Abstract

Sunitinib, a new vascular endothelial growth factor receptor inhibitor, has demonstrated high activity in renal cell carcinoma (RCC) and is now widely used for patients with metastatic disease. Although generally well tolerated and associated with a low incidence of common toxicity criteria grade 3 or 4 toxicities, sunitinib exhibits a distinct pattern of novel side effects that require monitoring and management. This article summarizes the most important side effects and proposes recommendations for their monitoring, prevention and treatment, based on the existing literature and on suggestions made by an expert group of Canadian oncologists. Fatigue, diarrhea, anorexia, oral changes, skin toxicity and hypertension seem to be the most clinically relevant toxicities of sunitinib. Fatigue may be partly related to the development of hypothyroidism during sunitinib therapy for which patients should be observed and, if necessary, treated. Hypertension can be treated with standard antihypertensive therapy and rarely requires treatment discontinuation. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia usually do not require intervention, in particular no episodes of neutropenic fever have been reported to date. A decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction is a rare, but potentially life-threatening side effect. Because of its metabolism by cytochrome P450 3A4 a number of drugs can potentially interact with sunitinib. Clinical response and toxicity should be carefully observed when sunitinib is combined with either a cytochrome P450 3A4 inducer or inhibitor and doses adjusted as necessary. Knowledge about side effects, as well as the proactive assessment and consistent management of sunitinib-related side effects, is critical to ensure optimal benefit from sunitinib treatment.

Sunitinib, a new multitargeted tyrosine-kinase inhibitor (TKI), has shown high activity in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) and was recently approved by Health Canada for treatment of this disease.1,2,3 Sunitinib inhibits the vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) receptor and other tyrosine kinases, including the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and c-kit receptor at nanomolar concentrations.4,5 TKIs have a unique mechanism of action and exhibit a distinct pattern of novel toxicities. Sunitinib is generally well tolerated and the frequency of common toxicity criteria (CTC) grade 3 or 4 toxicities is low.

However, some distinct side effects require monitoring and treatment. Because of the metabolism and mode of action of sunitinib and the distinct pattern of toxicity, the management of side effects becomes an important issue. In contrast to conventional chemotherapy, which is given only over a defined period of time, treatment with sunitinib and other TKIs is a chronic, continuous treatment that may be given over a prolonged period of time, sometimes years. If treatment is interrupted or terminated, the disease may exacerbate and progress rapidly. Knowledge about and optimal management of side effects is therefore mandatory, and may help avoid unnecessary dose reductions, treatment interruptions or even early treatment terminations, as well as reduce patient discomfort during treatment with sunitinib. Proactive assessment and management of side effects will help to optimize treatment with sunitinib.

This article summarizes the most frequent side effects of sunitinib and makes recommendations for their management, based on the available literature, and on suggestions made by an expert panel of medical oncologists.

General recommendations

Patients receiving therapy with sunitinib should be monitored by a qualified physician experienced in the use of anticancer agents. Patients beginning treatment with sunitinib should be counselled about the potential for side effects related to their treatment and advised about how to identify them. Patients should be encouraged to monitor the status of their health on a regular basis and report any side effects to their healthcare team as soon as possible.

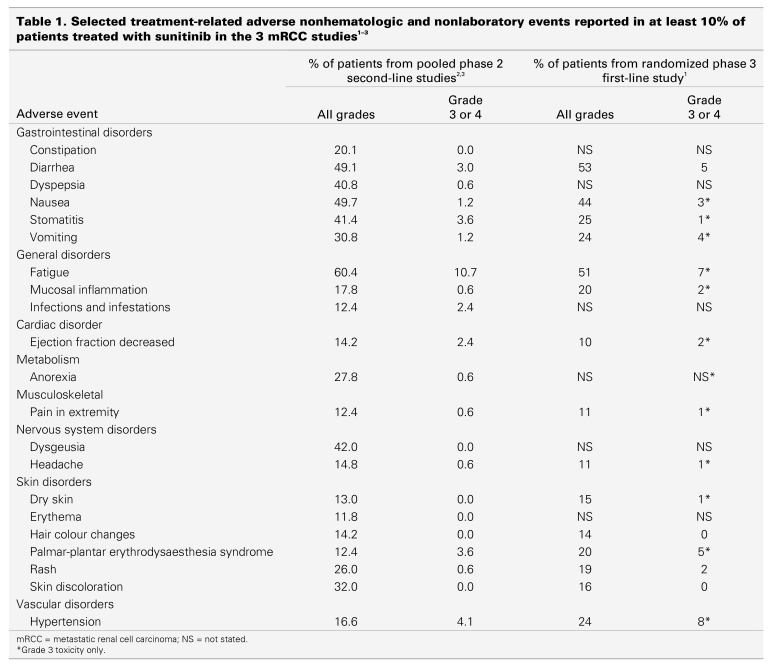

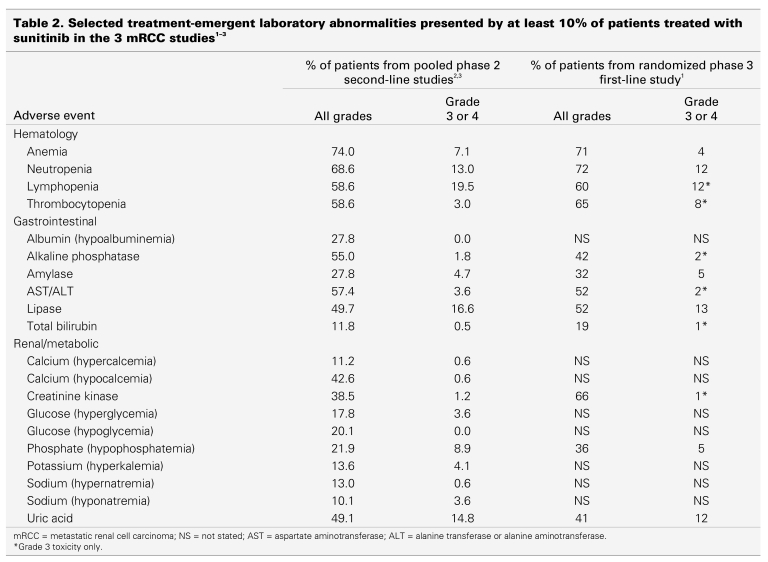

The frequency of hematologic and nonhematologic side effects of sunitinib for patients with mRCC is summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, which are based on the 2 published phase 2 studies of patients with cytokine refractory disease2,3 and the randomized phase 3 study of treatment-naïve patients.1 In general, the frequency of grade 3 and 4 toxicities is relatively low (< 10%).

Table 1.

Table 2.

Dose modifications

A number of side effects caused by sunitinib have been observed in patients who were treated for solid tumours, such as for mRCC and gastrointestinal stromal tumours. Most side effects are reversible and should not result in the discontinuation of sunitinib.6 If necessary, these events can be managed through dose adjustments or interruptions.6 According to the drug monograph, a standard dose modification in 12.5 mg steps is recommended, based on individual safety and tolerability:6

Dose level 1: 50.0 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off

Dose level 2: 37.5 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off

Dose level 3: 25.0 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off

Very few data are available about the best schedule for sunitinib. Tumours tend to regrow when patients are not taking the drug during the 2-week break period. They also tend to regrow if dose reductions lead to plasma concentrations that are too low for complete receptor inhibition. For accurate staging information, imaging studies should be done while the patient is finishing sunitinib rather than during or at the end of an off-drug period.

Based on clinical experience, other dose-modification regimens, such as the following, may be used, if clinically indicated. These schedules have not yet been tested in formal clinical studies and are based solely on the clinical experience of the authors.

Dose level 1: 50.0 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off. If acceptable toxicity, reduction of off-period to 1 week.

Dose level 2: 50 mg for 2 weeks, 1 week off

Dose level 3: 37.5 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off. If toxicity is acceptable, a reduction of the off-period to 1 week or even continuous administration can be attempted.

Dose level 4: 25 mg for 4 weeks, 2 weeks off. Again, if toxicity is acceptable, a reduction of the off-period to 1 week or even continuous administration can be attempted.

Typically, if more than 2 dose reductions are required (total dose reduction > 25 mg), it is preferable to discontinue sunitinib therapy or rechallenge the patient after recovery from side effects. Recovery to acceptable levels of toxicity should occur within 4 weeks before sunitinib therapy can be continued. The start of the next sunitinib schedule may be delayed up to 2 weeks if additional time is required for the patient to recover from treatment-associated toxicity experienced during the current schedule. Re-escalation to the previous dose level is suggested in the absence of grade 3 or higher hematologic treatment-related toxicity, or in the absence of grade 2 or higher nonhematologic treatment-related toxicity in the previous cycle. Overall, clinical judgment based on the medical history and clinical status of individual patients should dictate the appropriate monitoring and actions, if any, to be taken in response to side effects.

Gastrointestinal side effects

Anorexia

Recommendations in this section are based on the authors' experience, if not otherwise stated.

Anorexia is found in about 10%–20% of patients having sunitinib therapy, but rarely exceeds grade2.1–3 Although anorexia rarely requires dose modifications, underlying causes should always be investigated, in particular, a potential relationship to coexisting hypothyroidism and gastrointestinal toxicities (e.g., taste changes, diarrhea, stomatitis or nausea). Patient education about nutrition and consultation with a dietitian is recommended.

Diarrhea

Diarrhea occurs in approximately 53% of patients having sunitinib therapy, but grade 3 or 4 toxicity is rare and observed in only 3%–5% of cases.1–3 In contrast to chemotherapy-induced diarrhea, which is usually continuous, sunitinib-induced diarrhea can occur irregularly; days of diarrhea are mixed with days of normal bowel movements. Dose reductions are rarely necessary for grade 1 and 2 toxicity. Grade 1 and 2 diarrhea may be managed by oral hydration and oral antidiarrheal agents, as needed, such as loperamide.3,6 Treatment should be interrupted for grade 3 or 4 diarrhea until diarrhea is grade 1 or less, or has returned to baseline.6 Usually, the diarrhea resolves quickly in the 2-week break between cycles. The sunitinib dose should be reduced by 1 dose level (12.5mg) in subsequent cycles in cases of grade 3 or 4 diarrhea, based on the dose modifications made in the Sutent studies and the recommendations given in the product monograph.1,2,3,6

Patients can be advised to:§

temporarily discontinue the use of stool softeners and some fibre supplements;

drink plenty of liquids (but in small amounts at a time) and avoid drinking fluids with meals and for 1 hour after meals;

eat and drink often in small amounts;

avoid spicy foods, fatty foods and caffeine; and

avoid high-fibre foods.

The underlying pathogenesis for sunitinib-induced diarrhea is not known. Bowel mucosa changes consistent with ischemic colitis have been reported after treatment with other VEGF-interacting agents, in particular bevacizumab.7

Nausea and vomiting

The emetogenic potential of sunitinib is low. Less than 5% of patients experience grade 3 or 4 vomiting and only 10%–20%, grade 1 or 2.6 Nausea seems to occur more frequently, but grade 3 or 4 nausea is rare. Common antiemetics can be used to relieve nausea and vomiting. If nausea or vomiting is expected, antiemetics can be given prophylactically before administration of sunitinib to limit treatment-related nausea and vomiting.

However, particular care should be used when sunitinib is combined with antidopaminergic agents such as domperidone, or 5HT3 antagonists, such as granisetron, ondansetron, and dolasetron, because they have been associated with QT/QTc interval prolongation or torsade de pointes (see Cardiac toxicity).8

Oral changes, stomatitis, mucositis and heartburn

A number of oral changes, including sensitivity, taste changes, dry mouth and stomatitis or mucositis, occur with varying frequency (10%–30%).1,2,3,6 Dose adjustments or interruptions are seldom necessary.

Patients may experience symptoms (e.g., pain), but lack morphological changes or physical signs of mucositis or stomatitis caused by chemotherapy (functional stomatitis).1,2,3,5 Symptoms usually resolve quickly within the 2-week break between therapy cycles, but tend to recur within subsequent cycles. The extent of oral changes may be correlated with the degree of oral care. Treatment for oral side effects includes nonalcohol mouthwashes, viscous lidocaine, nonperoxide toothpaste, and lip creams or balms for cheilitis.§ Patients should be counselled to make an alcohol-free mouthwash with a half teaspoon of baking soda or salt in 1 cup of warm water and rinse several times a day. Dietary modifications, such as avoiding spicy foods, acidic foods, foods at extreme temperatures, and alcoholic drinks, and eating soft foods, may be helpful.§ H2 blockers are recommended for the treatment of heartburn.

Patients may be counselled:§

to brush their teeth gently after eating and at bedtime with a very soft toothbrush;

if their gums bleed, to use gauze instead of a brush, and to use baking soda instead of toothpaste; and

to use a straw for drinking liquids.

Hypothyroidism

Hypothyroidism has been reported in patients receiving sunitinib as early as 1–2 weeks after the initiation of therapy.9,10,11,12 Eighty-five percent of patients with renal cell carcinoma had abnormal results on 1 or more thyroid-function tests.9 Similar results have been reported in other published studies.10,11,12 These abnormalities were consistent with hypothyroidism in all patients and included elevation of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) levels, decreased T3 levels, and less commonly, decreases in T4 or the free-thyroxine index levels. Thyroid abnormalities were detected relatively early in the treatment (median at cycle 2, with a wide range). Approximately 84% of patients with abnormal results of their thyroid-function tests developed symptoms consistent with hypothyroidism such as fatigue, anorexia, edema, fluid retention or cold intolerance. Thyroid hormone replacement benefited about 50% of the patients treated.9

The incidence of hypothyroidism seems to increase progressively with the duration of sunitinib therapy. Although the mechanism for this complication is unknown, observations of preceding TSH suppression and subsequent absence of visualized thyroid tissue in some patients suggest that sunitinib may induce a destructive thyroiditis through follicular-cell apoptosis.9,10

Regular surveillance of thyroid function is warranted for patients receiving sunitinib.10 Patients should be screened for the development of hypothyroidism with TSH measurements taken at baseline and then at intervals of 2–3 months. A low-serum TSH concentration and mild symptoms suggesting thyroiditis-induced thyrotoxicosis may precede the onset of hypothyroidism, which may itself progress rapidly from mild to profound. Any abnormal TSH value or symptoms suggestive of hypothyroidism should prompt more thorough evaluation. Patients developing overt hypothyroidism should be treated with thyroid hormone replacement therapy. Treatment should be considered, even for patients with subclinical hypothyroidism because these patients are unlikely to achieve normal TSH levels without treatment. Typical levothyroxine doses should allow normalization of TSH concentrations and resolution of symptoms.

Hematotoxicity

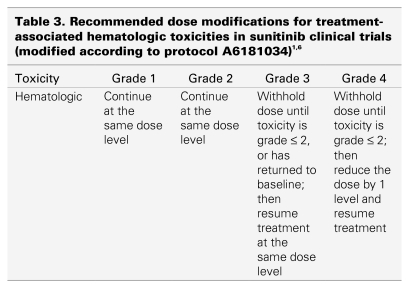

Sunitinib induces neutropenia and thrombocytopenia in about 20% of patients, most likely through inhibition of c-kit. Only 5%–8% of patients develop grade 3 or 4 neutropenia or thrombocytopenia, and no cases of neutropenic fever have yet been reported.1,2,3,6 Blood counts usually recover quickly within the 2-week break between cycles of therapy. Complete blood counts should be done at the beginning of each treatment cycle for patients receiving treatment with sunitinib.1 If grade 3 or 4 neutropenia recurs, or if thrombocytopenia persists for at least 5 days, the dose of sunitinib should be reduced in the next scheduled cycle. Recommended dose reductions are given in Table 3. Patients with neutropenic fever or infection should be seen and treated promptly, as the treating physician deems appropriate.

Table 3.

Grade 3 or 4 lymphopenia and anemia usually do not require dose modification. Erythropoietic agents such as epoetin-α or darbepoetin-α, or blood transfusions may be used at the discretion of the treating physician to treat anemia.2,3 Patients should follow basic guidelines to minimize the risk of infections, including washing hands often and always after using the bathroom, and avoiding crowds and people who are sick. To minimize the risk of bleeding, patients should be counseled:§

to avoid bruises, cuts or burns;

to clean their nose by blowing gently;

to treat constipation if it occurs;

to brush teeth gently with a soft toothbrush to avoid irritating the gums. Maintaining good oral hygiene is important.

Taking acetaminophen is recommended for minor pain.§ Patients should avoid taking ASA, ibuprofen or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents because they may increase the risk of bleeding.

Hypertension

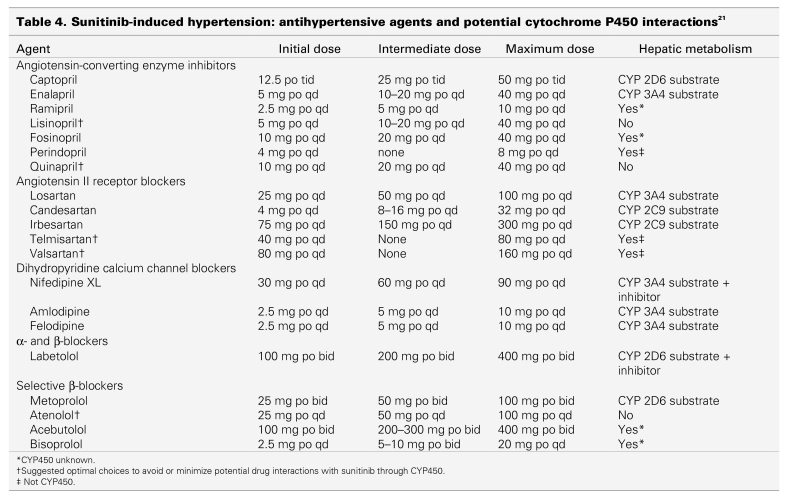

Hypertension seems to be a class effect of angiogenesis inhibitors.13,14,15,16 Bevacizumab, sorafenib and sunitinib have been shown to increase blood pressure.1,15,17 The exact pathogenesis by which sunitinib induces hypertension is not yet known. It has been speculated that TKIs may exert hypertensive effects directly at the level of the vasculature through processes such as vascular rarefaction, endothelial dysfunction or altered nitrous oxide metabolism.13,18 Patients receiving sunitinib should be monitored for hypertension and treated, as appropriate, with standard antihypertensive therapy, including angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors, angiotensin II receptor blockers, calcium-channel blockers (CCBs), β-blockers, and diuretics (e.g., see Canadian Hypertension Guidelines).19,20 Therapy for hypertension is often required only during the therapy phase and may be discontinued when patients are off the drug.

Until more clinical data become available, nondihydropyridine CCBs, such as diltiazem and verapamil, should be avoided because they are known CYP3A4 inhibitors. Other antihypertensive drugs may also potentially interact with cytochrome P450 and could interact with sunitinib (Table 4).21 The objective of treatment is to normalize blood pressure (resting rate < 140/90 mm Hg). Temporary suspension of sunitinib is recommended for patients with severe hypertension (> 200 mm Hg systolic or > 110 mm Hg diastolic).§ Treatment with sunitinib may be resumed once hypertension is controlled. Patients with hypertension that is not controlled by medications should not be treated with sunitinib. Caution should be used if sunitinib is prescribed in combination with other drugs that also cause PR interval prolongation, such as β-blockers and CCBs. The use of dihydropyridine CCBs also has a low risk of causing peripheral edema. These agents predominantly dilate the precapillary limb in the vascular tree, increasing the transcapillary pressure gradient and forcing fluid out of the vascular compartment into tissue, resulting in edema.22,23,24 Pre-existing hypertension may require adjustment of antihypertensive medications during sunitinib therapy. Daily blood pressure monitoring at home and keeping records of blood pressure data in the patient's diary is also suggested for this patient population.

Table 4.

No patients have yet discontinued sunitinib therapy because of hypertension, and dose reductions are rarely necessary.

Bleeding

Bleeding events and tumour hemorrhages have been reported in 26% of patients receiving sunitinib for mRCC.6 Epistaxis was the most common hemorrhagic side effect reported; less common bleeding events included rectal, gingival, upper gastrointestinal, genital, and wound bleeding. Treatment-related hemorrhage of tumours has been observed in patients receiving sunitinib (2%).1,2,3,6 In the case of pulmonary tumours or metastases, this hemorrhage may be a severe life-threatening hemoptysis or pulmonary hemorrhage. A higher incidence of pulmonary hemorrhage has been observed in patients with lung cancer (8%).6 However, in patients with mRCC, severe grade 3 and 4 bleeding incidents were extremely rare (<1%).1,2,3,6 Assessment of hemoptysis should include serial complete blood counts, physical examination and, if indicated, imaging. Temporary discontinuation of sunitinib or dose interruption may be considered until the cause of hemorrhage is determined. A dose discontinuation for mild-to-moderate epistaxis may not be necessary and may be considered only if conventional measures (e.g., tamponade) have failed.§

Cardiac toxicity

Left ventricular dysfunction is the main cardiac side effect of sunitinib, whereas arrhythmias, including bradycardia, and PR and QT prolongation, have been rarely observed (< 1%).1–3,6,24 Caution is advised if QT/QTc or PR-prolonging agents are combined with sunitinib (see also Drug interactions).

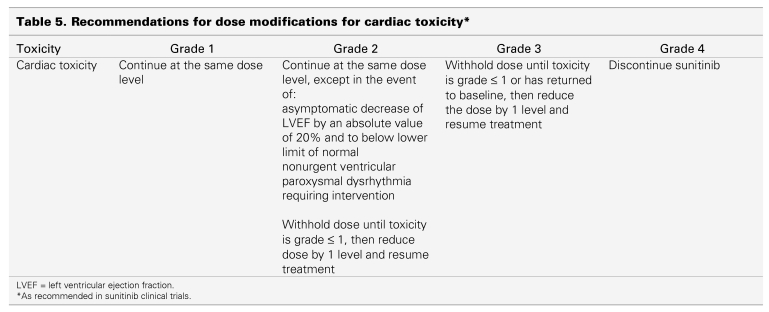

Left ventricular dysfunction, which manifests as a decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF), has been reported in up to 12% of mRCC patients on sunitinib, but symptomatic ventricular dysfunction (CTC grade 3 or 4) was seen in only 1%–2%.6 The clinical significance of these findings remains unknown because no difference in clinically symptomatic heart failure was observed between the 2 study groups in randomized trials.1 Patients who have cardiac risk factors or a recent history of cardiac events (e.g., acute coronary syndrome, arterial bypass graft, symptomatic congestive heart failure [CHF], stroke, or pulmonary embolism) should be monitored for clinical signs and symptoms of CHF, and evaluated for decreased LVEF while receiving sunitinib, including baseline and periodic evaluations of LVEF. For patients with LVEF less than 50% or more than 20% below baseline, the dose of sunitinib should be interrupted or reduced, regardless of clinical evidence of CHF (Table 5). In the presence of clinical manifestations of CHF, discontinuation of sunitinib is recommended. Blood pressure should be monitored more frequently for patients with a history of CHF because an increase can accentuate the clinical symptoms of CHF.

Table 5.

For patients without cardiac risk factors, a baseline evaluation of ejection fraction should be considered.

Fatigue

Fatigue represents one of the most frequently encountered sunitinib-related side effects.1–3,6 Approximately 50%–70% of patients complain about fatigue, although only 7%–11% experience severe fatigue that interferes with the activities of daily living (CTC grade 3).

A number of potential causes should be ruled out. Fatigue may be caused or exacerbated by underlying dehydration. Adequate fluid and nutritional intake should be ensured. Laboratory and clinical evaluations should be done to eliminate other possible causes of fatigue, such as hypothyroidism, anemia or depression. Patients with symptoms suggestive of hypothyroidism should have laboratory monitoring of thyroid function done before and during sunitinib treatment (every 2 months) and be treated according to standard medical practice (see also Hypothyroidism). Thyroid hormone replacement is recommended for patients with mRCC and thyroid abnormalities to improve hypothyroidism-related symptoms and possibly treatment tolerance.9 Anemia may exist and can be identified by monitoring complete blood counts. Erythropoietic agents, such as epoetin-α or darbepoetin-α, or blood transfusions may be used at the discretion of the treating physician. Depression may have an impact on the severity of fatigue. Fatigue improved in some patients who received antidepressants or methylphenidate.§

Patients should be counselled to:§

take short naps or breaks;

eat well and drink plenty of fluids;

take short walks or do light exercise;

do things that are relaxing, such as listening to music or reading; and

not drive a car or operate machinery when feeling tired.

Skin toxicity

Skin toxicity typically occurs after 3–4 weeks of treatment.25 A number of different skin changes may be observed, including hand-foot syndrome, changes in hair colour, skin rash, dry skin, skin discoloration, acral erythema and subungual splinter hemorrhages.

Hand-foot syndrome or acral erythema

Hand-foot syndrome presents as painful symmetric erythematous and edematous areas on the palms and soles, commonly preceded or accompanied by paresthesias, tingling or numbness (Fig.1).6,26 Desquamation can occur in severe cases. Painful hyperkeratotic areas on pressure points surrounded by rings of erythematous and edematous lesions, and painful bullous lesions, blisters or skin cracking can be noted (Fig. 2). Pre-existing hyperkeratosis of the sole seems to confer a predisposition for painful soles and functional consequences. Although this syndrome can sometimes clinically resemble the more classic chemotherapy-induced hand-foot syndrome or palmarplantar erythrodysesthesia that can arise with 5‐fluorouracil, cytarabine, capecitabine or doxorubicin, most patients with sunitinib-induced hand-foot syndrome have more localized and hyperkeratotic lesions that are distinct from classic chemotherapy-induced hand-foot syndrome. In addition, patients may experience symptoms without significant morphologic changes. The exact pathogenesis of this type of hand-foot syndrome is still unknown. The most consistent histologic changes are dermal vascular modifications with slight endothelial changes in grade 1 to 2 hand-foot syndromes and more pronounced vascular alterations with scattered keratinocyte necrosis and intra-epidermal cleavage in grade 3 hand-foot syndromes and peribullous lesions.24 Sunitinib induces endothelial-cell apoptosis in vitro and in animal-tumour models, and pathologic changes observed suggest that dermal-vessel alteration and apoptosis might be due to direct anti-VEGFR or anti-PDGFR effects of sunitinib on dermal endothelial cells.27

Figure 1.

Hand-foot syndrome during sunitinib therapy. Images courtesy of Laura Wood RN and Ronald Bukowski MD, Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center.

Figure 2.

Blister formation during therapy with sunitinib. Images courtesy of Laura Wood RN and Ronald Bukowski MD, Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center.

Management strategies§ for hand-foot syndrome (palmar-plantar erythrodysesthesia syndrome) include having a manicure and pedicure before treatment as a preventative measure, treatment interruptions and a shorter course (2 weeks) of therapy much more often than dose reduction. Palliative intervention includes moisturizers, foot and hand care products (e.g., gel pad inserts, cotton gloves and clobetasol propionate cream), and medication for pain management. Patients should decrease pressure on affected areas, staying off the feet when possible and avoiding friction or pressure to the hands. During treatment, shock absorbers may be used to relieve painful pressure points, and sandals seem to be helpful for some patients.26

Patients can be counselled to:§

avoid tight-fitting shoes or rubbing pressure on the hands and feet, such as that caused by heavy activity;

avoid tight-fitting jewellery;

avoid shaving off blisters because this condition will worsen;

wear loose cotton clothes;

clean hands and feet with lukewarm water (avoid using hot water), and gently pat dry;

apply a sunscreen with a sun protection factor of at least 30; and

apply creams containing lanolin or urea to the hands and feet liberally and often, when therapy begins.

Asymptomatic subungual splinter hemorrhages, consisting of a mass of blood in a layer of squamous cells adherent to the undersurface of the nail, can be observed as well.28

Skin rash

Generalized erythema, maculopapular or seborrheic dermatitis-like rashes have been reported with sunitinib therapy, the vast majority of which are CTC grades 1 or 2.1,3,6,25,29,30 Skin rashes caused by sunitinib rarely require dose reduction and the symptoms tend to decrease over time. Patients should be advised to use moisturizing skin lotions or creams often, particularly after showers or before bedtime. Urea-containing lotions may be helpful, particularly if the skin is very dry. Patients can use anti-itch formulas and antidandruff shampoos if they have itchy scalps or scalp discomfort.26 A recent study31 suggested that the use of colloidal oatmeal lotion may be beneficial in controlling tyrosine-kinase–associated skin rash. Patients should avoid hot showers, use sun protection and wear loose-fitting cotton clothes. If their cases are severe, they may use topical therapies such as steroid creams.

Changes in skin or hair colour

Yellow discolouration of the skin caused by the yellow colour of the active drug and its metabolite is a common treatment-related adverse event of sunitinib therapy. Occurring in approximately 30% of patients, this side effect is reversible when treatment is discontinued.6,25 Yellow discolouration of the urine has been observed in conjunction with skin discolouration because of excretion of the drug and its metabolites.25

Hair depigmentation can occur after 5–6 weeks of treatment (2–3 weeks in men with facial hair), but this effect is reversible as early as 2–3 weeks after treatment is discontinued (Fig. 3).25 Successions of depigmented and normally pigmented bands of hair may correlate with on and off periods of treatment.

Figure 3.

Hair depigmentation during sunitinib therapy. Images courtesy of Laura Wood RN and Ronald Bukowski MD, Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center.

Sunitinib-induced hair depigmentation is thought to be caused by blockade of c-kit signaling and other receptors. Kit-signaling is vitally important for both melanocyte proliferation or differentiation and proper pigment production.32,33 Persistence of melanocytes associated with hair follicles on biopsies indicated that sunitinib did not affect the migration and survival of melanocytes. Experiments with mice suggest that sunitinib inhibits melanocyte function rather than their development or survival.34

Laboratory abnormalities

A number of laboratory abnormalities have been described (Table 2), but differentiating between treatment-induced and disease-induced changes may be difficult. These abnormalities, however, rarely require intervention. Like other tyrosine kinase inhibitors, sunitinib induces an inapparent elevation of amylase and lipase in 30%–50% of cases (all CTC grades), but no case of sunitinib-induced pancreatitis has yet been reported.1,2,3,6,25 Electrolyte disturbances can usually be corrected orally.

Drug interactions

CYP3A4-interacting agents

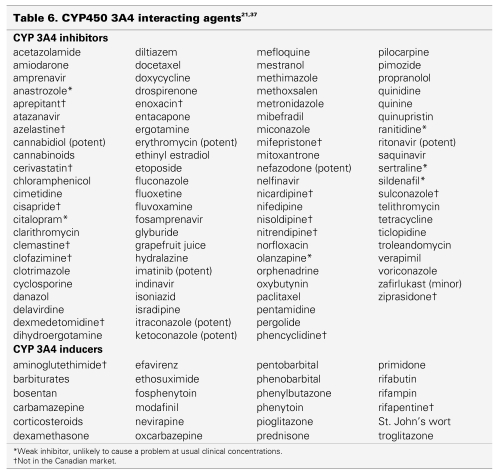

Because sunitinib is metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, potential interactions may occur with drugs that are potent inhibitors or inducers of this enzyme system. The current list of medications should be screened for each patient before dosing with sunitinib to minimize potential interactions with concomitant CYP3A4 inducers or inhibitors.

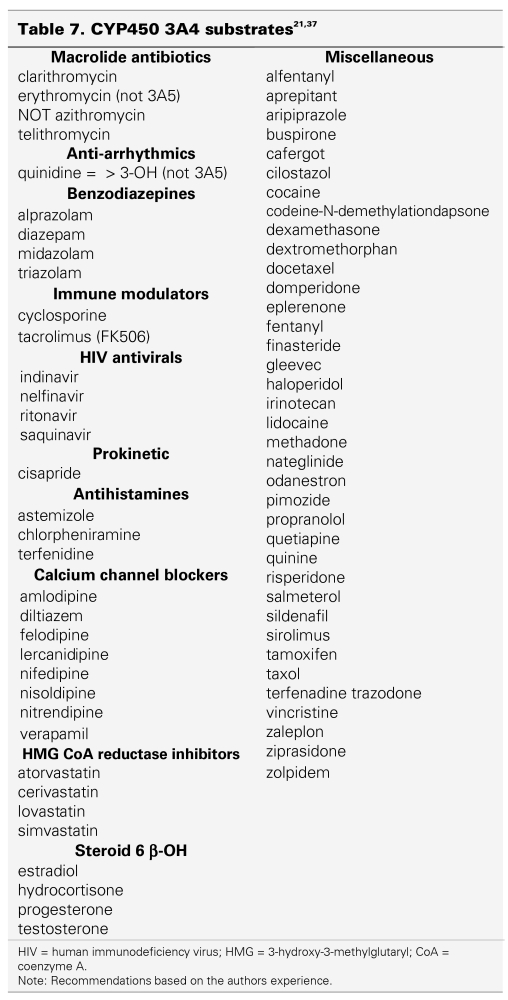

Overall, co-administration of drugs classified as substrates with sunitinib can result in potentially higher concentrations of the substrate. Sunitinib should not be administered concurrently with medications that have a narrow therapeutic window and are substrates of CYP3A4.

When sunitinib is co-administered with compounds classified as inhibitors, plasma concentrations of sunitinib may increase. Concomitant administration of sunitinib with CYP3A4 inhibitors should be avoided. If the combination of sunitinib with a potent CYP450 inhibitor is necessary, sunitinib doses may need to be reduced, and clinical toxicity and response should be monitored carefully. Co-administration of sunitinib with ketoconazole, a potent CYP450 inhibitor, resulted in a 49% increase in combined (sunitinib and its active metabolite) maximum concentration (Cmax) in healthy volunteers.35

In contrast, the co-administration of inducers could potentially lower plasma sunitinib concentrations. Concomitant administration of sunitinib with CYP3A4 inducers, therefore, should also be avoided. If the concomitant administration of sunitinib and a potent CYP450 inducer is unavoidable, clinical response and toxicity must be monitored carefully, and sunitinib doses increased, if necessary. In healthy volunteers, concomitant administration of sunitinib and rifampin, a potent CYP450 inducer, resulted in a 23% reduction of combined (sunitinib and its active metabolite) Cmax.36

In general, the safety and efficacy of sunitinib with concomitant use of a CYP450 inhibitor or inducer has not yet been established in clinical trials.

Table 6 lists drugs that may interact with sunitinib.37,38 The only scientific evidence available about drug-drug interactions with sunitinib are combinations with ketoconazole (CYP3A4 inhibitor) and rifampin (CYP3A4 inducer).35,36 All other drugs listed in Table 6 are hypothetically likely to interact with sunitinib, but have not been evaluated at this point. The potential also exists for interactions between sunitinib and other P450 (CYP3A4) substrates, a selection of which are listed in Table 7. These have not been studied thus far as well.

Table 6.

Table 7.

According to Drug Interaction Facts,38 only St. John's wort and grapefruit juice are listed as possible interactions with sunitinib. No medical literature is available to document these potential interactions.38

Drugs that prolong the QT/QTc or PR interval

The concomitant use of sunitinib with other drugs known to prolong the QT/QTc is in general discouraged to avoid an increased risk of adverse cardiac events. If necessary, particular care should used. Drugs that have been associated with QT/QTc prolongation include, but are not limited to, the following:6

antiarrhythmics, for example, class IA (e.g., procainamide, disopyramide), class III (e.g., amiodarone, sotalol), and class IC (e.g., flecainamide);

antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol, droperidol);

antidepressants (e.g., amitriptyline, fluoxetine);

opioids (e.g., methadone);

macrolide antibiotics (e.g., erythromycin, clarithromycin);

quinolone antibiotics (e.g., ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin);

5HT3 antagonists (e.g., ondansetron, granisetron); and

domperidone.

Caution is also advised if sunitinib is combined with other drugs that prolong the PR interval, such as β-blockers, some CCBs, digitalis and HIV protease inhibitors.6

The use of coumarin-derivative anticoagulants such as warfarin is not recommended, although doses up to 2 mg daily are acceptable prophylaxis for thrombosis. Careful monitoring of patients taking coumarin-derivative anticoagulants is imperative, and changing therapy to low-molecular-weight heparin such as dalteparin should be considered.

Grapefruit juice also has CYP3A4 inhibitory activity. Ingestion of grapefruit or grapefruit juice during sunitinib therapy may lead to decreased metabolism and increased plasma concentrations of sunitinib. Concomitant administration of sunitinib with grapefruit juice should be avoided.

St. John's wort is a potent CYP3A4 inducer. Its co-administration with sunitinib may increase metabolism and decrease plasma concentrations of sunitinib. Patients receiving sunitinib should not take St. John's wort concomitantly.

Conclusions

Sunitinib has demonstrated an unprecedented significant efficacy in the first-line treatment of mRCC. Fatigue, diarrhea, anorexia, oral changes, skin toxicity and hypertension seem to be the most clinically relevant toxicities. Neutropenia and thrombocytopenia usually do not require intervention, in particular no episodes of neutropenic fever have been reported to date. Increasing knowledge about side effects, as well as the proactive assessment and consistent management of sunitinib-related side effects is critical to ensure optimal benefit from sunitinib treatment.

Disclaimer

Patients receiving therapy with sunitinib should be monitored by a qualified physician experienced in the use of anticancer agents. Patients beginning treatment with sunitinib should be counselled about the potential for side effects related to their treatment and advised about how to identify them. Patients should be encouraged to monitor the status of their health on a regular basis and report any side effects to their healthcare team as soon as possible.

The information provided in this manuscript is based on recommendations in the Canadian product monograph for sunitinib, published medical evidence, sunitinib clinical trials and consultation with an expert panel of Canadian medical oncologists. Nevertheless, clinical judgment based on the medical history and clinical status of the patient should dictate the appropriate monitoring and actions to take, if any, in response to side effects of sunitinib.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements: We thank Laura Wood, RN, and Ronald Bukowski, MD, Cleveland Clinic Taussig Cancer Center for providing the images.

Footnotes

§Recommendations based on authors' experience.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: Drs. Kollmannsberger and Bjarnason have both received honoraria from Pfizer for consultancy, speaker's fees, educational grants or travel assistance from Pfizer, Canada, as well as Bayer Canada. Dr. Soulieres has received honoraria from Pfizer for consultancy and presentations. Drs. Scalera and Gaspo are Pfizer employees and own stock in Pfizer. Dr. Wong has received honoraria from Pfizer for consultancy and compensation for conducting research in connection with this article.

References

- 1.Motzer RJ, Hutson TE, Tomczak P, et al. Sunitinib versus interferon alfa in metastatic renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:115-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24: 1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Motzer RJ, Rini BI, Bukowski RM, et al. Sunitinib in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JAMA 2006;295:2516-24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rini BI, Sosman JA, Motzer RJ. Therapy targeted at vascular endothelial growth factor in metastatic renal cell carcinoma: biology, clinical results and future development. BJU Int 2005;96:286-90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Motzer RJ, Bukowski RM. Targeted therapy for metastatic renal cell carcinoma. JClin Oncol 2006;24:5601-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pfizer Canada Inc. SUTENT product monograph. Pfizer Inc. Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lordick F, Geinitz H, Theisen J, et al. Increased risk of ischemic bowel complications during treatment with bevacizumab after pelvic irradiation: report of three cases. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2006;64:1295-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Navari RM, Koeller JM. Electrocardiographic and cardiovascular effects of the 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor antagonists. Ann Pharmacother 2003;37:1276-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rini BI, Tamaskar I, Shaheen P, et al. Hypothyroidism in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma treated with sunitinib. J Natl Cancer Inst 2007;99:81-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Desai J, Yassa L, Marqusee E, et al. Hypothyroidism after sunitinib treatment for patients with gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Ann Intern Med 2006;145:660-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shaheen PE, Tamaskar IR, Salas RN, et al. Thyroid function tests (TFTs) abnormalities in patients (pts) with metastatic renal cell carcinoma (mRCC) treated with sunitinib [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2006;24:4605. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schoeffski P, Wolter P, Himpe U, et al. Sunitinib-related thyroid dysfunction: a single-center retrospective and prospective evaluation [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2006; 24:3092. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sica DA. Angiogenesis inhibitors and hypertension: an emerging issue. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24:1329-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Willett CG, Boucher Y, di Tomaso E, et al. Direct evidence that the VEGF-specific antibody bevacizumab has antivascular effects in human rectal cancer. Nat Med 2004; 10: 1457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yang JC, Haworth L, Sherry RM, et al. A randomized trial of bevacizumab, an anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antibody, for metastatic renal cancer. N Engl J Med 2003;349:427-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad T, Eisen T. Kinase inhibition with BAY 43-9006 in renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res 2004;10:6388S-92S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Escudier B, Eisen T, Stadler WM, et al. Sorafenib in advanced clear-cell renal-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med 2007;356:125-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Veronese ML, Mosenkis A, Flaherty KT, et al. Mechanisms of hypertension associated with BAY 43-9006. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:1363-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Khan NA, McAlister FA, Rabkin SW, et al. The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part II — therapy. Can J Cardiol 2006;22:583-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hemmelgarn BR, McAlister FA, Grover S, et al. The 2006 Canadian Hypertension Education Program recommendations for the management of hypertension: part I — blood pressure measurement, diagnosis and assessment of risk. Can J Cardiol 2006; 22: 573-81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP. Cytochrome P-450 enzymes and drug metabolism. In: Lacy CF, Armstrong LL, Goldman MP, editors. Drug information handbook 12th ed. Hudson, OH: Lexi-Comp; 2004. p. 1619-31. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dougall HT, McLay J. A comparative review of the adverse effects of calcium antagonists. Drug Saf 1996;15:91-106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cross BW, Kirby MG, Miller S, et al. A multicentre study of the safety and efficacy of amlodipine in mild to moderate hypertension. Br J Clin Pract 1993;47:237-40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pedrinelli R, Dell'Omo G, Melillo E, et al. Amlodipine, enalapril, and dependent leg edema in essential hypertension. Hypertension 2000;35:621-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Faivre S, Delbaldo C, Vera K, et al. Safety, pharmacokinetic, and antitumor activity of SU11248, a novel oral multitarget tyrosine kinase inhibitor, in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:25-35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Robert C, Soria JC, Spatz A, et al. Cutaneous side-effects of kinase inhibitors and blocking antibodies. Lancet Oncol 2005;6:491-500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rouffiac V, Bouquet C, Lassau N, et al. Validation of a new method for quantifying in vivo murine tumor necrosis by sonography. Invest Radiol 2004;39:350-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robert C, Faivre S, Raymond E, et al. Subungual splinter hemorrhages: a clinical window to inhibition of vascular endothelial growth factor receptors? Ann Intern Med 2005; 143:313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Motzer RJ, Michaelson MD, Redman BG, et al. Activity of SU11248, a multitargeted inhibitor of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor and platelet-derived growth factor receptor, in patients with metastatic renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24: 1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tsai KY, Yang CH, Kuo TT, et al. Hand-foot syndrome and seborrheic dermatitis-like rash induced by sunitinib in a patient with advanced renal cell carcinoma. J Clin Oncol 2006; 24: 5786-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alexandrescu DT, Vaillant JG, Dasanu CA. Effect of treatment with a colloidal oatmeal lotion on the acneform eruption induced by epidermal growth factor receptor and multiple tyrosine-kinase inhibitors. Clin Exp Dermatol 2007;32:71-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Botchkareva NV, Khlgatian M, Longley BJ, et al. SCF/c-kit signaling is required for cyclic regeneration of the hair pigmentation unit. FASEB J 2001;15:645-58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hemesath TJ, Price ER, Takemoto C, et al. MAP kinase links the transcription factor Microphthalmia to c-Kit signalling in melanocytes. Nature 1998;391:298-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moss KG, Toner GC, Cherrington JM, et al. Hair depigmentation is a biological readout for pharmacological inhibition of KIT in mice and humans. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 2003; 307:476-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Washington C, Eli M, Bello C, et al. The effect of ketoconazole (KETO), a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor, on SU011248 pharmacokinetics (PK) in Caucasian and Asian healthy subjects [abstract]. Proc Am Soc Clin Oncol 2003;22:138. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bello C. The effect of rifampin on the pharmacokinetics of sunitinib malate (SU11248) in Caucasian and Japanese populations [abstract]. Eur J Cancer 2005;3(Suppl):430. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Canadian Pharmacists Association. Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties 41st ed. Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists' Association.; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tatro DS. Drug interaction facts St. Louis: Wolters Kluwers; 2005. [Google Scholar]