Abstract

Background

Eating in the absence of hunger (EAH), studied in the context of laboratory paradigms, has been associated with obesity and is predictive of excess weight gain in children. However, no easily administered questionnaire exists to assess for EAH in children.

Objective

We developed an Eating in the Absence of Hunger questionnaire to be administered to children and adolescents (EAH-C) and examined psychometric properties of the measure.

Design

Two-hundred-twenty-six obese (BMI ≥ 95th percentile for age and sex, n = 73) and non-obese (BMI <95th percentile, n = 153) youth (mean age ± SD, 14.4 ± 2.5y) completed the EAH-C and measures of loss of control and emotional eating, and general psychopathology. Temporal stability was assessed in a subset of participants.

Results

Factor analysis generated three subscales for the EAH-C: Negative Affect, External Eating, and Fatigue/Boredom. Internal consistency for all subscales was established (Cronbach's alphas: 0.80 to 0.88). The EAH-C subscales had good convergent validity with emotional eating and loss of control episodes (p's < 0.01). Obese children reported higher Negative Affect subscale scores than non-obese children (p ≤ 0.05). All three subscales were positively correlated with measures of general psychopathology. Intra-class correlation coefficients revealed temporal stability for all subscales (ranging from 0.65 to 0.70, p's < 0.01). We conclude that the EAH-C had internally consistent subscales with good convergent validity and temporal stability, but may have limited discriminant validity. Further investigations examining the EAH-C in relation to laboratory feeding studies are required to determine whether reported EAH is related to actual energy intake or to the development of excess weight gain.

Keywords: Eating in the absence of hunger, obesity, overweight, emotional and external eating, children and adolescents

Introduction

Satiety cues that arise from the gastrointestinal tract are believed to be important in the initiation and termination of eating based upon physiological hunger (Druce & Bloom, 2006). However, because environmental and internal events that are not related to physiological hunger can also trigger eating, children may start to eat, or continue eating, in the absence of physiological hunger. Eating when not physiologically hungry may contribute to excess body weight (Shunk & Birch, 2004).

Eating in the absence of hunger (EAH) was first measured directly among preschool children by determining a child's actual ad libitium energy intake after the child had consumed a meal and reported that he or she was full (J. O. Fisher & Birch, 2002). Using a similar paradigm in a middle childhood sample, Moens and Braet found that obese boys ate more in the absence of hunger compared to non-obese boys. By contrast, non-obese girls were more likely to eat in the absence of hunger than obese girls (Moens & Braet, 2007). Another study examined 5-y-old boys and girls categorized as high versus low risk for obesity based on maternal pre-pregnancy weight status (Faith et al., 2006). EAH was higher among high-risk, compared to low-risk, boys, although no differences were found among girls. In a recent study of 879 Hispanic boys and girls, EAH was suggested to be a heritable trait and positively associated with obesity and fasting levels of insulin and leptin (J. O. Fisher et al., 2007).

In a series of longitudinal studies making use of the same laboratory paradigm, EAH was found to be a stable trait (Birch, Fisher, & Davison, 2003; J. O. Fisher & Birch, 2002) and girls of two obese parents had higher levels of and larger increases in EAH over time (Francis, Ventura, Marini, & Birch, 2007). Although Fisher and colleagues did not find EAH to predict weight gain among Hispanic boys and girls, another study (Shunk & Birch, 2004) did find that EAH was predictive of increased weight gain in Caucasian girls ages 5 to 9y. Although there are limited data on the prevalence of EAH in children, Moens and Braet reported that almost two-thirds of their sample engaged in EAH, and data suggest that EAH increases with age (Birch et al., 2003).

Given the high prevalence of obesity (Ogden et al., 2006), and promising findings that young children may be trained to better regulate food intake (Johnson, 2000), it would be useful for providers working with children to have a readily available tool for assessing EAH. Although some feeding studies have examined child energy intake in relation to parental eating practices (Tanofsky-Kraff, Haynos, Kotler, Yanovski, & Yanovski, 2007), none has explored the immediate factors that may prompt EAH such as children's emotions or environmental cues. Lastly, the EAH feeding paradigm does not offer insight regarding whether some children may continue to eat past satiation during a meal, a situation that might be distinct from the conditions under which a child may initiate eating when not hungry.

We, therefore, aimed to develop a self-report questionnaire to assess pediatric EAH in response to purported precipitants. Although a number of validated measures that assess eating in response to emotional and/or external cues are available in the literature (Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007; T van Strien, Frijters, Bergers, & Defares, 1986; T. van Strien & Oosterveld, 2007; Wardle, Guthrie, Sanderson, & Rapoport, 2001), none query specifically about eating when not hungry. The parent-reported Child Eating Behavior Questionnaire (Wardle et al., 2001) “food responsiveness” scale includes one item that may assess EAH (“even if my child is full up, s/he finds room to eat her/his favorite food”), however none of the other items on any scale is specific to eating when not hungry. Based on literature that suggests both emotional and external cues serve as potential triggers for overeating (T. van Strien, Schippers, & Cox, 1995), we chose to examine each of these constructs in a new questionnaire to assess EAH in children: the EAH-C questionnaire. Emotional eating has been defined as “eating in response to a range of negative emotions such as anxiety, depression, anger, and loneliness to cope with negative affect” (p. 439) (Faith, Allison, & Geliebter, 1997). Eating in response to negative emotions is reportedly common among children (Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007), especially those who are obese (Shapiro et al., 2007), and has been linked to loss of control eating (Shapiro et al., 2007; Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007). Eating in response to external factors, such as the sight, smell, or taste of food, or whether other people are eating, has been less explored. A limited number of feeding studies suggest that children eat more when they have been exposed to food that tastes good (Birch, Johnson, Jones, & Peters, 1993) or when served large portion sizes (J.O. Fisher, Rolls, & Birch, 2003; Rolls, Engell, & Birch, 2000). In one study, a composite score including both emotional and external eating was associated with the odds of EAH, as measured by a laboratory feeding paradigm, in boys and girls (Moens & Braet, 2007).

We hypothesized that a factor analysis of the EAH-C would generate internally consistent scales that would demonstrate good temporal stability. We also posited that the emotional and external EAH-C scales would demonstrate good convergent validity with loss of control eating and emotional eating. Lastly, based upon the literature suggesting an association between EAH and overweight, we hypothesized that obese children would report higher scores on the EAH-C scales than non-obese participants.

Methods

Participants

Children and adolescents (32% obese and 68% non-obese), participating in non-intervention, metabolic studies at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) participated in the study. Sample demographics are presented in Table 1. Recruitment from the vicinity surrounding Bethesda, MD has been described elsewhere (Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004). None of these children was taking medication that might impact body weight, and none was undergoing weight loss treatment. All were aware that they would not receive weight-loss or other treatment as part of the study protocol. Participants had no significant medical disease, and each child had normal hepatic, renal, and thyroid function. Children provided written assent and parents gave written consent for participation in the protocol. This study was approved by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Institutional Review Board, NIH.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Participants.

| Non-obese

(n = 153) |

Obese

(n = 73) |

Probability of difference | p< | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M ± SD | M ± SD | F | ||

|

| ||||

| Age (y), | 14.2 ± 2.5 | 14.9 ± 2.4 | F = 4.1 | 0.05 |

|

| ||||

| BMI z-score, | 0.48 ± .80 | 2.2 ± .40 | F = 30.9 | 0.001 |

|

| ||||

| χ2 | ||||

|

| ||||

| Race (% of group) | ||||

| African American | 24.8 | 41.1 | 4.1 | nsa |

| Asian | 5.9 | 1.4 | ||

| Caucasian | 63.4 | 53.4 | ||

| Hispanic | 3.9 | 1.4 | ||

| Other | 2.0 | 2.7 | ||

|

| ||||

| Sex (%) | ||||

| Female | 52.0 | 56.2 | 0.21 | nsa |

|

| ||||

| SESb (median) | 2.0 | 2.0 | 8.5 | nsa |

ns = non-significant (p > 0.05);

SES = Socioeconomic status (Hollingshead, 1975); lower scores are indicative of higher SES.

Scores generated from the Hollingshead Index are based upon two scales: Occupation (ranging from “1=higher executive, proprietors of large businesses and major professionals” to “7=farm laborers/menial service workers”) and Education (ranging from 1=graduate professional training to 7=less than 7 yrs education). The occupation items are multiplied by 7 and the education scale items are multiplied by 4. The scores are then averaged for both parents and a final scaling is based upon the 1 through 5 variables. Therefore, a child with a score of 2 might have parents who both completed undergraduate college degrees and worked as “administrators, lesser professionals, or proprietors of medium-sized businesses”; One child had a BMI below the 5th percentile. Findings did not differ when this participant was removed from the sample. Therefore, this child's data is included in the analyses presented.

Procedure

Participants completed assessments during an outpatient visit. For the purpose of determining temporal stability, questionnaires were administered a second time in a convenience sample of children who returned to the NIH for another visit.

Questionnaires

The Eating in the Absence of Hunger Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents (EAH-C) is a 14-item measure designed to assess the frequency of precipitants to eating when one is not hungry in 6 to 19 year old youth. The wording and items in the EAH-C were developed based upon the clinical experience of the authors. During the initial administration of the measure, no participants reported difficulty with understanding the instructions and completing the questionnaire. However, for children aged seven and younger (n = 3), and in cases where children had difficulty reading or understanding the questions, trained research assistants read the questions aloud and provided simple alternative definitions for words and statements that were not understood. The five emotional precipitants studied were feeling 1. sad or depressed, 2. angry or frustrated, 3. anxious or nervous, 4. tired, and 5. bored. The two external precipitants examined were 1. sensory cues (food looks, tastes, or smells so good) and 2. social cues (being in the presence of other people who are eating). On the first page of the measure, individuals are queried about times of eating past satiation; the introduction states, “Imagine that you are eating a meal or snack at home, school, or in a restaurant. Imagine that you eat enough of your meal so that you are no longer hungry.” The stem for each of the seven items begins, “In this situation, how often do you keep eating because…” On the second page of the EAH-C, children are queried about times of eating in the absence of hunger; the introduction states, “Now imagine that you finished eating a meal or snack some time ago and you are not yet hungry.” The stem prior to each of the seven items is “In this situation, how often do you start eating because…” Participants selected the frequency with which they eat past satiation and in the absence of hunger, in response to each of the seven cues, on a 5-point Likert scale with answers ranging from “Never” (score of 1) through “Always,” (score of 5) for all 14 questions. Subscales are scored by summing the items loading on each scale.

The Emotional Eating Scale – Adapted for Children and Adolescents (EES-C; (Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007), designed for use with 8-17 y-old children, was adapted from the Emotional Eating Scale for adults (Arnow, Kenardy, & Agras, 1995) and completed by 205 children. The EES-C is a 25-item self-report measure used to assess the urge to cope with negative affect by eating and generates three subscales: 1. depression, 2. anger, anxiety and frustration, and 3. feeling unsettled. Respondents rated their desire to eat in response to each emotion on a 5-point scale (No desire, Small desire, Moderate desire, Strong desire, and Very strong desire to eat). Higher scores indicate a greater reported desire to eat in response to negative mood states. The EES-C subscales have demonstrated very good internal consistency (alphas: 0.83 to 0.95), convergent and discriminant validity, and adequate temporal stability (Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007). The EAH-C emotional items differ from the EES-C in that the former measure only queries about eating in response to negative affect specifically in the absence of hunger.

To assess the presence or absence of loss of control eating episodes, a subset (n=151) of participants were administered the Eating Disorder Examination (EDE; (Fairburn & Cooper, 1993) or the EDE adapted for children (Bryant-Waugh, Cooper, Taylor, & Lask, 1996) by a trained interviewer. The EDE has good inter-rater reliability for all episode types (Spearman correlation coefficients: ≥ 0.70; (Rizvi, Peterson, Crow, & Agras, 2000). Tests of the EDE adapted for children have demonstrated excellent inter-rater reliability (Spearman rank correlations from 0.91-1.0) (Bryant-Waugh et al., 1996; Tanofsky-Kraff et al., 2004).

Based upon studies examining psychometric properties of eating related measures (e.g., (Arnow et al., 1995), we opted to examine symptoms of depression and anxiety to assess discriminant validity. To assess general depressive symptoms, 219 children completed the Children's Depression Inventory (Kovacs, 1992), a 27-item measure used to evaluate depressive symptomatology in children. Internal consistency (alphas) for the Children's Depression Inventory total score ranges from 0.70-0.86 (Kovacs, 1985). Anxiety was measured in 221 children with the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children; (Spielberger, 1973), a 40-item self-report measure of state and trait anxiety developed for use with elementary school children. In a sample of school-aged children, internal consistency for the state scale was good, with alphas of 0.82 for males and 0.87 for females (Spielberger, 1973). Similarly, alphas for the trait anxiety scale were 0.78 and 0.81 for males and females, respectively (Spielberger, 1973).

Physical measures

Weight and height were measured as described previously (Nicholson et al., 2001) using calibrated electronic instruments. BMI standard deviation (BMI-Z) scores were calculated according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 standards (Ogden et al., 2002).

Girls' pubertal breast development was assigned through physical examination by a pediatric endocrinologist or trained pediatric nurse practitioner to one of the five standards of Tanner (Marshall & Tanner, 1969, 1970). Testicular volume (in cc) for boys was also assessed using an orchidometer. Pubertal stage and testicular volume can be considered surrogate measurements of neurocognitive maturity as well as objective measures of physical maturity (Marshall & Tanner, 1969, 1970).

Statistical Analysis

All analyses were conducted using SPSS for Windows, 12.0 (SPSS, 2004). All 14 items from the EAH-C were subjected to a principal components analysis with a varimax rotation and, to confirm the loadings generated, a common factor analysis with a promax rotation to take into account potential correlations between factors. An Eigenvalue criterion of 1 was used. Internal consistency was examined using item-total correlations and Cronbach's alphas are reported. To assess convergent validity, analyses of variance (ANCOVA) with a Bonferroni-Hochberg post hoc correction were used to examine EAH-C scales based on body weight (obese vs. non-obese) and the reported presence or absence of loss of control eating based upon responses to the EDE. Additionally, multiple regressions were used to examine relationships between the EAH-C and EES-C subscales. Since EAH has been shown to increase with age (Birch et al., 2003), age was considered as a covariate in all models. Furthermore, we entered race, socioeconomic status (SES) (Hollingshead, 1975), sex, pubertal stage and BMI-Z score into each complete model, other than weight status in which all covariates but BMI-Z were considered. Non-significant covariates were removed. Means ± standard errors are reported, with means adjusted for ANCOVA models where appropriate. To further assess discriminant validity for both emotional and external triggers, correlations were used to determine whether or not self-reported EAH-C behavior was related to symptoms of depression or anxiety. To assess temporal stability, intra-class correlations were calculated to determine the degree of agreement between first and second administrations of the EAH-C in a subset of the sample. Differences and associations were considered significant when p values were ≤ 0.05.

Results

Factor structure

A range of responses was generated for each item on the Eating in the Absence of Hunger Questionnaire in Children and Adolescents (EAH-C). Responses ranged from 1 to 5 and most medians were 2 or 3. A principal components factor analysis of the EAH-C, including all 14 items, generated three factors that collectively accounted for 65.3% of the variance. The first factor included 6 items, accounting for 28.4% of the variance (Eigenvalue=6.3), and represented EAH in response to feeling sad or depressed, angry or frustrated, and anxious or nervous (EAH-C Negative Affect Eating). Four items comprised the second factor, which was related to EAH when the food looks, tastes or smells so good and when others are eating (EAH-C External Eating). This factor accounted for 19.8% of the variance (Eigenvalue=1.6). The third factor also consisted of four items (17.1% of the variance; Eigenvalue=1.3) and represented EAH when feeling tired and bored (EAH-C Fatigue/Boredom Eating); Table 2. Identical subscales were generated by a common factor analysis: Negative Affect scale: Eigenvalue=6.2, 41.9% of the variance; External Eating scale: Eigenvalue=1.6, 8.3% variance; and Fatigue/Boredom scale Eigenvalue=1.3, 6.3% variance. All three subscales demonstrated good internal consistency; Cronbach's alphas for the EAH-C Negative Affect, EAH-C External Eating, and EAH-C Fatigue/Boredom subscales were 0.88, 0.80, and 0.83, respectively.

Table 2.

Factor Loadings for the EAH-C.

| Factor Loadings | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1

Negative Affect |

Factor 2

External |

Factor 3

Fatigue/Boredom |

|

| Keep eating because: | |||

| Food looks, tastes or smells so good | 0.18 | 0.77 | 0.06 |

| Others are still eating | 0.20 | 0.78 | 0.05 |

| Feeling sad or Depressed | 0.81 | 0.16 | 0.05 |

| Feeling bored | 0.49 | 0.43 | 0.47 |

| Feeling angry or Frustrated | 0.74 | 0.13 | 0.17 |

| Feeling tired | 0.12 | 0.15 | 0.86 |

| Feeling anxious or Nervous | 0.61 | 0.30 | 0.17 |

| Start eating Because: | |||

| Food looks, tastes or smells so good | 0.25 | 0.72 | 0.26 |

| Others are still eating | 0.15 | 0.71 | 0.28 |

| Feeling sad or Depressed | 0.86 | 0.20 | 0.11 |

| Feeling bored | 0.45 | 0.31 | 0.60 |

| Feeling angry or Frustrated | 0.72 | 0.18 | 0.24 |

| Feeling tired | 0.19 | 0.13 | 0.86 |

| Feeling anxious or Nervous | 0.71 | 0.16 | 0.18 |

| Variances account for (%) | 28.4 | 19.8 | 17.1 |

Note. Rotated component matrix. Bolded correlations indicate the item loadings for each factor.

Convergent and discriminant validity

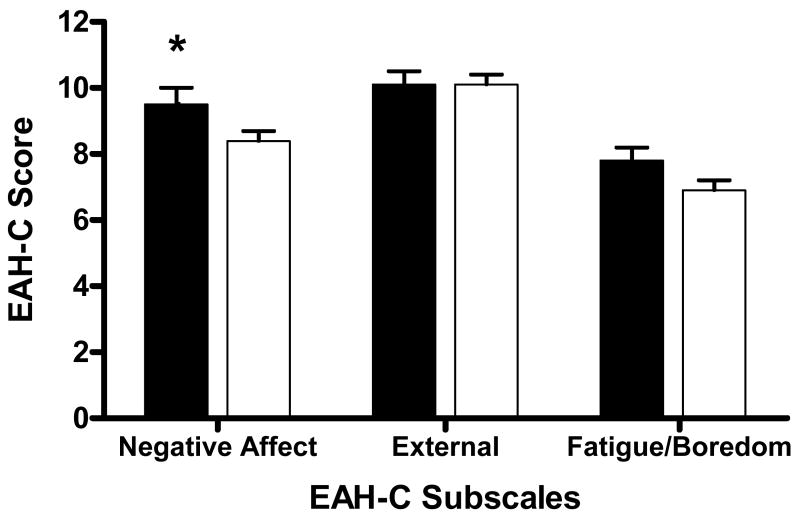

After accounting for the contribution of sex, age and SES, obese children had significantly higher EAH-C Negative Affect subscales scores compared to non-obese children [F(1, 216) = 3.82, p ≤ 0.05]. A similar, but non-significant pattern was found between obese and non-obese children for the Fatigue/Boredom scale, after controlling for race [F(1, 217) = 6.60, p < 0.06]. Controlling for age and SES, no differences were found on the External Eating subscale based upon body weight [F(1, 217) = 0.02, p < 0.1.0; Figure 1].

Figure 1.

Obese participants reported significantly higher EAH-C Negative Affect (p ≤ 0.05), but not External Eating (p > 0.1), or Fatigue/Boredom (p < 0.06) subscales compared to non-obese children. *p ≤ 0.05. Bar key: Filled = obese and Open = non-obese.

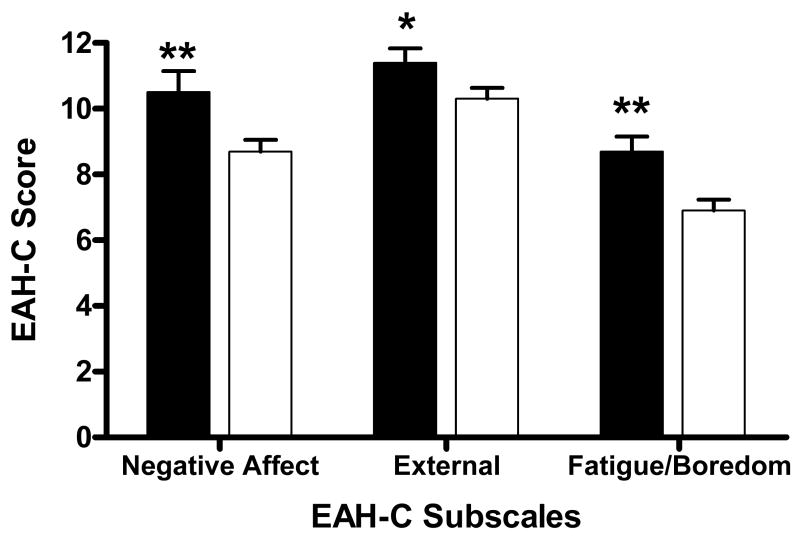

Participants endorsing loss of control (n=44) during the EDE interview had significantly higher scores on the EAH-C Negative Affect [F(1, 150) = 7.09, p < 0.01], External Eating [F(1, 150) = 4.07, p < 0.05] , and Fatigue/Boredom [F(1, 150) = 8.45, p < 0.01] scales compared to those without loss of control (n=107), suggesting that the subscales demonstrated good convergent validity with loss of control eating (Figure 2). Moreover, all three EAH-C subscales were positively correlated with all EES-C subscales (p's < 0.01; Table 3), indicative of good construct validity. All correlations remained positively significant for boys and girls separately, and for the non-obese children. For the obese children, the correlation between the EAH-C Boredom/Fatigue scale and the EES-C Anger, Anxiety and Frustration scale became a trend (r = 0.23, p = 0.06); all other relationships remained significantly related for the obese children. All positive relationships also remained significant when analyzing Caucasian and African American children separately, except for the EAH-C Boredom/Fatigue subscale which was unrelated to the EES-C Anger, Anxiety and Frustration scale (r = 0.21, p = 0.10) for African American participants only.

Figure 2.

Participants endorsing loss of control reported significantly higher EAH-C Negative Affect (p < 0.01), External Eating (p < 0.05), and Fatigue/Boredom (p < 0.01) subscales compared to those without loss of control. *p<0.05; **p<0.01. Bar key: Filled = loss of control and Open = no loss of control.

Table 3.

Product-moment correlation coefficients between the EAH-C Negative Affect, External and Fatigue/Boredom subscales and the EES-C Depression, Anger, Anxiety and Frustration, and Unsettled subscales, the Children's Depression Inventory, and the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children Trait and State Anxiety subscales.

| Eating in the Absence of Hunger Questionnaire for Children and Adolescents | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Negative Affect | External | Fatigue/Boredom | |

| Emotional Eating Scale for Children | |||

| Depression | 0.61 | 0.48 | 0.52 |

| Anger, Anxiety, Frustration | 0.48 | 0.37 | 0.27 |

| Unsettled | 0.49 | 0.42 | 0.39 |

| Children's Depression Inventory Total Score | 0.34 | 0.26 | 0.23 |

| State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Children | |||

| Trait Anxiety | 0.37 | 0.33 | 0.25 |

| State Anxiety | 0.32 | 0.24 | 0.26 |

Note. All p's < 0.01. EAH-C = Eating in the Absence of Hunger Questionnaire; EES-C = Emotional Eating Scale Adapted for Children and Adolescents (n = 205). Children's Depression Inventory (n = 219). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (n = 221). Correlations involving the Negative Affect and External Eating subscales are controlled for sex and SES, respectively.

All three EAH-C subscales were also positively related with the Children's Depression Inventory total score as well as state and trait anxiety (p's < 0.01; Table 3). Higher EAH-C scores were associated with more symptoms of depression and anxiety. When analyzing the children separately based upon sex, all relationships remained positively significant for the girls. However, for the boys, the EAH-C Boredom/Fatigue scale discriminated from depressive symptoms (r = 0.13, p = 0.20), and the EAH-C External scale was unassociated with state anxiety (r = 0.05, p = 0.67) and depressive symptoms (r = 0.12, p = 0.25). Further, while all relationships remained significant and positive for the non-obese children, for the obese participants, correlations for the EAH-C External (r = 0.23, p = 0.06) and Boredom/Fatigue (r = 0.22, p = 0.07) scales with depressive symptoms became trends. The EAH-C External scale discriminated from trait anxiety for the obese children only (r = 0.08, p = 0.49). We also examined Caucasian and African American children separately. Findings remained the same for Caucasian children as compared to the entire sample. However, for African American participants, the EAH-C Negative Affect (r = 0.11, p = 0.38) and External (r = 0.16, p = 0.20) scales discriminated from state anxiety.

Given the wide age range of our sample, we conducted a second set of analyses examining the 37 younger (≤12y) and 189 older (>12y) children separately. Examining the younger group, the 30 non-overweight participants did not differ from the seven overweight children with regard to their EAH-C scores (p > 0.1 in all cases). After controlling for sex, younger children with loss of control (9.5 ± 3.6) had significantly higher EAH-C Fatigue/Boredom scores compared to those without loss of control (5.8 ± 2.1); [F (1, 19) = 9.85, p < 0.01]. No differences were found based upon loss of control status for the other EAH-C subscales (p > 0.4 in all cases). By contrast, all three EAH-C subscales positively correlated with the three EES-C scales (r's: 0.40-0.67, p < 0.05 in all cases). The EAH-C Negative Affect scale was positively related to trait anxiety (r = 0.34, p ≤ 0.05) and depressive symptoms (r = 0.40, p < 0.05); the EAH-C Fatigue/Boredom subscale positively correlated with depressive symptoms (r = 0.55, p < 0.01); and the External Eating subscale was positively related to trait anxiety (r = 0.48, p<0.01) and depressive symptoms (0.38, p < 0.05). Results from the older participants did not differ considerably from those of the entire sample.

Temporal stability

To assess the stability of the EAH-C, a convenience sample of 115 children completed the measure a second time during their next scheduled visit to the NIH. The average interval period between the two administrations was varied: 150 (SD: 130) days ranging between 5 and 565 days. Intra-class correlations demonstrated good agreement between the first and second administrations of the questionnaire; scores for the EAH-C Negative Affect (0.65), EAH-C Fatigue/Boredom subscale (0.70), and the EAH-C External Eating subscale (0.69) were all significantly correlated (p < 0.01 in all cases). After accounting for length of interval between administrations, correlations for all three scales remained significant at p < 0.01.

Discussion

The purpose of this investigation was to examine the psychometric properties of a newly developed questionnaire designed to assess eating in the absence of hunger. We found that internal consistency was very good for all three subscales of the EAH-C. The Negative Affect scale was associated with body weight, and a trend was found for obese children to report higher Fatigue/Boredom subscale scores compared to non-obese participants. All three subscales demonstrated good convergent validity with loss of control eating and emotional eating. The subscales, however, showed questionable discriminant validity in that all scales correlated with symptoms of depression and anxiety.

Children in our sample appeared able to differentiate between eating in response to high affect emotions, low affect (feeling bored or tired) emotions, and eating when cued by external circumstances. That separate low- and high-affect subscales were interpretable for children is supported by prior data suggesting that children are able to identify the type of emotions they are feeling prior to eating (Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007). Scores from the Negative Affect subscale were higher in obese than non-obese children, and scores trended toward significance for the Fatigue/Boredom subscale. However, no differences were found with regard to the EAH-C External Eating subscale based upon weight status. Based upon data from our sample, EAH in response to emotional, as opposed to external, cues may show a greater association with excess body weight. Since pediatric overweight is associated with teasing, peer victimization, and marginalization (Hayden-Wade et al., 2005; Pearce, Boergers, & Prinstein, 2002; Strauss & Pollack, 2003), heavier children may be more likely than non-overweight children to eat in response to negative emotions induced by poor social functioning. Prospective data are required to determine whether self-reported EAH in response to external and emotional cues converges with actual eating during laboratory test meals and thus put youth at greater risk for excessive weight gain.

The finding that children who endorsed loss of control over eating reported higher EAH-C subscale scores is reflective of good convergent validity. Further, this result supports prior research reporting a relationship between loss of control eating and emotional eating (Goossens, Braet, & Decaluwe, 2007; Shapiro et al., 2007; Tanofsky-Kraff, Theim et al., 2007). All three subscales were also correlated with measures of depressive symptoms and anxiety which may suggest a lack of discriminant validity for the measure. Alternatively, questionable discriminant validity may reflect that children who report eating when not hungry may concurrently struggle with greater general distress; the demonstrated relationships between the EAH-C and general psychopathology may represent a co-occurrence of these behaviors, as opposed to poor discriminant validity. Indeed, empirical data support a relationship between disturbed eating and general psychopathology (e.g., (Goossens et al., 2007; Morgan et al., 2002; Tanofsky-Kraff, Faden, Yanovski, Wilfley, & Yanovski, 2005). Future research utilizing laboratory test meals similar to Birch and colleagues' paradigm (J. O. Fisher & Birch, 2002) is needed to determine whether EAH-C scores relate better to actual eating behavior than do measures of depression and anxiety.

Strengths of the present study include the relatively large sample size, the inclusion of only non-treatment-seeking children and adolescents as participants, and the representation of both Caucasian and African American youth and both sexes. Since differences resulting from subgroup analyses were few compared to those generated by the entire sample, our findings may be generalizable to diverse groups of children. However, the present study is limited in that participants were not recruited in a population-based fashion. Families in the studied sample chose to respond to our notices and thus may be more health-conscious than the general population, possibly limiting the external validity of the study. The EAH-C does not query about EAH in response to positive emotions. Although it is likely that the EAH-C External scale captured times of eating during parties, celebrations, and other social events that involve positive emotions while being exposed to palatable foods, the lack of a specific item in the measure may be a limitation of the present study. In addition, our findings did not fully replicate when examining only the younger children. Since our sample of children aged 12y and younger was small (n=37), studies of the EAH-C in larger samples of middle childhood participants are required. Lastly, given that some data suggest a relationship between mood problems and body weight, the use of anxiety and depressive symptoms for the assessment of discriminant validity may have limited our findings.

Further research is required to fully validate the EAH-C. Specifically, an exploration of eating in the absence of hunger in relationship to laboratory feeding paradigms is required. If increased scores on the EAH-C demonstrate an association with food intake during laboratory studies, and prove predictive of subsequent weight gain, this new measure has the potential to serve as an easily administered assessment to identify, and intervene with, children at risk for obesity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, grant ZO1-HD-00641 (NICHD, NIH) to Dr. J. Yanovski and grant HD042169 (NICHD, NIH) to Dr. M. Faith. J. Yanovski is a Commissioned Officer in the United States Public Health Service, DHHS. Portions of this manuscript were presented at the 2007 Academy of Eating Disorders' Annual Meeting.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Arnow B, Kenardy J, Agras WS. The Emotional Eating Scale: the development of a measure to assess coping with negative affect by eating. Int J Eat Disord. 1995;18(1):79–90. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199507)18:1<79::aid-eat2260180109>3.0.co;2-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Fisher JO, Davison KK. Learning to overeat: Maternal use of restrictive feeding practices promotes girls' eating in the absence of hunger. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;78(2):215–220. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/78.2.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birch LL, Johnson SL, Jones MB, Peters JC. Effects of a nonenergy fat substitute on children's energy and macronutrient intake. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;58(3):326–333. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/58.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Waugh RJ, Cooper PJ, Taylor CL, Lask BD. The use of the eating disorder examination with children: A pilot study. Int J Eat Disord. 1996;19(4):391–397. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-108X(199605)19:4<391::AID-EAT6>3.0.CO;2-G. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Druce M, Bloom SR. The regulation of appetite. Arch Dis Child. 2006;91(2):183–187. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.073759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C, Cooper Z. The Eating Disorder Examination. In: Fairburn C, Wilson G, editors. Binge eating, nature, assessment and treatment. 12th. New York: Guilford; 1993. pp. 317–360. [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Allison DB, Geliebter A. Emotional Eating and Obesity: Theorectical Considerations and Practical Recommendations. In: Dalton S, editor. Obesity and Weight Control: The Health Professional's Guide to Understanding and Treatment. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen; 1997. pp. 439–465. [Google Scholar]

- Faith MS, Berkowitz RI, Stallings VA, Kerns J, Storey M, Stunkard AJ. Eating in the absence of hunger: a genetic marker for childhood obesity in prepubertal boys? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2006;14(1):131–138. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Birch LL. Eating in the absence of hunger and overweight in girls from 5 to 7 y of age. Am J Clin Nutr. 2002;76(1):226–231. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.1.226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Cai G, Jaramillo SJ, Cole SA, Comuzzie AG, Butte NF. Heritability of hyperphagic eating behavior and appetite-related hormones among Hispanic children. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(6):1484–1495. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher JO, Rolls BJ, Birch LL. Children's bite size and intake of an entreé are greater with large portions than with age-appropriate or self-selected portions. Am J Clin Nutr. 2003;77:1164–1170. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/77.5.1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis LA, Ventura AK, Marini M, Birch LL. Parent overweight predicts daughters' increase in BMI and disinhibited overeating from 5 to 13 years. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15(6):1544–1553. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens L, Braet C, Decaluwe V. Loss of control over eating in obese youngsters. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(1):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayden-Wade HA, Stein RI, Ghaderi A, Saelens BE, Zabinski MF, Wilfley DE. Prevalence, characteristics, and correlates of teasing experiences among overweight children vs. non-overweight peers. Obes Res. 2005;13(8):1381–1392. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. Four factor index of social status. Yale University; New Haven: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson SL. Improving Preschoolers' self-regulation of energy intake. Pediatrics. 2000;106(6):1429–1435. doi: 10.1542/peds.106.6.1429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. The Children's Depression, Inventory (CDI) Psychopharmacol Bull. 1985;21(4):995–998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs M. Children's Depression Inventory (CDI) Manual. Multi-Health Systems, Inc.; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291–303. doi: 10.1136/adc.44.235.291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45(239):13–23. doi: 10.1136/adc.45.239.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moens E, Braet C. Predictors of disinhibited eating in children with and without overweight. Behav Res Ther. 2007;45(6):1357–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2006.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan CM, Yanovski SZ, Nguyen TT, McDuffie J, Sebring NG, Jorge MR, et al. Loss of control over eating, adiposity, and psychopathology in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;31(4):430–441. doi: 10.1002/eat.10038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson JC, McDuffie JR, Bonat SH, Russell DL, Boyce KA, McCann S, et al. Estimation of body fatness by air displacement plethysmography in African American and white children. Pediatr Res. 2001;50(4):467–473. doi: 10.1203/00006450-200110000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Curtin LR, McDowell MA, Tabak CJ, Flegal KM. Prevalence of overweight and obesity in the United States, 1999-2004. J Am Med Assoc. 2006;295(13):1549–1555. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.13.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Kuczmarski RJ, Flegal KM, Mei Z, Guo S, Wei R, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2000 growth charts for the United States: Improvements to the 1977 National Center for Health Statistics version. Pediatrics. 2002;109(1):45–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.1.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MJ, Boergers J, Prinstein MJ. Adolescent obesity, overt and relational peer victimization, and romantic relationships. Obes Res. 2002;10(5):386–393. doi: 10.1038/oby.2002.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizvi SL, Peterson CB, Crow SJ, Agras WS. Test-retest reliability of the eating disorder examination. Int J Eat Disord. 2000;28(3):311–316. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(200011)28:3<311::aid-eat8>3.0.co;2-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls BJ, Engell D, Birch LL. Serving portion size influences 5-year-old but not 3-year-old children's food intakes. J Am Diet Assoc. 2000;100(2):232–234. doi: 10.1016/S0002-8223(00)00070-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro JR, Woolson SL, Hamer RM, Kalarchian MA, Marcus MD, Bulik CM. Evaluating binge eating disorder in children: Development of the children's binge eating disorder scale (C-BEDS) Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(1):82–89. doi: 10.1002/eat.20318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shunk JA, Birch LL. Girls at risk for overweight at age 5 are at risk for dietary restraint, disinhibited overeating, weight concerns, and greater weight gain from 5 to 9 years. J Am Diet Assoc. 2004;104(7):1120–1126. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2004.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Edwards CD, Lushene RE, Montuori J, Platzek D. STAIC preliminary manual. Palo Alto, CA: Consulting Psychologist Press; 1973. [Google Scholar]

- SPSS. (2004). Chicago, IL: SPSS, Inc.

- Strauss RS, Pollack HA. Social marginalization of overweight children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2003;157(8):746–752. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.157.8.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Faden D, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Yanovski JA. The perceived onset of dieting and loss of control eating behaviors in overweight children. Int J Eat Disord. 2005;38(2):112–122. doi: 10.1002/eat.20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Haynos AF, Kotler LA, Yanovski SZ, Yanovski JA. Laboratory-based studies of eating among children and adolescents. Curr Nut Food Sci. 2007;3(1):55–74. doi: 10.2174/1573401310703010055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Theim KR, Yanovski SZ, Bassett AM, Burns NP, Ranzenhofer LM, et al. Validation of the emotional eating scale adapted for use in children and adolescents (EES-C) Int J Eat Disord. 2007;40(3):232–240. doi: 10.1002/eat.20362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanofsky-Kraff M, Yanovski SZ, Wilfley DE, Marmarosh C, Morgan CM, Yanovski JA. Eating-disordered behaviors, body fat, and psychopathology in overweight and normal-weight children. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2004;72(1):53–61. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.72.1.53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien T, Frijters J, Bergers G, Defares P. The Dutch Eating Behaviour Questionnaire for assessment of restrained, emotional and external eating behaviour. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:295–315. [Google Scholar]

- van Strien T, Oosterveld P. The children's DEBQ for assessment of restrained, emotional, and external eating in 7- to 12-year-old children. Int J Eat Disord. 2007 doi: 10.1002/eat.20424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Strien T, Schippers GM, Cox WM. On the relationship between emotional and external eating behavior. Addict Behav. 1995;20(5):585–594. doi: 10.1016/0306-4603(95)00018-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wardle J, Guthrie CA, Sanderson S, Rapoport L. Development of the Children's Eating Behaviour Questionnaire. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2001;42(7):963–970. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]