Abstract

BACKGROUND

Despite the aging of the population, little is known about the sexual behaviors and sexual function of older people.

METHODS

We report the prevalence of sexual activity, behaviors, and problems in a national probability sample of 3005 U.S. adults (1550 women and 1455 men) 57 to 85 years of age, and we describe the association of these variables with age and health status.

RESULTS

The unweighted survey response rate for this probability sample was 74.8%, and the weighted response rate was 75.5%. The prevalence of sexual activity declined with age (73% among respondents who were 57 to 64 years of age, 53% among respondents who were 65 to 74 years of age, and 26% among respondents who were 75 to 85 years of age); women were significantly less likely than men at all ages to report sexual activity. Among respondents who were sexually active, about half of both men and women reported at least one bothersome sexual problem. The most prevalent sexual problems among women were low desire (43%), difficulty with vaginal lubrication (39%), and inability to climax (34%). Among men, the most prevalent sexual problems were erectile difficulties (37%). Fourteen percent of all men reported using medication or supplements to improve sexual function. Men and women who rated their health as being poor were less likely to be sexually active and, among respondents who were sexually active, were more likely to report sexual problems. A total of 38% of men and 22% of women reported having discussed sex with a physician since the age of 50 years.

CONCLUSIONS

Many older adults are sexually active. Women are less likely than men to have a spousal or other intimate relationship and to be sexually active. Sexual problems are frequent among older adults, but these problems are infrequently discussed with physicians.

Little is known about sexuality among older persons in the United States, despite the aging of the population. Sexuality encompasses partnership, activity, behavior, attitudes, and function.1 Sexual activity is associated with health,2–4 and illness may considerably interfere with sexual health.5 A massive and growing market for drugs and devices to treat sexual problems targets older adults. Driven in part by the availability of drugs to treat erectile dysfunction, the demand for medical attention and services relating to sexual health is increasing. Yet there is limited information on sexual behavior among older adults and how sexual activities change with aging and illness.

Limited data have indicated that some women and men maintain sexual and intimate relationships and desire throughout their lives,2,4,6–8 but these data derive primarily from studies that are small, do not include very old persons, and rely on convenience samples. Physiologic changes can affect the sexual response of men and women and may inhibit or enhance sexual function as people age.9,10 Many people, particularly women, lose their sexual partner as they age. Age and poor health are negatively associated with many aspects of sexuality.3,5,11,12 Sexual problems may be a warning sign or consequence of a serious underlying illness such as diabetes, an infection, urogenital tract conditions, or cancer.10,13 Undiagnosed or untreated sexual problems, or both, can lead to or occur with depression or social withdrawal.14–16 Patients may discontinue needed medications because of side effects that affect their sex lives,17 and medications to treat sexual problems can also have negative health effects, yet physician–patient communication about sexuality is poor.18,19 No comprehensive, nationally representative, population−based data are available to inform physicians’ understanding of the sexual norms and problems of older adults. We designed the National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project (NSHAP) to provide data on the sexual activity, behaviors, and problems of older adults.

METHODS

STUDY POPULATION

We selected a nationally representative probability sample of community−dwelling persons 57 to 85 years of age from households across the United States; this population was screened in 2004. Blacks, Hispanics, men, and the oldest persons (75 to 84 years of age at the time of screening) were oversampled. Of 4017 eligible persons, 3005 (1550 women and 1455 men) were successfully interviewed, yielding an unweighted response rate of 74.8% and a weighted response rate of 75.5%.20 In−home interviews were conducted in English and Spanish by professional interviewers between July 2005 and March 2006. During these visits, anthropometric measurements were performed; blood, salivary, and vaginal mucosal specimens were obtained, and physical function and sensory function were assessed. The protocol was approved by the institutional review boards of the University of Chicago and NORC (National Opinion Research Center); all respondents provided written informed consent.

MEASURES

A complete marital and cohabiting history was obtained, with information on the timing of up to three most recent sexual partnerships within the previous 5 years. Sex or sexual activity was defined as “any mutually voluntary activity with another person that involves sexual contact, whether or not intercourse or orgasm occurs.” Respondents who were married or cohabiting at the time of the survey or who reported having a “romantic, intimate, or sexual partner” were referred to as having a “spousal or other intimate relationship.” Those who had had sex with at least one partner in the previous 12 months were considered to be “sexually active.” (This variable could not be calculated for 107 persons because of missing data.)

Detailed information was collected about one, or if more than one, two of the respondents’ most recent sexual partnerships (within the previous 12 months), including the frequency of sex and participation in activities such as vaginal intercourse and oral sex; for this analysis, performing and receiving oral sex were combined into a single indicator measuring any oral sex in the previous 12 months. Data with regard to the most recent sexual partnership are reported here. All respondents who had not had sex in the previous 3 months were asked to indicate why from a list of possible reasons. One third of the subjects received these questions in a leave−behind questionnaire that was completed by the respondent after the interview and returned by mail; 84% (86%, weighted) returned the questionnaire. A self−administered questionnaire completed during the in−home interview asked about the frequency of masturbation, which was defined as “stimulating your genitals (sex organs) for sexual pleasure, not with a sex partner.” Overall, 2 to 7% of respondents declined to answer questions about sexual activities and problems; 14% declined to answer the question regarding masturbation.

Sexually active respondents were asked about the presence of several sexual problems involving interest, arousal, orgasm, pain, and satisfaction; these problems were selected on the basis of diagnostic21 and clinical22,23 criteria for sexual dysfunction. Respondents were asked about the presence of a problem for “several months or more” during the previous 12 months; this wording reflects chronic rather than episodic problems and permits direct comparisons with previous population−based surveys of adult sexuality.3,11 Respondents rated the degree to which each reported symptom bothered them (“a lot,” “somewhat,” or “not at all”); we defined “bothersome” as either “somewhat” or “a lot.”

Respondents were asked to rate their physical health using the standard 5−point scale with the responses “excellent,” “very good,” “good,” “fair,” or “poor.” They also were asked whether a medical doctor had ever told them they had any of several common medical conditions, including hypertension (high blood pressure), diabetes (high blood sugar), and any type of arthritis. Communication with a physician about sex was ascertained in the leave−behind questionnaire with the following question: “Since you turned 50, have you ever discussed sex with a doctor?”

The purpose of the study was to obtain estimates of the prevalence of sexual activity, behaviors, and problems in the older population. We hypothesized that the profiles of activity and problems would differ between men and women and that differences across age groups would not be uniform for all outcomes. A second objective was to describe the relationship between sexuality and a variety of health conditions.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

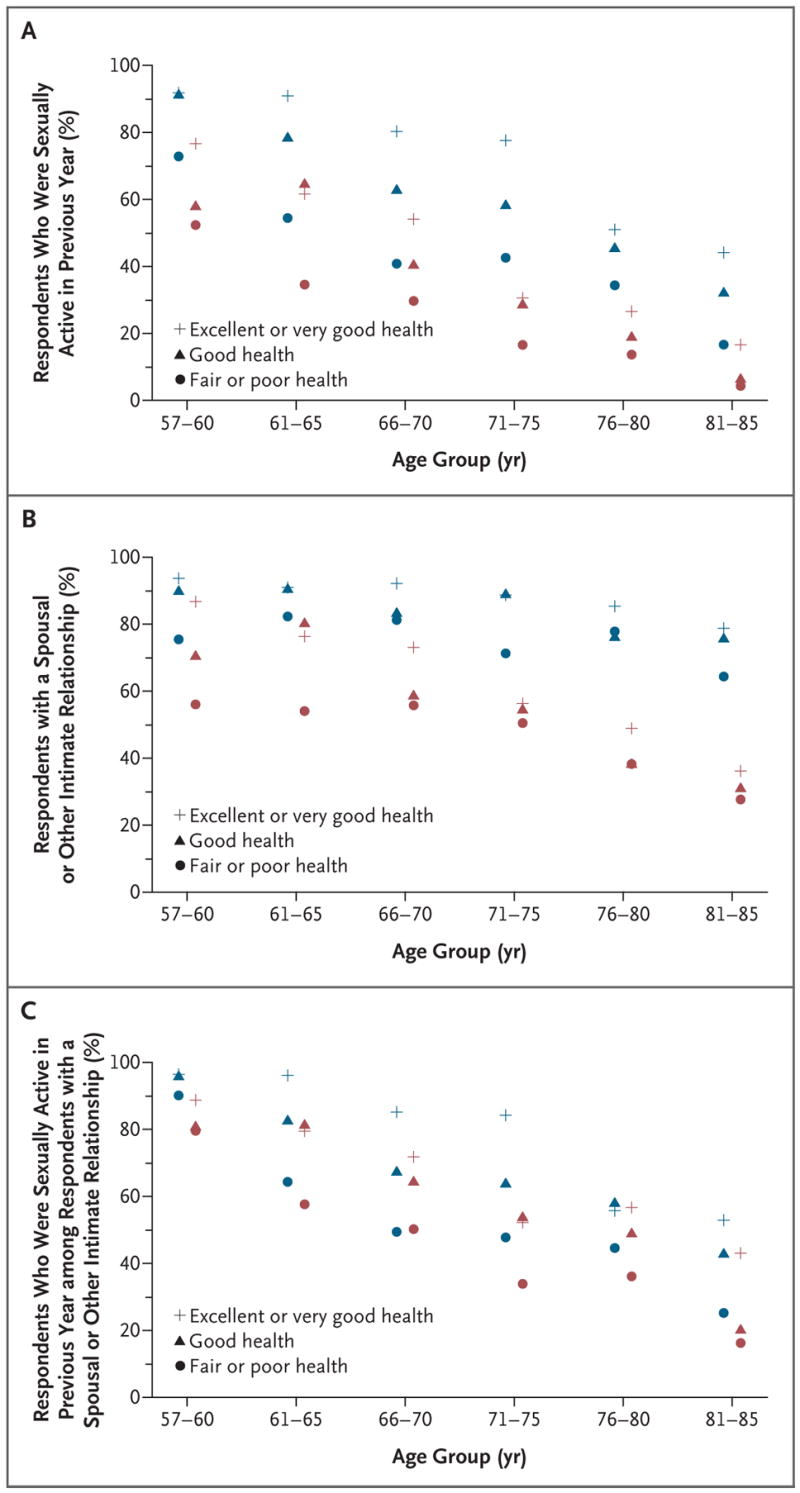

Approximate 95% confidence intervals for percentage estimates were obtained by inverting the corresponding Wald test.24 Logistic regression25 was used to model the likelihood of being sexually active, of engaging in a variety of sexual behaviors, and of experiencing specific sexual problems. These models included age group (57 to 64 years, 65 to 74 years, and 75 to 85 years) and self−rated health (excellent or very good, good, and fair or poor) as covariates and were estimated separately for men and women. Results are presented as odds ratios with 95% confidence intervals. Indicator variables for arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension were then added to these models. In addition, the percentage of respondents who were sexually active, the percentage with a current spouse or intimate relationship, and the percentage with a current spouse or intimate relationship who were sexually active were plotted separately by age categories (57 to 60, 61 to 65, 66 to 70, 71 to 75, 76 to 80, and 81 to 85 years), male or female sex, and self−rated health.

We used weights to adjust for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse for all analyses. We computed standard errors with the use of the linearization method,26 taking into account the stratification and clustering of the sample design. Reported confidence intervals do not include any adjustment for multiple testing. All analyses were performed by means of Stata statistical software, version 9.2.27

RESULTS

Table 1 summarizes the demographic and health characteristics of the survey respondents. These characteristics closely match those of respondents in the 2002 Current Population Survey28 and recent national studies of health (e.g., the Health and Retirement Study29).

Table 1.

Characteristics of 3005 Survey Respondents.*

| Characteristic | 57–64 Yr | 65–74 Yr | 75–85 Yr | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men (N=528) | Women (N=492) | Men (N=547) | Women (N=545) | Men (N=380) | Women (N=513) | |

| percent (95 percent confidence interval) | ||||||

| Race or ethnic group† | ||||||

| White | 78.4 (72.6–84.2) | 78.0 (72.7–83.2) | 80.6 (76.2–85.0) | 78.9 (73.6–84.2) | 86.0 (81.3–90.7) | 86.5 (82.3–90.6) |

| Black | 9.8 (5.1–14.4) | 11.0 (7.6–14.4) | 10.3 (7.3–13.3) | 12.2 (8.4–16.0) | 6.1 (4.1–8.0) | 8.8 (5.6–12.1) |

| Hispanic | 8.0 (4.2–11.9) | 8.4 (3.8–13.0) | 6.5 (3.1–10.0) | 7.1 (3.3–11.0) | 5.7 (1.3–10.1) | 3.5 (1.3–5.8) |

| Other | 3.8 (1.8–5.8) | 2.6 (0.5–4.7) | 2.5 (1.3–3.8) | 1.8 (0.5–3.0) | 2.2 (0.6–3.8) | 1.2 (0.3–2.1) |

| Educational status | ||||||

| <High-school graduate | 11.9 (7.1–16.7) | 14.6 (9.9–19.3) | 18.6 (14.3–22.9) | 19.6 (15.0–24.2) | 24.1 (19.7–28.4) | 29.2 (24.0–34.4) |

| High-school graduate | 22.2 (16.4–28.0) | 27.0 (22.3–31.8) | 25.1 (20.9–29.2) | 28.8 (24.6–33.0) | 27.2 (21.7–32.7) | 34.0 (29.2–38.9) |

| Some college or associate’s degree | 29.2 (23.5–34.9) | 34.2 (27.8–40.5) | 28.0 (23.2–32.8) | 36.3 (31.4–41.1) | 22.8 (19.1–26.6) | 24.8 (20.7–29.0) |

| ≥College graduate | 36.7 (29.9–43.6) | 24.2 (18.7–29.7) | 28.3 (23.7–32.9) | 15.3 (12.3–18.4) | 26.0 (21.6–30.4) | 11.9 (7.8–16.1) |

| Marital status | ||||||

| Married | 82.3 (77.8–86.7) | 66.7 (62.2–71.3) | 76.6 (72.5–80.7) | 56.4 (51.6–61.3) | 71.2 (65.2–77.3) | 37.2 (32.4–42.0) |

| Living with a partner | 1.9 (0.6–3.2) | 3.7 (1.4–6.1) | 2.6 (1.1–4.1) | 1.7 (0.2–3.2) | 0.8 (0.0–1.6) | 1.2 (0.0–2.6) |

| Separated or divorced | 10.5 (7.5–13.4) | 15.1 (12.2–18.0) | 8.7 (6.1–11.2) | 15.7 (12.4–19.0) | 6.0 (3.1–8.9) | 8.7 (5.6–11.9) |

| Widowed | 2.8 (1.0–4.5) | 10.1 (6.8–13.5) | 8.5 (6.5–10.6) | 23.4 (19.1–27.7) | 18.3 (13.6–23.0) | 49.8 (44.6–55.0) |

| Never married | 2.6 (1.0–4.2) | 4.3 (2.2–6.4) | 3.5 (1.5–5.6) | 2.8 (1.4–4.2) | 3.7 (1.7–5.7) | 3.0 (1.3–4.7) |

| Self-rated health status | ||||||

| Poor or fair | 23.1 (17.3–28.9) | 21.9 (17.2–26.6) | 24.5 (20.4–28.6) | 20.1 (15.0–25.1) | 32.0 (26.3–37.6) | 33.2 (28.0–38.4) |

| Good | 22.8 (17.7–27.9) | 31.3 (27.1–35.6) | 30.5 (26.3–34.7) | 32.8 (28.3–37.3) | 32.2 (26.6–37.8) | 30.2 (25.9–34.4) |

| Very good or excellent | 54.1 (48.4–59.8) | 46.7 (41.7–51.8) | 45.0 (39.4–50.6) | 47.2 (41.7–52.6) | 35.8 (29.8–41.9) | 36.6 (32.0–41.3) |

| Conditions | ||||||

| Arthritis | 37.3 (33.5–41.2) | 53.5 (49.2–57.8) | 44.6 (39.9–49.3) | 58.2 (54.0–62.3) | 55.0 (48.3–61.8) | 68.6 (64.2–73.1) |

| Diabetes | 20.4 (16.5–24.3) | 17.8 (13.3–22.3) | 22.8 (18.7–27.0) | 20.3 (16.6–24.0) | 21.6 (17.2–26.1) | 15.7 (12.3–19.2) |

| Hypertension | 45.2 (38.6–51.7) | 47.9 (43.0–52.8) | 61.9 (57.7–66.1) | 53.8 (48.1–59.4) | 56.4 (50.4–62.4) | 64.5 (59.1–69.9) |

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse. The confidence interval is based on the inversion of Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors.

Race or ethnic group was determined on the basis of the questions “Do you consider yourself primarily white or Caucasian, black or African American, American Indian, Asian, or something else?” and “Do you consider yourself Hispanic or Latino?” Six respondents who reported being both Hispanic and black or African American were included in the black group.

The likelihood of being sexually active declined steadily with age and was uniformly lower among women than among men (Table 2). In addition, the likelihood of being sexually active was positively associated with self−reported health (Fig. 1A). The odds ratio for being sexually active among those who reported their health to be “poor” or “fair” as compared with those reporting “very good” or “excellent” health was 0.21 (95% confidence interval [CI], 0.14 to 0.32) for men and 0.36 (95% CI, 0.25 to 0.51) for women.

Table 2.

Prevalence of Sexual Activity, Behaviors, and Problems.

| Variable | Respondents | Age Group | Self-Rated Health Status | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57–64 yr | 65–74 yr | 75–85 yr | 65–75 yr vs.57–64 yr | 75–85 yr vs.57–64 yr | Excellent or Very Good | Good | Fair or Poor | Good vs.Excellent or Very Good | Poor or Fair vs. Excellent or Very Good | ||

| no. | % (95% CI)† | adjusted odds ratio‡ | % (95% CI)* | adjusted odds ratio† | |||||||

| Sexual activity with a partner | |||||||||||

| In previous 12 mo‡ | |||||||||||

| Men | 1385 | 83.7 (77.6–89.8) | 67.0 (62.1–72.0) | 38.5 (33.6–43.5) | 0.39 (0.25–0.60) | 0.12 (0.08–0.20) | 81.3 (77.3–85.2) | 66.3 (60.8–71.7) | 47.1 (38.3–55.8) | 0.53 (0.39–0.71) | 0.21 (0.14–0.32) |

| Women | 1501 | 61.6 (56.7–66.4) | 39.5 (34.6–44.4) | 16.7 (12.5–21.0) | 0.39 (0.30–0.52) | 0.13 (0.09–0.19) | 51.2 (45.9–56.4) | 42.6 (37.4–47.7) | 26.2 (20.9–31.4) | 0.70 (0.51–0.97) | 0.36 (0.25–0.51) |

| ≥2–3 times per mo§ | |||||||||||

| Men | 857 | 67.5 (60.8–74.2) | 65.4 (59.0–71.9) | 54.2 (44.2–64.2) | 0.92 (0.57–1.49) | 0.61 (0.35–1.06) | 72.5 (66.8–78.1) | 61.6 (55.2–68.0) | 46.4 (36.7–56.1) | 0.63 (0.41–0.95) | 0.34 (0.19–0.59) |

| Women | 492 | 62.6 (55.3–69.9) | 65.4 (56.5–74.3) | 54.1 (41.6–66.6) | 1.11 (0.65–1.90) | 0.69 (0.43–1.11) | 65.9 (59.1–72.7) | 61.0 (48.6–73.4) | 55.5 (42.3–68.6) | 0.80 (0.44–1.46) | 0.65 (0.34–1.24) |

| Sexual behavior | |||||||||||

| Vaginal intercourse (usually or always)§ | |||||||||||

| Men | 854 | 91.1 (88.2–94.0) | 78.5 (73.0–84.0) | 83.5 (76.6–90.4) | 0.36 (0.24–0.54) | 0.52 (0.28–0.95) | 88.6 (85.2–91.9) | 79.5 (72.2–86.8) | 87.4 (81.9–92.9) | 0.51 (0.30–0.89) | 0.91 (0.50–1.66) |

| Women | 501 | 86.8 (82.2–91.4) | 85.4 (79.3–91.4) | 74.4 (60.5–88.4) | 0.88 (0.46–1.66) | 0.45 (0.18–1.11) | 87.2 (83.1–91.4) | 85.0 (78.7–91.2) | 77.3 (67.6–87.0) | 0.80 (0.44–1.45) | 0.51 (0.25–1.01) |

| Oral sex in previous 12 mo§ | |||||||||||

| Men | 831 | 62.1 (55.6–68.6) | 47.9 (42.7–53.2) | 28.3 (17.7–38.9) | 0.56 (0.42–0.76) | 0.25 (0.13–0.47) | 56.4 (50.7–62.0) | 50.6 (44.3–56.9) | 46.9 (35.2–58.5) | 0.84 (0.58–1.22) | 0.72 (0.44–1.16) |

| Women | 484 | 52.7 (45.0–60.3) | 46.5 (37.7–55.3) | 35.0 (22.5–47.5) | 0.78 (0.48–1.26) | 0.48 (0.24–0.98) | 57.0 (50.3–63.7) | 42.0 (31.3–52.8) | 34.0 (23.9–44.1) | 0.53 (0.31–0.93) | 0.39 (0.22–0.69) |

| Masturbation in previous 12 mo¶ | |||||||||||

| Men | 1250 | 63.4 (57.0–69.9) | 53.0 (47.9–58.1) | 27.9 (23.3–32.4) | 0.65 (0.49–0.85) | 0.22 (0.16–0.31) | 54.1 (47.9–60.3) | 54.9 (47.7–62.2) | 45.4 (38.2–52.6) | 1.21 (0.81–1.82) | 0.82 (0.57–1.17) |

| Women | 1281 | 31.6 (26.4–36.8) | 21.9 (17.6–26.2) | 16.4 (11.7–21.1) | 0.59 (0.42–0.83) | 0.46 (0.29–0.72) | 31.6 (27.2–36.0) | 21.9 (17.2–26.6) | 14.3 (10.0–18.6) | 0.61 (0.45–0.84) | 0.38 (0.25–0.56) |

| Sexual problems|| | |||||||||||

| Lack of interest in sex | |||||||||||

| Men | 881 | 28.2 (21.2–35.3) | 28.5 (22.8–34.3) | 24.2 (16.5–32.0) | 1.00 (0.59–1.71) | 0.74 (0.42–1.33) | 22.8 (19.0–26.5) | 32.9 (22.6–43.2) | 36.6 (26.4–46.7) | 1.69 (1.01–2.83) | 1.98 (1.22–3.22) |

| Women | 504 | 44.2 (36.8–51.6) | 38.4 (29.5–47.4) | 49.3 (36.8–61.9) | 0.81 (0.53–1.22) | 1.22 (0.72–2.06) | 38.1 (31.6–44.6) | 43.9 (31.9–55.9) | 57.1 (46.4–67.8) | 1.28 (0.79–2.08) | 2.12 (1.29–3.49) |

| Difficulty achieving or maintaining erection | |||||||||||

| Men | 874 | 30.7 (25.3–36.0) | 44.6 (38.7–50.5) | 43.5 (34.5–52.4) | 1.83 (1.33–2.52) | 1.62 (1.05–2.51) | 31.1 (24.8–37.3) | 40.4 (32.8–48.1) | 50.2 (39.4–60.9) | 1.46 (0.94–2.27) | 2.24 (1.29–3.87) |

| Difficulty with lubrication | |||||||||||

| Women | 495 | 35.9 (29.6–42.2) | 43.2 (34.8–51.5) | 43.6 (27.0–60.2) | 1.41 (0.86–2.31) | 1.34 (0.64–2.80) | 38.3 (31.5–45.1) | 32.9 (25.1–40.7) | 52.4 (40.7–64.0) | 0.79 (0.48–1.31) | 1.79 (1.00–3.20) |

| Climaxing too quickly | |||||||||||

| Men | 860 | 29.5 (23.4–35.7) | 28.1 (23.4–32.9) | 21.3 (13.2–29.3) | 0.94 (0.63–1.39) | 0.64 (0.39–1.05) | 28.3 (22.0–34.7) | 26.9 (19.8–34.0) | 29.0 (18.5–39.6) | 0.95 (0.56–1.61) | 1.06 (0.56–1.98) |

| Inability to climax | |||||||||||

| Men | 866 | 16.2 (11.9–20.5) | 22.7 (17.5–27.9) | 33.2 (25.0–41.5) | 1.52 (0.95–2.44) | 2.46 (1.49–4.07) | 17.1 (13.5–20.8) | 21.8 (15.3–28.2) | 28.9 (20.8–37.0) | 1.28 (0.84–1.94) | 1.91 (1.23–2.98) |

| Women | 479 | 34.0 (28.0–40.1) | 32.8 (24.9–40.6) | 38.2 (23.7–52.8) | 0.97 (0.58–1.61) | 1.21 (0.57–2.57) | 30.8 (26.1–35.6) | 35.3 (26.1–44.6) | 42.3 (30.4–54.1) | 1.24 (0.80–1.93) | 1.63 (0.93–2.86) |

| Pain during intercourse | |||||||||||

| Men | 878 | 3.0 (1.1–4.8) | 3.2 (1.2–5.3) | 1.0 (0.0–2.5) | 1.09 (0.41–2.90) | 0.31 (0.07–1.34) | 2.0 (0.9–3.2) | 3.1 (0.4–5.9) | 5.0 (1.3–8.7) | 1.62 (0.57–4.62) | 2.65 (1.01–7.00) |

| Women | 506 | 17.8 (13.3–22.2) | 18.6 (10.8–26.3) | 11.8 (4.3–19.4) | 1.07 (0.60–1.92) | 0.59 (0.26–1.32) | 16.0 (10.9–21.1) | 14.9 (8.3–21.5) | 27.8 (17.5–38.1) | 0.90 (0.47–1.75) | 2.06 (1.07–3.95) |

| Sex not pleasurable | |||||||||||

| Men | 878 | 3.8 (2.4–5.2) | 7.0 (3.7–10.4) | 5.1 (1.2–9.0) | 1.94 (1.02–3.71) | 1.32 (0.55–3.17) | 4.0 (2.3–5.8) | 4.5 (2.1–6.9) | 9.2 (4.4–14.0) | 1.09 (0.54–2.19) | 2.42 (1.16–5.04) |

| Women | 498 | 24.0 (18.0–30.1) | 22.0 (15.0–29.0) | 24.9 (14.8–35.0) | 0.93 (0.56–1.54) | 1.09 (0.59–2.01) | 18.6 (13.1–24.1) | 24.5 (15.1–33.8) | 37.7 (27.0–48.3) | 1.42 (0.74–2.70) | 2.64 (1.52–4.59) |

| Anxiety about performance | |||||||||||

| Men | 873 | 25.1 (20.9–29.2) | 28.9 (22.9–34.9) | 29.3 (19.8–38.9) | 1.20 (0.84–1.72) | 1.16 (0.72–1.86) | 22.7 (18.7–26.7) | 32.8 (25.0–40.6) | 31.0 (21.8–40.3) | 1.65 (1.10–2.46) | 1.53 (0.90–2.62) |

| Women | 500 | 10.4 (6.3–14.5) | 12.5 (6.1–18.9) | 9.9 (1.7–18.2) | 1.25 (0.55–2.88) | 1.00 (0.35–2.87) | 7.5 (4.1–10.9) | 14.4 (7.9–20.9) | 17.4 (9.7–25.0) | 2.07 (0.97–4.42) | 2.62 (1.23–5.55) |

| Avoidance of sex because of sexual problems** | |||||||||||

| Men | 553 | 22.1 (17.3–26.9) | 30.1 (23.2–37.0) | 25.7 (14.9–36.4) | 1.54 (1.04–2.27) | 1.11 (0.56–2.22) | 19.6 (15.8–23.4) | 23.3 (15.0–31.7) | 44.2 (34.4–54.0) | 1.27 (0.77–2.08) | 3.30 (2.00–5.42) |

| Women | 357 | 34.3 (25.0–43.7) | 30.5 (21.5–39.4) | 22.7 (9.4–35.9) | 0.87 (0.49–1.55) | 0.55 (0.22–1.37) | 29.5 (22.2–36.8) | 28.0 (17.1–38.8) | 42.2 (29.6–54.9) | 0.92 (0.50–1.69) | 1.78 (0.97–3.28) |

Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse. The confidence interval (CI) is based on the inversion of Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors.

Adjusted odds ratios are based on a logistic regression including the age group and self-rated health status as covariates, estimated separately for men and women. The confidence interval is based on the inversion of Wald tests constructed with the use of design-based standard errors.

These data exclude 107 respondents for whom data on the timing of the last sexual encounter were missing.

Respondents were asked about this activity or behavior if they reported having sex in the previous 12 months.

This question was asked of all respondents by means of a self-administered questionnaire. A total of 162 declined to answer, 244 left the item blank, and 31 answered “don’t know”; 27 questionnaires were lost in the field; and 1 respondent discontinued the interview before the questionnaire was provided.

Prevalence was based on the number of respondents who reported having sex in the previous 12 months.

This question was asked only of respondents who reported at least one sexual problem.

Figure 1. Prevalence of Sexual Activity with a Partner, According to Age Group and Health Status.

Panel A shows the percentage of survey respondents who were sexually active in the previous year. Panel B shows the percentage of survey respondents who were in a spousal or other intimate relationship. Panel C shows the percentage of respondents who were sexually active in the previous year among those with a spousal or other intimate relationship. Blue symbols denote men, red symbols women, plus signs respondents who reported being in excellent or very good health, triangles respondents who reported being in good health, and circles respondents who reported being in fair or poor health.

At any given age, women were less likely than men to be in a marital or other intimate relationship, and this difference increased dramatically with age (Fig. 1B). Of the 1198 men and 815 women in a relationship, only 3 men and 5 women reported that the relationship was with someone of the same sex. Figure 1C shows the percentage of respondents with a spousal or other intimate relationship who reported being sexually active; among those who were not in a relationship, only 22% of men and 4% of women reported being sexually active in the previous year. Among men and women of the same age, men with a spousal or other intimate relationship were more likely to be sexually active than women with such a relationship. However, the difference in the rates of sexual activity between men and women was considerably smaller among those with a spousal or intimate relationship; this difference reflects, in part, the disparity in ages between men and women within current relationships. Among all current marital and intimate relationships in the sample, the mean (±SD) difference in age between male and female partners was 3.2±5.7 years.

Among respondents who were sexually active, the frequency of sex was lower among those who were 75 to 85 years of age than among younger persons (Table 2). However, even in this oldest−age group, 54% of sexually active persons reported having sex at least two to three times per month, and 23% reported having sex once a week or more. Fifty−eight percent of sexually active respondents in the youngest−age group reported engaging in oral sex, as compared with 31% in the oldest age group.

The prevalence of masturbation, like that of sexual activity with a partner, was lower among respondents at older ages and was higher among men than among women. Poorer health was also associated with a lower likelihood of masturbation among women (Table 2). Fifty−two percent of men and 25% of women with a spousal or other intimate relationship reported masturbating in the previous 12 months, as compared with 55% of men and 23% of women without a current spousal or other intimate relationship.

Women were more likely to rate sex as being “not at all important” (35%, as compared with 13% of men). A total of 41% of respondents in the oldest−age group rated sex as being “not at all important,” as compared with 25% of respondents in the middle group and 15% of respondents in the youngest group. Respondents who were not sexually active were also more likely to give this answer (48%, as compared with 5% of respondents who were sexually active).

Table 2 lists the prevalence of sexual problems among respondents who were sexually active and the associations of these problems with the respondents’ age and self−reported health status. Approximately half of all respondents (both men and women) reported having at least one bothersome sexual problem, and almost one third of men and women reported having at least two bothersome sexual problems. Among men, the most prevalent sexual problems and the corresponding percentages of those who were bothered by them were difficulty in achieving or maintaining an erection (37% and 90%, respectively), lack of interest in sex (28% and 65%), climaxing too quickly (28% and 71%), anxiety about performance (27% and 75%), and inability to climax (20% and 73%). For women, the most common sexual problems and the percentages of those who were bothered by them were lack of interest in sex (43% and 61%, respectively), difficulty with lubrication (39% and 68%), inability to climax (34% and 59%), finding sex not pleasurable (23% and 64%), and pain (most commonly felt at the vagina during entry) (17% and 97%). As compared with respondents who rated their health as being excellent, very good, or good, respondents who rated their health as being fair or poor had a higher prevalence of several problems, including difficulty with erection or lubrication, pain, and lack of pleasure. Women with diabetes were less likely to be sexually active than women without diabetes (Table 3). Diabetes was also associated with a higher likelihood of difficulty with erection among men and a lower likelihood of masturbation among both men and women.

Table 3.

Sexual Activity, Behaviors, and Problems Associated with Chronic Health Conditions in Men and Women.*

| Variable | Arthritis | Diabetes | Hypertension | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | Men | Women | Men | Women | |

| odds ratio (95% CI) | ||||||

| Sexual activity | ||||||

| In previous 12 mo† | 0.89 (0.69–1.15) | 1.04 (0.78–1.37) | 0.85 (0.58–1.25) | 0.61 (0.46–0.81) | 1.00 (0.71–1.41) | 0.93 (0.73–1.18) |

| ≥2–3 times per mo‡ | 0.92 (0.66–1.28) | 0.86 (0.52–1.41) | 0.80 (0.52–1.25) | 1.16 (0.52–2.61) | 1.34 (0.94–1.91) | 1.32 (0.84–2.05) |

| Behavior | ||||||

| Vaginal intercourse usually or always‡ | 0.72 (0.44–1.16) | 1.79 (0.96–3.35) | 0.71 (0.44–1.13) | 0.86 (0.37–2.00) | 0.65 (0.41–1.04) | 0.76 (0.44–1.33) |

| Oral sex in previous 12 mo‡ | 0.96 (0.67–1.38) | 1.01 (0.65–1.57) | 0.78 (0.54–1.12) | 0.76 (0.36–1.61) | 0.68 (0.49–0.95) | 1.01 (0.64–1.60) |

| Masturbation in previous 12 mo§ | 0.89 (0.67–1.19) | 1.07 (0.80–1.44) | 0.74 (0.53–1.02) | 0.55 (0.38–0.81) | 1.22 (0.90–1.63) | 0.99 (0.71–1.37) |

| Sexual problem¶ | ||||||

| Lack of interest in sex | 1.17 (0.83–1.66) | 0.84 (0.57–1.24) | 1.65 (1.12–2.43) | 1.06 (0.54–2.08) | 0.86 (0.60–1.24) | 0.98 (0.64–1.49) |

| Difficulty achieving or maintaining erection | 1.00 (0.71–1.40) | 2.62 (1.43–4.81) | 0.86 (0.55–1.34) | |||

| Difficulty with lubrication | 0.90 (0.60–1.35) | 0.94 (0.50–1.76) | 0.97 (0.56–1.66) | |||

| Climaxing too quickly | 1.03 (0.69–1.55) | 1.62 (0.87–3.03) | 0.95 (0.57–1.56) | |||

| Inability to climax | 1.06 (0.75–1.49) | 0.87 (0.52–1.46) | 1.38 (0.83–2.28) | 1.82 (0.89–3.74) | 1.14 (0.76–1.69) | 0.76 (0.50–1.14) |

| Pain during intercourse | 0.40 (0.16–1.00) | 1.56 (0.90–2.68) | 1.80 (0.65–4.98) | 0.83 (0.44–1.59) | 0.95 (0.44–2.06) | 0.61 (0.31–1.20) |

| Sex not pleasurable | 1.14 (0.62–2.11) | 0.76 (0.44–1.30) | 1.06 (0.48–2.32) | 0.91 (0.42–1.96) | 2.67 (1.37–5.19) | 0.80 (0.50–1.28) |

| Anxiety about performance | 0.78 (0.53–1.14) | 1.26 (0.60–2.63) | 1.20 (0.77–1.85) | 0.86 (0.37–2.01) | 1.19 (0.82–1.72) | 1.15 (0.65–2.02) |

| Avoidance of sex because of sexual problems|| | 0.90 (0.65–1.26) | 1.44 (0.77–2.70) | 1.07 (0.60–1.92) | 0.92 (0.47–1.82) | 0.74 (0.46–1.18) | 0.60 (0.31–1.14) |

The likelihood of being sexually active, of engaging in a variety of sexual behaviors, and of experiencing specific sexual problems was based on a logistic regression including age group, self-rated health status, arthritis, diabetes, and hypertension as covariates, estimated separately for men and women. The confidence interval (CI) is based on the inversion of Wald tests constructed using design-based standard errors.

These data exclude 107 respondents for whom data with regard to the timing of the last sexual encounter were missing.

Questions about these activities or behaviors were asked of respondents who reported having sex in the previous 12 months; the question referred to the preceding 12-month period.

This question was asked of all respondents by means of a self-administered questionnaire. A total of 162 declined to answer, 244 left the item blank, and 31 answered “don’t know”; 27 questionnaires were lost in the field; and 1 respondent discontinued the interview before the questionnaire was provided.

Respondents were asked about sexual problems if they reported having sex in the previous 12 months.

This question was asked only of those respondents who reported at least one sexual problem.

Among all respondents with a spousal or other intimate relationship who had been sexually inactive for 3 months or longer, the most commonly reported reason for sexual inactivity was the male partner’s physical health (Table 4). A total of 55% of men and 64% of women reported this reason for a lack of sexual activity. Overall, women were more likely than men to report lack of interest as a reason for sexual inactivity; this was especially true among respondents without a current relationship (51% of women vs. 24% of men).

Table 4.

Reasons for Lack of Sexual Activity among Survey Respondents Who Had Not Had Sex during the Previous 3 Months.*

| Reason | Respondents with Spousal or Intimate Relationship | Respondents without Spousal or Intimate Relationship | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 57–64 yr | 65–74 yr | 75–85 yr | 57–64 yr | 65–74 yr | 75–85 yr | |

| Lack of interest in sex — no. (%) | ||||||

| Men | 60 (13.5) | 139 (11.7) | 132 (19.1) | 39 (18.3) | 69 (22.0) | 78 (32.1) |

| Women | 81 (23.8) | 105 (25.0) | 95 (24.9) | 133 (43.0) | 214 (47.0) | 295 (60.3) |

| Partner not interested in sex — % | ||||||

| Men | 29.5 | 10.3 | 16.8 | |||

| Women | 19.2 | 19.8 | 15.8 | |||

| Physical health problems or limitations — % | ||||||

| Men | 40.3 | 56.6 | 61.4 | 27.4 | 15.7 | 28.3 |

| Women | 16.8 | 16.7 | 24.8 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 4.7 |

| Partner’s physical health problems or limitations — % | ||||||

| Men | 20.1 | 31.3 | 22.7 | |||

| Women | 63.2 | 63.4 | 64.8 | |||

| Grief — % | ||||||

| Men | 2.5 | 0.0 | 0.5 | 5.9 | 12.3 | 13.5 |

| Women | 1.2 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 5.4 | 8.6 | 10.3 |

| Have not met the right person — no. (%)† | ||||||

| Men | 32 (23.8) | 48 (52.1) | 59 (24.6) | |||

| Women | 99 (47.0) | 157 (35.9) | 199 (28.8) | |||

| Have not met a willing partner — no. (%)† | ||||||

| Men | 32 (15.3) | 48 (14.4) | 59 (6.3) | |||

| Women | 99 (12.0) | 157 (10.4) | 199 (3.4) | |||

| Lack of opportunity — % | ||||||

| Men | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.1 | 28.1 | 16.7 | 17.3 |

| Women | 5.3 | 0.7 | 1.0 | 15.5 | 20.3 | 7.7 |

| Religious beliefs prohibit sex outside marriage — % | ||||||

| Men | 8.5 | 2.7 | 9.3 | 12.3 | 10.1 | 12.1 |

| Women | 4.9 | 4.6 | 5.8 | 20.3 | 22.6 | 14.6 |

| Concern about becoming infected with a sexually transmitted disease — % | ||||||

| Men | 2.6 | 0.7 | 0.0 | 15.9 | 12.0 | 8.1 |

| Women | 2.6 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 17.4 | 16.7 | 6.1 |

Respondents were asked to check as many reasons as applied. Additional reasons listed included: painful intercourse, respondent’s emotional problems, partner’s emotional problems, family would not approve, friends would not approve, and lack of sufficient privacy. Each of these reasons was selected by fewer than 5% of respondents. The numbers of respondents are those who could have chosen the reason for the lack of sexual activity, and the percentages are the estimated proportion of respondents who chose that reason. Estimates are weighted to account for differential probabilities of selection and differential nonresponse.

These items were omitted from the in-person interview if the respondent reported having a spousal or other intimate relationship; in the leave-behind questionnaire, these items were omitted to avoid confusion on the part of the respondent. The same numbers of respondents could have selected “have not met the right person” and “have not met a willing partner” as reasons for lack of sexual activity; the percentages are the estimated proportions of respondents who chose these reasons.

Fourteen percent of men and 1% of women reported taking prescription or nonprescription medication or supplements to improve sexual function in the previous 12 months. Overall, 38% of men and 22% of women reported having discussed sex with a physician since the age of 50 years.

DISCUSSION

Our findings, based on nationally representative data from the NSHAP, indicate that the majority of older adults are engaged in spousal or other intimate relationships and regard sexuality as an important part of life. The prevalence of sexual activity declines with age, yet a substantial number of men and women engage in vaginal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation even in the eighth and ninth decades of life.

In our study, the frequency of sexual activity reported by respondents who were sexually active was similar to that reported among adults 18 to 59 years of age in the 1992 National Health and Social Life Survey (NHSLS), the only other comprehensive, population−based study of sexuality in the United States.30 The frequency of sexual activity did not decrease substantially with increasing age through 74 years of age, despite a high prevalence of bothersome sexual problems (>50%). Specific sexual problems were not assessed among sexually inactive adults; therefore, this study probably underestimates their overall prevalence. Nearly one in seven men reported taking medication to improve sexual function. About one quarter of sexually active older adults with a sexual problem reported avoiding sex as a consequence. These persons would be likely to benefit from therapeutic interventions.

We found several disparities with regard to the sexuality of men and women at older ages. The impact of age on the availability of a spouse or other intimate partner is particularly marked among women. A total of 78% of men 75 to 85 years of age, as compared with 40% of women in this age group, reported having a spousal or other intimate relationship. This difference may be explained by several factors, including the age structure of marital relationships among older adults (men are, on average, married to younger women), differential remarriage patterns,31 and the earlier rate of death among men as compared with women.32,33

A recent multinational survey34 of persons 40 to 80 years of age (response rate, 19%) also showed that women were more likely than men to rate sex as an unimportant part of life and to report lack of pleasure with sex. Despite a similarly high prevalence of bothersome sexual problems among women and men, we found that women were less likely than men to have discussed sex with a physician. Overall, these low rates of communication are consistent with data from other available reports, including one study of younger women.35 Reasons for poor communication include the unwillingness of patients and physicians to initiate such discussions19,36 and sex and age differences between patients and their physicians.36 Negative societal attitudes about women’s sexuality and sexuality at older ages may also inhibit such discussions.18,19

Previous studies, including the NHSLS,11 the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors,3 and a large study of younger adults (16 to 44 years of age) in the United Kingdom,37 showed that sexual dysfunction is associated with poor health. Our study also showed that sexuality is closely linked to health at older ages, more so for men than for women. Persons in good physical health are more likely to have a spousal or other intimate relationship and are more likely to be sexually active with a partner. Consistent with previous research, our study indicates that diabetes is positively associated with difficulty with erection7,38 as well as with a lower prevalence of sexual activity with a partner and masturbation. As has been previously reported,3,7,11 the prevalence of erectile difficulties is higher at older than at younger ages. In contrast, the prevalence of some sexual problems, such as pain or, among men, climaxing too quickly, is lower among persons in older−age groups. Physical health is more strongly associated with many sexual problems than is age alone; this suggests that older adults who have medical problems or who are considering treatment that might affect sexual functioning should be counseled according to their health status rather than their age.

We only assessed the prevalence of specific sexual problems among sexually active persons; therefore, our findings are likely to underestimate the extent of sexual problems in the older population. Moreover, this bias may increase with age, since persons who are experiencing sexual problems are more likely to discontinue sexual activity. Prospective, longitudinal data are needed to better understand the associations between sexual problems and future sexual activity or relationships. As with most sexuality research, an additional limitation of our study is the fact that the data were self−reported, although the interview methods are well accepted as being valid.39 This report builds on several studies that have informed an understanding of sexuality at older ages in the United States,3,4,7,40 particularly by filling a void of information about older women’s sexuality and using a design that overcomes the limitations inherent in studies of convenience samples or narrow clinical or consumer−based populations and studies with very low participation rates.

Many older adults are sexually active. Sexual problems are frequent among older adults, but these problems are infrequently discussed with physicians. Physician knowledge about sexuality at older ages should improve patient education and counseling, as well as the ability to clinically identify a highly prevalent spectrum of health−related and potentially treatable sexual problems.

Acknowledgments

Supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, including the National Institute on Aging, the Office of Research on Women’s Health, the Office of AIDS Research, and the Office of Behavioral and Social Sciences Research (5R01 AG021487), and by NORC, which was responsible for the data collection. Donors of supplies include OraSure, Sunbeam, A&D Medical/Life−Source, Wilmer Eye Institute at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Schleicher & Schuell Bioscience, Bio−Merieux, Roche Diagnostics, Digene, and Richard Williams.

Dr. Laumann reports receiving research funding and support for a research assistant from Pfizer. Dr. O’Muircheartaigh reports serving as an expert witness on behalf of Johnson & Johnson. Dr. Waite reports serving on the eHarmony Research Laboratories Advisory Board and receiving a yearly honorarium. No other potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

We thank Elyzabeth Gaumer, Hanna Surawska, and Karl Mendoza for research assistance.

References

- 1.Lindau ST, Laumann EO, Levinson W, Waite LJ. Synthesis of scientific disciplines in pursuit of health: the Interactive Bio−psychosocial Model. Perspect Biol Med. 2003;46(Suppl 3):S74–S86. doi: 10.1353/pbm.2003.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Addis IB, Van Den Eeden SK, Wassel−Fyr CL, et al. Sexual activity and function in middle−aged and older women. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;107:755–64. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000202398.27428.e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Laumann EO, Nicolosi A, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual problems among women and men aged 40–80 y: prevalence and correlates identified in the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Int J Impot Res. 2005;17:39–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.AARP/Modern Maturity sexuality survey. Washington, DC: National Family Opinion (NFO) Research; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schover LR. Sexual problems in chronic illness. In: Leiblum SR, Rosen RC, editors. Principles and practice of sex therapy. New York: Guilford; 2000. pp. 398–422. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nicolosi A, Laumann EO, Glasser DB, et al. Sexual behavior and sexual dysfunctions after age 40: the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Urology. 2004;64:991–7. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2004.06.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bacon CG, Mittleman MA, Kawachi I, Giovannucci E, Glassser DB, Rimm EB. Sexual function in men older than 50 years of age: results from the Health Professionals Follow−up Study. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:161–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-3-200308050-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Araujo AB, Mohr BA, McKinlay JB. Changes in sexual function in middle−aged and older men: longitudinal data from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1502–9. doi: 10.1111/j.0002-8614.2004.52413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bachmann GA, Leiblum SR. The impact of hormones on menopausal sexuality: a literature review. Menopause. 2004;11:120–30. doi: 10.1097/01.GME.0000075502.60230.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rosen RC, Wing R, Schneider S, Gen−drano N. Epidemiology of erectile dysfunction: the role of medical comorbidities and lifestyle factors. Urol Clin North Am. 2005;32:403–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA. 1999;281:537–44. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.6.537. [Erratum, JAMA 1999;281:1174.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Camacho ME, Reyes−Ortiz CA. Sexual dysfunction in the elderly: age or disease? Int J Impot Res. 2005;17(Suppl 1):S52–S56. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijir.3901429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Isselbacher KJ, Martin JB, Braunwald E, Fauci AS, Wilson JD, Kasper DL, editors. Harri−son’s principles of internal medicine. 13. New York: McGraw−Hill; 1994. p. 262. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nicolosi A, Moreira ED, Jr, Villa M, Glasser DB. A population study of the association between sexual function, sexual satisfaction and depressive symptoms in men. J Affect Disord. 2004;82:235–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2003.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morley JE, Tariq SH. Sexual dysfunction in older persons. In: Hazzard WR, Blass JP, Halter JB, Ouslander JG, Tinetti ME, editors. Principles of geriatric medicine and gerontology. 5. New York: Mc−Graw−Hill; 2003. pp. 1311–23. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Araujo AB, Durante R, Feldman HA, Goldstein I, McKinlay JB. The relationship between depressive symptoms and male erectile dysfunction: cross−sectional results from the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. Psychosom Med. 1998;60:458–65. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199807000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finger WW, Lund M, Slagle MA. Medications that may contribute to sexual disorders: a guide to assessment and treatment in family practice. J Fam Pract. 1997;44:33–43. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lindau ST, Leitsch SA, Lundberg KL, Jerome J. Older women’s attitudes, behavior, and communication about sex and HIV: a community−based study. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2006;15:747–53. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2006.15.747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093–103. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Muircheartaigh C, Smith S. NSHAP (National Social Life, Health, and Aging Project) Wave 1 methodology report. Chicago: National Opinion Research Center (NORC); 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4 (text revision) Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. DSM−IV−TR. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lue TF, Guiliano F, Montorsi F, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in men. J Sex Med. 2004;1:6–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Basson R, Althof S, Davis S, et al. Summary of the recommendations on sexual dysfunctions in women. J Sex Med. 2004;1:24–34. doi: 10.1111/j.1743-6109.2004.10105.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fleiss JL, Levin B, Paik MC. Statistical methods for rates and proportions. 3. New York: John Wiley; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Agresti A. Categorical data analysis. New York: John Wiley; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Binder DA. On the variances of asymptotically normal estimators from complex surveys. Int Stat Rev. 1983;51:279–92. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Stata statistical software, release 9. College Station, TX: StataCorp; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; May 2003, [Accessed July 27, 2007]. The older population in the United States: March 2002 — detailed tables (PPL−167) http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/age/ppl-167.html. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fisher GD, Faul JD, Weir DR, Wallace RB. Documentation of chronic disease measures in the Health and Retirement Study (HRS/AHEAD): HRS documentation report DR−009. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S. The social organization of sexuality: sexual practices in the United States. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 1994. p. 88. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bramlett MD, Mosher WD. Advance data from vital and health statistics. No. 323. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. First marriage, dissolution, divorce, and remarriage: United States. Report no. (PHS) 2001−1250. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.He W, Sengupta M, Velkoff VA, De−Barros KA. 65+ In the United States. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Minino AM, Heron MP, Smith BL. Deaths: preliminary data for 2004. National vital statistics reports. 19. Vol. 54. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2006. Report no. (PHS) 2006−1120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Laumann EO, Paik A, Glasser DB, et al. A cross−national study of subjective sexual well−being among older women and men: findings from the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes and Behaviors. Arch Sex Behav. 2006;35:145–61. doi: 10.1007/s10508-005-9005-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nusbaum MRH, Gamble GR, Pathman DE. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns: frequency, barriers, and missed opportunities. J Fam Pract. 2002;51:706. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nusbaum MRH, Singh AR, Pyles AA. Sexual healthcare needs of women aged 65 and older. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:117–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52020.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mercer CH, Fenton KA, Johnson AM, et al. Who reports sexual function problems? Empirical evidence from Britain’s 2000 National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles. Sex Transm Infect. 2005;81:394–9. doi: 10.1136/sti.2005.015149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Selvin E, Burnett AL, Platz EA. Prevalence and risk factors for erectile dysfunction in the US. Am J Med. 2007;120:151–7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fenton KA, Johnson AM, McManus S, Erens B. Measuring sexual behaviour: methodological challenges in survey research. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:84–92. doi: 10.1136/sti.77.2.84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Feldman HA, Goldstein I, Hatzi−christou DG, Krane RJ, McKinlay JB. Impotence and its medical and psychosocial correlates: results of the Massachusetts Male Aging Study. J Urol. 1994;151:54–61. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)34871-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]