Abstract

We observed that treatment of prostate cancer cells for 24 h with wogonin, a naturally occurring monoflavonoid, induced cell death in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Exposure of wogonin to LNCaP cells was associated with increased intracellular levels of p21Cip-1, p27Kip-1, p53, and PUMA, oligomerization of Bax, release of cytochrome c from the mitochondria, and activation of caspases. We also confirmed the role of p53 by noting that knock-in in p53 expression by transfecting p53 DNA increased wogonin-induced apoptosis in p53-null PC-3 cells. To study the mechanism of PUMA upregulation, we determined the activities of PUMA promoter in the wogonin treated and untreated cells. Increase of the intracellular levels of PUMA protein was due to increase in transcriptional activity. Data from chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analyses revealed that wogonin activated the transcription factor p53 binding activity to the PUMA promoter region. We observed that the upregulation of PUMA mediated wogonin cytotoxicity. Further characterization of the transcriptional response to wogonin in HCT116 human colon cancer cells demonstrated that PUMA induction was p53-dependent; deficiency in either p53 or PUMA significantly protected HCT116 cells against wogonin-induced apoptosis. Also, wogonin promoted mitochondrial translocation and multimerization of Bax. Interestingly, wogonin (100 μM) treatment did not affect the viability of normal human prostate epithelial cells (PrEC). Taken together, these results indicate that p53-dependent transcriptional induction of PUMA and oligomerization of Bax play important roles in the sensitivity of cancer cells to apoptosis induced by caspase activation through wogonin.

Keywords: Wogonin, apoptosis, p53, PUMA, Bax

1. Introduction

Prostate cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer in men and is the second leading cause of cancer-related deaths in North America [1, 2]. Current therapies, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy, are of limited efficacy, especially in advanced disease, and metastatic disease remains incurable [3, 4]. The use of naturally occurring dietary agents is becoming increasingly appreciated as an effective means of managing many types of cancer in an approach known as cancer chemoprevention. Cancer chemoprevention is a means of cancer control in which a malignancy is prevented or reversed by pharmacologic intervention with naturally occurring and/or synthetic agents [5, 6]. One of the most desirable goals in cancer chemoprevention is the identification of natural agents with demonstrable efficacy against defined molecular targets. In contrast to the high incidence of prostate cancer in North America, the incidence of this disease in East Asia is very low [7, 8]. The low incidence of prostate cancer in Asian men has been attributed to the dietary consumption of large amounts of plant-based foods rich in phytochemicals [9-11]. Because of these observations, nutritional supplements such as soybean, garlic, and green tea, which are rich in polyphenolic compounds, have been used to augment anticancer therapies [12, 13].

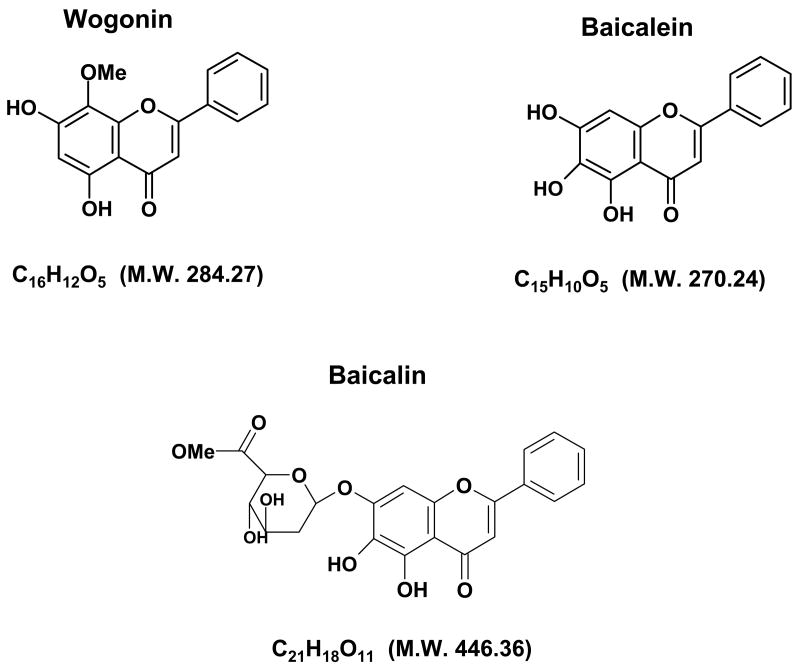

Scutellaria baicalensis Georgi (Huang Qui) is a medicinal herb widely used for the treatment of various inflammatory diseases, hepatitis, tumors, allergic reactions, and diarrhea in East Asian countries including China, Korea, Taiwan, and Japan [14]. The plant has been reported to contain a large number of flavonoids, frequently found as glucosides and other constituents, including phenethyl alcohols, sterols, and essential oils and amino acids. Its components wogonin, baicalin, and baicalein have been studied. Wogonin (C16H12O5, Fig. 1), [15] one of the main active compounds of Scutellaria baicalensis, is known to exert potent anti-inflammatory activities in vitro as well as in vivo [16]. Recently, some reports indicated that wogonin significantly inhibited human ovarian cancer cell A2780, human promyeloleukemic cell HL-60, and human hepatocellular carcinoma cell SK-HEP-1 [17-19]. However, knowledge of the molecular mechanisms of wogonin-induced apoptosis remains to be delineated. Our study was undertaken to evaluate the ability of wogonin to induce apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma LNCaP and human colon carcinoma HCT116 cells, and investigate the probable apoptotic molecular mechanisms used in these processes.

Fig. 1. Chemical structures of baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin.

Apoptosis, a goal of cancer treatment, is characterized by the cell shrinkage, blebbing of the plasma membrane, and chromatin condensation that are associated with cleavage of DNA into ladders [20, 21]. However, in response to some effective therapeutic treatments, decreased ability to undergo apoptosis occurred in human malignant tumor cells [22, 23]. Therefore, further development of agents that can induce or enhance the extent of apoptosis seems to be a promising strategy in the treatment of cancer. The study of apoptosis reveals that many oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes are involved in mediating apoptosis. Tumor suppressor gene p53 is one of the critical genes. It regulates the onset of DNA replication at the G1/S boundary. Its tumor suppressor protein p53 plays an important role in the cell, preventing damaged or otherwise abnormal cells from becoming malignant [24]. Previous studies have demonstrated that both p53-dependent and p53-independent apoptoses were detected in tumor cells in response to apoptosis inducers [25, 26]. In humans, p53 is either mutated or inactivated in at least 50% of tumors [27] and loss of wild-type p53 function can lead to tumor development. p53 is activated through its transcription factor [28] under a variety of stresses, including DNA damage [29, 30]. In response to such stresses, p53 is stabilized and activated such that it binds to specific DNA sequences, ultimately driving the transcription of genes involved in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis [20, 31]. In addition, numerous p53-dependent target genes that play a role as downstream effectors of p53 function have been identified. For example, the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21Cip-1 is a direct p53 target and deletion of this gene reduces the cell cycle arrest response to p53 [32]. However, the importance of p21Cip-1 in p53-dependent and/or p53–independent apoptosis is still not clearly defined. The use of p53 as a target for cancer therapy is being pursued; various therapeutic rationales targeting p53 are currently under investigation including attempts to activate p53. This approach is based on the concept that activation of p53 in a tumor is cytotoxic. So far, many researchers have pursued the use of small molecules to activate p53, the advantages being the potential for large-scale chemical synthesis, easier delivery in vivo, and the currant existence of cell-based assay systems which have been developed to screen p53 regulating small molecules [33]. Other apoptosis enhancing tumor suppressor genes include Bcl-2 family members which, similar to p53, play a pivotal role in the intrinsic apoptotic cascade [34-36]. We investigated the role of PUMA (p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis), a BH-3only Bcl-2 family member, in wogonin-induced apoptosis. PUMA is a downstream target of p53 [37, 38]. PUMA is localized in the mitochondrial membrane and interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL through a BH3 domain. When apoptotic stimuli induce PUMA expression, PUMA binds to Bcl-xL, releasing Bax [39], Bax translocates to the mitochondrial membrane, binds cytochrome c, and multimerizes Apaf-1 [40, 41] to play an important role in stress-induced apoptosis [42, 43]. The balance between p21Cip-1 and PUMA is pivotal in determining whether the cells undergo the cycle arrest response to p53 which mediates apoptosis in human cancer.

Our results provide molecular evidence to demonstrate that wogonin effectively induces apoptosis in human prostate carcinoma LNCaP and human colon carcinoma HCT116 cells; interestingly, we found that wogonin enhances not only the expression of tumor suppressor protein p53, but also the expression of its targets, cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) inhibitors p21Cip-1 and p27Kip-1 as well as the pro-apoptotic protein PUMA. We also demonstrated that wogonin-induced apoptosis is mediated by the p53-PUMA-Bax-cytochrome c-caspase 9-caspase 3 pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2. 1. Reagents and Antibodies

Wogonin, baicalin, and baicalein (>99% pure) were obtained from Wako Chemical Co. (San Francisco, CA, USA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-caspase-3 antibody, anti-poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase-1 (PARP-1) antibody, anti-Bcl-xL antibody and anti-p53 antibody were purchased from Santa Cruz (Santa Cruz, CA, USA). Anti-caspase-8, anti-phospho-Ser473 Akt, anti-Akt, anti-PUMA, anti-p21Cip1, anti-p27Kip-1 and anti-Bax antibodies were from Cell Signaling (Beverly, MA, USA). Monoclonal antibodies were purchased from the each of following companies: anti-caspase-9 antibody from Upstate Biotechnology (Lake Placid, NY, USA), anti-cytochrome c from PharMingen (San Diego, CA, USA) and anti-actin antibody from ICN (Costa Mesa, CA, USA).

2. 2. Cell cultures

Human prostate carcinoma LNCaP and PC3 cells were obtained from ATCC (Manassas, VA, USA) cultured in RPMI-1640 medium (Gibco BRL) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone, Logan, Utah, USA) and 26 mM sodium bicarbonate for monolayer cell culture.

Primary cultures of normal human prostate epithelial cells (PrEC) were purchased from Cambrex Bio Science Walkersville (Cambrex Corporation; East Rutherford, NJ), cultivated in PrEBM™(Prostate Epithelial Cell Basal Medium; Cambrex) and supplemented with PrEGM SingleQuots® (bovine pituitary extract, hydrocortisone, hEGF, epinephrine, transferrin, insulin, retinoic acid, triiodothyronine, and gentamicin; Cambrex). Cells were maintained in accordance with manufacturer's instructions (Clonetics™ Prostate Epithelial Cell System).

p53-containing (p53+/+) and p53-deficient (p53-/-) HCT116, PUMA-containing (PUMA+/+) and PUMA-deficient (PUMA-/-) HCT116, and Bax-containing (Bax+/-) and Bax-deficient (Bax-/-) HCT116 human colon carcinoma cell lines were kindly provided by Dr. Bert Vogelstein (Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD, USA). These cell lines were cultured in McCoy's 5A medium (Gibco-BRL, Gaithersburg, MD, USA) containing 10% fetal bovine serum and antibiotics. The dishes containing cells were kept in a 37°C humidified incubator with 5% CO2.

2. 3. Drug treatment

Wogonin, baicalin, and baicalein (dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO)) were used for the treatment of cells. The final concentration of DMSO used was 0.1% (v/v) for each treatment. For dose-dependent studies, cells were treated with wogonin at 10-100 μM final concentrations for 24 h in complete cell medium. Control cells were treated with vehicle alone.

2. 4. Determination of cell viability

One or two days prior to the experiment, cells were plated into 60-mm dishes at a density of 1 × 105 cells/plate in 5 ml tissue culture medium in triplicate. For trypan blue exclusion assay [84], trypsinized cells were pelleted and resuspended in 0.2 ml of medium, 0.5 ml of 0.4% trypan blue solution and 0.3 ml of phosphate-buffered saline solution (PBS). The samples were mixed thoroughly, incubated at room temperature for 15 min, and examined under a light microscope. At least 300 cells were counted for each survival determination.

2. 5. DNA fragmentation

The pattern of DNA cleavage was analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis. Briefly, the cell pellets were resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0; 25 mM EDTA; 0.5% SDS, 100 mM NaCl, and 200 μg/mL proteinase K) and incubated at 55°C for 2 h. The cell lysate was extracted with phenol/chloroform/isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1, v/v) and then centrifuged for 15 min. The supernatant was incubated with RNase A (0.2 μg//mL) at 37°C. After 1 h, the DNA was extracted with phenol and precipitated with one-tenth the volume of 3 M sodium acetate and 3 volumes of 100% ethanol. The DNA samples, dissolved in 1× TE buffer, were separated by horizontal electrophoresis on 1.8% agarose gels, stained with EtBr, and visualized under UV light.

2. 6. Transfection

In order to generate p53 overexpressing PC3 cells, cells were transfected with 2 μg of pcDNA3-neo or pcDNA3-Flag-p53, which were kindly provided by Dr. Roberts TM (University of Harvard, Boston, MA, USA), using LipofectAMINE Plus (Gibco-BRL Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY, USA). The expression level was determined by immunoblot analysis.

2. 7. Measurement of cytochrome c release

To determine the release of cytochrome c from mitochondria, subconfluent LNCaP cells were grown in 100-mm dishes. Cells were treated with wogonin (100 μM) for 24 h. Using Mitochondrial Fractionation Kit (Active Motif, Carlsbad, CA, USA), mitochondria and cytosol fractions were prepared from treated cells from instructions and reagents included in the kit.

2. 8. Bax oligomerization

To detect the formation of Bax multimeric complexes, aliquots of isolated mitochondrial fractions and cytosolic fractions were cross linked with 1 mM dithiobis (succinimidyl propionate) (Pierce, Rockford, Illinois, USA) at 37°C for 30 min. DMSO alone was used as the control. The cross linked samples were then centrifuged at 13,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. After the supernatant was removed, the pellet was washed once with homogenization buffer (sucrose 0.25 M, HEPES pH 7.4 10 mM, EGTA 1 mM) and lysed with 2 × native sample buffer. Samples were subjected to sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)- polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) under non-denaturing conditions followed by immunoblotting for Bax.

2. 9. Immunoblot analysis

Cells were lysed with 1 × Laemmli lysis buffer (2.4 M glycerol, 0.14 M Tris, pH 6.8, 0.21 M SDS, and 0.3 mM bromophenol blue) and boiled for 7 min. Protein content was measured with BCA Protein Assay Reagent (Pierce, Rockford, IL, USA). The samples were diluted with 1 × lysis buffer containing 1.28 M β-mercaptoethanol, and equal amounts of protein were loaded on 8-12% SDS-polyacrylamide gels. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed according to Laemmli [45] using a Hoefer gel apparatus. Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membrane. The nitrocellulose membrane was blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in PBS-Tween-20 (0.1%, v/v) for 1 h. The membrane was incubated with primary antibody (diluted according to the manufacturer's instructions) at 4°C overnight. Horseradish peroxidase conjugated anti-rabbit or anti-mouse IgG was used as the secondary antibody. Immunoreactive protein was visualized by the chemiluminescence protocol (ECL, Amersham, Arlington Heights, IL, USA). To ensure equal protein loading, each membrane was stripped and reprobed with anti-actin antibody to normalize for differences in protein loading.

2. 10. ChIP and PCR analysis

ChIP was performed by using the Chromatin Immunoprecipitation Assay kit (Upstate Biotechnology, Lake Placid, NY) according to manufacturer's instructions with minor modifications. Briefly, ≈ 2 × 106 cells were fixed with 1% formaldehyde and lysed in SDS lysis buffer. DNA in the cross-linked chromatin preparations was sheared to 200–1,000 bp by sonication. Samples were precleared with salmon sperm DNA/protein A agarose (50%) slurry. After addition of antibodies and fresh protein A agarose, the samples were incubated at 4°C overnight. Normal mouse or rabbit IgG was used as a control. Precipitated chromatin complexes were eluted by 500 μl of elution buffer (1% SDS, 0.1 M NaHCO3) for 30 min. Finally, the protein-DNA cross-links were reversed by overnight incubation with 100 μM NaCl at 65°C, and immunoprecipitated DNA was analyzed by PCR using primers as follows: PUMA (region -152 to -46) forward primer, 5-GCGAGACTGTGGCCTTGTGT-3; PUMA (region -152 to -46) reverse primer, 5-CAAGTCAGGACTTGCAGGG-3. Antibodies for ChIP included rabbit polyclonal antibodies against p53 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), and monoclonal antibodies for acetylated histones H3 (Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA, USA).

2. 11. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was carried out using Graphpad InStat 3 software (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Results were considered statistically significant at P<0.05.

3. Results

3. 1. Baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin affect survival of LNCaP cells differently

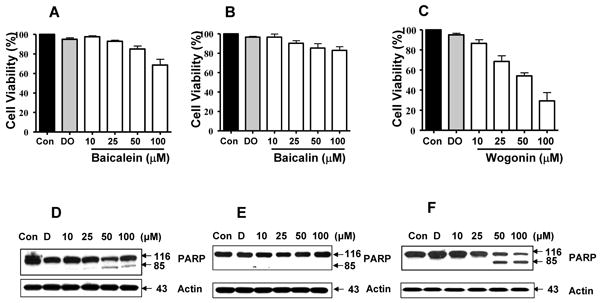

Flavonoids are diphenylpropanes that are commonly found in plants. More than 4,000 flavonoids have been found and are frequently components of the human diet. However, several biological activities of flavonoids are still undefined. It is well known that baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin are the major flavonoids produced by S. baicalensis (Fig. 1). In this study, we examined the effects of baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin on cell viability and drug-induced PARP-1 cleavage, the hallmark feature of apoptosis, in human prostate LNCaP cells by trypan blue exclusion dye assay and western blotting, respectively (Fig. 2). When LNCaP cell were treated with various concentrations of each indicated compound (10, 25, 50 and 100 μM) for 24 h, significant concentration-dependent reduction of the viability of LNCaP cells was observed (upper panels in Fig. 2) and increase in the cleavage of 116 kDa PARP-1 into 85 kDa fragments was detected in the presence of wogonin and to a lesser extent, baicalein, but not obvious in baicalin-treated cells. DMSO (lower panels in Fig. 2), even at the highest dose of 0.5%, showed no effect on the cellular viability of LNCaP cells (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Effects of baicalein, baicalin, and wogonin on the cell viability of human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells.

Cells (1×105) were plated, allowed to attach overnight, and then treated with DMSO (control) or 10-100 μM of baicalein, baicalin, or wogonin for 24 h at 37°C. (A, B, C) Cell viability was determined by trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent the mean ± S.E from three separate experiments. (D, E, F) Cells were harvested and samples were prepared for analysis of the cleavage of PARP-1 using Western blot analysis. Actin was shown as an internal standard.

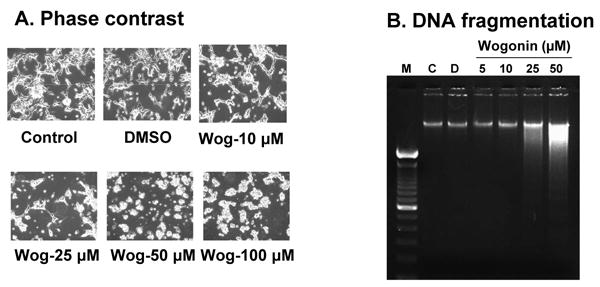

3. 2. Wogonin causes apoptotic death of LNCaP cells

To confirm whether wogonin induces apoptosis in LNCaP cells, in the first step, we examined wogonin-induced cytotoxicity. To investigate morphological changes, cells were treated with 0-100 μM wogonin for 24 h and then observed under a light microscope and photographed. Observations made under the microscope showed that, after wogonin treatment, the cell number decreased (data not shown) and, more interestingly, the shape of cells had changed in comparison to control cells. As shown in Fig. 3A, in the cultures treated with wogonin there were fewer cells, and apoptotic cell death, which is associated with typical morphological features like cell shrinkage and cytoplasmic membrane blebbing. In Fig. 3B, we also examined the effect of increasing concentrations of wogonin on the induction of DNA ladder formation (DNA banding characteristic of late apoptosis). We noted differences in DNA banding formation between control lanes and those treated with increasing concentrations of wogonin for 24 h.

Fig. 3. Wogonin induces apoptosis in LNCaP cells.

Cells were treated with various concentrations (10-100 μM) of wogonin or 0.1% DMSO for 24 h. (A), Cell morphology was examined under a light microscope. Magnification, × 200. Wog: wogonin. (B), DNA isolated from cells that were untreated (C, lane 2), or treated with DMSO (D, lane 3) or wogonin (lane 4-7) was fractionated by electrophoresis. Oligonucleosomal length DNA fragments were visualized by staining gels with ethidium bromide. Lane 1, DNA ladder. Similar results were obtained in two separate experiments.

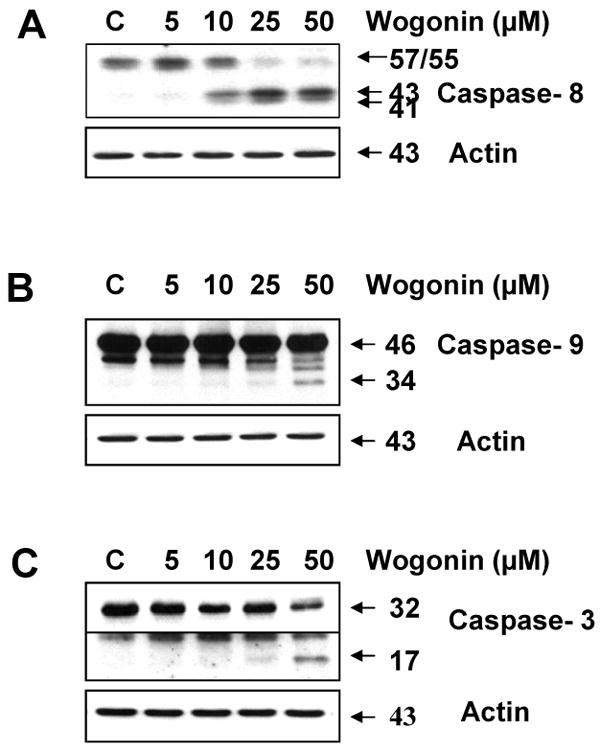

3. 3. Caspase activation mediates wogonin-induced apoptosis

Activation of both extrinsic and intrinsic caspase pathways has been well established to be the major mechanism of apoptotic cell death in most cellular systems [46]. Based on our findings showing that wogonin causes strong apoptotic death of LNCaP cells, we first assessed whether wogonin activates caspase pathways. Treatment of cells with wogonin indeed resulted in strong dose dependent caspase-8, caspase-9, and caspase-3 activation and cleavage (Figs. 4A, B, C). Western blot analysis shows that procaspase-8 (57/55 kDa) was cleaved to the intermediate (43/41 kDa) forms by treatment with wogonin. Wogonin induced proteolytic processing of procaspase-9 (46 kDa) into its active form (34 kDa). Figure 4C also demonstrates that procaspase-3 (32 kDa), the precursor form of caspase-3, was cleaved to active form (17 kDa) by treatment with wogonin. Figure 4C shows a line through the middle of the blots. This is due to combining images having two different exposure times which came from the same blot, because the image of 17 kDa was relatively weak.

Fig. 4. Wogonin activates caspases in LNCaP cells.

In vitro treatment of LNCaP cells with wogonin caused the cleavage of caspase-8 (A), caspase-9 (B), and caspase-3 (C). Cells were treated with various concentrations of wogonin (5-50 μM) for 24 h, and then cells were harvested. Lysates containing equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Actin was used to confirm the equal amount of proteins loaded in each lane.

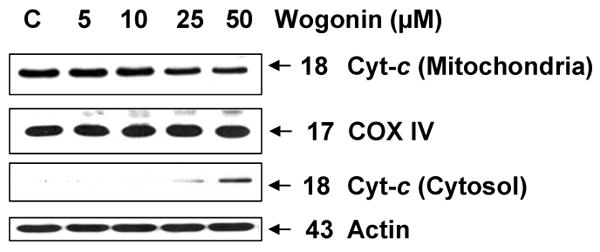

3. 4. Wogonin causes release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to cytosol

The activation of caspase-9 during treatment with wogonin indicates an involvement of the intrinsic pathway in wogonin-induced apoptosis. One of the hallmarks of the intrinsic pathway of apoptosis is the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c into the cytosol [47, 48]. Mitochondrial dysfunction promoted by Bax translocation usually leads to the leakage of cytochrome c from mitochondria [49]. Cytochrome c released into the cytosol forms a multimeric complex with apoptotic protease-activating factor 1 and pro-caspase leading to the activation of caspase-9 and downstream caspases [50]. In our current study, to provide evidence of cytochrome c release to the cytosol following wogonin treatment, we compared amounts of cytochrome c in the mitochondria and in the mitochondria-free cytosolic extracts prepared from LNCaP cells treated with or without wogonin for 24 h. We used actin for a cytosolic marker and COX IV for a mitochondrial marker as fractional markers and loading controls. Figure 5 clearly demonstrates that wogonin induced cytochrome c release in a dose-dependent manner. Altogether, the data shown in Figs. 4B, 4C and 5 clearly indicate that wogonin activates the intrinsic caspase cascade via cytochrome c release into the cytosol from the mitochondria, leading to caspase-9 followed by caspase-3 activation that results in PARP-1 cleavage and apoptotic cell death.

Fig. 5. Wogonin treatment causes release of cytochrome c from mitochondria to the cytosol in LNCaP cells.

Cytochrome c release from mitochondria to cytosol was examined in LNCaP cells which were incubated overnight with wogognin (5, 10, 25, and 50 μM) or without (C; control). Lysates containing equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-cytochrome c antibody. We used actin as a cytosolic marker and COX IV as a mitochondrial marker. The top and third panels represent mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions, respectively.

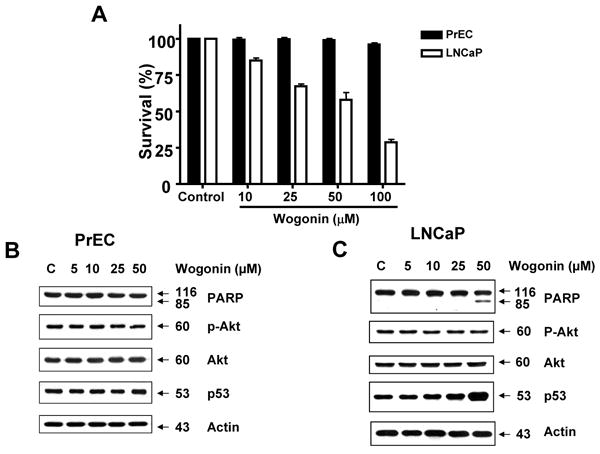

3. 5. Wogonin enhances apoptosis in LNCaP, but not in PrEC cells

We also compared the cytotoxicity of wogonin to both human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells and normal human prostate epithelial PrEC cells. To determine the accurate range of cytotoxic concentrations of wogonin in both cell lines, we used the trypan blue exclusion dye assay to measure cell viability. Cells were exposed to 0–100 μM of wogonin for 24 h. Wogonin induced cell death in a dose dependent manner after 24 h of incubation in LNCaP but not PrEC cells (Fig. 6A). For LNCaP cells but not for PrEC cells, incubation with wogonin for 24 h resulted in dramatic cell mortality with an estimated 50% of cell death (IC50) at a value of 60 μM (Fig 6A). Likewise, for LNCaP cells but not for PrEC cells, wogonin induced apoptosis as indicated by PARP-1 cleavage (Figs. 6B and 6C). It is well known that decreased Akt activity accompanies flavonoid-induced apoptosis [51]. Previous studies demonstrated that Akt activation is regulated through the PI3K-Akt pathway [52]. To examine whether wogonin inhibits Akt activity by dephosphorylating Akt, we treated LNCaP and PrEC cells with various concentrations of wogonin and measured the level of phophorylated Akt. We observed that wogonin did not induce dephosphorylation of Akt in both LNCaP and PrEC cells (Figs. 6B and 6C). Interestingly, we observed that an increase in p53 level occurred during treatment with wogonin in LNCaP, but not PrEC cells (Figs. 6B and 6C). These data suggest that an increase in p53 level may be involved in wogonin-induced apoptotic death in LNCaP cells.

Fig. 6. Wogonin induces cytotoxicity in human prostate cancer LNCaP cells, but not in prostate epithelial cells (PrEC).

LNCaP and PrEC cells were treated with various concentrations (10-100 μM) of wogonin for 24 h. (A) The cytotoxic effect of wogonin on LNCaP and PrEC cells was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SEM) from three separate experiments. (B, C) Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from cell lysates of PrEC or LNCaP cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-Akt, anti-Akt, anti-PARP-1, or anti-p53 antibody. Actin was shown as an internal standard.

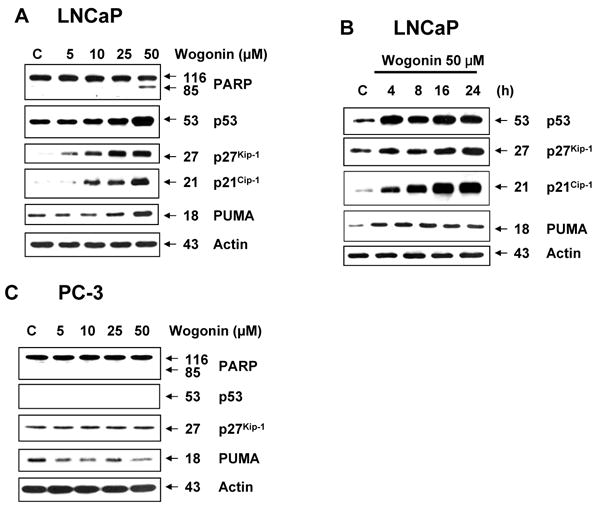

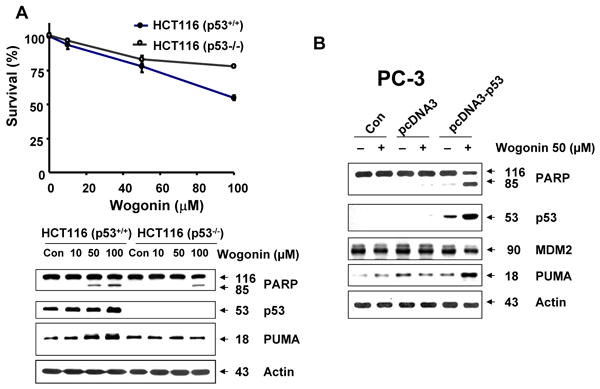

3. 6. Role of p53 in wogonin-induced apoptotic death

We hypothesized that p53 plays an important role in wogonin-induced apoptosis. To test the hypothesis, we examined p53-associated protein levels during treatment with wogonin. Since the p53 protein is a major regulator of cell cycle and apoptosis following genotoxic damage [26, 53, 54], we screened cell cycle or apoptosis-related proteins. Figures 7A and 7B show that consistent with accumulation of p53, p21Cip-1, p27Kip-1 and PUMA proteins accumulated in wogonin-treated LNCaP cells. Wogonin increased the intracellular levels of these proteins in dose- and time-dependent manners. Unlike p53-wild LNCaP cells, p53-null PC-3 cells showed no increase in p27Kip-1 and PUMA proteins during treatment with wogonin (Fig. 7C). Moreover, wogonin treatment did not induce PARP-1 cleavage in PC-3 cells. To confirm the involvement of p53 in wogonin-induced apoptosis, two sets of experiments were performed. In the first set, two HCT116 human colon adenocarcinoma cell lines, one containing a wild-type p53 (p53+/+) and the other p53-deleted derivative (p53-/-), were treated with wogonin. Immunoblotting of cell lysates revealed a sustained increased level of p53 protein after 8 h exposure to wogonin in HCT116 p53+/+ cells, which was maintained at least 24 h after treatment (data not shown). As shown in Fig. 8A, the IC50 (dose to kill 50% of cells) value of wogonin in HCT116 p53+/+ cells (115 μM) was substantially lower compared with that of HCT116 p53−/− cells (210 μM), reflecting the fact that HCT116 p53−/− cells are resistant to wogonin and that p53 plays a role in wogonin-induced cytotoxicity. Figure 8A also shows that a lower amount of PARP-1 cleavage and PUMA accumulation occurred in HCT116 p53-/- cells in comparison to HCT116 p53+/+ cells during treatment with wogonin. In the second set of experiments, p53-null PC-3 cells were transfected with plasmid containing p53 cDNA (pcDNA3-p53) to determine the involvement of p53 in wogonin-induced apoptosis. Wogonin treatment induced PARP cleavage and significantly increased the amounts of PUMA in pcDNA3-p53 plasmid transfected PC-3 cells, but had little or no effect in parental PC-3 and control vector pcDNA3 transfected PC-3 cells (Fig. 8B). These results consistently suggest that overexpression of p53 results in apoptosis by increasing PUMA, a pro-apoptotic protein. Nevertheless, it is interesting that cellular p53 levels were higher in wogonin treated cells following p53 transfection. This is not likely due to transcription of p53 mRNA (especially since p53 transcription from the plasmid promoter should not be affected). Interestingly, Figure 8B shows that Mdm2 levels were decreased by 30% in wogonin treated cells following p53 transfection. Thus, it is possible that wogonin affects p53 levels by altering Mdm2 levels. This possibility needs to be further investigated.

Fig. 7. Wogonin increases the intracellular level of p53 and its downstream cell cycle-related proteins as well as apoptosis-related protein in human prostate carcinoma LNCaP cells, but not in p53-null PC-3 cells.

LNCaP PC-3 cells were treated with various concentrations (0-50 μM) of wogonin for 24 h or LNCaP cells were treated with 50 μM wogonin for various times (4-24 h), and Western blot analysis was done for PARP-1, p53, p27Kip-1, p21Cip-1, or PUMA. Lysates containing equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted. Actin was used to confirm the equal amount of proteins loaded in each lane.

Fig. 8. Involvement of p53 and PUMA in wogonin-induced apoptosis.

(A), HCT116 p53+/- and HCT116 p53-/- cells were treated with various concentrations (10-100 μM) of wogonin for 24 h. Cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay (Upper panel). Error bars represent the mean ± SE from three separate experiments. Comparisons of IC50 were made by dose response curve fitting. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from cell lysates cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PARP-1, anti-p53, or anti-PUMA antibody (Lower panel). Actin was shown as an internal standard. (B) PC-3 cells were transiently transfected with pcDNA3 vector containing empty (pcDNA3) or wild-type p53 cDNA (PcDNA-p53). After 48 h incubation, cells were treated with or without wogonin (50 μM) for 24 h. Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from cell lysates cells were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-PARP-1, anti-p53, anti-Mdm2, or anti-PUMA antibody. Actin was shown as an internal standard.

3. 7. Wogonin-promoted PUMA gene transcription is mediated through an increase in p53 binding to PUMA promoter

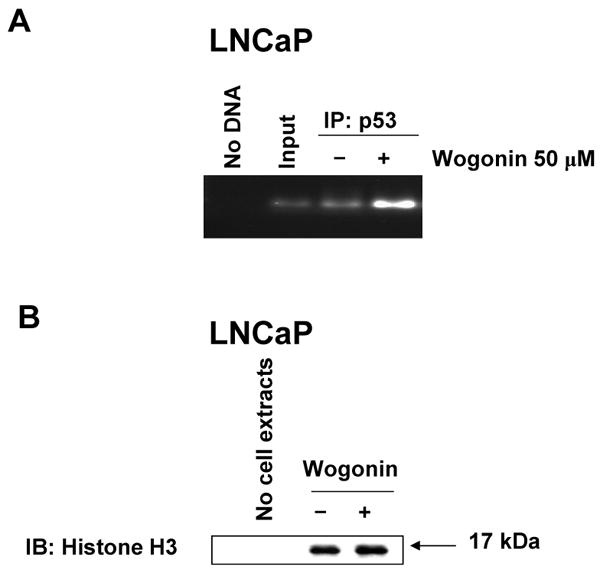

We further examined whether upregulation of PUMA gene expression by treatment with wogonin is due to activation of transcriptional activity. Data from western blotting in Figs. 7A and 8 show that the level of PUMA protein was significantly increased during treatment with wogonin. These results suggest that the increase of PUMA protein levels during treatment with wogonin was related to expression of PUMA gene transcription. It is well known that PUMA promoter region contains binding sites of putative transcription factors such as p53. We hypothesized that wogonin affects binding affinity of this transcription factor in the PUMA promoter region and subsequently activates transcription of the PUMA gene. To investigate whether wogonin specifically alters p53 binding activity to the PUMA promoter region, p53 binding activity to sonicated chromatin was determined by ChiP assay. Data from ChiP assay clearly demonstrate that wogonin treatment markedly increased recruitment of p53 to the proximal site of PUMA promoter in LNCaP cells (Fig. 9A). However, when total p53 binding activity to sonicated chromatin was determined by immunoprecipitation with anti-p53 antibody followed by immunoblotting with anti-histone H3, total p53 binding activity wasn't significantly changed in the presence of wogonin (Fig. 9B). Taken together, our data suggest that specific promotion of p53 binding activity to PUMA promoter occurs by treatment with wogonin.

Fig. 9. Transcription factor binding activity in PUMA promoter during treatment with wogonin in LNCaP cells.

Cells were treated with 50 μM wogonin for 24 h. (A) Cells were sonicated and chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 antibody. PUMA promoter contains p53 binding sites (-1409 ∼ -76, 8 putative binding sites). The binding of p53 on PUMA promoter was analyzed by PCR. (B), chromatin fragments were immunoprecipitated with anti-p53 antibody. Interaction between p53 and histone H3 was performed with anti-histone H3 antibody.

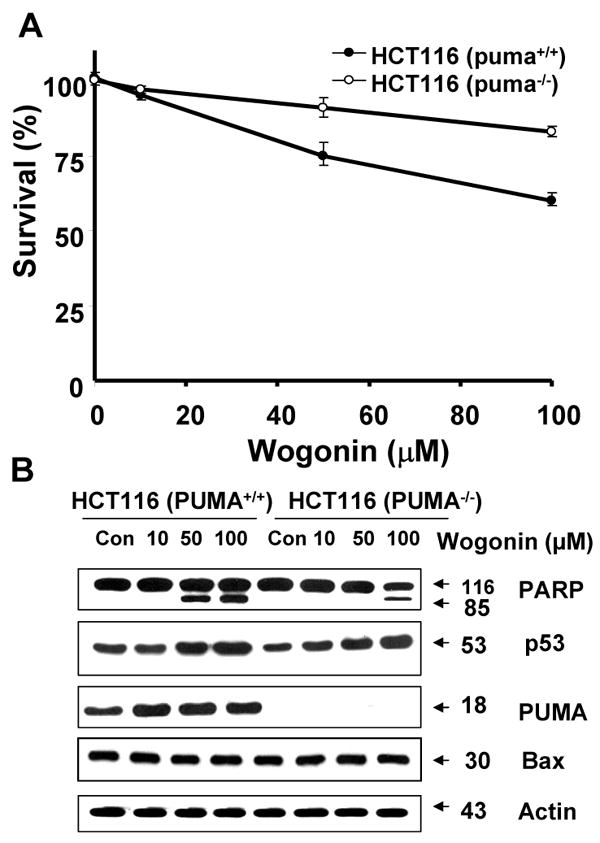

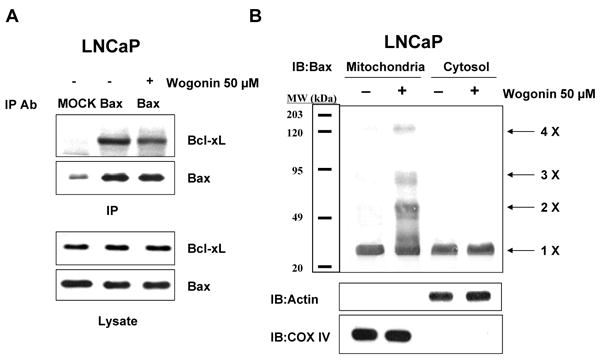

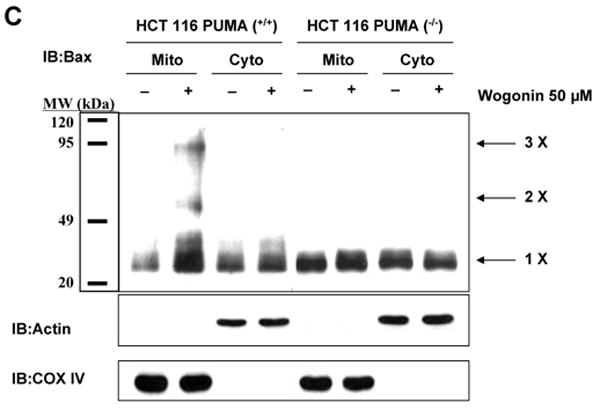

3. 8. Role of Bax in PUMA-associated wogonin-induced apoptosis

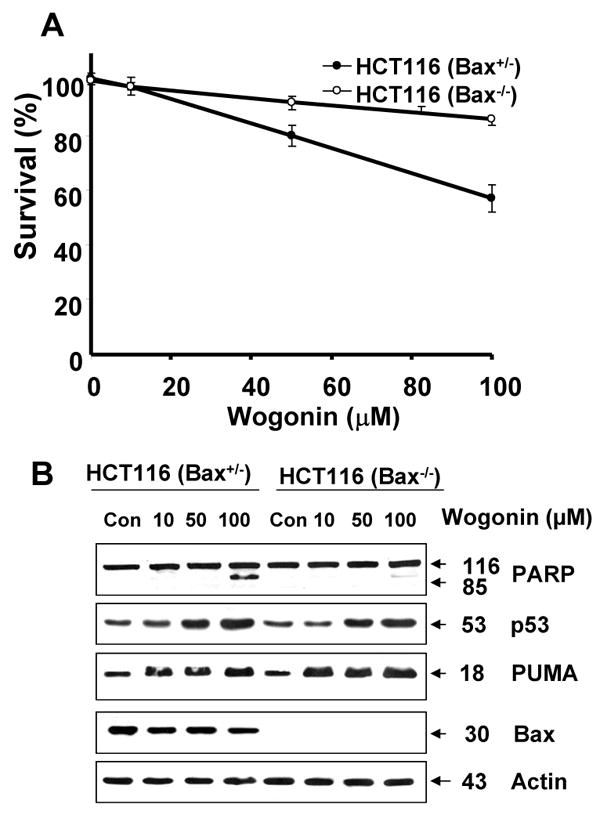

To evaluate further the apoptosis associated with PUMA expression, we employed cells expressing PUMA (HCT116 PUMA+/+) and not expressing PUMA (HCT116 PUMA−/−) and treated them with wogonin. Figure 10A shows that the IC50 value of wogonin in HCT116 PUMA+/+ cells (125 μM) was substantially lower compared to that of HCT116 PUMA−/− cells (280 μM), reflecting the fact that HCT116 PUMA−/− cells are resistant to wogonin and that PUMA plays a role in wogonin-induced cytotoxicity. We also observed that 50-100 μM wogonin was required for induction of PARP-1 cleavage in HCT116 PUMA+/+ cells, whereas minimal cleavage of PARP-1 occurred in 100 μM wogonin treated HCT116 PUMA−/− cells (Fig. 10B). Although the intracellular level of p53 was increased in both cell lines during treatment with wogonin, PARP-1 cleavage was effectively increased in the presence of PUMA (Fig. 10B). These results suggest that p53 up-regulated PUMA plays an important role in apoptosis. Interestingly, there was no change in the level of Bax by treatment with wogonin. As a next step, we examined how PUMA is involved in apoptotic death. Since PUMA is a BH3 domain-containing protein found predominantly in mitochondria, we hypothesized that PUMA-induced apoptosis is mediated through Bax activation. To test the hypothesis, we first examined the role of Bax in wogonin-induced apoptosis. Previous experiments have shown that BH3 domain-containing proteins such as Bik and Bid induced apoptosis in a Bax-dependent manner. Association of BH3 domain containing PUMA with Bcl-xL may result in dissociation of Bax from Bcl-xL [55-57]. Indeed, Figure 11A shows that Bax dissociated from Bcl-xL during treatment with wogonin. After treatment with wogonin, Bax multimerized in the mitochondria (Fig. 11B). The extent of Bax oligomerization was compatible with that demonstrated to cause pore formation in isolated mitochondria and artificial liposomes [58]. Wogonin-induced Bax oligomerization was observed in HCT116 PUMA+/+, but not in HCT116 PUMA−/− (Fig. 11C). These results again suggest that PUMA-associated apoptosis is mediated through Bax. To further examine whether apoptosis induced by wogonin depends on the presence of Bax, we employed HCT116 Bax+/- as well as HCT116 Bax−/− cells. As shown in Fig. 12, compared to HCT116 Bax+/- cells, wogonin-induced apoptosis was significantly decreased in HCT116 Bax−/− cells, even though wogonin significantly enhanced the intracellular levels of p53 and PUMA in both cell lines. The IC50 value of wogonin in HCT116 Bax+/- cells (115 μM) was substantially lower compared to that of HCT116 Bax−/− cells (280 μM),

Fig. 10. Role of PUMA in wogonin-induced apoptosis.

HCT116 PUMA+/+ and HCT116 PUMA-/- cells were treated various concentrations (10-100 μM) of wogonin for 24 h. (A), Cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent the mean ± SE from three separate experiments. Comparisons of IC50 were made by dose response curve fitting. (B) Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PARP-1, anti-p53, anti-PUMA, or anti-Bax antibody. Actin was shown as an internal standard.

Fig. 11. Oligomerization of Bax during wogonin treatment.

LNCaP, HCT116 PUMA+/+, or HCT116 PUMA-/- cells were treated with 50 μM wogonin for 24 h. (A), Cell lysates for LNCaP cells were immunoprecipitated with anti-Bax antibody or mock antibody (IgG) and immunoblotted with anti-Bcl-xL antibody (upper panels). The presence of Bax in the lysates was verified by immunoblotting (lower panel). (B, C), Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions were isolated and cross-linked and then subjected to immunoblotting with an antibody to Bax. Bax monomers (1×) and multimers (2× – 4×) are indicated. We used actin for a cytosolic marker and COX IV for a mitochondrial marker as fractional markers and loading controls.

Fig. 12. Role of Bax in wogonin-induced apoptosis.

HCT116 Bax+/- and HCT116 Bax-/- cells were treated with various concentrations (10-100 μM) of wogonin for 24 h. (A), Cell viability was determined using the trypan blue dye exclusion assay. Error bars represent the mean ± SE from three separate experiments. Comparisons of IC50 were made by dose response curve fitting. (B) Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) from cell lysates were separated by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotted with anti-phospho-PARP-1, anti-p53, anti-PUMA, or anti-Bax antibody. Actin was shown as an internal standard.

4. Discussion

In this study, we focused on one potential chemoprevention agent, wogonin, which is one of the active ingredients of “golden root”, of Scutellaria baicalensis GEORGI (Huang-Qin). We observed the apoptosis induction activity of wogonin in human prostate carcinoma LNCaP and human colon carcinoma HCT116 cells, and the results also showed that wogonin-induced apoptosis was mediated by up-regulation of p53 and PUMA, and oligomerization of Bax. This finding reveals an interesting correlation between gene regulation and wogonin-induced apoptosis, and provides a molecular basis for the development of naturally occuring monoflavonoids as novel anticancer agents for better management of human cancers. Also, an important observation of our investigation is that wogonin did not cause apoptosis or result in decreased viability, even at the highest tested concentration (100 μM) in normal human prostate epithelial PrEC cells (Fig. 6A). This is important because an ideal chemoprevention agent should be able to eliminate cancer cells without any toxicity to normal cells.

During this study, we investigated the action of p53, which has been known to have a major cellular role, functioning as a cell cycle regulator by arresting the cell cycle and as an inducer of apoptosis in response to a variety of cellular stresses, sometimes inducing apoptosis by inducing transcription in genes that encode pro-apoptotic factors, such as PUMA [59-62; Figs. 7 and 8]. Since the induction of apoptosis is a major mechanism of most chemotherapeutic agents, many attempts have been made to develop small molecules to induce p53 within tumor cells and thus induce p53-dependent apoptosis [63, 64]. Several mechanisms of apoptosis induction by p53 have been identified involving transcriptional and/or non-transcriptional regulation of its downstream effectors [65]. For example, p53 is known to induce apoptosis by transcriptional up-regulation of proapoptotic genes such as Noxa, PUMA, Bax, Apaf-1, and by transcriptional repression of Bcl-2 and inhibitors of apoptosis [65]. However, in our study, we observed that wogonin treatment does not alter the levels of Bcl-2 and Bax (data not shown; Fig. 10B). In the case of non-transcriptional mechanisms, it has been reported that p53 translocates to mitochondria preceding cytochrome c release and pro-caspase-3 activation [66]. It has also been reported that p53 induces apoptosis via physical interaction with the antiapoptotic proteins Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL through its DNA-binding domain, thus leading to sequestration of these proteins from their interaction with proapoptotic partners, Bax/Bak proteins, and, as a result, allowing Bax/Bak to form oligomers and permeabilize the outer mitochondrial membrane, thereby causing the release of mitochondrial cytochrome c to the cytosolic compartment of the cell [67]. Further, it has been recently shown that Eugenol, a principal component of Szygium aromaticum (L.) Merr. Et Perry flower bud (cloves), induces apoptosis in mast cells by increasing p53 in the mitochondria where it interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, thus abrogating their survival function [68]. Consistent in part with these studies, we also observed an increase in p53 in wogonin-treated cells, which might be responsible for inducing apoptotic death of LNCaP cells by similar mechanisms. However, our data clearly demonstrated that p53-associated apoptosis is mainly mediated through PUMA (Figs. 10 and 11C). Thus, additional studies are required in the future to further elucidate the exact mechanism and role of p53 in wogonin-induced apoptotic cell death.

Recent studies and our studies have shown that two p53-binding sites are present on the PUMA promoter [37, 69-71, Fig. 9A]. Nuclear p53 proteins interact with both binding sites and regulate PUMA gene expression [71]. It is well known that p53 levels are maintained at low and inactivate state under normal conditions. Activation of p53 can occur in response to a variety of cellular stresses, including hypoxia, nucleotide deprivation and DNA damage, which rapidly increase p53 levels and promote its DNA binding activity [72]. An increase in p53 level is achieved through post-translational modification of p53 protein rather than transcriptional regulation [73]. In this study, we observed that an increase in p53 level with an increase in its ability to bind to the PUMA promoter occurred during treatment with wogonin (Figs. 6, 7, and 9). Thus, a fundamental question which remains unanswered is how wogonin treatment increases the intracellular level of p53. At the present time, we can only speculate about the mechanism of up-regulation of p53 during wogonin treatment. Figure 8B shows that cellular Mdm2 level is lower in wogonin treated cells following p53 infection. It is possible that wogonin affected the p53 level by altering the Mdm2 level in the pcDNA3-p53 plasmid transfected cells. The other possibility is that wogonin induces a series of post-translational modification events (phosphorylation, dephosphorylation, methylation, sumoylation and acetylation) in the p53 protein. Previous studies have demonstrated that p53 can be phosphorylated in vitro on both the N-terminal and C-terminal regulatory domains by various kinases, including cyclin dependent kinases (Cdks), casein kinase I (CKI), casein kinase II (CKII), protein kinase C (PKC), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), C-Jun N-terminal kinase (JNK), Raf kinase, DNA-dependent protein kinase (DNA-PK), ataxia-telangiectasia-mutated (ATM) kinase, and ATM- and Rad3-related (ATR) kinase [74-82]. Dephosphorylation methylation, sumoylation and acetylation of p53 which also occurs in response to DNA damage may regulate p53 activity [83-85]. It is well known that post-translational modifications of p53 free p53 from p53-Mdm2 (mouse double minute 2) complex and result in dramatically increasing the half-life of p53. Thus, it is possible that wogonin induces post-translational modifications of p53 and increases the intracellular level of p53. We believe that many critical questions still remain to be answered to understand the mechanisms of the up-regulation of p53 during treatment with wogonin. However, this model will provide a framework for future studies.

In Fig. 6, we observed that normal cells, compared with tumor cells, are resistant to wogonin-induced apoptosis. Previous studies have shown that reduced amounts of antioxidant enzymes, especially MnSOD, are found in a variety of cancer cells [86]. Also lowered amounts of CuZnSOD have been found in many, but not all, tumors. MnSOD and CuZnSOD are essential primary enzymes that convert O2·- to H2O2 and O2 within the mitochondria and cytoplasm, respectively. These observations suggest a rationale as to why tumor cells are more sensitive than normal cells to wogonin-induced reactive oxygen species [87]. However, contradictory observations were also reported [88, 89]. Thus, this hypothesis needs to be tested.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the following grants: NCI grant funds (CA95191, CA96989 and CA121395), DOD prostate program funds (PC020530 and PC040833), Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation fund (BCTR60306).

Abbreviations used here are

- ChIP

chromatin immunoprecipitation

- CDK

cyclin-dependent kinase

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- PARP-1

poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- PrEC

normal human prostate epithelial cells

- PUMA

p53 up-regulated modulator of apoptosis

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Greenlee RT, Murray T, Bolden S, Wingo PA. Cancer statistics. CA - Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:7–33. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.50.1.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carter HB, Coffey DS. The prostate: an increasing medical problem. Prostate. 1990;16:39–48. doi: 10.1002/pros.2990160105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Garnick MB. Hormonal therapy in the management of prostate cancer: from Higgins to the present. Urology. 1997;49:5–15. doi: 10.1016/s0090-4295(97)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albertsen PC, Fryback DG, Storere BE. Long-term survival among men with conservatively treated localized prostate cancer. J Am Med Assoc. 1995;274:626–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tsao AS, Kim ES, Hong WK. Chemoprevention of cancer. CA Cancer J Clin. 2004;54:150–80. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.54.3.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sporn MB, Suh N. Chemoprevention: an essential approach to controlling cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:537–43. doi: 10.1038/nrc844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zaridze DG, Boyle P, Smans M. International trends in prostatic cancer. Int J Cancer. 1984;33:223–30. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910330210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parkin DM, Muir CS, Whelan S, Gao YT, Ferlay J, Powell J, editors. IARC Sci Publ No 120. Lyon, France: IARC; 1992. Cancer incidence in five continents, Vol. VI. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Denis L, Morton MS, Griffiths K. Diet and its preventive role in prostatic disease. Eur Urol. 1999;35:377–87. doi: 10.1159/000019912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuo SM. Dietary flavonoids and cancer prevention: evidence and potential mechanism. Crit Rev Oncog. 1997;8:47–69. doi: 10.1615/critrevoncog.v8.i1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller AB. Diet and cancer: a review. Rev Oncol. 1990;3:87–95. doi: 10.3109/02841869009089996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jankun J, Selman HJ, Swiercz R, Skrzypczak-Jankun E. Why drinking green tea could prevent cancer. Nature. 1997;387:561. doi: 10.1038/42381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Messina M, Barnes S. The role of soy products in reducing the risk of cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst (Bethesda) 1991;83:541–6. doi: 10.1093/jnci/83.8.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kubo M, Asano T, Shiomoto H, Matsuda H. Studies on rehmanniae radix. I. Effect of 50% ethanolic extract from steamed and dried rehmanniae radix on hemorheology in arthritic and thrombosic rats. Biol Pharm Bull. 1994;17:1282–6. doi: 10.1248/bpb.17.1282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chi YS, Cheon BS, Kim HP. Effect of wogonin, a plant flavone from Scutellaria radix, on the suppression of cyclooxygenase-2 and the induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase in lipopolysaccharide-treated RAW 264.7 cells. Biochem Pharmacol. 2001;61:1195–203. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00597-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.You KM, Jong HG, Kim HP. Inhibition of cyclooxygenase/lipoxygenase from human platelets by polyhydroxylated/methoxylated flavonoids isolated from medicinal plants. Arch Pharm Res. 1999;22:18–24. doi: 10.1007/BF02976430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li DR, Hou HX, Zhang W, Li L. Effects of wogonin on inducing apoptosis of human ovarian cancer A2780 cells and telomerase activity. Ai Zheng. 2003;22:801–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lee WR, Shen SC, Lin HY, Hou WC, Yang LL, Chen YC. Wogonin and fisetin induce apoptosis in human promyeloleukemic cells, accompanied by a decrease of reactive oxygen species, and activation of caspase 3 and Ca(2+)-dependent endonuclease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:225–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chen YC, Shen SC, Lee WR, Lin HY, Ko CH, Shih CM, Yang LL. Wogonin and fisetin induction of apoptosis through activation of caspase 3 cascade and alternative expression of p21Cip1 protein in hepatocellular carcinoma cells SK-HEP-1. Arch Toxicol. 2002;76:351–9. doi: 10.1007/s00204-002-0346-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Ko LJ, Jayaraman L, Prives C. p53 levels, functional domains, and DNA damage determine the extent of the apoptotic response of tumor cells. Genes Dev. 1996;10:2438–51. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.19.2438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yu Z, Chen J, Ford BN, Brackley ME, Glickman BW. Human DNA repair systems: an overview. Environ Mol Mutagen. 1999;33:3–20. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-2280(1999)33:1<3::aid-em2>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barry MA, Behnke CA, Eastman A. Activation of programmed cell death (apoptosis) by cisplatin, other anticancer drugs, toxins and hyperthermia. Biochem Pharmacol. 1990;40:2353–62. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(90)90733-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoffman B, Liebermann DA. Molecular controls of apoptosis: differentiation/growth arrest primary response genes, proto-oncogenes, and tumor suppressor genes as positive & negative modulators. Oncogene. 1994;9:1807–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levine AJ. p53, the cellular gatekeeper for growth and division. Cell. 1997;88:323–31. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chao C, Saito S, Kang J, Anderson CW, Appella E, Xu Y. p53 transcriptional activity is essential for p53-dependent apoptosis following DNA damage. EMBO J. 2000;19:4967–75. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.18.4967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–10. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nigro JM, Baker SJ, Preisinger A, Jessup CM, Hosteller JR, Cleary K, Signer SH, Davidson N, Baylin S, Devilee P, Glover T, Collins FS, Weslon A, Modali R, Harris CC, Vogelstein B. Mutations in the p53 gene occur in diverse human tumor types. Nature. 1989;342:705–8. doi: 10.1038/342705a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ryan KM, Phillips AC, Vousden KH. Regulation and function of the p53 tumor suppressor protein. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2001;13:332–7. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(00)00216-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gartenhaus RB, Wang P, Hoffmann P. Induction of the WAF1/CIP1 protein and apoptosis in human T-cell leukemia virus type I-transformed lymphocytes after treatment with adriamycin by using a p53-independent pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:265–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.1.265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu ZG, Baskaran R, Lea-Chou ET, Wood LD, Chen Y, Karin M, Wang JY. Three distinct signalling responses by murine fibroblasts to genotoxic stress. Nature. 1996;384:273–6. doi: 10.1038/384273a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lane D, Hupp TR. Drug discovery and p53. Drug Discov Today. 2003;8:347–55. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6446(03)02669-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Niculescu AB, 3rd, Chen X, Smeets M, Hengst L, Prives C, Reed SI. Effects of p21(Cip1/Waf1) at both the G1/S and the G2/M cell cycle transitions: pRb is a critical determinant in blocking DNA replication and in preventing endoreduplication. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:629–43. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.1.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sohn TA, Bansal R, Su GH, Murphy KM, Kern SE. High-throughput measurement of the Tp53 response to anticancer drugs and random compounds using a stably integrated Tp53-responsive luciferase reporter. Carcinogenesis. 2002;23:949–57. doi: 10.1093/carcin/23.6.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ormerod MG, O'Neill C, Robertson D, Kelland LR, Harrap KR. cis Diamminedichloroplatinum (II)-induced cell death through apoptosis in sensitive and resistant human ovarian carcinoma cell lines. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 1996;37:463–71. doi: 10.1007/s002800050413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lowe SW, Lin AW. Apoptosis in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:485–95. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.3.485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Johnstone RW, Ruefli AA, Lowe SW. Apoptosis: a link between cancer genetics and chemotherapy. Cell. 2002;108:153–64. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00625-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yu J, Zhang L, Hwang PM, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. PUMA induces the rapid apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells. Mol Cell. 2001;7:673–82. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00213-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Puthalakath H, Strasser A. Keeping killers on a tight leash: transcriptional and post-translational control of the pro-apoptotic activity of BH3-only proteins. Cell Death Differ. 2002;9:505–12. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4400998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ming L, Wang P, Bank A, Yu J, Zhang L. PUMA Dissociates Bax and Bcl-X(L) to induce apoptosis in colon cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16034–42. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M513587200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaguchi H, Chen JD, Bhalla K, Wang HG. Regulation of BAX activation and apoptotic response to microtubule-damaging agents by p53 transcription-dependent and -independent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:39431–7. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M401530200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schuler M, Green DR. Mechanisms of p53-dependent apoptosis. Biochem Soc Trans. 2001;29:684–7. doi: 10.1042/0300-5127:0290684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.DeHaan RD, Yazlovitshaya EM, Persons DL. Regulation of p53 target gene expression by cisplatin-induced extracellular signal-regulated kinase. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2001;48:383–8. doi: 10.1007/s002800100318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Futami T, Miyagishi M, Taira K. Identification of a network involved in thapsigargin-induced apoptosis using a library of siRNA-expression vectors. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:826–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M409948200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Burow ME, Weldon CB, Tang Y, Navar GL, Krajewski S, Reed JC, Hammond TG, Clejan S, Beckman BS. Differences in susceptibility to tumor necrosis factor alpha-induced apoptosis among MCF-7 breast cancer cell variants. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4940–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laemmli UK. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970;227:680–5. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fadeel B, Orrenius S. Apoptosis: a basic biological phenomenon with wide-ranging implications in human disease. J Intern Med. 2005;258:479–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2005.01570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Riedl SJ, Shi Y. Molecular mechanisms of caspase regulation during apoptosis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2004;5:897–907. doi: 10.1038/nrm1496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang X, Wang X. Cytochrome c-mediated apoptosis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:87–106. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Costantini P, Jacotot E, Decaudin D, Kroemer G. Mitochondrion as a novel target of anticancer chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2000;92:1042–53. doi: 10.1093/jnci/92.13.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Slee EA, Harte MT, Kluck RM, Wolf BB, Casiano CA, Newmeyer DD, Wang HG, Reed JC, Nicholson DW, Alnemri ES, Green DR, Martin SJ. Ordering the cytochrome c-initiated caspase cascade: hierarchical activation of caspases-2, -3, -6, -7, -8, and -10 in a caspase-9-dependent manner. J Cell Biol. 1999;144:281–92. doi: 10.1083/jcb.144.2.281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim YH, Lee YJ. TRAIL apoptosis is enhanced by quercetin through Akt dephosphorylation. J Cell Biochem. 2007;100:998–1009. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vivanco I, Sawyers CL. The phosphatidylinositol 3-Kinase AKT pathway in human cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:489–501. doi: 10.1038/nrc839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vousden KH, Lu X. Live or let die: the cell's response to p53. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:594–604. doi: 10.1038/nrc864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yu J, Zhang L. The transcriptional targets of p53 in apoptosis control. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2005;331:851–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.03.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Zong WX, Lindsten T, Ross AJ, MacGregor GR, Thompson CB. BH3-only proteins that bind pro-survival Bcl-2 family members fail to induce apoptosis in the absence of BAX and Bak. Genes Dev. 2001;15:1481–6. doi: 10.1101/gad.897601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Bouillet P, Strasser A. BH3-only proteins - evolutionarily conserved proapoptotic Bcl-2 family members essential for initiating programmed cell death. J Cell Sci. 2002;115:1567–74. doi: 10.1242/jcs.115.8.1567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yee KS, Vousden KH. Contribution of membrane localization to the apoptotic activity of PUMA. Apoptosis. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10495-007-0140-2. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Waterhouse NJ, Ricci JE, Green DR. And all of a sudden it's over: mitochondrial outer-membrane permeabilization in apoptosis. Biochimie. 2002;84:113–21. doi: 10.1016/s0300-9084(02)01379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.El-Deiry WS, Tokino T, Velculescu VE, Levy DB, Parsons R, Trent JM, Lin D, Mercer WE, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. WAF1, a potential mediator of p53 tumor suppression. Cell. 1993;75:817–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90500-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hartwell L. Cell cycle. cAMPing out. Nature. 1994;371:286. doi: 10.1038/371286a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Miyashita T, Reed JC. Tumor suppressor p53 is a direct transcriptional activator of the human BAX gene. Cell. 1995;80:293–9. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90412-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Uo T, Kinoshita Y, Morrison RS. Apoptotic actions of p53 require transcriptional activation of PUMA and do not involve a direct mitochondrial/cytoplasmic site of action in postnatal cortical neurons. J Neurosci. 2007;27:12198–210. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3222-05.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Colman MS, Afshari CA, Barrett JC. Regulation of p53 stability and activity in response to genotoxic stress. Mutat Res. 2000;462:179–88. doi: 10.1016/s1383-5742(00)00035-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Amundson SA, Myers TG, Fornace AJ., Jr Roles for p53 in growth arrest and apoptosis: putting on the brakes after genotoxic stress. Oncogene. 1998;17:3287–99. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yee KS, Vousden KH. Complicating the complexity of p53. Carcinogenesis. 2005;26:1317–22. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgi122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marchenko ND, Zaika A, Moll UM. Death signal-induced localization of p53 protein to mitochondria. A potential role in apoptotic signaling. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:16202–12. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.21.16202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Scorrano L, Oakes SA, Opferman JT, Cheng EH, Sorcinelli MD, Pozzan T, Korsmeyer SJ. BAX and Bak regulation of endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+: a control point for apoptosis. Science. 2003;300:135–9. doi: 10.1126/science.1081208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Park BS, Song YS, Yee SB, Lee BG, Seo SY, Park YC, Kim JM, Kim HM, Yoo YH. Phospho-ser 15-p53 translocates into mitochondria and interacts with Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL in eugenol-induced apoptosis. Apoptosis. 2005;10:193–200. doi: 10.1007/s10495-005-6074-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Nakano K, Vousden KH. PUMA, a novel proapoptotic gene, is induced by p53. Mol Cell. 2001;7:683–94. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(01)00214-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kaeser MD, Iggo RD. Chromatin immunoprecipitation analysis fails to support the latency model for regulation of p53 DNA binding activity in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:95–100. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012283399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Wang P, Yu J, Zhang L. The nuclear function of p53 is required for PUMA-mediated apoptosis induced by DNA damage. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:4054–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Inga A, Storici F, Darden TA, Resnick MA. Differential Transactivation by the p53 Transcription Factor Is Highly Dependent on p53 Level and Promoter Target Sequence. Mol Cell Biol. 2002;22:8612–25. doi: 10.1128/MCB.22.24.8612-8625.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kastan MB, Onyekwere O, Sidransky D, Vogelstein B, Craig RW. Participation of p53 protein in the cellular response to DNA damage. Cancer Res. 1991;51:6304–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Price BD, Hughes-Davies L, Park SJ. Cdk2 kinase phosphorylates serine 315 of human p53 in vitro. Oncogene. 1995;11:73–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Milne DM, Palmer RH, Campbell DG, Meek DW. Phosphorylation of the p53 tumour-suppressor protein at three N-terminal sites by a novel casein kinase I-like enzyme. Oncogene. 1992;7:1361–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hall SR, Campbell LE, Meek DW. Phosphorylation of p53 at the casein kinase II site selectively regulates p53-dependent transcriptional repression but not transactivation. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996;24:1119–26. doi: 10.1093/nar/24.6.1119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Baudier J, Delphin C, Grunwald D, Khochbin S, Lawrence JJ. Characterization of the tumor suppressor protein p53 as a protein kinase C substrate and a S100b-binding protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:11627–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.23.11627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Milne DM, Campbell DG, Caudwell FB, Meek DW. Phosphorylation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by mitogen-activated protein kinases. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:9253–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Milne DM, Campbell LE, Campbell DG, Meek DW. p53 is phosphorylated in vitro and in vivo by an ultraviolet radiation-induced protein kinase characteristic of the c-Jun kinase, JNK1. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:5511–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.10.5511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jamal S, Ziff EB. Raf phosphorylates p53 in vitro and potentiates p53-dependent transcriptional transactivation in vivo. Oncogene. 1995;10:2095–101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shieh SY, Ikeda M, Taya Y, Prives C. DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53 alleviates inhibition by MDM2. Cell. 1997;91:325–34. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80416-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Tibbetts RS, Brumbaugh KM, Williams JM, Sarkaria JN, Cliby WA, Shieh SY, Taya Y, Prives C, Abraham RT. A role for ATR in the DNA damage-induced phosphorylation of p53. Genes Dev. 1999;13:152–7. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.2.152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Waterman MJ, Stavridi ES, Waterman JL, Halazonetis TD. ATM-dependent activation of p53 involves dephosphorylation and association with 14-3-3 proteins. Nat Genet. 1998;19:175–8. doi: 10.1038/542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Sakaguchi K, Herrera JE, Saito S, Miki T, Bustin M, Vassilev A, Anderson CW, Appella E. DNA damage activates p53 through a phosphorylation-acetylation cascade. Genes Dev. 1998;12:2831–41. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.18.2831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Harris SL, Levine AJ. The p53 pathway: positive and negative feedback loops. Oncogene. 2005;24:2899–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Oberley LW, Buettner GR. Role of superoxide dismutase in cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1979;39:1141–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yu JQ, Liu HB, Tian DZ, Liu YW, Lei JC, Zou GL. Changes in mitochondrial membrane potential and reactive oxygen species during wogonin-induced cell death in human hepatoma cells. Hepatol Res. 2007;37:68–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1872-034X.2007.00003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chow JM, Huang GC, Shen SC, Wu CY, Lin CW, Chen YC. Differential apoptotic effect of wogonin and nor-wogonin via stimulation of ROS production in human leukemia cells. J Cell Biochem. 2007 doi: 10.1002/jcb.21528. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Lee WR, Shen SC, Lin HY, Hou WC, Yang LL, Chen YC. Wogonin and fisetin induce apoptosis in human promyeloleukemic cells, accompanied by a decrease of reactive oxygen species, and activation of caspase 3 and Ca(2+)-dependent endonuclease. Biochem Pharmacol. 2002;63:225–36. doi: 10.1016/s0006-2952(01)00876-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]