Abstract

Background

Despite its effectiveness, methadone maintenance is rarely provided in American correctional facilities. This study is the first randomized clinical trial in the US to examine the effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment provided to prisoners with pre-incarceration heroin addiction.

Methods

A three-group randomized controlled trial was conducted between September 2003 and June 2005. Two hundred-eleven Baltimore pre-release inmates who were heroin dependent during the year prior to incarceration were enrolled in this study. Participants were randomly assigned to the following: Counseling Only: counseling in prison, with passive referral to treatment upon release (n = 70); Counseling + Transfer: counseling in prison with transfer to methadone maintenance treatment upon release (n = 70); and Counseling + Methadone: methadone maintenance and counseling in prison, continued in a community-based methadone maintenance program upon release (n = 71).

Results

Two hundred participants were located for follow-up interviews and included in the current analysis. The percentages of participants in each condition that entered community-based treatment were, respectively, Counseling Only 7.8%, Counseling + Transfer 50.0%, and Counseling + Methadone 68.6%, p < .05. All pairwise comparisons were statistically significant, (all ps < .05). The percentage of participants in each condition that tested positive for opioids at one month post-release were, respectively, Counseling Only 62.9%, Counseling + Transfer 41.0%, and Counseling + Methadone 27.6%, p < .05, with the Counseling Only group significantly more likely to test positive than the Counseling + Methadone group.

Conclusions

Methadone maintenance initiated prior to or immediately after release from prison appears to have beneficial short-term impact on community treatment entry and heroin use. This intervention may be able to fill an urgent treatment need for prisoners with heroin addiction histories.

Keywords: methadone maintenance, drug abuse treatment, prisoners, heroin addiction

1. Introduction

Heroin dependence is a significant problem among individuals entering jails and prisons throughout the world. In the United States, approximately 12–15% of these individuals have histories of heroin addiction (Chaiken, 2000; Karberg and James, 2005); epidemiological studies of prisoners in England and Wales (Strang et al., 2006) and Italy (Rezza et al., 2005) report lifetime prevalence rates of 58% and 34% respectively; and prisoners in the United States, Australia, and various European nations have higher rates of heroin use than the general population (McSweeney et al., 2002). Furthermore, re-addiction usually occurs within one month of release (Kinlock et al. 2002; Maddux and Desmond, 1981; Nurco et al. 1991). Although addiction is associated with a high risk of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV; Chitwood et al.1998; Inciardi et al. 1998), hepatitis B and C infections (Edlin, 2002; Fuller et al. 1999; Hagan et al. 2002), overdose death (Mark et al. 2001; Weatherburn and Lind, 1999), criminal activity (Chaiken and Chaiken, 1990; Kinlock et al. 2003; Nurco, 1998), and re-incarceration (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration (SAMHSA), 2000), most reentering prisoners do not receive substance abuse treatment while incarcerated or upon release (Inciardi et al. 1998; McSweeney et al., 2002; Smith-Rohrberg et al. 2004). Thus, there is an urgent need to evaluate promising treatments spanning incarceration and the community (Leukefeld et al. 2002; Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), 2001a).

Despite extensive evidence of methadone treatment’s effectiveness in community-based settings (Ball and Ross, 1991; Dole and Nyswander, 1965; Jaffe and Senay, 1971; Johnson et al. 2000; Joseph et al. 2000; Platt et al. 1998) and its widespread use in correctional facilities throughout the world (Jurgens, 2004; McSweeney et al. 2002), provided in 23 countries (Dolan, 2001; European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), 2002), methadone treatment is rarely offered in U.S. correctional facilities. In the U.S., there are two types of correctional facilities—jails, typically administered by city or county governments, holding short-term inmates awaiting trials or serving shorter sentences and prisons, generally administered by state and federal governments and holding longer-term inmates serving sentences longer than one year. In 1968, Dole and colleagues (Dole et al. 1969) conducted the first study of methadone treatment in an American correctional facility. In this study, 28 heroin-addicted pre-release New York City jail inmates were randomly assigned to methadone maintenance 10 days prior to release, with post-release assignment to continued treatment in the community or to an untreated control condition. Participants receiving methadone had lower re-addiction and re-incarceration rates at 7–10 months post-release than controls. Subsequently, New York City’s jail began a methadone program in 1987. This program provides methadone treatment to newly-arrived jail inmates who are either addicted to heroin or who are receiving methadone maintenance treatment at the time of incarceration. This program has been effective in facilitating post-release treatment attendance and in reducing re-incarceration (Magura et al. 1993; Tomasino et al. 2001).

Baltimore’s serious, persistent health and crime problems associated with heroin addiction (Fuller et al. 1999; Gray and Wish, 2001; Kinlock et al. 2002; Wish and Yacoubian, 2001) led to a small-scale study of prison-initiated opioid maintenance treatment with Levo-alpha-acetylmethadol (LAAM) for male inmates with pre-incarceration heroin dependence (Kinlock et al. 2002). Results indicated that it was feasible to enroll such inmates in maintenance treatment, and that this approach facilitated treatment entry upon release to the community (Kinlock et al. 2002, 2005a, 2005b).

The present study is, to our knowledge, the first randomized clinical trial in the United States to examine the effectiveness of prison (as opposed to jail)-initiated methadone (Kinlock et al. 2005b). It was conducted to assess the extent to which initiating methadone in prison prior to release with continued treatment in the community would be more efficacious than initiating methadone treatment in the community or simply providing counseling in prison with a passive referral to treatment upon release. Determining the differences in efficacy among these conditions would provide important data to clinicians, policy makers, and correctional officials. The present report focuses on outcomes at one-month post-release – the time point by which an estimated 66–78% of untreated prisoners with heroin addiction histories typically relapse (Maddux & Desmond, 1981; Nurco et al., 1991).

2. Method

2.1 Participants

Participants were recruited between September 2003 and June 2005 from male prisoners in a Baltimore pre-release facility who had been incarcerated at least one year and would have met criteria for methadone maintenance treatment at the time of their incarceration. Eligibility criteria were: 1) three to six months before anticipated release from prison; 2) meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) criteria of heroin dependence at time of incarceration and being physiologically dependent during the year prior to incarceration; 3) suitability for methadone maintenance as determined by medical evaluation; 4) willingness to enroll in a prison-based methadone maintenance treatment program; and, 5) residing in Baltimore following release. Individuals who did not meet the heroin-dependence criterion were eligible if they were enrolled in an opioid treatment program in the year before incarceration. Individuals were excluded from participation if they had one or more of the following conditions: 1) renal failure; 2) liver failure; 3) pending/unadjudicated charges, which could have resulted in transfer to another correctional facility and/or additional prison time; and 4) a pending parole hearing.

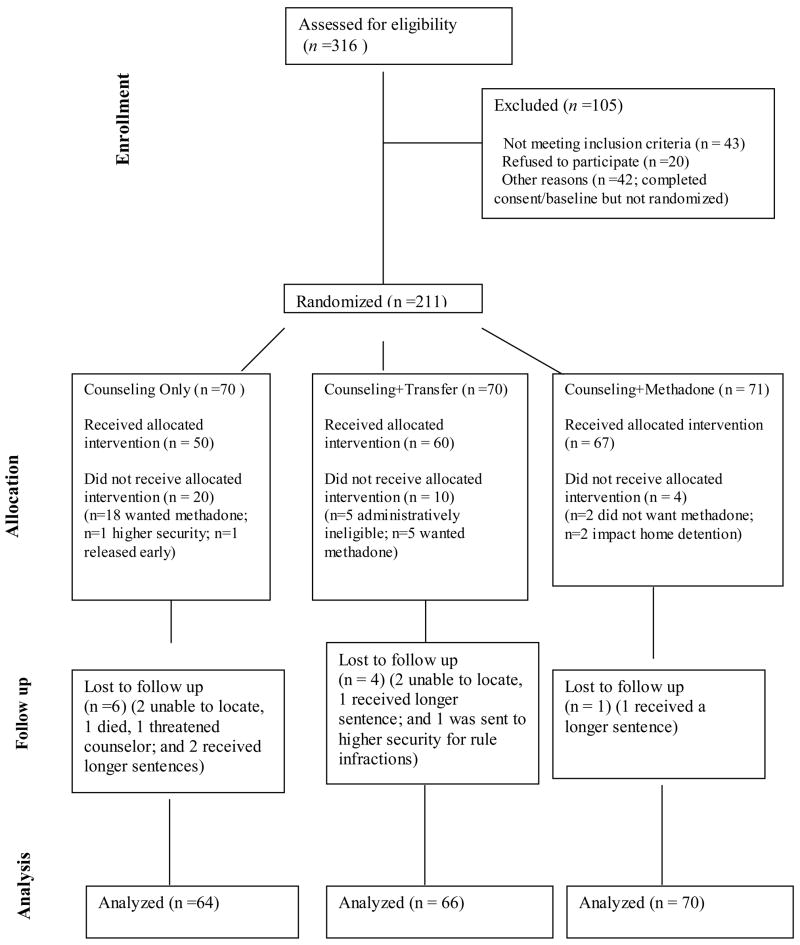

Participants were recruited by group orientation sessions (in which research staff informed potential participants about the nature of the study and requirements for participation) and word-of-mouth. Inmates willing to enroll were individually screened for participation by study personnel. Inmates still eligible at this point then met with research staff for informed consent and completed baseline assessments (see section 2.4, below). Final consent and determination for study enrollment was made by the methadone program’s medical director following a physical examination (See Consort Diagram, Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Consort Diagram of Recruitment

Of the 253 individuals who were consented and completed a baseline assessment, the 211 who were randomized were compared on the baseline variables presented in Table 1 with the 42 who became ineligible for study participation. There was only one statistically significant difference between the two groups. Individuals who were randomized reported committing crime on more days in the last 30 days in the community before the current incarceration than did those not randomized (p =.006).

Table 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Categorical Variables | Counseling Only (n=64) | Counseling + Transfer (n=66) | Counseling + Methadone (n=70) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Race | ||||||

| African American | 42 (65.6) | 48 (72.7) | 50 (71.4) | |||

| Caucasian | 20 (31.3) | 13 (19.7) | 14 (20.0) | |||

| Other | 2 (3.1) | 5 (7.6) | 6 (8.6) | |||

| Prior drug treatment | 44 (68.8) | 48 (72.7) | 51 (72.9) | |||

| Prior methadone treatment | 15 (23.4) | 17 (25.8) | 15 (21.4) | |||

|

| ||||||

| Continuous Variables | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

|

| ||||||

| Age | 40.9 | 7.6 | 40.3 | 7.0 | 39.8 | 7.0 |

| Education | 10.9 | 2.1 | 11.1 | 1.6 | 10.9 | 1.7 |

| Age first marijuana use | 13.8 | 4.4 | 14.0 | 3.1 | 14.3 | 3.7 |

| Age first cocaine use | 21.8 | 8.3 | 22.3 | 6.7 | 21.1 | 7.0 |

| Age first heroin use | 19.2 | 5.3 | 18.7 | 4.8 | 18.0 | 4.8 |

| Heroin use daysa | 27.1 | 7.8 | 27.9 | 6.1 | 26.6 | 8.9 |

| Cocaine use daysa | 20.3 | 12.7 | 16.9 | 13.1 | 17.3 | 13.9 |

| Crime daysa | 23.2 | 11.6 | 26.4 | 8.9 | 25.1 | 10.1 |

| Age first crime | 13.8 | 5.0 | 13.8 | 4.9 | 13.4 | 3.8 |

| Age first arrested | 15.8 | 4.9 | 17.3 | 5.5 | 16.7 | 5.9 |

| Age first incarcerated | 19.8 | 6.8 | 22.6 | 8.5 | 19.7 | 7.4 |

| Lifetime incarcerated | 7.5 | 5.3 | 6.0 | 4.3 | 7.5 | 5.4 |

Past 30 days in the community prior to the current incarceration.

2.2 Study Design

The study was a three-group randomized controlled trial. Participants were assigned (see Figure 1) to one of three treatment conditions based on a block randomization procedure, such that in a block of nine participants, three participants were assigned at random to each of the three treatment conditions. Assessments were conducted at baseline and at one month following release from prison. The study protocol was approved by Friends Research Institute’s institutional review board (IRB) and the trial was monitored by an external data and safety monitoring board (DSMB).

2.3 Interventions

Following initial screening, informed consent, and physical examination, consenting participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions: Counseling Only – counseling in prison, with passive referral to treatment upon release; Counseling + Transfer – counseling in prison, with immediate access to methadone maintenance treatment upon release from prison, but no maintenance treatment in prison; or, Counseling + Methadone – initiation of methadone maintenance and counseling in prison, continued in a community-based methadone maintenance program administered by the same provider immediately upon release from prison. All participants received an individual intake by the study counselor and were subsequently scheduled to receive, within treatment condition, 12 weekly sessions of group-based education and discussion on relapse and overdose prevention, cocaine and alcohol abuse, and other re-entry issues. Immediately prior to release, all participants were scheduled to meet with the study’s counselor to discuss plans for release, including housing, employment concerns, and treatment options. Counseling Only participants were informed at release by treatment staff to seek drug abuse treatment in the community in any of the publicly funded drug abuse programs in Baltimore according to programs’ standard admission procedures.

At the start of the study, the methadone induction protocol for the Counseling + Methadone Condition participants was to begin at 10 mg of methadone and increase by 5 mg every third day. However, because the first two participants reported some drowsiness after the first several doses, the protocol was changed with the approval of the IRB. Counseling + Methadone Condition participants subsequently began methadone dosing at 5 mg and increased by 5 mg every eighth day during incarceration to a target dose of 60 mg. These slow induction rates were followed because participants were not tolerant to opioids at the time medication was initiated. A target dose of 60 mg was used to facilitate tapering off methadone in the event participants are transferred to other prisons and/or receive additional prison time. At release, Counseling + Methadone Condition participants were advised by treatment staff to report to the in-prison treatment program’s community-based facility as soon as possible; at that time, they were informed that if they reported within 10 days following release from prison, they would be guaranteed admission into the treatment program’s methadone treatment program. Once they arrived at this facility, dosage could be increased or decreased based on clinical need.

At release from prison, participants in the Counseling + Transfer condition were advised by treatment staff to report to the in-prison treatment program’s community-based facility, where they would initiate methadone treatment at the same induction rate followed for Counseling + Methadone participants while these participants were in prison. Participants in the Counseling + Transfer and Counseling + Methadone conditions who missed 3 consecutive days of medication at any time were required to meet with the study physician to adjust dosage if necessary. Participants who failed to meet with the physician or requested to discontinue treatment were discharged from treatment according to the treatment center’s protocol.

2.4 Assessments

Participants were administered at baseline the Addiction Severity Index (ASI; McLellan et al. 1992), which assesses problem severity in seven areas: alcohol use, drug use, medical, psychiatric, family/social, employment, and legal functioning. Follow-up assessments scheduled one month after release from prison consisted of treatment record review; one urine drug test for opioids, cocaine, and other illicit drugs, and an interview addressing heroin use, cocaine use, and criminal activity.

2.5 Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measures examined during the one-month follow-up period were admission to drug abuse treatment in the community and urine opioid test results. The secondary outcome measures were: 1) self-reported heroin use; 2) self-reported cocaine use; and 3) urine drug test results for cocaine. Data on drug abuse treatment status were obtained from treatment program records and participant self-report. Urine samples were tested using the enzyme-multiplied immunoassay technique for opioids and cocaine, with cutoff calibration concentrations of 300 μg/mL for both morphine and benzoylecgonine. Frequency of self-reported heroin and cocaine use were obtained from the ASI. Due to the relatively large number of participants who reported zero days of drug use, both self-reported heroin and cocaine days were collapsed into dichotomous variables (any v. none) for the purpose of analysis.

2.6 Hypotheses

It was hypothesized that the Counseling + Methadone condition would have more favorable outcomes than both the Counseling + Transfer and Counseling Only conditions with respect to: 1) entry into community-based drug abuse treatment following release from prison; 2) heroin use; and 3) cocaine use. Furthermore, the Counseling + Transfer condition would have more favorable outcomes than the Counseling Only condition.

2.7 Statistical Analysis

Logistic regression analysis (Agresti, 1990; Hosmer and Lemeshow, 1989) was used to compare the three treatment conditions on both the primary and secondary outcome variables. Wald χ2 is reported for the overall test comparing the three conditions, as well as for the pairwise comparisons between the different treatment conditions.

3.0 RESULTS

3.1 Participant Characteristics

One-month post-release follow-up assessments were conducted on 200, or 96.2% of the 208 participants due for this assessment; 64 of 70 (91.4%) in the Counseling Only condition, 66 of 68 (97.1%) in the Counseling + Transfer condition, and 70 of 70 (100.0%) in the Counseling + Methadone condition. As shown in Table 1, most participants in each of the three study conditions were African American, did not complete high school, and were between 35 and 45 years of age. All participants had been previously incarcerated, whereas at least two-thirds in each study condition had one or more previous substance abuse treatment episodes, with less than one-third reported having been in methadone maintenance treatment. Participants in each condition, on average, began heroin use in their late teens, generally 4–5 years after the onset of criminal activity. In the 30 days prior to their current incarceration, participants in each condition reported, on average, using heroin and committing crime nearly every day. There were no statistically significant differences between the three treatment conditions on the variables listed in Table 1.

3.2 Primary Outcomes

3.2.1 Community Treatment Entry

The percentage of participants in each condition that entered community based treatment were, respectively, Counseling Only 7.8%, Counseling + Transfer 50.0%, and Counseling + Methadone 68.6%, p < .05. All pairwise comparisons were statistically significant, all ps < .05.

3.2.2 Urine Opioid Drug Test Results

The percentage of participants in each condition that tested positive for opioids were, respectively, Counseling Only 62.9%, Counseling + Transfer 41.0%, and Counseling + Methadone 27.6%. There was a statistically significant difference overall in the Condition by positive opioid test effect, p < .05. In terms of pairwise comparisons, only the Counseling Only group was significantly more likely to test positive than the Counseling + Methadone group.

3.3 Secondary Outcomes

3.3.1 Urine Cocaine Drug Test Results

The overall model for cocaine urine testing results was not significant [χ2 = 3.39, p = .18]. The percent of participants in each condition who tested positive were, respectively, Counseling Only, 63.9%, Counseling + Transfer, 48.7%, and Counseling + Methadone, 44.8%.

3.3.2 Self-Reported Heroin Use

The overall model for heroin use was significant [χ2 = 7.38, p = .025]. The percentage of participants in each condition that reported using heroin on one or more days during the one-month period following their release from prison were, respectively, Counseling Only, 60.3%, Counseling + Transfer, 39.4%, and Counseling + Methadone, 40.0%. Counseling Only participants were more likely to report heroin use compared to both Counseling + Methadone (p = .020) and Counseling + Transfer (p = .018) participants. There was no significant difference between Counseling + Transfer and Counseling + Methadone participants, p > .05.

3.3.3. Self-Reported Cocaine Use

As with urine cocaine testing, the overall model for self-report was not significant [χ2 = 3.20, p = .20]. The percentage of participants in each condition that reported using cocaine on one or more days during the one-month period after their release from prison were, respectively, Counseling Only, 34.9%, Counseling + Transfer, 22.7%, and Counseling + Methadone, 22.9%.

4.0 Serious Adverse Events

There were 10 serious adverse events (SAEs), including 9 hospitalizations (3 in Counseling + Transfer and 6 in the Counseling + Methadone condition) and one narcotic overdose death (Counseling Only). Only one of the SAEs (brief hospitalization for constipation in the Counseling + Methadone group) was considered possibly-related to study participation. The remaining five hospitalizations in for the Counseling + Methadone condition included two for heart disease and one each for pneumonia, alcohol detoxification, and kidney disease. The three hospitalizations for the Counseling + Transfer condition involved one for high blood pressure, one for psychiatric problems, and one for back pain.

4.0 Comment

4.1 Outcomes at One-Month Follow-Up

This study is the first randomized clinical trial in the US to examine methadone maintenance treatment provided to prisoners with pre-incarceration histories of heroin addiction. The current investigation, involving 200 participants, indicates that offering methadone maintenance treatment in prison was associated with greater treatment entry in the community within one month post-prison release than either counseling only with passive referral upon release or a guaranteed methadone treatment admission upon release. Compared to Counseling Only participants, those participants who received methadone in prison were over eight times more likely to enter drug abuse treatment following release. These findings confirm and extend the results of our previous study with LAAM which showed superior treatment entry for pre-release participants who started LAAM prior to release as compared to controls (Kinlock et al. 2005a). These findings are of significance because increased treatment entry and retention for heroin-dependent individuals has been shown to be related to reduced heroin use and criminal activity (Anglin, 1988; Hser et al. 2001; Kinlock and Gordon, 2006).

In terms of heroin use confirmed by urine drug test results at follow-up, while there was no difference between methadone initiated in prison and upon release, both of these conditions were superior to counseling only in prison. Counseling Only participants were over twice as likely as Counseling + Methadone participants to test positive for opioids at one-month post-release. These findings are also of importance as increased frequency of heroin use is associated with increased frequency of criminal behavior (Chaiken and Chaiken, 1990; Kinlock et al. 2003; Nurco, 1998) as well as greater likelihood of incarceration (Hanlon et al. 1998; SAMHSA, 2000), HIV and hepatitis B and C infections (Chitwood et al. 1998; Edlin, 2002; Fuller et al. 1999; Hagan et al. 2002; Inciardi et al. 1998), and overdose (Mark et al. 2001; Weatherburn and Lind, 1999). In Dole and colleagues (1969) study of pre-release jail inmates, individuals who received methadone prior to release had lower rates of both heroin addiction and re-incarceration as compared to controls.

It is not entirely surprising that cocaine use did not differ among the groups. Methadone treatment has been shown to be more effective in treating opioid use than cocaine use (Platt et al. 1998). In a recent study, individuals treated with methadone only (without counseling) as compared to waiting list controls, were found to have significantly reduced heroin, but not cocaine use (Schwartz et al. 2006). Effective strategies are needed to assist methadone patients reduce their cocaine use (Platt et al. 1998).

In contrast to jail and prison inmates in other countries (Dolan et al., 2005; Strang et al. 2006), incarcerated individuals in the United States are less likely to have access to heroin on a regular basis. As a result, despite their histories of heroin dependence prior to incarceration, while in pre-release facilities (Dole et al. 1969; Kinlock et al. 2002) or upon release to the community (Smith-Rohrberg et al. 2004), most such individuals are not tolerant to opioids. Therefore, it is necessary to begin opioid maintenance treatment at a low dose and to increase the dose slowly and gradually to minimize oversedation and other side effects. The dosing schedule used in the present study was generally well tolerated. Whether the weekly 5 mg dose increase, particularly once tolerance is reached at moderate doses, was too slow is not known. Clinically, as with methadone dosing in tolerant individuals, dosing should be individualized and careful, and regular assessment of potential side effects with appropriate dose adjustments is necessary.

Several studies have indicated that drug dependent prisoners are at high risk of overdose death within the first two weeks of release (Binswanger et al. 2007; Bird and Hutchinson, 2003; Stewart et al. 2004). The only overdose death by one month post-release occurred in a participant in the counseling only condition. One advantage of initiating treatment in prison and continuing that treatment in the community with opioid agonists might be reduction in the risk of overdose.

Because there are several limitations to this study, caution must be exercised in drawing conclusions. First, the sample only involved male prisoners from Baltimore. Although the present results regarding the effectiveness of methadone maintenance treatment initiated in a correctional facility are similar to those of Dole et al. (1969) reported earlier and of Dolan et al. (2005) in Australia (although the latter study had a considerably longer follow-up period-four years), statements about how the present results apply to female prisoners or to prison inmates from other geographic locations must be made with some caution due to variations in treatment needs and treatment responsiveness among drug-involved offenders by gender, ethnicity, and geographic location (Inciardi, 2001; Pelissier and Jones, 2005). Understandably, the availability of urine drug testing results on all 200 participants would have allowed a more precise comparison of the effects of treatment condition on heroin use and cocaine use. Furthermore, precise examination of self-report data was problematic because of the relatively large number of cases involving zero days, which was, in part, a function of underreporting. Also, it should be noted that the present study involved an intent-to-treat analysis, in that all individuals randomly assigned to each condition were considered regardless of whether they received treatment. Although it cannot be precisely determined what the results may have been had similar proportions of participants in each condition received the interventions to which they had been randomly assigned, given the magnitude of the differences in outcome, particularly between the Counseling + Methadone and Counseling Only conditions, most likely the results would have not have differed substantially from those presently reported. Finally, this was not a blinded study. Given that 18 individuals in the Counseling Only condition did not actually receive their treatment because they wanted methadone is a limitation because it may have reduced the efficacy of what could be achieved by counseling alone, if the participants had been unaware or believed that they were receiving the medication.

In conclusion, despite study limitations and the need to examine longer-term follow-up results, these preliminary results of the first controlled clinical trial of in-prison methadone maintenance treatment in the United States build on those obtained in our initial, smaller-scale study. Experiences in both studies, in the study by Dole and the methadone program in the New York City jail indicate that is quite feasible and effective to provide opioid agonist therapy to inmates with heroin addiction histories. Results suggest that the current intervention may be able to meet an urgent need in ensuring a continuum of drug abuse treatment spanning the institution and the community, an objective emphasized by the Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP, 2001b) and the American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence (AATOD, 2001). We consider these results promising, and future research on this sample will examine differences by treatment condition with regard to post-release treatment retention, heroin use, cocaine use, and criminal activity will be examined by treatment condition at 3-, 6-, and 12-months post-release. These latter analyses will provide important, longer-term outcome information regarding the relative effectiveness of the three treatment conditions as well as on the characteristics of individuals with favorable and unfavorable outcomes, both within and across condition.

Acknowledgments

First, we wish to thank Redonna K. Chandler, Ph.D., Chief, Services Research Branch, Division of Epidemiology, Services, and Prevention Research at NIDA and Program Official for the above referenced grant for her encouragement and support throughout the study. The authors would also like to thank the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services for providing space to conduct the intervention and for their support for the project, specifically Gregory Warren, Director of Substance Abuse Treatment Services; and the staff of the Metropolitan Transition Center, particularly Gary Hornbaker, Warden; Kendall Gifford, Case Management Manager, and Andrew Stritch, Audit Coordinator; the staff of Man Alive Research, specifically Karen Reese, Director, Gary Sweeney, Program Manager and Robin Ingram, Project Nurse for the provision of methadone maintenance treatment and counseling. In addition, we would like to thank the project staff at the Social Research Center; Kathryn Couvillion, Bernard Fowkles, Donnette Randolph, and Melissa Harris for their efforts related to this study.

Role of Funding Source. Funding for this study was provided by Grant R01 DA 16237 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and awarded to the first author; the NIDA had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Contributors. Drs. Kinlock and Gordon had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Drs. Kinlock, Schwartz, & Gordon were responsible for study concept, design, acquisition of data, drafting of the manuscript, and study supervision. Drs. O’Grady, Gordon, & Kinlock undertook analysis and interpretation of data. Drs. O’Grady, Wilson, & Fitzgerald were involved in critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors contributed and have approved the final manuscript.

Conflict of Interest. Dr. Schwartz is affiliated with the Open Society Institute-Baltimore, which funded the study of LAAM cited in the manuscript. No other authors reported disclosures.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Timothy W. Kinlock, Social Research Center, Friends Research Institute, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA, Phone: 410-837-3977 ext.224; Fax: 410-752-4218, email: tkinlock@frisrc.org and Division of Criminology, Criminal Justice, and Social Policy University of Baltimore, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA

Michael S. Gordon, Social Research Center, Friends Research Institute, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA

Robert P. Schwartz, Social Research Center, Friends Research Institute, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA and Open Society Institute-Baltimore, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA

Kevin O’Grady, Department of Psychology, University of Maryland, College Park, MD 20742 USA.

Terrence T. Fitzgerald, Man Alive, Inc., Baltimore, MD 21218 USA

Monique Wilson, Social Research Center, Friends Research Institute, Baltimore, MD 21201 USA.

References

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. New York: Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- American Association for the Treatment of Opioid Dependence. AATOD’s Five-Year Plan for Methadone Treatment in the United States. 2001 Retrieved August 16, 2004 from http://www.aatod.org/factsheet4_print.htm.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anglin MD. The efficacy of civil commitment in treating narcotic addiction. National Institute on Drug Abuse Research Monograph. 1988;86:8–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball JC, Ross A. The Effectiveness of Methadone Maintenance Treatment: Patients, programs, services, and outcomes. New York, NY: Springer; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Binswanger IA, Stern MF, Deyo RA, Heagerty PJ, Cheadle A, Elmore JG, Koepsell TD. Release from prison—a high risk of death for former inmates. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157–165. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa064115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird SM, Hutchinson SJ. Male drugs-related deaths in the fortnight after release from prison, Scotland, 1996–99. Addiction. 2003;98:185–190. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken JM. Correctional Population of the United States, 1997. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (NCJ Publication No. 177613); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Chaiken JM, Chaiken MR. Drugs and predatory crime. In: Tonry M, Wilson JQ, editors. Crime and Justice, Volume 13: Drug and Crime. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1990. pp. 203–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chitwood D, Comerford M, Weatherby N. The initiation and use of heroin in the age of crack. In: Inciardi JA, Harrison LD, editors. Heroin in the Age of Crack-cocaine. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 51–76. [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA. Can hepatitis C transmission be reduced in Australian prisons? Med J Aust. 2001;174:378–379. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143335.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dolan KA, Shearer J, White B, Zhou J, Kaldor J, Wodak AD. Four-year follow-up of imprisoned male heroin users and methadone treatment: mortality, re-incarceration, and hepatitis C infection. Addiction. 2005;100:820–828. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01050.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole VP, Nyswander M. A medical treatment for diacetylmorphine (heroin) addiction: a clinical trial with methadone hydrochloride. JAMA. 1965;193:80–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.1965.03090080008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dole V, Robinson J, Orraga J, Towns E, Searcy P, Caine E. Methadone treatment of randomly selected criminal addicts. N Eng J Med. 1969;280:1372–1375. doi: 10.1056/NEJM196906192802502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edlin BR. Prevention and treatment of hepatitis C in injection drug users. Hepatology. 2002;36:S210–219. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.36809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) Annual Report. Brussels: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Field G. [Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series 30, DHHS Publication No. (SMA) 98–3245] Rockville, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Treatment; 1998. Continuity of Offender Treatment for Substance Abuse Disorders from Institution to Community. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller C, Vlahov D, Safaeian M, Ompad D, Strathdee SA. Correlates of HIV infection among newly initiated adolescent and young adult injection drug users. Paper presented at the Society for Epidemiological Research 32nd Annual Meeting; Baltimore, MD. 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gray TA, Wish ED. Substance Abuse and Need for Treatment among Arrestees (SANTA) in Maryland. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Hagan H, Snyder N, Hough E, Yu T, McKiernan S, Boase J, Duchin J. Case-reporting of acute hepatitis B and C among injection drug users. J Urban Health. 2002;79:579–585. doi: 10.1093/jurban/79.4.579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanlon TE, Nurco DN, Bateman RW, O’Grady KE. The response of drug abuser parolees to a combination of treatment and intensive supervision. The Prison Journal. 1998;78:31–44. [Google Scholar]

- Hosmer D, Lemeshow S. Applied Logistic Regression. New York: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Hser YI, Hoffman V, Grella CE, Anglin MD. A 33-year follow-up of narcotics addicts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2001;58:503–508. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.58.5.503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA. The War on Drugs III. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Inciardi JA, McBride D, Surratt H. The heroin street addict: profiling a national population. In: Inciardi JA, Harrison LD, editors. Heroin in the Age of Crack-cocaine. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 31–50. [Google Scholar]

- Jaffe JH, Senay EC. Methadone and L-methadyl acetate: Use in management of narcotic addicts. JAMA. 1971;216:1303–1305. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RE, Chutuape MA, Strain EC, Walsh SL, Stitzer ML, Bigelow GE. A comparison of levomethadyl acetate, buprenorphine, and methadone for opioid dependence. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:1290–1297. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200011023431802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph H, Stancliff S, Langrod J. Methadone maintenance treatment (MMT): a review of historical and clinical issues. Mt Sinai J Med. 2000;67:347–364. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jurgens R. Is the world finally waking up to HIV/AIDS in prisons?. A report from the XV International AIDS Conference. Infectious Disease in Corrections Report, 7.2004. [Google Scholar]

- Karberg JC, James DJ. Substance Dependence, Abuse, and Treatment of Jail Inmates, 2002. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics (NCJ Publication No. 209588); 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Battjes RJ, Schwartz RP. A novel opioid maintenance program for prisoners: preliminary findings. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2002;22:141–147. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(02)00226-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Battjes RJ, Schwartz RP. A novel opioid maintenance program for prisoners: report of post-release outcomes. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2005a;31:433–454. doi: 10.1081/ada-200056804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Gordon MS. Substance abuse treatment: new research. In: Bennett LA, editor. New Topics in Substance Abuse Treatment. Nova Science Publishers; New York, NY: 2006. pp. 71–111. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, O’Grady KE, Hanlon TE. Prediction of the criminal activity of incarcerated drug-abusing offenders. J Drug Issues. 2003;33:897–920. [Google Scholar]

- Kinlock TW, Schwartz RP, Gordon MS. The significance of interagency collaboration in developing opioid agonist programs for inmates. Corrections Compendium. 2005b;30:6–9. 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Leukefeld CG, Tims FM, Farabee D. Treatment of Drug Offenders: Policies and Issues. New York, NY: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Maddux JF, Desmond DP. Careers of Opioid Users. New York, NY: Praeger; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Magura S, Rosenblum A, Lewis C, Joseph H. The effectiveness of in-jail methadone maintenance. J Drug Issues. 1993;23:75–99. [Google Scholar]

- Mark TL, Woody GE, Juday T, Kleber HD. The economic costs of heroin addiction in the United States. Drug Alcoh Depend. 2001;61:195–206. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(00)00162-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan AT, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the Addiction Severity Index: historical critique and normative data. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McSweeney T, Turnbull PJ, Hough M. Review of Criminal Justice Interventions for Drug Use in Other Countries. London: Criminal Policy Research Unit; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN. A long-term program of research on drug use and crime. Subst Use Misuse. 1998;33:1817–1837. doi: 10.3109/10826089809059323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nurco DN, Hanlon TE, Kinlock TW. Recent research on the relationship between illicit drug use and crime. Behav Sci Law. 1991;9:221–242. [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP) The National Drug Control Strategy Annual Report. Washington, DC: Executive Office of the President, Office of National Drug Control Policy; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Office of National Drug Control Policy. The National Drug Control Strategy Annual Report. Washington, D.C: Author; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pelissier B, Jones N. A review of gender differences among substance abusers. Crime Delinquency. 2005;51:345–372. [Google Scholar]

- Platt JJ, Widman M, Lidz V, Marlow D. Methadone maintenance treatment: its development and effectiveness after 30 years. In: Inciardi JA, Harrison LD, editors. Heroin in the Age of Crack-Cocaine. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 1998. pp. 160–187. [Google Scholar]

- Rezza G, Scalia Tomba G, Martucci P, Massella M, Noto R, DeRisio A, Brunetti B, Ardita S, Starnini G. Prevalence of the use of old and new drugs among entrants in Italian prisons. Ann 1st Super Sanita. 2005;41:239–245. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz RP, Highfield DA, Jaffe JH, Brady JV, Butler CA, Rouse CO, Callaman JM, O’Grady KE, Battjes RJ. A randomized controlled trial of interim methadone maintenance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:102–109. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.1.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith-Rohrberg D, Bruce RD, Altice FL. Research note-review of corrections-based therapy for opiate-dependent patients: implications for buprenorphine dependence among correctional populations. J Drug Issues. 2004;34:451–480. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart LM, Henderson CJ, Hobbs MS, Ridout SC, Knuiman MW. Risk of death in prisoners after release from jail. Austr N Z J Public Health. 2004;28:32–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2004.tb00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strang J, Gossop M, Heuston J, Green J, Whiteley C, Maden A. Persistence of drug use during imprisonment: relationship of drug type, recency of use and severity of dependence to use of heroin, cocaine, and amphetamine in prison. Addiction. 2006;101:1125–1132. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01475.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) Year-end 1999 Emergency Department Data from the Drug Abuse Warning Network. Rockville, MD: SAMHSA; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Tomasino V, Swanson AJ, Nolan J, Shuman HI. The Key Extended Entry Program (KEEP): A methadone treatment program for opiate-dependent inmates. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:14–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weatherburn D, Lind B. Heroin harm minimization: Do we really have to choose between law enforcement and treatment? New South Wales Crime and Justice Bulletin. 1999;46:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Wish ED, Yacoubian GS. Findings from the Baltimore City Substance Abuse Need for Treatment (SANTA) Project, 2001. College Park, MD: Center for Substance Abuse Research; 2001. [Google Scholar]