Abstract

The Aspergillus nidulans putative mitogen-activated protein kinase encoded by mpkB has a role in natural product biosynthesis. An mpkB mutant exhibited a decrease in sterigmatocystin gene expression and low mycotoxin levels. The mutation also affected the expression of genes involved in penicillin and terrequinone A synthesis. mpkB was necessary for normal expression of laeA, which has been found to regulate secondary metabolism gene clusters.

In eukaryotes, the mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase signaling transduction pathways convey a variety of exterior information to nuclear targets to regulate cell growth and differentiation (1, 2, 18, 19). In Saccharomyces cerevisiae, FUS3 is a MAP kinase that regulates mating. Homologs of FUS3 have also been characterized in other filamentous fungi (12, 14, 16, 22, 26, 27, 29, 30, 31, 32, 36, 37, 40, 41, 42, 46).

Cell differentiation or development is often associated with biosynthesis of natural products (10). Although a regulatory role for MAP kinases in fungal morphogenesis has been established (22, 27, 34, 41, 42), only one study of a MAP kinase (homologous to S. cerevisiae SLT2 in Fusarium graminearum) affecting toxin production has been reported previously (21). The possible role of MAP kinases in fungal secondary metabolism remains obscure, and the implications of FUS3 homologs for natural product biosynthesis have not been investigated. Aspergillus nidulans is a model filamentous fungus used to study regulation of development and secondary metabolism (10, 44). We recently reported that a mutation in mpkB, encoding the FUS3 putative homolog in A. nidulans, blocked sexual development (34). A. nidulans is also known to generate diverse natural products, including the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin (ST), penicillin (PN), and the antitumor compound terrequinone A (10, 24, 39, 44). In this study, we investigated the role of mpkB in the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites. This is the first study reporting the role of Aspergillus MAP kinase signaling pathways in the regulation of fungal natural product biosynthesis.

Phylogenetic analysis.

Protein sequence alignment and phylogenetic analysis were performed using CLUSTAL W. A phylogenetic tree was visualized using TREEVIEW (33).

Growth conditions.

The strains used are listed in Table 1. Conidia (106 spores/ml) were inoculated into 500-ml flasks containing 200 ml liquid GMM (9) plus supplements (23) and incubated at 37°C at 300 rpm for 18 h. Approximately 3 g of filtered mycelium from each strain was spread on solid GMM and allowed to grow in the dark at 37°C. At 8, 20, and 30 h after the shift, mycelial samples were collected for ST analysis and mRNA analysis of ST genes. The same culture conditions were also used to analyze tdiA and tdiB expression.

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this study

Mycotoxin analysis.

ST extraction was carried out as described by Hesseltine et al. (20), with some modifications. Twenty milligrams of dried mycelia was ground and mixed with 1 ml of methanol-4% NaCl (55:45, vol/vol). After 20 min of incubation at room temperature, mixtures were centrifuged, and the supernatant was extracted with chloroform. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) analysis was performed as previously described (24).

PN analysis.

The culture conditions and bioassay used to quantify PN production were the same as those previously described by Brakhage et al. (7); Bacillus calidolactis C953 (a gift from Geoffrey Turner) was used as the test organism.

qRT-PCR analysis.

RNA extraction was carried out as previously described (38). Four micrograms of total RNA was treated with DNase I RQI (Promega) and reverse transcribed using Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega). Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with an Mx3000P thermocycler (Stratagene), using SYBR green JumpStart Taq Ready Mix (Sigma) and the primers shown in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Primers used in qRT-PCR analysis

| Primer | Sequence |

|---|---|

| actinF | 5′-ATGGAAGAGGAAGTTGCTGCTCTCGTTATCGACAATGGTTC-3′ |

| actinR | 5′-CAATGGAGGGGAAGACGGCACGGG-3′ |

| stcE-F | 5′-GATCGAAGTCCGATCCCGCCGAC-3′ |

| stcE-R | 5′-GTGGATCTTGCGCACCAGATAGCAGG-3′ |

| stcU-F | 5′-CATGTCAAGGACGTTACGCCAGATGAATTCGACCGAGTATTTCGGGTC-3′ |

| stcU-R | 5′-GCGGCACACTCATCCACCTGCTCATC-3′ |

| aflR-F | 5′-ATGGAGCCCCCAGCGATCAGCCAG-3′ |

| aflR-R | 5′-TTGGTGATGGTGCTGTCTTTGGCTGCTCAAC-3′ |

| ipnA-F | 5′-TCCCTACCCCGAGGCTGCTATCAAGACG-3′ |

| ipnA-R | 5′-CATTTCACCCGATGGATGGGCGCTTT-3′ |

| acvA-F | 5′-GACAAGGACAGACCGTGATGCAGGAGA-3′ |

| acvA-R | 5′-CCCGACGCAGCCTTAGCGAACAAGAC-3′ |

| aatA-F | 5′-GCTGCGCATGGCCCTCGAAAGTAC-3′ |

| aatA-R | 5′-GCCTTCCGGCCCACATGATCGAAGAC-3′ |

| tdiA-F | 5′-CCGATGCCTGGAGTGCGAATGCG-3′ |

| tdiA-R | 5′-TCTGCGCCTGCTCGAGAGCAGCATC-3′ |

| tdiB-F | 5′-GCTACCTGCACACGAGCAGCAACA-3′ |

| tdiB-R | 5′-GCGCTCTCAAAGTTCCGCTCAGCG-3′ |

| laeA-F | 5′-CATGAGCCCTATGTATAGCAACAATTCCGAGCGAAACCAG-3′ |

| laeA-R | 5′-ACCTCGATCGCCCAGATACCAGTTCCAC-3′ |

Our BLAST search and phylogenetic analysis revealed an identity of 60% and a similarity of 78% between A. nidulans MpkB and S. cerevisiae FUS3 (see Fig. S1A and B in the supplemental material). The phylogenetic tree of FUS3 homologs revealed that A. nidulans MpkB grouped with other homologs from the genus Aspergillus (see Fig. S1B in the supplemental material).

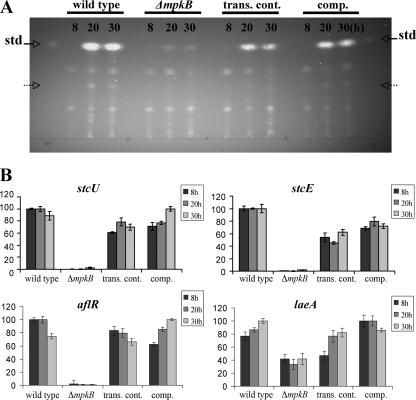

We recently reported that an mpkB mutant of A. nidulans fails to develop sexual structures (34). Previous studies have shown that some developmental genes also regulate mycotoxin production (10, 44). In this study we evaluated the effect of the mpkB mutation on ST biosynthesis in A. nidulans. Our TLC analysis revealed that the mpkB mutant strain produced low levels of ST compared with the levels produced by the control strains over time (Fig. 1A). At 20 h ST had clearly accumulated in the control strains, while only trace amounts of ST were observed in the mutant strain under the experimental conditions assayed. In this study we also evaluated the effect of the mpkB mutation on the ST transcriptional regulator gene, aflR (11, 43, 45), as well as the expression of two structural genes, stcE and stcU (8), as indicators of cluster activation (Fig. 1B). qRT-PCR analysis of aflR, stcU, and stcE expression showed a drastic reduction in transcription levels (Fig. 1B). The wild-type phenotype for both gene expression levels and ST production was almost fully restored in the complemented strain.

FIG. 1.

TLC analysis of ST (A) and qRT-PCR analysis of expression of the stcU, stcE, aflR, and laeA genes (B). Mycelial samples were harvested for ST extraction, and mRNA was analyzed at 8, 20, and 30 h after a shift onto GMM plates. The tested strains were wild-type strain TN02A7, ΔmpkB mutant TNK7.3.6, isogenic transformation control strain TNK7.6.7 (trans. cont.), and complementation strain TDB1.1 (comp.). std, ST standard. The relative expression levels were calculated using the  method (28), and all values were normalized to expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates. The dashed arrows indicate additional unknown metabolites whose production was affected by the mpkB mutation.

method (28), and all values were normalized to expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates. The dashed arrows indicate additional unknown metabolites whose production was affected by the mpkB mutation.

Our TLC analysis also indicated a different profile for other metabolites that were produced at lower levels in the mpkB mutant than in the control strains. This suggests that mpkB could have a broader effect (direct or indirect) on multiple metabolic pathways (Fig. 1A). For this reason we looked at the possible effect of the mpkB mutation on PN biosynthesis. The mpkB mutation resulted in a drastic decrease in PN biosynthesis (which was approximately sevenfold less than that of controls) (Fig. 2). Next, we analyzed the expression levels of the PN genes, acvA, ipnA, and aatA. We found that the mpkB mutation resulted in a decrease in the transcription of the analyzed genes (Fig. 2C). It is known that the expression of acvA is the rate-limiting step in PN biosynthesis (17). In our study acvA transcription was most affected by the mpkB mutation (>50% decrease). Alteration of PN gene expression, particularly in the case of acvA, could cause the reduction in PN production observed in the mpkB mutant (Fig. 2B).

FIG. 2.

PN bioassays and PN gene expression. (A) Effect of fungal extracts on the growth of B. calidolactis C953. Spots a, c, e, and g contained extracts from wild-type strain TN02A7, ΔmpkB mutant TNK7.3.6, isogenic transformation control strain TNK7.6.7 (trans. cont.), and complementation strain TDB1.1 (comp.), respectively. Spots b, d, f, and h contained to the same extracts mixed with 5 U of penicillase. (B) PN production, expressed in micrograms per milliliter of culture supernatant. Commercial PN G (Sigma) was used as the standard. (C) Expression levels of the PN biosynthesis genes acvA, ipnA, aatA, and laeA. The relative expression levels were calculated using the  method (28), and all values were normalized to the expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates.

method (28), and all values were normalized to the expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates.

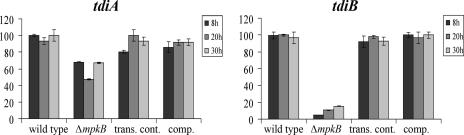

We also investigated the effect of the mpkB mutation on the expression of tdiA and tdiB, which are required for terrequinone A biosynthesis (5, 39). Our experiments revealed that the mpkB mutant showed a dramatic reduction in the expression of tdiB and a slight reduction in the expression of tdiA (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Expression levels of the terrequinone A biosynthetic genes, tdiA and tdiB. The relative expression levels were calculated using the  method (28), and all values were normalized to the expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates. trans. cont., transformation control strain; comp., complementation strain.

method (28), and all values were normalized to the expression of the A. nidulans actin gene. The error bars indicate the ranges for three replicates. trans. cont., transformation control strain; comp., complementation strain.

In the conserved pheromone response MAP kinase pathway, characterized in detail in S. cerevisiae, FUS3 kinase activates Ste12. Activated Ste12 is able to bind and induce the expression of pheromone-responsive genes (13). We found a putative ste12/steA binding site in the promoter of the A. nidulans hapE gene (position −408). Expression of PN biosynthesis enzyme genes is regulated by HAP-like complexes (3, 6). It is possible that mpkB-dependent steA regulation of PN gene expression could be at least in part mediated by the HAP complex. Additionally, we found another putative ste12/steA binding site directly in the divergently oriented and shared acvA-ipnA promoter (position −343 with respect to the acvA translation start site).

Interestingly, our study indicated that mpkB affects the expression of laeA (Fig. 1B and 2C). The latter gene encodes a putative methyltransferase known to regulate secondary metabolic gene clusters in Aspergillus (4, 25, 35), including ST, PN, and terrequinone A gene clusters. These findings suggest that the effect of mpkB on the transcription of genes involved in secondary metabolism could be at least in part influenced through the regulation of laeA transcription. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that the FUS3-like signaling pathway in A. nidulans not only regulates morphological differentiation in response to environmental stimuli but also modulates the biosynthesis of different natural products, adapting to environmental variations. Due to the high level of conservation among FUS3 homologs, it is likely that this signaling pathway could also control secondary metabolism in other fungal species.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by Northern Illinois University.

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 31 March 2008.

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://aem.asm.org/.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banuett, F. 1998. Signaling in the yeasts: an informational cascade with links to the filamentous fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:249-274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bardwell, L. 2006. Mechanisms of MAPK signaling specificity. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 34:837-841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bergh, K. T., O. Litzka, and A. A. Brakhage. 1996. Identification of a major cis-acting DNA element controlling the bidirectionally transcribed penicillin biosynthesis genes acvA (pcbAB) and ipnA (pcbC) of Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 178:3908-3916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bok, J. W., and N. P. Keller. 2004. LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp. Eukaryot. Cell 3:527-535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bouhired, S., M. Weber, A. Kempf-Sontag, N. P. Keller, and D. Hoffmeister. 2007. Accurate prediction of the Aspergillus nidulans terrequinone gene cluster boundaries using the transcriptional regulator LaeA. Fungal Genet. Biol. 44:1134-1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brakhage, A. A., A. Andrianopoulos, M. Kato, S. Steidl, M. A. Davis, N. Tsukagoshi, and M. J. Hynes. 1999. HAP-like CCAAT-binding complexes in filamentous fungi: implications for biotechnology. Fungal Genet. Biol. 27:243-252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brakhage, A. A., P. Browne, and G. Turner. 1992. Regulation of Aspergillus nidulans penicillin biosynthesis and penicillin biosynthesis genes acvA and ipnA by glucose. J. Bacteriol. 174:3789-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brown, D. W., J. H. Yu, H. S. Kelkar, M. Fernandes, T. C. Nesbitt, N. P. Keller, T. H. Adams, and T. J. Leonard. 1996. Twenty-five coregulated transcripts define a sterigmatocystin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1418-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Calvo, A. M., H. W. Gardner, and N. P. Keller. 2001. Genetic connection between fatty acid metabolism and sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25766-25774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvo, A. M., R. A. Wilson, J. W. Bok, and N. P. Keller. 2002. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:447-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chang, P. K., J. Yu, D. Bhatnagar, and T. E. Cleveland. 2000. Characterization of the Aspergillus parasiticus major nitrogen regulatory gene, areA. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1491:263-266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen, C., A. Harel, R. Gorovoits, O. Yarden, and M. B. Dickman. 2004. MAPK regulation of sclerotial development in Sclerotinia sclerotiorum is linked with pH and cAMP sensing. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 17:404-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chou, S., S. Lane, and H. Liu. 2006. Regulation of mating and filamentation genes by two distinct Ste12 complexes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. Biol. 26:4794-4805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cousin, A., R. Mehrabi, M. Guilleroux, M. Dufresne, T. Van der Lee, C. Waalwijk, T. Langin, and G. H. J. Kema. 2006. The MAP kinase-encoding gene MgFus3 of the non-appressorium phytopathogen Mycosphaerella graminicola is required for penetration and in vitro pycnidia formation. Mol. Plant Pathol. 7:269-278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reference deleted.

- 16.Di Pietro, A., F. I. Garcia-MacEira, E. Meglecz, and M. I. Roncero. 2001. A MAP kinase of the vascular wilt fungus Fusarium oxysporum is essential for root penetration and pathogenesis. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1140-1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dreyer, J., H. Eichhorn, E. Friedlin, H. Kurnsteiner, and U. Kuck. 2007. A homolog of the Aspergillus velvet gene regulates both cephalosporin C biosynthesis and hyphal fragmentation in Acremonium chrysogenum. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 73:3412-3422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gustin, M. C., J. Albertyn, M. Alexander, and K. Davenport. 1998. MAP kinase pathways in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:1264-1300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herskowitz, I. 1995. MAP kinase pathways in yeast: for mating and more. Cell 80:187-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hesseltine, C. W., O. L. Shotwell, J. J. Ellis, and R. D. Stubblefield. 1966. Aflatoxin formation by Aspergillus flavus. Bacteriol. Rev. 30:795-805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hou, Z., C. Xue, Y. Peng, T. Katan, H. C. Kistler, and J. R. Xu. 2002. A mitogen-activated protein kinase gene (MGV1) in Fusarium graminearum is required for female fertility, heterokaryon formation, and plant infection. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 15:1119-1127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jenczmionka, N. J., F. J. Maier, A. P. Losch, and W. Schafer. 2003. Mating, conidiation and pathogenicity of Fusarium graminearum, the main causal agent of the head-blight disease of wheat, are regulated by the MAP kinase gpmk1. Curr. Genet. 43:87-95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Käfer, E. 1977. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv. Genet. 19:33-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kato, N., W. Brooks, and A. M. Calvo. 2003. The expression of sterigmatocystin and penicillin genes in Aspergillus nidulans is controlled by veA, a gene required for sexual development. Eukaryot. Cell 2:1178-1186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Keller, N. P., J. Bok, D. Chung, R. M. Perrin, and E. Keats Shwab. 2006. LaeA, a global regulator of Aspergillus toxins. Med. Mycol. 44(Suppl.):83-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lev, S., A. Sharon, R. Hadar, H. Ma, and B. A. Horwitz. 1999. A mitogen-activated protein kinase of the corn leaf pathogen Cochliobolus heterostrophus is involved in conidiation, appressorium formation, and pathogenicity: diverse roles for mitogen-activated protein kinase homologs in foliar pathogens. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 96:13542-13547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li, D., P. Bobrowicz, H. H. Wilkinson, and D. J. Ebbole. 2005. A mitogen-activated protein kinase pathway essential for mating and contributing to vegetative growth in Neurospora crassa. Genetics 170:1091-1104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Livak, K. J., and T. D. Schmittgen. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCt method. Methods 25:402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mayorga, M. E., and S. E. Gold. 1999. A MAP kinase encoded by the ubc3 gene of Ustilago maydis is required for filamentous growth and full virulence. Mol. Microbiol. 34:485-497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mey, G., K. Held, J. Scheffer, K. B. Tenberge, and P. Tudzynski. 2002. CPMK2, an SLT2-homologous mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase, is essential for pathogenesis of Claviceps purpurea on rye: evidence for a second conserved pathogenesis-related MAP kinase cascade in phytopathogenic fungi. Mol. Microbiol. 46:305-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moriwaki, A., J. Kihara, C. Mori, and S. Arase. 2007. A MAP kinase gene, BMK1, is required for conidiation and pathogenicity in the rice leaf spot pathogen Bipolaris oryzae. Microbiol. Res. 162:108-114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mukherjee, P. K., J. Latha, R. Hadar, and B. A. Horwitz. 2003. TmkA, a mitogen-activated protein kinase of Trichoderma virens, is involved in biocontrol properties and repression of conidiation in the dark. Eukaryot. Cell 2:446-455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32a.Nayak, T., E. Szewczyk, C. E. Oakley, A. Osmani, L. Ukil, S. L. Murray, M. J. Hynes, S. A. Osmani, and B. R. Oakley. 2006. A versatile and efficient gene-targeting system for Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 172:1557-1566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Page, R. D. M. 1996. TREEVIEW: an application to display phylogenetic trees on personal computers. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 12:357-358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Paoletti, M., F. A. Seymour, M. J. Alcocer, N. Kaur, A. M. Calvo, D. D. Archer, and P. S. Dyer. 2007. Mating type and the genetic basis of self-fertility in the model fungus Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Biol. 17:1384-1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Perrin, R. M., N. D. Fedorova, J. W. Bok, R. A. Cramer, J. R. Wortman, H. S. Kim, W. C. Nierman, and N. P. Keller. 2007. Transcriptional regulation of chemical diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus by LaeA. PLoS Pathog. 3:0508-0517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rauyaree, P., M. D. Ospina-Giraldo, S. Kang, R. G. Bhat, K. V. Subbarao, S. J. Grant, and K. F. Dobinson. 2005. Mutations in VMK1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, affect microsclerotia formation and pathogenicity in Verticillium dahliae. Curr. Genet. 48:109-116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ruiz-Roldan, M. C., F. J. Maier, and W. Schafer. 2001. PTK1, a mitogen-activated protein kinase gene, is required for conidiation, appressorium formation and pathogenicity of Pyrenophora teres on barley. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 14:116-125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sambrook, J., E. F. Fritsch, and T. Maniatis. 1989. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual, 2nd ed. Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, Cold Spring Harbor, NY.

- 39.Schneidera, P., M. Webera, and D. Hoffmeister. 2008. The Aspergillus nidulans enzyme TdiB catalyzes prenyltransfer to the precursor of bioactive asterriquinones. Fungal Genet. Biol. 45:302-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Solomon, P. S., O. D. Waters, J. Simmonds, R. M. Cooper, and R. P. Oliver. 2005. The Mak2 MAP kinase signal transduction pathway is required for pathogenicity in Stagonospora nodorum. Curr. Genet. 48:60-68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Takano, Y., T. Kikuchi, Y. Kubo, J. E. Hamer, K, Mise, and I. Furusawa. 2000. The Colletotrichum lagenarium MAP kinase gene CMK 1 regulates diverse aspects of fungal pathogenesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:374-383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xu, J. R., and J. E. Hamer. 1996. MAP kinase and cAMP signaling regulate infection structure formation and pathogenic growth in the rice blast fungus Magnaporthe grisea. Genes Dev. 10:2696-2706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yu, J., P. K. Chang, K. C. Ehrlich, J. W. Cary, D. Bhatnagar, T. E. Cleveland, G. A. Payne, J. E. Linz, C. P. Woloshuk, and J. W. Bennett. 2004. Clustered pathway genes in aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70:1253-1262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yu, J. H., and N. P. Keller. 2005. Regulation of secondary metabolism in filamentous fungi. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 43:437-458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu, J. H., R. A. Butchko, M. Fernandes, N. P. Keller, T. J. Leonard, and T. H. Adams. 1996. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr. Genet. 29:549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zheng, L., M. Campbell, J. Murphy, S. Lam, and J. R. Xu. 2000. The BMP1 gene is essential for pathogenicity in the gray mold fungus Botrytis cinerea. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 13:724-732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhuang, L., J. Zhang, and X. Xiang. 2007. Point mutations in the stem region and the fourth AAA domain of cytoplasmic dynein heavy chain partially suppress the phenotype of NUDF/LIS1 loss in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 175:1185-1196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.