Abstract

Singlet oxygen (1O2) is a reactive oxygen species that may be generated in biological systems. Photodynamic therapy generates 1O2 by photoexcitation of sensitizers resulting in intracellular oxidative stress and induction of apoptosis. 1O2 oxidizes amino acid side chains of proteins and inactivates enzymes when generated in vitro. Among proteogenic amino acids, His, Tyr, Met, Cys, and Trp are known to be oxidized by 1O2 at physiological pH. However, there is a lack of direct evidence of oxidation of proteins by 1O2. Because 1O2 is difficult to detect in cells, identifying oxidized cellular products uniquely derived from 1O2 could serve as a marker of its presence. In the present study, 1O2 reactions with model peptides analyzed by tandem mass spectrometry provide insight into the mass of prominent adducts formed with the reactive amino acids. Analysis by MALDI-TOF and tandem mass spectrometry of peptides of cytochrome c exposed to 1O2 generated by photoexcitation of the phthalocyanine Pc 4 showed unique oxidation products, which might be used as markers of the presence of 1O2 in the mitochondrial intermembrane space. Differences in the elemental composition of the oxidized amino acid residues observed with cytochrome c and the model peptides suggest the protein environment can affect the oxidation pathway.

Keywords: singlet oxygen, amino acids, proteins, cytochrome-c, tandem mass spectrometry, protein modification, histidine, tryptophan, phenylalanine, methionine, oxidation, phthalocyanine, photodynamic therapy

Introduction

Intracellular generation of singlet oxygen

Singlet oxygen (1O2) is a unique reactive oxygen species (ROS) in that its chemical reactivity derives from its characteristic electronically excited state. The lowest energy singlet state (1Δg) of O2 is 94 kJ·mol-1 above the ground state triplet and is the common form of 1O2 [1]. The lifetime of 1O2 depends on its environment, but in most solvents it falls in the range of 1-100 μs. In neutral-pH aqueous solution the lifetime is 2-4 μs in H2O and 53 ± 5 μs in D2O [2]. In biological systems, 1O2 may be efficiently generated by either endogenous or exogenous sensitizers that transfer their excited state energy to ground state molecular oxygen [3] or as one of the products of peroxidase enzymes [4]. An alternative source of 1O2 of potential pathological significance is the decomposition of lipid peroxidation products which are formed during ischemia-reperfusion injury [5, 6].

1O2 may be intentionally generated in biological tissues by photodynamic therapy (PDT) which employs a photosensitizing drug and visible light to produce an oxidative stress in cells and ablate cancerous tumors [7, 8]. PDT is also used for treating certain non-cancerous conditions that are generally characterized by the overgrowth of unwanted or abnormal cells [8]. Photosensitizers employed for PDT are most commonly porphyrins or certain porphyrin-related macrocycles, such as phthalocyanines or pheophorbides. Most photosensitizers for PDT are efficient producers of 1O2 through Type II photochemistry, which is considered to be the dominant mechanism for PDT in cells and tissues [7, 9].

Pc 4, a silicon phthalocyanine (Pc) photosensitizer [10], effectively generates 1O2 when exposed to red light in the presence of O2. Of particular importance for this study, Pc 4 absorbs red light and produces 1O2 by electronic energy transfer without forming superoxide by electron transfer. These and other virtues have led to clinical trials at University Hospitals Case Medical Center with Pc 4 being used in PDT for the treatment of cancer.

Reactions of singlet oxygen

The primary target of 1O2 generated in biological systems may be proteins. Proteins have a high rate constant for reaction, a high effective concentration in cells [11], and proximity to the lipid membranes proposed as the site of 1O2 generation. The reactions of 1O2 with amino acids and the reaction products have been reviewed [11, 12]. Among the proteogenic amino acids, His, Tyr, Met, Cys, and Trp are known to undergo rapid chemical reaction with 1O2 at physiological pH [12, 13]. Model reactions of singlet oxygen with His [14-16] and Trp [17] have resulted in the identification of numerous different products, but the major reaction pathways are summarized in Figure 1. While numerous studies have shown 1O2 can inactivate enzymes [13, 18], classical studies identified the modified residue types by losses detected following acid hydrolysis and amino acid analysis [13] [19]. Typically, His and Trp decrease with occasional increases of Asp/Asn. The identification of the actual products of the reaction of 1O2 with proteins is less well studied, but it is anticipated that these five residues may be most frequently modified. These five residues may also react with •OH, ONOO-, and H2O2. Consequently, determination of which residues are modified will be insufficient to implicate 1O2; this would require the characterization of unique oxidative modifications.

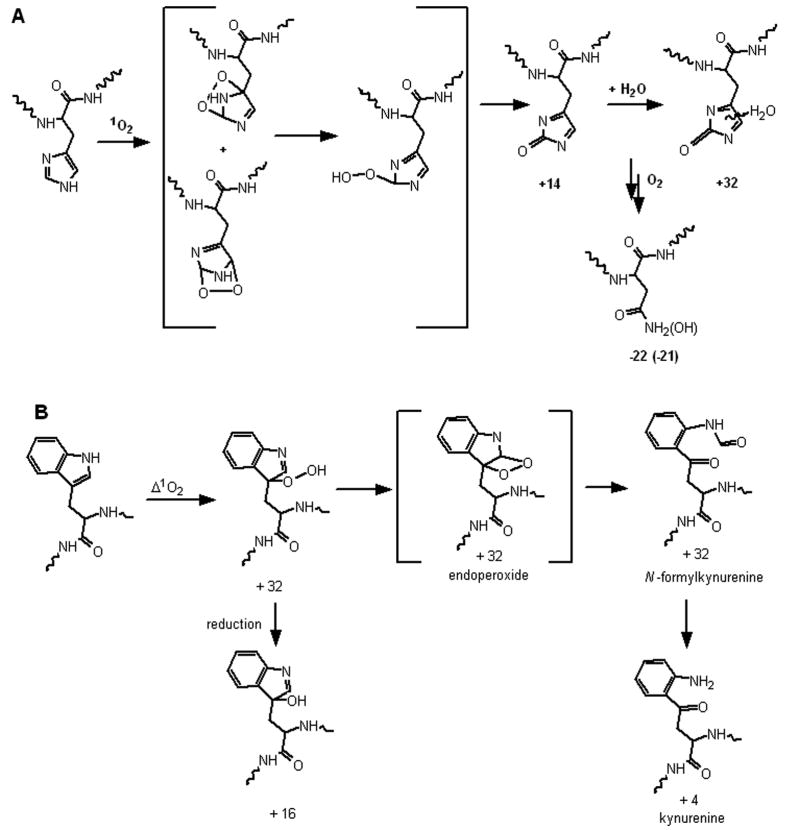

Figure 1.

Potential oxidation products and their integral mass increments relative to the unmodified amino acid residue are given.for (A) His and (B) Trp by 1O2. The endoperoxide and hydroperoxide forms of the His modification are shown in brackets since they were shown to decompose above 0 °C [16]. Water addition to the imidazolone may occur at any of the three imidazolone carbons. The scheme for Trp oxidation to N-formylkynurenine is based on [17]

The primary chemical reactions of 1O2 with mitochondrial proteins are important since confocal microscopy indicates Pc 4 localizes in mitochondrial and ER/Golgi membranes [20-23]. PDT with Pc 4, as well as with other photosensitizers that localize to mitochondria, induces apoptosis in many types of cells and tumors [8, 24, 25]. The primary apoptotic mechanism triggered by Pc 4-PDT is the mitochondrial (intrinsic) pathway, wherein photooxidation damage leads to opening of the permeability transition pore, loss of the mitochondrial membrane potential, release of cytochrome-c (Cyt-c) from mitochondria into the cytosol [21, 26, 27], and the activation of a cascade of apoptosis-mediating caspases [8]. Upon photoirradiation of Pc 4-loaded cells, a sub-set of mitochondrial and ER proteins undergoes immediate photodamage, as revealed on Western blots as the loss of native protein and the appearance of high-molecular weight complexes [22, 28, 29].

Role of Cytochrome-c in response to 1O2

The precise mechanism for the PDT-induced release of Cyt-c from the mitochondrial intermembrane space remains unclear. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer studies indicate that some Pc 4 colocalizes with cardiolipin [23], a phospholipid of the inner mitochondrial membrane. Cardiolipin has an affinity for Cyt-c, placing Pc 4 in the vicinity of Cyt-c. Oxidation of cardiolipin could disrupt electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions to create a soluble pool of Cyt-c that can pass into the cytosol in a Bax-dependent process [30]. Oxidized Cyt-c may enhance its own release through its acquired peroxidase activity, which leads to increased cardiolipin oxidation [31, 32].

As an abundant 12-kDa protein localized to the intermembrane space of mitochondria, Cyt-c is situated in the region where Pc 4-PDT would generate 1O2. Characterization of the chemical modification will provide insight into the loss of function reported following exposure of Cyt-c to 1O2. Further identifying modifications of amino acid residues in Cyt-c that would be uniquely attributable to reaction with 1O2 could provide a specific marker for this ROS and its mitochondrial production. Previous studies have shown that 1O2 modifies Cyt-c by oxidizing its ferro-form and inactivating its function as an electron carrier [33, 34]. Amino acid analysis of Cyt-c following visible light irradiation of a hematoporphyrin solution resulted in destruction of His, Trp, Tyr, and Met residues [19]. Direct evidence for modification of amino acid side chains of Cyt-c or other mitochondrial proteins by 1O2 has not been reported to our knowledge [35]; however, the chemical modification of Cyt-c attendant to various forms of oxidative stress has been well studied [36-40].

Because 1O2 is difficult to detect in cells, there is an interest in identifying oxidized cellular products that are uniquely derived from that oxidant, thereby directly indicating its presence, and potentially serving as a surrogate marker of photodynamic dose. One such product is 3β-hydroxy-5α-cholest-6-ene-5-hydroperoxide derived from 1O2 reaction with cholesterol [41]. Since there is little cholesterol in mitochondrial membranes, direct targets of 1O2 attack present in mitochondria would be more useful for studying PDT with Pc 4 or similar photosensitizers on this organelle. Either cardiolipin or Cyt-c might be directly oxidized by PDT-generated 1O2 to yield a signature product.

In this study, Cyt-c and two model peptides, P824 and tryptophan cage (Trp-cage) [42], were irradiated with 670–675 nm light in the presence of the phthalocyanine Pc 4-malate salt (Pc 4-m) and analyzed by MALDI-TOF-MS and LC-ESI-MS2. P824, an 8-residue peptide (ASHLGLAR) with a single His residue, and Trp-cage, a 20-residue peptide (NLYIQWLKDGGPSSGRPPPS) with single Tyr and Trp residues, were chosen to characterize the reaction of 1O2 with these residues in their context as residues in a peptide. Then, photooxidation of Cyt-c by Pc 4 and light was examined by mass spectrometry revealing evidence of oxidative modification of Trp and His residues, with the His modification potentially diagnostic for oxidation by 1O2.

Experimental

Materials

Horse heart Cyt-c was purchased from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA, USA), α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid and P824 from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA), sequencing-grade modified trypsin from Promega (Madison, WI, USA) and ZipTips from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). Trp-cage was synthesized by Biomer Technology (Hayward, CA, USA). Millipore water (18 MΩ) was used throughout.

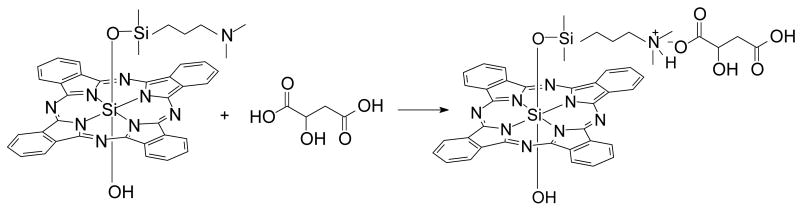

Synthesis of Pc 229

Pc 229, herein referred to as Pc 4-malate, [HOSiPcOSi(CH3)2(CH2)3NH(CH3)2]+ [HOC(O)CH2CHOHC(O)O]-. A mixture of Pc 4, HOSiPcOSi(CH3)2(CH2)3N(CH3)2, (10 mg, 14 μmol) synthesized as described [43] and L-(–)-malic acid (2.3 mg, 17 μmol) in ethanol (20 mL) was stirred for 30 min, and then dried by rotary evaporation (room temperature). The solid was dissolved in toluene and chromatographed (Bio-Beads S-X3; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with toluene elution, dried, washed (CH3CN), air dried, and weighed (5.1 mg, 43 %). UV-vis (toluene) λmax, nm (log ε): 670 (5.0). NMR (CDCl3): δ 9.35 (m, 8H, 1, 4-Pc H), 8.30 (m, 8H, 2, 3-Pc H), 3.92 (d, H, C(O)OCHOH), 2.55 (m, 2H, C(O)OCHOHCH2), 1.95 (s, 6H, NCH3), 1.21 (t, 2H, SiCH2CH2CH2), -1.20 (m, 2H, SiCH2CH2), -2.29 (t, 2H, SiCH2), -2.94 (s, 6H, SiCH3). HR-MALDI (m/z): [M-OH- C(O)OCHOHCH2C(O)OH]+ calcd for M as C43H41N9O7Si2, 700.2425; found, 700.2452, 700.2421.

Pc 4-malate is a blue solid which dissolves in C2H5OH (4.2 mg/mL) or in 2% C2H5OH:H2O (v:v) solution (0.2 mg/mL). It is also soluble in CH2Cl2, dimethylformamide, moderately soluble in toluene, and insoluble in hexanes.

1O2 generation

Pc 4-malate was dissolved in ethanol and diluted in H2O or D2O to give a final concentration of 6 μM and a residual ethanol concentration 1-2%. The final concentration of Pc 4-malate was determined by measuring the absorbance at 674 nm (ε = 230,000 M-1cm-1). To these solutions, Cyt-c or the peptides were added to final concentrations of 5 μM and 10 μM, respectively, at pH 6.5. Sample solutions (2 mL) were pipetted into 3.5-cm diameter tissue culture dishes, resulting in solution depths of about 2 mm, and exposed to 100 mJ/cm2 red light produced by a light-emitting diode array (EFOS, Mississauga, Ontario, Canada, λmax 670–675 nm) at room temperature over varying times up to 50 min. To determine whether peroxides were present, thiourea was added to 1 mM following irradiation in one set of experiments and during the irradiation in a second set of experiments [44]

Tryptic digestion

Irradiated Cyt-c solutions were dried in a Speed Vac concentrator, redissolved in 20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, and filtered through cotton to remove the precipitated Pc 4. The Cyt-c in the filtrate was reduced with DTT, alkylated with iodoacetamide and digested with trypsin at 37 °C for 16 h. The digest was desalted and eluted with 60% acetonitrile and 40% TFA (0.1%) onto a stainless steel MALDI sample block from ZipTips according to the manufacturer's instructions. Alternatively, the digest was concentrated to 80 μM for LC-MS2 analysis.

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry

MALDI-TOF mass spectrometric analyses of the oxidized peptides and Cyt-c were performed with a Bruker BiFlex III MALDI-TOF-MS equipped with a pulsed N2 laser (3 ns pulse at 337 nm) and XTOF acquisition software. The reflectron mode was used with an accelerating voltage of -20 kV and a laser power attenuation ranging from 70 to 85 with an average of 3000 shots for digested Cyt-c and 500 shots for the peptides. The data were processed using m/z software [45].

Electrospray mass spectrometry

LC-MS2 analyses of the Cyt-c tryptic digests were performed using a ThermoFinnigan LCQ Advantage spectrometer in the Case Center for Proteomics (Cleveland, OH, USA). The peptides were analyzed by data-dependent acquisition of full scan mass spectra and MS2 scans for the most abundant ion, after separation on a reverse-phase Vydac C18 column (4.6 mm × 15 cm) with a flow rate of 200 μL/min eluted with a linear gradient from 80% buffer A (5% aqueous ethanol containing 0.05% TFA) to 100% buffer B (95% aqueous ethanol containing 0.05% TFA) over 63 min. The peptides modified by 1O2 were verified by direct comparison between the experimental spectra and theoretical peptide sequences using Xcalibur 2.0 software. The predicted fragment ions of peptides containing modified amino acid residues were calculated using an Excel spreadsheet program which permits the elemental composition of a modified residue to be specified. To determine the extent of Cyt-c modification, electrospray ionisation-TOF mass spectra were obtained with Applied Biosystems Q-STAR XL hybrid quadrupole-TOF mass spectrometer and analyzed with Bioworks software.

Results and Discussion

Pc 4 malate

The amino nitrogen of the siloxy ligand of Pc 4 is basic with an estimated pKa of 9.6, thus the formation of Pc 4-malate from Pc 4 and malic acid, pKa 3.4, is a simple acid-base reaction (Equation 1):

|

(1) |

In physiologic pH buffers, Pc 4 should exist as a minimally soluble dissociated salt, although there is a potential for formation of dimers and/or higher oligomers. It is possible to solubilize Pc 4-malate in 1-2 % ethanol in water, the water solubility facilitates the work in biological media. The dissolution of Pc 4-malate gave a clear blue solution, and in the conditions used, the Beer-Lambert law was obeyed, enabling the use the Pc 4-malate salt in this and other biological studies of Pc 4 where, as in the present study, the solubility facilitates the work.

A particular virtue of silicon phthalocyanines is that their reactivity is largely restricted to type II photochemistry, i.e. energy transfer to O2 to generate 1O2. Type I photochemistry, electron transfer to O2 generating superoxide directly and other reactive oxygen species indirectly, usually results in photobleaching of the photosensitizer. After irradiation of Pc4-malate under our experimental conditions, no photobleaching was observed [46]. The photochemistry of Pc 4 is characterized; it has a triplet lifetime expected for Pcs (> 100 μs), a near diffusion limited second order rate constant for reaction with O2, which results in a quantum yield of 1O2 of ∼0.5 in the absence of exogenous quenchers [46, 47].

Modification of peptides by 1O2

His is known to be the most reactive of the proteogenic amino acids with 1O2, with several observed products as shown in Figure 1A [11, 48]. The initial product appears to be the cyclic endoperoxide shown in Figure 1A which can be trapped at -100 °C but decomposes to the hydroperoxide at-78 °C and subsequently to the 2-imidazolone which can be hydrated at any of the carbon positions [16]. Similar modifications of the His residue in P824 were anticipated following red light irradiation of P824 in the presence of Pc 4-malate. Analysis by MALDI-MS identified only two new peaks corresponding to M+14 and M+32 (Figure 2A). HPLC-MS2 analysis confirmed that these new peaks were appropriately assigned to modification of the His residue. The structures of His+14 and His+32 have been previously characterized as the 2-imidazolone and as the hydrated imidazolone species, respectively [11, 48]. Since 1O2 reacts with the unprotonated imidazole, the rate constant of His increases at higher pH consistent with our observation that the relative intensity of the M+14 and M+32 peaks increased when subjected to irradiation at higher pH (data not shown).

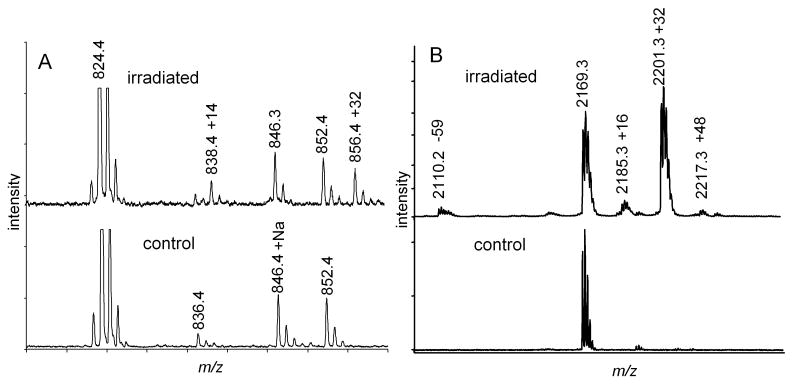

Figure 2.

MALDI-TOF spectra of A) P824 and B) Trp-cage. Lower spectra are of the control peptides and upper spectra are derived from the same peptide exposed to 1O2 generated by photoexcitation of Pc 4. The observed oxidatively generated modifications are identified by their mass increments, A) +14 and +32 and B) -59, +16, +32 and +48, are indicated by the increment in mass of the monoisotopic peaks.

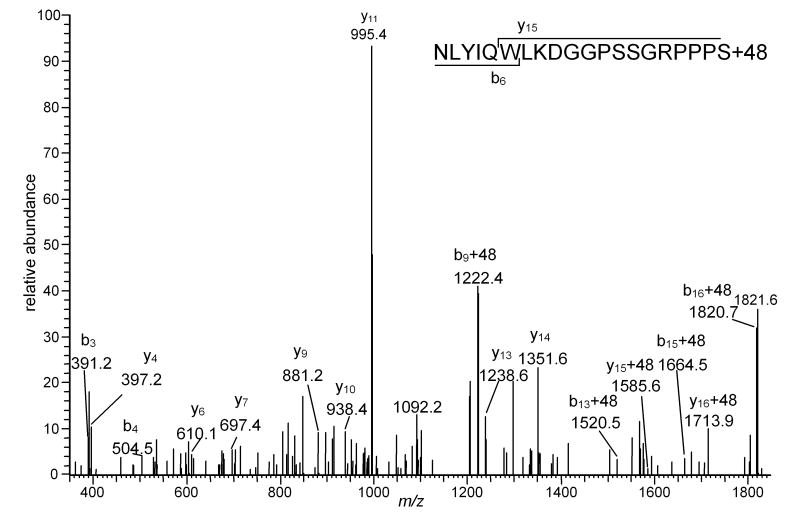

The red-light irradiation of Trp-cage in the presence of Pc 4-malate gave four new peaks, M-59, M+16, M+32, and M+48, when analyzed by MALDI-MS (Figure 2B). Since the rate constant for reaction of Trp (3×107 M-1s-1) with 1O2 is only 4-fold faster than that of Tyr (0.8×107 M-1s-1), it was anticipated that the modified peaks were derived from oxidation of the both Tyr and Trp residues. However, LC-MS2 analysis found that all of the mass altered peptides were derived solely from oxidative modification of Trp. When the reactions of Trp containing dipeptides with 1O2 were studied, structures corresponding to mass increments of +4, +16 and +32 were identified as suggested in Figure 1B [11] [49]. Consistent with our observation of +48 and -59 photochemical products, additional peaks attributed to addition of two O2 molecules and subsequent fragmentations were observed when Trp-Phe was reacted with 1O2 [49] however mass spectrometry does not provide sufficient information to unequivocally assign structures to these modifications. The LC-MS2 spectrum of M+48 peak is shown in Figure 3. It is possible that +48 precursor ion could result from the incorporation of a total of 3 oxygen atoms in the Trp and Tyr residues; however, this possibility is discounted by the presence of b3, b4, y15+48, and y16+48 ions which indicate that the extra mass is not present on the Tyr residue but is contained in product ions containing modified Trp residues (Figure 3). No alterations in the mass spectra were observed following treatment of the oxidized peptides with thiourea (data not shown). If hydroperoxides were present, a decrease in the M+32 peak would be anticipated with a concomitant increase of the M+16 peak. Thiourea reduction of endoperoxides would shift the M+32 peak to M+34. The absence of these shifts is consistent with N-formylkynurenine being the source of the M+32 peak.

Figure 3.

LC- MS2 spectrum of a precursor ion whose m/z corresponds to the Mr of Trp-cage peptide +48. The inset shows the sequence of the peptide and indicates the sequence number of the first product ions in the b- and y-series that contain the modified tryptophan residue. The presence of unmodified b3-b4 and y4-y14 ions confirms the absence of modifications in residues other than the tryptophan.

Reaction of 1O2 with Cyt-c

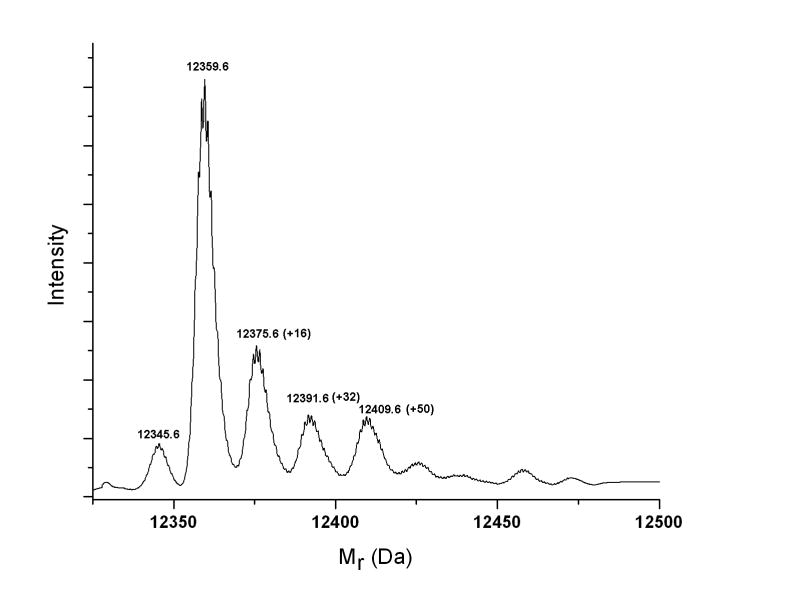

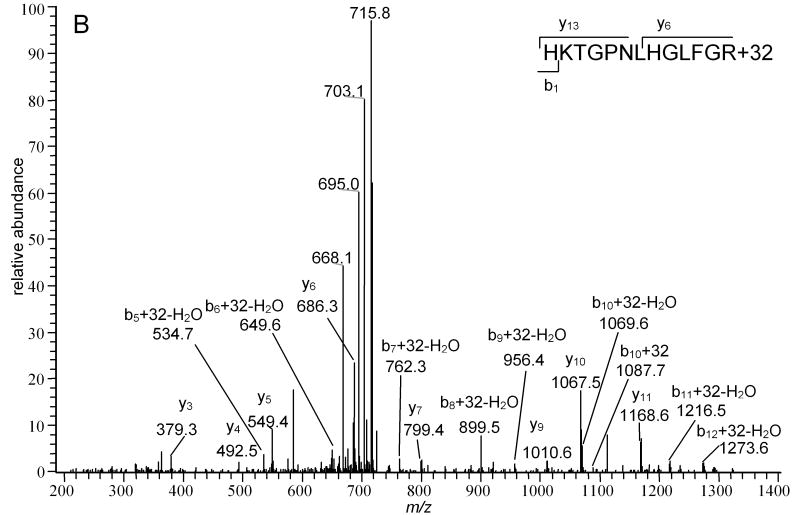

Cyt-c is a heme protein with 104 amino acids containing one Trp, four Tyr, three His, and two Met residues. Following our Pc 4-malate irradiation procedure, electrospray-time of flight mass spectra revealed several modifications (Figure 4). The predominance of +16 and +32 modifications is consistent with most modified proteins having a single modification, which are predominantly the addition of one or two oxygen atoms. Samples of Cyt-c subjected to irradiation with Pc 4-malate in D2O were digested with trypsin and analyzed by both MALDI TOF-MS and LC- MS2. Consistent with the electrospray mass spectrum of the intact Cyt-c, several new peaks corresponding to mass increments +14, +16, and +32 Da relative to unmodified peptides appeared in the MALDI-TOF spectrum of the tryptic digest. In addition to determining which residue is modified in the peptides identified by MALDI, the fragmentation data from LC- MS2 made it possible to recognize additional peptides with oxidative modifications. These peptides, the mass increments, and the identity of the modified residues are presented in Table 1.

Figure 4.

Deconvoluted electrospray-time of flight mass spectrum of Cyt-c exposed to 1O2. The prominent +16, +32 and +50 adducts of Cyt-c not present in control samples indicate that the reaction of 1O2 with Cyt-c results in oxidation of the protein. While evidence for multiple oxidations are present, the most intense +16 and +32 peaks correspond to single oxidative events and even the +50 adduct can correspond to the addition of a single O2 and H2O.

Characterization of Met and Trp modification

Cyt-c has two Met residues, Met65 and Met80. LC- MS2 spectra showed that both of these residues were modified as M+16, the common sulfoxide oxidation product of this amino acid. Generation of 1O2 resulted in both +32 and +16 oxidation products of Met80. The unusual +32 adduct may be attributed to either a peroxo species or a sulfone [50]. Met residues are also oxidized by peroxides, •OH, and ONOO- [51], so the presence of modified Met residues in general, and Met80 in particular, can not be used to identify the responsible ROS. However since oxidation of Met80 is subject to oxidation by all of these ROS, it could potentially serve as a generalized monitor of ROS in vivo. Furthermore modification of Met80 may be pharmacologically relevant as it is associated with activation of Cyt-c's peroxidase activity [52, 53]

A unique Trp present in Cyt-c is also modified by exposure to 1O2. Although four different types of modification were observed for Trp modification by 1O2 in Trp-cage, only the Trp+16 adduct was found in the reaction with Cyt-c. The MS2 data were specifically interrogated for the +32, +48 and -59 modifications by examining the appropriate mass range ion chromatograms and by adding the appropriate masses to the data dependent include mass list. In spite of these specific efforts, no evidence for these modifications was found. The difference between Trp-cage where the +32 adduct predominates and Cyt-c where the +16 adduct predominates, suggests that the protein environment alters the oxidation pathway initiated by 1O2, favoring the reduction of the initial peroxide or delaying the formation of the endoperoxide shown in Figure 1B. Exposure of rat heart Cyt-c to γ-irradiation also resulted in a mass increment of +16 in the Trp-containing peptide, so detection of Trp oxidation by mass spectrometry cannot serve as a specific marker for 1O2 [54].

Characterization of His modifications

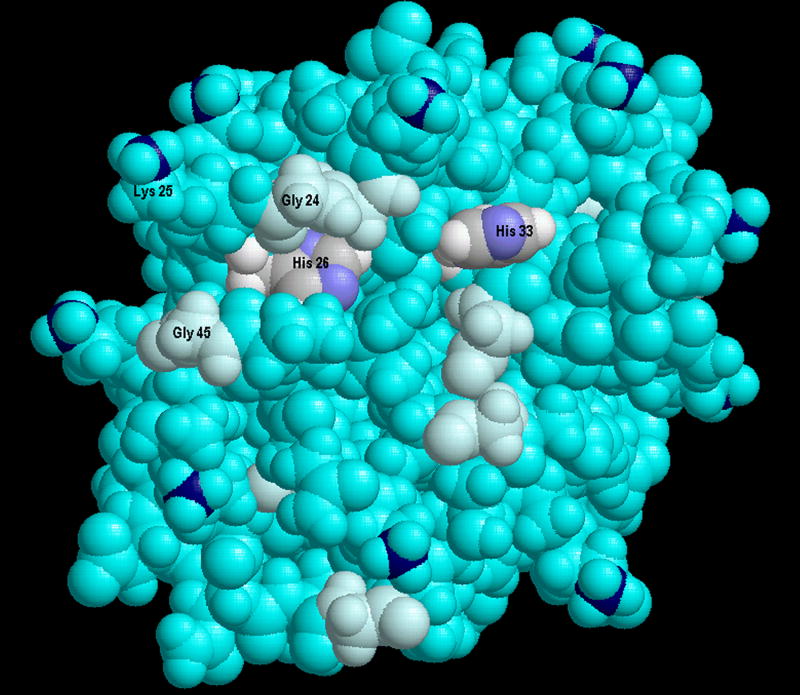

There are three His residues, His18, His26, and His33, present in Cyt-c. Both His26 and His33 were found to be modified. While an unmodified tryptic peptide containing His18 was identified, this peptide contains the Cys residues covalently attached to the heme, which can confound any interpretation of observed and unobserved modifications. The solvent accessibility of His26 and His33 is shown in Figure 5 adapted from the crystal structure.

Figure 5.

The crystal structure of horse heart Cyt-c (coordinates obtained from 2FRC in the Protein Data Bank [60]) represented as spheres drawn at 90% of the CPK radius with all atoms colored cyan except as noted. His28 and His33 which are modified by 1O2 are differentially colored with carbons gray, hydrogens white, and nitrogen blue. To emphasize the potential mobility around His26, Gly residues were colored lighter cyan. To permit identification of Lys residues, the ε-amino nitrogens are dark blue. The view was created with RasTop [61].

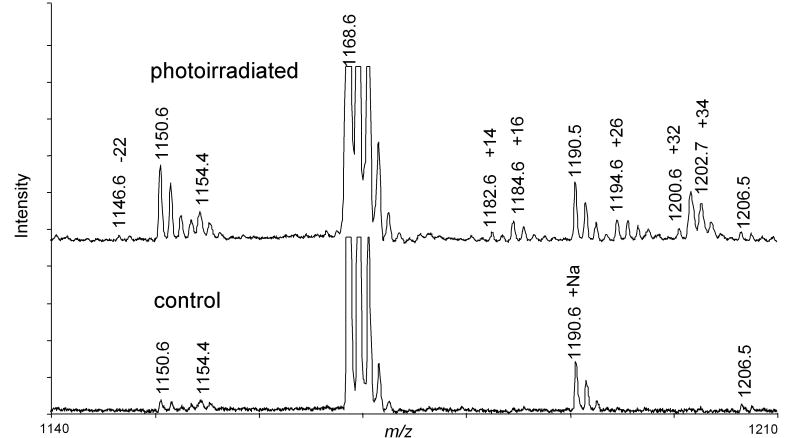

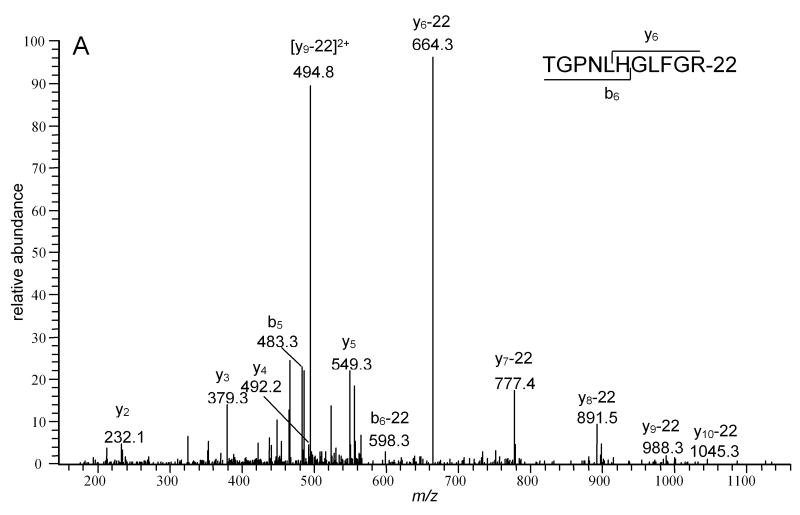

Five different modifications of His33 with mass increments of -22, +14, +26, +32 and +34 Da were detected relative to the unmodified K.TGPNLHGLFGK38 tryptic peptide. The relative intensities of the modified peaks were <2% of the unmodified peptide peak in the MALDI spectrum (Figure 6). The proposed structures of the His-22, His+14 and His+32, adducts are shown in Figure 1A. The structure and mechanism of the His+32 adduct following reaction with 1O2 has been established by MS2 and MS3. A key observation was identifying that the hydroxyl incorporated 17O when 1O2 was generated in H217O [15]. An imidazole endoperoxide has been isolated at -78 °C but decomposes on warming. Since thiourea will not react with the hydroxyimidazolone our results are consistent with this structure as well. The loss of water (His+14) may occur during the ionization and not be present in solution. The LC-MS2 spectrum of the peptide identified as the -22 adduct is shown in Figure 7A. This spectrum confirms the sequence of the peptide and is consistent with a multiple oxidation of the His residue to asparagine [14]. Ozonolysis of His results initially in a +48 adduct identified by MS2 as 2-amino-4-oxo-4-(3-formylureido)butanoic acid followed by decomposition to asparagine, the -22 adduct [55, 56]. This conversion is also consistent with the earliest reports of His photooxidation [14], but does not represent the major product detected following minimal reaction with 1O2 with the products detected by MS. With its relative intensity and unique mass increment, the peptides derived from Cyt-c containing a His33 +14 modification have the potential to be used as a marker for the presence of mitochondrial 1O2.

Figure 6.

MALDI spectra of TGPNLHGLFGR peptide (lower) and the same peptide exposed to 1O2 generated by photoexcitation of Pc 4 (upper). The observed modifications, -22, +14, +16, +26, +32, +34 are indicated by the increment in mass of the monoisotopic peaks.

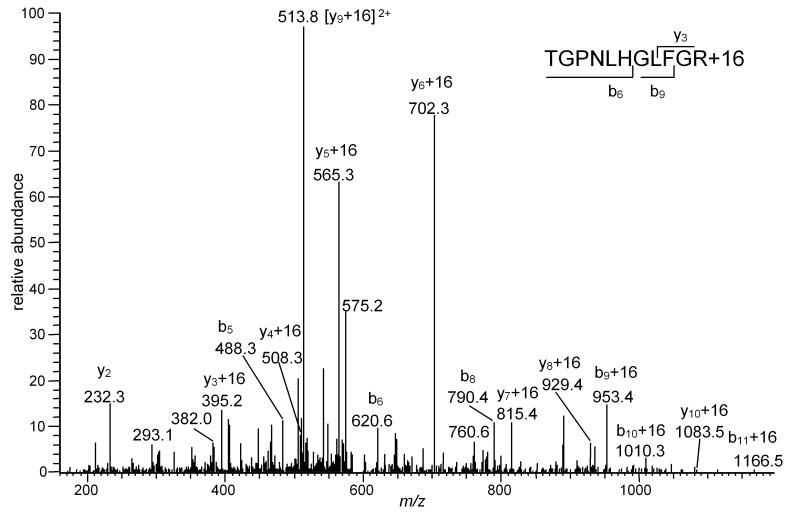

Figure 7.

LC- MS2 spectra of precursor ions A) whose m/z corresponds to the Mr of TGPNLH33GLFGR peptide-22 (574.1) and B) whose m/z corresponds to the Mr of H26KTGPNLHGLFGR peptide+32 (734.2). The insets show the sequences of the peptides and indicate the sequence number of the first product ions in the b- and y-series that contain the modified A) His33 residue and B) His26 residue. The presence of B) b5+32+H2O, b6+32+H2O, b7+32+H2O, y6, y7, y9, y10 and y11 ions confirms the absence of modifications of His33 in H26KTGPNLHGLFGR peptide.

The peptide containing His18 is clearly modified as +14 and +28, but it is not clear whether the modification was derived from His18. Two Cys residues present in this peptide make the LC- MS2 spectrum more complicated. Both Cys residues form thioether linkages to the side chains of the heme. It is not certain when these thioethers are cleaved but MALDI-TOF spectra routinely confirmed the existence of the free thiol groups in the peptide (mass of the peptide matches with theoretical value). However, they when analyzed by LC-MS2 the reduction in mass by 2 Da suggested the formation of an intramolecular disulfide bond.

Modification of His26 can be detected only when the trypsin cleavage at Lys27 is missed, with the resulting peptide containing both His26 and His33 (K25.HKTGPNLHGLFGK38). In every MALDI-TOF spectrum of peptides obtained following exposure of Cyt-c to 1O2, the HKTGPNLHGLFGK +32 Da peptide was always the most intense modified peptide, and sometimes the only one observed. LC-MS2 confirmed that from the precursor ion m/z 734.27, the only detectable product ions were derived from oxidation of His26 alone (Figure 7B). The unmodified precursor peptide peak with one missed cleavage has not been observed. We attribute these observations to the potential for His26 oxidized to the 2-imidazolone to form a crosslink by addition of the ε amine of Lys27 to the electrophilic imine-one. Previous studies of His or imidazole oxidation have provided significant precedents for this addition [14] [57] [15]. This intramolecular crosslink would prevent the tryptic digestion following Lys27, and eliminate the potential to observe MS2 peaks corresponding to cleavage of the His26-Lys27 peptide bond. Because His26 was shown to be the most sensitive to 1O2, there may be other modifications present, as observed for His33. However, only the M+14 and M+32 species prevent the tryptic cleavage. In the absence of crosslink formation, the resulting dipeptide generated by tryptic digestion and containing the modified His residue, H*K, would be too small to detect.

Potential use of His 26 modification as a marker of 1O2

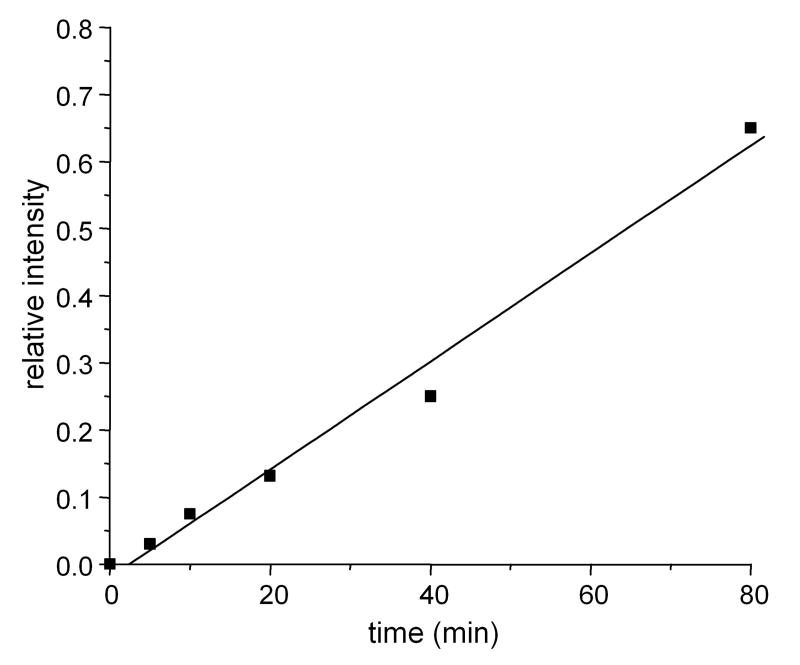

The +14 and +32 modifications appear to be specific to 1O2. His modification by •OH results in +16 adducts and does not induce the formation of the observed Lys-His crosslink. The specificity of this modification and the absence of any background peptide should make this peptide a marker for the presence of 1O2 vis-a-vis its reaction with Cyt-c in biological samples. This sequence within Cyt-c is 100% conserved in chicken, rat, mouse, bovine and human proteins, suggesting this modified peptide could be observed in most species. The intensity of this peak relative to that of an unmodified Cyt-c peptide at low-modest extents of modification is proportional to the irradiation time and hence 1O2 exposures (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Relative intensity of the H26KTGPNLHGLFG+32 peak to the unmodified TGPNHGLFG M3 peak as a function of irradiation time determined from MALDI-TOF spectra of digested Cyt-c irradiated for 0, 5, 10, 20, 40, and 80 min. The linear relationship indicates that the relative intensity of H26KTGPNLHGLFG+32 peak is proportional to the amount of 1O2 generated by photoexcitation.

Modification of Phe and Tyr

An unanticipated observation is the modification of Phe residues and absence of Tyr modification. Cyt-c has four Phe residues, Phe10, Phe36, Phe46, and Phe82. Both Phe36 and Phe82 were found to be modified as Phe+16. Because the aromatic ring of Phe is not inherently reactive with 1O2, benzene and toluene have been used as solvents for 1O2 reactions [58]. The apparent hydroxylation of these Phe residues reflects either an enhanced reactivity of the aromatic ring or the production of a secondary oxidant during the generation of and exposure to 1O2. Despite the presence of Phe36 and Phe82 in peptides containing His33 and Met80, respectively, which have been modified, the MS2 spectra strongly implicate Phe oxidation due to the presence of y3+16, y4+16, and y5+16 as well as b6 and b8 product ions (Figure 9). The two Phe residues modified following generation of 1O2 were also modified by the same mass increment following exposure to •OH generated by radiolysis. However modifications of Phe10 and Phe46 were not detected, although they are predominant modifications generated by •OH [36, 59].

Figure 9.

LC- MS2 spectrum of a precursor ion whose m/z corresponds to the Mr of TGPNLHGLF36GR+16 (592.8). The inset shows the sequence of the peptide and indicates the sequence number of the first product ions in the b- and y-series that contain the modified Phe residue. The presence of b6, b8 and y3-y5 ions confirms the absence of modifications of His33.

Because Tyr residues are known to react with 1O2, coupled with their solvent accessibility, the absence of any oxidized Tyr residues is notable. The unmodified peptides can be detected, but +14, +16, and +32 Da ion chromatograms relative to the unmodified peptide, in +1, +2, or +3 charge states, failed to reveal any candidate molecular ions for further analysis.

Cyt-c oxidation by 1O2 in H2O

The lifetime of 1O2 in H2O is ∼10 fold smaller than in D2O, thus decreasing its effective reactivity. Oxidation of Cyt-c in H2O gave only one distinguishable modified peak in the MALDI spectrum corresponding to peptide HKTGPNLHGLFG +32. LC-MS2 analysis identified only six of the oxidatively modified peaks that were present following oxidation in D2O. The list of modified peptides following generation of 1O2 in H2O is shown in Table 1. The greater oxidation in the presence of D2O provides support for these modifications to be derived from the action of 1O2.

Summary

1O2 generated by photoexcitation of Pc4 modifies numerous amino acids of Cyt-c, predominantly His, Trp and Met. The reaction with these residues can be influenced by the protein environment, with different oxidatively generated modifications observed when the residues are present in different environments. The reaction with His generates both +32 and +14 adducts that are not observed with other ROS and may serve as markers for the in vivo production of 1O2. This is particularly true for His26 in Cyt-c and for PDT studies where the photosensitizer is known to accumulate in mitochondria.

List of abbreviations

- Cyt-c

cytochrome c

- LC-MS2

liquid chromatography- tandem mass spectrometry

- P824

peptide ASHLGLAR

- Pc

phthalocyanine

- PDT

photodynamic therapy

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- Trp-Cage

tryptophan cage peptide

Footnotes

This work was supported by NIH/NIA grant (P01 AI55739) to V.E.A and by NIH/NCI grants (R01 CA083917, R01 CA106491 and P01 CA48735) to N.L.O.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Schmidt R. Photosensitized generation of singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:1161–1177. doi: 10.1562/2006-03-03-IR-833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindig BA, Rodgers MAJ, Schaap AP. Determination of the lifetime of singlet oxygen in water-d2 using 9,10-anthracenedipropionic acid, a water-soluble probe. J Am Chem Soc. 1980;102:5590–5593. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cadet J, Ravanat JL, Martinez GR, Medeiros MH, Di Mascio P. Singlet oxygen oxidation of isolated and cellular DNA: Product formation and mechanistic insights. Photochem Photobiol. 2006;82:1219–1225. doi: 10.1562/2006-06-09-IR-914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Davies MJ. Reactive species formed on proteins exposed to singlet oxygen. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2004;3:17–25. doi: 10.1039/b307576c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Girotti AW. Lipid hydroperoxide generation, turnover, and effector action in biological systems. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:1529–1542. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miyamoto S, Martinez GR, Medeiros MH, Di Mascio P. Singlet molecular oxygen generated from lipid hydroperoxides by the Russell mechanism: Studies using 18O-labeled linoleic acid hydroperoxide and monomol light emission measurements. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:6172–6179. doi: 10.1021/ja029115o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dougherty TJ, Gomer CJ, Henderson BW, Jori G, Kessel D, Korbelik M, Moan J, Peng Q. Photodynamic therapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:889–905. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.12.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Oleinick NL, Morris RL, Belichenko I. The role of apoptosis in response to photodynamic therapy: What, where, why, and how. Photochem Photobiol Sci. 2002;1:1–21. doi: 10.1039/b108586g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weishaupt KR, Gomer CJ, Dougherty TJ. Identification of singlet oxygen as the cytotoxic agent in photoinactivation of a murine tumor. Cancer Res. 1976;36:2326–2329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Oleinick NL, Antunez AR, Clay ME, Rihter BD, Kenney ME. New phthalocyanine photosensitizers for photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 1993;57:242–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1993.tb02282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated damage to proteins and its consequences. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2003;305:761–770. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(03)00817-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wright A, Bubb WA, Hawkins CL, Davies MJ. Singlet oxygen-mediated protein oxidation: Evidence for the formation of reactive side chain peroxides on tyrosine residues. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76:35–46. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0035:sompoe>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miki T, Yu L, Yu CA. Hematoporphyrin-promoted photoinactivation of mitochondrial ubiquinol-cytochrome c reductase: Selective destruction of the histidine ligands of the iron-sulfur cluster and protective effect of ubiquinone. Biochemistry. 1991;30:230–238. doi: 10.1021/bi00215a033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tomita M, Irie M, Ukita T. Sensitized photooxidation of histidine and its derivatives. Products and mechanism of the reaction. Biochemistry. 1969;8:5149–5160. doi: 10.1021/bi00840a069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Au V, Madison SA. Effects of singlet oxygen on the extracellular matrix protein collagen: Oxidation of the collagen crosslink histidinohydroxylysinonorleucine and histidine. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2000;384:133–142. doi: 10.1006/abbi.2000.2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kang P, Foote CS. Photosensitized oxidation of 13C,15N-labeled imidazole derivatives. J Am Chem Soc. 2002;124:9629–9638. doi: 10.1021/ja012253d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nakagawa M, Watanabe H, Kodato S, Okajima H, Hino T, Flippen JL, Witkop B. A valid model for the mechanism of oxidation of tryptophan to formylkynurenine-25 years later. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1977;74:4730–4733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.74.11.4730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kukreja RC, Kearns AA, Zweier JL, Kuppusamy P, Hess ML. Singlet oxygen interaction with Ca(2+)-ATPase of cardiac sarcoplasmic reticulum. Circ Res. 1991;69:1003–1014. doi: 10.1161/01.res.69.4.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jori G, Gennari G, Galiazzo G, Scoffone E. Photo-oxidation of horse heart cytochrome c. Evidence for methionine-80 as a heme ligand. FEBS Lett. 1970;6:267–269. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(70)80074-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Trivedi NS, Wang HW, Nieminen AL, Oleinick NL, Izatt JA. Quantitative analysis of Pc 4 localization in mouse lymphoma (ly-r) cells via double-label confocal fluorescence microscopy. Photochem Photobiol. 2000;71:634–639. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2000)071<0634:qaopli>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lam M, Oleinick NL, Nieminen AL. Photodynamic therapy-induced apoptosis in epidermoid carcinoma cells. Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial inner membrane permeabilization. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47379–47386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107678200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Usuda J, Chiu SM, Murphy ES, Lam M, Nieminen AL, Oleinick NL. Domain-dependent photodamage to Bcl-2. A membrane anchorage region is needed to form the target of phthalocyanine photosensitization. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:2021–2029. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M205219200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Morris RL, Azizuddin K, Lam M, Berlin J, Nieminen AL, Kenney ME, Samia AC, Burda C, Oleinick NL. Fluorescence resonance energy transfer reveals a binding site of a photosensitizer for photodynamic therapy. Cancer Res. 2003;63:5194–5197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oleinick NL, Evans HH. The photobiology of photodynamic therapy: Cellular targets and mechanisms. Radiat Res. 1998;150:S146–156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kessel D, Luo Y. Photodynamic therapy: A mitochondrial inducer of apoptosis. Cell Death Differ. 1999;6:28–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Usuda J, Chiu SM, Azizuddin K, Xue LY, Lam M, Nieminen AL, Oleinick NL. Promotion of photodynamic therapy-induced apoptosis by the mitochondrial protein smac/diablo: Dependence on bax. Photochem Photobiol. 2002;76:217–223. doi: 10.1562/0031-8655(2002)076<0217:poptia>2.0.co;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chiu SM, Oleinick NL. Dissociation of mitochondrial depolarization from cytochrome c release during apoptosis induced by photodynamic therapy. Br J Cancer. 2001;84:1099–1106. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xue LY, Chiu SM, Fiebig A, Andrews DW, Oleinick NL. Photodamage to multiple Bcl-xl isoforms by photodynamic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosensitizer Pc 4. Oncogene. 2003;22:9197–9204. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xue LY, Chiu SM, Oleinick NL. Photochemical destruction of the Bcl-2 oncoprotein during photodynamic therapy with the phthalocyanine photosensitizer Pc 4. Oncogene. 2001;20:3420–3427. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Iverson SL, Enoksson M, Gogvadze V, Ott M, Orrenius S. Cardiolipin is not required for bax-mediated cytochrome c release from yeast mitochondria. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:1100–1107. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305020200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vladimirov YA, Proskurnina EV, Izmailov DY, Novikov AA, Brusnichkin AV, Osipov AN, Kagan VE. Cardiolipin activates cytochrome c peroxidase activity since it facilitates H2O2 access to heme. Biochemistry (Mosc) 2006;71:998–1005. doi: 10.1134/s0006297906090082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bayir H, Fadeel B, Palladino MJ, Witasp E, Kurnikov IV, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Amoscato AA, Jiang J, Kochanek PM, DeKosky ST, Greenberger JS, Shvedova AA, Kagan VE. Apoptotic interactions of cytochrome c: Redox flirting with anionic phospholipids within and outside of mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1757:648–659. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chernomorsky S, Wong C, Poretz RD. Pheophorbide a-induced photo-oxidation of cytochrome c: Implication for photodynamic therapy. Photochem Photobiol. 1992;55:205–211. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1992.tb04229.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Giulivi C, Sarcansky M, Rosenfeld E, Boveris A. The photodynamic effect of rose bengal on proteins of the mitochondrial inner membrane. Photochem Photobiol. 1990;52:745–751. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1990.tb08676.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Estevam ML, Nascimento OR, Baptista MS, Di Mascio P, Prado FM, Faljoni-Alario A, Zucchi Mdo R, Nantes IL. Changes in the spin state and reactivity of cytochrome c induced by photochemically generated singlet oxygen and free radicals. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39214–39222. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M402093200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nukuna BN, Sun G, Anderson VE. Hydroxyl radical oxidation of cytochrome-c by aerobic radiolysis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;38:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Deterding LJ, Barr DP, Mason RP, Tomer KB. Characterization of cytochrome c free radical reactions with peptides by mass spectrometry. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:12863–12869. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.21.12863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen YR, Deterding LJ, Sturgeon BE, Tomer KB, Mason RP. Protein oxidation of cytochrome c by reactive halogen species enhances its peroxidase activity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:29781–29791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200709200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Isom AL, Barnes S, Wilson L, Kirk M, Coward L, Darley-Usmar V. Modification of cytochrome c by 4-hydroxy-2-nonenal: Evidence for histidine, lysine, and arginine-aldehyde adducts. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2004;15:1136–1147. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2004.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams MV, Wishnok JS, Tannenbaum SR. Covalent adducts arising from the decomposition products of lipid hydroperoxides in the presence of cytochrome c. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007;20:767–775. doi: 10.1021/tx600289r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Girotti AW. Photosensitized oxidation of membrane lipids: Reaction pathways, cytotoxic effects, and cytoprotective mechanisms. J Photochem Photobiol B. 2001;63:103–113. doi: 10.1016/s1011-1344(01)00207-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Verma A, Schug A, Lee KH, Wenzel W. Basin hopping simulations for all-atom protein folding. J Chem Phys. 2006;124:044515. doi: 10.1063/1.2138030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Li YS, Kenney ME. U.S. Patent 5,763,602. Methods of syntheses of phthalocyanine compounds. 1998

- 44.Adam W, Erden I. Synthesis and characterization of 7-spirocyclopropyl-2,3-dioxabicyclo[2.2.1]hept-5-ene. J Org Chem. 1978;43:2737–2738. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jensen PH, Weilguny D, Matthiesen F, McGuire KA, Shi L, Hojrup P. Characterization of the oligomer structure of recombinant human mannan-binding lectin. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:11043–11051. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M412472200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.He J, Larkin HE, Li YS, Rihter BD, Zaidi SIA, Rodgers MAJ, Mukhtar H, Kenney ME, Oleinick NL. The synthesis, photophysical and photobiological properties and in vitro structure-activity relationships of a set of silicon phthalocyanine PDT photosensitizers. Photochem Photobiol. 1997;65:581–586. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-1097.1997.tb08609.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Anula HM, Berlin Jeffrey C, Wu H, Li YS, Peng X, Kenney Malcolm E, Rodgers Michael AJ. Synthesis and photophysical properties of silicon phthalocyanines with axial siloxy ligands bearing alkylamine termini. J Phys Chem A. 2006;110:5215–5223. doi: 10.1021/jp056279t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chang SH, Teshima GM, Milby T, Gillece-Castro B, Canova-Davis E. Metal-catalyzed photooxidation of histidine in human growth hormone. Anal Biochem. 1997;244:221–227. doi: 10.1006/abio.1996.9899. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Posadaz A, Biasutti A, Casale C, Sanz J, Amat-Guerri F, Garcia NA. Rose bengal-sensitized photooxidation of the dipeptides l-tryptophyl-l-phenylalanine, l-tryptophyl-l-tyrosine and l-tryptophyl-l-tryptophan: Kinetics, mechanism and photoproducts. Photochem Photobiol. 2004;80:132–138. doi: 10.1562/2004-03-03-RA-097.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ray WJ., Jr Photochemical oxidation. Methods Enzymol. 1967;11:490–497. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nukuna BN, Sun G, Anderson VE. Hydroxyl radical oxidation of cytochrome c by aerobic radiolysis. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1203–1213. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kagan VE, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Tyurina YY, Ritov VB, Amoscato AA, Osipov AN, Belikova NA, Kapralov AA, Kini V, Vlasova II, Zhao Q, Zou M, Di P, Svistunenko DA, Kurnikov IV, Borisenko GG. Cytochrome c acts as a cardiolipin oxygenase required for release of proapoptotic factors. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:223–232. doi: 10.1038/nchembio727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kagan VE, Borisenko GG, Tyurina YY, Tyurin VA, Jiang J, Potapovich AI, Kini V, Amoscato AA, Fujii Y. Oxidative lipidomics of apoptosis: Redox catalytic interactions of cytochrome c with cardiolipin and phosphatidylserine. Free Radic Biol Med. 2004;37:1963–1985. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2004.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shi WQ, Hu J, Zhao W, Su XY, Cai H, Zhao YF, Li YM. Identification of radiation-induced cross-linking between thymine and tryptophan by electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry. J Mass Spectrom. 2006;41:1205–1211. doi: 10.1002/jms.1090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kotiaho T, Eberlin MN, Vainiotalo P, Kostiainen R. Electrospray mass and tandem mass spectrometry identification of ozone oxidation products of amino acids and small peptides. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2000;11:526–535. doi: 10.1016/S1044-0305(00)00116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lloyd JA, Spraggins JM, Johnston MV, Laskin J. Peptide ozonolysis: Product structures and relative reactivities for oxidation of tyrosine and histidine residues. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom. 2006;17:1289–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.jasms.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shen HR, Spikes JD, Kopecekova P, Kopecek J. Photodynamic crosslinking of proteins. I. Model studies using histidine- and lysine-containing n-(2-hydroxypropyl)methacrylamide copolymers. J Photochem Photobiol B. 1996;34:203–210. doi: 10.1016/1011-1344(96)07286-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arnbjerg J, Johnsen M, Frederiksen PK, Braslavsky SE, Ogilby PR. Two-photon photosensitized production of singlet oxygen: Optical and optoacoustic characterization of absolute two-photon absorption cross sections for standard sensitizers in different solvents. J Phys Chem A Mol Spectrosc Kinet Environ Gen Theory. 2006;110:7375–7385. doi: 10.1021/jp0609986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nukuna BN. PhD. Case Western Reserve University; Cleveland, OH: 2001. The hydroxyl radical: Its role in oxidative damage and as a biochemical too to probe solvent accessible surfaces. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Qi PX, Beckman RA, Wand AJ. Solution structure of horse heart ferricytochrome c and detection of redox-related structural changes by high-resolution 1H NMR. Biochemistry. 1996;35:12275–12286. doi: 10.1021/bi961042w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Valadon P, Bernstein HJ. La Jolla, CA 92039: 2001. RasTop, 1.3.1. http://www.bernstein-plus-sons.com/software/rastop/RasTop.zip. [Google Scholar]