Abstract

Background

Arginase (RocF) hydrolyzes L-arginine to L-ornithine and urea. While previously characterized arginases have an alkaline pH optimum and require activation with manganese, arginase from Helicobacter pylori is optimally active with cobalt at pH 6. The arginase from Bacillus anthracis is not well characterized; therefore, this arginase was investigated by a variety of strategies and the enzyme was purified.

Results

The rocF gene from B. anthracis was cloned and expressed in E. coli and compared with E. coli expressing H. pylori rocF. In the native organisms B. anthracis arginase was up to 1,000 times more active than H. pylori arginase and displayed remarkable activity in the absence of exogenous metals, although manganese, cobalt, and nickel all improved activity. Optimal B. anthracis arginase activity occurred with nickel at an alkaline pH. Either B. anthracis arginase expressed in E. coli or purified B. anthracis RocF showed similar findings. The B. anthracis arginase expressed in E. coli shifted its metal preference from Ni > Co > Mn when assayed at pH 6 to Ni > Mn > Co at pH 9. Using a viable cell arginase assay, B. anthracis arginase increased dramatically when the cells were grown with manganese, even at final concentrations of <1 μM, whereas B. anthracis grown with cobalt or nickel (≥500 μM) showed no such increase, suggesting existence of a high affinity and specificity manganese transporter.

Conclusion

Unlike other eubacterial arginases, B. anthracis arginase displays unusual metal promiscuity. The unique properties of B. anthracis arginase may allow utilization of a specific metal, depending on the in vivo niches occupied by this organism.

Background

Bacillus anthracis is a highly invasive, exceptionally virulent pathogen of mammals, with humans as accidental hosts [1]. B. anthracis possesses two virulence plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2, that encode for a tripartite secreted toxin and a poly-D-glutamic acid capsule, respectively [2-4]. The toxins can cause death or produce serious edema in infected individuals [5,6]. Despite many years of research, chromosomal loci have received little attention; however, a chromosomally-encoded cytotoxin, anthrolysin O, has been recently reported [7].

Arginase hydrolyzes L-arginine to L-ornithine and urea. This enzyme is found in both eubacteria and eucaryotes. However, relatively few eubacterial arginases have been characterized; most characterized arginases are from animals and yeasts [8-10]. We recently characterized an arginase (RocF) from the gastric pathogen, Helicobacter pylori [11], discovering a number of interesting and unique properties among the arginase superfamily. When we began this current study, the closest homolog of the H. pylori arginase (NCBI Accession Number: NP_208190) was that from B. anthracis (NCBI Accession number: YP_016761 [12]. Yet, the two RocF proteins share only 20% amino acid identity over the entire protein (27% when comparing the first 283 amino acids of H. pylori with the first 271 amino acids of B. anthracis). Arginase activity from H. pylori has recently been measured using a highly sensitive and quantitative assay that can determine enzyme activity from extracts, viable cells or the purified enzyme [11]. The rocF gene from H. pylori has been cloned into E. coli DH5α and confers arginase activity to E. coli (which does not possess a native arginase), suggesting that the rocF gene alone is sufficient to confer arginase activity [11].

L-arginine is used by macrophages to produce nitric oxide and other downstream reactive nitrogen species [13]. The production of nitric oxide by activated host macrophages is an effective antimicrobial agent and serves as an initial innate defense mechanism against pathogens [13]. Interestingly, the H. pylori arginase inhibits host nitric oxide production, allowing for survival of the organism when co-cultured with activated macrophages [14]. A similar situation likely occurs with the B. anthracis enzyme [15]. Additionally, H. pylori arginase decreases T lymphocyte proliferation and CD3ζ expression [16], arguing for the importance of this enzyme in multiple facets of host-pathogen interactions.

In addition to roles in pathogenesis, it is speculated that arginases have evolved to regulate the levels of arginine and ornithine within the cell [17]. Regulation of these amino acids is pivotal in protein synthesis, polyamine and nitric oxide production, and other cellular processes [17]. For example in H. pylori, expression of a second copy of the arginase gene, rocF, does not double the arginase activity, suggesting the bacterium has mechanisms to limit hydrolysis of the essential amino acid, arginine [18].

In organisms having a complete urea cycle, arginase is the final enzyme of the cycle; however, arginase is not found in most eubacteria [19]. In H. pylori, the urea is further hydrolyzed into carbon dioxide and ammonia via the enzyme urease [20]. Most eubacteria that contain an arginase also have the entire urea cycle. Examples include H. pylori and B. subtilis [20,21]. However, several arginase-containing bacteria apparently lack a complete urea cycle. Such organisms include B. licheniformis [22] and B. anthracis. This suggests that arginase in these latter bacteria has evolved a unique physiologic role in the cell. Several biochemical properties of the B. anthracis arginase had been preliminarily described [23]. Purified B. anthracis arginase had to be preactivated with 1 μM Mn2+ (MnSO4) and heat (37°C for 3 hours) (designated as heat-activation) for activity to be measured using a urea detection method [23]. Indeed, nearly all arginases require some type of heat activation step in the presence of manganese for catalytic activity [24]. For B. anthracis arginase, manganese was previously considered the most efficient cation activator and stabilizer, allowing the Mn2+-preactivated enzyme to maintain stability and activity even after exposure to 50–60°C for one hour [23]. Additionally, the enzyme showed optimal catalytic activity between pH 9.8 and 10.0 [23], a finding consistent will all arginases [25], except the H. pylori enzyme (see results) [11].

Activity of the purified B. anthracis arginase decreased significantly after dialysis and lyophilization; if the manganese-preactivated enzyme was treated with other divalent cations, a large decrease in arginase catalytic activity occurred [23]. Collectively, these earlier data suggested that the metal cofactor involved in B. anthracis arginase activity was manganese [23], with nickel and cobalt having no role or an inhibitory role. The earlier data also indicated that heat-activation was absolutely required for catalytic activity. Identification of the gene responsible for B. anthracis arginase was not previously reported.

While the toxin components produced by B. anthracis have been the primary focus of research, there is limited research on the organism's other genes and gene products. In this study, we sought to characterize in depth the chromosomally-encoded B. anthracis arginase using a variety of conditions not previously examined, using a sensitive enzyme assay. We also established an E. coli model for the B. anthracis arginase and determined whether arginase could be detected and characterized from viable organisms. We provide evidence that the enzyme has novel features not previously recognized. For example, the B. anthracis arginase displayed optimal activity with nickel in extracts and manganese in viable cells, but surprisingly did not absolutely require either heat activation or the addition of exogenous metal to detect arginase activity. The B. anthracis arginase gene could complement an H. pylori arginase mutant, conferring B. anthracis arginase-like properties to H. pylori.

Results

Characterization of arginase-containing extracts of B. anthracis 7702

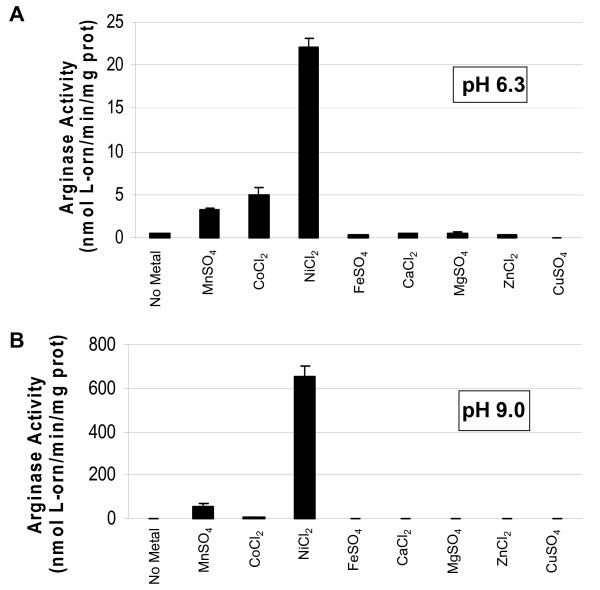

Many holes remain in our knowledge of the chromosomally-encoded arginase from B. anthracis. Also, no two eubacterial arginases have ever been directly compared for their properties under identical conditions. We therefore sought to investigate the B. anthracis arginase in much more detail and compared it to the H. pylori arginase. Extracts from B. anthracis 7702 assayed with manganese (Mn2+) or cobalt (Co2+) displayed arginase activity at both pH 6.3 and 9.0; however, when assayed in the presence of nickel (Ni2+) at pH 9.0, the activity was up to 500-fold higher than with Mn2+ or Co2+ (Fig. 1A &1B). This is in striking contrast to what was reported previously for this enzyme, in which Ni2+ inhibited activity [23].

Figure 1.

B. anthracis 7702 extracts show optimal catalytic activity with nickel. Cells were grown on CBA plates at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2 in air, harvested, and extracts prepared as described in Methods. The extracts were assayed with 5 mM (final concentration) of the appropriate metal after heat activation at pH 6.3 (A) or 9.0 (B) (Bis Tris Propane [BTP]-buffered arginine).

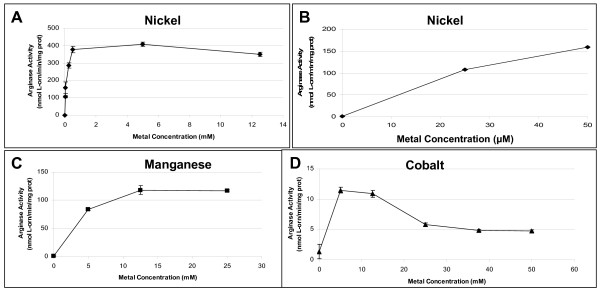

B. anthracis arginase activity was determined at various concentrations of nickel, manganese, or cobalt. Far lower concentrations of nickel were needed to obtain abundant arginase activity, than when cobalt or manganese were used (Fig. 2). Micromolar nickel activated arginase >2-fold more than the optimal level of manganese (400 U versus 125 U) and >100-fold higher than the optimal level of cobalt (400 U versus 12 U). Optimal concentrations for the three metals were as follows: nickel, ≥ 500 μM; manganese, ≥ 12.5 mM; and cobalt 5 mM (Fig. 2A–D). Since all three metals caused near optimal arginase activity at 5 mM, this concentration was used for most subsequent experiments.

Figure 2.

Effect of metal concentration on arginase activity in B. anthracis 7702 extracts. Cells were grown on CBA plates at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2 in air, harvested, and extracts prepared as described in Methods. The extracts were heat-activated (50–55°C for 30 minutes) with increasing concentrations of NiCl2 (A, high concentrations; B, low concentrations), MnSO4 (C), or CoCl2(D) at pH 9.0 (in BTP-buffered arginine).

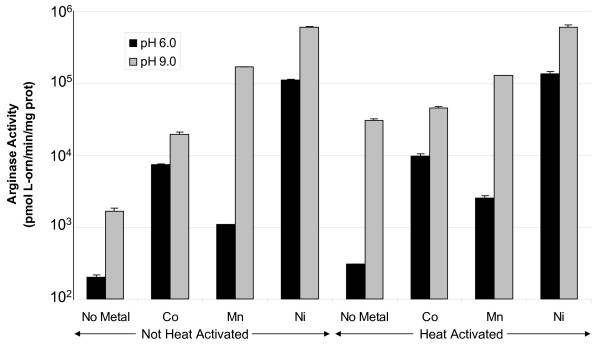

Heat activation is required for all previously characterized arginases [24,26], presumably to allow partial unfolding of the enzyme and incorporation of the metal cofactor. In a previous study, B. anthracis arginase activity decreased in samples exposed to heat, if the enzyme had not been already pre-activated with manganese [23]. In contrast with this earlier finding, we observed that B. anthracis arginase activity surprisingly increased about 10-fold following treatment with heat (50–55°C, 30 min) at pH 9.0 in the absence of metal versus no heat (Fig. 3). However, in the presence of various metals, heat treatment did not affect arginase activity at either pH 6.0 or 9.0, when compared to samples that were not heat-treated (Fig. 3). Under all conditions, nickel conferred that highest arginase catalytic activity.

Figure 3.

Effect of heat activation on the arginase activity of B. anthracis 7702 extracts. Cells were grown on CBA plates at 37°C for 24 h in 5% CO2 in air, harvested, and extracts prepared as described in Methods. The extracts were assayed with or without heat activation (50–55°C or on ice for 30 minutes, respectively) in the absence (no metal) or presence of 5 mM metal (Co, Mn, or Ni) at pH 6.0 (in MES-buffered arginine) or 9.0 (Tris-buffered arginine). There was no evidence of a buffer effect on activity (data not shown).

Comparative characteristics of the H. pylori and B. anthracis arginases

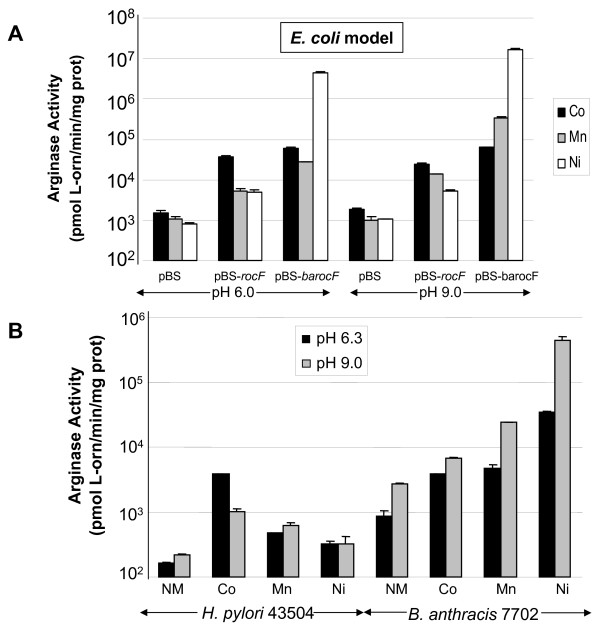

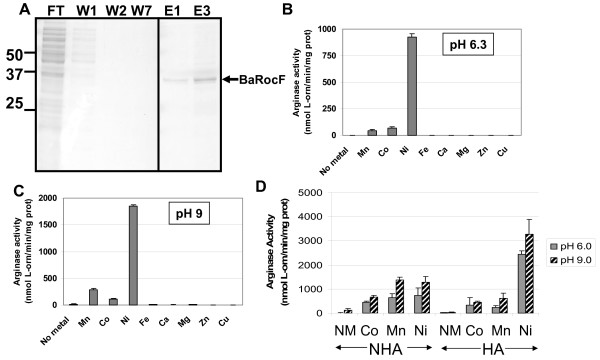

Since the H. pylori and B. anthracis arginases share low amino acid similarity (20% identity), we questioned whether the properties of these two enzymes were similar or distinct, when assayed under identical conditions. H. pylori and B. anthracis arginase activities expressed in E. coli DH5α were first compared (Fig. 4A). E. coli (pBS-barocF) had optimal arginase activity at both pH 6.0 and 9.0 with nickel, with lower activity in the presence of cobalt or manganese (Fig. 4A). At pH 6.0, E. coli (pBS-barocF) showed better activity with cobalt than with manganese (p < 0.05, Co versus Mn) (Fig. 4A). At pH 9.0, the optimal activating metal was nickel for E. coli (pBS-barocF), but higher arginase activity occurred when assayed with manganese rather than cobalt. With E. coli (pBS-rocF), optimal arginase activity was with cobalt (p < 0.05, Co versus Mn) (Fig. 4A) at either pH 6.0 or 9.0.

Figure 4.

Characteristics of arginase extracts from E. coli DH5α expressing the H. pylori or B. anthracis enzymes or from native organisms. Extracts were prepared from E. coli carrying H. pylori (pBS-rocF) or B. anthracis rocF (pBS-barocF) and grown in L broth at 37°C with aeration (A) or from 24 hour cultures of B. anthracis and H. pylori grown on CBA at 37°C in 10% CO2, 5% O2 (B). Extracts were heat-activated for 30 minutes at 50–55°C in the presence of ddH2O (no metal control), 5 mM CoCl2, MnSO4, or NiCl2 and assayed at pH 6.0 or 9.0 in MES-buffered arginine or Tris-buffered arginine, respectively (A) or at pH 6.3 or pH 9.0 in BTP-buffered arginine (B). Arginase activity data are the mean arginase activity ± standard deviation of one representative of at least two experiments (independently prepared extracts) conducted in triplicate. Under these conditions, E. coli DH5α(pBS) showed a background of ~1000 pmol L-orn/min/mg protein [U]. Lack of error bars on some bars indicates that the standard deviation was minimal and did not appear on the graph. NM, no metal.

Arginase activity of E. coli (pBS-barocF) was approximately 10-fold higher at pH 9.0 than at 6.0 in the presence of manganese (Fig. 4A, p < 0.005). While E. coli (pBS-rocF) displayed optimal activity with cobalt when assayed at different pHs, E. coli (pBS-barocF) had optimal activity with nickel at different pHs. As previously reported [11], the H. pylori arginase in the E. coli model (pBS-rocF) displayed optimal catalysis with cobalt at pH 6.0.

In addition, enzyme activities from native organisms were compared after growth under identical conditions (Campylobacter blood agar, 24 h, 37°C, 5% O2/10% CO2). While the B. anthracis enzyme had greater activity with nickel than without metal (>50-fold difference irrespective of pH), the enzyme still surprisingly retained activity even in the absence of metal (Fig. 4B, NM). At pH 9.0 arginase activity in B. anthracis extracts was up to 1000-fold higher than in H. pylori extracts depending on the metal present and the pH of assay (Fig. 4B). Even when assayed under sub-optimal conditions (e. g., pH 6 with manganese), the B. anthracis arginase was still more activity than the H. pylori enzyme (Fig. 4B). The only condition in which the H. pylori arginase was as active as the B. anthracis enzyme was when the enzymes were assayed at pH 6.3 in cobalt (Fig. 4B). The results suggest that the E. coli models nearly completely mimic the data obtained from native organisms.

Comparison of arginase activity between E. coli DH5α pBS-barocF and B. anthracis 7702

To strengthen the validity of the E. coli arginase model, we directly compared the arginase activities between E. coli (pBS-barocF) versus B. anthracis under identical conditions. Under most assay conditions, the arginase expressed in E. coli versus B. anthracis showed similar trends in that highest arginase activity occurred at pH 9 with nickel (data not shown). However, arginase activity in E. coli (pBS-barocF) was 5–15-fold higher than in B. anthracis under most conditions, probably due to increased gene dosage from the high-copy-number plasmid. The only case in which B. anthracis arginase activity was not significantly lower than arginase expressed in the E. coli model was when the extracts were assayed without metal. The second most optimal metal shifted from manganese at pH 9.0 to cobalt at pH 6.3, especially in the E. coli model (data not shown). In addition, there was substantial activity without heat treatment or without addition of exogenous metal (data not shown).

Metal dose-dependency of B. anthracis arginase activity using viable cells

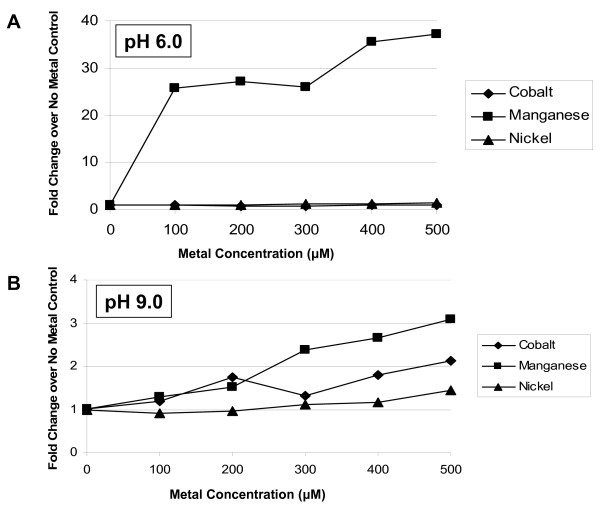

The B. anthracis arginase characteristics in live cells was examined to better ascertain whether the in vitro biochemical results would hold true in viable cells. Previously, we showed that E. coli (pBS-rocF) increases its arginase activity when grown with increasing concentrations of metal [11]. Here, we determined whether arginase could be detected in viable cells of B. anthracis or in E. coli (pBS-barocF), and if so, what metal was ideal for catalytic activity. In both viable cell models, arginase activity was detectable (Fig. 5 and 6). At pH 6.0 with E. coli (pBS-barocF), growing the cells in the presence of manganese (≥ 100 μM) increased arginase activity of viable cells (Fig. 5A); cobalt and nickel had no significant effect. At pH 9.0, there was evidence of a slight dose-dependent increase with cobalt, nickel, or manganese (Fig. 5B), with manganese showing the greatest effect.

Figure 5.

Effect of metal concentration on arginase activity in E. coli (pBS-barocF) whole cells. Cells were grown in the absence or presence of various concentrations of metal (CoCl2, MnSO4, or NiCl2). No effect on growth was observed at the concentrations used. Whole cells were harvested and assayed directly without heat treatment (ice, 30 min) at pH 6.0 (A) or 9.0 (B) using MES- or Tris-arginine buffer, respectively. Data shown is represented as the fold increase over the no metal control. Under these conditions, E. coli DH5α(pBS) showed a background of ~1000 pmol L-orn/min/mg protein [U]. Before fold-increases were calculated, 1000 U was subtracted from each E. coli DH5α (pBS-barocF) data point.

Figure 6.

Evidence that B. anthracis 7702 has a high affinity and specificity manganese transporter involved in arginase activity. B. anthracis 7702 were grown in BHI broth in the absence or presence of metal (CoCl2, MnSO4, NiCl2) at various concentrations. No effect on growth was observed at the concentrations used. Cells were harvested and assayed directly (viable whole cells) without heat treatment (ice, 30 min) at pH 9.0 using BTP-buffered arginine. Inset. B. anthracis grown with 0.2 to 1.0 μM MnSO4.

These experiments were also conducted in B. anthracis. Remarkably, arginase activity increased when the bacteria were grown with exceptionally low manganese concentrations (200 nM; Fig. 6 inset). Even at the highest level of cobalt or nickel that can be used without adversely affecting growth (500 μM for cobalt; 1 mM for nickel), cobalt or nickel had no effect on arginase activity (Fig. 6).

Disruption of the B. anthracis rocF in pBS-barocF abolishes arginase activity in E. coli

Above, it was demonstrated that B. anthracis rocF confers arginase activity to E. coli, suggesting that rocF is necessary and sufficient to confer arginase activity to E. coli. Further proof was obtained by disrupting the rocF gene in pBS-barocF and transforming the resultant plasmid, pBS-barocF::kan, into E. coli to yield two transformants. One transformant had the kanamycin cassette in the forward (F) orientation with respect to rocF, while the other had the cassette in the reverse (R) orientation. E. coli carrying either clone had no detectable arginase activity (0.84 ± 0.06 nmol L-ornithine/min/mg prot [U] for pBS-barocF::kan F and 0.73 ± 0.2 U for pBS-barocF::kan R), in contrast with pBS-barocF (3,320 ± 360 U) (heat-activated with manganese, BTP-arginine buffer, pH 9.0). E. coli carrying the insert-free vector control, pBS, had 0.57 ± 0.03 U of background activity under these conditions.

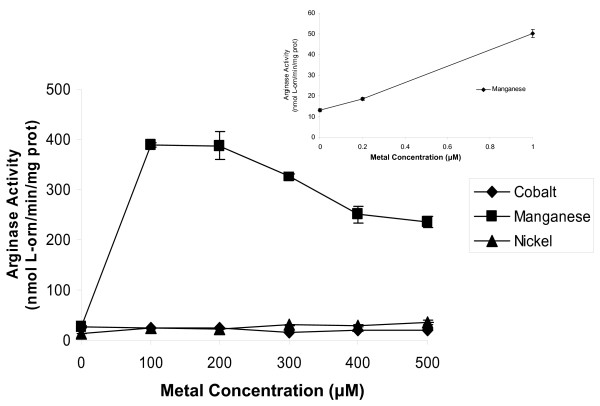

Characteristics of purified B. anthracis RocF

To determine whether the experimental results with B. anthracis and the E. coli model also hold true for the purified protein, we constructed an E. coli strain carrying the B. anthracis rocF gene translationally-fused to a his6 tag at the N-terminus (designated His6-BaRocF). Previous results indicated that the six histidine tag did not interfere with arginase activity [11]. The B. anthracis His6-BaRocF protein was purified to >95% homogeneity (Fig. 7A). Purified His6-BaRocF had a Km for arginine of 10 mM and a Vmax of 500 pmol/sec at pH 9.0 in the presence of 5 mM nickel.

Figure 7.

Characteristics of purified B. anthracis His6-BaRocF. A. Purification of His6-BaRocF. His6-BaRocF was purified as described in Methods and the flow-through (FT), washes (W) and elutions (E) analyzed by Coomassie blue-stained SDS-PAGE. Intervening lanes between W7 and E1 have been cropped out. B and C. Purified His6-BaRocF displays optimal catalytic activity with nickel. The purified enzyme was assayed with 5 mM of the appropriate metal after heat activation at pH 6.3 (B) or pH 9.0 (C) in Bis Tris Propane [BTP]-buffered arginine. At least two experiments were conducted for each sample in triplicate. Data are presented as mean arginase activity (nmol L-orn/min/mg protein) ± standard deviation. No Metal, assayed without metal. D. Effect of heat activation on the activity of His6-BaRocF. The purified arginase samples were assayed with or without heat activation (50–55°C or on ice for 30 minutes, respectively) in the absence (No Metal) or presence of 5 mM metal (CoCl2, MnSO4, or NiCl2) at pH 6.0 (in MES-buffered arginine) or 9.0 (Tris-buffered arginine). There was no evidence of a buffer effect on activity (data not shown). At least two experiments were conducted in triplicate for each sample. Data are presented as mean arginase activity (nmol L-orn/min/mg protein) ± standard deviation.

When purified His6-BaRocF samples were assayed in the presence of nickel, the activity was up to 100-fold higher than with manganese or cobalt (Fig. 7B, 7C), similar to the findings in B. anthracis extracts (Fig. 1). Little to no arginase activity occurred in the presence of other divalent cations. Additionally, the metal preference shifted from Ni > Co > Mn at pH 6.3 to Ni > Mn > Co at pH 9.0, as was observed in the E. coli model (Fig. 4A).

In a previous study, B. anthracis arginase activity decreased in samples exposed to heat (50–60°C), if the enzyme had not been pre-activated with manganese [23]. We determined that in the presence of cobalt, heat activation did not adversely affect arginase activity at pH 6.0 or 9.0, when compared to samples that were not heat-treated (Fig. 7D). Remarkably, heat treatment dramatically increased arginase activity in the presence of nickel at either pH 6.0 or 9.0. As observed in B. anthracis extracts and in extracts using the E. coli model, optimal catalytic activity was observed when the purified enzyme was assayed in the presence of nickel (Fig. 7D), rather than manganese or cobalt.

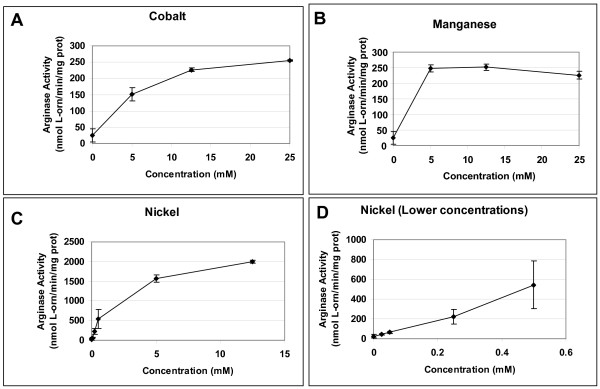

Catalytic activity of purified B. anthracis arginase was determined at various concentrations of nickel, manganese, or cobalt (Fig. 8). Nickel showed an increase in activity at a much lower concentration when compared to manganese or cobalt, confirming the results found in extract samples from the native organism and in E. coli expressing the B. anthracis arginase. Micromolar nickel concentrations activated arginase >2-fold more than the optimal level of manganese (544 nmol L-orn/min/mg prot [U] versus 251 U), similar to evidence from extract samples. Additionally, optimal concentrations for the three metals were: nickel, ≥ 12.5 mM; manganese, ≥ 5 mM; and cobalt, 25 mM (Fig. 8). At these optimal concentrations of metal, nickel conferred eight times more arginase activity than either manganese or cobalt.

Figure 8.

His6-BaRocF assayed in the presence of various concentrations of different metals. The purified arginase samples were heat activated (50–55°C for 30 minutes) with increasing concentrations of (A) CoCl2, (B) MnSO4, or (C, D) NiCl2 at pH 9.0 (in BTP-buffered arginine). At least two experiments were conducted for each sample in triplicate. Data are presented as mean arginase activity (nmol L-orn/min/mg protein) ± standard deviation.

Complementation of the H. pylori arginase mutant with the B. anthracis rocF gene

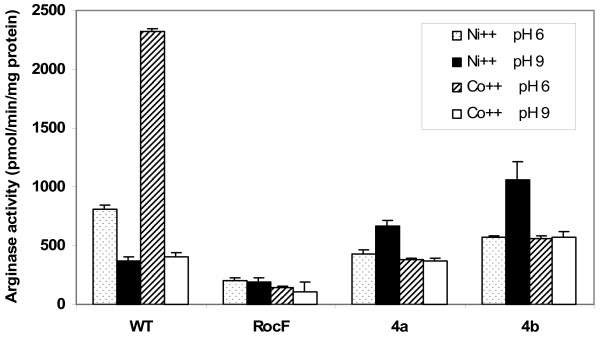

Since we were unsuccessful in several attempts to disrupt the rocF gene in B. anthracis, we instead transformed the B. anthracis rocF gene into an H. pylori rocF mutant devoid of arginase activity. This was achieved using the suicide plasmid complementation system developed previously [18], but with an improved vector backbone, pLSU0005 (see Methods). Expression of the B. anthracis rocF gene was driven off the strong H. pylori urease promoter. Transformation of the 26695 rocF mutant with the empty vector control was previously shown not to complement arginase activity, as expected [18]. H. pylori complemented clones 4a and 4b acquired arginase activity that exhibited B. anthracis properties, namely, optimal arginase activity at pH 9 with nickel (Fig. 9), but the overall activity was substantially lower than what is observed for native B. anthracis.

Figure 9.

Complementation of the H. pylori rocF mutant with the B. anthracis rocF gene. Cellular extracts from wild type H. pylori 26695 (WT), the 26695 rocF mutant (RocF) and the rocF complemented with the B. anthracis rocF gene (clones 4a and 4b) were assayed for arginase activity at pH 6.0 (MES-arginine buffer) or 9.0 (Tris-arginine buffer) in the presence of cobalt or nickel with heat activation (50°C for 30 minutes). Representative of two experiments conducted in triplicate.

Discussion

In this study arginase from B. anthracis was investigated under a variety of variables using six different models: i) extracts from B. anthracis; ii) extracts from E. coli (pBS-barocF); iii) viable cells of B. anthracis; iv) viable cells of E. coli (pBS-barocF); v) purified B. anthracis RocF (as His6-BaRocF); and vi) extracts from the H. pylori rocF complemented with B. anthracis rocF. In nearly every case, all models lead to the same conclusions. These conclusions are: i) B. anthracis arginase displays highest catalytic activity with nickel as the metal cofactor, when extracts or the purified protein is examined; ii) B. anthracis arginase is active without heat activation and without addition of metals, although cobalt, manganese, and nickel all improve activity; iii) the enzyme has much higher activity at pH 9.0 than at pH 6.0; iv) a viable cell arginase assay was developed in both B. anthracis and in an E. coli model and the characteristics of the enzyme mostly overlapped in the two models; v) viable cells exhibit far greater arginase activity when grown with manganese than with nickel or cobalt; vi) the B. anthracis arginase displays up to 1000-fold more specific activity than the H. pylori enzyme, depending on the conditions; vii) the B. anthracis rocF gene complements an H. pylori rocF mutant and confers B. anthracis-like arginase properties; and viii) the B. anthracis arginase gene is necessary and sufficient to confer arginase activity to E. coli.

Most bacteria that possess arginase have a complete urea cycle for eliminating excess nitrogen as urea. In striking contrast, B. anthracis contains arginase, but lacks the other enzymes of the urea cycle [23]. The role of arginase in B. anthracis pathogenesis and cellular physiology is only recently becoming understood [15,27], but our knowledge is far from complete. This current study uncovered novel characteristics about the enzyme as expressed in E. coli and in B. anthracis, and therefore lays important groundwork for future experiments in these areas. For the first time, it is demonstrated that the rocF gene from B. anthracis is the gene responsible for arginase activity, since E. coli containing B. anthracis rocF possessed arginase activity, while a kanamycin insertion into rocF abolished arginase activity. Thus, rocF was necessary and sufficient to confer arginase activity to E. coli. These results do not, however, rule out the possibility that B. anthracis contains genes that influence arginase expression or activity. Indeed, the B. anthracis genome contains a homologue of RocR, a positive transcriptional activator of the arginase-containing operon in B. subtilis [21].

Based on previous studies using the purified B. anthracis arginase [23], it was expected that the enzyme would be most active with manganese as its metal cofactor. In contrast, we identified nickel as the optimum metal cofactor for arginase activity in B. anthracis extracts, with purified His6-BaRocF, and with extracts from E. coli (pBS-barocF). Peak B. anthracis arginase activity was reached with much lower nickel concentrations than with manganese or cobalt. This suggests that in a cell-free system, the arginase has highest activity with nickel. The reason for the differences between our studies and those published previously [23] may be the use of an improved enzyme assay, coupled with our ability to assay the enzyme in multiple model systems that were unavailable 25 years ago. To our knowledge, this is the first arginase to have optimal activity with nickel. However, it is recognized that the actual metal found in vivo in B. anthracis native arginase is critical to study in the near future by inductively coupled plasma-mass spectrometry analysis. Such work cannot be accomplished with the current purified protein due to presence of the His6 tag and use of a nickel-containing column to purify the protein.

B. anthracis arginase was active with cobalt, manganese, and nickel. Therefore, depending on the pH and growth conditions, B. anthracis arginase can promiscuously utilize various metals to achieve catalytic activity. This metal promiscuity may allow the arginase to utilize the metal that is most readily available under a given environmental situation or in vivo condition encountered by B. anthracis. The only other reported bacterial arginase that has good activity with multiple metals is B. caldovelox (Table 1) [28], which has an arginase that is active with manganese, cobalt, cadmium and nickel. However, the B. caldovelox arginase protein (NCBI Accession Number: S68863), which is 73% identical to B. anthracis RocF, has optimal activity with manganese [28].

Table 1.

Summary of arginase properties from Bacillus spp. and H. pylori.

| Organism and putative metal-binding sitea | Urea cycle | pH optimum | Metal optimum | Regulation | Activity without metal | Reference(s) |

| H. pylori LYLDAHADIHT | Yes | 6 | Co2+ | Unknown | No | [11, 20], This study |

| B. anthracis IWYDAHGDLNT | No | 9 |

Extracts: Ni2+ > Mn2+ > Co2+ (pH 9.0), Ni2+ > Co2+ > Mn2+ (pH 6.0) Whole Cells: Mn2+ >> Ni2+ = Co2+ |

Unknown | Yes | [23], This study |

| B. caldovelox IWYDAHGDVNT | Unknown | 9–11 | Mn2+, Ni2+, Co2+, Cd2+ | Unknown | Yes | [17, 28] |

| B. licheniformis IWYDAHGDLNT | Unknown | 9.5–10.0 | Mn2+ | Oxygen, arginine, ornithine, proline, urea, glutamine, sporulation: all (+); glucose (-) | Yes | [19, 22, 26, 34, 39] |

| B. subtilis IWYDAHGDLNT | Yes | 9–11 | Mn2+ | RocR (+), AhrC (+); arginine, ornithine, citrulline, proline (all+) | Yes | [21, 40, 41] |

a Underlined region denotes amino acids most likely involved in metal binding.

In viable cells we showed that arginase activity can be directly assayed from E. coli expressing B. anthracis rocF or in native B. anthracis. This implies that the substrate, L-arginine, was transported into the cells, and was converted to urea and L-ornithine; the latter was measured in this study. Viable B. anthracis cells have up to ten-fold higher arginase activity with manganese than with cobalt or nickel (Fig. 6). This finding seemingly contradicts our earlier finding that the B. anthracis arginase in cell-free systems has highest activity with nickel. Two possible interpretations of this discrepancy are that i) B. anthracis arginase actually uses manganese rather than nickel in vivo and ii) B. anthracis arginase uses nickel, manganese or cobalt, depending on the situation. Since viable B. anthracis displayed a remarkable increase in arginase activity when the organisms were grown with extremely low levels of manganese (200 nM), we propose that B. anthracis expresses a very high affinity and specificity manganese transporter under our experimental conditions; this transporter would not be expected to transport nickel or cobalt, since addition of these metals did not increase B. anthracis arginase activity in viable cells (Fig. 6). It is speculated that such a transporter would be able to scavenge manganese from sites expected to be very low in manganese concentrations, such as would exist in vivo. Additional experiments are warranted to directly determine the metal cofactor found in the B. anthracis arginase active site.

The heat-activation step, which involves heating arginase at 50–60°C in the presence of metal, is required to obtain arginase activity in H. pylori and many other previously characterized arginases [11,24,26,29-31]. Previous studies have shown that heat-activation decreases B. anthracis arginase activity if manganese is absent [23]; we observed this with the purified protein as well. In contrast, we found that heating purified arginase in the presence of nickel dramatically improves activity over that of arginase that had not been heat-activated (Fig. 3). This result suggests that arginase may fold in a more ideal conformation with heat treatment in the presence of nickel than with cobalt or manganese, raising the possibility that nickel is the physiologic metal cofactor used by B. anthracis arginase. Despite these observations, however, substantial B. anthracis arginase activity still remains without heat-activation (Fig. 3, 8), unlike the case for most previously characterized arginases. Moreover, B. anthracis arginase has substantial activity without exogenously added metal (Fig. 3, 4), suggesting that sufficient levels of the residual metal cofactor may already be tightly bound to the enzyme's active site. This raises the possibility that the metal cofactor is more tightly bound to B. anthracis RocF than it is in other arginases. All of the other arginase have been proposed to have at least one of the two metal ions loosely bound to the active site [24,32,33].

We demonstrated that the H. pylori rocF mutant devoid of arginase activity could regain arginase activity with B. anthracis-like properties when the rocF mutant was complemented with the B. anthracis rocF gene (Fig. 9), suggesting that the B. anthracis RocF protein itself harbors at least some of the properties that allow it to have optimal activity with nickel. However, the B. anthracis rocF gene did not fully restore arginase activity to H. pylori even though a strongly active H. pylori urease promoter was used. This lack of full restoration may be due to codon usage differences between H. pylori and B. anthracis or to species-specific proteins that affect arginase activity. For example, H. pylori may have an arginase metal-delivering chaperone that does not recognize the B. anthracis enzyme. It is also possible that H. pylori has mechanisms to prevent arginase activity from becoming too high, which could lead to arginine starvation, since it was previously shown that wild type H. pylori carrying two copies of the arginase gene only have 25% more arginase activity than the wild type strain with a single copy [18]. Arginine is an essential amino acid for H. pylori but not B. anthracis. B. anthracis can therefore have much higher arginase activity without starving itself for arginine, since B. anthracis can synthesize more arginine intracellularly.

Table 1 summarizes the properties of a subset of eubacterial arginases. It is readily apparent that even within the genus Bacillus, whose arginases range from 66–99% identical at the amino acid level to B. anthracis, unique arginase properties exist. For example, multiple metals can be used for the arginase of B. caldovelox [28], while sporulation induces arginase in B. licheniformis [34], and the exosporium of spores from B. anthracis contain arginase activity [27]. While the putative metal-binding region is nearly completely conserved among the Bacillus species, there are a number of differences compared to the H. pylori arginase that may serve as important residues to target for site-directed mutagenesis.

Conclusion

The H. pylori arginase displays unique pH (6.0) and metal (cobalt) optima within the arginase superfamily. From the results of this study, the B. anthracis arginase likely displays a unique metal (nickel) optimum in the arginase superfamily and can potentially use multiple metals (cobalt, nickel, or manganese) to achieve catalytic activity suitable for its niche. Characteristic differences in arginases of B. anthracis versus H. pylori may reflect distinct in vivo niches occupied by these organisms. This study provides the foundation for further examination of the role of arginase in B. anthracis pathogenesis and cellular physiology.

Methods

Bacterial strains, growth conditions, and plasmids

Escherichia coli strain DH5α [F-, deoR, thi-1, gyrA96, recA1, endA1, relA1, supE44, Δ (lacZYA-argF) U169, hsdR17 (r-, m+), φ 80d lacZΔM15, λ-] (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) was used for standard cloning and transformation procedures. Strain XL1-Blue MRF' [F-, thi-1, gyrA96, recA1, endA1, relA1, supE44, lac, hsdR17 (r-, m+), F' [proAB, lacIqZ)M15, Tn10 [tetr]] E. coli was grown on Luria (L) agar and in L broth plus appropriate antibiotics (ampicillin, 100 μg/mL; kanamycin, 25 μg/mL; tetracycline 15 μg/mL) at 37°C for ~24 hours; if grown in broth, the cultures were aerated (225 rpm).

Bacillus anthracis Sterne toxigenic acapsulate strain 7702 (pXO1+, pXO2-) [7,35] was grown in Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) broth, L broth, or on Campylobacter agar with 10% (v/v) defibrinated sheep blood (CBA) at 37°C for ~24 hours in 5% CO2 in air or in 10% CO2, 5% O2, 85% N2; when grown in broth, cultures were aerated (225 rpm).

Helicobacter pylori 43504 was grown from frozen stocks for 72 hours on CBA at 37°C, passaged to fresh CBA for an additional 48 hours and then transferred to 25 mL Ham's F-12 plus 2% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, UT) and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. All conditions were microaerobic (10% CO2, 5% O2, 85% N2). The bacteria were then centrifuged for 10 min (6,000 × g) and resuspended in 600 μL 0.9% NaCl. Aliquots (100 μL) were spread onto 6 CBA plates and incubated at 37°C for 24 hours. The resultant cultures were used in the assays as described below.

Plasmid pBS [pBluescript II SK (+), Stratagene], pBS-rocF [11], and pBS-barocF (see below) were used in this study.

Molecular biology techniques

Plasmid DNA was isolated by the alkaline lysis method [36], or by using a column chromatography kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA) for sequencing-grade plasmid. Restriction endonuclease digestions, ligations, and other enzyme reactions were conducted according to the manufacturer's instructions (Promega, Madison, WI or New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA). PCR reactions (50 μL) contained 10 to 100 ng of DNA, PCR buffer, 2.0 to 2.5 mM MgCl2, dNTPs (each nucleotide at a concentration of 0.20 to 0.25 mM), 200 pmol of each primer, and 2.5 units of thermostable DNA polymerase. E. coli was transformed by the calcium chloride method or electroporation.

Cloning of B. anthracis rocF into pBS

The B. anthracis arginase gene, rocF (1104 bp), including the 893 bp coding region, 184 bp upstream, and 27 bp downstream was PCR-amplified from the chromosome using primers DM55(5'-cgggatccTTAATAATAATGATGGTAGTTGCTTCA-3') and DM56(5'-ccatcgatGCAACTTCTCAGTTGCTTTTCTTACAT-3') [uppercase letters: rocF gene; lowercase letters: BamHI (underlined) on the forward primer or ClaI (underlined) on the reverse primer]. The PCR product was digested with BamHI and ClaI and cloned into pBS digested with the same enzymes to generate pBS-barocF. The construct was confirmed by sequence analysis, restriction enzyme digestion (data not shown), and enzyme activity (see below). B. anthracis RocF, with a predicted mass of 32.7 kDa, was shown to be expressed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) analysis (data not shown).

Construction of pBS-barocF::kan

To disrupt the B. anthracis arginase gene, the plasmid pBS-kan [37] was digested with SmaI and HincII to generate the blunt-ended non-polar kanamycin resistance cassette (~1.3 kb), and pBS-barocF was digested with HindIII (~4.2 kb). The pBS-barocF linearized fragment was rendered blunt-ended by Klenow and ligated to the kanamycin cassette using the Roche Rapid DNA Ligation Kit (Roche Diagnostics Corporation, Indianapolis, IN). The ligation mixture was transformed into E. coli DH5α and doubly antibiotic resistant (kanamycin, ampicillin) transformants were verified by restriction digestion and arginase assay.

Construction of E. coli XL1-Blue MRF' (pQE30-barocF), overexpressing B. anthracis RocF

Plasmid pQE30 was digested with BamHI and KpnI, purified using the QIAquick Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). The DNA was dephosphorylated using shrimp alkaline phosphatase. The B. anthracis rocF coding region was amplified from the chromosome using DM184, 5'-GGggatccAAAAAAGAAATTTCGGTT-3' (with non-B. anthracis sequence designated as underlined capital letters and the BamHI site in lowercase letters) and DM67, 5'-GGggtaccCCTTTTAGTTTTTCACCGAATA-3'(with non-B. anthracis sequence designated as underlined capital letters and the KpnI site in lowercase letters). The ~900 bp PCR product was cloned into E. coli TOP10 using the pCR2.1 vector according to the manufacturer's instructions (TOPO TA Cloning Kit, Invitrogen Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA 92008). After digestion with BamHI and KpnI, the rocF gene was purified from the vector by agarose gel electrophoresis and ligated to the digested, phosphatase-treated pQE30 and transformed into XL1-Blue MRF' to yield pQE30-barocF. Transformants (ampr, tetr) were confirmed via restriction digestion analysis, PCR analysis, and arginase activity (data not shown).

Complementation of the H. pylori arginase mutant with the B. anthracis rocF gene

The B. anthracis rocF coding region was PCR-amplified from pBS-barocF using DM278 (5'-GCGCTGCAGGGATGAAAAAAGAAATTTCGG-3' and DM279 (5'-GCCCATGGCTTCTCAGTTGCTTTTCTTAC-3'). The ~900 bp product was digested with PstI and NcoI, and cloned downstream of the strong H. pylori urease promoter in pLSU0005 to yield pW7. Plasmid pLSU0005 is a derivative of suicide plasmid pIR203C04 [18] that has an improved multi-cloning site, the ureA promoter and a chloramphenicol resistance cassette and is used for complementation in H. pylori. Plasmid W7 (5 μg) was electroporated into the rocF mutant of H. pylori 26695 [38] and two chloramphenicol resistant transformants were confirmed by PCR analysis using flanking primers (data not shown); clones 4a and 4b were subsequently used.

Purification of the Bacillus anthracis arginase

E. coli XL1-Blue MRF' (pQE30-barocF) was grown overnight, diluted 1:100 in 500 mL of L broth plus ampicillin and tetracycline and the culture was incubated at 37°C, 225 rpm for 3–5 h (OD600 nm = ~0.7). Isopropyl thio-β-D-galactopyranoside (2.5 mM, final concentration) was added and the culture incubated for an additional 3–5 h at 37°C, 225 rpm. The resulting culture was centrifuged at 5,000 rpm (Sorval, SH-3000) for 15 min, 4°C. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was resuspended in 1/20th to 1/40th the original culture volume in Wash/Lysis buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 15 mM imidazole, pH 8.0). The bacteria were lysed by two passages through a French Press (16,000 psi) and maintained at 4°C throughout the remainder of the purification procedure. The lysates were then centrifuged and the supernatant containing arginase activity was retained. For every 680 μL of cytosol, 320 μL of nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid/ethanol agarose resin (Ni-NTA, Qiagen) was added. This solution was gently mixed end-over-end for 1–2 h at 4°C. The cytosol/Ni-NTA agarose mixture was equally distributed among two, 8.5 by 2.0 cm polypropylene columns. The flow through was reserved in sterile polypropylene test tubes, and the columns were washed 6–8 times with ~10 mL Wash/Lysis buffer per wash. These washes were retained for SDS-PAGE analysis. The protein was eluted using Elution Buffer (50 mM NaH2PO4, 300 mM NaCl, 250 mM imidazole, pH 8.0) at 1 mL per elution, for a total of 12 elutions per column. The flow through fractions, washes, and elutions were analyzed for protein by SDS-PAGE, and the elutions were monitored for arginase activity (data not shown). All samples were stored at 4°C or at -20°C in 50% glycerol.

Preparation of arginase-containing extracts

Bacteria were harvested from solid medium using a sterile swab and resuspended in 0.9% NaCl or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS). Broth-grown cells were centrifuged at 16,000 × g for 5 minutes. The pelleted cells were resuspended in 150 μl of 0.9% NaCl or PBS. For whole cell assays, bacteria were directly assayed. For extracts, the suspensions were sonicated (25% intensity, Sonic Dismembrator Model 500, Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) in an ice bath twice for 30 sec with a minimum 30 sec rest on ice between pulses. Following sonication, the lysate was clarified by centrifugation at 16,000 × g for 5 minutes. The resulting supernatant was retained on ice and used the same day for determination of arginase activity.

Arginase Assay

Extracts or viable bacteria were characterized using the standard arginase assay described previously [11] or with variations (described below). The sample (25 μl) was added to 25 μL of CoCl2, MnSO4, NiCl2, FeSO4, CaCl2, MgSO4, ZnCl2, or CuSO4 (final concentration of 5 mM, except as noted) or 25 μL of deionized distilled H2O (ddH2O, no metal control). An L-ornithine (0 to 3125 μM) standard curve was generated (extinction coefficient was typically 0.00045 to 0.00070 μM-1). The samples and standards were heat-activated (50–55°C, 30 min) or were maintained on ice for 30 min. Next, 200 μL of buffered 10 mM L-arginine (15 mM MES [2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid], pH 6.0; 15 mM Tris, pH 9.0; or 15 mM Bis-Tris Propane [BTP], pH 6.3 or 9.0) was added, and the samples were incubated at 37°C for 1 hour. Enzyme rates were linear at this time point. The reaction was stopped by the addition of acidified ninhydrin (4 mg/mL). After heating for one hour at 90–95°C, the standards and samples were measured spectrophotometrically at 515 nm (Biomate 3, Thermo Spectronic, Rochester, NY) in 1.5 ml cuvettes. Representative data were normalized for protein and are presented as specific activity in pmol or nmol L-ornithine/min/mg protein ± standard deviation with a minimum of two experiments conducted in duplicate or triplicate. Some graphs were converted to log scale since the enzyme activity is much higher under certain experimental conditions. Some experiments were performed using BTP as a buffer, because it had a broad buffering capacity of pH 6.3 to 9.5, which would eliminate any potential buffer effects. It was determined that biochemical intermediates and end products, such as putrescine, spermidine, spermine and urea, did not react with ninhydrin (data not shown).

Protein determinations

Protein determinations were performed by the Bicinchoninic Acid assay (Pierce Chemical Company, Rockford, IL), following the manufacturer's 30 minute method. NaCl or PBS was used as the negative control. The results were calculated by a standard curve using bovine serum albumin.

SDS-PAGE analysis

Proteins were electrophoresed through an SDS-polyacrylamide gel (12%) by standard methods.

Statistical Analyses

An unpaired two-tailed Welch's t test was used to determine statistical relationships (GraphPad Instat 3.05). p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Authors' contributions

RJV co-designed and conducted nearly all of the experiments and drafted the manuscript and figures in partial fulfillment of requirements for the Masters degree. EH conducted the experiments on complementation of H. pylori arginase with the B. anthracis rocF; RFR provided scientific advice and assisted with the writing; DJM directed the project and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by Public Health Service grant R01 CA101931 (to DJM) and U54 AI57168 (to RFR) from the National Institutes of Health, and a grant from Drexel University College of Medicine (to RFR).

We thank Dr. John W. Foster for helpful discussions and Emily L. Watson for technical support.

Contributor Information

Ryan J Viator, Email: rjv302@jaguar1.usouthal.edu.

Richard F Rest, Email: Richard.Rest@DrexelMed.edu.

Ellen Hildebrandt, Email: ehilde@lsuhsc.edu.

David J McGee, Email: dmcgee@lsuhsc.edu.

References

- Koehler TM, Dai Z, Kaufman-Yarbray M. Regulation of the Bacillus anthracis protective antigen gene: CO2 and a trans-acting element activate transcription from one of two promoters. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:586–595. doi: 10.1128/jb.176.3.586-595.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fish DC, Mahlandt BG, Dobbs JP, Lincoln RE. Purification and properties of in vitro-produced anthrax toxin components. J Bacteriol. 1968;95:907–918. doi: 10.1128/jb.95.3.907-918.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leppla SH. Bacillus anthracis calmodulin-dependent adenylate cyclase: chemical and enzymatic properties and interactions with eucaryotic cells. Adv Cyclic Nucleotide Protein Phosphorylation Res. 1984;17:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanley JL, Smith H. Purification of factor I and recognition of a third factor of the anthrax toxin. J Gen Microbiol. 1961;26:49–63. doi: 10.1099/00221287-26-1-49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beall FA, Taylor MJ, Thorne CB. Rapid lethal effect in rats of a third component found upon fractionating the toxin of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 1962;83:1274–1280. doi: 10.1128/jb.83.6.1274-1280.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, Stoner HB. Anthrax toxic complex. Fed Proc. 1967;26:1554–1557. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon JG, Ross CL, Koehler TM, Rest RF. Characterization of anthrolysin O, the Bacillus anthracis cholesterol-dependent cytolysin. Infect Immun. 2003;71:3183–3189. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.6.3183-3189.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis RH. Compartmental and regulatory mechanisms in the arginine pathways of Neurospora crassa and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:280–313. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.280-313.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green SM, Eisenstein E, McPhie P, Hensley P. The purification and characterization of arginase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:1601–1607. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sumrada RA, Cooper TG. Nucleotide sequence of the Saccharomyces cerevisiae arginase gene (CAR1) and its transcription under various physiological conditions. J Bacteriol. 1984;160:1078–1087. doi: 10.1128/jb.160.3.1078-1087.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee DJ, Zabaleta J, Viator RJ, Testerman TL, Ochoa AC, Mendz GL. Purification and characterization of Helicobacter pylori arginase, RocF: unique features among the arginase superfamily. Eur J Biochem. 2004;271:1952–1962. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Read TD, Peterson SN, Tourasse N, Baillie LW, Paulsen IT, Nelson KE, Tettelin H, Fouts DE, Eisen JA, Gill SR, Holtzapple EK, Okstad OA, Helgason E, Rilstone J, Wu M, Kolonay JF, Beanan MJ, Dodson RJ, Brinkac LM, Gwinn M, DeBoy RT, Madpu R, Daugherty SC, Durkin AS, Haft DH, Nelson WC, Peterson JD, Pop M, Khouri HM, Radune D, Benton JL, Mahamoud Y, Jiang L, Hance IR, Weidman JF, Berry KJ, Plaut RD, Wolf AM, Watkins KL, Nierman WC, Hazen A, Cline R, Redmond C, Thwaite JE, White O, Salzberg SL, Thomason B, Friedlander AM, Koehler TM, Hanna PC, Kolsto AB, Fraser CM. The genome sequence of Bacillus anthracis Ames and comparison to closely related bacteria. Nature. 2003;423:81–86. doi: 10.1038/nature01586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nathan C, Shiloh MU. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen intermediates in the relationship between mammalian hosts and microbial pathogens. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:8841–8848. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gobert AP, McGee DJ, Akhtar M, Mendz GL, Newton JC, Cheng Y, Mobley HL, Wilson KT. Helicobacter pylori arginase inhibits nitric oxide production by eukaryotic cells: a strategy for bacterial survival. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:13844–13849. doi: 10.1073/pnas.241443798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raines KW, Kang TJ, Hibbs S, Cao GL, Weaver J, Tsai P, Baillie L, Cross AS, Rosen GM. Importance of nitric oxide synthase in the control of infection by Bacillus anthracis. Infection & Immunity. 2006;74:2268–2276. doi: 10.1128/IAI.74.4.2268-2276.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zabaleta J, McGee DJ, Zea AH, Hernandez CP, Rodriguez PC, Sierra RA, Correa P, Ochoa AC. Helicobacter pylori arginase inhibits T cell proliferation and reduces the expression of the TCR z-chain (CD3z) J Immunol. 2004;173:586–593. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.1.586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bewley MC, Jeffrey PD, Patchett ML, Kanyo ZF, Baker EN. Crystal structures of Bacillus caldovelox arginase in complex with substrate and inhibitors reveal new insights into activation, inhibition and catalysis in the arginase superfamily. Structure Fold Des. 1999;7:435–448. doi: 10.1016/S0969-2126(99)80056-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langford ML, Zabaleta J, Ochoa AC, Testerman TL, McGee DJ. In Vitro and In Vivo Complementation of the Helicobacter pylori Arginase Mutant Using an Intergenic Chromosomal Site. Helicobacter. 2006;11:477–493. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2006.00441.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunin R, Glansdorff N, Pierard A, Stalon V. Biosynthesis and metabolism of arginine in bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1986;50:314–352. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.3.314-352.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendz GL, Hazell SL. The urea cycle of Helicobacter pylori. Microbiology. 1996;142:2959–2967. doi: 10.1099/13500872-142-10-2959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardan R, Rapoport G, Debarbouille M. Role of the transcriptional activator RocR in the arginine-degradation pathway of Bacillus subtilis. Mol Microbiol. 1997;24:825–837. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3881754.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broman K, Lauwers N, Stalon V, Wiame JM. Oxygen and nitrate in utilization by Bacillus licheniformis of the arginase and arginine deiminase routes of arginine catabolism and other factors affecting their syntheses. J Bacteriol. 1978;135:920–927. doi: 10.1128/jb.135.3.920-927.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soru E. Chemical and immunological properties of B. anthracis arginase and its metabolic involvement. Mol Cell Biochem. 1983;50:173–183. doi: 10.1007/BF00285642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohamed MS, Greenberg DM. Liver Arginase I. Preparation of extracts of high potency, chemical properties, activation-inhibition, and pH activity. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1945;8:349–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson CP, Grody WW, Cederbaum SD. Comparative properties of arginases. Comp Biochem Physiol B Biochem Mol Biol. 1996;114:107–132. doi: 10.1016/0305-0491(95)02138-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirsch-Kolb H, Heine JP, Kolb HJ, Greenberg DM. Comparative physical-chemical studies of mammalian arginases. Comp Biochem Physiol. 1970;37:345–359. doi: 10.1016/0010-406X(70)90563-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver J, Kang TJ, Raines KW, Cao GL, Hibbs S, Tsai P, Baillie L, Rosen GM, Cross AS. Protective role of Bacillus anthracis exosporium in macrophage-mediated killing by nitric oxide. Infection & Immunity. 2007;75:3894–3901. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00283-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patchett ML, Daniel RM, Morgan HW. Characterisation of arginase from the extreme thermophile 'Bacillus caldovelox'. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1077:291–298. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(91)90543-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg DM, Bagot AE, Roholt OA., Jr. Liver arginase. III. Properties of highly purified arginase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1956;62:446–453. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(56)90143-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramaley RF, Bernlohr RW. Postlogarithmic phase metabolism of sporulating microorganisms. II. The occurrence and partial purification of an arginase. J Biol Chem. 1966;241:620–623. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreier HJ, Smith TM, Bernlohr RW. Regulation of nitrogen catabolic enzymes in Bacillus spp. J Bacteriol. 1982;151:971–975. doi: 10.1128/jb.151.2.971-975.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown GW., Jr. Studies in comparative biochemistry and evolution. I. Avian liver arginase. Arch Biochem Biophys. 1966;114:184–194. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(66)90320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christianson DW. Arginase: structure, mechanism, and physiological role in male and female sexual arousal. Acc Chem Res. 2005;38:191–201. doi: 10.1021/ar040183k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon JP, Stalon V. Purification and structure of arginase of Bacillus licheniformis. Biochimie. 1976;58:1419–1421. doi: 10.1016/S0300-9084(77)80029-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataldi A, Labruyere E, Mock M. Construction and characterization of a protective antigen-deficient Bacillus anthracis strain. Mol Microbiol. 1990;4:1111–1117. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1990.tb00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. In: Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. 2nd. Laboratory CSH, editor. Cold Spring Harbor, N. Y. ; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- McGee DJ, Coker C, Testerman TL, Harro JM, Gibson SV, Mobley HL. The Helicobacter pylori flbA flagellar biosynthesis and regulatory gene is required for motility and virulence and modulates urease of H. pylori and Proteus mirabilis. J Med Microbiol. 2002;51:958–970. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-51-11-958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee DJ, Radcliff FJ, Mendz GL, Ferrero RL, Mobley HL. Helicobacter pylori rocF is required for arginase activity and acid protection in vitro but is not essential for colonization of mice or for urease activity. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:7314–7322. doi: 10.1128/jb.181.23.7314-7322.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laishley EJ, Bernlohr RW. Regulation of arginine and proline catabolism in Bacillus licheniformis. J Bacteriol. 1968;96:322–329. doi: 10.1128/jb.96.2.322-329.1968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baumberg S, Harwood CR. Carbon and nitrogen repression of arginine catabolic enzymes in Bacillus subtilis. J Bacteriol. 1979;137:189–196. doi: 10.1128/jb.137.1.189-196.1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Hauwer G., R. Lavelle, and J. M. Wiame. Pyrroline dehydrogenase and catabolism regulation of arginine and proline in Bacillus subtilis. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1964;81:257–269. [Google Scholar]