Abstract

Background

Increasing levels of youth obesity constitute a threat to the nation’s health, and identification of the influences during childhood that lead to youth obesity is urgently needed. Physical activity is one such influence that is potentially modifiable.

Purpose

This study examined the influence of children’s social images of other children who engage in physical activity on the development of their own physical activity over 3 years and related growth in physical activity to levels of obesity 2 years later.

Methods

Participants (N = 846, 50% female) were members of the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project, a longitudinal study of a community sample. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 86% Caucasian; 7% Hispanic; 1% Black; and approximately 2% each of Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaskan Native, and other or mixed race/ethni-ethnicity. The mean age at the first assessment was 9.5 years. A model examining the effect of early social images on the growth of physical activity (athleticism modeled as a curve of factors) predicting obesity was evaluated using latent growth modeling.

Results

More favorable social images predicted the initial levels (i.e., intercept) but not the change over time (i.e., slope) of children’s athleticism, and both the intercept and the slope of athleticism predicted obesity.

Conclusions

Children’s social images of exercise in early childhood influence their subsequent activity levels, and hence obesity, and should be targeted in obesity prevention interventions.

INTRODUCTION

Finding ways to alter the course of our fattening world, particularly for children, is a global health priority. There are many causes of obesity, only some of which are modifiable. However, the most proximate cause, an excess of calories consumed relative to calories expended, results from behavioral patterns of eating and physical activity that are potentially amenable to change. Eating and exercising are influenced by numerous cultural, behavioral, and biological factors. The aim of this study was to evaluate one of these many influences, namely, the development of a cognitive-behavioral mechanism involving children’s social images (also known as prototypes) of physical activity during childhood that was hypothesized to be related prospectively to obesity. The identification of such a mechanism originating in childhood leading to adolescent obesity may offer new possibilities for early interventions to prevent the development of obesity.

Childhood obesity has risen exponentially over the past 3 decades in the United States. Using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys, 1999-2002, it is estimated that 31% of 6- to 19-year-olds either were at risk for overweight or were overweight (i.e., body mass index [BMI] for age and gender equal or greater than the 85th percentile) and 16% were overweight (i.e., BMI equal or greater than the 95th percentile) (1). Overweight children tend to become overweight adults (2,3), and obesity in youth has enduring health consequences (4). For example, Hyppönen, Power, and Davey Smith (5) discovered a 22.9% increase in risk of type 2 diabetes at age 41 among those already obese by age 23 compared to those of normal weight. Interventions that target early risk factors for developing obesity over childhood and adolescence are urgently needed to improve child health.

Children and adolescents are preoccupied with their appearance, particularly their weight. As early as elementary school, children have negative images of obesity (6) and desire to be thinner (7). According to the Prototype/Willingness Model (8-10), prototypes or social images are important determinants of adolescents’ willingness to engage in risky behaviors. Prototypes (social images) are similar to attitudes in that they have strong affective connotations. Behaviors that are associated with positive affect are perceived as more attractive, and they are evaluated as less risky because judgments of risk are based on feelings as well as reasoning (11). Consequently, young people with more favorable images of youth who smoke, drink, or use substances are more likely themselves to smoke (12), drink (13), or use substances (9). Similar results have been independently replicated for intentions to smoke and drink, and actual smoking and drinking in the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project (14-18).

Most past research has related social images to unhealthy behaviors but more recently social images have been related to health-protective behaviors such as exercise and healthy eating. In an experimental study, among college students who were instructed to think about the social image of an exerciser or nonexerciser, those with a higher tendency to compare themselves to others subsequently increased their own exercise behavior (19). Rivis and Sheeran (20) found that the combination of favorable exercise prototypes and knowing a lot of people who exercise (descriptive norms) predicted exercise behavior. Jang, Pomery, and Gibbons (21) related change in the prototype of a health-conscious person to change in diet consciousness (i.e., eating a low-fat, high-fiber diet), and diet consciousness was related to change in BMI. Based on this past research, in the study presented here children’s social images of other kids who exercise were expected to influence their own engagement in physical activity such that those with relatively favorable images would exercise more.

Studies have found that physical activity levels decrease during school-age years (22), beginning at about age 11 to 12 and continuing through adolescence (23). Early adolescence may also be a critical period for the development of enduring obesity. For example, a recent longitudinal study found that girls who were overweight at age 11 were up to 30 times more likely to be obese as young adults (24). The decline in physical activity in adolescence may be a contributing factor to weight gain at this life stage, therefore better understanding of mechanisms influencing teenage physical activity is needed. Given that physical activity tends to decline, it is important to study the factors predicting activity levels in childhood and their subsequent decline in adolescence. This calls for a longitudinal study with repeated assessments of activity levels, and an analytic technique that enables the prediction of initial levels and change in a variable over time. Latent growth modeling (LGM) enables the study of these two parameters (25). Using LGM, predictors of both the initial level (intercept) and change over time (slope) of the latent construct can be evaluated. For example, using LGM, Duncan, Strycker, and Chaumeton (26) identified a number of risk and protective factors for decline in youth physical activity over time, including self-efficacy and peer support.

The study presented here examined the influence of children’s early social images of other children who engage in physical activity on their own subsequent physical activity trajectories and related these trajectories of physical activity to subsequent levels of obesity. Using LGM, we tested a model that incorporated the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Children’s social images of other children who exercise will predict their own subsequent level of engagement and change in physical activity over time such that those with more favorable images will exercise at a higher level and decline less relative to those with less favorable images.

Hypothesis 2: Higher levels of physical activity and less decline in physical activity over time will predict lower levels of subsequent obesity.

Given previous findings indicating that boys are more physically active than girls (25-27), potential effects of gender were also evaluated.

This model was tested by relating elementary school children’s social images of exercisers at the first assessment (T1) to their own athleticism assessed over a subsequent 3-year period (T2, T3, and T4), and to their obesity assessed by parent and self-reports when participants were in middle and high school (T6). Participants were members of the Oregon Youth Substance Use Project, a longitudinal study of a community sample examining risk and protective factors for adolescent substance use including smoking, alcohol use, and other health-related behaviors including exercise (15).

METHODS

Design

The Oregon Youth Substance Use Project employed a cohort-sequential design in which five grade cohorts (Grades 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 at the first assessment; N = 1,075) were assessed annually over 4 years (T1-T4), until they were in the 5th through 8th grades. The fifth assessment (not used for this study) took place 2 years after T4, and the sixth assessment (T6) took place 3 years after T4, when participants were in Grades 8 to 11.

Participants and Recruitment

Using stratified random sampling, children were recruited from 15 elementary schools in one school district in western Oregon serving a predominantly working class community (see 15 for more details). The sample analyzed here consisted of 846 children in Grades 2 to 5 at T1 (424 boys and 422 girls) who participated in the first assessment at T1 and at least one of the following assessments: T2, T3, T4, or T6. An average of 212 students in each of the second through fifth grades participated. The average age of participants at each time of assessment was as follows: T1 = 9.5 years, T2 = 10.4 years, T3 = 11.5 years, T4 = 12.4 years, and T6 = 15.6 years. The racial/ethnic composition of the sample was 86% Caucasian; 7% Hispanic; 1% Black; and approximately 2% each of Asian/Pacific Islander, American Indian, or Alaskan Native, and other or mixed race/ethnicity. Approximately 6% of mothers and 6% of fathers had not obtained a high school diploma, and 40% of the sample was eligible for a free or reduced lunch, an indicator of low family income. Participants were representative of other children in the school district in terms of race/ethnicity, participation in the free or reduced lunch program, and substance use but had slightly higher achievement test scores in reading and math. Of the 1,070 children who participated at T1, 120 did not participate at T6. Nonparticipants at T6 did not differ from the entire sample at T1 on gender, race, parents’ education level, percentage participating the free or reduced lunch program, or T1 social images of kids who exercise.

Procedures

Child assessments were conducted in the schools. The second- and third-grade assessments were by interviews, whereas older children completed paper-and-pencil surveys in a group setting. In a separate study of fourth graders, no differences in responses between the two methods were observed (15). Parents were sent a questionnaire annually that included questions on their child’s current height and weight.

Measures

Social images

At T1, children in second and third grades were shown a picture of a kid playing soccer and were asked whether they thought that kids who exercise are “cool or neat,” “liked by other kids,” and “exciting.” Children in older grades at T1 responded to equivalent questionnaire items. Response options for all grades were no, maybe, or yes. These three items were used as indicators of the latent construct of social images at T1 of kids who exercise.

Athleticism

At T2, T3, and T4, all the children rated themselves on “Gets exercise such as playing soccer”; “Good at sports” (not true, sometimes true, or very true); and “Compared to others of your age and sex, how much exercise (such as roller blading or riding a bike) do you get?” (1 = much less than others, 5 = much less than others). At T1, only the older children (Grades 4 and 5) rated these items. Exploratory factor analyses of these items assessed at T2, T3, and T4 generated one-factor solutions accounting for 54%, 60%, and 61% of the variance, respectively. These three items were used as indicators of the latent construct of athleticism assessed at T2, T3, and T4.

Obesity

Three measures were used to assess this construct at T6. Mothers and fathers were asked to provide their child’s height in feet and inches, and weight in pounds, from which their child’s BMI (kg/m2) was derived. The correlation between mothers’ and fathers’ reports of their children’s BMI was r = .87 (N = 524, p < .001). Given this high level of agreement, and the fact that 38% of fathers’ BMI reports were missing at T6, only mothers’ T6 BMI reports were used (or father’s report if mother’s was missing). These were adjusted for the child’s age and gender using tables provided by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (28). At T6, self-reports of height and weight were also available and were converted into BMI adjusted for gender and age. In addition, children identified which of nine gender-matched line drawings of body shapes varying in fatness (ranging from 1 = under-underweight to 9 = obese) best described them (29). These three T6 measures were highly intercorrelated, and an exploratory factor analysis generated one factor accounting for 83% of the variance. These items were used as indicators of the latent construct of obesity.

BMI at T1 was assessed by mother’s report of height and weight and converted to age- and gender-adjusted BMI (father’s report was used if no mother’s report was available).

Statistical Analysis

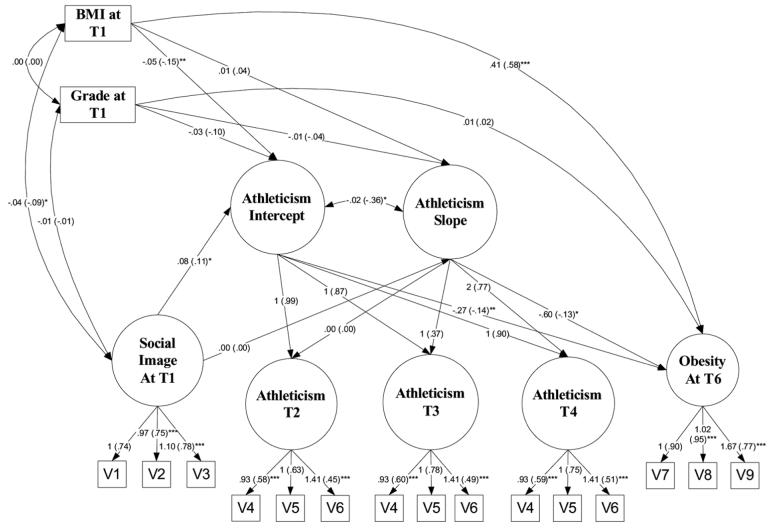

LGM (30,31) was used to relate social images assessed at T1 to change in physical activity over time (T2, T3, and T4) and subsequent obesity measured as a latent construct at T6 (see Figure 1). Social images at T1 were assessed as a latent construct with three indicator variables (see V1, V2, and V3 in Figure 1). Obesity at T6 was assessed as a latent construct with three indicators (see V7, V8, and V9 in Figure 1). Athleticism was assessed by three indicator variables (V4, V5, and V6 in Figure 1) at each of three successive assessments (T2, T3, and T4) so that change over time could be examined. To do this, within the overall model, a curve-of-factors LGM (25,31) was used to model developmental change in the latent construct of athleticism. This may be understood as a two-step process: First the latent construct of athleticism was estimated at each time of assessment, and then a growth curve was fitted to these three latent constructs (athleticism at T2, T3, and T4). This growth curve is represented by two latent constructs, the intercept and slope (Athleticism Intercept and Athleticism Slope; see Figure 1). To estimate the latent construct of athleticism at each time of assessment, the curve-of-factors LGM assumes factor invariance over each assessment (i.e., the same factor measured by the same indicators with equal weighting of indicators over time). One physical activity variable was used as the scaling reference for the first-order common factors (V5, “Get exercise”), and the loadings for the other two variables were constrained to be equal across time. The factor loadings for the intercept were fixed at 1, and the factor loadings for the slope were fixed to represent a linear growth trend (0, 1, and 2). Athleticism tends to decrease over adolescence, so a negative slope was predicted. The variance of the initial level and of the slope of athleticism should be significant indicating that there are individual differences in initial level and slope that can be predicted and be used to predict level of obesity at T6.

FIGURE 1.

Final model of predictors of obesity for the entire sample showing unstandardized regression coefficients (with standardized regression coefficients in parentheses). Latent constructs are shown as circles, observed variables as rectangles. Indicators of social image at T1: V1 = “Cool or neat,” V2 = “Liked by others,” V3 = “Exciting.” Indicators of athleticism at T2, T3, and T4: V4 = “Good at sports,” V5 = “Get exercise,” V6 = “Compared to others.” Indicators of obesity at T6: V7 = parent report of BMI, V8 = self report of BMI, and V9 = self report of body shape. Paths from the latent constructs to their indicators (V1-V9) have arrowheads pointing to the indicators (rectangles). Other single-headed arrows depict structural paths, whereas double-headed arrows depict correlations. BMI = body mass index. *p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

The hypothesis that social images at T1 would predict growth in athleticism was evaluated by the paths from social image to the intercept and slope of athleticism. The hypothesis that athleticism would predict obesity at T6 was evaluated by the paths from the intercept and slope of athleticism to obesity. Grade at T1 was included as a covariate to control for grade/age effects, and age- and gender-adjusted BMI (based on parental report) at T1 was included to control for baseline levels of obesity. To examine gender effects in structural paths and correlations, multiple-sample analysis was used. Structural paths and correlations were initially constrained to be equal between genders and were freed iteratively if a gender difference was indicated through an examination of each modification index. The model was assessed using Mplus, Version 4.1 (32) with full maximum likelihood methods to estimate missing data (33).

RESULTS

Descriptive Statistics

Using mother reports of height and weight converted into age- and gender-adjusted BMI, the sample’s distribution of reported BMI at T6 in each of the four BMI categories for children (underweight, normal, at risk for overweight, and overweight) is shown in Table 1, separately for boys and girls. These proportions indicate that 16% of the sample was in the overweight category, which is comparable to national statistics, and supports the validity of this latent construct as a measure of relative obesity and the representativeness of this sample. Moreover, these data suggest that there is substantial variation in BMI at T6 and that this is a high-risk sample for the development of obesity, with 36% of boys and 35% of girls already at risk of overweight or who were overweight at T6. Table 2 provides the means and standard deviations for all the observed variables in the model.

TABLE 1.

Percentage of Participants in Each Age- and Gender-Adjusted BMI Category at T6 by Cohort and Gender Based on Mothers’ Reports of Children’s BMI (or Fathers’ where no Mothers’ Reports Available)

|

BMI Categories |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Groupa | Underweight | Normal | At Risk for Overweightb | Overweightc | N |

| Cohort 2 | |||||

| Boys | 3.2 | 64.2 | 20.0 | 12.6 | 95 |

| Girls | 1.1 | 62.1 | 18.9 | 17.9 | 95 |

| Cohort 3 | |||||

| Boys | 1.2 | 55.4 | 25.3 | 18.1 | 83 |

| Girls | 1.0 | 64.9 | 19.6 | 14.4 | 97 |

| Cohort 4 | |||||

| Boys | 4.4 | 63.3 | 20.0 | 12.2 | 90 |

| Girls | 2.3 | 61.6 | 19.8 | 16.3 | 86 |

| Cohort 5 | |||||

| Boys | 3.6 | 58.3 | 14.3 | 23.8 | 84 |

| Girls | 0.0 | 66.7 | 19.2 | 14.1 | 78 |

| Overall | |||||

| Boys | 3.1 | 60.5 | 19.9 | 16.5 | 352 |

| Girls | 1.1 | 63.8 | 19.4 | 15.7 | 356 |

Note. For 138 children, neither parent provided a body mass index (BMI) report; hence the overall sample size of 708 in this table is less than the overall sample size of 846 for the study.

Cohort 2 = Grade 2 at T1, Cohort 3 = Grade 3 at T1, Cohort 4 = Grade 4 at T1, Cohort 5 = Grade 5 at T1.

At risk of overweight = BMI between 85th and 95th percentile.

Overweight = BMI greater than 95th percentile.

TABLE 2.

Means and Standard Deviations of All Observed Variables

|

Boys |

Girls |

All |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD |

| T1 Social images | ||||||

| Cool or neat | 1.74 | .56 | 1.67 | .60 | 1.70 | .58 |

| Liked by others | 1.73 | .57 | 1.70 | .56 | 1.71 | .56 |

| Exciting | 1.66 | .61 | 1.61 | .62 | 1.63 | .61 |

| T2 Athleticism | ||||||

| Good at sports | 1.74 | .50 | 1.58 | .60 | 1.66 | .56 |

| Get exercise | 1.73 | .53 | 1.74 | .53 | 1.74 | .53 |

| Compared to others | 3.58 | 1.13 | 3.44 | 1.00 | 3.51 | 1.07 |

| T3 Athleticism | ||||||

| Good at sports | 1.70 | .53 | 1.53 | .67 | 1.61 | .61 |

| Get exercise | 1.78 | .48 | 1.77 | .49 | 1.77 | .49 |

| Compared to others | 3.46 | 1.13 | 3.50 | 1.09 | 3.48 | 1.11 |

| T4 Athleticism | ||||||

| Good at sports | 1.66 | .56 | 1.52 | .64 | 1.59 | .60 |

| Get exercise | 1.76 | .48 | 1.72 | .48 | 1.74 | .48 |

| Compared to others | 3.47 | 1.08 | 3.36 | 1.00 | 3.42 | 1.04 |

| T6 Obesity | ||||||

| Parent report of BMI | -.01 | .75 | -.02 | .69 | -.02 | .72 |

| Self-report of BMI | .01 | .73 | -.06 | .63 | -.02 | .68 |

| Self-report of body image | 3.89 | 1.47 | 3.88 | 1.35 | 3.88 | 1.41 |

| T1 Grade | 3.52 | 1.13 | 3.43 | 1.12 | 3.48 | 1.12 |

| T1 Parent report of BMI | .06 | 1.12 | -.08 | 1.00 | -.01 | 1.06 |

Note. BMI = body mass index; T1-T6 = first through sixth assessment.

Among fourth and fifth graders, the cross-sectional associations between T1 BMI and other T1 variables measuring athleticism indicated that the correlations were small to modest in size (“Gets exercise,” r = - .10; “Good at sports,” r = - .14; “Compared to others, r = - .04”). Among the entire sample, correlations between T1 BMI and social image variables were all small (“Cool or neat,” r = - .05; “Liked by others,” r = .00; “Exciting,” r = - .05).

Measurement Model

A measurement model for the three latent constructs of social images, athleticism (curve of factors), and obesity, without the hypothesized structural paths, was tested first to evaluate the factor structures of the latent variables. The fit indexes were χ2(95, N = 846) = 191.125, p < .001 (comparative fit index [CFI] = .976, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = .035, 90% confidence interval [CI] = .027, .042). Despite the significance of chi-square (which is sensitive to sample size), the other indexes demonstrated adequate fit of the measurement model (i.e., CFI > .95 and RMSEA < .05). The factor loadings of indicators of social images of exercise and of indicators of obesity were all significant (p < .001). The observed measures of physical activity loaded significantly on the athleticism factor at each time of assessment. For the higher order latent construct of athleticism, the means of both the intercept (Mi = 1.77, t = 100.95, p < .001) and slope (Ms = - .02, t = - 2.13, p < .05) differed significantly from zero, and the variances were significant (Di = .11, t = 6.94, p < .001; Ds = .02, t = 2.76, p < .01). These findings indicate that the latent constructs were all measured satisfactorily, that for the group on average there was a significant decrease in athleticism over the three assessments (negative slope), and that participants varied significantly in their initial levels of athleticism and in their trajectories (slopes) of athleticism over time.

Structural Model

To evaluate the hypothesized relations among the latent constructs, a structural model was tested by adding the following paths to the measurement model: from social image to the intercept and slope of athleticism, and from the intercept and slope of athleticism to T6 obesity. In addition, to control for the effects of T1 grade (age) and T1 BMI, the following structural paths were included: from grade at T1 and from BMI at T1 to the intercept and slope of athleticism, and to obesity at T6. The correlations among BMI at T1, grade at T1 and social image at T1 were also included. The model is shown in Figure 1. The fit indexes were χ2(103, N = 846) = 211.287, p < .001 (CFI = .974, RMSEA = .035, 90% CI = .028, .042) demonstrating adequate fit of the model.

The trajectory of athleticism over 3 years was defined by both the intercept (initial level) and the slope. With regard to the first hypothesis that early social images would predict later athleticism, the findings showed that social images predicted the initial level (i.e., intercept) but not the slope of children’s athleticism. That is, children with more positive images at T1 of kids who exercise had higher levels of athleticism a year later, but social images at T1 were not related to the subsequent rate of decline in children’s athleticism. With regard to the second hypothesis that athleticism would predict subsequent obesity, both the intercept and slope of athleticism predicted obesity at the later time point (T6). That is, higher initial levels of athleticism and less decline in athleticism predicted lower obesity at T6. When the direct path from social images to obesity was tested, either with or without the intervening curve of factors of athleticism, the direct path was not significant, suggesting that early social images do not determine later obesity. Instead, they appear to have an indirect effect on obesity because of their effect on the child’s level of athleticism. Multiple-sample analysis did not identify any differences in the structural paths for girls versus boys.

DISCUSSION

The findings from this study supported the hypothesized cognitive-behavioral mechanism influencing obesity in childhood and adolescence. Controlling for initial BMI, the favorability of social images of children who exercise, assessed as early as the second grade, predicted the initial level of athleticism, and both the level and slope of athleticism predicted obesity 3 years later. The structural model applied equally well to boys and girls, indicating that, regardless of gender, those with more favorable social images earlier in childhood had subsequently higher levels of athleticism, and these children were less likely to become relatively obese.

Consistent with past research, we found that athleticism (measured by self-rated competence and engagement in physical activity) tended to decrease over the three annual assessments. It is particularly interesting to observe a decline over time with relatively young, preteen participants (the sample ranged in mean age from 10.4 at T2 to 12.4 at T4). This finding suggests that interventions to prevent declining physical activity in youth should begin as early as elementary school. The importance of athleticism and engagement in physical activity for obesity prevention was confirmed. Children who described themselves as less athletic initially (intercept) and whose athleticism increased less (and/or declined) over time (slope) had higher scores on the obesity construct (were more obese) subsequently. These findings indicate the importance of both establishing healthful levels of physical activity in late childhood and subsequently maintaining these levels during early adolescence to prevent the development of obesity.

Social images assessed at T1 predicted the level (intercept) but not the slope of athleticism. Social images (prototypes) are part of the relatively recent Prototype/Willingness Model (8-10) and have not yet been extensively studied. Although relatively favorable social images of kids engaging in negative behaviors such as smoking have been shown to predict the child’s own engagement in this behavior (14), there have been few comparable studies of the effects of social images of kids who engage in positive, healthful behaviors. Our study demonstrates that young children’s social images of a positive health behavior (physical activity) can be reliably assessed and that these images are related to their subsequent level of this healthful behavior.

There are several possible explanations for why social images at T1 did not predict the slope of athleticism over time. Social images of kids who exercise, and children’s own engagement in physical activity, may be related bidirectionally, as has been shown for other health cognitions (34). In that case, decreases in athleticism over T2, T3, and T4 would both cause and be caused by decreases in the favorability of social images over the same period. Our findings indicate that whereas early social images are important for establishing initial levels of physical activity, factors other than social images may be important predictors of the subsequent change in physical activity as the child gets older (26). More proximal, contextual factors may be particularly important for predicting the decline in activity in the teenage years when physical activity may no longer be part of the school curriculum and there are increasing demands on teens’ leisure time.

The clinical significance of these findings is twofold. Interventions in the early elementary school grades should be directed at fostering positive social images of children who exercise, resulting in higher levels of physical activity as children enter their preteen years. Subsequently, interventions during early adolescence should be directed toward other more proximal factors, as well as social images, such as ensuring that young adolescents are given dedicated time for exercise and a range of alternative activities to overcome barriers created by lack of self-efficacy (26). Addressing declining levels of physical activity in early adolescence may help to prevent the continuing decline typical of the later teenage years (22).

A limitation of this study was the absence of an objective assessment of body fat, or of objective measures of height and weight from which to compute BMI. However, the sample’s distribution of underweight, normal, at risk for overweight, and overweight based on mothers’ reports of participants’ age- and gender-adjusted BMIs was comparable to national norms. The measure of perceived body shape using figures varying in body fat was one of the three indicators of the latent construct of obesity and was intended to partially offset the limitation of BMI as a measure of body fat. This study also did not include an objective measure of participation in physical activity. Instead, three physical activity indicators were used to represent an athleticism construct that included variables related to engagement in physical activity and beliefs about one’s athletic competence, and all three variables were highly related. These limitations may be offset by several strengths. These include the longitudinal nature of the design permitting prospective associations to be examined between the predictors and outcomes in the model, thus justifying causal inferences; the representative community sample with relatively low attrition; and the assessment of children as young as second grade. The repeated assessment of athleticism enabled the use of a higher order, curve-of-factors LGM. This powerful technique has been rarely used to date, particularly in the study of developmental change in physical activity (26).

This study found support for a childhood cognitive-behavioral mechanism that influences obesity in adolescence. These findings are important for the design of interventions to prevent the development of obesity in youth. They suggest that the processes that lead to youth obesity can be traced back to the early elementary school years when children are developing their beliefs about healthful behaviors. As part of the Prototype/Willingness Model, social images have a strong affective component that accounts for the association between relatively favorable social images of risky behaviors such as smoking with unplanned willingness to engage in such risky behaviors (9). Our study suggests that affect is also an important influence on level of physical activity. Elementary and middle school children’s affective reactions to other children who exercise, in the form of their social images, initiate a pathway in childhood that affects early adolescent physical activity patterns and thus adolescent weight gain. Interventions directed at changing these social images to result in more favorable beliefs may result in children adopting a more healthful path.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant DA 10767 from the National Institute of Drug Abuse.

REFERENCES

- (1).Hedley AA, Ogden CL, Johnson CL, et al. Prevalence of overweight and obesity among US children, adolescents, and adults, 1999-2002. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2004;291:2847–2850. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.23.2847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Whitaker RC, Wright JA, Pepe MS, et al. Predicting obesity in young adulthood from childhood and parental obesity. New England Journal of Medicine. 1997;337:869–873. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199709253371301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Serdul MK, Ivery D, Coates RJ, et al. Do obese children become obese adults? A review of the literature. Preventive Medicine. 1993;22:167–177. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1993.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Power C, Lake JK, Cole TJ. Measurement and long-term health risks of child and adolescent fatness. International Journal of Obesity. 1997;21:507–526. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Hyppönen E, Power C, Davey Smith G. Prenatal growth, BMI, and risk of type 2 diabetes by early midlife. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:2512–2517. doi: 10.2337/diacare.26.9.2512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Edelman B. Developmental differences in the conceptualization of obesity. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 1982;80:122–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Welch C, Gross SM, Bronner Y, et al. Discrepancies in body image perception among fourth-grade public school children from urban, suburban, and rural Maryland. Journal of the American Dietetic Association. 2004;104:1080–1085. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Gibbons FX, Gerrard M. Predicting young adults’ health risk behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;69:505–517. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.69.3.505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Lane DJ. A social reaction model of adolescent health risk. In: Suls JM, Wallston K, editors. The Handbook of Social-Health Psychology. Blackwell; Oxford, England: 2003. pp. 107–136. [Google Scholar]

- (10).Gibbons FX, Gerrard M, Blanton H, Russell DW. Reasoned action and social reaction: Willingness and intention as independent predictors of health risk. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1998;74:1164–1180. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.74.5.1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Slovic P, Peters E, Finucane M, MacGregor DG. Affect, risk, decision making. Health Psychology. 2005;24:S35–S40. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.4.S35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Stock M, Vande-Lune LS, Cleveland MJ. Images of smokers and willingness to smoke among African American pre-adolescents: An application of the prototype/willingness model of adolescent health risk behavior to smoking initiation. Journal of Pediatric Psychology. 2005;30:305–318. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsi026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, et al. Inhibitory effects of drinker and non-drinker prototypes on adolescent alcohol consumption. Health Psychology. 2002;21:601–609. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.21.6.601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Andrews JA, Hampson SE, Barckley M, Gerrard M, Gibbons FX. The effect of early cognitions on cigarette and alcohol use in adolescence. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:288–297. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.22.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Andrews JA, Tildesley E, Hops H, Duncan SC, Severson HH. Elementary school-age children’s future intentions and use of substances. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2003;32:556–567. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3204_8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Andrews JA, Peterson M. The development of social images of substance users in children: A Guttman unidimensional scaling approach. Journal of Substance Abuse. 2006;11:305–321. doi: 10.1080/14659890500419774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M, Severson HH. Personality predictors of the development of elementary-school children’s intentions to drink alcohol: The mediating effects of attitudes and subjective norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. 2006;20:288–297. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.20.3.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hampson SE, Andrews JA, Barckley M. Predictors of development of elementary-school children’s intentions to smoke cigarettes: Prototypes, subjective norms, and hostility. Nicotine and Tobacco Control. 2007;9:751–760. doi: 10.1080/14622200701397908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ouellette JA, Hesslsing R, Gibbons FX, Reis-Bergan M, Gerrard M. Using images to increase exercise behavior: Prototypes versus possible selves. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 2005;31:610–620. doi: 10.1177/0146167204271589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Rivis A, Sheeran P. Social influences and the theory of planned behavior: evidence for a direct relationship between prototypes and young people’s exercise behavior. Psychology and Health. 2003;18:567–583. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Jang EY, Pomery EA, Gibbons FX. Linking health risk and health promotion: A longitudinal study of the relations among risky behavior, health cognitions, body mass index, and depression in American Youth. Unpublished manuscript.

- (22).Sallis JF. Epidemiology of physical activity and fitness in children and adolescents. Clinical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 1993;33:403–408. doi: 10.1080/10408399309527639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Brodersen NH, Steptoe A, Williamson S, Wardle J. Sociodemographic, developmental, environmental, and psychological correlates of physical activity and sedentary behavior at age 11 to 12. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;29:2–11. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2901_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Thompson DR, Obarzanek E, Franko DL, et al. Childhood overweight and cardiovascular disease risk factors: The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Growth and Health Study. Journal of Pediatrics. 2007;150:18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2006.09.039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA. An Introduction to Latent Variable Growth Curve Modeling. 2nd ed. Lawrence Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- (26).Duncan TE, Duncan SC, Strycker LA, Chaumeton NR. A cohort-sequential latent growth model of physical activity from ages 12-17 years. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2007;33:80–89. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3301_9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Santos MP. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors in adolescents. Annals of Behavioral Medicine. 2005;30:21–24. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm3001_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Ogden CL, Fryar CD, Carroll MD, Flegal KM. Advance data from Vital Health and Health Statistics. 347. National Center for Health Statistics; Hyattsville, MD: 2004. Mean body weight, height, and body mass index, United States 1960-2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bhuiyan AR, Gustat J, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Differences in body shape representations among young adults from a biracial (black-white), semirural community: The Bogalusa Heart Study. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2003;158:792–797. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwg218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Muthén BO. Analysis of longitudinal data sets using latent variable models with varying parameters. In: Collins LM, Horn JL, editors. Best Methods for the Analysis of Change: Recent Advances, Unanswered Questions, Future Directions. American Psychological Association; Washington, DC: 1991. pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- (31).McArdle JJ. Dynamic but structural equation modeling of repeated measures data. In: Cattel RB, Nesselroade J, editors. Handbook of Multivariate Experimental Psychology. 2nd ed. Plenum; New York: 1988. pp. 561–614. [Google Scholar]

- (32).Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 3rd ed. Muthén & Muthén; Los Angeles: 19982004. [Google Scholar]

- (33).Enders CK. The performance of the full information maximum likelihood estimator in multiple regression models with missing data. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 2001;61:713–740. [Google Scholar]

- (34).Gerrard M, Gibbons FX, Benthin AC, Hessling RM. A longitudinal study of the reciprocal nature of risk behaviors and cognitions in adolescents: What you do shapes what you think and vice versa. Health Psychology. 1996;15:344–354. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.15.5.344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]