Abstract

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is the causative agent of tuberculosis, a disease that affects one-third of the world's population. The sole extant vaccine for tuberculosis is the live attenuated Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG). We examined 13 representative BCG strains from around the world to ascertain their ability to express DosR-regulated dormancy antigens. These are known to be recognized by T cells of M. tuberculosis-infected individuals, especially those harboring latent infections. Differences in the expression of these antigens could be valuable for use as diagnostic markers to distinguish BCG vaccination from latent tuberculosis. We determined that all BCG strains were defective for the induction of two dormancy genes: narK2 (Rv1737c) and narX (Rv1736c). NarK2 is known to be necessary for nitrate respiration during anaerobic dormancy. Analysis of the narK2/X promoter region revealed a base substitution mutation in all tested BCG strains and M. bovis in comparison to the M. tuberculosis sequence. We also show that nitrate reduction by BCG strains during dormancy was greatly reduced compared to M. tuberculosis and varied between tested strains. Several dormancy regulon transcriptional differences were also identified among the strains, as well as variation in their growth and survival. These findings demonstrate defects in DosR regulon expression during dormancy and phenotypic variation between commonly used BCG vaccine strains.

Tuberculosis (TB) continues to have a serious impact on global health, with 8.8 million new cases reported in 2005 giving rise to 1.6 million deaths, or roughly 4,400 deaths per day. An estimated one-third of the world's population is currently infected with latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis, and ca. 10% of those will reactivate with acute disease. In addition, multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant TB cases are on the rise, exacerbating the present difficulties in managing and resolving the issue (42).

The live attenuated vaccine strain Mycobacterium bovis bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) still remains the sole available vaccine for TB (3). Despite its widespread use, clinical trials have shown that it provides variable levels of protection against pulmonary TB, the most common and contagious form of TB, with protective values ranging from 0 to 80% (10). Part of the reason for this variability may be the genetic diversity that exists between BCG daughter vaccine strains in current usage throughout the world. Several genetic and protective studies have been performed and show variability among various vaccine strains (3, 4, 6). An additional problem with BCG vaccination is that its use is not free of health complications. In immunocompromised populations disseminated BCG infection may occur, albeit rarely, with high mortality rates (22). This is becoming a greater problem with the increasing number of people coinfected with M. tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus (42).

Mycobacteria are strict aerobes, but during the course of human infection they are believed to encounter a microaerobic or anaerobic environment in mature granulomas. The utilization of anaerobic respiratory pathways can help to explain the ability of M. tuberculosis to survive in low-oxygen microenvironments. M. tuberculosis is able to reduce nitrate to nitrite, using nitrate as a terminal electron acceptor in respiration; this activity dramatically increases upon entry into the anaerobic dormant state (17, 34, 38, 40, 41). Various and sometimes conflicting results regarding the ability and temporal occurrence of nitrate reduction by BCG and M. bovis have been reported (15, 17, 31-34, 41). This may be due to different bacterial strains and culture methods used in these studies. Several genes in the mycobacterial genome encode proteins that play a role in nitrate reduction, and the most extensively studied of these systems is the narGHJI nitrate reductase operon (9). Mutations in the promoter region of narGHJI cause differences in the ability of various mycobacterial species to reduce nitrate (32). There is also a link between nitrate reduction and pathogenicity, shown by reduced disease and bacterial persistence when a narG-null mutant of M. tuberculosis was used to infect mice (41).

The dormancy regulon, regulated by DosR, is expressed in response to hypoxia, nitric oxide, and carbon monoxide and is thought to be important for long-term survival in the host (20, 29, 36). The immune response to dormancy proteins has been the subject of several recent reports, and it appears that this response has a role in the maintenance of latent M. tuberculosis infection (21, 28). The most strongly expressed dormancy antigens were tested for immunogenicity in M. tuberculosis-infected individuals (21) and mice (28). It was shown that these antigens are preferentially recognized by T cells from individuals with latent infection compared to TB patients with active disease (21). Reminiscent of this finding is the reported dichotomy between a dormancy regulon protein alpha-crystallin (Acr or HspX) (11, 36) and secreted antigens such as the Ag85 complex and members of the ESAT-6 family. A strong response to Acr is most closely linked to latently infected individuals, while a strong response to Ag85 and ESAT-6 is associated with TB disease (11). It is therefore tempting to speculate that immune responses to dormancy antigens could contribute to protective immunity against M. tuberculosis.

Differences between BCG vaccine strains with respect to reactogenicity, immunogenicity, and protective efficacy have previously been observed, but the molecular underpinning remains elusive (13). It is conceivable that transcriptional variability among the genes of the dormancy regulon between BCG strains could cause phenotypic variability and, as a result, protective differences. To approach this, as well as to look for differences in expression that could be used as diagnostic markers for latent TB verses BCG vaccination, 13 BCG vaccine strains used around the world were assayed to determine their ability to induce the dormancy regulon. A representative subset of BCG strains was further studied for their ability to reduce nitrate and survive during anaerobic dormancy. Among the transcriptional differences observed, only two genes, narK2 and narX, were consistently not induced among all of the BCG strains and M. bovis. The function of narX is unknown, although it has been annotated as a “fused nitrate reductase” due to its homology to nitrate reductase genes in other organisms. However, a previous study showed that the ability to reduce nitrate aerobically and anaerobically is unaffected by the absence of narX (9). In contrast, the disruption of narK2, a putative nitrate/nitrite transporter, is required to reduce nitrate anaerobically (31).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and culture conditions.

M. tuberculosis wild-type strain H37Rv, M. bovis strain AN5, and the following BCG strains were obtained from the Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials contract (Colorado State University). In parentheses are synonymous names for the BCG strains (3): Connaught JPG, Pasteur 140, Sweden (Gothenburg), Connaught (Toronto), Japan (Tokyo), Canada, Vietnam, Denmark, Russia, Brazil (Moreau), Tice (Chicago), Moscow, and Pasteur 133A. To initiate dormancy, cultures were grown using the Wayne anaerobic dormancy model as previously described (37, 39). Sealed culture tubes from the model were assayed for optical density at 600 nm. A minimum of five tubes for each time point were assayed in three independent trials. For CFU assays, at least three different culture tubes from each time point were plated on Dubos Tween albumin agar (Becton Dickinson) in quadruplicate. Colonies were counted after 2 to 3 weeks of incubation at 37°C. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Microarray analysis.

M. tuberculosis oligonucleotide-based microarrays were obtained from Colorado State University. Microarray analysis and treatment of bacterial cultures for induction of the dormancy regulon were performed as previously described (36). Briefly, bacterial strains were either exposed to 0.1 mM nitric oxide donor diethylenetriamine/nitric oxide adduct (Sigma) for 1 h or cultured for 4 h under anaerobic conditions. Anaerobic conditions were achieved by using BD BBL GasPak Plus envelopes in a sealed container. RNA was extracted from these bacterial cultures, and cDNA was prepared and labeled (36). The data shown represent the averages of at least one anaerobic and one nitric oxide-treated experiment. Arrays were scanned with a GenePix 4000b scanner (Molecular Devices), and spot intensities were obtained by using Scanalyze (M. Eisen, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory). Induction ratios were determined after processing the data as previously described (36). Microarray data are available on the NCBI Gene Expression Omnibus (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/).

Nitrate reduction assays.

To enable nitrate reduction, 10 mM NaNO3 was added to the culture medium at the beginning of the Wayne anaerobic dormancy model before the tubes were sealed. Each strain was tested for nitrate reduction by determination of the amount of nitrite present in the culture based on the Griess reaction as described previously (26). The presence of nitrite causes a color change in the Griess reagent that can be detected via spectroscopy. Cultures were grown three separate times and assayed at the time points indicated. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

Sequence analysis.

Sequence determination was conducted by the University of Colorado Cancer Center DNA Sequencing and Analysis Core. Primers were designed utilizing the FastPCR program (19) and their sequences are as follows: forward, TCCCCAAGTCGGACAAGG; and reverse, GCTGGACAGTGACATGTC. Sequence analysis was performed by using CLUSTAL W (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/clustalw/) (8). Sequence data for comparison and primer design was obtained from TubercuList (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/TubercuList/), BoviList (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/BoviList/), and BCGList (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/BCGList/) (9).

Real-time PCR.

Reverse transcriptase and quantitative real-time PCR were performed with gene-specific primers and probes designed using the programs FastPCR (19) and Primer3 (9). The primer and probe sequences were as follows: sigA, forward (CCTACGCTACGTGGTGGATTCG), reverse (TTTGGCCAGCTCCTCGGGCGT), and probe (CGAGGTGATCAACAAGCTGGGC); Rv2626c, forward (CCGCGACATTGTGATCAAAG), reverse (GCTCTGAGATGACCGGAACAC), and probe (CGAACGCAAGCATCCAGGAGATGC); narX, forward (GTGCCGTATGTGACGATGAC), reverse (GGATGCCGAAATGAAACATC), and probe (GCGCTACCGCTATGACAAAT); narK2, forward (GCTTCGTGATGCACCCTACT), reverse (TAGGTGGGCAGGTAGTTGCT), and probe (GTGACCTGGGAGATGTCGTT). Sequence data for primer design was obtained from TubercuList (9). Real-time PCR was performed on the Cepheid SmartCycler 2. A reverse transcriptase negative reaction was used to account for signal from residual DNA, and copy numbers were normalized to the number of sigA transcripts. For each strain, RNA samples from nitric oxide-treated cultures and log-phase control cultures were analyzed. RNA used was obtained through the same extraction procedure as noted for microarray analysis. Statistical significance was determined by using an unpaired Student t test. Error bars represent the standard deviation.

RESULTS

Dormancy regulon induction profiles.

We were interested in whether observable differences in gene expression existed between various BCG strains, M. bovis, and M. tuberculosis, and whether these differences could provide insight into the observed diversity in nitrate reduction, immunogenicity, and possibly vaccine protection. We specifically focused on the genes of the dormancy regulon because of their role in the immune response during latent M. tuberculosis infection. To facilitate this, microarray analysis was conducted on 13 different BCG strains, as well as M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. Bacterial cultures were exposed to either nitric oxide or hypoxia, conditions shown previously to induce the dormancy regulon (29, 36). Examination of the expression profiles of the dormancy regulon showed differences mainly among proteins of unknown function (Table 1 and Fig. 1). A variety of induction patterns can be observed, with some genes showing consistent expression between strains and others induced only in a few strains (Table 1). The induction levels of Rv0081, Rv0573c, Rv1735c, Rv1736c, Rv1737c, Rv1998c, Rv2003c, Rv2631, Rv3126c, Rv3128c, and Rv3129 differed between strains. Overall, the induction of the regulon was comparable between the BCG strains and M. tuberculosis, with an average of 36.3 ± 7 compared to 39.4, respectively.

TABLE 1.

Dormancy regulon induction ratios

| Gene | Regulon induction ratioa for strain:

|

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rv | Bovis | Conn. Jpg | Past. 140 | Sweden | Conn. | Japan | Vietnam | Denmark | Russia | Brazil | Tice | Moscow | Past. 133a | |

| Rv0079 | 20 | 23 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 19 | 21 | 25 | 28 | 38 | 20 | 14 | 17 | 15 |

| Rv0080 | 11 | 16 | 1 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 21 | 23 | 29 | 19 | 7.4 | 9.6 | 11 |

| Rv0081 | 3.3 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 5.7 | 5.9 | 2.4 | 8.1 | 6.1 | 11 | 3.1 | 6.7 | 7 | 3.4 |

| Rv0569 | 40 | 17 | 30 | 30 | 24 | 24 | 41 | 27 | 53 | 49 | 40 | 24 | 25 | 30 |

| Rv0570 | 18 | 12 | 18 | 9.7 | 21 | 19 | 15 | 23 | 29 | 33 | 16 | 16 | 19 | 14 |

| Rv0571c | 9.2 | 7.5 | 13 | 6.3 | 3.4 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 10 | 28 | 10 | 9.8 | 5.9 | 6 | 7.9 |

| Rv0572c | 14 | 10 | 7 | 9.7 | 10 | 9.6 | 15 | 5.8 | 11 | 23 | 12 | 5.1 | 7.6 | 9.9 |

| Rv0573c | 2.7 | 3.6 | 0.8 | 2.3 | 2.4 | 1 | 3.6 | 1.8 | 1.4 | 4 | 3.4 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 |

| Rv0574c | 8.2 | 6 | 4 | 2.9 | 9.4 | 3.7 | 7.7 | 4.1 | 14 | 11 | 4.9 | 2.3 | 3.5 | 3.4 |

| Rv1733c | 34 | 15 | 23 | 30 | 25 | 11 | 26 | 37 | 39 | 23 | 19 | 23 | 30 | 36 |

| Rv1734c | 1.9 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 0.9 | 2.6 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.2 | 2 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Rv1735c | 0.8 | 1 | 0.9 | 1 | 2.6 | 1 | 1.8 | 4 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.9 | 2.7 |

| Rv1736c | 27 | 1.3 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 1 |

| Rv1737c | 39 | 1 | 1 | 1.1 | 1.4 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Rv1738 | 62 | 33 | 63 | 51 | 29 | 29 | 56 | 71 | 63 | 73 | 68 | 22 | 79 | 63 |

| Rv1812c | 5.3 | 3.1 | 4.9 | 4 | 3.2 | 3.6 | 2.4 | 5.6 | 4.4 | 4 | 4.6 | 5 | 4.5 | 3.8 |

| Rv1813c | 120 | 85 | 75 | 67 | 120 | 120 | 85 | 110 | 110 | 160 | 95 | 100 | 120 | 94 |

| Rv1996 | 21 | 18 | 22 | 11 | 15 | 20 | 19 | 35 | 32 | 27 | 38 | 21 | 28 | 29 |

| Rv1997 | 43 | 49 | 64 | 9.1 | 70 | 45 | 23 | 64 | 46 | 53 | 48 | 50 | 58 | 46 |

| Rv1998c | 1.7 | 1.5 | 0.7 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 0.9 | 1 | 1.5 | 1.1 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.1 | 1.2 | 0.7 |

| Rv2003c | 12 | 7.5 | 7.8 | 1.6 | 2.4 | 6.6 | 1.4 | 15 | 4.1 | 6.1 | 8.3 | 10 | 6.7 | 6.3 |

| Rv2004c | 20 | 12 | 12 | 8.8 | 4.3 | 8.2 | 2.9 | 23 | 9.6 | 2 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 15 |

| Rv2005c | 18 | 23 | 36 | 23 | 29 | 26 | 27 | 36 | 45 | 35 | 17 | 31 | 29 | 29 |

| Rv2006 | 7.3 | 3.7 | 6.6 | 7.4 | 2.4 | 3.9 | 6.7 | 5.6 | 7.6 | 6.2 | 8.1 | 2.4 | 3.3 | 8.4 |

| Rv2007c | 34 | 55 | 41 | 45 | 44 | 53 | 75 | 42 | 62 | 62 | 33 | 76 | 38 | 45 |

| Rv2028c | 20 | 10 | 23 | 6.6 | 14 | 7.6 | 4.2 | 32 | 14 | 9.9 | 12 | 7.4 | 10 | 8.3 |

| Rv2029c | 38 | 48 | 69 | 28 | 52 | 34 | 84 | 57 | 91 | 110 | 67 | 26 | 39 | 49 |

| Rv2030c | 60 | 36 | 94 | 52 | 88 | 27 | 66 | 86 | 63 | 140 | 63 | 48 | 74 | 79 |

| Rv2031c | 150 | 180 | 160 | 175 | 82 | 110 | 200 | 100 | 180 | 240 | 130 | 93 | 120 | 150 |

| Rv2032 | 65 | 73 | 62 | 57 | 69 | 66 | 89 | 100 | 80 | 98 | 75 | 47 | 98 | 78 |

| Rv2623 | 100 | 95 | 69 | 110 | 25 | 98 | 110 | 87 | 120 | 100 | 110 | 66 | 67 | 84 |

| Rv2624c | 32 | 17 | 29 | 28 | 40 | 16 | 34 | 34 | 32 | 71 | 34 | 29 | 55 | 42 |

| Rv2625c | 36 | 24 | 47 | 34 | 9.5 | 9.2 | 29 | 18 | 40 | 88 | 57 | 4.2 | 15 | 38 |

| Rv2626c | 260 | 260 | 190 | 220 | 180 | 160 | 250 | 2100 | 350 | 310 | 240 | 150 | 260 | 230 |

| Rv2627c | 57 | 56 | 74 | 58 | 17 | 43 | 72 | 130 | 75 | 100 | 86 | 35 | 51 | 75 |

| Rv2628 | 150 | 68 | 72 | 55 | 39 | 55 | 54 | 77 | 130 | 130 | 64 | 74 | 82 | 75 |

| Rv2629 | 14 | 11 | 14 | 12 | 18 | 4.1 | 11 | 7.2 | 8 | 12 | 11 | 5.9 | 5.4 | 12 |

| Rv2630 | 19 | 1.6 | 14 | 7 | 14 | 19 | 10 | 21 | 15 | 26 | 8.9 | 22 | 15 | 7.4 |

| Rv2631 | 2.2 | 0.8 | 9.2 | 4.9 | 2.6 | 2.1 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 2.2 | 3.2 | 3.1 | 5.1 | 2 | 4.1 |

| Rv3126c | 6.1 | 3.1 | 1.7 | 2.5 | 1 | 3.6 | 1.6 | 7.1 | 2.1 | 1.4 | 5.2 | 5.8 | 3.8 | 5.2 |

| Rv3127 | 49 | 41 | 61 | 17 | 37 | 39 | 15 | 63 | 60 | 47 | 37 | 54 | 50 | 41 |

| Rv3128c | 1.7 | 1.9 | 0.9 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.9 | 1.1 | 1.6 | 1.5 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.5 | 1 | 1.3 |

| Rv3129 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 1 | 1.4 | 1.7 | 1.1 | 1 | 1 | 1.2 | 1 | 1.1 |

| Rv3130c | 110 | 130 | 82 | 70 | 70 | 84 | 71 | 82 | 110 | 110 | 110 | 36 | 68 | 73 |

| Rv3131 | 52 | 48 | 44 | 34 | 29 | 42 | 40 | 62 | 32 | 47 | 56 | 40 | 79 | 55 |

| Rv3132c | 27 | 15 | 16 | 15 | 23 | 13 | 23 | 17 | 21 | 34 | 30 | 23 | 18 | 19 |

| Rv3133c | 13 | 14 | 24 | 17 | 25 | 23 | 29 | 24 | 33 | 35 | 21 | 21 | 27 | 27 |

| Rv3134c | 38 | 16 | 29 | 25 | 27 | 30 | 24 | 29 | 39 | 40 | 33 | 34 | 29 | 32 |

| Avgb | 39 | 34 | 36 | 30 | 29 | 29 | 36 | 40 | 46 | 52 | 38 | 28 | 37 | 36 |

Induction ratios are the average ratios from two microarray experiments, one hypoxia and one nitric oxide exposure. Uninduced values below twofold induction are indicated in boldface. Conn., Connaught; Past., Pasteur.

That is, the average induction value of all genes excluding Rv1736c and Rv1737c.

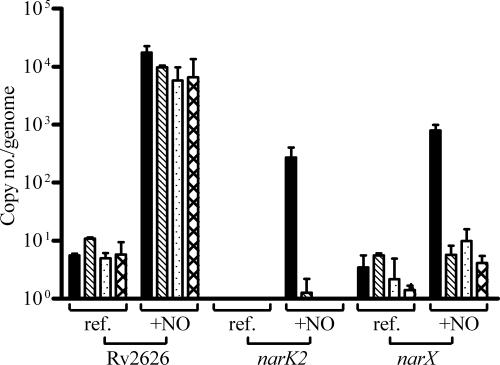

FIG. 1.

Induction of narK2 and narX transcription by nitric oxide. Quantitative reverse transcription-PCR was used to quantify transcript levels reported at copy number per genome of narK2, narX, and Rv2626 (as a positive control for general dormancy regulon gene expression). Bars: ▪, M. tuberculosis; ▧, M. bovis; ░⃞, BCG Connaught Jpg; ▩, BCG Pasteur 140.

The only genes that were consistently not induced by any of the 13 BCG strains nor by M. bovis but were induced by M. tuberculosis were Rv1736c (narX) and Rv1737c (narK2). The average BCG induction ratios for narX and narK2 were 1.0 ± 0.2 and 1.2 ± 0.2, respectively. In contrast, the induction ratios of these genes for M. tuberculosis were 27 and 39. As a result, further analysis of the expression and function of these genes was pursued.

Several dormancy genes (Rv1734c, Rv1735c, Rv1998c, Rv3128c, and Rv3129c) did not show significant induction in any of the BCG strains or M. tuberculosis. This conflicts with the previously published list of genes included in the dormancy regulon (36). However, it is likely this finding is a result of low level of induction of some of the genes and variability between micorarray platforms used in the different studies.

narK2 and narX transcript levels.

To confirm the array data for narK2 and narX, quantitative real-time PCR on four strains was performed with gene-specific primers and probes. M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and two representative BCG strains (Connaught JPG and Pasteur 140) were assayed. RNA samples were obtained from cultures treated with a nitric oxide donor to induce the dormancy regulon (36) and were compared to RNA from cultures grown in the absence of nitric oxide. An additional dormancy gene, Rv2626c, was monitored as a control for induction of the dormancy regulon and was selected based on microarray data showing that it was highly induced by nitric oxide in all strains investigated.

Rv2626c transcript levels were induced ∼1,000-fold in all four strains (Fig. 1), confirming that in general the dormancy regulon is induced when stimulated with nitric oxide. In contrast, M. bovis and the two BCG strains were not able to induce narK2 or narX in the presence of nitric oxide, whereas M. tuberculosis induced narK2 and narX 270- and 800-fold, respectively. The differences between expression levels were statistically significant, as determined by using the Student t test. P values between the expression levels of M. tuberculosis and the various other strains were 0.03 and 0.05 for narX and narK2, respectively. These data are consistent with the microarray data.

Nitrate reduction ability.

Previous studies that document the ability of M. bovis and BCG to reduce nitrate have been inconsistent as a result of differences in the strains tested, culture conditions used, and the experiment time frame (15, 17, 31-34, 41). We compared six BCG strains, M. tuberculosis, and M. bovis to determine whether their ability to reduce nitrate under dormancy conditions, simulated by the Wayne anaerobic dormancy model (37, 39), correlated with the microarray expression data. By day 4 of the dormancy model, at which point oxygen has become limiting, M. tuberculosis had already reduced a significant amount of nitrate, shown by the presence of ∼40 μM nitrite in the medium (Table 2). Nitrate continued to be reduced rapidly until day 8, after which point nitrate reduction began to slow. Between days 8 and 12 the rate of reduction dropped significantly. This drop indicates a decrease in nitrate reduction performed by NarGHJI with transport via NarK2 under the hypoxic conditions (31, 32). M. bovis and the six BCG strains vary in their ability to reduce nitrate, although all of them exhibit much lower levels than M. tuberculosis. The low level or absence of nitrate reduction by M. bovis and the BCG strains is likely a result of defects in expression of the NarGHJI (32, 33) and NarK2 proteins. NarK2 is involved since it is required for transport of nitrate during anaerobic dormancy (31). It is interesting that M. bovis, BCG Pasteur 140, and BCG Russia appear to slowly reduce nitrate, despite the lack of induction of narK2/X. The ability to reduce even small amounts of nitrate by these strains may be a result of a basal level of expression of narK2 in the absence of DosR-mediated induction.

TABLE 2.

Nitrate reduction during anaerobic dormancya

| Strain | Mean nitrate induction (μM nitrate) ± SD at:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day 4 | Day 8 | Day 12 | Day 20 | |

| Rv | 41 ± 7.5 | 99 ± 7.7 | 110 ± 7.2 | 130 ± 14 |

| Bovis | 0.19 ± 0.08 | 0.78 ± 0.49 | 0.81 ± 0.64 | 1.1 ± 0.69 |

| Pasteur 140 | 0.25 ± 0.15 | 1.2 ± 0.46 | 2.8 ± 0.58 | 6.4 ± 1.3 |

| Russia | 0.060 ± 0.10 | 0.95 ± 0.63 | 1.7 ± 1.1 | 4.5 ± 1.2 |

| Connaught Jpg | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.024 ± 0.017 | 0.020 ± 0.011 |

| Vietnam | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 0.0 ± 0.0 | 2.7 ± 2.7 |

| Canada | 0.13 ± 0.15 | 0.54 ± 0.62 | 2.0 ± 2.2 | 1.5 ± 1.5 |

| Brazil | 0.30 ± 0.1 | 0.56 ± 0.36 | 2.9 ± 3.1 | 1.2 ± 1.0 |

Nitrate reduction was determined by assaying the amount of nitrite produced via the Griess reaction at the indicated time points in the anaerobic dormancy model.

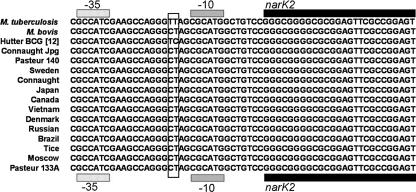

Promoter sequence variation.

We investigated whether the observed differences in expression of narK2/X were attributable to dissimilarities in promoter regions, as has been shown with other mycobacterial nitrate reductases (33). narK2 and narX are adjacent in the genome, with narX beginning where narK2 ends. To examine the promoter, we determined the sequence of 500 bases upstream of narK2 in all of the 13 previously mentioned BCG strains, as well as M. bovis and M. tuberculosis. For all of the strains the entire 500-bp segment was identical with only one exception: at positions −16 and −17 upstream of the start site of narK2 (Fig. 2). This was also true for sequences examined for BCG Pasteur 1173P2, M. bovis, and M. tuberculosis H37Rv obtained from BCGList, BoviList, and TubercuList, respectively. All of the sequences from the 13 BCG strains, as well as M. bovis, have CT at positions −17 and −16, respectively, whereas the M. tuberculosis sequence is TT.

FIG. 2.

Alignment of narK2 promoter region. The sole variable sequence throughout the 500-bp promoter narK2/narX promoter region is shown boxed, with other features labeled. All BCG strains in the present study and M. bovis were identical in promoter region sequence, while the M. tuberculosis sequence and the BCG sequence reported by Hutter and Dick differed (17).

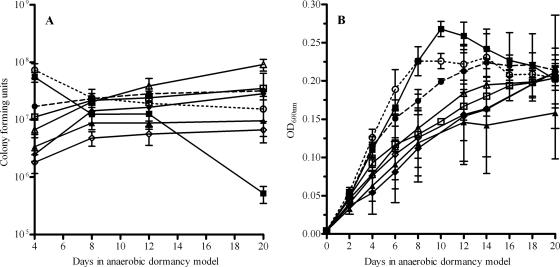

Growth behavior.

To determine whether the transcriptional variation between strains seen by microarray analysis would generate observable phenotypic growth and survival differences, M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and six BCG strains were observed under the anaerobic dormancy conditions (23, 37, 39). The six BCG strains used were selected for further experimentation based on dormancy regulon transcriptional differences, with selected strains containing the most widely divergent profiles. Growth and survival were assayed by two methods: optical density and CFU. A variety of behaviors were observed (Fig. 3).

FIG. 3.

Growth in the anaerobic dormancy model. (A) Sealed tubes were opened at various time points throughout the anaerobic dormancy model and sampled for CFU. (B) The optical density at 600 nm was measured without opening the sealed tubes. M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and BCG Pasteur 140 increased rapidly in optical density and then stabilized or decreased slightly, while the other strains maintained a slow relatively steady increase in optical density throughout the model. Symbols: •, M. tuberculosis; ○, M. bovis; ▪, Pasteur 140; □, Connaught; ⧫, Canada; ⋄, Vietnam; ▴, Russia; ▵, Brazil.

CFU varied between strains and time points (Fig. 3A). Some strains appeared to show a slow decline throughout the model (M. bovis, BCG Pasteur 140), some remained fairly static after day 8 (BCG Vietnam, BCG Canada), and the remainder appeared to slowly maintain growth through day 20. Adaptation to the depleting levels of oxygen was undertaken with various levels of success by the different strains, reflected in the shifts in their CFU at later time points in the model. Within the divergence observed by optical density (Fig. 3B) two general trends occurred: either a steady increase, followed by a drop or stabilization (M. tuberculosis, M. bovis, and BCG Pasteur 140), or a slower overall increase throughout the experiment. Interestingly, the strains that follow the first pattern also reduced nitrate at some level. The changes in optical density of BCG strains during anaerobic dormancy are not solely attributable to bacterial numbers; divergence between the CFU and OD is readily apparent and differs between strains.

DISCUSSION

A variety of transcriptional and phenotypic differences were found among the mycobacterial strains assayed during in vitro induced anaerobic dormancy. It is likely that these differences would also be recapitulated in vivo during conditions in which the dormancy regulon is induced. It is interesting that narK2 and narX were the only dormancy genes not induced by all of the BCG strains, which may be indicative of either a selective advantage provided by their lack of transcription or a lack of selective pressure for their maintenance. Phenotypically, this transcriptional defect would be observed by their inability to reduce nitrate under hypoxic conditions, caused by a lack of nitrate transport via NarK2 (30, 31); however, the function of NarX is unknown (18, 31). With regard to the other transcriptional differences between strains, the functions of many of the genes are currently not known. It is tempting to speculate that defects in dormancy regulon expression may alter the bacterium's ability to survive in the host for long periods of time and thus extend antigen exposure, ultimately affecting the level of protection provided by BCG vaccination. In addition, because the immune response to DosR-controlled antigens has been shown to play a role in the host immune response (21, 28), it is possible that this transcriptional variation could result in immunogenic variability among BCG strains and have a subsequent impact on protective immunity to M. tuberculosis infection. Finally, it is quite possible that experiments performed with different strains of BCG could provide contradictory data as a result of this interstrain variability. This concern has been realized by our observations regarding nitrate reduction which contradict the results previously reported by Hutter and Dick (17).

Throughout the 500-bp upstream region of the narK2/X promoter the sequences are identical in all 13 strains with the exception of one area. These differences are significant because they provide a feasible explanation for the lack of induction of narK2/X by the BCG strains examined in the present study. This conflicts with a report by Hutter and Dick in which they demonstrate the induction of narK2/X by BCG Pasteur ATCC 35734 under hypoxic conditions (17, 18). Hutter and Dick also observed nitrate reduction and narK2 expression that more closely matches that of M. tuberculosis. The bases at positions −17 and −16 upstream of the start site of narK2 are TT in M. tuberculosis and TC in M. bovis and our 13 BCG strains; however, the sequence is CT in the Hutter and Dick BCG strain (17). The −17 and −16 bases are not part of the DosR operator (9, 14, 27) but are within the area of the extended −10 promoter motif, shown to be important in transcription in other bacteria, as well as mycobacteria (5, 24, 35). The Hutter and Dick promoter sequence appears to be an inversion of our BCG promoter sequence from TC to CT. The native M. tuberculosis sequence is TT for these bases; thus, it appears that their BCG promoter has restored the M. tuberculosis T at position −16, which is the preferred base for position −16 of extended −10 motif promoters (24, 35). Since the −17 and −16 bases encompass the only promoter variation among all promoters, it is likely that these bases are responsible for the observed expression differences. Future studies are needed to confirm that the position −16 T is essential for induction from the narK2 promoter.

Improved diagnostic methods for TB would aid in the surveillance and treatment of disease. Routine tests currently utilized have various limitations associated with them (25). Specifically, tests for the identification and differentiation of active and latent TB and the avoidance of confounding results due to cross-reactivity to BCG vaccination or nontuberculous mycobacteria have been lacking (1, 2, 25). Gamma interferon release assays have been evaluated clinically and appear to address many of these issues, and kits are currently commercially available (QuantiFERON-TB or QFT [Cellestis, Ltd.], T-SPOT.TB [Oxford Immunotec]) (12, 25). Although these tests differentiate between BCG vaccination and TB infection, they may underdiagnose latent infection, perhaps because they depend on antigens (ESAT-6 and CFP-10) that may not be highly expressed during latent infection (7, 16). NarX and NarK2 are possible candidates for additional immunodiagnostic antigens. They are not expressed by BCG and are expressed by M. tuberculosis during dormancy; therefore, it seems possible that they could be used to discern latent infection, even in individuals who have been vaccinated with BCG. This possibility is further strengthened by the observation that both antigens have been shown to be immunogenic since they are recognized by the T cells of TB-exposed individuals (M. R. Klein, unpublished studies).

Acknowledgments

This research project was funded by NIH grants RO1AI061505 entitled the Mycobacterium tuberculosis Dormancy Program awarded to M.I.V. and T32AI052066-06 awarded to R.W.H. and U.S. Civilian Research and Development Foundation grant no. 14575 entitled “Molecular Markers of Dormant Mycobacterium tuberculosis.” TB microarrays were provided as part of the NIH NIAID contract number HHSN266200400091C, entitled Tuberculosis Vaccine Testing and Research Materials, awarded to Colorado State University.

Editor: A. J. Bäumler

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 24 March 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abebe, F., C. Holm-Hansen, H. G. Wiker, and G. Bjune. 2007. Progress in serodiagnosis of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection. Scand. J. Immunol. 66176-191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Thoracic Society. 2000. Targeted tuberculin testing and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection. MMWR Recomm. Rep. 491-51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Behr, M. A. 2002. BCG: different strains, different vaccines? Lancet Infect. Dis. 286-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Behr, M. A., M. A. Wilson, W. P. Gill, H. Salamon, G. K. Schoolnik, S. Rane, and P. M. Small. 1999. Comparative genomics of BCG vaccines by whole-genome DNA microarray. Science 2841520-1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks, P. C., L. F. Dawson, L. Rand, and E. O. Davis. 2006. The Mycobacterium-specific gene Rv2719c is DNA damage inducible independently of RecA. J. Bacteriol. 1886034-6038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Castillo-Rodal, A. I., M. Castanon-Arreola, R. Hernandez-Pando, J. J. Calva, E. Sada-Diaz, and Y. Lopez-Vidal. 2006. Mycobacterium bovis BCG substrains confer different levels of protection against Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection in a BALB/c model of progressive pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect. Immun. 741718-1724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cehovin, A., J. M. Cliff, P. C. Hill, R. H. Brookes, and H. M. Dockrell. 2007. Extended culture enhances sensitivity of a gamma interferon assay for latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 14796-798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chenna, R., H. Sugawara, T. Koike, R. Lopez, T. J. Gibson, D. G. Higgins, and J. D. Thompson. 2003. Multiple sequence alignment with the Clustal series of programs. Nucleic Acids Res. 313497-3500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cole, S. T., R. Brosch, J. Parkhill, T. Garnier, C. Churcher, D. Harris, S. V. Gordon, K. Eiglmeier, S. Gas, C. E. Barry III, F. Tekaia, K. Badcock, D. Basham, D. Brown, T. Chillingworth, R. Connor, R. Davies, K. Devlin, T. Feltwell, S. Gentles, N. Hamlin, S. Holroyd, T. Hornsby, K. Jagels, A. Krogh, J. McLean, S. Moule, L. Murphy, K. Oliver, J. Osborne, M. A. Quail, M. A. Rajandream, J. Rogers, S. Rutter, K. Seeger, J. Skelton, R. Squares, S. Squares, J. E. Sulston, K. Taylor, S. Whitehead, and B. G. Barrell. 1998. Deciphering the biology of Mycobacterium tuberculosis from the complete genome sequence. Nature 393537-544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Comstock, G. W. 1988. Identification of an effective vaccine against tuberculosis. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 138479-480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demissie, A., E. M. Leyten, M. Abebe, L. Wassie, A. Aseffa, G. Abate, H. Fletcher, P. Owiafe, P. C. Hill, R. Brookes, G. Rook, A. Zumla, S. M. Arend, M. Klein, T. H. Ottenhoff, P. Andersen, and T. M. Doherty. 2006. Recognition of stage-specific mycobacterial antigens differentiates between acute and latent infections with Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 13179-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dinnes, J., J. Deeks, H. Kunst, A. Gibson, E. Cummins, N. Waugh, F. Drobniewski, and A. Lalvani. 2007. A systematic review of rapid diagnostic tests for the detection of tuberculosis infection. Health Technol. Assess. 111-196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fine, P. E. 1995. Variation in protection by BCG: implications of and for heterologous immunity. Lancet 3461339-1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Florczyk, M. A., L. A. McCue, A. Purkayastha, E. Currenti, M. J. Wolin, and K. A. McDonough. 2003. A family of Acr-coregulated Mycobacterium tuberculosis genes shares a common DNA motif and requires Rv3133c (DosR or DevR) for expression. Infect. Immun. 715332-5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fritz, C., S. Maass, A. Kreft, and F. C. Bange. 2002. Dependence of Mycobacterium bovis BCG on anaerobic nitrate reductase for persistence is tissue specific. Infect. Immun. 70286-291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hill, P. C., R. H. Brookes, A. Fox, D. Jackson-Sillah, D. J. Jeffries, M. D. Lugos, S. A. Donkor, I. M. Adetifa, B. C. de Jong, A. M. Aiken, R. A. Adegbola, and K. P. McAdam. 2007. Longitudinal assessment of an ELISPOT test for Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. PLoS Med. 4e192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hutter, B., and T. Dick. 2000. Analysis of the dormancy-inducible narK2 promoter in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 188141-146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hutter, B., and T. Dick. 1999. Up-regulation of narX, encoding a putative “fused nitrate reductase” in anaerobic dormant Mycobacterium bovis BCG. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 17863-69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kalendar, R. 2006. FastPCR, PCR primer design, DNA and protein tools, repeats and own database searches program. University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. http://www.biocenter.helsinki.fi/bi/programs/fastpcr.htm.

- 20.Kumar, A., J. C. Toledo, R. P. Patel, J. R. Lancaster, Jr., and A. J. Steyn. 2007. Mycobacterium tuberculosis DosS is a redox sensor and DosT is a hypoxia sensor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10411568-11573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leyten, E. M., M. Y. Lin, K. L. Franken, A. H. Friggen, C. Prins, K. E. van Meijgaarden, M. I. Voskuil, K. Weldingh, P. Andersen, G. K. Schoolnik, S. M. Arend, T. H. Ottenhoff, and M. R. Klein. 2006. Human T-cell responses to 25 novel antigens encoded by genes of the dormancy regulon of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 82052-2060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liberek, A., M. Korzon, E. Bernatowska, M. Kurenko-Deptuch, and M. Rytlewska. 2006. Vaccination-related Mycobacterium bovis BCG infection. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 12860-862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, A., M. Eleuterio, B. Hutter, B. Murugasu-Oei, and T. Dick. 1999. Oxygen depletion-induced dormancy in Mycobacterium bovis BCG. J. Bacteriol. 1812252-2256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mitchell, J. E., D. Zheng, S. J. Busby, and S. D. Minchin. 2003. Identification and analysis of “extended −10” promoters in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 314689-4695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pai, M., S. Kalantri, and K. Dheda. 2006. New tools and emerging technologies for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. I. Latent tuberculosis. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 6413-422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Parish, T., and N. G. Stoker. 2001. Mycobacterium tuberculosis protocols. Humana Press, Totowa, NJ.

- 27.Park, H. D., K. M. Guinn, M. I. Harrell, R. Liao, M. I. Voskuil, M. Tompa, G. K. Schoolnik, and D. R. Sherman. 2003. Rv3133c/DosR is a transcription factor that mediates the hypoxic response of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Mol. Microbiol. 48833-843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Roupie, V., M. Romano, L. Zhang, H. Korf, M. Y. Lin, K. L. Franken, T. H. Ottenhoff, M. R. Klein, and K. Huygen. 2007. Immunogenicity of eight dormancy regulon-encoded proteins of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in DNA-vaccinated and tuberculosis-infected mice. Infect. Immun. 75941-949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sherman, D. R., M. Voskuil, D. Schnappinger, R. Liao, M. I. Harrell, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2001. Regulation of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis hypoxic response gene encoding alpha-crystallin. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 987534-7539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sohaskey, C. D. 2005. Regulation of nitrate reductase activity in Mycobacterium tuberculosis by oxygen and nitric oxide. Microbiology 1513803-3810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sohaskey, C. D., and L. G. Wayne. 2003. Role of narK2X and narGHJI in hypoxic upregulation of nitrate reduction by Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Bacteriol. 1857247-7256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stermann, M., A. Bohrssen, C. Diephaus, S. Maass, and F. C. Bange. 2003. Polymorphic nucleotide within the promoter of nitrate reductase (NarGHJI) is specific for Mycobacterium tuberculosis. J. Clin. Microbiol. 413252-3259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Stermann, M., L. Sedlacek, S. Maass, and F. C. Bange. 2004. A promoter mutation causes differential nitrate reductase activity of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium bovis. J. Bacteriol. 1862856-2861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virtanen, S. 1960. A study of nitrate reduction by mycobacteria. The use of the nitrate reduction test in the identification of mycobacteria. Acta Tuberc. Scand. Suppl. 481-119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Voskuil, M. I., and G. H. Chambliss. 1998. The −16 region of Bacillus subtilis and other gram-positive bacterial promoters. Nucleic Acids Res. 263584-3590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Voskuil, M. I., D. Schnappinger, K. C. Visconti, M. I. Harrell, G. M. Dolganov, D. R. Sherman, and G. K. Schoolnik. 2003. Inhibition of respiration by nitric oxide induces a Mycobacterium tuberculosis dormancy program. J. Exp. Med. 198705-713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wayne, L. G. 2001. In vitro model of hypoxically induced nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Methods Mol. Med. 54247-269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wayne, L. G., and J. R. Doubek. 1965. Classification and identification of mycobacteria. Ii. Tests employing nitrate and nitrite as substrate. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 91738-745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wayne, L. G., and L. G. Hayes. 1996. An in vitro model for sequential study of shiftdown of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through two stages of nonreplicating persistence. Infect. Immun. 642062-2069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wayne, L. G., and L. G. Hayes. 1998. Nitrate reduction as a marker for hypoxic shiftdown of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Tuber Lung Dis. 79127-132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber, I., C. Fritz, S. Ruttkowski, A. Kreft, and F. C. Bange. 2000. Anaerobic nitrate reductase (NarGHJI) activity of Mycobacterium bovis BCG in vitro and its contribution to virulence in immunodeficient mice. Mol. Microbiol. 351017-1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.World Health Organization. 2007. Tuberculosis fact sheet number 104, revised March 2007. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs104/en/.