Abstract

Folate receptors (FRs) have been identified as cellular surface markers for cancer and leukemia. Liposomes containing lipophilic derivatives of folate have been shown to effectively target FR-expressing cells. Here, we report the synthesis of a novel lipophilic folate derivative, folate-polyethylene glycol-cholesterol hemisuccinate (F-PEG-CHEMS), and its evaluation as a targeting ligand for liposomal doxorubicin (L-DOX) in FR-expressing cells. Liposomes containing F-PEG-CHEMS, with a mean diameter of 120±20nm, were synthesized by polycarbonate membrane extrusion and were shown to have excellent colloidal stability. The liposomes were taken up selectively by KB cells, which overexpress FR-α. Compared to folate-PEG-cholesterol (F-PEG-Chol), which contains a carbamate linkage, F-PEG-CHEMS better retained its FR-targeting activity during prolonged storage. In addition, F-PEG-CHEMS containing liposomes loaded with DOX (F-L-DOX) showed greater cytotoxicity (IC50=10.0μM) than non-targeted control L-DOX (IC50 = 57.5μM) in KB cells. In ICR mice, both targeted and non-targeted liposomes exhibited long circulation properties, although F–L-DOX (t1/2 = 12.34 hr) showed more rapid plasma clearance than L-DOX (t1/2 = 17.10 hr). These results suggest that F-PEG-CHEMS is effective as a novel ligand for the synthesis of FR-targeted liposomes.

Keywords: liposomes, targeted drug delivery, folate receptor, nanotechnology, doxorubicin, cancer

1. Introdution

Liposomes, or phospholipid bilayer vesicles, have been investigated as potential drug delivery vehicles. Compared to free drugs, liposomal drugs typically exhibit prolonged systemic circulation time and increased tumor localization as a result of the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect. Systemic clearance of liposomes is mediated by phagocytic cells of the reticuloendothelial system (RES) (Banerjee at al., 2001; Momot et al., 2003; Papahadjopoulos et al., 1991) and is facilitated by plasma protein opsonization. Incorporation of polyethylene glycol (PEG) coating on liposomes has been shown to reduce the rate of RES clearance of liposomes (Allen et al., 1991; Fritze et al., 2006; Momot et al., 2003; Papahadjopoulos et al., 1991). Liposomal delivery has been shown to reduce cardiac toxicity of doxorubicin (Perez et al., 2002). Targeted liposomes can be synthesized by incorporating a tumor cell-selective ligand, such as antibodies, transferrin and folic acid (Gabizon et al., 2004; Lukyanov et al., 2004; Pan et al. 2007; Wu et al., 2006a; Xiong et al., 2005), via a lipophilic anchor, typically consisting of a derivative of distearoylphosphatidylethanolamine (DSPE).

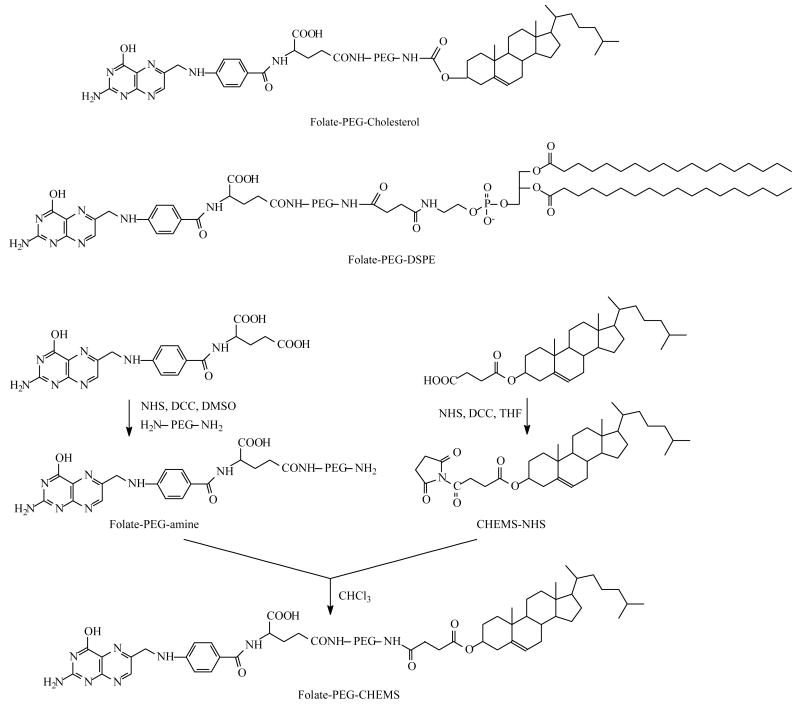

Membrane folate receptors (FRs), including FR-α and FR-β, are glycosylphosphatidylinositol (GPI)-anchored glycoproteins. FR-α expression is amplified in over 90% of ovarian carcinomas and at varying frequencies in other epithelial cancers. Meanwhile, FR-β is expressed in a non-functional form in neutrophils and in a functional form in activated macrophages and in myeloid leukemias (Elwood et al., 1989; McHugh et al., 1979). In contrast, most normal tissues lack expression of either FR isoform. Folic acid (folate) is a high affinity ligand for the FRs that retains high FR affinity upon derivatization via one of its carboxyl group. Due to its small size and ready availability, folate has become one of the most investigated targeting ligands for tumor-specific drug delivery(Curiel et al., 1999; Gabizon et al., 2004; Hilgenbrink et al., 2005; Ke et al., 2003; Kim et al., 2007; Leamon et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2006). Folate has been incorporated into liposomes via conjugation to lipophilic anchors. Folate-conjugated liposomes have been evaluated for targeted delivery of a broad range of therapeutic agents (Gabizon et al., 2006; Hattori et al., 2005; Pan et al., 2007; Thirumamagal et al., 2006; Wu et al., 2006b). Lee and Low were the first to report the synthesis of folate-conjugated liposomes. They have shown that a lengthy spacer, based on PEG, was required between folate and the lipid anchor to enable effective FR-mediated tumor cell targeting of the liposomes. Two lipophilic derivatives have since been synthesized for liposome targeting: folate-PEG-DSPE (F-PEG-DSPE) and folate-PEG-cholesterol (F-PEG-Chol) (Fig. 1) (Gabizon et al., 2003, 2004; Goren et al., 2000; Guo et al. 2000; Lee et al., 1995; Wu et al., 2006a). Although these folate conjugates have been shown to be effective in targeting FR-expressing tumor cells, there are concerns over the two negative charges carried by F-PEG-DSPE and the use of a carbamate linker in F-PEG-Chol, which has limited hydrolytic stability.

Fig. 1.

Structures of F-PEG-DSPE, F-PEG-Chol and the Synthesis Route of F-PEG-CHEMS

In the present study, we report the synthesis a novel lipophilic folate derivative, folate-PEG-cholesteryl hemisuccinate (F-PEG-CHEMS), which is based on amide and ester linkages. FR-targeted liposomes were synthesized using this novel derivative and characterized for stability, FR-dependent cellular uptake, cytotoxity and for pharmacokinetic properties.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Materials

Folic acid, N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS), dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC), triethylamine, polyoxyethylene bis-amine (M.W., 3,350, NH2-PEG-NH2), cholesteryl hemisuccinate (CHEMS), cholesterol (CHOL), doxorubicin hydrochloride (DOX·HCl), 3-(4,5-dimethyl-2-thiazolyl)-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT), calcein, doxorubicin (DOX), and Sepharose CL-4B chromatography media were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich Chemical Co (St. Louis, MO). Monomethoxy polyethylene glycol 2000-distearoyl phosphatidylethanolamine (mPEG-DSPE) was purchased from Genzyme Pharmaceuticals (Liestal, Switzerland). PD-10 desalting columns were purchased from Amersham Biosciences (Uppsala, Sweden). Hydrogenated soybean phosphatidylcholine (HSPC) was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids Inc. (Alabaster, AL). All reagents and solvents were of analytical or HPLC grade and were used without further purification.

2.2 Cell culture

Human oral cancer KB cell line, which later has been identified as being derived from the human cervical cancer HeLa cell line, was obtained as a gift from Dr. Philip S. Low (Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN). KB cells were cultured as a monolayer in folate-free RPMI 1640 media (Life Technologies Inc., Bethesda, MD) supplemented with penicillin, streptomycin, and 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and in a humidified atmosphere containing 5% CO2 at 37°C.

2.3 Synthesis of F-PEG-CHEMS

The synthesis was carried out as shown in Fig. 1. First, folate-PEG-amine and CHEMS-NHS were synthesized by methods described previously by Wu et al. (Wu et al., 2006a) and Kempen et al (Kempen et al., 1988)., respectively. This was followed by the synthesis of F-PEG-CHEMS by reacting folate-PEG-amine with CHEMS-NHS. Briefly, for synthesis of folate-PEG-bis-amine, folic acid (26.5 mg) and PEG-bis-amine (167.5 mg) were dissolved in 1 mL DMSO. Then, 8.6 mg of NHS and 15.5 mg of DCC were added to the solution and the reaction was allowed to proceed overnight at room temperature. The product, folate-PEG-amine was then purified by Sephadex G-25 gel-filtration chromatography. For synthesis of CHEMS-NHS, CHEMS (1g) was reacted with 475 mg NHS and 1.25g DCC in tetrahydrofuran overnight at room temperature. The product CHEMS-NHS was purified by recrystalization. Finally, for synthesis of F-PEG-CHEMS, folate-PEG-amine (137mg, 40μmol) and CHEMS-NHS (29.2mg, 50μmol) were dissolved in CHCl3 (50mL), and reacted overnight at room temperature. The solvent (CHCl3) was then removed by rotary evaporation and the residue was hydrated in 50mM Na2CO3 (10mL) to form F-PEG-CHEMS micelles. The micelles were then dialyzed against deionized water using a Spectrum dialysis membrane with a molecular weight cut-off (MWCO) of 14 kDa to remove low molecular weight by-products. The product F-PEG-CHEMS was then dried by lyophilization, which yielded a yellow powder product (130mg) with a yield of 76.5%. The identity of the product was confirmed by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) and by 1H NMR in d-DMSO.

2.4 Liposome preparation

Liposomes were prepared by thin film hydration followed by polycarbonate membrane extrusion, as described previously (Haran et al., 1993; Pan et al., 2002). DOX was remote-loaded into the liposomes by a transmembrane pH gradient. The lipid compositions of the non-targeted liposomes and the FR-targeted liposomes were HSPC/CHOL/mPEG-DSPE at molar ratio of 55:40:5, and HSPC/CHOL/mPEG-DSPE/F-PEG-CHEMS at molar ratio of 55:40:4.5:0.5, respectively. Briefly, the lipids (85 mg total) were dissolved in CHCl3 and dried into a thin film by rotary evaporation and then further dried under vacuum. The lipid film was hydrated with 2 mL of 250mM ammonium sulfate ((NH4)2SO4) for 30 min at 60°C with occasional vortex mixing. The suspension of lipids were then extruded 5 times through a 0.1 μm pore-size polycarbonate membranes using a Lipex Extruder (Northern Lipids Inc., Vancouver, BC, Canada) driven by pressurized nitrogen at 60°C to produce unilamellar vesicles. The (NH4)2SO4 outside of the liposomes was removed by tangential flow diafiltration against phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH7.4) using a Millipore Pellicon XL cartridge with a MWCO of 30 kDa. The mean diameter of the liposomes was determined by dynamic light scattering using NICOMP Model 370 Submicron Particle Size (Particle Sizing Systems, Santa Barbara, CA). DOX·HCl (4 mg) was dissolved in 0.4 mL deionized H2O and added to the liposomes at a DOX-to-lipid ratio of 1:20 (w/w), followed by a 30-min incubation at 65°C. Residual free DOX in the liposomal preparation was removed by size exclusion chromatography on a Sepharose CL-4B column. DOX concentration in the liposomes was determined by measuring absorption at 480 nm on a Shimadzu UV-Vis spectrophotometer following liposome lysis in ethanol. Drug encapsulation efficiency was determined by running samples through a Sepharose CL-4B column, and calculated by the equation:

The zeta potential of the liposomes was measured by Zeta PALS (Zeta Potential Analyzer, Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, NY). Fluorescent liposomes were prepared by the above described procedures except that the lipid film was hydrated in 50mM calcein instead of the (NH4)2SO4 solution.

2.5 Uptake of FR-targeted liposomes by KB cells

KB cells grown in a monolayer were suspended by brief treatment with trypsin, and then were washed 3 times with folate free RPMI 1640 medium. Aliquots of KB cell suspension were incubated with non-targeted liposomal calcein (L-calcein) or FR-targeted liposomal calcein (F-L-calcein) for 1h at 37°C. To determine the role of FR binding, 1 mM free folate was added to the incubation media in the FR blocking group. After incubation, the cells were washed three times with cold PBS to removed unbound liposomes. An aliquot of the cells were taken to be either examined on a Nikon Eclipse 800 fluorescence microscope or analyzed by flow cytometry on a Beckman-Coulter EPICS XL cytometer (Beckmann-Coulter, Miami, FL), the rest of the cells were lysed in 0.5mL PBS containing 1% Triton X-100, the fluorescence intensity of the cellular lysate were measured at 495 nm excitation and 520nm emission.

2.6 Cytotoxicity analyses

Cytotoxicity of liposomes was determined by the MTT assay, as described previously(Lee et al., 1995). KB cells grown in folate-free RPMI 1640 medium were seeded in 96-well tissue culture plates at 5×103 cells per well, cultured for 24 h, and then incubated with 200 μL medium containing serial dilutions of drug formulations, including free DOX, liposomal DOX (L-DOX), and liposomal DOX containing F-PEG-CHEMS (F-L-DOX) with or without 1 mM free folate. After 2 h incubation at 37°C, the cells were washed twice and cultured in fresh RPMI-1640 medium for an additional 72h. Then, 10 μL MTT (5mg/mL) was added to each well and the plates were incubated for another 4h at 37°C. Medium was then removed and replaced with 200μL DMSO to dissolve the blue formazan crystals converted from MTT by live cells. The plates were then read on a Biorad Model 450 microplate reader and the cell viability was determined from absorbance at 570nm.

2.7 Pharmacokinetic studies

Female ICR mice (20g, 6-8 weeks old) were purchased from Charles River Laboratories (Wilmington, MA, USA). Mice (3 per group) were given intravenous injection of different formulations of liposomes at the drug dose of 5 mg/kg via the tail vein. Blood samples were collected in heparin-treated tubes at various time points. Plasma was isolated by centrifugation (5min, at 3000×g). Two hundred μL aliquots of plasma were diluted with deionized water to 500 μL, followed by addition of 50 μL 20% sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS). Two mL of ethanol was then added followed by 30 s vortex mixing and centrifugation to extract DOX from the liposomes. DOX extraction efficiency for the assay was determined to be 91.5%. DOX concentration in the lysate was measured by its fluorescence, as described above. Pharmacokinetic parameters were determined using the WinNonlin software, including area under the curve (AUC), mean residence time (MRT), total body clearance (CL), and plasma half-lives for the elimination phase (t1/2β).

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Synthesis of F-PEG-CHEMS

F-PEG-CHEMS was synthesized, as described in Materials and Methods and illustrated in Fig. 1. The product F-PEG-CHEMS was suspended as micelles in 50mM Na2CO3, and then the low molecular weight by-products and unreacted materials were removed by dialysis against deionized water. The formation of the product was confirmed by TLC (mobile phase: CH2Cl2/methanol at 70:30 plus trace amount of acetic acid). F-PEG-CHEMS had an Rf value of 0.5. 1H-NMR analysis showed principal peaks (in ppm) related to the folate moiety [8.14(d), 7.64(d), 6.94(t), 6.63(d), 4.48(d), 4.32(m)], the PEG moiety [3.65(m)], and the CHEMS moiety [5.37(bd), 4.65(m), 2.31-0.68(m)].

3.2 Synthesis and Characterization of Liposomes

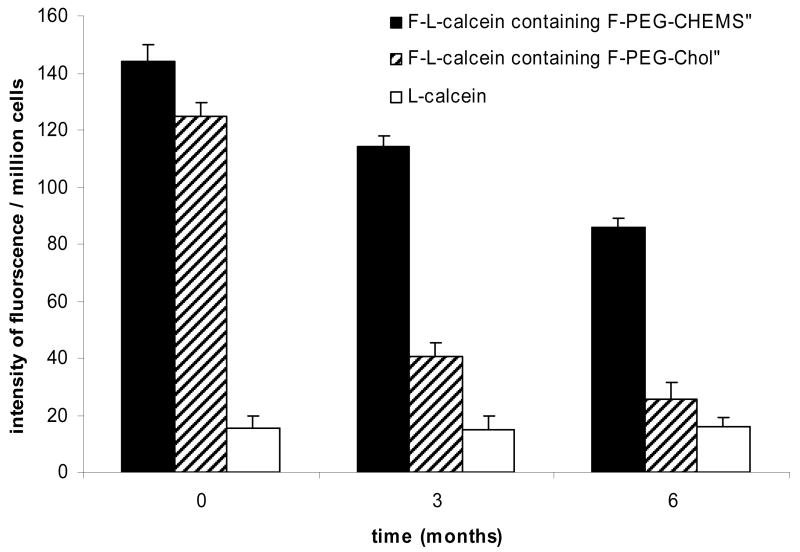

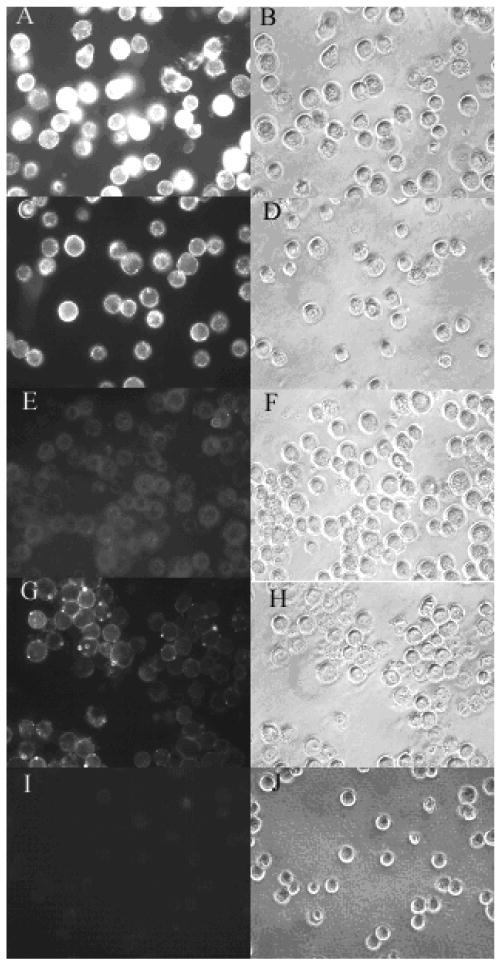

Liposomes were prepared by thin film hydration followed by high pressure extrusion, as described in Materials and Methods. In a typical preparation, the liposomes had a mean diameter of ∼120 nm and relatively narrow distribution (standard deviation <30% of the mean). Efficiency for remote loading of DOX into liposomes was >95% at the drug/lipid ratio of 1:20 (w/w). The zeta potentials of L-DOX and F-L-DOX were -21.87±1.94 mV and -11.82±11.72 mV, respectively. The negative zeta potentials might be due to the presence of the negatively charged lipid mPEG-DSPE in the formulation, as reported previously(Hinrichs et al., 2006). The liposomes showed good stability when stored at 4°C. After 6 months in storage, the mean particle size increased from 117nm to 134nm and DOX release from the liposomes was less than 10%. Importantly, liposomes containing F-PEG-CHEMS retained efficiency in targeting FR-positive KB cells after prolonged storage at 4 °C as shown in Fig. 2 & 3. In contrast, liposomes containing F-PEG-Chol, which contains a carbamate bond between the PEG and cholesterol moieties, lost their FR-targeting activity after 3-month storage (Fig. 2 & 3). These data suggest F-PEG-CHEMS has greater stability than F-PEG-Chol.

Fig. 2.

Uptake of F-L-calcein and L-calcein by KB cells. KB cells were treated with F-L-calcein, F-L-calcein plus 1 mM of free folic acid or L-calcein. Right panels indicate cells visualized in the fluorescence mode; left panels indicate the same fields in the phase-contrast mode. Panels A and B, cells treated with F-L-calcein containing F-PEG-CHEMS; panels C and D, cells treated with F-L-calcein containing F-PEG-CHEMS after storage at 4 °C for 3 months; panels E and F, cells treated with F-L-calcein containing F-PEG-Chol after storage at 4 °C for 3 months; panels G and H, cells treated with F-L-calcein containing F-PEG-CHEMS plus 1mM free folate; panels I and J, cells treated with L-calcein.

Fig. 3.

Uptake of L-calcein by KB cells measured by fluorometry. The cells were incubated with liposomes containing 20 μM calcein for 1 h at 37 °C, washed with PBS and lysed in 1% Triton X-100 and measured for calcein fluorescence, as described in Materials and Methods.

3.3 Cellular Uptake and Cytotoxicity of Liposomes

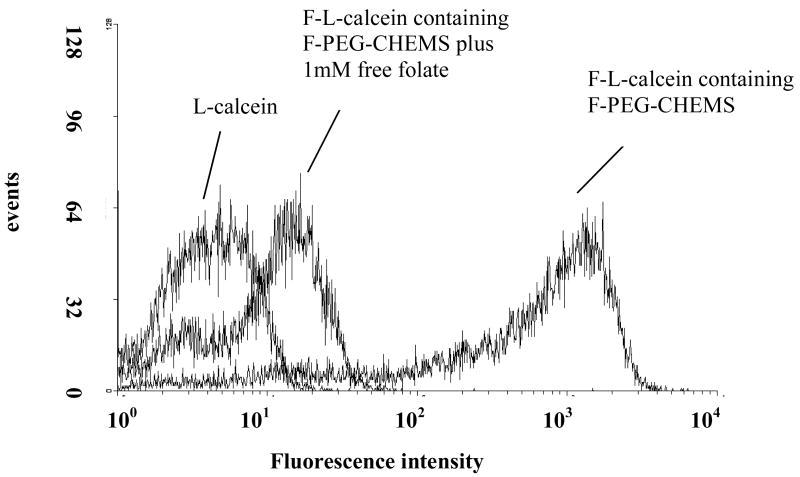

Uptake of liposomes containing F-PEG-CHEMS by KB cells was analyzed by fluorescence microscopy and by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 2, FR-targeted liposomal calcein was more efficiently taken up by the cells compared to non-targeted liposomal calcein, and the uptake could be blocked by 1mM free folic acid. Similarly, flow cytometry results showed that the cellular uptake of FR-targeted liposomal calcein was about 200 times that of non-targeted liposomal calcein and can be blocked by free folate (Fig. 4). These data showed that liposomes targeted with F-PEG-CHEMS could effectively target the KB cells through the FR.

Fig. 4.

Uptake of liposomal calcein by cultured KB cells measured by flow cytometry. KB cells were treated with L-calcein; F-L-calcein; or F-L-calcein plus 1mM free folate for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were then washed with PBS and then analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytotoxicity of F-PEG-CHEMS-containing liposomes loaded with DOX was evaluated in KB cells using an MTT assay. As shown in Table 1, FR-targeted liposomal DOX had about 6 times lower IC50 value compared to non-targeted liposomal DOX. The presence of 1 mM folic acid diminished the difference in IC50 values. Both liposomal formulations showed much higher IC50 values compared to free DOX, which can be directly taken up by cells. These data correlated well with the results from the above described cellular uptake studies and showed that F-PEG-CHEMS is potentially useful in the synthesis of FR-targeted liposomes carrying a therapeutic agent.

Table 1.

Cytotoxicity of various DOX formulations to KB cells

| Treatment Group | IC50(μM) * |

|---|---|

| F-L-DOX | 10±1.2 |

| F-L-DOX+1mM folic acid | 19±1.6 |

| L-DOX | 57±4.3 |

| Free DOX | 0.43±0.05 |

Values shown are means and standard deviations (n=3).

3.4 Pharmacokinetic Properties of DOX-Loaded Liposomes

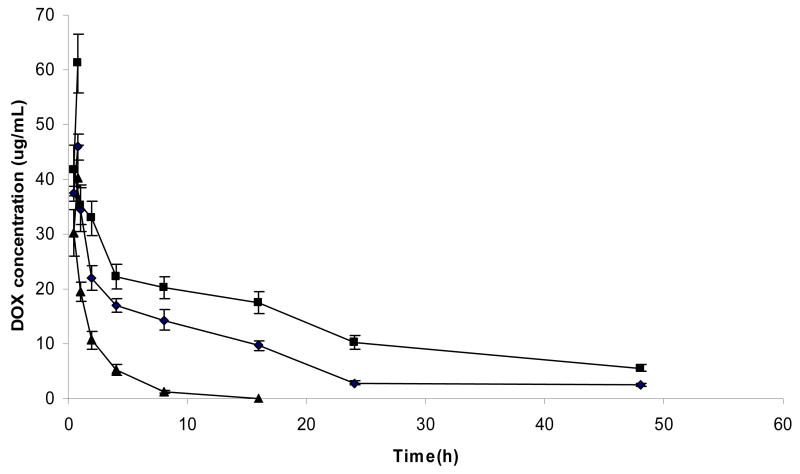

Plasma clearance kinetics of liposomal DOX was studied in ICR mice, as shown in Fig. 5. Pharmacokinetic parameters, obtained using the WinNonlin software and a two-compartment model, are summarized in Table 2. As expected, free DOX showed rapid clearance from the plasma. Meanwhile, liposomal DOX formulations showed much longer circulation time. FR-targeted liposomal DOX containing F-PEG-CHEMS was cleared more rapidly compared to non-targeted liposomal DOX. This is consistently with findings on F-PEG-DSPE and F-PEG-Chol-containing liposomes reported previously (Gabizon et al., 2003; Zhao et al., 2007).

Fig. 5.

Pharmacokinetic profiles of various DOX formulations. ICR mice were given i.v. injections of the various formulations at a dose of 5mg/kg in DOX. Data represent the mean ± 1 standard deviation (n=3). (▲) free DOX, (■) F-L-DOX, (♦) L-DOX

Table 2.

Pharmacokinetic parameters of DOX formulations in ICR mice following i.v. administration

| AUC(μg h/mL) | t1/2β (h) | CL(mL/h) | MRT(h) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free DOX | 76.7 | 2.85 | 1.30 | 2.83 |

| F-L-DOX | 398 | 12.3 | 0.25 | 16.3 |

| L-DOX | 764 | 17.1 | 0.13 | 24.0 |

4. Conclusions

FR-targeted liposomes, synthesized using F-PEG-DSPE or F-PEG-Chol, have been shown previously to effectively target FR-expressing tumor cells. In this study, F-PEG-CHEMS is shown to also exhibit excellent FR-targeting properties. F-PEG-DSPE carries two negative charges. This may lead to reduced systemic circulation time for liposomes containing F-PEG-DSPE in vivo. F-PEG-Chol contains a carbamate bond between the PEG linker and the cholesterol anchor. F-PEG-Chol targeted liposomes gradually lose their FR targeting activity upon storage in 4 °C. This might be due to hydrolysis of the carbamate linkage. F-PEG-CHEMS is structurally similar to F-PEG-Chol but contains amide and ester linkages, both of which are much more stable compared to a carbamate linkage. FR-targeted liposomes containing F-PEG-CHEMS retained high uptake efficiency by KB cells even after 3-month storage at 4 °C.

It was further shown that FR-targeted liposomal DOX containing F-PEG-CHEMS had much greater cytotoxicity compared to non-targeted liposomal DOX. This indicates that F-PEG-CHEMS is potentially useful for FR-targeted liposomal delivery of therapeutic agents.

In pharmacokinetic studies, FR-targeted liposomal DOX was shown to be cleared from circulation more rapidly than non-targeted liposomal DOX, this result is consistent with previous reports on liposomes containing F-PEG-DSPE or F-PEG-Chol(Gabizon et al., 2006). This might be due to increased uptake of the liposomes by macrophages, which express low level of FR-β. This was supported by the finding that free folate blocked the accelerated clearance of FR-targeted liposomes(Gabizon et al., 2006).

In summary, a novel ligand, F-PEG-CHEMS, has been synthesized for preparation of FR-targeted liposomes. Liposomes containing this new ligand had good physical chemical and FR-targeting properties. In addition, FR-targeted liposomal DOX can be specifically taken up by FR over-expressing KB cells, and showed greater cytotoxicity than non-targeted liposomal DOX. Pharmacokinetic studies showed that these liposomes exhibited prolonged circulation time. Since F-PEG-CHEMS has greater hydrolytic stability than F-PEG-Chol reported previously, it might constitute a better candidate for future clinical development of FR-targeted liposomes for which a lengthy shelf-life is essential.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by NCI grant R01 CA095673, and the China Scholarship Council

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Allen TM, Hansen C, Martin F, Redemam C, Yau-Young A. Liposomes containing synthetic lipid derivatives of poly(ethylene) glycols show prolonged circulation half-lives in vivo. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1991;1066:29–36. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(91)90246-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Banerjee R. Liposomes: applications in medicine. J Biomater Appl. 2001;16:3–21. doi: 10.1106/RA7U-1V9C-RV7C-8QXL. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curiel DT. Strategies to adapt adenoviral vectors for targeted delivery. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1999;886:158–171. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elwood PC. Molecular cloning and characterization of the human folate-binding protein cDNA from placenta and malignant tissue culture (KB) cells. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:14893–14901. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritze A, Felicitas H, Kimpfler A, Schubert R, Peschka-Suss R. Remote loading of doxorubicin into liposomes driven by a transmembrane phosphate gradient. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1758:1633–1640. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2006.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon A, Horowitz AT, Goren D, Tzemach D, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. In vivo fate of folate-targeted polyethene-glycol liposomes in tumor-bearing mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:6551–6559. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Horowitz AT, Zalipsky S. Tumor cell targeting of liposome-entrapped drugs with phospholipid-anchored folic acid-PEG conjugates. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2004;56:1177–1192. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabizon A, Shmeeda H, Zalipsky S. Pros and cons of the liposome platform in cancer drug targeting. J Liposome Res. 2006;16:175–183. doi: 10.1080/08982100600848769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goren D, Horowitz AT, Tzemach D, Tarshish M, Zalipsky S, Gabizon A. Nuclear delivery of doxorubicin via folate-targeted liposomes with bypass of multidrug-resistance efflux pump. Clin Cancer Res. 2000;6:1949–1957. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo WJ, Lee T, Sudimack J, Lee RJ. Receptor-specific delivery of liposomes via folate-PEG-Chol. J Liposome Res. 2000;10:179–195. [Google Scholar]

- Haran G, Cohen R, Bar LK, Barenholz Y. Transmembrane ammonium sulfate gradients in liposomes produce efficient and stable entrapment of amphipathic weak bases. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1993;1151:201–215. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(93)90105-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hattori Y, Maitani Y. Folate-linked lipid-based nanoparticle for targeted gene delivery. Curr Drug Deliv. 2005;2:243–252. doi: 10.2174/1567201054368002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hilgenbrink AR, Low PS. Folate receptor-mediated drug targeting: from therapeutics to diagnostics. J Pharm Sci. 2005;94:2135–2146. doi: 10.1002/jps.20457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinrichs WL, Manceňido FA, Sanders NN, Braeckmans K, De Smedt SC, Demeester J, Frijlink HW. The choice of a suitable oligosaccharide to prevent aggregation of PEGylated nanoparticles during freeze thawing and freeze drying. Int J Pharm. 2006;311:237–244. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2005.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke CY, Mathias CJ, Green MA. The folate receptor as a molecular target for tumor-selective radionuclide delivery. Nucl Med Biol. 2003;30:811–817. doi: 10.1016/s0969-8051(03)00117-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempen HJM. Synthetic glycolipids, a process for the preparation, thereof and several uses for these, synthetic glycolipids. U.S. Patents. 4751219 1988

- Kim SH, Jeong JH, Mok H, Lee SH, Kim SW, Park TG. Folate receptor targeted delivery of polyelectrolyte complex micelles prepared from ODN-PEG-folate conjugate and cationic lipids. Biotechnol Prog. 2007;23:232–237. doi: 10.1021/bp060243g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leamon CP, Reddy JA, Vlahov IR, Vetzel M, Parker N, Nicoson JS, Xu LC, Westrick E. Synthesis and biological evaluation of EC72: a new folate-targeted chemotherapeutic. Bioconjug Chem. 2005;16:803–811. doi: 10.1021/bc049709b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee RJ, Low PS. Folate-mediated tumor cell targeting of liposome-entrapped doxorubicin in vitro. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1995;1233:134–144. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(94)00235-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lukyanov AN, Elbayoumi TA, Chakilam AR, Torchilin VP. Tumor-targeted liposomes: doxorubicin-loaded long-circulating liposomes modified with anti-cancer antibody. J Control Release. 2004;100:135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamot C, Drummond DC, Hong K, Kirpotin DB, Park JW. Liposome-based approaches to overcome anticancer drug resistance. Drug Resistance Updates. 2003;6:271–279. doi: 10.1016/s1368-7646(03)00082-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M, Cheng YC. Demonstration of a high affinity folate binder in human cell membranes and its characterization in cultured human KB cells. J Biol Chem. 1979;254:11312–11318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XG, Zheng X, Shi GF, Wang HQ, Ratnam M, Lee RJ. Strategy for the treatment of acute myelogenous leukemia based on folate receptor β-targeted liposomal doxorubicin combined with receptor induction using all-trans retinoic acid. Blood. 2002;100:594–602. doi: 10.1182/blood.v100.2.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan XG, Wu G, Yang WL, Barth RF, Tjarks W, Lee RJ. Synthesis of cetuximab-immunoliposomes via a cholesterol-based membrane anchor for targeting of EGFR. Bioconjug Chem. 2007;18:101–108. doi: 10.1021/bc060174r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Papahadjopoulos D, Allen TM, Gabizon A, Mayhew E, Matthay K, Huang SK, Lee K, Woodle MC, Lasic DD, Redemann C, Martin FJ. Sterically stabilized liposomes: Improvements in pharmacokinetics and antitumor therapeutic efficacy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:11460–11464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.24.11460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez AT, Domenech GH, Frankel C, Vogel CL. Pegylated liposomal doxorubicin (Doxil®) for metastatic breast cancer: the cancer research network, Inc. Experience Cancer Invest. 2002;20 2:22–29. doi: 10.1081/cnv-120014883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thirumamagal BT, Zhao XB, Bandyopadhyaya AK, Narayanasamy S, Johnsamuel J, Tiwari R, Golightly DW, Patel V, Jehning BT, Backer MV, Barth RF, Lee RJ, Backer JM, Tjarks W. Receptor-targeted liposomal delivery of boron-containing cholesterol mimics for boron neutron capture therapy(BNCT) Bioconjug Chem. 2006;17:1141–1150. doi: 10.1021/bc060075d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Liu Q, Lee RJ. A folate receptor-targeted liposomal formulation for paclitaxel. Inter J Pharm. 2006a;316:148–153. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2006.02.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu G, Barth RF, Yang W, Lee RJ, Backer MV, Backer JV. Boron containing macromolecules and nanovehicles as delivery agents for neutron capture therapy. Anti-Cancer Agents in Med Chem. 2006b;6:167–184. doi: 10.2174/187152006776119153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong XB, Huang Y, Lu WL, Zhang X, Zhang H, Nagai T, Zhang Q. Enhanced intracellular delivery and improved antitumor efficacy of doxorubicin by sterically stabilized liposomes modified with a synthetic RGD mimetic. J Control Release. 2005;107:262–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2005.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Xiang GY, Zhang YJ, Yang KY, Fan W, Lin JL, Zeng FB, Wu JZ. Increase of doxorubicin sensitivity for folate receptor positive cells when given as prodrug N-(phenylacetyl) doxorubicin in combination with folate-conjugated PGA. J Pharm Sci. 2006;95:2266–2275. doi: 10.1002/jps.20714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao XB, Muthusamy N, Byrd JC, Lee RJ. Cholesterol as a bilayer anchor for PEGylation and targeting ligand in folate-receptor-targeted liposomes. J Pharm Sci. 2007;96:2424–2435. doi: 10.1002/jps.20885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]