Abstract

We have examined the interaction parameters, conformation, and functional significance of the human MutSα· proliferating cell nuclear antigen (PCNA) complex in mismatch repair. The two proteins associate with a 1:1 stoichiometry and a KD of 0.7 μm in the absence or presence of heteroduplex DNA. PCNA does not influence the affinity of MutSα for a mismatch, and mismatch-bound MutSα binds PCNA. Small angle x-ray scattering studies have established the molecular parameters of the complex, which are consistent with an elongated conformation in which the two proteins associate in an end-to-end fashion in a manner that does not involve an extended unstructured tether, as has been proposed for yeast MutSα and PCNA (Shell, S. S., Putnam, C. D., and Kolodner, R. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 26 ,565 -578). MutSα variants lacking the PCNA interaction motif are functional in 3′- or 5′-directed mismatch-provoked excision, but display a partial defect in 5′-directed mismatch repair. This finding is consistent with the modest mutability conferred by inactivation of the MutSα PCNA interaction motif and suggests that interaction of the replication clamp with other repair protein(s) accounts for the essential role of PCNA in MutSα-dependent mismatch repair.

Mismatch repair rectifies DNA biosynthetic errors, mediates several recombination-associated phenomena, and in mammalian cells participates in an early step of the cellular response to certain classes of DNA damage (reviewed in Refs. 1 and 2). Defects in the human pathway are the cause of hereditary non-polyposis colorectal cancer and have been implicated in the development of a subset of sporadic tumors.

A strand-specific mismatch repair reaction that is presumably responsible for replication error correction has been studied in mammalian cell extracts and in several purified systems. A number of activities have been implicated in this pathway, including MutSα (MSH2·MSH6 heterodimer), MutSβ (MSH2·MSH3), MutLα (MLH1·PMS2), Exo1, replication protein A, HMGB1, PCNA,2 RFC, and DNA polymerase δ. This reaction can be conceptually divided into three steps: mismatch recognition, excision, and repair DNA synthesis/ligation. The replication clamp PCNA functions at several stages of this multistep reaction. It participates in the DNA synthesis phase of repair (3), consistent with its function as a cofactor for DNA polymerase δ (4). PCNA is also necessary during an early step of the reaction (5) and has been shown to interact with activities implicated in early steps of repair (6-11). However, the significance of these various PCNA interactions is not clear. Analysis of PCNA involvement in mismatch repair has emphasized the MutSα·PCNA complex, which has been suggested to be a key intermediate in mismatch repair. A conserved QXX(L/I)XXFF motif near the N terminus of MSH6 has been implicated in this interaction (6-8). A human MutSα variant lacking the MSH6 N-terminal 77 amino acids including the QXX(L/I)XXFF motif is severely compromised in its ability to support mismatch repair in vitro (8), but alanine substitution of conserved residues within the PCNA interaction motif of yeast Msh6 results in only a modest increase in mutability (6, 7). The implications of the MutSα-PCNA interaction for the mechanism of mismatch repair are also uncertain. Biochemical analyses have indicated that yeast PCNA enhances the specific affinity of yeast MutSα for a mismatch (7), but a subsequent study concluded that although PCNA, MutSα, and homoduplex DNA form a stable ternary complex, binding to a mismatch leads to disruption of the MutSα-PCNA interaction (12). These two conclusions appear to be at odds with thermodynamic expectations: if PCNA increases the affinity of MutSα for a mispair, then a mismatch should increase the affinity of PCNA for MutSα.

This study further clarifies the nature and function of the human MutSα-PCNA interaction. We show that MutSα binds PCNA with a stoichiometry of 1:1, adopting an elongated conformation in solution, and that the affinity of this interaction is not significantly affected by mismatch binding. Abrogation of the MutSα-PCNA interaction has little effect on 5′- or 3′-directed mismatch-provoked excision. However, 5′-directed repair is partially attenuated under these conditions.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

MutSα-expressing Baculoviral Constructs—A baculoviral expression vector that expresses full-length MSH2 and an N-terminally truncated form of MSH6 (MSH6Δ12) was prepared by PCR mutagenesis from the previously described pFastbacDual-MSH2-MSH6 (13). The resulting pFastbacDual-MSH2-MSH6Δ12 encodes amino acids 13-1361 of full-length MSH6, beginning with NH2-Met-Pro-Lys-Ser, and was used to generate a baculovirus according to the protocol of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Recombinant virus was plaque-purified, and high titer stocks were produced, which were used to infect Sf9 insect cells for protein expression.

DNAs and Proteins—Circular heteroduplex DNAs contained a single G-T mismatch (A·T in homoduplex controls) and a strand discontinuity located either 3′ or 5′ to the mismatch (9). The DNAs used in SPRS, magnetic bead assays, and equilibrium gel filtration were 21-, 41-, or 201-bp duplexes containing a centrally located G-T mismatch (or A·T base pair) flanked by sequences corresponding to those in the circular substrates described above (13). For nitrocellulose filter binding assays, synthetic 41-bp hetero- and homoduplex DNAs were prepared by annealing high pressure liquid chromatography-purified 5′-32P-labeled T-containing strand with an equimolar amount of unlabeled purified A- or G-containing strand. The substrates used in SPRS and magnetic bead assays contained a 5′-biotin tag on the T-containing strand.

Recombinant MutSα, MSH2·Δ12 (referred to below as MutSαΔ12), and MutLα were isolated according to Blackwell et al. (13), and MSH2·Δ341 (referred to below as MutSαΔ341) according to Warren et al. (14). MutSα isolated from HeLa cell nuclear extracts (15) was used in some experiments. Isolates of MutSα and its variants typically contained ∼1 mol of ADP/mol of heterodimer. Exo1 and replication protein A (16), RFC (9), native PCNA (17), His6-PCNA (18), and p21 (19) were isolated as described. MutSα and PCNA concentrations, which are expressed as heterodimer and homotrimer equivalents, respectively, were determined by the method of Gill and von Hippel (20), which yielded extinction coefficients at 280 nm of 208,465 (MutSα), 206,975 (MutSαΔ12), 171,650 (MutSαΔ341), and 50,040 (PCNA) m-1 cm-1.

Analyses of Protein·Protein and Protein·DNA Assemblies—Gel filtration at 4 °C employed a 2.4-ml Superdex 200 PC 3.2 column on anÄKTA Purifier 10 HPLC system (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with 25 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5 (or 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.6), 5 mm MgCl2, 125 mm NaCl, and 0.1 mm dithiothreitol. The column was calibrated using blue dextran (excluded volume) and standards of known Stokes radii (GE Healthcare): apoferritin (67.1 Å), aldolase (48.1 Å), and albumin (35.5 Å). For equilibrium gel filtration, the Superdex 200 column was equilibrated with PCNA as indicated (or a mixture of PCNA and a 21-bp G-T heteroduplex). A 10-μl sample of MutSα in equilibration buffer was injected, and the column was developed at 0.02 ml/min. The eluate was monitored at 280, 260, and 230 nm as indicated and/or collected in 0.025-ml fractions, which were analyzed by SDS-PAGE.

Bead-linked DNA assay was used to score MutSα·PCNA complexes on DNA. A slurry of Dynabeads M-280 streptavidincoated magnetic beads (1 ml; Invitrogen) was derivatized by resuspension in 1 ml of 10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 500 mm KCl, and 1 mm EDTA containing 1 nmol of 41-bp homoduplex or G-T heteroduplex DNA. For binding assays, 18 μl of derivatized beads were washed and resuspended in 90 μl of 25 m m HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, and 100 mm KCl containing 400 nm MutSα and 1 μm PCNA. After incubation for 10 min at 4 °C, beads were collected and washed with assay buffer, and bound protein was eluted with 25 μl of 25 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, and 400 mm NaCl, followed by SDS-PAGE analysis.

MutSα binding to 41-bp homoduplex and heteroduplex DNAs was scored by the DEAE-nitrocellulose paper double-filter method (21). Reactions (50 μl) contained 25 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 150 mm NaCl, 5 mm MgCl2, 1 mm dithiothreitol, 1 nm 32P-labeled 41-bp G-T heteroduplex or A·T homoduplex DNA, and MutSα and PCNA as indicated. After 20 min at 4 °C, the solution was applied to a stacked filter set, which had been prewashed twice with 100 μl of binding buffer, and drawn through under 30 kilopascals of vacuum. Nitrocellulose and DEAE filters were dried, and radioactivity bound to each was quantitated using a PhosphorImager.

SPRS was performed on a Biacore 2000. Interaction of MutSα or p21 with PCNA in the absence of DNA was analyzed in 25 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 125 mm NaCl, and 1 mm EDTA using a Ni2+-NTA chip derivatized with His6-PCNA (100-200 response units). Interaction of PCNA with DNA-bound MutSα was evaluated by two-phase protein flow (20 μl/min) over a streptavidin chip derivatized with biotin-tagged 201-bp homoduplex or heteroduplex DNA in 25 mm HEPES-NaOH, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 150 mm NaCl, 0.02% surfactant P20, and 1 mm dithiothreitol. In the first phase, 200 nm MutSα was allowed to flow for 5 min, followed immediately by a second phase wherein 200 nm MutSα supplemented with 0.025-2.5 μm PCNA was allowed to flow for an additional 5 min.

SAXS Experiments—SAXS was performed on Sibyls beam-line 12.3.1 at the Advanced Light Source. Protein samples were dialyzed against 25 mm HEPES-KOH, pH 7.5, 5 mm MgCl2, 150 mm KCl, and 2 mm dithiothreitol. Scattering intensities (I) were determined at multiple protein concentrations (10-50 μm) as a function of the scattering vector Q = 4πsinθ/λ, where 2θ is the scattering angle, and λ is the wavelength of the incident beam, and corrected for background scattering using dialysis buffer. Forward scattering intensities (I(0)) were calculated from Guinier plots (ln I versus Q2) (22) of scattering data normalized for concentration (mass/volume). Radii of gyration (Rg) were determined by Guinier plot from scattering curves extrapolated to zero concentration using the program PRIMUS (23).

Composite scattering curves were generated with PRIMUS by scaling and merging background-corrected high Q region data from higher concentration samples (20-50 μm) with low Q region zero-extrapolated data. Scattering curves were subjected to indirect Fourier transform using the GNOM program (24) to yield the pair distribution function (P(r)), from which maximum particle dimensions (Dmax) and Rg were derived (25). GNOM output files were also used to generate low resolution ab initio models of the proteins using the dummy atom approach as implemented in DAM-MIN (26) or GASBOR (27). Unless noted otherwise, at least 10 independent shape reconstructions were performed for each data set. Individual models were aligned by SUPCOMB (28) and averaged by DAMAVER (29) to yield the most probable conformation.

Mismatch Repair and Excision Assays—Mismatch repair and excision assays in nuclear extracts were performed as described (16, 30). 5′-Directed (31) or 3′-directed (9) mismatch-provoked excision in purified systems and MutSα-, RFC-, and PCNA-dependent MutLα endonuclease activation (32) were scored as described.

RESULTS

MutSα and PCNA Form a 1:1 Complex—The interaction of human MutSα with PCNA has been qualitatively documented (3, 8, 9), but quantitative features of the interaction have not been addressed. To determine the stoichiometry of the MutSα-PCNA interaction, we attempted to isolate a MutSα·PCNA complex by gel filtration. Purified preparations of MutSα and PCNA eluted from Superdex 200 gel with retention times corresponding to Stokes radii of 67 and 40 Å, respectively (Table 1), in agreement with previous findings (15, 33). However, preincubation of MutSα (1-8 μm) with PCNA (1-16 μm) followed by gel filtration of the mixture failed to indicate interaction of the two proteins as judged by UV elution profile, and we were unable to detect PCNA in column fractions containing MutSα by SDS gel electrophoresis (data not shown).

TABLE 1.

Biophysical properties of MutSα and PCNA derived from SAXS and gel filtration

Rg and Dmax were derived from SAXS data, and Stokes radii were determined by gel filtration (see “Experimental Procedures”). Calculated Rg values were determined from crystal structures (44). Dmax values shown in parentheses were calculated from the corresponding crystal structures (44). The C termini of MutSαΔ341 (~80 residues) are not well ordered in the crystal structure and are therefore not included in the calculations.

|

Sample |

Molecular mass |

SAXS |

Gel filtration, Stokes radius |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rg calculated | Rg Guinier | RgP(r) | Dmax | |||

| kDa | Å | Å | ||||

| MutSα | 258 | 59 ± 1 | 57 ± 0.2 | 202 | 67 | |

| MutSαΔ12 | 256 | 57 ± 0.4 | 58 ± 0.1 | 199 | 67 | |

| MutSαΔ341 | 220 | 46 ± 0.3 | 46 ± 0.1 | 145 | 60 | |

| MutSαΔ341·G-T | 230 | 42 | 44 ± 0.1 | 43 ± 0.1 | 140 (130) | |

| PCNA | 86 | 34 | 33 ± 0.1 | 34 ± 0.1 | 92 (97) | 40 |

| MutSα + PCNA (1:1) | 343 | 69 ± 0.5 | 67 ± 0.3 | 234 | 80 | |

These findings suggested that the MutSα-PCNA interaction is characterized by a modest affinity and/or a short lifetime. We therefore examined this interaction by equilibrium gel filtration (34). A Superdex 200 column pre-equilibrated with a uniform concentration of PCNA was injected with a known amount of MutSα. Association of MutSα and PCNA results in depletion of PCNA at its retention volume, which is manifested as a trough in UV absorbance. The amount of PCNA bound to MutSα was determined from the area of the trough and extinction coefficients of the two proteins. Fig. 1A shows elution profiles for filtration of a 10-μl sample of 8 μm MutSα on a column preequilibrated with 0.25-1.5 μm PCNA. Trough areas at the PCNA elution volume (∼1.35 ml) were used to determine the moles of PCNA bound per mol of MutSα. A plot of these values against PCNA concentration fit well to a hyperbola with a KD of 0.7 μm and a stoichiometry of 1.0 PCNA trimer/recombinant MutSα heterodimer (Fig. 1B). Essentially identical values (0.8 μm and 1:0.94) were obtained using MutSα isolated from HeLa cells. These results were verified by SPRS analyses in which excess recombinant MutSα was flowed over a Ni2+-NTA chip containing immobilized His6-PCNA (Fig. 1C). Such experiments yielded a KD of 0.5 μm and a stoichiometry of 1 MutSα heterodimer/PCNA trimer. By contrast, analysis of recombinant p21 binding to a His6-PCNA chip at a concentration several hundred times the KD yielded a stoichiometry of three molecules of p21/PCNA trimer (Fig. 1C, inset), consistent with previous findings (35).

FIGURE 1.

Equilibrium formation of a 1:1 complex between the MutSα heterodimer and the PCNA trimer. A, interaction of MutSα and PCNA was analyzed by equilibrium gel filtration (see “Experimental Procedures”). Ten-μl samples containing 8 μm MutSα and 0.25-4 μm PCNA were loaded onto a Superdex 200 column equilibrated with 0.25 (black), 0.5 (blue), 1 (green), 1.5 (orange), or 4 (red) μm PCNA. The trough at 1.35 ml resulted from depletion of PCNA because of its association with MutSα. Formation of the MutSα·PCNA complex was associated with a decrease in the retention volume of the MutSα peak from 1.07 ml at 0.25 μm PCNA to 1.025 ml at 4 μm PCNA (inset). B, PCNA trimer binding to recombinant MutSα (•), HeLa cell MutSα (▴), or MutSαΔ12 (▪) was determined as described for A as a function of free PCNA concentration. Isotherms shown for MutSα-PCNA interaction were determined by nonlinear least squares fit of the data to a rectangular hyperbola. The increase in the apparent Stokes radius of the MutSα peak with increasing PCNA concentration in also shown (○). C, MutSα-PCNA interaction under conditions of MutSα excess was assessed by SPRS. Solutions of 0.2-2 μm MutSα were flowed over a Ni2+-NTA sensor chip derivatized with ∼200 response units of His6-tagged PCNA. Molar stoichiometries were calculated assuming that 1 response unit of MutSα (258 kDa) corresponds to 0.33 response units for the PCNA trimer (86 kDa). Data were fit to a rectangular hyperbola. The inset shows sensorgram results of an experiment in which 1 μm recombinant p21 was flowed over a Ni2+-NTA chip containing 100 response units of His6-PCNA.

MutSα·PCNA Complex Formation Requires the PCNA Interaction Motif of MSH6—The MSH6 polypeptide contains distinct structural domains (Fig. 2A) and harbors a PCNA interaction motif (QXX(L/I)XXFF) near the N terminus that has been implicated in MutSα-PCNA interaction (6-8). To evaluate the contributions of this motif to interaction affinity and biological function, we prepared MutSα derivatives lacking this motif: MutSαΔ341 (14) and MutSαΔ12 (see “Experimental Procedures”). Both form stable heterodimers, and the structure of MutSαΔ341 is known (14). The Stokes radii of MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 were determined by gel filtration chromatography to be 67 and 60 Å, respectively (Table 1), consistent with the previously determined Stokes radius of native MutSα (15). This finding and the results of SAXS and DNA binding studies described below suggest that deletion of the PCNA-binding motif does not significantly alter the conformation or stability of MutSα.

FIGURE 2.

MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 are proficient in mismatch binding, but defective in PCNA interaction. A, the schematic depicts the domain organization of MSH6, MSH6Δ12, and MSH6Δ341, all of which contain domains I-V (14). The N-terminal PCNA-binding motif (gray box) is lacking in MSH6Δ12 and MSH6Δ341. The N-terminal amino acid sequences are shown for full-length MSH6 and MSH6Δ12. Recombinant full-length MSH6 used in this study contained a Gly at position 2 that was introduced during cloning of the gene (S. Gradia and R. Fishel, personal communication). B, MutSαΔ12 (9 μm in column load) was subjected to equilibrium gel filtration on a column equilibrated with 1 μm (solid line) or 4 μm (dotted line) PCNA as described in the legend to Fig. 1. C, shown are the results from SDS-PAGE analysis of PCNA binding to MutSα variants bound to magnetic bead-linked 41-bp G-T heteroduplex or A·T homoduplex DNA (see “Experimental Procedures”).

The capacity of MutSαΔ12 to bind PCNA was also examined by equilibrium gel filtration (Fig. 2B). Interaction of the two proteins was not detectable by this method (Fig. 1B), indicating that deletion of the N-terminal PCNA-binding motif of MSH6 reduces the interaction affinity of the two proteins by at least 10-fold. The PCNA-binding defects of MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 were also assessed by pulldown assay using magnetic beads derivatized with G-T heteroduplex or A·T homoduplex DNA (Fig. 2C). Binding of PCNA to A·T or G-T beads in the absence of other proteins was not detectable (lanes 1 and 2). However, PCNA was captured by G-T beads if MutSα was present (lane 4) and was also retained at low levels on A·T beads in the presence of MSH2·MSH6 (lane 3). Although the extent of retention of MutSαΔ341 and MutSαΔ12 by the bead-linked DNAs was comparable with that of native MutSα, PCNA was not detectably retained in the presence of either of the truncated proteins (lanes 5-8).

Affinity and Stoichiometry of the DNA·MutSα·PCNA Complex—The influence of DNA binding by MutSα on its ability to associate with PCNA was also assessed by equilibrium gel filtration and SPRS. Fig. 3A shows elution profiles for filtration of a 10-μl sample of 4 μm MutSα through a column pre-equilibrated with a 21-bp G-T heteroduplex (800 nm) and variable concentrations of PCNA. Absorbance profiles showed the presence of two troughs representing simultaneous depletion of PCNA and DNA, due to their association with MutSα. Measurement of trough areas revealed that 1 heteroduplex was bound per MutSα heterodimer. Binding of PCNA to the MutSα·DNA complex was hyperbolic with respect to PCNA concentration, characterized by a KD of 0.6 μm and a stoichiometry of 1:1:1 for the DNA·MutSα·PCNA complex (Fig. 3B).

FIGURE 3.

MutSα-PCNA interaction occurs on heteroduplex DNA. A, interaction of MutSα and PCNA in the presence of heteroduplex DNA was analyzed by equilibrium gel filtration as described in the legend to Fig. 1 except that the column was equilibrated with a mixture of 800 nm DNA and 0.25 (black line), 0.5 (blue line), 1.5 (orange line), or 4 (red line) μm PCNA. The column was loaded with 10-μl samples containing 4μm MutSα, 800 nm DNA, and 0.25, 0.5, 1.5, or 4 μm PCNA, and eluate absorbance was monitored at 230 and 260 nm. Troughs at 1.35 and 1.61 ml are the result of depletion of free DNA and free PCNA, respectively, because of their association with MutSα. In the absence of PCNA (gray line), a single trough corresponding to DNA depletion due to MutSα binding was observed. B, PCNA (•) and DNA (○) bound per mol of MutSα were determined as a function of free PCNA concentration from the experiments shown in A by measurement of trough areas at 230 (PCNA) and 260 (DNA) nm. Data for interaction of the MutSα·DNA complex with PCNA were fit to a rectangular hyperbola as described in the legend to Fig. 1. Formation of the ternary complex was also evident as a decrease in retention volume of the MutSα·DNA peak (A), corresponding to an increase in the apparent Stokes radius (□). C, PCNA effects on MutSα affinities for 41-bp G-T heteroduplex (open symbols) or A·T homoduplex (closed symbols) DNA were evaluated by nitrocellulose filter binding assay (see “Experimental Procedures”). Reactions contained MutSα (○ and •), MutSαΔ12 (□ and ▪), or 10 μm PCNA plus MutSα (▵ and ▴) as indicated.

PCNA interaction with DNA-bound MutSα was also examined by SPRS using 201-bp G-T and A·T DNAs (supplemental Fig. 1A). Supplementation of a 200 nm MutSα flow with 2.5 μm PCNA over a heteroduplex-derivatized sensor chip resulted in an increase in bound mass above that observed with MutSα alone. This mass increase displayed saturation behavior with increasing PCNA concentration, with a limiting stoichiometry corresponding to 1 PCNA trimer/MutSα heterodimer (supplemental Fig. 1B) and an apparent KD of 100 nm. Mismatch dependence of MutSα binding under these conditions was 3-4-fold, and no significant PCNA binding to the DNA chip was observed in the absence of MutSα (supplemental Fig. 1A). The KD for PCNA binding to DNA-bound MutSα observed in these experiments is significantly less than that obtained by equilibrium gel filtration. This may be due to the restricted order of ternary complex assembly in the SPRS experiments (PCNA binding to DNA-bound MutSα as opposed to the gel filtration experiments, in which MutSα can bind either PCNA or DNA prior to ternary complex assembly). However, the KD difference could also be due to avidity and/or rebinding effects in SPRS experiments. Such effects, which have been previously observed in biosensor studies involving flow of a multivalent biomolecule like PCNA over a surface derivatized with a monovalent binding partner, result in anomalously high apparent affinities (36).

A previous study indicated that yeast PCNA increases the affinity of yeast MutSα for a mismatch (7). However, it has also been reported that although yeast PCNA forms a complex with homoduplex-bound yeast MutSα, the trimeric clamp is excluded from the yeast MutSα·mismatch complex (12). Because these two conclusions are at odds with thermodynamic expectations and because we have found that human PCNA binds readily to the MutSα·mismatch complex, we used a nitrocellulose membrane assay to evaluate the effects of human PCNA on the heteroduplex and homoduplex affinities of human MutSα. As shown in Fig. 3C, the affinities and mismatch dependence of DNA binding by MutSα were comparable when determined in the absence or presence of a large excess of the replication clamp.

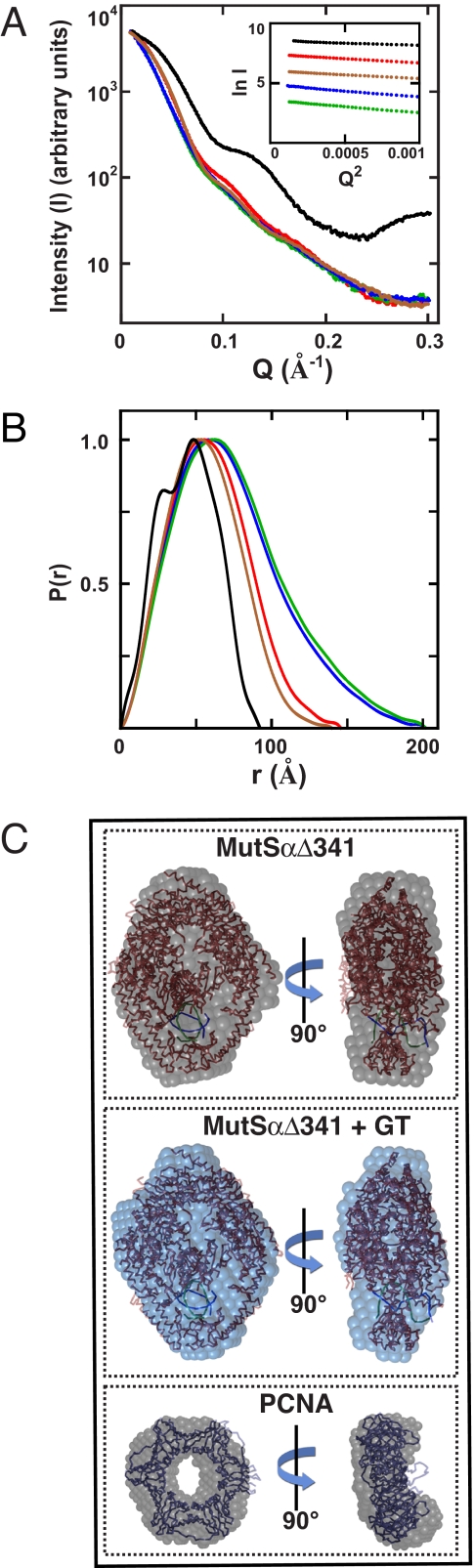

SAXS Studies of MutSα, PCNA, and the MutSα·PCNA Complex—We used SAXS to probe solution conformations of native MutSα and the MutSα·PCNA complex. Fig. 4A shows solution x-ray scattering profiles (I versus Q) for MutSα, MutSαΔ12, MutSαΔ341, PCNA, and MutSαΔ341 complexed to a 15-bp G-T heteroduplex. The corresponding distributions of pairwise interatomic vectors (P(r)) were obtained from scattering profiles by indirect Fourier transform (Fig. 4B). The model-independent conformational parameters Rg and Dmax obtained from these analyses are summarized in Table 1. For PCNA and the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex, scattering profiles (supplemental Fig. 2A) and Rg and Dmax parameters were calculated from available crystal structures, with the resulting values in good agreement with those determined by SAXS. As observed previously for Sulfolobus solfataricus PCNA (37), the P(r) profile for human PCNA is bimodal. A second noteworthy feature of the P(r) functions shown in Fig. 4B is that in contrast to that for MutSαΔ341, the P(r) distributions for MutSα and MutSαΔ12 are highly skewed toward larger r values. This suggests that the conformations of these two heterodimers are significantly more elongated than that of MutSαΔ341, which contains 1953 of the 2294 residues present in native MutSα.

FIGURE 4.

SAXS of MutSα, MutSαΔ341, and PCNA. A, scattering intensities versus Q are shown for MutSα (blue line), MutSαΔ12 (green line), MutSαΔ341 (red line), MutSαΔ341 complexed to a 15-bp G-T heteroduplex (brown line), and PCNA (black line). Linear portions of Guinier plots (inset) determined from scattering profiles were used to determine Rg values (shown in Table 1). B, normalized pairwise interatomic distances (P(r)) were derived from solution scattering intensities (see “Experimental Procedures”). The color scheme is as described for A. C, ab initio shape reconstructions of MutSαΔ341, MutSαΔ341 bound to a 15-bp G-T heteroduplex, and PCNA were obtained from SAXS data (see “Experimental Procedures”). SUPCOMB (28) was used to superimpose and align the crystal structure of PCNA (39) or the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex (14) on SAXS envelopes.

We also analyzed x-ray scattering by equimolar mixtures of MutSα and the PCNA trimer (Fig. 5A). The Rg and I(0) values determined for 1:1 mixtures of the two proteins are significantly greater than those for either of the individual components (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. 2B). The latter parameter is a linear function of molecular mass (38), and as shown in supplemental Fig. 2B, the I(0) value observed for the equimolar mixture is consistent with the molecular mass of 344 kDa expected for the 1:1 MutSα·PCNA trimer complex that we observed using other methods (Figs. 1 and 3). Because PCNA is potentially trivalent with respect to its partner interactions (35), SAXS data were also collected at variable [PCNA]/[MutSα] ratios. As shown in Fig. 5B, corresponding I(0) values increased until the ratio achieved a value of 1 and then decreased. This is the behavior expected for an interaction model that assumes stoichiometric formation of a 1:1 complex between the two proteins. By contrast, experimental I(0) values differed markedly from those predicted by models that invoke multivalent interaction with the PCNA trimer (Fig. 5B). Furthermore, no increase in I(0) was observed upon PCNA titration of MutSαΔ12 or MutSαΔ341, confirming the severe nature of the interaction defect conferred by deletion of the MSH6 PCNA interaction motif.

FIGURE 5.

Stoichiometry and ab initio analysis of the MutSα·PCNA complex. A, P(r) plots for MutSα (solid blue line) and an equimolar mixture of MutSα and PCNA (red) were determined from composite scattering profiles (inset) as described in the legend to Fig. 4. The P(r) plot for MutSαΔ341 (dotted blue line) and the PCNA scattering profile (inset, black line) are shown for comparison. B, forward scattering intensities (I(0)) (intensity at θ = 0°) of mixtures of MutSα and PCNA were obtained (see “Experimental Procedures”) as a function of the PCNA/MutSα molar ratio for native MutSα (○), MutSαΔ12 (▴), and MutSαΔ341 (▪). Because I(0) is a linear function of molecular mass (supplemental Fig. 2) (38), we calculated the expected volume average dependence of this parameter (23) for models that assume different modes of MutSα-PCNA interaction: (i) stoichiometric formation of a 1:1 complex between MutSα and the PCNA trimer (red circles); (ii) interaction stoichiometry of two molecules of MutSα/PCNA trimer (blue circles); and (iii) stoichiometry of two molecules of MutSα/PCNA trimer when MutSα is in excess, but disproportionating to a 1:1 complex when PCNA is in excess (green line). The predicted dependence of I(0) for a PCNA mixture with MutSαΔ12 (red triangles) or MutSαΔ341 (red squares) assuming no interaction is also shown. C, ab initio shape reconstructions are shown. Low resolution models for MutSα and the 1:1 MutSα·PCNA complex were obtained from experimental scattering data as described under “Experimental Procedures.” The molecular envelope for MutSα (gray spheres) represents the average of 10 independent shape reconstructions, and the crystal structure of MutSαΔ341 was positioned manually by PyMOL for comparison of dimensions. For the MutSα·PCNA complex, a single representative shape reconstruction is shown (gray spheres), with the crystal structures of MutSαΔ341 and PCNA manually placed to indicate their possible locations within the complex. Although the solution scattering profile of the MutSα·PCNA complex is consistent with an extended conformation, the low resolution of the reconstruction does not permit assignment of the relative orientation of the two proteins about the long axis of the molecular envelope. (Additional independent shape reconstructions for MutSα·PCNA are shown in supplemental Fig. 3.)

The gel filtration studies described above demonstrated an increase in Stokes radius from 67 Å for MutSα to 80 Å upon formation of the MutSα·PCNA complex (Fig. 1B), and a similar increase was observed upon PCNA binding to the complex of MutSα with a 21-bp G-T heteroduplex (from ∼69 to 83 Å) (Fig. 3B). Corresponding increases were also observed in the similar but non-identical parameter Rg determined from SAXS measurements. As summarized in Table 1, Stokes radii and Rg values determined by these two different methods correlate well.

SAXS Shape Reconstructions for MutSα and the MutSα·PCNA Complex—We employed the SAXS data described above for construction of low resolution models of the repair proteins considered here (27). The application of SAXS in these cases is facilitated by the availability of crystal structures for the human MutSαΔ341·DNA complex (14) and PCNA (39), which provide useful controls for assessing validity of the models (40). Fig. 4C summarizes shape reconstructions for MutSαΔ341, the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex, and PCNA. Surface envelopes for the two former proteins are shown superimposed on the crystal structure of the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex, whereas the latter is superimposed on the PCNA structure. Agreement is good in each case. As shown, shape reconstructions for MutSαΔ341 and the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex are similar, and as summarized in Table 1, binding of a 15-bp G-T heteroduplex to MutSαΔ341 is associated with only a 2-3-Å decrease in Rg.

As expected, the Dmax value of 202 Å for full-length MutSα determined by SAXS is substantially greater than the value of 130 Å calculated from the crystal structure of the human MutSαΔ341·DNA complex (Table 1) (14). A low resolution model determined from SAXS data for the full-length protein is shown in Fig. 5C (left panel). Comparison with the ab initio SAXS structure of MutSαΔ341 (Fig. 4C) reveals a common structural feature, the dimensions of which readily accommodate the MutSαΔ341 crystal structure. In addition, the MutSα SAXS envelope displays additional mass that presumably corresponds to the MSH6 N-terminal 341 residues that are absent in MutSαΔ341.

Two limiting conformations of the MutSα·PCNA complex can be imagined: a stacked complex wherein the DNA-binding channels of the two proteins are aligned and an extended conformation in which the two proteins associate in an end-to-end manner with their DNA-binding channels orthogonal to the long axis of the complex. Although MutSαΔ341 is unable to bind PCNA, we utilized the crystal structures of PCNA and the MutSαΔ341·DNA complex to illustrate these two models and have their expected P(r) functions. As shown in supplemental Fig. 2C, the P(r) function for the stacked complex displays pseudo-symmetry, and the function maximum is shifted to a higher r value than the P(r) function calculated from MutSαΔ341 crystal structure. By contrast, the P(r) function predicted for the end-to-end complex is bimodal, but the P(r) maximum is achieved at an r value only slightly greater than that for MutSαΔ341. P(r) functions were calculated for two different isomers of the end-to-end complex that differ with respect to a 90° rotation of the two proteins about the long axis of the complex; as shown in supplemental Fig. 2C, the calculated P(r) functions for the two isomers were indistinguishable. Experimental x-ray scattering results obtained with the 1:1 complex of PCNA with native MutSα are similar to those predicted for the end-to-end models. The P(r) function determined from MutSα·PCNA SAXS data displays a distinct shoulder at r values of ∼100-200 Å, but achieves its maximum at a value of r that is essentially identical to that for native MutSα and only slightly greater than that for MutSαΔ341. Low resolution shape reconstructions are also indicative of an extended conformation. Fig. 5C (left panel) shows the results of a single shape reconstruction for the MutSα·PCNA complex, with the results of seven other independent reconstructions shown in supplemental Fig. 3. Unlike the other low resolution conformations described above, this set of reconstructions was not averaged. Although all reconstructions were consistent with an extended conformation, placement of MutSαΔ341 and PCNA crystal structures within the set of envelopes was possible only if the rotational orientation of the two proteins about the long axis of the complex was allowed to vary. This is consistent with model calculations described above indicating that P(r) is insensitive to the rotational orientation of the two proteins in the extended complex.

Functional Significance of the MutSα-PCNA Interaction in Mismatch Repair—To assess the functional significance of the MutSα-PCNA interaction, we compared the activities of MutSα and MutSαΔ12 in mismatch repair and several partial reactions implicated in overall repair. As shown in Fig. 6A, the two heterodimers do not differ significantly in their ability to restore mismatch-provoked excision to nuclear extracts prepared from MSH6-/- HCT-15 tumor cells, and similar results were obtained with extracts prepared from MSH2-/- RL95-2 cells (data not shown). MutSα and MutSαΔ12 were also compared in several purified systems. The two proteins are similarly active in their ability to support MutSα-, RFC-, and PCNA-dependent activation of the MutLα endonuclease (32) and are comparable in their ability to support 5′-directed mismatch-provoked excision in a purified system composed of MutSα, MutLα, Exo1, and replication protein A (31) or 3′-directed excision in the presence of MutSα, MutLα, Exo1, RFC, PCNA, and replication protein A (9) (Fig. 6B). Similar results were obtained with MutSαΔ341 in reconstituted excision reactions (data not shown). However, the MutSαΔ12 mutation confers a partial but significant and reproducible defect in the overall mismatch repair reaction. Although MutSα and MutSαΔ12 are similarly active in restoration of 3′-directed mismatch repair to nuclear extracts of MSH6-/- HCT-15 cells, MutSαΔ12 is only about half as active as the wild-type protein in its ability to restore 5′-directed repair (Fig. 6C). Essentially identical results were obtained with extracts derived from MSH2-/- RL95-2 cells (data not shown), and we have shown previously that MutSαΔ341 displays a similar partial defect that is restricted to the 5′-directed mismatch repair reaction (14). Thus, although dispensable for 3′- or 5′-directed excision steps, the N-terminal PCNA-binding motif of MSH6 plays a significant role in 5′-directed mismatch repair when the overall reaction is scored.

FIGURE 6.

The MSH6 PCNA-binding motif is not required for mismatch-provoked excision and MutLα endonuclease activation, but is necessary for optimum 5′-directed mismatch repair. A, excision on 3′ (▿, ▵, ▾, and ▴) or 5′ (○, □, •, and ▪) heteroduplex (open symbols) or homoduplex (closed symbols) DNA (see “Experimental Procedures”) was scored in the absence of exogenous dNTPs in nuclear extracts of MSH6-/- HCT-15 cells supplemented with 780 fmol of MutSα (○, ▿, •, and ▾) or MutSαΔ12 (□, ▵, ▪, and ▴). Data shown are averages of three experiments, with S.D. values ranging from 0.01 to 0.2 fmol. Excision in the absence of exogenous MutSα was not detectable. B, MutSα and MutSαΔ12 (780 fmol) were scored for their ability to support MutLα endonuclease activation (32) and 3′-directed (9) or 5′-directed (31) mismatch-provoked excision in purified systems (see “Experimental Procedures”). C, repair of 5′ (• and ▪) and 3′ (○ and □) G-T heteroduplexes in MSH6-deficient HCT-15 extracts was scored as a function of exogenous MutSα (• and ○) or MutSαΔ12 (▪ and □). Reactions were as described for A but contained added dNTPs. Data are the average of three experiments with S.D. values indicated by error bars.

DISCUSSION

PCNA, the trimeric replication sliding clamp, is believed to coordinate various DNA metabolic processes via its interactions with components of replication, repair, and recombination systems. In human mismatch repair, PCNA has been implicated at two stages in the reaction: it is required for activation of the MutLα endonuclease (32), but is also necessary for the repair synthesis step of the reaction (3), functions that presumably depend on its known ability to interact with multiple mismatch repair factors, including MutSα, MutLα, Exo1, and DNA polymerase δ. However, the conformational nature of these complexes and the contributions of individual interactions to various steps of the reaction remain largely uncertain. We have addressed these issues for the human MutSα·PCNA complex. Previous studies with yeast proteins led to the suggestion that MutSα and PCNA associate to form an active mispair recognition complex, which has a higher affinity for heteroduplex DNA, and that PCNA is released upon mismatch binding (7, 12). By contrast, we observed that human MutSα binds heteroduplex DNA with comparable affinity and specificity in the absence or presence of PCNA. Consistent with these observations, mismatch-bound MutSα has an affinity for PCNA that is very similar to that of free MutSα.

A key function of PCNA in mismatch repair is its role in activation of the latent endonuclease of MutLα (32). This endonuclease, which also depends on MutSα and RFC for its activation, introduces additional breaks into the discontinuous strand of a nicked heteroduplex that serve as entry sites for Exo1. Despite the severe nature of the PCNA interaction defect conferred by MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 mutations, MutSαΔ12 supports MutLα activation, and both mutants are essentially fully active in their abilities to support mismatch-provoked excision in a reconstituted system. Furthermore, MutSαΔ12 supports normal levels of mismatch-provoked excision upon supplementation of MutSα-deficient nuclear extracts. Thus, the interaction between MutSα and PCNA is not critical for early steps of mismatch repair, suggesting that PCNA interaction with other activities such as MutLα and/or Exo1 accounts for involvement of the replication clamp in early steps of the reaction. Indeed, a recent study has suggested an important effector role for PCNA in the function of the MutLα endonuclease (41).

Although removal of the PCNA interaction motif from MutSα has little if any effect on MutLα endonuclease activation or mismatch-provoked excision steps of the reaction, MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 both display a limited but reproducible defect in 5′-but not 3′-directed mismatch repair. Because we have been unable to detect a corresponding defect in 5′-directed mismatch-provoked excision (scored under conditions of DNA synthesis block), we infer that this partial 5′-repair defect is manifested at the repair synthesis step. This defect, which reduces the rate of the reaction by ∼50%, may indicate MutSα participation in the DNA synthesis step of 5′-directed repair. It is also noteworthy that the nature of this defect is consistent with the significant but limited mutability increase that has been observed upon alanine substitution of conserved residues within the PCNA interaction motif of MSH6 (6, 7). In contrast to our results with the MutSαΔ12 and MutSαΔ341 variants, removal of the N-terminal 77 residues of human MSH6 has been shown to substantially reduce the MutSα mismatch repair activity in human cell extracts (8). It is possible that the MSH6Δ77 mutation interferes with the interaction of MutSα with mismatch repair factors other than PCNA or compromises the function of the protein in a manner unrelated to its inability to interact with PCNA.

The nature of PCNA lends itself to models wherein a single homotrimeric ring can interact with up to three molecules of a binding partner. In fact, human PCNA is capable of binding three molecules of p21 or Fen1 (35, 42). However, the several different experimental approaches used here demonstrate that the interaction stoichiometry of human MutSα with the PCNA trimer is restricted to 1:1, even under conditions of large MutSα excess. Given the trivalent nature of PCNA, the 1:1 stoichiometry limitation may be due to steric factors, although it is important to note that whereas the MutSα·PCNA complex cannot bind a second molecule of MutSα, the PCNA component of the complex might be capable of simultaneous interaction with another repair or replication activity.

Our low resolution SAXS models reveal that MutSα and PCNA associate in an end-to-end fashion in solution to form an elongated complex in which the DNA-binding channels of the two proteins are not aligned, but rather are orthogonal to the long axis of the complex. Although contrary to expectation, a similar extended conformation has been demonstrated for the S. solfataricus ligase·PCNA complex in solution (37). Because MSH6 residues 1-341 are not present in MutSαΔ341, for which the crystal structure has been determined (14), the structure of the MSH6 N-terminal domain has been uncertain. However, recent NMR studies have demonstrated that residues 89-194 of human MSH6 adopt a globular conformation (Protein Data Bank code 2GFU).3 Our SAXS reconstructions with native MutSα and the MutSα·PCNA complex are also consistent with the idea that the N-terminal domain of MSH6 has globular features and interacts with PCNA to form a complex with significantly defined conformational character. By contrast, SAXS studies of an N-terminal fragment of yeast Msh6 (residues 1-304) have indicated that this polypeptide exists in an extended unstructured conformation, leading Shell et al. (43) to conclude that yeast MutSα interacts with PCNA by virtue of a highly extended unstructured tether. Although the Shell et al. study included SAXS data collection with full-length yeast MutSα in the absence or presence of PCNA, surface reconstructions for these polypeptide complexes were not described. It is also noteworthy that although the yeast Msh6 N-terminal segment supports PCNA interaction with 3:1 stoichiometry (43), native yeast MutSα probably interacts with the yeast PCNA trimer with 1:1 stoichiometry (7). The significance of these apparent differences in the nature of the human and yeast MutSα·PCNA complexes thus remain to be resolved.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Joshua Warren for many helpful discussions and Sophie Zinn-Justin for sharing unpublished results.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 GM45190 and P01 CA92584. The costs of publication of this article were defrayed in part by the payment of page charges. This article must therefore be hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 U.S.C. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. 1-4 and additional references.

This article was selected as a Paper of the Week.

Footnotes

The abbreviations used are: PCNA, proliferating cell nuclear antigen; RFC, replication factor C; SPRS, surface plasmon resonance spectroscopy; NTA, nitrilotriacetic acid; SAXS, small angle x-ray scattering.

S. Zinn-Justin, personal communication.

References

- 1.Iyer, R. R., Pluciennik, A., Burdett, V., and Modrich, P. L. (2006) Chem. Rev. 106302 -323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiricny, J. (2006) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7335 -346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gu, L., Hong, Y., McCulloch, S., Watanabe, H., and Li, G. M. (1998) Nucleic Acids Res. 261173 -1178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Johnson, A., and O'Donnell, M. (2005) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 74283 -315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Umar, A., Buermeyer, A. B., Simon, J. A., Thomas, D. C., Clark, A. B., Liskay, R. M., and Kunkel, T. A. (1996) Cell 8765 -73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clark, A. B., Valle, F., Drotschmann, K., Gary, R. K., and Kunkel, T. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 27536498 -36501 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Flores-Rozas, H., Clark, D., and Kolodner, R. D. (2000) Nat. Genet. 26 375-378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kleczkowska, H. E., Marra, G., Lettieri, T., and Jiricny, J. (2001) Genes Dev. 15 724-736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dzantiev, L., Constantin, N., Genschel, J., Iyer, R. R., Burgers, P. M., and Modrich, P. (2004) Mol. Cell 15 31-41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nielsen, F. C., Jager, A. C., Lutzen, A., Bundgaard, J. R., and Rasmussen, L. J. (2004) Oncogene 231457 -1468 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee, S. D., and Alani, E. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 355175 -184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau, P. J., and Kolodner, R. D. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 27814 -17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blackwell, L. J., Wang, S., and Modrich, P. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 27633233 -33240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Warren, J. J., Pohlhaus, T. J., Changela, A., Iyer, R. R., Modrich, P. L., and Beese, L. S. (2007) Mol. Cell 26 579-592 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Drummond, J. T., Li, G. M., Longley, M. J., and Modrich, P. (1995) Science 2681909 -1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Genschel, J., Bazemore, L. R., and Modrich, P. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 27713302 -13311 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gulbis, J. M., Kelman, Z., Hurwitz, J., O'Donnell, M., and Kuriyan, J. (1996) Cell 87 297-306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kelman, Z., Yao, N., and O'Donnell, M. (1995) Gene (Amst.) 166177 -178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dynlacht, B. D., Ngwu, C., Winston, J., Swindell, E. C., Elledge, S. J., Harlow, E., and Harper, J. W. (1997) Methods Enzymol. 283230 -244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gill, S. C., and von Hippel, P. H. (1989) Anal. Biochem. 182319 -326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wong, I., and Lohman, T. M. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 905428 -5432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Guinier, A., and Fournet, G. (1955) Small-angle Scattering of X-rays, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York

- 23.Konarev, P. V., Volkov, V. V., Sokolova, A. V., Koch, M. H., and Svergun, D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 361277 -1282 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Svergun, D. I. (1992) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 25495 -503 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nagar, B., Hantschel, O., Seeliger, M., Davies, J. M., Weis, W. I., Superti-Furga, G., and Kuriyan, J. (2006) Mol. Cell 21787 -798 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Svergun, D. I. (1999) Biophys. J. 762879 -2886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Svergun, D. I., Petoukhov, M. V., and Koch, M. H. (2001) Biophys. J. 802946 -2953 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kozin, M. B., and Svergun, D. I. (2001) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 3433 -41 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Volkov, V. V., and Svergun, D. I. (2003) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 36860 -864 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kat, A., Thilly, W. G., Fang, W. H., Longley, M. J., Li, G. M., and Modrich, P. (1993) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 906424 -6428 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Genschel, J., and Modrich, P. (2003) Mol. Cell 121077 -1086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kadyrov, F. A., Dzantiev, L., Constantin, N., and Modrich, P. (2006) Cell 126297 -308 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhang, P., Zhang, S. J., Zhang, Z., Woessner, J. F., Jr., and Lee, M. Y. (1995) Biochemistry 3410703 -10712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ackers, G. K. (1973) Methods Enzymol. 27441 -455 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Flores-Rozas, H., Kelman, Z., Dean, F. B., Pan, Z. Q., Harper, J. W., Elledge, S. J., O'Donnell, M., and Hurwitz, J. (1994) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 918655 -8659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Myszka, D. G. (1999) J. Mol. Recognit. 12279 -284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pascal, J. M., Tsodikov, O. V., Hura, G. L., Song, W., Cotner, E. A., Classen, S., Tomkinson, A. E., Tainer, J. A., and Ellenberger, T. (2006) Mol. Cell 24 279-291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kratky, O. (1963) Prog. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 13105 -173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kontopidis, G., Wu, S. Y., Zheleva, D. I., Taylor, P., McInnes, C., Lane, D. P., Fischer, P. M., and Walkinshaw, M. D. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1021871 -1876 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nagar, B., and Kuriyan, J. (2005) Structure (Camb.) 13169 -170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kadyrov, F. A., Holmes, S. F., Arana, M. E., Lukianova, O. A., O'Donnell, M., Kunkel, T. A., and Modrich, P. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 28237181 -37190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen, U., Chen, S., Saha, P., and Dutta, A. (1996) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 9311597 -11602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shell, S. S., Putnam, C. D., and Kolodner, R. D. (2007) Mol. Cell 26 565-578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Svergun, D., Barberato, C., and Koch, M. H. (1995) J. Appl. Crystallogr. 28 768-773 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.