Abstract

By using immunohistochemistry we investigated the expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in 217 early squamous cell cervical carcinomas and examine their prognostic relevance. For EphA2 expression, 21 tumors (10%) showed negative, 108 (50%) weak positive, 69 (32%) moderate positive and 19 (9%) strong positive, whereas for EphrinA-1 expression, 33 tumors (15%) showed negative, 91 (42%) weak positive, 67 (31%) moderate positive and 26 (12%) strong positive. In univariate analysis high expression (strong staining) of EphrinA-1 was associated with poor disease-free (P = 0.033) and disease-specific (P = 0.039) survival. However, in the multivariate analyses neither EphrinA-1 nor EphA2 was significantly associated to survival. The increased levels of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in a relative high number of early stage squamous cell carcinomas suggested that these two proteins may play an important role in the development of a subset of early cervical cancers. However, EphA2 and EphrinA-1 were not independently associated with clinical outcome.

Keywords: Immunohistochemistry, early cervical cancer, EphA2 and EphrinA-1

Introduction

Worldwide, cervical carcinoma is the second most frequent malignancy among women and the death rate is 8 per 100,000 1. Nearly half of patients present with stage I disease and about one third of patients treated with surgery received adjuvant treatment 2. This adjuvant treatment is accompanied by considerable morbidity 3. Therefore, it is important to make individualized treatment procedures in order to reduce negative side effects for patients with a good prognosis. Tumor diameter, pelvic lymph node metastasis, vascular invasion, deep stromal invasion and close resection margins are most often used to target adjuvant treatment to those patients with highest risk of relapse 4-7. New molecular markers that improve the prediction of clinical outcome could be of considerable value to design individualized treatment procedures.

Receptor tyrosine kinases have important roles in the development and progression of human tumors 8. Eph receptors represent the largest known family of receptors tyrosine kinases and are broadly divided into subclasses, EphA and EphB. The EphA receptors (A1-A9) bind to EphrinA ligands, a group of glycosyl phosphatidylinositol-linked membrane proteins and EphB receptors (B1-B6) interact with EphrinB ligands 9. The normal function of EphA2 is not fully understood, but it is thought to function in the regulation of cell growth, angiogenesis, survival and migration 9-11. EphA2 is overexpressed in a variety of human cancers, including breast 12, prostate 13, 14, oesophagus 15, renal 16, lung 17, pancreas 18 and ovarian 19, 20. Furthermore, increase expression of both EphA2 and EphrinA-1 have been observed in vulvar carcinomas 21, cervical carcinomas 22, bladder carcinomas 23, oesophageal carcinomas 24, gastric carcinomas 25 and ovarian carcinomas 26. In various human cancers poor outcome for the patients has been associated with increase expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 16, 17, 19, 24, 26. In our previous study of cervical carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV we found that increase expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was significantly associated with shorter overall survival in multivariate analysis 22. The prognostic significance of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 expression in early stage cervical carcinoma has to our knowledge not been examined.

The aims of our study were to investigate the expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in a series of 217 early squamous cell cervical carcinomas and to identify predictive markers of the clinical outcome for these patients.

Materials and methods

Patient materials

A retrospective study of 217 patients with clinical squamous cervical carcinomas FIGO stage IB, treated by radical hysterectomy and bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy at The Norwegian Radium Hospital in the period January 1987 to December 1993, was performed. The median age at diagnosis was 39 years, ranging from 34 to 51 years. All patients were examined under general anesthesia and tumor diameter was assessed by inspection and palpation. Postoperatively, adjuvant treatment was given in case of large tumor diameter, lymph node metastasis, or invasion into the parametria. A median of 26 lymph nodes were removed. Radiotherapy was given to 32 patients, radiation and chemotherapy to 12, and another 31 received chemotherapy only. All patients were followed until death or July 2001. Forty-four (20.3%) patients suffered a relapse and 37 (17.1%) died of cervical cancer. Median follow-up for patients without relapse was 128 months (range from 112 to 146 months); for patients still alive, median follow-up was 129 months (range from 114 to 147).

Histological specimens were reevaluated blindly by an experienced pathologist (A. K. L.) for histopathological diagnosis according to the World Health Organization 27. Table 1 provides a detailed description of the tumor characteristics. As controls, we used samples of 10 normal cervices from patients who underwent amputation of the cervix for prolapse (age range, 31-49 years, median age 43 years). The Regional Committee for Medical Research Ethics South of Norway (S-06381a), The Social- and Health Directorate (06/4509 and 06/4417) and The Data Inspectorate (06/01467-3) approved the study.

Table 1.

Ephrin A-1 and EphA2 immunostaining in relation to clinicopathological variables.

| Variables | Total | EphA2* | Ephrin A-1* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Low | High (%) | p‡ | Low | High (%) | p‡ | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 0.812 | 0.442 | |||||

| < 2 | 97 | 88 | 9 (9) | 85 | 12 (12) | ||

| 2.0 – 3.9 | 86 | 78 | 8 (9) | 78 | 8 (9) | ||

| ≥ 4 | 34 | 32 | 2 (6) | 28 | 6 (18) | ||

| Depth of invasion (mm) | 0.236 | 0.005 | |||||

| ≤ 10 | 122 | 113 | 9 (7) | 111 | 11 (9) | ||

| 11-15 | 48 | 45 | 3 (6) | 45 | 3 (6) | ||

| > 15 | 47 | 40 | 7 (15) | 35 | 12 (25) | ||

| Vascular invasion | 0.716 | 0.669 | |||||

| Absent | 117 | 106 | 11 (9) | 104 | 13 (11) | ||

| Present | 100 | 92 | 8 (8) | 87 | 13 (13) | ||

| Parametrial invasion | 0.011 | <0.001 | |||||

| Absent | 202 | 187 | 15 (7) | 183 | 19 (9) | ||

| Present | 15 | 11 | 4 (27) | 8 | 7 (47) | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | 0.680 | 0.298 | |||||

| Absent | 175 | 159 | 16 (9) | 156 | 19 (11) | ||

| Present | 42 | 39 | 3 (7) | 35 | 7 (17) | ||

Numbers in parentheses are percentages.

*Low: Negative/weak/moderate staining; High: Strong staining.

‡Pearson chi-square.

Immunostaining method

Sections were immunostained using the Dako EnVisionTM + System, Peroxidase (DAB) (K4011, Dako Corporation, CA, U. S.A.) and Dakoautostainer. After microwaving in 10 mM citrate buffer pH 6.0 to unmask the epitopes the sections were treated with 0.03% hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) for 5 minutes to block endogenous peroxidase. Polyclonal rabbit antibodies EphA2 (sc-924, 1:400, 0.5μg IgG/ml) and EphrinA-1 (sc-911, 1:300, 0.7 μg IgG/ml) both from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., CA, U.S.A. were applied on the sections for 30 minutes at room temperature followed by incubation with peroxidase labeled polymer conjugated to goat anti-rabbit for 30 minutes. The peroxidase reaction was developed using 3`3‑diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (DAB) as chromogen. Human cervical carcinomas that had been shown to express EphA2 and EphrinA-1 have been included in all series as positive controls. Negative controls included substitution of the polyclonal antibody with normal rabbit IgG of the same concentration as the polyclonal antibody. All controls gave satisfactory results. The specificity of anti-EphA2 and anti-EphrinA-1 has been tested previously 26. Cytoplasmic staining was considered positive. Four semiquantitative classes were used to describe the intensity of staining; no staining, weak staining, moderate staining and strong staining. Since tumor cells stained uniformly across the samples we did not considered the fraction of tumor cells with positive staining. Sections were scored by two independent observers (R. H. and Z. S.) without knowledge of clinical data. Conflicting results were reviewed until final agreement was achieved. Based on our previous published study of cervical carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV two different cutoffs were used 22. EphA2 and EphrinA-1 expression were defined as high when strong staining was seen in the tumor cells or, alternatively, when strong/moderate staining was identified.

Statistical analyses

Pearson chi-square test with the Yates continuity correction for 2 x 2 tables or Fisher`s Exact test were used to test the association between the expressed proteins and between protein expression and clinicopathological parameters. Using the method described by Kaplan and Meier, disease-free and disease-specific survival curves were obtained from date of diagnosis to relapse or death, respectively, or to July 17, 2001. The log rank test with a test for trend in case of ordered variables was used for univariate and a Cox proportional hazards regression model was used for multivariate analysis of survival. In multivariate analysis, a backward stepwise regression with a P < 0.1 in the univariate analysis as the inclusion criterion was used. The hazard proportionality was verified by computing the log minus log against time. All calculations were performed using the SPSS 15.0 statistical software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL). Statistical significance was considered as P < 0.05.

Results

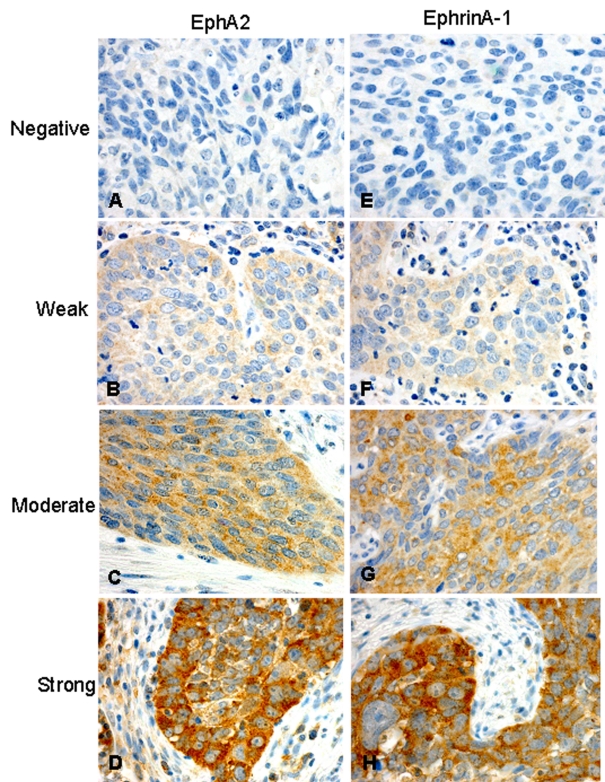

In normal squamous epithelium weak cytoplasmic staining for EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was present in 4/10 (40%) and 6/10 (60%) of the cases, respectively. EphA2 and EphrinA-1 staining were seen in basal, parabasal and middle layers. For EphA2 cytoplasmic expression was observed in 196/217 (90%) of the cervical cancers, whereas, for EphrinA-1 cytoplasmic expression was seen in 184/217 (85 %) of the cases (Table 2, Figure 1).

Table 2.

Immunostaining results for EphA2 and Ephrin A-1.

| Staining intensity | Number of cases | |

|---|---|---|

| EphA2 (%) | Ephrin A-1 (%) | |

| Negative | 21 (10) | 33 (15) |

| Weak | 108 (50) | 91 (42) |

| Moderate | 69 (32) | 67 (31) |

| Strong | 19 (9) | 26 (12) |

Figure 1.

Immunohistochemical analysis for EphA2 (A-D) and EphrinA-1 (E-H) showing cases with no staining (A, E), weak staining (B, F), moderate staining (C, G) and strong staining (D, H).

In previous reports 28, 29 protein expression of p27, p21, p16, cyclin A, cyclin E and cyclin D3 were studied with immunohistochemistry in the same patient populations. We therefore make a comparison between these proteins and EphA2 and EphrinA-1. There was a clear correlation between expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 (P < 0.0001). No other significant relationship concerning protein levels was found (Table 3).

Table 3.

Correlations.

| Variables | EphrinA-1 | EphA2 | p27† | p21† | p16† | Cyclin A† | Cyclin E† | Cyclin D3† |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EphrinA-1 | 1 | <0.0001* | 0.883 | 0.581 | 0.449 | 0.160 | 0.943 | 0.695 |

| EphA2 | 1 | 0.497 | 0.825 | 0.152 | 0.883 | 0.944 | 0.771 |

*Correlation is significant at 0.01 level.

†Anti-p27 (Transduction Laboratories, Lexington, USA), anti-p21 (Oncogene Science, MA, USA), anti-p16 (Neomarkers, CA, USA), anti-cyclin A and anti-cyclin E (both from Novocastra Laboratories, Newcastle, UK) and anti-cyclin D3 (Dako, Glostrup, Denmark). Protein levels were defined as high when ≥5% of tumor cells were positive for p21, cyclin E and cyclin D3 and ≥50% of tumor cells were positive for p27, p16 and cyclin A 28, 29.

High EphA2 expression (strong staining) was significantly correlated to the present of parametrial invasion (P = 0.011). There was a clear correlation between high EphrinA-1 expression (strong staining) and deep invasion (P = 0.005) and presence of parametrial invasion (P < 0.001) (Table 1). Furthermore, there was a significant association between high EphrinA-1 and large tumor size (P = 0.043) when grouping the staining pattern moderate/strong staining as high.

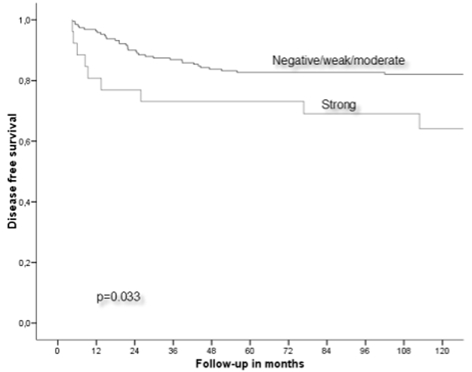

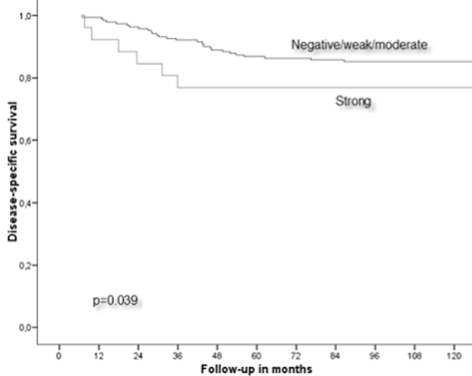

In the univariate analysis high expression of EphrinA-1 (strong staining) was associated with poor disease-free (P = 0.033) (Figure 2) and disease-specific (P = 0.039) survival (Figure 3, Table 4). No significant correlation was obtained when using strong/moderate staining as cutoff for EphrinA-1 or strong and strong/moderate staining as cutoff for EphA2 expression. In the multivariate analyses EphrinA-1 was not an independent prognostic factor for disease-free (P = 0.139) and disease-specific (P = 0.222) survival.

Figure 2.

Disease-free survival in relation to EphrinA-1 expression.

Figure 3.

Disease-specific survival in relation to EphrinA-1 expression.

Table 4.

5-years disease-free and disease-specific survival.

| Variables | Total | Relapses N=44 | DFS* (%) | P | Deaths N=37 | DSS† (%) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EphA2 | 0.547 | 0.748 | |||||

| Low (negative/weak/moderate) | 198 | 39 | 81 | 33 | 85 | ||

| High (strong) | 19 | 5 | 84 | 4 | 89 | ||

| EphrinA-1 | 0.033 | 0.039 | |||||

| Low (negative/weak/moderate) | 191 | 35 | 83 | 29 | 87 | ||

| High (strong) | 26 | 9 | 73 | 8 | 77 |

*Disease-free survival.

†Disease-specific survival.

Discussion

In the present work, weak immunostaining for EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was present in 40% and 60% of normal squamous epithelium, respectively. The positive overall staining (weak/moderate/strong) of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was observed in 90% and 85% of squamous cell cervical carcinomas FIGO stage IB, respectively. This is in line with our previous study identifying EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in 88% and 92% of squamous cell cervical carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV, respectively 22. Furthermore, high expression (moderate/strong staining) for EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was found in 41% and 43% of the cases, respectively. Previously, a wide range of EphA2 overexpression (34-87%) 15, 17, 19, 22, 24-26 and EphrinA-1 overexpression (41-61%) 22, 24, 26 has been reported in many other human cancer types FIGO stage I-IV, including squamous cell cervical carcinomas were 43% and 46% of the cases overexpressed EphA2 and EphrinA-1, respectively 22. The increased levels of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in a relative high number of early stage squamous cell carcinomas suggested that these two proteins may be important factors in the development of a subset of early cervical cancers. This is in agreement with the study of Zheng and coworkers 14 where EphA2 protein was suggested to play an important role in the early stage of prostate carcinogenesis.

Our findings that EphrinA-1 overexpression tended to be associated with large tumor size and deep invasion are consistent with a recent report by Holm et al. 21 in vulvar carcinoma. However, in oesophagus cancer 24 and gastric cancer 25 EphrinA-1 expression did not correlate with tumor size.

Increased expression of EphA2 was not of prognostic significance, whereas overexpression of EphrinA-1 (strong staining) was associated with poor survival in squamous cell cervical carcinomas FIGO stage IB in univariate analysis. However, EphrinA-1 overexpression was not significantly associated with reduced survival when multivariate analysis was applied. Contrary, in our previous study of squamous cell cervical carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV we found that increased expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 was significantly associated with shorter overall survival in multivariate analysis 22. This discrepancy could not be explained by use of different conditions, because in these two studies primary antibodies, detection system, pretreatment and other technical aspects as well as evaluation and cutoffs of immunohistochemical results were exactly the same. Therefore, our results may indicate that EphA2 and EphrinA-1 could be used as an independent prognostic factor in squamous cell cervical carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV 22, but not when only evaluating early squamous cell cervical carcinomas. In other human cancers FIGO stage I-IV, high EphA2 15 and EphrinA-1 21, 24, 30 expressions have been correlated with short survival in univariate analysis, but not in multivariate analysis. Furthermore, a high EphA2 level has been correlated with poor survival in univariate analysis as well as in multivariate analysis in patients with ovarian carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV 19, 26 and oesophagus carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV 24. In contrast, neither EphrinA-1 nor EphA2 was associated with survival in patients with carcinomas FIGO stage I-IV of ovarian 26 and vulvar 21, respectively. Taken together, these studies showed that the prognostic significance of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in different human cancers is conflicting and no clear picture can be drawn.

Previously, EphA2 and EphrinA-1 have been found to be regulated by p53, p63 and p73 in non-small cell lung carcinoma cell line and breast adenocarcinoma cell line 31. In contrast, there was no correlation between EphA2 or EphrinA-1 and p53 in vulvar cancer 21. However, EphA2 overexpression has been found to be associated with high cyclin A level, whereas, increase expression of EphrinA-1 correlated with high cyclin A and p21 levels in vulvar cancer 21. We did not identify any correlation between EphA2 or EphrinA-1 and the cell cycle proteins p21, p27, p16, cyclin A, cyclin E and cyclin D3 in early squamous cell cervical carcinomas. These studies may indicate that the mechanisms of expression EphA2 and EphrinA-1 are different in various types of cancers.

In conclusion, the increased levels of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in a relative high number of early stage squamous cell carcinomas suggested that these two proteins may play an important role in the development of a subset of early cervical cancers. However, EphA2 and EphrinA-1 were not independently associated with clinical outcome.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mai Thi Phuong Nguyen, Liv Inger Håseth and Ellen Hellesylt for excellent technical assistance. This study was supported in part by grant from the Norwegian Cancer Society.

References

- 1.Globocan 2000. Cancer Incidence, Mortality and Prevalence Worldwide; IARC CancerBase No 5(Version 1-0) Lyon, France: IARCPress; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benedet JL, Odicino F, Maisonneuve P et al. Carcinoma of the cervix uteri. J Epidemiol Biostat. 2001;6:7–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Landoni F, Maneo A, Colombo A et al. Randomised study of radical surgery versus radiotherapy for stage Ib-IIa cervical cancer. Lancet. 1997;350:535–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)02250-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Delgado G, Bundy BN, Fowler WCJr et al. A prospective surgical pathological study of stage I squamous carcinoma of the cervix: a Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Gynecol Oncol. 1989;35:314–20. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(89)90070-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Inoue T, Okumura M. Prognostic significance of parametrial extension in patients with cervical carcinoma Stages IB, IIA, and IIB. A study of 628 cases treated by radical hysterectomy and lymphadenectomy with or without postoperative irradiation. Cancer. 1984;54:1714–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19841015)54:8<1714::aid-cncr2820540838>3.0.co;2-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kamura T, Tsukamoto N, Tsuruchi N et al. Multivariate analysis of the histopathologic prognostic factors of cervical cancer in patients undergoing radical hysterectomy. Cancer. 1992;69:181–6. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19920101)69:1<181::aid-cncr2820690130>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sevin BU, Nadji M, Lampe B et al. Prognostic factors of early stage cervical cancer treated by radical hysterectomy. Cancer. 1995;76:1978–86. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19951115)76:10+<1978::aid-cncr2820761313>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nakamoto M, Bergemann AD. Diverse roles for the Eph family of receptor tyrosine kinases in carcinogenesis. Microsc Res Tech. 2002;59:58–67. doi: 10.1002/jemt.10177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang J, Hughes S. Role of the ephrin and Eph receptor tyrosine kinase families in angiogenesis and development of the cardiovascular system. J Pathol. 2006;208:453–61. doi: 10.1002/path.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andres AC, Reid HH, Zurcher G et al. Expression of two novel eph-related receptor protein tyrosine kinases in mammary gland development and carcinogenesis. Oncogene. 1994;9:1461–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holder N, Klein R. Eph receptors and ephrins: effectors of morphogenesis. Development. 1999;126:2033–44. doi: 10.1242/dev.126.10.2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zelinski DP, Zantek ND, Stewart JC et al. EphA2 overexpression causes tumorigenesis of mammary epithelial cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:2301–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker-Daniels J, Coffman K, Azimi M et al. Overexpression of the EphA2 tyrosine kinase in prostate cancer. Prostate. 1999;41:275–80. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19991201)41:4<275::aid-pros8>3.0.co;2-t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeng G, Hu Z, Kinch MS et al. High-level expression of EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase in prostatic intraepithelial neoplasia. Am J Pathol. 2003;163:2271–6. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63584-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miyazaki T, Kato H, Fukuchi M et al. EphA2 overexpression correlates with poor prognosis in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;103:657–63. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Herrem CJ, Tatsumi T, Olson KS et al. Expression of EphA2 is prognostic of disease-free interval and overall survival in surgically treated patients with renal cell carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:226–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kinch MS, Moore MB, Harpole DHJr. Predictive value of the EphA2 receptor tyrosine kinase in lung cancer recurrence and survival. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:613–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mudali SV, Fu B, Lakkur SS et al. Patterns of EphA2 protein expression in primary and metastatic pancreatic carcinoma and correlation with genetic status. Clin Exp Metastasis. 2006;23:357–65. doi: 10.1007/s10585-006-9045-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thaker PH, Deavers M, Celestino J et al. EphA2 expression is associated with aggressive features in ovarian carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:5145–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-03-0589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin YG, Han LY, Kamat AA et al. EphA2 overexpression is associated with angiogenesis in ovarian cancer. Cancer. 2007;109:332–40. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holm R, Knopp S, Suo Z et al. Expression of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in vulvar carcinomas and its relation to prognosis. J Clin Pathol. 2007;60:1086–91. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2006.041194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu D, Suo Z, Kristensen GB et al. Prognostic value of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 in squamous cell cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;94:312–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.05.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abraham S, Knapp DW, Cheng L et al. Expression of EphA2 and Ephrin A-1 in carcinoma of the urinary bladder. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:353–60. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu F, Zhong W, Li J et al. Predictive value of EphA2 and EphrinA-1 expression in oesophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Anticancer Res. 2005;25:2943–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura R, Kataoka H, Sato N et al. EPHA2/EFNA1 expression in human gastric cancer. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:42–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00007.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Han L, Dong Z, Qiao Y et al. The clinical significance of EphA2 and Ephrin A-1 in epithelial ovarian carcinomas. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;99:278–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Poulsen HE, Taylor CW, Sobin LH. Histological typing of female genital tract tumours. Geneva: World Health Organization; 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van de Putte G, Holm R, Lie AK et al. Expression of p27, p21, and p16 protein in early squamous cervical cancer and its relation to prognosis. Gynecol Oncol. 2003;89:140–7. doi: 10.1016/s0090-8258(03)00010-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Van de Putte G, Kristensen GB, Lie AK et al. Cyclins and proliferation markers in early squamous cervical carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2004;92:40–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2003.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Herath NI, Spanevello MD, Sabesan S et al. Over-expression of Eph and ephrin genes in advanced ovarian cancer: ephrin gene expression correlates with shortened survival. BMC Cancer. 2006;6:144. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dohn M, Jiang J, Chen X. Receptor tyrosine kinase EphA2 is regulated by p53-family proteins and induces apoptosis. Oncogene. 2001;20:6503–15. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]