their absence (Masten & Garmezy, 1985). Rutter (1987) found that 70% of children in homes with marital discord (the risk factor) were diagnosed with conduct disorder (the outcome) if they had difficult relationships (the vulnerability factor). However, if the children had at least one good family relationship (the protective factor) the incidence of conduct disorder was low even in homes where there was conflict.

Early resiliency may affect long-term developmental trajectories: children with higher initial resiliency are less likely to begin using alcohol (Wong et al., 2006). While high intelligence is not a requirement for resilient outcomes, it may be a supporting factor, especially as it relates to coping (Kitano & Lewis, 2005). Resilient children have shown greater personal efficacy in coping with stress (Lin, Sandler, Ayers, Wolchik, & Luecken, 2004).

Past research among non-HIV infected samples has shown that chronic illness is a major family stressor. For example, illness-related demands of cancer have been found to predict maternal depressive mood, and lower parenting quality (Lewis & Hammond, 1996); depressed parents typically have restricted response repertoires that disrupt family routines (Webster-Stratton & Hammond, 1988). Previous investigations of children whose mothers are HIV-positive report higher rates of destructive coping and acting out, and less social and cognitive competence (e.g., Esposito et al., 1999; Forehand et al., 1998).

Among HIV-infected mothers with young children, Dutra et al. (2000) found that resiliency was associated with the parent-child relationship, parental monitoring, and parental structure. Numerous studies have shown that resilient children experiencing chronic adversity often benefit from a relationship with a supportive adult (Emery & Forehand, 1996; Masten, 1994; Pedro-Carroll, 2001). Among older children, psychological buffering systems come under their own control, and they seek protective relationships outside their family when needed. However, younger children are highly dependent on caregivers, and thus vulnerable to declines in parenting quality. So, maternal HIV/AIDS may strongly influence children as a risk factor, especially if young children do not have other positive adult influences in their lives.

There has been little investigation assessing resiliency among young children affected by HIV/AIDS. Resilience is an important construct as it identifies how children and families cope despite challenges (Black & Krishnakumar, 1998). The purpose of this study was to determine if mother’s HIV status was a risk factor that could effect child resiliency, as well as investigate factors associated with resiliency.

Method

Participants

Mothers with a diagnosis of AIDS or who were HIV-symptomatic (N = 135) were recruited through primary care and AIDS service organization sites in Los Angeles County. Inclusion criteria were confirmation HIV/AIDS status of a mother who had a well child age 6 - 11, and English or Spanish speaking. HIV symptomatic status was defined using the CDC Guidelines (CDC, 1992) and verified through review of medical records.

A subset of mothers (N = 111) and their children (N = 111) provided complete data across four time-points: baseline, and 6, 12, and 18-month follow-ups. Children’s mean age at baseline was 8.46 years (SD = 1.82); 54.1% were male. Racial/ethnic composition was 32.4% African American, 22.5% Latina/Hispanic, 21.6% White, 18.0% Mixed, 4.5% Native American, and 1% Asian.

Almost half of the mothers (46.8%) had not completed high school; 32.4% completed high school or GED; and 19.8% completed an undergraduate degree, some college, or vocational/technical training; 1 participant had a graduate degree. The majority of were not married (77%). Based on medical chart abstractions at baseline assessment, viral load (RNA copies per ml) was as follows: 31.5% had viral loads of 400 or less; 35.1% in the 401 - 10,000 category; 9.0 % in the 10,001 - 50,000 category; 16.2% had viral loads of over 50,000; and 8.1% did not have current viral levels on record.

Because this was a longitudinal study, some attrition was noted across the 18-months (6%, 13%, and 20% at 6, 12, and 18 months, respectively); however, it appears to have been at random. No association was found (using t-tests or chi-square tests where appropriate) between: attrition and child’s age or gender; or between mother’s age, race/ethnicity, education level, or monthly income. Further, no association was found between attrition and mother’s illness status (viral load or CD4+ counts), nor was attrition associated with resiliency categorization (noted below).

Procedures

UCLA’s Institutional Review Board approved this research. At recruitment sites, agency staff identified eligible families and obtained verbal consent for UCLA interviewers to contact potential participants. Flyers and brochures also were available so clients could contact study staff. UCLA interviewers verified eligibility and obtained mother’s informed consent and child’s assent. Two bilingual interviewers conducted interviews at the family’s home with mother and child interviews conducted simultaneously. Interviews were administered using a computer-assisted interviewing program on laptops. Mothers’ medical records were reviewed at 6-month intervals to record health variables, including viral load.

Interviewers never discussed the mother’s diagnosis with the children. The project was presented as a study of how families get along. Parents were paid $25 and children selected a toy worth $10 from a toy chest (or $10 in cash if requested) immediately after each assessment was completed.

Measures

Viral load

Mothers’ health status was assessed using viral load obtained from medical records abstraction. Records with data closest to the interview date were selected.

Coping

The Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist (Sandler, Tein, & West, 1994) assesses perceived efficacy of coping strategies. Children identified the degree to which coping strategies employed during the past month were effective in making them feel better; the degree to which they were satisfied with the strategies they employed; how well they felt they handled their problems compared to other kids; and how well they thought they would cope in the future.

Depression

The Children’s Depression Inventory (CDI; Kovacs, 1992) was administered to both the children and to the mothers. Cronbach’s alpha for the total score for the children was .79 and .84 for the mothers. The scale consists of five subscales: Negative Mood, Interpersonal Problems, Ineffectiveness, Anhedonia, and Negative Self-Esteem.

Anxiety

Anxiety was evaluated using two subscales from the Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (Reynolds & Richmond, 1978, 1985). For the current sample, alpha was .75 for the Worry/Oversensitivity scale. The alpha for Physiological Anxiety was too low and therefore dropped from final analyses.

Self-Concept

Three subscales from the Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale (Piers, 1993) were administered to the child, including Intellectual and School Status, Popularity, and Happiness and Satisfaction. For the current sample, Cronbach’s alphas were .68, .79, and .66, respectively.

Identification of Resilient Children

Based on criteria similar to those utilized in prior resiliency research (c.f., Dutra et al., 2000; Rouse, Ingersoll, & Orr, 1998), children were identified as either resilient or non-resilient (see below for statistical differentiation). Measures included both child and adult reports of externalizing behaviors from the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991), adult report of the frequency of the child’s social skills measured through the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliott, 1988, 1990), the child’s overall IQ as assessed by the K-BIT (Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990), and a dichotomous indicator that the child had a favorite adult with whom they interacted.

Child Behavior

The externalizing subscale of the Child Behavior Checklist (Achenbach, 1991) was administered to both the mother and the child. Cronbach’s alphas for the current sample on externalizing behaviors were .89 (mothers’ report) and .84 (child’s report).

Social Skills

Social skills were measured using the frequency subscale of the Social Skills Rating System (Gresham & Elliott, 1988, 1990). The mother served as informant for the child (alpha = .54; within boundaries of appropriateness; see Schmitt, 1996).

Cognitive Functioning

The child was administered the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT; Kaufman & Kaufman, 1990), which includes measures of both verbal and nonverbal cognitive functions.

Favorite Adult

This descriptive evaluation was designed to identify important people in the child’s life. Items were based on the “My Family and Friends” assessment (Reid & Landesman, 1986; Reid, Landesman, Treder, & Jaccard, 1989). Two groups were formed: those having favorite adults in their lives and a good relationship with their parents(s), and those not matching these criteria.

Formation of resiliency groupings

Groups of resilient and non-resilient children were formed using hierarchical cluster analysis (Aldenderfer & Blashfield, 1984) taken from the baseline assessment. Cluster analysis was performed with correlation coefficients and between-group average linkage as the clustering method. Data were standardized prior to entry into the clustering routine to make the indicators comparable (Lattin, Carroll, & Green, 2003). A two-cluster solution was imposed yielding a resilient cluster of 36 children and a nonresilient cluster of 75 children. The two groups were then compared on the clustering measures using t-tests at the .05 significance level--children in the resilient cluster exhibited significantly fewer externalizing behaviors, greater closeness to an adult, and a higher frequency of exhibited social skills (no differences were noted on the K-BIT). The cluster solution was cross-validated first by plotting the agglomeration schedule coefficients and evaluating “jumps” or gaps in the coefficients (Gore, 2000), and second through the SPSS TwoStep cluster analysis program (Norusis, 2005), which allows for the evaluation of changes in the Schwarz Bayesian Criterion.

Analyses

Data across the four time-points were used. Profile analysis (an application of multivariate repeated measures) was used to investigate differences between resiliency groups on the psychological well-being variables (Stevens, 1996). Of greatest interest is the “levels test,” which provides an overall assessment of whether resilient children show better psychological well-being than non-resilient children. This evaluation, however, is made only if resiliency groups exhibit parallel profiles on the well-being measures (i.e., no group by time interaction). Assessment of profile flatness is also made given parallel profiles, which combines resiliency groups and evaluates trend variations over time.

Results

The first analysis was to determine if maternal HIV/AIDS was a risk factor among children that could affect resiliency. A Spearman Rho was conducted to assess the association of maternal viral load with child resiliency (N = 102). As viral load increases, resiliency decreases, Spearman Rho = .25, p = .01.

Table 1 contains the observed means, standard deviations, and sample size at each of the four assessment points for children’s psychological well-being. Due to the repeated measures nature of the data, these values reflect cases where all data were available across time for each measure.

Table 1. Observed means, standard deviations, and sample size for Profile Analyses on well-being measures by time.

| N | Baseline M (SD) | FU-6 M (SD) | FU-12 M (SD) | FU-18 M (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child as Informant | |||||

| General Coping Efficacy | |||||

| Handling Problems | 80 | 3.23 (0.90) | 3.25 (0.83) | 3.36 (0.73) | 3.18 (0.92) |

| Coping Satisfaction | 78 | 3.26 (0.89) | 3.22 (0.82) | 3.17 (0.90) | 3.09 (0.84) |

| Coping Confidence | 80 | 3.00 (0.99) | 3.15 (0.86) | 3.28 (0.78) | 3.22 (0.72) |

| Future Coping | 78 | 3.35 (0.89) | 3.22 (0.89) | 3.32 (0.73) | 3.12 (0.70) |

| CDI | |||||

| Negative Mood | 75 | 2.36 (2.06) | 1.63 (1.57) | 1.56 (1.79) | 1.27 (1.52) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 82 | 1.23 (1.57) | 1.07 (1.46) | 0.52 (0.80) | 0.80 (1.16) |

| Ineffectiveness | 82 | 1.33 (1.73) | 1.50 (1.72) | 1.06 (1.42) | 1.12 (1.44) |

| Anhedonia | 79 | 3.35 (2.99) | 2.94 (3.01) | 2.27 (2.45) | 2.30 (2.87) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 77 | 1.35 (1.77) | 0.91 (1.28) | 0.74 (1.21) | 0.51 (1.13) |

| Total | 67 | 9.49 (7.34) | 8.19 (7.32) | 6.30 (5.50) | 6.21 (5.52) |

| RCMAS | |||||

| Worry | 79 | 5.63 (2.88) | 4.86 (3.25) | 4.51 (3.18) | 4.10 (3.16) |

| Piers-Harris | |||||

| Intellectual & School Status | 61 | 13.05 (2.92) | 13.62 (2.93) | 14.07 (2.83) | 14.33 (2.73) |

| Popularity | 70 | 7.36 (2.78) | 8.23 (2.64) | 8.61 (2.27) | 8.39 (2.98) |

| Happiness | 75 | 6.91 (1.45) | 7.04 (1.61) | 7.37 (0.90) | 7.28 (1.39) |

| Adult as Informant | |||||

| CDI | |||||

| Negative Mood | 70 | 1.57 (1.92) | 1.10 (1.53) | 1.07 (1.43) | 1.04 (1.58) |

| Interpersonal Problems | 83 | 0.96 (1.24) | 0.98 (1.43) | 0.81 (1.02) | 0.72 (1.00) |

| Ineffectiveness | 83 | 1.34 (1.36) | 1.57 (1.75) | 1.36 (1.60) | 1.25 (1.78) |

| Anhedonia | 79 | 2.09 (1.90) | 1.70 (1.95) | 1.63 (1.81) | 1.61 (1.83) |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 81 | 0.88 (1.35) | 0.63 (1.02) | 0.77 (1.23) | 0.74 (1.07) |

| Total | 67 | 6.43 (5.25) | 6.22 (5.59) | 5.49 (4.78) | 5.07 (5.22) |

Psychological Well-Being: Child as Informant

Coping

Four items addressing coping efficacy were evaluated (see Table 2 for test statistics and effect sizes). The nonsignificant multivariate tests of parallelism suggest that resiliency groups exhibited parallel profiles across time on all items, suggesting similar coping patterns between resiliency groups across time. Multivariate tests of profile flatness were also nonsignificant suggesting that coping patterns were stable or “flat” across time.

Table 2. Profile Analysis Tests for Well-Being Measures by Time and Resilience Group (RG): Child as Informant.

| Parallelism (Time × RG Interaction) | Flatness (Time Effect) | Levels (RG Effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pillai’s Trace, F(df), d | Pillai’s Trace, F(df), d | F(df), d |

| General Coping Efficacy | |||

| Handling Problems | 0.08, 2.14(3,76), .58 | 0.02, 0.50(3,76), .28 | 4.17*(1,78), .46 |

| Coping Satisfaction | 0.04, 0.99(3,74), .40 | 0.01, 0.27(3,74), .21 | 7.63**(1,76), .63 |

| Coping Confidence | 0.06, 1.73(3,76), .52 | 0.04, 0.99(3,76), .40 | 9.82**(1,78), .71 |

| Future Coping | 0.06, 1.49(3,74), .49 | 0.03, 0.75(3,74), .35 | 10.79**(1,76), .75 |

| CDI | |||

| Negative Mood | 0.07, 1.78(3,71), .55 | 0.25, 8.03**(3,71), 1.17 | 2.52(1,73), .37 |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.05, 1.31(3,78), .45 | 0.18, 5.53**(3,78), .92 | 4.66(1,80), .48 |

| Ineffectiveness | 0.08, 2.29(3,78), .59 | 0.03, 0.73(3,78), .34 | 6.27*(1,80), .56 |

| Anhedonia | 0.01, 0.33(3,75), .23 | 0.13, 3.66*(3,75), .77 | 3.05(1,77), .40 |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.01, 0.31(3,73), .23 | 0.19, 5.69**(3,73), .97 | 4.15*(1,75), .47 |

| Total | 0.09, 2.08(3,63), .63 | 0.22, 5.93**(3,63), 1.06 | 3.70(1,65), .48 |

| RCMAS | |||

| Worry | 0.02, 0.41(3,75), .26 | 0.17, 5.03**(3,75), .90 | 2.41(1,77), .35 |

| Piers-Harris | |||

| Intellectual & School Status | 0.03, 0.56(3,57), 3.43 | 0.15, 3.23*(3,57), .83 | 1.23(1,59), .29 |

| Popularity | 0.09, 2.25(3,66), .64 | 0.14, 3.50*(3,66), .80 | 0.90(1,68), .23 |

| Happiness | 0.04, 0.99(3,71), 41 | 0.06, 1.43(3,71), .49 | 8.08**(1,73), .67 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

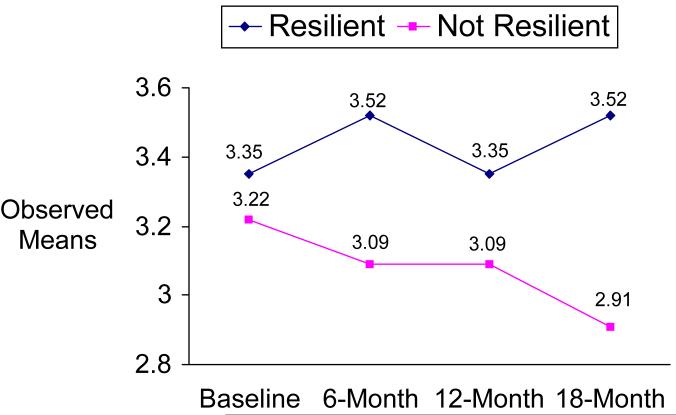

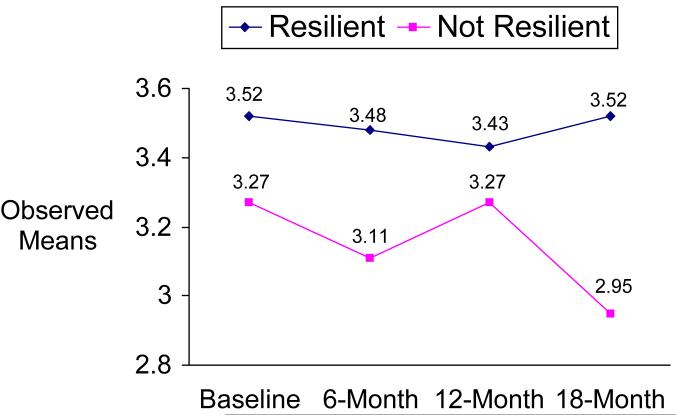

The levels test comparing resiliency groups revealed significant differences on all items (averaged across time), suggesting that resilient children view themselves as having more coping efficacy than non-resilient children. The resilient children reported significantly higher levels of: handling their problems well (M = 3.43 vs. M = 3.18); satisfaction with handling their problems (M = 3.44 vs. M = 3.08; see Figure 1); confidence levels that they handled their problems better than others (M = 3.45 vs. M = 3.04); and confidence that they can handle things better in the future (M = 3.49 vs. M = 3.15; see Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist. Satisfaction with Handling Problems.

Figure 2.

Children’s Coping Strategies Checklist. Confidence in Handling Future Problems.

Depression and Anxiety

Parallel profiles were noted for resiliency groups across time on all of the CDI subscales and total score, and the RCMAS Worry subscale based on the nonsignificant multivariate tests of parallelism.

Deviations from flat profiles were noted for Negative Mood, Interpersonal Problems, Anhedonia, and Negative Self-esteem, CDI Total, and RCMAS Worry. Univariate trend contrasts were performed to evaluate overall deviations from flatness (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2002). Children showed significant linear decreases over time in negative mood (F[1,73] = 24.04, p < .001), interpersonal problems (F[1,80] = 13.60, p < .01), anhedonia (F[1,77] = 9.20, p < .01), negative self-esteem (F[1,75] = 16.96, p < .01), Total CDI (F[1,65] = 15.73, p < .001), and worry (F[1,77] = 12.97, p < .01). In addition, a significant quadratic trend was noted for interpersonal problems (F[1,80] = 4.61, p < .05), suggesting the reduction in interpersonal problems is leveling at latter time points. Overall, these findings suggest a decrease in depression and worry over time for the current child sample.

Test of levels showed group differences two CDI subscales, Ineffectiveness and Negative Self-Esteem. Compared to non-resilient children, resilient children reported significantly lower ineffectiveness (M = 0.83 vs. M = 1.45), and lower negative self-esteem (M = 0.56 vs. M = 1.03). This suggests that resilient children view themselves to be less ineffective and have less negative self-esteem than non-resilient children.

Self-Concept

Parallel profiles were noted for the Intellectual/School Status, Happiness, and Popularity subscales of the Piers-Harris, based on the nonsignificant multivariate tests. Flat profile deviations were noted for Intellectual/School success and Popularity. Children showed a significant linear increase in intellectual and school success over time, (F[1,59] = 9.63, p < .01). For Popularity, a quadratic trend was noted, F(1,68) = 4.39, p < .05, indicating an initial increase in reported popularity over time, followed by a slight decline. Tests of levels did not reveal any differences between groups on Intellectual/School Status, Happiness, or Popularity.

Childs’ Psychological Well-Being: Mother as Informant

Depression

Parallel profiles were noted for resiliency groups across time on the CDI subscales and total score based on the nonsignificant multivariate tests. All profiles were flat except Negative Mood, which showed significant linear decline over time, F(1, 68) = 6.51, p = .01.

Significant levels tests were noted across all scales. Compared to non-resilient children, resilient children reported significantly lower Negative Mood (M = .49 vs. M = 1.50), Interpersonal Problems (M = 0.36 vs. M = 1.06), Ineffectiveness (M = 0.74 vs. M = 1.63), Anhedonia (M = 1.15 vs. M = 1.99), Negative Self-esteem (M = 0.26 vs. M = 0.95), and Total CDI (M = 2.86 vs. M = 7.15). This suggests that resilient children, as seen by their mothers, exhibit less overall depression and related symptoms compared to non-resilient children.

Discussion

In this sample, maternal HIV/AIDS was a risk factor among children that could affect resiliency—more severe maternal illness was associated with decreased resiliency. Resilient children of HIV-positive mothers in this sample reported better coping self-efficacy than did non-resilient children. This is consistent with findings cited earlier by Lin et al. (2004) showing that resilient children had greater efficacy in coping with stress. Such coping and interpersonal problem solving skills play a crucial role in adjustment (Sandler, Wolchik, MacKinnon, Ayers, & Roosa, 1997; Spivack, Platt, & Shure, 1976), with positive consequences in social and school adjustment (e.g., Weissberg & Gesten, 1982). It may be that among this sample of resilient children, those who have a strong relationship with adult care-taking figures have learned and been reinforced for coping skills by these adults. The findings from this sample fit with Werner’s (1984) identification of factors that resilient children have in common, including an active approach toward problem solving, and a tendency to perceive experiences constructively.

The children classified as resilient also evidenced better self-esteem and higher self-report of effectiveness than the non-resilient children. Data from the mothers of these children served as a second informant validation of those findings, with mothers reporting lower negative mood, interpersonal problems, ineffectiveness, anhedonia, and negative self-esteem. This may be linked to better coping skills, in that these children may be able to cope with depression more effectively than the non-resilient children. However, it should be noted that across both groups at baseline assessment, mean depression levels were similar to normative samples (e.g., Chartier, & Lassen, 1994; Finch, Saylor, & Edwards, 1985; Kovacs, 1985), which have means for CDI Total Score of approximately 9.3 to 9.7. In this study, the mean for CDI Total Score was 9.05 for resilient children, and 9.70 for non-resilient children, suggesting neither group was severely depressed. Over time continued declines were shown across both groups, indicating more positive affect, with resilient children evidencing steeper declines by the last time-point (e.g., M = 3.76 for resilient children, and M = 7.33 for non-resilient children). Thus, the resilient children are showing less depressive symptoms, even if neither group is at a clinically significant cut-off level.

While the discussion thus far has focused on the characteristics of the resilient children, one very important point of this study is that the majority of the children (68%) were classified as non-resilient. Those children are dealing with poorer coping self-efficacy and more depressive symptoms. They could benefit from a number of efforts to improve their resiliency outcomes. First, such children are likely to not report that they have a strong adult attachment in their life, and research indicates they could strongly benefit from such a contact. This approach has been utilized by the Minneapolis school system (Minneapolis Public Schools, 1991), in which children are paired with an adult who becomes a support system for them (e.g., for tutoring, homework, etc.). Big Brothers and Big Sisters of America could also be a resource. Second, non-resilient children of HIV-infected mothers could benefit from problem solving and coping skills training. Children can be taught to label feelings, develop self-control, learn problem-solving skills, and apply anger management techniques (e.g., Pedro-Carrol, Sutton, & Wyman, 1999; Stolberg & Mahler, 1994; Wolchik et al., 2002). Children in such programs, in addition to showing skills acquisition, may show improvements in clinical symptomatology. Finally, these children also may benefit from direct psychotherapeutic intervention for depression. Relieving psychological distress may assist these children in being able to function and cope more adaptively, as well as facilitate attachment to adult figures that can provide support.

In summary, the children classified as resilient in our study are functioning in some areas--specifically in coping self-efficacy and mood--better than children classified as non-resilient. Coping skills and competence reduce a child’s vulnerability to deviant behaviors (Wills, Blechman, & McNamara, 1996), such as aggression and substance use, and to adverse life outcomes, such as arrest or teen pregnancy. Findings from this study support previous hypothesized models that predict that adult support will lead to more adaptive coping, and the development of competence (Wills et al.).

This study did have a number of limitations. Future studies with larger sample sizes may be able to investigate ethnic differences among resilient children, as well as age/developmental differences. Another caveat regards the hierarchical cluster analysis results and the use of both child and mother reports on “externalizing behaviors” from the CBCL. Some bias may have entered the cluster procedure since the measures assess the same construct from different informants, and therefore may have unduly influenced the resiliency categorization.

Table 3. Profile Analysis Tests for Well-Being Measures by Time and Resilience Group (RG): Adult as Informant.

| Parallelism (Time × RG Interaction) | Flatness (Time Effect) | Levels (RG Effect) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measures | Pillai’s Trace, F(df), d | Pillai’s Trace, F(df), d | F(df), d |

| CDI | |||

| Negative Mood | 0.02, 0.34(3,66), .25 | 0.11, 2.81*(3,66), .72 | 10.14**(1,68), .77 |

| Interpersonal Problems | 0.01, 0.34(3,79), .23 | 0.04, 0.95(3,79), .38 | 13.63**(1,81), .82 |

| Ineffectiveness | 0.01, 0.13(3,79), .14 | 0.02, 0.56(3,79), .29 | 9.09**(1,81), .67 |

| Anhedonia | 0.04, 0.91(3,75), .38 | 0.10, 2.66(3,75), .65 | 5.57*(1,77), .54 |

| Negative Self-Esteem | 0.01, 0.18(3,77), .17 | 0.04, 1.01(3,77), .40 | 11.79**(1,79), .77 |

| Total | 0.08, 1.73(3,63), .57 | 0.10, 2.38(3,63), .67 | 16.70**(1,65), 1.01 |

p < .05.

p < .01.

References

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; Burlington, VT: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Aldenderfer MS, Blashfield RK. Cluster Analysis. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Black M, Krishnakumar A. Children in low-income, urban settings: Interventions to promote mental health and well-being. American Psychologist. 1998;53:635–646. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.53.6.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO. Social origins of depression: A study of psychiatric disorder in women. Tavistock Publications; London: 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW, Harris TO, Bifulco A. Long-term effects of early loss of parent. In: Rutter M, Izard CE, Read PB, editors. Depression in Young People: Developmental and Clinical Perspectives. Guilford Press; New York: 1986. pp. 251–296. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . 1993 revised classification system for HIV infection and expanded surveillance case definition for AIDS among adolescents and adults. Author; Atlanta, GA: 1992. (Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 41, No. RR-17) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chartier GM, Lassen MK. Adolescent depression: Children’s depression inventory norms, suicidal ideation, and (weak) gender effects. Adolescence. 1994;29:859–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowan PA, Cowan CP, Schulz MS. Thinking about risk and resilience in families. In: Hetherington EM, Blechman EA, editors. Stress, coping, and resiliency in children and families. Family research consortium: Advances in family research. England: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Dutra R, Forehand R, Armistead L, Brody G, Morse E, Morse PS, Clark L. Child resiliency in inner-city families affected by HIV: The role of family variables. Behaviour Research & Therapy. 2000;38:471–478. doi: 10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00070-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery RE, Forehand R. Parental divorce and children’s well-being: A focus on resilience. In: Haggerty RJ, Sherrod LR, Garmezy N, Rutter M, editors. Stress, risk, and resilience in children and adolescents: Processes, mechanisms, and interventions. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 64–99. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito S, Musetti LE, Musetti MC, Tornaghi R, Corbella S, Massironi E, Marchisio P, Guareschi A, Principi N. Behavioral and psychosocial disorders in uninfected children age 6 to 11 years born to human immunodeficiency virus-seropositive mothers. Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1999;20:411–417. doi: 10.1097/00004703-199912000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch AJ, Saylor CF, Edwards GL. Children’s Depression Inventory: Sex and grade norms for normal children. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:424–425. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.53.3.424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forehand R, Steele R, Armistead L, Morse E, Simon P, Clark L. The Family Health Project: Psychosocial adjustment of children whose mothers are HIV infected. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1998;66:513–520. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.66.3.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Stress-resistant children: The search for protective factors. In: Stevenson JE, editor. Recent research in developmental psychopathology: Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry Book. Suppl No 4. Pergamon Press; Oxford: 1985. pp. 213–233. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Resiliency and vulnerability to adverse developmental outcomes associated with poverty. American Behavioral Scientist. 1991;34:416–430. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N. Vulnerability and resilience. In: Funder DC, Parke RD, Tomilinson-Keasey CA, Widaman K, editors. Studying lives through time: Personality and development. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1993. pp. 377–398. [Google Scholar]

- Garmezy N, Rutter M. Acute reactions to stress. In: Rutter M, Hersov L, editors. Child psychiatry: Modern approaches. 2nd ed. Blackwell Scientific; Oxford: 1985. pp. 152–176. [Google Scholar]

- Gore PA. Cluster analysis. In: Tinsley HEA, Brown SD, editors. Handbook of applied multivariate statistics. Academic; San Diego, CA: 2000. pp. 297–321. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Teacher’s social validity ratings of social skills: Comparisons between mildly handicapped and nonhandicapped children. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1988;6:225–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Social Skills Rating System (Parent form elementary level and student form) American Guidance Service Inc.; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. Publisher’s Building. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman AS, Kaufman NL. Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test. Manual. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Kitano MK, Lewis RB. Resilience and coping: Implications for gifted children and youth at risk. Roeper Review. 2005;27:200–205. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Interview Schedule for Children. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1985;21:991–994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Western Psychological Services, Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; Los Angeles: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lattin J, Carroll JD, Green PE. Analyzing multivariate data. Brooks/Cole-Thomson Learning; Pacific Grove, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis FM, Hammond MA. The father’s, mother’s, and adolescent’s functioning with breast cancer. Family Relations: Journal of Applied Family & Child Studies. 1996;45:456–465. [Google Scholar]

- Lin KK, Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, Luecken LJ. Resilience in parentally bereaved children and adolescents seeking preventive services. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2004;33:673–683. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3304_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS. Resilience in individual development: Successful adaptation despite risk and adversity. In: Wang MC, Gordon EW, editors. Educational resilience in inner-city America: Challenges and prospects. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1994. pp. 3–25. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Garmezy N. Risk, vulnerability and protective factors in developmental psychopathology. In: Lahey BB, Kazdin AE, editors. Advances in Clinical Child Psychology. Vol. 8. Plenum Press; New York: 1985. pp. 1–512. [Google Scholar]

- Masten AS, Best KM, Garmezy N. Resilience and development: Contributions from the study of children who overcome adversity. Development and Psychopathology. 1990;2:425–444. [Google Scholar]

- Minneapolis Public Schools . Moving beyond risk to resiliency: The school’s role in supporting resilience in children. CTARS (Comprehensive Teaming to Assure Resiliency in Students) Author; Minneapolis, MA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Norusis MJ. SPSS 13.0 statistical procedures companion. Prentice Hall; Upper Saddle River, NJ: 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Carroll J. The Promotion of wellness in children and families: Challenges and opportunities. American Psychologist. 2001;56:993–1004. doi: 10.1037/0003-066x.56.11.993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedro-Carroll JL, Sutton SE, Wyman PA. A two-year follow-up evaluation of a preventive intervention for young children of divorce. School Psychology Review. 1999;28:467–476. [Google Scholar]

- Piers EV. Piers-Harris Children’s Self-Concept Scale: Revised Manual 1984. Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Reid M, Landesman S. My Family and Friends: A social support dialogue instrument for children. University of Washington; Seattle, WA: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Reid M, Landesman S, Treder R, Jaccard J. My Family and Friends: 6-12 year old children’s perceptions of social support. Child Development. 1989;60:896–910. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. What I think and feel: A revised measure of children’s manifest anxiety. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1978;6:271–280. doi: 10.1007/BF00919131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Richmond BO. Revised Children’s Manifest Anxiety Scale (RCMAS) Western Psychological Services; Los Angeles: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Rouse KAG, Ingersoll GM, Orr DP. Longitudinal health endangering behavior risk among resilient and nonresilient early adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health. 1998;23:297–302. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(98)00019-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutter M. Psychosocial resilience and protective mechanisms. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 1987;57:316–331. doi: 10.1111/j.1939-0025.1987.tb03541.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Tein J, West SG. Coping, stress, and the psychological symptoms of children of divorce: A cross-sectional and longitudinal study. Child Development. 1994;65:1744–1763. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00846.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandler IN, Wolchik SA, MacKinnon D, Ayers TS, Roosa MW. Developing linkages between theory and intervention in stress and coping processes. In: Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, editors. Handbook of children’s coping: Linking theory and intervention. Plenum Press; New York: 1997. pp. 3–40. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt N. Uses and abuses of coefficient alpha. Psychological Assessment. 1996;8:350–353. [Google Scholar]

- Spivack G, Platt JJ, Shure MB. The problem solving approach to adjustment. Jossey-Bass; San Francisco: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Stevens J. Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. 3rd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; Mahwah, NJ: 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Stolberg AL, Mahler J. Enhancing treatment gains in a school-based intervention for children of divorce through skill training, parental involvement, and transfer procedures. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1994;62:147–156. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.62.1.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics. 4th ed. Harper Collins; New York: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Webster-Stratton C, Hammond M. Maternal depression and its relationship to life stress, perceptions of child behavior problems, parenting behaviors, and child conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 1988;16:299–315. doi: 10.1007/BF00913802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weissberg RP, Gesten EL. Considerations for developing effective school-based social problem-solving (SPS) training programs. School Psychology Review. 1982;11:56–63. [Google Scholar]

- Werner EE. Resilient children. Young Children. 1984;40:68–72. [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA, Blechman EA, McNamara G. Family support, coping, and competence. In: Hetherington EM, Blechman EA, editors. Stress, coping, and resiliency in children and families. Family research consortium: Advances in family research. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.; Hillsdale, NJ: 1996. pp. 107–133. [Google Scholar]

- Wolchik SA, Sandler IN, Millsap RE, Plummer BA, Greene SM, Anderson ER, Dawson-McClure SR, Hipke K, Haine RA. Six-year follow-up of preventive interventions for children of divorce: a randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2002;288:1874–1881. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.15.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong MM, Nigg JT, Zucker RA, Puttler LI, Fitzgerald HE, Jester JM, Glass JM, Adams K. Behavioral control and resiliency in the onset of alcohol and illicit drug use: A prospective study from preschool to adolescence. Child Development. 2006;77:1016–1033. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00916.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]