Summary

Background

Organ transplant recipients (OTR) are at high risk of developing non-melanoma skin cancer and premalignant epidermal dysplasia (carcinoma in situ/Bowen’s disease and actinic keratoses). Epidermal dysplasia is often widespread and there are few comparative studies of available treatments.

Objectives

To compare topical methylaminolaevulinate (MAL) photodynamic therapy (PDT) with topical 5% fluorouracil (5-FU) cream in the treatment of post-transplant epidermal dysplasia.

Methods

Eight OTRs with epidermal dysplasia were recruited to an open-label, single-centre, randomized, intrapatient comparative study. Treatment with two cycles of topical MAL PDT 1 week apart was randomly assigned to one area of epidermal dysplasia, and 5-FU cream was applied twice daily for 3 weeks to a clinically and histologically comparable area. Patients were reviewed at 1, 3 and 6 months after treatment. The main outcome measures were complete resolution rate (CRR), overall reduction in lesional area, treatment-associated pain and erythema, cosmetic outcome and global patient preference.

Results

At all time points evaluated after completion of treatment, PDT was more effective than 5-FU in achieving complete resolution: eight of nine lesional areas cleared with PDT (CRR 89%, 95% CI: 0·52-0·99), compared with one of nine lesional areas treated with 5-FU (CRR 11%, 95% CI: 0·003-0·48) (P = 0·02). The mean lesional area reduction was also proportionately greater with PDT than with 5-FU (100% vs. 79% respectively). Cosmetic outcome and patient preference were also superior in the PDT-treated group.

Conclusions

Compared with topical 5-FU, MAL PDT was a more effective and cosmetically acceptable treatment for epidermal dysplasia in OTRs and was preferred by patients. Further studies are now required to confirm these results and to examine the effect of treating epidermal dysplasia with PDT on subsequent development of squamous cell carcinoma in this high risk population.

Keywords: actinic keratoses, carcinoma in situ, 5-fluorouracil, methylaminolaevulinate, organ transplant recipient, topical photodynamic therapy

Organ transplant recipients (OTR) on chronic immunosuppressive therapy have a high risk of developing cancer,1 of which skin cancers are the most common.2 Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (SCCs) are a particular problem, with an incidence 65-250 times greater than that of age-matched controls.2-5 Many patients develop multiple skin tumours, and the incidence increases with the duration of immunosuppressive therapy.2,4,6-8 Premalignant epidermal dysplastic lesions such as actinic keratoses (AK) and carcinoma in situ (CIS, Bowen’s disease) are also more common, and affect up to 40% of OTRs by 5 years after transplantation.9,10 Such epidermal dysplasia is frequently extensive, and multiple independent premalignant lesions may become clinically and histologically confluent, constituting large areas of field carcinogenesis.9 In addition, these lesions probably also have a higher rate of transformation to invasive SCCs than in the immunocompetent population.11 Post-transplant SCCs are often multiple, may be highly aggressive and represent a significant cause of morbidity in this group of patients.2 Early identification and vigorous treatment of premalignant cutaneous lesions in OTRs is therefore desirable, although the effect of this on reducing progression to SCC is not yet established.

A number of modalities exist for treatment of post-transplant epidermal dysplasia, but there are few systematic, comparative studies of their efficacy and adverse effects. Surgery and cryotherapy are effective but may result in scarring and poor cosmesis, which is of particular importance given that the majority of lesions arise on sunexposed and therefore visible sites. Although the topical immune response modifier imiquimod has received increasing attention,12 it is not licensed in the U.K. for the treatment of epidermal dysplasia. The topical chemotherapeutic agent 5% fluorouracil (5-FU) is perhaps the most widely used topical therapy for extensive epidermal dysplasia. It is thought to work through inhibition of thymidylate synthetase and the consequent inhibition of DNA synthesis and may also interfere with RNA 22 formation and function.13 Both agents typically cause cutaneous inflammation which may be extreme and occasionally intolerable if large areas are being treated. Topical photodynamic therapy (PDT), in which a photosensitizer is activated by light to produce reactive oxygen species that selectively destroy target cells, is increasingly used to treat epidermal dysplasia. 5-Aminolaevulinic acid (5-ALA) and a newer methyl ester of 5-ALA, methyl 5-aminolaevulinate (MAL) (Metvix, Photocure ASA, Oslo, Norway) are used as topical photosensitizer prodrugs. MAL may confer advantages over 5-ALA in terms of improved skin penetration secondary to its greater lipophilicity,14-16 higher selectivity for neoplastic cells17 and possibly reduced pain intensity during illumination.18,19 5-ALA and MAL accumulate in tumour cells and enter the biosynthetic haem pathway, resulting in the accumulation of the photosensitizer protoporphyrin IX which preferentially localizes to membranes. On photoactivation of protoporphyrin IX, the absorbed energy is transferred to molecular oxygen to generate numerous reactive oxygen species including singlet oxygen. Subsequent oxidative damage to membrane lipids results in loss of membrane integrity and ultimately in cell death. Topical PDT may offer potential benefits over existing treatments because multiple and/or large skin lesions, which are a particular problem in OTRs, may be treated effectively with excellent cosmesis.20

To assess the role of PDT in treating post-transplant epidermal dysplasia, we compared topical 5-FU with topical MAL PDT in an open-label, single-centre, randomized, intrapatient comparative study.

Methods

Patients

The trial was conducted during the period May 2004 to August 2005 in the Department of Dermatology at the Royal London Hospital. All participating patients were provided with verbal and written information regarding this study and informed written consent was obtained. Ethical approval was obtained from the East London and City Local Research Ethics Committee.

Eight OTRs on chronic immunosuppressive therapy were recruited from a dedicated dermatology clinic for OTRs at The Royal London Hospital. All had a history of epidermal dysplasia (multiple AKs and/or CIS). In order to be included, a patient was required to have two clinically and histologically equivalent areas of epidermal dysplasia, each approximately the same size, on anatomically separate sites (Table 1). Diagnosis was confirmed histologically in each case before treatment. A ‘washout’ period of at least 8 weeks before entry into the study was required, in which no lesion had been treated. Each patient was randomly assigned21 to apply topical 5-FU cream to one lesional area twice daily for 3 weeks and to receive topical PDT twice at a 1-week interval to the other lesional area. Treatment areas comprised either one individual lesion or multiple lesions. For treatment areas comprising multiple clinically distinct lesions, a single diagnostic biopsy was performed and all clinically similar lesions in that area were treated as for the histological diagnosis of the index lesion. Renal function was monitored routinely in each patient for the duration of the study.

Table 1.

Clinical details of organ transplant recipients participating in photodynamic therapy vs. 5-fluorouracil study and results summary

| Patient no. | Sex | Age | Type of transplant | IS regime | On acitretin? | Year of transplant | Years on IS therapy | Lesion for PDT treatment |

Response |

Lesion for 5FU treatment |

Response |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site | Diagnosis | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | Site | Diagnosis | 1 month | 3 months | 6 months | ||||||||

| 1 | M | 67 | Kidney | P,C | Yes | 1993 | 11 | R forehead | CIS | CR | CR | CR | L forehead | CIS | PR | PR | PR |

| R forearm | CIS | PR | PR | PR | L forearm | CIS | PR | PR | PR | ||||||||

| 2 | M | 46 | Kidney | P,C,M | Yes | 1990 | 14 | L hand (dorsum) | CIS | CR | CR | CR | R hand (dorsum) | CIS | PRa | PRa | PRa |

| 3 | M | 71 | Kidney | P,A | Yes | 1984 | 20 | R hand (dorsum) | AK | CR | CR | CR | L hand (dorsum) | AK | PR | PR | PR |

| 4 | F | 49 | Kidney | P,A | Yes | 1974 | 30 | R hand (dorsum) | AK | CR | CR | CR | L hand (dorsum) | AK | PR | CR | CR |

| 5 | M | 59 | Kidney | P,C,A | Yes | 1988 | 16 | R inferior forehead | CIS | CR | CR | CR | R superior forehead | CIS | PR | PR | PR |

| 6 | F | 58 | Kidney | C,A | No | 1983 | 21 | R buttock | CIS | CR | CR | CR | R posterior thigh | CIS | PRa | PRa | PRa |

| 7 | M | 59 | Kidney & liver | P,T | No | 1983 Kidney 1986 liver |

21 | R hand (dorsum) | AK | CR | CR | CR | L hand (dorsum) | AK | PR | PR | PR |

| 8 | M | 66 | Kidney | P,A | No | 1979 | 25 | L forearm | AK | CR | CR | CR | R forearm | AK | PR | PR | PR |

AK, actinic keratoses; CIS, carcinoma in situ; CR, complete response; IS, immunosuppressive therapy (P, prednisolone; C, ciclosporin; M, mycophenolate mofetil; A, azathioprine; T, tacrolimus); PR, partial response.

These lesions were classified as nonresponders (NR) when evaluated using the EORTC guidelines.

Topical photodynamic therapy with methyl 5-aminolaevulinate procedure

Crusted lesions randomized to receive topical PDT were gently abraded with a curette to remove excess thick surface scale. MAL cream (Metvix®, Photocure ASA, Oslo, Norway) 160 mg g−1 approximately 1 mm thick was applied to the area and covered with a semipermeable adhesive dressing, (Tegaderm®, 3M Health Care Ltd, Bracknell, U.K.). Three hours later the dressing was removed and the cream washed off with 0·9% normal saline before illumination with a non-coherent red light source (633 ± 15 nm; Paterson PDT Omnilux, Phototherapeutics Ltd, Altrincham, U.K.) with an irradiance of 80 mW cm−2, and a total dose of 75 J cm−2. The treatment was repeated 1 week later.

Application of topical 5-fluorouracil

Crusted lesions randomized to receive topical 5-FU were gently abraded as described above. 5-FU cream (Efudix®, Valeant Pharmaceuticals, Basingstoke, U.K.) was applied and massaged into lesional areas twice daily for 3 weeks as per manufacturer’s guidelines. Patients kept a daily record of treatment applied.

Recording of lesional response

All lesions were reviewed at 1, 3 and 6 months after completion of treatment. Outcomes were classified as either complete response (CR) or partial response (PR), where CR corresponded to complete clinical resolution of the treated lesion(s) and PR corresponded to partial clinical resolution of the treated lesion(s). This assessment was repeated using a definition of PR based upon the EORTC guidelines for the evaluation of tumour treatment response.22 On this basis, PR was defined as at least a 30% reduction in the surface area of the lesion after treatment. Lesions that failed to meet the criteria for PR were graded as nonresponders (NR). Assessments were not blinded. In addition to photographic mapping, the clinical margins of each lesional area were traced onto transparencies before treatment and at 1, 3 and 6 months after treatment and the surface area was calculated by overlaying on 1 mm squared graph paper.

Recording of pain, erythema and other local reactions

Patients kept a daily record of pain and erythema using a 4 point scale (0 = none, 1 = mild, 2 = moderate and 3 = severe). Any other local skin reactions such as pruritus, erosions, ulceration, crusting, skin infection and scarring were also documented.

Assessment of cosmetic outcome

At the 6-month assessment, both patient and clinician scored the cosmetic result as poor (extensive scarring, atrophy or induration), moderate (slight to moderate occurrence of scarring), good (no scarring, atrophy or induration, but moderate redness or pigmentation change compared with adjacent skin), or excellent (no scarring, atrophy or induration and no or slight occurrence of redness or pigmentation change compared with adjacent skin).

Global patient preference assessment

At the end of the study each patient was asked to specify which treatment method they preferred overall, taking into consideration all aspects of treatment including time involved, adverse effects, efficacy and cosmetic result.

Statistical analysis

Data was collated in an Excel spreadsheet and imported into Stata™ (StataCorp. 2003. Stata Statistical Software: Release 8.0., College Station, TX, U.S.A. Stata Corporation) for analysis. A difference between 5-FU and PDT at 6 months after treatment in terms of complete resolution rate (CRR) was assessed using McNemar’s exact method for paired proportions, and the associated 95% confidence interval calculated. We also tested for an association between response based upon EORTC guidelines (defined as CR, PR or NR) and treatment group, using ordered logistic regression with a robust measure of variance. This, essentially, performs a χ2 test for trend that also accounts for the pairing and jointly assesses the treatment effect on both CR and PR rates without loss of information. A difference between the treatments in terms of reduction in mean lesional area, after accounting for lesion area (mm2) at baseline, was assessed using multiple regression methods with lesion size (post-treatment) as the dependent variable and lesion size (pretreatment) and treatment (PDT or 5-FU) as explanatory (independent) variables in the model. Robust estimates of variance were used to adjust for pairing. The changes in pain and erythema scores over time and the overall cosmesis and patient preference scores were assessed informally using descriptive methods.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics

Six males and two females participated, with a mean age of 59 years (range 46-71). Seven patients were renal transplant recipients and one was a combined renal and liver transplant recipient. Details of immunosuppressive drug regimens are presented in Table 1. The mean duration of transplantation was 20 years (11-30 years). All eight patients were Fitzpatrick skin phototype 1 or 2.

Treatment and response

All eight patients completed treatment and 6-month follow up. Patient 5, assessed at 6 months, died shortly afterwards from unrelated causes. A total of 18 lesional areas were treated, comprising 10 CIS and eight AK. Nine lesional areas received topical PDT and the other nine received topical 5-FU (Table 1). The smallest lesional area treated was 39 mm2, whilst the largest was 5010 mm2. In Patient 1 two pairs of lesions were treated simultaneously, one pair on the forearms and the other on the forehead.

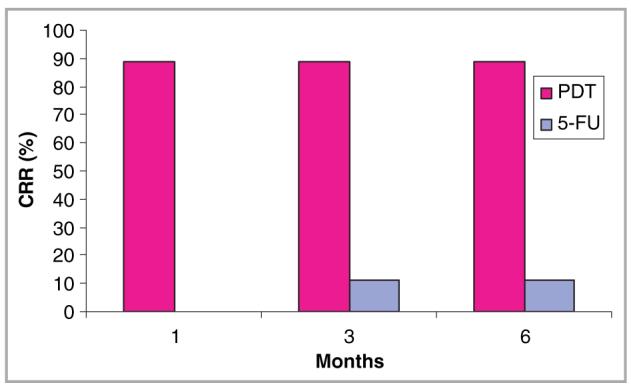

At 1-month follow up eight of the nine lesional areas treated with topical PDT had completely resolved, corresponding to a CRR of 89% (95% CI: 0·52-0·99), whereas treatment with topical 5-FU failed to achieve complete resolution in any of the nine lesional areas (Table 1 and Fig. 1). At 3-month follow up the CRR for PDT was unchanged, whilst for 5-FU it had improved to 11% (95% CI: 0·003-0·48), with complete resolution in one out of nine lesions (Patient 4) (Fig. 2). Following this, the CRR for both treatment groups remained unchanged. At 6 months after treatment, therefore, the difference between PDT and 5-FU with respect to CRR was 78% (95 CI: 0·40-1·00) (P = 0·02). When we used a definition of PR based upon the EORTC guidelines, two of the nine lesions treated with 5-FU which had been initially graded as PRs were reclassified as NR as they failed to show at least a 30% reduction in surface area after treatment. This resulted in a greater statistical significance between PDT and 5-FU in terms of response (P = 0·004).

Fig 1.

Complete resolution rate (CRR) for topical photodynamic therapy (PDT) and topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) at 1, 3 and 6 months of follow up.

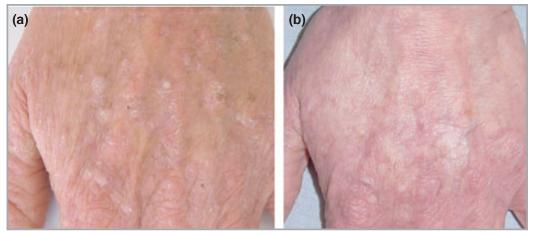

Fig 2.

(a) Actinic keratoses on dorsum of left hand prior to treatment with 5-fluorouracil cream. (b) Complete resolution of actinic keratoses at 6 months following treatment.

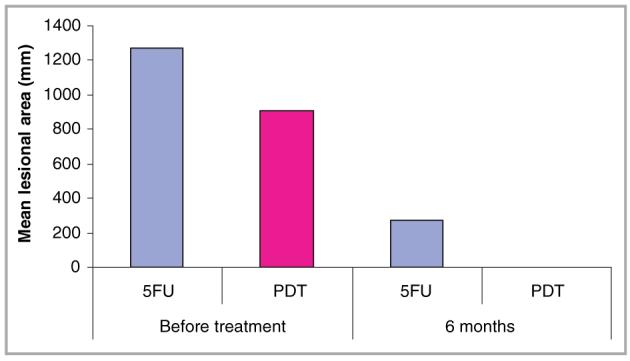

Before treatment, the mean lesional area was 1268 mm2 in the 5-FU group and 910 mm2 in the PDT group. At 6-month follow up, these had reduced to 272 mm2 and 2 mm2 respectively. This corresponded to a relative reduction in lesion size of 99% with topical PDT and 79% with 5-FU (Fig. 3). Lesion sizes in the 5-FU group were, however, larger at baseline than in the PDT group so multiple regression analysis was used to test indirectly for a treatment effect after adjusting for lesion size at baseline and pairing. This was not quite significant (P = 0·08).

Fig 3.

Mean lesional area before and 6 months after treatment with 5-fluorouracil (5FU) and photodynamic therapy (PDT).

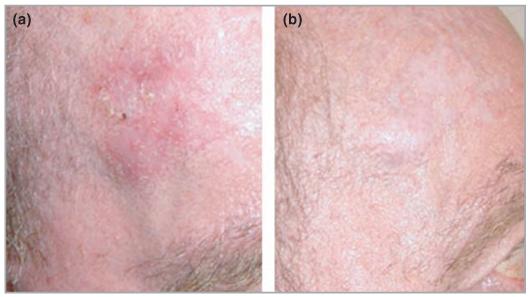

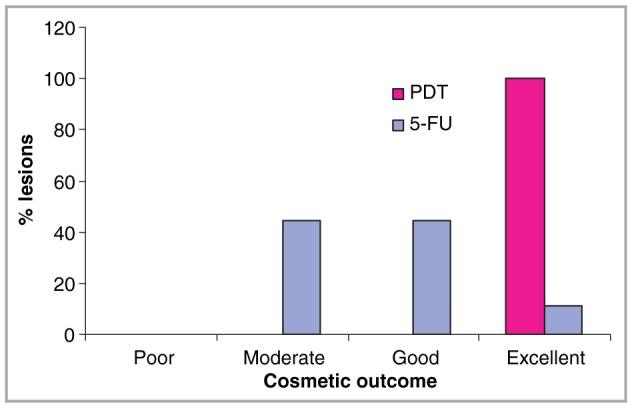

Overall, topical PDT achieved a superior cosmetic result compared to 5-FU, with all PDT-treated lesions achieving excellent cosmetic result (Figs 4,5). Furthermore, all patients stated that they preferred topical PDT to 5-FU in the global patient preference assessment performed at the end of the study.

Fig 4.

Carcinoma in situ (a) before and (b) 6 months after topical treatment with photodynamic therapy with methylaminolaevulinate.

Fig 5.

Overall cosmetic outcome following treatment with photodynamic therapy (PDT) vs. 5-fluorouracil (5-FU).

Adverse effects

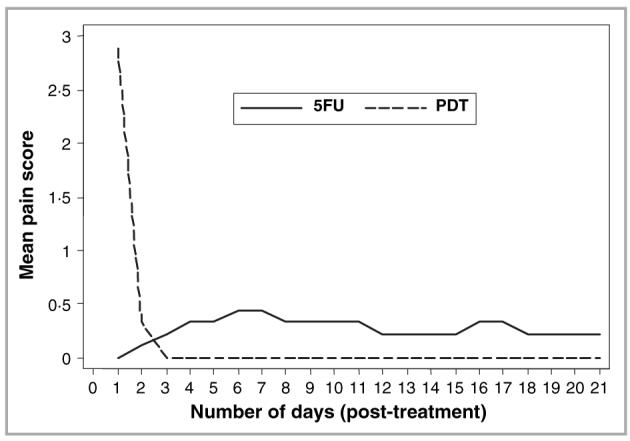

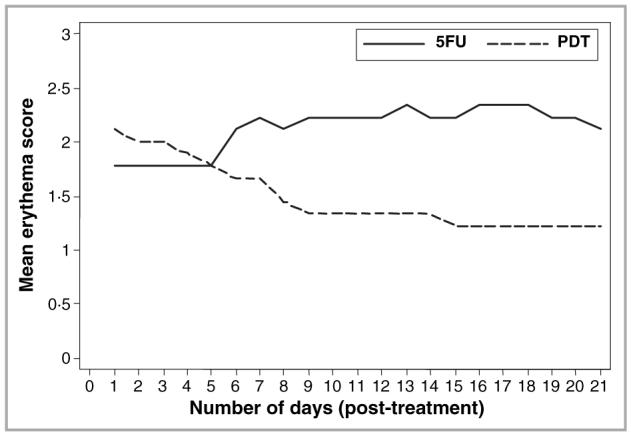

All patients experienced moderate to severe pain at treatment sites during the illumination phase of PDT. On cessation of illumination, the pain intensity reduced immediately, with subsequent resolution over the next few hours. Two patients continued to experience mild pain at PDT treatment sites on the day following treatment. Overall, pain intensity was considerably greater in PDT-treated lesions on day 1 of treatment compared with the first day of 5-FU treatment. By day 3 all PDT-treated lesions were pain free whilst the mean pain score for 5-FU-treated lesions was 0·22 (Fig. 6). The mean pain scores for 5-FU-treated lesions subsequently varied from 0·22 to 0·44, values considerably lower than those experienced during the illumination phase of PDT. The mean erythema scores were initially higher for PDT-treated lesional areas than for 5-FU-treated areas; this situation reversed by day 6 after treatment (Fig. 7). Other local reactions associated with 5-FU treatment included superficial erosions, crusting and pruritus. All patients experienced crusting of the treatment area after PDT, whilst three experienced pruritus and one developed postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. No deterioration in renal function was noted in any patient during the study.

Fig 6.

Mean daily pain scores for lesions treated with topical photodynamic therapy (PDT, dashed line) and 5-fluorouracil (5FU, solid line) based on a four-point visual analogue scale (0-3).

Fig 7.

Mean daily erythema scores for lesions treated with topical photodynamic therapy (PDT, dashed line) and 5-fluorouracil (5FU, solid line) based on a four-point visual analogue scale (0-3).

Discussion

In this study we compared the efficacy of topical PDT with 5-FU in clearing epidermal dysplasia in OTRs. To our knowledge this is the first study to undertake such comparison. We demonstrated the greater efficacy of PDT in achieving complete resolution of lesions, its superior cosmesis and patient preference over 5-FU, despite the initially higher levels of pain associated with PDT treatment.

Previous topical 5-fluorouracil studies

Topical 5-FU has been used in the treatment of AKs23 and CIS24 in a number of studies. It is inexpensive and of proven efficacy, with reported clearance rates in AKs of up to 90% in immunocompetent individuals.23 Although topical 5-FU is also widely used in OTRs, there are no systematic data regarding its efficacy and adverse effects in this group.

Previous topical photodynamic therapy studies

A number of studies in immunocompetent individuals report successful treatment of epidermal dysplasia using topical PDT, with clearance rates ranging from 69-100%.25-33 Four previous studies have also used PDT in OTRs (Table 2).11,20,34,35 Dragieva et al.20 treated epidermal dysplasia (AK, CIS) in 20 OTRs and 20 controls with topical PDT using 5-ALA, and in a second study compared MAL PDT with placebo in the treatment of 129 AKs in 17 OTRs.11 In the first study, the overall CRR in OTRs at 4, 12 and 48 weeks was 86%, 68% and 48% respectively, whilst in the second study, the overall CRR at 4 months was 90% (56 of 62) for PDT and 0 (0 of 67) for placebo. Schleier et al.34 treated a total of 32 cutaneous lesions, comprising AKs, BCCs, keratoacanthomas and SCCs, in five OTRs and reported a CRR of 75% at 3 months. The apparent decline in efficacy with time following PDT20 may be due to either recurrence of inadequately treated lesions, or the appearance of new lesions at the treated site. Most recently, however, a randomized controlled trial in 40 OTRs by de Graaf et al.35 has reported that PDT showed no statistically significant effect on reduction of keratotic skin lesions on the arm treated with either one or two cycles of PDT.

Table 2.

Summary of existing clinical studies using topical photodynamic therapy in organ transplant recipients

| Author | AK (n) | BD (n) | Other (n) | Photosensitizer | Light dose (J cm−2) | Intensity (mW cm−2) | Light source | No. patients | Response | Follow up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| de Graaf et al. (2006)35 | ‘Keratotic lesions’a? number | ALA | 5·5-6 | - | Philips HPM-10 (400-450 nm) | 40 | No significant difference between PDT and control | 12 | ||

| Dragieva et al. (2004)20 | 40 | 4 | ALA | 75 | 80 | Waldmann PDT 1200 (600-730 nm) | 20 | 1/12: 86% CRR 3/12: 68% CRR 12/12: 48% CRR |

12 | |

| Dragieva et al. (2004)11 | 129 | MAL | 75 | 80 | Waldmann PDT 1200 (600-730 nm) | 17 | 56/62 CR | 4 | ||

| Schleier et al. (2004)34 | 8 | BCC:21 KA:1 SCC:2 | ALA | 120 | 100 | Diode laser (635 nm) | 5 | 75% CRR (after one treatment) 18·8% required 2-3 treatments for CR 5·6% no response (invasive SCC) |

3 |

AK, actinic keratosis; ALA, aminolaevulinic acid; BCC, basal cell carcinoma; BD, Bowen disease; CR, complete resolution; CRR, complete resolution rate; KA, keratoacanthoma; MAL, methyl 5-aminolaevulinate; PDT, photodynamic therapy; SCC squamous cell carcinoma.

Keratotic lesions comprised actinic keratoses, flat warts, seborrhoeic warts and common warts.

Previous comparative studies of 5-fluorouracil and photodynamic therapy

There are two published studies comparing 5-FU and PDT in immunocompetent individuals30,36 but none, to our knowledge, in OTRs. In a study of immunocompetent individuals topical PDT was more effective than topical 5-FU in the treatment of CIS, with observed CRRs of 82% vs. 48% respectively at 12 months.30 In a second study, topical PDT and 5-FU had similar efficacy in the treatment of AKs (73% and 70% reduction in mean lesional area respectively) over a 6-month follow up.36

Comparison of previous studies with our data

In our study, topical MAL PDT was more effective than topical 5-FU in the treatment of epidermal dysplasia. A clearance rate of 0·89 at 6 months for topical PDT is similar to that reported in most existing open studies in both immunocompetent25-33 and OTRs.11,20,34 However, the efficacy of PDT was lower in the most recent study in OTRs.35 A number of possible explanations may account for the discrepancies between these data and our own, including: (i) the treated keratotic lesions in the study by de Graaf and colleagues were not histologically confirmed and were not all necessarily areas of epidermal dysplasia; (ii) violet light (400-450 nm) was used, which has reduced penetration compared with red light (600-700 nm); (iii) failure to remove lesional hyperkeratotic scale and crust before treatment may have prevented adequate penetration of photosensitizer; (iv) 5-ALA was used which penetrates less deeply than MAL; (v) the treatment protocol may not have been optimal with only half of the lesions treated twice but with a 6-month gap in between rather than 1 week; and (vi) our study sample was small.

We did not experience a decline in CRR with time for PDT-treated lesions as reported by Dragieva et al.20 and, once again, different methods may have partly accounted for this. Indeed, such practical considerations may be of particular relevance in optimizing PDT for immunosuppressed individuals.37

The improved outcome for PDT vs. 5-FU in our study appears, at least in part, to reflect a poorer than expected clearance of epidermal dysplasia with 5-FU in our patient group. From data in immunocompetent patients, we might have expected a 90% clearance rate, as compared with the 11% CRR that we observed at 6 months. No previous data exist for the treatment of epidermal dysplasia in OTRs and it is possible that 5-FU regimens recommended for treatment of immunocompetent patients are not appropriate for OTRs. Equally, the high frequency with which new lesions arise in high-risk OTR may mask efficacy if 5-FU is not as effective as PDT in prophylaxis against the development of new primary lesions within the treated area.

Complete vs. partial clearance rates

Both the complete and partial clearance data from our study suggest that PDT is more effective in treating epidermal dysplasia than 5-FU. Where complete resolution was the outcome measure, the difference between treatments was more pronounced and the associated statistical test had more power (P = 0·02). Where reduction in lesional size was assessed, after adjusting for the pretreatment area, the power to detect a difference was less, so that our data in this respect did not reach statistical significance (P = 0·08). When we employed a definition of PR based upon the EORTC guidelines22 (i.e. > 30% reduction in the longest diameter of a lesion), two of the nine lesions treated with 5-FU which had been previously designated as PRs no longer fulfilled the criteria for PR and were reclassified as NRs, resulting in a greater apparent difference between PDT and 5-FU in favour of PDT (P = 0·004).

Cosmesis, adverse effects and patient preference

The differences in cosmetic outcome between PDT and 5-FU were clinically relevant, although formal testing was not undertaken because of the small sample size. For adverse effects and tolerability, there was no clear advantage of one treatment over the other; both 5-FU and MAL-PDT were associated with pain and erythema. With PDT, intense pain occurred during illumination but in most cases this subsided over the following 12 h, whilst for 5-FU discomfort and pain were sustained throughout the 3 weeks of treatment, albeit they were less intense than for PDT. Overall, however, patients preferred PDT to 5-FU in the global patient preference assessment.

Future considerations

There remain a number of considerations for future studies, including studies to optimize efficacy of 5-FU and PDT in OTRs.37 Longitudinal studies on the effect of both PDT and 5-FU on the subsequent risk of SCC in the treated areas also need to be addressed. In mouse models, repetitive ALA-PDT suppresses the development of SCC38,39 but de Graaf et al.35 failed to demonstrate this effect in OTRs.

Concerns about the longer-term efficacy and safety profile of topical PDT in immunosuppressed patients include the possibility that recurrence following treatment is more common than in immunocompetent patients. PDT is both a cytotoxic (destructive) agent and a biological response modifier.37,40,41 The host immune response is likely to be an important adjunct to the antitumour effects of PDT,40 and an impaired immune system may compromise the outcome of PDT over the longer term.37,40,41 Such an effect may explain the reduction in CRR at 12 and 48 weeks previously described following PDT in OTRs.20 Another concern is the long-term safety of PDT in patients on azathioprine who accumulate DNA thiopurines as a consequence of treatment. Although singlet oxygen produced by PDT may induce DNA strand breaks, chromosomal aberrations and DNA alkylation, its radius of action is only 0·01 μm and so the potential for mutagenic DNA damage is low.42-44 This is reflected by the fact that previously only two tumours have possibly been induced by PDT.45 However, DNA thiopurines, which accumulate in the DNA of patients on long-term azathioprine, are more reactive than normal DNA bases and particularly susceptible to oxidation by reactive oxygen species generated by PDT. Such oxidative products are potentially mutagenic and could contribute further to the burden of skin cancer in OTRs over the longer term.46

In conclusion, our study has demonstrated potential benefits of topical PDT over 5-FU in the treatment of premalignant skin lesions in OTRs. Assessment of its long-term efficacy, its effect on the subsequent development of SCC and its safety, particularly in OTRs, are now research priorities in this field.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the generous support of the Royal London Hospital Kidney Patients Association and also to Phototherapeutics Ltd for providing an Omnilux light source for the duration of this study.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest

C.M.P. has received funding from Galderma to attend conferences.

References

- 1.Penn I. Incidence and treatment of neoplasia after transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1993;12:S328–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Euvrard S, Kanitakis J, Claudy A. Skin cancers after organ transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1681–91. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra022137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jensen P, Hansen S, Moller B, et al. Skin cancer in kidney and heart transplant recipients and different long-term immunosuppressive therapy regimens. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;40:177–86. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70185-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hartevelt MM, Bavinck JN, Koote AM, et al. Incidence of skin cancer after renal transplantation in The Netherlands. Transplantation. 1990;49:506–9. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199003000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ramsay HM, Fryer AA, Hawley CM, et al. Non-melanoma skin cancer risk in the Queensland renal transplant population. Br J Dermatol. 2002;147:950–6. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04976.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bouwes Bavinck JN, Hardie DR, Green A. The risk of skin cancer in renal transplant recipients in Queensland, Australia. A follow-up study. Transplantation. 1996;61:715–21. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199603150-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Webb MC, Compton F, Andrews PA, et al. Skin tumours posttransplantation: a retrospective analysis of 28 years’ experience at a single centre. Transplant Proc. 1997;29:828–30. doi: 10.1016/s0041-1345(96)00152-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barr BB, Benton EC, McClaren K, et al. Human papilloma virus infection and skin cancer in renal allograft recipients. Lancet. 1989;1:124–9. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)91143-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stockfleth E, Ulrich C, Meyer T, et al. Epithelial malignancies in organ transplant patients: clinical presentation and new methods of treatment. Recent Results Cancer Res. 2002;160:251–8. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-59410-6_30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dreno B. Skin cancers after transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2003;18:1052–8. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfg023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dragieva G, Prinz BM, Hafner J, et al. A randomized controlled clinical trial of topical photodynamic therapy with methyl aminolaevulinate in the treatment of actinic keratoses in transplant recipients. Br J Dermatol. 2004;151:196–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown V, Atkins CL, Ghali L, et al. Safety and efficacy of 5% imiquimod cream for the treatment of skin dysplasia in high-risk renal transplant recipients: randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Dermatol. 2005;141:985–93. doi: 10.1001/archderm.141.8.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eaglstein WH, Weinstein GD, Frost P. Fluorouracil: mechanism of action in human skin and actinic keratoses. I. Effect on DNA synthesis in vivo. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:132–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peng Q, Soler AM, Warloe T, et al. Selective distribution of porphyrins in skin thick basal cell carcinoma after topical application of methyl 5-aminolevulinate. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;62:140–5. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kloek J, Beijersbergen van H. Prodrugs of 5-aminolevulinic acid for photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 1996;64:994–1000. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1996.tb01868.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uehlinger P, Zellweger M, Wagnieres G, et al. 5-Aminolevulinic acid and its derivatives: physical chemical properties and protoporphyrin IX formation in cultured cells. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2000;54:72–80. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(99)00159-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fritsch C, Homey B, Stahl W, et al. Preferential relative porphyrin enrichment in solar keratoses upon topical application of deltaaminolevulinic acid methylester. Photochem Photobiol. 1998;68:218–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rud E, Gederaas O, Hogset A, Berg K. 5-aminolevulinic acid, but not 5-aminolevulinic acid esters, is transported into adenocarcinoma cells by system BETA transporters. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;71:640–7. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0640:aabnaa>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gardlo K, Ruzicka T. Metvix (PhotoCure) Curr Opin Investig Drugs. 2002;3:1672–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dragieva G, Hafner J, Reinhard D, et al. Topical photodynamic therapy in the treatment of actinic keratoses and Bowen’s disease in transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2004;77:115–21. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000107284.04969.5C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pocock SJ. Clinical Trials: A Practical Approach. Chichester: John Wiley and Sons; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Therasse P, Arbuck SG, Eisenhauer EA, et al. European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer. National Cancer Institute of the United States. National Cancer Institute of Canada New guidelines to evaluate the response to treatment in solid tumors. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:205–16. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.3.205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pearlman DL. Weekly pulse dosing: effective and comfortable topical 5-fluorouracil treatment of multiple facial actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:665–7. doi: 10.1016/0190-9622(91)70250-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bargman H, Hochman J. Topical treatment of Bowen’s disease with 5-Fluorouracil. J Cutan Med Surg. 2003;7:101–5. doi: 10.1007/s10227-002-0158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Szeimies RM, Karrer S, Sauerwald A, et al. Photodynamic therapy with topical application of 5-aminolevulinic acid in the treatment of actinic keratoses: an initial clinical study. Dermatology. 1996;192:246–51. doi: 10.1159/000246376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Szeimies RM, Karrer S, Radakovic-Fijan A, et al. Photodynamic therapy using topical methyl 5-aminolevulinate compared with cryotherapy for actinic keratosis: a prospective, randomized study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;47:258–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pariser DM, Lowe NJ, Stewart DM, et al. Photodynamic therapy with topical methyl aminolevulinate for actinic keratosis: results of a prospective randomized multicenter trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2003;48:227–32. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2003.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman M, Vinciullo C, Francis D, et al. A comparison of photodynamic therapy using topical methyl aminolevulinate (Metvix) with single cycle cryotherapy in patients with actinic keratosis: a prospective, randomized study. J Dermatol Treat. 2003;14:99–106. doi: 10.1080/09546630310012118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Varma S, Wilson H, Kurwa HA, et al. Bowen’s disease, solar keratoses and superficial basal cell carcinomas treated by photodynamic therapy using a large-field incoherent light source. Br J Dermatol. 2001;144:567–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2001.04085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Salim A, Leman JA, McColl JH, et al. Randomized comparison of photodynamic therapy with topical 5-fluorouracil in Bowen’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 2003;148:539–43. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2003.05033.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cairnduff F, Stringer MR, Hudson EJ, et al. Superficial photodynamic therapy with topical 5-aminolaevulinic acid for superficial primary and secondary skin cancer. Br J Cancer. 1994;69:605–8. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1994.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Morton CA, Whitehurst C, Moore JV, et al. Comparison of red and green light in the treatment of Bowen’s disease by photodynamic therapy. Br J Dermatol. 2000;143:767–72. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2000.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Morton CA, Whitehurst C, Moseley H, et al. Comparison of photodynamic therapy with cryotherapy in the treatment of Bowen’s disease. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:766–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schleier P, Hyckel P, Berndt A, et al. Photodynamic therapy of virus-associated epithelial tumours of the face in organ transplant recipients. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2004;130:279–84. doi: 10.1007/s00432-003-0539-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.de Graaf YG, Kennedy C, Wolterbeek R, et al. Photodynamic therapy does not prevent cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma in organtransplant recipients: results of a randomised-controlled trial. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:569–74. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kurwa HA, Yong-Gee SA, Seed PT, et al. A randomized paired comparison of photodynamic therapy and topical 5-fluorouracil in the treatment of actinic keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41:414–8. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(99)70114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Oseroff A. PDT as a cytotoxic agent and biological response modifier: implications for cancer prevention and treatment in immunocompromised and immunocompetent patients. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:542–4. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Stender IM, Bech-Thomsen N, Poulsen TY, Wulf HC. Photodynamic therapy with topical delta-aminolaevulinic acid delays UV photocarcinogenesis in hairless mice. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;66:493–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb03178.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu Y, Viau G, Bissonette R. Multiple large-surface photodynamic therapy sessions with topical or systemic aminolevulinc acid and blue light in UV-exposed hairless mice. J Cut Med Surg. 2004;8:131–9. doi: 10.1007/s10227-004-0117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Korbelik M, Krosl G, Krosl J, et al. The role of host lymphoid populations in the response of mouse EMT6 tumor to photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 1996;56:5647–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Korbelik M, Dougherty GJ. Photodynamic therapy-mediated immune response against subcutaneous mouse tumors. Cancer Res. 1999;59:1941–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Moan J, Waksvik H, Christensen T. DNA single stranded breaks and sister chromatid exchanges induced by treatment with hematoporphyrin and light or by X-rays in human NHIK 3025 cells. Cancer Res. 1980;40:2915–18. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Douki T, Onuki J, Medeiros MGH, et al. DNA alkylation by 4,5-dioxovaleric acid, the final oxidation product of 5-aminolevulinic acid. Chem Res Toxicol. 1998;11:150–7. doi: 10.1021/tx970157d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fuchs J, Weber S, Kaufmann R. Genotoxic potential of porphyrin type photosensitisers with particular emphasis on 5-aminolevulinic acid: implications for clinical photodynamic therapy. Free Rad Biol Med. 2000;28:537–48. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(99)00255-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Morton CA, Brown SB, Collins S, et al. Guidelines for topical photodynamic therapy: report of a workshop of the British Photodermatology Group. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:552–67. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2133.2002.04719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.O’Donovan P, Perrett CM, Zhang X, et al. Azathioprine and UVA light generate mutagenic oxidative DNA damage. Science. 2005;309:1871–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1114233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]