Abstract

Glutamate is the main excitatory neurotransmitter in both the peripheral and central auditory systems. Changes of glutamate and glutamate-related genes with age may be an important factor in the pathogenesis of age-related hearing loss - presbycusis. In this study, changes in glutamate-related mRNA gene expression in the CBA mouse inferior colliculus with age and hearing loss were examined and correlations were sought between these changes and functional hearing measures, such as the auditory brainstem response (ABR) and distortion product otoacoustic emissions (DPOAEs). Gene expression of 68 glutamate-related genes was investigated using both genechip microarray and real-time PCR (qPCR) molecular techniques for four different age/hearing loss CBA mouse subject groups. Two genes showed consistent differences between groups for both the genechip and qPCR. Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase enzyme (Pycs) showed down-regulation with age and a high-affinity glutamate transporter (Slc1a3) showed up-regulation with age and hearing loss. Since Pycs plays a role in converting glutamate to proline, its deficiency in old age may lead to both glutamate increases and proline deficiencies in the auditory midbrain, playing a role in the subsequent inducement of glutamate toxicity and loss of proline neuroprotective effects. The up-regulation of Slc1a3 gene expression may reflect a cellular compensatory mechanism to protect against age-related glutamate or calcium excitoxicity.

Introduction

Glutamate is a major excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Previous data support the role of glutamate as the main excitatory neurotransmitter in the inferior colliculus (Faingold, 2002; Caicedo and Eybalin, 1999; Feliciano and Potashner, 1995; Gaza and Ribak, 1997; Goldsmith et al., 1995; Helfert et al., 1999; Liao et al., 2000; Moore et al., 1998; Parks, 2000; Saint Marie, 1996; Suneja et al., 1995, 2000). In addition, glutamine and glutamate have numerous functions in different organs working as precursors for neurotransmitters, related proteins, nucleotides, nucleic acids and glutathione synthesis. The amino acid L-glutamine is vitally important for cell survival while its immediate metabolic product, L-glutamate is at the crossroads of the metabolic pathways of proline, ornithine, succinate, aspartate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Newsholme et al., 2003).

In addition, glutamate plays a major role in neuronal plasticity and neurotoxicity, and has been implicated in a number of pathological states; one of these states may be age-related hearing loss - presbycusis. Many factors play a role in glutamate neurotoxicity. The glutamine/glutamate pathway in the central nervous system normally works to prevent glutamate toxicity. As glutamate is transported from the synaptic cleft into nearby astrocytes by glial high-affinity glutamate transporters, such as Slc1a2 (GLT-1) or Slc1a3 (GluT-1/GLAST), it is converted to glutamine. Glutamine crosses the cytoplasmic membranes to the neurons where it is converted back to glutamate by glutaminase enzymes. Glutamate is stored in presynaptic vesicles by vesicular transporters (as Slc17a6). Glutamate metabolism, vesicular transport, synaptic re-uptake and its effect on post-synaptic glutamate receptors can all play roles in glutamate toxicity. Increased glutamate synthesis, decreased conversion of glutamate to its metabolic products, increased vesicular transport or decreased synaptic re-uptake are the main factors impacting on the severity of glutamate neurotoxicity.

Proline is an essential amino acid that is synthetized from ornithine and glutamate. In high concentrations (>100um), proline has been shown to activate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, alpha amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid (AMPA) receptors, and strychnine-sensitive glycine receptors (Cohen and Nadler, 1997; Takemoto, 2005).

In the present investigation, glutamate-related gene expression was investigated in the inferior colliculus of different age groups of CBA mice. In addition, relations between gene expression changes with age and hearing function declines with age were examined for these subject groups.

Materials and Methods

The subject groups, gene expression methods and hearing tests employed here are similar to those of Tadros et al. (2006-In press). All animal procedures were approved by the University of Rochester (Rochester, NY) Animal Resource Review Committee.

Animal Model

CBA/CaJ mice were bred in-house and housed according to institutional protocol, with original breeding pairs obtained from Jackson Laboratories. All animals had similar environmental and non-ototoxic history. The CBA mouse is a model organism for human presbycusis because it loses its hearing progressively over its lifespan. The young adult group was used as the baseline group for gene expression data analyses (e.g., calculation of fold changes). Functional hearing measurements were obtained prior to sacrifice similar to our previous investigations (Jacobson et al., 2003; Guimaraes et al., 2004; Varghese et al., 2005).

Functional Hearing Assessment

1- Distortion Product Otoacoustic Emissions (DPOAEs)

Ipsilateral acoustic stimulation and simultaneous measurement of distortion-product otoacoustic emissions were accomplished with the TDT BioSig III system. Stimuli were digitally synthesized at 200 kHz using SigGen software applications with the ratio of frequency 2 (F2) to frequency 1 (F1) constant at 1.25; L1 was equal to 65 dB sound pressure level (SPL) and L2 was equal to 50 dB SPL as calibrated in a 0.1-mL coupler simulating the mouse ear canal. After synthesis, F1, F2, and the wideband noise were each passed through an RP2.1 D/A converter to PA5 programmable attenuators. Following attenuation, the signals went to ED1 speaker drivers which fed into the EC1 electrostatic loudspeakers coupled to the ear canal through short, flexible tubes with rigid plastic tapering tips. For DPOAE measurements, resultant ear canal sound pressure was recorded with an ER10B+ low-noise microphone and probe (Etymotic) housed in the same coupler as the F1 and F2 speakers. The output of the ER10B+ amplifier was put into an MA3 microphone amplifier, whose output went to an RP2.1 A/D converter for sampling at 200 kHz. A fast Fourier transform (FFT) was performed with TDT BioSig software on the resultant waveform. The magnitude of F1, F2, 2f1–f2 distortion product, and the noise floor of the frequency bins surrounding the 2f1–f2 components were measured from the FFT. The procedure was repeated for geometric mean frequencies ranging from 5.6 to 44.8 kHz (eight frequencies per octave) to adequately assess the neuroethologically functional range of mouse hearing.

Before data acquisition, individual mice were microscopically examined for evidence of external ear canal and middle ear obstruction. Mice with clearly visualized, healthy tympanic membranes were included. Mice were anesthetized with a mixture of ketamine and xylazine (120 and 10 mg/kg body weight, respectively) by intraperitoneal injection before all experimental sessions. All recording sessions were completed in a soundproof acoustic chamber (lined with Sonex) with body temperature maintained with a heating pad. Before recording, the operating microscope (Zeiss) was used to place the stimulus probe and microphone in the test ear close to the tympanic membrane. The recording session duration was limited by depth of anesthesia, and lasted approximately 1 hour per animal.

2- Auditory Brainstem Responses (ABRs)

Auditory Brainstem Responses were measured in response to tone pips of 3, 6, 12, 24, 32, and 48 kHz presented at a rate of 11 bursts/sec. Auditory brainstem responses were recorded with subcutaneous platinum needle electrodes placed at the vertex (noninverting input), right-side mastoid prominence (inverted input), and tail (indifferent site). Electroencephalographic (EEG) activity was differentially amplified (50 or 100 X) (Grass Model P511 EEG amplifier), then put into an analogue-to-digital converter (AD1, Tucker-Davis [TDT]) and digitized at 50 kHz. Each averaged response was based on 300–500 stimulus repetitions recorded over 10-millisec epochs. Contamination by muscle and cardiac activities was prevented by rejecting data epochs in which the single-trace electroencephalogram contained peak-to-peak amplitudes exceeding 50 μV. During this procedure, 5.0 mg/10.0 gm body weight general anesthetic, Avertin (Tribromoethanol, deliverd IP), was used to immobilize the mice. Normal body temperature was maintained at 38°C with a Servo heating pad. The ABR was recorded in a small sound-attenuating chamber.

Sample Isolation

Upon completion of the physiological recording sessions, the mice were sacrificed by decapitation. The brains were immediately dissected using a Zeiss stereomicroscope and placed in ice-cold saline. The IC was dissected from each brain. Thirty-nine brain (inferior colliculi) samples were collected. All samples were placed in cold Trizol (Invitrogen, CA) and stored at −80°C for gene microarray and real time PCR processing.

Microarray gene expression processing

A- Gene Chip

One Affymetrix M430A high-density oligonucleotide array set (A) was used for each IC sample from one animal. No pooling of IC tissue from different mice was done. Each array contains 22,600 probe sets analyzing the expression of over 14,000 mouse genes. Eleven pairs of 25-mer oligonucleotides that span the coding region of the genes represent each gene. Each probe pair consists of a perfect match sequence that is complementary to the mRNA target and a mismatch sequence that has a single base pair mutation in a region critical for target hybridization; this sequence serves as a control for non-specific hybridization. Sequences used in the design of the array were selected from GenBank, dbEST, and RefSeq.

B- Samples Preparation

1- RNA Extraction

Each sample was homogenized in 1 mL of Trizol reagent per 50–100 mg of tissue using a polytron power homogenizer. The total RNA was isolated from the tissue homogenates of each sample using a modified Trizol protocol (Gibco BRL). Each sample was centrifuged at 12,000 x g for 10 min at 4°C and the clear supernatant was transferred to a new tube and incubated for 5 min at 15–30°C to permit the complete dissociation of nucleoprotein complexes. 0.2 mL of chloroform per each mL of trizol reagent was added and the tube was shaken vigorously by hand for 15 sec, then incubated at 15–30°C for 2 min and centrifuged at 12,000g for 15 min at 4°C. The aqueous phase was transferred to a new tube, 0.5 mL of isopropyl alcohol per 1 mL Trizol reagent, then incubated at 15–30°C for 10 min and centrifuged at 12,000g for 10 min at 4°C. The supernatant was separated and the RNA pellet was washed once with 1 mL 75% ethanol (EtOH) for each 1 mL trizol reagent. The sample was mixed by vortex and then centrifuged at 7500g for 5 min at 4°C. The new RNA pellet was air-dried, dissolved in 10–20 uL of RNase-free water and incubated at 42°C for 5 min. The RNA quality was assessed by Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100, and absorbance measurements at A260/A280 using the nanodrop.

2- cDNA Synthesis

For gene array analysis, cDNA synthesis was performed with 20 μg of total RNA using the Superscript Choice cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen). For qPCR, nuGen cDNA reagents kit was used to generate a high fidelity cDNA, which was modified at the 3’ end to contain an initiation site for T7 RNA polymerase. Detailed protocol is found in www.nugeninc.com.

3-In-vitro Transcription (IVT) and Fragmentation

Clean up of double-stranded cDNA was done according to the Affymetrix GeneChip Expression analysis protocol. Synthesis of Biotin-labeled cRNA was performed by adding 1μg of cDNA to 10X IVT labeling buffer, IVT labeling NTP mix, IVT labeling enzyme mix and RNase-free water, then, incubated at 37°C for 16 hours. The Biotin-labeled cRNA was cleaned up according to the Affymertix GeneChip expression analysis protocol and a 20 μg of full-length cRNA from each sample was fragmented by adding 5X fragmentation buffer and RNase-free water, followed by incubation at 94°C for 35 min. The standard fragmentation procedure produces a distribution of RNA fragment sizes from approximately 35 to 200 bases. After the fragmentation, cDNA, full-length cRNA and fragmented cRNA were analyzed by electrophoresis using the Agilent Bioanalyzer 2100 to assess the appropriate size distribution prior to microarray hybridization.

C- Target Hybridization, Washing, Staining and Scanning

GeneChip M430A probe arrays (Affymetrix) were hybridized, washed and stained according to the manufacturer’s instructions in a fluidics station. The arrays were scanned using a Hewlett Packard confocal laser scanner and visualized using GeneChip 5.1 software. Three data files were created, namely image data (.dat), cell intensity data (.cel) and expression probe analysis data (.chp) files. Detailed protocols for sample preparation and target labeling assays for expression analysis can be found at http://www.Affymetrix.com.

Real-time PCR (qPCR)

The primer/probe used in quantification of gene expression was acquired from TaqMan® GeneExpression Assays-on-Demand products (AOD) from Applied Biosystems, Inc., CA. The primer/probe consisted of a 20X mix of unlabeled PCR primers and TaqMan MGB probe (FAM dye-labeled). The Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system was used to perform the real-time experiments using a 20 uL volume reaction in a 96-well plate. Each well contains 9 uL template (cDNA) and/or RNase-free water (control) with total cDNA concentration of 88 ng, 1 uL 20X assays-on-demand GeneExpression assay mix (primer/probe) for the studied gene, 10 uL TaqMan 2X universal PCR master mix. A parallel PCR reaction was performed with glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH)-specific primer/probe, as an endogenous control. The reactions were performed in triplicates in order to control technical replicates.

The reactions’ thermal cycle conditions were adjusted as 10 min initial setup at 95°C, followed by 50 cycles, each of which consisted of 15 sec denaturing at 95°C and 1 min annealing/extend at 60°C. The results of each plate were analyzed using ABI PRISM software to calculate the CT value of each well and compare these values in studied gene wells with control and endogenous control wells. In this investigation, real-time PCR was done to confirm and quantify the five significant glutamate-related genes in IC of different age groups of CBA mice as revealed by the microarrays. Detailed information about protocols is found in www.appliedbiosystems.com.

Statistical Analyses

1- GeneChip Expression Analysis

After assessing chip quality, the Affymetrix GeneChip Operating Software (GCOS) automatically generates the (.cel) image file from the (.dat) data file. The signal log ratio of each sample determined the difference in expression of the studied gene in that sample from the mean expression of that gene in all samples from the young adult mice. A signal log ratio of 1.0 indicates an increase of the transcript level by 2 fold and −1.0 indicates a decrease by 2 fold. A signal log ratio of zero indicates no change.

For the sixty-eight glutamate related genechip probes, one-way Analysis of Variance (ANOVA) was used to compare between the signal log ratio values of the different subject groups. In addition, fold changes of all samples were calculated from signal log ratios using the following equations:

This was followed by statistical analysis of signal log ratios of the sixty-eight glutamate related genes using Kruskal-Wallis test to compare between groups.

2- Real Time PCR Analysis

The mRNA sources for qPCR are from the same mice as utilized in the genechip experiment. The threshold cycle (CT ) values, defined as the number of PCR cycles taken to reach the greatest amplification level, were measured to detect the threshold of each of the five significant and GAPDH genes in all IC samples (Giulietti et al., 2001; Baik et al., 2005). Each sample was measured in triplicate and normalized to the reference GAPDH gene expression. The CT value of each well was determined and the average of the three wells of each sample was calculated. For samples that showed no expression of the test gene, the value of minimum expression was used for statistical analysis.

Delta CT ( ΔCT ) for test gene of each sample was calculated using the equation:

Delta delta CT ( ΔΔCT) was calculated using the following equation:

The fold change in the test gene expression was finally calculated from the formula:

A statistical evaluation of real time PCR results was performed using one-way ANOVA to compare between ΔCT for test gene expression in young age, middle age, old age mild presbycusis, and old age severe presbycusis groups. For the two significantly different genes on the genechip and qPCR, linear regression analyses were employed to find correlations between the signal log ratio values or fold change and the functional hearing measurements. These measurements were the distortion product otoacoustic emission (DPOAE) amplitudes at low frequencies (5.6 kHz to 14.5 kHz), mid frequencies (15.8 kHz to 29.0 kHz) and high frequencies (31.6 kHz to 44.8 kHz), in addition to auditory brainstem response thresholds (ABR) at 3, 6, 12, 24, 32 and 48 kHz. The GraphPad Prism 4 software was used to perform the one-way ANOVA and the linear regression statistics.

Results

Subject Groups: Age and Hearing Functionality

The sample set segregated into 4 groups based upon age, and DPOAE and ABR hearing measurements, as given in Table 1: young adult control with good hearing (N=7, 4 males, 3 females, age=3.5 +/− 0.4 months), middle-aged with good hearing (N=17, 8 males, 9 females, age=12.3 +/- 1.3 months), old with mild presbycusis (N=9, 4 males, 5 females, age=27.7 +/− 3.4 months) and old with severe presbycusis (N=6, 2 males, 4 females, age=30.6 +/− 1.9 months).

Table 1.

Means and standard deviations of DPOAE amplitudes and ABR thresholds for the four CBA mouse subject groups

| Young NH | Middle Age NH | Old Mild HL | Old Severe HL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low Frequency DPOAE (5–14 kHz) (dB SPL), SD | 17.40, 5.76 | 18.76, 4.35 | 7.69, 6.68 | −13.61, 6.21 |

| Mid Frequency DPOAE (15–29 kHz) (dB SPL), SD | 17.92, 5.1 | 18.08, 4.37 | 4.12, 6.96 | −19.43, 3.25 |

| High Frequency DPOAE (31–s45 kHz) (dB SPL), SD | 11.26, 9.11 | 8.52, 4.41 | −1.47, 6.51 | −21.95, 1.48 |

| 3 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 53.33, 11.99 | 64.41, 7.68 | 78.89, 10.83 | 85.00, 26.46 |

| 6 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 26.11, 8.21 | 33.24, 9.18 | 58.33, 18.71 | 73.33, 31.57 |

| 12 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 8.33, 3.54 | 15.29, 5.72 | 37.78, 13.02 | 48.33, 25.03 |

| 24 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 14.44, 6.35 | 21.47, 7.45 | 45.00, 15.41 | 66.67, 25.63 |

| 32 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 21.11, 8.58 | 30.59, 4.96 | 59.44, 13.1 | 71.67, 31.41 |

| 48 kHz ABR Thr (dB SPL), SD | 25.00, 4.33 | 35.29, 6.24 | 67.78, 16.6 | 73.33, 20.66 |

NH = normal hearing, HL = hearing loss, Thr = Threshold, SD = standard deviation

Microarray gene expression

Five glutamate-related probes showed significant, near significant or high fold changes for the subject group main effects with ANOVAs, out of sixty-eight genechip probes investigated in the glutamate-related family. These five genes included two glial high-affinity glutamate transporters (Slc1a2 and Slc1a3) (p=0.067 and 0.0319* respectively), a vesicular glutamate transporter (Slc17a6) (p=0.4018), pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase enzyme (Pycs) (p=0.089) and glutamate receptor inotropic kainate 3 (Grik3) (p=0.1462). Table (2) shows the average fold changes of these different genes. These five genes were selected for validation with real-time PCR (qPCR).

Real-time PCR (qPCR)

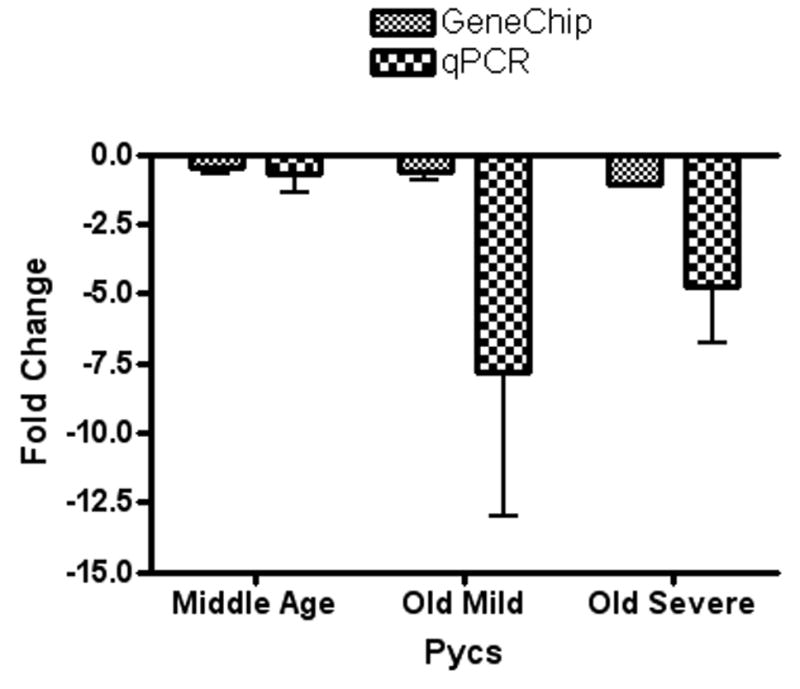

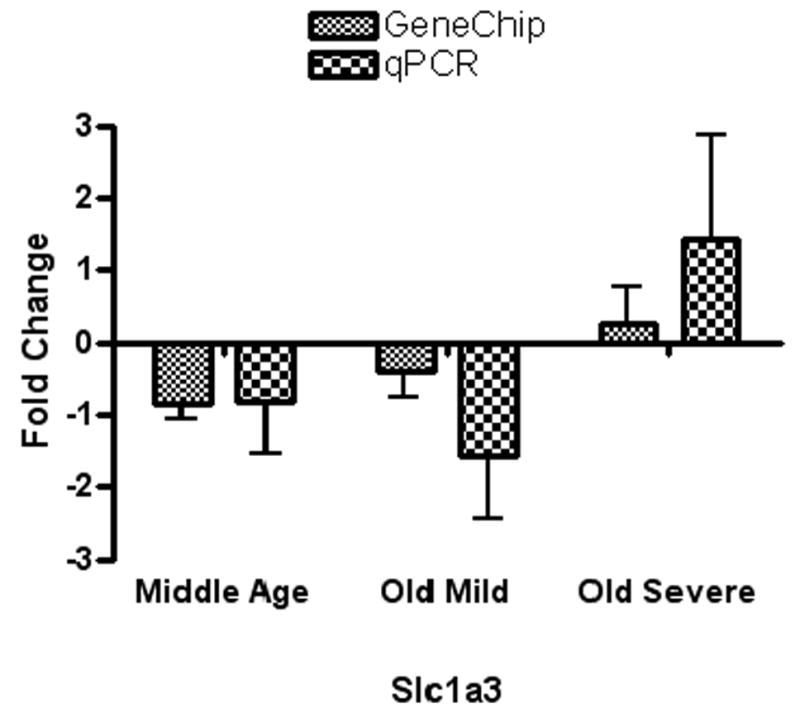

Two genes out of the five significant microarray genes showed comparable results for both the genechip and the qPCR. These two genes were pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase enzyme (Pycs) which showed a significant down-regulation in the older subject groups compared to the young group (p=0.0497*, F= 2.879) and a high-affinity glutamate transporter (Slc1a3) that showed an up-regulation in the old severe hearing loss group compared to the other groups. For the other three genes, qPCR results did not show consistent results with the genechip data. Figures 1-A and 1-B show quantitative comparisons between fold changes for the genechip microarray expression changes and those for the qPCR.

Figure 1.

A): For both GeneChip and real-time PCR, fold changes of Pycs enzyme gene expression in the inferior colliculus of middle age, old mild hearing loss, and old severe hearing loss groups showed down-regulation with age. B): For both GeneChip and real-time PCR, fold changes of high affinity glutamate transporter Slc1a3 gene expression in inferior colliculus samples showed up-regulation in the old severe hearing loss group compared to the other subject groups.

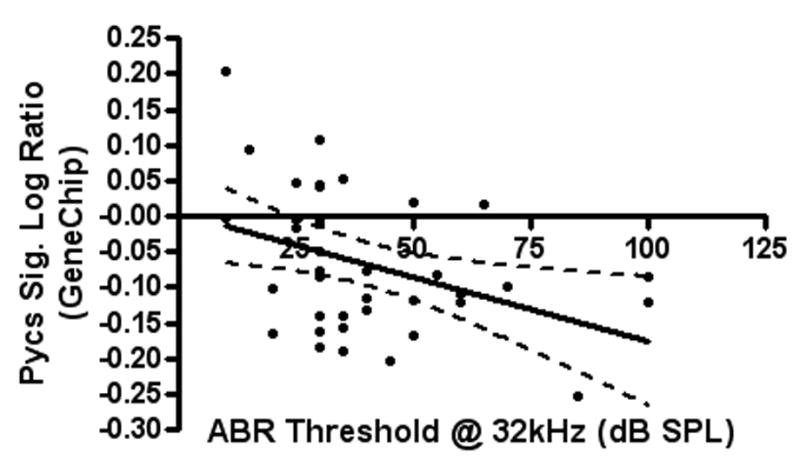

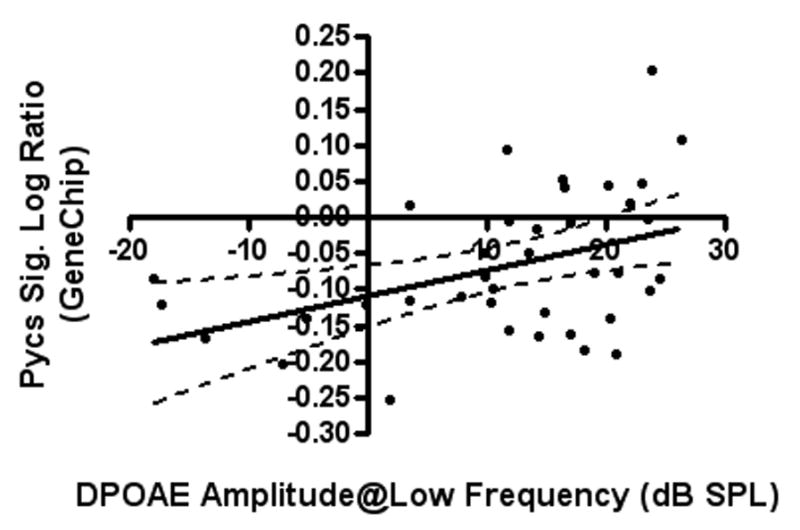

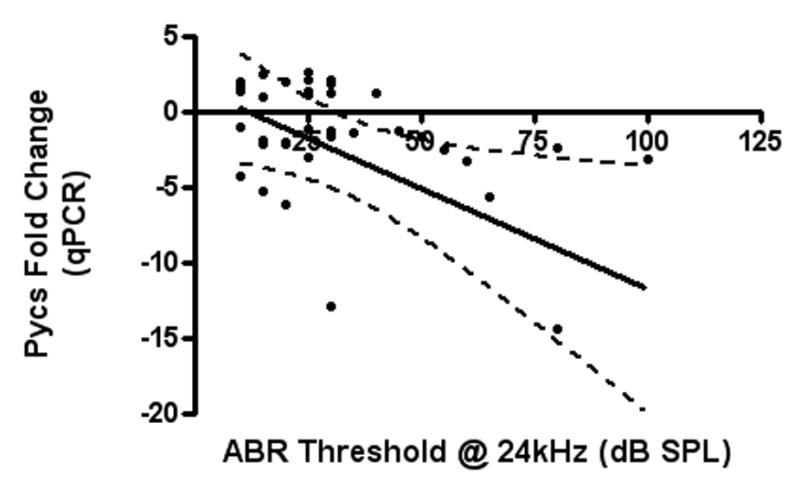

Correlation between gene expression and hearing measurements

Linear regression tests were used to analyze the correlations between hearing measurements (ABR thresholds and DPOAE amplitudes) and gene expression for both the genechip and qPCR. For Pycs gene expression down-regulation, genechip signal log ratios showed statistically significant correlations with ABR thresholds (at 32 and 48 kHz) (Figure 2-A) and DPOAE amplitudes (in low, middle and high frequency ranges) (Figure 2-B). In addition, the qPCR fold change results of the same gene showed statistically significant correlations with ABR thresholds (at 24 kHz) (Figure 2-C) (Table 3).

Figure 2.

A) and B): The correlations between signal log ratios of Pycs enzyme gene expression GeneChip samples and DPOAE amplitudes of the low frequency range, and ABR thresholds at 32 kHz, are two examples of the significant correlations of gene expression changes with the hearing test results. C): The correlation between qPCR fold change of the Pycs enzyme gene expression and ABR thresholds at 24 kHz was statistically significant.

Table 3.

Statistically significant correlations between functional hearing measures and pycs gene expression down-regulation in the inferior colliculus

| P Value | r² | F | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABR 24 kHz (qPCR) | 0.0255 | 0.128 | 5.42 |

| ABR 32 kHz (GeneChip) | 0.0149 | 0.154 | 6.54 |

| ABR 48 kHz (GeneChip) | 0.0080 | 0.179 | 7.87 |

Discussion

Glutamate plays a major role as an excitatory neurotransmitter in the auditory nervous system. However, neuronal over-stimulation by glutamate is responsible for both acute (McEwen and Magarinos, 1997; Akins and Atkinson, 2002) and chronic (Coyle and Puttfarcken, 1993; Doble, 1999; Hertz et al., 1999; Obrenovitch et al., 2000; Atlante et al., 2001; Pitt et al., 2003) neurodegenerative conditions. Excitotoxicity results from over-exposure of neurons to high concentrations of glutamate as a result of increased synthesis activity, decreased levels of catabolism, decreased transporter activity, and delayed re-uptake from the synaptic cleft after its release into the synapse.

The imbalance between excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitters in brain may be an important factor in age related hearing loss. GABA is one of the main inhibitory neurotransmitters that down-regulated with age in the auditory brainstem (Caspary et al., 1990, 1995; Helfert et al., 1999). As we suggest a disturbance in the glutamate-related metabolic pathways, it may contribute to that excitatory/inhibitory neurotransmitters imbalance.

More than one mechanism of glutamate toxicity had been suggested. The most accepted mechanism is mediated by N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, causing increased, toxic intracellular calcium ion concentrations and activation of calcium-dependent proteases, such as calpains, and apoptotic protein caspases, which damage vital cell organelles including mitochondria (Zhivotovsky et al., 1997; Martin et al., 1998; Zeron et al., 2004; Jiang et al., 2005; Das et al., 2005; Fernandez et al., 2005). As a result of these intracellular toxicities, these pathways initiated by excess glutamate may lead to either apoptotic (in lower concentrations) or necrotic (in higher concentrations) neuronal death (Das et al., 2005). Though there is no evidence of the typical apoptotic changes seen in certain other areas of the brain in the inferior colliculus with age, the synaptic loss in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus and its correlation with presbycusis in the C57 mice (Kazee et al, 1995) may be a sign of cellular dysfunction in cases where inputs from the cochlea decline with age.

The current investigation discovered that glutamate gamma-semialdehyde synthetase (pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase) (Pycs) is down-regulated in old mild and old severe presbycusis. In addition, significant correlations between Pycs gene expression and both DPOAE amplitudes and ABR thresholds were established. Pycs is a mitochondrial inner membrane enzyme that catalyzes glutamate to pyrroline-5-carboxylate (P5C). This is a critical step in the biosynthesis of proline and ornithine (Hu et al., 1999; Aral et al., 1996; Kamoun et al., 1998). Though acute proline administration in high doses induces oxidative stress due to reduction of antioxidants in brain, chronic treatment or normal proline levels significantly increase antioxidant enzyme catalase (CAT) in rat brain (Delwing et al, 2003).

Proline is an essential amino acid for synthesis of proline-rich-polypeptide (PRP), Insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) and Glycine-proline-glutamate (GPE). PRP-1 which contains 15 amino acid residues has been suggested to play a role as a universal neuroprotective agent and neuromodulator (Galoyan, 2001; Galoyan et al., 2004; Abrahamyan et al., 2004). IGF-1 is a naturally occurring peptide in the central nervous system. GPE is the N-terminal tripeptide of IGF-1 that naturally cleaved in the plasma and brain tissue and has a neuroprotective effect in various ischemic brain injuries (Guan et al., 1999, 2004; Alexi et al., 1999; Aberg et al., 2000; O’Donnell et al., 2002; Baker et al., 2005). Therefore, proline, in normal levels, is an essential amino acid for neural protection against oxidative metabolites, and Pycs deficiency in old age in the inferior colliculus may contribute to both glutamate accumulation and proline deficiency. This may lead to glutamate toxicity in addition to loss of the neuroprotective effects of proline and its compounds that may, in turn, contribute to the central pathogenesis of presbycusis.

Glial high-affinity glutamate transporters play an extremely important role in preventing glutamate toxicity in both peripheral and central systems. Changes in glutamate transporter expression may affect auditory processing functions through modulation of glutamate excitotoxicity (Hakuba et al., 2000; Furness et al., 2002; Furness and Lawton, 2003; Rebillard et al., 2003; Shimizu et al., 2005). Glial high affinity glutamate transporter (Slc1a3, GluT-1, GLAST) is up-regulated in the inferior colliculus of the old presbycusic subject group. This may embody a neuronal defensive mechanism against increased glutamate concentrations that develop with age. The less dramatic, though significant, increase in Slc1a3 in the old severe hearing loss group may help explain the following sequence of events for the two old age subject groups. The average age of the old mild subject group was 27.7 +/− 3.4 months, and the old severe hearing loss group was 30.6 +/− 1.3 months. The Pcys changes start at an earlier time in old age, which in turn participates in or triggers glutamate excitotoxicity, which has a negative affect on hearing, which then further stimulates the compensatory mechanism involving the Slc1a3 upregulation in the oldest subject group. In addition, the time-delayed compensatory response of the Slc1a3 upregulated gene expression in the very old mice may explain the lack of correlation between that gene expression and the lack of response plasticity for the functional auditory results of the oldest subject group. This delayed upregulation may occur too late in life to have a significant impact on the physiological hearing measures of the present investigation.

Conclusion

The down-regulation of Pycs enzyme gene expression with age in the auditory midbrain may be an important factor in glutamate accumulation and toxicity, in addition to the loss of the neuroprotective effects of proline and praline-related proteins in old age, particularly in cases where there is severe hearing loss compounding the situation. The up-regulation of glial high affinity transporter in old age mice may be a defense mechanism against glutamate toxicity.

Table 2.

Gene expression fold change means and standard deviations in the inferior colliculus, relative to the gene expression in young adult mice with normal hearing, for the middle age and old subject groups

| GeneChip Average Fold Change, SD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene ID | Gene Name | Gene Function | Middle Age | Old Mild | Old Severe |

| 1452031_at | SLC1A3 (GluT-1/GLAST) | Glial High Affinity Glutamate Transporter | −0.86, 0.798 | −0.40, 1.095 | 0.26, 1.18 |

| 1415836_at | PYCS | Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase | −0.45, 0.995 | −0.63, 0.93 | −1.11, 0.035 |

| 1451627_a_at | SLC1A2 (GLT-1) | Glial High Affinity Glutamate Transporter | 0.31, 1.2 | −0.44, 1.15 | −0.36, 1.26 |

| 1418610_at | SLC17A6 (VGluT1) | Solute Carrier Family 17 (vesicle transporter) | −1.36, 1.16 | −1.72, 0.64 | −2.08, 0.61 |

| 1427709_at | GRIK3 | Glutamate Receptor, Inotropic, Kainate 3 | 0.31, 1.06 | 0.11, 1.09 | −1.05, 0.022 |

Acknowledgments

We thank John Housel for collecting the ABR recordings. Supported by NIH Grants P01 AG09524 from the National Institute on Aging, P30 DC05409 from the National Institute on Deafness & Communication Disorders, and the International Center for Hearing and Speech Research, Rochester NY.

Abbreviations

- ABR

auditory brainstem response

- DPOAEs

distortion product otoacoustic emissions

- qPCR

Real-time PCR

- Pycs

Pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase enzyme

- Slc1a3

Solute carrier family 1 member 3

- Slc1a2

Solute carrier family 1 member 2

- Slc17a6

Solute carrier family 17 member 6

- P5C

pyrroline-5-carboxylate

- CAT

Catalase enzyme

- PRP

Proline-rich-polypeptide

- GPE

Glycine-proline-glutamate

- IGF-1

Insulin-like growth factor-1

- GABA

gamma-aminobutyric acid

- NMDA

N-methyl-D-aspartate

- AMPA

Alpha amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aberg MA, Aberg ND, Hedbacker H, Oscarsson J, Eriksson PS. Peripheral infusion of IGF-I selectively induces neurogenesis in the adult rat hippocampus. J Neurosci. 20:2896–2903. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02896.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abrahamyan SS, Sarkissian JS, Meliksetyan IB, Galoyan AA. Survival of trauma-injured neurons in rat brain by treatment with proline-rich peptide (PRP-1): an immunohistochemical study. Neurochem Res. 2004;29(4):695–708. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000018840.19073.0b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akins PT, Atkinson RP. Glutamate AMPA receptor antagonist treatment for ischaemic stroke. Curr Med Res Opin. 2002;18(2):s9–s13. doi: 10.1185/030079902125000660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexi T, Hughes PE, Van Roon-Mom WM, Faull RL, Williams CE, Clark RG, Gluckman PD. The IGF-I amino-terminal tripeptide glycine-proline-glutamate (GPE) is neuroprotective to striatumin the quinolinic acid lesion animal model of Huntington’s disease. Exp Neurol. 1999;159:84–97. doi: 10.1006/exnr.1999.7168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aral B, Schlenzig JS, Liu G, Kamoun P. Database cloning human delta 1-pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthetase (P5CS) cDNA: a bifunctional enzyme catalyzing the first 2 steps in proline biosynthesis. Comptes Rendus de L’Academie des Sciences. 1996;319(3):171–178. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlante A, Calissano P, Bobba A, Giannattasio S, Marra E, Passarella S. Glutamate neurotoxicity, oxidative stress and mitochondria. FEBS Lett. 2001;497:1–5. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)02437-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baik SY, Jung KH, Choi MR, Yang BH, Kim SH, Lee JS, Oh DY, Choi IG, Chung H, Chai YG. Fluoxetine-induced up-regulation of 14-3-3zeta and tryptophan hydroxylase levels in RBL-2H3 cells. Neurosci Lett. 2005;374:53–57. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.10.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker AM, Batchelor DC, Thomas GB, Wen JY, Rafiee M, Lin H, Guan J. Central penetration and stability of N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-I, glycine-proline-glutamate in adult rat. Neuropeptides. 2005;39:81–87. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2004.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caicedo A, Eybalin M. Glutamate receptor phenotypes in the auditory brainstem and mid-brain of the developing rat. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:51–74. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00410.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen SM, Nadler JV. Proline-induced potentiation of glutamate transmission. Brain Res. 1997;761:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)00352-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyle JT, Puttfarcken P. Oxidative stress, glutamate, and neurodegenerative disorders. Science. 1993;262:689–695. doi: 10.1126/science.7901908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Raza A, Lawhorn-Armour BA, Pippin J, Arneric SP. Immunocytochemical and neurochemical evidence for age-related loss of GABA in the inferior colliculus: Implications for neural presbycusis. J Neurosci. 1990;10:2363–2372. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.10-07-02363.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caspary DM, Milbrandt JC, Helfert RH. Central auditory aging: GABA changes in the inferior colliculus. Exp Gerontol. 1995;30:349–360. doi: 10.1016/0531-5565(94)00052-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Das A, Sribnick EA, Wingrave JM, Del Re AM, Woodward JJ, Appel SH, Banik NL, Ray SK. Calpain activation in apoptosis of ventral spinal cord 4.1 (VSC4.1) motoneurons exposed to glutamate: calpain inhibition provides functional neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2005;81:551–562. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delwing D, Bavaresco CS, Chiarani F, Wannmacher CMD, Wajner M, Dutra-Filho CS, Wyse ATS. In vivo and in vitro effects of proline on some parameters of oxidative stress in rat brain. Brain Res. 2003;991:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2003.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doble A. The role of excitotoxicity in neurodegenerative disease: implications for therapy. Pharmacol Ther. 1999;81:163–221. doi: 10.1016/s0163-7258(98)00042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faingold CL. Role of GABA abnormalities in the inferior colliculus pathophysiology – audiogenic seizures. Hear Res. 2002;168:223–237. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(02)00373-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feliciano M, Potashner SJ. Evidence for a glutamatergic pathway from the guinea pig auditory cortex to the inferior colliculus. J Neurochem. 1995;65:1348–1357. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.65031348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez M, Pirondi S, Antonelli T, Ferraro L, Giardino L, Calza L. Role of c-Fos protein on glutamate toxicity in primary neural hippocampal cells. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:115–125. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness DN, Hulme JA, Lawton DM, Hackney CM. Distribution of the glutamate / aspartate transporter GLAST in relation to the afferent synapses of outer hair cells in the guinea pig cochlea. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2002;3:234–247. doi: 10.1007/s101620010064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furness DN, Lawton DM. Comparative distribution of glutamate transporters and receptor in relation to afferent innervation density in the mammalian cochlea. J Neurosci. 2003;23(36):11296–11304. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-36-11296.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galoyan AA. Neurochemistry of brain neuroendocrine immune system: signal molecules. Neurochem Res. 2001;25:1343–1355. doi: 10.1023/a:1007656431612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galoyan AA, Shakhlamov VA, Aghajanov MI, Vahradyan HG. Hypothalamic proline-rich polypeptide protects brain neurons in aluminum neurotoxicosis. Neurochem Res. 2004;29(7):1349–1357. doi: 10.1023/b:nere.0000026396.77459.1f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaza WC, Ribak CE. Immunocytochemical localization of AMPA receptors in the rat inferior colliculus. Brain Res. 1997;774:175–183. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)81701-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giulietti A, Overbergh L, Valckx D, Decallonne B, Bouillon R, Mathieu C. An overview of real-time quantitative PCR: Applications to quantify cytokine gene expression. Methods. 2001;4:386–401. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith JD, Kujawa SG, McLaren JD, Bledsoe SC., Jr In vivo release of neuroactive amino acids from the inferior colliculus of the guinea pig using brain microdialysis. Hear Res. 1995;83:80–88. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(94)00193-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, Bennet L, George S, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Gluckman PD, Keunen H, Gunn AJ. Selective neuroprotective effects with insulin-like growth factor-1 in phenotypic striatal neurons following ischemic brain injury in fetal sheep. Neurosci. 1999;95:831–839. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(99)00456-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guan J, Thomas GB, Lin H, Mathai S, Batchelor DC, George S, Gluckman PD. Neuroprotective effects of the N-terminal tripeptide of insulin-like growth factor-1, glycine-proline-glutamate (GPE) following intravenous infusion in hypoxic-ischemic adult rats. Neuropharmacol. 2004;47:892–903. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guimaraes P, Zhu X, Cannon T, Kim S, Frisina RD. Sex differences in distortion product otoacoustic emissions as a function of age in CBA mice. Hear Res. 2004;192(1–2):83–89. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2004.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hakuba N, Koga K, Gyo K, Usami S, Tanaka K. Exacerbation of noise-induced hearing loss in mice lacking the glutamate transporter GLAST. J Neurosci. 2000;20(23):8750–8753. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-23-08750.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Helfert RH, Sommer TJ, Meeks J, Hofstetter P, Hughes LF. Age-related synaptic changes in the central nucleus of the inferior colliculus of Fischer-344 rats. J Comp Neurol. 1999;406:285–298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertz L, Dringen R, Schousboe A, Robinson SR. Astrocytes: glutamate producers or neurons. J Neurosci Res. 1999;57:417–428. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu CA, Lin W, Obie C, Valle D. Molecular enzymology of mammalian Δ1 –pyrroline-5-carboxylate synthase. J Biol Chem. 1999;274(10):6754–6762. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.10.6754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobson M, Kim S, Romney J, Zhu X, Frisina RD. Contralateral suppression of distortion-product otoacoustic emissions declines with age: A comparison of findings in CBA mice with human listeners. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(10):1707–1713. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200310000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang KW, Yu ZS, Shui QX, Xia ZZ. Activation of ATP-sensitive potassium channels prevents the cleavage of cytosolic mu-calpain and abrogates the elevation of nuclear c-Fos and c-Jun expressions after hypoxic-ischemia in neonatal rat brain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 2005;133:87–94. doi: 10.1016/j.molbrainres.2004.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamoun P, Aral B, Saudubray JM. A new inherited metabolic disease: delta 1-pyrroline 5-carboxylate synthetase deficiency. Bulletin de L’Academie Nationale de Medecine. 1998;182(1):131–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao WH, Van Den AT, Herman P, Frachet B, Huy PT, Lecain E, Marianowski R. Expression of NMDA, AMPA and GABA(A) receptor subunit mRNAs in the rat auditory brainstem. II Influence of intracochlear electrical stimulation. Hear Res. 2000;150:12–26. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00167-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin LJ, Al-Abdulla NA, Brambrink AM, Kirsch JR, Sieber FE, Portera-Cailliau C. Neurodegeneration in excitotoxicity, global cerebral ischemia, and target deprivation: a perspective on the contributions of apoptosis and necrosis. Brain Res Bull. 1998;46:281–309. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(98)00024-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, Magarinos AM. Stress effects on morphology and function of the hippocampus. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1997;821:271–284. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1997.tb48286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore DR, Kotak VC, Sanes DH. Commissural and lemniscal synaptic input to the gerbil inferior colliculus. J Neurophysiol. 1998;80:2229–2236. doi: 10.1152/jn.1998.80.5.2229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newsholme P, Lima MMR, Procopio J, Pithon-Curi TC, Doi SQ, Bazotte RB, Curi R. Glutamine and glutamate as vital metabolites. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2003;36(2):153–163. doi: 10.1590/s0100-879x2003000200002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell SL, Frederick TJ, Krady JK, Vannucci SJ, Wood TL. IGF-I and microglia / macrophage proliferation in the ischemic mouse brain. Glia. 2002;39:85–97. doi: 10.1002/glia.10081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrenovitch TP, Urenjak J, Zilkha E, Jay TM. excitotoxicity in neurological disorders – the glutamate paradox. Int J Dev Neurosci. 2000;18:281–287. doi: 10.1016/s0736-5748(99)00096-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parks TN. The AMPA receptors of auditory neurons. Hear Res. 2000;147:77–91. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00122-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitt D, Nagelmeier IE, Wilson HC, Raine CS. Glutamate uptake by oligodendrocytes: implications for excitotoxicity in multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2003;61:1113–1120. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000090564.88719.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rebillard G, Ruel J, Nouvian R, saleh H, Pujol R, Dehnes Y, Raymond J, Puel JL, Devau G. Glutamate transporters in the guinea-pig cochlea: partial mRNA sequences, cellular expression and functional implications. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:83–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02429.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saint Marie RL. Glutamatergic connections of the auditory midbrain: selective uptake and axonal transport of D-[3h]aspartate. J Comp Neurol. 1996;373:255–270. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9861(19960916)373:2<255::AID-CNE8>3.0.CO;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y, Hakuba N, Hyodo J, Taniguchi M, Gyo K. Kanamycin ototoxicity in glutamate transporter knockout mice. Neurosci Lett. 2005;380:243–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2005.01.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suneja SK, Benson CG, Gross J, Potashner SJ. Evidence for glutamatergic projections from the cochlear nucleus to the superior olive and the ventral nucleus of the lateral lemniscus. J Neurochem. 1995;64:161–171. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1995.64010161.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suneja SK, Potashner SJ, Benson CG. AMPA receptor binding in adult guinea pig brain stem auditory nuclei after unilateral cochlear ablation. Exp Neurol. 2000;165:355–369. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tadros SF, D’Sousa M, Zettel ML, Zhu X, Erhardt ML, Frisina RD. Serotonin 2B receptor: Upregulated with age and hearing loss in mouse auditory system. Neurobiol Aging. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2006.05.021. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto Y. Depressor responses to L-proline microinjected into the rat ventrolateral medulla are mediated by ionotropic excitatory amino acid receptors. Autonom Neurosci. 2005;120:108–112. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2005.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varghese GI, Zhu X, Frisina RD. Age-related declines in distortion product otoacoustic emissions utilizing pure tone contralateral stimulation in CBA/CaJ mice. Hear Res. 2005;209:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2005.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeron MM, Fernandes HB, Krebs C, Shehadeh J, Wellington CL, Leavitt BR, Baimbridge KG, Hayden MR, Raymond LA. Potentiation of NMDA receptor-mediated excitotoxicity linked with intrinsic apoptotic pathway in YAC transgenic mouse model of Huntington’s disease. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;25:469–479. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhivotovsky B, Burgess DH, Vanags DM, Orrenius S. Involvement of cellular proteolytic machinery in apoptosis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;230:481–488. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.6016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]