Abstract

The plasma level of LDL cholesterol is clinically important and genetically complex. LDL cholesterol levels are in large part determined by the activity of LDL receptors (LDLR) in the liver. Autosomal dominant familial hypercholesterolaemia (FH) – with its high LDL cholesterol levels, xanthomas, and premature atherosclerosis – is caused by mutations in either the LDLR or in APOB – the protein in LDL recognised by the LDLR. A third, rare form – autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia – arises from mutations in the gene encoding an adaptor protein involved in the internalisation of the LDLR. A fourth variant of inherited hypercholesterolaemia was recently found to be associated with missense mutations in PCSK9, which encodes a serine protease that degrades LDLR. Whereas the gain-of-function mutations in PCSK9 are rare, a spectrum of more frequent loss-of-function mutations in PCSK9 associated with low LDL cholesterol levels has been identified in selected populations and could protect against coronary heart disease. Heterozygous familial hypobetalipoproteinaemia (FHBL) – with its low LDL cholesterol levels and resistance to atherosclerosis – is caused by mutations in APOB. In contrast to other inherited forms of severe hypocholesterolaemia such as abetalipoproteinaemia - caused by mutations in MTP - and homozygous FHBL, a deficiency of PCSK9 appears to be benign. Rare variants of NPC1L1, the gene encoding the putative intestinal cholesterol receptor, have shown more modest effects on plasma LDL cholesterol than PCSK9 variants, similar in magnitude to the effect of common APOE variants. Taken together, these findings indicate that heritable variation in plasma LDL cholesterol is conferred by sequence variation in various loci, with a small number of common and multiple rare gene variants contributing to the phenotype.

Introduction

Genetic, pathological and epidemiological studies have clearly shown that plasma levels of LDL cholesterol are directly related to the incidence of coronary events and cardiovascular deaths. Elevated concentrations of apoB-containing lipoproteins, particularly LDL, are associated with an increased risk of developing atherosclerotic coronary heart disease (CHD).1 Clinical trials using lipid-lowering drugs have unequivocally shown that lowering plasma LDL cholesterol results in significant reductions in both morbidity and mortality from CHD in patients with or without established CHD.2,3 Furthermore, plasma LDL cholesterol reduction as secondary prevention increases survival rates.

Plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations vary over a three-fold range in the population. It is estimated that up to 50% of the interindividual variation in plasma LDL cholesterol levels is due to genetic variation,4 and that the major portion of this variation is polygenic attributable to sequence variation in various loci. A small percentage of patients with very high or low plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations have monogenic forms of hypercholesterolaemia or hypocholesterolaemia. This review gives an overview of LDL metabolism, the genes affecting plasma concentrations of LDL cholesterol, and the mechanism by which mutations in these genes affect LDL cholesterol levels.

LDL Metabolism

Lipids are water-insoluble organic molecules, and include triglycerides, cholesterol and its esters, and phospholipids. As they are hydrophobic molecules they do not circulate freely in blood, but instead are transported in plasma in particles called lipoproteins from their sites of absorption or synthesis to the peripheral tissues. Lipoproteins are spherical complexes of lipids, and apoproteins that stabilise the lipid emulsions and act as ligands for receptor-mediated processes.

LDL, a cholesterol-rich lipoprotein, is the metabolic product of VLDL, a triglyceride-rich lipoprotein secreted by the liver. ApoB-100, the structural backbone of LDL, is essential for the assembly and secretion of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. In a normal individual, LDL contains ~70% of the total plasma cholesterol. Each LDL particle contains a single molecule of apoB which cannot be exchanged or lost to other lipoproteins, and as such, fasting plasma apoB-100 concentrations directly reflect the number of circulating LDL particles. Like LDL cholesterol, plasma levels of apoB are directly related to the incidence of coronary events and cardiovascular deaths.

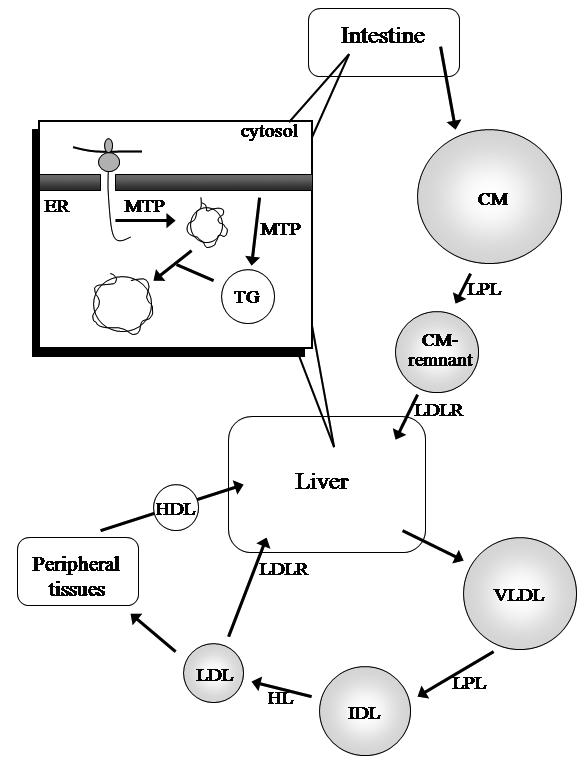

In the liver, a two-step model for lipoprotein assembly has been accepted as the mechanism for VLDL production (Figure 1).5 Initially, a lipid-poor apoB is synthesised, followed by the bulk addition of neutral lipids to its core. The chaperone microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) stabilises the nascent apoB within the cell endoplasmic reticulum, and facilitates the transfer of lipids from the endoplasmic reticulum membrane to apoB.6 A similar process occurs in the intestine to form triglyceride-rich chylomicrons, containing apoB-48.7 ApoB-48 is produced from the same gene as apoB-100, but in the intestine, an mRNA editing process occurs which results in only the amino-terminal 48% of apoB-100 being produced.8,9

Figure 1.

ApoB-containing lipoprotein production and metabolism. As its synthesis occurs, apoB is directed to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) via its signal peptide sequence, and formation of a nascent lipoprotein facilitated by the chaperone MTP. This is followed by bulk triglyceride (TG) addition to form the lipoprotein (Inset). The intestine secretes apoB-48-containing chylomicrons (CM), which are metabolised to remnant particles that are subsequently cleared, mediated by apoE, by receptors in the liver. The liver secretes apoB-100-containing VLDL, and its core triglycerides are hydrolysed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL) to form IDL, which is further metabolised by hepatic lipase (HL) to form LDL. LDL is cleared mostly by the LDLR, into the liver or peripheral tissues. HDL facilitates reverse cholesterol transport, the transport of lipids from peripheral tissues to the liver.

In the circulation, VLDL triglyceride is hydrolysed by lipoprotein lipase on the endothelial surface and the released free fatty acids are taken up by peripheral tissues. This process converts VLDL to smaller, denser particles. Some of these VLDL remnants are cleared from the circulation, while the remaining particles enter the VLDL→LDL lipolytic cascade.

In this pathway, intermediate density lipoprotein (IDL) is formed by the hydrolysis of core triglyceride by lipases. IDL is either cleared by the liver (mediated by apoE) or further metabolised to LDL. Most of the LDL particles are cleared by the liver via the LDL receptor (LDLR).10 The LDLR pathway was elucidated by Brown and Goldstein, for which they were awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1985. Both apoB-100 and apoE are ligands for LDLR-mediated uptake, but as LDL contains no apoE, apoB-100 is the sole ligand for LDL clearance.11

LDL in the circulation can become modified by oxidation in the arterial wall, and taken up by macrophages. These macrophages become cholesterol-loaded ‘foam cells’, and their accumulation within the vessel wall is an early sign of atherosclerosis.12 Fatty streaks can develop into a fibrous cap. This fibrous cap can become unstable, and rupture results in formation of a thrombus, which can cause further occlusion at the site of formation or at a distant site, which can result in myocardial infarction or stroke.

Inherited disorders of lipoprotein metabolism help us to understand these pathways. Mutations of genes affecting apoB production and secretion tend to result in reduced circulating LDL and hypobetalipoproteinaemia, whereas mutations in genes involved in clearance of LDL by the LDLR tend to result in increased circulating LDL and hypercholesterolaemia.

Gene Variants Affecting LDL Cholesterol Levels

Table 1 summarises the major genes affecting circulating LDL cholesterol levels. These range from common variants having small effects (e.g. apoE), to rare mutations causing hypo- and hypercholesterolaemia.

Table 1.

Summary of major genes affecting plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations.

| Gene | Protein | Gene locus | Mutation frequency | Effect of mutation on LDL | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| APOB | Apolipoprotein B | 2p24 | 1:500 | 200–300% increase (familial ligand- defective apoB-100) | Decreased clearance of LDL due to defective binding with LDLR |

| 1:3000 | >50% decrease (heterozygous familial hypobetalipoproteinaemia) | Decreased production of apoB-containing lipoproteins | |||

| 1:1 million | Absent or very low (homozygous familial hypobetalipoproteinaemia) | Ability to assemble and secrete apoB-containing lipoproteins either absent or markedly reduced | |||

| APOE | Apolipoprotein E | 19q13.2 | E2 0.06 | 5% decrease in E2 vs E3 | E2-containing lipoproteins have delayed clearance, leading to up-regulation of LDLR |

| E3 0.81 | - | - | |||

| E4 0.13 | 5% increase in E4 vs E3 | E4 lipoproteins catabolised rapidly leading to increased hepatic cholesterol and down-regulation of LDLR | |||

| ARH | Adaptor protein | 1p36-p35 | 1:10 million | 300–1000% increase (autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia) | ARH adaptor protein absent or unable to interact with the LDLR and promote LDLR clustering in clathrin-coated pits |

| LDLR | LDL receptor | 19p13.2 | 1:500 | 200–300% increase (heterozygous) | Defective LDLR production, function, or recycling leads to reduced clearance of LDL |

| 1:1 million | 500–1000% increase (homozygous) | ||||

| MTP | Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein | 4q22-q24 | 1:1 million | Absent or very low (abetalipoproteinaemia; recessive) | ApoB-containing lipoproteins unable to be assembled, due to the absence, or defective activity, of the chaperone MTP |

| NPC1L1 | Niemann-Pick C 1-like 1 protein | 7p13 | Unknown | Multiple variants with small effects | Unknown |

| PCSK9 | Proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin-type 9 | 1p34.1-p32 | Unknown 2% African Americans | 200–300% increase (gain-of-function mutations) 30% decrease (nonsense mutations) | PCSK9 degrades the LDLR; gain-of-function mutations reduce LDLRs on the cell surface and lead to accumulation of LDL in plasma Fewer LDLRs are degraded, due to reduced PCSK9 activity, allowing more LDL particles to be cleared from plasma |

APOE

ApoE has an important role in the metabolism of remnant lipoproteins (chylomicron remnants and IDL) by binding to the LDLR and LDLR-related protein and mediating clearance of lipoproteins from the circulation. However, the mechanism for the association between apoE and atherosclerosis is not clear. This 299 amino acid protein also plays a role in neuronal growth and repair, inflammation, and in the immune system mediating the presentation of serum-borne lipid antigens.13,14 ApoE and its isoforms have also been implicated in the pathogenesis of neurological disorders, including multiple sclerosis and Alzheimer’s disease.15

There are three common APOE isoforms, named epsilon 2, 3 and 4, differing at two amino acid positions. ApoE2 has two cysteine residues at positions 112 and 158, whereas E4 has two arginines and E3 Cys112 and Arg158. E3 is the most common isoform, with a frequency in Australia of 0.81, followed by E4 (0.13) and E2 (0.06).16 Approximately 10% of inter-individual variation in total cholesterol concentrations is due to the apoE polymorphism.17 Historically, apoE phenotyping was determined by isoelectric focusing, but this has been replaced by modern genotyping techniques.

E4 carriers have 5% higher plasma LDL cholesterol levels, and have slightly increased risk for CHD compared to E3 carriers.18 ApoE4 has a high affinity for LDLR compared to E2 and E3. Particles containing E4 are therefore catabolised more rapidly than E3, leading to increased hepatic cholesterol and down-regulation of the LDLR, resulting in increased plasma LDL cholesterol levels.19 E2 carriers have ~5% lower plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations and a 20% lower risk of CHD.18 E2 binds LDLR about 1% that of E3, resulting in delayed clearance of apoE2-carrying lipoproteins, which leads to up-regulation of the LDLR.19 Homozygosity for apoE2 is also associated with familial dysbetalipoproteinaemia (type III hyperlipidaemia), a remnant hyperlipidaemia characterised by elevated plasma triglyceride and cholesterol concentrations.

NPC1L1

The function of NPC1L1 remains to be determined. It plays a role in intestinal cholesterol transport and, until very recently, was thought to be the molecular target of the cholesterol absorption inhibitor ezetimibe.20,21 However, NPC1L1 is also expressed in the liver, and a recent study has shown that NPC1L1 allows the retention of biliary cholesterol by hepatocytes and that ezetimibe disrupts hepatic NPC1L1 function.22

Variants in NPC1L1 are associated with reduced sterol absorption and plasma LDL levels.23 Multiple rare variants of NPC1L1 were found in low cholesterol absorbers. These variants were found in 6% of African Americans, and were associated with lower plasma levels of LDL cholesterol (2.5 vs 2.7 mmol/L).23 A possible relationship between NPC1L1 variation and ezetimibe response has also been reported.24,25

Polygenic, Sporadic and Multifactorial Hypercholesterolaemia

These terms have been used to describe hypercholesterolaemia of uncertain aetiology. They may occur in the absence of a positive family history (sporadic), may be associated with a familial component of unclear mode of inheritance or may be interpreted as being the result of the interaction of multiple genes with a small effect (polygenic). They may also result from one or more environmental factors (e.g. high saturated fat/cholesterol diet, obesity, caloric excess, stress, subclinical hypothyroidism, pregnancy, menopause) interacting (or otherwise) with a genetic predisposing factor or susceptibility gene (multifactorial). Polygenic hypercholesterolaemia is more common than FH, and importantly, tendon xanthomas are absent with this disorder.

Monogenic Hypercholesterolaemia

Monogenic hypercholesterolaemia is characterised by high levels of circulating LDL and reduced clearance of LDL from plasma by the LDLR pathway, leading to premature CHD. Inheritance is usually autosomal codominant and commonly results from defective apoB binding to LDLR (familial ligand-defective apoB, FDB) or mutations in LDLR FH. In rare cases mutations in PCSK9 have been identified. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia (ARH) is even rarer and is caused by mutations in the adaptor protein named ARH.

LDLR

The familial clustering of patients showing xanthomas, premature coronary artery disease (CAD), and hypercholesterolaemia was first recognised in the 1930s and led to the suggestion of a genetic basis for the disorder.26 Khachadurian in the early 1960s studied Lebanese families with hypercholesterolaemia and deduced the differences between heterozygotes and homozygotes, providing the evidence for a single-gene disorder.27 In 1974, Brown and Goldstein reported the discovery of the LDLR and demonstrated that LDLR defects cause FH.28 Since the characterisation of the LDLR gene in 198529 there have been ~800 known LDLR mutations identified causing FH.30 The frequency of FH among Caucasians has been estimated at 1:500, and is therefore thought to be one of the two most common human diseases caused by mutations in a single gene, the other being haemochromatosis.26 FH is more prevalent in certain populations: 1:100 Afrikaners, 1:170 Christian Lebanese, and 1:270 French Canadians.26

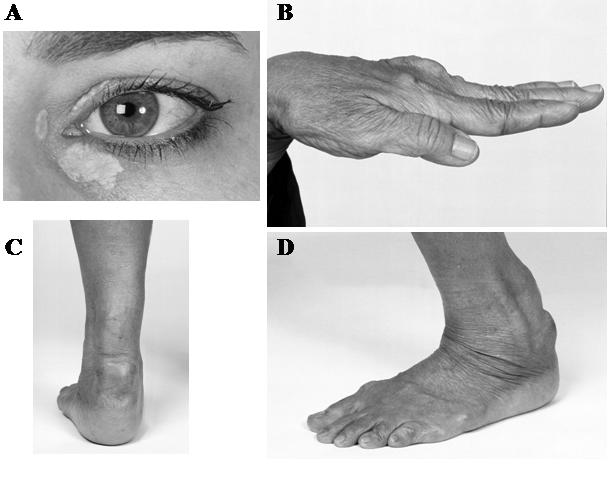

In heterozygous FH, plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations are typically two to three times normal at 5–11 mmol/L. Cholesterol deposits around the body, manifesting in the eyes as corneal arcus and xanthelasma, and tendons, particularly the Achilles, as xanthomas (Figure 2). These manifestations are common after age 20 years, followed by the development of CAD. Estimates suggest that 75% of male heterozygotes and 45% of female heterozygotes have symptoms of CHD by the age of 60 years.26 There is little impact on LDL cholesterol levels in FH heterozygotes by optimising other cardiovascular risk factors. Instead, lifelong cholesterol-lowering therapy with agents such as statins and ezetimibe, is recommended, commencing in children aged over 10 years.31

Figure 2.

Discrete clinical manifestations of FH. A, Corneal arcus and xanthelasma; B, extensor tendon xanthomas; C and D, Achilles tendon xanthomas.

Homozygous FH is rare, found in one in a million individuals, and characterised by large elevations in plasma LDL (in the order of 15 24 mmol/L) and severe cutaneous and tendinous xanthomas, with coronary atherosclerosis occurring in childhood.26 Untreated, FH homozygotes will often die before reaching age 20 years, and there have been reports of children as young as 18 months experiencing acute myocardial infarction. Drug treatments are not as effective in FH homozygotes compared to heterozygotes. LDL apheresis, the direct removal of LDL from plasma, performed every 1–2 weeks on a long-term basis, can reduce plasma LDL cholesterol by ~70%.26 Despite LDL apheresis, patients remain at increased risk for the development and progression of atherosclerotic CHD. Although liver transplantation offers the most definitive therapy for homozygous FH, it requires major surgery and lifelong immunosuppression. FH is a good candidate disease for liver-targeted gene therapy.

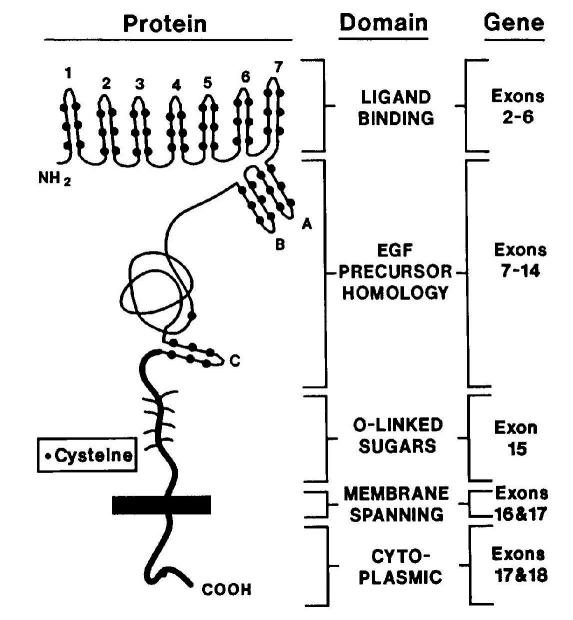

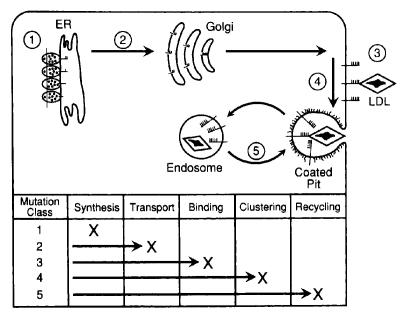

The LDLR protein consists of five domains: ligand-binding, epidermal growth factor (EGF) precursor homology, O-linked sugars, membrane-spanning and cytoplasmic domains (Figure 3).26,32 Mutations causing FH span the entire LDLR gene, but are most commonly found in the ligand-binding and the EGF-precursor homology domain. Mutations are classed into five categories according to their phenotypic effects on the LDLR protein: defects in synthesis, transport, binding, internalisation and recycling (Figure 4). Mutations include nucleotide substitutions (missense and nonsense), splice site mutations, and small deletions and insertions, and ~10% are large structural rearrangements. These major gene rearrangements can be readily detected by multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification analysis.

Figure 3.

Structure of LDLR protein, related to gene structure. Exon 1 encodes a signal sequence which is cleaved during LDLR synthesis. Exons 2–18 encode the mature 839 amino acid protein, which consists of five domains. Reprinted, with permission, from the Annual Review of Genetics, Volume 24 c1990 by Annual Reviews www.annualreviews.org.32

Figure 4.

Classification of LDLR mutations based on function. These mutations disrupt the synthesis of mature LDLR, transport to the Golgi complex, binding of apoprotein ligands, clustering in clathrin-coated pits, and recycling. Reprinted, with permission, from the Annual Review of Genetics, Volume 24 c1990 by Annual Reviews www.annualreviews.org.32

Of the estimated 40,000 cases of FH in Australia, only 20% are diagnosed and less than 10% are being adequately treated.33 An international initiative, Make Early Diagnosis - Prevent Early Death (MED-PED), has been established in many countries, with the goal of identifying individuals with FH and providing treatment. Other criteria for FH diagnosis, such as the Dutch Lipid Network criteria34 (Table 2) and UK-based Simon Broome Register Group criteria,35 have been established. The Dutch have been particularly successful, by 2005 identifying ~3000 index cases and over 7000 relatives since the inception of a national screening program in 1994.36

Table 2.

Dutch Lipid Network clinical criteria for diagnosis of heterozygous familial hypercholesterolaemia.

| Criteria | Points | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Family history | ||

| A first degree relative with known: | ||

| a) Premature* coronary and vascular disease | 1 | |

| b) Plasma LDL-C concentration >95th percentile for age and sex | ||

| i) In an adult relative | 1 | |

| ii) In a relative <18 years of age | 2 | |

| c) Tendon xanthomata or arcus cornealis | 2 | |

| 2. Clinical history | ||

| Patient has premature*: | ||

| a) Coronary artery disease | 2 | |

| b) Cerebral or peripheral vascular disease | 1 | |

| 3. Physical examination of the patient | ||

| a) Tendon xanthomata | 6 | |

| b) Arcus cornealis in a patient <45 years of age | 4 | |

| 4. LDL-C levels in patient’s blood (mmol/L) | ||

| a)≥8.5 | 8 | |

| b) 6.5–8.4 | 5 | |

| c) 5.0–6.4 | 3 | |

| d) 4.0–4.9 | 1 | |

| 5. DNA analysis showing functional mutation in the LDLR or other FH-related gene | 8 | |

| Interpretation | Diagnosis | Total points |

| Definite FH | >8 | |

| Probable FH | 6–8 | |

| Possible FH | 3–5 | |

if male, <55 years; if female, <60 years.

Reprinted with permission from the World Health Organization.34

Due to phenotypic heterogeneity, there is a need for accurate clinical diagnostic criteria for the early diagnosis of FH, if a genetic diagnosis has not been made. Genetic testing plays a key role in screening programs for FH which are under development in many Western countries.37 In addition to the absence or presence of a functional mutation in the LDLR gene, differences in prognosis due to the type of mutation could influence commencement of lipid-lowering therapies in FH.38

APOB

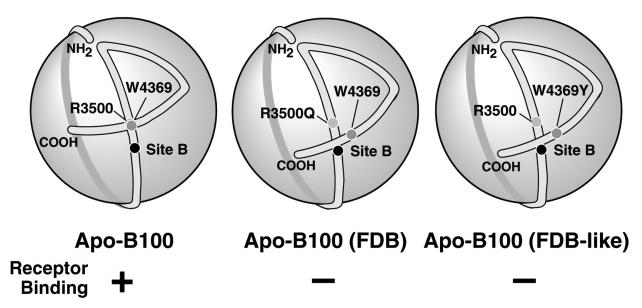

Like FH, FDB is characterised by elevated plasma concentrations of LDL cholesterol and apoB, normal triglyceride and high density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels, the presence of tendon xanthomas, and premature CAD.39–41 FDB is caused by mutations in the LDLR-binding region of apoB, causing defective binding and an accumulation of LDL in plasma (Figure 5). FDB cannot be clinically distinguished from heterozygous LDLR-FH, although the phenotype of FDB can be milder. In general, the hypercholesterolaemia is less severe and there appears to be a lower incidence of CAD in FDB compared to LDLR-FH.

Figure 5.

Model for the mechanism of FDB. Normally, the LDLR-binding region of apoB (site B) is available to interact with the LDLR; the interaction between arginine R3500 and tryptophan W4369 being particularly important (left). In FDB, mutations such as R3500Q alter the conformation of the C-terminal region of apoB, leading to occlusion of site B (centre). This model is supported by the finding that mutation of W4369 also disrupts LDLR binding (right). Excerpt reprinted with permission, from the Journal of Biological Chemistry, 276 c 2001 by The American Society for Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Inc.44

Several mutations in the LDLR-binding domain of apoB have been described that are associated with hypercholesterolaemia with an autosomal codominant inheritance pattern. The most common involves the substitution of a glutamine for arginine at position 3500 and affects about 1 in 500 individuals of European descent.42,43 By haplotype analysis, R3500Q is thought to originate from a single founder living in Europe 7000 years ago.44 Another missense mutation at the same position, where a tryptophan is substituted for arginine (R3500W), has been found in hyperlipidaemic patients of Chinese or Malay descent.45,46 Additional rarer mutations in exon 26 affecting surrounding residues (R3480W, R3480P, R3500L, R3531C and H3543Y) have been reported.36,45,47–49

Determining FDB mutation status is important, as FDB cannot be clinically distinguished from heterozygous FH without genetic testing. Genotyping for the R3500Q mutation is available at many specialist biochemical genetics laboratories. High resolution melting analysis has recently emerged as a sensitive method, capable of detecting all known APOB variants associated with FDB.50

PCSK9

Proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 (PCSK9), originally named neural apoptosis regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1), is a serine protease expressed in the body’s two main sites for lipoprotein metabolism: the liver and small intestine.51 Proprotein convertases are enzymes that cleave precursor proteins into their active forms. Linkage to chromosome 1p32, a locus containing the PCSK9 gene, was demonstrated in FH families not carrying LDLR or APOB mutations, and the subsequent discovery of PCSK9 missense mutations in two such families confirmed its importance in cholesterol metabolism, as the third gene responsible for dominant FH.52

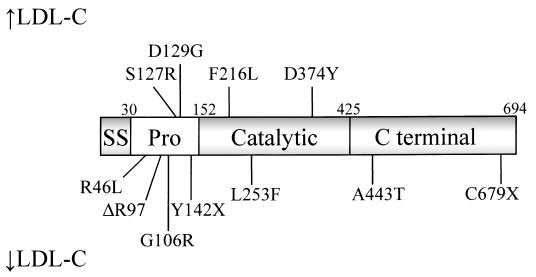

FH-causing mutations result in ‘gain-of-function’ and reduce the number of LDLRs on the cell surface and the amount of LDL they internalise.53 The frequency of PCSK9 mutations causing FH is unknown. Several PCSK9 mutations causing FH have been reported, including S127R, D129G, F216L and D374Y.54,55 Other mutations, N425S and R496W, have so far only been identified in families who also carry LDLR mutations.56 Individuals who are heterozygous for LDLR and PCSK9 mutations have ~50% higher plasma LDL cholesterol concentrations. Other mutations are associated with hypocholesterolaemia (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

PCSK9 and mutations associated with increased and decreased concentrations of LDL cholesterol. PCSK9 has a 30 amino acid signal sequence (SS), followed by a prodomain (Pro), catalytic domain and C-terminal domain. Reprinted from Trends in Biochemical Sciences, 32, Horton JD, Cohen, JC, Hobbs HH, Molecular biology of PCSK9: its role in LDL metabolism, 71–7, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.54

Recent studies have elucidated the function of PCSK9. It is secreted into plasma and binds directly to cell-surface LDLR, leading to endocytosis and intracellular degradation of the LDLR.57,58 PCSK9 has also been shown to induce degradation of the VLDL receptor (VLDLR) and apoE receptor 2 (APOER2), the closest family members of the LDLR.59 Serum concentrations of PCSK9 directly correlate with plasma cholesterol and LDL cholesterol levels.60 However, PCSK9 does not need to be secreted to have its effect on LDLR degradation. Cellular studies of two nonsecreted PCSK9 mutants causing FH, S127R and D129G, were shown to reduce LDLR expression.61

ARH

In very rare cases (<1:10 million) hypercholesterolaemia is inherited as an autosomal recessive trait.62 Although ARH was first described over 30 years ago,63 it was not until 2001 that mutations in adaptor protein ARH on chromosome 15 were identified as the cause.64 In affected subjects the LDLR is normal but accumulates at the cell surface, unable to be internalised. ARH interacts with the cytoplasmic tail of the LDLR and promotes LDLR clustering into clathrin coated pits.65

ARH presents with a clinical phenotype similar to homozygous FH, but is generally less severe and more responsive to lipid-lowering therapy.66 It is also more variable in presentation; ARH individuals have been diagnosed between ages 1 to 46 years and have total cholesterol from 9.6 to 27.1 mmol/L.67 In addition, most patients manifest large, bulky xanthomas from early childhood. ARH is more responsive to statins compared to homozygous FH, and this could be related to the observation that the LDLR pathway functions normally in cultured skin fibroblasts from ARH patients. This would allow increased removal of plasma LDL from extrahepatic tissues, and may also be related to the accelerated presence of xanthomas. Another adaptor protein Disabled-2 (Dab2) has recently been shown to mediate LDLR synthesis in skin broblasts from ARH patients.68

Monogenic Hypocholesterolaemia

Hypobetalipoproteinaemia is characterised by <5th percentile levels of plasma LDL cholesterol and apoB for age and sex, usually LDL cholesterol <1.8 mmol/L and apoB <0.5 g/L. Secondary causes of hypobetalipoproteinaemia include vegan diet, malnutrition, malabsorption, cachexia, hyperthyroidism, severe liver disease. Primary causes of hypobetalipoproteinaemia include FHBL, abetalipoproteinaemia (ABL), and chylomicron retention disease. Chylomicron retention disease, as the name suggests, relates to an inability of the gut to secrete chylomicrons, and as it is not a disorder of LDL metabolism, will not be discussed further in this review. More recently, nonsense variants in PCSK9 have been associated with hypocholesterolaemia.

APOB

FHBL is an autosomal codominant disorder of LDL deficiency, and is one of few monogenic disorders associated with protection against atherosclerosis. Characterised by plasma LDL and apoB concentrations <5th percentile for age and sex, it has a prevalence of ~1:3000.69

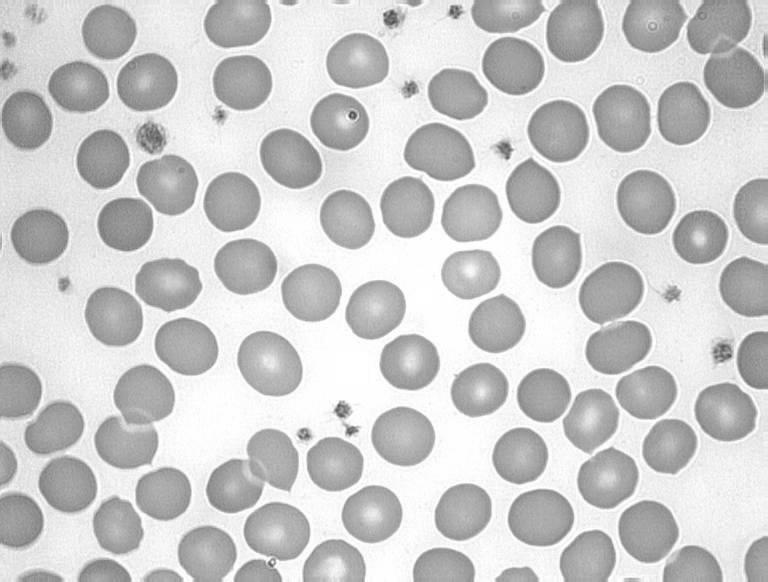

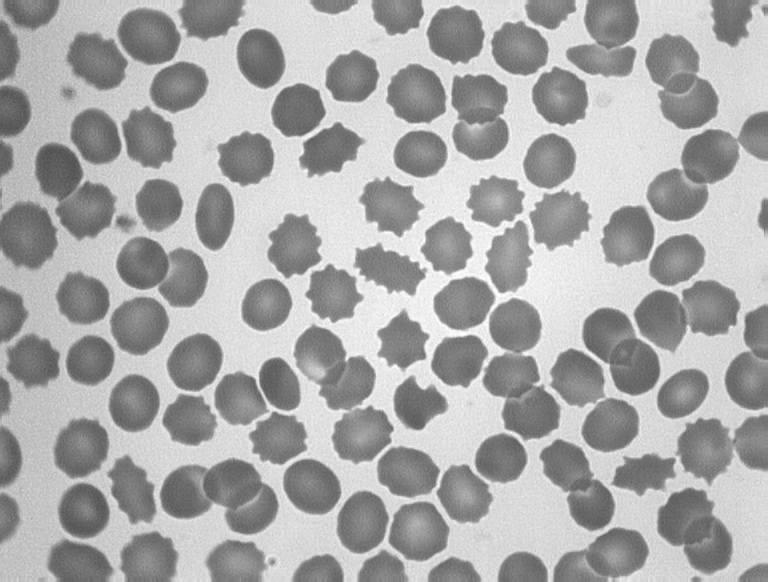

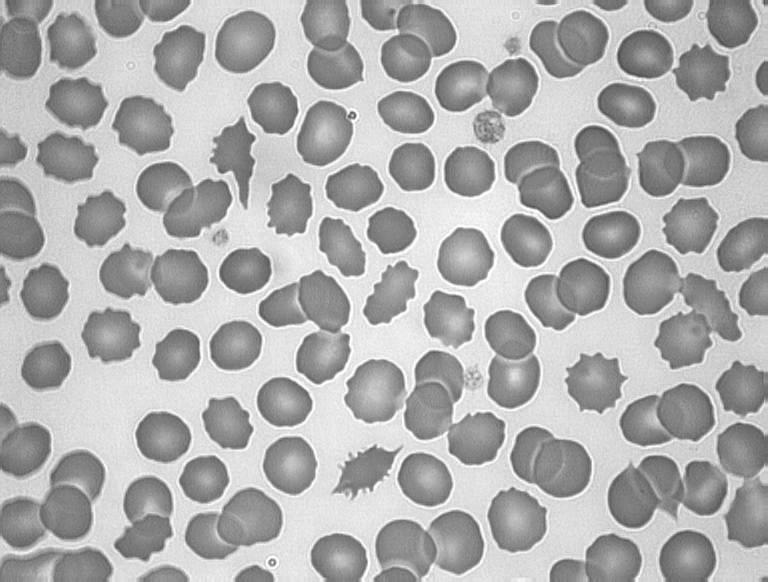

FHBL is caused by mutations in the APOB gene. FHBL heterozygotes are usually asymptomatic, and their low circulating plasma LDL concentrations, by reducing their cardiovascular disease risk, are thought to increase their lifespan by 10 years on average.70 FHBL heterozygotes were shown to have decreased arterial wall stiffness, indicative of cardiovascular protection.71 Emerging evidence suggests that FHBL subjects that are heterozygous for APOB mutations are at increased risk of developing fatty liver, and/or insulin resistance.72,73 Increased concentrations of serum liver enzymes ALT, AST and GGT are also observed in FHBL subjects compared to their unaffected relatives. Clinical manifestations in FHBL homozygotes vary, from no symptoms to severe gastrointestinal and neurological dysfunction, similar to that seen in ABL. This variation could relate to the severity of the APOB mutation(s) present, as well as other genetic or environmental factors. Acanthocytes are also observed in homozygous and occasionally in heterozygous FHBL (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Acanthocytosis in hypocholesterolaemia. A, Blood film from a normal subject; B, apoB-40.3 FHBL heterozygote; C, apoB-6.9 FHBL heterozygote; and D, subject with ABL.

About 60 mutations have been reported to date in APOB causing FHBL, most of which result in a truncated apoB molecule. ApoB truncations larger than apoB-29 (i.e. 29% of full-length apoB-100) can be detected in plasma by Western blotting, giving an indication of the target region of the APOB gene that needs to be sequenced in order to identify the mutation. However, truncations shorter than apoB-29 are not detectable in plasma and can only be identified by DNA sequencing. These very short apoBs appear to be unable to acquire sufficient lipid, which leads to their intracellular degradation rather than secretion.74

Stable isotope tracer methodology has been used in FHBL subjects to study the in vivo kinetics of apoB.75 The secretion rate of apoB species was found to be linked to the degree of truncation, equating to a 1.4% reduction in secretion for each 1% of apoB truncated.76 In addition, clearance of the truncated species apoB-75 and apoB-89, which contain the LDLR-binding domain, is faster than clearance of normal apoB-100.77,78 Based on the ‘ribbon and bow’ model of apoB structure on LDL particles (Figure 5), the absence of the carboxyl terminus of apoB-100 would result in enhanced receptor binding.47

We have used oral fat tolerance tests to study postprandial lipoprotein metabolism in FHBL heterozygotes with apoB truncations shorter than apoB-48.79 After baseline blood samples are taken following a 12 hour fast, subjects are given a fat load in the form of a milkshake, along with some vitamin A (retinol), and blood samples are taken 2-hourly over 10 hours. The retinol is used as a marker for chylomicron lipids, and we measured apoB-48 as an indicator of chylomicron and remnant particle number. By using a multicompartmental modelling approach, our results suggest that these FHBL subjects have reduced production of chylomicrons rather than increased clearance.

Our studies have discovered the first two missense mutations, L343V and R463W, in apoB causing FHBL.80,81 The N-terminal βα1 domain of apoB contains sequence elements that are important for interaction with its chaperone MTP and therefore triglyceride-rich lipoprotein assembly. This domain was sequenced in FHBL subjects in whom a truncated apoB was not detected by Western blotting. R463W and L343V were identified in large families with n=14 and n=10 heterozygous FHBL subjects respectively.80,81 The R463W kindred is of Christian Lebanese background and also includes two homozygous individuals who were the result of consanguineous unions. Both L343V and R463W occur within the putative MTP-binding region of apoB and track with the low-cholesterol phenotype within each family. L343 and R463 are also conserved among other mammalian species, further indicating the importance of these residues.

In vitro studies showed that the L343V and R463W mutations impaired secretion of apoB-100 and VLDL.81 Decreased secretion of mutant apoB-100 was also associated with increased endoplasmic reticulum retention and increased binding to MTP and BiP, a general molecular chaperone. Biochemical and biophysical analyses of apoB domain constructs showed that L343V and R463W altered folding of the alpha-helical domain within the N-terminus of apoB.

MTP

ABL, also known as Bassen-Kornzweig syndrome, is an extremely rare autosomal recessive disorder characterised by the absence of apoB containing lipoproteins in plasma.82,83

Patients with ABL show a range of clinical symptoms similar to homozygous FHBL, and often present in childhood with failure to thrive, fat malabsorption (steatorrhoea), and low plasma cholesterol and vitamin E levels. Symptoms can progress to include atypical retinitis pigmentosa and progressive spinocerebellar degeneration. Liver biopsies in ABL patients have shown steatosis, which may or may not be reflected in raised serum transaminases.82 ABL is caused by mutations in the MTP gene, and is distinguished from homozygous FHBL by the inheritance pattern; in ABL the parents will have normal lipids.

The human MTP gene is located on chromosome 4q22–24 and encodes the 894 amino acid MTP. MTP forms a heterodimer with the ubiquitous endoplasmic reticulum enzyme protein disulfide isomerase (PDI), and acts as a chaperone to facilitate apoB assembly into lipoproteins. MTP’s involvement in ABL was first reported in 1992, when MTP activity was not detected in intestinal biopsies of ABL subjects,84 and in the following year mutations in MTP causing ABL were described.85,86 About 30 ABL mutations occurring throughout the MTP gene have been described, including missense mutations R540H, G746E, and N780Y.87–89 MTP missense mutations affect either the PDI- or apoB-binding ability of MTP, or defective lipid transfer activity onto apoB, resulting in reduced secretion of apoB-containing lipoproteins.

Vitamin E, transported in plasma in association with the apoB-containing lipoproteins, is essential for neurological function. In ABL and homozygous FHBL, concentrations of the other fat-soluble vitamins (A, D and K) are reduced but, as they have alternate transport mechanisms, not to the same extent as vitamin E. High-dose vitamin E in ABL is recommended to inhibit progression of neurologic symptoms.40,82 In the absence of the apoB-containing lipoproteins vitamin E can be packaged into HDL. Supplementation with a combination of vitamins E and A has been shown to be effective in reducing, but not preventing, retinal degeneration.90 Recently, it was found that the human retina expresses MTP and apoB, suggesting that apoB-containing lipoprotein assembly is an important retinal function.91 Therefore, retinopathy in ABL could be due to defective MTP rather than vitamin E deficiency.

PCSK9

As described above, ‘gain-of-function’ missense mutations in PCSK9 cause hypercholesterolaemia. Other missense mutations are associated with lower cholesterol levels and possibly increased response to statin therapy.92 Two ‘loss-of-function’ nonsense variations, Y142X and C679X, were described in 2005, which occurred at a combined frequency of 2% in African Americans and reduced plasma LDL cholesterol by 40%.93 A reduction in PCSK9 activity would mean fewer LDLRs degraded, allowing more LDL particles to be cleared and a reduction in plasma LDL.

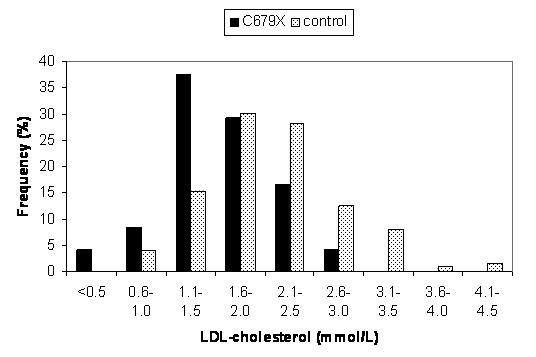

We genotyped for PCSK9 nonsense variants in a southern African population consisting of 653 young black females attending antenatal clinics in Zimbabwe.94 We did not find Y142X, suggesting a founder effect in the African American population. C679X occurred in 3.7% of subjects and was associated with a 27% reduction in plasma LDL cholesterol (1.6 ± 0.3 mmol/L vs 2.2 ± 0.7 mmol/L in non-carriers) (Figure 8). We also described the first homozygote for C679X, with the lowest LDL cholesterol of the studied population, at 0.4 mmol/L. This plasma LDL cholesterol concentration is comparable to that found in heterozygous FHBL, which suggests that homozygosity for PCSK9 nonsense mutations should be considered as a cause for severe hypocholesterolaemia.

Figure 8.

Plasma LDL cholesterol distributions in control subjects and subjects carrying the nonsense mutation of PCSK9, C679X. C679X was present in 24 out of 653 screened subjects, and associated with a 27% reduction in LDL. Reprinted from Atherosclerosis, 193, Hooper AJ, Marais AD, Tanyanyiwa DM, Burnett JR, The C679X mutation in PCSK9 is present and lowers blood cholesterol in a Southern African population, 445–8, Copyright 2007, with permission from Elsevier.94

PCSK9 mutations are interesting in that they illustrate the concept that time and not just LDL lowering plays an important role in the development of CHD.95 A 2 mmol/L decrease in LDL by statin treatment for five years only decreases the incidence of CHD by 40%. In contrast, PCSK9 nonsense mutation carriers have a 1 mmol/L reduction in plasma LDL cholesterol compared to non-carriers, but this is over a lifetime. A large study including 3363 African American subjects showed an 88% reduction in CHD risk in PCSK9 mutation carriers.96 Moreover, the only PCSK9 nonsense mutation carrier who developed CHD was obese, smoked, had hypertension with a family history of CHD, and died at age 68 years.

Conclusions

Heritable variation in plasma LDL cholesterol is conferred by sequence variation in various loci, with a small number of common and multiple rare gene variants contributing to the phenotype. Analysis of naturally occurring rare gene variants has been useful in identifying important domains governing the assembly and secretion of lipoproteins into plasma, and their metabolism and clearance.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Royal Perth Hospital Medical Research Foundation, the Raine Medical Research Foundation, the National Health & Medical Research Council (403908), and the National Heart Foundation of Australia (G 139 115).

Footnotes

Competing Interests: None declared.

References

- 1.Babiak J, Rudel LL. Lipoproteins and atherosclerosis. Baillieres Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1987;1:515–50. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(87)80022-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Randomised trial of cholesterol lowering in 4444 patients with coronary heart disease: the Scandinavian Simvastatin Survival Study (4S) Lancet. 1994;344:1383–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shepherd J. Preventing coronary artery disease in the West of Scotland: implications for primary prevention. Am J Cardiol. 1998;82:57T–59T. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(98)00728-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heller DA, de Faire U, Pedersen NL, Dahlen G, Mc Clearn GE. Genetic and environmental influences on serum lipid levels in twins. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1150–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304223281603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Olofsson SO, Asp L, Boren J. The assembly and secretion of apolipoprotein B-containing lipoproteins. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1999;10:341–6. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199908000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hussain MM, Iqbal J, Anwar K, Rava P, Dai K. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein: a multifunctional protein. Front Biosci. 2003;8:500–6. doi: 10.2741/1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JP, Hardman DA, Paulus HE. Heterogeneity of apolipoprotein B: isolation of a new species from human chylomicrons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1980;77:2465–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.77.5.2465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen SH, Habib G, Yang CY, Gu ZW, Lee BR, Weng SA, et al. Apolipoprotein B-48 is the product of a messenger RNA with an organ-specific in-frame stop codon. Science. 1987;238:363–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3659919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Powell LM, Wallis SC, Pease RJ, Edwards YH, Knott TJ, Scott J. A novel form of tissue-specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein-B48 in intestine. Cell. 1987;50:831–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. A receptor-mediated pathway for cholesterol homeostasis. Science. 1986;232:34–47. doi: 10.1126/science.3513311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Havel RJ, Kane JP. Structure and metabolism of plasma lipoproteins. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2705–16. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Libby P. Atherosclerosis: disease biology affecting the coronary vasculature. Am J Cardiol. 2006;98:3Q–9Q. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nathan BP, Bellosta S, Sanan DA, Weisgraber KH, Mahley RW, Pitas RE. Differential effects of apolipoproteins E3 and E4 on neuronal growth in vitro. Science. 1994;264:850–2. doi: 10.1126/science.8171342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Elzen P, Garg S, Leon L, Brigl M, Leadbetter EA, Gumperz JE, et al. Apolipoprotein-mediated pathways of lipid antigen presentation. Nature. 2005;437:906–10. doi: 10.1038/nature04001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fazekas F, Enzinger C, Ropele S, Schmidt H, Schmidt R, Strasser-Fuchs S. The impact of our genes: consequences of the apolipoprotein E polymorphism in Alzheimer disease and multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci. 2006;245:35–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.van Bockxmeer FM, Mamotte CD. Apolipoprotein epsilon 4 homozygosity in young men with coronary heart disease. Lancet. 1992;340:879–80. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)93288-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sing CF, Davignon J. Role of the apolipoprotein E polymorphism in determining normal plasma lipid and lipoprotein variation. Am J Hum Genet. 1985;37:268–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bennet AM, Di Angelantonio E, Ye Z, Wensley F, Dahlin A, Ahlbom A, et al. Association of apolipoprotein E genotypes with lipid levels and coronary risk. JAMA. 2007;298:1300–11. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.11.1300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reardon CA. Differential metabolism of apolipoprotein E isoproteins. J Lab Clin Med. 2002;140:301–2. doi: 10.1067/mlc.2002.129067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Garcia-Calvo M, Lisnock J, Bull HG, Hawes BE, Burnett DA, Braun MP, et al. The target of ezetimibe is Niemann-Pick C1-Like 1 (NPC1L1) Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:8132–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500269102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Knopfel M, Davies JP, Duong PT, Kvaerno L, Carreira EM, Phillips MC, et al. Multiple plasma membrane receptors but not NPC1L1 mediate high-affinity, ezetimibe-sensitive cholesterol uptake into the intestinal brush border membrane. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2007;1771:1140–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbalip.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Temel RE, Tang W, Ma Y, Rudel LL, Willingham MC, Ioannou YA, et al. Hepatic Niemann-Pick C1-like 1 regulates biliary cholesterol concentration and is a target of ezetimibe. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1968–78. doi: 10.1172/JCI30060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cohen JC, Pertsemlidis A, Fahmi S, Esmail S, Vega GL, Grundy SM, et al. Multiple rare variants in NPC1L1 associated with reduced sterol absorption and plasma low-density lipoprotein levels. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:1810–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508483103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hegele RA, Guy J, Ban MR, Wang J. NPC1L1 haplotype is associated with inter-individual variation in plasma low-density lipoprotein response to ezetimibe. Lipids Health Dis. 2005;4:16. doi: 10.1186/1476-511X-4-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Williams CM, Hegele RA. Compound heterozygosity for two non-synonymous polymorphisms in NPC1L1 in a non-responder to ezetimibe. Clin Genet. 2005;67:175–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00388.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein JL, Hobbs HH, Brown MS. Familial hypercholesterolemia. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2863–913. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khachadurian AK. The Inheritance of Essential Familial Hypercholesterolemia. Am J Med. 1964;37:402–7. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(64)90196-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Expression of the familial hypercholesterolemia gene in heterozygotes: mechanism for a dominant disorder in man. Science. 1974;185:61–3. doi: 10.1126/science.185.4145.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sudhof TC, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, Russell DW. The LDL receptor gene: a mosaic of exons shared with different proteins. Science. 1985;228:815–22. doi: 10.1126/science.2988123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.UCL LDLR Database. [(Accessed 12 December 2007)]; http://www.ucl.ac.uk/ldlr/LOVDv.1.1.0/

- 31.Iughetti L, Predieri B, Balli F, Calandra S. Rational approach to the treatment for heterozygous familial hypercholesterolemia in childhood and adolescence: a review. J Endocrinol Invest. 2007;30:700–19. doi: 10.1007/BF03347453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hobbs HH, Russell DW, Brown MS, Goldstein JL. The LDL receptor locus in familial hypercholesterolemia: mutational analysis of a membrane protein. Annu Rev Genet. 1990;24:133–70. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ge.24.120190.001025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Burnett JR, Ravine D, van Bockxmeer FM, Watts GF. Familial hypercholesterolaemia: a look back, a look ahead. Med J Aust. 2005;182:552–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.WHO/HGN/FH/CONS/992. Familial hypercholesterolemia. Report of a second WHO Consultation. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Risk of fatal coronary heart disease in familial hypercholesterolaemia. Scientific Steering Committee on behalf of the Simon Broome Register Group. BMJ. 1991;303:893–6. doi: 10.1136/bmj.303.6807.893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fouchier SW, Kastelein JJ, Defesche JC. Update of the molecular basis of familial hypercholesterolemia in The Netherlands. Hum Mutat. 2005;26:550–6. doi: 10.1002/humu.20256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leren TP. Cascade genetic screening for familial hypercholesterolemia. Clin Genet. 2004;66:483–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00320.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Aalst-Cohen ES, Jansen AC, Tanck MW, Defesche JC, Trip MD, Lansberg PJ, et al. Diagnosing familial hypercholesterolaemia: the relevance of genetic testing. Eur Heart J. 2006;27:2240–6. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Innerarity TL, Weisgraber KH, Arnold KS, Mahley RW, Krauss RM, Vega GL, et al. Familial defective apolipoprotein B-100: low density lipoproteins with abnormal receptor binding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1987;84:6919–23. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.19.6919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kane JP, Havel RJ. Disorders of the biogenesis and secretion of lipoproteins containing the B apolipoproteins. In: Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Sly WS, Valle D, Childs B, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, editors. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2001. pp. 2717–52. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Whitfield AJ, Barrett PHR, van Bockxmeer FM, Burnett JR. Lipid disorders and mutations in the APOB gene. Clin Chem. 2004;50:1725–32. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2004.038026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Innerarity TL, Mahley RW, Weisgraber KH, Bersot TP, Krauss RM, Vega GL, et al. Familial defective apolipoprotein B-100: a mutation of apolipoprotein B that causes hypercholesterolemia. J Lipid Res. 1990;31:1337–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Soria LF, Ludwig EH, Clarke HR, Vega GL, Grundy SM, McCarthy BJ. Association between a specific apolipoprotein B mutation and familial defective apolipoprotein B-100. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1989;86:587–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.2.587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Myant NB, Forbes SA, Day IN, Gallagher J. Estimation of the age of the ancestral arginine3500-->glutamine mutation in human apoB-100. Genomics. 1997;45:78–87. doi: 10.1006/geno.1997.4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gaffney D, Reid JM, Cameron IM, Vass K, Caslake MJ, Shepherd J, et al. Independent mutations at codon 3500 of the apolipoprotein B gene are associated with hyperlipidemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1995;15:1025–9. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.15.8.1025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tai DY, Pan JP, Lee-Chen GJ. Identification and haplotype analysis of apolipoprotein B-100 Arg3500-->Trp mutation in hyperlipidemic Chinese. Clin Chem. 1998;44:1659–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Boren J, Ekstrom U, Agren B, Nilsson-Ehle P, Innerarity TL. The molecular mechanism for the genetic disorder familial defective apolipoprotein B100. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:9214–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008890200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Soufi M, Sattler AM, Maerz W, Starke A, Herzum M, Maisch B, et al. A new but frequent mutation of apoB-100-apoB His3543Tyr. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:11–6. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2003.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wenham PR, Henderson BG, Penney MD, Ashby JP, Rae PW, Walker SW. Familial ligand-defective apolipoprotein B-100: detection, biochemical features and haplotype analysis of the R3531C mutation in the UK. Atherosclerosis. 1997;129:185–92. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(96)06029-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liyanage KE, Hooper AJ, Defesche JC, Burnett JR, van Bockxmeer FM. High-resolution melting analysis for detection of familial ligand-defective apolipoprotein B-100 mutations. Ann Clin Biochem. doi: 10.1258/acb.2007.007077. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Seidah NG, Benjannet S, Wickham L, Marcinkiewicz J, Jasmin SB, Stifani S, et al. The secretory proprotein convertase neural apoptosis-regulated convertase 1 (NARC-1): liver regeneration and neuronal differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:928–33. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0335507100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abifadel M, Varret M, Rabes JP, Allard D, Ouguerram K, Devillers M, et al. Mutations in PCSK9 cause autosomal dominant hypercholesterolemia. Nat Genet. 2003;34:154–6. doi: 10.1038/ng1161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maxwell KN, Fisher EA, Breslow JL. Overexpression of PCSK9 accelerates the degradation of the LDLR in a post-endoplasmic reticulum compartment. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:2069–74. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0409736102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Horton JD, Cohen JC, Hobbs HH. Molecular biology of PCSK9: its role in LDL metabolism. Trends Biochem Sci. 2007;32:71–7. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2006.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lambert G. Unravelling the functional significance of PCSK9. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2007;18:304–9. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3281338531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pisciotta L, Priore Oliva C, Cefalu AB, Noto D, Bellocchio A, Fresa R, et al. Additive effect of mutations in LDLR and PCSK9 genes on the phenotype of familial hypercholesterolemia. Atherosclerosis. 2006;186:433–40. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2005.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Qian YW, Schmidt RJ, Zhang Y, Chu S, Lin A, Wang H, et al. Secreted proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin-type 9 downregulates low-density lipoprotein receptor through receptor-mediated endocytosis. J Lipid Res. 2007;48:1488–98. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M700071-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zhang DW, Lagace TA, Garuti R, Zhao Z, McDonald M, Horton JD, et al. Binding of proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 to epidermal growth factor-like repeat A of low density lipoprotein receptor decreases receptor recycling and increases degradation. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:18602–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702027200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Poirier S, Mayer G, Benjannet S, Bergeron E, Marcinkiewicz J, Nassoury N, et al. The proprotein convertase PCSK9 induces the degradation of LDLR and its closest family members VLDLR and APOER2. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2363–72. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708098200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alborn WE, Cao G, Careskey HE, Qian YW, Subramaniam DR, Davies J, et al. Serum proprotein convertase subtilisin kexin type 9 is correlated directly with serum LDL cholesterol. Clin Chem. 2007;53:1814–9. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2007.091280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Homer VM, Marais AD, Charlton F, Laurie AD, Hurndell N, Scott R, et al. Identification and characterization of two non-secreted PCSK9 mutants associated with familial hypercholesterolemia in cohorts from New Zealand and South Africa. Atherosclerosis. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.07.022. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Soutar AK, Naoumova RP. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. Semin Vasc Med. 2004;4:241–8. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-861491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Khachadurian AK, Uthman SM. Experiences with the homozygous cases of familial hypercholesterolemia. A report of 52 patients. Nutr Metab. 1973;15:132–40. doi: 10.1159/000175431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Garcia CK, Wilund K, Arca M, Zuliani G, Fellin R, Maioli M, et al. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia caused by mutations in a putative LDL receptor adaptor protein. Science. 2001;292:1394–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1060458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Garuti R, Jones C, Li WP, Michaely P, Herz J, Gerard RD, et al. The modular adaptor protein autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia (ARH) promotes low density lipoprotein receptor clustering into clathrin-coated pits. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:40996–1004. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509394200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naoumova RP, Neuwirth C, Lee P, Miller JP, Taylor KG, Soutar AK. Autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia: long-term follow up and response to treatment. Atherosclerosis. 2004;174:165–72. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2004.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Soutar AK, Naoumova RP, Traub LM. Genetics, clinical phenotype, and molecular cell biology of autosomal recessive hypercholesterolemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:1963–70. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000094410.66558.9A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Eden ER, Sun XM, Patel DD, Soutar AK. Adaptor protein disabled-2 modulates low density lipoprotein receptor synthesis in fibroblasts from patients with autosomal recessive hypercholesterolaemia. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2751–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Welty FK, Lahoz C, Tucker KL, Ordovas JM, Wilson PW, Schaefer EJ. Frequency of apoB and apoE gene mutations as causes of hypobetalipoproteinemia in the Framingham offspring population. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1998;18:1745–51. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.18.11.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Glueck CJ, Gartside P, Fallat RW, Sielski J, Steiner PM. Longevity syndromes: familial hypobeta and familial hyperalpha lipoproteinemia. J Lab Clin Med. 1976;88:941–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sankatsing RR, Fouchier SW, de Haan S, Hutten BA, de Groot E, Kastelein JJ, et al. Hepatic and cardiovascular consequences of familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:1979–84. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000176191.64314.07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schonfeld G, Patterson BW, Yablonskiy DA, Tanoli TS, Averna M, Elias N, et al. Fatty liver in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia: triglyceride assembly into VLDL particles is affected by the extent of hepatic steatosis. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:470–8. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M200342-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tanoli T, Yue P, Yablonskiy D, Schonfeld G. Fatty liver in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia: roles of the APOB defects, intra-abdominal adipose tissue, and insulin sensitivity. J Lipid Res. 2004;45:941–7. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300508-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yao ZM, Blackhart BD, Linton MF, Taylor SM, Young SG, McCarthy BJ. Expression of carboxyl-terminally truncated forms of human apolipoprotein B in rat hepatoma cells. Evidence that the length of apolipoprotein B has a major effect on the buoyant density of the secreted lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3300–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Burnett JR, Barrett PHR. Apolipoprotein B metabolism: tracer kinetics, models, and metabolic studies. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2002;39:89–137. doi: 10.1080/10408360208951113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Parhofer KG, Barrett PHR, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Schonfeld G. Positive linear correlation between the length of truncated apolipoprotein B and its secretion rate: in vivo studies in human apoB-89, apoB-75, apoB-54.8, and apoB-31 heterozygotes. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:844–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Krul ES, Parhofer KG, Barrett PHR, Wagner RD, Schonfeld G. ApoB-75, a truncation of apolipoprotein B associated with familial hypobetalipoproteinemia: genetic and kinetic studies. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:1037–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Parhofer KG, Barrett PHR, Bier DM, Schonfeld G. Lipoproteins containing the truncated apolipoprotein, Apo B-89, are cleared from human plasma more rapidly than Apo B-100-containing lipoproteins in vivo. J Clin Invest. 1992;89:1931–7. doi: 10.1172/JCI115799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hooper AJ, Robertson K, Barrett PH, Parhofer KG, van Bockxmeer FM, Burnett JR. Postprandial lipoprotein metabolism in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1474–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burnett JR, Shan J, Miskie BA, Whitfield AJ, Yuan J, Tran K, et al. A novel nontruncating APOB gene mutation, R463W, causes familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:13442–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M300235200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Burnett JR, Zhong S, Jiang ZG, Hooper AJ, Fisher EA, McLeod RS, et al. Missense mutations in APOB within the βα1 domain of human APOB-100 result in impaired secretion of ApoB and ApoB-containing lipoproteins in familial hypobetalipoproteinemia. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:24270–83. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M702442200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Berriot-Varoqueaux N, Aggerbeck LP, Samson-Bouma M, Wetterau JR. The role of the microsomal triglygeride transfer protein in abetalipoproteinemia. Annu Rev Nutr. 2000;20:663–97. doi: 10.1146/annurev.nutr.20.1.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hooper AJ, van Bockxmeer FM, Burnett JR. Monogenic hypocholesterolaemic lipid disorders and apolipoprotein B metabolism. Crit Rev Clin Lab Sci. 2005;42:515–45. doi: 10.1080/10408360500295113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Wetterau JR, Aggerbeck LP, Bouma ME, Eisenberg C, Munck A, Hermier M, et al. Absence of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein in individuals with abetalipoproteinemia. Science. 1992;258:999–1001. doi: 10.1126/science.1439810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sharp D, Blinderman L, Combs KA, Kienzle B, Ricci B, Wager-Smith K, et al. Cloning and gene defects in microsomal triglyceride transfer protein associated with abetalipoproteinaemia. Nature. 1993;365:65–9. doi: 10.1038/365065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Shoulders CC, Brett DJ, Bayliss JD, Narcisi TM, Jarmuz A, Grantham TT, et al. Abetalipoproteinemia is caused by defects of the gene encoding the 97 kDa subunit of a microsomal triglyceride transfer protein. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:2109–16. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.12.2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ohashi K, Ishibashi S, Osuga J, Tozawa R, Harada K, Yahagi N, et al. Novel mutations in the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein gene causing abetalipoproteinemia. J Lipid Res. 2000;41:1199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rehberg EF, Samson-Bouma ME, Kienzle B, Blinderman L, Jamil H, Wetterau JR, et al. A novel abetalipoproteinemia genotype. Identification of a missense mutation in the 97-kDa subunit of the microsomal triglyceride transfer protein that prevents complex formation with protein disulfide isomerase. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:29945–52. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.47.29945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang J, Hegele RA. Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (MTP) gene mutations in Canadian subjects with abetalipoproteinemia. Hum Mutat. 2000;15:294–5. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-1004(200003)15:3<294::AID-HUMU14>3.0.CO;2-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Chowers I, Banin E, Merin S, Cooper M, Granot E. Long-term assessment of combined vitamin A and E treatment for the prevention of retinal degeneration in abetalipoproteinaemia and hypobetalipoproteinaemia patients. Eye. 2001;15:525–30. doi: 10.1038/eye.2001.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Li CM, Presley JB, Zhang X, Dashti N, Chung BH, Medeiros NE, et al. Retina expresses microsomal triglyceride transfer protein: implications for age-related maculopathy. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:628–40. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400428-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Berge KE, Ose L, Leren TP. Missense mutations in the PCSK9 gene are associated with hypocholesterolemia and possibly increased response to statin therapy. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2006;26:1094–100. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000204337.81286.1c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Cohen J, Pertsemlidis A, Kotowski IK, Graham R, Garcia CK, Hobbs HH. Low LDL cholesterol in individuals of African descent resulting from frequent nonsense mutations in PCSK9. Nat Genet. 2005;37:161–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hooper AJ, Marais AD, Tanyanyiwa DM, Burnett JR. The C679X mutation in PCSK9 is present and lowers blood cholesterol in a Southern African population. Atherosclerosis. 2007;193:445–8. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2006.08.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Biomedicine. Lowering LDL--not only how low, but how long? Science. 2006;311:1721–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1125884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH, Jr, Hobbs HH. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1264–72. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa054013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]