Abstract

Introduction

Health advocacy is a well-defined core competency recognized by medical education and regulatory bodies. Advocacy is stressed as a critical component of a physician's function within his or her community and also of performance evaluation during residency training. We sought to assess urology residents' perceptions and attitudes toward health advocacy in residency training and practice.

Methods

We administered an anonymous, cross-sectional, self-report questionnaire to all final-year urology residents in Canadian training programs. The survey was closed-ended and employed a 5-point Likert scale. It was designed to assess familiarity with the concept of health advocacy and with its application and importance to training and practice. We used descriptive and correlative statistics to analyze the responses, such as the availability of formal training and resident participation in activities involving health advocacy.

Results

There was a 93% response rate among the chief residents. Most residents were well aware of the role of the health advocate in urology, and a majority (68%) believed it is important in residency training and in the urologist's role in practice. This is in stark contrast to acknowledged participation and formal training in health advocacy. A minority (7%–25%) agreed that formal training or mentorship in health advocacy was available at their institution, and only 21%–39% felt that they had used its principles in the clinic or community. Only 4%–7% of residents surveyed were aware of or had participated in local urological health advocacy groups.

Conclusion

Despite knowledge about and acceptance of the importance of the health advocate role, there is a perceived lack of formal training and a dearth of participation during urological residency training.

Introduction

There was a sea change in medical education in North America in the 1990s, with the addition of the concept of formal education to the broader roles a physician fills in practice and in the community, beyond simply being a medical expert. The Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada (RCPSC) initiated its CanMEDS program in 1996, and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Outcome Project formalized its general competencies in 1999.1,2 CanMEDS details 7 physician roles (medical expert, communicator, collaborator, manager, health advocate, scholar and professional); the 6 general competencies of the Outcome Project (patient care, medical knowledge, practice-based learning and improvement, interpersonal and communication skills, professionalism and systems-based practice) encompass similar objectives.

The RCPSC definition of health states that “as health advocates, physicians responsibly use their expertise and influence to advance the health and well-being of individual patients, communities and populations.”3 This includes the concepts of health promotion, disease prevention, resource identification and access as well as the modification of the determinants of health at the patient and community level. This role has been the subject of some scrutiny and found to be fraught with difficulty both in terms of its definition and its practical teaching.4,5,6 A recent Canadian study identified difficulty on the part of faculty and residents in defining the health advocate role as well as trouble learning and evaluating the role in resident education.4

With the adoption of these roles and competencies by the major accrediting bodies as well as their incorporation into undergraduate and postgraduate curricula, there is no question that teaching, learning and evaluating these roles becomes important. They have become part of residency objectives and evaluation and part of residency program accreditation, and they remain part of medical practice. While some roles easily fit classical models of medical education focusing on knowledge and skills development, others have proven more frustrating to educators and students.4,5,7

In our study, we sought to assess urology residents' perceptions and attitudes toward health advocacy in training and practice.

Methods

Our prospective study surveyed PGY-5 residents in English-speaking Canadian urology training programs (n = 32) participating in a review course. Participation was completely voluntary and confidentiality was maintained at all times as no identifying information was recorded in the survey results. We obtained ethics approval from the Queen's University Institutional Review Board. We distributed explanations of the study objectives and assurance of confidentiality to the residents responding to the survey.

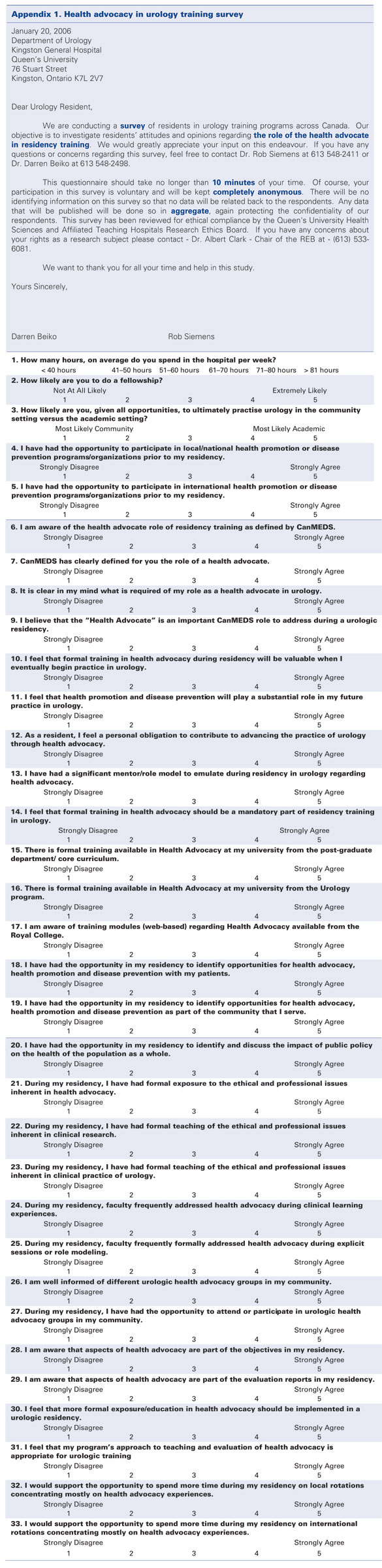

The questionnaire consisted of 33 closed-ended questions designed to explore the residents' experiences and attitudes involving health advocacy in the urology training programs (Appendix 1). This included their familiarity with the concept of health advocacy as well as its application and perceived importance in training and practice. The first 5 questions assessed the residents' demographic information, background and career aspirations as well as their past local or international experience with health promotion or disease prevention programs and organizations. The remaining questions addressed the above-described objectives, including attitudes and experiences regarding formal training and resident participation in advocacy-related activities. The questionnaire developed as the result of an initial experience with a previous survey design that assessed similar attitudes for specialty residents. Residents and educators involved in both undergraduate and postgraduate programs were asked to assess and modify the survey for clarity.

We used descriptive statistics to analyze respondents' demographic and background characteristics. For the purposes of reporting the questions using the 5-point Likert scale, the agreement responses 4 and 5 were grouped together, as were the disagreement responses 1 and 2. Depending on the normality of the distribution, we used either Spearman or Pearson tests to demonstrate correlations of respondents to questions using the Likert scale. We used the GraphPad Prism 4 statistical software package (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, Calif.) for analysis.

Results

Our survey had a 93% response rate. Eighty-two percent of the respondents stated that they were likely to undertake fellowship training upon graduation from their urology program. Forty-six percent indicated a desire or strong desire to enter a community-based practice.

Familiarity with health advocacy

Of respondents, 57% were aware of the health advocate role as defined by the RCPSC in CanMEDS (21% stated that they were not aware of the role). Of the 28 respondents, 17 (61%) were aware that the concept of health advocacy was part of their in-training evaluation reports.

Importance of the role

Nineteen (68%) respondents agreed or strongly agreed that health advocacy is an important role to address in residency training. The same proportion noted a feeling of personal obligation to contribute to the advancement of the practice of urology through health advocacy, and that health promotion and disease prevention will be important in their future practices. Fewer respondents (12 of 28, 43%) felt that formal training in health advocacy during residency would be valuable in practice. Six respondents disagreed with suggestion that formal training in advocacy issues was important to a urological residency.

Experience in health advocacy

Before beginning residency training, only 5 (18%) respondents had participated in health promotion or disease prevention activities. Thirty-nine percent of respondents had identified opportunities to employ health advocacy strategies with their patients; 36% had not. Twenty-one percent had identified opportunities to do so at the community level. Surprisingly, a minority of residents (7%) agreed that they were well informed about urological health advocacy groups in their community, and only 1 respondent (4%) had participated in the activities of such a group.

Health advocacy in training

Of respondents, between 7% and 14% were aware of formal training in health advocacy and of the health advocacy role available in their program, at their institution or as electronic teaching modules. Twenty-five percent of respondents felt that their program had an appropriate approach to teaching and evaluating health advocacy; 3 of 28 (11%) felt that health advocacy was frequently addressed by their attending staff in the clinical setting; and 46% felt that they did not have a mentor to emulate in health advocacy in urology.

Attitudes toward health advocacy

Twenty-five percent of respondents agreed or strongly agreed that formal training in health advocacy should be mandatory in residency training programs, while 29% disagreed with the notion. Thirty-eight percent welcomed the idea of increased rotation time on health advocacy specific experiences, although an equal number of respondents (36%) felt that such a rotation would not be beneficial. Less than one-half of respondents (46%) felt that formal health advocacy training would be meritorious as it pertains to their future practice.

Residents who stated a preference for a community-based practice tended to report that they had more formal training in health advocacy in their program (r = 0.48, p = 0.03). They were also more likely to have participated in health advocacy groups in their community (r = 0.48, p = 0.001). Those who agreed that health advocacy would play a significant role in their future practice noted that they had had formal training in it during residency (r = 0.46, p = 0.01), that they had a health advocacy role model (r = 0.42, p = 0.03) and that they would like to spend time on local rotations concentrating on health advocacy (r = 0.45, p = 0.02). Respondents who felt health advocacy training should be a mandatory part of residency reported having a mentor (r = 0.49, p = 0.01) and having had formal training in health advocacy during residency (r = 0.45, p = 0.02).

Discussion

Through new initiatives and perspectives in medical education, the notion of expanded physician roles or competencies has gained a foothold and has become part of individual resident training and evaluation as well as residency program accreditation.1,2,3 Such a role exhorts the physician to partake in health promotion and disease prevention strategies, to help the patient to access and navigate the often complex broader health care system and to help modify the social and biological determinants of health. This survey of senior residents in Canadian urology training programs was intended to identify awareness of and attitudes toward the role of the health advocate in urology, a role that is among the least well understood.4,5 Several interesting and enlightening observations have been made.

Residents are aware of the concept of health advocacy, as defined by CanMEDS, in their training; however, it is of concern that 1 in 5 PGY-5 residents in urology programs stated that they were not aware of this definition of the role, despite likely having been officially evaluated within its framework. In addition, there was a general appreciation of the merits of the role as it pertains to the physician as a health care practitioner and community member. Two-thirds of respondents agreed that there is a personal obligation to participate in health advocacy activities as a physician and surgeon.

Despite this appreciation of health advocacy's presence and importance, there is a dearth of participation in advocacy-related activity among this cohort of trainees, both before and during residency. This may relate to the revelation that there is a perceived lack of availability of resources and formal training in health advocacy and a perception that mentoring and staff participation are lacking. This has been suggested in a previous study, which suggested that while attending staff feel that they are actively participating in health promotion and other advocacy activities, their trainees are not seeing or appreciating this is happening.4

Another interesting finding of our survey is that the residents who acknowledge health advocacy is important and relevant but feel they are suboptimally trained are not particularly willing to support an increase in formal training activities. Nearly equal numbers of respondents support increased time devoted to health advocacy as feel that this is not desirable.

The etiology of this disconnect is not clear, and it is likely multifactorial. There is certainly a significant experiential and academic burden in specialty residency training, and it may be that given a fixed amount of time available in training that residents feel they cannot afford to lose time spent on the well-appreciated medical expert role. Verma and colleagues have described a notion that health advocacy amounts to “charity work” and thus is somehow less deserving of attention.4 A lack of mentorship and formal training may foment a laissez-faire attitude; or residents may feel that the practicalities of health advocacy participation are not teachable in a formal didactic or Socratic sense.

Correlative analysis yielded some insight as well. It showed an agreement between formal training and individual mentorship during the urology residency and an attitude that supports the integration of health advocacy into residency and urological practice. This suggests that those residents who are adequately exposed to the concept of health advocacy in training develop a more positive attitude and likely a greater desire to further promote it. This would seem to potentially bridge the gap between acknowledgement and integration of health advocacy otherwise demonstrated in the survey results.

Our study was conducted with the participation of PGY-5 urology residents. This may not be a fully representative sample of postgraduate trainees, and we acknowledge that this survey was conducted within several months of their RCPSC certification exams, and therefore their focus may have been on the “medical expert” aspects of their specialty. This may be countered by the fact that these residents had been part of postgraduate training for more than 4 years and as such had been maximally exposed to the range and scope of their discipline. They were also close to the beginning of independent practice, when these roles and competencies are expected to become integrated into their practice.

Although residents acknowledge the importance of their role as advocate and appreciate that it is part of their evaluation process, there appears to be a scarcity of formal training and participation in advocacy-related activities. Further, the residents we surveyed reported significant ambivalence with respect to their interest in more dedicated training time spent on health advocacy. This survey highlights the difficulties of determining the appropriate type and amount of training and evaluation required in these expanded physician roles in our formal training objectives in Canada.

Appendix

Appendix 1.

Health advocacy in urology training survey

Footnotes

This article has been peer reviewed.

Competing interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Frank J, Jabbour M, Tugwell P, et al. Skills for the new millenium: report of the societal needs working group, CanMEDS 2000 Project. Ann R Coll Physicians Surg Can 1996;29:206-16. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Outcome Project. Available: www.acgme.org/outcome/ (accessed 2006 Nov 30). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Frank JR, ed. The CanMEDS 2005 physician competency framework. Better standards. Better physicians. Better care Ottawa: Royal College of Physicians and Surgeons of Canada; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verma S, Flynn L, Seguin R. Faculty's and residents' perceptions of teaching and evaluating the role of health advocate: a study at one Canadian university. Acad Med 2005;80:103-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Frank J, Cole G, Lee C, et al. Progress in paradigm shift: the RCPSC CanMEDS Implementation Survey Paper presented at: Annual Meeting of the Association of Canadian Medical Colleges; April 26–29, 2003; Québec City. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oandasan IF. Health advocacy: bringing clarity to educators through the voices of physician health advocates. Acad Med 2005;80(10 Suppl):S38-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freiman A, Natsheh A, Barankin B, et al. Dermatology postgraduate training in Canada: CanMEDS competencies. Dermatol Online J 2006;12:6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]