HEALTHY AGING WAS ONCE thought to be a contradiction in terms. Enter James Fries, a professor of medicine at Stanford University School of Medicine. Early in his career, he foresaw a society in which the active and vital years of life would increase in length, the onset of morbidity would be postponed, and the total amount of lifetime disability would decrease. At the heart of his vision is an emphasis on improvements in preventive medicine and the untapped potential of health promotion and prevention.

Known as “compression of morbidity,” Fries’ hypothesis holds that if the age at the onset of the first chronic infirmity can be postponed more rapidly than the age of death, then the lifetime illness burden may be compressed into a shorter period of time nearer to the age of death. Evidence supporting this hypothesis thus must take two forms: first, that it is possible to substantially delay the onset of infirmity; second, that the accompanying increases in longevity will be comparatively modest.1

Think about two points on a typical human lifespan, with the first point representing the time at which a person becomes chronically ill or disabled and the second point representing the time at which that person dies. Today, the time between those two points is about 20 years or so years. During the early portion of those years, chronic disease or disability is minor, but increases nearer to the end of life. The idea behind compression of morbidity is to squeeze or compress the time horizon between the onset of chronic illness or disability and the time in which a person dies.

As Fries, the author of more than 300 articles, numerous book chapters, and 11 books, including Take Care of Yourself and Living Well, explained,2,3

By minimizing the number of years people suffer from chronic illness, we enable older people to live more successful, productive lives that benefit themselves and society. When we consider healthcare reform and new approaches to structuring health care systems, we must recognize that by avoiding long-term periods of morbidity, we reduce healthcare costs and improve the lives of patients at the same time.

Since Fries’ seminal article on his hypothesis was published in The New England Journal of Medicine, compression of morbidity has been intensely discussed and argued for nearly three decades. Today, with data strongly confirming the hypothesis, compression of morbidity has become widely recognized as the dominant paradigm for healthy aging, at both individual and policy levels, and is thought to have laid the foundation for successful health promotion and programs.

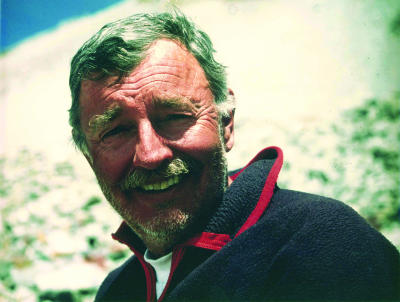

James Fries at Mount Everest Base Camp.

A Philosopher-Cum-Physician

Although Fries is one of the nation’s most well-known and respected rheumatologists and an expert on long-term outcomes, he did not always want to be a physician. Fries studied philosophy as an undergraduate at Stanford. He describes himself as a young man who was very interested in the “great thoughts” on which classical philosophy is based: Why are we here? How do we define the human condition? He surprised himself when he began to find the answers to these questions in the study of medicine. Fries stated,

James Fries and his wife Sarah.

In the course of my studies, I began to believe that the possibility of understanding life through forces of reason and without data had been exhausted. Instead, I began to believe that a greater understanding of life and death would come from the data of biological sciences and, in particular, medicine.

After a brief period as a philosophy instructor at Stanford, Fries headed to Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, where he graduated with a degree in internal medicine and completed a fellowship in rheumatology. Fries explained,

As a field of study and practice, rheumatology was an excellent blend of things I wanted and was interested in. I had the opportunity to watch life course events in patients with rheumatologic disease and the diseases were chronic and intellectually exciting to me. They also involved the art of dealing with the person and the science of projecting long-term outcomes. It was here that I really developed an interest in moving medicine and healthcare in general from short-term outcomes to long-term outcomes.

The Genesis of a New Model

Fries joined the Stanford faculty in 1970. He formulated the compression of morbidity hypothesis during his first sabbatical in 1978 to 1979 at the Center for Advanced Studies and Behavior Sciences, an independent research institution in Stanford, California. Aging was the center’s theme that academic year, and the issues of improving senior capabilities from several perspectives were the focus of the fellows’ discussion.

We entered the twentieth century in an era of acute infectious diseases, with tuberculosis the number one killer of our population and smallpox, diphtheria, tetanus, and other infectious illnesses comprising 80% of all deaths in 1900. With these diseases nearly eradicated by the 1970s, mortality from these diseases have been reduced by nearly 99%, ushering in an era where the major burdens of illness in the United States are chronic diseases—heart disease, stroke, cancer, and diabetes.

As life expectancy steadily rose and patterns of disease experienced a profound shift, the prevailing mythology at the time suggested an unfortunate scenario for future health. As medical progress increasingly prolonged life, those extra months and years would be spent in ill health. This theory, termed “the failure of success,” assumed that although advances in medicine and public health could prolong life, they could not delay the onset of chronic, degenerative diseases.4

“At the time, aging and the field of gerontology in particular, had been described as the science of drawing downwardly sloping lines,” said Fries. “With my contemporaries at the center, who all were very smart and thoughtful people, we came to believe that there was much more that could be done about aging than we had thought.”

Paradigm Shift

The compression of morbidity hypothesis presented a new lens through which to examine aging—a lens that viewed prevention, lifestyle changes, and health improvements as the keys to delaying the onset of morbidity. Fries said,

In contrast to what many demographers and health policy workers of the time believed, the compression of morbidity hypothesis represented a positive concept, with the ideal of a long life with a relatively short period of terminal decline.

“The compression of morbidity was prophetic in the sense that Jim looked at the reduction of morbidity and disability at a time when most gerontologists and epidemiologists thought we would see a pandemic of disability,” said Richard Suzman, director of the Behavioral and Social Research Program at the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health. “It was seminal in the sense that it sparked a lot of research that before did not exist and discussions that before were not taking place.”

Fries himself cited the lack of morbidity data as one of the greatest challenges for others embracing his hypothesis. In fact, the National Long-Term Care Survey was piloted after and, some may argue, in response to Fries’ hypothesis. Naysayers also faulted it for being naively optimistic, whereas others feared it to be a threat to the preparation required to care for growing elderly populations.

On the other side of the spectrum were early adopters of the compression of morbidity hypothesis, including Robert Butler, president and CEO of the International Longevity Center, who described Jim Fries as a “positive force” in aging, and Everett C. Koop, former US surgeon general, who characterized the hypothesis as “ground-breaking” and characterized Fries as “visionary.” Koop said,

Believe it or not, many people who dealt with the elderly at the time did not give much thought to the elderly. The compression of morbidity theory was seen as mind-bending at its debut because it not only changed the way we think about aging, but positioned the issue of aging and the elderly at the center of public health.

“Jim has made a greater contribution than anyone else in the understanding that there is a way to be free of health problems until the very end of life and how important this is in both health care costs and quality of life each of us can enjoy,” said Carson Beadle, chair and co-founder of the Health Project, a White House–endorsed consortium of business, health, and government leaders dedicated to improving health outcomes and reducing demand for medical care.

Proof of Concept

Over the past 20 years, the compression of morbidity hypothesis has generated a tremendous amount of research, including rigorous, longitudinal studies through the Arthritis, Rheumatism and Aging Medical Information System (ARAMIS), a databank established by Fries and funded by the National Institutes of Health as the National Arthritis Data Resource. ARAMIS includes two large longitudinal studies of aging directed at quantification of the compression of morbidity hypothesis to demonstrate the effect of health promotion and prevention in delaying the onset of morbidity.

The first of the studies followed 1700 University of Pennsylvania alumni for 20 years to determine whether people with lower modifiable health risks have more or less cumulative disability. After adjusting for possible confounding variables, they found that the cumulative lifetime disability was four times greater in those who smoked, were obese, and did not exercise than it was in those who did not smoke, were lean, and exercised.5 The onset of measurable disability was postponed by nearly 8 years in the lowest-risk third of the study participants compared with the highest-risk third.

Further support for the compression of morbidity hypothesis came from a second 22-year longitudinal study. Participants were 537 members of a runners’ club and 423 community control participants who on average were 59 years old. They found that the runners developed disability at a rate of only one fourth that of the control participants and were able to postpone disability by more than 12 years over the more sedentary control participants.6

Despite these and other data, however, Fries noted that compression of morbidity cannot be explained by lifestyle factors alone. For example, although there has been a reduction in smoking in the general population of the United States, there has been a simultaneous increase in obesity, and rates of physical activity have remained flat for the past 25 years. According to Fries,

Healthy living and reduction of health risks have played a huge role in the compression of morbidity, but to truly understand the phenomenon we also need to look at other factors, such as joint replacement, statins, better control of diabetes, and other medical innovations introduced in the past few decades that could have contributed to the delay in morbidity. This also suggests that the true promise of health promotion of risk reduction in further compressing morbidity remains unknown.

Looking Forward

Fries, whose colleague Mary Jane England, president of Regis College, described as a “gifted physician dedicated to quality care,” expected the compression of morbidity hypothesis to hold true in the years ahead, as long as society continued to emphasize healthy lifestyles, further improvements in preventive medicine, and a better living environment for the elderly. “We cannot compress morbidity indefinitely, but the paradigm of a long, healthy life with a relatively rapid terminal decline is most certainly an attainable ideal at both a population level and individual level,” said Fries.

Health policies must be directed at modifying those health risks which precede and cause morbidity if compression of morbidity is to be applied to a population. At an individual level, there are three key issues Americans need to pay attention to when it comes to health and postponing morbidity—smoking, obesity, and exercise.

Living by His Word

Although Fries, the father of two children (one deceased) and five grandchildren, maintains that there is no one way to compress morbidity, he suggests everything in moderation, except physical activity, which he stresses as the key to delaying the onset of morbidity. Fries heeds his own advice, having run at least 500 miles each year since 1970. He has also completed the Boston Marathon and is a high-altitude climber who has reached the peak of the tallest summit on six of the seven continents.

According to Beadle,

Whatever Jim undertakes will be done efficiently, effectively and quickly. Jim takes on challenges few others will take, such as climbing Mt. Everest, [participating in] adventure traveling, or horse back riding with his wife, Sarah, in [Botswana’s] Okavango Delta..

Together, Fries and Sarah have led an active life, skiing and adventure traveling the world, from the North Pole to Southeast Asia. Today, Fries is also a caregiver for Sarah, who is a long-term melanoma survivor and living with a disability. Fries said,

I have a surprising amount of satisfaction in helping to care for Sarah, and together we have done many things, especially after her illness, that people said we would not, that people believed were not possible.

In February, Fries and Sarah celebrated the 50th anniversary of their first kiss and have been married nearly as long. “Do I have any words of wisdom? Remember that there is no one magic pathway to living a happy life of longevity and vitality. But there are endless possibilities and we can all have a substantial effect upon our future health,” said Fries.

Human Participant Protection No protocol approval was needed for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Fries JF. Aging, natural death, and the compression of morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1980;303:130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vickery DM, Fries JF. Take Care of Yourself: A Consumer’s Guide to Medical Care. Reading, MA: Perseus Books Publishing Company; 2006.

- 3.Fries JF. Living Well. Reading, MA: Perseus Books Publishing Company; 2004.

- 4.Gruenberg EM. The failure of success. Milbank Mem Fund Q Health Soc. 1977;55:3–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vita AJ, Terry R B, Hubert H B, Fries JF. Aging, health risks, and cumulative disability. N Engl J Med. 1998;338:1035–1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang BW, Ramey DR, Schettler J D, Hubert HB, Fries JF. Postponed development of disability in elderly runners: a 13-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:2285–2294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]