Abstract

Mitochondrial generated ROS increases with age and is a major factor that damages proteins by oxidative modification. Accumulation of oxidatively damaged proteins has been implicated as a causal factor in the age-associated decline in tissue function. Mitochondrial electron transport chain (ETC) complexes I and III are the principle sites of ROS production, and oxidative modifications to their complex subunits inhibit their in vitro activity. We hypothesize that mitochondrial complex subunits may be primary targets for modification by ROS which may impair normal complex activity. This study of heart mitochondria from young, middle-aged and old mice reveals that there is an age-related decline in complex I and V activities that correlate with increased oxidative modification to their subunits. The data also show a specificity for modifications of the ETC complex subunits, i.e., several proteins have more than one type of adduct. We postulate that the electron leakage from ETC complexes causes specific damage to their subunits and increased ROS generation as oxidative damage accumulates, leading to further mitochondrial dysfunction, a cyclical process that underlies the progressive decline in physiologic function of aged mouse heart.

Keywords: Aging, Carbonylation, 4, Hydroxynonenal, Mitochondrial Dysfunction, Nitration, Oxidative Stress

Introduction

Increasing ROS production, an aging cardiomyocyte phenotype, is a major consequence of mitochondrial dysfunction [1,2] that contributes to age-associated cardiomyocyte injury in normal aging as well as during myocardial ischemia. [3,4] However, although the site of ROS production in myocardial dysfunction has been localized to specific electron transport chain (ETC) complexes, the consequences of this oxidative stress i.e., the oxidative damage to proteins of the ETC complexes are not understood. In this study we identify oxidatively modified proteins in aging cardiomyocytes as an important step in understanding their potential role in myocardyocyte aging and injury.

Complex I (CI) and complex III (CIII) are the major sites for ROS production in aging and ischemia-reperfusion injury of the heart [5–7]. The NADH dehydrogenase site of CI, which is also the site of electron leakage, is located in the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane [8]. Thus, oxidant production from CI is directed into the mitochondrial matrix where oxidative damage to mitochondrial proteins may occur. Our studies have shown that oxidative modification of proteins of CI–CV accumulate in aging mouse kidney, suggesting that such modifications may play a role in age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction [9].

Complex III (CIII), also a key site of ROS generation, [6,10–12] has been shown to release superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane [10,13–15] The sites of release of ROS suggest that the protein components most proximal to these sites may also be at risk for oxidative damage. Thus, the identification of oxidatively modified proteins of the ETC complexes may contribute to further understanding of the molecular mechanisms of mitochondrial dysfunction in aging and age-associated cardiomyocytes injury. In this study we have focused upon the identification of oxidatively modified proteins of the ETC complexes of the aged mouse heart.

Increasing oxidative stress resulting from progressive mitochondrial dysfunction, as proposed by the Free Radical Theory of Aging, is a basic mechanism of mammalian aging [16,17]. Mitochondrial ROS production plays a central role in the age-associated decline in tissue function [18–20]. Mitochondrial generated ROS, produced by in vivo electron leakage from ETC CI and CIII play a key role in the modification of mitochondrial proteins [18,21–25]. These modifications have served as molecular markers of oxidative stress [26,27]. In these experiments we identify the oxidatively modified ETC CI–CV proteins in aged mouse heart, whether these proteins accumulate with age and affect ETC complex function.

The relative abundance of modified proteins is indicative of the level of accumulation of oxidatively damaged macromolecules in aged tissues [9,27]. Protein modifications caused by ROS include the formation of lipid peroxidation adducts (4-hydroxynonenal or HNE and malondialdehyde or MDA), carbonylation of lysine, arginine, proline, and threonine, and nitration of tyrosine [28–31]. Oxidatively damaged proteins have been detected and identified by mass spectrometry [9,26,32]. We propose to determine whether such oxidative modifications cause mitochondrial dysfunction associated with aging and age-associated diseases [9,30,31–33]. The accumulation of these oxidatively modified proteins occurs in various tissues [9] and their accumulation in cardiovascular tissue may, therefore, be an important molecular marker of age-associated decline in cardiovascular function. We propose that oxidative modification may play an important role in the molecular mechanisms of aging and development of age-associated diseases, including cardiovascular disease.

In this study we analyzed the activities of ETC CI–CV to identify potential age-associated functional changes and whether the modifications of specific proteins correlate with changes in enzyme activities. We chose hearts to test the hypothesis that oxidative modification of proteins may lead to a decline of cardiovascular function and whether specific proteins of CI–CV proximal to the sites of ROS production are susceptible to oxidative damage. Our studies provide further support for the Mitochondrial Theory of Aging as indicated by the loss of function of oxidatively modified ETC proteins leading to a decline in tissue function.

Materials and methods

Animals

Young (3–5 months), middle-aged (12–14 months) and old (20–22 months) male C57BL/6 mice were purchased from the National Institute on Aging (Bethesda, MD). Mice were maintained with a 12h light/dark cycle and fed ad libitum on a standard chow diet before sacrifice.

Mitochondrial isolation

Mice were sacrificed by decapitation and their hearts were harvested immediately, rinsed in ice-cold PBS to remove blood, and prepared for subcellular fractionations. Mitochondria were prepared from the pooled hearts of 9 young, 10 middle-aged and 8 old C57BL/6 male mice. Mitochondrial isolation was carried out at 4°C as described with minor modifications [9,34,35].

Enzyme activities

Enzyme activities were performed at room temperature using Beckman Coulter DU 530 Spectrophotometer (Beckman Coulter, CA). Citrate synthase activity was measured as described [19,36]. Briefly, in each 1 mL assay reaction mixture containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 2 mM EDTA, 0.1% Triton X-100 and 1 mg/mL BSA) 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria (as described above) were added followed by addition of 0.1 mM Acetyl-CoA and 2 mM DTNB. The reaction was initiated with the addition of 40 μM oxaloacetate and the enzyme activity was recorded at 412 nm (ε = 13.6 mM−1 cm−1). Rotenone-sensitive Complex I (CI) activity, Malonate-sensitive Complex II (CII) activity, Antimycin A-sensitive Complex III (CIII) activity, KCN-sensitive Complex IV (CIV) activity, and Oligomycin-sensitive Complex V (CV) activities were assayed as described [9,26, 33]. Briefly, CI activity was measured at 340 nm (ε = 6.81 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mg/mL BSA), 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 2 mM KCN, 3.7 μM Antimycin A and 100 μM Q1. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 140 μM NADH and after 3 minutes 20 μM Rotenone was added to inhibit the enzyme activity. The final rate was measured by subtracting Rotenone-insensitive rate from initial rate. CII activity was measured at 600 nm (ε = 19.1 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture initially incubated at 30°C for 20 minutes containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mg/mL BSA), 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 20 mM succinate and 0.2 mM ATP. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 20 μM Rotenone, 2 mM KCN, 3.7 μM Antimycin A, 50 μM DCPIP and 100 μM Q1. After 3 minutes 10 mM Malonate was added to inhibit the enzyme activity. The final rate was measured by subtracting Malonate-insensitive rate from initial rate. CIII activity was measured at 550 nm (ε = 19 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mg/mL BSA), 1 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 20 μM Rotenone, 2 mM KCN, 0.2 mM ATP and 40 μM cytochrome c. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 μM decyl benzoquinol with or without 7.4 μM Antimycin A. The final rate was measured by subtracting Antimycin A-insensitive rate from rate without the addition of the inhibitor. CIV activity was measured at 550 nm (ε = 19 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture containing reaction buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 20 mM KCl and 1 mg/mL BSA), 0.5–1 μg of sonicated mitochondria, and 1 mM dodecyl-β-D-maltoside. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 11 μM ferrocytochrome c with or without 2 mM KCN. The final rate was measured by subtracting KCN-insensitive rate from rate without the addition of the inhibitor. CV activity was measured at 340 nm (ε = 6.2 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture containing reaction buffer (50 mM HEPES-KOH, pH 8.0, 5 mM MgCl2 and 250 mM sucrose), 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 25 units of pyruvate kinase, 25 units of lactate dehydrogenase, 20 μM Rotenone, 2 mM KCN, 5 mM phosphoenolpyruvate, and 175 μM NADH. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 2.5 mM ATP and after 3 minutes 15 μM Oligomycin was added to inhibit the enzyme activity. The final rate was measured by subtracting Oligomycin-insensitive rate from initial rate.

CI–III and CII–III coupled assays were performed as described [9,37]. Briefly, CI–CIII activity was measured at 550 nm (ε = 19 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture initially incubated at 30°C for 10 minutes containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2 and 1 mg/mL BSA), 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 350 μM NADH and 2 mM KCN. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 80 μM cytochrome c and after 2 minutes, both 20 μM Rotenone and 7.4 μM Antimycin A were added to inhibit the coupled activity. The final rate was measured by subtracting inhibitor-insensitive rate from initial rate. CII–CIII activity was measured at 550 nm (ε = 19 mM−1 cm−1) in 1 mL reaction mixture initially incubated at 30°C for 20 minutes containing reaction buffer (50 mM Potassium Phosphate, pH 7.4, 5 mM MgCl2, 0.5 mM EDTA and 1 mg/mL BSA), 7–8 μg of sonicated mitochondria, 20 mM succinate, 20 μM Rotenone, 2 mM KCN and 0.2 mM ATP. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 40 μM cytochrome c and after 2 minutes 10 mM Malonate was added to inhibit the coupled activity. The final rate was measured by subtracting Malonate-insensitive rate from initial rate.

All activity results are averages of 4 assays from the pooled sample for each age group. Citrate synthase assay results were used to calculate ratios of young to middle-age and young to old mitochondrial protein levels and these ratios were multiplied to normalize each enzyme activity for specific age group. Statistical significance was calculated using the Student’s T-test with p<0.05 and p<0.001 considered significant and highly significant, respectively.

Polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

BN-PAGE and SDS-PAGE were carried out by established methods with minor modifications [9,26,38]. Briefly, a 5 to 12% acrylamide gradient was used for the first dimension BN-PAGE, imidazole instead of Bis-Tris was used as a buffer, and Criterion 10–20% 2D-well gels (Bio-Rad, CA) were used for the second dimension SDS-PAGE.

Immunoblotting

Immunoblot analysis was performed as described [9,34]. Briefly, all immunoblots were generated after overnight transfer and were blocked with 5% non-fat blocking grade milk (Bio-Rad, CA) in TBS-T (Tris base saline, pH 7.4, and 0.05% Tween-20) and incubated with appropriate antibody dilutions in blocking solution for 1 hour or overnight. The blots were washed three times for 5 minutes each with TBS-T and probed with appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (Alpha Diagnostic, TX). Immunoreactive bands were detected by chemiluminescence using the Immobilon Western HRP substrate (Millipore, MA), and images recorded using Kodak X-Omat AR films. Films were analyzed using Alpha Innotech FluorChem IS-8900 imager (Alpha Innotech Corporation, CA) and density values were calculated according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Intact mitochondrial ETC complex bands were visualized by antibodies against CI (NDUFA9 subunit), CII (SDHA subunit), CIII (UQCRFS1 subunit), CIV (COX1), and CV (ATP5A1 subunit) (Molecular Probes, OR). CIV-specific antibody is against mitochondrially encoded subunit COX1. All other complex-specific antibodies are against nuclear encoded subunits. Several types of oxidative modifications were detected using a mouse monoclonal anti-nitrotyrosine antibody (Upstate Biotechnology, NY), anti-MDA goat polyclonal antibody (Academy Bio-Medical, TX) and anti-HNE Fluorophore rabbit polyclonal antibody (EMD Biosciences, CA). Carbonylated proteins were derivatized with 2,4-dinotrophenylhydrazine (DNPH) to generate a stable 2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone (DNP) adduct at the carbonyl group [39,40]. Anti-DNP rabbit polyclonal antibody (Molecular Probes, OR) was then used to detect DNP-derivatized proteins. All oxidative modification detecting immunoblots were stripped using Restore ™ western blot stripping buffer (Pierce Biotechnology, IL) per manufacturer’s recommendations and re-probed with complex-specific antibodies as mentioned above to normalize protein loading. The density values were background subtracted, normalized to protein loading using ratios from anti-complex antibodies, and converted to percentage using density of young protein bands as 100%. Data represented in the figures are from the same samples for each age group where tissues from 9 animals were pooled in the young group, 10 animals in the middle-aged group and 8 animals in the old age group. Pooling 8–10 tissues maximizes the recovery of mitochondria and minimizes outliers and thus, the observed differences in oxidative modification levels are taken as true biological variations.

MALDI-TOF-TOF

Individual ROS-modified protein bands were excised from second dimension SDS-PAGE run simultaneously with the gels that were immunoblotted and analyzed by the Proteomics Core Facility at UTMB. The proteins were eluted from the gel and digested with trypsin (Promega, WI); the tryptic peptides were then analyzed by MALDI-TOF-TOF [26]. Mass spectral peak data were submitted to the ProFound (Rockefeller University) online search engine for protein identification using the NCBI database.

Results

Inhibitor-sensitive enzyme activities

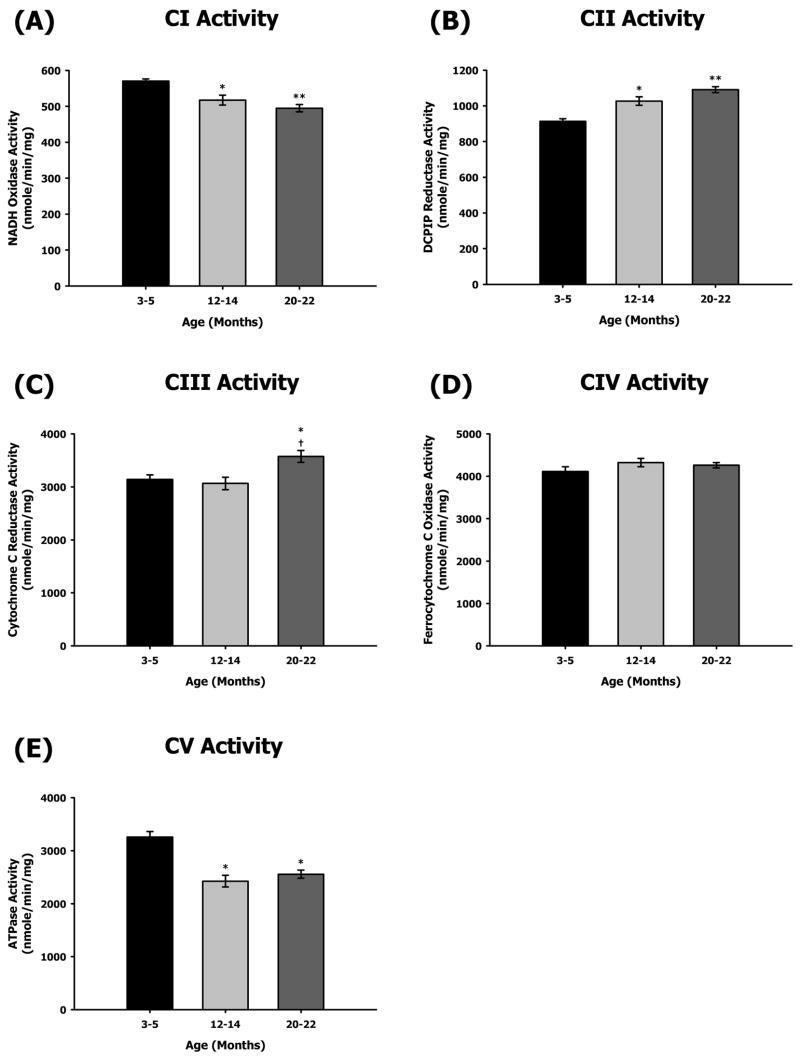

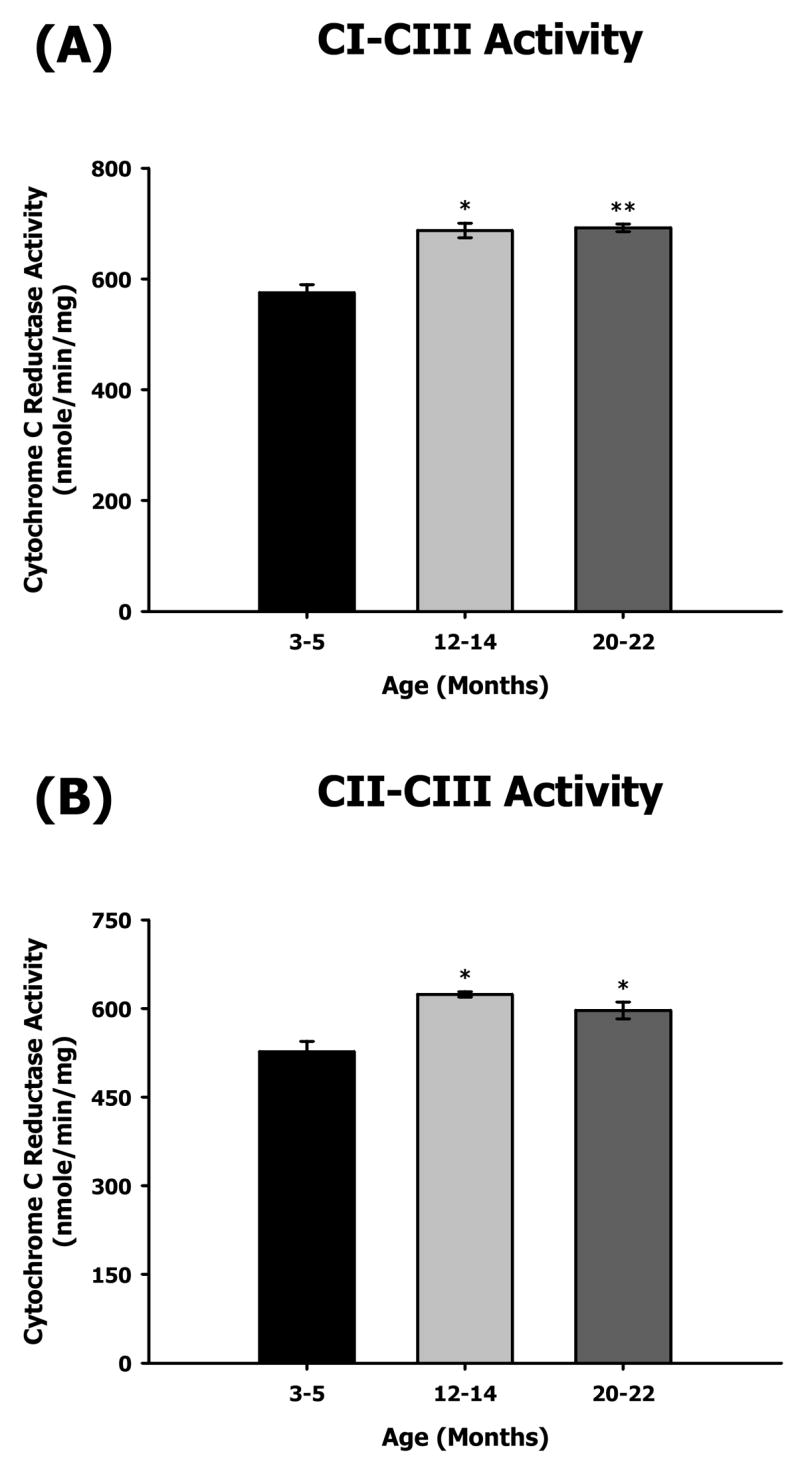

To evaluate the physiological effects of aging on heart mitochondrial ETC complexes, we measured the enzymatic activities of all five complexes as well as the coupled activities of CI–III and CII–III for all three ages (Figures 1 and 2). As evident from the data, only CI and CV from the aged heart showed decrease in enzyme activities. In contrast, CII as well as CI–CIII and CII–CIII coupled activities showed an age-related increase in enzyme function (Figures 1 and 2). Rotenone-sensitive CI activity decreased by ~9% at middle-age and by ~13% at old age compared to young (Figure 1A). In contrast, there was a ~20% increase in CI–III coupled activity in both middle and old age compared to young age (Figure 2A). Malonate-sensitive CII activity also showed an increase with age, i.e., CII activity increased by ~12% and ~19% at middle and old age, respectively (Figure 1B). Similarly, the CII–CIII coupled activity increased with age, i.e., there was an ~18% increase at middle age and an ~13% increase by old age (Figure 2B). Antimycin A-sensitive CIII activity also increased by ~14% at old age (Figure 1C). KCN-sensitive CIV activity did not show any change with aging (Figure 1D). Oligomycin-sensitive CV activity showed the most dramatic decline with aging especially at middle age, i.e., ~25% decrease in middle age and no further decline in old age (Figure 1E).

Figure 1.

Measurement of ETC complex activities from 3–5, 12–14, and 20–22 month-old mouse heart mitochondria. Individual complex enzyme activities were measured spectrophotometrically as described in Materials and Methods. All activity results are averages of 4 assays from the pooled sample + SEM for each age group. Citrate synthase assay results were used to normalize mitochondrial proteins. Activities for young (3–5 months), middle-aged (12–14 months), and old (20–22 months) heart ETC CI–CV are plotted as following. (A) CI activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 2% (young), 5.4% (middle-age), and 4.1% (old), respectively. (B) CII activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 3.2% (young), 4.6% (middle-age), and 3% (old), respectively. (C) CIII activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 5.7% (young), 7.8% (middle-age), and 6.3% (old), respectively. (D) CIV activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 5.4% (young), 4.6% (middle-age), and 2.9% (old), respectively. (E) CV activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 6.5% (young), 9.1% (middle-age), and 6% (old), respectively. * - p<0.05 compared to young, ** - p<0.001 compared to young, and † - p<0.05 compared to middle-aged.

Figure 2.

Measurement of coupled mitochondrial ETC complex activities from 3–5, 12–14, and 20–22 month-old mouse heart mitochondria. CI–III and CII–III coupled enzyme activities were measured spectrophotometrically as described in Materials and Methods. All activity results are averages of 4 assays from the pooled sample ± SEM for each age group. Citrate synthase assay results were used to normalize mitochondrial proteins. Activities for young (3–5 months), middle-aged (12–14 months), and old (20–22 months) heart ETC CI–III and CII–III are plotted as following. (A) CI–CIII coupled activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 4.9% (young), 3.8% (middle-age), and 1.9% (old), respectively. (B) CII–CIII coupled activity with aging. Coefficients of variance were 6.8% (young), 1.5% (middle-age), and 4.8% (old), respectively. * - p<0.05 compared to young and ** - p<0.001 compared to young.

Overall, the mitochondrial ETC enzyme activities of mouse heart show a differential pattern such that CI and CV enzyme activities declined, CII and CIII as well as CI–CIII and CII–CIII coupled activities increase, and CIV activity does not change with age.

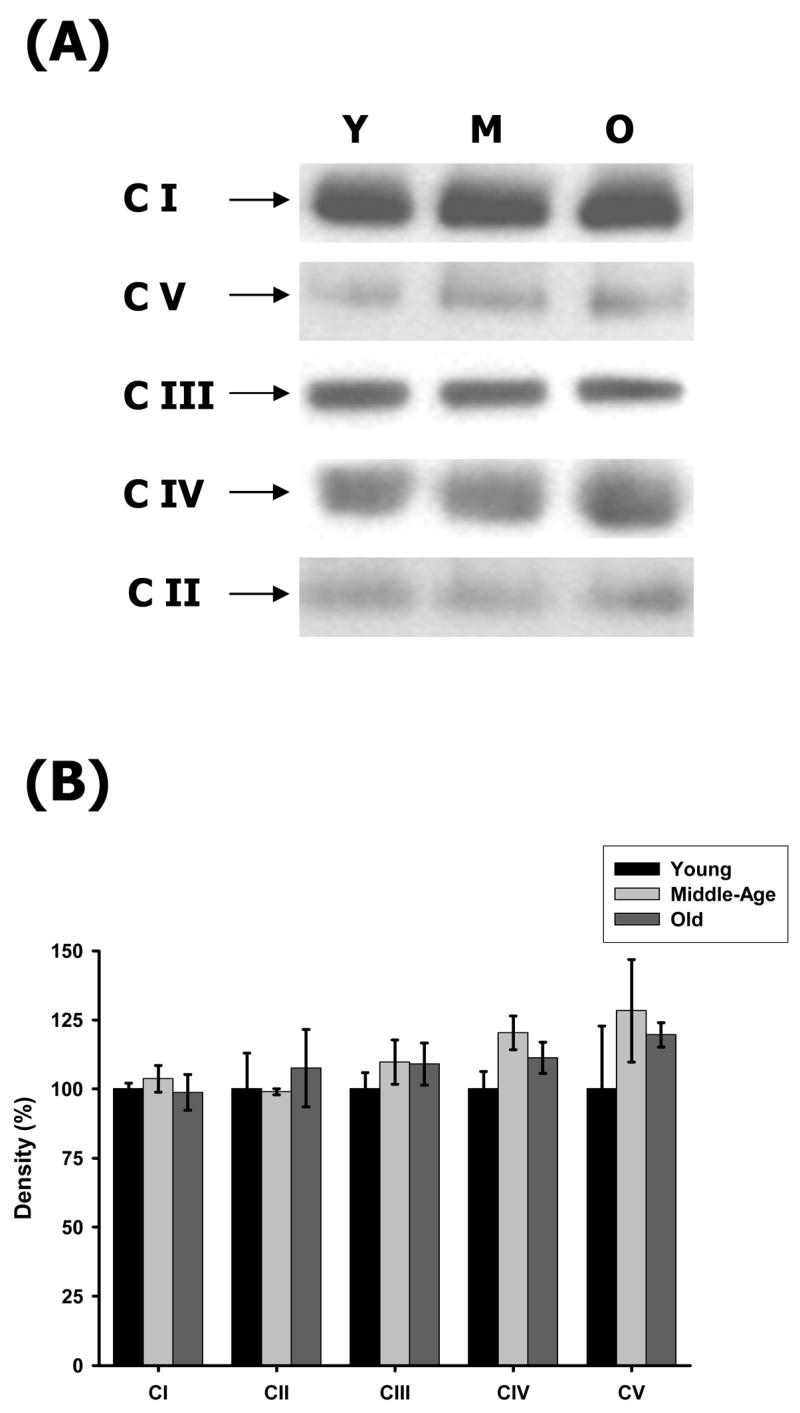

Abundance of ETC complexes in young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondria

To determine if the changes in enzyme function with aging are due to changes in enzyme levels, the CI–CV complexes were resolved by BN-PAGE and the levels of ETC complexes were measured by using immunoblotting with complex-specific antibodies. In previous studies we established the use of immunobloting of BN-PAGE resolved complexes with complex specific antibodies as a method to determine complex abundance [9]. This procedure has also been used in these studies to determine whether there are age-related quantitative differences in levels of individual complexes [9,40]. Our results show very little age-related changes in complex levels in heart mitochondria (Figure 3). Though the data support a 15–20% increase of CIV and CV levels in middle age (Figure 3B) the changes are not statistically significant and the enzyme activities of both individual complexes were not affected. However, since the ETC complexes are multi-protein complexes, our procedure does not detect any minor changes in components of these complexes.

Figure 3.

Protein abundance of ETC complexes in young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondria. Young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondria (160 μg) were solubilized and the ETC complexes were separated on a BN-PAGE as described in Materials and Methods. (A) Representative immunoblots of heart BN-PAGE using complex-specific antibodies. The complexes are shown according to their mass and positions in the BN-gels. Lane 1, 2 and 3 represent young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complexes, respectively. (B) Density values of each ETC complex band are plotted as a percentage of young complexes. All results are averages of 3 immunoblot analyses from the pooled sample + SEM for each age group. Coefficients of variance for CI were 2.2% (young), 4.6% (middle-age), and 6.5% (old), respectively. Coefficients of variance for CII were 13% (young), 1.1% (middle-age), and 13% (old), respectively. Coefficients of variance for CIII were 6% (young), 7.4% (middle-age), and 7% (old), respectively. Coefficients of variance for CIV were 6.3% (young), 5.1% (middle-age), and 5.1% (old), respectively. Coefficients of variance for CV were 22.7% (young), 14% (middle-age), and 3.6% (old), respectively. Y = young mitochondria, M = middle-age mitochondria and O = old mitochondria.

Oxidative modification of ETC complex subunits with aging

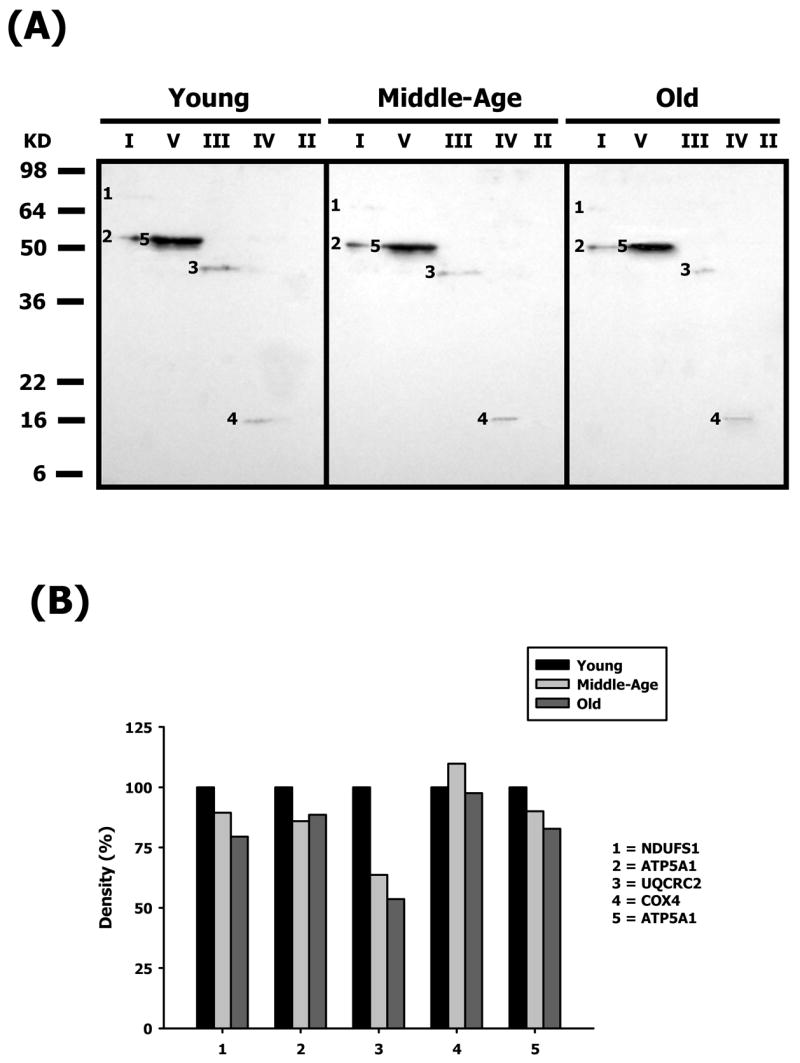

To identify the oxidatively modified ETC complex proteins from mouse hearts, immunoblotting of second dimension gels was performed to detect individual proteins with carbonylation (Figure 4A), as well as HNE (Figure 5A), nitrotyrosine (Figure 6A) and MDA (none detected) adducts. The corresponding change in percent density for protein modification is expressed relative to young protein density and is shown in Figures 4B, 5B, and 6B. Duplicate second dimension gels were run simultaneously for each immunoblot and used for identification of modified proteins by MALDI-TOF-TOF summarized in Table 1. All experiments were performed twice to check for accuracy of results and showed almost identical results. This along with results from Figure 3 confirmed that the results we obtained from immunoblots to detect oxidative modifications were valid and led us to make further conclusions as discussed below.

Figure 4.

Identification of carbonylated proteins of young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complex subunits. Heart mitochondrial ETC complexes were resolved into individual subunits and DNP-derivatized after transfer to PVDF membrane as described in Materials and Methods followed by immunoblotting. (A) Immunoblot of young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complex subunits using anti-DNP antibody. Modified proteins were numbered according to their complex localization followed by the highest to the lowest molecular weight of the proteins. Protein loading was normalized using complex-specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Normalized density values of each individual carbonylated protein are plotted as a percentage of the young heart protein density for all five ETC complex subunits. (B) Densitometry for modified proteins found in CI (1 & 2), CII (3–5) and CIII (6). (C) Densitometry for modified proteins found in CIV (7–10) and CV (11). Identification of each numbered band is summarized in Table 1.

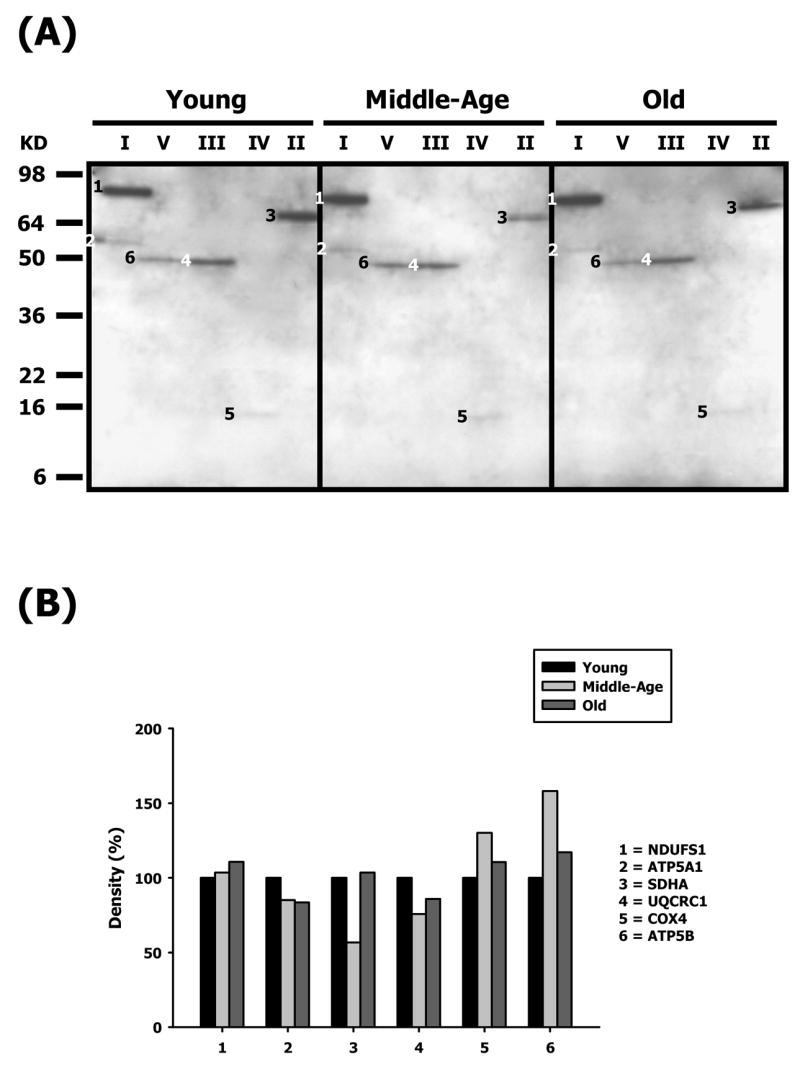

Figure 5.

Identification of HNE-modified proteins of young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complex subunits. Heart mitochondrial ETC complexes were resolved into individual subunits as described in Materials and Methods followed by immunoblotting. (A) Immunoblot of young, middle-aged and old pectoralis mitochondrial ETC complex subunits using anti-HNE antibody. Modified proteins were numbered according to their complex localization followed by the highest to the lowest molecular weight of the proteins. Protein loading was normalized using complex-specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. Normalized density values of each individual protein modified by HNE are plotted as a percentage of the young heart protein density for each specific complex subunit. (B) Densitometry for modified proteins found in CI (1 & 2), CIII (3), CIV (4) and CV (5). Identification of each numbered band is summarized in Table 1.

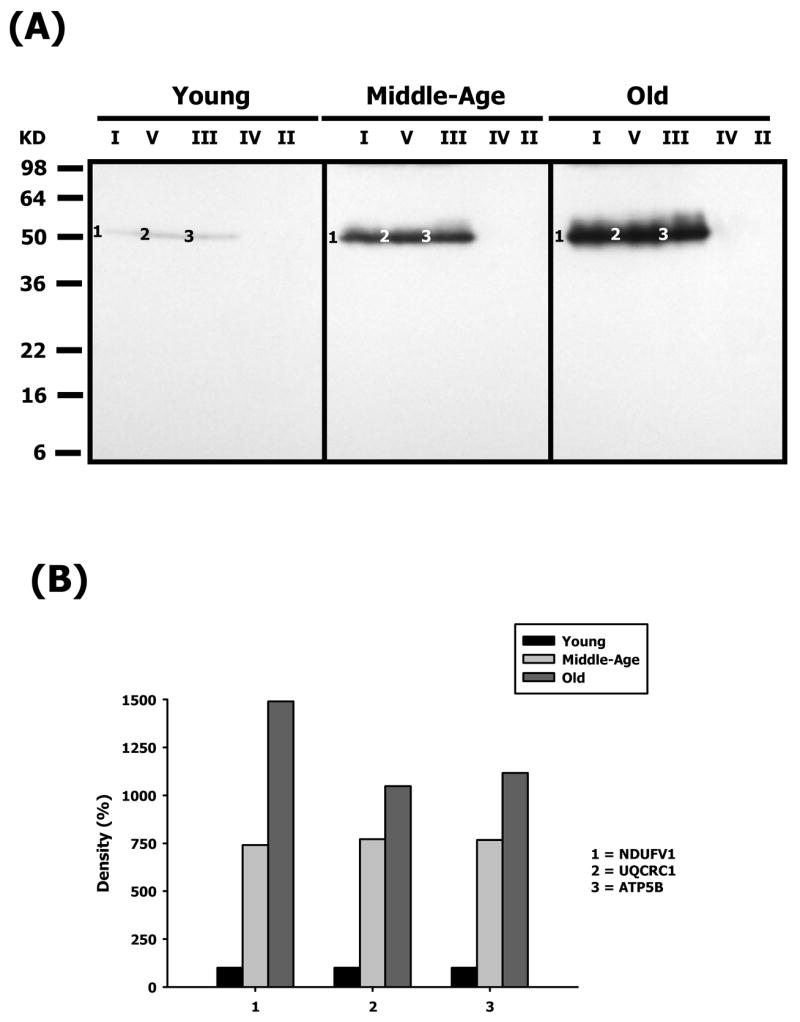

Figure 6.

Identification of nitrotyrosine-modified proteins of young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complex subunits. Heart mitochondrial ETC complexes were resolved into individual subunits as described in Materials and Methods followed by immunoblotting. (A) Immunoblot of young, middle-aged and old heart mitochondrial ETC complex subunits using anti-nitrotyrosine antibody. Modified proteins were numbered according to their complex localization followed by the highest to the lowest molecular weight of the proteins. Protein loading was normalized using complex-specific antibodies as described in Materials and Methods Normalized density values of each individual protein modified by nitrotyrosine are plotted as a percentage of the young heart protein density for each specific complex subunit. (B) Densitometry for modified proteins found in CI (1), CIII (2), CIV(3) and CV (4 & 5). Identification of both bands is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Carbonylated and HNE and Nitrotyrosine-Modified Protein Subunits of Mouse Heart Mitochondrial Electron Transport Chain Complexes.

| Band # | Gene Name | ProFound Protein ID (MW) | E-valuea | Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbonylated (Figure 4A) | ||||

| 1 | NDUFS1 | Fe-S Subunit 1 (79.7 kDa) | 1.1 × 10−26 | Complex I |

| 2 | ATP5A1 | α Chain (59.7 kDa) | 1.7 × 10−56 | Complex V |

| 3 | UQCRC2 | Core 1 (52.7 kDa) | 5.4 × 10−34 | Complex III |

| 4 | COX4 | Subunit 4 (19.5 kDa) | 5.4 × 10−17 | Complex IV |

| 5 | ATP5A1 | α Chain (59.7 kDa) | 4.3 × 10−50 | Complex V |

| HNE-Modified (Figure 5A) | ||||

| 1 | NDUFS1 | Fe-S Subunit 1 (79.7 kDa) | 1.1 × 10−26 | Complex I |

| 2 | ATP5A1 | α Chain (59.7 kDa) | 1.7 × 10−56 | Complex V |

| 3 | SDHA | Succinate Dehydrogenase 1 (72.3 kDa) | 2.2 × 10−15 | Complex II |

| 4 | UQCRC1 | Core 1 (52.7 kDa) | 8.0 × 10−35 | Complex III |

| 5 | COX4 | Subunit 4 (19.5 kDa) | 5.4 × 10−17 | Complex IV |

| 6 | ATP5B | β Chain (56.3 kDa) | 1.4 × 10−48 | Complex V |

| Nitrotyrosine-Modified (Figure 6A) | ||||

| 1 | NDUFV1 | Flavoprotein 1 (50.1 kDa) | 5.0 × 10−64 | Complex I |

| 2 | UQCRC1 | Core 1 (52.7 kDa) | 8.0 × 10−35 | Complex III |

| 3 | ATP5B | β Chain (56.3 kDa) | 1.4 × 10−48 | Complex V |

Protein E-value or expectation value assigned by the Mascot database is the number of matches with equal or better scores that are expected to occur by chance alone. In each MALDI-TOF-TOF run the significance threshold was set at a more stringent value of 1.0 × 10−3 compared to the default value of 0.05. Thus, any number below the threshold was considered significant.

Oxidatively modified proteins of Complex I

The carbonylated and HNE-modified CI protein, shown in Figures 4A and 5A was identified as the Fe-S subunit 1 (NDUFS1, band 1). With respect to age, this protein shows a mild decrease in carbonylation (#1 – Figure 4B) and an increase in HNE (#1 – Figure 5B). Oxidative modification of NDUFS1 shows very little change with age, and since this subunit is part of the iron-sulfur protein (IP) region, it bears significance that it is specifically modified at all ages. In contrast, NDUFV1, part of the flavoprotein (FP) region, was heavily modified by nitration in an age-dependent manner (Figure 6A). The nitration of NDUFV1 increased to more than 7-fold by middle age and ~14.5-fold at old age. Again, since this protein is a component of FP region, the dramatic modification of this subunit shows that it may be specifically targeted by ROS-mediated damage. It is also of particular interest to note that the α-chain of CV also co-migrated with CI and was modified by carbonylation (band 2 – Figure 4A) and contained HNE (band 2 – Figure 5A) adducts. The CI-associated α-chain showed an age-associated decrease in carbonylation levels (#2 – Figure 4B) and in HNE levels (#2 – Figure 5B).

Oxidatively modified proteins of Complex II

Subunit 1 (SDHA, band 3 – Figure 5A) is the only protein of Complex II that was oxidatively modified by HNE adducts. Though the modification of SDHA was seen in all ages, there was a decrease in levels of HNE modification at middle age (~44%) and no change in old age (#3 – Figure 5B) compared to young mice. Since SDHA spans through the inner mitochondrial matrix and more than half of the protein is exposed to the matrix where it houses the FAD co-factor and the active site for substrate binding, its differential modification with lipid peroxidation suggests that it is specifically targeted by ROS-mediated damage.

Oxidatively modified proteins of Complex III

The oxidatively-modified CIII proteins are shown in Figures 4A, 5A and 6A and include Core 1 (UQCRC1, band 4 – Figure 5A and band 2 – Figure 6A) and Core 2 (UQCRC2, band 3 –Figure 4A). While Core 1 is modified by nitration and HNE, Core 2 is carbonylated. The modification of Core 2 shows an age-related decrease in carbonylation and by old age it decreases by ~ 46% compared to young mice (#3 – Figure 4B). Core 1, on the other hand, shows a differential profile of decreased HNE modification and very high increase in nitration with age. The HNE levels in Core 1 decrease by ~24% in middle age and ~14% at old age compared to young age (#4 – Figure 5B). In contrast, Core 1 is heavily nitrated in an age-dependent manner and the nitration increases by more than 7.5-fold in middle age and ~10-fold at old age (Figure 6). Both Core 1 and Core 2 proteins are anchored to the inner mitochondrial membrane with most of the protein exposed to the matrix side. Since CIII is one of the ROS-generating sites in mitochondria, the topographical arrangement of these CIII proteins and the proximity to electron transfer sites may explain the differential modifications for these proteins.

Oxidatively modified proteins of Complex IV

Subunit 4 (COX4) is the only CIV protein that is both carbonylated (band 4 – Figure 4A) and HNE-modified (band 5 – Figure 5A). COX4 showed a similar pattern of modification, i.e., a ~10% (carbonylation) and ~30% (HNE modification) increase in middle age and a decrease back to basal levels by old age (#4 – Figure 4B and #5 – Figure 5B, respectively). COX4 mainly plays a role in stability of this enzyme in the mitochondrial inner membrane and is not involved in the physiological activity of CIV [41].

Oxidatively modified proteins of Complex V

Both the α- and β-chains of CV are differentially oxidatively modified with aging. The α chain was carbonylated (ATP5A1, band 5 – Figure 4A) while the β-chain was both HNE modified (band 6 – Figure 5A) and nitrated (band 3 – Figure 6A). The α-chain shows an age-related decrease in carbonylation level by ~10% in middle age and ~18% by old age (#5 – Figure 4B). Interestingly, carbonylated α-chain was also found to co-migrate with CI and showed a similar profile of modification (band 2 – Figure 4A and #2 – Figure 4B). Although, the α-chain is HNE-modified, the oxidatively damaged protein is not detected in the intact complex but is, instead, associated with CI (band 2 – Figure 5A). The β-chain, on the other hand, shows an age-associated increase in HNE modification (band 6 – Figure 5A) that increases to ~56% in middle age and decreases to ~17% in old age, compared to young mice (#6 – Figure 5B). In addition, the β-chain, is heavily nitrated (band 3, Figure 6A), and shows a more than 7.5-fold increase in modification in middle age and increases further to more than 11-fold in old mice. Both α- and β-chains are involved in ATP biosynthesis that is coupled with proton translocation and are not directly proximal to electron transfer sites of ETC. Thus, the differential, dramatic and highly reproducible modification of these subunits with aging suggests that they are specific targets of ROS-mediated damage.

Discussion

Our studies identified oxidatively modified mouse heart mitochondrial ETC proteins whose levels of modification in some cases correlated with the decrease in complex activity as is predicted by the Free Radical Theory of Aging [9,16,17,27,33] whereas in others, modifications had no effect on functions, thus suggesting the interaction of other factors. The decrease in CI and CV enzyme functions is consistent with our hypothesis that mitochondrial dysfunction in the aging heart may be due to the accumulation of oxidatively modified proteins. On the other hand, the continuous decrease of CI enzyme activity and increase in coupled activity of CI–CIII activity with age is not consistent with the decline in CI function. Neither are the increases of CII enzyme activity and CII–CIII coupled activities consistent with the concept of age-associated progressive increase in mitochondrial dysfunction. We propose that this increase of CII activity may be due to a tighter coupling between CII and CIII in response to the loss of CI enzyme activity. Although the mechanism of this unique response is not understood, we propose that this may enable the cell to balance the decline in CI activity by shunting of electrons through CII and increasing the efficiency of electron transfer between CII and CIII. Thus, although this may be a less favorable pathway, the increased efficiency may lessen the adverse effect of loss of CI activity.

The fact that CII function increases with age was a surprising observation that led us to consider that the loss of enzyme function in CI may be alleviated by improvement of CII function with aging. Interestingly, the HNE modification of SDHA, a core component of CII, is not consistent with the increased CII–CIII coupled activity. The location of SDHA in the matrix hydrophilic environment may favor its modification by ROS-mediated intermediates due to its proximity to lipid peroxidation products. However, the age-associated increase of CII enzyme function and a corresponding decrease in oxidative modification may be the basis for improved CII function. Whether this affects the overall mitochondrial and tissue dysfunction remains to be demonstrated.

Numerous studies, in both rodents and humans, examined enzyme function of aged heart mitochondrial ETC complexes, and have consistently shown that in human heart there is no change in ETC function with aging [33.36,37,42–46]. However, studies of rodent heart tissue have not shown any consensus as to which functions is affected. For example, some studies show there is a decline in CI, CIV [47] and CV [33] function while others show no changes at all. We attribute these differences in part to the variation of markers used to normalize mitochondrial content. Furthermore, some studies did not examine inhibitor-sensitive activities as well as CI–CIII and CII– III coupled activities, which provide important physiological functional information. In our study, the use of the ratios of citrate synthase activity from young and middle age and young and old age as well as two methods of protein determination provided stringent standards of normalization of mitochondrial protein content. We also measured all inhibitor-sensitive enzyme activities as well as the CI–CIII and CII–CIII coupled activities at young, middle and old ages. Using these parameters, our studies show that there is an age-related decline in mouse heart CI and CV function.

The NDUFS1 iron-sulfur protein and the flavoprotein NDUFV1 in CI that were found to contain multiple types of modifications, are located in the mitochondrial matrix and are in proximity the proposed site of ROS generation [22,24,48]. It is not surprising, therefore, that these proteins were specific targets of ROS modification. The same ETC complex subunits are differentially modified in the three age groups, suggesting that these proteins are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage, and, since CI is the rate-limiting enzyme in oxidative phosphorylation, modification of its subunits may have a direct impact on the overall energy state of the cell.

The carbonylation and HNE modification of NDUFS1 showed very little change with aging, suggesting that this protein is not susceptible to increased ROS production with age or, the turnover of the modified protein also increases thereby giving the appearance of no change of the modified protein pool level. In contrast, the dramatic increase of NDUFV1nitration suggests that this modification may be a combination of both irreversible (oxidative damage) and reversible (signaling) modification and will require further study [34,49].

Although oxidative damage to the ETC complexes in vitro leads to a decline in enzyme function [50–55], and this correlates with the amount of damaging adducts, the in vivo modification of several complex proteins did not severely affect their activity. Thus, the 7–10 fold increase in nitration of NDUFV1 and increased carbonylation of COX4, with age, did not severely affect either CI or CIV function suggesting that if the modification caused a structural change(s) this did not affect their function.

CIII is also a major site of ROS production in vitro [25,56]. Since, Core 1 and Core 2 span the entire inner mitochondrial membrane and are in proximity to the predicted site of ROS generation at CIII [56], it is not surprising that they are both targets of oxidative modifications. However, the differential Core 2 carbonylation, and Core 1 HNE modification and nitration raises the question of the physiological environment that supports adduct specific multiple types of modification of specific subunits. Thus, dramatically increased Core 1 nitration and decreased Core 2 carbonylation with age suggests highly localized and specific environmental conditions for such modifications. Despite the heavy Core 1 nitration in both middle and old age, the CIII enzyme function did not change and in fact it increased slightly at old age, suggesting that the Core 1 nitration does not affect CIII activity. Interestingly, Core 1 and Core 2 proteins have a dual function in CIII, i.e., they play a key role in providing structural stability to the complex as well as being members of the Mitochondrial Processing Peptidase (MPP) family that are involved in processing and proper folding of proteins imported into the matrix [57]. If increased Core 1 nitration is due to oxidative damage, a decrease of MPP activity could result in impairment of protein processing and increased age-associated mitochondrial dysfunction that is not related to ETC function.

Although F1F0-ATP synthase of CV is not part of the ETC processes, its location within the matrix, as well as its abundance make it a prime candidate for oxidative modification. Thus, any change in CV activity is important because of its role in ATP homeostasis. Although the α-chain is oxidatively damaged, the fact that the HNE-modified α-chain was only found to co-migrate with CI (and not in the intact CV) suggests that the modification causes its dissociation from CV. Thus, removal of the oxidatively damaged α-chain and its replacement with unmodified protein may be a protective mechanism. This implies, however, that the modification and dissociation would trigger de novo α-chain synthesis, which remains to be tested. Alternatively, failure to replace the dissociated α-chain may account for the decreased ATP production, which is a hallmark of increasing mitochondrial dysfunction with aging. Previously, it has been shown that MDA modified β-chain is associated with decreased heart CV function with age [33]. Since, we did not find MDA-modified β-chain in BN-PAGE separated CV suggests that it may have dissociated from the intact complex. Thus, we propose that the modifications of the α- and β-chains may alter their binding affinity for CV and that dissociation of both modified proteins from CV may be a protective function.

The specific and dramatic 10-fold increase of β-chain nitration correlates directly with the decline in CV function with aging. Interestingly, the major decrease in enzyme function which occurs at middle age does not correlate with the continued modification of the β-chain with age, suggesting that the specificity of the modifications rather than abundance may be a determinant of the consequences of modification to ETC and mitochondrial function.

In conclusion, many of the ETC complex subunits are specific targets of ROS-mediated oxidative modifications some of which cause a decline in function. In this study we have reported two novel consequences of oxidative modification in aged heart mitochondria. First, the dissociation of modified CV subunits raises the question of whether structural changes due to modification affect their assembly with CV. Secondly, modification of Core 1 and Core 2 MPP may elicit a protein misfolding stress response that contributes to mitochondrial dysfunction and an increased state of oxidative stress in aged heart tissue. We propose, therefore, that the overall effect of increased oxidative modification of components of the ETC complexes may be an underlying mechanism to the development of age-associated state-of-chronic stress and cause increased mitochondrial dysfunction leading to tissue dysfunction. Our study provides important insight into physiological effects of oxidative modifications on mitochondrial function and their role in aging.

Acknowledgments

This publication was supported by U.S.P.H.S. grant 1P01 AG021830-04 awarded by the National Institute on Aging, and the U.S.P.H.S. grant 1 P30 AG024832-03, the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center grant awarded by the National Institute on Aging, and by the Sealy Center on Aging.

Abbreviations

- ATP5A1

complex V α chain

- ATP5B

complex V β chain

- BN-PAGE

blue-native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- CI

complex I

- CII

complex II

- CIII

complex III

- CIV

complex IV

- CV

complex V

- COX4

cytochrome c oxidase subunit 4

- DNP

2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazone

- DNPH

2,4-dinitrophenylhydrazine

- ETC

electron transport chain

- HNE

4-hydroxynonenal

- MALDI-TOF-TOF

matrix-assisted laser disorption/ionization – time of flight-time of flight

- MDA

malondialdehyde

- MPP

mitochondrial processing peptidase

- NDUFS1

NADH dehydrogenase Fe-S subunit 1

- NDUFV1

NADH dehydrogenase flavoprotein subunit 1

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- SDHA

succinate dehydrogenase subunit 1

- UQCRC1

Core 1 subunit

- UQCRC2

Core 2 subunit

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lesnefsky EJ, Hoppel CL. Review: Oxidative phosphorylation and aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2006;5:402–433. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suh JH, Heath SH, Hagen TM. Two populations of mitochondria in the aging rat heart display heterologous levels of oxidative stress. Free Radic Biol Med. 2003;35:1064–1072. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(03)00468-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lesnefsky EJ, Gallo DS, Ye J, Whittingham JS, Lust WD. Aging increases ischemia-reperfusion injury in the isolated buffer-perfused heart. J Lab Clin Med. 1994;124:843–851. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen Q, Hoppel CL. Ischemia reperfusion injury in the aged heart: role of mitochondria. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2003;420:287–297. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2003.09.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sugioka K, Nakano M, Totsune-Nakano H, Minakami H, Tero-Kubota S, Ikegami Y. Mechanism of O2-generation in reduction and oxidation cycle of ubiquinones in a model of mitochondrial electron transport systems. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1988;936:377–385. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(88)90014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: Central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turrens JF, Boveris A. Generation of superoxide anion by the NADH dehydrogenase of bovine heart mitochondria. Biochem J. 1980;191:421–427. doi: 10.1042/bj1910421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grigorieff N. Structure of the respiratory NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I) Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1999;9:476–483. doi: 10.1016/S0959-440X(99)80067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choksi KB, Nuss JE, Boylston WH, Rabek JP, Papaconstantinou J. Age-related increases in oxidatively damaged proteins of mouse kidney mitochondrial electron transport chain complexes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007;43:1423–1438. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.St-Pierre J, Buckingham JA, Roebuch SJ, Brand MD. Topology of superoxide production from different sites in the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:44784–44790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M207217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Trumpower BL. The proton motive Q cycle. Energy transduction by coupling of proton translocation to electron transfer by the cytochrome bc1 complex. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:11409–11413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Demin OV, Kholodenko BN, Akulachev VP. A model of O2.-generation in the complex III of the electron transport chain. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;184:21–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:49064–49073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407715200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gille L, Nohl H. The ubiquinol/bc1 redox couple regulates mitochondrial oxygen radical formation. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2001;388:34–38. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Han D, Antunes F, Canali R, Rettori D, Cadenas E. Voltage-dependent anion channels control the release of the superoxide anion from mitochondria to cytosol. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:5557–5563. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M210269200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harman D. Aging: a theory based on free radical and radiation chemistry. J Gerontol. 1956;11:298–300. doi: 10.1093/geronj/11.3.298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harman D. The biologic clock: the mitochondria? J Am Geriatr Soc. 1972;20:145–147. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1972.tb00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenaz G. Role of mitochondria in oxidative stress and ageing. Biochim Biphys Acta. 1998;1366:53–67. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(98)00120-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finkel T, Holbrook NJ. Oxidants, oxidative stress and the biology of ageing. Nature. 2000;408:239–247. doi: 10.1038/35041687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Huang H, Manton KG. The role of oxidative damage in mitochondria during aging: a review. Front Biosci. 2004;9:1100–1117. doi: 10.2741/1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Y, Fiskum G, Schubert D. Generation of reactive oxygen species by the mitochondrial electron transport chain. J Neurochem. 2002;80:780–787. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2002.00744.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lenaz G, Bovina C, D’Aurelio M, Fato R, Formiggini G, Genova ML, Giuliano G, Merlo PM, Paolucci U, Parenti CG, Ventura B. Role of mitochondria in oxidative stress and aging. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;959:199–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb02094.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen Q, Vazquez EJ, Moghaddas S, Hoppel CL, Lesnefsky EJ. Production of reactive oxygen species by mitochondria: central role of complex III. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:36027–36031. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M304854200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yano T, Magnitsky S, Ohnishi T. Characterization of the complex I-associated ubisemiquinone species: toward the understanding of their functional roles in the electron/proton transfer reaction. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2000;1459:299–304. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(00)00164-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han D, Williams E, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial respiratory chain-dependent generation of superoxide anion and its release into the intermembrane space. Biochem J. 2001;353:411–416. doi: 10.1042/0264-6021:3530411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choksi KB, Boylston WH, Rabek JP, Widger WR, Papaconstantinou J. Oxidatively damaged proteins of heart mitochondrial electron transport complexes. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2004;1688:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2003.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wei YH. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial DNA mutations in human aging. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1998;217:53–63. doi: 10.3181/00379727-217-44205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Uchida K, Stadtman ER. Modification of histidine-residues in proteins by reaction with 4-hydroxynonenal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:4544–4548. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Uchida K, Stadtman ER. Selective cleavage of thioether linkage in proteins modified with 4-hydroxynonenal. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:5611–5615. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.12.5611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Berlett BS, Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation in aging, disease, and oxidative stress. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:20313–20316. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.33.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Beal MF. Oxidatively modified proteins in aging and disease. Free Rad Biol Med. 2002;32:797–803. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(02)00780-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rabek JP, Boylston WH, III, Papaconstantinou J. Carbonylation of ER chaperone proteins in aged mouse liver. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:566–572. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00826-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.An MR, Hsieh CC, Reisner PD, Rabek JP, Scott SG, Kuninger DT, Papaconstantinou J. Evidence for posttranscriptional regulation of C/EBPalpha and C/EBPbeta isoform expression during the lipopolysaccharide-mediated acute-phase response. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2295–2306. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stadtman ER. Protein oxidation in aging and age-related diseases. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;928:22–38. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2001.tb05632.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yarian CS, Rebrin I, Sohal RS. Aconitase and ATP synthase are targets of malondialdehyde modification and undergo an age-related decrease in activity in mouse heart mitochondria. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;330:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.02.135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rajapakse N, Shimizu K, Payne M, Busija D. Isolation and characterization of intact mitochondria from neonatal rat brain. Brain Res Protoc. 2001;8:176–183. doi: 10.1016/s1385-299x(01)00108-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kwong LK, Sohal RS. Age-related changes in activities of mitochondrial electron transport complexes in various tissues of the mouse. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;373:16–22. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jarreta D, Orus J, Barrientos A, Miro O, Roig E, Heras M, Moraes CT, Cardellach F, Casademont J. Mitochondrial function in heart muscle from patients with idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;45:860–865. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(99)00388-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schagger H. Native electrophoresis for isolation of mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation protein complexes. Methods Enzymol. 1995;260:190–202. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)60137-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Venkatraman A, Landar A, Davis AJ, Chamlee L, Sanderson T, Kim H, Page G, Pompilius M, Ballinger S, Darley-Usmar V, Bailey SM. Modification of the mitochondrial proteome in response to the stress of ethanol-dependent hepatotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:22092–22101. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402245200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Levine RL, Williams JA, Stadtman ER, Shacter E. Carbonyl assays for determination of oxidatively modified proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1994;233:346–357. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(94)33040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yoshikawa S, Shinzawa-Itoh K, Tsukihara T. Crystal structure of bovine heart cytochrome c oxidase at 2.8 A resolution. J Bioenerg Biomembr. 1998;30:7–14. doi: 10.1023/a:1020595108560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Torii K, Sugiyama S, Takagi K, Satake T, Ozawa T. Age-related decrease in respiratory muscle mitochondrial function in rats. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1992;6:88–92. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/6.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Andreu AL, Arbos MA, Perez-Martos A, Lopez-Perez MJ, Asin J, Lopez N, Montoya J, Schwartz S. Reduced mitochondrial DNA transcription in senescent rat heart. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;252:577–581. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barazzoni R, Short KR, Nair KS. Effects of aging on mitochondrial DNA copy number and cytochrome c oxidase gene expression in rat skeletal muscle, liver, and heart. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:3343–3347. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.5.3343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Miro O, Casademont J, Casals E, Perea M, Urbano-Marquez A, Rustin P, Cardellach F. Aging is associated with increased lipid peroxidation in human hearts, but not with mitochondrial respiratory chain enzyme defects. Cardiovasc Res. 2000;47:624–631. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(00)00122-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marin-Garcia J, Ananthakrishnan R, Goldenthal MJ. Human mitochondrial function during cardiac growth and development. Mol Cell Biochem. 1998;179:21–26. doi: 10.1023/a:1006839831141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sugiyama S, Takasawa M, Hayakawa M, Ozawa T. Changes in skeletal muscle, heart and liver mitochondrial electron transport activities in rats and dogs of various ages. Biochem Mol Biol Int. 1993;30:937–944. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Johnson JE, Jr, Choksi K, Widger WR. NADH-Ubiquinone oxidoreductase: substrate-dependent oxygen turnover to superoxide anion as a function of flavin mononucleotide. Mitochondrion. 2003;3:97–110. doi: 10.1016/S1567-7249(03)00084-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koeck T, Fu X, Hazen SL, Crabb JW, Stuehr DJ, Aulak KS. Rapid and selective oxygen-regulated protein tyrosine denitration and nitration in mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:27257–27262. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401586200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bautista J, Corpas R, Ramos R, Cremades O, Gutierrez JF, Alegre S. Brain mitochondrial complex I inactivation by oxidative modification. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2000;275:890–894. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Murray J, Taylor SW, Zhang B, Ghosh SS, Capaldi RA. Oxidative damage to mitochondrial complex I due to peroxynitrite: identification of reactive tyrosines by mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:37223–37230. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lashin OM, Szweda PA, Szweda LI, Romani AM. Decreased complex II respiration and HNE-modified SDH subunit in diabetic heart. Free Radic Biol Med. 2006;40:886–896. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2005.10.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen J, Schenker S, Frosto TA. Henderson GIInhibition of cytochrome c oxidase activity by 4-hydroxynonenal (HNE). Role of HNE adduct formation with the enzyme subunits. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1998;1380:336–344. doi: 10.1016/s0304-4165(98)00002-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chen J, Henderson GI, Freeman GL. Role of 4-hydroxynonenal in modification of cytochrome c oxidase in ischemia/reperfused rat heart. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2001;33:1919–1927. doi: 10.1006/jmcc.2001.1454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Picklo MJ, Amarnath V, McIntyre JO, Graham DG, Montine TJ. 4-Hydroxy-2(E)-nonenal inhibits CNS mitochondrial respiration at multiple sites. J Neurochem. 1999;72:1617–1624. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1999.721617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zhang L, Yu L, Yu CA. Generation of superoxide anion by succinate-cytochrome c reductase from bovine heart mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:33972–33976. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.51.33972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Deng K, Shenoy SK, Tso SC, Yu L, Yu CA. Reconstitution of mitochondrial processing peptidase from the core proteins (subunits I and II) of bovine heart mitochondrial cytochrome bc(1) complex. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6499–6505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007128200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]