Abstract

This study investigated whether a microbubble-containing ultrasound contrast agent had a role in the antivascular action of physiotherapy ultrasound on tumor neovasculature. Ultrasound images (B-mode and contrast-enhanced power Doppler [0.02mL Definity]) were made of 22 murine melanomas (K173522). The tumor was insonated (ISATA = 1.7 W cm−2, 1 MHz, continuous output) for 3 min and the power Doppler observations of the pre- and post-insonation tumor vascularities were analyzed. Significant reductions (p = 0.005 for analyses of color weighted fractional area) in vascularity occurred when a contrast-enhanced power Doppler study occurred prior to insonation. Vascularity was unchanged in tumors without a pre-therapy Doppler study. Histological studies revealed tissue structural changes that correlated with the ultrasound findings. The underlying etiology of the interaction between the physiotherapy ultrasound beam, the microbubble-containing contrast agent and the tumor neovasculature is unknown. It was concluded that contrast agents play an important role in the antivascular effects induced by physiotherapy ultrasound.

Keywords: Ultrasound imaging, Cancer therapy, Physiotherapy, Antivascular, Tumor angiogenesis, Power Doppler, Insonation, Ultrasound bioeffects, Microbubble contrast agent

INTRODUCTION

The role of angiogenesis in sustaining tumor growth has been demonstrated in several studies (Carmeliet and Jain 2000; Folkman 2001; Haroon et al. 1999; Jain 2002). Since neoangiogenic vessels are fragile, leaky and dysfunctional (Carmeliet and Conway 2001; Haroon et al. 1999; Jain 2002), they are targeted for therapy. In our previous studies we found the neovasculature of a murine melanoma to be uniquely sensitive to low-intensity, physiotherapy ultrasound (Wood et al. 2005; Bunte et al. 2006). Utilizing a microbubble ultrasound contrast agent, and power Doppler imaging (prior to and following therapy of the neoplasm) it was shown that continuous physiotherapy ultrasound had a pronounced antivascular effect. Each minute of insonation at moderate intensity (spatial-average-temporal-average [ISATA] = 2.3 W cm−2) reduced tumor vascularity by 25%. Therapy was performed at least 5 min after the contrast agent was no longer detectable in the pre-treatment power Doppler images. The predominant acute effect of insonation was an irreparable dilation of the tumor capillaries with associated intercellular edema (Bunte et al. 2006). Hemorrhage, and increased intercellular fluid were other immediate effects observed following ultrasound therapy. Liquefactive necrosis of neoplastic cells was observed as a delayed effect, however, it appeared not to be related to a direct effect of ultrasound on the neoplastic cells, but rather to a generalized tumor ischemia following the acute effects of insonation on the neoplasm’s capillaries. Pre-existing arterioles and venules, that were enveloped by the growing neoplasm were unaffected by the ultrasound treatment.

In vivo (lithotripsy exposure; Dalecki et al. 1997) and in vitro experiments (500 kHz exposure; Kamaev et al. 2004) with microbubble contrast agents have suggested that interactions may occur between the ultrasound beam and the microbubble, or fragments of its shell, and lead to significant bioeffects. Further, the presence of circulating contrast microbubbles during high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) therapy increased tissue damage and improved its therapeutic efficiency (Tran et al. 2003, Yu et al. 2004). Other in vitro observations (Razansky et al. 2006) of physiotherapy ultrasound beams (1.0 – 3.2 MHz, ISATA = 0.1 – 1.1 W cm−2) showed that in the presence of a microbubble contrast agent there was an increased dissipation of acoustic power to heat and it was hypothesized that in vivo insonation of the circulating microbubbles could cause a localized hyperthermia in tissues. The current study was aimed at determining whether an intravenously administered microbubble contrast agent, used for the power Doppler ultrasound observations prior to tumor insonation, played a role in the observed antivascular effect of physiotherapy ultrasound.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Murine tumor model and ultrasonography

The previously described tumor model (Wood et al. 2005, Bunte et al. 2006) was approved by the University of Pennsylvania’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. In summary, two million murine melanoma cells (K173522) were injected subcutaneously in the right flank of 22 female mice (C3HV/HeN strain; Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA, USA). Within 17 to 41 days the tumor had grown to at least 9 mm in one dimension, and for the ultrasonographic studies a tail vein was catheterized and general anesthesia was induced and maintained with isoflurane (Wood et al. 2005). B-mode ultrasonographic and contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations were made of the tumor (7–15 MHz probe; HDI 5000 SonoCT, Philips, Bothell, WA, USA).

Tumour insonation and experimental design

When the tumor was at least 9 mm in one dimension it was insonated (ISATA = 1.7 W cm−2) with a physiotherapy ultrasound machine (1 MHz, continuous output, power level = 2; D150 Plus, Dynatronics Corp., Salt Lake City, UT, USA) for three min. The effective intensity of the ultrasound beam was measured using a radiation force balance (UPM 30, Ultrasound Power Meter, Ohmic Instruments Co, St Michaels, MD, USA; Wood et al. 2005). Sonographic gel was applied to the skin overlying the tumor and the insonation was made by direct contact between the transducer and the tumor. There was a 5 min gap between each min of insonation, during which time the face of the physiotherapy transducer was placed in water at room temperature. Physiotherapy ultrasound beams are unfocused and the transducer used in this study had an effective radiating area of 7 cm2.

The mice were randomly divided into two control and two test groups as follows:

1. In the first control group (group A; n = 6) a sham therapy was performed. An initial B-mode study was followed by the intravenous injection of an ultrasound contrast agent (0.02 mL Definity, Bristol-Myers Squibb Medical Imaging, North Billerica, MA, USA) and contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations were made. 15 min after the contrast agent was no longer detectable in these initial power Doppler observations, the physiotherapy transducer was applied to the tumor but was not switched on - 30 min after this sham treatment the B-mode and contrast-enhanced power Doppler studies were repeated.

2. The second control group (group B; n = 6) did not receive a pre-therapy injection of a microbubble-containing ultrasound contrast agent. There was an initial B-mode study of the tumor but no contrast-enhanced power Doppler observation was undertaken. Tumor therapy was performed 15 min after the initial B-mode study, and 30 min later B-mode and contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations were made.

3. In the first test group (group C; n =5), the initial B-mode and contrast-enhanced power Doppler studies were followed, 15 min after the contrast agent was no longer detectable in the Doppler study, by insonation of the tumor with physiotherapy ultrasound. 30 min after therapy the B-mode and contrast-enhanced power Doppler studies were repeated.

4. In the second test group (group D; n = 5), a similar study to Group C was conducted, however, tumor therapy was performed 60 min after the contrast agent was no longer detectable in the initial contrast-enhanced power Doppler study. The enhancement of all power Doppler images was digitally recorded for quantitative analysis.

Analysis of contrast-enhanced power Doppler data

To determine the size of the vascular area in each neoplasm, the following observations were made of the contrast-enhanced power Doppler ultrasonographic images prior to and following insonation:

1. visual estimation of tumor vascularity

After the injection of the microbubble contrast agent a visual estimation of the vascularity of the tumor, expressed as the percentage vascular area as seen in the image the ultrasound display monitor, was made for each contrast-enhanced power Doppler study.

2. percentage area of flow (PAF)

Digital contrast-enhanced power Doppler images (Wood et al. 2005) were analyzed for color level representing the Doppler signal (Sehgal et al. 2000, 2001). The color palette on the image was read and the colors between the lowest and highest in the palette were divided equally on a scale of 0–100. With this scaling system, the computer program constructed a “look-up” table from the hue, saturation, and brightness values of the colors present in the palette bar. Using the look-up table, the computer identified the colored pixels within the power Doppler image of the tumor. It counted the number of colored pixels (n); the percent area covered by colored pixels (PAF) was calculated as n.100/N, where N is the total number of pixels in the contrast enhanced power Doppler image. The PAF represented the size of the area of the tumor that was perfused with blood containing the contrast agent.

3. color-weighted flow area (CWFA)

The CWFA was obtained from the digital images by weighting each colored pixel the PAF by its color level (Sehgal et al. 2000, 2001). If there are ni pixels of color levels ‘i’, the CWFA was determined by the formula:

Because the color level of pixels in the power Doppler image is related to the concentration of moving scatterers, CWFA is a measure of the volume of contrast agent flowing through the unit volume (voxels) of the tumor within the image plane.

4. cumulative histogram area

In our previous analysis of the contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations (Wood et al. 2005, Bunte et al. 2006) we proposed the use of the area under the cumulative histogram curve of the tumor pixels as a measure of tumor avascularity. The parameter takes into consideration every pixel of the histogram, but its physical meaning may, however, be non-intuitive and difficult to interpret. As part of this study we demonstrated that an analysis of contrast-enhanced power Doppler images based on the cumulative histogram area fully correlated with the simpler measurement of CWFA (Appendix A).

The parameters for each group of mice were recorded as a mean ± standard deviation (SD). A paired t-test (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium) was used to determine within groups whether there was any significant effect of insonation on tumor vascularity as assessed by a visual estimation, PAF, CWFA, and cumulative histogram area. For each of the four parameters in Group B, where the initial contrast-enhanced power Doppler study was not performed, the pre-insonation values for vascularity were taken as the mean value from the pre-insonation observations of all other mice (n = 16) and an unpaired t - test was performed. An unpaired t – test was also used to analyze the differences between the mean change in vascularity observed (visual, PAF, CWFA) between the different groups of mice. In each analysis the difference was considered significant when p < 0.05. Linear regression analyses were performed to demonstrate whether there were correlations between the visual and PAF, and visual and CWFA observations of tumor vascularity.

Histologic studies

At the completion of each experiment the mouse was euthanized. The tumor was removed, fixed, embedded in paraffin, and sections taken from the mid-portion of each neoplasm were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and viewed with a light microscope (Bunte et al. 2006). The histopathologist was unaware of the treatment given to each neoplasm. As undertaken previously, in each tumor sample the absence or presence of dilated vascular channels (with associated intercellular edema), hemorrhage, necrosis of cancer cells, and pseudocyst formation was determined by visual inspection, and for each histological change the % area of the total surface of the neoplastic tissue affected in the slide was recorded (Bunte et al. 2006). The results were also expressed as the average total % area affected in the histological specimens of each neoplasm and the mean ± SD of the measurements for each group of mice was calculated. The extent of increased intercellular fluid was also quantified and expressed as a score (absent: score = 0; mild: score = 1; moderate: score = 2: severe: score = 3); the scores in the histologic slides of each mouse were averaged and the mean ± SD of the scores for each group of mice was calculated. To determine whether the alterations in the total % area affected across groups of mice, and the changes in incidence of any of the observed histologic changes were statistically significant, the data were analyzed with unpaired t-tests (MedCalc Software, Mariakerke, Belgium); the difference was considered significant when p < 0.05. A linear regression analysis was performed to establish whether there was a relationship between the total % area of histological change and the % decrease in tumor vascularity following insonation (as demonstrated by PFA and CWFA in the contrast-enhanced power Doppler images). The presence of post-insonation, peri-tumor edema and pre-existing structures (arterioles, venules, nerves, adipocytes, skeletal muscle fibers and mammary ducts) within the neoplasm were also noted.

RESULTS

Ultrasound

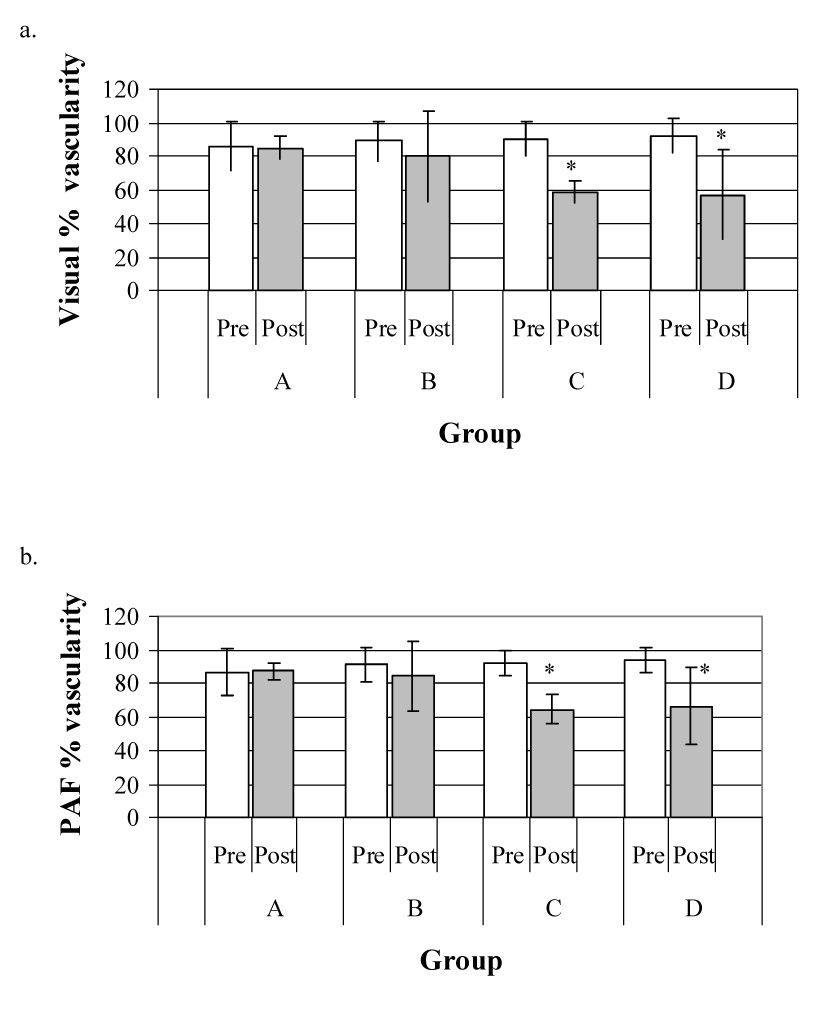

The murine melanoma was clearly visible in the B-mode images as it was uniformly hypoechoic to the contiguous tissues and had distinct borders (Fig 1, Fig 2). Peri-tumor edema (Figs. 2c and d) was observed as a subcutaneous hypoechoic region adjacent to the tumor border in 1 mouse in Group C and 2 mice in Group D – an overall incidence of 30% in tumors insonated following a power Doppler study. In the visual estimation of tumor vascularity, obtained in the contrast-enhanced power Doppler images from the display monitor on the ultrasound machine, there was no significant change in tumor perfusion in the control group (Group A; Fig 3a) or in those mice where no pre-insonation contrast-enhanced power Doppler study was performed (Group B). There were, however, statistically significant reductions in tumor vascularity when the tumor was insonated 15 (Group C; p = 0.0004) and 60 min (Group D; p = 0.02) after the microbubbles injected for the pre-treatment power Doppler study were no longer detectable in the ultrasound image (Fig. 3a). For PAF and CWFA, analysis of the digitized power Doppler images also showed that there was no change in the perfusion of the tumor in either the sham-treated tumors (Group A; Figs. 3b, c) or the tumors treated without a pre-insonation injection of microbubbles (Group B). Again, statistically significant reductions in perfusion were found in tumors insonated following a contrast-enhanced power Doppler study (PAF - Group C: p = 0.002; Group D: p = 0.03; Fig. 3b, and CWFA - Group C: p = 0.004; Group D: p = 0.005; Fig. 3c).

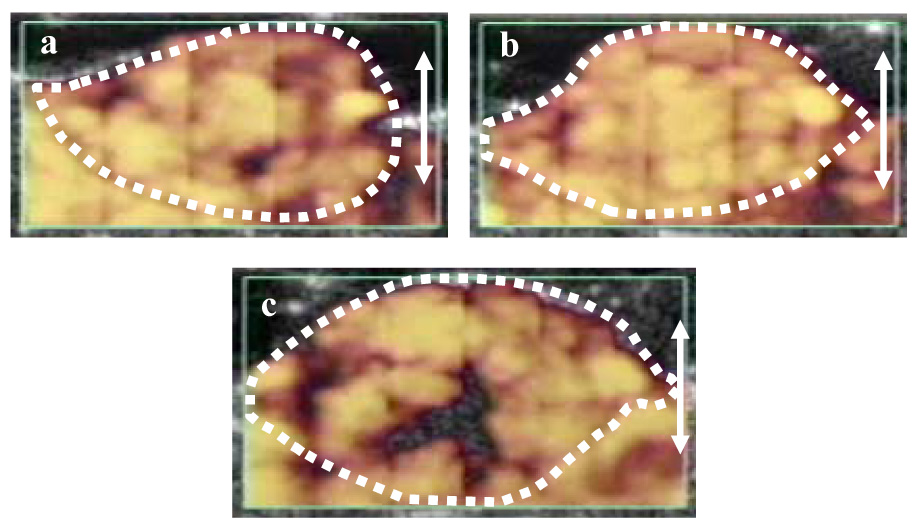

Fig. 1.

Power Doppler ultrasound images (group A, mouse A2R) of a melanoma, following the intravenous injection of an ultrasound contrast agent, prior to (a) and following (b) sham insonation. The double ended arrow represents a 1 cm scale. The green box is the region from which Doppler information was acquired, and the boundaries of the neoplasm, traced in white from the corresponding B-mode image, have been copied to these images. In both images, the tumor and the contiguous normal tissues are almost fully perfused. A similar almost full perfusion of the melanoma and adjacent normal tissues is also present in a tumor (c) insonated with physiotherapy ultrasound without the prior injection of a contrast agent (Group B, mouse E2R).

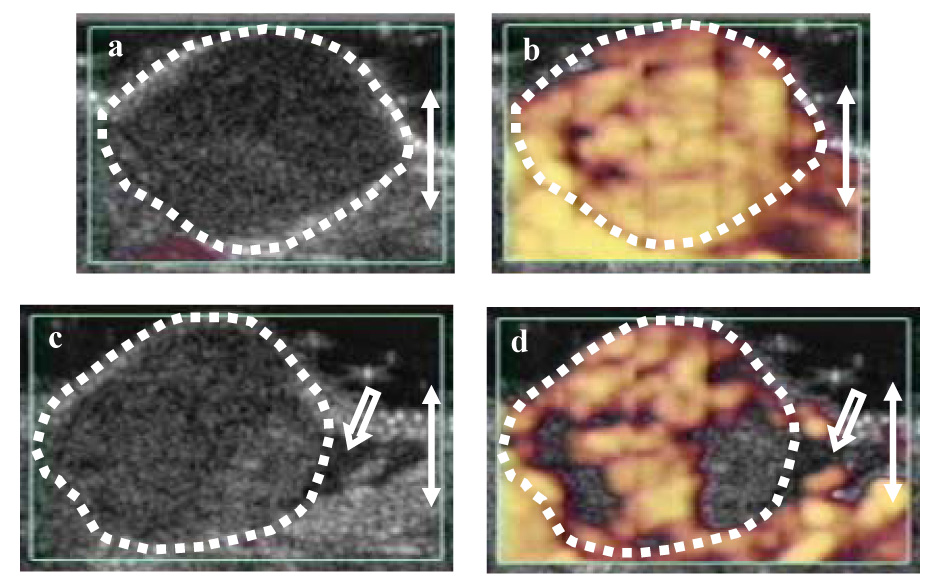

Fig. 2.

B-mode and power Doppler ultrasound images following the intravenous injection of an ultrasound contrast agent (Group C, mouse ILIR) prior to (a and b) and following treatment (c and d) with physiotherapy ultrasound. In the initial B-mode image (a) the melanoma is hypoechoic to the surrounding tissues and its distinct borders are outlined with white dots. Following the injection of the contrast agent, the initial power Doppler image shows that the tumor and the contiguous tissues are almost fully perfused (b). 15 min after the contrast microbubbles were no longer detectable in the initial power Doppler image, the tumor was insonated for 3 min with physiotherapy ultrasound. In the post-insonation B-mode image (c), the tumor has a patchy increase in echogenicity and hypoechoic peri-tumor edema is present (arrow). Reduced tumor perfusion is demonstrated in the post-insonation power Doppler image (d) and the peri-tumor edema is again seen (arrow); the perfusion of the normal tissues is unchanged. The observations suggest that the contrast agent played a role in the antivascular effect of physiotherapy ultrasound.

Fig. 3.

Effect of insonation on vascular perfusion assessed by power Doppler imaging: (a) represents visual estimation of tumor vascularity, (b) represents measurement of percentage area of flow (PAF) and (c) represents measurement of color-weighted flow area (CWFA).

In each figure, the hatched blocks represent the mean size of the vascular area before insonation and the open blocks that after treatment; the bars represent the standard deviation of the mean. Regardless of the method of analysis, there was no significant change in tumor vascularity in either the sham-treated control group (A) or in tumors that were insonated without an initial contrast-enhanced power Doppler study (Group B). There were, however, significant reductions in tumor vascularity in tumors insonated 15 (Group C) or 60 min (Group D) after the contrast microbubbles were no longer detectable in the initial power Doppler images. It appears that the ultrasound contrast agent had a role in the observed antivascular effect of physiotherapy ultrasound on the tumor neovasculature.

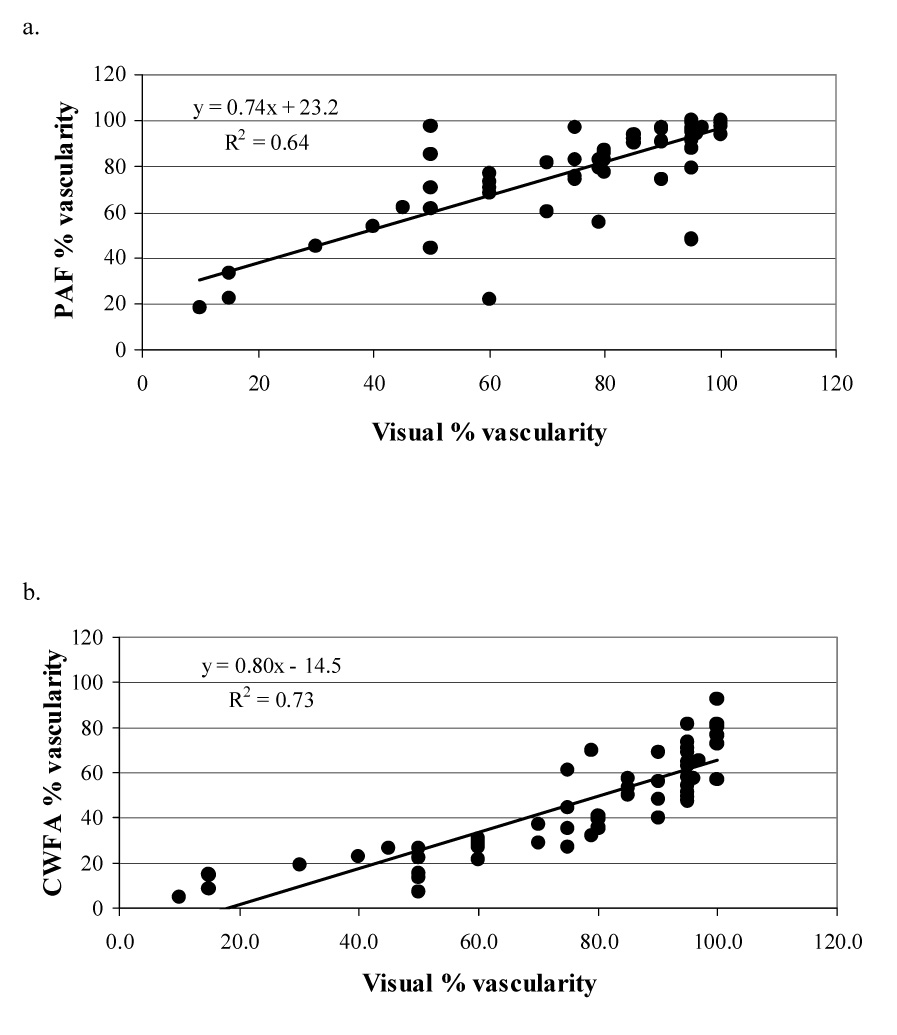

In comparing the methods of analyzing the contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations of tumor vascularity across all tumors, a linear regression analysis demonstrated a correlation (R2 = 0.64) between visual assessment and PAF (Fig. 4a) and also a correlation (R2 = 0.73) between visual assessment and CWFA (Fig 4b).

Fig. 4.

Comparison of visual assessment of tumor vascularity with quantitative measures of vascularity: (a) percentage area of flow (PAF) and (b)color-weighted flow area (CWFA). A correlation (R2) of 0.64–0.73 indicated a good agrrement between qualitative and quantitative assessment of tumor vascularity.

Histology

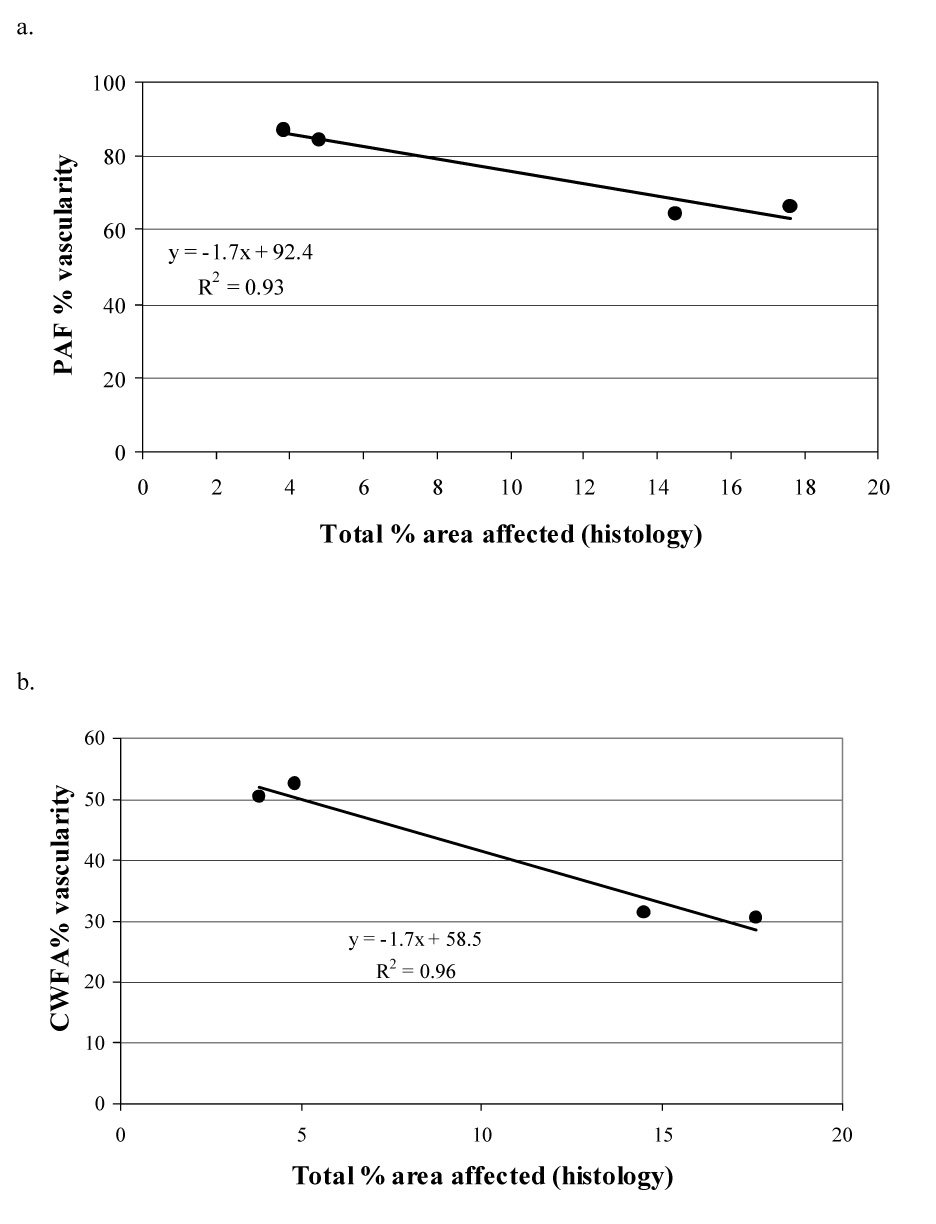

The tumors of the control mice (Group A) and those insonated, without the prior injection of microbubbles for a power Doppler study (Group B), had a similar histological appearance, and only minor areas of each tumor demonstrated histologic change (Table 1; Fig. 5, Fig. 6). In the tumors insonated 15 min (Group C) or 60 min (Group D) after the microbubbles were no longer detected in the power Doppler images, the predominant histologic findings were an increase in the incidence of dilated capillaries and hemorrhage (Table 1; Fig. 7, Fig. 8). In these tumors, there were trends for increases in both the total percentage area of the neoplasm affected by histologic change and the incidence of an individual histologic change, however, the observed increases were not statistically significant (Table 1). The incidence of intercellular fluid in the melanomas across all groups of mice was similar and mild (Table 1). Peri-tumor edema was also present – it was mild to moderate in all animals apart from three of the treated tumors (1 mouse in Group C and 2 mice in Group D) where it completely surrounded the neoplasm. In these latter tumors the edema was detectable in the ultrasound images. Pre-existing structures enveloped by the neoplasm were seen in each tumor - they were normal, apart from occasional nerves invaded by neoplastic cells, and were unaffected by the insonation (Fig. 8). Although there were noticeable variations in the qualitative assessments of the individual histologic changes (Table 1), linear regression analyses showed significant correlations between the total % area of histologic change and the PAF (R2 = 0.93; Fig 9a) and CWFA (R2 = 0.96 ; Fig 9b) assessments of tumor vascularity. These correlations between the US parameters and histology held only when the data was pooled for the various treatment groups. In the subjective analysis of each histologic slide there were variations between animals in the % area affected by histologic change. As a consequence, the correlative pattern was masked when individual tumors were plotted. Averaging by group had the effect of reducing the noise in the data.

Table 1.

Summary of histologic changes in murine melanomas.

| Group | Percent area affected (mean ± SD) | Intercellular fluid (score = 0–3) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total area affected | Dilation | Hemorrhage | Necrosis | Pseudocyst | ||

| A | 3.9 ± 9.1 | 3.3 ± 8.2 | 0.6 ± 1.2 | ND | 0.4 ± 1.0 | 0.8 ± 0.4 |

| B | 4.8 ± 7.4 | 4.3 ± 6.7 | 2.9 ± 4.2 | 3.7 ± 5.9 | 0.2 ± 0.4 | 0.4 ± 0.5 |

| C | 14.5 ± 12.6 | 11.3 ± 12.2 | 2.8 ± 2.3 | 0.3 ± 0.7 | 2.5 ± 5.6 | 0.5 ± 0.7 |

| D | 17.6 ± 29.8 | 16.9 ± 30.0 | 5.8 ± 9.4 | ND | 0.2 ± 0.5 | 1.0 ± 0.4 |

* = full details of how the measurements were made have been given previously (Bunte et al. 2006); Group A = control tumors; Group B = tumors insonated without prior injection of microbubble contrast agent; Group C = tumors insonated 15 min after contrast microbubbles no longer detectable in initial power Doppler study; Group D = tumors insonated 60 min after contrast microbubbles no longer detectable in initial power Doppler study; ND = not detected

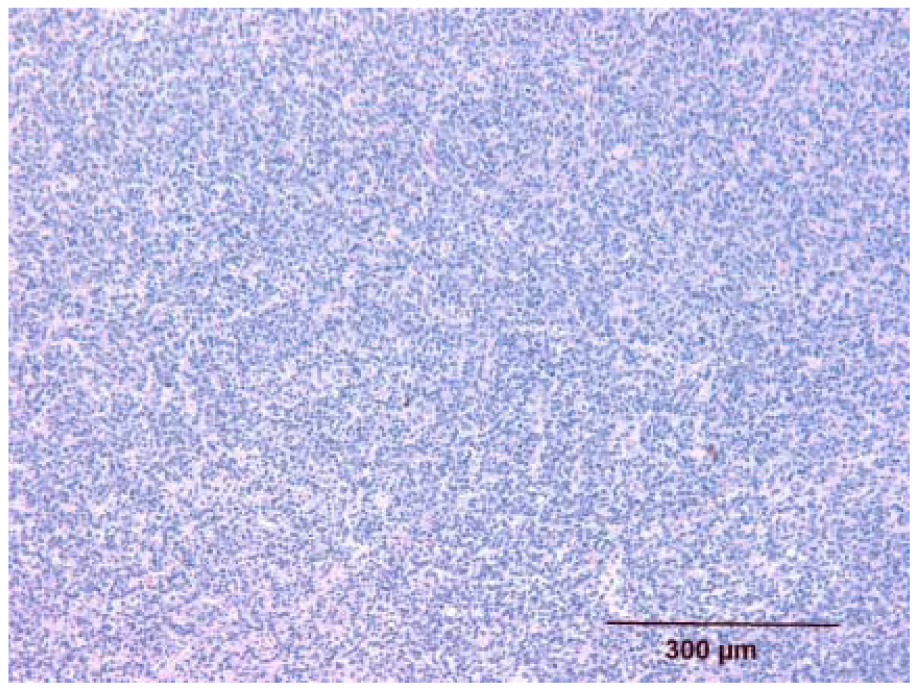

Fig. 5.

Histologic appearance of untreated melanoma (group A, mouse E1L). The melanoma is highly cellular and compact. It is characterized by spindle shaped cells arranged in a pattern of short, often interlacing, streams or bundles.

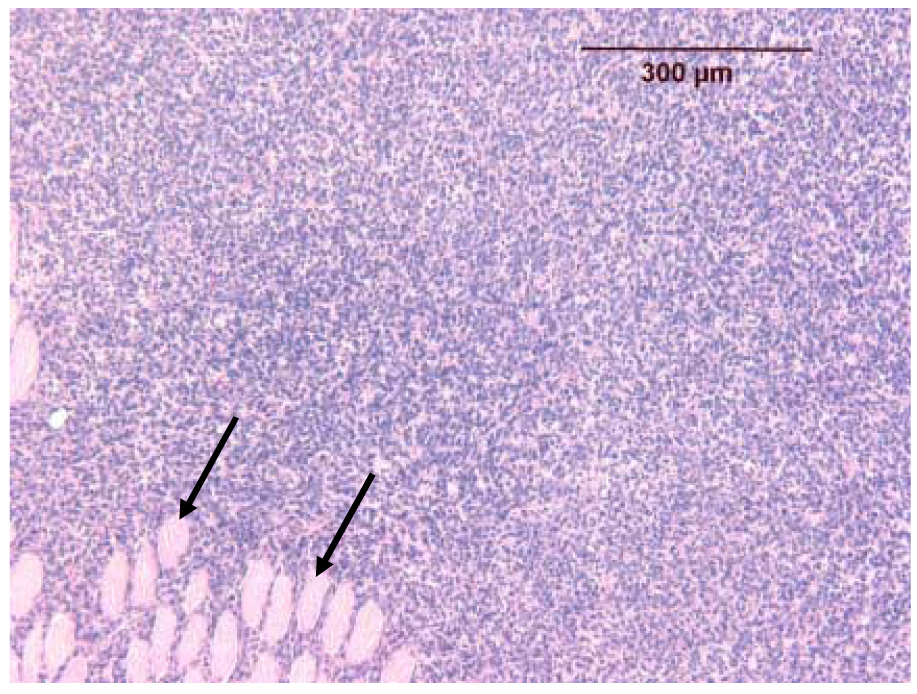

Fig. 6.

Histologic appearance of a melanoma insonated without a prior contrast-enhanced power Doppler study (group B, mouse A1L). The melanoma is identical to those found in the control group (Fig. 6). Note the pre-existing normal fibers of skeletal muscle (unaffected by the insonation) enveloped by the growing neoplasm and separated by infiltrating neoplastic melanocytes (two arrows).

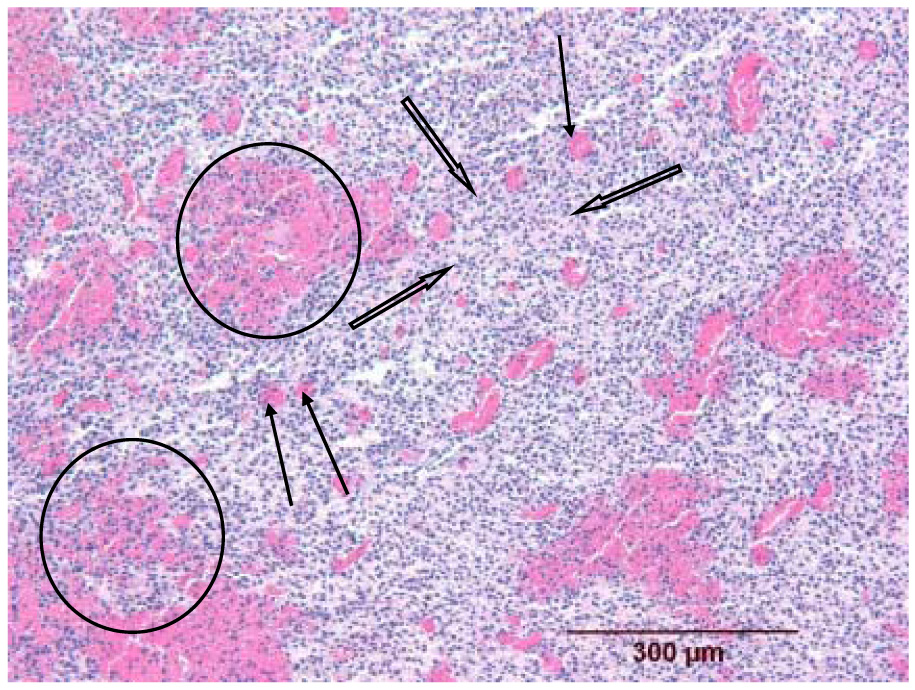

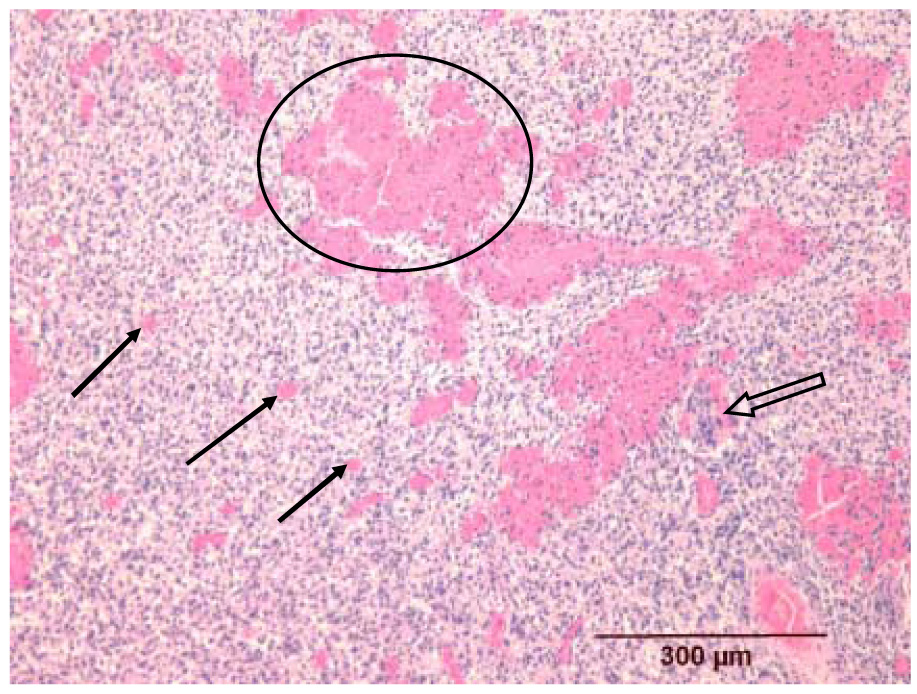

Fig. 7.

Histologic appearance of a melanoma insonated 15 min after contrast microbubbles were no longer detectable in the power Doppler image (group C, mouse C1L). The melanoma shows marked dilation of the capillary bed (three thin arrows), often with surrounding hemorrhage into the neoplastic tissue leading to separation of the neoplastic cells (two circled areas). The decreased compactness of the cells in other regions is related to intercellular edema (three thick arrows).

Fig. 8.

Histologic appearance of a melanoma insonated 60 min after contrast microbubbles were no longer detectable in the power Doppler image (group D, mouse B1L). The dilation of the capillary bed (three small arrows), with associated hemorrhage (circled area), is identical to that seen in Fig. 8. Note also the pre-existing nerve fiber that is unaffected by the insonation but is infiltrated with neoplastic cells (open arrow).

Fig. 9.

Linear regression analyses (across all tumors) comparing the total % area in which tissue structure had altered and the change in tumor vascularity determined by contrast enhanced power Doppler images. The four black dots represent data from each of the four groups of mice (groups A, B, C and D from left to right). There is high correlation between total % histologic change and the ultrasound measurements of tumor vascularity (PAF and CWFA).

DISCUSSION

Various methods are available for analyzing the changes in perfusion that occur in contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations of tissues; CWFA has been previously described (Sehgal et al. 2000, 2001). In our animal model investigating the antivascular effect of physiotherapy ultrasound, the changes in perfusion following insonation of a subcutaneous melanoma were large enough to be visually estimated from the display monitor on the ultrasound machine. Our analyses showed that such visual estimations of the % vascular area in the neoplasm were in agreement with the more precise assessments of digitized images made by PAF (a measure of the size of the perfused area of the neoplasm) and CWFA (a measure of the volume of a microbubble-containing contrast agent flowing through the unit volume of the tumor). We also found that estimates of tumor vascularity measured using CWFA fully correlated with those obtained from cumulative histogram areas used in our previous studies (Wood et al. 2005; Bunte et al. 2006). Because of this relationship between the two parameters and because it was easier to interpret, we decided to present our data analysis in this paper using the CWFA method.

In this study we used Definity (rather than Optison) as the ultrasound contrast agent and a longer time interval between imaging and sonication than in our previous studies (Wood et al. 2005; Bunte et al. 2006). Despite these differences, an antivascular effect of physiotherapy ultrasound on tumor neovasculature was again clearly and consistently demonstrated - the findings continued a pattern seen in our previous observations. The antivascular effect was, however, dependent upon a pre-insonation injection of a microbubble-containing ultrasound contrast agent. As previously (Bunte et al. 2006), there was a high correlation between the reduction in tumor vascularity (assessed by PAF and CWFA) and the total % area of each tumor affected by histologic change. The predominant acute affect of insonation was again dilation of the tumor capillaries and hemorrhage. It appeared that the mild intercellular fluid across all tumors was a characteristic feature of these murine melanomas and its incidence was not related to the presence or absence of insonation. Also as found previously, pre-existing structures that were enveloped by the growing neoplasm were unaffected by the insonation (Wood et al. 2005, Bunte et al 2006). In this tumor model, it appeared that mild peri-tumor edema, undetected in B-mode ultrasound images, was a characteristic histologic finding in the growing, uninsonated neoplasm. Peri-tumor edema was detected in the B-mode ultrasound images of about a third of mice insonated 15 and 60 min after the intravenous injection of contrast agent microbubbles and was related to the treatment with physiotherapy ultrasound. The reduction in both vascularity and the total % area affected histologically was less than that found for a similar treatment time in our earlier study (Bunte et al. 2006). The reduced effects of insonation may have been related to a number of factors including: a reduced intensity of the physiotherapy ultrasound beam (from 2.3 to 1.7 W cm−2) a change in the type of microbubble contrast agent used for the power Doppler imaging (from Optison to Definity) and a reduction in the volume of contrast agent injected intravenously for each power Doppler study (from 0.1mL to 0.02mL). The present study explored the post-insonation histologic changes in tumor. Future studies could investigate whether any histologic changes occurred in the normal tissues surrounding the tumor. The contrast enhanced power Doppler observations demonstrated, however, that the vascularity of the peritumor tissues was maintained following tumor therapy.

In this in vivo study, the pre-insonation intravenous injection of a microbubble-containing ultrasound contrast agent played an essential role in the observed antivascular action of physiotherapy ultrasound. The underlying etiology of the interaction between the physiotherapy ultrasound beam, the microbubble-containing contrast agent and the tumor neovasculature is unknown. It is likely to be complex and multifactorial.

The presence of inertial cavitation, in which a microbubble of the contrast agent expands and then collapses in the presence of insonation, leading to an observed effect on tissues, may explain (at least in part) the observed antivascular actions in the murine melanomas. It was hypothesized that the gas released, following the rupture of the bubble of contrast agent, may lead to the formation of secondary smaller bubbles which interacted with the ultrasound beam and caused the cellular bioeffects (Brayman and Miller, 1997; Dalecki et al. 1997; Kameav et al 2004). It has also been suggested that air-containing fragments of the shells of the ruptured bubbles could be involved (Dalecki et al. 1997). In our study there was a 15 or 60 min gap between the time when microbubbles of contrast agent were no longer detectable in the power Doppler image of the tumor and the tumor’s insonation. Tu et al. (2006) have shown that the half life (t1/2) of inertial cavitation activity increased with the pressure amplitude (peak rarification) of the ultrasound wave - i.e. at higher pressure amplitudes inertial cavitation activity lasts longer. They reported that at a pressure amplitude of 1 MPa, t1/2 is about 100s. If Tu et al. (2006) results are extrapolated to our study, conducted at a considerably lower intensity of 1.7 W cm−2 (0.2 MPa), the half life of inertial cavitation is likely to be much <100s. This suggests that inertial cavitation may not have been a dominant factor in producing the observed antivascular effects, although it cannot be completely ruled out.

Heat is another bioeffect that may be important in considering the etiology of the antivascular effect. With a 2.3 W cm−2 ultrasound beam, we observed in vitro in excised tissue (in the absence of an ultrasound contrast agent) that the average temperature increased by 3.8 °C over the duration of each 1 min period of insonation (Wood et al. 2005). In the current in vivo study of murine melanomas, we assumed that heating of the tumor also occurred during its insonation, but no bioeffects were observed unless there had been a pre-insonation injection of an ultrasound contrast agent. Thus, it is possible that any bioeffect-producing actions of heat on the tumor and its neovasculature resulted from upon a direct interaction between the physiotherapy ultrasound beam and the ultrasound contrast agent. Using a phantom with a peristaltic pump, Razanksy et al. (2006) found that during insonations with a physiotherapy ultrasound beam (3.2 MHz, continuous wave, 1.1 W cm−2) significant temperature increases (12.5 to 21°C) occurred when a microbubble contrast agent (Optison at 10 to 100 times normal in vivo concentrations) was added to the system. It was concluded that during insonation in the presence of a contrast agent there was increased dissipation of acoustic power to heat due to radial pulsation of shell-encapsulated microbubbles; it was noted that the shell viscosity was the major damping mechanism for the heat conversion. In a theoretical paper, Stride and Saffari (2004) compared the extent of local heating (during insonation) that could occur adjacent to both free gas bubbles and the encapsulated bubbles of an ultrasound contrast agent. They concluded that the conduction of heat from the shell of an intact contrast microbubble into the surrounding fluid could lead to a bioeffect. In the current study, perhaps fragments of the shell of a burst microbubble of contrast agent could have provided a site for a similar interaction with the ultrasound beam.

Physiotherapy insonation in the presence of circulating contrast agents could also lead to effects on the endothelial cells lining the tumor capillaries. Hwang et al. (2006) reported damage to normal vascular endothelial cells in the rabbit’s ear, following sonication at HIFU intensities in the presence of circulating microbubbles. They hypothesized that, as there was no evidence of histologic change in the perivascular tissue, the changes were related to cavitation rather than a thermal effect. As dilation of the tumor capillaries was the most prominent post-insonation finding in our tumors, the endothelial synthesis of nitric oxide, a vasodilator, could also have occurred. Nitric oxide production has been noted following the insonation of endothelial cells growing in tissue culture (Altland et al. 2004; Hsu and Huang 2004).

Ultrasound is a unique form of energy in itself. There is not a single or simple explanation for the observed interactions between the physiotherapy ultrasound beam and the circulating microbubble-containing contrast agent which lead to the antivascular action in a murine neoplasm. It should not be assumed that only a single bioeffect is present at a given time during an insonation of tissues (Baker et al. 2001; Wood et al. 2005; Bunte et al. 2006). The observed bioeffects may be thermal in origin, and could possibly be measured by concurrent magnetic resonance imaging observations (McDannold et al. 2006). However, other non-thermal mechanisms including cavitation, radiation pressure and other non-linear effects may also be occurring. Future studies could be aimed at investigating whether the antivascular effects of physiotherapy ultrasound occur following the intravenous injection of the phospholipid shell of the contrast agent alone (without any intact microbubbles or smaller secondary bubbles). Our findings also raise the possibility of insonating tumors in the presence of other intravenously injected synthesized absorbing media that could mimic the actions of the phosholipid remnants of the ultrasound contrast agent microbubble.

Acknowledgments

this work was supported by NIH grant no. EB001713.

APPENDIX A

Relationship between cumulative histogram area and CWFA

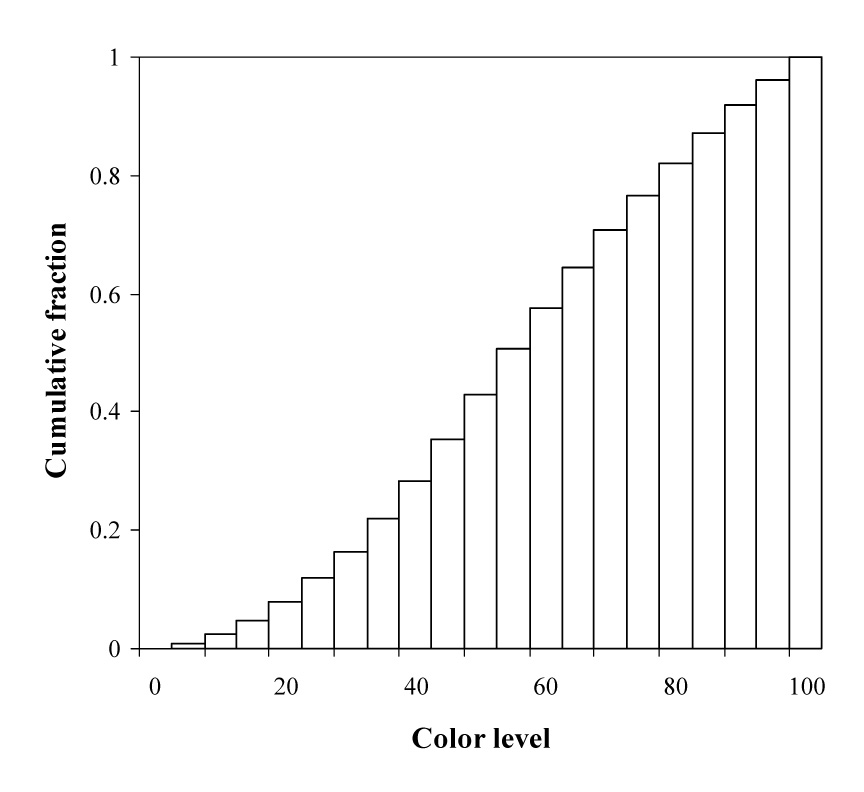

In our previous study (Wood et al. 2005) we demonstrated that a cumulative histogram of the power Doppler pixels in the tumor partitioned contrast agent flow to the tumor into two components. The component represented by the area under the cumulative curve, As, corresponds to the avascular region of the tumor that does not receive contrast agent. On the other hand, the component represented by the area above the cumulative histogram curve (100 − As) measures the amount of contrast agent flowing through the tumor and represents the vascular component. The approach of dividing contrast flow into two components of vascular and avascular regions using the histogram while simple mathematically is not intuitive. In the description that follows we demonstrate that the same information can be obtained by measuring the spatial average of contrast agent flowing through the tumor region as determined by color–weighed fractional area (CWFA).

If the color level, CL, of contrast-enhanced Doppler image is distributed in 100 equal bins, the cumulative histogram of the pixels in the tumor can be represented by Fig. 10. In Fig.10 the vertical axis gives the fractional count of colored pixels for that color bin plus all the bins for smaller values.

Fig. 10.

Schema of cumulative histogram area analysis of contrast-enhanced power Doppler images.

If the sum-count for the ith color level bin is represented by the symbol Si, then area under the cumulative curve As is described by the equation

| A1 |

For bin size of 1, Equation 1 takes the form,

| A2 |

If fz represents the number of colored pixels in the zth bin then Sz = Sz−1 + fz and equation A2 can be rewritten as,

| A3 |

Repeating the Sz recursively and generalizing, yields

| A4 |

| A5 |

| A6 |

Sum of all fractions is equal to one and the second term in A6 is equal to CWFA

| A7 |

For 100 color bins in the histogram,

| A8 |

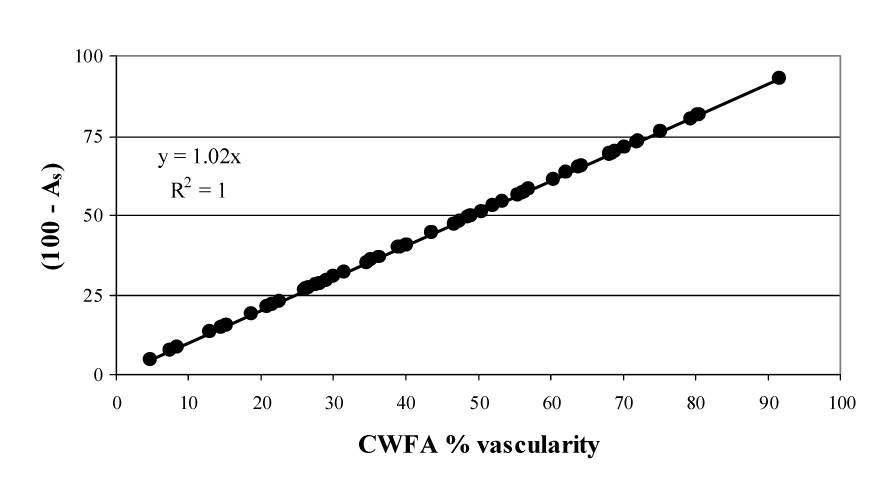

According to equation A8 CWFA, which represents amount of contrast flowing per unit area of the curve, is equal to the area over the cumulative histogram curve (100 − As).

In this study we measured CWFA and (100 − As) for all the mice. The data is shown in Fig. 11. The correlation of R2 = 1 and slope 1 indicates CWFA and vascularity measured by cumulative histogram area (100 − As)are equivalent. Measurement of either parameter can be used to assess tumor vascularity.

Fig. 11.

Linear regression analysis (across all tumors) comparing the color-weighted flow area (CWFA) and cumulative histogram area methods of analyzing contrast-enhanced power Doppler observations of tumor vascularity. There is a full correlation (R2 = 1.0) between the two measurements of tumor vascularity.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Altland OD, Dalecki D, Suchkova VN, Francis CW. Low-intensity ultrasound increases endothelial cell nitric oxide synthase activity and nitric oxide synthesis. J Thrombosis Haemostasis. 2004;2:637–643. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2004.00655.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker KG, Robertson VJ, Duck FA. A review of therapeutic ultrasound: biophysical effects. Phys Ther. 2001;81:1351–1358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayman AA, Miller MW. Acoustic cavitation nuclei survive the apparent ultrasonic destruction of albunex microspheres. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1997;23:793–796. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00008-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunte RM, Ansaloni S, Sehgal CM, Lee WM-F, Wood AKW. Histpathological observations of the antivascular effects of physiotherapy ultrasound on a murine neoplasm. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:453–461. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Conway EM. Growing better blood vessels. Nat Biotechnol. 2001;19:1019–1020. doi: 10.1038/nbt1101-1019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalecki D, Raeman CH, Child SZ, Penney DP, Carstensen EL. Remnants of albunex nucleate acoustic cavitation. Ultrasound Med Biol. 1997;23:1405–1412. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(97)00142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkman J. Angiogenesis. In: Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Longo DL, Jameson JL, editors. Harrison’s textbook of internal medicine. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 517–530. [Google Scholar]

- Haroon ZA, Peters KG, Greenberg CS, Dewhirst MW. Angiogenesis and oxygen transport in solid tumors. In: Teicher BA, editor. Antiangiogenic agents in cancer therapy. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 1999. pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hsu S-h, Huang T-b. Bioeffect of ultrasound on endothelial cells in vitro. Biomol Eng. 2004;21:99–104. doi: 10.1016/j.bioeng.2004.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang JH, Tu J, Brayman AA, Matula TJ, Crum LA. Correlation between inertial cavitation dose and endothelial cell damage in vivo. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1611–1619. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jain RK. Tumor angiogenesis and accessibility: role of vascular endothelial growth factor. Semin Oncol. 2002;29 Suppl 16:3–9. doi: 10.1053/sonc.2002.37265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamaev PP, Hutcheson JD, Wilson ML, Prausnitz MR. Quantification of Optison bubble size and lifetime during sonication dominant role of secondary cavitation bubbles causing acoustic bioeffects. J Acoust Soc Am. 2004;115:1818–1825. doi: 10.1121/1.1624073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDannold NJ, Vykhodtseva NI, Hynynen K. Microbubble contrast agent with focused ultrasound to create brain lesions at low power levels MR imaging and histologic study in rabbits. Radiology. 2006;241:95–106. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2411051170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razansky D, Einziger PD, Adam DR. Enhanced heat deposition using ultrasound contrast agent – modelling and experimental observations. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2006;53:137–147. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2006.1588399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal CM, Arger PH, Rowling SE, Conant EF, Reynolds C, Patton JA. Quantitative vascularity of breast masses by Doppler imaging: regional variations and diagnostic implications. J Ultrasound Med. 2000;19:427–440. doi: 10.7863/jum.2000.19.7.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sehgal CM, Arger PH, Silver AC, Patton JA, Saunders HM, Bhattacharyya A, Bell CP. Renal blood flow changes induced with endothelin-1 and fenoldopam mesylate at quantitative Doppler US: initial results in a canine study. Radiology. 2001;219:419–426. doi: 10.1148/radiology.219.2.r01ma13419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stride E, Saffari N. The potential for thermal damage posed by microbubble contrast agents. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:907–913. doi: 10.1016/j.ultras.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran BC, Seo J, Hall TL, Fowlkes JB, Cain CA. Microbubble enhanced cavitation for noninvasive ultrasound surgery. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2003;50:1296–1304. doi: 10.1109/tuffc.2003.1244746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tu J, Hwang JH, Matula TJ, Brayman AA, Crum LA. Intravascular inertial cavitation activity detection and quantification in vivo with optison. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2006;32:1601–1609. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2006.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood AKW, Ansaloni S, Ziemer LS, Ziemer LS, Lee WM, Feldman MD, Sehgal CM. The antivascular action of physiotherapy ultrasound on murine tumours. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2005;31:1403–1410. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Chen W-Z, Bai JJ, Zou JZ, Wang ZL, Zhu H, Wang ZB. Pathological changes in human malignant carcinoma treated with high intensity focused ultrasound. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2001;27:1099–1106. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00389-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu F, Chen W-Z, Bai J, Zou JZ, Wang ZL, Zhu H, Wang ZB. Tumor vessel destruction resulting from high-intensity focused ultrasound in patients with solid malignancies. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2002;28:535–542. doi: 10.1016/s0301-5629(01)00515-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu T, Wang G, Hu K, Ma P, Bai J, Wang Z. A microbubble agent improves the therapeutic efficiency of high intensity focused ultrasound: a rabbit kidney study. Urol Res. 2004;32:14–19. doi: 10.1007/s00240-003-0362-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]