Abstract

The lag-burst behavior in the action of phospholipase A2 (PLA2) on 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine was investigated at temperatures slightly offset from the main phase transition temperature Tm of this lipid, thus slowing down the kinetics of the activation process. Distinct stages leading to maximal activity were resolved using a combination of fluorescence parameters, including Förster resonance energy transfer between donor- and acceptor-labeled enzyme, fluorescence anisotropy, and lifetime, as well as thioflavin T fluorescence enhancement. We showed that the interfacial activation of PLA2, evident after the preceding lag phase, coincides with the formation of oligomers staining with thioflavin T and subsequently with Congo red. Based on previous studies and our findings here, we propose a novel mechanism for the control of PLA2, involving amyloid protofibrils with highly augmented enzymatic activity. Subsequently, these protofibrils form “mature” fibrils, devoid of activity. Accordingly, the process of amyloid formation is used as an on-off switch to obtain a transient burst in enzymatic catalysis.

INTRODUCTION

Phospholipases A2 (PLA2) represent a ubiquitous group of enzymes serving a number of functions, from toxicity of several venoms to phospholipid metabolism, digestion, cellular signaling, and antimicrobial activity. These enzymes cleave the sn-2 acyl chain from glycerophospholipids to yield lysophospholipids and free fatty acids (FFA), and both their catalytic mechanism and structures are conserved with a high degree of sequence homology between different species, for secretory PLA2s in particular (1,2).

The hallmark of lipolytic enzymes, including PLA2, is the so-called interfacial activation: compared to the hydrolysis of monomeric substrates their activity is dramatically enhanced when reacting with phospholipid interfaces (3), such as those present in micelles, monolayers, and bilayers. Interfacial activation has been explained in terms of two models. The enzyme model assumes a change in the PLA2 conformation is induced by the interface (4), whereas the substrate model assigns the activation to the physicochemical properties of the interface (5). In keeping with the latter mechanism, the activity of PLA2 is influenced by the lipid composition and the phase state of the substrate phospholipids (6). Accordingly, negatively charged phospholipids, vicinity to the main phase transition temperature of the substrate phospholipid, fluid-gel phase coexistence, packing defects (6–9), lipid lateral packing density (10), lipid protrusions (11), and membrane curvature (12,13) all affect the catalytic rate of PLA2.

Additionally, the influence of an electric field (14) and effects by membrane-associating molecules such as adriamycin, quinacrine, amyloid Aβ-peptides (10), platelet activation factor, phorbol esters, polyamines, and antimicrobial peptides (15) have been reported. Changes in PLA2 conformation upon interfacial activation were recently demonstrated using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy, and it was suggested that the enzyme conformational alterations, in unison with the physical state of the substrate, would cause the augmented catalytic activity (16,17). Notably, Hille et al. have previously suggested “superactivation” of PLA2 to be caused by the formation of PLA2 aggregates at interfaces (18), and this was concluded also by Dennis and co-workers (19). Aggregation of PLA2 caused by FFA has been demonstrated in 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC) monolayers (20–22). The detailed characteristics of the enzyme aggregate have not been addressed.

The activity of PLA2 is strongly influenced by the phase state of the substrate. For example, when acting on a saturated phospholipid such as DPPC in the solid-ordered phase and in the vicinity of the main transition temperature Tm, PLA2 exhibits a latency period (γ) in its action, followed by a sudden burst in activity (7). The closer the temperature is to Tm, the shorter is the latency time (8). This behavior has been related to the increase in the number of defects in the bilayer in the solid ordered state upon approaching Tm. The burst in activity has been concluded to involve the dimerization (12,19) and aggregation of PLA2 (18–20), triggered by lateral segregation of a critical mole fraction of reaction products (12).

To assess the aggregation process in more detail, we used Alexa488- and Alexa568-labeled PLA2, constituting a Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) pair (PLA2D and PLA2A, respectively) and thus allowing us to monitor the proximity of the labeled proteins. In addition, changes in the mobility of the enzyme-coupled fluorophores were observed by fluorescence anisotropy. Our fluorescence spectroscopic data demonstrate, in accordance with the previous studies, that oligomerization of PLA2 coincides with the burst in catalytic activity. Intriguingly, these oligomers exhibit augmented fluorescence upon staining with thioflavin T (ThT), indicating that they represent an intermediate stage in the process, resulting in the formation of mature, Congo red staining amyloid. Based on these data we suggest a novel mechanism of enzyme activation by lipids, involving the formation of highly active enzyme oligomers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

DPPC, 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-hydroxy-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (lysoPC), oleic acid (OA), and palmitic acid (PA) were from Avanti Polar Lipids (Alabaster, AL). The purity of lipids was checked by thin layer chromatography on silicic acid coated plates (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) developed with a chloroform/methanol/water mixture (65:25:4, v/v). Examination of the plates after iodine staining revealed no impurities. Bee venom PLA2 and porcine pancreatic PLA2 were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Porcine pancreatic PLA2 zymogen (proPLA2) was kindly provided by Dr. Bert Verheij (University of Utrecht, The Netherlands). Protein purity was verified by polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis in the presence of sodium dodecyl sulfate. Carboxylic acid succinimidyl esters of Alexa568 and Alexa488 were from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR) and rhodamine 101 and fluorescein from Fluka (Glossop, Derbyshire, UK). All other chemicals were of analytical grade and from standard sources. Concentrations of the lipid stock solutions in chloroform were determined gravimetrically with a high precision electrobalance (Cahn, Cerritos, CA), as described in detail by Zhao et al. (23,24). Freshly deionized passed water (Milli RO/Milli Q; Millipore, Jeffrey, NH) was used in all experiments. CaCl2 solutions were filtered through a 0.2 μm filter (Schleicher and Shuell Microscience, Dassel, Germany) and diluted before use to yield a final concentration of 0.1 M.

Preparation of labeled phospholipase A2

Covalent coupling of the indicated fluorophores (Alexa488 and Alexa568) to PLA2 was conducted following the instructions of the manufacturer of these dyes. The concentration of PLA2 was calculated from ultraviolet (UV) spectra using  and a molecular weight of 15,249 (25). The concentrations of carboxylic acid succinimidyl esters of the dyes were determined using molar extinction coefficients of 91,300 M−1 cm−1 (at 578 nm) for Alexa568 and 71,000 M−1 cm−1 (at 495 nm) for Alexa488. Absorption spectra were measured with a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Lambda Bio40 UV/visible, Boston, MA) using 10 mm pathlength quartz cuvettes (Hellma, Essex, UK) and 2 nm bandpass. For labeling, 0.2 mM PLA2 and 0.3 mM dye were reacted for 1 h at 25°C with magnetic stirring and protected from light in a total volume of 100 μl of 100 mM Na2HCO3, pH 8.3. At this pH the dye derivatives couple primarily to aliphatic amines. Prepacked size-exclusion chromatography columns (Biospin 6, Hercules, CA) with an exclusion limit of 6000 D were used to change the buffer to 5 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, and to remove any unreacted dye. The extent of labeling (dye/protein molar ratio) was determined by UV spectroscopy. Correction factors for the extinction coefficients in the determination of the dye content in the labeled enzymes at 280 nm were 0.11 for Alexa488 and 0.46 for Alexa568. The final dye/protein molar ratios were 0.64 for PLA2D (Alexa488) and 0.82 for PLA2A (Alexa568). The labeled enzymes were stored in 20 μl aliquots at −20°C before use.

and a molecular weight of 15,249 (25). The concentrations of carboxylic acid succinimidyl esters of the dyes were determined using molar extinction coefficients of 91,300 M−1 cm−1 (at 578 nm) for Alexa568 and 71,000 M−1 cm−1 (at 495 nm) for Alexa488. Absorption spectra were measured with a spectrophotometer (Perkin Elmer Lambda Bio40 UV/visible, Boston, MA) using 10 mm pathlength quartz cuvettes (Hellma, Essex, UK) and 2 nm bandpass. For labeling, 0.2 mM PLA2 and 0.3 mM dye were reacted for 1 h at 25°C with magnetic stirring and protected from light in a total volume of 100 μl of 100 mM Na2HCO3, pH 8.3. At this pH the dye derivatives couple primarily to aliphatic amines. Prepacked size-exclusion chromatography columns (Biospin 6, Hercules, CA) with an exclusion limit of 6000 D were used to change the buffer to 5 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.5, and to remove any unreacted dye. The extent of labeling (dye/protein molar ratio) was determined by UV spectroscopy. Correction factors for the extinction coefficients in the determination of the dye content in the labeled enzymes at 280 nm were 0.11 for Alexa488 and 0.46 for Alexa568. The final dye/protein molar ratios were 0.64 for PLA2D (Alexa488) and 0.82 for PLA2A (Alexa568). The labeled enzymes were stored in 20 μl aliquots at −20°C before use.

Quantum yields for the above fluorescent proteins were determined relative to rhodamine 101 in methanol (quantum yield = 1) and fluorescein in 0.1 M NaOH (quantum yield = 0.925 (26)). Emission spectra were recorded with a spectrofluorometer (Cary Eclipse, Varian, Mulgrave, Victoria, Australia) using 5-nm bandpasses and subjecting the same samples (total volume of 2 ml in a 10 mm pathlength quartz cuvette) to both absorbance and fluorescence measurements. The fluorophore absorbance was below 0.05 at all excitation wavelengths to avoid inner filter effect. Quantum yields were calculated from

|

(1) |

where Q is the quantum yield of the dye in the labeled protein, I is the integrated fluorescence emission intensity, OD is the optical density of the sample, n is the refractive index of the solution, and QR, ODR, nR, and IR are, respectively, the quantum yields, optical densities, refractive indices, and integrated fluorescence emission intensities for the reference fluorophore solutions (rhodamine 101 and fluorescein). The above equation assumes that the sample and reference are excited at the same wavelength, so it is not necessary to correct for the different excitation intensities at different wavelengths. The quantum yields thus obtained for PLA2D and PLA2A were 0.44 and 0.29, respectively.

The Förster distance Ro for a donor-acceptor pair (in Ångströms) is given by

|

(2) |

where QD is the quantum yield of the donor, J(λ) is the overlap integral for donor emission and acceptor excitation, n is the refractive index of the medium, and κ2 is a factor describing the relative orientation in space of the transition dipoles of the donor and acceptor, usually assumed to be equal to 2/3 (27). For Alexa488- and Alexa568-labeled PLA2s, PLA2D, and PLA2A, respectively, R0 = 54 Å was obtained.

Preparation of large unilamellar vesicles

Appropriate amounts of the DPPC or POPC stock solutions in chloroform were transferred into carefully cleaned glass vials. The solvent was removed under a stream of nitrogen, and the lipid residue was subsequently maintained under reduced pressure for at least 2 h. The dry lipids were then hydrated at 60°C (DPPC) or at 25°C (POPC) for 1 h in water or 5 mM HEPES, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4, as indicated. The resulting dispersions were first irradiated in a bath-type sonicator (NEY Ultrasonik, Bloomfield, CT) for 5 min and then extruded at either 60°C (DPPC) or 25°C (POPC) through a single polycarbonate filter (pore size of 100 nm, Millipore, Bedford, MA) using a low pressure homogenizer (Liposofast, Avestin, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada) to produce large unilamellar vesicles (LUV). The average liposome diameters were determined by dynamic light scattering (Zeta Sizer, Malvern, UK) and were within 91 and 110 nm.

Assessment of the lag-burst behavior in PLA2 reaction

The lag time γ (defined as the latency period between the addition of the enzyme and the burst in the catalytic rate) in the hydrolysis of DPPC by PLA2 was determined by measuring the decrease in pH with a miniature electrode (Microelectrodes, Bedford, NH) inserted into the fluorescence cuvette (see below). The burst was determined as the intersection point of the linear fits to the pH curve during the lag and the initial phase of rapid hydrolysis. The reaction products of PLA2 acting on DPPC are PA and lysoPC, and their formation has been quantitated by high performance liquid chromatography (28). The acidification of the medium as a consequence of PLA2 action is a direct measure for the initiation of the burst in activity and has been extensively used by laboratories investigating this property of PLA2s (8,12).

Importantly, as we wanted only to observe the lag and define the time point of the subsequent burst, we did not correct for the decrement in pH by titration with a base. When indicated, experiments were additionally done in a medium buffered at pH 7.4. Essentially similar changes in the fluorescence of the labeled enzymes were observed under both conditions (see below). As an independent verification of the burst in the PLA2 reaction, changes in 90° light scattering were observed using a spectrofluorometer (12) with the excitation and emission wavelengths set at 500 nm and using 1.5 nm bandpasses. Instead, the use of, for instance, bis-pyrenedecanoyl-PC to monitor the impact of lipid phase behavior on PLA2 action (29) is ambiguous as embedded in a DPPC matrix; these fluorescent lipids are clustered and are preferentially acted upon by PLA2, so their hydrolysis is not representative of the hydrolysis of the matrix (30).

It has been demonstrated in several studies that the accumulation of a critical mole fraction (∼0.10) of reaction products is required for burst (28,31). Subsequent to the burst, very complex and poorly understood reorganization of these products and remaining substrate takes place, being initially in a state of thermodynamic nonequilibrium (28). Accordingly, without structural information on the lipid organization and this mixed lipid phase, quantitative data on the degree of hydrolysis would have very little value and would not aid in the interpretation of our data. The observed differences in γ could result from minor variations in the actual amounts of enzyme added. Likewise, the covalently linked fluorophores could slightly alter the conformation of the protein.

FRET studies

Fluorescence spectra and kinetic traces at fixed wavelengths were recorded with a spectrofluorometer (Cary) in magnetically stirred, 10 mm pathlength, four-window quartz cuvettes thermostated at 40°C. Unless otherwise indicated, all measurements were carried out in a final volume of 1 ml containing 200 μM DPPC LUV in 2 mM CaCl2, with the reactions started by the addition of the indicated PLA2 to yield a final enzyme concentration of 75 nM. Fluorescence of PLA2D was measured with excitation at 460 nm and emission at 520 nm and that for PLA2A with excitation at 560 nm and emission at 600 nm. Bandpasses of 5 nm were used for both the excitation and emission for the above fluorescent proteins. When indicated, fluorescence and pH were recorded simultaneously as a function of time using an in-house written script.

In FRET experiments donor excitation was at 460 nm while observing donor and acceptor emission at 520 nm and 600 nm with bandpasses of 10 and 5 nm, respectively. For FRET the donor- and acceptor-labeled enzymes (PLA2D and PLA2A, respectively) were mixed in a 1:1 molar ratio immediately before their addition to the cuvette containing the DPPC substrate liposomes at the indicated temperature. The relative efficiency of fluorescence resonance energy transfer IFRET between the two fluorescently labeled enzymes was calculated from the emission intensity with correction for the contribution of donor fluorophore emission to the emission of the acceptor (32):

|

(3) |

where RFI520 is the donor fluorescence at 520 nm and RFI600 is the acceptor emission at 600 nm with excitation at 460 nm. All fitting and analysis of fluorescence and absorption spectra was done using dedicated software (OriginLab, Northampton, MA). All measurements were repeated at least three times.

Fluorescence anisotropy

Reactions were started by the addition of DPPC LUV to yield final phospholipid and protein concentrations of 200 μM and 75 nM, respectively. Polarized emission was measured using Polaroid-type filters in the spectrofluorometer (Perkin Elmer LS50B, Boston, MA). The cuvette temperature was maintained at 39°C with a circulating water bath. Excitation was at 525 nm and emission at 605 nm for PLA2A with both excitation and emission bandpasses of 10 nm. The values for r were calculated from

|

(4) |

where I‖ and  are the parallel and perpendicular, respectively, components of fluorophore emission with respect to the direction of the polarized excitation. The G-factor correction was performed by an in-house written script embedded into the software provided by the instrument manufacturer. The lag time γ was determined by measuring the decrease in pH with a microelectrode inserted into the cuvette. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were repeated three times.

are the parallel and perpendicular, respectively, components of fluorophore emission with respect to the direction of the polarized excitation. The G-factor correction was performed by an in-house written script embedded into the software provided by the instrument manufacturer. The lag time γ was determined by measuring the decrease in pH with a microelectrode inserted into the cuvette. Fluorescence anisotropy measurements were repeated three times.

Determination of fluorescence lifetimes

Fluorescence lifetimes were measured using a commercial laser spectrometer with stroboscopic gated detection (Photon Technology International, Ontario, Canada). The minimum lifetime accessible to the instrument is 200 ps. A train of 500 ps excitation pulses at 337 nm and at a repetition rate of 10 Hz was produced by a nitrogen laser, pumping 10 mM solutions of PLD500 or PLD536 dyes (Photon Technology International) in ethanol and with maximum emission at 500 nm and 536 nm, respectively. For PLA2A, excitation was at 540 nm and emission at 600 nm. Emission bandpass was set at 5 nm, with the emission wavelengths selected by a monochromator.

A microelectrode was inserted in the magnetically stirred cuvette to monitor the burst in enzyme activity with an external pH meter (MPC227, Mettler Toledo, Glostrup, Denmark). The cuvette temperature was maintained at 36°C using a circulating water bath and was measured continuously by a probe (Omega HH42, Stamford, CT) immersed into the adjacent cuvette in the cuvette holder of the spectrofluorometer. Reactions were started by the addition of the PLA2 to yield final lipid and protein concentrations of 200 μM and 75 nM, respectively. Each lifetime value represents one measurement where a fluorescence decay curve was fitted to the sum of exponentials and analyzed by the nonlinear least squares method. The data shown were selected based on quality control by a χ2 test typically producing a reduced χ2 value of 0.8–1.5.

Thioflavin T fluorescence

ThT emission was measured with a spectrofluorometer (Cary) in magnetically stirred 10 mm pathlength, four window quartz cuvettes thermostated at 40°C. These measurements were carried out in a final volume of 1 ml containing 200 μM DPPC LUV in 2 mM CaCl2 and 6 μM dye, with the reactions started by the addition of PLA2 to yield a final enzyme concentration of 75 nM. When indicated, the medium was 5 mM HEPES, pH 7.4. Excitation was at 450 nm and emission at 482 nm, with the respective bandpasses of 2.5 and 10 nm. Kinetics were recorded using a script provided by the manufacturer. Fluorescence emission values were corrected by subtracting scattering recorded under identical conditions except for the absence of ThT.

Microscopy

The procedure we described previously for the formation of amyloid-like fibrils by proteins associating with acidic phospholipids (23) was employed to study the indicated lipolytic enzymes. In these experiments the proteins were in 5 mM HEPES and 0.1 mM EDTA buffer, pH 7.4, with the indicated lipids added in the same buffer to yield final protein and lipid concentrations of 75 nM and 200 μM, respectively. In some experiments lysoPC/PA (2:1 molar ratio) dispersions were mixed with the indicated PLA2s to yield final concentrations of 0.2 mg/ml and 100 μM, of protein and lipid, respectively After 1 h of incubation, the samples were observed on an inverted microscope (Olympus IX 70, Olympus Optical, Tokyo, Japan) using differential interference contrast (DIC) optics for brightfield images or crossed polarizers in the excitation and emission for birefringence. When indicated, the fibers were additionally incubated for 30 min with 10 μM Congo red in 20 mM HEPES and 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4. All experiments were carried out at room temperature (∼24°C).

Fibers stained by ThT (6 μM final concentration) were observed using an inverted microscope (Zeiss IM-35, Jena, Germany) and either brightfield illumination or with a λex= 436 nm interference bandpass filter and a λem = 470 nm interference long-pass filter for ThT fluorescence. Images were acquired from the microscope fitted with a digital camera (DS6031, Canon Europe, Amsterdam, The Netherlands). Samples were prepared in 96-well plates (Greiner Bio-one, Essen, Germany) with transparent bottoms suitable for observation with an inverted microscope. Formation of fibers was confirmed by examining eight wells with identical samples containing both liposomes and the enzyme against eight control samples containing buffer or buffer and liposomes. The experiments were repeated three times, with a number of fibers consistently appearing in the samples. No fibers were observed in the negative controls. Additionally, fibers were isolated from fluorometer cuvettes after the completion of the reaction with the DPPC substrate. When indicated the fibers were subsequently stained by Congo red for birefringence imaging by microscopy with crossed polarizers, as described above.

RESULTS

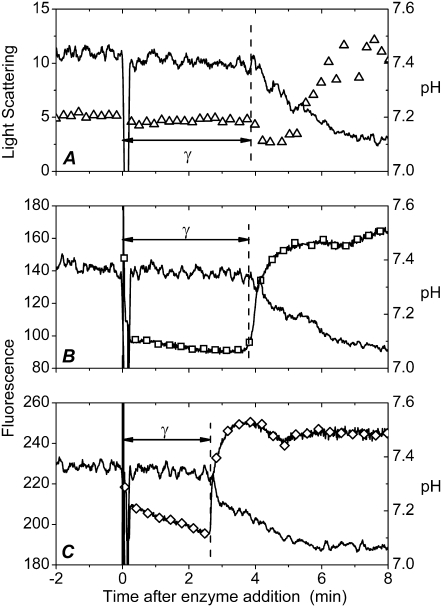

Similar to the other PLA2s, the bee venom enzyme showed a distinct lag in its action on DPPC, and under the conditions employed here (viz. 200 μM DPPC, 75 nM PLA2, and T = 40°C) a latency period of 3–3.5 min preceded the burst in activity (Fig. 1, A–C). The burst was accompanied by an increase in light scattering, thus revealing alterations in lipid organization due to the reaction products, lysoPC and PA (12). To study if the covalent coupling of fluorescent dyes to PLA2 interfered with the lag-burst behavior, the above experiments were repeated using PLA2D and PLA2A, labeled with Alexa488 (FRET donor) and Alexa568 (acceptor), respectively. Importantly, both fluorophore-labeled enzymes exhibited under these conditions a lag of ∼3 min, which is comparable to that for the native enzyme (Fig. 1, B and C). Accordingly, although the covalent labeling introduces an extra moiety to the protein, the characteristic lag-burst behavior is retained, thus validating the use of these PLA2 derivatives for the purposes of this study.

FIGURE 1.

Catalytic activity and fluorescence of Alexa488- and Alexa568-tagged phospholipases A2. The hydrolysis of the DPPC substrate was monitored as a function of time by decrease in pH (solid lines in A–C). (A) Changes in 90° light scattering (▵). (B) Fluorescence of PLA2A, λex = 560 nm, λem = 600 nm (□), and (C) fluorescence of PLA2D, λex = 460 nm, λem = 520 nm (⋄). Lipid concentration was 200 μM in 2 mM CaCl2. Temperature was maintained at 40°C. The reactions were started by the addition of the indicated enzyme to yield a final concentration of 75 nM in a total volume of 1 ml. The vertical dashed lines mark the burst in enzyme activity revealed by the onset of the fall in pH (solid line).

Both PLA2D and PLA2A exhibited a pronounced, sharp increase in their fluorescence at burst (Fig. 1, B and C). Although the origin of this increment is uncertain at this stage, it is in keeping with the suggested changes in enzyme conformation at burst, observed previously also for the intrinsic Trp fluorescence of PLA2 (12,33). A similar increase in fluorescence intensity is evident when labeled enzymes are reacted with 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), which is in the liquid-disordered state. In contrast, for this lipid, there is no latency period in the enzyme action, and the burst in activity is observed immediately (within seconds) after the enzyme addition. For POPC the overall extent of hydrolysis is less, with a significantly smaller overall decrement in pH (Supplementary Material, Data S1).

To this end, bee venom PLA2 was chosen for this study, as it has been shown to bind to lipid membranes by nonelectrostatic interactions with no preference for negatively charged phospholipids over zwitterionic ones (25). Therefore, although the two fluorescent labels we used are expected to react with Lys residues, this should have an insignificant effect on the primary enzyme-substrate interaction between the labeled PLA2s and DPPC. This notion is supported by the observed similar lag-burst behaviors of the native enzyme and those containing the covalently linked fluorophores (Fig. 1), thus validating our approach.

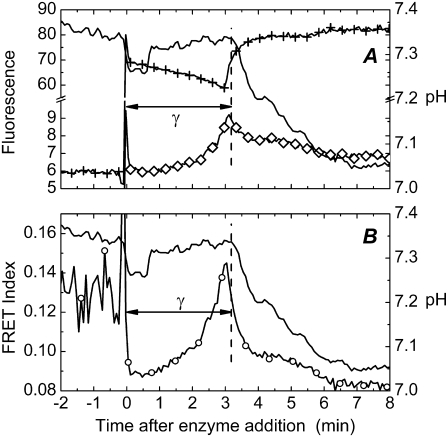

Dimer formation and enzyme aggregation have been concluded to be associated with the activation of PLA2 in interfaces (12,18,19). Aggregation of PLA2 has been demonstrated in DPPC monolayers (20). To pursue enzyme-enzyme interactions during the lag-burst behavior in more detail, we first utilized FRET between the Alexa488- and Alexa568-labeled enzymes, constituting a donor-acceptor pair, PLA2D and PLA2A, respectively. The two labeled proteins were mixed immediately before their addition to the cuvette containing the DPPC substrate, after which FRET was monitored as a function of time, with simultaneous measurement of pH to observe the burst (Fig. 2). An increase in FRET is seen with time, reaching a maximum at burst (Fig. 2, B). FRET is evident also as a slight decrease and increase, respectively, in the donor and acceptor emission (Fig. 2 A). The observed energy transfer readily complies with PLA2 dimerization or oligomerization bringing the donor- and acceptor-labeled enzyme molecules into proximity.

FIGURE 2.

Time course for FRET between PLA2D and PLA2A during hydrolysis of DPPC liposomes. (A) Emission of PLA2A at λ = 600 nm (⋄) upon excitation at λ = 460 nm of PLA2D. Emission of PLA2D at λ = 520 nm (+) upon excitation at λ = 460 nm. (B) Relative FRET efficiency (○) calculated according to Eq. 3. Conditions were as described for Fig. 1, except for using 32.5 nM of PLA2D and PLA2A each. The vertical dashed line marks the burst in activity, with pH shown as solid lines.

More specifically, FRET occurs if the distance between the donor and acceptor fluorophores is on the order of the so-called Förster radius (R0), a critical distance determined by the spectroscopic properties of the interacting fluorophores. In practice, FRET can be detected when the distance between the dyes is < 2 × R0 (27). The Förster radius for the Alexa dyes used was calculated to be 5.4 nm (see Materials and Methods). This means that the distance between PLA2 molecules at the end of the lag phase and at the burst of activity are, on average, below 11 nm. On the other hand, for a uniform distribution the average distance between PLA2 molecules on the liposome surface would be ∼30 nm (Data S1). Thus, the sole fact that we see FRET demonstrates a nonuniform distribution of PLA2 on the membrane surface. Although FRET efficiency can also be affected to some extent by changes in protein orientation and localization with respect to the membrane surface, these latter effects alone cannot account for noticeable FRET, assuming uniform PLA2 distribution. FRET was also observed when using unsaturated POPC substrate; but similar to the burst in activity, it was observed immediately after the enzyme addition to the substrate (Data S1).

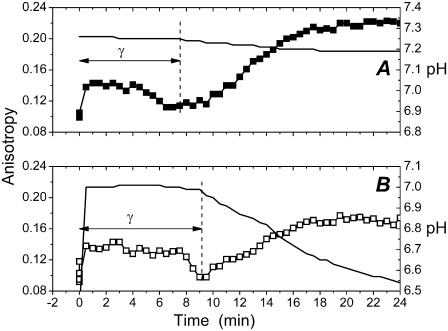

To gain further insight into the molecular events underlying the observed changes in fluorescence, we measured fluorescence anisotropy (r) for the Alexa568-labeled PLA2. The addition of DPPC LUV to a solution containing PLA2A caused a very rapid (within seconds) increment in fluorescence anisotropy (Fig. 3), revealing a fast binding of the labeled PLA2 to the substrate. Values for anisotropy then remained approximately constant for the most part of the latency period, thus confirming that the buildup of FRET is not caused by progressive binding of PLA2 to the substrate but results from protein-protein contacts, as expected for dimers and oligomers. The decrease in anisotropy immediately preceding the burst in activity (Fig. 3) complies with the augmented segmental motions of PLA2 and the loosening of its tertiary structure (16,17).

FIGURE 3.

Changes in the emission anisotropy for Alexa568-labeled PLA2 (PLA2A) in 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 (A, ▪), and in unbuffered 2 mM CaCl2 (B, □). In both panels pH is indicated with a solid line. Protein concentration was 75 nM in 2 mM CaCl2. The reactions were started by the addition of the lipid to yield a final concentration of 200 μM. The reaction was carried out at 39°C. The vertical dashed lines mark the burst in enzyme activity revealed by the onset of the fall in pH.

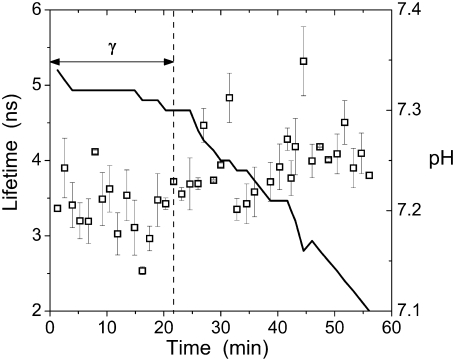

Intriguingly, after its maximum at burst, FRET declines (Fig. 2 B), suggesting a priori diminishing protein-protein contacts. However, this loss of FRET coincides with the onset of an increase in anisotropy (Fig. 3). To confirm that the observed changes in fluorescence anisotropy were indeed caused by changes in the mobility of the fluorophore and not due to variation (decrease) in the fluorescence lifetime (27), we measured the latter at different stages of the activation process (Fig. 4), under conditions identical to those used in the anisotropy measurements. The variation of the lifetime did not exceed ∼25% and was not correlated to the anisotropy changes (cf. Figs. 3 and 4). Moreover (27), the slightly prolonged lifetimes seen after the burst point (Fig. 4) should lead to an apparent decrease of fluorescence anisotropy. In contrast, we observe an increase. Therefore, the reduction of anisotropy at the end of the lag phase and its enhancement after the burst can be explained only by changes in the molecular mobility of the PLA2-tagged fluorophore.

FIGURE 4.

Fluorescence lifetimes τ for PLA2A (□) monitored in the course of the enzyme action on DPPC liposomes. To prolong the lag time γ in this experiment, the reaction was carried out at 36°C. Final lipid and protein concentrations were 200 μM and 75 nM, respectively, in 2 mM CaCl2. Changes in pH are indicated with a solid line.

Because PLA2 at this point is membrane bound, the most likely reason for the anisotropy increase is aggregation of the enzyme in the interface. Accordingly, dimers (revealed by FRET) would only exist transiently, as an intermediate preceding the formation of higher order oligomers revealed by the increase in anisotropy. The onset of aggregation involves a change in enzyme conformation as signaled by the increment in the emission from the two fluorophores (Fig. 1, B and C). To exclude the possibility that the increase in r was caused by the decrease in pH, we also measured r in a medium with pH buffered at 7.4 (Fig. 3 A). Under these conditions we cannot verify the burst in activity by a decrease in pH; however, there is no reason to assume the lag-burst behavior to be affected, in particular as all features observed in unbuffered 2 mM CaCl2 (i.e., changes in emission anisotropy, an increase in bvPLA2A fluorescence, changes in scattering, and a maximum of FRET) also appear in a medium buffered at pH 7.4.

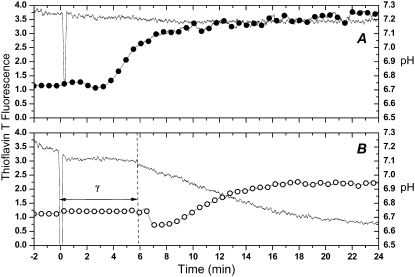

In light of oligomerization the loss of FRET after the burst is enigmatic. However, poor FRET efficiency has been reported for amyloid aggregates (34). Reasons for this are at present poorly understood. Interestingly, the burst in activity was accompanied by enhanced fluorescence for ThT, a marker for amyloid-like fibrils (Fig. 5). The ThT fluorescence intensity remained constant at the background level during the lag period and then increased for the first 2–4 min of the burst, reaching a plateau with intensity two to four times higher than the background. The moderate ThT fluorescence enhancement is readily expected because of the low (75 nM) concentration of the protein, which was necessary to achieve a latency period lasting for several minutes and thus allowing easy collection of fluorescence spectroscopy data. ThT fluorescence is sensitive to pH and is reduced under acidic conditions (35). As expected a more substantial enhancement of fluorescence is observed in our system when base was added after the PLA2 reaction in an unbuffered medium. Likewise, ThT fluorescence was further enhanced using a buffered (pH 7.4) medium (Fig. 5 A). To conclude, the burst in PLA2 activity is temporally correlated with a progressive reduction in the mobility of PLA2-coupled fluorophores (increase of anisotropy) and with the abrupt increase in ThT fluorescence. These data can be rationalized by the formation of amyloid-like PLA2 aggregates possessing high catalytic activity.

FIGURE 5.

ThT fluorescence during the burst of PLA2 activity. Excitation was at λex= 450 nm and λem= 482 nm. (A) 5 mM HEPES, 2 mM CaCl2, 0.1 mM EDTA, pH 7.4 (•). (B) Unbuffered 2 mM CaCl2 (○). Lipid concentration was 200 μM with 6 μM ThT in 2 mM CaCl2. The reactions were started by the addition of PLA2 to a final concentration of 75 nM and were carried out at 40°C.

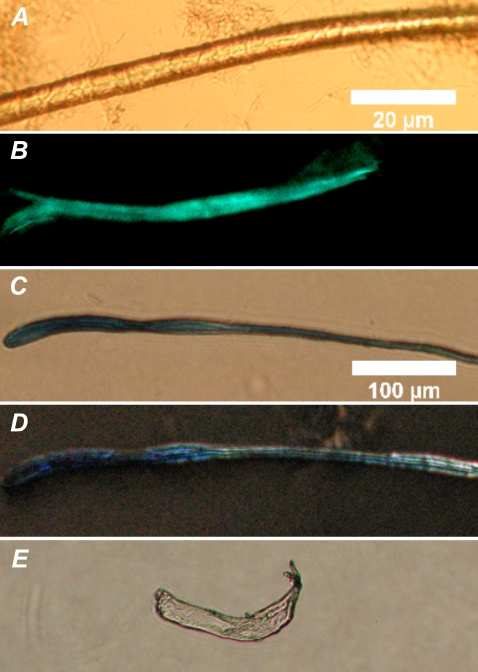

The formation of macroscopic fibrils that yielded the light green birefringence characteristic for amyloid upon Congo red staining was seen for both the native bee venom enzyme and the fluorescent PLA2s after incubation with the DPPC substrate (Fig. 6, A and B). Similar to Congo red staining, birefringent fibrils were also observed after incubating these enzymes with the reaction products (PA and lysoPC, data not shown). Similar fibrils were observed for these enzymes in the presence of the unsaturated lipid, POPC, and its hydrolysis products (see Fig. S4 in Data S1). Congo red staining fibrils were also formed by the porcine pancreatic PLA2 upon incubation with the above products from the hydrolysis of DPPC (Fig. 6, C and E). Of interest in this context is the proPLA2, which has seven additional amino acids in its N-terminal sequence and does not exhibit interfacial activation. Importantly, although proPLA2 also aggregates in the presence of the reaction products (Fig. 6 D), it does not develop the typical light green birefringence upon Congo red staining. To this end, the aggregates formed by the zymogen have been shown to be different from those of the active porcine pancreatic PLA2 (18,36).

FIGURE 6.

Fibers formed by reacting DPPC with phospholipases A2. Brightfield microscopy image (A), and fluorescence image after ThT staining (B) for bee venom PLA2, DIC microscopy images for porcine pancreatic PLA2 (C) and porcine pancreatic PLA2 zymogen, proPLA2 (D), and birefringence for porcine pancreatic PLA2 after Congo red staining (E, the same fiber as in C). Lipid and the indicated enzymes were mixed at ambient temperature (∼24°C) in 5 mM HEPES, and 0.1 mM EDTA pH 7.4, to yield final concentrations of 100 μM and 0.2 mg/mL, respectively. The scale bars correspond to 20 μm (A and B) and 100 μm (C–E).

DISCUSSION

In light of the overall similarity of the behaviors of secretory PLA2s and for the sake of brevity, we will discuss the results on this study and previous data from other laboratories in terms of a “generic” PLA2. Our findings on the organization and structural dynamics of PLA2 in the course of its activation reveal several intriguing and, to our knowledge, new characteristics.

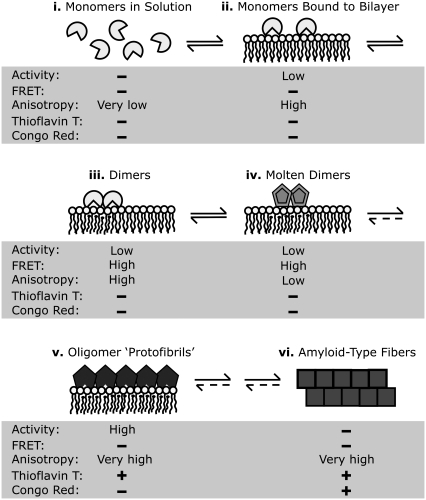

We rationalize our data in terms of the following mechanistic sequence to explain the lag-burst behavior and the interfacial activation of PLA2 (Fig. 7). More specifically, i), the soluble enzyme first rapidly binds to the substrate; ii), revealed by the fast (within seconds) increase in emission anisotropy (Fig. 3). The bound enzyme initially exerts only modest catalytic activity (22). iii), After the binding of PLA2 to the surface, a slow dimerization of the enzyme takes place, evident as augmented FRET (Fig. 2), accompanied by a slow accumulation of the reaction products (28,31). The rate of dimer formation is likely to be limited by the fluctuations in the vicinity to the substrate phospholipid transition temperature Tm (9). iv), Toward the end of the latency period there is a slow decrease in the emission anisotropy (Fig. 3), in keeping with the loosening of the tertiary structure of PLA2 (16,17) and augmented segmental motions of the domains in PLA2 containing the covalently coupled fluorophore. This change in structural dynamics is caused by the locally accumulated negatively charged FFA (22). To this end, transition into the molten globule state upon binding to acidic phospholipid-containing membranes has been reported for cytochrome c and α-lactalbumin (37,38), followed by the formation of amyloid-type fibrils (23,39). v), After the latency period a burst in the activity of PLA2 takes place. We suggest a critical local concentration of low molecular weight oligomers in the “molten globule” state to lead to the nucleation of formation of higher order oligomers, evident as a pronounced increase in anisotropy (Fig. 3). This process is preceded by a fast change in PLA2 conformation, signaled by an increment in the fluorescence of the labeled enzymes (Fig. 1). The highly active oligomers produce enhanced fluorescence upon ThT staining and are thus likely to represent amyloid protofibrils. With time the latter develop into vi), amyloid fibers exhibiting the characteristic birefringence (40) upon Congo red staining and blue-green fluorescence upon ThT staining (Fig. 6). These fibrils are likely to be devoid of enzymatic activity. To this end, it is of interest that Callisen and Talmon observed in their cryo-electron-microscopy study the presence of fibrillar structures upon incubation of DPPC LUV with PLA2 (28). Although these structures were interpreted as edge-on flattened bilayer discs, it is possible that they actually represent PLA2 fibrils.

FIGURE 7.

A schematic model for the activation of PLA2 in the course of action on DPPC: (i) monomeric PLA2 in solution, (ii) binding of monomeric PLA2 to the substrate interface, (iii) slow dimerization of PLA2 during the lag phase, (iv) formation of “molten dimers” before the burst, (v) formation of protofibrillar oligomers of PLA2 with high catalytic activity, and (vi) emergence of amyloid-like fibrils. The levels of activity and fluorescence reporter parameters are indicated for each stage. See text for details.

Importantly, Congo red staining fibrils were also formed by the porcine pancreatic PLA2 in the presence of the reaction products (Fig. 6 C). In contrast, aggregates formed by the proPLA2 (Fig. 6 D) did not demonstrate the characteristic light green birefringence upon Congo red staining (data not shown). Hille et al. reported the aggregates formed by proPLA2 to be different from those of the active PLA2 (18,36). As proPLA2 does not exhibit interfacial activation (3,36), our findings support the notion that the interfacial activation and the formation of amyloid-type fibers are related. The formation of the macroscopic fibers (Fig. 6) must involve oligomerization as an early step. Alakoskela et al. demonstrated that a protein can be trapped into the fibrils in different conformations, varying from native structures to amyloid (39). In this context the high number of conserved intermolecular disulphide bridges in PLA2 (2) is significant, as they can be expected to restrict lipid-induced conformational changes to affect specific regions of the protein, to steer the protein along a predetermined pathway in the folding energy landscape.

Amyloid fibrils maintained by extensive β-sheets represent the free energy minimum for aggregated proteins and are recognized as the causative factor for a number of major disorders, such as Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease and type II diabetes (41). Yet, amyloid formation seems to also serve nonpathological functions, and even in the above pathological conditions the mature fibrils may serve a protective function by trapping the actual toxic protofibrils into these more macroscopic and inert aggregates (42). We have recently demonstrated that antimicrobial peptides as well as several cytotoxic proteins form amyloid-type fibrils in the presence of acidic phospholipids, and we have suggested their membrane permeabilizing mechanism to be the same as that for the pathological cytotoxic peptides such as Aβ in Alzheimer's disease (23,24,43). In this context the catalytically inactive, yet toxic PLA2s are of interest (44). More specifically, these proteins have been shown to exert cytotoxicity by a mechanism involving membrane permeabilization. In light of our findings here it would seem feasible that these catalytically inactive PLA2-toxins would have evolved from the active enzymes, retaining the ability to form membrane-damaging protofibrils.

Intriguingly, amyloid structures have also been concluded to serve physiological functions in memory (45,46) and epigenetic heritance (47). Our findings widen the functional repertoire of amyloid-type protein fibrils and suggest that they are also involved in the control of lipid-bound enzymes. In light of parallel findings revealing the importance of enzyme aggregation in the activation of protein kinase C by lipids (48,49), it is tempting to speculate that this mechanism may be much more general. To this end, it is intriguing that the PLA2 activating antimicrobial peptides (15) also form amyloid fibrils (24,50). Likewise, the region of apolipoprotein C-II causing activation of lipoprotein lipase is also responsible for the profound tendency of this peptide to form amyloid (51,52). Our preliminary results support the view that the activation of this lipolytic enzyme by these peptides may involve the formation of heterooligomers of enzyme and the peptide. These studies will be reported in a future publication.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view all of the supplemental files associated with this article, visit www.biophysj.org.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Juha-Matti Alakoskela for his help with automated fluorescence measurements and advice in computing and Kaija Niva and Kristiina Söderholm for technical assistance. The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Helsinki Biophysics and Biomembrane Group is supported by grants from the Marie Curie EST Training Network (C.C.), Marie Curie Incoming International Fellowship (Y.D.), the Academy of Finland, and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation.

Editor: Paul H. Axelsen.

References

- 1.Scott, D. L., S. P. White, Z. Otwinowski, W. Yuan, M. H. Gelb, and P. B. Sigler. 1990. Interfacial catalysis: the mechanism of phospholipase A2. Science. 250:1541–1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Six, D. A., and E. A. Dennis. 2000. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A(2) enzymes: classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1488:1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pieterson, W. A., J. C. Vidal, J. J. Volwerk, and G. H. de Haas. 1974. Zymogen-catalyzed hydrolysis of monomeric substrates and the presence of a recognition site for lipid-water interfaces in phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 13:1455–1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Verger, R., M. C. Mieras, and G. H. de Haas. 1973. Action of phospholipase A at interfaces. J. Biol. Chem. 248:4023–4034. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wells, M. A. 1974. The mechanism of interfacial activation of phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 13:2248–2257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Op den Kamp, J. A., M. T. Kauerz, and L. L. van Deenen. 1975. Action of pancreatic phospholipase A2 on phosphatidylcholine bilayers in different physical states. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 406:169–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apitz-Castro, R., M. K. Jain, and G. H. de Haas. 1982. Origin of the latency phase during the action of phospholipase A2 on unmodified phosphatidylcholine vesicles. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 688:349–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Honger, T., K. Jorgensen, R. L. Biltonen, and O. G. Mouritsen. 1996. Systematic relationship between phospholipase A2 activity and dynamic lipid bilayer microheterogeneity. Biochemistry. 35:9003–9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hoyrup, P., O. G. Mouritsen, and K. Jorgensen. 2001. Phospholipase A(2) activity towards vesicles of DPPC and DMPC-DSPC containing small amounts of SMPC. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1515:133–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lehtonen, J. Y., J. M. Holopainen, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 1996. Activation of phospholipase A2 by amyloid β-peptides in vitro. Biochemistry. 35:9407–9414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Halperin, A., and O. G. Mouritsen. 2005. Role of lipid protrusions in the function of interfacial enzymes. Eur. Biophys. J. 34:967–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bell, J. D., and R. L. Biltonen. 1989. The temporal sequence of events in the activation of phospholipase A2 by lipid vesicles. Studies with the monomeric enzyme from Agkistrodon piscivorus piscivorus. J. Biol. Chem. 264:12194–12200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leidy, C., O. G. Mouritsen, K. Jorgensen, and G. H. Peters. 2004. Evolution of a rippled membrane during phospholipase A2 hydrolysis studied by time-resolved AFM. Biophys. J. 87:408–418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thuren, T., A. P. Tulkki, J. A. Virtanen, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 1987. Triggering of the activity of phospholipase A2 by an electric field. Biochemistry. 26:4907–4910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao, H., and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2003. Modulation of the activity of secretory phospholipase A2 by antimicrobial peptides. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47:965–971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tatulian, S. A., R. L. Biltonen, and L. K. Tamm. 1997. Structural changes in a secretory phospholipase A2 induced by membrane binding: a clue to interfacial activation? J. Mol. Biol. 268:809–815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tatulian, S. A. 2001. Toward understanding interfacial activation of secretory phospholipase A2 (PLA2): membrane surface properties and membrane-induced structural changes in the enzyme contribute synergistically to PLA2 activation. Biophys. J. 80:789–800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hille, J. D., M. R. Egmond, R. Dijkman, M. G. van Oort, B. Jirgensons, and G. H. de Haas. 1983. Aggregation of porcine pancreatic phospholipase A2 and its zymogen induced by submicellar concentrations of negatively charged detergents. Biochemistry. 22:5347–5353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hazlett, T. L., R. A. Deems, and E. A. Dennis. 1990. Activation, aggregation, inhibition and the mechanism of phospholipase A2. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 279:49–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grainger, D. W., A. Reichert, H. Ringsdorf, and C. Salesse. 1990. Hydrolytic action of phospholipase A2 in monolayers in the phase transition region: direct observation of enzyme domain formation using fluorescence microscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1023:365–379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Maloney, K. M., M. Grandbois, C. Salesse, D. W. Grainger, and A. Reichert. 1996. Membrane microstructural templates for enzyme domain formation. J. Mol. Recognit. 9:368–374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Burack, W. R., M. E. Gadd, and R. L. Biltonen. 1995. Modulation of phospholipase A2: identification of an inactive membrane-bound state. Biochemistry. 34:14819–14828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhao, H., E. K. Tuominen, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2004. Formation of amyloid fibers triggered by phosphatidylserine-containing membranes. Biochemistry. 43:10302–10307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zhao, H., A. Jutila, T. Nurminen, S. A. Wickstrom, J. Keski-Oja, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2005. Binding of endostatin to phosphatidylserine-containing membranes and formation of amyloid-like fibers. Biochemistry. 44:2857–2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ghomashchi, F., Y. Lin, M. S. Hixon, B. Z. Yu, R. Annand, M. K. Jain, and M. H. Gelb. 1998. Interfacial recognition by bee venom phospholipase A2: insights into nonelectrostatic molecular determinants by charge reversal mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 37:6697–6710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Majumdar, Z. K., R. Hickerson, H. F. Noller, and R. M. Clegg. 2005. Measurements of internal distance changes of the 30S ribosome using FRET with multiple donor-acceptor pairs: quantitative spectroscopic methods. J. Mol. Biol. 351:1123–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lakowicz, J. R. 1999. Principles of Fluorescence Spectroscopy, 2nd ed. Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York. 302–307.

- 28.Callisen, T. H., and Y. Talmon. 1998. Direct imaging by cryo-TEM shows membrane break-up by phospholipase A2 enzymatic activity. Biochemistry. 37:10987–10993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ray, S., J. L. Scott, and S. A. Tatulian. 2007. Effects of lipid phase transition and membrane surface charge on the interfacial activation of phospholipase A2. Biochemistry. 46:13089–13100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hoyrup, P. 2001. Phospholipase A2 activity in relation to the physical properties of lipid bilayers. PhD thesis. Technical University of Denmark, Kgs. Lyngby. p. 130.

- 31.Burack, W. R., and R. L. Biltonen. 1994. Lipid bilayer heterogeneities and modulation of phospholipase A2 activity. Chem. Phys. Lipids. 73:209–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arai, R., H. Ueda, K. Tsumoto, W. C. Mahoney, I. Kumagai, and T. Nagamune. 2000. Fluorolabeling of antibody variable domains with green fluorescent protein variants: application to an energy transfer-based homogeneous immunoassay. Protein Eng. 13:369–376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pande, A. H., S. Qin, K. N. Nemec, X. He, and S. A. Tatulian. 2006. Isoform-specific membrane insertion of secretory phospholipase A2 and functional implications. Biochemistry. 45:12436–12447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dusa, A., J. Kaylor, S. Edridge, N. Bodner, D. P. Hong, and A. L. Fink. 2006. Characterization of oligomers during α-synuclein aggregation using intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence. Biochemistry. 45:2752–2760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khurana, R., C. Coleman, C. Ionescu-Zanetti, S. A. Carter, V. Krishna, R. K. Grover, R. Roy, and S. Singh. 2005. Mechanism of thioflavin T binding to amyloid fibrils. J. Struct. Biol. 151:229–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hille, J. D., M. R. Egmond, R. Dijkman, M. G. van Oort, P. Sauve, and G. H. de Haas. 1983. Unusual kinetic behavior of porcine pancreatic (pro)phospholipase A2 on negatively charged substrates at submicellar concentrations. Biochemistry. 22:5353–5358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Muga, A., H. H. Mantsch, and W. K. Surewicz. 1991. Membrane binding induces destabilization of cytochrome c structure. Biochemistry. 30:7219–7224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Banuelos, S., and A. Muga. 1995. Binding of molten globule-like conformations to lipid bilayers. Structure of native and partially folded α-lactalbumin bound to model membranes. J. Biol. Chem. 270:29910–29915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Alakoskela, J. M., A. Jutila, A. C. Simonsen, J. Pirneskoski, S. Pyhäjoki, R. Turunen, S. Marttila, O. G. Mouritsen, E. Goormaghtigh, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2006. Characteristics of fibers formed by cytochrome c and induced by anionic phospholipids. Biochemistry. 45:13447–13453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puchtler, H., and F. Sweat. 1965. Congo red as a stain for fluorescence microscopy of amyloid. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 13:693–694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rochet, J. C., and P. T. Lansbury Jr. 2000. Amyloid fibrillogenesis: themes and variations. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 10:60–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chiti, F., and C. M. Dobson. 2003. Protein aggregation and aggregate toxicity: new insights into protein folding, misfolding diseases and biological evolution. J. Mol. Med. 81:678–699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zhao, H., R. Sood, A. Jutila, S. Bose, G. Fimland. J. Nissen-Meyer, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2006. Interaction of the antimicrobial peptide pheromone plantaricin A with model membranes: implications for a novel mechanism of action. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1758:1461–1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tsai, I. H. 2007. Evolutionary reduction of enzymatic activities of snake venom phospholipases. Toxicol. Rev. 26:123–142. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Si, K., S. Lindquist, and E. R. Kandel. 2003. A neuronal isoform of the aplysia CPEB has prion-like properties. Cell. 115:879–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Si, K., M. Giustetto, A. Etkin, R. Hsu, A. Janisiewicz, M. Miniaci, J. Kim, H. Zhu, and E. R. Kandel. 2003. A neuronal isoform of CPEB regulates local protein synthesis and stabilizes synapse-specific long-term facilitation in aplysia. Cell. 115:893–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Paushkin, S. V., V. V. Kushnirov, V. N. Smirnov, and M. D. Ter-Avanesyan. 1996. Propagation of the yeast prion-like [ψ+] determinant is mediated by oligomerization of the SUP35-encoded polypeptide chain release factor. EMBO J. 15:3127–3134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bazzi, M. D., and G. L. Nelsestuen. 1992. Autophosphorylation of protein kinase C may require a high order of protein-phospholipid aggregates. J. Biol. Chem. 267:22891–22896. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang, S. M., P. S. Leventhal, G. J. Wiepz, and P. J. Bertics. 1999. Calcium and phosphatidylserine stimulate the self-association of conventional protein kinase C isoforms. Biochemistry. 38:12020–12027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sood, R., Y. Domanov, and P. K. J. Kinnunen. 2007. Fluorescent temporin B derivative and its binding to liposomes. J. Fluoresc. 17:223–234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kinnunen, P. K. J., R. L. Jackson, L. C. Smith, A. M. Gotto Jr., and J. T. Sparrow. 1977. Activation of lipoprotein lipase by native and synthetic fragments of human plasma apolipoprotein C-II. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 74:4848–4851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wilson, L. M., Y. F. Mok, K. J. Binger, M. D. Griffin, H. D. Mertens, F. Lin, J. D. Wade, P. R. Gooley, and G. J. Howlett. 2007. A structural core within apolipoprotein C-II amyloid fibrils identified using hydrogen exchange and proteolysis. J. Mol. Biol. 366:1639–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]