Abstract

Neisseria gonorrhoeae expressing type IV pili (Tfp) activates extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and induces a cytoprotective state in the epithelial cell in a manner that is enhanced by pilT. As the ERK signaling pathway is well-known for its role in cytoprotection and cell survival, we tested the hypothesis that ERK is involved in producing this cytoprotective effect. Inhibiting ERK activation prior to infection attenuated the ability of these bacteria to induce cytoprotection. Activated ERK specifically targeted two proapoptotic Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only proteins, Bim and Bad, for downregulation at the protein level. Bim downregulation occurred through the proteasome. ERK, in addition, inactivated Bad by triggering its phosphorylation at Ser112. Finally, reducing the level of either Bad or Bim alone by small interfering RNA was sufficient to protect uninfected cells from staurosporine-induced apoptosis. We conclude that Tfp-induced cytoprotection is due in part to ERK-dependent modification and/or downregulation of proapoptotic proteins Bad and Bim.

Neisseria gonorrhoeae causes gonorrhea, the second most reported sexually transmitted disease in the United States (http://www.cdc.gov/std/stats). The bacterium often initiates infection at mucosal surfaces of the urogenital tract, and these infections can lead to serious complications if left untreated. While gonorrhea is typically regarded as a disease with clear symptoms in men, it has long been recognized that infection in women is often asymptomatic. When clinical symptoms do appear in either sex, they usually occur days or even weeks following exposure. Moreover, greater than 5% of the population between the ages of 18 and 35 are asymptomatically colonized with N. gonorrhoeae (36). These observations imply that gonorrheal disease may be accidental and that the infecting organisms intend minimal harm to the human host.

Consistent with this view, infection of cultured epithelial cells with N. gonorrhoeae does not induce cell damage (3, 4, 13, 26). Cells infected with N. gonorrhoeae expressing type IV pili (Tfp) and Opa (opacity protein) are better able to withstand apoptosis-inducing stimuli than uninfected cells are (4, 26). The gonococcal porin has been shown to partially protect cells from staurosporine (STS)-induced apoptosis (3). Tfp and pilT, the gene encoding the Tfp retraction motor, are also involved in cytoprotection. Apoptosis signaling and apoptotic cell death are significantly lower in cells infected with piliated, non-Opa-expressing N. gonorrhoeae than in cells infected with a pilT mutant that adheres to cells but expresses nonretractible Tfp (39). Moreover, piliated, non-Opa-expressing N. gonorrhoeae is better able to protect cells from STS-induced apoptosis than its pilT derivative is (13). The cytoprotective effects related to Tfp/pilT may be due to at least two mechanisms that are not mutually exclusive. Tfp retraction may indirectly promote cytoprotection by bringing the porin-containing bacterial membrane in close proximity to the epithelial cell membrane. As physical force is known to induce cytoprotective signaling in eukaryotic cells (8, 37), it is possible that the force of Tfp retraction (22, 25) may induce cytoprotection by activating stress-responsive prosurvival signaling pathways.

Piliated, non-Opa-expressing N. gonorrhoeae has been shown to activate two stress-responsive, prosurvival signaling pathways in epithelial cells, the phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3-K)/Akt pathway (18) and the extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) pathway (13). A functional pilT enhances PI3-K and ERK activation. The kinetics of infection-induced ERK activation, i.e., rapid and sustained phosphorylation (13), is a characteristic of ERK activation that leads to cytoprotective signaling (11, 29, 35).

ERK triggers prosurvival signaling through multiple mechanisms, including transcriptional regulation and phosphorylation of pro- or antiapoptotic proteins (2). Some of the best-studied substrates of activated ERK are members of the Bcl-2 homology domain 3 (BH3)-only family of proapoptotic proteins, including Bad and Bim (42). BH3-only proteins function as cellular sensors of survival signals. When survival signals (such as activated ERK) are present, the BH3-only proteins are inactive. When they are absent, BH3-only proteins become activated, and they antagonize the function of prosurvival Bcl-2-like proteins (31). This leads to mitochondrial membrane permeabilization, cytochrome c release, and cell death. The relative levels and activation states of BH3-only proteins thus serve as a cellular “teeter-totter'’ that helps to control apoptosis signaling.

In view of the prosurvival signaling properties of ERK, we tested the hypothesis that ERK activation by piliated, non-Opa-expressing N. gonorrhoeae contributes to cytoprotection. Inhibiting ERK activation attenuated the ability of these bacteria to induce cytoprotection. ERK downregulated the proapoptotic BH3-only proteins Bim and Bad. ERK downregulated Bim through the proteasome and additionally inactivated Bad through phosphorylation. Finally, small interfering RNA (siRNA) downregulation of either Bad or Bim alone was sufficient to protect cells from STS-induced apoptosis. Our results reveal a new pathway by which N. gonorrhoeae promotes cytoprotection in the epithelial cell.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Antibodies to poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP), cleaved PARP, caspase 8, P38 mitogen-activated protein kinase, Bad, phospho-Bad (Ser112, Ser136, and Ser155), Bim, Bid, Bmf, and Bok were purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies. siRNA specific for Bim and Bad were purchased from Dharmacon RNA Technologies (Chicago, IL). MEK inhibitor U0126 and proteasome inhibitor MG132 were purchased from Calbiochem and used at a final concentration of 10 μM unless otherwise stated. STS was purchased from Cell Signaling Technologies and used at a final concentration of 1 μM. U0126, MG132, and STS were diluted in dimethyl sulfoxide.

Cell lines, bacterial strains, and infections.

T84 human colonic epidermoid cells (American Type Culture Collection) (a cell type that is susceptible to gonococcal infection in vivo) were maintained in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing Ham's F12 nutrient mixture plus 5% heat-inactivated, filter-sterilized fetal bovine serum at 37°C and 5% CO2. For all experiments, cells were seeded into tissue culture dishes and allowed to become confluent prior to infection. N. gonorrhoeae strains N400 and N400pilT (39) were used for infections. Both strains express Tfp but not Opa, and both adhere to human epithelial cells (24). Bacteria were maintained on gonococcal medium base (GCB) agar plus Kellogg's supplements at 37°C and 5% CO2. Piliation and Opa phenotypes were monitored by light microscopy of colony morphology. Only piliated, non-OpaA-expressing bacteria were used. For infection experiments, bacteria were swabbed from 16-hour GCB agar, resuspended in GCB liquid medium, and added to epithelial cells at a multiplicity of infection of 50.

Immunoblotting.

T84 cells were infected with N. gonorrhoeae N400 or N400pilT or treated with medium alone for specified times. Following infection, cells were lysed with 150 μl of 1× sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS) lysis buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl [pH 6.8], 2% [wt/vol] SDS, 10% glycerol, 50 mM dithiothreitol, 0.1% [wt/vol] bromophenol blue), scraped into Eppendorf tubes, vortexed for 15 seconds, and immediately stored at −20°C. For cleaved PARP and caspase 8 assays, each culture was incubated with 150 μl cell lysis buffer (20 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, 0.5% NP-40, 2.5 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM β-glycerolphosphate, 1 mM Na3VO4, 1 μg/ml leupeptin) for 20 min on ice and then sonicated for 15 seconds. Samples were boiled for 5 min at 100°C. Equal volumes of the same sample were loaded on several SDS-polyacrylamide gels and electrophoresed simultaneously. Proteins were transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes, and each filter was probed with the appropriate antibody according to the manufacturer's instruction. Separate gels were run and immunoblotted for cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase 8, phosphorylated ERK, and P38. The similar sizes of these proteins and the cross-reactivity of some antibodies precluded immunoblotting the same filter with multiple antibodies, and stripping and reprobing the same membrane multiple times removed proteins and/or resulted in unacceptable background noise.

RNA isolation.

Following infection, the culture medium was aspirated and replaced with buffer RLT (plus β-mercaptoethanol) from the RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc.). Cells were scraped off the plate and transferred to Qiashredder columns (Qiagen, Inc.) to homogenize the sample. Samples were then stored at −80°C until further processing. After all the samples had been frozen, total RNA was isolated using the Qiagen RNeasy kit (Qiagen, Inc.).

Real-time reverse transcription-PCR analysis.

One microgram of total RNA (as isolated above) was reverse transcribed to generate cDNA, using the iScript cDNA synthesis kit (Bio-Rad). As a negative control, parallel samples were run without reverse transcriptase. Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ABI PRISM 7000 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems). Amplification was carried out using TaqMan master mix and predesigned TaqMan probes (glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase, Hs99999905_m1; Bim, Hs00197982_m1; Bad, Hs00188930_m1) according to the manufacturer's instructions (Assays-on-Demand; Applied Biosystems). Reactions were performed in triplicate in a 20-μl volume, with the following cycle parameters: enzyme activation (10 min at 95°C), followed by 40 cycles of 15 seconds at 95°C and 1 min at 60°C. Data analysis was performed using the comparative threshold cycle method (Applied Biosystems) to determine relative expression levels.

Gene silencing using siRNA.

siRNAs were introduced into T84 cells using nucleofection, according to the manufacturer's instructions (Amaxa). Briefly, cells were grown to confluence in tissue culture flasks, then trypsinized, and counted using a hemocytometer. For each nucleofection, 1 × 106 cells were aliquoted into Eppendorf tubes and centrifuged at 1,500 rpm for 2 min. Residual medium was aspirated, and cells were resuspended in 100 μl of nucleofector reagent R. The appropriate amount of siRNA was then added, and the cell mixture was transferred to an electroporation cuvette. Cells were nucleofected using program T-16, then transferred to 1 ml Dulbecco modified Eagle medium containing Ham's F12 nutrient mixture plus 5% heat-inactivated, filter-sterilized fetal bovine serum and seeded into one well of a 12-well plate. Cells were assayed 24 or 72 h postnucleofection.

Statistics.

Statistical analysis was performed using standard t test analysis with the statistics program SPSS version 11.0 unless stated otherwise.

RESULTS

Tfp-mediated ERK activation is cytoprotective.

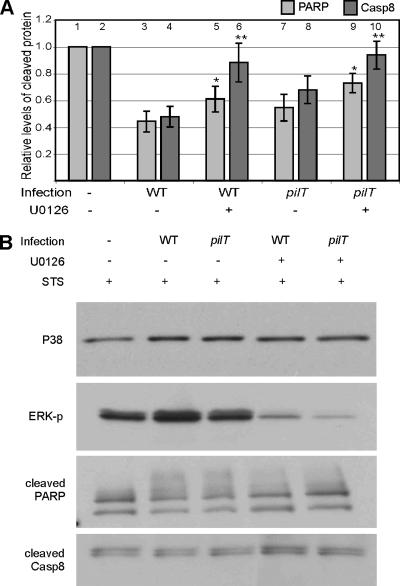

We tested the hypothesis that N. gonorrhoeae-induced ERK activation contributes to cytoprotection. T84 human colorectal epithelial cells (a cell type that is susceptible to gonococcal infection in vivo) were treated with ERK activation inhibitor U0126 or vehicle and then infected for 4 h with wild-type (WT) N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 or mutant strain N400pilT. Both strains express Tfp but not Opa. The latter does not retract Tfp due to a mutation in pilT, the gene encoding the retraction motor. Cells were then treated with STS for an additional 4 h to induce apoptosis. Cell lysates were immunoblotted with antibodies to cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8 to assess the level of apoptosis (Fig. 1). PARP and caspase 8 are cleaved at the terminal stages of apoptosis. A higher level of cleaved protein is directly correlated with increased apoptosis in the culture (16).

FIG. 1.

Effect of ERK inhibition on infection-mediated cytoprotection. T84 cells were preincubated with U0126 or vehicle alone and then infected with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 (WT) or N400pilT (pilT) or left uninfected (−) for 4 h, followed by incubation with STS (1 μM) for an additional 4 h to induce apoptosis. Lysates were immunoblotted for cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8 as well as phosphorylated ERK (U0126 control) and P38 (input control), as described in Materials and Methods. Cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8 signals were quantified by densitometry and normalized to the signal from uninfected, untreated cells. The results averaged from four independent experiments are shown in panel A. Values for cleaved PARP (light gray bars) or cleaved caspase 8 (Casp8) (dark gray bars) represent the mean levels of cleaved protein ± standard errors of the means (error bars). For the effect of U0126 on cleaved PARP, compare bar 3 with bar 5 and bar 7 with bar 9. For the effect of U0126 on cleaved caspase 8, compare bar 4 with bar 6 and bar 8 with bar 10. An asterisk above a bar indicates that the statistical difference between the sample value and its non-U0126-treated control value has a P value of <0.1, and two asterisks above a bar indicates that the statistical difference between the sample value and its non-U0126-treated control value has a P value of <0.05. A representative set of immunoblots from one such experiment is shown in panel B. ERK-p, phosphorylated ERK.

As observed previously (13), cells infected with WT strain N400 or N400pilT had reduced levels of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8 than uninfected cells did. WT N400-infected cells had lower levels of these proteins than pilT-infected cells did (Fig. 1A, compare bar 3 to bar 7 and bar 4 to bar 8, respectively). Importantly, inhibiting ERK activation with U0126 prior to infection with WT strain N400 or N400pilT resulted in higher levels of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase 8 compared to those of the appropriate control cultures not exposed to inhibitor. Thus, preventing ERK activation lowered the cytoprotective effect of Tfp-mediated infection. Interestingly, U0126 almost completely reversed the attenuation of caspase 8 cleavage (Fig. 1A, compare bar 4 to bar 6 and bar 8 to bar 10). This suggests that ERK activation is mainly responsible for attenuating caspase 8 cleavage and that ERK and non-ERK pathways work to attenuate PARP cleavage.

ERK modifies Bad in a pilT-dependent manner.

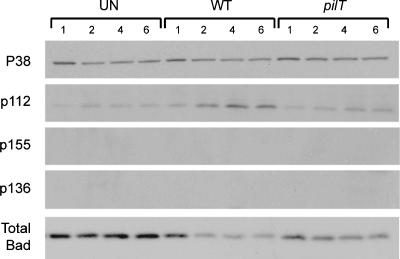

ERK is one of at least three signaling pathways that converge to phosphorylate and inactivate the proapoptotic protein Bad. ERK and protein kinase A (PKA) induce phosphorylation of Bad at Ser112 and/or Ser155, and PI3-K induces Bad phosphorylation at Ser136 (31). We examined Bad phosphorylation at each of these sites in cells infected with WT N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 and N400pilT (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Phosphorylated Bad and total Bad levels in infected T84 cells. Representative immunoblot showing levels of total Bad and Bad phosphorylated at Ser112 (p112), Ser136 (p136), and Ser155 (p155) in uninfected T84 cells (UN) and T84 cells infected with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 (WT) or N400pilT (pilT) for 1, 2, 4, and 6 h. The total P38 protein level in each sample served as the internal control. Four independent experiments were performed with similar results.

N. gonorrhoeae N400-infected cells had a noticeably higher level of Bad phospho-Ser112 than uninfected cells did. By 4 h postinfection, Bad phospho-Ser112 had reached maximum levels. In contrast, N. gonorrhoeae N400pilT-infected cells had a noticeably lower level of Bad phospho-Ser112. Bad phosphorylated at Ser155 was not detected in any of our samples. Thus, the bacteria induced Bad phosphorylation specifically at Ser112, and this activity was enhanced by a functional pilT gene. Inhibiting ERK activation with U0126 prior to infection partially blocked Bad phosphorylation at Ser112 (see Fig. 4A and C), indicating the involvement of ERK in this process. The involvement of PKA in the phosphorylation of Ser112 cannot be inferred from this data. Finally, Ser136 phosphorylation was not detected, strongly suggesting that Bad phosphorylation in our infected cells does not involve the PI3-K pathway.

FIG. 4.

Inhibition of Bad and Bim degradation and Bad phosphorylation by ERK and proteasome inhibitors. (A) Representative immunoblot showing levels of total Bim, total Bad, and phosphorylated Bad (Bad-p) (phosphorylated on Ser112) in uninfected T84 cells (−) and T84 cells infected with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 (WT) or N400pilT (pilT) for 6 h in the presence (+) or absence (−) of ERK inhibitor U0126. ERK-p, phosphorylated ERK. (B) Representative immunoblot showing total Bad and Bim levels in uninfected T84 cells and T84 cells infected with N400 (WT) or N400pilT (pilT) for 6 h in the presence (+) or absence (−) of proteasome inhibitor MG132. In both panels A and B, the total P38 protein levels in each sample served as the internal control. (C) Phosphorylated Bad (Bad-p) levels averaged from panel A and two other independent experiments as determined by densitometry of immunoblot signals. (D) Total Bim levels after U0126 or MG132 treatment averaged from panel A or B and two other independent experiments as determined by densitometry of immunoblot signals. (E) Total Bad levels after U0126 or MG132 treatment, averaged from panel A or B and two other independent experiments as determined by densitometry of immunoblot signals. In panels C, D, and E, the densitometric signal in each sample was normalized to the internal P38 signal and expressed relative to the normalized value from the uninfected cell sample. The latter, set arbitrarily at 1.0, is represented by the broken line. Values are mean normalized protein levels ± standard errors of the means (error bars). An asterisk above a bar indicates statistical differences between the values for untreated cells and inhibitor-treated cells with a P value of <0.05, and two asterisks above a bar indicates statistical differences between the values for untreated and inhibitor-treated cells with a P value of <0.01.

Infection with WT N400 also led to decreased levels of total Bad protein (Fig. 2). Maximal protein downregulation occurred by 2 h postinfection, and total Bad levels remained low throughout the 6-hour time course (longer time periods were not tested). As with Ser112 phosphorylation, N400 was more effective than N400pilT in downregulating total Bad.

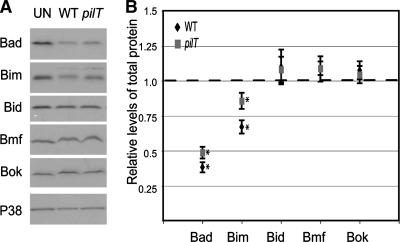

Infection targets Bad and Bim for protein downregulation.

Chlamydia infection leads to a broad degradation of epithelial cell BH3-only proteins, including Bad (30, 41). We therefore determined whether N. gonorrhoeae also downregulates other BH3-only proteins. Lysates from T84 cells infected for 6 h with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 or N400pilT were immunoblotted for pro- and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 family proteins, including those in the BH3-only family. Infected and uninfected cells had identical levels of Bid, Bmf, and Bok (Fig. 3A and B), as well as Bcl-2 Bax and Bak (data not shown). Only Bad and Bim levels were lower in infected cells than in uninfected cells. Bad and Bim levels were slightly but significantly lower in N400-infected cells than N400pilT-infected cells (P < 0.05 for Bad; P < 0.0005 for Bim), indicating that this downregulation was partly pilT dependent. Thus, N. gonorrhoeae, unlike Chlamydia, specifically targets two BH3-only proteins, Bad and Bim, for downregulation.

FIG. 3.

Levels of BH3-only proteins in infected and uninfected cells. (A) Representative immunoblot showing levels of selected BH3-only proteins (Bad, Bim, Bid, Bmf, and Bok) in uninfected T84 cells (UN) or T84 cells infected with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 (WT) or N400pilT (pilT) for 6 h. The total P38 protein levels in each sample served as the internal control. (B) Relative levels of the BH3-only proteins shown in panel A. Each signal was quantitated by densitometry, normalized to its internal P38 signal, and expressed relative to the normalized value from uninfected cells (represented as broken line). Values are mean normalized protein levels averaged from at least three independent experiments ± standard errors of the means (error bars). Differences between infected and uninfected signals with a P value of <0.05 (asterisk) are shown.

Downregulation of Bad and Bim is mediated by ERK and proteasomal activity.

ERK downregulation of Bim has been shown to occur at the level of transcription in a number of other experimental systems (31, 38). Therefore, we determined whether Neisseria-induced Bad and Bim downregulation occurred at the mRNA level. T84 cells were infected with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 or N400pilT for 2 or 6 h, and mRNA was isolated and used as template for real-time reverse transcription-PCR. Bad and Bim transcript levels were nearly identical in uninfected cells and cells infected with strain N400 or N400pilT at both time points (Table 1). Thus, Bad and Bim downregulation does not occur at the level of mRNA.

TABLE 1.

Bim and Bad mRNA levels following infection with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 or N400pilT

| mRNA | Time point (hpi)a | mRNA level after infection with strainb:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| WT | pilT | ||

| Bad | 2 | −1.05 ± 0.071 | −1.1 ± 0.000 |

| 6 | −1.15 ± 0.071 | −1.3 ± 0.000 | |

| Bim | 2 | 1.15 ± 0.071 | 1.0 ± 0.141 |

| 6 | −1.10 ± 0.141 | 1.0 ± 0.000 | |

hpi, hours postinfection.

Relative levels of Bim and Bad mRNA in N400 (WT)- and N400pilT (pilT)-infected cells compared to those in uninfected cells. Values are the mean fold changes in mRNA levels between infected and uninfected cells ± standard errors of the means from at least two independent experiments.

Next, we assessed ERK downregulation of Bad and Bim at the protein level. Both proteins are targets of activated ERK, and Bim degradation has been shown to be mediated by this pathway (38). T84 cells were preincubated with ERK inhibitor U0126 for 1 h, followed by a 6-hour infection with strain N400 or N400pilT. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted to determine the relative levels of Bad and Bim. A representative immunoblot is shown in Fig. 4A. Inhibiting ERK activation with U0126 reversed infection-induced downregulation of Bim and Bad (Fig. 4A). Densitometric analysis of immunoblot signals from Fig. 4A and two other independent experiments further illustrates the effect of U0126 on preventing Bad and Bim downregulation (Fig. 4D and E). Thus, both Bad and Bim proteins are downregulated in an ERK-dependent manner.

ERK-mediated degradation of Bim is known to proceed via the proteasomal pathway (38). We therefore determined whether the proteasome is involved in N. gonorrhoeae-mediated downregulation of Bad or Bim. T84 cells were preincubated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 for 1 h, followed by a 6-hour infection with N. gonorrhoeae strain N400 or N400pilT. Total cell lysates were immunoblotted to determine the relative levels of Bad and Bim. A representative immunoblot is shown in Fig. 4B. MG132 completely reversed Bim downregulation by both strains, restoring the protein to uninfected cell levels. Densitometric analysis of immunoblot signals from Fig. 4B and two other independent experiments further illustrates the effect of MG132 on Bim downregulation (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that N. gonorrhoeae-induced downregulation of Bim involves the proteasome. They are consistent with reports on the involvement of the proteasome in Bim degradation in noninfection situations (38). Surprisingly, MG132 enhanced rather than inhibited Bad downregulation (Fig. 4E). Bad downregulation through degradation has not been reported previously, to our knowledge. MG132 may have a nonspecific, pleiotropic effect on Bad, or it may indirectly downregulate Bad by affecting a pathway that controls Bad cellular levels. Further work will be necessary to determine the effect of MG132 on Bad.

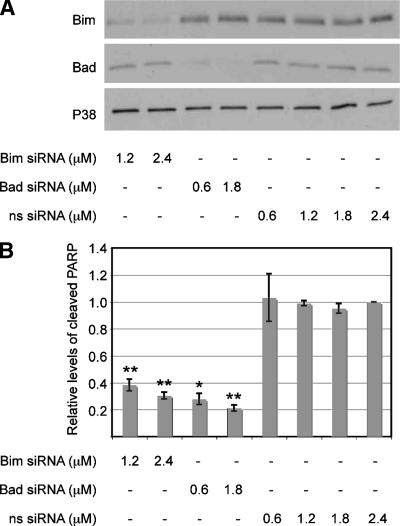

Decreased levels of Bad or Bim are sufficient for cytoprotection.

We determined whether reducing Bad and Bim levels in the absence of bacterial infection would be sufficient to protect cells from apoptosis. T84 cells were transfected with siRNA directed against Bad or Bim or with a nonsense siRNA. To monitor the inhibitory efficiency of the siRNAs, cell lysates were immunoblotted for total Bad and Bim levels 72 h posttransfection. Cells treated with two different concentrations of the cognate siRNA had markedly lower levels of Bim or Bad, with the level of each protein being reduced between 55 and 75% (Fig. 5A). Importantly, nonspecific siRNA had no effect on Bim or Bad levels, and siRNA targeted against Bad had no effect on Bim levels and vice versa.

FIG. 5.

Protection against STS-induced apoptosis through siRNA downregulation of Bad and Bim. (A) Representative immunoblot showing total Bad and Bim protein levels in uninfected T84 cells 72 h after transfection with various concentrations of Bim- or Bad-specific siRNA or nonspecific (ns) siRNA. The total P38 protein levels in each sample served as the internal control. (B) Levels of cleaved PARP in uninfected T84 cells transfected with various concentrations of Bim- or Bad-specific siRNA or nonspecific (ns) siRNA for 72 h, followed by incubation with 1 mM STS for 4 h to induce apoptosis. Cleaved PARP levels were determined by immunoblotting, and the signals were quantified by densitometry. Values represent the mean levels of cleaved PARP ± standard errors of the means (error bars) from three independent experiments. Two asterisks above a bar indicates that the statistical difference between the value for the sample and the value for the nonspecific siRNA-treated control has a P value of <0.005, and one asterisk indicates that the statistical difference between the value for the sample and the value for the nonspecific siRNA-treated control has a P value of <0.05.

Finally, we determined whether cells downregulated for Bad and/or Bim by siRNA are protected against STS-induced apoptosis. T84 cells were transfected with various concentrations of Bad or Bim or nonsense siRNA. Seventy-two hours posttransfection, cultures were treated with STS for 4 h and then immunoblotted for cleaved PARP. As expected, nonsense siRNA did not afford cytoprotection (Fig. 5B). In contrast, cells transfected with either Bad or Bim siRNA had significantly lower levels of cleaved PARP. This response was dose dependent, with higher concentrations of the cognate siRNA providing a higher level of cytoprotection. Thus, reducing the levels of total cellular Bad or Bim protein is sufficient to attenuate apoptosis signaling. These experimental results strongly suggest that infection-induced Bad and Bim downregulation contributes to the observed cytoprotection.

DISCUSSION

Activated ERK is well-known for its role in cytoprotection and cell survival (11, 29, 35). Piliated, non-Opa-expressing N. gonorrhoeae activates ERK in a manner that is enhanced by pilT, and it induces a cytoprotective state in epithelial cells (12, 13). We tested the hypothesis that ERK activation is involved in Tfp-mediated cytoprotection. Here we demonstrate that inhibiting ERK activation with U0126 attenuates the ability of the bacteria to protect epithelial cells from STS-induced apoptosis (Fig. 1). ERK inhibition does not completely abolish cytoprotection, suggesting that ERK-independent pathways are also involved. Nevertheless, our results show that ERK plays a role in the process.

In accordance with its function as a prosurvival signaling intermediate, activated ERK influences the level and activity of numerous proteins that regulate apoptosis. We focused on pathways that are rapidly modified by activated ERK (11, 29, 35). We found that activated ERK leads to Bad phosphorylation at Ser112 as well as Bad and Bim protein downregulation (Fig. 2).

Bad activity is thought to be controlled primarily by phosphorylation. Phosphorylated Bad is sequestered in the cytoplasm, where it is unable to interact with and abrogate the function of antiapoptotic proteins on the mitochondrial membrane. Bad degradation, on the other hand, is likely to affect apoptosis by reducing the amount of total Bad protein available for trafficking to the mitochondria to stimulate apoptosis. The relative contributions of Bad phosphorylation and Bad degradation to Neisseria-induced cytoprotection are unclear. Since the two mechanisms affect Bad function at two different points, they may act synergistically to prevent apoptosis. The siRNA results suggest that the general process of Bad downregulation plays a significant role in Bad-related cytoprotection. The induction of Bad degradation by Chlamydia and N. gonorrhoeae thus appears to be a novel mechanism for Bad regulation. Chlamydia-induced Bad degradation occurs very slowly, taking approximately 24 h, and is the result of cleavage of all BH3 proteins by a chlamydial protease (30, 41). In contrast, Neisseria specifically targets Bad and Bim for downregulation (Fig. 3). Bad downregulation occurs rapidly; protein levels reach a minimum by 2 h postinfection and remain depressed throughout the 6-hour time course. Neisseria-induced downregulation of Bad and Bim requires ERK activation and, at least in the case of Bim, proteasome activity (Fig. 4).

Bim degradation protects cells from apoptosis induced by UV, paclitaxel, glucocorticoids, and other stimuli (1, 5, 9, 10, 17, 20, 21, 23, 34). Bad downregulation has a similar antiapoptotic effect (15, 32, 40). What might be the advantage to Neisseria in downregulating both Bim and Bad as a cytoprotective strategy? First, different BH3-only proteins act as sentinels for different apoptotic stimuli. Bad is sensitive to growth factors and changes in basal activity of ERK, PI3-K, or PKA. Bim is sensitive to cytokine withdrawal, calcium flux, and microtubule-destabilizing agents (7). Downregulating both Bad and Bim may therefore protect against a larger set of apoptotic stimuli than downregulating either protein alone. Second, Bim and Bad belong to two distinct functional classes of BH3-only proteins (19). Bim is classified as an activator BH3-only protein; it is capable of directly binding and activating Bax and Bak, leading to mitochondrial pore formation and cytochrome c release. Conversely, Bad is a sensitizer BH3-only protein that does not directly stimulate apoptosis. Rather, it sensitizes the cell to apoptotic stimuli by neutralizing Bcl-2 like antiapoptotic proteins. By downregulating both Bad and Bim, N. gonorrhoeae attenuates two distinct mechanisms of apoptosis signaling.

What other prosurvival signaling pathways might come into play in Tfp/pilT-mediated cytoprotection? ERK activation is involved in a number of other cytoprotective events, including the regulation of the inhibitor of apoptosis proteins and gene expression (6, 14). The PI3-K pathway, like ERK, is activated by Neisseria in a pilT-enhanced manner (18). This pathway (i) controls the regulation of the Forkhead family (FKHR, FKHRL1, and AFX), IK-B kinase, mdm-2, CREB, inhibitor of apoptosis proteins, and YAP via phosphorylation; (ii) regulates Flice-inhibitory protein (FLIP) gene expression, which in turn prevents death receptor signaling via caspase 8; and (iii) mediates the metabolic regulation of cell survival through inhibition of glycogen synthase kinase 3 (33).

Gonococcal components other than Tfp/pilT also affect the apoptotic state of the cell. Membranes from N. gonorrhoeae expressing Tfp but not Opa reduce STS-induced apoptosis in the absence of intact bacteria (13), implicating a non-pilT, non-Opa mechanism (13). In a separate study, N. gonorrhoeae expressing Tfp and Opa also lower STS-induced apoptosis (4). It is unclear whether the two studies are describing the same component. Porin has been demonstrated to prevent (3, 4, 26) as well as stimulate (27, 28) apoptosis. All these studies involved different bacterial strains, eukaryotic cell types, and infection protocols. While some of these results appear contradictory, they may in fact reflect the complex nature of a cellular response to stress. The outcome of stress on a cell is influenced by the nature and strength of the signal, the relative strength of the many intersecting stress response pathways, and the cell type involved. The bacterial signal may derive from a complex interplay of multiple gonococcal components, such as the scenarios described in the introduction. More work will be required to determine whether there is interplay between pilT-dependent and -independent factors in promoting cytoprotection. The contradictory results may also reflect the diverse nature of gonococcal infections. Given the numerous environments that N. gonorrhoeae can be exposed to and the ability of the bacterium to vary its surface components, many of these cytoprotective mechanisms are likely to function, either separately or in concert.

What advantage might cytoprotection confer on N. gonorrhoeae? Reducing apoptosis in the host cell could delay or prevent the onset of the immune response, which in turn could enhance bacterial colonization and subsequent dissemination. It may promote the establishment of the carrier state and/or intracellular survival. Cytoprotection also has the potential of reducing cytokine-mediated damage of the epithelium. All this is likely to be evolutionarily advantageous to a sexually transmitted organism that is exquisitely adapted to humans. The low virulence of the organism and the ability of the bacterium to establish a carrier state are consistent with the notion that N. gonorrhoeae intends minimum harm to its host.

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Kaplan and members of the So lab, N. Weyand, D. Higashi, K. Kanack, and C. Calton for their thoughtful comments on the manuscript and D. Higashi for help in manuscript preparation.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant RO1-AI049973 awarded to M.S. and National Institutes of Health grants T32-AI07472 and F32 AI063875-02 awarded to H.L.H. and S.L.S., respectively.

Editor: J. N. Weiser

Footnotes

Published ahead of print on 7 April 2008.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abrams, M. T., N. M. Robertson, K. Yoon, and E. Wickstrom. 2004. Inhibition of glucocorticoid-induced apoptosis by targeting the major splice variants of BIM mRNA with small interfering RNA and short hairpin RNA. J. Biol. Chem. 27955809-55817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ballif, B. A., and J. Blenis. 2001. Molecular mechanisms mediating mammalian mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) kinase (MEK)-MAPK cell survival signals. Cell Growth Differ. 12397-408. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Binnicker, M. J., R. D. Williams, and M. A. Apicella. 2004. Gonococcal porin IB activates NF-κB in human urethral epithelium and increases the expression of host antiapoptotic factors. Infect. Immun. 726408-6417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Binnicker, M. J., R. D. Williams, and M. A. Apicella. 2003. Infection of human urethral epithelium with Neisseria gonorrhoeae elicits an upregulation of host anti-apoptotic factors and protects cells from staurosporine-induced apoptosis. Cell. Microbiol. 5549-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chae, H. D., T. S. Choi, B. M. Kim, J. H. Jung, Y. J. Bang, and D. Y. Shin. 2005. Oocyte-based screening of cytokinesis inhibitors and identification of pectenotoxin-2 that induces Bim/Bax-mediated apoptosis in p53-deficient tumors. Oncogene 244813-4819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang, F., L. S. Steelman, J. T. Lee, J. G. Shelton, P. M. Navolanic, W. L. Blalock, R. A. Franklin, and J. A. McCubrey. 2003. Signal transduction mediated by the Ras/Raf/MEK/ERK pathway from cytokine receptors to transcription factors: potential targeting for therapeutic intervention. Leukemia 171263-1293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Festjens, N., M. van Gurp, G. van Loo, X. Saelens, and P. Vandenabeele. 2004. Bcl-2 family members as sentinels of cellular integrity and role of mitochondrial intermembrane space proteins in apoptotic cell death. Acta Haematol. 1117-27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graf, R., S. Apenberg, M. Freyberg, and P. Friedl. 2003. A common mechanism for the mechanosensitive regulation of apoptosis in different cell types and for different mechanical stimuli. Apoptosis 8531-538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Han, J., L. A. Goldstein, B. R. Gastman, A. Rabinovitz, and H. Rabinowich. 2005. Disruption of Mcl-1. Bim complex in granzyme B-mediated mitochondrial apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 28016383-16392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harada, H., B. Quearry, A. Ruiz-Vela, and S. J. Korsmeyer. 2004. Survival factor-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase phosphorylates BIM, inhibiting its association with BAX and proapoptotic activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 10115313-15317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.He, Y. Y., J. L. Huang, and C. F. Chignell. 2004. Delayed and sustained activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase in human keratinocytes by UVA: implications in carcinogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 27953867-53874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Higashi, D. L., S. W. Lee, A. Snyder, N. J. Weyand, A. Bakke, and M. So. 2007. Dynamics of Neisseria gonorrhoeae attachment: microcolony development, cortical plaque formation, and cytoprotection. Infect. Immun. 754743-4753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Howie, H. L., M. Glogauer, and M. So. 2005. The N. gonorrhoeae type IV pilus stimulates mechanosensitive pathways and cytoprotection through a pilT-dependent mechanism. PLoS Biol. 3e100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hu, P., Z. Han, A. D. Couvillon, and J. H. Exton. 2004. Critical role of endogenous Akt/IAPs and MEK1/ERK pathways in counteracting endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced cell death. J. Biol. Chem. 27949420-49429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kang, Y. C., K. M. Kim, K. S. Lee, S. Namkoong, S. J. Lee, J. A. Han, D. Jeoung, K. S. Ha, Y. G. Kwon, and Y. M. Kim. 2004. Serum bioactive lysophospholipids prevent TRAIL-induced apoptosis via PI3K/Akt-dependent cFLIP expression and Bad phosphorylation. Cell Death Differ. 111287-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Konopleva, M., S. Zhao, Z. Xie, H. Segall, A. Younes, D. F. Claxton, Z. Estrov, S. M. Kornblau, and M. Andreeff. 1999. Apoptosis. Molecules and mechanisms. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 457217-236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuribara, R., H. Honda, H. Matsui, T. Shinjyo, T. Inukai, K. Sugita, S. Nakazawa, H. Hirai, K. Ozawa, and T. Inaba. 2004. Roles of Bim in apoptosis of normal and Bcr-Abl-expressing hematopoietic progenitors. Mol. Cell. Biol. 246172-6183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee, S. W., D. L. Higashi, A. Snyder, A. J. Merz, L. Potter, and M. So. 2005. PilT is required for PI(3,4,5)P3-mediated crosstalk between Neisseria gonorrhoeae and epithelial cells. Cell. Microbiol. 71271-1284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Letai, A., M. C. Bassik, L. D. Walensky, M. D. Sorcinelli, S. Weiler, and S. J. Korsmeyer. 2002. Distinct BH3 domains either sensitize or activate mitochondrial apoptosis, serving as prototype cancer therapeutics. Cancer Cell 2183-192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li, R., T. Moudgil, H. J. Ross, and H. M. Hu. 2005. Apoptosis of non-small-cell lung cancer cell lines after paclitaxel treatment involves the BH3-only proapoptotic protein Bim. Cell Death Differ. 12292-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu, J. W., D. Chandra, M. D. Rudd, A. P. Butler, V. Pallotta, D. Brown, P. J. Coffer, and D. G. Tang. 2005. Induction of prosurvival molecules by apoptotic stimuli: involvement of FOXO3a and ROS. Oncogene 242020-2031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maier, B., L. Potter, M. So, C. D. Long, H. S. Seifert, and M. P. Sheetz. 2002. Single pilus motor forces exceed 100 pN. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 9916012-16017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marani, M., D. Hancock, R. Lopes, T. Tenev, J. Downward, and N. R. Lemoine. 2004. Role of Bim in the survival pathway induced by Raf in epithelial cells. Oncogene 232431-2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merz, A. J., C. A. Enns, and M. So. 1999. Type IV pili of pathogenic neisseriae elicit cortical plaque formation in epithelial cells. Mol. Microbiol. 321316-1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Merz, A. J., M. So, and M. P. Sheetz. 2000. Pilus retraction powers bacterial twitching motility. Nature 40798-102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Morales, P., P. Reyes, M. Vargas, M. Rios, M. Imarai, H. Cardenas, H. Croxatto, P. Orihuela, R. Vargas, J. Fuhrer, J. E. Heckels, M. Christodoulides, and L. Velasquez. 2006. Infection of human Fallopian tube epithelial cells with Neisseria gonorrhoeae protects cells from tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis. Infect. Immun. 743643-3650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller, A., D. Gunther, V. Brinkmann, R. Hurwitz, T. F. Meyer, and T. Rudel. 2000. Targeting of the pro-apoptotic VDAC-like porin (PorB) of Neisseria gonorrhoeae to mitochondria of infected cells. EMBO J. 195332-5343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Muller, A., D. Gunther, F. Dux, M. Naumann, T. F. Meyer, and T. Rudel. 1999. Neisserial porin (PorB) causes rapid calcium influx in target cells and induces apoptosis by the activation of cysteine proteases. EMBO J. 18339-352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Petlickovski, A., L. Laurenti, X. Li, S. Marietti, P. Chiusolo, S. Sica, G. Leone, and D. G. Efremov. 2005. Sustained signaling through the B-cell receptor induces Mcl-1 and promotes survival of chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells. Blood 1054820-4827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pirbhai, M., F. Dong, Y. Zhong, K. Z. Pan, and G. Zhong. 2006. The secreted protease factor CPAF is responsible for degrading pro-apoptotic BH3-only proteins in Chlamydia trachomatis-infected cells. J. Biol. Chem. 28131495-31501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Puthalakath, H., and A. Strasser. 2002. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 9505-512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sheng, W., G. Wang, Y. Wang, J. Liang, J. Wen, P. S. Zheng, Y. Wu, V. Lee, J. Slingerland, D. Dumont, and B. B. Yang. 2005. The roles of versican V1 and V2 isoforms in cell proliferation and apoptosis. Mol. Biol. Cell 161330-1340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Song, G., G. Ouyang, and S. Bao. 2005. The activation of Akt/PKB signaling pathway and cell survival. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 959-71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sunters, A., S. Fernandez de Mattos, M. Stahl, J. J. Brosens, G. Zoumpoulidou, C. A. Saunders, P. J. Coffer, R. H. Medema, R. C. Coombes, and E. W. Lam. 2003. FoxO3a transcriptional regulation of Bim controls apoptosis in paclitaxel-treated breast cancer cell lines. J. Biol. Chem. 27849795-49805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tong, Z., G. Singh, and A. J. Rainbow. 2002. Sustained activation of the extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway protects cells from photofrin-mediated photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 625528-5535. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Turner, C. F., S. M. Rogers, H. G. Miller, W. C. Miller, J. N. Gribble, J. R. Chromy, P. A. Leone, P. C. Cooley, T. C. Quinn, and J. M. Zenilman. 2002. Untreated gonococcal and chlamydial infection in a probability sample of adults. JAMA 287726-733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vogel, V., and M. Sheetz. 2006. Local force and geometry sensing regulate cell functions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7265-275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Willis, S. N., and J. M. Adams. 2005. Life in the balance: how BH3-only proteins induce apoptosis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 17617-625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wolfgang, M., P. Lauer, H. S. Park, L. Brossay, J. Hebert, and M. Koomey. 1998. PilT mutations lead to simultaneous defects in competence for natural transformation and twitching motility in piliated Neisseria gonorrhoeae. Mol. Microbiol. 29321-330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yin, K. J., J. M. Lee, H. Chen, J. Xu, and C. Y. Hsu. 2005. Abeta25-35 alters Akt activity, resulting in Bad translocation and mitochondrial dysfunction in cerebrovascular endothelial cells. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 251445-1455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ying, S., B. M. Seiffert, G. Hacker, and S. F. Fischer. 2005. Broad degradation of proapoptotic proteins with the conserved Bcl-2 homology domain 3 during infection with Chlamydia trachomatis. Infect. Immun. 731399-1403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yoon, S., and R. Seger. 2006. The extracellular signal-regulated kinase: multiple substrates regulate diverse cellular functions. Growth Factors 2421-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]